시냅스 전 억제

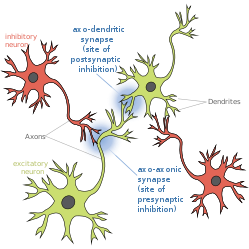

Presynaptic inhibition시냅스 전 억제는 억제 뉴런이 다른 뉴런의 축삭(축축방향 시냅스)에 시냅스 입력을 제공하여 활동전위를 발사할 가능성을 낮추는 현상이다.시냅스 전 억제는 GABA와 같은 억제성 신경전달물질이 축삭 말단의 GABA 수용체에 작용할 때 발생합니다.시냅스 전 억제는 감각 [1]뉴런 사이에서 흔하다.

기능.

통증, 고유감각, 체감각과 같은 감각 자극은 일차 구심성 섬유에 의해 감지된다.체질 감각 뉴런은 인체의 현재 상태에 대한 정보(예: 온도, 통증, 압력, 위치 등)를 인코딩합니다.척추동물의 경우, 이러한 1차 구심성 섬유는 척수, 특히 등쪽 뿔 영역에서 흥분성 뉴런과 억제성 뉴런을 포함한 다양한 하류 타겟에 시냅스를 형성합니다.1차 구심성 섬유와 그 표적 사이의 시냅스는 감각 정보가 [2]변조되는 첫 번째 기회이다.1차 구심성 섬유는 돌기를 따라 많은 수용체를 포함하고 있어 복잡한 변조에 잘 적응한다.1차 구심성 섬유에 의해 감지되는 환경 자극의 지속적인 유입은 자극을 강화하거나 감소시키기 위해 변조될 수 있다(게이트 제어 이론 및 이득 제어 생물학적 참조).기본적으로 무한한 자극이 존재하기 때문에 이러한 신호를 적절히 필터링해야 합니다.

체질감소증, 특히 통증이 억제되는지 여부를 테스트하기 위해 과학자들은 설치류의 척수에 화학물질을 주입하여 일차 억제 신경전달물질의 활동을 차단했다. (바이쿨린, GABA 수용체[3] 작용제)그들은 약리학적으로 GABA 수용체를 차단하는 것이 실제로 통증에 대한 인식을 증가시킨다는 것을 발견했다. 즉, GABA는 보통 [4]통증에 대한 인식을 감소시킨다.

GABA가 1차 구심성 파이버에서 그 하류 타깃으로의 시냅스 전송을 변조하는 방법은 논란이 되고 있습니다(다음 메커니즘 섹션 참조).역학에 관계없이 GABA는 1차 구심성 섬유 시냅스 방출 가능성을 감소시키는 억제 역할을 한다.

일반적인 쾌적함을 유지하기 위해서는 1차 구심성 섬유를 변조하는 것이 중요합니다.한 연구는 노크셉터에 특정 유형의 GABA 수용체가 없는 동물들은 [5]통증에 과민하여 진통제로써 시냅스 전 억제 기능을 뒷받침하는 것으로 나타났다.알로디니아와 같은 특정 병리학적 조건은 비변조 노시셉터 발화에 의해 발생하는 것으로 생각된다.축축한 통증 외에도, 시냅스 전 억제 장애는 척수 [6]손상 후 경련성, 간질, 자폐증, 연약한 X [7][8][9][10][11]증후군과 같은 많은 신경학적 장애와 관련이 있다. 뇌전증

메커니즘

1차 감각 구심체는 말단을 따라 GABA 수용체를 포함한다(표 1 참조).[12]GABA 수용체는 5개의 GABA 수용체 서브유닛의 조립에 의해 형성되는 리간드 게이트 염화물 채널이다.감각 구심 축삭을 따라 GABA 수용체가 존재할 뿐만 아니라, 시냅스 전 말단은 염화물 농도가 높은 독특한 이온성 조성물을 가지고 있다.이는 높은 세포 내 [13]염화물을 유지하는 양이온-염산염 공수송체(예: NKCC1) 때문이다.

일반적으로 GABA 수용체가 활성화되면 염화물 유입을 일으켜 세포를 과분극시킨다.단, 1차 구심성 섬유에서는 시냅스 전 말단에서의 고농도의 염화물과 그에 따른 반전전위 변화 때문에 GABA 수용체 활성화는 실제로 염화물 유출을 초래하여 탈분극화를 초래한다.이러한 현상을 일차 구심 탈분극(PAD)[14][15]이라고 합니다.구심 축삭에서 GABA 유도 탈분극 잠재력은 고양이에서 곤충에 이르기까지 많은 동물에서 입증되었다.흥미롭게도, 탈분극 잠재력에도 불구하고 축삭을 따른 GABA 수용체 활성화는 여전히 신경전달물질 방출을 감소시키고, 따라서 여전히 억제된다.

이 역설의 이면에는 메커니즘을 제안하는 4가지 가설이 있습니다.

- 탈분극막은 말단에서 전압 게이트 나트륨 채널의 불활성화를 유발하므로 활동 전위가 [12][16][17]전파되지 않습니다.

- 개방된 GABA 수용체 채널은 분로 역할을 하며,[12][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23] 단자로 전파되는 대신 전류가 방산됩니다.

- 탈분극막은 전압 게이트 칼슘 채널의 불활성화를 유발하여 시냅스에서 칼슘 유입을 방지합니다([12][17][19][20][24]신경 전달에 필수적임).

- 말단에서의 탈분극은 반염색 스파이크(축삭에서 생성되어 소마를 향해 이동하는 활동 전위)를 생성하며, 이는 정염색 스파이크(세포의 소마에서 축삭 말단으로 이동하는 활동 전위)가 [18]전파되는 것을 방지할 수 있다.

시냅스 전 억제 발견 이력

1933년: 그래저와 그레이엄은 감각 축삭[25] 말단에서 시작된 탈분극 현상을 관찰했다.

1938년: Baron & Matthews는 감각 축삭 말단과 복부근에서[26] 시작된 탈분극 현상을 관찰했다.

1957년 : Frank & Footes가 "시냅스 전 억제"[27]라는 용어를 만들었습니다.

1961년: Eccles, Eccles 및 Magni는 등근전위(DRP)가 감각 축삭 말단의 탈분극에서 비롯되었다고 판단했습니다.

레퍼런스

- ^ McGann JP (July 2013). "Presynaptic inhibition of olfactory sensory neurons: new mechanisms and potential functions". Chemical Senses. 38 (6): 459–474. doi:10.1093/chemse/bjt018. PMC 3685425. PMID 23761680.

- ^ Comitato A, Bardoni R (January 2021). "Presynaptic Inhibition of Pain and Touch in the Spinal Cord: From Receptors to Circuits". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 22 (1): 414. doi:10.3390/ijms22010414. PMC 7795800. PMID 33401784.

- ^ Manske RH (September 1932). "The Alkaloids of Fumaraceous Plants: II. Dicentra Cucullaria (L.) Bernh". Canadian Journal of Research. 7 (3): 265–269. doi:10.1139/cjr32-078. ISSN 1923-4287.

- ^ Roberts LA, Beyer C, Komisaruk BR (November 1986). "Nociceptive responses to altered GABAergic activity at the spinal cord". Life Sciences. 39 (18): 1667–74. doi:10.1016/0024-3205(86)90164-5. PMID 3022091.

- ^ Price TJ, Cervero F, Gold MS, Hammond DL, Prescott SA (April 2009). "Chloride regulation in the pain pathway". Brain Research Reviews. 60 (1): 149–170. doi:10.1016/j.brainresrev.2008.12.015. PMC 2903433. PMID 19167425.

- ^ Caron, Guillaume; Bilchak, Jadwiga N.; Côté, Marie‐Pascale (2020). "Direct evidence for decreased presynaptic inhibition evoked by PBSt group I muscle afferents after chronic SCI and recovery with step‐training in rats". The Journal of Physiology. 598 (20): 4621–4642. doi:10.1113/JP280070. ISSN 0022-3751.

- ^ Deidda G, Bozarth IF, Cancedda L (2014). "Modulation of GABAergic transmission in development and neurodevelopmental disorders: investigating physiology and pathology to gain therapeutic perspectives". Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience. 8: 119. doi:10.3389/fncel.2014.00119. PMC 4033255. PMID 24904277.

- ^ Zeilhofer HU, Wildner H, Yévenes GE (January 2012). "Fast synaptic inhibition in spinal sensory processing and pain control". Physiological Reviews. 92 (1): 193–235. doi:10.1152/physrev.00043.2010. PMC 3590010. PMID 22298656.

- ^ Lee E, Lee J, Kim E (May 2017). "Excitation/Inhibition Imbalance in Animal Models of Autism Spectrum Disorders". Biological Psychiatry. 81 (10): 838–847. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2016.05.011. PMID 27450033.

- ^ D'Hulst C, Kooy RF (August 2007). "The GABAA receptor: a novel target for treatment of fragile X?". Trends in Neurosciences. 30 (8): 425–431. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2007.06.003. PMID 17590448. S2CID 7340813.

- ^ Benarroch EE (February 2007). "GABAA receptor heterogeneity, function, and implications for epilepsy". Neurology. 68 (8): 612–614. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000255669.83468.dd. PMID 17310035. S2CID 11101571.

- ^ a b c d Guo D, Hu J (December 2014). "Spinal presynaptic inhibition in pain control". Neuroscience. 283: 95–106. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.09.032. PMID 25255936.

- ^ Kahle KT, Staley KJ, Nahed BV, Gamba G, Hebert SC, Lifton RP, Mount DB (September 2008). "Roles of the cation-chloride cotransporters in neurological disease". Nature Clinical Practice. Neurology. 4 (9): 490–503. doi:10.1038/ncpneuro0883. PMID 18769373. S2CID 15424963.

- ^ Price TJ, Cervero F, Gold MS, Hammond DL, Prescott SA (April 2009). "Chloride regulation in the pain pathway". Brain Research Reviews. 60 (1): 149–170. doi:10.1016/j.brainresrev.2008.12.015. PMC 2903433. PMID 19167425.

- ^ Willis WD (February 1999). "Dorsal root potentials and dorsal root reflexes: a double-edged sword". Experimental Brain Research. 124 (4): 395–421. doi:10.1007/s002210050637. PMID 10090653. S2CID 40738560.

- ^ a b Cattaert D, El Manira A (July 1999). "Shunting versus inactivation: analysis of presynaptic inhibitory mechanisms in primary afferents of the crayfish". The Journal of Neuroscience. 19 (14): 6079–6089. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-14-06079.1999. PMC 6783106. PMID 10407044.

- ^ a b c Willis WD (2006-02-01). "John Eccles' studies of spinal cord presynaptic inhibition". Progress in Neurobiology. 78 (3–5): 189–214. doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2006.02.007. PMID 16650518. S2CID 38669996.

- ^ a b Cattaert D, Libersat F, El Manira A (February 2001). "Presynaptic inhibition and antidromic spikes in primary afferents of the crayfish: a computational and experimental analysis". The Journal of Neuroscience. 21 (3): 1007–1021. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-03-01007.2001. PMC 6762302. PMID 11157086.

- ^ a b Panek I, French AS, Seyfarth EA, Sekizawa S, Torkkeli PH (July 2002). "Peripheral GABAergic inhibition of spider mechanosensory afferents". The European Journal of Neuroscience. 16 (1): 96–104. doi:10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.02065.x. PMID 12153534. S2CID 20750558.

- ^ a b French AS, Panek I, Torkkeli PH (June 2006). "Shunting versus inactivation: simulation of GABAergic inhibition in spider mechanoreceptors suggests that either is sufficient". Neuroscience Research. 55 (2): 189–196. doi:10.1016/j.neures.2006.03.002. PMID 16616790. S2CID 2099107.

- ^ Miller RJ (1998). "Presynaptic receptors". Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology. 38: 201–227. doi:10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.38.1.201. PMID 9597154.

- ^ Zhang SJ, Jackson MB (March 1995). "Properties of the GABAA receptor of rat posterior pituitary nerve terminals". Journal of Neurophysiology. 73 (3): 1135–1144. doi:10.1152/jn.1995.73.3.1135. PMID 7608760.

- ^ Zhang SJ, Jackson MB (March 1995). "GABAA receptor activation and the excitability of nerve terminals in the rat posterior pituitary". The Journal of Physiology. 483 (3): 583–595. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020608. PMC 1157804. PMID 7776245.

- ^ Graham B, Redman S (February 1994). "A simulation of action potentials in synaptic boutons during presynaptic inhibition". Journal of Neurophysiology. 71 (2): 538–549. doi:10.1152/jn.1994.71.2.538. PMID 8176423.

- ^ Gasser HS, Graham HT (January 1933). "Potentials produced in the spinal cord by stimulation of dorsal roots". American Journal of Physiology. 103 (2): 303–320. doi:10.1152/ajplegacy.1933.103.2.303.

- ^ Barron DH, Matthews BH (April 1938). "The interpretation of potential changes in the spinal cord". The Journal of Physiology. 92 (3): 276–321. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.1938.sp003603. PMC 1395290. PMID 16994975.

- ^ Frank K, Fuortes MG (1957). "Presynaptic and Postsynaptic inhibition of monsynaptic reflexes". Federation Proceedings. 16: 39–40.

- ^ Eccles JC, Eccles RM, Magni F (November 1961). "Central inhibitory action attributable to presynaptic depolarization produced by muscle afferent volleys". The Journal of Physiology. 159: 147–166. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.1961.sp006798. PMC 1359583. PMID 13889050.