뉴욕주 유티카

Utica, New York우티카 언데이지 (모호크) | |

|---|---|

도시 | |

| 닉네임: 악수도시, 신시, 느릅나무도시[1] | |

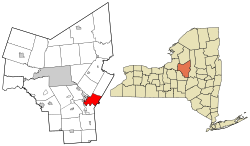

뉴욕 오네이다 카운티의 유티카와 뉴욕 주 오네이다 카운티의 위치 | |

| |

| 좌표 : 43°06'03 ″N 75°13′57″W / 43.10083°N 75.23250°W | |

| 나라 | 미국 |

| 주 | 뉴욕 |

| 지역 | 뉴욕 중부; 모호크 계곡 |

| 메트로 | 우티카-로마 |

| 자치주 | 오네이다 |

| 토지교부금(마을) | 1734년 1월 2일 ([2] |

| 편입(마을) | 1798년 4월 3일 ([3] |

| 편입(도시) | 1832년 2월 13일 ([4] |

| 정부 | |

| • 활자 | 강력한 시장협의회 |

| • 시장 | 로버트 M. 팔미에리 (D) |

| 지역 | |

| • 도시 | 16.98 sq mi (43.97 km2) |

| • 육지 | 16.72 sq mi (43.31 km2) |

| • 물 | 0.26 sq mi (0.66 km2) |

| 승진 | 456 ft (139 m) |

| 인구. (2020) | |

| • 도시 | 65,283 |

| • 밀도 | 3,904.02/sq mi (1,507.33/km2) |

| • 어반 | 117,328 (U.S.: 268th)[7] |

| • 메트로 | 297,592 (U.S.: 163rd)[6][a] |

| 디모닉 | 우티칸 |

| 시간대 | UTC-5(동부 표준시) |

| • 여름(DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP 코드 | 13501-13505, 13599 |

| 지역코드 | 315 |

| FIPS 코드 | 36-76540 |

| GNIS 피쳐 ID | 0968324[8] |

| 웹사이트 | cityofutica.com |

유티카(Utica, ˈ주 ː트 ɪ크 ə/)는 미국 뉴욕주 오네이다 군의 군청 소재지이며 모호크 계곡에 위치한 도시입니다. 뉴욕주에서 10번째로 인구가 많은 도시로, 2020년 미국 인구 조사에서 인구는 65,283명이었습니다.[9] 앨버니에서 북서쪽으로 약 153km, 시라큐스에서 동쪽으로 약 55m, 뉴욕시에서 북서쪽으로 약 240m 떨어져 있습니다. 우티카와 인근 도시인 로마는 우티카-로마 메트로폴리탄 통계 지역의 닻을 올렸습니다.

이전에는 이로쿼이 연방의 모호크 국가가 거주했던 강 정착지였던 유티카는 미국 독립 혁명 기간과 이후에 뉴잉글랜드에서 유럽계 미국인 정착민들을 끌어 모았습니다. 19세기에는 이민자들이 이리 운하와 체낭고 운하, 뉴욕 중앙 철도를 통해 알바니와 시라큐스 사이의 중간 기착지로서의 입지를 강화했습니다. 19세기와 20세기 동안 도시의 기반 시설은 제조업 중심지로서의 성공에 기여했고 섬유 산업의 전 세계적인 중심지로서의 역할을 정의했습니다.

다른 러스트벨트 도시들처럼, 유티카는 20세기 중반 내내 경기 침체를 겪었습니다. 경기 침체는 오프쇼어링과 섬유 공장의 폐쇄로 인한 산업 쇠퇴, 교외와 시라큐스로의 일자리와 기업의 이전으로 인한 인구 감소, 사회 경제적 스트레스와 침체된 조세 기반과 관련된 빈곤으로 구성되었습니다. 생활비가 저렴한 이 도시는 전 세계 전쟁으로 폐허가 된 나라에서 온 난민들의 용광로가 되어 대학과 대학, 문화 기관 및 경제의 성장을 촉진하고 있습니다.[10]

어원

최초의 유티카는 현대 튀니지의 이전 도시였습니다. 뉴욕의 많은 중심지들은 고대 도시나 사람들(로마, 시라큐스, 이타카, 트로이, 호머, 키케로, 오비드 등)의 이름을 가지고 있습니다.

고대 유티카라는 이름을 현대적인 마을, 당시 도시에 다시 사용한 것은 수 년 동안 킹스 칼리지(오늘날 컬럼비아 대학교)의 교수였던 고전적으로 훈련된 측량사 로버트 하퍼(1731–1825)에게 많은 빚을 지고 있습니다. 뉴욕주 중심의 고전적인 이름을 발표한 사람은 그였고, 그는 자신이 마을 이름을 유티카라고 지었다고 진술했습니다.[11] 그러나 또 다른 설에는 1798년 백스 선술집(마을을 지나는 여행객들의 휴식처)에서 13가지 제안을 담은 모자에서 이름을 따온 모임이 포함되어 있습니다. 궁극적으로 하르푸르 때문은 아닐지라도, 어떻게 우티카가 그들 중에 있게 되었는지는 알려지지 않았습니다.[11][12][13][14]

역사

이로쿼이(Haudenosaunee)와 식민지 정착지

유티카는 프랑스와 7년 전쟁의 북미 전선이었던 프랑스와 인도 전쟁 중인 1758년 미국 식민지 개척자들이 방어를 위해 세운 올드 포트 슐러 부지에 세워졌습니다.[3][15][16][17] 이 요새가 건설되기 전에, 이로쿼이 연합의 모호크, 오논다가, 오네이다 국가들은 기원전 4000년에 오대호 남동쪽 지역을 지배했습니다.[18] 모호크족은 동부와 하부 모호크 계곡에서 가장 크고 강력한 국가였습니다. 식민지 주민들은 총기와 럼주를 교환하는 대가로 모호크족과 오랜 기간 모피 무역을 했습니다. 이로쿼이 국가들은 이 지역에서 압도적인 존재로 인해 뉴욕주가 모호크 계곡의 한가운데를 지나 미국의 독립전쟁 승리 이후까지 확장되지 못했습니다. 전쟁이 끝난 후 몇몇 이로쿼이 국가들은 패배로 인해 영국 동맹국들과 전쟁 후에 필요한 피난처와 보급품을 교환하는 미국 동맹국들로 뉴욕으로 땅을 내주어야 했습니다.[18]

올드 포트 슈일러를 수용하는 토지는 1734년 1월 2일 조지 2세가 뉴욕 주지사 윌리엄 코스비에게 수여한 2만 에이커(81km2)의 습지의 일부였습니다.[19] 요새는 여러 산책로(Great Indian Warpath 포함) 근처에 위치해 있었기 때문에, 모호크 강의 얕은 부분에 있는 굽은 곳에 위치해 있어 중요한 요충지가 되었습니다.[20][21] 모호크족은 굽은 길을 언다이지(언다이지, "언다이지")라고 부르는데, 이 이름은 현재 도시의 도장에 표시되어 있습니다.[12][22]

미국 독립 전쟁 동안, 영국과 동맹을 맺은 이로쿼이 부족들의 국경 습격은 국경의 정착민들을 힘들게 했습니다. 조지 워싱턴은 설리번 원정대 레인저스에게 중부 뉴욕으로 들어가 이로쿼이의 위협을 진압하라고 명령했습니다. 40개 이상의 이로쿼이 마을이 겨울 가게와 함께 파괴되어 기아를 일으켰습니다.[12] 전쟁의 여파로 수많은 식민지 정착민들이 뉴잉글랜드,[23] 특히 코네티컷에서 뉴욕 지역으로 이주했습니다.[12]

1794년에 주 도로인 Genesee Road가 Utica에서 Genesee River로 서쪽으로 만들어졌습니다. 그 해 모호크 턴파이크 및 브리지 회사에 북동쪽으로 올버니까지 도로를 연장하는 계약이 체결되었고, 1798년에 연장되었습니다.[3][24] 세네카 턴파이크는 낡아빠진 오솔길을 포장도로로 대체하며 유티카 개발의 핵심이었습니다.[25] 이 마을은 상품과 뉴욕 서부를 오가며 오대호를 오가는 많은 사람들을 위한 모호크 강을 따라 휴식과 공급 지역이 되었습니다.[26][27]

유티카의 편입

유티카 마을의 경계는 1798년 4월 3일 뉴욕 주 의회에 의해 통과된 법안에서 정의되었습니다.[28] 유티카는 이후 1805년과 1817년에 국경을 넓혔습니다. 1805년 4월 5일 마을의 동쪽과 서쪽 경계가 확장되었고,[29] 1817년 4월 7일 우티카는 서쪽의 화이트타운에서 분리되었습니다.[3][30] 1825년 이리 운하가 완공된 후, 이 도시의 성장은 다시 자극을 받았습니다. 유티카는 많은 신문들이 있는 인쇄와 출판의 중심지가 되었습니다.[31]

시헌장은 1832년 2월 13일 주 의회에서 통과되었습니다.[3][4] 1845년 미국 인구 조사에 따르면 우티카는 미국에서 29번째로 큰 도시로 선정되었습니다.[32][33]

산업과 무역

Erie와 Chenango 운하 위에 있는 Utica의 위치는 산업 발전을 촉진하여 지역 제조와 유통을 위해 펜실베니아 북동부에서 무연탄을 운송할 수 있게 했습니다.[34] 우티카의 경제는 가구, 중기계, 직물, 목재 제조업을 중심으로 이루어졌습니다.[35] 1807년 금수법과 지방 투자의 효과가 결합되어 섬유 산업이 더욱 확대될 수 있었습니다.[36]

운하 외에도 유티카의 교통은 도시를 관통하는 철도에 의해 강화되었습니다. 첫 번째는 모호크와 허드슨 철도로, 1833년에 유티카와 셰넥타디 철도가 되었습니다. Schenectady와 Utica 사이의 78 mi (126 km)의 연결은 Mohawk and Hudson River 철도가 이전에 사용했던 도로권으로부터 1836년에 개발되었습니다.[37][38] 시라큐스 철도와 유티카 철도와 같은 후대의 노선들은 유티카 철도와 셰넥타디 철도와 합쳐져서 19세기에 아디론댁스의 삼림 철도로 시작된 뉴욕 센트럴 철도를 형성했습니다.[39]

1800년대 초, William Williams와 그의 파트너는 Genesee Street에 있는 그들의 인쇄소로부터 Utica의 첫 번째 신문인 The Utica Club을 발행했습니다. 1817년에 윌리엄스는 또한 유티카의 첫 번째 디렉토리를 출판했습니다.[40][41] 유티카는 많은 신문들이 있는 인쇄와 출판의 중심지가 되었습니다.[42]: 18

폐지론

1850년대에 유티카는 650명 이상의 도망 노예들을 도왔습니다. 유티카는 지하 철도의 역으로서 중요한 역할을 했습니다. 그 도시는 남부 티어에서 알바니, 시라큐스, 로체스터를 거쳐 캐나다로 가는 노예 탈출로에 있었습니다.[43][44] 해리엇 터브먼이 버팔로로 이동할 때 사용한 [45]이 경로는 노예들이 캐나다로 가는 도중 뉴욕 중앙 철도의 우티카를 통과하도록 안내했습니다.[45] 유티카는 1830년대와 1840년대에 감리교 설교자인 오렌지 스콧의 노예 반대 설교의 장소였고, 스콧은 1843년에 그곳에서 폐지론자 그룹을 형성했습니다.[44] 베리아 그린은 1835년 뉴욕 노예 반대 협회의 첫 회의를 유티카에서 조직했는데, 이 회의는 지역 하원의원 새뮤얼 비어들리와 다른 "유명한 시민들"에 의해 주도된 폐지론자 폭도들에 의해 방해를 받았습니다.[46] (그것은 뉴욕 근처의 피터보로에 있는 게릿 스미스의 집으로 휴회되었습니다.)[47][48][49]

20세기

20세기 초에는 뉴욕 센트럴이 1907년 웨스트 쇼어 도시간 노선을 위해 시라큐스에서 시라큐스까지 49마일(79km)의 선로를 전철화하면서 유티카에 철도 발전을 가져왔습니다.[50] 1902년, 유티카와 모호크 계곡 철도는 유티카를 통과하는 37.5 마일(60.4 km)의 전철 노선으로 로마와 리틀 폴스를 연결했습니다.[51]

이탈리아, 아일랜드, 폴란드 및 레바논 마론계 이민자들의 물결은 20세기 초에 도시 산업에서 일했습니다. 1919년, 고용된 유티칸들의 3분의 2가 섬유 산업에서 일했습니다. 제1차 세계 대전 이후 미국 북부의 섬유 산업은 공장들이 미국 남부로 이전하면서 급속히 쇠퇴했습니다. 직물은 1947년까지 유티카에서 선두적인 산업으로 남아 있었고, 남아있는 몇 안 되는 공장에서 4분의 1 미만의 노동자를 고용했습니다.

일찍이 1928년에 상공회의소는 우티카의 산업 기반을 다양화하려고 했습니다. 지역 노동 문제와 국가 추세에 자극을 받은 유티카의 공화당 정치 기관은 쇠퇴했고 주지사 프랭클린 D(이후 대통령)의 지지를 받아 루퍼스 엘레판테(Rufus Elefante)가 이끄는 민주당 기관으로 대체되었습니다. 루즈벨트. 민주 정치 지도자들은 현대 산업을 유티카에 끌어들이기 위해 지역 기업 이익에 협력했습니다. 제너럴 일렉트릭, 시카고 공압, 벤딕스 에어비에이션, 유니백 등이 유티카에 공장을 설립했습니다. 유티카 칼리지와 모호크 밸리 커뮤니티 칼리지를 설립하여 숙련된 노동자를 제공하고, 오네이다 카운티 공항을 건설하여 운송을 제공했습니다. 도시는 또한 슬럼가 청소와 자동차를 수용하기 위한 거리와 인근을 현대화하는 등 주거 재개발을 겪었습니다. 1940~1950년대에 걸친 유티카 역사의 시기를 '붐이 일다' 시대라고 부르기도 합니다. 그것이 뉴 하트포드와 화이트타운의 교외 지역의 성장으로 이어졌지만, 유티카의 인구는 이 시대 동안 평평했고 실업률은 지속적으로 증가했습니다.[52][53]

10년 동안 다른 미국 도시들과 마찬가지로, 정치적 부패, 악덕, 그리고 조직적인 범죄와 관련된 추문들이 Utica의 명성을 실추시켰습니다.[54][55][56] 엘레판테와 그의 내관들이 조직적인 범죄에 적극적으로 가담했는지 아니면 단순히 그것을 외면했는지는 여전히 불분명합니다. 1957년 미국 마피아 지도자들의 애팔라친 회의에 3명의 유티칸 마피아들이 참석한 것으로 보고된 후 유티카에서 조직범죄가 전국적인 주목을 받았습니다.[57] 뉴욕 저널 아메리칸(New York Journal American)은 유티카(Utica)를 "동쪽의 신 시티([58]Sin City of the East)"라고 불렀고, 저널 아메리칸(Journal American)과 뉴스위크(Newsweek)와 같은 소식통의 보도는 유티카에게 마피아 활동으로 전국적인 명성을 가져다 주었습니다. Look 잡지와 같은 다른 언론 매체뿐만 아니라 지역 기업 이익은 이러한 보도가 과장되었으며, 유티카의 부패와 범죄는 유사한 미국 도시에서 발생한 것보다 더 나쁘지 않다고 주장했습니다.[59] 1959년, 그 스캔들은 도시 직원들과 공무원들에 대한 범죄 수사로 끝이 났습니다: 많은 사람들이 성매매, 도박, 사기, 음모와 관련된 혐의로 체포되었고, 다른 사람들은 사임하도록 강요 받았습니다.[60] Utica Daily Press and Utica Obser-Dispatch는 지역 부패에 대한 조사로 1959년 퓰리처상 공공 서비스상을 수상했습니다. 엘레판테의 기계는 지배력을 잃었습니다. Utica의 조직적인 범죄는 축소되었지만 1970년대 후반에 부활했습니다. 1930년대부터 존재해온 지역 마피아는 1989년 버팔로 범죄 가족의 지역 동료들을 기소하면서 끝이 났습니다.[56][61][62]

다른 러스트벨트 도시에서 일어난 탈산업화의 영향을 강하게 받은 유티카는 20세기 후반 동안 제조업 활동이 크게 감소했습니다. 나머지 섬유 공장들은 계속해서 남부의 경쟁자들에 의해 잘려 나갔습니다.[63] 1954년 뉴욕주 고속도로가 개통되고 이리 운하와 미국 전역의 철도에 대한 활동이 감소한 것도 지역 경제가 좋지 않은 원인이 되었습니다.[64] 1980년대와 1990년대에 제너럴 일렉트릭(General Electric)과 록히드 마틴(Lockheed Martin)과 같은 주요 고용주들은 유티카(Utica)와 시라큐스(Saracuars)의 공장을 폐쇄했습니다.[65][66] 일부 Utica 기업들은 더 크고 교육을 많이 받은 인력들과 함께 인근 시라큐스로 이전했습니다.[67] 뉴욕시 외곽에서 도시 인구가 감소하는 주 전체적인 추세를 반영하여 카운티의 인구가 증가하는 동안 Utica의 인구는 감소했습니다.[68] 1974년부터 1978년까지, 1996년부터 2000년까지 재임한 괴짜 포퓰리즘 시장 에드 한나는 전국 언론의 주목을 받았지만 유티카의 쇠퇴를 막을 수 없었습니다.[69]

21세기

유티카의[70][71] 낮은 생활비는 전 세계에서 온 이민자들과 난민들을 끌어 모았습니다.[72][73][74] 유티카에서 가장 큰 난민 집단은 보스니아 전쟁 이후 4,500명의 난민이 재정착했고, 미얀마의 카렌족은 4,000명 정도가 재정착했습니다.[75][76] Utica는 또한 구소련, 동남아시아, 아프리카, 중동 및 다른 곳에서 온 난민들의 상당한 공동체를 가지고 있습니다. 2005년과 2010년 사이에 유티카의 인구는 수십 년 만에 처음으로 증가했는데, 이는 주로 난민 정착 때문입니다. 2015년 유티카 인구의 약 4분의 1이 난민이었고, 43개 언어가 도시 학교에서 사용되었습니다.[77] 유엔난민고등판무관은 2005년 우티카를 "난민을 사랑하는 마을"로 묘사했지만, 때때로 차별 문제가 발생했습니다. 2016년 우티카 시 교육구는 난민 학생들이 고등학교에 다니는 것이 제외되었다는 소송을 해결했습니다.[78][79][80]

이민의 활성화 효과에도 불구하고, Utica는 높은 빈곤율과 줄어든 세금으로 계속 어려움을 겪고 있으며, 학교와 공공 서비스에 악영향을 미치고 있습니다.[81][82] 지역 경제 활성화를 위한 지역, 지역 및 주 전체의 경제적 노력이 제안되었습니다.[83][84] 2010년에 이 도시는 반세기 이상 만에 처음으로 종합적인 마스터 플랜을 개발했습니다.[85][86] 10년간의 지연과 잘못된 출발 끝에, 2022년 반도체 제조업체 울프스피드(Wolfspeed)가 유티카(Utica) 바로 북쪽의 마시(Marcy)에 공장을 열면서 이 지역에 나노 기술 센터를 설립하려는 계획이 결실을 맺었습니다.[87][88] 2023년 10월, 유티카 시내에 새로운 병원이 문을 열면서 기존 유티카의 두 병원을 대체하게 되었습니다.[89][90]

지리학

미국 인구조사국에 따르면, Utica의 총 면적은 17.02 평방 마일 (44.1 km2) – 16.76 평방 마일 (43.4 km2)의 땅과 0.26 평방 마일 (0.67 km2)의 물을 가지고 있습니다.[91] 이 도시는 뉴욕의 지리적 중심에 위치하고 있으며, 허키머 카운티의 서쪽 경계와 인접해 있으며, 아디론댁 산맥의 남서쪽 기슭에 위치하고 있습니다.[92] 유티카와 그 교외 지역은 남쪽의 알레게니 고원과 북쪽의 아디론댁 산맥에 의해 경계를 이루고 있으며,[93] 이 도시의 해발고도는 456피트(139m)이며, 이 지역은 모호크 계곡(Mohawk Valley)으로 알려져 있습니다. 이 도시는[94] 올버니에서 북서쪽으로 90마일(145km), 시라큐스에서 동쪽으로 45마일(72km) 떨어져 있습니다.[95]

지형

이 도시의 이름인 "언다지즈"는 북쪽의 디어필드 언덕에서 볼 때 도시의 높은 위치를 따라 흐르는 모호크 강의 굴곡을 의미합니다.[20] 이리 운하와 모호크 강은 북부 유티카를 통과합니다. 시내 북서쪽에는 다양한 동물과 식물, 새들이 있는 이리 운하와 모호크 강 사이의 소규모 습지 집단인 유티카 습지가 있습니다.[96][97] 1850년대에 도시를 둘러싸고 있는 습지대를 통해 플랭크 도로가 건설되었습니다.[98] 유티카의 교외에는 도시보다 언덕과 절벽이 더 많습니다. 모호크 계곡(Mohawk Valley)이 넓은 범람원을 형성하는 곳에 위치한 이 도시는 전반적으로 경사진 평평한 지형을 가지고 있습니다.[92]

도시경관

유티카의 건축 양식은 버팔로, 로체스터, 시라큐스의 유사한 지역에서도 볼 수 있는 그리스 부흥, 이탈리아 부흥, 프랑스 르네상스,[100] 고딕 부흥,[99] 신고전주의를 포함한 많은 양식을 특징으로 합니다. 현대적인 1972년식 유티카 스테이트 오피스 빌딩은 17층에 높이가 227피트(69m)에 이 도시에서 가장 높습니다.[101]

유티카가 마을이었을 때 펼쳐진 거리는 19세기와 20세기 후반에 지어진 거리보다 더 많은 불규칙성을 가지고 있었습니다. 도시의 위치 때문에 (모호크 강에 인접한) 많은 거리가 강과 평행하기 때문에 동서나 남북으로 엄격하게 운행되지 않습니다. 우티카의 초기 전기 철도 시스템의 잔해는 철도가 거리에 설치된 서부와 남부 지역에서 볼 수 있습니다.[20][102][103]

동네

유티카의 지역은 역사적으로 주민들에 의해 정의되어 왔으며, 그들이 자신만의 개성을 개발할 수 있도록 해주었습니다. 인종 및 민족, 사회적 및 경제적 분리, 기반 시설 및 새로운 교통 수단의 개발로 인해 지역이 형성되었으며 결과적으로 그룹이 그들 사이에서 이동했습니다.[33]

웨스트 우티카(West Utica)는 역사적으로 독일, 아일랜드, 폴란드 이민자들의 고향이었습니다. 도심에 위치한 콘힐 지역은 유대인 인구가 매우 많았습니다.[104] 이스트 우티카(East Utica)는 이탈리아 이민자들이 지배하는 문화적, 정치적 중심지입니다.[105][106] 시내 북쪽에는 이전에 이 도시의 아프리카계 미국인과 유대인 인구가 거주했던 트라이앵글(Triangle) 지역이 있습니다.[33] 이전에 하나 이상의 그룹이 지배하던 지역에는 이전 이탈리아 지역의 보스니아인과 라틴 아메리카인, 그리고 역사적으로 웨일스 지역인 콘 힐과 같은 다른 그룹이 도착했습니다.[33] 백 기념 공원과 백의 스퀘어 웨스트(유티카의 역사적 중심지)는 도심의 북동쪽에 있으며, 서쪽에는 제네시 거리, 남쪽에는 오리스카니 거리가 있습니다.[100]

역사적 장소

다음은 국가 사적지에 등재되어 있습니다.[107][108][109][110][111][112]

- 알렉산더 피르니 연방 빌딩

- 바이링턴 밀 (Frisbie & Stansfield Knitting Company)

- 칼바리 성공회

- 로스코 콘클링 하우스

- 도일 하드웨어 빌딩

- 디어필드 최초의 침례교회

- 제1장로회

- 포트 슈일러 클럽 빌딩

- 글로브 모직 회사 밀스

- 그레이스 처치

- 존 C. 히베르 빌딩

- 허드 & 피츠제럴드 빌딩

- 로어제네시 스트리트 역사지구

- 성십자가 기념 교회

- 밀레-휠러 하우스

- 문슨윌리엄스프로터예술원

- 뉴 센추리 클럽

- 뤼트거슈테벤 공원 역사지구

- 성 요셉 교회

- 스탠리 극장

- 성막 침례교회

- 유니언 스테이션

- 업타운 극장

- Utica Armory

- 우티카 데일리 프레스 빌딩

- 유티카 공원과 파크웨이 역사지구

- 유티카 정신병원

- 유티카 공공도서관

- 존 G 장군. 위버 하우스

- 포리스트힐 묘지

기후.

우티카(Utica)는 습한 대륙성 기후(또는 따뜻한 여름 기후: Köppen Dfb)로 겨울은 춥고 여름은 온화한 [113][114]것이 특징입니다. 여름 최고 기온은 화씨 77 ~ 81 °F (25 ~ 27 °C)입니다.[114] 이 도시는 USDA 식물 경화 구역 5a에 있으며 토종 식물은 -10 ~ -20 °F (-23 ~ -29 °C)의 온도를 견딜 수 있습니다.[115]

겨울은 춥고 눈이 많이 내립니다; 유티카는 이리호와 온타리오호로부터 호수효과 눈을 받습니다.[116][117][118] 유티카는 계곡에 위치하고 북풍에 취약하기 때문에 다른 오대호 도시들보다 평균적으로 더 춥습니다.[119] 겨울 밤에 화씨 영하 또는 영하의 온도는 드물지 않습니다. 연평균 강수량(1981년부터 2010년까지 30년 평균 기준)은 45.7인치(116cm)로 평균 175일이 내립니다.[120]

| 유티카(로마, 뉴욕)의 기후 데이터 (1991–2020 정상,[b] 극단 1961–현재) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 달 | 얀 | 2월 | 마르 | 4월 | 그럴지도 모른다 | 준 | 줄 | 8월 | 9월 | 10월 | 11월 | 12월 | 연도 |

| 최고 °F(°C) 기록 | 67 (19) | 72 (22) | 83 (28) | 91 (33) | 93 (34) | 97 (36) | 99 (37) | 96 (36) | 93 (34) | 85 (29) | 78 (26) | 71 (22) | 99 (37) |

| 평균 최고 °F(°C) | 30.1 (−1.1) | 31.8 (−0.1) | 41.0 (5.0) | 54.9 (12.7) | 68.9 (20.5) | 76.2 (24.6) | 80.9 (27.2) | 79.3 (26.3) | 72.0 (22.2) | 58.9 (14.9) | 46.8 (8.2) | 35.7 (2.1) | 56.4 (13.6) |

| 일평균 °F(°C) | 21.5 (−5.8) | 22.5 (−5.3) | 31.7 (−0.2) | 44.5 (6.9) | 56.8 (13.8) | 65.3 (18.5) | 70.2 (21.2) | 68.7 (20.4) | 61.4 (16.3) | 49.7 (9.8) | 39.0 (3.9) | 28.3 (−2.1) | 46.6 (8.1) |

| 평균 낮은 °F(°C) | 12.9 (−10.6) | 13.2 (−10.4) | 22.5 (−5.3) | 34.1 (1.2) | 44.7 (7.1) | 54.5 (12.5) | 59.5 (15.3) | 58.1 (14.5) | 50.9 (10.5) | 40.5 (4.7) | 31.2 (−0.4) | 20.9 (−6.2) | 36.9 (2.7) |

| 낮은 °F(°C) 기록 | −31 (−35) | −28 (−33) | −16 (−27) | 5 (−15) | 24 (−4) | 32 (0) | 43 (6) | 35 (2) | 27 (−3) | 16 (−9) | −4 (−20) | −21 (−29) | −31 (−35) |

| 평균 강수량 인치(mm) | 2.50 (64) | 2.37 (60) | 3.43 (87) | 3.72 (94) | 4.46 (113) | 4.20 (107) | 4.25 (108) | 3.60 (91) | 3.95 (100) | 4.67 (119) | 3.72 (94) | 2.95 (75) | 43.82 (1,113) |

| 평균 적설 인치(cm) | 31.7 (81) | 23.4 (59) | 15.1 (38) | 3.4 (8.6) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.1 (0.25) | 7.3 (19) | 20.8 (53) | 101.8 (259) |

| 평균강수일수(≥ 0.01 in) | 12.9 | 14.2 | 13.2 | 15.5 | 14.9 | 14.0 | 13.1 | 13.7 | 13.4 | 17.1 | 15.7 | 17.0 | 174.7 |

| 평균 눈 오는 날(≥ 0.1인치) | 15.9 | 11.7 | 8.2 | 2.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 4.2 | 13.5 | 56.7 |

| 평균 상대습도(%) | 66.0 | 66.2 | 65.0 | 64.1 | 63.3 | 66.8 | 66.0 | 68.2 | 72.7 | 69.8 | 72.3 | 72.3 | 67.9 |

| 가능한 일조량 백분율 | 42 | 46 | 52 | 58 | 64 | 66 | 65 | 60 | 54 | 48 | 43 | 40 | 53 |

| 출처 1: NOAA(1981-2010),[121][122][123] 서부 지역 센터[124] | |||||||||||||

| 출처 2: 웨더베이스[125] | |||||||||||||

인구통계학

| 인구조사 | Pop. | 메모 | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1820 | 2,972 | — | |

| 1830 | 8,323 | 180.0% | |

| 1840 | 12,782 | 53.6% | |

| 1850 | 17,565 | 37.4% | |

| 1860 | 22,529 | 28.3% | |

| 1870 | 28,804 | 27.9% | |

| 1880 | 33,914 | 17.7% | |

| 1890 | 44,007 | 29.8% | |

| 1900 | 56,383 | 28.1% | |

| 1910 | 74,419 | 32.0% | |

| 1920 | 94,156 | 26.5% | |

| 1930 | 101,740 | 8.1% | |

| 1940 | 100,518 | −1.2% | |

| 1950 | 100,489 | 0.0% | |

| 1960 | 100,410 | −0.1% | |

| 1970 | 91,611 | −8.8% | |

| 1980 | 75,632 | −17.4% | |

| 1990 | 68,637 | −9.2% | |

| 2000 | 60,523 | −11.8% | |

| 2010 | 62,235 | 2.8% | |

| 2020 | 65,287 | 4.9% | |

| 2022년 (에스티) | 64,081 | −1.8% | |

| 미국 10년마다 실시되는 인구조사[126] | |||

19세기 동안 도시의 성장은 인구의 증가로 나타납니다. 1845년 미국 인구 조사에 따르면 우티카는 시카고, 디트로이트 또는 클리블랜드 인구보다 많은 20,000명의 거주자가 있는 미국에서 29번째로 큰 도시로 선정되었습니다.

2014년[update] 현재, 이 도시는 뉴욕에서 10번째로 인구가 많고 뉴욕에서 6번째로 인구가 많은 도시입니다.[127] 오네이다 군의 소재지이며, [128]모호크 계곡 지역의 중심지입니다. 미국 인구조사 추산에 따르면, Utica-Rome 메트로폴리탄 통계 지역은 2010년 299,397명에서 2014년 7월 1일 296,615명으로 인구가 감소했으며,[127] 인구 밀도는 평방 마일당 약 3,818명(1,474명/km2)이었습니다.

Utica의 인구는 인종적으로 다양하게 유지되어 왔으며 1990년대 이후 많은 새로운 이민자 유입을 받았습니다. 새로운 이민자들과 난민들은 보스니아 전쟁으로 인해 실향민이 된 보스니아인, 버마인, 카렌인, 라틴 아메리카인, 러시아인, 베트남인을 포함하고 있습니다.[129] 42개 이상의 언어가 이 도시에서 사용됩니다.[130][131] 유티카의 인구는 난민과 이민자의 유입에 영향을 받아 2010년에 40년 동안 감소를 멈췄습니다.

2020년 미국 인구 조사에 따르면, 유티카의 인구 수는 65,283명이었습니다. 2013년 미국 공동체 조사에 따르면, 이탈리아계 미국인 인구는 정점을 찍은 이후 40% 이상 감소했습니다. 그러나 이탈리아계 미국인은 도시 인구의 20%를 차지하는 가장 중요한 민족으로 남아 있습니다.[132] 유티카는 역사적으로 이탈리아에서 가장 많은 도시 중 하나입니다. 20세기 내내, 그 도시는 뉴욕, 시카고, 그리고 필라델피아와 같은 주목할 만한 수준의 이탈리아 이민자들을 가진 다른 도시들보다 이탈리아 이민자들의 집중도가 더 높았습니다.[133] 바실리카타에서 온 이탈리아 이민자들이 가장 먼저 도착했지만, 이후 대부분의 이민자들은 아풀리아, 라치오, 칼라브리아, 아브루초 지역에서 왔으며, 아풀리아의 알베로벨로 마을 출신이 유난히 많았습니다. 대부분의 이탈리아계 미국인 공동체에서 흔히 볼 수 있는 것보다 적은 숫자가 시칠리아에서 왔습니다.[134]

나머지 민족은 슬라브족(18%)이 폴란드인(8.3%), 보스니아인(7%), 동슬라브족(2.7%)으로 분류됩니다. 아일랜드계(11.3%), 아프리카계 미국인(10.5%), 독일계(10.3%), 영국계 또는 미국계(8%), 푸에르토리코계(6.8%). 버마인(3.5%), 프랑스계 및 프랑스계 캐나다인(2.7%), 아랍계 및 레바논계(2%), (비히스패닉계) 카리브해 서인도 제도(1.8%), 도미니카계(1.5%), 베트남계(1.5%), 캄보디아계(.7%). 이로쿼이족 또는 기타 (히스패닉이 아닌) 미국인(.3%).[132][135]

유티카 가구당 중위 소득은 30,818달러였습니다. 1인당 소득은 17,653달러였고, 인구의 29.6%가 빈곤 기준치를 밑돌았습니다.[91]

| 인종구성 | 2020[136] | 2010[91] | 1990[137] | 1970[137] | 1950[137] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 하얀색 | 55.3% | 69.0% | 86.7% | 94.1% | 98.4% |

| —히스패닉이 아닌 | 52.6% | 64.5% | 84.8% | 91.2% | n/a |

| 아프리카계 미국인 | 17.3% | 15.3% | 10.5% | 5.6% | 1.6% |

| 아메리칸 인디언과 알래스카 원주민 | 0.3% | 0.3% | 0.3% | 0.2% | n/a |

| 아시아의 | 12.7% | 7.2% | 1.1% | 0.1% | n/a |

| 타인종 | 6.2% | 3.9% | 1.5% | 0.1% | n/a |

| 2개 이상의 경주 | 8.1% | 4.0% | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| 히스패닉 또는 라틴계 (어떤 인종이든) | 13.8% | 10.5% | 3.4% | 0.9%[c] | n/a |

경제.

19세기 중반 동안 유티카의 운하와 철도는 가구, 기관차 헤드라이트, 증기 게이지, 화기, 직물 및 목재를 생산하는 산업을 지원했습니다.[35][100] 제1차 세계대전은 영국군을 위한 루이스 총을 생산한 새비지 암스의 성장을 촉발시켰고,[138] 그 도시는 미국에서 가장 부유한 1인당 한 곳으로 번성했습니다.[139]

20세기 초에는 지역 섬유 산업이 쇠퇴하기 시작했고, 이는 지역 경제에 큰 영향을 미쳤습니다. 이 시기에 볼 바구미는 남부 면화 작물에 악영향을 미쳤습니다. 1940년대 후반 미국 남부에 에어컨 공장이 문을 열었고, 공장들이 남쪽으로 옮겨가면서 일자리를 잃었는데, "노동할 권리" 법이 노조를 약화시켰기 때문에 인건비가 더 저렴했습니다. 다른 산업들도 오래된 산업 도시들의 일반적인 구조 조정 동안 도시 밖으로 이주했습니다.[140] 도시에서 부상할 새로운 산업은 전자 제조업(트랜지스터 라디오를 생산하는 제너럴 일렉트릭과 같은 회사 주도),[141] 기계 및 장비, 식품 가공이었습니다.[142]

그 도시는 새로운 산업으로 전환하기 위해 고군분투했습니다. 20세기 후반 동안, 그 도시의 불경기는 전국 평균보다 더 길었습니다.[143] 방위산업체들의 이탈(록히드마틴과 같이 1995년 록히드사와 마틴 마리에타의 합병으로 형성)과 전기-제조업이 최근 우티카의 경제난에 큰 역할을 했습니다.[143] 1975년부터 2001년까지 이 도시의 경제 성장률은 버팔로와 비슷한 반면, 로체스터와 빙엄턴과 같은 다른 뉴욕 북부 도시들은 두 도시 모두를 능가했습니다.[143]

21세기 초 모호크 밸리 경제는 물류, 산업 프로세스, 기계 및 산업 서비스를 기반으로 합니다.[144] 로마에서, 이전 그리피스 공군 기지는 기술 센터로서 지역 고용주로 남아있었습니다. 베로나에 있는 터닝 스톤 리조트 & 카지노는 1990년대와 2000년대 동안 많은 확장이 있는 관광지입니다.[145]

Utica의 더 큰 고용주는 CONMED Corporation(수술 장치 및 정형외과 제조업체)[146]과 도시의 주요 의료 시스템인 Mohawk Valley Health System을 포함합니다.[147]

남북 간선 도로 사업과 같은 건설은 공공 부문 고용 시장을 지원합니다.[148] 비록 19세기 이래로 이리 운하의 여객 및 상업 교통량이 크게 감소했지만, 바지선 운하는 여전히 뉴욕주 고속도로를 우회하고 철도와 함께 복합 화물 운송을 제공하면서 많은 화물을 저렴한 비용으로 유티카를 통해 이동할 수 있습니다.[149]

법, 정부, 정치

| 뉴욕주 유티카 | |

|---|---|

| 범죄율* (2014[150]) | |

| 강력범죄 | |

| 살인죄 | 6 |

| 레이프 | 22 |

| 강도 | 125 |

| 가중폭행 | 237 |

| 강력범죄합법 | 390 |

| 재산범죄 | |

| 빈집털이 | 432 |

| 절도범 | 1,845 |

| 자동차 절도 | 107 |

| 재산범죄합계 | 2,384 |

메모들 *인구 10만명당 범죄 신고건수 방화 자료 미제공, 2014년 est. 인구: 61,332명 출처: 우티카 시 경찰국 | |

2011년에 선출된 민주당의 로버트 M. 팔미에리(Robert M. Palmieri)는 유티카의 현 시장입니다.[151][152] 공동의회는 10명의 의원으로 구성되며, 그 중 6명은 단일 의원 지역에서 선출됩니다. 사장을 포함한 나머지 4명은 대규모로 선출됩니다.[153] Utica는 강력한 시장-의회 형태의 정부를 가지고 있습니다. 이 협의회에는 교통, 교육, 금융, 공공 안전 등 8개 상임 위원회가 있습니다.[154] 민주당과 공화당 사이에는 상대적으로 균형이 잡혀 있는데, 이는 20세기의 단일 정당 정치에서 변화된 것입니다.[155] 1950년대 내내 민주당은 루퍼스 엘레판테의 정치 기계의 통제 하에 시장직과 시의회의 다수를 차지했습니다.[156]

유티카는 2023년부터 공화당 브랜든 윌리엄스가 대표로 있는 뉴욕 22대 의회 선거구에 있습니다. 이 도시는 알렉산더 피니 연방 빌딩에 사무실을 두고 있는 뉴욕 북부 지방 법원에 의해 서비스되고 있습니다.[157]

컴파일러 사무소에 따르면, 2014년 Utica의 정부 비용은 총 7,930만 달러(~2022년 9,700만 달러) (전년 대비 94만 달러 순증)에 달했습니다.[158] 2015-16년 예산은 일반 기금 지출을 6,630만 달러(~2022년 8,040만 달러)로 제안하고 있습니다.[159] 2014년에 징수된 도시세는 25,972,930달러였으며, 천당 세율은 25.24달러였습니다.[159]

시 경찰국에 따르면 2014년에는 6건의 살인, 125건의 강도, 22건의 강간, 237건의 폭행이 있었습니다(전년보다 증가하여 강력 범죄율이 0.6%를 나타냄). 절도는 432건, 절도는 1,845건, 자동차 절도는 107건(2013년 대비 감소, 재산 범죄율은 3.8%)이었습니다. 뉴욕의 다른 도시들에 비해 유티카의 범죄율은 전반적으로 낮은 편입니다.[160][161] 우티카 경찰국이 도시를 순찰하고, 법 집행도 오네이다 카운티 보안관실과 뉴욕주 경찰이 관할합니다.[162] 유티카 소방서는 4개의 엔진과 2개의 트럭 회사, 구조, HAZMAT 및 의료 작업을 123명의 승무원과 조정합니다.[163]

문화

미국 북동부에 있는 유티카의 위치는 문화와 전통의 혼합을 가능하게 했습니다. 뉴욕 중부의 다른 도시들과 방언 그룹을 포함한 특징을 공유하고 있습니다. (북미 영어 내륙 지역은 펜실베니아 주의 버팔로, 엘미라, 이리와 같은 다른 러스트 벨트 도시들에도 존재합니다.)[164]

우티카는 대서양 중부 주들과 요리를 공유하며, 지역과 지역의 영향을 받습니다. 네덜란드,[72] 이탈리아, 독일, 아일랜드, 보스니아를 [165]포함한 이민자와 난민 요리의 용광로는 치체바피와 파스치치오티와[d] 같은 요리를 지역 사회에 소개했습니다.[168][169] 유티카 주식에는 닭갈비,[170] 유티카 그린,[171] 하프문,[172][173] 이탈리안 버섯 스튜,[174] 토마토 파이가 포함됩니다.[175] 다른 인기 있는 요리로는 피에로기, 펜네알라 보드카, 소시지와 고추가 있습니다.[176][177] 유티카는 양조 산업과 오랫동안 관련이 있었습니다. 가족 소유의 Matt Brewing Company(Saranac Brewery)는 소수의 국가 브랜드로 업계 통합과 함께 발생한 파산과 공장 폐쇄에 저항했습니다. 2012년 기준으로 미국에서 매출 기준으로 15번째로 큰 양조장으로 선정되었습니다.[178][179] 브루어스 협회(Brewers Association)는 2019년 이 양조장을 미국 35대 공예 양조장에 선정했습니다.[180]

시가 전국 거리 달리기 명예의 전당과 연계해 매년 개최하는 15km(9.3마일)의 보일러메이커 로드 레이스는 이 지역과 케냐, 루마니아 등 전 세계에서 러너들을 끌어들입니다.[181][182] 유니언역 옆에 있는 어린이 자연사 과학 기술 박물관은 1963년에 문을 열었습니다. 2002년, 박물관은 NASA와 협력하여 우주 관련 전시물과 행사를 선보였습니다.[183][184] 1919년에 설립된 Munson-Williams-Pector Arts Institute는 영구 소장품과 함께 회전 전시회를 개최합니다. 1999년부터 Pratt Institute와 협력하여 Pratt MWP 프로그램의 본거지이기도 합니다.[185]

유티카 정신병원은 그리스 부흥기 스타일의 과거 정신병원이 있던 곳입니다. 19세기 중반부터 1887년까지 정신병원에서 자주 사용되는 억제 장치인 유티카브가 그곳에서 발명되었습니다.[11][186][187][188] 중견 규모의 콘서트 및 공연장인 Stanley Center for the Arts는 1928년 Thomas W. Lamb에 의해 설계되었으며, 오늘날 지역 및 순회 공연 단체의 연극 및 음악 공연을 특징으로 합니다.[189] 1912년 Esenwein & Johnson에 의해 설계된 호텔 유티카는 1970년대에 간호 및 거주 관리 시설이 되었습니다.[190][191] 주목할 만한 손님에는 프랭클린 D도 포함되어 있었습니다. 루스벨트, 주디 갈랜드, 바비 다린. 2001년에 호텔로 복원되었습니다.[191][192]

공원과 레크리에이션

Utica의 공원 시스템은 677 에이커(274 ha)의 공원과 레크리에이션 센터로 구성되어 있습니다; Utica의 공원 대부분은 커뮤니티 센터와 수영장을 가지고 있습니다.[193] 뉴욕시의 센트럴 파크와 버팔로의 델라웨어 공원을 설계한 프레드릭 로 옴스테드 주니어는 유티카 공원과 파크웨이 역사 지구를 설계했습니다.[194] Olmsted는 또한 Memorial Parkway를 디자인했는데, Memorial Parkway는 지구의 공원들을 연결하고 도시의 남쪽 지역들을 둘러싸고 있는 4 mi (6.4 km)의 나무로 된 대로입니다.[195][196] 이 지역에는 로스코 콘클링 공원, 62 에이커의 F.T. 프록터 공원, 파크웨이, T.R. 프록터 공원이 있습니다.[197][198]

이 도시의 시립 골프장인 밸리 뷰(골프장 건축가 로버트 트렌트 존스가 설계)는 뉴 하트포드 마을 근처의 도시 남부에 있습니다.[193] 유티카 동물원과 스키, 스노보드, 야외 스케이팅, 튜빙을 특징으로 하는 도시 스키 슬로프인 발 비알라스 스키 샬레도 로스코 콩클링 공원의 남부 유티카에 있습니다.[199] 이 지역의 소규모 근린 공원으로는 애디슨 밀러 파크, 챈슬러 파크, 픽슬리 파크, 시모어 파크, 완켈 파크 등이 있습니다.[200]

유티카 운하 터미널 항구는 이리 운하와 모호크 강으로 연결되어 있습니다.

사회 기반 시설

교통.

로마의 그리피스 국제공항은 주로 군사 및 일반 항공을 제공하며, 시라큐스 행콕 국제공항과 알바니 국제공항은 유티카-로마 메트로폴리탄 지역의 지역, 국내 및 국제 여객 항공 여행을 제공합니다.[201] 암트랙의 엠파이어 (이름이 밝혀지지 않은 두 열차), 메이플 리프, 레이크 쇼어 리미티드 열차가 유티카의 유니언 역에 정차합니다. 버스 서비스는 유티카에 12개 노선을 운행하고 시내 중심지가 있는 시라큐스 대중 교통 운영 기관인 센트럴 뉴욕 지역 교통국(CENTRO)에서 제공합니다.[202] 시외 버스 서비스는 그레이하운드 선, 쇼트 라인, 애디론댁 트레일웨이, 버니 버스 서비스에서 제공되며, 주중 및 토요일에는 시라큐스로 운행되며,[203] 둘 다 유니언 역에서 정차합니다.[204][205]

1960년대와 1970년대에 뉴욕 주 계획자들은 빙엄턴과 81번 고속도로 연결을 포함하는 유티카의 간선 도로 시스템을 구상했습니다.[206] 지역 사회의 반대로 인해 도시를 관통하는 남북 간선 도로를 포함하여 고속도로 프로젝트의 일부만 완료되었습니다.[207][206][208] 6개의 뉴욕주 고속도로, 1개의 3자리 주간 고속도로, 1개의 2자리 주간 고속도로가 Utica를 통과합니다. 뉴욕 주 49번 국도와 840번 국도는 각각 유티카의 북쪽과 남쪽 경계를 따라 운행되는 동서 고속도로이며, 각각의 동쪽 종점은 도시에 있습니다. 뉴욕 주 5번 국도와 그 대체 경로인 5S번 국도와 5A번 국도는 유티카를 통과하는 동서 도로 및 고속도로입니다. 5S번 국도의 서쪽 종착역과 5A번 국도의 동쪽 종착역은 모두 시내에 있습니다. 5번 국도와 790번 고속도로(90번 고속도로의 보조 고속도로)를 통해 뉴욕 주 12번 국도와 8번 국도가 남북 간선 고속도로를 형성합니다.[209]

유틸리티

유티카의 전기는 2002년에 도시의 전 전기 공급업체인 나이아가라 모호크를 인수한 영국의 에너지 회사인 내셔널 그리드(National Grid plc)에 의해 공급됩니다.[210] Utica는 마르시 마을에 변전소가 [211]있는 주요 전기 송전선의 교차로 근처에 있습니다. 뉴욕 전력청, 내셔널 그리드, 통합 에디슨, 뉴욕주 전기가스공사(NYSEG)의 확장 프로젝트가 계획되어 있습니다.[212][213] 2009년에는 도시 기업(Utica College, St. 포함). Luke's Medical Center)는 마이크로그리드를 개발했고, 2012년 Utica City Council은 공공의 도시 소유 전력 회사의 가능성을 타진했습니다.[214][215][216] 유티카의 천연가스는 내셔널 그리드와[217] NYSEG에서 제공합니다.[218][219]

도시 고형 폐기물은 단일 스트림 재활용, 폐기물 감소, 퇴비화, 유해 물질 및 철거 잔해물 처리를 조정하는 공익 법인인 [220]Oneida-Herkimer 고체 폐기물 관리 기관에서 매주 수집 및 처리합니다.[221] Utica의 폐수는 Mohawk Valley Water Authority에 의해 처리되며, 하루에 3,200만 갤런의 용량을 가질 수 있습니다.[222][223] 처리된 물은 병원균, 질산염, 아질산염을 포함한 불순물에 대해 테스트됩니다.[222] Utica의 식수는 Adirondack 산맥의 기슭에 있는 하천을 공급하는 Hinckley 저수지에서 [223]생산되며 도시 전체에 700마일(1,100km)의 배관이 있습니다.[224]

건강관리

Utica의 주요 의료 서비스는 Mohawk Valley Health System에 의해 제공됩니다.[225]

윈 병원

윈 병원은 2023년 10월 우티카 시내에 문을 열었습니다. 이 6억 5천만 달러의 시설은 66년 된 Facston St.를 대체했습니다. 뉴하트포드에 있는 루크 헬스케어 병원과 106세의 세인트루이스입니다. 지금은 문을 닫은 유티카의 엘리자베스 메디컬 센터.[226][227] Wynn은 다른 시설들 중에서도 1층 외상실 2개와 4층 단면실 2개를 포함하고 있습니다.[227]

팩스턴 가 루크 앤 세인트 엘리자베스.

팩스턴 앤 세인트 루크는 외과 센터였고 세인트루이스는 엘리자베스는 트라우마와 수술의 중심이었습니다.[225] 팩스턴 앤 세인트 루크의 병원에는 총 370개의 급성 병상과 202개의 장기 병상이 있었고, 세인트루이스도 있었습니다. 엘리자베스 메디컬 센터에는 201개의 급성기 치료 병상이 있었습니다.[228] 2023년 윈 병원으로 보건 시설이 옮겨진 후, 현재 문을 닫은 병원들의 운명은 불분명했습니다.[227]

교육

이타카와 시라큐스처럼 유티카에는 공립 및 사립 대학이 혼재되어 있으며, 3개의 주립 대학과 4개의 사립 대학이 유티카-로마 대도시 지역에 있습니다. North Utica and Marcy에 있는 850 에이커의 캠퍼스에 있는 SUNY Polytechnic Institute는 2,000명이[229] 넘는 학생들을 보유하고 있으며, 뉴욕 주립 대학(SUNY)의 14개 박사 학위 대학 중 하나입니다.[230] Mohawk Valley Community College는 시라큐스와 알바니 사이에 있는 가장 큰 대학으로,[231] 엠파이어 스테이트 칼리지는 유티카와 로마에 서비스를 제공합니다.[232]

이전에는 시라큐스 대학교의 위성 캠퍼스였던 유티카 대학교(Utica College, 2022년 이전의 유티카 칼리지)는 3,000명 이상의 학생이 재학 중인 4년제 사립 교양 대학입니다.[233] 1904년에 설립된 세인트 엘리자베스 간호 대학은 간호 학위를 수여하기 위해 지역 기관과 협력합니다.[234] 프랫 인스티튜트는 먼슨에 있는 위성 캠퍼스를 통해 현지 2년의 미술 과정을 제공합니다.[235] 영리 경영대학인 유티카 상업대학은 2016년 말에 문을 닫았습니다.[236]

Utica City 학군은 2012년에[237] 거의 10,000명의 학생이 등록했으며, 뉴욕주 북부에서 가장 인종적으로 다양한 학군입니다.[238] 지역 학교로는 토마스 R이 있습니다. 프록터 고등학교, 제임스 H. 도노반 중학교, 존 F 케네디 중학교 그리고 10개의 초등학교. 우티카의 원래 공립 고등학교인 우티카 프리 아카데미는 1987년에 문을 닫았습니다.[239] 이 도시는 1959년에 Xaverian Brothers에 의해 설립된 작은 카톨릭 고등학교인 노트르담 중학교의 본거지이기도 합니다.[240]

유티카의 첫 번째 공공 도서관은 1838년에 설립되었습니다. 1904년 유티카 공립도서관이 완공되기 전까지 도서관의 위치는 여러 차례 옮겨졌습니다.[241] Utica Public Library(유티카 공립 도서관)은 Utica(유티카)에 기반을 둔 3개 카운티 미드 요크 도서관 시스템의 일부입니다. 두 기관 모두 뉴욕주립대학의 등록위원회에 의해 전세를 받습니다.[242]

스포츠

유티카는 내셔널 하키 리그의 뉴저지 데블스에 소속된 팀인 아메리칸 하키 리그 (AHL)의 유티카 코메츠의 본거지입니다. 밴쿠버 캐넉스가 AHL 프랜차이즈를 이전한 2013-14 시즌을 위해 유티카에 창단되었습니다.[243][244] 1960년 유티카 기념 강당으로 문을 연 3,815석 규모의 아디론댁 은행 센터는 코메츠와 유티카 대학 개척자들의 본거지입니다. 유티카 데블스는 1987년부터 1993년까지 AHL에서 뛰었고, 유티카 불독스(1993-94), 유티카 블리자드(1994-1997), 모호크 밸리 프롤러스(1998-2001)는 유나이티드 하키 리그(UHL) 소속이었습니다.[245]

2018년부터 이 도시는 또한 메이저 아레나 사커 리그에서 뛰고 있는 프로 실내 축구팀인 유티카 시티 FC의 본거지이기도 합니다.[246]

이 도시는 토론토 블루제이스, 그리고 후에 마이애미 말린스에 소속된 뉴욕-펜 리그 야구팀인 유티카 블루삭스(1939-2001)의 홈구장이었습니다. 그 외에 우티카 어사일럼스(1900년), 보스턴 브레이브스 소속 우티카 브레이브스(1939년 ~ 1942년) 등이 있습니다.[247] 2008년 이래로, 이 도시는 블루삭스라고 불리는 대학의 여름 야구팀의 본거지였습니다.

Area College teams

| 학교 | 위치 | 애칭 | 색 | 협회. | 회의. | 참고문헌 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 선와이 폴리테크닉 인스티튜트 | 마시 | 삵 | 청금 | NCAA 디비전 III | NEAC | [248] |

| 해밀턴 칼리지 | 클린턴 | 대륙 | 버프 앤 블루 | NCAA 디비전 III | NESCAC | [249] |

| 우티카 대학 | 우티카 | 파이오니어스 | 네이비와 오렌지 | NCAA 디비전 III | 엠파이어 8 | [250] |

| 모호크 밸리 커뮤니티 칼리지 | 우티카 | 호크스 | 숲의 녹색과 흰색 | NJCAA | 레지옹 III | [251] |

| 허키머 카운티 커뮤니티 칼리지 | 허키머 | 장군들 | 헌터 그린 앤 골드 | NJCAA | 레지옹 III | [252] |

미디어

Utica는 주요 텔레비전 방송국인 WKTV 2(NBC; DT2의 CBS; DT3의 CW),[253] WUTR 20(ABC), WFXV 33(폭스)의 3개 방송국에서 제공됩니다. 시라큐스의 PBS 회원국 WCNY-TV는 채널 24에서 번역기 W22DO-D를 운영하고 있습니다. WPNY-LD 11(My Network)과 같은 여러 저전력 텔레비전 방송국TV), 해당 지역에서도 방송됩니다. 케이블 텔레비전 시청자들은 지역 뉴스 서비스와 대중 접근 채널을 제공하는 시라큐스 통신국(Charter Spectrum)에서 제공합니다.[254] 디시 네트워크와 디렉TV는 위성 텔레비전 고객에게 지역 방송 채널을 제공합니다.[255][256]

유티카의 주요 일간지는 옵저버 디스패치이고 로마 센티넬과 시라큐스 포스트 스탠다드도 유티카 뉴스를 다루고 있습니다. 이 도시에는 26개의 FM 라디오 방송국과 9개의 AM 방송국이 있습니다. 이 지역의 주요 역 소유주로는 타운스퀘어 미디어와 갤럭시 커뮤니케이션이 있습니다. 사소한 대중문화적 언급 외에도 [257][258][259][260]슬랩샷(Slap Shot, 1977)은 부분적으로 유티카에서 촬영되었으며, 이 도시는 TV 시리즈 The Office에 등장했습니다.[259][261][262]

주목할 만한 사람들

참고 항목

- 로어제네시 스트리트 역사지구

- 유티카 셰일 - 유티카의 이름을 딴 지질층

- 뉴욕 중심부의 도시 조성 연대표

- 동우티카

참고사항 및 참고사항

메모들

참고문헌

- ^ 보티니 & 데이비스 2007, 90쪽.

- ^ Bagg 1892, 20쪽.

- ^ a b c d e Ripley, George; Dana, Charles A., eds. (1879). . The American Cyclopædia. Vol. 16 (1879 ed.). D. Appleton & Company – via Wikisource.

- ^ a b Bagg 1892, 페이지 199.

- ^ "ArcGIS REST Services Directory". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on January 19, 2022. Retrieved September 20, 2022.

- ^ "U.S. Census Bureau, 2011-2015 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates". 2015 Population Estimates. United States Census Bureau, Population Division. Archived from the original on February 14, 2020. Retrieved April 20, 2017.

- ^ "Census Urban Area List". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on March 28, 2012. Retrieved May 7, 2015.

- ^ "Feature Detail Report for: Utica". United States Geological Survey. January 23, 1980. Archived from the original on May 30, 2022. Retrieved April 15, 2015.

- ^ "U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Utica city, New York". Census.gov. Archived from the original on May 30, 2022. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ Hartman, Susan (June 3, 2022). "How Refugees Transformed a Dying Rust Belt Town". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on June 5, 2022. Retrieved June 5, 2022.

- ^ a b c Czarnota, Lorna (2014). "Utica: Beer and Insanity". Native American & Pioneer Sites of Upstate New York: Westward Trails from Albany to Buffalo. The History Press. pp. 77–81. ISBN 978-1-6258-4776-8.

- ^ a b c d Thomas 2003, 17페이지

- ^ Eisenstadt, Peter R. (2005). "Place names". The Encyclopedia of New York State. Syracuse University Press. p. 1208. ISBN 9780815608080.

- ^ Farrell, William R. (2002). Classical Place Names in New York State. Pine Grove Press. ISBN 9781890691080.

- ^ Bagg 1892, 페이지 3.

- ^ 아동 1900, 페이지 2.

- ^ Bagg 1892, 21쪽.

- ^ a b Thomas 2003, p. 15.

- ^ Bagg 1892, pp. 19–20.

- ^ a b c 어린이 1900, 페이지 134.

- ^ Czarnota, Lorna (April 8, 2014). "Utica: Beer and Insanity". Native American & Pioneer Sites of Upstate New York: Westward Trails from Albany to Buffalo. The History Press. p. 77. ISBN 978-1-6258-4776-8.

- ^ Hauptman, Laurence M. (2001). Conspiracy of interests : Iroquois dispossession and the rise of New York State (1st pbk ed.). Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-8156-0712-0. OCLC 47017112. Archived from the original on May 30, 2022. Retrieved January 17, 2022.

- ^ 어린이 1900, 페이지 1.

- ^ 어린이 1900, 52쪽.

- ^ Hulbert, Archer Butler; Hall, James; Wallcut, Thomas; Bigelow, Timothy; Halsey, Francis Whiting; Dickens, Charles; Murray, Sir Charles Augustus (1904). Pioneer Roads and Experiences of Travelers. A. H. Clark Company. pp. 99–108. Retrieved April 29, 2015.

- ^ 어린이 1900, 7쪽.

- ^ Przybycien, F. E. (1976). Utica: A City Worth Saving. Dodge-Graphic Press, Inc.

- ^ Bagg 1892, pp. 48–49.

- ^ Bagg 1892, 89쪽.

- ^ Bagg 1892, 페이지 131.

- ^ Dann, Norman Kingsford (2021). Passionage Energies. The Gerrit and Ann Smith Family of Petersboro, New York[,] Through a Century of Reform. Hamilton, New York: Log Cabin Books. p. 18. ISBN 9781733089111.

- ^ 토마스 2003, 22쪽

- ^ a b c d 토마스 2003, 25쪽

- ^ Interstate Commerce Commission Reports: Reports and Decisions of the Interstate Commerce Commission of the United States, Volume 59. Harvard University: L.K. Strouse, United States Interstate Commerce Commission. 1921. p. 142. Archived from the original on November 4, 2015. Retrieved April 19, 2015.

- ^ a b 어린이 1900, 25쪽.

- ^ Cookinham, H. J. (1912). History of Oneida County, New York: from 1700 to the present time. New York Public Library: Chicago: S.J. Clarke Publishing Company.

- ^ 아동 1900, 56-57쪽.

- ^ Starr, Timothy (2012). Railroad Wars of New York State. The History Press. p. 80. ISBN 978-1-6094-9727-9.

- ^ Gove, Bill (2006). Logging Railroads of the Adirondacks. Syracuse University Press. pp. 71–75. ISBN 978-0-8156-0794-6.

- ^ Bagg, 1877, 164쪽

- ^ Malone, Vol. X, 1931, 페이지 294

- ^ Dann, Norman Kingsford (2021). Passionate Energies. The Gerrit and Ann Smith Family of Peterboro, New York Through a Century of Reform. Hamilton, New York: Log Cabin Books. ISBN 9781733089111.

- ^ Calarco, Tom (February 23, 2011). The Underground Railroad in the Adirondack Region. McFarland. p. 132. ISBN 978-0-7864-8740-0.

- ^ a b Switala 2006, 80쪽.

- ^ a b Switala 2006, 페이지 111.

- ^ The enemies of the Constitution discovered; or, An inquiry into the origin and tendency of popular violence. Containing a complete and circumstantial account of the unlawful proceedings at the City of Utica, October 21st, 1835; the dispersion of the State Anti-Slavery Convention by the agitators, the destruction of a democratic press, and of the causes which led thereto; together with a concise treatise on the practice of the court of His Honor Judge Lynch. Accompanied with numerous highly interesting and important documents. New York: Leavitt, Lord & Co. 1835.

- ^ Switala 2006, 80쪽, 83쪽, 112쪽.

- ^ Sorin, Gerald (1970). The New York Abolitionists. A Case Study of Political Radicalism. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing. p. 32. ISBN 0837133084.

- ^ "The Dispersed Agitators". Richmond Enquirer. "From the Utica Observer". November 20, 1835. p. 4. Archived from the original on January 13, 2022. Retrieved January 13, 2022 – via Virginia Chronicle, Library of Virginia.

- ^ Edwards, Evelyn R. (January 24, 2007). Around Utica. Arcadia Publishing. p. 65. ISBN 978-1-4396-1852-3.

- ^ Hilton, George W.; Due, John Fitzgerald (January 1, 2000). The Electric Interurban Railways in America. Stanford University Press. p. 121. ISBN 9780804740142.

- ^ 토마스 2003, 33–44, 74–76, "Loom to Boom".

- ^ Tomaino, Frank. "Golder leads Utica's 'loom to boom' era". Utica Observer Dispatch. Archived from the original on February 11, 2023. Retrieved August 11, 2022.

- ^ Thomas 2003, p. 4, 61.

- ^ Benedetto, Richard (2006). Politicians are People, Too. University Press of America. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-7618-3422-9.

- ^ a b Webster, Dennis (2012). Wicked Mohawk Valley. The History Press. p. 102. ISBN 978-1-6094-9390-5.[unre신뢰할 수 있는 출처?]

- ^ LaDuca, Rocco (May 6, 2009). "Day 4: The Mob Files". Utica Observer Dispatch. Retrieved December 5, 2022.

- ^ DeLuca, Rocco (May 6, 2009). "Day 5: Mr. Fischer takes on Sin City". Utica Observer Dispatch. Retrieved July 15, 2023.

- ^ 토마스 2003, 66-70쪽.

- ^ 토마스 2003, 58쪽

- ^ Croniser, Rebecca (September 14, 2008). "Utica's organized crime revisited". Observer-Dispatch. GateHouse Media. Archived from the original on April 19, 2015. Retrieved April 19, 2015.

- ^ 토마스 2003, 페이지 57, 70.

- ^ Ellis, David Maldwyn (1979). "The New York Character". New York: State and City. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press. p. 22. ISBN 9780801411809.

- ^ 토마스 2003, 49-50쪽.

- ^ Thomas & Smith 2009, 24페이지

- ^ Thomas & Smith 2009, 66쪽.

- ^ Thomas 2003, 페이지 113.

- ^ Hevesi, Alan G. "Population Trends in New York State's Cities" (PDF). Division of Local Government Services & Economic Development. Office of the New York State Comptroller. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 16, 2015. Retrieved April 18, 2015.

- ^ "Former Utica mayor Edward Hanna dies in Fayetteville". syracuse. Associated Press. March 13, 2009. Retrieved August 27, 2023.

- ^ Ledbetter, Carly (November 15, 2014). "10 Most Affordable Housing Markets In America". Huffington Post. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved August 24, 2015.

- ^ Weir, Robert E. (2013). Workers in America: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 425. ISBN 978-1-5988-4719-2.

- ^ a b Hartman, Susan (August 10, 2014). "A New Life for Refugees, and the City They Adopted". New York Times. Archived from the original on May 29, 2015. Retrieved April 9, 2015.

- ^ Brody, Leslie (January 21, 2015). "Small Cities Fight for More School Aid From New York State". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on April 19, 2015. Retrieved April 19, 2015.

- ^ Struck, Jules (May 26, 2022). "'They saved this town': Refugees poured into Utica and cleared the rust from a dying industrial city". syracuse.com. Archived from the original on June 7, 2022. Retrieved June 7, 2022.

- ^ Coughlin, Reed; Owens-Manley, Judith (2006). Bosnian Refugees in America: New Communities, New Cultures. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-3872-5154-7.

- ^ Hartman, Susan (June 9, 2022). "How Utica Became a City Where Refugees Came to Rebuild". Literary Hub. Retrieved August 30, 2023.

- ^ Bansak, Cynthia; Simpson, Nicole; Zavodny, Madeline (2015). The Economics of Immigration. Routledge. p. 322. ISBN 978-1317752998.

- ^ Rajagopalan, Kavitha (May 16, 2016). "Progressive City Welcomes One and All? Not So Fast". nextcity.org. Retrieved August 30, 2023.

- ^ Harris, Elizabeth A. (May 19, 2016). "Utica Settles Lawsuit Over Refugees' Access to High School". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 21, 2022. Retrieved January 21, 2022.

- ^ Chen, David W. (July 21, 2016). "Utica Settles State Claim Alleging Biased Enrollment for Refugee Students". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 21, 2022. Retrieved January 21, 2022.

- ^ Dooling, Sarah; Simon, Gregory (2012). Cities, Nature and Development: The Politics and Production of Urban Vulnerabilities. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. pp. 165–181. ISBN 978-1-4094-0831-4.

- ^ Clukey, Keshia (December 28, 2013). "Utica schools have highest poverty rate in Upstate NY". Observer-Dispatch. Archived from the original on May 30, 2022. Retrieved August 24, 2015.[데드링크]

- ^ "Cuomo visits Lake Placid, Utica to talk upstate development". WIVB.com. Associated Press. February 12, 2015. Archived from the original on April 27, 2015. Retrieved April 20, 2015.

- ^ Cooper, Elizabeth (February 17, 2015). "Cuomo won't budge on $1.5 billion economic development competition". Observer-Dispatch. GateHouse Media. Archived from the original on May 30, 2022. Retrieved April 20, 2015.

- ^ Thomas, Brian (February 8, 2010). "City of Utica Master Plan Accomplishments / 2.8.10". City of Utica Master Plan. Archived from the original on January 20, 2015. Retrieved April 15, 2015.

- ^ Miner, Dan (July 12, 2010). "Utica master plan: 'Play ball!' at Harbor Point?". Observer-Dispatch. GateHouse Media. Archived from the original on April 19, 2015. Retrieved April 19, 2015.

- ^ "Governor Cuomo Announces 'Nano Utica' $1.5 Billion Public-Private Investment That Will Make the Mohawk Valley New York's Next Major Hub of Nanotech Research". Governor Andrew M. Cuomo. New York State. October 10, 2013. Archived from the original on April 27, 2015. Retrieved April 20, 2015.

- ^ Howe, Steve. "What to know about Wolfspeed and its $1B facility in Upstate New York". Utica Observer Dispatch. Retrieved August 30, 2023.

- ^ Horning, Payne (December 9, 2019). "Groundbreaking planned for new Utica hospital". WRVO Public Media. Retrieved August 30, 2023.

- ^ Caputo, Thomas (October 29, 2023). "HAPPENING TODAY: Wynn Hospital officially opens". Rome Sentinel. Retrieved October 29, 2023.

- ^ a b c "Utica (city) QuickFacts from the US Census Bureau". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on March 23, 2015. Retrieved April 7, 2015.

- ^ a b Hislop, Codman (1948). The Mohawk. Syracuse University Press. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-8156-2472-1.

- ^ Hudson, John C. (2002). Across This Land: A Regional Geography of the United States and Canada. JHU Press. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-8018-6567-1.

- ^ "Utica, NY to Albany, NY". Google Maps. Archived from the original on May 18, 2015. Retrieved May 3, 2015.

- ^ Thomas 2003, p. 5.

- ^ "Utica Marsh Wildlife Management Area Overview". New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Archived from the original on May 14, 2015. Retrieved April 19, 2015.

- ^ "Utica Marsh" (PDF). New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 15, 2015. Retrieved April 19, 2015.

- ^ 아동 1900, 페이지 55.

- ^ Bottini & Davis 2007, Pix.

- ^ a b c Writers' Program. New York (1974). New York: A Guide to the Empire State. North American Book Dist LLC. pp. 353–355. ISBN 978-0-4030-2151-2.

- ^ "New York State Office Building, Utica". SkyscraperPage.com. Skyscraper Source Media. Archived from the original on September 14, 2015. Retrieved April 18, 2015.

- ^ 아동 1900, 페이지 57–58.

- ^ 어린이 1900, 130쪽.

- ^ Kohn, Solomon Joshua (1959). The Jewish community of Utica, New York, 1847-1948. American Jewish Historical Society. p. 130. OCLC 304259.

- ^ Bean, Philip A. (2004). La Colonia: Italian Life and Politics in Utica, New York, 1860-1960. Utica College, Ethnic Heritage Studies Center. p. 111. ISBN 978-0-9660-3630-5.

- ^ Tamburri, Anthony Julian; Giordano, Paolo; Gardaphe, Fred L. (2000). From the Margin: Writings in Italian Americana. Purdue University Press. pp. 386–390. ISBN 978-1-5575-3152-0.

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- ^ "National Register of Historic Places Listings". WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 9/07/10 THROUGH 9/10/10. National Park Service. September 17, 2010. Archived from the original on February 1, 2014. Retrieved February 14, 2016.

- ^ "National Register of Historic Places Listings". Weekly List of Actions Taken on Properties: 1/03/12 through 1/06/12. National Park Service. January 13, 2012. Archived from the original on August 28, 2013. Retrieved February 14, 2016.

- ^ "National Register of Historic Places Listings". Weekly List of Actions Taken on Properties: 9/14/15 through 9/18/15. National Park Service. September 25, 2015. Archived from the original on May 30, 2022. Retrieved February 14, 2016.

- ^ "National Register of Historic Places". Weekly List of Actions Taken on Properties: 1/04/16 through 1/08/16. National Park Service. January 15, 2016. Archived from the original on May 30, 2022. Retrieved February 14, 2016.

- ^ Observer-Dispatch. "Uptown Theatre named in Register of Historic Places". Utica Observer Dispatch. Archived from the original on February 11, 2023. Retrieved January 17, 2023.

- ^ Kottek, Marcus; Greiser, Jürgen; et al. (June 2006). "World Map of Köppen–Geiger Climate Classification" (PDF). Meteorologische Zeitschrift. E. Schweizerbart'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung. 15 (3): 261. Bibcode:2006MetZe..15..259K. doi:10.1127/0941-2948/2006/0130. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 24, 2021. Retrieved June 3, 2020.

- ^ a b "Utica, New York Köppen Climate Classification (Weatherbase)". Weatherbase. Archived from the original on January 14, 2016. Retrieved April 23, 2015.

- ^ "USDA Plant Hardiness Zone Map". United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. 2012. Archived from the original on February 27, 2014. Retrieved April 23, 2015.

- ^ Catie, O'Toole (January 5, 2015). "Weather: 6 inches to nearly 2 feet of lake-effect snow possible in parts of CNY". Syracuse.com. Archived from the original on April 6, 2015. Retrieved April 19, 2015.

- ^ Monmonier, Mark (2000). Air Apparent: How Meteorologists Learned to Map, Predict, and Dramatize Weather. University of Chicago Press. p. 151. ISBN 978-0-2265-3423-7.

- ^ Karmosky, Christopher (2007). Synoptic Climatology of Snowfall in the Northeastern United States: an Analysis of Snowfall Amounts from Diverse Synoptic Weather Types. University of Delaware. Department of Geography. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-5493-8718-3.

- ^ 어린이 1900, 페이지 136.

- ^ "Utica, New York Travel Weather Averages (Weatherbase)". Weatherbase. Archived from the original on January 13, 2016. Retrieved April 24, 2015.

- ^ "NOWData - NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on January 11, 2019. Retrieved May 8, 2021.

- ^ "Station: Rome Griffiss Airfield, NY". U.S. Climate Normals 2020: U.S. Monthly Climate Normals (1991-2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on May 8, 2021. Retrieved May 8, 2021.

- ^ "Station: Griffiss AFB, NY". U.S. Monthly Climate Normals (1991-2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on May 8, 2021. Retrieved May 8, 2021.

- ^ "GRIFFISS AFB, NEW YORK". Western Regional Center. Archived from the original on May 10, 2021. Retrieved May 8, 2021.

- ^ "Rome, New York". Weatherbase.com. Archived from the original on January 13, 2016. Retrieved April 20, 2015.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Archived from the original on March 11, 2014. Retrieved June 4, 2016.

- ^ a b "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2014 - 2014 Population Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on April 4, 2015. Retrieved April 24, 2015.

- ^ "Residents". Oneida County, NY. Archived from the original on September 12, 2015. Retrieved August 22, 2015.

- ^ Clarridge, Emerson (July 11, 2010). "Mayor Roefaro to speak at Bosnian commemoration event in Syracuse". Utica Observer-Dispatch. Retrieved April 6, 2015.

- ^ "Six Continents, One Hometown: Public Opinion On Refugee Resettlement In Utica". 2013. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved January 1, 2021.[검증 필요]

- ^ "Utica, New York". Modern Language Association. 2000. Archived from the original on May 30, 2022. Retrieved May 8, 2015.

- ^ a b "Census.org". Archived from the original on December 5, 2021. Retrieved December 13, 2020.

- ^ "Exploring the "Urban Colonies" of Utica". Haverford College. September 16, 2010. Archived from the original on August 20, 2022. Retrieved August 20, 2022.

- ^ Bean, Philip A. (2006). "Leftists, Ethnic Nationalism, and the Evolution of Italian-American Identity and Politics in Utica's "Colonia"". New York History. 87 (4): 423–474. ISSN 0146-437X. JSTOR 23183387. Archived from the original on January 16, 2023. Retrieved January 16, 2023.

- ^ "American FactFinder". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved May 7, 2015.

- ^ "HISPANIC OR LATINO, AND NOT HISPANIC OR LATINO BY RACE, UTICA, NEW YORK". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on January 31, 2022. Retrieved January 31, 2022.

- ^ a b c "New York - Race and Hispanic Origin for Selected Cities and Other Places: Earliest Census to 1990" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved May 7, 2015.

- ^ "Savage Arms History". Savage Arms. Archived from the original on May 18, 2015.

- ^ Thomas & Smith 2009, 64쪽.

- ^ Thomas 2003, 38쪽

- ^ 토마스 2003, 페이지 117.

- ^ "Utica Buildings Emporis". Emporis. Archived from the original on May 11, 2015. Retrieved May 8, 2015.

- ^ a b c "The Regional Economy of Upstate New York" (PDF). New York Fed. Federal Reserve Bank of New York. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 19, 2015. Retrieved April 15, 2015.

- ^ "Mohawk Valley START-UP NY". Archived from the original on July 14, 2015. Retrieved December 13, 2015.

- ^ 보티니 & 데이비스 2007, 페이지 x.

- ^ Gerould, S. Alexander (January 4, 2015). "DEC has eye on contamination at ConMed site". Observer-Dispatch. GateHouse Media. Archived from the original on April 23, 2015. Retrieved April 23, 2015.

- ^ "CONMED Corporation News". The New York Times. 2008. Archived from the original on April 17, 2015. Retrieved April 15, 2015.

- ^ Miner, Dan (May 3, 2012). "DOT unveils accelerated time frame for Arterial project". Observer-Dispatch. Retrieved April 18, 2015.

- ^ Goodban Belt, LLC (May 2010). "New York State Canal System, Modern Freight-Way" (PDF). New York State Canal Corporation. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 12, 2015. Retrieved April 24, 2015.

- ^ "Crime, Arrest and Firearm Activity Report: Utica Index Crimes" (PDF). Division of Criminal Justice Services. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 3, 2021. Retrieved August 23, 2015.

- ^ "Mayor's Office". City of Utica. Archived from the original on April 24, 2015. Retrieved May 4, 2015.

- ^ Miner, Dan (November 17, 2011). "Palmieri wins Utica mayoral election". Utica Observer-Dispatch. Archived from the original on May 30, 2022. Retrieved June 26, 2015.

- ^ "Common Council". City of Utica. Archived from the original on April 11, 2015. Retrieved April 16, 2015.

- ^ "Standing Committees". City of Utica. Archived from the original on May 10, 2015. Retrieved April 16, 2015.

- ^ 토마스 2003, 145-149쪽.

- ^ Thomas 2003, p. 37.

- ^ "Utica Northern District of New York United States District Court". United States Court, Northern District of New York. Archived from the original on April 8, 2015. Retrieved April 21, 2015.

- ^ Bonadio & Co., LLP. "Financial Statements and Required Reports Under OMB Circular A-133 as of March 31, 2014" (PDF). City of Utica. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 23, 2015. Retrieved April 16, 2015.

- ^ a b "2015-2016 Board of E & A Approved Budget" (PDF). City of Utica. February 13, 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 23, 2015. Retrieved April 15, 2015.

- ^ Sperling, Bert; Sander, Peter J. (May 7, 2007). Cities Ranked & Rated: More Than 400 Metropolitan Areas Evaluated in the U.S. and Canada. John Wiley & Sons. p. 762. ISBN 978-0-4700-6864-9.

- ^ "Crime, Arrest and Firearm Activity Report" (PDF). Division of Criminal Justice Services. New York State Division of Criminal Justice Services (published March 6, 2015). January 31, 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 3, 2021. Retrieved April 23, 2015.

- ^ "Law Enforcement Division - Oneida County Sheriff". Oneida County Sheriff's Office. Archived from the original on May 18, 2015. Retrieved May 8, 2015.

- ^ "Fire Department". City of Utica. Archived from the original on April 30, 2015. Retrieved May 8, 2015.

- ^ Bartelma, Katy (December 13, 2004). Let's Go 2005 USA: With Coverage of Canada. St. Martin's Press. p. 642. ISBN 978-0-3123-3557-1.

- ^ Santos, Fernanda (October 21, 2006). "Where Young Refugees Find a Place to Fit In". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 6, 2017. Retrieved April 9, 2015.

- ^ "Quality of Life". City of Utica. Archived from the original on April 17, 2015. Retrieved April 17, 2015.

- ^ Nadeau, Mary (September 11, 2008). "A bright outlook on life". Observer-Dispatch. GateHouse Media. Archived from the original on May 30, 2022. Retrieved April 22, 2015.

- ^ Miltner, Karen (June 20, 2010). "From riggies to cevapi, immigrants have shaped Utica's food scene". Democrat and Chronicle. Gannett. Archived from the original on April 20, 2015. Retrieved April 20, 2015.

- ^ "New York State". Insight Guides: USA on the Road. Apa Publications (UK) Limited. February 25, 2013. ISBN 978-1-7800-5632-6.

- ^ Monaski, Jeff (June 6, 2013). "Utica Native Shares Chicken Riggies Recipe With Taste Of Home Magazine". WIBX 950AM. Townsquare Media. Archived from the original on April 13, 2015. Retrieved April 20, 2015.

- ^ Baber, Cassaundra (January 11, 2010). "Next Food Network star: Utica greens". Utica Observer-Dispatch. GateHouse Media. Retrieved April 15, 2015.

- ^ Levine, Ed (January 15, 2008). "The Best Black and White Cookies? Half-Moons? Amerikaners?". New York Serious Eats. Serious Eats. Archived from the original on April 16, 2015. Retrieved April 15, 2015.

- ^ Hubbell, Matt (April 16, 2015). "Are Utica's Halfmoon Cookies 'Today Show' Bound?!". lite98.7. Townsquare Media. Archived from the original on April 27, 2015. Retrieved April 20, 2015.

- ^ "CNYEats A Taste of Utica Mushroom Stews". Apple Crumbles. November 22, 2009. Archived from the original on January 6, 2018. Retrieved January 5, 2018.

- ^ Russell, Tina (August 6, 2014). "O'Scugnizzo Pizzeria: A slice of Utica's history turns 100". Utica Observer-Dispatch. GateHouse Media. Archived from the original on February 11, 2023. Retrieved April 15, 2015.

- ^ "Visitors". City of Utica. Food. Archived from the original on April 10, 2015. Retrieved April 16, 2015.

- ^ "Quality of Life". www.cityofutica.com. Archived from the original on April 17, 2015. Retrieved April 25, 2015.

- ^ "F.X. Matt Brewing Co. / Saranac - Brew Central". BrewCentralNY.com. Archived from the original on April 27, 2015. Retrieved April 20, 2015.

- ^ "Brewers Association Releases Top 50 Breweries of 2012; Top 50 Overall U.S. Brewing Companies (Based on 2012 beer sales volume)". Boulder, CO: Brewers Association. April 10, 2013. Archived from the original on September 21, 2015. Retrieved April 20, 2015.

- ^ Andrews, Colman. "Brewing across America: These are the 35 most successful US craft breweries". USA TODAY. Archived from the original on November 5, 2021. Retrieved November 5, 2021.

- ^ Moses, Sarah (December 3, 2014). "Boilermaker Road Race makes changes to registration process for 2015". Syracuse.com. Syracuse Media Group. Archived from the original on April 19, 2015. Retrieved April 18, 2015.

- ^ Braine, Bill (November 2007). Runner's World. 11. Vol. 42. Rodale, Inc. pp. 119–120. ISSN 0897-1706.

- ^ Sharp, Debbie (July 6, 2005). "Opening Set for NASA Exhibits at Utica Children's Museum". NASA. Archived from the original on January 13, 2016. Retrieved April 18, 2015.

- ^ "The Children's Museum of History, Natural History, Science & Technology". City of Utica. Archived from the original on April 19, 2015. Retrieved April 18, 2015.

- ^ "PrattMWP, Pratt Institute's Utica, NY campus: A Great Choice for Many Art Students". PrattMWP College of Art and Design. Munson Williams Proctor Art Institute. Archived from the original on April 19, 2015. Retrieved April 18, 2015.

- ^ Burns, Stanley B. (September 28, 2011). "19th and 20th century psychiatry: 22 rare photos". CBS News. CBS. Archived from the original on April 19, 2015. Retrieved April 18, 2015.

- ^ Roth, Amy Neff (April 26, 2013). "'Old Main' played important role in history of psychiatry". Observer-Dispatch. GateHouse Media. Archived from the original on May 30, 2022. Retrieved April 18, 2015.

- ^ "The Straightjacket and Utica Crib: Diagnostik". University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics. The University of Iowa. November 2, 2001. Archived from the original on May 21, 2010. Retrieved April 14, 2015.

- ^ "About » Stanley Center For The Arts". Stanley Center for the Arts. Archived from the original on April 27, 2015. Retrieved April 20, 2015.

- ^ 보티니 & 데이비스 2007, 페이지 13.

- ^ a b "Hotel Utica – A History". Hotel Utica. Archived from the original on February 9, 2015. Retrieved April 18, 2015.

- ^ Tucker, Libby (2013). "New York's Haunted Bars". Voices. 39 (Spring–Summer). Archived from the original on April 27, 2015. Retrieved April 20, 2015.

- ^ a b "Parks and Recreation". City of Utica. Archived from the original on April 10, 2015. Retrieved April 19, 2015.

- ^ "Parks & Open Spaces". www.cityofutica.com. Archived from the original on September 23, 2015. Retrieved August 21, 2015.

- ^ Vincent (January 1, 2007). Lin Smith, Vincent; Waller, Sydney (eds.). Sculpture Space: The Book : for the Artists and Individuals who are Part of the Sculpture Space Story. Thomas Piché, Sculpture Space (Studio). Sculpture Space, Incorporated. pp. 63–65. ISBN 978-0-9795-9690-2.

- ^ "Memorial Parkway Explore Our Parks Central New York Conservancy Mohawk Valley". Central New York Conservancy. Archived from the original on April 24, 2015. Retrieved April 20, 2015.

- ^ "Proctor Park". Oneida County Historical Society. Archived from the original on 9 April 2015. Retrieved 19 April 2015.

- ^ "Explore Our Parks in Utica, New York". Central New York Conservancy. Archived from the original on April 26, 2015. Retrieved April 20, 2015.

- ^ Pitarresi, John (December 22, 2012). "Val Bialas Sports Center: Let it snow, let it snow, let it snow". Observer-Dispatch. GateHouse Media. Retrieved April 19, 2015.

- ^ "Parks & Open Spaces". City of Utica. Archived from the original on April 11, 2015. Retrieved April 19, 2015.

- ^ 토마스 2003, 156쪽

- ^ "Centro Utica". Centro. April 1, 2013. Archived from the original on March 18, 2015. Retrieved March 21, 2015.

- ^ "Central New York - Weekday Line Runs" (PDF). Birnie Bus Service, Inc. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 26, 2015. Retrieved April 7, 2015.

- ^ "Greyhound.com, Utica, NY". Greyhound. Archived from the original on December 13, 2015. Retrieved April 7, 2015.

- ^ "Central New York - Saturday Line Runs" (PDF). Birnie Bus Service, Inc. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 13, 2015. Retrieved April 7, 2015.

- ^ a b 토마스 2003, 페이지 114–115.

- ^ Thomas 2003, 페이지 114.

- ^ Report on State arterial route plans in the Utica urban area. University of Michigan: New York State Department of Public Works. 1950.

- ^ "Google Maps". Google Maps. Archived from the original on May 30, 2022. Retrieved August 22, 2015.

- ^ "National Grid - 2002 News Releases". nationalgridus.com. Archived from the original on April 27, 2015. Retrieved April 21, 2015.

- ^ "New York Transco Transmission Projects". New York State Electric & Gas. Archived from the original on April 11, 2015. Retrieved April 21, 2015.

- ^ "Major Transmission Facilities Included In and Excluded From the Transmission Revenue Requirement" (PDF). New York Power Authority. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 March 2015. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- ^ Kemble, William J. (November 16, 2013). "Proposed power line through Mid-Hudson region stirs concerns". The Daily Freeman. 21st Century Media. Archived from the original on May 18, 2015. Retrieved April 21, 2015.

- ^ Roth, Amy (September 18, 2014). "Mini electric stations, such as at Faxton St. Luke's, being touted". Observer-Dispatch. GateHouse Media. Archived from the original on May 30, 2022. Retrieved April 21, 2015.

- ^ Zeman, F. (September 11, 2012). Metropolitan Sustainability: Understanding and Improving the Urban Environment. Elsevier. p. 544. ISBN 978-0-8570-9646-3.

- ^ Miner, Dan (January 26, 2012). "Utica forming panel to study possibility of new power system". Observer-Dispatch. GateHouse Media. Retrieved April 21, 2015.

- ^ "Proceeding To Examine Policies Regarding the Expansion of Natural Gas Service Case 12-G-0297" (PDF). New York State Public Service Commission. National Grid. January 9, 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 18, 2015. Retrieved April 21, 2015.

- ^ Handelman, David. "National Grid requests $400,000 from city". Observer-Dispatch. Retrieved April 21, 2015.

- ^ "Service Area". New York State Electric & Gas. Archived from the original on April 14, 2015. Retrieved April 21, 2015.

- ^ "City of Utica Garbage & Recycling: Collection & Disposal Information" (PDF). Oneida-Herkimer Solid Waste Authority. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 27, 2015. Retrieved April 21, 2015.

- ^ "About Us » Oneida-Herkimer Solid Waste Authority". Oneida-Herkimer Solid Waste Authority. Archived from the original on April 27, 2015. Retrieved April 21, 2015.

- ^ a b "Water Quality". Mohawk Valley Water Authority. Archived from the original on April 27, 2015. Retrieved April 20, 2015.

- ^ a b "Water Quality Report 2014" (PDF). Mohawk Valley Water Authority. 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 27, 2015. Retrieved April 20, 2015.

- ^ Cooper, Elizabeth (September 27, 2015). "Region boasts plentiful, clean water". Observer Dispatch. Archived from the original on May 30, 2022. Retrieved September 27, 2015.

- ^ a b "About the Mohawk Valley Health System". Mohawk Valley Health System. Archived from the original on April 27, 2015. Retrieved April 21, 2015.

- ^ Roth, Amy Neff (October 27, 2023). "Wynn Hospital opens Sunday: What you need to know". Utica Observer-Dispatch. Retrieved October 30, 2023.

- ^ a b c Roth, Amy Neff (October 30, 2023). "'Bittersweet' Sunday as St. Luke's, St. Elizabeth close, Wynn Hospital opens". Utica Observer Dispatch. Retrieved October 30, 2023.

- ^ "Fact Sheet". Mohawk Valley Health System. Archived from the original on April 27, 2015. Retrieved April 21, 2015.

- ^ "Campuses / SUNY Polytechnic Institute (formerly SUNYIT)". The State University of New York. Archived from the original on May 30, 2022. Retrieved April 18, 2015.

- ^ "SUNY Graduate Campuses". SUNY. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- ^ "About MVCC". Mohawk Valley Community College. Archived from the original on April 19, 2015. Retrieved April 24, 2015.

- ^ "Utica Central New York SUNY Empire State College". www.esc.edu. Archived from the original on August 23, 2015. Retrieved August 22, 2015.

- ^ "About Utica College". Utica College. Archived from the original on April 8, 2015. Retrieved April 18, 2015.

- ^ "History St. Elizabeth College of Nursing Utica, NY". St. Elizabeth College of Nursing. Archived from the original on May 11, 2015. Retrieved April 24, 2015.

- ^ "Pratt BFA Degrees Top Ranked Design & Fine Arts Programs » PrattMWP". PrattMWP College of Art and Design. Archived from the original on April 19, 2015. Retrieved April 24, 2015.

- ^ Amy Roth, Utica Observer-Dispatch (December 5, 2016). "Utica School of Commerce closing after 120 years". Utica Observer-Dispatch. Archived from the original on May 30, 2022. Retrieved December 30, 2016.

- ^ "Utica City School District". Federal Education Budget Project. New America Foundation. 2012. Archived from the original on June 26, 2015. Retrieved April 17, 2015.

- ^ Scott Thomas, G (June 25, 2015). "Utica scores highest in Upstate New York for racial diversity in public schools". Buffalo Business First. American City Business Journals. Archived from the original on June 26, 2015. Retrieved June 25, 2015.

- ^ Tracey, Sarah (April 5, 2014). "UFA to celebrate 200 years of memories, milestones". Observer-Dispatch. GateHouse Media. Archived from the original on May 30, 2022. Retrieved April 19, 2015.

- ^ NDHS. "School History". Notre Dame High School website. Archived from the original on April 16, 2007. Retrieved May 11, 2007.

- ^ "Library History". Utica Public Library. Retrieved August 23, 2023.

- ^ "About MYLS". Mid York Library System. Archived from the original on January 12, 2016. Retrieved June 18, 2015.

- ^ "Utica Comets to join AHL in 2013-14". TheAHL.com. American Hockey League. June 14, 2013. Archived from the original on November 4, 2013. Retrieved June 14, 2013.

- ^ "Introducing the Utica Comets of the AHL ProHockeyTalk". Archived from the original on September 6, 2015. Retrieved December 13, 2015.

- ^ "United Hockey League history and statistics at hockeydb.com". hockeydb.com. Archived from the original on April 25, 2015. Retrieved April 20, 2015.

- ^ "THE MASL IS COMING TO UTICA - Major Arena Soccer League". June 13, 2018. Archived from the original on June 14, 2018. Retrieved September 1, 2018.

- ^ Worth, Richard (February 26, 2013). Baseball Team Names: A Worldwide Dictionary, 1869-2011. McFarland. p. 311. ISBN 978-0-7864-6844-7.

- ^ "Overview". SUNY Poly Athletics. Archived from the original on September 5, 2015. Retrieved August 19, 2015.

- ^ "Overview". Hamilton College. Archived from the original on September 6, 2015. Retrieved August 19, 2015.

- ^ "Sports Information". Utica College Pioneers. Archived from the original on September 8, 2015. Retrieved August 19, 2015.

- ^ "Mohawk Valley Community College". NJCAA. Archived from the original on December 10, 2015. Retrieved August 19, 2015.

- ^ "About The Herkimer Generals Athletic Program". www.herkimergenerals.com. Archived from the original on September 8, 2015. Retrieved August 20, 2015.

- ^ "WKTV bringing CBS affiliation to Utica". WKTV. October 26, 2015. Archived from the original on November 26, 2015. Retrieved December 4, 2015.

- ^ "About TWC News". TWC News. Archived from the original on April 19, 2015. Retrieved April 19, 2015.

- ^ "Dish Network to Become First Pay-TV Provider to Offer Local Broadcast Channels in All 210 Local Television Markets in the United States" (PDF). Dish Network - Investor Relations. Comtex News Network. May 27, 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 19, 2015. Retrieved April 19, 2015.

- ^ "Get DirecTV in Utica". DirecTV. Archived from the original on March 24, 2015. Retrieved April 19, 2015.

- ^ Thomas 2003, 8페이지

- ^ 토마스 2003, 121쪽.

- ^ a b Lynn, Naomi (January 6, 2015). "Utica Gets Plenty of Attention In The Entertainment World: These TV Shows And Movies Prove Utica Is More Popular Than You Think". lite98.7. Townsquare Media. Archived from the original on April 19, 2015. Retrieved April 19, 2015.

- ^ Ginsberg, Allen (1956). Howl and Other Poems. City Light Books. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-8728-6017-9.

- ^ Herbert, Geoff (September 18, 2013). "Night Ranger, Gordie Howe and 'Slap Shot' stars coming to Utica Comets' first home game". Syracuse.com. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved August 19, 2015.

- ^ Fran Perritano (May 28, 2010). "'Hanson Brothers' will return to Utica Aud". Utica Observer-Dispatch. Archived from the original on February 9, 2013. Retrieved September 12, 2010.

서지학

- Bagg, M. M. (1892). Memorial History of Utica, N.Y.: From Its Settlement to the Present Time. Cornell University Library: D. Mason & Co. Publishers. OCLC 1837599.

- Bottini, Joseph P.; Davis, James L. (2007). Utica. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-5496-9.

- Childs, L. C. (1900). Outline History of Utica and Vicinity. Utica, New York: New Century Club. OCLC 1558992.

- Switala, William J. (2006). Underground Railroad in New Jersey and New York. Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-3258-1.

- Thomas, Alexander R. (2003). In Gotham's Shadow. State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-5595-1.

- Thomas, Alexander R.; Smith, Polly J. (2009). Upstate Down: Thinking about New York and Its Discontents. University Press of America. ISBN 978-0-7618-4500-3.

더보기

- Bartholomew, Harland (1921). A Preliminary Report on Major Streets, Utica, New York. Willard Press. OCLC 682139143.

- 브릭스, 존 W. 이탈리아어 구절: Utica NY, Rochester NY 및 Kansas City, MO, 1890-1930의 세 개의 미국 도시(Yale UP, 1978)로의 이민자. 온라인상의

- Ferris, T. Harvey (1913). Utica, the Heart of the Empire State. Library of Congress. ASIN B00486TJ2C.

- Pula, James S. (1994). Ethnic Utica. Ethnic Heritage Studies Center, Utica College of Syracuse University. ISBN 978-0-9668-1785-0.

- Koch, Daniel (2023). 오니다스의 땅: 뉴욕주 중부와 미국의 창조, 선사시대부터 현재까지. 올버니: 뉴욕 주립대 출판부입니다.

Utica Public Library (1932). A Bibliography of the History and Life of Utica; a Centennial Contribution. Goodenow Print. Co. OCLC 1074083.

외부 링크

- NYPL Digital Gallery, Utica 관련 아이템, 뉴욕

- 뉴욕주 유티카 관련 물품, 의회도서관, 인쇄 및 사진과

- 마천루 페이지, 뉴욕 유티카의 마천루 도표