터키의 석탄 발전

Coal power in Turkey

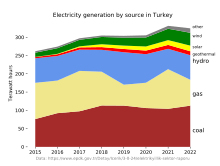

터키의 석탄은 터키 전력의 4분의 1에서 3분의 1을 생산합니다.총 21기가와트(GW) 용량의 54개 석탄화력발전소가 있습니다.

석탄 화력 발전소에서 발생하는 대기 오염은 국민 건강을 해치고 있으며,[3]: 48 2050년대가 아닌 2030년까지 석탄이 단계적으로 중단되면 10만 명 이상의 생명을 구할 수 있을 것으로 추정됩니다.[4]연도 가스 배출 한도는 2020년에 개선되었지만 배출 수준 보고 의무화 자료는 공개되지 않습니다.터키는 다른 나라를 오염시키는 미세먼지를 제한하는 예테보리 의정서를 비준하지 않았습니다.

터키의 석탄은 거의 모두 저칼로리 갈탄이지만, 정부 정책은 터키의 지속적인 사용을 지지합니다.이와 대조적으로, 독일은 150 MW 이하의 갈탄 화력 발전소를 폐쇄하고 있습니다.[5] 터키는 가뭄이 잦지만 화력 발전소는 상당한 양의 물을 사용합니다.[6]

석탄 화력 발전소는 세계 평균 수준인 1인당 매년 약 1톤의 온실가스를 배출하는 가장 큰 발전소입니다.[7]석탄 화력 발전소는 생산되는 킬로와트 시간당 1kg 이상의 이산화탄소를 배출하는데,[8] 이는 가스 전력의 두 배가 넘는 양입니다.학계에서는 2053년까지 터키의 탄소중립 목표에 도달하기 위해서는 2030년 중반까지 석탄 발전을 단계적으로 중단해야 한다고 제안하고 있습니다.[9]2023년 1월 국가 에너지 계획이 발표되었으며, 2030년까지 1.7GW를 더 포함하여 [10]: 23 2035년까지 24.3GW로 용량이 증가할 것으로 예상했습니다.[10]: 15 이 계획은 석탄 발전량은 감소하지만 유연하고 기저 부하 전력에 대한 용량 지불은 계속될 것으로 예상합니다.[10]: 25

에너지정책

에너지 전략에는 터키의 재생 에너지뿐만 아니라 터키의 개발을 지원하고 에너지 수입에 대한 의존도를 줄이기 위해 다른 지역 에너지 자원의 비중을 늘리는 것이 포함되어 있습니다.[11]2022년[update] 현재 터키는 이산화황과 질소 산화물의 배출 한도에 관한 예테보리 의정서를 비준하지 않았습니다.[12]2021년 초 터키는 기후 변화를 제한하기 위해 파리 협정을 비준했지만, 2021년[update] 10월 현재 정책은 여전히 에너지 믹스에서 국내 석탄 점유율을 증가시키는 것이었고, 석탄 발전의 계획된 증가는 CO2 배출량을 증가시킬 것으로 예측되었습니다.[13]: 79, 87 온실가스 배출량은 늦어도 2038년까지는 정점에 이를 것으로 약속되어 있습니다.[14]

시대

석탄 화력 발전소는 2020년에 수입 석탄에서 62TWh, 지역 석탄(거의 모든 갈탄)에서 44TWh로 구성된 국가 전력의 약 3분의 1을 생산합니다.[15][16][note 1]2022년 12월 총 용량은 21.8111기가와트(GW)로 2023년[update] 현재 54개의[note 2] 허가된 석탄화력발전소가 있습니다.[20]무면허 석탄 발전은 없습니다.[21]: 10 터키 석탄화력발전소의 평균 열효율은 36%[22]2021년에는 높은 수입 석탄 비용(70달러/MWh 이상)으로 인해 생산이 감소했습니다.[23]엠바 후누틀루는 2022년에 지어진 마지막 석탄 발전소입니다.[24]상하이 전력은 터키에 대한 중국의 최대 직접 투자가 될 것이라고 밝혔습니다.[25]하지만, 세계자연보호기금에 의하면, 보조금을 받지 않으면 이익을 낼 수 없다고 합니다.[26]ş인-엘비스탄 C와 새로운 석탄 화력 발전소들은 대중의 반대와 법원의 소송, 그리고 좌초된 자산이 될 위험성 때문에 건설되지 않을 것입니다.일반적인 열효율은 아임계, 초임계 및 초임계 발전소의 경우 39%, 42% 및 44%입니다.[33]

작전 함대의 대부분은 21세기에 만들어졌습니다.2020년에는 발전용량의 과잉공급과 수요 감소가 있었으며, 발전소의 4분의 1은 현금흐름이 마이너스인 것으로 추정되었습니다.[34]Bloomberg New Energy Finance에 따르면 10GW의 석탄 발전을 건설하는 데 드는 자본 비용은 25GW의 태양광 발전을 건설하는 데 사용될 것이라고 합니다.[35]또한 태양열 발전은 에어컨으로 인해 연간 전력 수요가 여름 오후에 최대이기 때문에 소비에 더 적합합니다.[36]

독일은 150MW 이하의 갈탄 화력 발전소를 폐쇄하고 있습니다.[37] 이웃 그리스는 갈탄 연료 발전소를 폐쇄하고 있습니다.[38]

유누스 엠레 발전소는 2020년에 완공되었지만 [16]: 42 2022년까지 전력망에 700시간의 전력을 생산하는 데 그쳤습니다.[39][40][41]이 지역의 석탄은 보일러에 적합하지 않기 때문에 좌초된 자산이 되었습니다. 이 ı델트 ı즐라 홀딩(이 ı델트 ı즐라 SSS 홀딩 A. ş)이 구입했습니다. 이 ı델트 ı즈 홀딩과 혼동하지 마십시오.2023년 5월, Fuat Oktay 부통령은 1호기가 6월에 재가동될 것이며,[42] 8월 중순까지 약 60GWh가 전력망으로 보내졌다고 말했습니다.[43]

몇 가지 예외를 제외하고 200 MW보다 작은 스테이션은 종종 공장에 전기와 열을 모두 제공하는 반면, 200 MW보다 큰 스테이션은 거의 모두 전기를 생산합니다.많은 양의 석탄 전력을 소유하고 있는 회사로는 Eren, Chelikler, Aydem, I ̇çDA ş, Anadolu Birlik (Konya Sugar 경유), Diler 등이 있습니다.

유연성

터키는 태양광과 풍력 발전의 혼합 발전에 대한 기여를 크게 늘릴 계획입니다.이러한 간헐적 발전원의 비율이 높은 비용 효율적인 시스템 운영을 위해서는 시스템 유연성이 필요하며, 간헐적 발전의 변화에 대응하여 다른 발전원을 신속하게 증가시키거나 감소시킬 수 있습니다.그러나 기존의 석탄 화력 발전은 태양광과 풍력 발전의 많은 부분을 수용하는 데 필요한 유연성을 가지고 있지 않을 수 있습니다.램프 업 속도를 증가시켜 1시간 안에 최대 부하에 도달하고 설치 용량의 약 9GW(하프 미만)에 대해 최소 발전량을 절반 최대로 낮추는 개조가 가능할 수 있습니다.[45]

석탄산업

갈탄(갈색탄)은 현지에서 채굴되기 때문에 정부 정책은 지속적인 발전을 지원하고,[46] 경탄(무연탄 및 유연탄)은 거의 전량 수입되고 있습니다.[47]2020년에는 5,100만 톤(83%)의 갈탄과 2,200만 톤(55%)의 경질 석탄이 발전소에서 연소되었습니다.[48]

2020년 아나돌루 비를릭 홀딩, 셀리클러 홀딩, 씨너 홀딩, 딜러 홀딩, 에렌 홀딩, 아이뎀, IC I ̇차 ş, 콜린, 오다 ş 등이 석탄으로 전기를 생산하는 데 크게 관여했습니다.

현지에서 채굴된 갈탄

갈탄을 연소하는 발전소는 터키 갈탄의 발열량이 12.5 MJ/kg 미만(그리고 Afsin Elbistan 갈탄은 일반적인 열탄의 1/4인 5 MJ/kg 미만)[50]이고, 약 90%는 3,000 kcal/kg 미만의 발열량이 낮기 때문에 엘비스탄과 같은 지역 탄광 근처에 있는 경향이 있습니다.[51]에너지 분석가인 할룩 디레스케넬리(Haluk Dreskeneli)에 따르면 터키 갈탄의 품질이 낮기 때문에 많은 양의 보조 연료유가 갈탄 화력 발전소에서 사용된다고 합니다.[52]

수입석탄

운송 비용을 최소화하기 위해 수입 석탄을 연소하는 발전소는 대개 해안에 위치해 있으며, 차낙칼레 주와 종굴닥 주, 이스켄데룬 만 주변에 클러스터가 있습니다.[53]최대 3%의 유황과 최소 5,400kcal/kg의 석탄을 수입할 수 있으며 연간 약 2,500만 톤을 연소할 수 있습니다. 2020년에는 거의 4분의 3이 콜롬비아에서 수입되었습니다.[54]싱크탱크 엠버에 따르면 2021년[update] 기준 신규 풍력·태양광 발전소를 건설하는 것이 수입 석탄에 의존하는 기존 석탄발전소를 운영하는 것보다 저렴합니다.[55]

대기오염

대기 오염은 수십 년 동안 터키에서 심각한 환경 및 공중 보건 문제입니다.1996년 3개의 오염 발전소를 폐쇄하라는 법원의 명령은 집행되지 않았습니다.[56]대기 오염 수치는 81개 주 중 51개 주에서 세계보건기구(WHO) 지침을 상회하는 수치를 기록했습니다.[57]장거리 대기오염에 대해서는 터키가 PM 2.5(미세먼지)를 포괄하는 예테보리 의정서를 비준하지 않고 있으며,[58] 장거리 월경성 대기오염에 관한 협약에 따른 보고는 불완전하다는 비판을 받고 있습니다.[59]: 10

2020년 1월에 새로운 배가스 배출 제한이 도입되었고,[60][61] 이로 인해 20세기 발전소 5곳이 새로운 제한을 충족하지 못해 그 달에 폐쇄되었습니다.[62]모두 배가스 필터를 새로 만드는 등 2020년 개선을 거쳐 재허가를 받았지만,[63][64] 지출이 충분하지 않았을 수 [65][66]있어 개선의 실효성에 의문이 제기되고 있습니다.[28]많은 정부 주변 공기 모니터링 지점이 결함이[67] 있고 미세 입자 물질을 측정하지 않기 때문에 최신 필터에 대한 데이터가 충분하지 않습니다.[57]미세먼지(PM2.5)는 가장 위험한 오염물질이지만 법적인 주변 환경 제한이 없습니다.[68]

'산업관련 대기오염관리규정'에는 연도가스 스택이 지상에서 10m 이상, 지붕에서 3m 이상 떨어져 있어야 한다고 돼 있습니다.[69]대형 발전소는 매연더미에서 대기 중으로 배출되는 지역 오염물질을 측정해 환경부에 보고해야 하지만, EU와 달리 데이터를 공개할 필요는 없습니다.[64]2022년 학계는 더 나은 모니터링과 더 엄격한 배출 제한을 요구했습니다.[70]

석탄은 대도시의 대기오염에 기여합니다.[71]일부 대형 석탄 화력 발전소에서 발생하는 대기 오염은 Sentinel 위성 데이터에서 공개적으로 볼 수 있습니다.[72][73]경제협력개발기구(OECD)는 노후 석탄화력발전소가 위험한 수준의 미세먼지를 내뿜고 있다며 노후 석탄화력발전소를 개조하거나 폐쇄해 미세먼지 배출을 줄일 것을 권고했습니다.[74]터키 정부는 개별 석탄화력발전소의 매연더미에서 대기오염 측정 결과를 보고받지만, EU와 달리 보고서를 발표하지는 않습니다.OECD는 또한 터키에 오염물질 방출 및 이전 등록부를 만들고 발표할 것을 권고했습니다.[75]

연도 가스 배출 한도(입방미터당 밀리그램(mg/Nm3):[76][77]

| 발전소규모 | 먼지. | SO2 | 아니오2 | CO |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5 MW ≤ 용량 < 5 MW | 200 | 탈황 시스템이 필요하지 않은 경우에 필요하지 않습니다.SO2 및 SO3 배출량은 2000mg/Nm3 미만입니다. 2000mg/Nm3 한계치를 초과할 경우 SO2 배출량을 10%로 줄여야 합니다. | 연도 가스를 재순환시켜 불꽃 온도를 낮추는 등의 기술적 조치를 통해 배출을x 줄이면 안 됩니다. | 200 |

| 5 MW ≤ 용량 < 50 MW | 150 | 200 | ||

| 50MW ≤ 용량 < 100MW | 50 | 850 | 400 | 150 |

| 용량 ≥ 100MW | 30 | 200 | 200 | 200 |

100mg/m의3 인도, 35mg/m의3 중국 등 다른 국가의 대형 석탄 화력 발전소에 대한 제한과2 EU 산업 배출 지침보다 완화된 제한입니다.[78]

온실가스 배출량

석탄화력발전소는 1킬로와트시당 1kg 이상의 이산화탄소를 배출하는데,[79] 이는 가스화력발전소의 두 배가 넘는 양입니다.터키의 석탄 화력 발전소는 터키 온실가스 배출의 가장 큰 원인입니다.[note 3]2019년 공공 열과 전기 생산은 [a]주로 석탄 연소를 통해 138메가톤의 COE2(COe2 당량)를 배출했습니다.

터키는 Af ş린-엘비스탄 C 건설을 위한 환경영향평가를 승인했으며, 평가에 따르면 발생하는 kWh당 5 kg 이상의 CO가 배출됩니다.이는 최소 탄소 효율 발전소 목록에 있는 어떤 발전소보다도 탄소 효율이 적을 것입니다.이 발전소에서 배출되는 연간 6천만 톤은 미국 전체 온실가스 배출량의 10% 이상이 될 것으로 예상되며, 현재의 세쿤다 CTL을 능가하는 세계 최대의 발전소가 될 것입니다.[83]

갈탄의 품질은 매우 다양하기 때문에, 특정 발전소의 이산화탄소 배출량을 추정하기 위해서는 그것이 연소한 갈탄의 순열량을 정부에 보고해야 합니다.그러나 이것은 일부 다른 나라들과 [84]달리 출판되지 않습니다.[85]그러나 기후 TRACE에 의한 우주 기반 이산화탄소 측정의 공개 정보에 따르면 2022년에는 개별 대형 발전소가,[86] 2023년에는[87] GOSAT-GW에 의한 소형 발전소가, 2025년에는 Sentinel-7에 의한 소형 발전소가 공개될 것으로 예상됩니다.[88][89]

2020년 연구에 따르면 터키 갈탄을 연소하는 발전소에 탄소 포집 및 저장을 맞추면 전기 비용이 50%[90] 이상 증가할 것으로 추정했습니다.2021년 터키는 2053년까지 탄소 순배출 제로를 목표로 했습니다.[91]2021년 기후 변화 제한에 관한 파리 협정이 비준된 후 많은 환경 단체들은 정부가 석탄 단계적 감축 목표 연도를 설정할 것을 요구했습니다.[92]

석탄 연소는 2018년에 총 150 Mt 이상의 CO를2 배출했으며,[93] 이는 터키 온실가스의 약 3분의 1에 해당합니다.[b]20 MW 이상의 개별 발전소에서 배출되는 배출량을 측정합니다.[94]터키 석탄화력발전소의 생애주기 배출량은 킬로와트시당 1kg COeq2 이상입니다.[79]제안된 Af şin-Elbistan C 발전소에 대한 환경영향평가(EIA)는 CO 배출량이 연간 6천만 톤 이상이 될 것으로 추정했습니다.이에 비해 터키의 연간 총 온실가스 배출량은 약 5억 2천만 톤입니다.[96] 따라서 터키의 온실가스 배출량의 10분의 1 이상이 계획된 발전소에서 나올 것입니다.[note 4][note 5]

2019년[update] 현재 석탄 광산 메탄은 환경 문제로 남아 있습니다.[103] 지하 광산에서 메탄을 제거하는 것이 안전 요구 사항이지만 대기로 배출될 경우 강력한 온실 가스이기 때문입니다.[104]

물 소비량

터키의 갈탄 화력 발전소는 과도한 갈탄 수송 비용을 피하기 위해 광산에 매우 근접해야 하기 때문에 대부분 내륙에 있습니다([105]터키의 활성 석탄 화력 발전소 지도 참조).석탄 발전소는 순환수 발전소와[106] 필요할 경우 석탄 세척을 위해 많은 양의 물이 필요할 수 있습니다.터키에서는 식물의 위치 때문에 민물을 사용합니다.생산된 GWh당 600~3000 입방미터의 물이 사용되는데,[107] 이는 태양광과 풍력보다 훨씬 많은 양입니다.[108]이러한 집중적인 사용은 인근 마을과 농경지의 부족으로 이어졌습니다.[109]

재

석탄을 태울 때 남은 광물 찌꺼기는 석탄재로 알려져 있으며, 석탄 화력 발전소의 근로자들과 터키의 대형[28] 석탄재 댐 근처에 살고 있거나 일하는 사람들에게 건강상 위험을 초래할 수 있는 독성 물질을 포함하고 있습니다.̇클림 드 ş리 ğ리 ı리 폴리티카베 아라 ş트 ğ르마 데르네 ğ리(기후변화정책연구회)의 2021년 보고서는 덜 엄격한 1년 임시운행허가를 반복적으로 부여함으로써 2020년대 환경법이 회피되고 있다며 석탄재 저장허가 기준(대학별 검사)이 불분명하다고 밝혔습니다.그래서 몇몇 발전소들은 건강하지 못한 석탄재를 적절하게 보관하지 않았습니다.그들은 일부 검사가 불충분할 수 있으며 검사 보고서를 요약하면 다음과 같습니다.

| 발전소명 | 건조 보관 | 젖은 보관함 | 주변채널 | 벽 | 펌프장치 | 지하수 오염도 분석/모니터링 | 관찰우물 | 철조망 | 배수 시스템 | 경사도 | 다른. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 엘비스탄의 Af ş B | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 먼지 관리 계획서를 작성해야 합니다. | ||||

| 야타 ğ란 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 불침투 구역 문제 | |||||

| 18 마르찬 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| 케머쾨이 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 매립지는 산림지역에 있습니다. | ||||

| 예니쾨이 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 매립지는 산림지역에 있습니다. | |||||

| 캉갈 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| 소마 | ✓ | 제방의 안전성, 좌식, 미끄럼 등 감시/보고를 위한 경과보고 | |||||||||

| 툰츠빌레크 주 | ✓ | ✓ | 지진구역내 건축물에 관한 규정 및 재해구역내 건축물에 관한 규정 준수 여부 | ||||||||

| 오르하넬리 | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| 세이이퇴머 | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| 차이 ı란 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| 쎄사츠 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 불침투구역 시공 | ||||||

| 엘비스탄의 Af ş | 환경영향평가보고서에 수록된 매립시설 건설공약사항을 순환보의 범위에서 재평가 |

세금, 보조금 및 장려금

2000년 즈음 열병합 발전소를 건설하기 위해 정부의 인센티브가 제공되었으며(공장 내 자동차 생산업체와 같이), [111]소규모 열병합 발전소는 산업단지나[112][113] 설탕 공장에 많이 지어졌습니다.[114][115]2021년까지 약 20개의 소형 자동차 생산업체가 운영되고 있지만 그리드에 연결되어 있지 않고 더 이상 라이센스가 필요하지 않기 때문에 공개적으로 사용할 수 있는 목록은 없습니다.[16][note 6]발열량이 낮기 때문에 갈탄 연소 전기는 다른 유럽 국가(그리스 제외)보다 발전 비용이 더 많이 듭니다.[116]

가장 최근에 역을 건설한 회사:센기즈, 콜린, 리막, 칼욘; 주로 에너지 부문보다는 건설 부문에 있습니다. 그리고 일부에서는 정치적으로 다른 건설 프로젝트에 유리한 입장에서 손해를 보고 목탄의 힘을 얻었다고 말합니다.[117]: 160

2019년에는 대형 갈탄 연소소에 총 10억 리라(1억 8천만 달러) 이상의 용량 지불을 지원했으며,[118] 2020년에는 12억 리라(2억 1천만 달러) 이상의 용량 지불을 지원했습니다.[119]2021년에는 갈탄과 수입 석탄을 혼합하여 연소하는 4개의 발전소도 용량 지불을 받았습니다.[120]이 용량 메커니즘은 일부 경제학자들에 의해 전략적 용량 보류를 부추긴다고 말하면서 비판을 받아 왔으며, 2019년 데이터에 따르면 전기 가격의 1% 상승은 발전소 발전 수명의 1분 증가와 상관관계가 있다고 합니다.[118]시가총액 2,000리라(2021년 약 350달러)/MWh. 이 경제학자들은 기업 수용 능력의 경매가 더 나은 메커니즘이 될 것이라고 말합니다. [118](이것은 일부 다른 나라에서[121] 행해지고 있습니다.) 만약 인도되지 않는다면, 재정적 벌금을 물게 되는 것입니다.[118]2022년[update] 11월 현재 23개 석탄화력발전소가 용량 메커니즘 지불을 받을 수 있습니다.[122]

이들 발전소의 일부 전기는 2027년 말까지 국영 전력회사에서 미화 50~55MWh/MWh의 보증가격으로 구입합니다.[123]: 109 2021년 마지막 분기에 보증 구매 가격은 MWh당 458리라(US$81)이며,[124] 수입 석탄은 국제 시장에서 석탄 가격을 뺀 톤당 US$70로 과세됩니다.[125]EU 탄소 국경 조정 메커니즘은 가스 다음으로 석탄 발전을 추진할 수 있습니다. 즉, 더 비싸질 수 있습니다.[126]

용량지급

터키 전력시장의 태양광·풍력 신제품과 달리 이들은 역경매로 결정된 것이 아니라 정부가 고정한 것으로 에너지 수요관리 대상이 아닙니다.[127]2020년에도 보조금 지급이 계속되고 있으며 13개 석탄화력발전소는 1월 지급을 받았습니다.[128]엔지니어 회의소 (tr:마키나 뮈헨디슬레리 오다스 ı)가 용량 메커니즘의 폐기를 요구했습니다.

페이즈 아웃

2019년 OECD는 터키의 석탄화력발전소 개발 프로그램이 큰 자본비용과 긴 인프라 수명으로 인해 높은 탄소잠금 위험을 발생시키고 있다고 밝혔습니다.[130]또한 미래에 맞지 않는 에너지와 기후 정책은 저탄소 경제로의 전환으로 인해 일부 자산이 경제적 수익을 제공하는 것을 막을 수 있다고 말했습니다.[131]또한 싱크탱크인 카본 트래커(Carbon Tracker)는 2022년까지 신규 석탄화력발전소보다 신규 풍력 또는 태양광 발전 가격이 저렴할 것으로 전망했습니다.터키 평균 석탄화력발전소는 2023년까지[132] 신규 재생에너지보다 장기운영비가 높고 2030년까지 모든 재생에너지가 증가할 것으로 전망됩니다.[133]보험업계는 화석연료로부터 서서히 손을 떼고 있습니다.[134]

2021년에 세계은행은 석탄으로부터 공정한 전환을 위한 계획이 필요하다고 말했습니다.[135]세계은행은 일반적인 목표를 제시하고 비용을 추정해 왔지만, 정부는 훨씬 더 상세한 계획을 세울 것을 제안했습니다.[136]여러 NGO의 2021년 연구에 따르면 석탄 발전 보조금이 완전히 폐지되고 탄소 가격이 US$40(2021년 EU 허용치보다 낮은) 수준으로 도입되면 수익성이 좋은 석탄 발전소는 없으며 2030년 이전에 모두 문을 닫을 것이라고 합니다.[124]2021년 카본 트래커(Carbon Tracker)에 따르면 이스탄불 증권 거래소에 대한 투자 중 10억 달러가 좌초될 위험에 처했으며, 여기에는 EUA ş에 대한 3억 달러가 포함되었습니다.터키는 에너지 전환을 위해 32억 달러의 차관을 보유하고 있습니다.[138]소형 모듈러 원자로는 석탄 발전을 대체할 것으로 제안되어 왔습니다.[139]

일부 에너지 분석가들은 낡은 공장들을 폐쇄해야 한다고 말합니다.[140]무 ğ라주에 있는 야타 ğ안, 예니쾨이, 케머쾨이 등 석탄화력발전소 3곳이 노후화되고 있습니다.그러나 공장과 관련 갈탄 광산이 폐쇄될 경우 약 5000명의 근로자가 조기 퇴직 또는 재교육을 위해 자금을 지원해야 합니다.[141]건강과[142] 환경적인 이익도 있겠지만,[143] 터키에서는 공장과 광산에 의한 지역 오염에 대한 데이터가 거의 공개적으로 입수되지 않았기 때문에 이를 정량화하기가 어렵습니다.[144][145]종굴닥 광산과 석탄 화력 발전소를 떠나 소마 지구에서 일하는 대부분의 노동자들을 고용하고 있습니다.[146]닥터에 의하면.코 ş쿠 셀리크 "시골 지역에 석탄을 투자하는 것은 농촌 주민들에게 고용 기회로 여겨져 왔습니다."

메모들

- ^ 2022년 석탄 화력 발전소의 총 발전량은 113 테라와트시(TWh)로 총 발전량의 36%를 차지했습니다.[17]터키의 활성 석탄 화력 발전소 목록에 있는 수치는 순 발전량입니다.

- ^ 자세한 내용은 tr:Türkiyye'deki kömür yak ı틀 ı enerji santralleri listesi 또는 해당 기본 위키데이터를 참조하십시오.TKI 2020 보고서에는 총 48개라고 나와 있습니다.[16]: 44 보고서는 국내 석탄을 사용하는 37개 발전소가 가동 중이라고 밝혔습니다.이 중 20개는 50MW 이상의 용량을 설치했으며 나머지는 소용량 자동 생산기와 열병합 발전소입니다.국내 석탄발전소는 경탄 1기와 아스팔트 1기를 제외하고 모두 갈탄화력발전소입니다.[16]: 41 에너지부는 2022년 말까지 [18]총 68기의 석탄화력발전소를 제공하고 있습니다.2021년 12월 TEI ̇라 ş는 아스팔트 1개, 수입 석탄 15개, 갈탄 47개, 경질 석탄 4개가 있으며 이는 총 67개라고 밝혔습니다(뉴스 보도에 따르면 일그 ı 설탕 공장이 운영되지 않고 있습니다).다른 사람들의 이름과 자세한 내용은 위키데이터로 알 수 없습니다.

- ^ UNFCCC 범주 1.A.1.에너지 산업 a.공공 전기 및 열 생산: 고체 연료.는 다른 카테고리보다 큰 1,600만 톤의 CO를2 보여줍니다.[80]

- ^ 현재 터키의 연간 배출량은 521메가톤인 반면, 목표 용량으로 가동하면 연간 62메가톤이[95] 배출됩니다.[96]단순 산술적으로 62메가톤은 521+62메가톤의 10% 이상입니다.

- ^ 2010년 석탄 화력 발전소가 터키에서 생산한 전력의 TWh당 평균 100만 톤 이상의 CO가2 배출되었습니다.[79]이 발전소는 연간 12.5 TWh(총 발전량)가 조금 넘는 것을 목표로 하고 있습니다.[97]EIA에서의 계산은 94.6 tCO2/TJ의 배출 계수를 가정하고 있으며,[98] 이는 터키 갈탄의 평균 31의 3배에 달합니다.[99] 그러나 이것이 2010년 평균에 비해 kWh당 CO2 배출량이 매우 높을 것으로 예측되는 유일한 이유인지는 불분명합니다.2020년부터 매연더미에서 나오는 지역 대기오염물질에 대한 보다 엄격한 여과가 의무화되고 있습니다.[100]게다가, 평균이 약 2800이지만,[101] 터키 갈탄의 순열량은 1000에서 6000 kcal/kg 사이에서 다양합니다.[102]

- ^ 일부 이전의 자동차 생산자 라이센스는 2007년의 다음 인용문의 표 20에 나열되어 있지만, 아직도 정확히 어떤 것이 작동하는지는 공개적으로 알려지지 않았습니다.[115]

참고문헌

- ^ Oberschelp, C.; Pfister, S.; Raptis, C. E.; Hellweg, S. (February 2019). "Global emission hotspots of coal power generation". Nature Sustainability. 2 (2): 113–121. doi:10.1038/s41893-019-0221-6. hdl:20.500.11850/324460. ISSN 2398-9629. S2CID 134220742. Archived from the original on 20 July 2021. Retrieved 16 July 2021.

- ^ "MUÇEP "Muğla'daki tüm santreller kapatılsın"" [Muğla Environment Platform: All thermal power stations in Muğla must be closed!]. Anter Haber (in Turkish). 3 January 2020. Archived from the original on 9 October 2021.

- ^ Karababa, Ali Osman; et al. (August 2020). "Dark Report Reveals the Health Impacts of Air Pollution in Turkey". Right to Clean Air Platform. Archived from the original on 7 January 2022. Retrieved 7 January 2022.

Coal-fired thermal power plants threaten the health of humans

- ^ Curing Chronic Coal: The health benefits of a 2030 coal phase out in Turkey (Report). Health and Environment Alliance. 2022.

- ^ Shrestha, Priyanka (27 November 2020). "EU approves German scheme to compensate hard coal plants for early closure". Energy Live News. Archived from the original on 7 April 2021. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- ^ El-Khozondar, Balkess; Koksal, Merih Aydınalp (2017). "Investigating the water consumption for electricity generation at Turkish power plants" (PDF). Department of Environmental Engineering, Hacettepe University. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 January 2022.

- ^ "G20 Per Capita Coal Power Emissions 2023". Ember. 5 September 2023. Retrieved 5 September 2023.

- ^ Vardar, Suat; Demirel, Burak; Onay, Turgut T. (22 March 2022). "Impacts of coal-fired power plants for energy generation on environment and future implications of energy policy for Turkey". Environmental Science and Pollution Research. 29 (27): 40302–40318. doi:10.1007/s11356-022-19786-8. ISSN 1614-7499. PMC 8940263. PMID 35318602.

- ^ Şahin, Umit; et al. (2021). "Turkey's Decarbonization Pathway Net Zero in 2050 Executive Summary" (PDF). Sabancı University. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 December 2021.

- ^ a b c Türkiye national energy plan (PDF) (Report). Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources. 2022.

- ^ "Turkey's International Energy Strategy". Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Turkey). 12 January 2022. Archived from the original on 19 September 2012.

- ^ "United Nations Treaty Collection: Protocol to the 1979 Convention on Long-range Transboundary Air Pollution to Abate Acidification, Eutrophication and Ground-level Ozone". treaties.un.org. Archived from the original on 17 April 2021. Retrieved 12 January 2022.

- ^ "Overview of the Turkish Electricity Market" (PDF). PricewaterhouseCoopers. October 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 October 2021. Retrieved 21 October 2021.

- ^ Kucukgocmen, Ali (15 November 2022). "Turkey raises greenhouse gas emission reduction target for 2030". Reuters. Retrieved 6 April 2023.

- ^ "Gas takes bigger share in Turkey's power as drought lowers hydro output". Hürriyet Daily News. 10 July 2021. Archived from the original on 16 July 2021. Retrieved 16 July 2021.

- ^ a b c d e "Kömür Sektör Raporu 2020" [Coal sector report 2020]. Turkish Coal Operations Authority. 2021. Archived from the original on 4 January 2022. Retrieved 4 January 2022.

- ^ "Coal". Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources. Retrieved 11 August 2023.

- ^ "T.C. Enerji ve Tabii Kaynaklar Bakanlığı - Elektrik". Energy Ministry. Retrieved 31 December 2022.

- ^ "TEİAŞ". Turkish Electricity Transmission Corporation. Archived from the original on 16 July 2021. Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- ^ "Coal".

- ^ "EPDK Enerji Piyasası Düzenleme Kurumu: 2021 Yılı Elektrik Piyasası Gelişim Raporu". www.epdk.gov.tr. Retrieved 7 June 2022.

- ^ "Kömür ve Linyit Yakıtlı Termik Santraller" [Coal and lignite fuelled power stations]. Enerji Atlası (in Turkish). Archived from the original on 5 April 2014. Retrieved 12 January 2022.

- ^ "Turkey Electricity Review 2022". Ember. 20 January 2022. Retrieved 20 January 2022.

- ^ "Turkey's new power plant exposes 'huge contradictions' of net zero pledge". Financial Times. 27 July 2022. Retrieved 2 August 2022.

- ^ "SEP Turkey Hunutlu Coal-fired Power Project Ratified". Shanghai Electric Power. 9 July 2015. Archived from the original on 16 July 2021. Retrieved 16 July 2021.

- ^ "Yenilenebilir Enerji Çağında Kömürün Fizibilitesi: Hunutlu Termik Santrali Örneği" [Feasibility of Coal in the age of Renewable Energy: The case of Hunutlu Thermal Power Station]. WWF Turkey (in Turkish). 13 January 2021. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 12 January 2022.

- ^ Direskeneli, Haluk (3 January 2020). "Enerji piyasalarında 2020 yılı öngörüleri" [Looking ahead to the 2020 energy market]. Enerji Günlüğü (in Turkish). Archived from the original on 30 November 2020. Retrieved 4 January 2020.

- ^ a b c "Turkey: Energy And Infrastructure Forecasts For 2022 – OpEd". 29 November 2021.

- ^ a b Boom and Bust Coal 2023 (Report). Global Energy Monitor. 5 April 2023.

- ^ "Kahramanmaraş'ta mahkeme Afşin C Termik Santrali için yürütmeyi durdurma kararı verdi, bundan sonra ne olacak?". BBC News Türkçe (in Turkish). Retrieved 16 March 2022.

- ^ Livsey, Alan (4 February 2020). "Lex in depth: the $900bn cost of 'stranded energy assets'". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 11 July 2021. Retrieved 16 July 2021.

- ^ "2022'de temiz enerji ön plana çıkacak" [Clean energy will come to the fore in 2022]. TRT Haber (in Turkish). 28 October 2021. Archived from the original on 28 October 2021. Retrieved 28 October 2021.

- ^ "Health and Environment Alliance Pollution from coal power costs Turkey as much as 27% of its total health expenditure – new report". Health and Environment Alliance. 4 February 2021. Retrieved 14 February 2022.

- ^ Political decisions, economic realities: The underlying operating cashflows of coal power during COVID-19 (Report). Carbon Tracker. 8 April 2020. Archived from the original on 12 April 2020. Retrieved 16 July 2021.

- ^ Climate Policy Factbook (Report). BloombergNEF. 20 July 2021. p. 29. Archived from the original on 21 July 2021. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ^ "Turkey breaks power consumption record on stifling hot day". Hürriyet Daily News. 30 June 2021. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- ^ "EU approves German scheme to compensate hard coal plants for early closure". Energy Live News. 27 November 2020. Archived from the original on 7 April 2021. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- ^ "Lignite phase-out a key aspect of national energy policy, Mitsotakis says". Kathimerini. 17 February 2020. Archived from the original on 21 February 2020.

- ^ a b Gacal, Funda; Stauffer, Anne (4 February 2021). Chronic coal pollution Turkey (Report). Health and Environment Alliance. Archived from the original on 9 May 2021.

- ^ "Real-Time Generation". EXIST Transparency Platform. Archived from the original on 18 March 2016. Retrieved 14 January 2022.

- ^ Monitor, Global Energy; CREA; E3G; Club, Sierra; SFOC; Network, Kiko; Europe, C. a. N.; LIFE; BWGED; BAPA; Bangladesh, Waterkeepers (25 April 2022). Boom And Bust Coal 2022 (Report).

- ^ "Bakan Dönmez Eskişehir Yunus Emre Termik Santrali'ni ziyaret etti".

- ^ "Gerçek Zamanlı Üretim - Gerçekleşen Üretim - Üretim EPİAŞ Şeffaflık Platformu". seffaflik.epias.com.tr. Retrieved 11 August 2023.

- ^ Overview of the Turkish Electricity Market (Report). PricewaterhouseCoopers. October 2021. Archived from the original on 28 November 2021. Retrieved 28 November 2021.

- ^ Saygin, D.; Tör, O. B.; Cebeci, M. E.; Teimourzadeh, S.; Godron, P. (1 March 2021). "Increasing Turkey's power system flexibility for grid integration of 50% renewable energy share". Energy Strategy Reviews. 34: 100625. doi:10.1016/j.esr.2021.100625. ISSN 2211-467X. S2CID 233798310.

- ^ Eleventh Development Plan (2019-2023) (PDF) (Report). Presidency of Strategy and Budget. 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 September 2020. Retrieved 18 July 2021.

- ^ EUAS Yıllık Rapor 2020 [2020 Annual Report] (Report). EÜAŞ. Archived from the original on 17 February 2021. Retrieved 16 July 2021.

- ^ "Solid Fuels, December 2020". Turkstat. Archived from the original on 16 July 2021. Retrieved 16 July 2021.

- ^ "2020 KÜRESEL KÖMÜRDEN ÇIKIŞ LİSTESİ: Dünyada 935 şirket kömür yatırımını genişletmeyi hedefliyor". Bianet. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- ^ "Nuclear Power in Turkey". World Nuclear Association. Archived from the original on 30 November 2020. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- ^ "Coal". Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources (Turkey). Archived from the original on 12 January 2021. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ^ Direskeneli, Haluk (6 October 2021). "Coal Plant Without Coal: Only In Turkey". Eurasia Review. Archived from the original on 19 October 2021. Retrieved 21 October 2021.

- ^ Walker, Laurence (11 February 2020). "Turkish coal imports set to rise in 2020 – analysts". www.montelnews.com. Archived from the original on 9 October 2021. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- ^ "Turkey softens coal import restrictions". Argus Media. 21 October 2021. Archived from the original on 28 October 2021. Retrieved 28 October 2021.

- ^ "Turkey: New wind and solar power now cheaper than running existing coal plants relying on imports". Ember. 27 September 2021. Archived from the original on 29 September 2021. Retrieved 29 September 2021.

- ^ Case of Okyay and others v. Turkey (PDF) (Report). Council of Europe. 12 October 2005. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 16 July 2021.

- ^ a b "Report: Air pollution becoming more lethal in Turkey while scientists struggle to access data". Bianet. 13 August 2020. Archived from the original on 9 October 2021. Retrieved 16 July 2021.

- ^ "United Nations Treaty Collection". treaties.un.org. Archived from the original on 17 April 2021. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ^ "Inventory Review 2021 Review of emission data reported under the LRTAP Convention" (PDF). EMEP Centre on Emission Inventories and Projections. March 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 7 January 2022.

- ^ "Sanayi̇ Kaynaklı Hava Ki̇rli̇li̇ği̇ni̇n Kontrolü Yönetmeli̇ği̇nde Deği̇şi̇kli̇k Yapılmasına Dai̇r Yönetmeli̇k" [Regulation Amending the Regulation on Control of Industrial Air Pollution]. Official Gazette of the Republic of Turkey (29211): Appx 1 page 15. 20 December 2014. Archived from the original on 27 February 2019. Retrieved 22 February 2019.

- ^ "Emission standards: Turkey" (PDF). International Energy Agency. 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2021. Retrieved 16 July 2021.

- ^ "Turkey shuts power plants for not installing filters". Anadolu Agency. 2 January 2020. Archived from the original on 2 January 2020. Retrieved 2 January 2020.

- ^ "Close Unfiltered Thermal Plants in Turkey During Coronavirus Outbreak". Bianet. 22 May 2020. Archived from the original on 9 October 2021. Retrieved 16 July 2021.

- ^ a b "Coal-fired plants reopen: Engineers cast doubt on minister's statement that 'obligations fulfilled'". Bianet. 17 June 2020. Archived from the original on 9 October 2021. Retrieved 16 July 2021.

- ^ Aytaç (2020).

- ^ Direskeneli, Haluk (4 January 2021). "Turkey: Energy And Infrastructure Forecast 2021- OpEd". Eurasia Review. Archived from the original on 18 July 2021. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- ^ "Six coal-fired plants continue to emit thick smoke after end of suspension". Bianet. 2 July 2020. Archived from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 16 July 2021.

Orhan Aytaş from the Chamber of Mechanical Engineers said the plant has installed a dry cooling system, which was ineffective due to the high amount of sulphur in the smoke of Turkey's coals.

- ^ Çetin, Yazar Arda (1 September 2020). "Dark Report Reveals the Health Impacts of Air Pollution in Turkey". Right to Clean Air Platform (in Turkish). Archived from the original on 7 January 2022. Retrieved 7 January 2022.

Afşin Elbistan Coal Fired Power Plant is estimated to have caused 17,000 premature deaths ........In Muğla, it is estimated that 45,000 premature deaths happened due to air pollution related to the 3 coal-fired thermal power plants since 1983.

: 50 - ^ Okutan, Hasancan; Ekinci, Ekrem; Alp, Kadir (2009). "Update and revision of Turkish air quality regulation". International Journal of Environment and Pollution. 39 (3/4): 340. doi:10.1504/IJEP.2009.028696. hdl:11729/345. ISSN 0957-4352. Archived from the original on 24 July 2021. Retrieved 24 July 2021.

- ^ Bartan, Ayfer; Kucukali, Serhat; Ar, Irfan; Baris, Kemal (16 March 2022). "An integrated environmental risk assessment framework for coal‐fired power plants: A fuzzy logic approach". Risk Analysis. 43 (3): 530–547. doi:10.1111/risa.13908. ISSN 0272-4332. PMID 35297076. S2CID 247499010.

- ^ Dennison, Asli Aydıntaşbaş, Susi (22 June 2021). "New energies: How the European Green Deal can save the EU's relationship with Turkey – European Council on Foreign Relations". ECFR. Retrieved 22 June 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 유지 : 여러 이름 : 저자 목록 (링크) - ^ "Polluters exposed by new eye in the sky satellite". 5 July 2018. Archived from the original on 24 October 2018. Retrieved 24 October 2018.

- ^ "TROPOMI Level 2 data products". KNMI R&D Satellite Observations. Archived from the original on 24 October 2018. Retrieved 24 October 2018.

- ^ 에피모바 마주르 미고토 람발리 (2019), p. 20

- ^ 에피모바 마주르 미고토 람발리 (2019), p. 30

- ^ "Emission standards: Turkey" (PDF). International Energy Agency.

- ^ "Sanayi̇ Kaynakli Hava Ki̇rli̇li̇ği̇ni̇n Kontrolü Yönetmeli̇ği̇nde Deği̇şi̇kli̇k Yapilmasina Dai̇r Yönetmeli̇k" [Official Gazette: Changes to industrial air pollution regulation]. Resmî Gazete (29211): Appx 1 page 15. 20 December 2014. Archived from the original on 27 February 2019. Retrieved 22 February 2019.

- ^ "Greenpeace analysis ranks global SO

2 air pollution hotspots". Greenpeace International. Archived from the original on 1 September 2019. Retrieved 1 September 2019. - ^ a b c Atilgan & Azapagic (2016), p. 177.

- ^ 투르크 통계표 (2021), 표 1A(a)s1 셀 G26.

- ^ Turkish Greenhouse Gas Inventory 1990 – 2019 common reporting format (CRF) tables [TurkStat tables] (TUR_2021_2019_13042021_230815.xlsx). Turkish Statistical Institute (Technical report). April 2021. Archived from the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 16 July 2021.

- ^ "EÜAŞ 1800 MW'lık Afşin C Termik Santrali için çalışmalara başlıyor" [Electricity Generation Company starts work on 1800 MW Afşin C thermal power station]. Enerji Günlüğü (in Turkish). 27 February 2020. Archived from the original on 2 March 2020. Retrieved 2 March 2020.

- ^ "The World's Biggest Emitter of Greenhouse Gases". Bloomberg News. 17 March 2020. Archived from the original on 16 February 2021. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- ^ 투르크 통계 보고서(2021), 페이지 49.

- ^ "Air Markets Program Data". United States Environmental Protection Agency. Archived from the original on 9 October 2021. Retrieved 16 July 2021.

- ^ "Transcript: The Path Forward: Al Gore on Climate and the Economy". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on 25 April 2021. Retrieved 6 May 2021.

- ^ "GOSAT-GW". World Meteorological Organization. Archived from the original on 14 June 2021. Retrieved 13 January 2022.

- ^ Morgan, Sam (5 December 2019). "CO2-tracking satellites crucial for climate efforts, say space experts". EURACTIV. Archived from the original on 1 February 2020. Retrieved 3 March 2020.

- ^ "European Sentinel satellites to map global CO2 emissions". BBC News. 31 July 2020. Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- ^ Coşkun, Tuba; Özkaymak, Prof Dr Mehmet; Okutan, Hasancan (31 December 2020). "Techno-Economic Feasibility Study of the Commercial-Scale Oxy-CFB Carbon Capture System in Turkey". Politeknik Dergisi. 24: 45–56. doi:10.2339/politeknik.674619.

- ^ Gundogmus, Yildiz Nevin (1 October 2021). "Turkey to follow up climate deal ratification with action: Official". Anadolu Agency. Archived from the original on 3 October 2021. Retrieved 3 October 2021.

- ^ Erkul, Nuran (7 October 2021). "Paris Agreement's ratification launches new climate policy era in Turkey". Anadolu Agency. Archived from the original on 7 October 2021. Retrieved 9 October 2021.

- ^ 투르크 통계 보고서(2020), 페이지 57.

- ^ "ETS Detailed Information: Turkey". International Carbon Action Partnership. Archived from the original on 31 March 2019.

- ^ a b Cs ı나르(2020), 페이지 319: Atmosfeer Verilecek CO Miktar ı: … = 61.636.279,98 tCO2/y ı"은 "대기로 방출되는 CO의 양: … = 61,636,279.98 tCO2/y년"을 의미합니다.

- ^ a b "Greenhouse Gas Emissions Statistics". Turkish Statistical Institute. Retrieved 17 January 2023.

- ^ Cs ı나르(2020), p. xix: "y ıell ık ortalama brüt 12.506 GWh, 순 11.380 GWhenerji üretimi hedeflenmektedir."는 "목표 연간 발전량은 총 12,506 GWh, 순 11,380 GWh"를 의미합니다.

- ^ ı나르 (2020), 페이지 319.

- ^ 투르크 통계 보고서(2020), p. 50.

- ^ "Turkey shuts power plants for not installing filters". Anadolu Agency. 2 January 2020. Archived from the original on 2 January 2020. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- ^ Yerli̇ ve mi̇lli̇ enerji̇ poli̇ti̇kalari ekseni̇nde kömür [Coal on the axis of local and national energy policies] (PDF) (Report). Foundation for Political, Economic and Social Research. January 2019. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 February 2019. Retrieved 13 February 2019.

- ^ 투르크 통계 보고서(2020), pp. 59, 60

- ^ "Paving the way for safer and greener coal mine methane management in Turkey and Ukraine". www.unece.org. Retrieved 8 February 2020.

- ^ "Coal overview: Turkey" (PDF). Global Methane Project. 2020.

- ^ "Why is there no lignite market?". Euracoal. 11 September 2014. Archived from the original on 11 May 2020. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- ^ El-Khozondar, Balkess D. J. (2017). "Investigating the Use of Water for Electricity Generation at Turkish Power Plants" (PDF). Hacettepe University. p. 84. Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 August 2019. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- ^ Özcan, Zeynep; Köksal, Merih Aydınalp; Alp, Emre (2020). "Evaluation of Water–Energy Nexus in Sakarya River Basin, Turkey". In Naddeo, Vincenzo; Balakrishnan, Malini; Choo, Kwang-Ho (eds.). Frontiers in Water-Energy-Nexus—Nature-Based Solutions, Advanced Technologies and Best Practices for Environmental Sustainability. Advances in Science, Technology & Innovation. Cham: Springer International Publishing. pp. 421–424. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-13068-8_105. ISBN 978-3-030-13068-8. S2CID 204261568.

- ^ "The water-energy nexus at rivers can be resolved worldwide by 2050 as a consequence of the energy transition - News - LUT". www.lut.fi. Archived from the original on 13 February 2020. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- ^ "Thermal power plants in Zonguldak and Muğla leave nearby villages without water in the middle of a pandemic". www.duvarenglish.com. 13 April 2020. Archived from the original on 19 April 2020. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- ^ Çaltı, Nuray; Bozoğlu, Dr. Baran; Aldırmaz, Ahmet Turan; Atalar, Gülşah Deniz (2 June 2021). Özelleştirilmiş Termik Santraller ve Çevre Mevzuatına Uyum Süreçleri [Privatized Thermal Power Stations and Environmental Legislation Compliance Processes] (Report) (in Turkish). İklim Değişikliği Politika ve Araştırma Derneği. Archived from the original on 9 October 2021. Retrieved 27 July 2021.

- ^ Pamukcu, C.; Konak, G. (2006). "A Review of the Energy Situation in Turkey". Energy Exploration & Exploitation. 24 (4): 223–241. doi:10.1260/014459806779398811. ISSN 0144-5987.

- ^ "An Energy Overview of the Republic of Turkey". www.geni.org. Archived from the original on 10 June 2021. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ^ Özkan, Cüneyt Taha (2019). "Turkish Energy Transition and Current Challenges" (PDF). Jean Monnet University. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ Tamzok, Nejat. "İthal kömür açmazı" [Imported coal deadlock] (PDF). Chamber of Electrical Engineers (Turkey). Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 July 2021. Retrieved 16 July 2021.

- ^ a b "Kömür Çalişma Grubu Raporu" [Coal working group report] (PDF). World Energy Council. 2007. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 July 2021.

- ^ "Cost of lignite-fired power generation Heinrich Böll Stiftung - Thessaloniki Office". Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung. Retrieved 17 April 2022.

- ^ Jakob, Michael; Steckel, Jan C., eds. (2022). The Political Economy of Coal: Obstacles to Clean Energy Transitions. Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781003044543. ISBN 9781003044543.

- ^ a b c d Durmaz, Tunç; Acar, Sevil; Kizilkaya, Simay (4 October 2021). "Electricity Generation Failures and Capacity Remuneration Mechanism in Turkey". SSRN. Rochester, NY. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3936571. S2CID 240873974. SSRN 3936571. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 25 October 2021.

- ^ "Kapasite Mekanizması Ödeme Listeleri" [Capacity mechanism payment list]. Turkish Electricity Transmission Corporation. Archived from the original on 9 October 2021. Retrieved 28 March 2021.

- ^ "Elektrik santrallerine 187 milyon liralık kapasite mekanizması desteği" [187 million lira capacity mechanism support to power stations]. Hürriyet (in Turkish). 2 October 2021. Archived from the original on 25 October 2021. Retrieved 25 October 2021.

- ^ Watson, Frank; Edwardes-Evans, Henry (27 August 2021). "EC approves Belgium's electricity capacity market design". S&P Global. Archived from the original on 25 October 2021. Retrieved 25 October 2021.

- ^ "2023'de 50 santral kapasite mekanizmasından yararlanacak" [TEİAŞ announces the 50 power plants to benefit from the capacity mechanism in 2023]. Enerji Günlüğü (in Turkish). 3 November 2022. Retrieved 9 December 2022.

- ^ IEA (2021).

- ^ a b "First Step in the Pathway to a Carbon Neutral Turkey: Coal Phase out 2030". Sustainable Economics and Finance Association. APLUS Energy for Europe Beyond Coal, Climate Action Network (CAN) Europe, Sustainable Economics and Finance Research Association (SEFiA), WWF-Turkey (World Wildlife Fund), Greenpeace Mediterranean, 350.org and Climate Change Policy and Research Association. November 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 November 2021. Retrieved 7 November 2021.

- ^ Senerdem, Erisa (26 August 2020). "Coal imports help Turkish economy in 1H20". Argus Media. Archived from the original on 25 October 2021. Retrieved 25 October 2021.

- ^ Göktuğ, Göktuğ; Taksim, Muhammed Ali; Yitgin, Burak (2021). "Effects of the European Green Deal on Turkey's Electricity Market". The Journal of Business, Economic and Management Research. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ "Elektri̇k Pi̇yasasi Kapasi̇te Mekani̇zmasi Yönetmeli̇ği̇nde Deği̇şi̇kli̇k Yapilmasina Dai̇r Yönetmeli̇k" [Changes to electricity market capacity mechanism regulations]. Official Gazette. 9 January 2019. Archived from the original on 12 January 2019. Retrieved 12 January 2019.

- ^ "TEİAŞ Yayınladı: Kapasite Mekanizması 2020 Yılı Ocak Ayı Ödeme Listesi" [Turkish Electricity Transmission Corporation press release: January 2020 capacity mechanism payments list]. Enerji Ekonomisi (in Turkish). Archived from the original on 23 March 2020. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- ^ "MMO: Enerji yönetimi ve özel şirketler ellerini yurttaşların ceplerinden çekmelidir" [Chamber of Engineers: Energy management and private companies should get their hands out of citizens' pockets]. birgun.net (in Turkish). Archived from the original on 5 February 2021. Retrieved 4 February 2021.

- ^ 에피모바 마주르 미고토 람발리 (2019), p. 40

- ^ 에피모바 마주르 미고토 람발리 (2019), p.

- ^ "Powering down coal: Navigating the economic and financial risks in the last years of coal power" (PDF). Carbon Tracker Initiative. November 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 December 2018. Retrieved 23 December 2018.

- ^ "Powering down coal: Navigating the economic and financial risks in the last years of coal power". Carbon Tracker Initiative. Archived from the original on 1 December 2018. Retrieved 30 November 2018.

- ^ "Fosil yakıtlar ve kömür sigorta portföyünden çıkıyor". www.patronlardunyasi.com. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- ^ Erkuş, Sevil (15 November 2021). "World Bank official praises Turkey's GDP growth". Hürriyet Daily News. Archived from the original on 15 November 2021. Retrieved 20 January 2022.

- ^ Türkiye - Country Climate and Development Report (Report). World Bank. 13 June 2022.

- ^ "Taking Stock of Coal Risks". Carbon Tracker. November 2021. Archived from the original on 4 November 2021.

- ^ "EU's looming carbon tax nudged Turkey toward Paris climate accord, envoy says". POLITICO. 6 November 2021. Archived from the original on 7 November 2021. Retrieved 7 November 2021.

- ^ "Turkey in talks with US to buy small nuclear reactors, weaning itself off coal". Al Arabiya English. 21 December 2022. Retrieved 13 January 2023.

- ^ Direskeneli, Haluk (19 March 2023). "Sustainable Energy In Turkey – OpEd". Eurasia Review. Retrieved 21 March 2023.

- ^ "The Real Costs of Coal: Muğla". Climate Action Network Europe. Archived from the original on 26 January 2019. Retrieved 25 January 2019.

- ^ Ugurtas, Selin (17 April 2020). "Coronavirus outbreak exposes health risks of coal rush". Al-Monitor. Archived from the original on 21 April 2020. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ "Beyaz Çamaşır Asılamayan Şehir (ler)" [Cities where washing cannot be hung out to dry]. Sivil Sayfalar (in Turkish). 13 April 2020. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ Welle (www.dw.com), Deutsche. "Turkey: Censorship fogging up pollution researchers' work DW 17 September 2019". DW.COM. Archived from the original on 12 April 2020. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ 유럽위원회(European Commission, 2019), p. 93: "환경문제에 대한 법원의 결정에서 법치주의를 적용하는 것과 국민의 참여와 환경정보에 대한 권리에 대한 불만이 여전히 존재합니다."

- ^ "Soma Termik Santrali'nde emisyon oranlarını Bakanlığa anlık bildiren sistem kuruldu". Sabah (in Turkish). Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- ^ "Extractivism, State and Socio-Environmental Struggles: Turkey and Ecuador". The Media Line. 20 September 2020. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

원천

- Atilgan, Burcin; Azapagic, Adisa (2016). "An integrated life cycle sustainability assessment of electricity generation in Turkey". Energy Policy. 93: 168–186. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2016.02.055.

- Turkish Greenhouse Gas Inventory report [TurkStat report]. Turkish Statistical Institute (Technical report). 13 April 2021.

- Turkish Greenhouse Gas Inventory 1990 – 2019 common reporting format (CRF) tables [TurkStat tables] (TUR_2021_2019_13042021_230815.xlsx). Turkish Statistical Institute (Technical report). April 2021.

- Çınar Engineering Consultancy (March 2020). Afşin C power station environmental impact report (Report) (in Turkish). Ministry of Environment and Urban Planning.

- Aytaç, Orhan (May 2020). Ülkemi̇zdeki̇ Kömür Yakitli Santrallar Çevre Mevzuatiyla uyumlu mu? [Are Turkey's coal-fired power stations in accordance with environmental laws?] (PDF) (Report) (in Turkish). TMMOB Maki̇na Mühendi̇sleri̇ Odasi. ISBN 978-605-01-1367-9.

- IEA (March 2021). Turkey 2021 – Energy Policy Review (Technical report). International Energy Agency.

- Efimova, Tatiana; Mazur, Eugene; Migotto, Mauro; Rambali, Mikaela; Samson, Rachel (February 2019). OECD Environmental Performance Reviews: Turkey 2019. OECD (Report). OECD Environmental Performance Reviews. doi:10.1787/9789264309753-en. ISBN 9789264309760.

- European Commission (May 2019). "Turkey 2019 Report" (PDF).

- Turkstat (April 2020). Turkish Greenhouse Gas Inventory report [TurkStat report] (Report).