촐라스 크릭

Chollas Creek| 촐라스 크릭 라스 촐라스 크릭 | |

|---|---|

샌디에고 링컨 파크 인근 47번가 바로 서쪽에 있는 촐라스 크릭의 사우스 포크. | |

| |

| 네이티브 네임 | 맷 엑스타트 (쿠미아이)[1][2] |

| 물리적 특성 | |

| 입 | 샌디에이고 만 |

• 위치 | (미국 캘리포니아주 샌디에이고 Norman Scott Rd의 NW 코너에서 바로 NW, San Diego, CA 92136) |

• 좌표들 | 32°41'15.5″N 117°07'44.8″W/32.687639°N 117.129111°W |

• 높낮이 | 해발 0.0피트(0.0m) |

| 길이 | 30 mi (48 km) |

촐라스 크리크(Chollas Creek)는 미국 캘리포니아주 샌디에이고 카운티에 있는 도시 크리크로 샌디에이고 만으로 [3]흘러들어갑니다.그것은 Las Chollas [4]Creek라고도 불립니다.Chollas Creek은 Lemon Grove와 La Mesa에서 발생하며, 그곳의 4개의 가지가 시작됩니다.바리오 [5]로건의 베이로 들어갑니다.그 개울의 [6]길이는 48킬로미터 입니다.이 개울은 두 개의 주요 포크로 나뉘며 남부 캘리포니아 [7]: 2–1 건기에는 건조할 수 있습니다.희귀 식물인 Juncus acutus leopoldii와 Iva hayesiana, 그리고 멸종 위기에 처한 캘리포니아 해안 그낫캐처를 [8][9]: 22 포함하여, 많은 식물, 동물, 그리고 수생 야생 동물 종들이 그 개울 또는 그 주변에 살고 있습니다.

이 개울은 기원전 1500년 이전부터 존재해 왔으며,[10]: 9 [11]: 43 [1] 이 개울가에 마을이 있던 쿠메야이족이 사용했습니다.1841년까지, 쿠메야이 마을은 [10]: 35 더 이상 개울 위에 존재하지 않았습니다.그 개울은 여러 번 물에 잠겼고, [12]근처에 사는 사람들에게 영향을 미쳤습니다.개울의 일부는 장갑을 끼거나 [9]: 1 수로를 만들었습니다.20세기 초에 지류에 댐이 건설되어 촐라스 [13]저수지를 형성했습니다.저수지의 존재로 인해 미국 해군은 북쪽에 [14]촐라스 하이츠 해군 라디오 방송국을 건설하게 되었습니다.

Chollas Creek 계곡은 "샌디에이고에서 가장 방치된 [15]유역 중 하나"로 묘사되어 왔습니다.수십 년 동안 그 개울은 오염, 불법 투기, 그리고 자연 [15]서식지의 파괴로 골치를 앓아왔습니다.그것은 높은 수준의 [16][17]오염물질 때문에 "손상된" 수역입니다.2002년, 샌디에고 시는 [18]그 개울을 재활시키기 위한 계획을 시작했습니다.2021년에는 하천 일대를 지역공원으로 조성하는 방안이 [19]채택됐습니다.

지리학

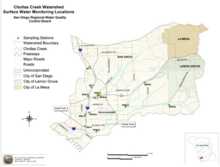

Chollas Creek 유역은 Lemon Grove의 La Messa 도시에서 8번 주간 고속도로의 남쪽으로 샌디에고까지 그리고 편입되지 않은 샌디에고 [20]카운티까지 뻗어 있습니다.그것은 또한 시티 하이츠, 엔칸토, 바리오 로건, 그리고 샌디에고 [17]동부와 남동부를 관통합니다.이 개울의 가장 높은 고도는 약 800피트(240m)[4]의 라 메사(La Mesa) 내에 있습니다.이 개울은 현재 해군 기지 샌디에이고 [10]: 11 내 샌디에이고 만으로 흘러들어갑니다.

수문학

Chollas Creek의 분수령은 면적이 16,270 에이커(652.8 km)이고,[7]: 2–1 두 개의 주요 포크로 나누어져 있습니다.이 두 포크의 누적 길이는 [6]선형으로 30마일(48km)입니다.사우스포크 유역은 6,997에이커(28.32km2)의 면적을 차지하고, 노스포크 유역은 9,276에이커(37.54km2)[7]: 2–1 [22]의 면적을 차지합니다.남부 캘리포니아의 건기인 5월부터 9월까지 몇 달 동안은 개울이 건조하거나 흐름이 거의 없을 수도 있습니다.샌디에고 만에서 가장 가까운 개울의 마일은 조수의 [7]: 2–1 영향을 받습니다.

동식물군

19세기 후반에,[10]: 12 거의 6피트 높이의 선인장들이 개울에 의해 만들어진 계곡에서 주목받았습니다.풍부하게 자라는 것이 관찰된 다른 식물 종으로는 Arctostylos, Seanothus, Eriodictionon Californicum, Vitis girdiana, 그리고 Diplacus [10]: 12 aurantiacus가 있습니다.

20세기 후반까지 개울을 따라 발견된 식물의 종류는 Eriogonum fasciculatum, Salvia apiana, Quercus dumosa, Malosma,[23]: 5 그리고 Diplacus aurantiacus였습니다.2015년에 이 개울의 남쪽 포크가 북쪽 포크와 병합되기 전에 연구한 결과 캘리포니아 희귀 식물 순위를 가진 두 종류의 식물이 발견되었습니다: Juncus acutus leopoldii와 Iva hayesiana.[8]: 11–12

2015년 Chollas Creek 어귀에서 연구한 결과 4종의 쌍각류와 1종의 복족류가 발견되었습니다.가장 많은 쌍각류는 [24]: 9 키오네의 한 종이었습니다.

Chollas Creek을 따라 흔히 발견되는 새들은 캘리포니아 그나트캐처, 붉은 꼬리 매, 벨의 비레오, 그리고 선인장 [25]렌을 포함합니다.이 종들 중에서 해안가 캘리포니아 그나트캐처는 위협을 받고 있는 [9]: 22 [26]종입니다.

이 개울 주변에 사는 야생동물은 코요테, 스컹크, 주머니쥐, 그리고 빨간 어깨 [27]: 26–27, 35 매를 포함할 수 있습니다.이 개울 주변에서 발견될 수 있는 다른 야생동물로는 사막 솜꼬리, 회색여우,[25] 큰 갈색박쥐 등이 있습니다.

역사

Chollas Creek의 존재는 적어도 기원전 1500년까지 거슬러 올라가는 것으로 추정되며,[10]: 9 늦어도 서기 0년까지는 습지 환경이 강 어귀를 지배합니다.늦어도 서기 1000년쯤에는 [10]: 10 개울의 북서쪽 입구에 모래사장이 형성되었습니다.

아메리카 원주민 역사

촐라스 크릭은 스페인 [11]: 43 [28]사람들이 오기 전에 쿠메야이족에 의해 사용되었습니다.

촐라스 아메리카 원주민 공동체

Kumiai에서 Chollas Creek에 있는 마을은 Matt Xtaat이라고 [1][2]이름 지어졌습니다.이 마을은 1782년 라 프린세사의 항해사 돈 후안 판토자이 아리오라가 만든 지도에 "란체리아 데 라 초야스"[10]: 34–35 [29]라는 이름이 붙어 있습니다.1841년까지, 외젠 뒤플로트 드 모프라스는 마을이 [10]: 35 더 이상 존재하지 않는다고 언급했습니다.2004년과 2006년에 실시된 고고학 조사에 따르면, 마을은 현재 북쪽의 오션뷰 대로와 남쪽의 내셔널 애비뉴 사이에 위치해 있으며, 서쪽의 31번가와 [10]: 45–48 동쪽의 35번가 사이에 위치해 있습니다.2011년에 수행된 고고학 연구에 따르면, 마을이 위치한 지역은 2011년 이전에 2천년 이상 시작되었고,[10]: 147 빠르면 2011년 이전에 1,771년 이전에 시작되었습니다.마을이 차지하던 땅은 지금은 단독주택과 아파트가 [10]: 53 차지하고 있습니다.

스페인 시대

San Antonio의 선원들에 의해 실시된 조사인 Portola Expedition 동안 Chollas Creek가 실행 가능한 수원지라는 것을 발견했습니다.이러한 발견에도 불구하고 [30]쿠메야이 공동체의 존재로 인해 활용되지 못했습니다.1769년, 주니퍼 세라(Juniper Serra)는 촐라스 크리크(Chollas Creek)의 마을에 촐라스 [10]: 33 선인장이 줄을 잇고 있다고 언급했습니다.다른 쿠메야이 공동체들이 1775년 11월 샌디에고 미션에 대한 공격에 참여했지만 초야스는 [11]: 43 참여하지 않았습니다.18세기 후반 초야 출신 71명이 [11]: 43 세례를 받았습니다.

미국 시대

19세기

무대 코치는 지금의 연방 [31]: H-43 [32][33]대로를 따라 내려가는 촐라스 크릭 분수령 안에서 이동했습니다.1851년 육군 장교 나다니엘 리옹은 개울을 따라 동쪽으로 이동하여 지금의 캘리포니아주 [28]캄포로 가는 길을 마련했습니다.1883-1884년 장마철에 남부 캘리포니아는 기록적인 강우량을 기록했습니다.2023년 2월[update] 현재 샌디에이고 [34]카운티에서 가장 비가 많이 오는 계절입니다.그 기간 동안, 강우로 인해 개울이 [10]: 40 [35]한때 120피트 너비로 확장되었습니다.1886년 내셔널 시티와 오테이 철도는 스위트워터 [10]: 40 댐 건설에 사용된 철도 선로를 위해 현재의 메인 스트리트 정렬 근처에 개울 위에 건널목을 건설했습니다.1887년 캘리포니아 남부 철도가 소유한 철도 선로가 개울 [10]: 39 위를 건넜습니다.1888년, 코로나도 철도가 소유한 철도 선로가 오늘날 내셔널 [10]: 40 애비뉴의 선형 근처의 개울을 건넜습니다.

20세기

1901년,[13] Chollas Reserve는 강의 지류에 만들어졌습니다. Chollas Heights Dam이라고도 알려진 Chollas Dam의 건설로 인해 만들어졌습니다. Chollas Heights Dam은 강철로 된 코어 [36]판을 가진 56피트(17미터) 높이의 흙을 채우는 형태의 댐입니다.저수지가 건설되었을 때, 샌디에고 시 경계의 동쪽에 있었고, 로어 오테이 [37]: 20 저수지에서 나오는 수도관의 종점이었습니다.Southern California Mountain Water Company가 지었으며,[37]: Appendix B, page 15 1913년에 City of San Diego가 나머지 회사를 인수했습니다.Chollas 저수지의 물은 University Heights [38]저수지로 배관되어 내려갔습니다.1917년 한 기간 동안, 폭풍에 의해 샌디에이고에 공급된 물 분배 시스템의 나머지 부분이 손상되었기 때문에, 촐라스 저수지는 [37]: Appendix B, page 23 샌디에이고의 유일한 물 공급원이 되었습니다.1927년에 댐에 균열이 생겨 [37]: Appendix B, page 23 수리가 필요했습니다.세인트루이스의 붕괴 이후. 프란시스 댐은 촐라스 [37]: 26 저수지의 용량 확장을 포함하여, 이 댐들에 대한 수정과 개선을 가져온 다른 댐들에 대한 재평가로 이어졌습니다.그곳에는 수처리 공장이 있었지만 [39]1950년에 해체되었습니다. 이것은 [40]머레이 호수에 지어진 훨씬 더 큰 수처리 공장의 완공 때문이었습니다.1966년에 이 저수지는 해체되어 샌디에이고 시 공원 및 레크리에이션 부서로 옮겨졌고 촐라스 호수 [37]: Appendix B, page 19 [41][42]공원이 되었습니다.1971년에는 15세 [42]이하 청소년을 위한 낚시 호수로 지정되었습니다.촐라스 호수는 대략 16에이커입니다.[43]1986년, 박트로세라도살리스 한 마리가 호수 근처의 덫에 걸려 [44]이 지역에서 이 종들을 퇴치하려는 노력으로 이어졌습니다.

Chollas Heights Navy Radio Station은 [14]1916년에 Chollas Reserve 바로 북쪽에 지어졌습니다.Point Loma에서 원격으로 작동하며, 제작 당시 가장 큰 진공관을 사용했으며,[45] 냉각 상태를 유지하기 위해 분당 50US 갤런(190L)이 필요했습니다.그 장소는 호수의 물이 가열된 송신관을 [46][47]: 12 식힐 수 있도록 선택되었습니다.1915년 2월에서 1916년 [48][49]1월 26일 사이에 각각 660피트(200미터) 높이의 세 개의 탑이 세워졌습니다.그것은 20만 와트의 속도로 방송되는 세계 최초의 세계적인 해군 무선 송신 시설이었고,[47]: 2, 8 [48] 그 당시 북미에서 가장 강력한 무선 송신기였습니다.그것은 펄 하버, 캐비테,[50] 아나폴리스에 있는 위치들을 포함하여, 일련의 강력한 라디오 방송국들 중 하나로 지어졌습니다.미국이 대전에 참전한 것을 시작으로 제5해병연대 해병대 중대가 촐라스 하이츠에 주둔했고, 라디오 [51]방송국의 보안을 강화하기 위해 추가적인 변경이 이루어졌습니다.해병대는 [51]1921년에 라디오 방송국을 떠났습니다.그 시설을 역사적인 [52]랜드마크로 등재하기 위해 노력했습니다.시설의 일부 구조물은 다른 용도로 재사용되고 있지만, 가장 역사적인 부분은 [53]저장되지 않았습니다.이 역은 1992년에 폐쇄되었다가 [48]1994년에 철거되었습니다.라디오 [54][55]방송국 자리에 군용 주택이 들어섰습니다.멸종위기종인 브랜치넥타 산디에고넨시스(Branchinecta sandiegonensis)가 촐라스 하이츠([56]Chollas Heights)의 군용 주택에서 발견된 것으로 기록되었습니다.

세기의 전환기부터 적어도 1930년까지, 최소 2,000피트(610m)에 이르는 개울 입구에 하구가 존재했고, 개울의 남북 가지가 [10]: 11–12 만나는 지점까지 확장되었습니다.1919년, 샌디에고 해군기지가 세워졌습니다.곧이어 천라스천 어귀의 땅이 메워지면서 기존 습지가 사라졌습니다.그 개울은 해군 [10]: 40 기지의 일부인 간척지의 범람을 막기 위해 수로 안에 놓였습니다.1946년부터 1981년까지 샌디에고 시는 Chollas [57][58]저수지 근처의 Chollas Creek 유역 내에서 화상 장소와 매립지를 운영했습니다.1951년 새해 전날, 그 개울은 십여 [12]가구에 영향을 미쳤습니다.1960년대 초에 홍수 [10]: 42 방지를 목적으로 하천의 수로가 추가적으로 발생했습니다.1969년, Chollas Creek에서 홍수가 발생하여 Oceanview Boulevard 근처에 있는 개울의 수로 부분이 붕괴되고 Jackie Robinson YMCA가 [59]손상되었습니다.1978년에는 하구에서 0.35마일(0.56km)까지의 하천 일부가 항해 가능한 [4]해역으로 지정되었습니다.1999년, Chollas Creek는 San Diego Region의 지역 수질 관리 위원회에 의해 손상된 수체 목록에 추가되었는데,[60] 이는 빗물 표본에서 유기인산 살충제와 중금속이 발견된 이후였습니다.

21세기

2002년 샌디에고 시는 이 [18]개울을 복원하기 위해 20년간 4천2백만 달러의 계획을 채택했습니다.같은 해, 이 개울의 유역은 샌디에고 [61]카운티의 어떤 유역보다도 인구 밀도가 높았습니다.2007년,[15] 상당한 불법 투기로 인해 Chollas Creek를 정화하기 위해 Groundworks가 형성되었습니다.2013년까지, 대부분의 개울이 콘크리트 수로나 지하 암거 안에 놓였지만, 개울 바닥의 작은 부분은 [31]: H-10 개울의 남쪽 가지에 있는 더 자연스러운 부드러운 수로로 복구되었습니다.2014년, 이웃 주민들은 공동체의 이용을 위해 유역 지역의 공터를 개간하기 위해 조직하였습니다.샌디에고 시민 혁신 연구소와 그라운드워크 샌디에고와 함께 일하는 인근 단체가 땅을 치웠습니다.개선사항으로는 "걷는 길, 자생 식물 조경, 모자이크 아트 벤치 및 그늘 구조"[62]가 포함되었습니다.2015년에 잡힌 물고기 4마리 중 1마리와 어귀 Chollas [63]Creek의 퇴적물에서 미세 플라스틱이 발견되었습니다.2016년 1월, Friends of Chollas Creek는 오크 파크 [64]근처에 있는 개울을 청소하는 일을 조직했습니다.2021년 6월 샌디에이고 시는 촐라스 크릭을 지역 공원으로 조성하겠다고 선언했습니다.개울의 크기와 무질서한 확장 때문에, Chollas Creek Regional Park은 작은 공원, 개방된 협곡, 산책로 및 기타 휴양 시설의 [19]느슨한 집합체가 될 것이라고 결정되었습니다.이는 2021년 8월 공원기본계획에서 [65]확정되었습니다.이 이전에, Chollas Creek는 [19]샌디에고에서 지역 공원으로 지정되지 않은 유일한 주요 수로였습니다.2022년 말, 캘리포니아 해안 위원회는 1907년으로 거슬러 올라가는 라스 촐라스 크릭 다리의 수리를 승인했고,[66] 샌디에고 트롤리는 크릭을 건널 때 사용합니다.

2022년 1월 캘리포니아 주 94번 국도에서 캘리포니아 바다 사자가 발견되었는데, 당시 캘리포니아 고속도로 순찰대였던 행인 운전자들은 [67]시월드 샌디에고 직원이 평가를 위해 가져갈 때까지 교통을 우회해야 했습니다.그 당시의 이론들 중 하나는 그가 샌디에고 만에서 촐라스 크릭 위로 3.5 [67]마일의 경로인 94번 고속도로까지 여행했다는 것이었습니다.이 특별한 바다사자가 처음으로 씨월드 직원의 도움을 필요로 한 것은 2021년 11월 샌디에고 국제 [68][69]공항 근처의 하버 아일랜드 드라이브로 물에서 떨어져 나갔을 때였습니다.2022년 2월, 오리발 인식표 부착과 재활을 [70]거쳐 바다에 풀어졌습니다.2022년 4월, 프리웨이(Freeway)라는 이름을 받은 바다사자는 바닷물에서 1마일 이상 떨어진 로건 하이츠(Logan Heights) 지역의 촐라스 크릭(Chollas Creek)을 올라가 같은 [68][71]해 1월 발견된 곳을 향해 이동 중이었습니다.Chollas Creek에서 구조된 후, 바다 사자는 SeaWorld에 [71]보존되었습니다.2023년 4월 진행성 [69][72]질환으로 건강이 악화된 바다사자는 씨월드에서 안락사 되었습니다.

2023년 5월, 그라운드워크 샌디에이고는 샌디에이고 시의회에 촐라스 크릭을 [73]따라 일련의 산책로를 조성하는 계획을 제시했습니다.촐라스 크릭 지역 공원은 2024년에 [74]완공될 것으로 예상됩니다.

낚시

캘리포니아 어류 및 야생동물국은 Chollas Creek의 지류에 위치한 Chollas Park Lake에서 물고기의 사육을 추적합니다.

참고문헌

- ^ a b c Miskwish, Michael (September 2021). "The Kumeyaay Villages of San Diego City" (PDF). Indian Voices. San Diego, California: Blackrose Communications. Retrieved June 26, 2023.

- ^ a b Felix-Ibarra, Ana Patricia (2021-08-17). "Kumeyaay Placenames". ArcGIS StoryMaps. Archived from the original on 2021-12-28. Retrieved 2021-12-28.

- ^ Pardy, Linda; Smith, Jimmy; Jayne, Deborah (14 August 2002). Technical Report for Total Maximum Daily Load for Diazinon in Chollas Creek Watershed San Diego County (PDF) (Report). California Regional Water Quality Control Board San Diego Region. p. 4. Chollas Creek Diazinon TMDL Final Technical Report. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 May 2023. Retrieved 29 August 2023.

- ^ a b c Matthew, R.S. (1978), Navigable Waters of the United States; Las Chollas Creek (PDF), United States Army Corps of Engineers, archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-01-21, retrieved 25 August 2023

- ^ "Roam Chollas Creek Threading City Heights Encanto". San Diego Reader. 17 July 2019. Archived from the original on 10 June 2023. Retrieved 3 July 2023.

- ^ a b Comment Summary and Responses (PDF) (Report). October 18, 2017. p. 9. Amendment to the Water Quality Control Plan for the San Diego Basin to Incorporate Site-Specific Water Effect Ratios into Total Maximum Daily Loads for Dissolved Copper and Dissolved Zinc in Chollas Creek. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 August 2023. Retrieved 3 August 2023.

Chollas Creek's cumulative length is 30 linear miles (two major forks) and the watershed is 25 square miles in area.

- ^ a b c d Preliminary Evaluation of an Illegal Dumping Abatement (PDF) (Report). City of San Diego. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 August 2023. Retrieved 31 July 2023.

- ^ a b MacGregor, Catherine (June 2015). Chollas Creek to Bayshore Bikeway Multi-Use Path: Biological Technical Report (PDF) (Report). Groundwork San Diego - Chollas Creek. R.E.C. Consultants, Inc. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 February 2017. Retrieved 7 August 2023 – via City of San Diego.

- ^ a b c Chollas Creek Enhancement Program (PDF) (Report). City of San Diego. 14 May 2002. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 March 2023. Retrieved 7 August 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Brodie, Natalie; Hall, Jacqueline; Sampson, Michael; Buxton, Michael; Morgan, Christopher; Miller, Jason; Roeder, Mark; Homburg, Jeffrey; Windingstad, Jason; sasson, Aharon (October 2014). McLean, Roderic (ed.). Late Holocene Life Along Chollas Creek: Results of Data Recovery at CA_SDI-17203 (Report). Carrie Purcell. LSA Associates, Inc. Retrieved 3 July 2023 – via Research Gate.

- ^ a b c d Center City Project Environmental Impact Report/ Environmental Impact Statement. San Diego: WESTEC Services, Inc. January 20, 1976. Archived from the original on 25 April 2023. Retrieved 24 April 2023.

- ^ a b "Damage Heavy in S.D. Storm; Runoff Raises Level of Lakes". Evening Tribune. San Diego. December 31, 1951. Archived from the original on 2023-08-28. Retrieved 28 August 2023 – via San Diego Union-Tribune.

- ^ a b HELIX Environmental Planning, Inc.; McCausland, Annie (October 2022). City of San Diego Dam Maintenance Program (PDF) (Report). City of San Diego Public Utilities Department. p. 20. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 April 2023. Retrieved 24 April 2023.

- ^ a b Fetzer, Leland (2005). San Diego County Place Names, A to Z. Sunbelt Publications, Inc. ISBN 978-0-932653-73-4. Archived from the original on 2023-09-11. Retrieved 2023-09-11.

- ^ a b c Florido, Adrian (22 October 2010). "Cleaning Up Chollas Creek's Trash". Voice of San Diego. San Diego. Archived from the original on 30 August 2023. Retrieved 30 August 2023.

- ^ OEHHA California Office of Environmental Heal Hazard Assessment. "Impaired Water Bodies". OEHHA. Archived from the original on 27 June 2023. Retrieved 26 June 2023.

- ^ a b "An Ordinance of the Council of the City of San Diego Designating Chollas Creek Watershed as a San Diego Regional Park Pursuant to San Diego Charter Section 55.2(a)(9)". Ordinance No. O-21372 of 27 September 2021 (PDF). Council of the City of San Diego.

- ^ a b "Chollas Creek supporters get residents into the flow". San Diego Union-Tribune. San Diego. 30 September 2010. Archived from the original on 29 August 2023. Retrieved 28 August 2023.

- ^ a b c Garrick, David (27 June 2021). "San Diego to create regional park in long-neglected Chollas Creek area". San Diego Union-Tribune. San Diego. Archived from the original on 29 August 2023. Retrieved 29 August 2023 – via American Society of Landscape Architects.

Mae, Melissa; Bowler, Matthew (2 June 2021). "Mayor Gloria Begins 'Parks For All Of Us' Initiative, Calling For Equity". KPBS. San Diego. City News Service. Archived from the original on 29 August 2023. Retrieved 29 August 2023.

"San Diego to create regional park in long-neglected Chollas Creek area of southeastern San Diego". San Diego Union-Tribune. San Diego. 27 June 2021. Archived from the original on 5 June 2023. Retrieved 29 August 2023. - ^ Tetra Tech (24 July 2023). Chollas Watershed Comprehensive Load Reduction Plan - Phase II (PDF) (Report). City of San Diego. p. 29. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 January 2022. Retrieved 29 August 2023.

- ^ California State Water Resources Control Board (2007-06-13). San Diego Regional Board Meeting (Report). Archived from the original on 2023-08-29. Retrieved 2023-08-28.

- ^ Appendix 7-B: Integrated Flood Management Planning Study (PDF) (Report). San Diego Integrated Regional Water Management. April 2013. p. 4-14 - 4-15. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 October 2022. Retrieved 28 August 2023.

- ^ Roy E. Pettus (1979). A Cultural Resources Survey of Portions of the Las Chollas, South Las Chollas, Los Coches, Forester and Loma Alta Stream Basins in San Diego County, California (Report). Department of the Army, Corps of Engineers. Archived from the original on June 27, 2023. Retrieved June 26, 2023.

- ^ Smith, David M.; Maxon, Patrick O. (August 2015). Phase II Evaluation of a Portion of Archaeological Site CA-SDI-12093 (PDF) (Report). Lara Gates. BonTerra Psomas. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 February 2017. Retrieved 31 July 2023 – via City of San Diego.

- ^ a b Schulte, Richard (2021-04-27). "Nature and art at Chollas Creekside Park". Cool San Diego Sights!. Archived from the original on 2023-08-01. Retrieved 2023-08-01.

- ^ Bailey, Eric A.; Mock, Patrick J. (1998). "Dispersal Capability of the California Gnatcatcher: A Landscape Analysis of Distribution Data" (PDF). Western Birds. 29 (4): 351–360. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 August 2023. Retrieved 30 August 2023.

"PHASE I - SOUTH BRANCH Existing Creek Conditions" (PDF). Chollas Creek South Branch: Implementation Program (PDF) (Report). City of San Diego. p. 15. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 April 2022. Retrieved 6 September 2023.One site of the federal threatened coastal California gnatcatcher (Polioptila Califronica californica) is known from a large patch of coastal sage scrub between Roswell and Market streets along the Encanto Branch, approximately 1,500 feet (460 m) to the east of Chollas Creek.

- ^ Trestles Environmental Corporation; Schaefer Environmental Solutions (May 2021). Biological Resources Technical Report (PDF) (Report). Groundwork San Diego. City of San Diego. Federal Boulevard Creek De-Channelization and Trail Project. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 August 2023. Retrieved 25 August 2023.

- ^ a b "Lemon Grove Timeline". Lemon Grove Historical Society. Archived from the original on June 27, 2023. Retrieved June 26, 2023.

- ^ Fetzer, Leland (2005). San Diego County Place Names A to Z (1st ed.). San Diego, California: Sunbelt Publications, Inc. pp. 23–24. ISBN 9780932653734.

- ^ Moilner, Geoffrey (Spring 2016). "Cosoy: Birthplace of New California". Journal of San Diego History. 62 (2): 131–158. Archived from the original on 18 July 2020. Retrieved 24 April 2023.

- ^ a b Appendix H: Environmental Analysis and Checklist (PDF) (Report). California Regional Water Quality Control Board, San Diego Region. 19 June 2013. Toxic Pollutants in Sediment TMDLs Mouths of Paleta, Chollas, and Switzer Creeks Environmental Analysis and Checklist. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 July 2022. Retrieved 28 August 2023.

- ^ "Stage Once Crossed Otay, Janal". The San Diego Union. July 28, 1968. p. G2. OCLC 13155544.

- ^ Krueger, Anne (January 16, 2010). "Route to Backcountry Seen as Path to History". San Diego Union-Tribune. p. NC2. OCLC 25257675. Archived from the original on August 31, 2023. Retrieved August 31, 2023.

- ^ A History of Significant Weather Events in Southern California (PDF) (Report). National Weather Service. February 2023. p. 5. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 May 2023. Retrieved 3 July 2023.

- ^ Pourade, Richard F. (1997). "CHAPTER ELEVEN: THE TRAIN THAT FINALLY CAME". THE GLORY YEARS, 1865-1899. Copley Press. Archived from the original on 2023-07-08. Retrieved 2023-08-29.

- ^ Reports on the Works of the Southern California Mountain Water Company (PDF) (Report). 1911. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-08-29 – via University of California, San Diego Library.

- ^ a b c d e f McClausland, Annie (October 2022). City of San Diego Dam Maintenance Program (PDF) (Report). Helix Environmental Planning Inc. City of San Diego. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 August 2023. Retrieved 28 August 2023.

- ^ Black, S.T.; Smythe, W.E. (1913). San Diego and Imperial Counties, California: A Record of Settlement, Organization, Progress and Achievement. S.J. Clarke Publishing Company. p. 311. Archived from the original on 28 August 2023. Retrieved 28 August 2023.

- ^ Martin, J. (2017). The Dams of Western San Diego County. Images of America. Arcadia Publishing Incorporated. p. 40. ISBN 978-1-4396-6340-0. Archived from the original on 28 August 2023. Retrieved 28 August 2023.

- ^ North Park Historical Society; Stanco, Kelley (9 April 2015). RHB-15-023 (PDF) (Report). City of San Diego. p. Section 8 page 16. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 March 2022. Retrieved 28 August 2023.

- ^ Horn, Allison (13 May 2023). "San Diego Fire-Rescue crews remove body from Chollas Lake". KGTV-TV. San Diego. Archived from the original on 28 August 2023. Retrieved 28 August 2023.

Chollas Lake, which served as a reservoir from 1901 to 1966, is open during daylight hours for recreation.

- ^ a b Open Space Division (10 January 2021). 2020 MSCP Management Report (Report). City of San Diego. p. Chollas Lake Ranger District. Archived from the original on 28 August 2023. Retrieved 28 August 2023.

- ^ "Chollas Creek Dissolved Metals Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) Implementation Plan" (PDF). City of San Diego. July 2009. p. 8. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 29, 2023. Retrieved August 28, 2023.

- ^ "East County : Spraying to Begin in Fruit-Fly Fight". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles. 17 August 1986. Archived from the original on 6 September 2023. Retrieved 6 September 2023.

- ^ Michels, J. (1926). "Science News". Science. American Association for the Advancement of Science. pp. x–xii. Archived from the original on 7 August 2023. Retrieved 7 August 2023.

- ^ Schutle, Richard (26 October 2021). "Monument to tallest structures ever built in San Diego". Cool San Diego Sights!. Gravatar. Archived from the original on 29 August 2023. Retrieved 29 August 2023.

- ^ a b Crawford, Kathleen (December 1994). Photographs Written Historical and Descriptive Data (PDF) (Report). National Park Service. Historic American Engineering Record. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 July 2022. Retrieved 7 August 2023 – via Library of Congress.

- ^ a b c "Navy Radio Transmitter Facility (NAVRADTRANSFAC) Chollas Heights". www.globalsecurity.org. Archived from the original on 2023-08-01. Retrieved 2023-08-01.

- ^ Bennett W6VMX, Joe (February 2012). "Mystery of the Masthead for January" (PDF). Counterpoise. 22 (2): 2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 August 2023. Retrieved 7 August 2023.

- ^ Gebhard, Louis A. (1979). Evolution of Naval Radio-Electronics and Contributions of the Naval Research Laboratory (PDF) (Report). Naval Research Laboratory. p. 9. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 August 2023. Retrieved 7 August 2023.

- ^ a b "Chollas Heights (San Diego) Naval Radio Station". Naval History and Heritage Command. United States Navy. Retrieved 11 September 2023.

- ^ Broms, Bob (August 1994). "Chollas Heights Update" (PDF). Refletions. San Diego: Save Our Heritage Organization. 25 (3): 1. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 July 2023. Retrieved 7 August 2023.

- ^ O’Leary, B.L.; Capelotti, P.J. (2014). Archaeology and Heritage of the Human Movement into Space. Space and Society. Springer International Publishing. pp. 100–101. ISBN 978-3-319-07866-3. Archived from the original on 7 August 2023. Retrieved 7 August 2023.

- ^ R. Christopher Goodwing and Associates, Inc. (August 1995). "Naval Radio Transmitter Facility Chollas Heights". National Historic Context for Department of Defense Installations, 1790-1940 (PDF) (Report). United States Army Corps of Engineers. pp. 267–271. Retrieved 11 September 2023 – via National Park Service.

- ^ England, Nick. "Naval Radio Transmitting Facility (NRTF) Chollas Heights NPL". Navy-radio.com. Retrieved 11 September 2023.

- ^ Fish and Wildlife Service (3 February 1997). Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Determination of Endangered Status for the San Diego Fairy Shrimp (Report). Government Publishing Office. p. 4925-4939. Federal Registrar Volume 62, Number 22.

"San Diego fairy shrimp". San Diego Management and Monitoring Program. San Diego Association of Governments. 2010. Retrieved 11 September 2023.

Fish and Wildlife Service (11 January 2008). Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Designation of Critical Habitat for the San Diego Fairy Shrimp (Branchinecta sandiegonensis) (Report). Federal Registrar. pp. 70648–70714. 07-5972. Retrieved 11 September 2023.

Bauder, Ellen; Kreager, D Ann; McMillan, Scott C. (September 1998). Vernal Pools of Southern California (PDF) (Report). Region 1 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Services. pp. 46, E4. Retrieved 11 September 2023 – via County of San Diego. - ^ Pinz, Bill; Young, Glenn; Abramson-Beck, Beth. South Chollas LF - Water Admin Bldg Post Closure Land-Use Development Project (PDF). 18th Technical Training Series. Monterey, California – via California State University, Sacramento.

- ^ Gero, Nicholas; Hartman, Curtis; Knotts, Janet; Leinska, Vassilena; Lindquist, Blake; Lopez, Priscilla; Neufield, Darin; Nguyen, James; Nguyen, Toni; O'Conner, Kevin; Wood, Lisa. A History of Waste Management in the City of San Diego (PDF) (Report). City of San Diego. pp. 23–24. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 12, 2023. Retrieved June 26, 2023.

- ^ Flood Insurance Study (PDF) (Report). Federal Emergency Management Agency. p. 36. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 May 2023. Retrieved 28 August 2023 – via County of San Diego.

- ^ Southern California Coastal Water Research Project (10 November 1999). Characterization of Stormwater Toxicity in Chollas Creek, San Diego (PDF) (Report). Regional Water Quality Control Board. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 August 2023. Retrieved 25 August 2023.

- ^ Wilen, Cheryl A. (2 September 2002). Survey of Residential Pesticide Use in the Chollas Creek Area of San Diego County and Delhi Channel of Orange County, California (PDF) (Report). California Department of Pesticide Regulation. p. 5. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 September 2023. Retrieved 6 September 2023.

The population of the watershed makes it the county's most densely populated watershed with approximately 8,000 residents per square mile.

- ^ "From vacant lot to farmers market". livewellsd.org. November 4, 2014. Archived from the original on April 25, 2023. Retrieved April 24, 2023.

"Civic Innovation Lab pioneering neighborhood upgrades". San Diego Union-Tribune. 14 March 2014. Archived from the original on 29 August 2023. Retrieved 29 August 2023.

Kolson Hurley, Amanda; Ohstrom, Katrina (23 February 2015). "One Mayor's Downfall Killed the Design Project That Could've Changed Everything". Next City. Archived from the original on 29 August 2023. Retrieved 29 August 2023. - ^ Theresa, Talley; Nina, Venuti; Rachel, Whelan (June 2015). Plastics in sediments and fishes at the mouth of Chollas Creek, San Diego, USA (Report). Sea Scientific Open Data Publication. doi:10.17882/72119. Archived from the original on 25 August 2023. Retrieved 25 August 2023.

- ^ Santos, Robert (19 January 2016). "Volunteers work to clean up before next storm". KGTV-TV. San Diego. Archived from the original on 29 August 2023. Retrieved 28 August 2023.

- ^ Branch, Katheleen; Galvez, Oscar; Klien, Michael; Gilson, Robin (2021). Park Master Plan: Adopted August 2021 (PDF) (Report). City of San Diego. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 June 2023. Retrieved 3 August 2023.

- ^ W8b (PDF) (Report). California Coastal Commission. 7 September 2022. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 October 2022. Retrieved 28 August 2023.

Agenda Meeting of the San Diego Metropolitan Transit System Board of Directors (PDF) (Report). Metropolitan Transit System. 29 July 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 August 2023. Retrieved 28 August 2023. - ^ a b Chen, Michael; Saunders, Mark (7 January 2022). "Sea lion on San Diego freeway guided to safety by good Samaritans". KGTV-TV. San Diego: Scripps Media, Inc. Archived from the original on 25 August 2023. Retrieved 25 August 2023.

Hollan, Michael (8 January 2022). "SeaWorld staffers rescue sea lion hanging out on San Diego highway". New York Post. New York City. Fox News. Archived from the original on 25 August 2023. Retrieved 25 August 2023. - ^ a b Figueroa, Teri (17 May 2022). "Wayward sea lion is back—this time found in a San Diego storm drain". Phys.org. Isle of Man. San Diego Union-Tribune. Archived from the original on 25 August 2023. Retrieved 25 August 2023.

- ^ a b Walker, Shaunda (22 April 2023). "San Diego's well known sea lion "Freeway" dies". KFMB-TV. San Diego. Archived from the original on 25 August 2023. Retrieved 25 August 2023.

Chavez, Paloma (24 April 2023). "Sea lion who was rescued from highway is euthanized at SeaWorld. 'Adventurous spirit'". The Sacramento Bee. Sacramento. Archived from the original on 26 April 2023. Retrieved 25 August 2023. - ^ Romaine, Jenna (10 February 2022). "Sea lion rescued from San Diego highway rehabilitated, released". The Hill. Washington, D.C. Archived from the original on 25 August 2023. Retrieved 25 August 2023.

Harper, Ben (10 February 2022). "Sea lion found wandering California highway returned to the ocean". UPI. Archived from the original on 28 March 2022. Retrieved 25 August 2023. - ^ a b Feather, Bill; Romero, Dennis (16 May 2022). "Wayward sea lion named Freeway is once again found exploring urban San Diego". NBC News. Archived from the original on 25 August 2023. Retrieved 25 August 2023.

- ^ "SeaWorld euthanizes sick sea lion found on San Diego freeway". KSBY. San Luis Obispo. Associated Press. 21 April 2023. Archived from the original on 25 August 2023. Retrieved 25 August 2023.

Sklar, Debbie L. (22 April 2023). "Rescued Sea Lion 'Freeway' Euthanized by SeaWorld San Diego Due to Disease". Times of San Diego. San Diego. Archived from the original on 25 August 2023. Retrieved 25 August 2023. - ^ Aarons, Jared (5 May 2023). "Southeast San Diego communities push for connected trail along Chollas Creek". KGTV-TV. San Diego. Archived from the original on 29 August 2023. Retrieved 28 August 2023.

- ^ Crea, Jackie (16 November 2022). "Future Chollas Creek Project Part of Bigger Plan to Transform Communities Along Watershed". KNSD. San Diego. Archived from the original on 29 August 2023. Retrieved 28 August 2023.

Styles, Shawn (28 June 2021). "5 Branches of Chollas Creek to become regional park". KNSD. San Diego. Archived from the original on 29 August 2023. Retrieved 28 August 2023. - ^ "CDFW Fishing Guide Map Viewer". California Department of Fish and Wildlife Fishing Guide. California Department of Fish and Wildlife. Archived from the original on August 29, 2023. Retrieved August 28, 2023.

- ^ Powell, Daniel (26 December 2017). "Chollas Lake piers and playground make it easy". San Diego Reader. San Diego. Archived from the original on 6 September 2023. Retrieved 6 September 2023.

Robertson, Cynthia (17 February 2016). "Chollas Lake, a hidden treasure around Lemon Grove area". The Californian. El Cajon, California. Archived from the original on 6 September 2023. Retrieved 6 September 2023.

Dolan, Steve (26 July 1985). "San Diego Fishing Holes". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles. Archived from the original on 6 September 2023. Retrieved 6 September 2023.

Landers, Rich (November 1997). "Trout Lure California Kids". Field & Stream. p. 83. ISSN 8755-8599. Archived from the original on 6 September 2023. Retrieved 6 September 2023.

추가열람

- Las Cholla Creek San Diego County California. United States Army Corps of Engineers. 1968.