미국의 증오 범죄법

Hate crime laws in the United States미국의 증오 범죄법은 증오 범죄(편향 범죄라고도 한다)로부터 보호하기 위한 주 및 연방법이다.비록 주법은 다양하지만, 현행법은 인종, 종교, 민족, 국적, 성별, 성적 지향 및/또는 성 정체성에 기초하여 저질러진 증오 범죄에 대해 연방정부의 기소를 허용하고 있다.미국 법무부(DOJ), 연방수사국(FBI), 캠퍼스 경찰서는 증오 범죄 통계를 수집해 발표하도록 돼 있다.

연방

1968년 민권법 제1호

1968년 제정된 미국 시민권법 제1호 § 245(b)(2)조항 제245조 제2항은 "의도적으로 부상, 위협, 방해 또는 부상, 초기화 또는 간섭을 시도하는 자에 대해 연방정부의 기소를 허용한다.그의 인종, 색깔, 종교 또는 국가 출신 때문에 또는 희생자가 학교에 다니기, 공공 장소/지원의 후원, 취업 지원, 주 법원에서 배심원 역할을 하거나 투표와 같은 연방 보호 활동의 6가지 유형 중 하나에 참여하려고 시도했기 때문이다.[1]

이 법을 위반한 사람은 1년 이하의 벌금이나 금고 또는 두 가지 모두에 처한다.상해치사 또는 이와 같은 협박행위로 총기나 폭발물, 화재 등의 사용이 수반될 경우 개인은 10년 이하의 징역형을 받을 수 있으며, 납치, 성폭행, 살인 등의 범죄는 무기징역 또는 사형으로 처벌할 수 있다.[2]미국 지방법원은 형사 제재만을 규정하고 있다.1994년의 여성폭력금지법에는 미국 42조 13981항에 "성차별적, 징벌적 손해배상, 강제적, 선언적 구제, 법원이 적절하다고 간주할 수 있는 기타 구제"를 청구할 수 있는 조항이 포함되어 있다.

강력범죄단속 및 법집행법(1994)

미국 제994조 제284조 제280003호에 제정된 강력범죄통제 및 법 집행법은 미국 양형위원회가 실제 또는 인지된 인종, 색깔, 종교, 국적, 민족성 또는 성별에 근거하여 저질러지는 증오 범죄에 대한 처벌을 강화하도록 규정하고 있다.1995년에 양형위원회는 연방 범죄에만 적용되는 이 지침을 시행했다.[3]

교회 방화 방지법(1996)

S. 1980(104일):1996년 교회방화법은 1996년 6월 19일 의회에 상정되었으나, 상원위원회가 이 법안의 개선 장소를 일부 발견하여 사망하였다.그것은 공화당의 던컨 페어보가 후원했다.[4]1996년 5월 23일 하원은 H.R. 3525(104일)를 도입하였다.교회 방화 방지법.이 법은 1996년 7월 3일 의회의 양원을 통과하고 빌 클린턴 대통령이 서명했다.이 법안은 법률 번호 Pub가 되었다.L. 104-155.그것은 공화당의 헨리 하이드의 후원을 받았다.[5]이 법안은 의회조사국에 의해 다음과 같이 요약되었다: "[1996년 교회 방화 방지법]은 범법 행위나 영향을 미치는 주간 상업에 있어 종교 재산을 훼손하거나 종교 신앙의 자유로운 행사를 방해하는 것에 대해 연방 형법을 금지하고 처벌하도록 하고 있다."[5]법안의 변화 중 하나는 "인종, 색깔 또는 민족적 특성으로 인해 종교적 부동산을 보호하거나 파괴"하는 형량이 10년에서 20년으로 늘어난 것이다.또 공소시효도 현행 5년에서 범행일로부터 7년으로 바꿨다.증오범죄 통계법을 재승인한다.[6]

매튜 셰퍼드, 제임스 버드 주니어증오범죄 예방법(2009)

2009년 10월 28일 오바마 대통령은 매튜 셰퍼드, 제임스 버드 주니어에 서명했다.2010 회계연도 국방수권법에 첨부된 증오범죄예방법은 기존 미국 연방 증오범죄법을 피해자의 실제 또는 인지된 성별, 성적 지향, 성 정체성 또는 장애에 의해 동기 부여된 범죄에 적용하도록 확대 적용하고 피해자가 관여해야 하는 전제조건을 삭제했다.조롱거리로 보호되는 활동

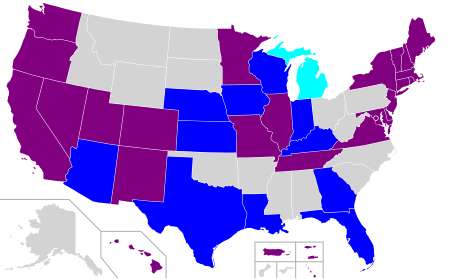

주 및 구

47개 주와 컬럼비아 구는 다양한 종류의 편견을 유발하는 폭력이나 협박(아칸소, 사우스캐롤라이나, 와이오밍 제외)을 범죄로 규정하고 있다.2004년 조지아 대법원에 의해 증오범죄 법령이 파기된 조지아는 2020년 6월 새로운 증오범죄법을 통과시켰다.[7][8]이 법령은 인종, 종교, 민족에 근거한 편견을 다루고 있다. 장애는 34개, 성적 지향은 34개, 성별은 30개, 트랜스젠더/성 정체성은 22개, 연령은 14개, 정치적 소속은 6개다.[9]워싱턴 D.C.와 함께 3명이 노숙자를 보호한다.[10]

34개 주와 컬럼비아 구는 유사한 행위에 대해 형사 처벌 외에 민사 소송의 원인이 되는 법률을 제정하고 있다.[9]

30개 주와 콜롬비아 특별구에는 주 정부가 증오 범죄 통계를 수집하도록 요구하는 법령이 있다. 이 중 20개는 성적 지향에 관한 것이다.[9]

27개 주와 콜롬비아 특별구에는 성별을 구체적으로 다루는 법령이 있다.[11]

18개 주는 성 정체성에 관한 범죄법을 싫어한다.[11]

3개 주와 컬럼비아 구역은 노숙자를 엄호한다.[10]

| 주 | 대상 클래스 | 출처 |

|---|---|---|

| 인종, 피부색, 종교, 국적, 민족성, 신체적, 정신적 장애 | [12] | |

| 인종, 성별, 색깔, 신조, 신체적 또는 정신적 장애, 조계 및 국가 기원 | [13] | |

| 인종, 피부색, 종교, 국적, 성적 지향, 성별, 장애 | [14][15] | |

| 다른 계층의 장애, 성별, 국적, 인종 또는 민족, 종교, 성적 지향 및 "개인 또는 집단과의 관계" | [16] | |

| 인종, 색깔, 조상, 종교, 국적, 신체적 또는 정신적 장애, 성적 지향 | [17] | |

| 인종, 종교, 민족, 장애, 성, 성적 지향, 성 정체성 또는 표현 | [18] | |

| 인종, 종교, 색, 장애, 성적 지향, 성 정체성, 국가 출신 및 조상 | [19] | |

| 인종, 피부색, 종교, 국적, 성별, 나이, 결혼 여부, 개인적 외모, 성적 성향, 성 정체성 또는 표현, 가족 책임, 노숙자, 신체적 장애, 결혼, 피해자의 정치적 소속 | [20] | |

| 인종, 종교, 민족, 색깔, 조상, 성적 지향 및 국가 기원 | [21] | |

| 인종, 피부색, 종교, 성별, 성별, 장애, 성적 지향, 국적 또는 민족성 | [22] | |

| 인종, 종교, 장애, 민족성, 국적, 성별 정체성 또는 표현, 성적 지향 | [23] | |

| 인종, 색깔, 조상, 종교, 그리고 국가 기원 | [24] | |

| 인종, 피부색, 신조, 종교, 조계, 성별, 성적 지향, 신체적 또는 정신적 장애, 그리고 다른 개인 또는 개인의 국가 기원 | [25] | |

| 색, 신조, 장애, 국적, 인종, 종교, 성적 지향 | [26][27] | |

| 인종, 색깔, 종교, 조계, 국가 출신, 정치적 소속, 성별, 성적 지향, 나이, 장애, 그리고 다른 계급 중 한 계급의 "사람과의 관계" | [28] | |

| 인종, 색깔, 종교, 민족, 국적, 성적 지향 | [29] | |

| 인종, 피부색, 종교, 성적 성향, 국적, 법 집행관, 소방관 또는 응급복무요원으로서의 고용 | [30] | |

| 인종, 나이, 성별, 종교, 색, 신조, 장애, 성적 지향, 국가 출신, 조계, 조직 내 구성원 또는 봉사, 그리고 법 집행관, 소방관 또는 응급 의료 서비스 직원으로 고용 | [31] | |

| 인종, 피부색, 종교, 성별, 조상, 국적, 신체적 또는 정신적 장애, 성적 지향 또는 노숙 | [32] | |

| 인종, 피부색, 종교적 신념, 성적 지향, 성별, 장애, 국가 출신, 노숙 | [33] | |

| 인종, 종교, 민족, 장애, 성별, 성 정체성 및 성적 지향 | [34] | |

| 인종, 색상, 종교, 성별 또는 국가 출신 | [35] | |

| 인종, 피부색, 종교, 성별, 성적 지향, 장애, 나이 및 국가 기원 | [36] | |

| 인종, 피부색, 조상, 민족, 종교, 국적, 성별, 법 집행관, 소방관 또는 응급 의료 기술자로서 고용 | [37] | |

| 인종, 피부색, 종교, 국적, 성별, 성적 지향, 장애 | [38] | |

| 인종, 신조, 종교, 색채, 국가 기원 | [39] | |

| 인종, 피부색, 종교, 조계, 국적, 성별, 성적 지향, 나이, 장애 | [40] | |

| 인종, 피부색, 종교, 국적, 신체적 또는 정신적 장애, 성적 지향 및 성 정체성 | [41] | |

| 종교, 인종, 신조, 성적 지향, 국적, 성별, 성 정체성 | [42] | |

| 인종, 피부색, 종교, 성별, 장애, 성적 지향, 성 정체성 또는 표현, 국가 출신 및 민족성 | [43] | |

| 인종, 종교, 색깔, 국가 기원, 조상, 나이, 장애, 성별, 성적 지향.성 정체성과 성 정체성 정체성 | [44] | |

| 인종, 피부색, 국적, 조계, 성별, 성 정체성, 종교, 종교, 나이, 장애, 성적 지향 | [45] | |

| 인종, 색깔, 종교, 국적, 원산지 | [46] | |

| 성별, 인종, 색상, 종교 및 국가 출신(공적인 장소에서의[47] 차별에만 해당) | [48] | |

| 인종, 민족적 배경, 종교 | [49] | |

| 인종, 피부색, 종교, 조계, 국적, 장애 | [50] | |

| 인종, 피부색, 종교, 성 정체성, 성적 지향, 장애 및 국가 기원 | [51] | |

| 인종, 색깔, 종교, 그리고 국가 기원 | [52] | |

| 장애, 종교, 색, 인종, 국적 또는 조상, 성적 지향 및 성별 | [53] | |

| 인종, 민족, 종교, 조상 또는 국가 출신 | [54] | |

| 인종, 종교, 색, 장애, 성적 지향, 국가 출신, 조상, 성별(성 정체성 암묵적으로 포함) | [55][56] | |

| 인종, 피부색, 장애, 종교, 국가 출신 또는 조상, 나이, 성별, 성적 선호도, 그리고 평화 장교 또는 판사로서의 지위별 | [57] | |

| 나이, 조상, 장애, 민족성, 가족 신분, 성 정체성, 노숙자, 결혼 여부, 결혼 여부, 국가 출신, 정치적 표현, 인종, 종교, 성별, 성적 지향, 병역, 응급 구조자로서의 지위, 법 집행관, 교정장교, 특수 기능장교 또는 기타 평화 담당 장교. | [58][59] | |

| 인종, 피부색, 종교, 국적, 성별, 조상, 나이, 미군 복무, 장애, 성적 지향, 성 정체성 | [60] | |

| 인종, 종교, 국적, 장애, 성적 지향, 성별, 성 정체성)[61][62] | [63][64] | |

| 인종, 색, 종교, 조계, 국가 출신, 성별, 성적 지향, 장애 및 성 정체성 | [65][66] | |

| 인종, 색깔, 종교, 조상, 국가 출신, 정치적 제휴, 성별 | [67] | |

| 인종, 종교, 색, 장애, 성적 지향, 국가 출신 및 조상 | [68] |

성적 지향과 성 정체성

- 1983

- 주 차원에서 LGBT 증오 범죄 법령 없음

- 1984

- 캘리포니아:증오 범죄 법령에[70] 포함된 성적 지향

- 1987

- 코네티컷: 증오 범죄 법령에[71] 포함된 성적 지향

- 1988

- 위스콘신 주: 증오 범죄 법령에[72] 포함된 성적 지향

- 1989

- 미네소타: 증오 범죄 법령에[73] 포함된 성적 지향

- 네바다: 증오 범죄 법령에[74] 포함된 성적 지향

- 오리건 주: 증오 범죄 법령에[75] 포함된 성적 지향

- 1990

- 컬럼비아 주의 구역:증오 범죄 법령에[76] 포함된 성적 성향과 성 정체성

- 뉴저지 주: 증오 범죄 법령에[77] 포함된 성적 지향

- 버몬트: 증오 범죄 법령에[78] 포함된 성적 지향

- 1991

- 플로리다: 증오 범죄 법령에[79] 포함된 성적 지향

- 일리노이:증오 범죄 법령에[80] 포함된 성적 지향

- 뉴햄프셔 주: 증오 범죄 법령에[81][82] 포함된 성적 지향

- 1992

- 아이오와: 증오 범죄 법령에[83] 포함된 성적 지향

- 미시간: 성적 지향은 증오 범죄 데이터 수집에만[84] 포함됨

- 1993

- 메인: 증오 범죄 법령에[85] 포함된 성적 지향

- 미네소타:증오 범죄 법령에[86] 포함된 성 정체성

- 텍사스: 증오 범죄 법령에[87] 포함된 성적 지향

- 워싱턴 주: 증오 범죄 법령에[88] 포함된 성적 지향

- 1996

- 매사추세츠 주: 증오 범죄 법령에[89] 포함된 성적 지향

- 1997

- 델라웨어: 증오 범죄 법령에[90] 포함된 성적 지향

- 루이지애나: 증오 범죄 법령에[91] 포함된 성적 지향

- 네브라스카: 증오 범죄 법령에[92] 포함된 성적 지향

- 1998

- 캘리포니아:증오 범죄 법령에[93] 포함된 성 정체성

- 로드 아일랜드: 증오 범죄 법령에[94] 포함된 성적 지향

- 1999

- 미주리: 증오 범죄 법령에[95] 포함된 성적 성향과 성 정체성

- 버몬트: 증오 범죄 법령에[78][96] 포함된 성 정체성

- 2000

- 인디애나: 성적 취향은 증오 범죄 데이터 수집에만[97] 포함됨

- 켄터키: 증오 범죄 법령에[98] 포함된 성적 지향

- 뉴욕: 증오 범죄 법령에[99][100][101] 포함된 성적 지향

- 테네시 주:증오 범죄 법령에[102] 포함된 성적 지향

- 2002

- 캔자스: 증오 범죄 법령에[103] 포함된 성적 지향

- 펜실베니아 주: 증오 범죄 법령에[104] 포함된 성적 성향과 성 정체성

- 푸에르토리코: 증오 범죄 법령에[105] 포함된 성적 지향과 성 정체성

- 2003

- 애리조나: 증오 범죄 법령에 포함된 성적 지향

- 하와이: 증오 범죄 법령에 포함된 성적 성향과 성 정체성

- 뉴멕시코: 증오 범죄 법령에 포함된 성적 지향과 성 정체성

- 2004

- 코네티컷:증오 범죄 법령에 포함된 성 정체성

- 조지아:성적인 성향과 성 정체성은 더 이상 조지아 대법원(미국 주)의 증오 범죄 법령에 보호 계급으로 명시적으로 명시되지 않았다.

- 2005

- 콜로라도: 성적 성향과 성 정체성은 증오 범죄 법령에 포함됨

- 메릴랜드: 증오 범죄 법령에 포함된 성적 성향과 성 정체성

- 2008

- 뉴저지 주: 증오 범죄 법령에 포함된 성 정체성

- 오리건 주: 증오 범죄 법령에 포함된 성 정체성

- 펜실베이니아: 펜실베이니아 대법원의 증오 범죄 법령에 더 이상 성적 지향과 성 정체성이 보호 계급으로 명시적으로 나열되지 않는다.

- 2012

- 메사추세츠 주: 증오 범죄 법령에[106] 포함된 성 정체성

- 로드 아일랜드: 증오 범죄 법령에 포함된 성 정체성

- 2013

- 델라웨어:증오 범죄 법령에 포함된 성 정체성

- 네바다: 증오 범죄 법령에 포함된 성 정체성

- 2016

- 일리노이:증오 범죄 법령에[107] 포함된 성 정체성

- 2019

- 테네시 주:증오 범죄 법령에[108] 포함된 성 정체성

- 인디애나: 증오 범죄 법령에[109] 포함된 성적 지향

- 유타: 성적 성향과[110] 성 정체성은 증오 범죄 법령에 포함됨

- 메인: 증오 범죄 법령에[64][111] 포함된 성적 성향과 성 정체성

- 뉴햄프셔: 증오 범죄 법령에[112] 포함된 성 정체성

- 워싱턴 주: 증오 범죄 법령에[113] 포함된 성 정체성

- 뉴욕 주: 증오 범죄 법령에[114] 포함된 성 정체성

- 2020

- 조지아:증오 범죄 법령에[22] 포함된 성적 지향

- 버지니아:증오 범죄 법령에[61][62][64] 포함된 성적 성향과 성 정체성

경찰과 소방관

2016년 5월 26일, 루이지애나는 존 벨 에드워즈 주지사가 입법부에서 법으로 개정안에 서명했을 때 경찰관들과 소방관을 주 증오 범죄 법령에 추가한 최초의 주였다.이번 개정안은 일부 흑인들에 대한 경찰의 만행을 종식시키려는 '흑인 생활 물질' 운동에 대한 대응 차원에서 '푸른 생명 물질'이라는 슬로건을 내걸고 수정안을 발의한 바 있다.블랙 라이프 매터(Black Lives Matter)가 창간된 이후, 비평가들은 이 운동의 수사적인 반경찰을 일부 발견했는데, 이 개정안의 저자인 랜스 해리스가 일부 "우리는 우리 장교들을 테러하기 위해 계획적인 캠페인을 벌이고 있다"고 언급하고 있다.2015년 텍사스 보안관 살해사건과 전년도에 뉴욕경찰관 2명이 살해된 사건에도 불구하고 에릭 가너 사망사건과 마이클 브라운 총격사건에 대한 대응으로 법 집행을 반대하는 증오범죄가 법안 통과 당시 공통적으로 문제였다는 자료가 거의 없었다.[115][116]개정안이 통과된 지 두 달도 채 되지 않아 배턴루즈는 배턴루즈 경찰이 백인 경찰관 2명에 의해 알톤 스털링을 살해한 후 전국적인 주목을 받았다.이로 인해 배턴루즈에서 시위가 일어나 수백 명이 체포되고 전국적으로 인종간 긴장이 고조되었다.이러한 시위가 있었던 주에는 댈러스에서 5명의 경찰관이 사망했고, 시위 다음 주에는 배턴 루즈에서 3명의 경찰관이 추가로 사망했다.두 명의 가해자 모두 살해되었고 두 건의 총격 사건의 동기는 경찰관들에 의한 최근 흑인 남성 살해에 대한 대응이었다.

2017년 켄터키는 경찰이나 긴급구조대를 공격하는 증오범죄가 된 두 번째 주가 됐다.[117]이것은 헤리티지 재단과 에드윈 미즈, 버나드 케릭과 같은 이념가들에 의해 장려된 "푸른 생명 물질" 법제의 일부였다.[118]같은 해 미시시피주는 증오범죄법을 법 집행관, 소방관, 비상근무자들을 대상으로 확대했다.[119]2019년 유타주에서는 경찰이나 긴급구조대원의 지위를 보호계급 명단에 추가했다.[120]2020년 조지아는 경찰관, 소방관, 응급의료 기술자에 대한 공격에 적용하여 편향성 협박죄의 신설법을 제정하였다.[121]

자료수집법령

1990년 증오 범죄 통계법

1990년 미국 28조 534조의 증오범죄 통계법은 법무장관이 피해자의 인종, 종교, 장애, 성적 성향 또는 민족성 때문에 저지른 범죄에 대한 자료를 수집하도록 규정하고 있다.[122]이 법안은 조지 H. W. 부시에 의해 1990년에 법으로 제정되었으며, "게이, 레즈비언, 양성애자를 인정하고 이름을 붙인 최초의 연방 법령이었다."[123]1992년부터 법무부와 FBI는 공동으로 증오 범죄 통계에 관한 연례 보고서를 발간했다.[124]

1994년 강력범죄단속 및 법집행법

1994년 강력범죄통제 및 법집행법은 FBI의 필수자료 범위를 장애에 근거한 증오범죄로 확대하였으며, FBI는 1997년 1월 1일부터 장애편향 범죄에 대한 자료 수집에 착수하였다.[125]1996년 의회는 이 법을 영구적으로 재승인했다.

캠퍼스 증오 범죄 1997년 법

1997년의 캠퍼스 증오범죄 알권리법은 20 § )를 제정하여[citation needed] 캠퍼스 보안 당국이 인종, 성별, 종교, 성적 지향, 민족성 또는 장애에 근거하여 저질러진 증오 범죄에 관한 자료를 수집하고 보고하도록 하고 있다.[citation needed]이 법안은 로버트 토리첼리 상원의원이 전면에 내세웠다.[citation needed]

유병률

DOJ와 FBI는 증오범죄 통계법에 따라 1992년부터 사법기관에 보고된 증오범죄 통계를 수집해 왔다.FBI의 형사사법정보국은 매년 획일적인 범죄 보고 프로그램의 일환으로 이러한 통계를 발표해 왔다.이들 보고서에 따르면 1991년 이후 발생한 11만3000여 건의 증오범죄 중 55%는 인종편향, 17%는 종교편향, 14%는 성적 지향편향, 14%는 민족편향, 1%는 장애편향에 의해 동기부여가 됐다.[126]데이비드 레이 증오 범죄 예방법

아래 표의 수치는 매년 모든 보고 기관의 데이터를 포함하지 않는다는 점에 유의하십시오.2004년 수치는 254,104,439,2014년 297,926,030명의 인구를 포함했다.

| 바이어스 모티브 | 1995 | 1996[127] | 1997[128] | 1998[129] | 1999[130] | 2000[131] | 2001[132] | 2002[133] | 2003[134] | 2004[135] | 2005[136] | 2006[137] | 2007[138] | 2008[139] | 2009[140] | 2010[141] | 2011[142] | 2012[143] | 2013[144] | 2014[145] | 2015[146] | 2016[147] | 2017[148] | 2018[149] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 인종 | 6,438 | 6,994 | 6,084 | 5,514 | 5,485 | 5,397 | 5,545 | 4,580 | 4,754 | 5,119 | 4,895 | 5,020 | 4,956 | 4,934 | 4,057 | 3,949 | 3,645 | 3,467 | 3,563 | 3,227 | ||||

| 인종/이종성/종교 | 4,216 | 4,426 | 5,060 | 5,155 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 종교 | 1,617 | 1,535 | 1,586 | 1,720 | 1,686 | 1,699 | 2,118 | 1,659 | 1,489 | 1,586 | 1,405 | 1,750 | 1,628 | 1,732 | 1,575 | 1,552 | 1,480 | 1,340 | 1,223 | 1,140 | 1,402 | 1,584 | 1,749 | 1,617 |

| 성적 지향 | 1,347 | 1,281 | 1,401 | 1,488 | 1,558 | 1,558 | 1,664 | 1,513 | 1,479 | 1,482 | 1,213 | 1,472 | 1,512 | 1,706 | 1,482 | 1,528 | 1,572 | 1,376 | 1,461 | 1,248 | 1,263 | 1,255 | 1,338 | 1,445 |

| 민족/민족 출신 | 1,044 | 1,207 | 1,132 | 956 | 1,040 | 1,216 | 2,634 | 1,409 | 1,326 | 1,254 | 1,228 | 1,305 | 1,347 | 1,226 | 1,109 | 1,122 | 939 | 866 | 821 | 821 | ||||

| 장애 | 알 수 없는 | 알 수 없는 | 12 | 27 | 23 | 36 | 37 | 50 | 43 | 73 | 54 | 95 | 84 | 85 | 99 | 48 | 61 | 102 | 99 | 96 | 88 | 77 | 160 | 179 |

| 성별 | 알 수 없는 | 알 수 없는 | 알 수 없는 | 알 수 없는 | 알 수 없는 | 알 수 없는 | 알 수 없는 | 알 수 없는 | 알 수 없는 | 알 수 없는 | 알 수 없는 | 알 수 없는 | 알 수 없는 | 알 수 없는 | 알 수 없는 | 알 수 없는 | 알 수 없는 | 알 수 없는 | 30 | 40 | 30 | 36 | 54 | 61 |

| 젠더 아이덴티티 | 알 수 없는 | 알 수 없는 | 알 수 없는 | 알 수 없는 | 알 수 없는 | 알 수 없는 | 알 수 없는 | 알 수 없는 | 알 수 없는 | 알 수 없는 | 알 수 없는 | 알 수 없는 | 알 수 없는 | 알 수 없는 | 알 수 없는 | 알 수 없는 | 알 수 없는 | 알 수 없는 | 33 | 109 | 122 | 131 | 132 | 189 |

| 싱글 바이아스 | 10,446 | 11,017 | 10,215 | 9705 | 9,792 | 9,906 | 11,998 | 9,211 | 9,091 | 9,514 | 8,795 | 9,642 | 9,527 | 9,683 | 8,322 | 8,199 | 7,697 | 7,151 | 7,230 | 6,681 | 7,121 | 7,509 | 8,493 | 8,646 |

| 다중 바이아스 | 23 | 22 | 40 | 17 | 10 | 18 | 22 | 11 | 9 | 14 | 9 | 10 | 8 | 8 | 14 | 9 | 16 | 13 | 12 | 46 | 52 | 106 | 335 | 173 |

| 합계 | 10,469 | 11,039 | 10,255 | 9,722 | 9,802 | 9,924 | 12,020 | 9,222 | 9,100 | 9,528 | 8,804 | 9,652 | 9,535 | 9,691 | 8,336 | 8,208 | 7,713 | 7,164 | 7,242 | 6,727 | 7,173 | 7,615 | 8,828 | 8,819 |

참고: 피해자라는 용어는 사람, 기업, 기관 또는 사회 전체를 지칭할 수 있다.FBI는 1992년부터 UCR 자료를 수집해 왔지만 1992년부터 1994년까지의 보고서는 FBI 웹사이트에서 볼 수 없다.단일 생물 희생자의 총계는 1995-1998년에 계산되었다.인종과 민족/민족 출신은 2015년부터 통합되었다.

| 공격형 | 증오 범죄 | 미국의 모든 범죄 |

|---|---|---|

| 살인 및 비절도죄 | 7 | 16,272 |

| 강제강간 | 11 | 89,000 |

| 강도 | 145 | 441,855 |

| 가중폭행 | 1,025 | 834,885 |

| 도둑질 | 158 | 2,222,196 |

| 라르케니테프트 | 224 | 6,588,873 |

| 자동차 절도 | 26 | 956,846 |

노숙자 취재

플로리다, 메인, 메릴랜드, 워싱턴 D.C.는 개인의 노숙자 지위를 포함하는 증오 범죄법을 가지고 있다.[10]

2007년 한 연구에서는 노숙인을 대상으로 한 강력범죄가 증가하고 있는 것으로 나타났다.[151][152]2005년의 이러한 기록적인 범죄의 비율은 1999년의 그것보다 30% 더 높았다.[153]전체 가해자의 75%가 25세 미만이다.연구와 조사에 따르면, 노숙자들이 무주택자들보다 범죄 피해율이 훨씬 높지만, 대부분의 사건들은 당국에 보고되지 않는다.

최근 몇 년 동안, 노숙자들에 대한 폭력 문제는 주로 전국 노숙자 연합과 학계 연구자들의 노력 덕택에 전국적인 주목을 받았다.NCH는 미국 메인스트리트의 '미움, 폭력, 죽음'[154] 보고서에서 노숙자들의 증오 범죄에 대한 고의적인 공격을 비난했다.

샌 버나디노 캘리포니아 주립대학의 증오 및 극단주의 연구 센터는 "혐오 살인"으로 155명의 노숙자가 사망했고, 인종과 종교와 같은 다른 전통적인 증오 범죄 범주에서 76명이 사망했다고 밝혔다.[152]CSE는 노숙자들의 부정적이고 모욕적인 묘사가 폭력이 일어나는 기후에 기여한다고 주장한다.

토론

Penalty-enhancement 증오 범죄 법 전통적으로 있다는 이유로, 대법원장 렌퀴스트의 말로, 이 행동 더 큰 개인과 사회적 피해를 입히는 것으로 생각된다에.... bias-motivated 범죄 더욱 희생자들에게 뚜렷한 감정적인 손해를 입히다 그리고 사회 불안을 부채질한 보복 범죄를 일으킬 것 겉다 정당화된다."[155]

백인의 취재

2001년 보고서에서 캠퍼스에서 증오 범죄:문제와 노력, 스티븐 Wessler와 마가렛 모스 센터의 예방이 싫어 폭력의 서던 Maine,[156]의에 의해, 그것에 직면하기에 저자들은 비록 적은 증오 범죄 백인이 반대자보다 다른 그룹을 향한 것입니다도었고 프로 되어 주목하고 있다.secut대법원이 수정헌법 제1조의 공격에 반대하는 증오 범죄 법안을 지지한 508년 미국 476년(1993) 위스콘신 대 미첼 사건에는 백인 피해자가 연루됐다.[157][155]FBI가 1990년 증오범죄통계법(Heat Crime Statistics Act of 1990)의 후원으로 수집한 2002년 발표된 증오범죄 통계는 7000건이 넘는 증오범죄 사건을 기록했으며, 그 중 약 5분의 1은 백인이었다.[158]그러나 이러한 통계는 논쟁을 불러일으켰다.FBI가 1993년 발표한 증오범죄 통계에서도 전체 증오범죄의 20%를 백인에 대해 유사하게 보도한 것은 질 트레고르 인터그룹 클리닝하우스 상임이사가 "혐오범죄법이 덮으려는 것의 남용"이라며 이들 범죄의 백인 피해자들이 증오범죄를 일삼고 있다고 비난했다.소수민족들을 더욱 처벌하기 위한 수단으로서 [159]e법률

제임스 B. 제이콥스와 킴벌리 포터는 백인들에 의한 증오 범죄의 희생자인 사람들의 곤경에 동정심을 가질 수 있는 사람들을 포함한 백인들은 백인들에 대한 증오 범죄는 다른 집단들에 대한 증오 범죄보다 다소 열등하고 가치도 떨어진다는 생각에 화가 치밀어 오른다고 지적했다.그들은 알츠칠러에 의해 언급된 바와 같이 증오범죄법이 그러한 구별을 하지 않지만, 이 명제는 증오범죄의 범주에서 백인들에 대한 증오범죄의 제거를 주장해 온 "유명한 출판물에 등장하는 많은 작가들"에 의해 주장되어온 것으로 보고 있다."보호된 그룹"에 대한 확정 작업.제이콥스와 포터는 그러한 움직임은 "사회적 갈등과 헌법적 우려의 잠재력을 가지고 있다"[159]고 단호하게 주장한다.

미 연방수사국(FBI)은 2019년 반(反)백(白)혐오 범죄 피해자 중 반(反)아시아나 반(反)아랍(反)흑(反)혐오 범죄 피해자보다 적은 775명을 명단에 올렸다.[160]2008년과 2012년 사이에, 반백색 증오 범죄는 반흑색 및 반LGBT 증오 범죄에 뒤이어 세 번째로 흔한 형태의 증오 범죄였다. (자세한 증오 범죄#미국에서 빅팀 참조)

참고 항목

참조

- ^ "Federally Protected Activities". United States Department of Justice, Civil Rights Division. Archived from the original on 1 January 2011.

- ^ "Federal Civil Rights Statutes". Federal Bureau of Investigation.

- ^ "Hate Crime Sentencing Act". Anti-Defamation League. Archived from the original on 7 July 2009. Retrieved 10 December 2009.

- ^ "S. 1890 (104th): Church Arson Prevention Act of 1996". GovTrack.us. Civic Impulse, LLC. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- ^ a b "H.R. 3525 (104th): Church Arson Prevention Act of 1996". GovTrack.us. Civic Impulse, LLC. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- ^ "Civil Rights Monitor". The Leadership Conference. The Leadership Conference Education Fund. Archived from the original on 2014-11-29. Retrieved 19 November 2014.

- ^ "Nation In Brief". The Washington Post. 2004-10-26. Retrieved 2010-05-04.

- ^ "Georgia's Kemp signs hate crimes law after outcry over death". AP NEWS. 2020-06-26. Retrieved 2020-06-30.

- ^ a b c "Anti-Defamation League State Hate Crime Statutory Provision" (PDF). Anti-defamation League. 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 14, 2007. Retrieved April 1, 2021.

- ^ a b c "Florida among first states to make attacks on homeless hate crimes". Retrieved May 25, 2010. 2010년 5월 18일, 올랜도 센티넬, 인용: "플로리다는 메릴랜드, 메인, 워싱턴 D.C에 뒤이어 노숙자들에 대한 공격을 증오 범죄로 만드는 네 번째 관할권이 된다."

- ^ a b "ADL Hate Crime Map". Anti-Defamation League. Retrieved April 8, 2021.

- ^ Alabama State Legislature. "Section 13A-5-13 - Crimes motivated by victim's race, color, religion, national origin, ethnicity, or physical or mental disability". Code of Alabama. Retrieved 19 June 2019.

- ^ AS 12.55.155

- ^ Arizona State Legislature. "Section 13-701. Sentence of imprisonment for felony; presentence report; aggravating and mitigating factors; consecutive terms of imprisonment; definition". Arizona Revised Statutes. Retrieved 22 June 2019.

15. Evidence that the defendant committed the crime out of malice toward a victim because of the victim's identity in a group listed in section 41-1750, subsection A, paragraph 3 or because of the defendant's perception of the victim's identity in a group listed in section 41-1750, subsection A, paragraph 3.

- ^ Arizona State Legislature. "Section 41-1750. Central state repository; department of public safety; duties; funds; accounts; definitions". Arizona Revised Statutes. Retrieved 22 June 2019.

- ^ California State Legislature (2004). "CHAPTER 1. Definitions [422.55 - 422.57]". Penal Code of California. Retrieved 22 June 2019.

- ^ Colorado General Assembly. "Section 18-9-121. Bias-motivated crimes". Colorado Revised Statutes. LexisNexis. Retrieved 22 June 2019.

- ^ Connecticut General Assembly. "Chapter 952 - Penal Code: Offenses". General Statutes of Connecticut. Retrieved 22 June 2019.

Sec. 53a-181j. Intimidation based on bigotry or bias in the first degree: Class C felony [infra]

- ^ Delaware General Assembly. "TITLE 11 - CHAPTER 5. SPECIFIC OFFENSES - Subchapter VII. Offenses Against Public Health, Order and Decency". Delaware Code Online. Retrieved 22 June 2019.

§ 1304 Hate crimes; class A misdemeanor, class G felony, class F felony, class E felony, class D felony, class C felony, class B felony, class A felony. [infra]

- ^ Council of the District of Columbia. "Chapter 37. Bias-Related Crime". Code of the District of Columbia. Retrieved 22 June 2019.

- ^ Florida Legislature. "877.19 Hate Crimes Reporting Act.—". 2018 Florida Statutes. Retrieved 22 June 2019.

- ^ a b Slotkin, Jason (June 25, 2020). "After Ahmaud Arbery's Killing, Georgia Governor Signs Hate Crimes Legislation". NPR. Retrieved April 1, 2021.

- ^ Hawaii Legislature. "§846-51 Definitions". 2018 Hawaii Revised Statutes. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

- ^ Idaho Legislature. "Section 18-7901. PURPOSE". Idaho Statutes. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

- ^ Illinois General Assembly. "Article 12 - Subdivision 15. Intimidation". Retrieved 4 July 2019.

Sec. 12-7.1. Hate crime. [infra]

- ^ Senate Bill No. 198 of 2019. Indiana General Assembly. p. 2. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

- ^ Indiana General Assembly. "IC 10-13-3-1 "Bias crime"". Indiana Code. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

- ^ Iowa Legislature. "CHAPTER 729A - VIOLATION OF INDIVIDUAL RIGHTS — HATE CRIMES". Iowa Code. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

- ^ Kansas State Legislature. "21-6815. Imposition of presumptive sentence; jury requirements; departure sentencing; substantial and compelling reasons for departure; mitigating and aggravating factors". Kansas Statutes. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

(C) The offense was motivated entirely or in part by the race, color, religion, ethnicity, national origin or sexual orientation of the victim or the offense was motivated by the defendant's belief or perception, entirely or in part, of the race, color, religion, ethnicity, national origin or sexual orientation of the victim whether or not the defendant's belief or perception was correct.

- ^ Kentucky State Legislature. "532.031 Hate crimes -- Finding – Effect -- Definitions" (PDF). Kentucky Revised Statutes. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- ^ Louisiana State Legislature. "§107.2. Hate crimes". Louisiana Revised Statutes. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- ^ Maine State Legislature. "Title 17-A, §1151. Purposes". Maine Revised Statutes. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- ^ Maryland General Assembly. "Criminal Law" (PDF). Maryland Code. p. 425. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

§10–304. [infra]

- ^ Massachusetts General Court. "Part I, Title II, Chapter 22C, Section 32: Definitions applicable to Secs. 33 to 35". Massachusetts General Laws. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- ^ "Michigan Legislature - Section 750.147b". www.legislature.mi.gov. Retrieved 2021-02-04.

- ^ Minnesota Legislature. "611A.79 CIVIL DAMAGES FOR BIAS OFFENSES". 2018 Minnesota Statutes. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- ^ Mississippi Legislature. "§ 99-19-301. Penalties subject to enhancement; definitions". Mississippi Code of 1972. LexisNexis. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- ^ Missouri Legislature. "557.035. Hate offenses — provides enhanced penalties for motivational factors in certain offenses". Revised Statutes of Missouri. Missouri Reviser of Statutes. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- ^ Montana Legislature. "45-5-221. Malicious intimidation or harassment relating to civil or human rights -- penalty". Montana Code Annotated 2017. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- ^ Nebraska Legislature. "28-111. Enhanced penalty; enumerated offenses". Nebraska Revised Statutes. Retrieved 9 July 2019.

- ^ Nevada Legislature. "Title 15 - Crime and Punishments: Chapter 193 - General Provisions". Nevada Revised Statutes. Retrieved 9 July 2019.

NRS 193.1675 Additional penalty: Commission of crime because of certain actual or perceived characteristics of victim. [infra]

- ^ New Hampshire General Court. "651:6 Extended Term of Imprisonment". New Hampshire Statutes. Retrieved 9 July 2019.

- ^ New Jersey Legislature. "2C:16-1 Bias intimidation". New Jersey Legislative Statutes. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 9 July 2019.

- ^ New Mexico Legislature. "31-18B-3. Hate crimes; noncapital felonies, misdemeanors or petty misdemeanors committed because of the victim's actual or perceived race, religion, color, national origin, ancestry, age, disability, gender, sexual orientation or gender identity; alteration of basic sentence". NMOneSource.com. New Mexico Compilation Commission. Retrieved 9 July 2019.

- ^ 뉴욕 주 입법부.형법 § 485.00 뉴욕 통합법률.

- ^ North Carolina General Assembly. "§ 15A-1340.16. Aggravated and mitigated sentences" (PDF). North Carolina General Statutes. Retrieved 9 July 2019.

(17) The offense for which the defendant stands convicted was committed against a victim because of the victim's race, color, religion, nationality, or country of origin.

- ^ "After Ugly Incident In Fargo, A Push For Hate Crime Laws". WCCO. Associated Press. 17 September 2017. Retrieved 9 July 2019.

- ^ North Dakota Legislature. "CHAPTER 12.1-14 - OFFICIAL OPPRESSION - ELECTIONS - CIVIL RIGHTS" (PDF). North Dakota Century Code. Retrieved 9 July 2019.

- ^ Ohio Legislature. "2929.12 Seriousness of crime and recidivism factors". Ohio Revised Code. Retrieved 9 July 2019.

- ^ Oklahoma Legislature. "Title 21. Crimes and Punishments" (RTF). Oklahoma Statutes. p. 227. Retrieved 9 July 2019.

- ^ Section 1, Senate Bill No. 577 of 2019 (PDF). Oregon State Legislature. Retrieved 9 July 2019.

- ^ Pennsylvania General Assembly. "Title 18 - Crimes and Offenses" (PDF). Pennsylvania Consolidated Statutes. p. 95. Retrieved 9 July 2019.

- ^ Rhode Island General Assembly. "§ 12-19-38. Hate Crimes Sentencing Act". Rhode Island General Laws. Retrieved 9 July 2019.

- ^ South Dakota Legislature. "Chapter 22-19B - Hate Crimes". South Dakota Codified Laws. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- ^ Tennessee General Assembly. "§ 40-35-114. Enhancement factors". Tennessee Code Unannotated. LexisNexis. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

(17) The defendant intentionally selected the person against whom the crime was committed or selected the property that was damaged or otherwise affected by the crime, in whole or in part, because of the defendant's belief or perception regarding the race, religion, color, disability, sexual orientation, national origin, ancestry or gender of that person or the owner or occupant of that property; however, this subdivision (17) should not be construed to permit the enhancement of a sexual offense on the basis of gender selection alone;

- ^ Allison, Natalie (14 February 2019). "Tennessee becomes first state in the South with hate crime law protecting transgender people". The Tennessean. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- ^ Texas Legislature. "Chapter 42. Judgment and Sentence". Texas Code of Criminal Procedure. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

Art. 42.014. FINDING THAT OFFENSE WAS COMMITTED BECAUSE OF BIAS OR PREJUDICE. [infra]

- ^ "76-3-203.14. Victim targeting penalty enhancement -- Penalties". utah.gov. Retrieved July 10, 2021.

- ^ Utah Sate Legislature. "76-3-203.3. Penalty for hate crimes -- Civil rights violation". Utah Code. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- ^ Vermont General Assembly. "Title 13: Crimes And Criminal Procedure - Chapter 33: Injunctions Against Hate-motivated Crimes". Vermont Statutes Online. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- ^ a b Van Slooten, Philip (March 5, 2020). "VA. Governor Signs Three LGBTQ Bills into Law". Washington Blade. Retrieved April 1, 2021.

- ^ a b Sprayregen, Molly (March 6, 2020). "Virginia's Governor Just Signed 3 Pro-LGBTQ Bills". LGBTQ Nation. Retrieved April 1, 2021.

- ^ Virginia General Assembly. "§ 52-8.5. Reporting hate crimes". Code of Virginia. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- ^ a b c "Hate Crime Laws". LGBT Map. Retrieved April 1, 2021.

- ^ Washington State Legislature. "9A.36.078: Malicious harassment—Finding". Revised Code of Washington. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- ^ Section 1, Chapter No. 271 of 2019 (PDF). Washington State Legislature. p. 1. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- ^ WVC §61-6-21

- ^ Wisconsin Legislature. "939.645 Penalty; crimes committed against certain people or property". Wisconsin Statutes. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- ^ 2006년 6월, 명예훼손 방지 연맹.2007-05-04 검색됨;

- ^ Lewis, Daniel (2013). "Direct Democracy and Pro-Minority Policies". Direct Democracy and Minority Rights: A Critical Assessment of the Tyranny of the Majority in the American States. Controversies in Electoral Democracy and Representation. Routledge. p. 76. ISBN 978-1-136-26934-9 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Connecticut". GayLawNet®™.

- ^ "1987 Wisconsin Act 348" (PDF).

- ^ "Chapter 261". Minnesota Session Laws. The Office of the Revisor of Statutes. 1989.

- ^ "1989 Statutes of Nevada, Page 898 (Chapter 416, AB 629)".

- ^ Nicola, George T. (June 16, 2015). "Milestones in Oregon LGBTQ Law". Gay & Lesbian Archives of the Pacific Northwest. 1989: Oregon hate crime law that includes sexual orientation.

- ^ "District of Columbia". GayLawNet®™.

- ^ Jacobs, James B.; Potter, Kimberly (2000). "Social Construction of a Hate Crime Epidemic". Hate Crimes: Criminal Law & Identity Politics. Studies in Crime and Public Policy. Oxford University Press. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-19-803222-9.

- ^ a b Bernsten, Mary (2002). "The Contradictions of Gay Ethnicity: Forging Identity in Vermont". In Meyer, David S.; Whittier, Nancy; Robnett, Belinda (eds.). Social Movements: Identity, Culture, and the State. Oxford University Press. pp. 96–97. ISBN 978-0-19-514356-0 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Hate Crimes - Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgendered, Queer Resources". UCF Research Guides. University of Central Florida Libraries. Florida Hate Crimes Act, 1991 revisions.

- ^ "In re B.C. et al., Minors". Model Penal Code Annotated. University of Toronto. Archived from the original on January 25, 2015.

- ^ "HB 1299 - Bill Text". Gencourt.state.nh.us. 1991-01-01. Retrieved 2013-12-05.

- ^ "Docket of HB1299". Gencourt.state.nh.us. Retrieved 2013-12-05.

- ^ "Iowa Civil Rights Commission 1993 Annual Report Fair Housing Education".

- ^ "Section 28.257a Crimes motivated by prejudice or bias; report". Michigan Legislature.

- ^ "2011 Maine Revised Statutes TITLE 5: ADMINISTRATIVE PROCEDURES AND SERVICES Chapter 337-B: CIVIL RIGHTS ACT 5 §4684-A. Civil rights". Justia: US Law.

- ^ "DENNIS HOLLINGSWORTH, et al., Petitioners, v. KRISTIN M. PERRY, et al" (PDF). American Bar Association.

- ^ "Title 1, Chapter 42. Judgment and Sentence". Code of Criminal Procedure. Texas Legislature.

- ^ "Washington". GayLawNet®™.

- ^ Wong, Doris Sue (June 21, 1996). "Senate Expands Hate-crime Law". Boston Globe. Retrieved March 9, 2011.

- ^ "Chapter 175, Formerly Senate Bill No. 53, As Amended by Senate Amendment No. 1: An Act to Amend Title I1 of the Delaware Code Relating to Hate Crimes". Delaware Code Online. State of Delaware.

- ^ "Hate Crimes Bill Out Of Committee With 'Sexual Orientation' Intact". Ambush Magazine. May 1997. Retrieved December 23, 2013.

- ^ "Nebraska Passes Hate Crimes Law" (PDF). Academic Freedom Coalition of Nebraska.

- ^ Kuehl (September 28, 1998). "Complete Bill History: A.B. No. 1999".

- ^ "§ 12-19-38 Hate Crimes Sentencing Act". State of Rhode Island.

- ^ "Hate crimes--provides enhanced penalties for motivational factors in certain crimes--definitions". Missouri Revised Statutes. August 28, 2003. Archived from the original on October 27, 2004.

- ^ Wyman, Hastings (2005). "Transgender and Bisexual Issues in Public Administration and Policy". In Swan, Wallace (ed.). Handbook of Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transgender Administration and Policy. Public Administration and Public Policy. Vol. 106. Taylor & Francis. p. 131. ISBN 978-0-8247-5087-9 – via Google Books.

- ^ "House Bill No. 1011". State of Indiana.

- ^ Robinson, B.A. (June 9, 2011). "U.S. hate crimes: Definitions by various groups, State/federal laws". ReligiousTolerance.org. Ontario Consultants on Religious Tolerance.

- ^ "S04691". New York State Assembly. Retrieved July 26, 2011.

- ^ Hernandez, Raymond (11 July 2000). "Pataki Signs Bill Raising Penalties In Hate Crimes". New York Times. Retrieved July 26, 2011.

- ^ Ball, Bryan (20 January 2011). "Last year saw progress on issues of gay rights". Buffalo News. Archived from the original on 23 January 2011. Retrieved July 25, 2011.

- ^ "Tennessee". GayLawNet®™.

- ^ "Kansas". GayLawNet®™.

- ^ "National Gay and Lesbian Task Force Applauds Governor Schweiker for Signing Bill Adding Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity To Existing Classes, December 3, 2002". Pennsylvania Expands Hate Crimes Law. National Gay and Lesbian Task Force. Archived from the original on March 23, 2012. Retrieved January 25, 2013.

- ^ Coto, Danica (9 June 2011). "Puerto Rican activists demand hate-crime charges amid gay, lesbian and transgender slayings". The Miami Herald. Associated Press. Retrieved April 8, 2014.

- ^ Barusch, M.; Reuben, Catherine E. (May 8, 2012). "Transgender Equal Rights In Massachusetts: Likely Broader Than You Think". Boston Bar Journal. Boston Bar Association. 56 (2). Retrieved September 28, 2012.

- ^ Lovett, Colin (July 20, 2015). "Illinois Gov. Bruce Rauner Signs Enhanced Hate Crimes Law". LGBTQ Nation.

- ^ Grady, James (13 February 2019). "TN Attorney General Opinion on anti-Trans Hate Crimes". Out and About Nashville®™. Retrieved 27 February 2019.

- ^ "Former IN Supreme Court Justice says New Hate Crimes Law Protects Gender, Gender Identity". WTHR. April 3, 2019. Retrieved April 1, 2021.

- ^ Stevens, Taylor (April 2, 2019). "At 'Historic' Ceremony, Utah Governor Signs New Hate Crimes Bill into Law". The Salt Lake Tribune. Retrieved April 1, 2021.

- ^ "Title 17-A: Main Criminal Code Part 1: General Principles Chapter 5: Defenses and Affirmative Defences Justification". Main Legislature. Retrieved April 1, 2021.

- ^ "Title LXII Criminal Code Chapter 651 Sentences General Provisions". The General Court of New Hampshire. Retrieved April 1, 2021.

- ^ "Bias-Based Crimial Offenses - Hate Crimes" (PDF). July 28, 2019. Retrieved April 1, 2021.

- ^ "Update: New York Governor Signs Gender Identity Discrimination Ban Into Law". The National Law Review. January 28, 2019. Retrieved April 1, 2021.

- ^ Pérez-Peña, Richard (27 May 2016). "Louisiana Enacts Hate Crimes Law to Protect a New Group: Police". The New York Times. Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- ^ Harris, Lance. "House Bill No. 953" (PDF). Louisiana State Legislature. Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- ^ Reinhard, Beth (March 22, 2017). "Kentucky Law Makes It a Hate Crime to Attack a Police Officer". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved July 10, 2021.

- ^ Platt, Tony (March 3, 2020). "1 Insecurity Syndrome: The Challenges of Trump's Carceral State". In van der Woude, Maartje; Koulish, Robert (eds.). Crimmigrant Nations: Resurgent Nationalism and the Closing of Borders. Fordham University Press. ISBN 9780823287505. Retrieved July 10, 2021.

- ^ Wagster Pettus, Emily (June 30, 2017). "New laws in Mississippi: Buckle up in backseat". Clarion Ledger. Associated Press. Retrieved July 10, 2021.

- ^ Stevens, Taylor (March 13, 2019). "Utah is about to get a tougher hate crimes law after final legislative OK". The Salt Lake Tribune. Retrieved July 10, 2021.

- ^ Amy, Jeff (August 5, 2020). "Georgia governor signs new law to protect police". The Washington Post. AP. Retrieved July 10, 2021.

- ^ "Appendix A". Hate Crime Statistics, 2004. FBI. Archived from the original on January 14, 2009.

- ^ "Hate Crimes Protections Timeline". National Gay and Lesbian Task Force. Archived from the original on 2014-04-01. Retrieved 2007-05-04.

- ^ a b "Uniform Crime Reports". CJIS. FBI. Archived from the original on 24 October 2004. Retrieved 10 December 2009.

- ^ "Hate crime statistics 1996" (PDF). CJIS. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-07-09. Retrieved 10 December 2009.

- ^ 에이브럼스, J. 하우스, 확장 증오 범죄 법안 통과, 가디언 언리미티드, 05-03-2007.05-03-2007년에 검색됨.

- ^ "Hate Crime Statistics 1996". Federal Bureau of Investigation. Retrieved April 8, 2021.

- ^ "Hate Crime Statistics 1997". Federal Bureau of Investigation. Retrieved April 8, 2021.

- ^ "Hate Crime Statistics 1998". Federal Bureau of Investigation. Retrieved April 8, 2021.

- ^ "Hate Crime Statistics 1999". Federal Bureau of Investigation. Retrieved April 8, 2021.

- ^ "Hate Crime Statistics 2000". Federal Bureau of Investigation. Retrieved April 8, 2021.

- ^ "Hate Crime Statistics 2001". Federal Bureau of Investigation. Retrieved April 8, 2021.

- ^ "Hate Crime Statistics 2002". Federal Bureau of Investigation. Retrieved April 8, 2021.

- ^ "Hate Crime Statistics 2003". Federal Bureau of Investigation. November 2004. Retrieved April 8, 2021.

- ^ "Hate Crime Statistics 2004". Federal Bureau of Investigation. Retrieved April 8, 2021.

- ^ "Hate Crime Statistics 2005". Federal Bureau of Investigation. October 2006. Retrieved April 8, 2021.

- ^ "Hate Crime Statistics 2006". Federal Bureau of Investigation. November 2005. Retrieved April 8, 2021.

- ^ "Hate Crime Statistics 2007". Federal Bureau of Investigation. October 2006. Retrieved April 8, 2021.

- ^ a b "Hate Crime Statistics 2008". Federal Bureau of Investigation. November 2009. Archived from the original on May 14, 2013. Retrieved April 8, 2021.

- ^ "Hate Crime Statistics 2009". Federal Bureau of Investigation. November 2010. Retrieved April 8, 2021.

- ^ "Hate Crime Statistics 2010". Federal Bureau of Investigation. Retrieved April 8, 2021.

- ^ "Hate Crime Statistics 2011". Federal Bureau of Investigation. Retrieved April 8, 2021.

- ^ "Hate Crime Statistics 2012". Federal Bureau of Investigation. Retrieved April 8, 2021.

- ^ "Hate Crime Statistics 2013". Federal Bureau of Investigation. Retrieved April 8, 2021.

- ^ "Hate Crime Statistics 2014". Federal Bureau of Investigation. Retrieved April 8, 2021.

- ^ "Hate Crime Statistics 2015". Federal Bureau of Investigation. Retrieved April 8, 2021.

- ^ "Hate Crime Statistics 2016". Federal Bureau of Investigation. Retrieved April 8, 2021.

- ^ "Hate Crime Statistics 2017". Federal bureau of Investigation. Retrieved April 8, 2021.

- ^ "Hate Crime Statistics 2018". Federal Bureau Investigation. Retrieved April 8, 2021.

- ^ "Crime in the United States 2008". Federal Bureau of Investigation. Archived from the original on September 22, 2009. Retrieved April 8, 2021.

- ^ Lewan, Todd (April 8, 2007). "Unprovoked Beatings of Homeless Soaring". Boston News. Retrieved April 1, 2021.

- ^ a b 전국 노숙자 연합,

- ^ "A Dream Denied: The Criminalization of Homelessness in U.S. Cities" (PDF). National Coalition for the Homeless. January 2006. Retrieved April 1, 2021.

- ^ Hate, Violence, and Death on Main Street USA: A report on Hate Crimes and Violence Against People Experiencing Homelessness, National Coalition for the Homeless, 2008

- ^ a b 위스콘신 대 미첼 사건, 508 U.S. 476 (1993)

- ^ Wessler, Stephen; Moss, Margaret (October 2001). "Hate Crimes on Campus: The Problem and Efforts To Confront It". Retrieved April 8, 2021.

- ^ Donald Altschiller (2005). Hate crimes: a reference handbook. Contemporary world issues (2nd ed.). ABC-CLIO. pp. 146. ISBN 9781851096244.

- ^ Joel Samaha (2005). Criminal justice (7th ed.). Cengage Learning. p. 44. ISBN 9780534645571.

- ^ a b Jacobs, James B.; Potter, Kimberly (2000). Hate crimes: criminal law & identity politics. Studies in Crime and Public Policy. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 134. ISBN 9780198032229.

When the FBI's 1993 hate crime statistics reported that whites comprised 20 percent of all hate crime victims, some advocacy groups questioned whether the hate crime laws were being perverted.12 Jill Tregor, executive director of the San Francisco-based Intergroup Clearinghouse, which provides legal and emotional counseling to hate crime victims, stated, "This is an abuse of what the hate crime laws were intended to cover."13 Tregor accused white hate crime victims of using the laws to enhance penalties against minorities, who already experience prejudice within the criminal justice system.14 Whites, generally sympathetic to the aspirations of minorities, may bristle at the suggestion that crimes motivated by blacks' racism against whites should be treated as a less virulent strain of hate crime, or not as hate crime at all. While no enacted hate crime law makes that distinction, a number of writers in prominent publications, likening hate crime laws to affirmative action for "protected groups," advocate the exclusion of racist crimes against whites from their coverage.15 This issue alone seems fraught with potential for social conflict and constitutional concerns.

- ^ "2019 hate crime statistics". Federal Bureau of Investigation. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

외부 링크

- 국가별, 명예훼손 방지 연맹을 통한 증오 범죄 법령 데이터베이스

- [증오 범죄 청구서 S. 1105], 증오 범죄 청구서에 대한 자세한 정보.

- "증오 범죄."옥스퍼드 도서목록 온라인: 범죄학