비과학

Non-science비과학은 과학적이지 않은 학문 분야, 특히 자연과학이나 과학 연구의 대상이 되는 사회과학이 아닌 학문 분야다. 이 모델에서 역사, 예술, 종교는 모두 비과학의 예다.[1][2]

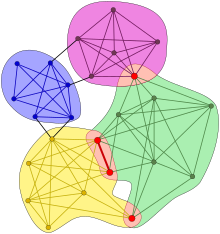

지식 분류

17세기 이후, 일부 작가들은 과학이라는 단어를 예술과 교양과목과 같은 학문의 일부 분야를 배제하기 위해 사용해 왔다.[3] 비과학적인 학문 분야를 묘사하기 위해 비과학적이라는 단어는 19세기 중반에 처음 사용되었다.[4]

경우에 따라서는 과학과 비과학의 정확한 경계를 파악하기 어려울 수 있다. 경계 문제는 과학과 비과학의 경계에 가까운 특정 학문 분야를 한 분야로 간주해야 하는지 다른 분야로 간주해야 하는지를 결정하는 데 있어서의 어려움에 대한 연구다. 아직 과학과 비과학을 명확히 구분할 수 있는 단일 테스트는 고안된 것이 없지만, 전체적으로 취하여 시간이 지남에 따라 평가되는 몇 가지 요인들이 공통적으로 사용된다.[5] 토마스 쿤의 견해에 따르면, 이러한 요소들은 어떤 질문을 마치 퍼즐처럼 조사하려는 과학자들의 욕구를 포함하고 있다. 쿤의 과학관도 결과보다는 과학적 탐구 과정에 초점이 맞춰져 있다.[5]

경계 작업은 경계선에 가까운 연구 분야를 분류하는 과정에서 바람직한 결과를 옹호하는 과정이다. 특정 분류를 획득하는 것과 관련된 보상은 과학과 비과학의 경계가 과학과 비과학의 엄연한 자연적 차이를 나타내기보다는 사회적으로 구성되고 이념적으로 동기가 부여된다는 것을 시사한다.[6] 과학적 지식(예: 생물학)이 다른 형태의 지식(예: 윤리학)보다 더 귀중하다는 믿음을 사이언톨로지라고 한다.[7]

비과학 영역

비과학은 과학이 아닌 모든 연구 영역을 포함한다.[1] 비과학은 다음을 포함한 모든 인문학을 포괄한다.

철학자 마틴 마너는 이러한 학문 분야를 유사과학과 같은 비과학적 형태와 구별하기 위해 파라시어라고 부르자고 제안했다.[1]

비과학자들은 문화, 도덕, 윤리에 대한 연구를 포함하여 삶의 의미, 인간의 가치, 인간의 상태, 그리고 다른 사람들과 상호 작용하는 방법에 대한 정보를 제공한다.[8][9]

의견 불일치 영역

철학자들은 순수 수학처럼 추상적인 개념을 포함하는 연구 영역이 과학적인 것인지 아니면 비과학적인 것인지에 대해 의견이 다르다.[10][11]

학제간 연구는 과학적 연구와 비과학적 연구를 모두 포함하는 지식 창출 작업을 포함할 수 있다. 고고학은 자연과학과 역사에서 모두 차용되는 분야의 예다.[1]

질의 분야는 시간이 지남에 따라 상태가 변할 수 있다. 수세기 동안 연금술은 과학적인 것으로 받아들여졌다. 연금술은 몇 가지 유용한 정보를 생산했고, 물리적 세계를 이해하는 데 있어 실험과 공개적인 조사를 지원했다. 20세기 이후로는 사이비과학으로 여겨져 왔다.[12][13] 연금술에서 발전한 현대화학은 대표적인 자연과학으로 꼽힌다.

대체 시스템

Paul Feyerabend와 같은 일부 철학자들은 지식을 과학과 비과학으로 분류하려는 노력에 반대한다.[14] 그 구별은 인위적인 것으로, 이른바 '사이언스'[14]라고 하는 지식의 모든 육체를 하나로 묶는 것이 거의 또는 전혀 없기 때문이다.

지식을 조직하는 어떤 시스템들은 개인적인 경험, 직관, 선천적인 지식과 같이 무언가를 알고 있거나 배우는 비체계적인 방법과 체계적인 지식을 분리한다. Wissenschaft는 주제 영역을 구분하지 않고 신뢰할 수 있는 지식을 포괄하는 넓은 개념이다.[1] 위센샤프트 개념은 가학성부터 가학성까지 모든 형태의 사이비학술에서 발생하는 오류가 유사하기 때문에 지식과 사이비지식을 구분하는 데 과학과 비과학의 구분보다 유용하다.[1] 이 위센샤프트 개념은 경제협력개발기구(OECD)가 발간한 2006년 과학기술 분야 리스트에 활용되는데, '과학과 기술'은 종교와 미술 등 모든 인문학적 분야를 아우르는 것으로 정의된다.[15]

참고 항목

- 경계 객체 – 동물 가죽과 같은 다른 연구 분야에 의해 합법적으로 다양한 방법으로 연구될 수 있는 항목

- 과학의 분야

- 교양과목

- 딱딱하고 부드러운 과학

- 카퍼의 기본적인 알 수 있는 방법

참조

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Hansson, Sven Ove (2017). "Science and Pseudo-Science". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2017 ed.). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Enger, Eldon; Ross, Frederick; Bailey, David (2014). Concepts in Biology. McGraw-Hill Higher Education. p. 10. ISBN 9780077418281.

Both scientists and nonscientists seek to gain information and improve understanding in their fields of study. The differences between science and nonscience are based on the assumptions and methods used to gather and organize information and, most important, the way the assumptions are tested. The difference between a scientist and a nonscientist is that a scientist continually challenges and tests principles and assumptions to determine cause-and-effect relationships. A nonscientist may not be able to do so or may not believe that this is important. For example, a historian may have the opinion that, if President Lincoln had not appointed Ulysses S. Grant to be a general in the Union Army, the Confederate States of America would have won the Civil War. Although there can be considerable argument about the topic, there is no way that it can be tested. Therefore, such speculation about historical events is not scientific. This does not mean that history is not a respectable field of study, only that it is not science. Historians simply use the standards of critical thinking that are appropriate to their field of study and that can provide insights into the role military leadership plays in the outcome of conflicts.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "science". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 2018-10-08.

- ^ "Nonscience". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 2018-10-08.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Nickles, Thomas (2017). Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Historicist Theories of Scientific Rationality. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2017 ed.). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University.

What demarcates science from nonscience and pseudoscience is sustained support (over historical time) of a puzzle-solving tradition, not the application of a nonexistent "scientific method" to determine whether the claims are true or false or probable to some degree.

- ^ Gieryn, Thomas F. (1983). "Boundary-work and the demarcation of science from non-science: strains and interests in professional ideologies of scientists". American Sociological Review. 48 (6): 781–795. doi:10.2307/2095325. JSTOR 2095325.

- ^ Stenmark, Mikael (2018-01-12). Scientism: Science, Ethics and Religion: Science, Ethics and Religion. Routledge. pp. 19–20. ISBN 9781351815390.

- ^ Lazorko, Pamela (2013). "Science and Non-Science". Philosophy Now. Retrieved 2018-04-17.

- ^ Ayala, Francisco (2007-05-07). Darwin's Gift: To Science and Religion. Joseph Henry Press. p. 178. ISBN 9780309661744.

Successful as it is, and universally encompassing as its subject is, a scientific view of the world is hopelessly incomplete. Matters of value and meaning are outside science's scope.

- ^ 비숍, 앨런(1997)"수학적 진화: 수학 교육에 대한 문화적 관점" 도드레흐트: 클루워 학술 출판사. 54페이지.

- ^ Bunge, Mario (1998). "The Scientific Approach". Philosophy of Science: Volume 1, From Problem to Theory. 1 (revised ed.). New York, NY: Routledge. pp. 3–50. ISBN 0-765-80413-1.

- ^ Conniff, Richard (February 2014). "Alchemy May Not Have Been the Pseudoscience We All Thought It Was". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 2018-04-16.

- ^ Hecht, David K. (2018-01-05). "Pseudoscience and the Pursuit of Truth". In Kaufman, Allison B.; Kaufman, James C. (eds.). Pseudoscience: The Conspiracy Against Science. MIT Press. pp. 8–9. ISBN 9780262037426.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Taylor, C.A. (1996). Defining Science: A Rhetoric of Demarcation. Rhetoric of the Human Sciences Series. University of Wisconsin Press. p. 41. ISBN 9780299150341. LCCN 96000180.

- ^ Working Party of National Experts on Science and Technology Indicators (2007), Revised Field of Science and Technology (FOS) Classification in the Frascati Manual {DSTI/EAS/STP/NESTI(2006)19/FINAL) (PDF), Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, retrieved 28 April 2018