위치타, 캔자스 주

Wichita, Kansas위치타, 캔자스 주 | |

|---|---|

시군구 소재지 | |

| | |

| 닉네임: | |

미국 내 도시 경계 및 위치 | |

| 좌표:37°41~20°N 97°20′10″w/37.6889°N 97.33611°W좌표: 37°41°20°N 97°20°10°W / 37.6889°N 97.33611°W / [3] | |

| 나라 | 미국 |

| 주 | 캔자스. |

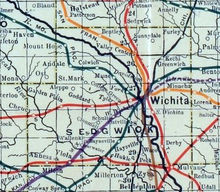

| 자치주 | 세지윅 |

| 설립. | 1868 |

| 인코퍼레이트 | 1870 |

| 이름: | 위치타족 |

| 정부 | |

| • 종류 | 협의회 매니저 |

| • 시장 | 브랜든 휘플(D) |

| • 시티 매니저 | 로버트 레이튼 |

| 지역 | |

| • 시군구 소재지 | 166.52 평방 밀리 (431.282 km) |

| • 토지 | 161.99 평방 밀리 (419.552 km) |

| • 물 | 4.53 평방 밀리 (11.732 km) |

| 승진 | 397m(1,440피트) |

| 인구. | |

| • 시군구 소재지 | 397,532 |

| • 견적 (표준)[7] | 395,699 |

| • 등급 | 미국 49위 캔자스 주 1위 |

| • 밀도 | 2,454.05/940 mi (947.52/km2) |

| • 메트로 | 647,919 (93위) |

| 디노미네임 | 위치탄 |

| 시간대 | UTC-6(CST) |

| • 여름 (DST) | UTC-5(CDT) |

| 우편 번호 | 67201~67221, 67223, 67226~67228, 67230, 67232, 67235, 67260, 67275~67278[9] |

| 지역번호 | 316 |

| FIPS 코드 | 20-79000 [3] |

| GNIS ID | 473862 [3] |

| 주요 공항 | 위치타 드와이트 D.아이젠하워 국제공항 |

| 주간 고속도로 | |

| 대중교통 | 위치타 교통 |

| 웹 사이트 | wichita.gov |

위치타(/wɪtʃtɔ/WICE-i-taw)[10]는 미국 캔자스주에서 가장 큰 도시이자 세지윅 [3]카운티의 군청 소재지입니다.2020년 인구 조사 기준으로 이 도시의 인구는 397,532명이다.[5][6]위치타 메트로 지역의 인구는 [8]2020년에 647,610명이었다.그것은 캔자스 주 [3]중남부의 아칸소 강에 위치해 있다.

위치타는 1860년대에 치솔름길의 교역소로 시작되었고 1870년에 도시로 편입되었다.텍사스에서 캔자스 철도로 북쪽으로 이동하는 소떼의 목적지가 되어 "코우타운"[11][12]이라는 별명을 얻었다.와이어트 얼프는 위치타에서 경찰로 1년 정도 근무한 후 닷지 시티로 갔다.

1920년대와 1930년대에 사업가들과 항공 기술자들은 위치타에 비크크래프트, 세스나, 스테어만 항공기를 포함한 항공기 제조 회사를 설립했다.그 도시는 "세계의 항공 수도"[13]로 알려진 항공기 생산 중심지가 되었다.Textron Aviation, Learjet, Airbus 및 Boeing/Spirit AeroSystems는 위치타에서 설계 및 제조 시설을 계속 운영하고 있으며, 도시는 여전히 미국 항공기 산업의 주요 중심지로 남아 있습니다.위치타 시내에는 맥코넬 공군 기지,[14][15] 제임스 자바라 대령 공항, 위치타 드와이트 D 공항 등이 있다. 캔자스에서 가장 큰 공항인 아이젠하워 내셔널 공항.

산업 중심지로서 위치타는 문화, 미디어, 무역의 지역 중심지이다.이곳에는 여러 대학, 대형 박물관, 극장, 공원, 쇼핑 센터 및 엔터테인먼트 장소가 있으며, 특히 Intrust Bank Arena와 Century II Performing Arts & Convention Center가 있습니다.이 도시의 올드 카우타운 박물관은 역사적 유물들을 보관하고 있으며 도시의 초기 역사를 전시하고 있다.위치타 주립 대학교는 이 주에서 세 번째로 큰 중고등학교 이후의 대학입니다.

역사

초기 역사

고고학적 증거에 따르면 아칸소강과 리틀 아칸소강의 합류점 부근에 [16]인류가 기원전 3000년에 살았던 것으로 보인다.1541년 탐험가 프란시스코 바스케스 데 코로나도가 이끄는 스페인 탐험대가 퀴비라, 즉 위치타족이 거주하는 지역을 발견했다.1750년대 오사게와의 갈등은 위치타 강을 [17]더 남쪽으로 몰았다.유럽인들이 이 지역에 정착하기 전에는 이 지역은 [18]키오와족의 영토였다.

19세기

처음에는 프랑스가 루이지애나의 일부라고 주장했고, 나중에 1803년 루이지애나 매입과 함께 미국에 의해 취득된 이곳은 1854년에 캔자스 준주의 일부가 되었고,[19][20] 1861년에 캔자스 주가 되었다.

위치타족은 1863년 미국 남북전쟁에서 남부군에 의해 인도 영토에 있는 그들의 땅에서 쫓겨나 리틀 [21][22][23]아칸소 강둑에 정착지를 세웠다.이 기간 동안 트레이더 제시 치솔름은 이 지역에 교역소를 설립했는데, 치솔름 [24]트레일로 알려지게 된 텍사스까지 이어지는 산책로를 따라 여러 곳 중 하나였다.전쟁 후 1867년 위치타족은 인디언 영토로 [21]돌아왔다.

1868년, 무역업자 제임스 R. 미드는 마을 회사를 설립한 투자자들 중 한 명이었고, 측량사 다리우스 멍거는 호텔, 커뮤니티 센터, 우체국 [25][26]역할을 하기 위해 통나무 구조물을 지었다.사업 기회가 지역 사냥꾼과 상인들을 끌어들였고, 새로운 정착지가 형성되기 시작했다.그 해 여름, 미드 등은 위치타 [22]부족의 이름을 따 위치타 타운 컴퍼니를 조직했다.1870년, 멍거와 독일 이민자 윌리엄 "네덜란드 빌" 그리펜슈타인은 도시의 [26]첫 번째 거리를 배치하는 명판을 만들었다.위치타는 1870년 [25]7월 21일에 정식으로 시가 되었다.

위치타는 치솔름 트레일에 위치하여 텍사스에서 북쪽으로 이동하는 가축들이 철도에 접근할 수 있게 되었고, 이는 미국 동부 [24][27]도시들의 시장으로 이어졌다.1872년 아치슨, 토페카, 싼타페 [28]철도가 이 도시에 도착했다.그 결과 위치타는 소몰이의 철로가 되어 "코우타운"[24][27]이라는 별명을 얻었다.아칸소 강 건너에 있는 델라노 마을은 술집, 위안소, 그리고 법 [29]집행의 부족으로 인해 목축업자들의 오락지가 되었다.이 지역은 폭력으로 유명했는데, 그 중 와이어트 얼프를 포함한 지역 경찰들이 [24][27]카우보이들을 강력하게 단속하기 시작했다.10년 중반 무렵, 소 거래는 서쪽으로 닷지 시티로 옮겨갔다.위치타는 [29]1880년에 델라노를 합병했다.

빠른 이민은 1880년대 후반에 투기적인 토지 붐을 일으켰고, 도시의 추가적인 확장을 촉진시켰다.결국 위치타 주립 대학교로 성장한 페어마운트 대학은 1886년에 개교했고, 결국 프렌즈 대학교가 된 가필드 대학은 [30][31]1887년에 개교했다.1890년까지 위치타는 거의 24,[32]000명의 인구를 가진 캔자스시티, 캔자스, 토페카에 이어 주에서 세 번째로 큰 도시가 되었다.그러나 호황 이후, 도시는 경제 불황에 빠졌고,[33] 많은 초기 정착민들이 파산했다.

20세기

1914년과 1915년에 인근 버틀러 카운티에서 석유와 천연가스의 매장량이 발견되었다.이것은 생산자들이 도시에 [34]정유소, 주유소, 그리고 본사를 설립하면서 위치타에 또 다른 경제 붐을 일으켰다.1917년까지 위치타에 5개의 정유 공장이 운영되었고 1920년대에 [35]또 다른 7개의 정유 공장이 건설되었다.미래의 석유 거물 아치볼드 더비와 프레드 C의 경력과 행운. Koch Industries가 되는 것을 설립한 Koch는 [34][36]둘 다 이 시기에 위치타에서 시작했다.

석유 붐으로 생긴 돈은 지역 기업가들이 초기 비행기 제조 산업에 투자할 수 있게 했다.1917년 클라이드 세스나는 위치타에 그의 세스나 혜성을 건설했는데, 위치타는 이 도시에 만들어진 최초의 항공기이다.1920년, 두 명의 지역 석유업자가 시카고 항공기 제작자 에밀 "매티" 레어드를 위치타에서 그의 디자인을 제작하기 위해 초청하여 스왈로우 에어플레인 회사를 설립하게 되었다.초기 스왈로우의 두 직원인 Lloyd Stearman과 Walter Beech는 각각 1926년에 Stearman Aircraft와 1932년에 Beechraft라는 두 개의 유명한 위치타 소재 회사를 설립했습니다.한편,[1] Cessna는 1927년 위치타에서 자신의 회사를 시작했다.이 [37][38]도시는 1929년 항공 상공회의소가 "세계의 항공 수도"로 명명할 정도로 산업의 중심지가 되었다.

이후 수십 년 동안 항공 및 항공기 제조업이 도시의 확장을 계속 추진했다.1934년 스테어먼의 위치타 시설은 보잉사의 일부가 되었고, 이 회사는 이 도시의 가장 큰 [39]고용주가 되었다.위치타 시립 공항의 초기 건설은 1935년에 시의 남동쪽에 완공되었다.제2차 세계대전 중에는 위치타 육군 비행장과 보잉 항공기 [40]1공장이 이곳에 있었다.이 도시는 전쟁 중 보잉 B-29 [41]폭격기의 주요 제조 중심지가 되면서 인구 폭발을 경험했다.1951년, 미 공군은 매코넬 공군 기지를 설립하기 위해 공항의 통제권을 인수할 계획을 발표했다.1954년까지 모든 비군사 항공 교통은 도시 [40]서쪽의 새로운 위치타 미드컨티넨트 공항으로 이동했다.1962년, 리어 제트사는 신공항 [42]근처에 공장을 가지고 문을 열었다.

19세기 후반과 20세기 내내, 몇몇 다른 유명한 사업과 브랜드들이 위치타에 기원을 두고 있었다.A. A. Hyde는 [43][44]1889년 위치타에 건강관리용품 제조업체 Mentholatum을 설립했다.스포츠 용품과 캠핑 용품 소매업자 콜먼은 1900년대 초에 [43][45]이 도시에서 시작했다.1921년 화이트 캐슬을 시작으로 1958년 피자헛을 포함한 1950년대와 1960년대에 많은 패스트푸드 체인점들이 위치타에서 시작되었다.1970년대와 1980년대에 도시는 의료와 의학 [43][46]연구의 지역 중심지가 되었다.

위치타는 역사상 여러 차례 국가적인 정치적 논란의 초점이 되어왔다.1900년, 유명한 금주 극단주의자인 캐리 네이션은 위치타가 캔자스의 금지령을 [43]시행하지 않는다는 것을 알고 위치타를 공격했다.도쿰 드러그 스토어 [47]농성은 1958년 인종차별 철폐를 요구하는 시위대와 함께 일어났다.1991년 수천 명의 낙태 반대 시위자들이 위치타 낙태 클리닉, 특히 조지 틸러의 [48]클리닉을 봉쇄하고 농성을 벌였다.틸러는 2009년 [49]위치타에서 스콧 로더에 의해 살해되었다.

21세기

1970년대의 완만한 시기를 제외하면 위치타는 21세기까지 [32]꾸준히 성장해 왔다.1990년대 후반과 2000년대, 시 정부와 지역 단체들은 위치타 시내와 [26][29][50]도시의 오래된 이웃들을 재개발하기 위해 협력하기 시작했다.인트라스트 뱅크 아레나는 [51]2010년에 시내에 문을 열었다.

보잉은 [52]위치타에서 2014년에 운영을 종료했다.하지만 스피릿 에어로 시스템즈, 에어버스 등 위치타에 [25][53]시설을 유지하고 있는 다른 회사들과 함께 이 도시는 항공기 제조의 국가 중심지로 남아 있다.

위치타 미드컨티넨탈 공항은 공식적으로 위치타 드와이트 D로 개명되었다.2015년 [54]캔자스 출신이자 미국 대통령에 이어 아이젠하워 내셔널 공항.

지리

위치타는 캔자스 중남부에 있으며 35번 주간 고속도로와 54번 [55]국도의 교차로에 있다.미국 중서부의 일부로서 오클라호마시티에서 북쪽으로 157mi(253km), 캔자스시티에서 남서쪽으로 181mi(291km),[56] 덴버에서 남동쪽으로 439mi(707km) 떨어져 있다.

이 도시는 그레이트 [57]플레인스의 웰링턴-맥퍼슨 저지대에 있는 플린트 힐스의 서쪽 가장자리 근처에 있는 아칸소 강에 있습니다.이 지역의 지형은 아칸소 강 계곡의 넓은 충적 평야와 양쪽의 [58][59]고지대까지 완만한 경사가 특징입니다.

아칸소 강은 위치타를 지나 남동쪽으로 굽이치는 코스를 따라 도시를 대략 양분하고 있다.그 진로를 따라 몇 개의 지류가 합류하며, 모두 대체로 남쪽으로 흐른다.가장 큰 강은 북쪽에서 도시로 들어와 시내 서쪽에서 아칸소 강으로 합류하는 리틀 아칸소 강이다.더 동쪽에는 도시의 가장 남쪽 부분에서 아칸소 강에 합류하는 치솔름 크리크가 있습니다.치솔름 강의 지류들은 도시의 동쪽 절반의 많은 부분을 배수한다; 이것들은 더 남쪽의 집섬 크릭뿐만 아니라 강의 서쪽, 중간, 그리고 이스트 포크들을 포함한다.석고강은 그 자체의 지류인 드라이 크릭에 의해 공급된다.아칸소 강의 지류 중 두 개는 그 흐름의 서쪽에 있습니다; 동쪽에서 서쪽으로, 이것들은 빅 슬러프 크리크와 카우스킨 크리크입니다.둘 다 도시의 서쪽을 통해 남쪽으로 달린다.호두강의 지류인 포마일 크리크는 도시의 [60]극동부를 통해 남쪽으로 흐른다.

미국 인구조사국에 따르면, 이 도시의 총 면적은 163.59 평방 미(4232.70 km)이며, 이 중 4.30 평방 미(11.142 km)는 [61]물로 덮여 있다.

위치타 수도권의 핵심으로서 도시는 교외로 둘러싸여 있다.북쪽은 위치타와 국경을 맞대고 있으며 서쪽에서 동쪽으로 밸리 센터, 파크 시티, 케치, 벨 에어 등이 있습니다.동쪽 중앙 위치타에 둘러싸인 곳은 이스트버러입니다.그 도시의 동쪽과 인접해 있는 곳은 앤도버이다.맥코넬 공군 기지는 도시의 남동쪽 끝에 있다.남쪽, 동쪽에서 서쪽으로 더비와 헤이즈빌이 있다.고다드와 옥수수는 각각 [62]서쪽과 북서쪽으로 위치타와 국경을 접하고 있다.

기후.

위치타는 습한 아열대 기후대(Köppen Cfa)에 속하며, 일반적으로 덥고 습한 여름과 춥고 건조한 겨울을 경험합니다.대평원에 위치한 위치타는 산이나 큰 수역 같은 큰 온화한 영향과는 거리가 먼 혹독한 날씨를 자주 경험하고 봄과 여름에 천둥번개가 자주 친다.이것들은 때때로 큰 우박과 번개를 동반한다.특히 파괴적인 것은 1965년 9월 캔자스주 앤도버 토네이도 발생 당시와 1999년 [63][64][65]5월 오클라호마 토네이도 발생 당시 등 역사상 여러 차례 위치타 지역을 강타했다.겨울은 춥고 건조하다; 위치타는 캐나다와 멕시코만의 중간쯤에 있기 때문에, 추운 계절과 따뜻한 계절이 똑같이 자주 발생한다.멕시코만의 따뜻한 기단은 한겨울의 온도를 50~60도(°F)까지 상승시킬 수 있으며, 북극의 찬 기단은 때때로 온도를 0°F 이하로 떨어뜨릴 수 있다.이 도시의 풍속은 평균 21km/[66]h(13mph)이다.평균적으로, 1월은 가장 추운 달이고, 7월은 가장 덥고, 5월은 가장 습한 달이다.

도시의 평균 기온은 57.7°F(14.3°[67]C)입니다.1년 동안 월평균 기온은 1월에 33.2°F(0.7°C)에서 7월에 81.5°F(27.5°C)까지 다양합니다.고온은 연평균 65일, 100°F(38°C)는 연평균 12일입니다.최저 온도는 연평균 7.7일 동안 10°F(-12°C) 이하로 떨어집니다.위치타에서 기록된 가장 더운 온도는 1936년에 114°F(46°C)였고, 기록된 가장 추운 온도는 1899년 2월 12일에 -22°F(-30°C)였습니다.최저 -17°F(-27°C)와 최고 111°F(44°C)의 판독치는 [68]각각 2021년 2월 16일과 2012년 7월 29~30일에 발생했다.위치타에는 1년에 평균 약 34.31인치(871mm)의 비가 내립니다.이 강수량은 대부분 따뜻한 달에 내립니다.또한 87일간 측정 가능한 강수량을 경험합니다.평균 상대 습도는 아침에는 80%, [66]저녁에는 49%입니다.연평균 적설량은 12.7인치(32cm)이다.측정 가능한 폭설은 연평균 9일 동안 발생하며, 그 중 4일에는 최소 1인치의 눈이 내린다.1인치 이상의 적설량은 [67]연평균 12일 정도 발생한다.평균 영하의 기간은 10월 25일부터 4월 [68]9일까지입니다.

| 캔자스주 위치타의 기후 데이터(1991–2020년 기준,[a] 극단 1888–현재)[b] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 달 | 1월 | 2월 | 마루 | 에이프릴 | 그럴지도 모른다 | 준 | 줄 | 8월 | 9월 | 10월 | 11월 | 12월 | 연도 |

| 높은 °F(°C)를 기록하십시오. | 75 (24) | 87 (31) | 92 (33) | 98 (37) | 102 (39) | 110 (43) | 113 (45) | 114 (46) | 108 (42) | 97 (36) | 86 (30) | 83 (28) | 114 (46) |

| 평균 최대 °F(°C) | 65.8 (18.8) | 71.6 (22.0) | 79.9 (26.6) | 85.3 (29.6) | 92.0 (33.3) | 98.4 (36.9) | 103.7 (39.8) | 102.2 (39.0) | 97.3 (36.3) | 89.0 (31.7) | 75.5 (24.2) | 65.3 (18.5) | 104.9 (40.5) |

| 평균 높은 °F(°C) | 43.9 (6.6) | 48.9 (9.4) | 59.1 (15.1) | 68.3 (20.2) | 77.5 (25.3) | 87.9 (31.1) | 92.6 (33.7) | 91.0 (32.8) | 83.3 (28.5) | 70.8 (21.6) | 57.0 (13.9) | 45.8 (7.7) | 68.8 (20.4) |

| 일평균 °F(°C) | 33.2 (0.7) | 37.6 (3.1) | 47.4 (8.6) | 56.5 (13.6) | 66.7 (19.3) | 76.9 (24.9) | 81.5 (27.5) | 79.9 (26.6) | 71.7 (22.1) | 59.0 (15.0) | 45.8 (7.7) | 35.6 (2.0) | 57.7 (14.3) |

| 평균 낮은 °F(°C) | 22.5 (−5.3) | 26.3 (−3.2) | 35.7 (2.1) | 44.8 (7.1) | 55.9 (13.3) | 65.9 (18.8) | 70.4 (21.3) | 68.8 (20.4) | 60.1 (15.6) | 47.2 (8.4) | 34.7 (1.5) | 25.4 (−3.7) | 46.5 (8.1) |

| 평균 최소 °F(°C) | 5.1 (−14.9) | 8.4 (−13.1) | 17.1 (−8.3) | 28.2 (−2.1) | 40.5 (4.7) | 53.9 (12.2) | 61.4 (16.3) | 59.3 (15.2) | 44.6 (7.0) | 29.7 (−1.3) | 17.9 (−7.8) | 8.4 (−13.1) | 1.0 (−17.2) |

| 낮은 °F(°C)를 기록하십시오. | −15 (−26) | −22 (−30) | −3 (−19) | 15 (−9) | 27 (−3) | 43 (6) | 51 (11) | 45 (7) | 31 (−1) | 14 (−10) | 1 (−17) | −16 (−27) | −22 (−30) |

| 평균 강수량(mm) | 0.85 (22) | 1.20 (30) | 2.30 (58) | 3.10 (79) | 5.17 (131) | 4.93 (125) | 3.98 (101) | 4.30 (109) | 3.05 (77) | 2.85 (72) | 1.36 (35) | 1.22 (31) | 34.31 (871) |

| 평균 적설량(cm) | 2.7 (6.9) | 3.6 (9.1) | 2.1 (5.3) | 0.2 (0.51) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.2 (0.51) | 0.8 (2.0) | 3.1 (7.9) | 12.7 (32) |

| 평균강수일수( 0 0.01인치) | 4.8 | 5.3 | 7.4 | 8.3 | 11.3 | 9.5 | 8.3 | 8.2 | 6.9 | 6.6 | 5.1 | 5.4 | 87.1 |

| 평균 강설일수 (0.1인치 이하) | 2.7 | 2.2 | 1.0 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 2.2 | 9.2 |

| 평균 상대습도(%) | 69.9 | 68.3 | 63.8 | 62.8 | 67.0 | 64.3 | 58.9 | 61.1 | 66.8 | 65.1 | 70.0 | 71.7 | 65.8 |

| 월평균 일조시간 | 190.9 | 186.4 | 230.4 | 257.8 | 289.8 | 305.0 | 342.1 | 309.2 | 245.6 | 226.3 | 170.2 | 168.7 | 2,922.4 |

| 일조 가능률 | 62 | 62 | 62 | 65 | 66 | 69 | 76 | 73 | 66 | 65 | 56 | 57 | 66 |

| 평균 자외선 지수 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 6 |

| 출처: 국립 기상국(상대습도 및 태양 1961–1990);[68][67][69] | |||||||||||||

인근 지역

위치타에는 몇몇 인정된 지역과 이웃이 있다.시내 지역은 일반적으로 아칸소 강 동쪽, 워싱턴 스트리트 서쪽, 켈로그 북쪽, 13번가 남쪽인 것으로 여겨진다.그것은 센츄리 II, 가비 센터, 에픽 센터와 같은 랜드마크를 포함하고 있다.올드타운은 시내의 일부이기도 합니다.이 50에이커(0.20km2) 지역에는 나이트클럽, 바, 레스토랑, 영화관, 상점, 아파트와 콘도미니엄이 밀집해 있으며, 이들 중 많은 곳은 역사적인 창고형 공간을 사용하고 있습니다.

위치타의 눈에 띄는 두 주거 지역은 리버사이드와 칼리지 힐이다.리버사이드(Riverside)는 도심에서 북서쪽으로 아칸소 강을 가로지르며 120에이커(0.49km2)의 리버사이드 [70]공원을 둘러싸고 있습니다.College Hill은 시내의 동쪽, 위치타 주립대학교의 남쪽에 있습니다.이곳은 서쪽의 델라노,[71] 북쪽의 미드타운과 함께 더 역사적인 동네 중 하나이다.

위치타 남동부(특히 보잉, 세스나, 비치 항공기 공장 근처)에서 개발된 다른 역사적인 4개 지역은 전쟁 공장 직원들을 지원하기 위해 미국 정부가 지원한 2차 세계대전 임시 주택 개발의 몇 안 되는 사례 중 하나이다.Beechwood(현재 대부분 철거), Oaklawn, Hilltop(이 도시에서 가장 밀도가 높은 지역), 그리고 거대한 Planeview(30개 이상의 언어가 사용되는 곳)는 모두 도시 인구의 약 5분의 1이 절정에 있습니다.비록 임시 주택으로 설계되었지만, 21세기까지 모두 거주한 채 남아 있었고, 대부분은 저소득층 [72][73][74][75][76]지역이 되었다.

인구 통계

| 과거 인구 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 인구 조사 | Pop. | %± | |

| 1870 | 689 | — | |

| 1880 | 4,911 | 612.8% | |

| 1890 | 23,853 | 385.7% | |

| 1900 | 24,671 | 3.4% | |

| 1910 | 52,450 | 112.6% | |

| 1920 | 72,217 | 37.7% | |

| 1930 | 111,110 | 53.9% | |

| 1940 | 114,966 | 3.5% | |

| 1950 | 168,279 | 46.4% | |

| 1960 | 254,698 | 51.4% | |

| 1970 | 276,554 | 8.6% | |

| 1980 | 279,272 | 1.0% | |

| 1990 | 304,011 | 8.9% | |

| 2000 | 344,284 | 13.2% | |

| 2010 | 382,368 | 11.1% | |

| 2020 | 397,532 | 4.0% | |

| 2021년(추정) | 395,699 | [7] | −0.5% |

| 미국의 10년마다 실시하는[77] 인구 조사 2010년[6] ~ 2010년 | |||

2020년 [6]인구 조사에 따르면 위치타는 캔자스 주에서 가장 큰 도시이자 미국에서 49번째로 큰 도시입니다.이곳은 다른 주요 [78]도시보다 인종적으로 미국의 나머지 지역과 더 유사하다.

2010년 인구 조사

2010년 인구 조사 기준으로 이 도시에는 382,368명, 151,818가구, 94,862가구가 거주하고 있다.인구밀도는 평방마일(889.9/km2)당 2,304.8명이었다.167,310채의 주택 밀도는 평방 마일(475.9/km2)당 평균 1,022.1채였다.이 도시의 인종 구성은 백인 71.9%, 흑인 11.5%, 아시아인 4.8%, 아메리칸 인디언 1.2%, 태평양 섬 사람 0.1%, 타 인종 6.2%, 2인 이상 4.3%였다.히스패닉계와 라틴계 인종은 인구의 15.3%였다.[79]

15만1818가구 중 18세 미만 자녀가 33.4%, 함께 사는 부부가 44.1%, 아내가 없는 남성 가구주가 5.2%, 남편이 없는 여성 가구주가 13.1%, 가족이 아닌 가구가 37.5%였다.전체 가구의 약 31.1%가 개인이고, 9.1%는 65세 이상의 독거노인이었다.평균 가구 수는 2.48명이었고 평균 가족 수는 3.14명이었다.[79]

도시의 중간 연령은 33.9세, 주민의 26.6%가 18세 미만, 10.1%가 18세에서 24세, 26.9%가 25세에서 44세, 24.9%가 45세에서 64세, 11.5%가 65세 이상이었다.이 도시의 성별 구성은 남성 49.3%, 여성 [79]50.7%였다.

도시의 가구당 중간 소득은 44,477달러였고, 가족의 소득은 57,088달러였다.남성의 중간 소득은 42,783달러인데 반해 여성은 32,155달러였다.도시의 1인당 소득은 24,517달러였다.18세 미만은 22.5%, 65세 [79]이상은 9.9%를 포함해 약 12.1%, 인구의 15.8%가 빈곤선을 밑돌았다.

수도권

위치타는 위치타 메트로폴리탄 통계 지역(MSA)과 위치타-윈필드 복합 통계 지역(CSA)[80][81]의 주요 도시입니다.위치타 MSA는 Sedgwick, Butler, Harvey 및 Sumner 카운티에 걸쳐 있으며 2010년 현재 인구는 623,061명으로 미국에서 [80][82][83]84번째로 큰 MSA이다.

더 큰 위치타-윈필드 CSA는 또한 카울리 카운티를 포함하며, 2013년 기준으로 추정 인구는 673,[84]598명이다.인근 리노 카운티는 위치타 MSA나 위치타 윈필드 CSA의 일부가 아니지만 이를 포함하면 2010년 [85]기준으로 64,511명의 인구가 추가될 것이다.

경제.

이곳은 화이트 캐슬과 [86][87]피자헛과 같은 유명한 식당들의 발상지입니다.RSM Marketing Services와 위치타 Consumer Research Center가 실시한 캔자스 소재 유명 브랜드 조사에서는 Koch, Coleman, Cessna, Pizza Hut, Beechcraft, Freddy's 등 캔자스 소재 상위 25개 브랜드의 대부분이 위치타에 [88]소재하고 있는 것으로 나타났습니다.

위치타의 주요 산업 부문은 제조업으로, 2003년에는 지역 고용의 21.6%를 차지했다.항공기 제조는 오랫동안 지역 경제를 지배해 왔으며, 지역 전체의 경제 건전성에 영향을 미칠 정도로 중요한 역할을 한다. 주정부는 항공기 [89]제조사에 세금 감면 및 기타 인센티브를 제공한다.

의료는 위치타에서 두 번째로 큰 산업으로 약 28,000명의 직원을 고용하고 있습니다.의료 수요는 경제에 관계없이 상당히 일정하기 때문에, 이 분야는 2000년대 초반의 다른 산업에 영향을 미쳤던 것과 같은 압력의 대상이 되지 않았다.캔자스 척추 병원은 2004년에 문을 열었고 웨슬리 메디컬 [90]센터의 중환자실도 문을 열었다.2010년 7월, 캔자스주 최대의 의료 서비스 프로바이더인 Via Christi Health는 위치타 북서부 지역에 서비스를 제공하는 병원을 개업했습니다.세인트 크리스티 병원 경유.테레사는 위치타 지역 사회에 봉사하는 [91]이 시스템의 다섯 번째 병원이다.2016년, Wesley Healthcare는 위치타 [92]지역의 최초이자 유일한 어린이 병원인 Wesley Children's Hospital을 열었다.

20세기 초 캔자스 주 버틀러 카운티의 석유 붐 덕분에 위치타는 수십 개의 석유 탐사 회사와 지원 기업이 있는 주요 석유 도시가 되었습니다.이들 중 가장 유명한 것은 오늘날 세계적인 천연자원 복합기업인 코흐 산업이다.이 도시는 또한 1988년에 코스트 코퍼레이션에 의해 인수된 옛 더비 석유 회사의 본사이기도 했다.위치타는 캔자스 스트롱과 캔자스 독립 석유 가스 협회의 본거지이다.

코흐 인더스트리와 카길은 [93]모두 위치타에 본사 시설을 운영하고 있다.Koch Industries의 주요 글로벌 기업 본사는 위치타 북동부의 대형 오피스 타워 단지 내에 있습니다.한때 국내 3위의 쇠고기 생산업체였던 카길 미트 솔루션 사업부는 시내에 본사를 두고 있다.위치타에 본사를 둔 다른 회사로는 롤러코스터 제조업체인 챈스 모건, 미식 식품 소매업체 딘 & 들루카, 재생 에너지 회사인 얼터너티브 에너지 솔루션, 캠핑 및 야외 레크리에이션 용품 제조업체인 콜먼 컴퍼니가 있습니다.에어 미드웨스트는 미국 최초의 공식 인증된 "통근자" 항공사로 위치타에 설립되어 본사를 두고 있으며 2008년 [94]해체되기 전에 국내 8위의 지역 항공사로 발전했다.

2013년 기준으로 16세 이상 인구의 68.2%가 노동력, 0.6%가 군대, 67.6%가 민간 노동력, 61.2%가 고용, 6.4%가 실업자였다.고용된 민간 노동력의 직업 구성은 경영, 비즈니스, 과학, 예술 33.3%, 판매 및 사무 25.1%, 서비스 17.2%, 생산, 운송, 자재 이동 14.0%, 천연자원, 건설, 유지 10.4%였다.민간 노동력의 고용 비율이 가장 높은 3개 업종은 교육 서비스, 의료, 사회 지원(22.3%), 제조업(19.2%), 소매업(11.0%)[79]이었다.

위치타의 생활비는 평균 이하입니다.미국 평균 100에 비해, 위치타의 생활비는 84.[95]0입니다.2013년 현재, 도시의 중앙 주택 가치는 117,500달러, 주택 담보 대출이 있는 주택은 1,194달러, 주택 담보 대출이 없는 주택은 419달러, [79]총 임대료는 690달러이다.

위치타는 미국 언론에서 저렴하고 살기 좋은 곳으로 전국적인 명성을 가지고 있다.2006년 7월, CNN/Money and Money는 위치타를 미국에서 [96]가장 살기 좋은 10대 대도시에 9위로 선정했습니다.2008년 MSN 부동산은 위치타를 가장 저렴한 [97]도시 목록에서 1위로 선정했습니다.U. News & World Report는 2019년 "가장 살기 좋은 곳" 조사에서 위치타를 125개 미국 [98]도시 중 79위로 선정했으며 위치타에서의 폭력 범죄가 지난 몇 [99]년 동안 증가했다고 지적했다.2019 KIDS COUNT Data Book에서 캔자스는 매년 "전체 어린이 웰빙에 관한 주 순위"에서 50개 주 중 15위를 차지했습니다.하지만, 주 정부는 일반적으로 국가보다 아동 투옥률이 훨씬 높고,[100] 그들의 집에서 아이들을 데려가는 주 정부의 비율이 더 높습니다.

항공기 제조

20세기 초에서 후반까지, 클라이드 세스나, 에밀 매튜 "매티" 레어드, 로이드 스테어만, 월터 비치, 알 무니, 빌 리어와 같은 항공기 선구자들이 항공기 제조 사업을 시작했고, 이로 인해 위치타는 항공기 생산 대수의 전국 선두 도시가 되었다.항공기 회사 E. M. Laird Aviation Company (국내 최초의 성공적인 상업용 비행기 제조사), Travel Air (Beech, Stearman, Cessna, Beechcraft, and Mooney)는 모두 1920년에서 [13]1932년 사이에 위치타에 설립되었습니다.1931년 보잉사는 (워싱턴주 시애틀의) 스테어먼을 흡수하여 "보잉-위치타"를 만들었고, 이는 결국 캔자스주의 최대 [14][101]고용주로 성장하였다.

현재 Cessna Aircraft Co.(세계 최대 항공기 제조업체)와 Beechcraft는 2014년 Textron Aviation과 합병하여 위치타에 본사를 두고 있으며, Learjet 및 보잉의 주요 서브어셈블리 공급업체인 Spirit Aero Systems와 함께 있습니다.Airbus는 위치타에 직원을 두고 있으며 봄바디어(리어젯의 모회사)도 위치타에 다른 부서를 두고 있습니다.위치타 MSA에서는 50개 이상의 다른 항공 사업체들이 운영되고 있으며, 지역 항공기 제조사에 대한 수십 개의 공급업체와 하청업체들도 운영되고 있습니다.1916년 [14][15][102][103]클라이드 세스나의 첫 번째 위치타 제작 이후 위치타와 그 회사들은 약 25만 대의 항공기를 제조했다.

2000년대 초, 국내외의 불황과 2001년 9월 11일의 여파가 겹쳐 위치타 내외의 항공 부문을 침체시켰다.새로운 항공기 주문이 급감하면서 위치타의 5대 항공기 제조사인 보잉, 세스나 항공기, 봄바디어 리어젯, 호커 비크크래프트, 레이시온 항공기가 탄생했다.2001년부터 2004년까지 총 15,000개의 작업을 삭감했습니다.이에 대응하여, 이들 회사는 기업 및 기업 [90]사용자들의 관심을 끌기 위해 중소형 비행기 개발에 착수했다.2007년 위치타는 단일 엔진 경비행기에서 세계에서 가장 빠른 민간 제트기까지 977대의 항공기를 제작했다. 그 해 미국에서 생산된 민간 항공기의 5분의 1과 다수의 소형 [15][102][103][104]군용기를 제작했다.2012년 초, 보잉은 위치타 공장을 [105]2013년 말까지 폐쇄할 것이라고 발표했고, 이는 Spirit Aerosystems의 공장 개설을 위한 길을 열었다.

예술과 문화

위치타는 유럽계 미국인, 블루칼라 산업 및 시골 취향이 지배하고 있지만, 다양한 수준의 클래식 예술과 음악, 국내외 문화(히스패닉, 아프리카계 미국인, 아메리카 원주민, 아시아, 영국 및 아일랜드 문화의 영향과 활동이 두드러짐)와 아방가르드 컬쳐를 수용하고 있다.알 액티비티

예술

위치타는 [citation needed]캔자스의 문화 센터로 여러 미술관과 공연 예술 단체들이 모여 있습니다.위치타 미술관은 캔자스주에서 가장 큰 미술관으로 7,000여 점의 작품을 영구 [106]소장하고 있다.위치타 주립대학의 울리히 미술관은 6,300여 점의 작품을 [107]영구 소장하고 있는 근현대 미술관이다.

구시가지, 델라노, 사우스커머스 거리에 소규모 미술관이 밀집해 있다.이들 갤러리는 매월 마지막 주 금요일 저녁에 무료로 관광지를 둘러보는 파이널 프라이데이 갤러리 크롤 이벤트를 시작했다.더 큰 박물관들이 참여하기 시작했고 시작 직후인 금요일에는 늦게까지 문을 열기 시작했다.

음악

위치타는 캔자스 중심부의 음악 중심지로 세계 각지의 주요 배우들을 불러 모아 그 지역의 다양한 콘서트 홀, 경기장, 경기장에서 공연하고 있다.대부분의 주요 로큰롤과 팝 음악 스타들, 그리고 사실상 모든 컨트리 음악 스타들이 그들의 경력 동안 그곳에서 공연을 한다.

음악극장 위치타, 위치타 그랜드 오페라,[108] 위치타 심포니 오케스트라가 시내에 있는 센츄리 II 컨벤션 홀에서 정기적으로 공연합니다.콘서트는 위치타의 두 개의 [108][109]가장 큰 대학에서 전국적으로 유명한 음악 학교들에 의해 정기적으로 공연된다.

1922년에 지어진 고전 영화 궁전인 오르페움 극장은 소규모 공연을 위한 도심 공연장 역할을 한다.1960년에 지어진 특별 행사 시설인 코틸리온은 음악 공연장과 비슷한 목적을 가지고 있다.

이벤트

위치타 강 축제는 1972년부터 시내와 구시가지에서 열리고 있다.매년 [110]약 37만 명의 방문객을 위한 행사, 음악 오락, 스포츠 행사, 여행 전시, 문화 및 역사 활동, 연극, 인터랙티브 어린이 행사, 벼룩시장, 하천 행사, 퍼레이드, 블록 파티, 푸드 코트, 불꽃놀이, 기념품 등이 마련되어 있다.2011년에는 이전 축제 때 내린 비 때문에 5월에서 6월로 옮겨졌다.위치타 강 축제는 2016년과 [111]2018년에 기록적인 숫자를 기록하는 등 엄청난 성장을 보였다.그 성장의 대부분은 축제에서 [112]매력적인 음악 행위 덕분이다.다가오는 2021 위치타 강 축제는 2021년 6월 4일부터 12일까지 열릴 예정이다.

매년 봄에 열리는 위치타 블랙 아트 페스티벌은 위치타의 큰 흑인 사회의 예술, 공예, 그리고 창의성을 축하한다.그것은 보통 중앙-동북 위치타에서 열린다.18일 행사와 퍼레이드 또한 일반적인 연례 행사이다.

위치타 주립 대학의 국제 학생회는 WSU 캠퍼스에서 매년 열리는 국제 문화 전시회와 음식 축제를 개최하여 일반 대중들에게 저렴한 시식을 제공하고 있습니다.

매년 하나 이상의 대규모 르네상스 박람회가 열리고 있는데, 여기에는 SCA의 "칼론티르 왕국"과 연계된 "렌페어"가 포함된다.박람회는 보통 세지윅 카운티 파크나 뉴먼 대학에서 하루에서 일주일까지 다양합니다.

위치타 공립도서관의 아카데미상 단편 프로그램은 아카데미상 후보에 오른 단편 영화들 중 할리우드 이외에서 가장 오래되고 완전한 무료 공개 상영이라고 한다.아카데미 시상식이 열리기 직전인 늦겨울에는 모든 후보에 오른 다큐멘터리, 실사, 애니메이션 반바지를 포함한 영화들이 도서관, 지역 극장 및 위치타 주변의 다른 장소에서 무료로 상영됩니다.위치타의 전 하원의원인 댄 글릭먼 전 영화협회 회장이 이 행사의 명예회장을 맡았고, 몇몇 영화 제작자들이 참석해서 [113][114][115][116][117][118]관객들과 함께 방문했다.

탈그라스 영화제는 2003년부터 위치타 시내에서 열리고 있다.매년 10월 3일 동안 전 세계에서 100편이 넘는 독립 장편과 단편 영화를 끌어당긴다.연예계의 유명 인사들이 이 [119]축제에 참석했다.

위치타 지역에서는 에어쇼, 플라이인, 에어 레이스, 항공 회의, 전시회, 무역 박람회를 포함한 항공 관련 행사가 흔하다.이 도시의 두 개의 주요 에어쇼는 일반적으로 교대로 열리며, 시가 후원하는 민간 위치타 비행[120] 축제(원래 "캔자스 비행 축제")와 군대가 후원하는 맥코넬 공군 기지 오픈 하우스와 에어쇼이다.[121]둘 다 유명한 공연과 수백만 달러의 항공기 전시가 있는 대형 지역 에어쇼입니다(많은 위치타 제작 항공기 포함).또한 수많은 지역, 지역 및 국가 항공 기관이 위치타 지역에서 불규칙한 일정으로 비행, 회의, 전시회 및 무역 박람회를 개최합니다.

관심장소

과학, 문화, 지역 역사에 관한 박물관과 랜드마크가 도시 곳곳에 위치해 있다.탐험 장소 과학 및 발견 센터, 미드 아메리카 올-인디언 센터, 올드 카우타운 생활 역사 박물관, 플레인즈 동상과 플레인즈 인디언들의 일상을 강조하는 관련 전시물을 포함한 몇몇 건물들이 시내 서쪽의 아칸소 강을 따라 놓여있다.위치타 시내에 있는 위치타-세그윅 카운티 역사박물관은 1892년에 지어진 원래 위치타 시청을 차지하고 있습니다.박물관에는 1865년부터 현재까지 [122]위치타와 세지윅 카운티의 이야기를 전하는 유물들이 소장되어 있다.근처에는 1913년 세지윅 카운티 기념관과 군인 및 선원 기념비가 있습니다.시내 동쪽에는 세계 보물 박물관과 철도 중심의 대초원 교통 박물관이 있습니다.Coleman Factory 아울렛과 박물관은 235 N St.에 있었다.프란시스 거리이며 2018년에 문을 닫을 때까지 콜맨 랜턴의 본거지였다.[123]위치타 주립 대학교는 로웰 D를 주최한다. 홈즈 인류학 박물관.캔자스 항공 박물관은 구 시립 공항의 터미널 및 행정 건물에 있으며, 매코넬 공군 기지와 인접한 위치타 남동부에 있습니다.오리지널 피자헛 박물관도 위치타 주립대 캠퍼스에 있어 피자를 좋아하는 사람들과 팬들이 방문할 수 있습니다.

보타니카, 위치타 가든 역시 아칸소 강을 따라 나비가든과 수상 경력에 빛나는 샐리 스톤 센세이션 [citation needed]가든을 포함한 24개의 테마 정원이 있다.위치타 북서부에 있는 세지윅 카운티 동물원은 캔자스 주에서 가장 인기 있는 야외 관광 명소이며 500여 [124]종을 대표하는 2,500마리 이상의 동물들이 살고 있습니다.동물원은 세지윅 카운티 공원과 세지윅 카운티 확장 수목원 옆에 있다.

Intraust Bank Arena는 이 도시의 주요 이벤트 장소로, 22개의 스위트룸, 2개의 파티 스위트룸, 40개의 로지박스 및 300개가 넘는 프리미엄 시트(총 수용 [125]가능 인원 15,000명 이상)를 갖추고 있습니다.위치타 한복판에 있는 이 아레나는 2010년 [126]1월에 개장했습니다.

시내의 바로 동쪽에 위치한 것은 도시의 유흥가인 올드타운이다.1990년대 초 개발자들은 이곳을 오래된 창고지구에서 주거공간, 나이트클럽, 레스토랑,[127] 호텔, 박물관을 갖춘 복합지역으로 탈바꿈시켰다.

올드타운이 될 예정이었던 더글러스 625번지에 있는 무디스 스키드로 비너리는 1960년대 위치타에서 가장 유명한 곳 중 하나였다.그곳은 전국적으로 수정헌법[128] 제1조에 따른 투쟁의 현장이었고 1966년 앨런 긴스버그가 그의 긴 시 "위치타 볼텍스 수트"를 처음 읽었던 곳 (마법극장 볼텍스 아트 갤러리로 이름이 바뀌었다.

위치타에는 두 개의 주요 실내 쇼핑몰이 있습니다.Simon Property Group이 관리하는 Towne East Square와 Towne West Square.타운이스트에는 4개의 앵커 스토어가 있으며 100명 이상의 세입자가 있다.2019년 [129]압류된 타운 웨스트 스퀘어는 2021년 현재도 운영 중이다.가장 오래된 쇼핑몰인 위치타 몰은 수년 동안 대부분 폐허가 되어 있었지만, 그 이후로 사무실 [130]공간으로 바뀌었습니다.도시의 북동쪽에 위치한 브래들리 페어(재즈 콘서트와 예술 축제를 주최하는)와 북서쪽에 위치한 뉴 마켓 스퀘어 등 두 개의 대형 야외 쇼핑 센터도 있습니다.각 시설은 수 에이커에 50개 이상의 점포로 구성되어 있습니다.

1936년 위치타 우체국에는 캔자스 주의 리처드 헤인즈가 그린 캔자스 파밍과 워드 록우드가 그린 파이오니어라는 두 개의 캔자스 유화 벽화가 있었다.벽화는 1934년부터 1943년까지 미국 재무부의 미술과(Fine Arts Section)를 통해 제작되었다.우체국 건물은 401 N에 연방법원이 되었다.마켓 스트리트와 벽화는 [131]로비에 전시되어 있습니다.

위치타에는 리버사이드 파크, 칼리지 힐 파크, 맥아담스 파크와 같은 많은 공원과 레크리에이션 지역도 있습니다.

라이브러리

위치타 공립 도서관은 시립 도서관 시스템으로 현재 중심 시설, 델라노에 있는 고급 학습 도서관 및 [132]시 주변의 다른 지역에 있는 6개의 분관으로 구성되어 있습니다.이 도서관은 특별 행사, 기술 훈련 교실, 성인,[133] 어린이, 가족을 위한 프로그램 등 대중을 위한 몇 가지 무료 프로그램을 운영하고 있습니다.2009년 현재 보유 도서 수는 130만 권 이상이며 [134]총 220만 건이다.

위치타는 글렌 캠벨의 동명 앨범 "위치타 라인맨", 숀 콜빈의 "위치타 스카이라인", 행크 스노우의 "I've Be Everywhere", 화이트 스트라이프의 "Seven Nation Army"에 언급되어 있다.재즈 뮤지션인 팻 메테니와 라일 메이스는 1981년에 "As Falls Wichita, So Falls Wichita Falls"라는 제목의 콜라보레이션 앨범을 발매했는데, 이 앨범에는 21분도 안 되는 타이틀곡이 포함되어 있다.이 제목은 캔자스주 위치타와 텍사스주 위치타 폴스를 모두 지칭한다.

그 도시는 다양한 문학 작품의 배경이 되어 왔다.앨런 긴스버그는 그의 시 '위치타 볼텍스 수트라'에서 위치타 방문에 대해 썼고, 필립 글래스는 그 후에 그 방문을 위해 피아노 독주곡을 썼다.긴스버그는 샌프란시스코 비트 [135]문화에 영향을 준 "위치타 그룹" 중 한 명인 작가 찰스 플라이멜에 의해 위치타로 데려왔다.수상 경력에 빛나는 Roger Rueff가 쓴 연극 Hospetity Suite는 1999년 각색 영화인 The Big [136]Kahuna와 마찬가지로 위치타에서 공연된다.이 도시는 또한 오랫동안 방영된 만화 '위협 [137]데니스'의 배경이기도 하다.포스트 아포칼립스 형태의 도시는 또한 조엘 샤르보네가 쓴 3부작의 대부분인 "시험"의 배경이기도 하다.마찬가지로 닐 슈스터만의 유토피아 소설 "썬더헤드"에서 위치타는 줄거리를 진행하는 주요 사건의 장소이다.

와이어트 [138][139]얼프의 삶과 경력을 드라마화한 영화 위치타와 와이어트 얼프의 일부분은 위치타를 배경으로 한다.1959년부터 1960년까지의 단기 TV 서부 위치타 타운은 도시의 초기 몇 [140]년 동안 촬영되었다.도시를 배경으로 한 다른 영화들은 전부 또는 부분적으로 굿 럭, 미스 와이코프,[141] 비행기, 기차, 자동차, 아이스 하베스트, 그리고 나이트 앤 데이 (2010)[142][143][144]를 포함한다.영화 Mars Attacks!와 Twister의 장면들은 위치타에서 [145]촬영되었다.

AMD는 코드명 위치타(Wichita)라는 새로운 프로세서를 2012년에 출시할 계획이었지만 새로운 디자인을 위해 프로젝트가 취소되었습니다.

★★★★★★

위치타에는 프로, 준프로, 비프로 및 대학 스포츠 팀이 몇 개 있습니다.프로팀에는 위치타 썬더 아이스하키팀과 위치타 포스 실내축구팀이 있다.2020년, 로런스-듀몬트 [146]스타디움 부지의 리버프런트 스타디움에서 열린 더블 A 센트럴의 마이너 리그 야구 팀 위치타 윈드 서지.2020년 데뷔는 COVID-19 대유행으로 [147]연기되었다.2021년 메이저리그의 마이너리그 개편으로 트리플A 경기를 치르지 못한 채 더블A 센트럴로 추락했다.이 도시는 1990년에 처음 열린 콘 페리 투어의 프로 골프 대회인 에어 캐피탈 클래식을 주최한다.

과거 위치타에서 활동하던 프로팀으로는 위치타 에어로스와 위치타 랭글러스 야구단, 위치타 윙스 실내축구단, 위치타 윈드(1980년대 초 에드먼턴 오일러스 내셔널 하키 리그 팜팀), 위치타 와일드 풋볼팀 등이 있다.준프로팀에는 캔자스 쿠거스와 캔자스 다이아몬드백스 축구팀이 [148][149]포함됐다.비프로팀으로는 위치타 바바리안스 럭비 유니언 팀과 위치타 월드 11 크리켓 [150][151]팀이 있었다.

이 도시를 연고지로 하는 대학팀에는 위치타 주립 대학 쇼커즈, 뉴먼 대학 제트스, 프렌즈 대학 팰콘스가 있다.WSU 쇼커스는 남녀 농구, 야구, 배구, 육상, 테니스, 볼링에서 경쟁하는 NCAA 디비전 1 팀이다.Newman Jets는 야구, 농구, 볼링, 크로스컨트리, 골프, 축구, 테니스, 레슬링, 배구, 그리고 응원/댄스에서 경쟁하는 NCAA 디비전 II 팀이다.프렌즈 팔콘스는 NAIA의 지역 IV에서 축구, 배구, 축구, 크로스컨트리, 농구, 테니스, 육상, 골프에 출전한다.

몇몇 스포츠 경기장은 시내와 그 주변에 있다.시내에 있는 인트라스트 뱅크 아레나는 위치타 썬더스의 본거지인 15,000석 규모의 다목적 경기장입니다.시내 바로 서쪽에 있는 로렌스-듀몬트 스타디움은 위치타의 다양한 마이너 리그 야구 팀들의 홈구장이었던 중형 야구장이었다.이곳은 또한 마이너리그인 전국야구대회와 매년 열리는 전국대회 개최지이기도 하다.

시내 바로 서쪽에 위치한 위치타 아이스 아레나는 아이스 스케이팅 경기에 사용되는 공공 아이스 스케이트 링크입니다.게다가 센츄리 II는 프로 레슬링 토너먼트, 정원 가꾸기 쇼, 스포츠 용품 전시회, 그리고 다른 레크리에이션 활동에 사용되어 왔다.WSU 캠퍼스에는 다음 2개의 주요 장소가 있습니다.WSU 쇼커 야구팀이 있는 풀사이즈 야구장이 있는 중형 경기장 에크 스타디움과 WSU 쇼커 농구팀이 있는 대학 농구 코트가 있는 중형 돔 지붕 원형 경기장 찰스 코흐 아레나.Koch Arena는 또한 도시 전체 및 지역 고등학교 체육 행사, 콘서트 및 기타 엔터테인먼트에도 광범위하게 사용됩니다.도시의 바로 북쪽에는 자동차, 트럭, 오토바이 경주 및 기타 모터스포츠 행사에 널리 사용되는 타원형 자동차 경주장인 81 모터스피드웨이가 있다.인접한 파크 시티에는 하트만 아레나와 샘 풀코 파빌리온스가 있는데, 샘 풀코 파빌리온스는 소규모 로데오, 말 쇼, 가축 대회, 전시를 위해 개발된 중저용량의 저지붕 경기장입니다.

위치타에는 캔자스 스포츠 명예의 전당과 위치타 스포츠 명예의 전당과 [152][153]박물관이라는 두 개의 스포츠 박물관이 있다.

| team | . | ★★★ | ★★★★ |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1992 | |||

| 2020 | A A | ★★★ | |

| 2019 | MASL 2 | 축구 |

| ★★★ | ★★★ | ★★★ | 의 » » |

|---|---|---|---|

| 주립 | ★★★ | 디비전 INCAA I | 15 |

| ★★★ | 디비전 IINCAA II | 16 | |

| 15 |

★★★

주 법령에 따르면 위치타는 일류 [154]도시입니다.1917년 이후, 그것은 의회-관리자 형태의 [155]정부를 가지고 있다.시의회는 4년마다 민선 7명으로 구성되며 임기는 엇갈린다.대표적인 목적을 위해 시는 6개의 구역으로 나뉘며 각 구역에서 1명의 시의원이 선출된다.시장은 제7대 시의회 의원으로서 총선거로 되어 있다.시의회는 시의 정책을 정하고, 법률과 조례를 제정하고, 세금을 부과하고, 시 예산을 승인하며, 시민 위원회와 자문 [156]위원회에 위원을 임명한다.그것은 [154]매주 화요일에 만난다.시 관리자는 시의 운영 및 인사 관리, 연간 시 예산 제출, 시의회 자문, 시의회 의사일정 준비 및 비부처 [155]활동의 감독에 대한 책임을 지는 시의 최고 책임자입니다.2020년 현재 시의회는 브랜든 위플 시장, 브랜든 존슨(1구역), 베키 터틀(2구역), 제임스 클렌데닌(3구역), 제프 블러보(4구역), 브라이언 프라이(5구역), 신디 클레이콤(6구역)으로 구성되어 있다.[157]도시 관리자는 로버트 레이튼이다.[158]

1871년에 설립된 위치타 경찰서는 시의 사법 [159]기관이다.600명 이상의 장교들을 포함하여 800명 이상의 직원을 거느린 이 회사는 [160]캔자스 주에서 가장 큰 법 집행 기관입니다.1886년에 조직된 위치타 소방서는 도시 전역에 22개의 역을 운영하고 있다.4개 대대로 조직되어 있으며, 400명 이상의 상근 소방관을 [161]고용하고 있다.

위치타는 군청 소재지로서 세지윅 카운티의 행정 중심지이다.카운티 법원은 시내에 있으며, 카운티 정부의 대부분의 부서는 도시를 [162]거점으로 영업을 하고 있습니다.

미국 정부의 많은 부서와 기관은 위치타에 시설을 가지고 있다.역시 시내에 있는 위치타 미법원은 [163]캔자스 특별구 연방법원의 세 개의 법원 중 하나이다.미 공군은 매코넬 공군기지를 도시 [164]남동쪽에서 운영하고 있다.로버트 J. 돌 재향군인 의료 및 지역 사무소 센터의 캠퍼스는 위치타 [165]동부에 있는 미국 54층에 있다.연방수사국,[166] 식품의약국,[167] 국세청을[168] 비롯한 다른 기관들은 도시 곳곳에 사무실을 두고 있다.

위치타는 캔자스 제4의회 선거구 내에 있다.캔자스 주의회를 대표하기 위해 이 도시는 캔자스 상원 16, 25, 32번 지역구와 캔자스 하원 [154]81번, 83번, 101번, 103번 및 105번 지역구에 있습니다.

★★

초중등교육

5만 명이 넘는 학생이 있는 위치타 USD 259는 [169]캔자스에서 가장 큰 학군입니다.그것은 12개의 고등학교, 16개의 중학교, 61개의 초등학교, 그리고 12개 이상의 특수 [170]학교와 프로그램을 포함하여 도시에서 90개 이상의 학교를 운영하고 있다.위치타의 외곽 지역은 Andover USD 385, Circle USD 375, Derby USD 265, Goddard USD 265, Haysville USD 261, 옥수수 USD 266 및 Valley Center 262를 포함한 교외의 공립 통합 학군 내에 있습니다.이들 학교 중 일부는 다른 학군에도 불구하고 위치타 시 [171]경계 내에 있다.

위치타에는 [172]35개 이상의 사립 및 교구 학교가 있다.천주교 위치타 교구는 14개의 초등학교와 2개의 고등학교, 비숍 캐럴 카톨릭 고등학교와 카판산 카멜 고등학교 [173]등 시내 16개의 가톨릭 학교를 감독하고 있다.루터 교회-미주리 시노드는 베서니 루터 학교(그레이드 PK-5)와 홀리 크로스 루터 학교(PK-8)[174][175] 두 개의 루터 학교를 운영하고 있습니다.위치타에는 세 명의 천사학교와 위치타 재림교 기독교 아카데미 두 곳이 있다.[176][177]이 도시의 다른 기독교 학교로는 칼바리 기독교 학교 (PK-12), 중앙 기독교 학교 (K-10), 위치타 고전 학교 (K-12), 해돋이 기독교 학교 (PK-12), 트리니티 아카데미 (K-12), 위치타 친구 학교 (PK-6), 그리고 전승이 있다.또 위치타 이슬람 협회가 운영하는 안누르 학교(PK-8)도 있다.이 도시의 사립학교에는 위치타 대학, 독립 학교, 노스필드 인문학교와 3개의 몬테소리 [178]학교가 있다.

단과대학 및 단과대학

위치타에 본교 캠퍼스가 있는 대학은 3개입니다.가장 큰 대학은 위치타 주립대(WSU)로 카네기가 "R2: 박사과정 대학 – 고등 연구 활동"으로 분류한 공립 대학이다.WSU는 14,000명 이상의 학생이 있으며 [179][180]캔자스 주에서 세 번째로 큰 대학입니다.WSU의 메인 캠퍼스는 Wichita 북동쪽에 있으며,[181] 도시권 주변에는 여러 위성 캠퍼스가 있습니다.사립 비종파 기독교 대학인 프렌즈 대학교는 사립 가톨릭 [182][183]대학인 뉴먼 대학교와 마찬가지로 웨스트 위치타에 본 캠퍼스가 있다.1995년에 설립된 위치타 지역 기술 대학은 2018년에 위치타 주립 대학의 응용 과학 및 기술 대학에 합병되어 현재는 WSU Tech로 알려져 있습니다.

위치타 외곽에 위치한 몇몇 대학과 대학들은 도시와 그 주변에 위성 위치를 운영하고 있다.캔자스 대학 의과대학은 위치타에 [184]세 개의 캠퍼스 중 하나를 가지고 있다.Baker University, Butler Community College, Embry-Riddle Aeronical University, Southwestern College, Tabor College, Vatterott College 및 Webster University of [185][186][187][188]Phoenix를 포함한 비영리 기관과 마찬가지로 위치타 시설을 보유하고 있습니다.

Media

The Wichita Eagle, which began publication in 1872, is the city's major daily newspaper.[189] Colloquially known as The Eagle. In 1960, the Wichita Eagle purchased Beacon Newspaper Corp. After purchasing the paper, the Wichita Eagle begin publishing the Eagle, which was a morning and afternoon newspaper, and the Beacon which was the evening paper.[190] The Wichita Business Journal is a weekly newspaper that covers local business events and developments.[191] Several other newspapers and magazines, including local lifestyle, neighborhood, and demographically focused publications are also published in the city.[192] These include: The Community Voice, a weekly African American community newspaper;[193] El Perico, a monthly Hispanic community newspaper;[194][195] The Liberty Press, monthly LGBT news;[196] Splurge!, a monthly local fashion and lifestyle magazine;[197] The Sunflower, the Wichita State University student newspaper.[198] The Wichita media market also includes local newspapers in several surrounding suburban communities.

The Wichita radio market includes Sedgwick County and neighboring Butler and Harvey counties.[199] Six AM and more than a dozen FM radio stations are licensed to and/or broadcast from the city.[200]

Wichita is the principal city of the Wichita-Hutchinson, Kansas television market, which comprises the western two-thirds of the state.[201] All of the market's network affiliates broadcast from Wichita with the ABC, CBS, CW, FOX and NBC affiliates serving the wider market through state networks of satellite and translator stations.[202][203][204][205][206][207] The city also hosts a PBS member station, a Univision affiliate, and several low-power stations.[208][209]

Infrastructure

Flood control

Wichita suffered severe floods of the Arkansas river in 1877, 1904, 1916, 1923, 1944, 1951 and 1955. In 1944 the city flooded 3 times in 11 days.[210] As a result of the 1944 flood, the idea for the Wichita-Valley Center Floodway (locally known as the "Big Ditch") was conceived. The project was completed in 1958. The Big Ditch diverts part of the Arkansas River's flow around west-central Wichita, running roughly parallel to the Interstate 235 bypass.[60][211] A second flood control canal lies between the lanes of Interstate 135, running south through the central part of the city. Chisholm Creek is diverted into this canal for most of its length.[60][212] The city's flood defenses were tested in the Great Flood of 1993. Flooding that year kept the Big Ditch full for more than a month and caused $6 million of damage to the flood control infrastructure. The damage was not fully repaired until 2007.[213] In 2019, the Floodway was renamed the MS Mitch Mitchell Floodway in honor of the man credited for its creation.[214]

Utilities

Evergy provides electricity.[215] Kansas Gas Service provides natural gas.[216] The City of Wichita provide water and sewer.[217] Multiple privately owned trash haulers, licensed by the county government, offer trash removal and recycling service.[218] Cox Communications and Spectrum offer cable television, and AT&T U-Verse offers IPTV.[219] All three also offer home telephone and broadband internet service.[220] Satellite TV is offered by DIRECTV and DISH. Satellite internet is available from Viasat, Hughes, and soon Starlink.

Health care

Ascension Via Christi operates three general medical and surgical hospitals in Wichita—Via Christi Hospital St. Francis, Via Christi Hospital St. Joseph, and Via Christi Hospital St. Teresa—and other specialized medical facilities.[221] The Hospital Corporation of America manages a fourth general hospital, Wesley Medical Center, along with satellite locations around the city.[222] All four hospitals provide emergency services. In addition, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs runs the Robert J. Dole VA Medical Center, a primary and secondary care facility for U.S. military veterans.[165]

Transportation

Highway

The average commute time in Wichita was 18.2 minutes from 2013 to 2017.[223] Several federal and state highways pass through the city. Interstate 35, as the Kansas Turnpike, enters the city from the south and turns northeast, running along the city's southeastern edge and exiting through the eastern part of the city. Interstate 135 runs generally north-south through the city, its southern terminus lying at its interchange with I-35 in south-central Wichita. Interstate 235, a bypass route, passes through north-central, west, and south-central Wichita, traveling around the central parts of the city. Both its northern and southern termini are interchanges with I-135. U.S. Route 54 and U.S. Route 400 run concurrently through Wichita as Kellogg Avenue, the city's primary east-west artery, with interchanges, from west to east, with I-235, I-135, and I-35. U.S. Route 81, a north-south route, enters Wichita from the south as Broadway, turns east as 47th Street South for approximately half a mile, and then runs concurrently north with I-135 through the rest of the city. K-96, an east-west route, enters the city from the northwest, runs concurrently with I-235 through north-central Wichita, turns south for approximately a mile, running concurrently with I-135 before splitting off to the east and traveling around northeast Wichita, ultimately terminating at an interchange with U.S. 54/U.S. 400 in the eastern part of the city. K-254 begins at I-235's interchange with I-135 in north-central Wichita and exits the city to the northeast. K-15, a north-south route, enters the city from the south and joins I-135 and U.S. 81 in south-central Wichita, running concurrently with them through the rest of the city. K-42 enters the city from the southwest and terminates at its interchange with U.S. 54/U.S. 400 in west-central Wichita.[60]

Bus

Wichita Transit operates 53 buses on 18 fixed bus routes within the city. The organization reports over 2 million trips per year (5,400 trips per day) on its fixed routes. Wichita Transit also operates a demand response paratransit service with 320,800 passenger trips annually.[224] A 2005 study ranked Wichita near the bottom of the fifty largest American cities in terms of percentage of commuters using public transit. Only 0.5% used it to get to or from work.[225]

Greyhound Lines provides intercity bus service northeast to Topeka and south to Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. Bus service is provided daily north towards Salina and west towards Pueblo, Colorado by BeeLine Express (subcontractor of Greyhound Lines).[226][227] The Greyhound bus station that was built in 1961 at 312 S Broadway closed in 2016, and services relocated 1 block northeast to the Wichita Transit station at 777 E Waterman.[228]

Air

The Wichita Airport Authority manages the city's two main public airports, Wichita Dwight D. Eisenhower National Airport and Colonel James Jabara Airport.[229] Located in the western part of the city, Wichita Dwight D. Eisenhower National Airport is the city's primary airport as well as the largest airport in Kansas.[60][229] Seven commercial airlines (Alaska, Allegiant, American, Delta, Frontier, Southwest & United) serve Wichita Dwight D. Eisenhower National Airport with non-stop flights to several U.S. airline hubs.[230] Jabara Airport is a general aviation facility on the city's northeast side.[231] The city also has several privately owned airports. Cessna Aircraft Field and Beech Factory Airport, operated by manufacturers Cessna and Beechcraft, respectively, lie in east Wichita.[232][233] Two smaller airports, Riverside Airport and Westport Airport, are in west Wichita.[234][235]

Rail

Two Class I railroads, BNSF Railway and Union Pacific Railroad (UP), operate freight rail lines through Wichita.[236] UP's OKT Line runs generally north-south through the city; north of downtown, the line consists of trackage leased to BNSF.[60][237] An additional UP line enters the city from the northeast and terminates downtown.[60] BNSF's main line through the city enters from the north, passes through downtown, and exits to the southeast, paralleling highway K-15.[60][238] The Wichita Terminal Association, a joint operation between BNSF and UP, provides switching service on three miles (5 km) of track downtown.[239] In addition, two lines of the Kansas and Oklahoma Railroad enter the city, one from the northwest and the other from the southwest, both terminating at their junction in west-central Wichita.[60]

Wichita has not had passenger rail service since 1979.[240] The nearest Amtrak station is in Newton 25 miles (40 km) north, offering service on the Southwest Chief line between Los Angeles and Chicago.[236] Amtrak offers bus service from downtown Wichita to its station in Newton as well as to its station in Oklahoma City, the northern terminus of the Heartland Flyer line.[241]

Walkability

A 2014 study by Walk Score ranked Wichita 41st most walkable of fifty largest U.S. cities.[242]

Cycling

After numerous citizen surveys showed Wichitans want better bicycle infrastructure, The Wichita Bicycle Master Plan, a set of guidelines toward the development of a 149-mile Priority Bicycle Network, was endorsed by the Wichita City Council on February 5, 2013, as a guide to future infrastructure planning and development. As a result, Wichita's bikeways covered 115 miles of the city by 2018. One-third of the bikeways were added between 2011, when the plan was still in development, and 2018.[243][244]

The League of American Bicyclists added Wichita as one of 462 bicycle-friendly communities to its Fall, 2017 list of Bicycle Friendly Communities, awarding it a bronze award.[245]

Notable people

Crime and law enforcement

Wyatt Earp served as a lawman in several Old West frontier towns, including Wichita. Other Old West figures lived in Wichita for a while: James Earp, Cassius M. Hollister, Bat Masterson, Ed Masterson, and James Masterson. Serial killer Dennis Rader, also known as BTK, was born and raised in Wichita and also committed his crimes in the Wichita area.

Politics

Numerous politicians and government employees were born, raised, or lived in Wichita. Mike Pompeo, former U.S. Secretary of State, and Director of the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency both under Donald Trump, began his political career in the Wichita area as 4th district Congressman. Robert Gates, former U.S. Secretary of Defense, and former Director of the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency, is a Wichita native and graduate of Wichita schools.[246] Dan Glickman, former Secretary of Agriculture, began his political career in Wichita, first on the local school board, then as 4th district Congressman.[247]

Business

The Koch family, specifically Charles and David Koch (Koch Industries), prominent billionaires, political activists, philanthropists, were born and raised in Wichita. Additionally, Dan and Frank Carney (Pizza Hut), Clyde Cessna (Cessna Aircraft), Walter Beech and Olive Ann Beech (Beech Aircraft), Bill Lear (Lear Jet), Lloyd Stearman (Stearman Aircraft), William Coleman (Coleman Company), billionaire Phil Ruffin (Treasure Island Hotel and Casino) all were raised or lived in Wichita.

Athletes

Athletes including Pro Football Hall of Fame running back Barry Sanders,[246] Basketball Hall of Famer Lynette Woodard, and UFC flyweight fighter Tim Elliott were all born or raised in Wichita. Summer Olympic medal-winning athletes Jim Ryun (track and field), Nico Hernandez (boxing), and Kelsey Stewart (softball) are all from Wichita.

Media

Actress Kirstie Alley, known for her role in the TV show Cheers, was born and raised in Wichita and lives in the city part-time.[246] Actor Don Johnson, lead actor in the TV series Miami Vice and Nash Bridges, lived in Wichita for most of his childhood.[246] Musician Joe Walsh, founding member of the band James Gang and later member of The Eagles, is from Wichita. Jim Lehrer, who was a journalist, novelist, and news anchor for PBS NewsHour, was born and attended grade school in Wichita. W. Eugene Smith an American photojournalist.

Sister cities

Cancún, Quintana Roo, Mexico - November 25, 1975[248]

Cancún, Quintana Roo, Mexico - November 25, 1975[248] Kaifeng, Henan, China - December 3, 1985[249]

Kaifeng, Henan, China - December 3, 1985[249] Orléans, Loiret, France - August 16, 1944,[250][251] through Sister Cities International

Orléans, Loiret, France - August 16, 1944,[250][251] through Sister Cities International Tlalnepantla de Baz, State of Mexico, Mexico[252]

Tlalnepantla de Baz, State of Mexico, Mexico[252]

Gallery

Campbell Castle in Wichita's Riverside neighborhood (2013)

Charles Koch Arena at Wichita State University, is home to the Wichita State Shockers (2010).

Davis Building at Friends University (2006)

Eck Stadium at Wichita State University (2005)

Edwin A. Ulrich Museum of Art at Wichita State University (2007)

The Epic Center, the tallest building in Wichita (2006)

Exploration Place science museum (2013)

Locomotives on display at the Great Plains Transportation Museum (2007)

Intrust Bank Arena (2013)

The John Mack Bridge over the Arkansas River in south Wichita (2013)

Kansas Aviation Museum, formerly Wichita Municipal Airport from 1935 to 1951 (2007)

Lawrence-Dumont Stadium (2014)

The Robert J. Dole Veterans Affairs Medical Center (2013)

The Downing Gorilla Forest at the Sedgwick County Zoo (2013)

Wichita Art Museum (2012)

Intrust Bank Arena, the city's main entertainment and sports venue since 2010

See also

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Sedgwick County, Kansas

- Abilene Trail

- Arkansas Valley Interurban Railway

- Joyland Amusement Park

- Wichita Public Schools

- McConnell Air Force Base

Notes

- ^ Mean monthly maxima and minima (i.e. the expected highest and lowest temperature readings at any point during the year or given month) calculated based on data at said location from 1991 to 2020.

- ^ Official records for Wichita have been kept at various locations in and around the city from July 1888 to November 1953, and at the Mid-Continent Airport since December 1953 (currently named Wichita Dwight D. Eisenhower National Airport). For more information, see Threadex

References

- ^ a b Harris, Richard (2002). "The Air Capital Story: Early General Aviation & Its Manufacturers". In Flight USA.

- ^ "Travel Translator: Your guide to the local language in Wichita". VisitWichita.com. September 18, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f "Wichita, Kansas", Geographic Names Information System, United States Geological Survey

- ^ "2021 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 14, 2021.

- ^ a b "Profile of Wichita, Kansas in 2020". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on November 14, 2021. Retrieved November 14, 2021.

- ^ a b c d "QuickFacts; Wichita, Kansas; Population, Census, 2020 & 2010". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on August 22, 2021. Retrieved August 21, 2021.

- ^ a b "City and Town Population Totals: 2020-2021". United States Census Bureau. May 29, 2022. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- ^ a b "2020 Population and Housing State Data". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 22, 2021.

- ^ United States Postal Service (2012). "USPS - Look Up a ZIP Code". Retrieved February 15, 2012.

- ^ "Wichita". CollinsDictionary.com. Collins English Dictionary - Complete & Unabridged 11th Edition. Retrieved October 21, 2012.

- ^ Miner, Prof. Craig (Wichita State Univ. Dept. of History), Wichita: The Magic City, Wichita Historical Museum Association, Wichita, KS, 1988

- ^ Howell, Angela and Peg Vines, The Insider's Guide to Wichita, Wichita Eagle & Beacon Publishing, Wichita, KS, 1995

- ^ a b McCoy, Daniel (interview with Beechcraft CEO Bill Boisture), "Back to Beechcraft", Wichita Business Journal, February 22, 2013

- ^ a b c Harris, Richard, "The Air Capital Story: Early General Aviation & Its Manufacturers", reprinted from In Flight USA magazine on author's own website, 2002/2003

- ^ a b c Harris, Richard, (Chairman, Kansas Aviation Centennial; Kansas Aviation History Speaker, Kansas Humanities Council; Amer. Av. Historical Soc.), "Kansas Aviation History: The Long Story" Archived August 8, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, 2011, Kansas Aviation Centennial website Archived December 29, 2018, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Grove Park Archaeological Site". Historic Preservation Alliance of Wichita and Sedgwick County. Retrieved March 21, 2015.

- ^ Brooks, Robert L. "Wichitas". Encyclopedia of the Great Plains. University of Nebraska–Lincoln. Retrieved March 21, 2014.

- ^ Sturtevant, William C. (1967). "Early Indian Tribes, Culture Areas, and Linguistic Stocks [Map]". Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved March 21, 2015.

- ^ "Louisiana Purchase". Kansapedia. Kansas Historical Society. Retrieved March 21, 2015.

- ^ "Kansas Territory". Kansapedia. Kansas Historical Society. Retrieved March 21, 2015.

- ^ a b "Days of Darkness: 1820-1934". Wichita and Affiliated Tribes. Retrieved April 30, 2019.

- ^ a b Sowers, Fred A. (1910). "Early History of Wichita". History of Wichita and Sedgwick County, Kansas. Chicago: C.F. Cooper & Co. Retrieved March 21, 2015.

- ^ Elam, Earl H. (June 15, 2010). "Wichita Indians". Handbook of Texas (online ed.). Texas State Historical Association.

- ^ a b c d Howell, Angela; Vines, Peg (1995). The Insider's Guide to Wichita. Wichita, Kansas: Wichita Eagle & Beacon Publishing.

- ^ a b c "History of Wichita". Wichita Metro Chamber of Commerce. Archived from the original on March 16, 2015. Retrieved March 21, 2015.

- ^ a b c "Midtown Neighborhood Plan" (PDF). Wichita-Sedgwick County Metropolitan Area Planning Department. 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 5, 2016. Retrieved March 21, 2015.

- ^ a b c Miner, Craig (1988). Wichita: The Magic City. Wichita, Kansas: Wichita Historical Museum Association.

- ^ "Oldtown History". OldtownWichita.com. Archived from the original on January 19, 2009. Retrieved March 21, 2015.

- ^ a b c "Delano's Colorful History". Historic Delano, Inc. Retrieved March 21, 2015.

- ^ "History of Wichita State University". Wichita State University. Retrieved March 26, 2015.

- ^ "History". Friends University. Retrieved March 26, 2015.

- ^ a b "Census of Population and Housing". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 26, 2015.

- ^ "Overview". Delano Neighborhood Plan. City of Wichita, Kansas. Archived from the original on August 6, 2013. Retrieved March 26, 2015.

- ^ a b Price, Jay M. (2005). El Dorado : legacy of an oil boom. Charleston, SC: Arcadia. ISBN 978-0738539713.

- ^ "Petroleum Refining: A 125 Year Kansas Legacy" (PDF). Kansas Department of Health and Environment. Retrieved March 19, 2015.

- ^ Dilsaver, Dick (November 18, 1967). "Fred Koch, Industrialist, Dies in Utah". The Wichita Beacon.

- ^ Aeronautical Yearbook, 1929. Aeronautical Chamber of Commerce.

- ^ Harrow, Christopher (February 29, 2020). "How is Wichita, Kansas the "Air Capital of the World"?". International Aviation HQ.

- ^ Tanner, Beccy (January 5, 2012). "Boeing's Wichita history dates to 1927". The Wichita Eagle. Retrieved March 26, 2015.

- ^ a b "History of the Building". Kansas Aviation Museum. June 9, 2014. Retrieved March 26, 2015.

- ^ Herman, Arthur. Freedom's Forge: How American Business Produced Victory in World War II, pp. 297-300, 307-8, 314-318, 321, Random House, New York, NY, 2012. ISBN 978-1-4000-6964-4.

- ^ "Learjet: A Brief History" (PDF). Bombardier Inc. January 2008. Retrieved March 26, 2015.

- ^ a b c d "Wichita, Kansas". Encyclopedia of the Great Plains. University of Nebraska–Lincoln. Retrieved March 28, 2015.

- ^ "About Us". Mentholatum. Retrieved March 28, 2015.

- ^ "First Light (1900-1929)". Coleman Company. Archived from the original on March 18, 2013. Retrieved March 28, 2015.

- ^ Kieler, Ashlee (July 14, 2015). "The White Castle Story: The Birth Of Fast Food & The Burger Revolution". Consumerist.com. Retrieved April 27, 2020.

- ^ "Bronze Sculpture of Lunch Counter for Downtown Park is Tribute to Civil Rights Activists". The Wichita Eagle. February 4, 1998. Retrieved March 28, 2015.

- ^ Wilkerson, Isabel (August 4, 1991). "Drive Against Abortion Finds a Symbol: Wichita". The New York Times. Retrieved March 28, 2015.

- ^ Davey, Monica; Stumpe, Joe (May 31, 2009). "Abortion Doctor Shot to Death in Kansas Church". The New York Times. Retrieved March 28, 2015.

- ^ "Wichita Downtown Development Corp". OldtownWichita.com. Retrieved March 28, 2015.

- ^ Neil, Denise (December 6, 2014). "After 5 years, Intrust Bank Arena still battles image problem". The Wichita Eagle. Retrieved March 28, 2015.

- ^ McMillin, Molly (July 29, 2014). "End of an era: Boeing in final stages of leaving Wichita". The Wichita Eagle. Retrieved March 28, 2015.

- ^ "Airbus Americas". OldtownWichita.com. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 28, 2015.

- ^ Siebenmark, Jerry. "Eisenhower's granddaughter helps Wichita rename its airport". The Wichita Eagle. Retrieved March 28, 2015.

- ^ "2003-2004 Official Transportation Map" (PDF). Kansas Department of Transportation. 2003. Retrieved January 1, 2011.

- ^ "City Distance Tool". Geobytes. Archived from the original on October 5, 2010. Retrieved January 1, 2011.

- ^ "Ecoregions of Nebraska and Kansas" (PDF). Environmental Protection Agency. 2001. Retrieved January 1, 2011.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Arkansas River and Wellington-McPherson Lowlands - Introduction". Kansas Geological Survey. May 3, 2005. Archived from the original on June 7, 2011. Retrieved January 1, 2011.

- ^ "Sedgwick County Geohydrology - Geography". Kansas Geological Survey. December 1965. Retrieved January 1, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "City of Wichita" (PDF). Kansas Department of Transportation. June 2010. Retrieved January 1, 2011.

- ^ "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 2, 2012. Retrieved July 6, 2012.

- ^ "General Highway Map - Sedgwick County, Kansas" (PDF). Kansas Department of Transportation. June 2009. Retrieved January 1, 2011.

- ^ "Kansas Tornado History - Historical Tornado Facts". Tornadochaser.com. Archived from the original on March 27, 2009. Retrieved September 12, 2009.

- ^ "1991 Wichita-area tornado". Archived from the original on August 20, 2011. Retrieved April 21, 2011.

- ^ "PHOTOS: 1965 Wichita tornado". Archived from the original on May 4, 2011. Retrieved April 21, 2011.

- ^ a b "Historical Weather for Wichita, Kansas, United States of America". Weatherbase. Retrieved January 25, 2012.

- ^ a b c "Summary of Monthly Normals 1991-2020". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved October 13, 2021.

- ^ a b c "NOWData - NOAA Online Weather Data". National Weather Service Forecast Office - Wichita, KS. Retrieved October 13, 2021.

- ^ "WMO Climate Normals for WICHITA/MID-CONTINENT ARPT KS 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved March 11, 2014.

- ^ "Wichita Nightlife and Food - WichitaGov". wichitagov.org. Archived from the original on August 14, 2003.

- ^ "Historic Preservation Main". City of Wichita. Archived from the original on October 19, 2007. Retrieved October 30, 2007.

- ^ Courtwright, Julie (2000). "Want to Build a Miracle City? : War Housing in Wichita" (PDF). Kansas History: A Journal of the Central Plains. 23 (4). Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ^ A revitalization plan for the Hilltop Neighborhood: 60 years of community in southeast Wichita May, 2000, City of Wichita, retrieved February 20, 2020

- ^ Geiszler-Jones, Amy, "Community Health," The Shocker, Wichita State University, as posted at University of Kansas retrieved February 20, 2020

- ^ OCR extracts from various publications, Google, retrieved February 20, 2020

- ^ Tihen, Edward, "Plainview (sic), Planeview, Beechwood,", in Tihen Notes, Special Collections, Wichita State University, retrieved February 20, 2020

- ^ United States Census Bureau. "Census of Population and Housing". Retrieved August 18, 2014.

- ^ "Race and Ethnicity in the United States - Statistical Atlas". statisticalatlas.com.

- ^ a b c d e f "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved November 12, 2011.

- ^ a b "OMB Bulletin No. 10-02" (PDF). Office of Management and Budget. December 1, 2009. p. 59. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 21, 2017. Retrieved January 22, 2011.

- ^ "OMB Bulletin No. 10-02" (PDF). Office of Management and Budget. December 1, 2009. p. 117. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 21, 2017. Retrieved January 22, 2011.

- ^ Thomas, G. Scott (2011). "Metro Area Populations as of July 2011: 2011 - United States -- Metropolitan Statistical Area". 2011 American City Business Journals. Retrieved April 30, 2011.

- ^ "Annual Estimates of the Population of Metropolitan and Micropolitan Statistical Areas: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2013". 2013 Population Estimates. United States Census Bureau, Population Division. August 18, 2014. Archived from the original on June 27, 2014. Retrieved August 18, 2014.

- ^ "Population and Housing Occupancy Status: 2010 - United States -- Combined Statistical Area". 2010 Census National Summary File of Redistricting Data. United States Census Bureau, Population Division. 2010. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved April 30, 2011.

- ^ "Population and Housing Occupancy Status: 2010 - State -- County / County Equivalent". 2010 Census Redistricting Data (Public Law 94-171) Summary File. United States Census Bureau. Retrieved April 30, 2011.[dead link]

- ^ "The White Castle Story: The Birth of Fast Food & the Burger Revolution". July 14, 2015.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on December 12, 2018. Retrieved December 29, 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Slideshow: See the best-known brands in Kansas". www.bizjournals.com. August 12, 2019. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

- ^ "Hawker Beechcraft secures $40 million incentive package to remain in Wichita". Retrieved January 2, 2011.

- ^ a b "Wichita Chamber of Commerce". Wichitakansas.org. Retrieved July 15, 2013.

- ^ "Hospital ready for visitors" Archived July 23, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, Wichita Eagle and Kansas.com, July 18, 2010.

- ^ Tanner, Becky (September 1, 2016). "Wichita's Wesley Children's Hospital Officially Opens". The Wichita Eagle.

- ^ "Forbes article". Forbes.

- ^ "uipl_3002c2a3.html." United States Department of Labor. Retrieved on May 26, 2009.

- ^ "Wichita, Kansas". City-Data.com. Retrieved March 11, 2015.

- ^ "Best Places to Live 2006". Money Magazine. 2006. Archived from the original on August 5, 2008. Retrieved August 5, 2008.

- ^ "2008 MSN Real Estate best bargain markets". MSN Real Estate. 2008. Archived from the original on January 15, 2008. Retrieved August 26, 2008.

- ^ "Wichita, Kansas," U. S. News & World Report, retrieved December 28, 2019

- ^ "Wichita, Kansas, Crime Rate & Safety" U. S. News & World Report, retrieved December 28, 2019

- ^ "State Rankings on Overall Child Well-Being"2019 KIDS COUNT Data Book, Annie E. Casey Foundation, retrieved December 29, 2019

- ^ Bissionette, Bruce, The Wichita 4: Cessna, Moellendick, Beech & Stearman (from interviews with Matty Laird, Lloyd Stearman, Olive Ann Beech, Dwayne Wallace, Rawdon, Burnham, and other principals), Aviation Heritage Books, Destin, FL, 1999.

- ^ a b Rowe, Frank J. (aviation engineering executive) & Prof. Craig. Miner (Wichita State Univ. Dept. of History). Borne on the South Wind: A Century of Kansas Aviation, Wichita Eagle & Beacon Publishing Co., Wichita. 1994 (the standard reference work on Kansas aviation history)

- ^ a b Penner, Marci, editor, and Richard Harris, contributor, in "Wichita Aviation Industry" in "8 Wonders of Kansas Commerce" on the Kansas Sampler website of the Kansas Sampler Foundation, sponsored by the Kansas Humanities Council for the Kansas 150 Sesquicentennial, 2010–2011.

- ^ General Aviation Manufacturers Association (GAMA), GAMA Statistical Databook & Industry Outlook 2007, Washington, D.C.GAMA (General Aviation Manufacturers Association), GAMA Statistical Databook & Industry Outlook 2010 Archived July 22, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Washington, D.C. (which includes historical data for previous 10 years)

- ^ "Boeing to close Wichita Facility by end of 2013". Retrieved February 18, 2012.

- ^ "Wichita Art Museum Visitor Information". Wichitaartmuseum.org. Archived from the original on May 24, 2009. Retrieved September 12, 2009.

- ^ "About Us". Ulrich Museum of Art at Wichita State University. Retrieved September 14, 2015.

- ^ a b Who knew Wichita was such a talent pipeline to Broadway?" March 29, 2017, Wichita Eagle, retrieved April 3, 2017.

- ^ Leiker, Amy Renee, "Opera singer Sam Ramey to coach vocal music at WSU," August 29, 2012, Wichita Eagle, retrieved April 3, 2017.

- ^ "River Festival estimates record attendance". wichita.bizjournals.com.

- ^ "Riverfest attendance and button sales up, arrests down". kansas. Retrieved June 12, 2018.

- ^ "Riverfest slowly turning critics to fans with killer concert lineups". kansas. Retrieved June 12, 2018.

- ^ "Wichita Public Library - Programs - 28th Annual Academy Awards Shorts Archived October 6, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, website of the Wichita Public Library, City of Wichita, Wichita, Kansas, 03/03/2014, downloaded 09/22/2014

- ^ "26th Annual Academy Awards Shorts Archived December 31, 2014, at the Wayback Machine," press release, Wichita Public Library, as posted on [OldtownWichita.com], Wichita, Kansas, Jan.24, 2012, downloaded Sept.22, 2014

- ^ Pocowatchit, Rod "Wichita Public Library to present Oscar-nominated short films," Wichita Eagle, Wichita, Kansas Feb 17, 2012, Updated: Feb 17, 2012, downloaded Sep 22, 2014

- ^ Pocowatchit, Rod "Wichita Public Library Presents: Oscar Nominated Shorts 2014 Archived November 11, 2016, at the Wayback Machine" press release, The Orpheum Theatre, Wichita, Kansas January 3, 2014, downloaded Sep 22, 2014

- ^ Horn, John, Associated Press, "Obscure Oscar Nominated Films Face Battle," as published in The Sunday Gazette, March 12, 1998, Schenectady, New York, photocopied by Google News Archive Search, downloaded Sep 22, 2014

- ^ Jackson, Susan M., "Academy Award director to speak in Wichita," The Kansan, Salina, Kansas, March 26, 2010, downloaded September 22, 2014

- ^ "Tallgrass Film Association". Tallgrass Film Association.

- ^ Wichita Flight Festival official website, visited 2014-09-22

- ^ Brisbin, Airman 1st Class Katrina M., "'Wings Over McConnell' showcases Airmen," press release Archived September 25, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, Public Affairs Office, 22nd Air Refueling Wing, U.S. Air Force, McConnell Air Force Base, Wichita, KS, Posted February 10, 2012, Updated March 10, 2012

- ^ "Our Building". The Wichita-Sedgwick County Historical Museum. Archived from the original on July 6, 2017. Retrieved September 14, 2015.

- ^ Stokes, Keith. "Coleman Factory Outlet and Museum - Wichita, Kansas". Kansastravel.org. Retrieved July 15, 2013.

- ^ "Wichita Kansas Attractions". Wichitalinks.com. Archived from the original on November 5, 2017. Retrieved September 12, 2009.

- ^ "INTRUST Bank Arena". INTRUST Bank Arena. Retrieved July 15, 2013.

- ^ "Search". INTRUST Bank Arena.

- ^ "Welcome to Old Town". OldtownWichita.com. Retrieved September 14, 2015.

- ^ "Moody's Skid Row Beanery by Pat O'Connor: 1960s Wichita, KS Beatniks, Hoboes: Moody Connell Beats In Kansas". Vlib.us. Retrieved July 15, 2013.

- ^ "Future of Wichita's Towne West Square Unknown". KWCH TV. February 22, 2019.

- ^ Rengers, Carrie (June 16, 2009). "Office This reaches 75 percent occupancy with two new tenants Have You Heard? Wichita Eagle Blogs". Archived from the original on July 2, 2014. Retrieved July 15, 2013.

- ^ "8 Wonders of Kansas Art". kansassampler.org. Kansas Sampler Foundation. Retrieved October 10, 2015.

- ^ "Locations & Hours". Wichita Public Library. Retrieved July 24, 2018.

- ^ "Free programs". Wichita Public Library. January 10, 2011. Archived from the original on October 30, 2014. Retrieved February 12, 2011.

- ^ "Wichita Public Library - 2009 Annual Report" (PDF). Wichita Public Library. p. 26. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 15, 2014. Retrieved February 12, 2011.

- ^ "Charles Plymell". Map of Kansas Literature. Retrieved March 19, 2022.; Olmsted, Marc. "Goldmouth: An Introduction to the Films of Robert Branaman". Otherzine. Retrieved March 19, 2022.; "Auerhahn Press". verdantpress.com. Retrieved March 19, 2022.; "Exhibition Celebrates 60 Years Of Bruce Conner's Print Works". KMUW Wichita 89.1. September 17, 2014. Retrieved March 19, 2022.

- ^ Swanbeck, John (director) (1999). The Big Kahuna (Film). U.S.A.: Lions Gate Films.

- ^ "'Dennis the Menace' creator dies at 81; strip to continue". The Topeka Capital-Journal. AP. June 2, 2001. Archived from the original on October 25, 2013. Retrieved October 19, 2013.

- ^ Tourneur, Jacques (director) (1955). Wichita (Film). U.S.A.: Allied Artists Pictures Corporation.

- ^ Kasdan, Lawrence (director) (1994). Wyatt Earp (Film). U.S.A.: Warner Bros.

- ^ "Wichita Town". IMDb. Retrieved October 19, 2013.

- ^ Chomsky, Marvin J. (director) (1979). Good Luck, Miss Wyckoff (Film). U.S.A.: Bel Air/Gradison Productions.

- ^ Hughes, John (director) (1987). Planes, Trains & Automobiles (Film). U.S.A.: Paramount Pictures.

- ^ Ramis, Harold (director) (2005). The Ice Harvest (Film). U.S.A.: Focus Features.

- ^ Knight and Day at AllMovie

- ^ "12 Movies You Didn't Know Were Filmed In Wichita". 360Wichita.com. November 17, 2015.

- ^ Lefler, Dion (December 11, 2018). "City Hall Picks Team to Design, Build Wichita's New Minor League Baseball Park". The Wichita Eagle. Retrieved January 28, 2019.

- ^ "2020 Minor League Baseball Season Shelved". Minor League Baseball. June 30, 2020. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ^ "KSCOUGARS.COM". www.kscougars.com.

- ^ "Kansas Diamondbacks". www.hometeamsonline.com.

- ^ "Home". Wichita Rugby.

- ^ "Wichita World XI Cricket Club – Cricket Club in the Wichita Kansas Area". www.wwxicc.org.

- ^ "Kansas Sports Hall of Fame - Home". kshof.org.

- ^ "Wichita Sports hall of fame". Wichita Sports hall of fame.

- ^ a b c "Wichita". Directory of Kansas Public Officials. The League of Kansas Municipalities. Archived from the original on April 5, 2012. Retrieved March 14, 2012.

- ^ a b "City Manager". City of Wichita. Archived from the original on July 6, 2011. Retrieved April 30, 2011.

- ^ "City Council". City of Wichita. Archived from the original on June 12, 2011. Retrieved April 30, 2011.

- ^ "City of Wichita City Council". City of Wichita. Retrieved March 15, 2019.

- ^ "City Manager's Office". City of Wichita. Retrieved March 15, 2019.

- ^ "History of the Wichita Police Department". City of Wichita. Archived from the original on July 27, 2011. Retrieved April 30, 2011.

- ^ "-Departmental Information". City of Wichita. Retrieved April 30, 2011.

- ^ "About Us [Wichita Fire Department]". City of Wichita, Kansas. January 6, 2014. Archived from the original on December 30, 2013. Retrieved December 29, 2013.

- ^ "Sedgwick County, Kansas Government". Sedgwick County, Kansas. Retrieved July 30, 2012.

- ^ "Courthouse Information". U.S. District Court for the District of Kansas. Archived from the original on January 9, 2012. Retrieved August 25, 2013.

- ^ "FAQ Topic - Newcomers". U.S. Air Force. Archived from the original on October 5, 2013. Retrieved August 25, 2013.

- ^ a b "Locations - Robert J. Dole Department of Veterans Affairs Medical and Regional Office Center". U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Retrieved August 25, 2013.

- ^ "Kansas City Division - Territory/Jurisdiction". Federal Bureau of Investigation. Retrieved August 25, 2013.

- ^ "FDA Southwest Regional/District Offices". U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Archived from the original on February 1, 2015. Retrieved August 25, 2013.

- ^ "Contact My Local Office in Kansas". Internal Revenue Service. Retrieved August 25, 2013.

- ^ "2012-13 Demographic Snapshot". Wichita Public Schools. October 1, 2012. Retrieved June 12, 2013.

- ^ "Directory of Buildings" (PDF). Wichita Public Schools. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 18, 2011. Retrieved February 4, 2011.

- ^ "South Central Kansas School Districts". ALTEC at University of Kansas. 2003. Archived from the original on December 3, 2010. Retrieved February 4, 2011.

- ^ "Education". Wichita Metro Chamber of Commerce. Archived from the original on January 19, 2011. Retrieved February 4, 2011.

- ^ "2010-2011 School Directory". Roman Catholic Diocese of Wichita. Archived from the original on March 18, 2011. Retrieved February 4, 2011.

- ^ "Classes". Bethany Lutheran School. Retrieved February 4, 2011.

- ^ "Welcome to Holy Cross Lutheran School". Holy Cross Lutheran School. Retrieved February 4, 2011.

- ^ "Three Angels School". Three Angels Seventh-day Adventist Church. Archived from the original on July 28, 2011. Retrieved February 4, 2011.

- ^ "Wichita Adventist Christian Academy". Wichita Adventist Christian Academy. Retrieved February 4, 2011.

- ^ "Private Schools" (PDF). Wichita Metro Chamber of Commerce. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 25, 2010. Retrieved February 4, 2011.

- ^ "Wichita State University". College Portraits of Undergraduate Education. Retrieved February 5, 2011.

- ^ "College Comparison Tool". U.S. News & World Report. Archived from the original on January 6, 2011. Retrieved February 5, 2011.

- ^ "Satellite Campuses". Wichita State University. Archived from the original on October 17, 2015. Retrieved February 5, 2011.

- ^ "Friends Fact Sheet". Friends University. Retrieved February 5, 2011.

- ^ "2010-11 Admission Brochure". Newman University. p. 5. Retrieved February 5, 2011.

- ^ "School of Medicine". KU Medical Center. Retrieved February 5, 2011.

- ^ "Education". Wichita Metro Chamber of Commerce. Archived from the original on January 19, 2011. Retrieved February 5, 2011.

- ^ "McConnell Campus". Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University. Archived from the original on July 19, 2011. Retrieved February 5, 2011.

- ^ "Heritage College-Wichita". College Navigator. National Center for Education Statistics. Retrieved February 5, 2011.

- ^ "ITT Technical Institute-Wichita". College Navigator. National Center for Education Statistics. Retrieved February 5, 2011.

- ^ "Wichita Eagle". Mondo Times. Retrieved January 15, 2011.

- ^ Tanner, Beccy (May 29, 2016). "History of the Wichita Eagle". The Wichita Eagle. Retrieved February 12, 2021.

- ^ "Wichita Business Journal". Mondo Times. Retrieved January 15, 2011.

- ^ "Wichita Kansas Newspapers". Mondo Newspapers. Retrieved October 24, 2014.

- ^ "Voice It Wichita.com". TCV Publishing. Retrieved October 24, 2014.

- ^ Horwath, Bryan in "Hispanic community could be sleeping giant for Wichita economy," March 09, 2016, Wichita Eagle

- ^ Associated Press in "Communications firms cater to Wichita's Hispanic market," May 25, 2003, Lawrence Journal-World

- ^ "Liberty Press". Mondo Times. Retrieved January 15, 2011.

- ^ "Backstory". SplurgeMag. Retrieved October 24, 2014.

- ^ "About Us". The Sunflower. October 13, 2008. Archived from the original on July 1, 2007. Retrieved January 15, 2011.

- ^ "2009 Arbitron Radio Metro Map" (PDF). Arbitron. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 20, 2011. Retrieved March 14, 2012.

- ^ "Radio Stations in Wichita, Kansas". Radio-Locator. Retrieved November 17, 2016.

- ^ "TV Market Maps - Kansas". EchoStar Knowledge Base. Archived from the original on July 26, 2011. Retrieved July 28, 2013.

- ^ "Contact Us". KAKE. Archived from the original on August 17, 2011. Retrieved January 9, 2011.

- ^ "About Us - kwch.com". KWCH. Archived from the original on July 13, 2011. Retrieved January 9, 2011.

- ^ "About KSCW". KSCW-DT. Archived from the original on October 24, 2013. Retrieved January 9, 2011.

- ^ "Contact Us - Fox Kansas". KSAS. Archived from the original on January 2, 2013. Retrieved January 9, 2011.

- ^ "Contact Us - myTVwichita". KMTW. Archived from the original on July 14, 2011. Retrieved January 9, 2011.

- ^ "Contact Us - KSN TV". KSN. Archived from the original on March 8, 2013. Retrieved January 9, 2011.

- ^ "Contact Us". KPTS. Archived from the original on December 20, 2010. Retrieved January 9, 2011.

- ^ "Wichita-Hutchinson Television Stations". Station Index. Retrieved January 9, 2011.

- ^ Tanner, Beccy (August 11, 2013). "Ad Astra: Idea for Big Ditch grew after Wichita had sustained series of major floods". kansas.com. The Wichita Eagle. Retrieved March 24, 2015.

- ^ "Storm Water Management". City of Wichita. Archived from the original on February 19, 2011. Retrieved January 1, 2011.

- ^ "Wichita and Valley Center Local Protection Project". United States Army Corps of Engineers. Archived from the original on September 27, 2011. Retrieved January 1, 2011.

- ^ "Flood-control ditch needs $6M in repairs". Lawrence Journal World. Associated Press. Retrieved March 24, 2015.

- ^ "Big Ditch Renamed In Honor Of Man Credited For Saving Wichita". KWCH TV. July 3, 2019.

- ^ "History". Evergy. Retrieved October 24, 2021.

- ^ "About Us". Kansas Gas Service. Archived from the original on August 14, 2018. Retrieved August 13, 2018.

- ^ "Public Works & Utilities". City of Wichita, Kansas. Retrieved August 13, 2018.

- ^ "Trash in Sedgwick County". Sedgwick County, Kansas. Retrieved August 13, 2018.

- ^ "Summary of Cable TV Providers in Wichita, KS". CableTV.com. Retrieved August 13, 2018.

- ^ "Summary of Wichita Internet Providers". HighSpeedInternet.com. Retrieved August 13, 2018.

- ^ "Via Christi hospitals". Via Christi Health. Retrieved August 10, 2018.

- ^ "Locations – KS". Hospital Corporation of America. Retrieved August 10, 2018.

- ^ Quickfacts: Wichita City, Kansas U.S. Census.

- ^ "Wichita Transit". City of Wichita. Archived from the original on January 14, 2011. Retrieved January 8, 2011.

- ^ Christie, Les (June 13, 2007). "New Yorkers are top transit users". CNNmoney.com. Retrieved June 29, 2007.

- ^ info@beeline-express.com, beeline-express. "Beeline Express". www.beeline-express.com.

- ^ "Home". www.greyhound.com. Archived from the original on September 6, 2019. Retrieved January 3, 2016.

- ^ "Greyhound relocating to city's downtown transit station".

- ^ a b "Mid-Continent Airport History". Wichita Airport Authority. Archived from the original on December 15, 2010. Retrieved January 9, 2011.

- ^ "Airline Information". Wichita Airport Authority. Archived from the original on December 15, 2010. Retrieved January 9, 2011.

- ^ "KAAO - Colonel James Jabara Airport". AirNav.com. Retrieved January 9, 2011.

- ^ "KCEA - Cessna Aircraft Field Airport". AirNav.com. Retrieved January 9, 2011.

- ^ "KBEC - Beech Factory Airport". AirNav.com. Retrieved January 9, 2011.

- ^ "K32 - Riverside Airport". AirNav.com. Retrieved January 9, 2011.

- ^ "71K - Westport Airport". AirNav.com. Retrieved January 9, 2011.

- ^ a b "Getting Around the Metro Area". Wichita Metro Chamber of Commerce. Archived from the original on January 19, 2011. Retrieved January 9, 2010.

- ^ "UPRR Common Line Names". Union Pacific Railroad. Retrieved January 9, 2011.

- ^ "Kansas Operating Division" (PDF). BNSF Railway. April 1, 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 25, 2011. Retrieved January 9, 2011.

- ^ "Rail Plan 2005-2006" (PDF). Kansas Department of Transportation. pp. 66–67. Retrieved January 9, 2011.

- ^ Wistrom, Brent (January 11, 2010). "Proposed Amtrak line would mean millions for Wichita". USA Today. Archived from the original on November 26, 2011. Retrieved January 9, 2011.

- ^ "Thruway Bus Connection ties two Amtrak routes together through Wichita". Amtrak. April 18, 2016. Retrieved March 7, 2017.

- ^ "City and Neighborhood Rankings". Walk Score. 2014. Retrieved February 16, 2015.

- ^ "Wichita-Sedgwick County Planning Wichita Bicycle Master Plan". www.wichita.gov. Retrieved January 1, 2019.

- ^ "Wichita builds on bike-friendly status". kansas. Retrieved January 1, 2019.

- ^ "Award Database" (PDF). League of American Wheelmen. 2017. Retrieved January 1, 2019.

- ^ a b c d Bing, Bonnie, "Successful Wichita natives praise their schooling here," Feb.26, 2012, Wichita Eagle, retrieved April 3, 2017.

- ^ "GLICKMAN, Daniel Robert (1944-)", Biographical Information, Bioguide, U.S. Congress official website, retrieved April 3, 2017.

- ^ "Wichita Sister Cities". City of Wichita. Retrieved July 25, 2018.

- ^ "Wichita Sister Cities". City of Wichita. Retrieved August 11, 2018.

- ^ "Jumelages et Relations Internationales - Avignon" [Twinning and International Relations - Avignon]. Avignon.fr (in French). Archived from the original on July 16, 2013. Retrieved July 13, 2013.

- ^ "Atlas français de la coopération décentralisée et des autres actions extérieures" [French Atlas of Decentralized Cooperation and Other External Actions]. Ministère des affaires étrangères – French Ministry of Foreign Affairs (in French). Archived from the original on February 26, 2013. Retrieved July 13, 2013.

- ^ "Interactive City Directory". Sister Cities International. Archived from the original on March 1, 2016. Retrieved December 14, 2018.

Further reading

- Wichita : Illustrated History 1868 to 1880; Eunice S. Chapter; 52 pages; 1914. (Download 3MB PDF eBook)

- History of Wichita and Sedgwick County Kansas : Past and present, including an account of the cities, towns, and villages of the county; 2 Volumes; O.H. Bentley; C.F. Cooper & Co; 454 / 479 pages; 1910. (Volume1 - Download 20MB PDF eBook), (Volume2 - Download 31MB PDF eBook)

External links

- City

- City of Wichita

- Wichita - Directory of Public Officials

- Wichita Metro Chamber of Commerce

- Greater Wichita Convention & Visitors Bureau

- Historical

- Wichita Photo Archives - Wichita State University

- Discover Historic Wichita, Brochure with Map / List / Photos / Description of 121 Registered Historic Landmarks

- Historic photos of Wichita African-American community on YouTube, from Hatteberg's People on KAKE TV news

- Map

- Wichita city map, KSDOT