스탠리 큐브릭의 영화 목록

Stanley Kubrick filmography

스탠리 큐브릭 (1928–1999)은 [1]그의 경력 동안 13편의 장편 영화와 3편의 단편 다큐멘터리를 감독했습니다.다양한 [2]장르에 걸친 감독으로서의 그의 작품은 매우 [3][4][5]영향력 있는 것으로 널리 여겨집니다.

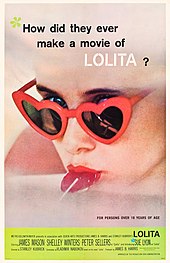

큐브릭은 1951년 단편 다큐멘터리 데이 오브 더 파이트로 감독 데뷔를 했고, 그 해 말 플라잉 파드르가 그 뒤를 이었습니다.1953년, 그는 그의 첫 장편 영화인 공포와 [6]욕망을 감독했습니다.반전 우화의 주제는 그의 후기 [7][8]영화에 다시 등장했습니다.그의 다음 작품은 영화 누아르 영화 킬러의 키스 (1955)와 킬링 (1956)[9][10]이었습니다.비평가 로저 이버트는 킬링을 칭찬했고 회고적으로 그것을 큐브릭의 "첫 번째 성숙한 특징"[9]이라고 불렀습니다.그리고 나서 큐브릭은 커크 더글러스가 주연한 두 편의 할리우드 영화: Paths of Glory (1957)와 스파르타쿠스 (1960)[11][12]를 감독했습니다.후자는 골든 글로브상 최우수 영화 드라마 [13]부문을 수상했습니다.그의 다음 영화는 블라디미르 나보코프의 동명 [14]소설을 각색한 로리타 (1962)였습니다.아카데미 [15]각색상 후보에 올랐습니다.그의 1964년 영화, 피터 셀러스와 조지 C가 출연한 냉전 풍자 닥터 스트레인지러브. 스콧,[16] BAFTA 최우수 [17]영화상 수상.The Killing과 함께, 그것은 Rotten Tomatoes에 따르면 큐브릭이 감독한 가장 높은 평가를 받은 영화로 남아있습니다.

1968년, 큐브릭은 우주 서사시 2001: A Space Odyssey를 감독했습니다.이제까지 만들어진 [18]영화들 중 가장 영향력 있는 영화들 중 하나로 널리 간주되는 2001년, 특수 [19]효과 감독으로서의 그의 작품으로 큐브릭은 유일한 개인 아카데미 상을 수상했습니다.그의 다음 프로젝트인 디스토피아 시계장치 오렌지 (1971)는 앤서니 버지스의 1962년 [20][21][22]소설을 처음에 X 등급으로 각색한 것이었습니다.영화의 "초폭력" 묘사에 영감을 받은 범죄에 대한 보도가 있은 후,[21] 큐브릭은 영화를 영국에서 배급에서 철수시켰습니다.그리고 나서 큐브릭은 그의 이전 두 개의 미래 영화에서 [23]벗어나 시대 작품 배리 린든 (1975)을 감독했습니다.그것은 상업적으로 좋은 성과를 거두지 못했고 엇갈린 평가를 받았지만, 48회 아카데미 시상식에서 [24][25]4개의 오스카 상을 수상했습니다.1980년, 큐브릭은 스티븐 킹 소설을 잭 니콜슨과 셸리 듀발이 [26]주연한 샤이닝으로 각색했습니다.비록 큐브릭이 골든 라즈베리상 최악의 [27]감독상 후보에 올랐지만, 더 샤이닝은 지금까지 [26][28][29]만들어진 가장 위대한 공포 영화 중 하나로 널리 여겨집니다.7년 후, 그는 베트남 전쟁 영화 풀 메탈 [30]재킷을 출시했습니다.로튼 토마토와 메타크리틱에 따르면 이 영화는 큐브릭의 후기 영화 중 가장 높은 평점을 유지하고 있습니다.1990년대 초, 큐브릭은 아리안 페이퍼라는 제목의 홀로코스트 영화를 감독하려는 계획을 포기했습니다.그는 스티븐 스필버그의 쉰들러 리스트와 경쟁하는 것을 주저했고 [2][31]이 프로젝트에 광범위하게 작업한 후 "심각하게 우울해졌습니다."그의 마지막 영화인 톰 크루즈와 니콜 키드먼이 주연한 에로틱 스릴러 아이즈 와이드 셧은 1999년 [32]사후에 개봉되었습니다.큐브릭이 피노키오라고 불렀던 미완성 프로젝트가 스필버그에 의해 A로 완성되었습니다.I. 인공지능(2001).[33][34]

1997년 베니스 영화제는 큐브릭에게 평생 공로상 황금 사자상을 수여했습니다.같은 해, 그는 D.W. 그리피스 [35][36]상이라고 불리는 미국 감독 조합 평생 공로상을 받았습니다.1999년, 영국 영화 텔레비전 예술 아카데미 (BAFTA)는 큐브릭에게 브리타니아 [37]상을 수여했습니다.그가 죽은 후, BAFTA는 그를 기리기 위해 그 상의 이름을 "스탠리 큐브릭 브리타니아 [38]영화상"으로 바꿨습니다.그는 [39]2000년에 사후 BAFTA 펠로우십을 수여받았습니다.

영화들

장편 영화

| 연도 | 제목 | 감독. | 작가. | 프로듀서 | 메모들 | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1952 | 공포와 욕망 | 네. | 아니요. | 네. | 편집자 겸 촬영 기사 | [7][40] |

| 1955 | 킬러의 키스 | 네. | 아니요. | 네. | 편집자 겸 촬영 기사 | [41] |

| 1956 | 킬링 | 네. | 네. | 아니요. | 짐 톰슨과 공동 집필 | [10] |

| 1957 | 영광의 길 | 네. | 네. | 아니요. | 칼더 윌링엄, 짐 톰슨과 공동 집필 | [42][43] |

| 1960 | 스파르타쿠스 | 네. | 아니요. | 아니요. | [44] | |

| 1962 | 로리타 | 네. | 신용 없음 | 아니요. | [45][46] | |

| 1964 | 닥터 스트레인지러브 | 네. | 네. | 네. | 테리 서던, 피터 조지와 공동 집필 | [47] |

| 1968 | 2001: 스페이스 오디세이 | 네. | 네. | 네. | 아서 C와 공동 집필. 클라크 또한 특수 사진 효과의 감독이자 디자이너입니다. | [19][48] [49][50] |

| 1971 | 시계추 오렌지 | 네. | 네. | 네. | [21][51] | |

| 1975 | 배리 린든 | 네. | 네. | 네. | [52][53] | |

| 1977 | 나를 사랑한 스파이 | 아니요. | 아니요. | 아니요. | 인증되지 않은 조명 설계 | [54] |

| 1980 | 샤이닝 | 네. | 네. | 네. | 다이앤 존슨과 공동 집필 | [55] |

| 1987 | 완전 금속 재킷. | 네. | 네. | 네. | 마이클 허, 구스타프 해스퍼드와 공동 집필 | [30] |

| 1999 | 아이즈 와이드 셧 | 네. | 네. | 네. | 프레데릭 라파엘과 공동 집필 사후 석방 | [56][57] |

| 2001 | 인공지능 | 아니요. | 아니요. | 아니요. | 이 영화는 영화의 각색을 의도한 큐브릭에게 헌정되었습니다. | [58][59] |

다큐멘터리 단편

| 연도 | 제목 | 감독. | 작가. | 프로듀서 | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1951 | 데이 오브 더 파이트 | 네. | 네. | 네. | [60][61] |

| 플라잉 파드레 | 네. | 네. | 아니요. | [62][63] | |

| 1952 | 세계청년총회 | 네? | 아니요. | 아니요. | [64][65] |

| 1953 | 선원들 | 네. | 아니요. | 네. | [66] |

텔레비전

1952년, 소리, 효과, 음악으로 인해 공포와 욕망의 제작은 예산보다 약 53,000 달러[67]가 증가했고, 제작자인 Richard de Rochemont에 의해 구제되어야 했다,제임스 에이지가 각본을 쓴 노먼 로이드가 공동 연출한 에이브러햄 링컨에 관한 5부작 전기 시리즈의 제작에 대해 그가 두 번째 유닛 감독[68][69]으로 일하는 조건으로교육용 TV 시리즈 옴니버스는 켄터키주 [72][73]호젠빌에서 촬영되었으며 로얄 다노와 조앤 [65][74][72]우드워드가 주연을 맡았습니다.

비판적 반응

| 연도 | 제목 | 로튼 토마토[75] | 메타크리틱[76] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1953 | 공포와 욕망 | 75%(16개 리뷰) | — |

| 1955 | 킬러의 키스 | 86%(21개 리뷰) | — |

| 1956 | 킬링 | 98%(41개 리뷰) | 91 (15개 리뷰) |

| 1957 | 영광의 길 | 95%(60개 리뷰) | 90개(18개 리뷰) |

| 1960 | 스파르타쿠스 | 93%(61개 리뷰) | 87(17개 리뷰) |

| 1962 | 로리타 | 91%(43개 리뷰) | 79 (14개 리뷰) |

| 1964 | 닥터 스트레인지러브 | 98%(91개 리뷰) | 97(32개 리뷰) |

| 1968 | 2001: 스페이스 오디세이 | 92%(113개 리뷰) | 84 (25개 리뷰) |

| 1971 | 시계추 오렌지 | 86%(71개 리뷰) | 77 (21개 리뷰) |

| 1975 | 배리 린든 | 91%(74건의 리뷰) | 89(21개 리뷰) |

| 1980 | 샤이닝 | 84%(95개 리뷰) | 66 (26개 리뷰) |

| 1987 | 완전 금속 재킷. | 92%(83개 리뷰) | 76 (19개 리뷰) |

| 1999 | 아이즈 와이드 셧 | 75%(리뷰 포함) | 68(34개 리뷰) |

참고 항목

레퍼런스

- ^ Holden, Stephen (March 8, 1999). "Stanley Kubrick, Film Director With a Bleak Vision, Dies at 70". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 4, 2021. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- ^ a b Pulver, Andrew (April 26, 2019). "Stanley Kubrick: film's obsessive genius rendered more human". The Guardian. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- ^ Townend, Joe (July 20, 2018). "A Fifty-Year Odyssey: How Stanley Kubrick Changed Cinema". Sotheby's. Archived from the original on September 27, 2020. Retrieved January 10, 2021.

- ^ Koehler, Robert (Fall 2017). "Kubrick's Outsized Influence". DGA Quarterly. Directors Guild Of America. Archived from the original on January 8, 2018. Retrieved January 10, 2021.

- ^ Chilton, Louis (September 29, 2019). "Stanley Kubrick's 10 best films – ranked: From A Clockwork Orange to The Shining". The Independent. Archived from the original on November 20, 2020. Retrieved January 10, 2021.

- ^ Erickson, Steve (October 24, 2012). "Stanley Kubrick's First Film Isn't Nearly as Bad as He Thought It Was". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on January 31, 2018. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- ^ a b French, Phillip (February 2, 2013). "Fear and Desire". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on May 8, 2020. Retrieved August 17, 2020.

- ^ Burgess, Jackson (Autumn 1964). "The "Anti-Militarism" of Stanley Kubrick". Film Quarterly. University of California Press. 18 (1): 4–11. doi:10.2307/1210143. JSTOR 1210143. Retrieved January 22, 2021.

- ^ a b "Killer's Kiss". Turner Classic Movies. Archived from the original on October 28, 2020. Retrieved January 18, 2021.

- ^ a b Ebert, Roger (January 9, 2012). "A heist played like a game of chess". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on August 8, 2020. Retrieved August 15, 2020.

- ^ Truit, Brian (February 5, 2020). "Five essential Kirk Douglas movies, from 'Paths of Glory' to (obviously) 'Spartacus'". USA Today. Archived from the original on February 10, 2020. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- ^ Alberge, Dalya (November 9, 2020). "Stanley Kubrick and Kirk Douglas wanted Doctor Zhivago movie rights". The Guardian. Archived from the original on January 17, 2021. Retrieved January 22, 2021.

- ^ "Spartacus". Golden Globe Awards. Hollywood Foreign Press Association. Archived from the original on March 23, 2019. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- ^ Colapinto, John (January 2, 2015). "Nabokov and the Movies". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on November 28, 2020. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- ^ "The 35th Academy Awards". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Retrieved February 27, 2021.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (July 11, 1999). "Dr. Strangelove". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on December 7, 2020. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- ^ "Film in 1965". BAFTA. Archived from the original on September 9, 2019. Retrieved January 6, 2021.

- ^ Overbye, Dennis (May 10, 2018). "'2001: A Space Odyssey' Is Still the 'Ultimate Trip' – The rerelease of Stanley Kubrick's masterpiece encourages us to reflect again on where we're coming from and where we're going". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 11, 2018. Retrieved January 22, 2021.

- ^ a b Child, Ben (September 4, 2014). "Kubrick 'did not deserve' Oscar for 2001 says FX master Douglas Trumbull". The Guardian. Archived from the original on January 7, 2021. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- ^ "'Clockwork Orange' To Get an 'R' Rating". The New York Times. August 25, 1972. Archived from the original on January 9, 2021. Retrieved January 8, 2021.

- ^ a b c Bradshaw, Peter (April 5, 2019). "A Clockwork Orange review – Kubrick's sensationally scabrous thesis on violence". The Guardian. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved January 6, 2021.

- ^ McCrum, Robert (April 13, 2015). "The 100 best novels: No 82 – A Clockwork Orange by Anthony Burgess (1962)". The Guardian. Archived from the original on August 3, 2020. Retrieved January 8, 2021.

- ^ Sims, David (October 26, 2017). "The Alien Majesty of Kubrick's Barry Lyndon". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on January 7, 2021. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- ^ "Slow burn: Why the languid Barry Lyndon is Kubrick's masterpiece". BBC. April 25, 2019. Archived from the original on January 7, 2021. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- ^ "The 48th Academy Awards". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on July 1, 2019. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- ^ a b Michel, Lincoln (October 22, 2018). "The Shining—Maybe the Scariest Movie of All Time—Is on Netflix". GQ. Archived from the original on November 9, 2020. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- ^ Marsh, Calum (January 13, 2016). "The man behind the Razzies: 'Brian de Palma had no talent'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on November 8, 2020. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- ^ Billson, Anne (October 22, 2012). "The Shining: No 5 best horror film of all time". The Guardian. Archived from the original on June 13, 2020. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- ^ Greene, Andy (October 8, 2014). "Readers' Poll: The 10 Best Horror Movies of All Time". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on June 14, 2020. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- ^ a b Wise, Damon (August 1, 2017). "How we made Stanley Kubrick's Full Metal Jacket". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- ^ Brody, Richard (March 24, 2011). "Archive Fever: Stanley Kubrick and "The Aryan Papers"". The New Yorker. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- ^ Turan, Kenneth (July 16, 1999). "'Eyes' That See Too Much". The Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on April 21, 2019. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (July 7, 2011). "He just wanted to become a real boy". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on May 17, 2019. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- ^ "Spielberg will finish Kubrick's artificial intelligence movie". The Guardian. London. March 15, 2000. Archived from the original on March 23, 2019. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- ^ Johnson, Ted (February 2, 1997). "DGA gives Kubrick D.W. Griffith Award". Variety. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved January 6, 2021.

- ^ "Steven Spielberg to Receive Lifetime Achievement Award, DGA's Highest Honor". Directors Guild of America. Archived from the original on November 28, 2019. Retrieved January 6, 2021.

- ^ "Britannia Awards Honorees". BAFTA. Archived from the original on November 17, 2020. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- ^ Torres, Vanessa (July 21, 1999). "BAFTA dubs kudo after Kubrick". Variety. Archived from the original on March 16, 2016. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- ^ "Full List of BAFTA Fellows". BAFTA. Archived from the original on August 28, 2020. Retrieved August 15, 2020.

- ^ "Fear and Desire". Turner Classic Movies. Archived from the original on August 2, 2020. Retrieved August 17, 2020.

- ^ "Killer's Kiss". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on October 4, 2019. Retrieved January 6, 2020.

- ^ "Paths of Glory". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved January 6, 2021.

- ^ "Paths of Glory". The Criterion Collection. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved January 6, 2021.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (May 3, 1991). "Spartacus". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on August 9, 2020. Retrieved August 15, 2020.

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (June 14, 1962). "Screen: Lolita, Vladimir Nabokov's Adaptation of His Novel:Sue Lyon and Mason in Leading Roles". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 4, 2018. Retrieved January 6, 2021.

- ^ Trubikhina, Julia (2007). "Struggle for the Narrative: Nabokov and Kubrick's Collaboration on the "Lolita" Screenplay". Ulbandus Review. Columbia University Slavic Department. 10: 149–172. JSTOR 25748170. Retrieved January 6, 2021.

- ^ Schlosser, Eric (January 17, 2014). "Almost Everything in "Dr. Strangelove" Was True". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- ^ McKie, Robin (April 15, 2018). "Kubrick's '2001',: the film that haunts our dreams of space". The Guardian. Archived from the original on December 27, 2020. Retrieved January 6, 2021.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (March 27, 1997). "2001: A Space Odyssey". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on January 21, 2018. Retrieved January 6, 2021.

- ^ Whatley, Jack (October 15, 2020). "Stanley Kubrick's secret cameo in 2001: A Space Odyssey". Far Out. Archived from the original on October 26, 2020. Retrieved January 6, 2021.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (February 2, 1972). "A Clockwork Orange". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on July 1, 2019. Retrieved January 6, 2020.

- ^ Gilbey, Ryan (July 14, 2016). "Stanley Kubrick's Barry Lyndon: 'It puts a spell on people'". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved August 15, 2020.

- ^ "Barry Lyndon". Turner Classic Movies. Archived from the original on October 17, 2018. Retrieved August 15, 2020.

- ^ Lewis Gilbert, Ken Adam, Michael G. Wilson, Christopher Wood. The Spy Who Loved Me audio commentary.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (June 8, 2006). "Isolated madness". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on January 4, 2011. Retrieved August 15, 2020.

- ^ Nicholson, Amy (July 17, 2014). "Eyes Wide Shut at 15: Inside the Epic, Secretive Film Shoot that Pushed Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman to Their Limits". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved January 6, 2021.

- ^ "Eyes Wide Shut". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved January 6, 2021.

- ^ A.I. Artificial Intelligence. Warner Bros. Pictures. 2001. Event occurs at c. 149 minutes.

- ^ Brake, Scott (May 10, 2001). "Spielberg Talks About the Genesis of A.I.". IGN. Archived from the original on May 22, 2011. Retrieved August 4, 2008.

- ^ Far Out Staff (December 28, 2021). "Watch Stanley Kubrick's first-ever short film 'Day of the Fight'". Far Out. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved January 6, 2021.

- ^ Bernstein, Jeremy (November 5, 1966). "How About a Little Game?". New Yorker. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved January 6, 2021.

- ^ "Flying Padre". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on September 26, 2020. Retrieved August 15, 2020.

- ^ "The Flying Padre". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved March 14, 2021.

- ^ Fenwick, James (2000-12-18). "Stanley Kubrick and Richard de Rochemont". Stanley Kubrick Produces. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 9781978814899.

- ^ a b Kolker, Robert P.; Abrams, Nathan (2019-05-08). "Introduction". Eyes Wide Shut: Stanley Kubrick and the Making of His Final Film. Oxford University Press. p. 3. ISBN 9780190678050.

- ^ Graser, Mark (August 12, 2013). "Stanley Kubrick's First Color Film, The Seafarers, Streaming on IndieFlix". Variety. Archived from the original on July 3, 2017. Retrieved January 6, 2021.

- ^ 백스터 1997, 50페이지

- ^ "Omnibus". Television Academy Interviews. 22 October 2017. Retrieved 29 August 2023.

- ^ Fagerholm, Matt (July 16, 2015). "A Trip Through Film History with Norman Lloyd". rogerebert.com. Retrieved 29 August 2023.

- ^ King, Susan (12 April 2014). "UCLA honors the daring work of Norman Lloyd". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "Norman Lloyd". Television Academy Interviews. 22 October 2017. Retrieved 29 August 2023.

- ^ a b Duncan 2003, 26-27페이지

- ^ Stafford, Jeff (30 December 2018). "Fear and Desire 1953". A Strange Love of Tangled Writing: Stanley Kubrick's Films and Their Literary Sources. Retrieved 29 August 2023.

- ^ Hughes, William C. (2004). James Agee, Omnibus, and Mr. Lincoln: The Culture of Liberalism and the Challenge of Television, 1952-1953. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-5175-7.

- ^ "Stanley Kubrick". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved February 14, 2021.

- ^ "Stanley Kubrick". Metacritic. Archived from the original on January 14, 2021. Retrieved February 14, 2021.

원천

- Baxter, John (1997). Stanley Kubrick: A Biography. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-00-638445-8.

- Duncan, Paul (2003). Stanley Kubrick: The Complete Films. Taschen GmbH. ISBN 978-3-8365-2775-0.

- Hughes, David (2000). The Complete Kubrick. Virgin Publishing. ISBN 0-7535-0452-9.

- Kagan, Norman (2000). The Cinema of Stanley Kubrick. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 0-8264-1243-2.

- Naremore, James (2007). On Kubrick. British Film Institute. ISBN 978-1-84457-142-0.

- Sperb, Jason (2006). The Kubrick Facade: Faces and Voices in the Films of Stanley Kubrick. The Scarecrow Press, Inc. ISBN 081085855X.