비연골세포

Nasal chondrocytes코 연골세포(NC)는 코 격막의 히알린 연골에 존재하며 사실 조직 내의 유일한 세포 유형이다.관절 연골에 존재하는 연골세포와 유사하게 NC는 글리코사미노글리칸과 [1]콜라겐과 같은 세포외 기질 단백질을 발현한다.

자연환경에서

태어날 때 vomer "anlage"를 제외하고 코 격막은 완전히 연골이다.생후 첫해 후반에는 연골내 [2]골화 과정에 의해 중격은 후외방향으로 서서히 골화된다.인간 비중격의 나머지 연골 부분(히알린 연골)은 세포 크기 및 세포 외 기질의 국소적인 차이와 관련하여 특정한 3차원 조직을 가지고 있다.연골의 외측영역은 NC가 많고 작고 평탄하며 표면에 평행한 방향이다.중간영역 및 중앙영역에서는 NC는 구상체이며 밀도가 낮고 연골표면에 [3]수직으로 배열되어 있다.연골 매트릭스는 주로 II형 콜라겐(90~95%), IX형 콜라겐과 XI형 콜라겐도 [4]소량 검출된다.코 연골은 [5]연골과 평행하게 이어지는 여러 층의 결합 조직 섬유(주로 I형 콜라겐에 기초함)로 구성된 연골막에 단단히 연결되어 있습니다.

조직 공학 응용 프로그램

관절 연골세포는 일반적으로 관절 연골 수복을 위한 연골 조직 엔지니어링 전략에 사용되는 세포 유형이다.NC는 글리코사미노글리칸, 콜라겐 등 히알린 연골 특이 세포외 기질 단백질도 발현할 수 있어 최근에는 연골조직의 시험관내 공학적 용도로도 사용되고 있다.

세포 분리

코 연골 채취는 침습성이 최소이며, 국소 마취 하에 외래 시술로 수행될 수 있으며,[6] 최소 질병률과 관련이 있습니다.NC는 콜라게나아제 타입 I, II 또는 IV(0.15%에서 0.6%까지 다양한 조합 및 농도)를 이용한 효소적 소화에 의해 단독으로 또는 프로나아제(0.2% - 1%)[7][8][9][10][11][12]와 함께 초기 짧은 삽관 전 단계 후에 비중격 연골 생체검사로부터 분리될 수 있다.비강 연골의 효소 소화 후 세포 수율은 조직의 [7][12]2,100 - 3,700 cells/mg으로 추정되었다.또, NC는 코연골 [8]파편의 성장 이상 배양으로 분리할 수 있다.

세포 확장

중격연골 생체검사에서 분리된 후 기존 시험관내 세포배양법(플라스크 또는 페트리 접시의 단층배양법)으로 NC를 광범위하게 확장할 수 있다.NC의 증식률은 TGF-베타, FGF-2와[12][13] 같은 특정 성장인자 또는 인슐린-트랜스페린-셀레늄과 [7]같은 배양보조식품의 존재 하에서 증가하는 것으로 보고되었다.자가 혈청을 포함한 배지에서 배양된 NC는 태아 소 [13]혈청을 보충한 배지에서 배양된 NC와 유사한 증식 속도를 보인다.노년층에서 유래한 관절 연골세포는 젊은 기증자보다 증식능력이 낮은 것으로 나타났지만 NC는 연령 의존성이 현저히 [13][14]낮은 것으로 나타났다.

차별화

인체 내 다른 부위에 있는 히알린 연골조직의 다른 연골세포와 마찬가지로 NC는 단층 배양 중에 세포 탈분화 과정을 거친다.NC 탈분화는 섬유아세포 형태학의 점진적인 획득, 미분화 간엽세포 표현형과 관련된 단백질의 발현(예를 들어 I형 콜라겐과 베르시칸) 및 히알린 연골 단백질의 발현 감소(예를 들어 II형 콜라겐과 어그레칸)[9]로 특징지을 수 있다.그러나 NC는 보다 생리적인 3차원 환경으로 전환되면 재분화할 수 있습니다.상기 연골(, )는 폴리머스칼렛에틸렌스칼렛(,18년)(,18년) (12] (18년) (18년)(,18년) (18년)[24] 또는 혜성산은[1][1][14][25]재분화 중 특정 성장인자(예: TGF-β, IGF-1 및 GDF-5)에 의한 보충은 생성된 [20][26]구조의 생체역학 특성뿐만 아니라 글리코사미노글리칸(GAG) 및 II형 콜라겐의 축적을 향상시키는 것으로 나타났다.

NC 재분화 과정에서 유사한 [14][26][27]유효성을 가진 태아 소 혈청 대신 자가 혈청이 사용되기도 했다.NC에 대한 관절 연골세포의 재분화를 직접 비교한 연구는 NC의 연골 형성 용량이 기증자 관련 [13][14]의존성이 낮은 관절[24][25][28] 연골세포보다 더 높고 더 재현 가능한 것으로 나타났다.또한 NC는 최근 신경외피 [29]기원에 의한 연쇄복제 후 연골조직을 형성할 수 있는 자가재생능력의 특징을 보이고 있다.

동물 연구

연골 재건을 위한 NC 기반 조직 엔지니어링 구조의 임상 잠재력에 대한 원론적 증거를 제공하기 위해 다양한 동물 모델을 사용하여 임상 전 조사가 수행되었습니다.인간 NC 공학적 이식편의 성숙도는 종종 누드 생쥐의 피하 주머니에서 평가되었다. 즉, 혈관이 매우 풍부하고 [30][31]연골 생성에 대한 허용성이 높지만 유도성은 없는 환경이다.이러한 이소성 생체내 [21][13][18][22][32][33][34]모델에서 연골 매트릭스 생성의 범위와 NC 기반 구조의 기계적 특성이 증가하는 것으로 보고되었다.임상적으로 관련성이 있는 큰 크기의 NC 기반 조직 [26]이식편을 생성하기 위한 다른 생산 방법의 효과를 테스트하기 위해 이소성 마우스 모델도 사용되었다.

이러한 모델은 통찰력 있는 결과를 얻을 수 있지만, 누드 마우스는 유의한 면역 반응을 이끌어낼 수 없으며, 따라서 이러한 연구는 면역적합 숙주에 이식된 공학적 중격 연골의 예후를 예측할 수 없다.대안으로, 코 격막 복구를 연구하기 위해 직교 랫드 모델이 확립되었습니다.이 모델에서는 먼저 중격 연골을 천공하여 결점을 만든 후 동일한[35] 수술 과정에서 결함에 이식된 인공 연골 이식술을 시행하였다.

관절연골 결함의 복구를 연구하기 위해 직교 대형 동물 모델을 이용하여 NC 기반의 인공 연골 이식편을 염소의 콘다일에 이식하였다.본 연구에서는 NC가 관절연골 결함의 수복에 직접 기여하여 인공관절연골세포 기반 [36]이식편과 비교하여 우수한 결과를 얻었다고 판단하였다.

임상 응용 프로그램

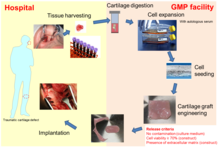

자가 NC에 기반한 인공연골조직은 최근 성형외과 의사들에 의해 코 연골 결함의 재건을 위해 사용되고 있다.최초 임상시험(ClinicalTrials.gov, 번호 NCT01242618)[29]에서 피부종양 절제 후 코의 경골 소엽 재건을 위한 자가 이식편으로서 NC를 기반으로 한 조직공학적 연골 이식편입니다(오른쪽 그림 참조).그 결과 엔지니어링된 이식편이 구조, 기능 및 미적 만족을 완전히 이끌어 낼 수 있음이 입증되었습니다.또한 비강 연골 생검 채취는 침습이 최소화되었기 때문에 국소 마취 하에 외래 시술로 수행될 수 있었고,[6] 따라서 최소 질병률과 관련이 있었다.

여러 연구는 NC가 다친 무릎의 전형적인 환경적 특징(예: 염증 분자에 대한 반응, 기계적 하중 및 유전적 분자 특징)[24][25][30]과 양립할 수 있다는 것을 보여주었다.따라서 코 연골세포는 관절 연골 결손의 복구를 위한 대체 세포원으로 제안되어 왔다.무릎 연골 결함의 재생을 위해 자가 비강 연골세포를 기반으로 조직 공학적 연골 이식편의 안전성과 타당성을 테스트하기 위해 1단계 임상시험(ClinicalTrials.gov, 번호 NCT 01605201)이 수행되었다.이 연구의 최초 10명의 환자에 대한 임상 관찰 결과, 시술의 안전성과 실현 가능성뿐만 아니라 자기공명영상(MRI) 및 지연된 연골의 가돌리늄 강화 자기공명영상(dGEMRIC) 데이터,또한 24개월 [37]후 임상 점수의 현저한 개선과 히알린 복구 조직의 재생으로 나타나는 치료 효과의 유망한 결과를 보였다.이 연구를 바탕으로, 외상 무릎 연골 결함의 복구를 위한 NC 기반 연골 이식편의 효과를 평가하기 위해 다중 센터 II 임상 시험이 시작되었고 현재 진행 중입니다(BIO-CHIP, Horizon 2020 프로그램을 통해 유럽연합의 자금 지원, 681103번).

레퍼런스

- ^ a b Candrian C, Vonwil D, Barbero A, Bonacina E, Miot S, Farhadi J, et al. (January 2008). "Engineered cartilage generated by nasal chondrocytes is responsive to physical forces resembling joint loading". Arthritis and Rheumatism. 58 (1): 197–208. doi:10.1002/art.23155. PMID 18163475.

- ^ Pelttari K, Mumme M, Barbero A, Martin I (October 2017). "Nasal chondrocytes as a neural crest-derived cell source for regenerative medicine". Current Opinion in Biotechnology. 47: 1–6. doi:10.1016/j.copbio.2017.05.007. PMID 28551498.

- ^ Schultz-Coulon HJ, Eckermeier L (January 1976). "Zum Postnatalen Wachstum Der Nasenscheidewand" [Postnatal growth of nasal septum]. Acta Oto-Laryngologica (in German). 82 (1–2): 131–142. doi:10.3109/00016487609120872. PMID 948977.

- ^ Popko M, Bleys RL, De Groot JW, Huizing EH (June 2007). "Histological structure of the nasal cartilages and their perichondrial envelope. I. The septal and lobular cartilage". Rhinology. 45 (2): 148–152. PMID 17708463.

- ^ Holden PK, Liaw LH, Wong BJ (July 2008). "Human nasal cartilage ultrastructure: characteristics and comparison using scanning electron microscopy". The Laryngoscope. 118 (7): 1153–1156. doi:10.1097/MLG.0b013e31816ed5ad. PMC 4151991. PMID 18438266.

- ^ a b Aksoy F, Yildirim YS, Demirhan H, Özturan O, Solakoglu S (January 2012). "Structural characteristics of septal cartilage and mucoperichondrium". The Journal of Laryngology and Otology. 126 (1): 38–42. doi:10.1017/S0022215111002404. PMID 21888752.

- ^ a b c d Siegel NS, Gliklich RE, Taghizadeh F, Chang Y (February 2000). "Outcomes of septoplasty". Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. 122 (2): 228–232. doi:10.1016/S0194-5998(00)70244-0. PMID 10652395. S2CID 43019892.

- ^ a b Chua KH, Aminuddin BS, Fuzina NH, Ruszymah BH (June 2005). "Insulin-transferrin-selenium prevent human chondrocyte dedifferentiation and promote the formation of high quality tissue engineered human hyaline cartilage". European Cells & Materials. 9: 58–67, discussion 67. doi:10.22203/ecm.v009a08. PMID 15962238.

- ^ a b c Elsaesser AF, Schwarz S, Joos H, Koerber L, Brenner RE, Rotter N (2016). "Characterization of a migrative subpopulation of adult human nasoseptal chondrocytes with progenitor cell features and their potential for in vivo cartilage regeneration strategies". Cell & Bioscience. 6: 11. doi:10.1186/s13578-016-0078-6. PMC 4752797. PMID 26877866.

- ^ Homicz MR, Schumacher BL, Sah RL, Watson D (November 2002). "Effects of serial expansion of septal chondrocytes on tissue-engineered neocartilage composition". Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. 127 (5): 398–408. doi:10.1067/mhn.2002.129730. PMID 12447233. S2CID 24779895.

- ^ a b Liese J, Marzahn U, El Sayed K, Pruss A, Haisch A, Stoelzel K (June 2013). "Cartilage tissue engineering of nasal septal chondrocyte-macroaggregates in human demineralized bone matrix". Cell and Tissue Banking. 14 (2): 255–266. doi:10.1007/s10561-012-9322-4. PMID 22714645. S2CID 254381658.

- ^ a b c d Shafiee A, Kabiri M, Ahmadbeigi N, Yazdani SO, Mojtahed M, Amanpour S, Soleimani M (December 2011). "Nasal septum-derived multipotent progenitors: a potent source for stem cell-based regenerative medicine". Stem Cells and Development. 20 (12): 2077–2091. doi:10.1089/scd.2010.0420. PMID 21401444.

- ^ a b c d e Wolf F, Haug M, Farhadi J, Candrian C, Martin I, Barbero A (February 2008). "A low percentage of autologous serum can replace bovine serum to engineer human nasal cartilage". European Cells & Materials. 15: 1–10. doi:10.22203/ecm.v015a01. PMID 18247273.

- ^ a b c d e Vinatier C, Magne D, Moreau A, Gauthier O, Malard O, Vignes-Colombeix C, et al. (January 2007). "Engineering cartilage with human nasal chondrocytes and a silanized hydroxypropyl methylcellulose hydrogel". Journal of Biomedical Materials Research. Part A. 80 (1): 66–74. doi:10.1002/jbm.a.30867. PMID 16958048.

- ^ Bujía J, Pitzke P, Kastenbauer E, Wilmes E, Hammer C (1996). "Effect of growth factors on matrix synthesis by human nasal chondrocytes cultured in monolayer and in agar". European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology. 253 (6): 336–340. doi:10.1007/BF00178288. PMID 8858257. S2CID 12243849.

- ^ Peñuela L, Wolf F, Raiteri R, Wendt D, Martin I, Barbero A (June 2014). "Atomic force microscopy to investigate spatial patterns of response to interleukin-1beta in engineered cartilage tissue elasticity". Journal of Biomechanics. 47 (9): 2157–2164. doi:10.1016/j.jbiomech.2013.10.056. PMID 24290139.

- ^ Alexander TH, Sage AB, Schumacher BL, Sah RL, Watson D (September 2006). "Human serum for tissue engineering of human nasal septal cartilage". Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. 135 (3): 397–403. doi:10.1016/j.otohns.2006.05.029. PMID 16949971. S2CID 383736.

- ^ a b Rotter N, Bonassar LJ, Tobias G, Lebl M, Roy AK, Vacanti CA (August 2002). "Age dependence of biochemical and biomechanical properties of tissue-engineered human septal cartilage". Biomaterials. 23 (15): 3087–3094. doi:10.1016/s0142-9612(02)00031-5. PMID 12102179.

- ^ a b Chang AA, Reuther MS, Briggs KK, Schumacher BL, Williams GM, Corr M, et al. (January 2012). "In vivo implantation of tissue-engineered human nasal septal neocartilage constructs: a pilot study". Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. 146 (1): 46–52. doi:10.1177/0194599811425141. PMC 4352411. PMID 22031592.

- ^ a b Homicz MR, Chia SH, Schumacher BL, Masuda K, Thonar EJ, Sah RL, Watson D (January 2003). "Human septal chondrocyte redifferentiation in alginate, polyglycolic acid scaffold, and monolayer culture". The Laryngoscope. 113 (1): 25–32. doi:10.1097/00005537-200301000-00005. PMID 12514377. S2CID 24972306.

- ^ a b Tay AG, Farhadi J, Suetterlin R, Pierer G, Heberer M, Martin I (2004). "Cell yield, proliferation, and postexpansion differentiation capacity of human ear, nasal, and rib chondrocytes". Tissue Engineering. 10 (5–6): 762–770. doi:10.1089/1076327041348572. PMID 15265293.

- ^ a b van Osch GJ, Marijnissen WJ, van der Veen SW, Verwoerd-Verhoef HL (2001). "The potency of culture-expanded nasal septum chondrocytes for tissue engineering of cartilage". American Journal of Rhinology. 15 (3): 187–192. doi:10.2500/105065801779954166. PMID 11453506. S2CID 24763664.

- ^ Naumann A, Rotter N, Bujía J, Aigner J (1998). "Tissue engineering of autologous cartilage transplants for rhinology". American Journal of Rhinology. 12 (1): 59–63. doi:10.2500/105065898782102972. PMID 9513661. S2CID 37632669.

- ^ a b c Malda J, Kreijveld E, Temenoff JS, van Blitterswijk CA, Riesle J (December 2003). "Expansion of human nasal chondrocytes on macroporous microcarriers enhances redifferentiation". Biomaterials. 24 (28): 5153–5161. doi:10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00428-9. PMID 14568432.

- ^ a b c Scotti C, Osmokrovic A, Wolf F, Miot S, Peretti GM, Barbero A, Martin I (February 2012). "Response of human engineered cartilage based on articular or nasal chondrocytes to interleukin-1β and low oxygen". Tissue Engineering. Part A. 18 (3–4): 362–372. doi:10.1089/ten.TEA.2011.0234. PMC 3267974. PMID 21902467.

- ^ a b c Farhadi J, Fulco I, Miot S, Wirz D, Haug M, Dickinson SC, et al. (December 2006). "Precultivation of engineered human nasal cartilage enhances the mechanical properties relevant for use in facial reconstructive surgery". Annals of Surgery. 244 (6): 978–85, discussion 985. doi:10.1097/01.sla.0000247057.16710.be. PMC 1856618. PMID 17122623.

- ^ do Amaral RJ, Pedrosa C, Kochem MC, Silva KR, Aniceto M, Claudio-da-Silva C, et al. (March 2012). "Isolation of human nasoseptal chondrogenic cells: a promise for cartilage engineering". Stem Cell Research. 8 (2): 292–299. doi:10.1016/j.scr.2011.09.006. PMID 22099383.

- ^ Barandun M, Iselin LD, Santini F, Pansini M, Scotti C, Baumhoer D, et al. (August 2015). "Generation and characterization of osteochondral grafts with human nasal chondrocytes". Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 33 (8): 1111–1119. doi:10.1002/jor.22865. PMID 25994595. S2CID 206142529.

- ^ a b Fulco I, Miot S, Haug MD, Barbero A, Wixmerten A, Feliciano S, et al. (July 2014). "Engineered autologous cartilage tissue for nasal reconstruction after tumour resection: an observational first-in-human trial". Lancet. 384 (9940): 337–346. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60544-4. PMID 24726477. S2CID 12217253.

- ^ a b Pelttari K, Pippenger B, Mumme M, Feliciano S, Scotti C, Mainil-Varlet P, et al. (August 2014). "Adult human neural crest-derived cells for articular cartilage repair". Science Translational Medicine. 6 (251): 251ra119. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3009688. PMID 25163479. S2CID 5520982.

- ^ Dell'Accio F, De Bari C, Luyten FP (July 2001). "Molecular markers predictive of the capacity of expanded human articular chondrocytes to form stable cartilage in vivo". Arthritis and Rheumatism. 44 (7): 1608–1619. doi:10.1002/1529-0131(200107)44:7<1608::AID-ART284>3.0.CO;2-T. PMID 11465712.

- ^ Scott MA, Levi B, Askarinam A, Nguyen A, Rackohn T, Ting K, et al. (March 2012). "Brief review of models of ectopic bone formation". Stem Cells and Development. 21 (5): 655–667. doi:10.1089/scd.2011.0517. PMC 3295855. PMID 22085228.

- ^ Bichara DA, Zhao X, Hwang NS, Bodugoz-Senturk H, Yaremchuk MJ, Randolph MA, Muratoglu OK (October 2010). "Porous poly(vinyl alcohol)-alginate gel hybrid construct for neocartilage formation using human nasoseptal cells". The Journal of Surgical Research. 163 (2): 331–336. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2010.03.070. PMID 20538292.

- ^ Dobratz EJ, Kim SW, Voglewede A, Park SS (2009). "Injectable cartilage: using alginate and human chondrocytes". Archives of Facial Plastic Surgery. 11 (1): 40–47. doi:10.1001/archfacial.2008.509. PMID 19153292.

- ^ Kim SW, Dobratz EJ, Ballert JA, Voglewede AT, Park SS (January 2009). "Subcutaneous implants coated with tissue-engineered cartilage". The Laryngoscope. 119 (1): 62–66. doi:10.1002/lary.20025. PMID 19117288. S2CID 22733319.

- ^ Bermueller C, Schwarz S, Elsaesser AF, Sewing J, Baur N, von Bomhard A, et al. (October 2013). "Marine collagen scaffolds for nasal cartilage repair: prevention of nasal septal perforations in a new orthotopic rat model using tissue engineering techniques". Tissue Engineering. Part A. 19 (19–20): 2201–2214. doi:10.1089/ten.TEA.2012.0650. PMC 3762606. PMID 23621795.

- ^ Elsaesser AF, Bermueller C, Schwarz S, Koerber L, Breiter R, Rotter N (June 2014). "In vitro cytotoxicity and in vivo effects of a decellularized xenogeneic collagen scaffold in nasal cartilage repair". Tissue Engineering. Part A. 20 (11–12): 1668–1678. doi:10.1089/ten.TEA.2013.0365. PMID 24372309.