Intertemporal choice

Intertemporal choice is the process by which people make decisions about what and how much to do at various points in time, when choices at one time influence the possibilities available at other points in time. These choices are influenced by the relative value people assign to two or more payoffs at different points in time. Most choices require decision-makers to trade off costs and benefits at different points in time. These decisions may be about saving, work effort, education, nutrition, exercise, health care and so forth. Greater preference for immediate smaller rewards has been associated with many negative outcomes ranging from lower salary[1] to drug addiction.[2]

Since early in the twentieth century, economists have analyzed intertemporal decisions using the discounted utility model, which assumes that people evaluate the pleasures and pains resulting from a decision in much the same way that financial markets evaluate losses and gains, exponentially 'discounting' the value of outcomes according to how delayed they are in time. Discounted utility has been used to describe how people actually make intertemporal choices and it has been used as a tool for public policy. Policy decisions about how much to spend on research and development, health and education all depend on the discount rate used to analyze the decision.[3]

Portfolio allocation

Intertemporal portfolio choice is the allocation of funds to various assets repeatedly over time, with the amount of investable funds at any future time depending on the portfolio returns at any prior time. Thus the future decisions may depend on the results of current decisions. In general this dependence on prior decisions implies that current decisions must take into account their probabilistic effect on future portfolio constraints. There are some exceptions to this, however: with a logarithmic utility function, or with a HARA utility function and serial independence of returns, it is optimal to act with (rational) myopia, ignoring the effects of current decisions on the future decisions.

소비

케인즈 소비 함수는 두 가지 주요 가설에 기초했다. 첫째로, 한계소비성향은 0과 1사이에 있다. 둘째, 평균 소비성향은 소득이 증가함에 따라 떨어진다. 초기 경험적 연구는 이러한 가설들과 일치했다. 그러나 제2차 세계 대전 이후 소득이 증가해도 저축은 증가하지 않는다는 것이 관찰되었다.[citation needed] 따라서 케인즈식 모델은 소비 현상을 설명하지 못했고, 따라서 임시직간 선택 이론이 개발되었다. 기업간 선택의 분석은 1834년 존 래에 의해 '자본의 사회론'에 소개되었다. 이후 1889년 유겐 폰 뫼바웨르크, 1930년 어빙 피셔가 이 모델에 대해 상세히 설명했다. 기업간 선택에 기초한 몇 가지 다른 모델에는 프랑코 모딜리아니가 제안한 라이프사이클 가설과 밀턴 프리드먼이 제안한 영구소득 가설 등이 있다. 왈라시아 평형 개념은 또한 임시적 선택을 통합하기 위해 확장될 수 있다. 그러한 균형에 대한 왈라스식 분석은 두 가지 "새로운" 개념인 선물 가격과 현물 가격을 도입한다.

피셔의 기업간 소비 모델

어빙 피셔는 그의 저서 관심의 이론(1930년)에서 임시직간 선택 이론을 발전시켰다. 소비를 경상소득과 연관시킨 케인즈와는 달리 피셔의 모델은 앞을 내다보는 소비자들이 평생 만족을 극대화하기 위해 현재와 미래를 위해 얼마나 합리적인 소비를 선택하는지 보여줬다.

피셔에 따르면, 개인의 조급함은 그의 소득 흐름의 네 가지 특징, 즉 크기, 시간 형태, 구성, 위험성에 달려 있다. 이 외에도, 선견지명, 자기 통제, 습관, 삶에 대한 기대, 그리고 비천한 동기(또는 다른 사람들의 삶에 대한 걱정)는 시간 선호도를 결정하는 다섯 가지 개인적인 요소들이다.[4]

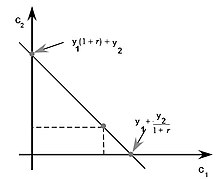

In order to understand the choice exercised by a consumer across different periods of time we take consumption in one period as a composite commodity. Suppose there is one consumer, commodities, and two periods. Preferences are given by where . Income in period is . Savings in period 1 is , spending in period is , and is the interest rate. If the person is unable to borrow against future income in the first period, then he is subject to separate budget constraints in each period:

- (1)

- Y + S ( + ). }(2)

반면에, 그러한 차입이 가능하다면, 당사자는 단일 임시 예산 제약을 받게 된다.

- (3)

왼쪽은 지출의 현재가치를 나타내고 오른쪽은 수입의 현재가치를 묘사하고 있다. 방정식에(+ 을 곱하면 그에 상응하는 미래 값을 얻게 될 것이다.

이제 소비자는 과 같이 1 }와 }}개를 선택해야 한다.

- 극대화하다

- 의 대상이 되다

A consumer may be a net saver or a net borrower. If he's initially at a level of consumption where he's neither a net borrower nor a net saver, an increase in income may make him a net saver or a net borrower depending on his preferences. An increase in current income or future income will increase current and future consumption (consumption smoothing motives).

Now, consider a scenario where the interest rates are increased. If the consumer is a net saver, he will save more in the current period due to the substitution effect and consume more in the current period due to the income effect. The net effect thus becomes ambiguous. If the consumer is a net borrower, however, he will tend to consume less in the current period due to the substitution effect and income effect thereby reducing his overall current consumption.[5]

Modigliani's life cycle income hypothesis

The life cycle hypothesis is based on the following model:

subject to

where

- U(Ct) is satisfaction received from consumption in time period t,

- Ct is the level of consumption at time t,

- Yt is income at time t,

- δ is the rate of time preference ( a measure of individual preference between present and future activity),

- W0 is the initial level of income producing assets.

Typically, a person's MPC (marginal propensity to consume) is relatively high during young adulthood, decreases during the middle-age years, and increases when the person is near or in retirement. The Life Cycle Hypothesis(LCH) model defines individual behavior as an attempt to smooth out consumption patterns over one's lifetime somewhat independent of current levels of income. This model states that early in one's life consumption expenditure may very well exceed income as the individual may be making major purchases related to buying a new home, starting a family, and beginning a career. At this stage in life the individual will borrow from the future to support these expenditure needs. In mid-life however, these expenditure patterns begin to level off and are supported or perhaps exceeded by increases in income. At this stage the individual repays any past borrowings and begins to save for her or his retirement. Upon retirement, consumption expenditure may begin to decline however income usually declines dramatically. In this stage of life, the individual dis-saves or lives off past savings until death.[6][7]

프리드먼의 영구소득 가설

제2차 세계대전 이후, 현재의 소비가 단지 경상소득의 함수에 불과한 모델은 너무 단순하다는 것이 눈에 띄었다. 소비성향이 훨씬 낮은 한계성향에도 불구하고 장기간에 걸친 평균소비성향이 대략 일정하게 보이는 사실은 설명하지 못했다. 따라서 밀턴 프리드먼의 영구적인 수입 가설은 이 명백한 모순을 설명하려는 모델들 중 하나이다.

영구적 소득 가설에 따르면 영구적 소비인P C는P 영구적 소득에 비례한다. Y. 영구적 소득은 가능한 평균 미래 소득에 대한 주관적 개념이다. 영구적인 소비는 소비와 비슷한 개념이다.

실제 소비 C와 실제 소득 Y는 각각 이러한 영구 구성 요소와 예상치 못한 임시 구성 요소 C와T Y로T 구성된다.[8]

- CPt =β2YPt

- Ct = CPt + CTt

- Yt = YPt + YTt

노동공급

현재 얼마나 많은 노동력을 공급할 것인가에 대한 개인의 선택은 현재의 노동과 여가 사이의 절충을 포함한다. 현재 공급되는 노동력의 양은 현재의 소비기회뿐만 아니라 미래의 소비기회에도 영향을 미치고, 특히 퇴직시기와 더 이상의 노동력을 공급하지 않는 미래의 선택에도 영향을 미친다. 그러므로 현재의 노동공급 선택은 임시적인 선택이다.

노동자가 임금인상에 직면하면 대체효과, 통상소득효과, 기부효과 등 3가지가 발생한다. 임금은 여가를 소비하는 기회의 비용이기 때문에 임금은 여가의 대가라는 것을 명심하라. 대체효과 : 임금이 올라갈수록 여가가 비싸진다. 그러므로 노동자는 여가를 덜 소비하고 더 많은 노동력을 공급할 것이다. 이것과 함께, 만약 실질소득이 바뀌지 않는다면, 일하는 시간의 증가가 있을 것이다. 소득효과 : 임금이 올라갈수록 여가가 비싸진다. 따라서 각 달러의 구매력은 감소할 것이다. 여가는 정상적인 상품이기 때문에 노동자는 여가를 덜 살 것이다. 이렇게 되면 근로시간과 임금률 사이에 부정적인 관계가 형성될 것이다. 기부 효과:임금이 올라갈수록 기부금(=임금타임 여가+소비)의 가치가 높아진다. 따라서 소득은 고정 노동력을 증가시킬 것이다. 여가는 정상적인 상품이기 때문에 노동자는 여가를 더 많이 살 것이다.

Fixed investment

Fixed investment is the purchasing by firms of newly produced machinery, factories, and the like. The reason for such purchases is to increase the amount of output that can potentially be produced at various times in the future, so this is an intertemporal choice.

Hyperbolic discounting

The article so far has considered cases where individuals make intertemporal choices by considering the present discounted value of their consumption and income. Every period in the future is exponentially discounted with the same interest rate. A different class of economists, however, argue that individuals are often affected by what is called the temporal myopia. The consumer's typical response to uncertainty in this case is to sharply reduce the importance of the future of their decision making. This effect is called hyperbolic discounting.

Mathematically, it may be represented as follows:

where

- f(D) is the discount factor,

- D is the delay in the reward, and

- k is a parameter governing the degree of discounting.[9]

When choosing between $100 or $110 a day later, individuals may impatiently choose the immediate $100 rather than wait for tomorrow for an extra $10. Yet, when choosing between $100 in a month or $110 in a month and a day, many of these people will reverse their preferences and now patiently choose to wait the additional day for the extra $10.[10]

See also

- Decision theory

- Discount function

- Discounted utility

- Intertemporal budget constraint

- Keynes–Ramsey rule

- Temporal discounting

References

- ^ Hampton, W. (2018). "Things for Those Who Wait: Predictive Modeling Highlights Importance of Delay Discounting for Income Attainment". Frontiers in Psychology. 9 (1545): 1545. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01545. PMC 6129952. PMID 30233449.

- ^ MacKillop, J. (2011). "Delayed reward discounting and addictive behavior". Psychopharmacology. 216 (3): 305–321. doi:10.1007/s00213-011-2229-0. PMC 3201846. PMID 21373791.

- ^ Berns, Gregory S.; Laibson, David; Loewenstein, George (2007). "Intertemporal choice – Toward an Integrative Framework" (PDF). Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 11 (11): 482–8. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2007.08.011. PMID 17980645. S2CID 22282339. Archived from the original on 2016-05-30.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- ^ Thaler, Richard H. (1997). "Irving Fisher: Modern Behavioral Economist" (PDF). The American Economic Review. 87 (2): 439–441. JSTOR 2950963. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- ^ Varian, Hal (2006). Intermediate Micro Economics.

- ^ Barro, Robert J. (1998). Macroeconomics (5th ed.). Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. ISBN 9780262024365.

- ^ Mankiw, N. Gregory (2008). Principles of Macroeconomics (5th ed.). Cengage Learning. ISBN 9780324589993.

- ^ "Adaptive expectations: Friedman's permanent income hypothesis". Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2013-08-22.

- ^ Hyperbolic discounting

- ^ P. Redden, Joseph. "Hyperbolic Discounting". Cite journal requires

journal=(help)