미국 연방 대법원

Supreme Court of the United States| 미국 연방 대법원 | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| 38°53'26 ″ N 77°00'16 ″W / 38.89056°N 77.00444°W | |

| 설립된 | 1789년 3월 4일;[1] |

| 위치 | 1 First Street, NE, Washington D.C., U.S. |

| 좌표 | 38°53'26 ″ N 77°00'16 ″W / 38.89056°N 77.00444°W |

| 구성방법 | 상원 인준으로 대통령 지명 |

| 인증자 | 미국 헌법 |

| 심사기장 | 종신 재직권 |

| 자리수 | 9, 법령으로 |

| 웹사이트 | 미국 연방 대법원 |

| 미국 대법원장 | |

| 현재의 | 존 로버츠 |

| 부터 | 2005년9월29일 |

| 이 기사는 에 관한 시리즈의 일부입니다. |

| 대법원 미국의 |

|---|

|

| 더 코트 |

| 現멤버십 |

| |

| 재판관 목록 |

| |

| 법원업무담당자 |

| 헌법 미국의 |

|---|

|

| 개요 |

| 원칙 |

| 정부구조 |

| 개인의 권리 |

| 이론. |

미국 연방 대법원(SCOTUS)은 미국 연방 사법부에서 가장 높은 법원입니다. 그것은 모든 미국 연방 법원 사건과 미국 헌법 또는 연방법에 대한 의문을 불러일으키는 주 법원 사건에 대한 궁극적인 항소 관할권을 가지고 있습니다. 또한 좁은 범위의 사건, 특히 "대사, 기타 공공 장관 및 영사, 국가가 당사자가 되어야 하는 사건에 영향을 미치는 모든 사건"에 대한 원래 관할권을 가지고 있습니다.[2] 법원은 사법심사권, 헌법조항 위반에 대한 법령 무효화 권한을 보유하고 있습니다. 또한 헌법이나 법률을 위반했다는 이유로 대통령의 지시를 무시할 수 있습니다.[3][non-primary source needed]

미국 헌법 제3조에 의해 제정된 대법원의 구성과 절차는 최초 제1차 의회에 의해 1789년 사법법을 통해 제정되었습니다. 재판부는 9명의 재판관으로 구성되어 있습니다: 미국 대법원장과 8명의 부재판관들이 워싱턴 D.C.에 있는 대법원 건물에서 재판관들이 만납니다. 재판관들은 종신 재직권이 있는데, 이는 그들이 죽거나, 은퇴하거나, 사임하거나, 탄핵되어 공직에서 물러날 때까지 재판부에 남아 있다는 것을 의미합니다.[4] 공석이 발생하면 대통령은 상원의 조언과 동의를 얻어 새로운 재판관을 임명합니다. 각 재판관은 법원에서 주장하는 사건을 결정할 때 한 표를 행사합니다. 다수일 때 법원의 의견서를 누가 작성할지는 대법원장이 결정하고, 그렇지 않으면 다수일 때 가장 고위직인 대법관이 의견서 작성 임무를 부여합니다.

대법원은 매년 평균 약 7,000건의 증명서 작성 청원을 받지만, 80건 정도만 부여하고 있습니다.[5]

역사

1787년 헌법협약의 대표자들이 국가 사법부의 기준을 마련한 것은 입법부와 행정부의 삼권분립 문제를 논의하던 중이었습니다. 정부의 "제3의 분파"를 만드는 것은 새로운 생각이었습니다[citation needed]; 영국 전통에서, 사법 문제는 왕실(집행) 권위의 한 측면으로 다루어져 왔습니다. 일찍이 강력한 중앙 정부를 두는 것에 반대하는 대표단은 주 법원에 의해 국가법이 집행될 수 있다고 주장했고, 제임스 매디슨을 포함한 다른 이들은 주 의회가 선택한 재판소로 구성된 국가 사법 기관을 주장했습니다. 사법부가 거부권을 행사하거나 법률을 개정할 수 있는 집행부의 권한을 견제하는 역할을 해야 한다고 제안했습니다.[citation needed]

결국 틀은 미국 헌법 제3조에 있는 사법부의 대략적인 윤곽만을 스케치하여 "하나의 대법원, 그리고 의회와 같은 열등한 법원은 때때로 또는 일정하고 확립할 수 있다"는 연방 사법권을 부여함으로써 타협했습니다.[6][7][better source needed] 그들은 대법원의 정확한 권한과 특권, 그리고 사법부 전체의 조직을 묘사하지 않았습니다.[citation needed]

제1차 미국 의회는 1789년 사법법을 통해 연방 사법부의 상세한 조직을 제공했습니다. 국내 최고의 사법 재판소인 대법원은 수도에 위치하게 되어 있었고, 처음에는 대법원장과 5명의 대법관으로 구성될 예정이었습니다. 이 법은 또한 전국을 사법 구역으로 나누었고, 이들은 차례로 순회구로 조직되었습니다. 재판관들은 "순회로"를 타고 그들이 할당된 사법 구역에서 1년에 두 번 순회 법정을 열도록 요구되었습니다.[8][non-primary source needed]

법안에 서명한 직후, 조지 워싱턴 대통령은 존 제이를 대법원장으로 지명했고 존 러틀리지, 윌리엄 쿠싱, 로버트 H. 해리슨, 제임스 윌슨, 존 블레어 주니어를 대법관으로 지명했습니다. 6명 모두 1789년 9월 26일 상원에 의해 확정되었습니다. 그러나 해리슨은 복무를 거부했고, 이후 워싱턴은 제임스 이레델을 그의 자리에 지명했습니다.[9][non-primary source needed]

대법원은 1790년 2월 2일부터 2월 10일까지 당시 미국의 수도였던 뉴욕시의 왕립거래소에서 창립총회를 열었습니다.[10] 두 번째 세션은 1790년 8월에 그곳에서 열렸습니다.[11] 법원의 초기 세션은 첫 번째 사건이 1791년까지 도달하지 못했기 때문에 조직 절차에 전념했습니다.[8] 1790년 미국의 수도가 필라델피아로 옮겨졌을 때, 대법원도 그렇게 했습니다. 독립기념관에서 처음 만난 후, 법원은 시청에 회의실을 설치했습니다.[12]

초기시작

제이, 러틀리지 및 엘스워스 (1789–1801) 대법원장 하에서 법원은 거의 사건을 심리하지 않았습니다. 첫 번째 결정은 웨스트 대 반스 (1791)로 절차와 관련된 사건이었습니다.[13] 재판부는 당초 구성원이 6명에 불과했기 때문에 다수결로 결정할 때마다 3분의 2(4대 2)의 찬성으로 결정했습니다.[14] 그러나 의회는 1789년 재판관 4명의 정족수를 시작으로 항상 법원의 정회원 이하의 결정을 허용해 왔습니다.[15] 법원은 자신의 집이 없고 권위가 거의 없었는데,[16] 이 상황은 수정헌법 11조의 채택으로 2년 만에 뒤바뀐 이 시대 최고 권위의 사건인 치솔름 대 조지아 (1793)의 도움을 받지 못했습니다.[17]

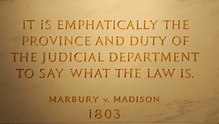

마셜 법원(1801-1835) 기간 동안 법원의 권력과 명성은 크게 높아졌습니다.[18] 마셜 아래에서 법원은 헌법의 최고 설명자로 자신을 명시하고(Marbury v. Madison)[20][21] 연방 정부와 주들 사이의 힘의 균형에 형태와 실질을 부여하는 몇 가지 중요한 헌법 판결들을 내리는 [19]등 의회의 행위들에 대한 사법적 검토의 권한을 확립하고, 특히 마르틴 대. 헌터 레시, 매컬록 대 메릴랜드, 기븐스 대 오그든.[22][23][24][25]

마셜 법원은 또한 각 재판관들이 영국 전통의 잔재인 [26]자신의 의견서를 발표하고 [27]대신 단일 다수 의견서를 발표하는 관행을 종식시켰습니다.[26] 또한 마셜 재임 기간 동안, 비록 법원의 통제를 벗어나긴 했지만 1804년부터 1805년까지 새뮤얼 체이스 대법관의 탄핵과 무죄 판결은 사법 독립의 원칙을 공고히 하는 데 도움이 되었습니다.[28][29]

태니에서 태프트로

Taney Court (1836–1864)는 Sheldon v. Sill과 같은 몇 가지 중요한 판결을 내렸는데, 이 판결은 의회가 대법원이 심리할 수 있는 주제를 제한할 수는 없지만, 특정 주제를 다루는 사건을 심리하는 것을 막기 위해 하급 연방 법원의 관할권을 제한할 수 있다고 판결했습니다.[30] 그럼에도 불구하고, 그것은 주로 미국 남북 전쟁을 촉발시키는 데 도움을 [31]주었던 준드 스콧 대 샌드포드 판결로 기억됩니다.[32] 재건 시대에 체이스, 웨이트, 풀러 법원 (1864–1910)은 헌법에[25] 대한 새로운 남북 전쟁 수정안을 해석하고 실질적인 적법 절차 (Lochner v. New York;[33] Adair v. United States)의 교리를 발전시켰습니다.[34] 법원의 규모는 1869년에 마지막으로 변경되었는데, 이때 9개로 설정되었습니다.

화이트 법원과 태프트 법원(1910–1930) 하에서, 법원은 수정헌법 제14조가 새로운 반독점법(Standard Oil Co. of New Jersey v. United States)과 씨름하면서 [35]각 주(Gitlow v. New York)에 대한 권리장전(Bill of Rights)의 일부 보장을 포함했다고 주장했습니다. 군 징집의 합헌성을 지지하고(선택적 징집법 사건),[36] 실질적인 적법 절차 원칙을 최초의 아포지(Adkins v. Children's Hospital)에 가져갔습니다.[37]

뉴딜 시대

휴즈, 스톤, 빈슨 법원(1930-1953) 동안 법원은 1935년에[38] 자체적으로 수용을 얻었고 헌법에 대한 해석을 변경하여 프랭클린 D 대통령을 용이하게 하기 위해 연방 정부의 권한을 더 넓게 읽었습니다. 루스벨트의 뉴딜 정책(가장 눈에 띄는 것은 West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parish, Wickard v. Filburn, United States v. Darby, United States v.[39][40][41] Butler). 제2차 세계 대전 동안 조정은 일본계 미국인들의 억류를 지지하면서 정부 권력에 계속 호의를 표했습니다. 미국)와 의무적인 충성 서약(Minersville School District v. Gobitis). 그럼에도 불구하고 고비티스는 곧 거절당했고(West Virginia State Board v. Barnette), 강철 압수 사건은 친정부적 경향을 제한했습니다.

워렌 법원(1953-1969)은 헌법상의 시민적 자유의 힘을 극적으로 확장시켰습니다.[42] 그것은 공립학교에서의 분리가 수정헌법 제14조 (브라운 대 교육위원회, 볼링 대 샤프, 그린 대 카운티 학교 Bd.)[43]의 평등 보호 조항을 위반하며, 입법 구역은 대략 인구가 동일해야 한다고 주장했습니다 (레이놀즈 대 심스). 그것은 사생활에 대한 일반적인 권리(Griswold v. Connecticut)를 인정했고,[44] 공립학교에서 종교의 역할을 제한했는데, 가장 눈에 띄는 것은 Engel v. Vitale와 Abington School District [45][46]v. Schempp는 주로 Mapp v. 주에 대한 권리장전의 대부분의 보장을 통합했습니다. 오하이오(배제규정)와 기디언 대 웨인라이트(변호인을 선임할 권리),[47][48] 그리고 범죄혐의자들이 경찰에 의해 이 모든 권리를 인정받도록 요구했습니다(미란다 대 애리조나).[49] 동시에 법원은 공인에 의한 명예훼손 소송(뉴욕타임즈 대 설리번)을 제한하고 정부에 독점금지 소송의 연속적인 승리를 제공했습니다.[50]

버거, 렌퀴스트, 로버츠

버거 법원(Burger Court, 1969–1986)은 보수적인 변화를 보였습니다.[51] 또한 낙태법을 무효화하기 위해 그리스월드의 사생활에 대한 권리를 확대했지만(Roe v. Wade),[52] 긍정적인 조치(캘리포니아 대학교 리젠트 v. Bakke)[53]와 캠페인 금융 규제(Buckley v. Valeo)에 대해서는 깊이 의견을 나누었습니다.[54] 또한 사형제도에 대해서도 손을 흔들며, 처음에는 대부분의 신청에 결함이 있다고 판결했지만(Furman v. Georgia),[55] 나중에는 사형 자체가 위헌이 아니라고 판결했습니다(Gregg v. Georgia).[55][56][57]

렌퀴스트 법원(1986–2005)은 연방주의의 사법 집행을 부활시킨 것으로 유명하며,[58] 헌법의 긍정적인 권한 부여의 한계(미국 대 로페즈)와 그러한 권한에 대한 제한의 힘(세미놀 부족 대 플로리다, 보어네 대 플로레스)을 강조했습니다.[59][60][61][62][63] 동성애자 주립학교를 평등보호 위반으로, 동성애 금지법을 실체적 적법절차 위반으로 부결시켰습니다(미국 대 버지니아). 텍사스)[64]와 선 항목 거부권(클린턴 대 뉴욕)을 지지했지만 학교 바우처(젤먼 대 시몬스-해리스)를 지지했고 낙태법에 대한 로의 제한(계획된 부모 대 케이시)을 재확인했습니다.[65] 2000년 미국 대통령 선거 중 재검표를 끝낸 부시 대 고어 법원의 결정은 정당한 승자와 이 판결이 선례가 되어야 하는지에 대한 논쟁이 진행 중인 가운데 특히 논란이 되고 있습니다.[66][67][68][69]

로버츠 법원(2005-현재)은 렌퀴스트 법원보다 더 보수적이고 논란이 많은 법원으로 간주됩니다.[70][71][72][73] 주요 판결 중 일부는 연방 우선주의 (Wyeth v. Levine), 민사 절차 (Twombly–Iqbal), 투표권 및 연방 사전 허가 (Shelby County–Brnovich), 낙태 (Gonzales v. Carhart and Dobbs v. Jackson Women Health Organization),[74] 기후 변화 (Massachusetts v. EPA), 동성 결혼 (미국 v. 윈저와 오버게펠 대 호지스), 시티즌 유나이티드 대와 같은 권리장전. 연방 선거 위원회와 번영 재단을 위한 미국인들 대 본타(제1차 수정),[75] 헬러-맥도날드-브뤼엔(제2차 수정),[76] 바제 대 리스(제8차 수정).[77][78]

구성.

지명, 확정 및 선임

임명 조항으로 알려진 미국 헌법 제Ⅱ조 제2항 제2호는 대통령이 임명하고, 미국 상원의 확인(자문 및 동의)을 받아 대법관을 포함한 공무원을 임명할 수 있도록 권한을 부여하고 있습니다. 이 조항은 헌법에 내재된 견제와 균형의 체계를 보여주는 한 예입니다. 대통령은 지명할 수 있는 본회의 권한을 가지고 있고, 상원은 지명자를 거부하거나 인준할 수 있는 본회의 권한을 가지고 있습니다. 헌법은 나이, 시민권, 거주지 또는 이전의 사법 경험과 같은 재판관으로서 복무할 자격을 설정하지 않으므로 대통령은 누구든지 복무할 사람을 지명할 수 있으며 상원은 대통령이 선택할 수 있는 자격을 설정하거나 달리 제한할 수 없습니다.[79][80][81]

현대에 들어서서 인준 절차는 언론과 옹호 단체들로부터 상당한 관심을 받아왔는데, 이들은 상원의원들의 실적이 이 단체의 견해와 일치하는지 여부에 따라 지명자를 인준하거나 거부하도록 로비를 벌였습니다. 상원 법사위원회는 청문회와 표결을 통해 상원 전체에 긍정적, 부정적, 중립적인 보고서를 제출해야 하는지 여부를 결정합니다. 위원회가 후보자들을 직접 면담하는 관행은 비교적 최근의 일입니다. 위원회에 처음 등장한 지명자는 1925년 Harlan Fiske Stone으로, 월스트리트와의 연관성에 대한 우려를 잠재우고자 했으며, 현대적인 심문 관행은 1955년 John Marshall Harlan II에서 시작되었습니다.[82] 위원회가 지명을 보고하면 전체 상원이 이를 고려합니다. 상원은 1987년 로널드 레이건 대통령이 지명한 로버트 보크 대법관 후보 12명을 명시적으로 거부했습니다.

상원 규칙이 반드시 위원회에서 네거티브 또는 동점 투표를 허용하여 지명을 차단하는 것은 아니지만, 2017년 이전에는 전체 상원에서 토론이 시작되면 필리버스터로 지명이 차단될 수 있습니다. 린든 B 대통령. 존슨이 1968년 얼 워렌의 뒤를 이어 대법관에 아베 포타스를 임명한 것은 대법원 지명자가 처음으로 성공한 필리버스터였습니다. 여기에는 포르타스의 윤리와 관련된 공화당 상원의원과 민주당 상원의원이 모두 포함되었습니다. 도널드 트럼프 대통령이 안토닌 스캘리아의 사망으로 공석이 된 자리에 닐 고서치를 지명한 것이 두 번째입니다. 포르타스 필리버스터와 달리 민주당 상원의원들만 보수적인 사법철학을 인정하고 공화당 다수당이 공석을 채우기 위해 버락 오바마 대통령의 메릭 갈랜드 지명을 수락하지 않았다는 이유로 고르수흐 지명에 반대표를 던졌습니다.[83] 이로 인해 공화당 다수당은 규칙을 변경하고 대법원 지명을 위한 필리버스터를 없애게 되었습니다.[84]

모든 대법관 지명자가 상원에서 원내 투표를 받은 것은 아닙니다. 일반적으로 상원이 지명자를 거부할 것이 분명하기 때문에 대통령은 실제 인준 투표가 일어나기 전에 지명을 철회할 수 있습니다. 이것은 2005년 조지 W. 부시 대통령이 해리엇 마이어스를 지명하면서 발생했습니다. 상원은 또한 세션이 끝나면 만료되는 지명에 대해 조치를 취하지 않을 수 있습니다. 1954년 11월 드와이트 아이젠하워 대통령이 처음 지명한 존 마샬 할란 2세는 상원에서 처리되지 않았고, 아이젠하워는 1955년 1월 할란을 재지명했고, 두 달 후 할란은 확정되었습니다. 가장 최근에는 2017년 1월 지명이 만료되면서 2016년 3월 메릭 갈랜드 지명에 대해 상원이 조치를 취하지 못했고, 공석은 트럼프 대통령의 임명권자인 닐 고르수치가 채웠습니다.[85]

상원이 지명을 확정하면 대통령은 지명자가 취임하기 전에 법무부 직인을 날인해야 하는 위원회를 준비하고 서명해야 합니다.[86] 준사법위원의 연공서열은 확정일자나 선서일자가 아니라 위촉일자를 기준으로 합니다.[87] 위임을 받은 후 임명자는 공식 직무를 수행하기 전에 두 가지 규정된 선서를 해야 합니다.[88] 선서의 중요성은 Edwin M의 사례에서 강조됩니다. 스탠튼. 1869년 12월 20일 상원의 승인을 받고 율리시스 S. 그랜트 대통령에 의해 준법무관으로 적법하게 임명되었지만 스탠튼은 규정된 선서를 하기 전인 12월 24일에 사망했습니다. 따라서 그는 법원의 일원이었던 것으로 간주되지 않습니다.[89][90]

1981년 이전에는 재판관들의 인준 절차가 대체로 빨랐습니다. 트루먼부터 닉슨 행정부에 이르기까지 일반적으로 판사들은 한 달 안에 승인을 받았습니다. 레이건 행정부부터 현재까지 그 과정은 훨씬 더 오래 걸렸고 일부에서는 의회가 과거보다 더 정치적인 역할을 하는 판사들을 보고 있기 때문이라고 생각합니다.[91] 의회조사국에 따르면 1975년 이후 상원 최종 표결까지 평균 일수는 67일(2.2개월)인 반면 중앙값은 71일(2.3개월)입니다.[92][93]

휴회약속

상원이 휴회할 때 대통령은 공석을 채우기 위해 임시 약속을 할 수 있습니다. 휴회 임명자는 다음 상원 회기(2년 미만)가 끝날 때까지만 재임합니다. 상원은 이들이 계속 재직할 후보자를 확정해야 합니다. 두 명의 대법원장과 11명의 대법관 중에서 존 러틀리지 대법원장만 이후에 확정되지 않았습니다.[94]

드와이트 D 이후 미국 대통령은 없습니다. 아이젠하워는 법원에 휴회 약속을 했고, 이런 관행은 연방 하급 법원에서도 드물고 논란이 되고 있습니다.[95] 1960년, 아이젠하워가 세 번의 그러한 임명을 한 후, 상원은 법원에 대한 휴회 임명은 "비정상적인 상황"에서만 이루어져야 한다는 "상원의 감각" 결의안을 통과시켰습니다.[96] 그러한 결의안은 법적 구속력이 없지만 행정부의 행동을 지도하기를 바라는 의회의 견해의 표현입니다.[96][97]

노엘 캐닝(National Labor Relations Board v. Noel Canning)의 2014년 결정은 대통령이 휴회 임명(대법원 임명 포함)을 할 수 있는 능력을 제한했습니다; 법원은 상원이 회기 중이거나 휴회 중일 때 상원이 결정한다고 판결했습니다. 브레이어 대법관은 법원에 기고한 글에서 "휴회 임명 조항의 목적상 상원이 자신의 규칙에 따라 상원 사업을 거래할 수 있는 능력을 유지한다면 상원이 그것을 말할 때 회기 중이라고 생각합니다."라고 말했습니다.[98] 이 판결은 상원이 친 형식 세션을 사용하여 휴회 임명을 방지할 수 있도록 허용합니다.[99]

재직기간

대법관의 종신 재직권은 미국 대법관과 로드 아일랜드 주 대법관에게만 주어지며, 다른 모든 민주 국가와 미국의 모든 주에서는 임기 제한 또는 의무 정년이 설정되어 있습니다.[100] 래리 사바토(Larry Sabato)는 다음과 같이 썼습니다. "평생 종신 재직권의 보험성은 재판장에서 오래 근무하는 비교적 젊은 변호사들의 임명과 결합하여 과거 세대의 관점을 대변하는 고위 판사들을 현재의 관점보다 더 잘 배출합니다."[101]샌포드[101] 레빈슨은 장수를 바탕으로 한 의학적 악화에도 불구하고 자리를 지킨 대법관들에 대해 비판적인 입장을 보여왔습니다.[102] 제임스 맥그리거 번스(James MacGregor Burns)는 평생 재임 기간이 "대법원이 제도적으로 거의 항상 시대에 뒤떨어지는 중대한 시차를 초래했다"고 말했습니다.[103] 이러한 문제를 해결하기 위한 제안에는 레빈슨(Levinson[104])과 사바토[101][105](Sabato)가 제안한 대법관 임기 제한과 리처드 엡스타인(Richard Epstein)이 제안한 의무 정년 [106]등이 포함됩니다.[107] 연방주의자 78의 알렉산더 해밀턴(Alexander Hamilton)은 종신 재직권의 한 가지 이점은 "임기의 영구성만큼 확고함과 독립성에 기여할 수 있는 것은 없다"고 주장했습니다.[108][non-primary source needed]

헌법 제3조 제1항은 재판관이 "선행 중에 직무를 수행하여야 한다"고 규정하고 있는데, 이는 사망할 때까지 평생 직무를 수행할 수 있음을 의미하는 것으로 이해되고, 나아가 이 문구는 일반적으로 재판관들이 자리에서 물러날 수 있는 유일한 길은 탄핵 절차를 거쳐 의회에 의해 결정된다는 의미로 해석됩니다. 헌법 제정자들은 재판관들의 해임 권한을 제한하고 사법 독립성을 보장하기 위해 선량한 행위 종신 재직권을 선택했습니다.[109][110][111] 질병이나 부상으로 인해 영구적으로 무력하지만 사임할 수 없는(또는 사임할 의사가 없는) 정의를 제거하기 위한 헌법적 장치는 존재하지 않습니다.[112] 지금까지 탄핵된 유일한 대법관은 1804년 사무엘 체이스였습니다. 하원은 그에 대한 8개의 탄핵 조항을 채택했지만, 그는 상원에서 무죄 판결을 받았고, 1811년 사망할 때까지 그 자리를 지켰습니다.[113] 현직 판사를 탄핵하려는 이후의 어떤 노력도 법사위에 회부하는 것 이상으로 진전되지 않았습니다. (예를 들어, 윌리엄 오). 더글러스는 1953년과 1970년 두 차례 청문회의 대상이었고 아베 포타스는 1969년 청문회가 조직되는 동안 사임했습니다.)

재판관들의 임기가 무기한이기 때문에 공석 시기를 예측할 수 없습니다. 1971년 9월 휴고 블랙과 존 마셜 할란 2세가 며칠 만에 떠난 것처럼 법원 역사상 공석 사이의 최단 기간처럼 때로는 빠르게 연속적으로 발생하기도 합니다.[114] 때때로 1994년부터 2005년까지 해리 블랙문의 은퇴 이후 윌리엄 렌퀴스트의 사망까지 11년의 기간과 같은 공석 사이에 매우 긴 시간이 흐릅니다. 이 기간은 법원 역사상 두 번째로 긴 공백 기간이었습니다.[115] 평균적으로 약 2년에 한 번씩 새로운 판사가 법원에 합류합니다.[116]

변동성에도 불구하고, 4명의 대통령을 제외한 모든 대통령들은 적어도 한 명의 재판관을 임명할 수 있었습니다. 비록 그의 후임자(존 타일러)가 대통령 임기 동안 약속을 했지만, 윌리엄 헨리 해리슨은 취임 한 달 만에 사망했습니다. 마찬가지로 재커리 테일러도 취임 후 16개월 만에 사망했지만, 후임자(밀러드 필모어)도 임기가 끝나기 전에 대법원 지명을 했습니다. 에이브러햄 링컨 암살 사건 이후 대통령이 된 앤드류 존슨은 법원의 규모를 축소함으로써 대법관 임명 기회를 거부당했습니다. 지미 카터(Jimmy Carter)는 선출된 대통령 중에서 최소한 한 번의 임기를 마치고 대법관을 임명할 기회 없이 퇴임한 유일한 사람입니다. 대통령 제임스 먼로, 프랭클린 D. 루스벨트와 조지 W. 부시는 각각 대법관을 임명할 기회 없이 임기를 채웠으나, 이후 임기 동안 임명을 했습니다. 한 번 이상의 임기를 채운 대통령 중에 임명할 기회가 적어도 한 번도 없이 간 적이 없습니다.

법원규모

세계에서 가장 작은 대법원 중 하나인 미국 대법원은 대법원장 1명과 대법관 8명 등 9명으로 구성되어 있습니다. 미국 헌법은 대법원의 규모를 명시하지 않았고, 법원 구성원에 대한 구체적인 입장도 명시하지 않았습니다. 헌법은 제1조 제3항 제6호에서 "대법원장"은 미국 대통령의 탄핵심판을 주재하여야 한다고 언급하고 있기 때문에 대법원장의 직무가 존재하는 것으로 추정하고 있습니다. 대법원의 규모와 구성원을 규정하는 권한은 1789년 사법부법을 통해 처음에는 대법원장과 5명의 대법관으로 구성된 6인의 대법원을 설립한 의회에 속한다고 가정해 왔습니다.

법원의 규모는 1801년 미드나잇 판사 법에 의해 처음 변경되었는데, 이 법은 다음 공석이 되면 법원의 규모를 5명으로 줄였지만, 1802년 사법법은 즉시 1801년 법을 무효화하여 공석이 발생하기 전에 법원의 규모를 6명으로 복원했습니다. 미국의 국경이 대륙을 가로질러 확장되고, 그 당시의 대법관들이 서킷을 타야 했기 때문에, 거친 지형 위에서 말이나 마차를 타고 긴 여행을 해야 하는 고된 과정으로, 수개월 동안 집을 떠나는 시간이 길어졌습니다. 의회는 대법관을 추가하여 대법관과 대법원장의 의석이 1807년에 7석, 1837년에 9석, 1863년에 10석이 되도록 했습니다.[117][118]

체이스 대법원장의 명령에 따라, 그리고 민주당의 앤드류 존슨의 권한을 제한하려는 공화당 의회의 시도로, 의회는 은퇴할 다음 3명의 대법관이 교체되지 않을 것이며, 이것은 자연 감소에 의해 7명의 대법관으로 재판관을 줄일 것이라고 규정하면서, 1866년 사법 회로법을 통과시켰습니다. 그 결과 1866년에 한 자리, 1867년에 두 번째 자리가 없어졌습니다. 존슨이 퇴임한 직후,[119] 공화당 소속의 율리시스 S. 그랜트 신임 대통령은 1869년 사법부법에 서명했습니다. 이로써 재판관 수는 9명으로[120] 늘어났고(이후에도 남아 있음), 그랜트는 즉시 2명의 재판관을 추가로 임명할 수 있었습니다.

프랭클린 D 대통령. 루즈벨트는 1937년에 법원을 확장하려고 시도했습니다. 그의 제안은 70세 6개월에 도달하고 퇴직을 거부한 현직 대법관 한 명당 최대 15명의 재판관을 추가로 임명하는 것을 상정했습니다. 이 제안은 표면적으로는 고령 판사들의 재판부 부담을 덜어주기 위한 것이었지만, 실제 목적은 루스벨트의 뉴딜 정책을 지지할 판사들로 법원을 '포장'하려는 노력으로 널리 이해됐습니다.[121] 보통 "법정 포장 계획"이라고 불리는 이 계획은 루스벨트의 민주당 의원들이 위헌이라고 믿으면서 의회에서 실패했습니다. 그것은 상원에서 70대 20으로 패배했고, 상원 법사위원회는 그 제안이 "미국의 자유민의 자유 대표들에게 다시는 그것의 평행선이 제시되지 않을 정도로 강력하게 거절되었다"는 것이 "우리의 입헌 민주주의의 지속에 필수적"이라고 보고했습니다.[122][123][124][125]

도널드 트럼프 대통령 재임 기간 동안 법원에 대한 5대 4의 보수 다수가 6대 3의 슈퍼[126] 다수로 확대되면서 CNN의 조안 비스쿠픽은 공화당이 지난 18명의 대법관 중 14명을 임명하면서 1930년대 이후 가장 보수적인 법원으로 평가하게 되었습니다.[127] 일부 민주당 의원들은 불균형이라고 보는 부분을 고치기 위해 법원 규모를 확대해야 한다고 주장했습니다. 2021년 4월, 117차 의회에서 하원의 일부 민주당 의원들은 대법원을 9석에서 13석으로 확대하는 법안인 2021년 사법법을 발의했습니다. 당내 반발에 부딪혔고, 낸시 펠로시 하원의장은 이를 원내에 상정하는 것을 거부했습니다.[128][129] 2021년 1월 취임 직후 조 바이든은 대법원 개혁 가능성을 연구하기 위해 대통령 위원회를 설립했습니다. 위원회의 2021년 12월 최종 보고서는 논의되었지만 법원 규모 확대에 대한 입장은 밝히지 않았습니다.[130]

9명의 회원으로 구성된 미국 대법원은 세계에서 가장 작은 대법원 중 하나입니다. 데이비드 리트는 법원이 미국 크기의 국가의 관점을 대변하기에는 너무 작다고 주장합니다.[131] 변호사이자 법학자인 조나단 터리는 19명의 대법관을 지지하고 있으며, 대통령 임기당 2명의 새로운 구성원에 의해 법원이 점차 확장되어 미국 대법원은 다른 선진국 대법원과 비슷한 규모로 확장되었습니다. 재판부가 커지면 스윙 재판관의 권한이 줄어들고, 재판부가 '더 다양한 견해'를 갖도록 하고, 신임 재판관 인준도 정치적 논쟁을 덜 할 것이라고 말했습니다.[132][133]

회원가입

현직 대법관

현재 대법원에는 9명의 대법관이 있습니다: 존 로버츠 대법원장과 8명의 대법관입니다. 현재 법원 구성원 중 Clarence Thomas는 2024년 3월 29일 기준 11,846일(32세, 158일)의 재임 기간을 가진 최장수 대법관입니다. 가장 최근에 법원에 합류한 대법관은 Ketanji Brown Jackson으로, 4월 7일 상원의 인준을 받은 후 2022년 6월 30일에 임기가 시작되었습니다.[134]

| 정의 / 생년월일과 장소 | (당사자) 선임 | SCV | 나이 : | 시작일자 / 복무 기간 | 성공했다 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 시작 | 현재의. | ||||||

| (대법원장) 존 로버츠 1955년1월27일 버팔로, 뉴욕 | G. W. 부시 (R) | 78–22 | 50 | 69 | 2005년9월29일 18세 182일 | 렌퀴스트 |

| 클라렌스 토마스 1948년6월23일 핀포인트, 조지아 | G. H. W. 부시 (R) | 52–48 | 43 | 75 | 1991년10월23일 32세 158일 | 마셜 |

| 사무엘 알리토 1950년4월1일 트렌턴 | G. W. 부시 (R) | 58–42 | 55 | 73 | 2006년1월31일 18세 58일 | 오코너 |

| 소니아 소토마요르 1954년 6월 25일 뉴욕 시, 뉴욕 | 오바마 (D) | 68–31 | 55 | 69 | 2009년8월8일 14년 234일 | 소우터 |

| 엘레나 케이건 1960년4월28일 뉴욕 시, 뉴욕 | 오바마 (D) | 63–37 | 50 | 63 | 2010년8월7일 13년 235일 | 스티븐스 |

| 닐 고서치 1967년8월29일 덴버, 콜로라도 | 트럼프 (R) | 54–45 | 49 | 56 | 2017년4월10일 6년 354일 | 스칼리아 |

| 브렛 캐버노 1965년2월12일 워싱턴. | 트럼프 (R) | 50–48 | 53 | 59 | 2018년10월6일 5년 175일 | 케네디 |

| 에이미 코니 배럿 1972년1월28일 뉴올리언스, 루이지애나 | 트럼프 (R) | 52–48 | 48 | 52 | 2020년10월27일 3년 154일 | 긴즈버그 |

| 케탄지 브라운 잭슨 1970년9월14일 워싱턴. | 바이든 (D) | 53–47 | 51 | 53 | 2022년6월30일 1년 273일 | 브라이어 |

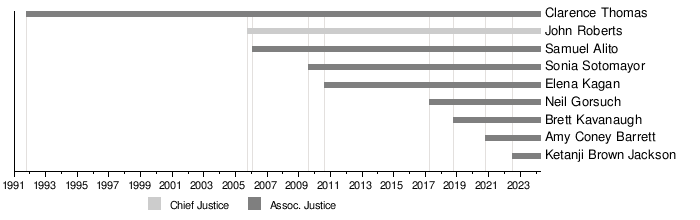

이 그래픽 타임라인은 각 현직 대법관의 재임 기간을 보여줍니다(대법원장은 재임 기간에 관계없이 모든 대법관에 대해 연공서열을 가지고 있기 때문에 연공서열이 아닙니다).

법원 인구통계

현재 재판부에는 남성 재판관 5명과 여성 재판관 4명이 있습니다. 재판관 9명 가운데 아프리카계 미국인 재판관 2명(토머스·잭슨 대법관)과 히스패닉계 재판관 1명(소토마요르 대법관)이 있습니다. 재판관 중 한 명은 적어도 한 명의 이민자 부모에게서 태어났습니다. 알리토 재판관의 아버지는 이탈리아에서 태어났습니다.[136][137]

최소 6명의 재판관이 로마 가톨릭 신자이고, 1명은 유대인이며, 1명은 개신교 신자입니다. Neil Gorsuch가 자신을 가톨릭 신자로 생각하는지 성공회 신자로 생각하는지는 불분명합니다.[138] 역사적으로 성공회 36명, 장로회 19명, 유니테리언 10명, 감리교 5명, 침례교 3명 등 대부분의 재판관이 개신교 신자였습니다.[139][140] 최초의 가톨릭 재판관은 1836년 로저 테이니였고,[141] 1916년 최초의 유대인 재판관 루이 브란데이스가 임명되었습니다.[142] 최근 몇 년 동안 대부분의 재판관들이 가톨릭 신자이거나 유대인이었기 때문에 역사적 상황은 역전되었습니다.

3명의 재판관은 뉴욕주 출신이고, 2명은 워싱턴 D.C. 출신이며, 각각 1명은 뉴저지, 조지아, 콜로라도, 루이지애나 출신입니다.[143][144][145] 현직 대법관 중 8명이 아이비리그 로스쿨에서 법학박사 학위를 받았습니다. 하버드 출신의 닐 고서치, 케탄지 브라운 잭슨, 엘레나 케이건, 존 로버츠, 그리고 예일 출신의 사무엘 알리토, 브렛 캐버노, 소니아 소토마요르, 클래런스 토마스. 에이미 코니 배럿만이 그러지 않았습니다; 그녀는 노트르담에서 그녀의 법학박사를 받았습니다.

법원에 합류하기 전의 이전 직책 또는 사무소, 사법부 또는 연방 정부(대법원장에 이어 연공서열 순)는 다음과 같습니다.

| 정의 | 직책 또는 사무소 |

|---|---|

| 존 로버츠 | 미국 컬럼비아 특별구 순회 항소법원 판사 (2003-2005) |

| 클라렌스 토마스 | 고용기회균등위원회 위원장 (1982년 ~ 1990년) 미국 컬럼비아 특별구 순회 항소법원 판사 (1990-1991) |

| 사무엘 알리토 | 미국 뉴저지주 지방 검사 (1987년 ~ 1990년) 미국 제3순회항소법원 판사 (1990–2006) |

| 소니아 소토마요르 | 미국 뉴욕 남부지방법원 판사 (1992년 ~ 1998년) 미국 제2순회항소법원 판사 (1998-2009) |

| 엘레나 케이건 | 미국 법무장관 (2009년 ~ 2010년) |

| 닐 고서치 | 미국 제10순회항소법원 판사 (2006-2017) |

| 브렛 캐버노 | 미국 컬럼비아 특별구 순회 항소법원 판사 (2006-2018) |

| 에이미 코니 배럿 | 미국 제7순회항소법원 판사 (2017-2020) |

| 케탄지 브라운 잭슨 | 미국 양형위원회 부위원장 (2010~2014) 미국 컬럼비아 지방법원 판사 (2013-2021) 미국 컬럼비아 특별구 순회 항소법원 판사 (2021-2022) |

법원의 역사의 대부분 동안, 모든 재판관들은 북서유럽 혈통의 사람이었고, 거의 항상 개신교였습니다. 다양성에 대한 관심은 종교적, 민족적 또는 성별의 다양성보다는 국가의 모든 지역을 대표하는 지리학에 초점을 맞추었습니다.[146] 궁중의 인종적, 인종적, 성별적 다양성은 20세기 후반에 증가했습니다. Thurgood Marshall은 1967년 최초의 아프리카계 미국인 판사가 되었습니다.[142] 산드라 데이 오코너(Sandra Day O'Connor)는 1981년 최초의 여성 판사가 되었습니다.[142] 1986년, Antonin Scalia는 최초의 이탈리아계 미국인 판사가 되었습니다. 마셜은 1991년 아프리카계 미국인 Clarence Thomas의 뒤를 이었습니다.[147] O'Connor는 1993년 최초의 유대인 여성인 Ruth Bader Ginsburg와 함께 법정에 섰습니다.[148] O'Connor의 은퇴 이후 긴즈버그는 2009년 최초의 히스패닉 및 라틴계 판사인 Sonia Sotomayor와 [142]2010년 Elena Kagan에 의해 합류되었습니다.[148] 2020년 9월 18일 긴즈버그가 사망한 후 에이미 코니 배럿(Amy Coney Barrett)은 2020년 10월 26일 법원 역사상 다섯 번째 여성으로 확정되었습니다. 케탄지 브라운 잭슨(Ketanji Brown Jackson)은 법정에 선 여섯 번째 여성이자 첫 번째 아프리카계 미국인 여성입니다.

법원 역사상 여섯 명의 외국인 판사가 있었습니다: 스코틀랜드 캐스카디에서 태어난 제임스 윌슨 (1789–1798); 영국 루이스에서 태어난 제임스 이레델 (1790–1799); 아일랜드 앤트림 카운티에서 태어난 윌리엄 패터슨 (1793–1806); 오스만 제국(현재 ̇의 1889 즈미르) 스미르나에서 미국인 선교사 사이에서 태어난 데이비드 브루어 (1889–1910); 조지 서덜랜드(George Sutherland, 1922-1939)는 영국 버킹엄셔에서, 펠릭스 프랑크푸르터(Felix Frankfurter, 1939-1962)는 오스트리아-헝가리 빈(Vienna, 현재 오스트리아)에서 태어났습니다.[142]

1789년 이래로 약 3분의 1의 재판관이 미군 참전용사였습니다. Samuel Alito는 현재 코트에서 복무하고 있는 유일한 베테랑입니다.[149] 퇴역한 스티븐 브라이어와 앤서니 케네디 대법관도 미군에서 복무했습니다.[150]

사법적 성향

재판관들은 권력을 가진 대통령에 의해 지명되고, 상원에 의해 인준을 받는데, 역사적으로 지명된 대통령의 정당에 대한 많은 견해들을 가지고 있습니다. 입법부와 행정부에서 받아들여지는 것처럼, 재판관들은 정당들을 대표하거나 정당들로부터 공식적인 지지를 받지 않지만, 연방주의자 협회와 같은 조직들은 법에 대해 충분히 보수적인 견해를 가진 재판관들을 공식적으로 걸러내고 지지합니다. 법학자들은 종종 언론에서 비공식적으로 보수주의자나 진보주의자로 분류됩니다. 법학자들의 이념을 정량화하려는 시도로는 Segal-Cover 점수, Martin-Quinn 점수, Judical Common Space 점수 등이 있습니다.[151][152]

데빈스(Devins)와 바움(Baum)은 2010년 이전에는 법원이 정당 노선을 따라 완벽하게 떨어지는 명확한 이념적 블록을 가지고 있지 않았다고 주장합니다. 그들의 임명을 결정할 때, 대통령들은 종종 이념보다는 우정과 정치적 관계에 더 초점을 맞추었습니다. 공화당 대통령은 때로는 진보주의자를, 민주당 대통령은 때로는 보수주의자를 임명했습니다. 결과적으로, "... 1790년과 2010년 초 사이에 미국 대법원 가이드가 중요하다고 지정하고 대법관들이 정당 노선을 따라 최소한 2개의 반대표를 가진 두 개의 결정만이 있었는데, 이는 약 1%의 절반에 해당합니다."[153]: 316 [154] 격동의 1960년대와 1970년대에도 민주와 공화 엘리트들은 특히 시민권과 시민의 자유에 관한 몇 가지 주요 문제에 동의하는 경향이 있었고, 재판관들도 마찬가지였습니다. 그러나 1991년 이래로, 그들은 이념이 재판관들을 선출하는데 훨씬 더 중요했다고 주장합니다. 모든 공화당 지명자들은 보수주의자들이었고 모든 민주당 지명자들은 진보주의자들이었습니다.[153]: 331–344 중도 성향의 공화당 재판관들이 퇴임하면서 법원은 더욱 당파적으로 변했습니다. 공화당 대통령이 임명한 재판관들이 점점 보수적인 입장을 취하고 민주당이 임명한 재판관들이 온건한 진보적 입장을 취하면서 법원은 당파적 노선을 따라 더 첨예하게 분열되었습니다.[153]: 357

2020년 루스 베이더 긴즈버그의 사망으로 에이미 코니 배럿이 인준된 이후 법원에는 공화당 대통령이 임명하는 대법관이 6명, 민주당 대통령이 임명하는 대법관이 3명 있었습니다. 로버츠 대법원장과 공화당 대통령이 임명한 토머스·앨리토·고서치·캐버노·배럿 대법관이 법원의 보수파를, 민주당 대통령이 임명한 소토마요르·케이건·잭슨 대법관이 법원의 진보파를 구성하는 것이 일반적으로 받아들여지고 있습니다.[155] 2020년 긴즈버그 대법관이 사망하기 전에는 보수 성향의 로버츠 대법원장이 법원의 '중앙 대법관'(4명의 대법관이 진보적이고 4명의 대법관이 그보다 보수적)으로 묘사되기도 했습니다.[156][157] Darrag Roche는 2021년 중앙 재판관으로서 Cavanaugh가 법원의 우경화를 예시한다고 주장합니다.[158][needs update]

파이브서티에이트는 만장일치 판정 건수가 20년 평균인 50% 가까이에서 2021년 30% 가까이 감소한 반면, 당론 판결은 60년 평균인 0%를 약간 웃도는 21%[159]로 증가한 것으로 나타났습니다. 그 해 라이언 윌리엄스는 재판부가 상원에 당파적으로 중요하다는 증거로 대법관 인준을 위한 당론 투표를 지적했습니다.[160] 2022년 브루킹스의 사이먼 라자루스(Simon Lazarus)는 미국 대법원이 점점 더 당파적인 기관이라고 비판했습니다.[161]

퇴직법관

현재 살아있는 미국 연방 대법원의 퇴직 대법관은 세 명입니다. 앤서니 케네디, 데이비드 소터, 스티븐 브라이어. 퇴직한 대법관으로서, 그들은 더 이상 대법원의 업무에 참여하지 않지만, 하급 연방 법원, 일반적으로 미국 항소 법원에 앉기 위한 임시 임무를 위해 지정될 수 있습니다. 이와 같은 업무는 대법원장이 하급심 법원장의 요청과 퇴직한 대법관의 동의를 얻어 정식으로 수행합니다. 최근 몇 년 동안, 소터 대법관은 대법원에 합류하기 전에 잠시 소속되어 있던 제1순회법원에 자주 출석했습니다.[162] 퇴직한 법관의 지위는 고위직에 오른 순회법원이나 지방법원 판사의 지위와 유사하며, 퇴직한 법관의 지위는 (단순히 법관직에서 물러나는 것이 아니라) 동일한 연령과 복무 기준에 의해 결정됩니다.

최근에는 재판관들이 개인적, 제도적, 이념적, 당파적, 정치적 요인들이 역할을 하면서 재판부를 떠나겠다는 결정을 전략적으로 계획하는 경향이 있습니다.[163][164] 정신적 쇠퇴와 죽음에 대한 두려움은 종종 재판관들이 물러나게 하는 동기를 부여합니다. 법원이 휴회 중인 시기와 비대선 시기에 한 번의 퇴임을 통해 법원의 힘과 정당성을 극대화하려는 바람은 제도적 건전성에 대한 우려를 시사합니다. 마지막으로, 특히 최근 수십 년 동안, 많은 재판관들은 철학적으로 양립할 수 있는 대통령직을 수행하는 것과 동시에 같은 생각을 가진 후임자가 임명될 것을 보장하기 위해 그들의 퇴임 시기를 측정했습니다.[165][166]

| 정의 생년월일 및 장소 | 임명자 | 나이 : | 재직기간(현역) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 은퇴. | 현재의. | 시작일자 | 종료일 | 길이 | |||

| 앤서니 케네디 1936년7월23일 새크라멘토 | 레이건 (R) | 82 | 87 | 1988년2월18일 | 2018년7월31일 | 30년 163일 |

| 데이비드 소터 1939년9월17일 멜로즈 | G. H. W. 부시 (R) | 69 | 84 | 1990년10월9일 | 2009년6월29일 | 18세 263일 |

| 스티븐 브라이어 1938년 8월 15일 샌프란시스코 | 클린턴 (D) | 83 | 85 | 1994년8월3일 | 2022년6월30일 | 27세 331일 |

급여

2024년 현재, 대법관들은 298,500달러의 연봉을 받고 있고 대법원장은 312,200달러를 받고 있습니다.[167] 일단 판사가 나이와 복무 요건을 충족하면, 연방 직원들에게 사용되는 것과 같은 공식에 기초한 연금으로 은퇴할 수 있습니다. 다른 연방법원 판사들과 마찬가지로 이들의 연금은 헌법 제3조의 보상조항에 따라 퇴직 당시의 급여보다 결코 적을 수 없습니다.[citation needed]

연공서열 및 좌석

이 섹션은 확인을 위해 추가 인용이 필요합니다. "– (2019년 1월)(본 및 |

재판관들의 일상적인 활동은 대부분 재판관들의 연공서열에 따른 의전규칙에 의해 규율됩니다. 대법원장은 근무 기간에 관계없이 항상 우선 순위에서 1위를 차지합니다. 그런 다음 대법관은 복무 기간에 따라 순위가 매겨집니다. 대법원장은 벤치의 중앙에 앉거나 회의 중에 테이블 맨 앞에 앉습니다. 다른 재판관들은 연공서열 순으로 앉습니다. 가장 고위층인 대법관은 대법원장의 오른쪽에 바로 앉으며, 두 번째로 고위층은 바로 왼쪽에 앉습니다. 좌석은 연공서열 순으로 오른쪽에서 왼쪽으로 번갈아 가며 가장 후배 법관이 마지막 자리를 차지합니다. 따라서 2022년 10월 임기 이후 법원은 바렛, 고르수치, 소토마요르, 토마스(가장 고위 준법무관), 로버츠(대법원장), 알리토, 케이건, 캐버노, 잭슨 등 법원을 마주하고 있는 사람들의 관점에서 왼쪽에서 오른쪽으로 다음과 같이 앉습니다. 마찬가지로 법원 구성원들이 모여 공식 단체사진을 찍을 때 재판관들은 연공서열 순으로 배치되는데, 가장 선임된 5명의 재판관들은 법정 회기 중에 앉게 되는 것과 같은 순서로 맨 앞줄에 앉게 되고, 가장 선임된 4명의 재판관들은 그 뒤에 서게 되는데, 다시 법정 회의 때 앉았던 것과 같은 순서로 말입니다.

재판관들의 사적인 회의에서는 재판관들이 먼저 대법원장으로 시작해서 가장 후배인 대법관으로 끝나는 연공서열 순으로 발언하고 투표하는 것이 현재 관행입니다. 관례적으로, 이 회의들에서 가장 하급심 판사는 판사들이 단독으로 회의실 문에 응답하고, 음료를 제공하고, 법원의 명령을 서기에게 전달하는 등 필요한 모든 사소한 업무를 담당합니다.[168]

시설.

대법원은 1790년 2월 1일 뉴욕시의 상인거래소 건물에서 처음 만났습니다. 필라델피아가 수도가 되었을 때, 궁정은 독립기념관에서 잠시 만났고, 1791년부터 1800년까지 구시청에 정착했습니다. 정부가 워싱턴 D.C.로 이전한 후 법원은 1935년까지 국회의사당 건물의 다양한 공간을 점유했는데, 이때 법원은 자신의 목적에 맞게 지어진 집으로 이전했습니다. 4층짜리 이 건물은 카스 길버트가 의회 의사당과 의회 도서관의 주변 건물에 공감하는 고전적인 스타일로 디자인했으며 대리석으로 덮여 있습니다. 이 건물에는 법정, 대법관실, 광범위한 법률 도서관, 다양한 회의 공간 및 체육관을 포함한 부대 서비스가 포함됩니다. 대법원 건물은 의사당 건축가의 야심에 속하지만 의사당 경찰과는 별도로 자체 대법원 경찰을 유지하고 있습니다.[169]

원 퍼스트 스트리트 NE와 메릴랜드 애비뉴의 미국 국회의사당 1번가 건너편에 위치한 [170][171]이 건물은 평일 오전 9시부터 오후 4시 30분까지 일반인에게 개방되지만 주말과 공휴일에는 문을 닫습니다.[170] 방문객은 동행하지 않고 실제 법정을 둘러볼 수 없습니다. 카페테리아, 선물 가게, 전시품, 30분짜리 정보 필름이 있습니다.[169] 법정이 열리지 않을 때는 오전 9시 30분부터 오후 3시 30분까지 1시간 단위로 법정 관련 강의가 진행되며 예약은 필요 없습니다.[169] 법원이 개회 중일 때 대중은 10월부터 4월 하순까지 2주 간격으로 월, 화, 수요일에 매일 오전 2회(때로는 오후)에 걸쳐 12월과 2월에 휴식 시간을 갖고 구두 변론에 참석할 수 있습니다. 방문객들은 선착순으로 자리에 앉습니다. 한 가지 추정치는 약 250개의 좌석이 있습니다.[172] 개방 좌석의 수는 경우에 따라 다릅니다. 중요한 경우에는 일부 방문객이 전날 도착하여 밤을 지새우는 경우도 있습니다. 법원, 예정된 '논쟁의 날' 오전 10시부터 의견 공개(의견의 날이라고도 함)[173] 일반적으로 15분에서 30분 동안 진행되는 이 세션은 일반인에게도 공개됩니다.[173][169] 5월 중순부터 6월 말까지 매주 최소 1회씩 의견의 날이 예정되어 있습니다.[169] 대법원 경찰이 질문에 답할 수 있습니다.[170]

관할권.

| 헌법 미국의 |

|---|

|

| 개요 |

| 원칙 |

| 정부구조 |

| 개인의 권리 |

| 이론. |

연방 헌법 제3조에 의해 의회는 대법원의 상고 관할권을 규제할 권한이 있습니다. 대법원은 두 개 이상의[174] 주 사이의 사건에 대해 독창적이고 배타적인 관할권을 가지고 있지만 그러한 사건에 대한 심리를 거부할 수 있습니다.[175] 또한 "대사, 기타 공공장관, 영사 등이 수행하는 모든 행위 또는 절차"를 들을 수 있는 고유한 권한을 가지고 있지만 독점적인 권한은 가지고 있지 않으며, 또는 외국 국가의 부영사는 당사자입니다; 미국과 한 국가 사이의 모든 논쟁; 그리고 다른 국가의 시민들에 대한 또는 외국인에 대한 국가의 모든 행동 또는 절차."[176]

1906년에 법원은 미국에서 개인을 법정모독죄로 기소하는 원래의 관할권을 주장했습니다. 배.[177] 이로 인한 절차는 법원 역사상 유일한 모욕적 절차이자 유일한 형사재판으로 남아 있습니다.[178][179] 존 마샬 할런 대법관이 존슨의 변호사들이 항소를 제기할 수 있도록 형집행정지를 허가한 다음날 저녁 테네시주 채터누가에서 에드 존슨을 린치한 사건에서 모욕죄가 발생했습니다. 존슨은 린치 폭도들에 의해 감옥에서 쫓겨났고, 사실상 무방비 상태로 감옥을 떠난 지역 보안관의 도움을 받아 다리에서 교수형을 당했고, 그 후 한 부보안관이 존슨의 몸에 "할란 판사에게"라고 적힌 쪽지를 붙였습니다. 지금 와서 검둥이를 가져와요."[178] 지역 보안관 존 쉬프는 린치의 근거로 대법원의 개입을 꼽았습니다. 법원은 채터누가에서 열린 재판을 주재할 특별 마스터로 대리 서기를 임명했으며, 9명의 사람들이 모욕죄를 인정해 징역 3~90일을 선고하고 나머지는 징역 60일을 선고했습니다.[178][179][180]

다른 모든 경우에 법원은 만다무스의 서면과 금지 서면을 하급 법원에 발행할 수 있는 권한을 포함하여 항소 관할권만 가지고 있습니다. 원래 관할권에 근거한 사건을 매우 드물게 고려하는데, 거의 모든 사건이 상고심으로 대법원에 회부됩니다. 실무적으로 법원이 심리하는 원 관할 사건은 두 개 이상의 주 사이의 분쟁뿐입니다.[181]

법원의 항소 관할권은 연방 항소 법원(certiorari, 판결 전 certiorari, certiorari, certiorari를 통한 질문),[182] 미국 국군 항소 법원([183]certiorari를 통한), 푸에르토리코 대법원([184]certiorari를 통한), 버진 아일랜드 대법원(certiorari를 통해),[185] 컬럼비아 지방 항소 법원(certiorari를 통해),[186] "결정을 내릴 수 있는 국가의 최고 법원이 내린 최종 판결 또는 법령"(certiorari를 통해).[186] 마지막으로 주 최고 법원이 항소를 거부하거나 항소를 심리할 관할권이 없는 경우 하급 주 법원에서 대법원에 항소할 수 있습니다. 예를 들어, 플로리다 지방 항소 법원 중 하나가 내린 결정은 (a) 플로리다 대법원이 certiorari를 승인하지 않은 경우 미국 대법원에 항소할 수 있습니다. 예를 들어, Florida Star v. B. J. F., 또는 (b) 지방 항소법원은 플로리다주 대법원이 그러한 결정의 항소를 심리할 수 있는 관할권이 없기 때문에 사건의 본안에 대한 논의 없이 단순히 원심의 결정을 긍정하는 페리엄 결정을 내린 것입니다.[187] 연방 법원만이 아닌 주 법원의 항소를 고려할 수 있는 대법원의 권한은 1789년 사법법에 의해 만들어졌고 마틴 대 법원의 판결에 의해 법원 역사의 초기에 유지되었습니다. 헌터 레시(1816)와 코헨스 대 버지니아(1821). 주 사건에 대한 이른바 '담보 검토'를 허용하는 장치가 여러 개 있지만 주 법원 결정에 따른 직접 항소를 관할하는 연방 법원은 연방 대법원이 유일합니다. 이러한 "담보 검토"는 종종 사형수에 있는 개인에게만 적용되며 정규 사법 시스템을 통해서는 적용되지 않는다는 점에 유의해야 합니다.[188]

미국 헌법 제3조는 연방 법원이 "사건" 또는 "논쟁"만을 접대할 수 있다고 규정하고 있기 때문에, 대법원은 일부 주의 대법원이 할 수 있는 것처럼 무뚝뚝한 사건을 결정할 수 없고 자문 의견을 제시하지 않습니다. 예를 들어 DeFunis v에서. Odegaard(1974), 법원은 원고 학생이 소송을 시작한 이후 졸업을 했고, 그의 청구에 대한 법원의 결정이 그가 입은 어떠한 부상도 보상할 수 없다는 이유로 로스쿨 긍정적 조치 정책의 합헌성에 이의를 제기하는 소송을 기각했습니다. 다만 법원은 겉으로 보기에 무뚝뚝한 사건을 심리하는 것이 적절한 사정을 인정하고 있습니다. 문제가 "반복할 수 있으면서도 검토를 피할 수 있는" 문제라면, 법원 앞의 당사자가 유리한 결과에 의해 전체적으로 만들어지지 않더라도 법원은 이 문제를 해결할 것입니다. 로 대 웨이드(Roe v. Wade, 1973) 및 기타 낙태 사건에서 법원은 하급 법원을 통해 대법원에 사건을 항소하는 데 일반적인 인간 임신 기간보다 더 오래 걸리기 때문에 더 이상 임신하지 않더라도 낙태를 원하는 임산부가 압박하는 주장의 장점을 다룹니다. 또 다른 무뚝뚝한 예외는 법원이 재발 가능성과 원고의 구제 필요성을 고려하는 자발적인 불법 행위 중단입니다.[189]

순회재판관으로서의 재판관들

미국은 13개의 순회 항소 법원으로 나뉘는데, 이 법원들은 각각 대법원으로부터 "순회 재판"을 받습니다. 비록 이 개념은 공화국의 역사를 통틀어 지속적으로 존재해 왔지만, 시간이 지나면서 그 의미가 변했습니다. 1789년 사법법에 따라 각 판사는 "순회로"를 타거나 지정된 회로 내에서 이동하고 지역 판사와 함께 사건을 고려해야 했습니다. 이 관행은 여행의 어려움을 언급한 많은 재판관들의 반대에 부딪혔습니다. 게다가 이전에 판사가 서킷을 타면서 같은 사건을 결정했다면 법원에서 이해관계가 충돌할 가능성이 있었습니다. 서킷 라이딩은 1901년 서킷 항소 법원법이 통과되면서 종료되었고, 1911년 의회에 의해 서킷 라이딩은 공식적으로 폐지되었습니다.[190]

각 회로에 대한 순회 재판관은 법률과 법원의 규칙에 따라 단일 재판관이 처리할 수 있는 특정 유형의 신청을 처리할 책임이 있습니다. 일반적으로 판사는 이러한 신청을 단순히 승인하거나 "승인" 또는 "거부"하거나 표준 형태의 질서를 입력함으로써 해결합니다. 그러나 판사는 의견서를 작성하기로 선택할 수 있습니다. 의회는 특히 한 명의 대법관에게 28 .§ 2101(f)에서 보류 중인 증명서를 발급할 수 있는 권한을 부여했습니다. 각 재판관은 또한 시간 연장과 같은 일상적인 절차적 요청을 결정합니다.

1990년 이전에 대법원의 규칙은 "법원이 허가할 수 있는 경우에는 누구든지 금지명령장을 허가할 수 있다"고 명시하기도 했습니다.[191] 그러나 1989년 12월 대법원 규칙 개정에서 이 부분(및 기타 금지명령에 대한 모든 구체적인 언급)이 삭제되었습니다.[192][193] 그럼에도 불구하고 전원합의체법상 금지명령 청구는 순회재판부로 향하기도 합니다. 과거에,[when?] 순회 재판관들은 또한 때때로 형사 사건에서 보석을 위한 동의, 인신 보호 영장, 그리고 항소를 허가하는 오류 영장 신청을 허가했습니다.[194]

순회 판사는 그 순회 항소 법원의 판사로 앉아있을 수 있지만, 지난 100년 동안 이런 일은 거의 일어나지 않았습니다. 항소법원에 소속된 순회판사는 순회판사보다 연공서열을 가지고 있습니다.[195] 대법원장은 전통적으로 컬럼비아 특별구 순회구, 제4 순회구(컬럼비아 특별구를 둘러싸고 있는 메릴랜드와 버지니아를 포함하는 주), 연방 순회구에 배정되었습니다. 각 준사법은 하나 또는 두 개의 사법 회로에 할당됩니다.

2022년 9월 28일 현재 서킷 중 재판관 배정은 다음과 같습니다.[196]

| 서킷 | 정의 |

|---|---|

| 컬럼비아 특별구 서킷 | 대법원장 로버츠 |

| 첫 번째 회로 | 저스티스 잭슨 |

| 제2회로 | 소토 시장 대법관 |

| 서드 서킷 | 알리토 대법관 |

| 제4회로 | 대법원장 로버츠 |

| 제5 서킷 | 알리토 대법관 |

| 제6 서킷 | 캐버노 대법관 |

| 제7 서킷 | 저스티스 바렛 |

| 제8 서킷 | 캐버노 대법관 |

| 제9서킷 | 케이건 대법관 |

| 제10서킷 | 고서치 대법관 |

| 11번 서킷 | 토머스 판사 |

| 연방 서킷 | 대법원장 로버츠 |

현재 재판관 중 5명은 이전에 순회 재판관으로 앉았던 순회 재판에 배정됩니다. 로버츠 대법원장(D.C. 순회), 소토마이어 대법관(제2 순회), 알리토 대법관(제3 순회), 바렛 대법관(제7 순회), 고서치 대법관(제10 순회).

과정

사례선정

거의 모든 사건은 법원에 일반적으로 cert라고 불리는 certiorari의 영장에 대한 청원을 통해 법원에 제출되며, 법원은 이에 대해 certiorari의 영장을 승인합니다. 법원은 이 과정을 통해 연방 항소 법원에서 민사 또는 형사 사건을 검토할 수 있습니다.[197] 또한 판결이 연방 법률 또는 헌법 법률의 문제와 관련된 경우 한 주의 최고 법원의 최종 판결을 증명서에 의해 검토할 수 있습니다.[198] 3명의 판사로 구성된 연방 지방 법원의 직접 항소로 법원에 소송이 제기될 수도 있습니다.[199] 법원에 심사를 청구하는 당사자는 청구인이고 미이송인은 피청구인입니다.

심법원에서 소송을 개시한 당사자가 누구인지를 불문하고 법원 전 사건명은 피청구인 대 피청구인으로 양식화되어 있습니다. 예를 들어, 형사 기소는 애리조나 주 대 어네스토 미란다에서처럼 국가의 이름으로 그리고 개인에 대해 제기됩니다. 피고인이 유죄 판결을 받고 주 대법원에서 상고심에서 유죄 판결을 받으면 사건의 이름을 확인해 달라고 청원할 때 미란다 대 애리조나가 됩니다.

법원은 또한 인증이라고 알려진 절차를 통해 항소 법원이 직접 제출한 질문을 듣습니다.[197]

대법원은 하급심이 수집한 기록을 사건의 사실관계에 의존하여 법이 제시된 사실관계에 어떻게 적용되는지에 대한 문제만을 다루고 있습니다. 그러나 두 주 사이에 서로 분쟁이 있을 때나 미국과 주 사이에 분쟁이 있을 때와 같이 법원이 원래의 관할권을 가지고 있는 상황이 있습니다. 이런 경우에는 대법원에 직접 소송을 제기합니다. 그러한 경우의 예로는 미국 v가 있습니다. 텍사스, 토지의 일부가 미국에 속하는지, 텍사스에 속하는지, 버지니아 대. 테네시주, 주 법원에 의해 잘못 그려진 두 주 사이의 경계를 변경할 수 있는지 여부와 정확한 경계 설정에 의회의 승인이 필요한지 여부에 관한 판례. 비록 1794년 조지아 대 브레일스포드 사건 이후로 그런 일은 일어나지 않았지만,[200] 대법원이 원래 관할권을 가지고 있는 법률 소송의 당사자들은 배심원들에게 사실의 문제를 결정하도록 요청할 수 있습니다.[201] 조지아 대 브레일스포드 사건은 법원이 배심원을 특별배심원으로 지정한 유일한 사건으로 남아 있습니다.[202] 다른 두 개의 원래 관할권 사건에는 식민지 시대 국경과 뉴저지 대 델라웨어의 항해 가능한 해역에 대한 권리, 캔자스 대 콜로라도의 항해 가능한 해역 상류에 있는 강가 주 간의 수권이 포함됩니다.

청원서는 회의라고 불리는 법정의 회의에서 표결됩니다. 회의는 9명의 재판관이 단독으로 회의를 하는 것으로 일반인과 재판관 사무원은 제외됩니다. 4인의 규칙은 재판관 9명 중 4명이 영장을 허가할 수 있도록 하고 있습니다. 허가가 되면 사건은 브리핑 단계로 진행되고, 허가가 나지 않으면 사건은 종료됩니다. 법원이 피청구인에게 브리핑을 명하는 사형사건 및 그 밖의 경우를 제외하고, 피청구인은 증명서에 대한 답변을 제출할 수 있지만, 제출할 필요는 없습니다. 법원은 법원 규칙 10에 명시된 "강박한 이유"에 대해서만 확인 청원을 허가합니다. 이러한 이유는 다음과 같습니다.

- 연방법 또는 연방헌법 조항의 해석상 순회법원 간의 충돌 해결

- 받아들여지고 통상적인 사법 절차 과정에서 발생하는 말도 안 되는 이탈 시정

- 연방법의 중요한 문제를 해결하거나 법원의 이전 결정과 직접 충돌하는 하급 법원의 결정을 명시적으로 검토하는 것.

서로 다른 연방 순회 항소 법원이 발표한 동일한 법률 또는 헌법 조항에 대한 서로 다른 해석에서 해석의 충돌이 발생할 때, 변호사들은 이 상황을 "순회 분열"이라고 부릅니다. 법원이 특정 청원을 거부하는 투표를 하는 경우, 그 청원에 앞서 오는 대부분의 청원에서와 마찬가지로, 일반적으로 코멘트 없이 그렇게 합니다. 어떤 진정에 대한 부정은 사건의 본안에 대한 판단이 아니고, 원심의 결정이 사건의 확정판결로 서 있습니다. 법원은 매년 접수되는 많은 양의 청원(매년 접수되는 7,000건 이상의 청원 중 보통 100건 이하로 브리핑을 요청하고 구두변론을 듣는 것)을 관리하기 위해 내부사건관리도구인 'cert pool'을 사용하고 있으며, 현재는 알리토 대법관과 고르수치 대법관을 제외한 모든 대법관들이 cert pool에 참여합니다.[203][204][205][206]

구두변론

법원이 특정 청원을 하면 구두변론으로 사건이 정해집니다. 양 당사자는 이 사건의 본안에 대한 브리핑을 제출할 것이며, 이는 그들이 증명서를 승인하거나 거부하는 것을 주장했을 수 있는 이유와 구별됩니다. 당사자의 동의 또는 법원의 승인을 얻어 아미퀴리아 또는 "법원의 친구"도 브리핑을 제출할 수 있습니다. 법원은 10월부터 4월까지 매달 2주간 구두변론을 진행합니다. 각 측은 30분씩 변론을 할 시간을 갖는데(법원은 이 경우는 드물지만 시간을 더 주기로 선택할 수 있습니다),[207] 그 시간 동안 재판관들은 변호인을 방해하고 질문을 할 수 있습니다. 2019년 법원은 일반적으로 옹호자들이 논쟁의 처음 2분 동안 중단 없이 말할 수 있도록 허용하는 규칙을 채택했습니다.[208] 청원인은 첫 번째 발표를 하고, 피신청인이 결론을 내린 후에 피신청인의 주장을 반박할 시간을 가질 수 있습니다. 당사자가 동의하는 경우 아미큐리아는 당사자를 대신하여 구두 변론을 제시할 수도 있습니다. 법원은 변호인들에게 재판관들이 사건에 제출된 브리핑을 잘 알고 있고 읽었다고 가정하라고 조언합니다.

결정

구두변론이 끝나면 사건은 결정을 위해 제출됩니다. 사건은 재판관들의 다수결로 결정됩니다. 구두변론이 종결된 후, 보통 사건이 제출된 같은 주에, 재판관들은 예비투표가 집계되고 법원이 어느 쪽이 승소했는지를 보는 다른 회의로 은퇴합니다. 그런 다음 다수의 재판관 중 한 명이 법원의 의견서를 작성하도록 할당되는데, 이는 다수의 가장 고위직 재판관이 수행하는 임무로, 항상 대법원장이 가장 고위직으로 간주됩니다. 법원의 의견서 초안은 법원이 특정 사건에 대한 판결을 발표할 준비가 될 때까지 재판관들 사이에서 회람됩니다.[209]

재판관들은 결정이 확정되고 발표될 때까지 사건에 대해 자유롭게 표를 바꿀 수 있습니다. 어떤 경우든, 법관은 자유롭게 의견을 작성할 것인지 아니면 단순히 다수 의견이나 다른 법관의 의견에 참여할 것인지를 선택할 수 있습니다. 다음과 같은 몇 가지 주요 유형의 의견이 있습니다.

- 법원의 의견 : 대법원의 구속력 있는 결정입니다. 재판관의 절반 이상이 참여하는 의견(보통 총 9명의 재판관이 있기 때문에 최소 5명의 재판관이 참여하지만 일부 재판관이 참여하지 않는 경우에는 더 적을 수 있음)은 "다수 의견"으로 알려져 미국 법에서 구속력 있는 선례를 만듭니다. 재판관 절반 이하가 합헌한다는 의견은 '복수의견'으로 알려져 부분적 구속력이 있는 판례에 불과합니다.

- 동의: 재판관은 다수 의견에 동의하고 합류하지만 추가 설명, 합리성 또는 논평을 제공하기 위해 별도의 동의를 작성합니다. 일치는 구속력 있는 선례를 만들지 않습니다.

- 판결의 일치: 재판관은 법원이 도달한 결과에는 동의하지만 그렇게 한 이유에는 동의하지 않습니다. 이러한 상황에서 정의는 다수 의견에 합류하지 않습니다. 일반적인 동의와 마찬가지로 구속력 있는 선례를 만들지 않습니다.

- 반대: 재판관은 법원이 도달한 결과와 그 추론에 동의하지 않습니다. 어떤 결정에 반대하는 재판관들은 그들 자신의 반대 의견을 작성할 수도 있고, 어떤 결정에 반대하는 재판관들이 여러 명일 경우, 다른 재판관의 반대 의견에 합류할 수도 있습니다. 반대 의견은 구속력 있는 선례를 만들지 않습니다. 재판관은 또한 특정 결정의 일부(들)에만 참여할 수 있으며, 심지어 결과의 일부에 동의하고 다른 일부에 동의하지 않을 수도 있습니다.

그 기간이 끝날 때까지 특정 기간에 주장된 모든 사건에서 결정을 내리는 것이 법원의 관행입니다. 그 기간 내에 법원은 구두 변론 후 정해진 시간 내에 결정을 발표할 의무가 없습니다. 대법원 청사 법정 안에서는 녹음 장치가 금지돼 있기 때문에 언론에 결정문 전달은 이른바 '인턴들의 질주'로 알려진 종이 사본을 통해 이뤄졌습니다.[210] 그러나 법원이 현재 웹사이트에 의견이 발표되고 있는 대로 전자 사본을 게시함에 따라 이러한 관행은 수동적이 되었습니다.[211]

법원은 기각 또는 공석을 통해 사건에 대해 균등하게 분할할 수 있습니다. 그렇게 되면 원심의 판단은 긍정되지만 구속력 있는 판례가 성립하지 않습니다. 사실상, 그것은 현상 유지로 귀결됩니다. 사건이 심리되려면 재판관 6명 이상의 정족수가 있어야 합니다.[212] 정족수로 사건을 심리할 수 없고, 적격 재판관 과반수가 다음 임기에 사건을 심리·결정할 수 없다고 판단한 경우, 마치 재판부가 균등하게 분할된 것처럼 원심의 판단을 긍정합니다. 미국 지방 법원의 직접 항소에 의해 대법원에 제기된 사건의 경우, 대법원장은 해당 사건을 해당 미국 항소 법원에 환송하여 최종 판결을 내릴 것을 명령할 수 있습니다.[213] 이는 미국 역사상 단 한 번, 미국 v의 경우에 발생한 적이 있습니다. 알코아 (1945).[214]

공표된 의견

이 섹션을 업데이트해야 합니다. (2021년 8월) |

법원의 의견은 3단계로 나누어 발표됩니다. 먼저 법원의 웹사이트와 다른 아웃렛을 통해 전표 의견을 확인할 수 있습니다. 다음으로 법원의 여러 의견과 명령 목록이 페이퍼백 형식으로 묶여 있는데, 이는 법원의 의견 최종판이 등장하는 공식 시리즈인 United States Reports의 예비 인쇄물이라고 불립니다. 예비 인쇄물이 발행되고 약 1년 후, 결정 기자에 의해 최종 제본된 U.S. Reports가 발행됩니다. U.S. Reports의 개별 볼륨은 사용자가 이 보고서 세트(또는 다른 상업 법률 출판사에서 발행하지만 병렬 인용을 포함하는 경쟁 버전)를 인용하여 변론 및 기타 개요를 읽은 사람이 사건을 빠르고 쉽게 찾을 수 있도록 번호가 매겨집니다. 2019년[update] 1월 기준으로 다음이 있습니다.

- 미국 보고서의 최종 바인딩 볼륨: 569권, 2013년 6월 13일까지의 사례(2012년 10월 임기의 일부).[215][216]

- 전표의견: 21권(2011~2017기 565~585, 2부 각 3권), 586권(2018기)[217] 1부.

2012년[update] 3월 현재, U.S. Reports는 1790년 2월부터 2012년 3월까지 내려진 판결을 총 30,161건의 대법원 의견을 발표했습니다.[citation needed] 이 수치는 여러 사건이 단일 의견으로 해결될 수 있기 때문에 법원이 차지한 사건의 수를 반영하지 않습니다(예를 들어, 부모 대 시애틀 참조). 여기서 메러디스 대 제퍼슨 카운티 교육위원회도 같은 의견으로 결정되었고, 유사한 논리인 미란다 대. 애리조나는 실제로 미란다 뿐만 아니라 다른 세 가지 경우도 결정했습니다. Vignera v. New York, Westover v. United States, California v. Stewart). 더 특이한 예는 The Telephone Case인데, 이들은 U.S. Reports 126권 전체를 차지하는 단일 연결된 의견 집합입니다.

또한 의견들은 두 개의 비공식 병행 기자들을 통해 수집되고 발표됩니다: West(현재 Thomson Reuters의 일부)가 발행하는 Supreme Court Reporter와 Lexis Nexis가 발행하는 U.S. President Reports, Lawilers' Edition(단순히 변호사 에디션이라고도 함). 법원 문서, 법률 정기 간행물 및 기타 법률 매체에서 사례 인용에는 일반적으로 세 기자 각각의 인용이 포함됩니다. 예를 들어 시티즌 유나이티드 v에 대한 인용. 연방 선거 위원회는 시민 연합 대로 제시됩니다. 연방 선거 Com'n, 585 U.S. 50, 130 S. Ct. 876, 175 L. Ed. 2d 753 (2010), "S. Ct."는 대법원 기자를, "L. Ed."는 변호사판을 대표합니다.[218][219]

공표된 의견에 대한 인용

변호사들은 사건을 인용하기 위해 축약된 형식을 사용합니다. "vol 미국의page, pin (year)", 여기서vol 볼륨 번호입니다.page 의견이 시작되는 페이지 번호입니다.year 사건이 결정된 해입니다. 선택적으로,pin 의견 내의 특정 페이지 번호로 "pinpoint"하는 데 사용됩니다. 예를 들어, Roe v. Wade에 대한 인용은 410 U.S. 113 (1973)인데, 이것은 이 사건이 1973년에 결정되었다는 것을 의미하며 U.S. Reports 410권의 113페이지에 나타납니다. 아직 예비인쇄물에 게재되지 않은 의견 또는 주문에 대해서는 볼륨 및 페이지 번호를 ___로 대체할 수 있습니다.

대법원바

법원 앞에서 변론을 하려면 변호사가 먼저 법원의 변호사 변호사를 선임해야 합니다. 매년 약 4,000명의 변호사가 바에 가입합니다. 바에는 약 23만 명의 회원이 있습니다. 현실적으로 변론은 수백 명의 변호사로 제한되어 있습니다.[citation needed] 나머지는 200달러의 일회성 비용으로 가입하며, 법원은 연간 약 75만 달러를 징수합니다. 변호사는 개인 또는 그룹으로 인정될 수 있습니다. 단체 입회는 대법원장이 신임 변호사 입회 동의안을 승인하는 현직 대법관들 앞에서 열립니다.[220] 변호사는 일반적으로 사무실이나 이력서에 표시할 증명서의 미용적 가치를 신청합니다. 또한 구두 토론에 참석하려면 더 나은 좌석을 이용할 수 있습니다.[221] 대법원 변호사 회원에게는 대법원 도서관의 소장품을 열람할 수 있는 권한도 부여됩니다.[222]

용어

대법원의 임기는 매년 10월 첫째 주 월요일에 시작하여 다음 해 6월 또는 7월 초까지 계속됩니다. 각 용어는 "좌담회"와 "휴회"로 알려진 약 2주의 교대 기간으로 구성됩니다. 재판관들은 좌담회 중에 사건을 듣고 판결을 전달하며, 휴회 중에 사건을 논의하고 의견을 작성합니다.[223]

제도권

연방 법원 제도와 헌법 해석을 위한 사법권은 헌법의 초안과 비준을 둘러싼 논쟁에서 거의 주목을 받지 못했습니다. 사실 사법심사의 힘은 그 어디에도 언급되어 있지 않습니다. 그 후 몇 년 동안 사법심사의 권한이 헌법 초안 작성자들이 의도한 것인지에 대한 질문은 어느 쪽이든 그 질문과 관련된 증거가 부족하여 순식간에 좌절되었습니다.[224] 그럼에도 사법부가 위법·위헌이라고 판단한 법률과 행정행위를 뒤집을 수 있는 권한은 충분히 확립된 판례입니다. 많은 건국의 아버지들은 사법 심사의 개념을 받아들였습니다; 연방주의자 78호에서, 알렉산더 해밀턴은 "헌법은 사실 기본적인 법으로서 판사들에 의해 간주되어야 합니다. 따라서 그 의미와 입법 기관에서 진행되는 특정 행위의 의미를 확인하는 것은 그들에게 속합니다. 만약 둘 사이에 화해할 수 없는 차이가 있다면, 당연히 우월한 의무와 타당성을 가진 것이 선호되어야 합니다; 즉, 헌법이 법령보다 선호되어야 합니다."

연방대법원은 마버리 대 매디슨(1803)에서 미국의 견제와 균형의 체계를 소모하는 법률에 대해 위헌을 선언할 수 있는 강력한 권한을 확고히 확립했습니다. 존 마셜 대법원장은 사법심사의 권한을 설명하면서 법을 해석하는 권한은 법원의 특정 지방이며, 법이 무엇인지 말하는 사법부의 의무의 일부라고 말했습니다. 그의 주장은 법원이 헌법 요건에 대한 특권적인 통찰력을 가지고 있다는 것이 아니라 헌법의 명령을 읽고 따르는 것이 사법부와 정부의 다른 부문의 헌법적 의무라는 것이었습니다.[224]

공화국 건국 이후 사법심사 실무와 평등주의, 자치, 자결권, 양심의 자유라는 민주적 이상 사이에 긴장관계가 형성되어 왔습니다. 연방 사법부와 특히 대법원을 "정부의 모든 부문 중 가장 분리되고 가장 덜 견제받는" 것으로 보는 사람들이 한 극에 있습니다.[225] 실제로 대법원의 연방 판사와 대법관은 "선의의 행위 중"에 임기 때문에 선거에 출마할 필요가 없으며, 직위를 유지하는 동안 급여가 "감소되지 않을" 수 있습니다(제3조 제1항). 탄핵 절차를 밟았지만 단 한 명의 대법관만 탄핵된 적이 있고, 대법관이 해임된 적은 없습니다. 다른 극에는 사법부를 가장 위험하지 않은 부서로 보는 사람들이 있는데, 정부의 다른 부서의 권고를 거부할 능력은 거의 없습니다.[224]

제약

대법원은 판결을 직접 집행할 수 없고, 대신 헌법과 법률에 대한 존중에 의존하여 판결을 준수합니다. 1832년 조지아주가 우스터 대 조지아주 대법원의 판결을 무시한 것은 주목할 만한 불인정 사례 중 하나입니다. 조지아 법원의 편에 섰던 앤드류 잭슨 대통령은 "존 마샬이 결정을 내렸으니 이제 그가 그것을 시행하게 해주세요!"[226]라고 말한 것으로 알려졌습니다. 남부의 일부 주 정부들도 1954년 브라운 대 교육위원회 판결 이후 공립학교의 차별 철폐에 저항했습니다. 더 최근에는 닉슨 대통령이 미국 대 닉슨 (1974년) 워터게이트 테이프를 포기하라는 법원의 명령에 따르지 않을 것이라고 우려했습니다.[227] 닉슨은 결국 대법원의 판결에 순응했습니다.[228]

대법원 결정은 개헌에 의해 의도적으로 뒤집힐 수 있는데, 이는 여섯 차례에 걸쳐 일어난 일입니다.[citation needed]

- 치홀름 대 조지아 (1793) – 수정헌법 11조 (1795)에 의해 뒤집힘

- Deld Scott v. Sandford (1857) – 수정헌법 13조 (1865)와 수정헌법 14조 (1868)에 의해 뒤집힘

- Pollock v. Farmers' Loan & Trust Co. (1895) – 수정헌법 16조 (1913)에 의해 뒤집힘

- 마이너 대 해퍼셋 (1875) – 수정헌법 19조 (1920)에 의해 뒤집힘

- Bridlove v. Suttles (1937) – 수정헌법 제24조 (1964)에 의해 뒤집힘

- 오리건 대 미첼 (1970) – 수정헌법 26조 (1971)에 의해 뒤집힘

법원이 헌법이 아닌 법률 해석과 관련된 문제에 대해 판결을 내릴 때, 간단한 입법 조치는 결정을 뒤집을 수 있습니다(예를 들어, 2009년 의회는 2009년 Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act of 2009를 통과시켰고, 2007년 Ledbetter v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co.에 주어진 제한을 대체했습니다). 또한 대법원은 정치적, 제도적 고려로부터 자유롭지 못합니다: 하급 연방 법원과 주 법원은 때때로 법 집행 관리와 마찬가지로 교리적 혁신에 저항합니다.[229]

또한 다른 두 지부는 다른 메커니즘을 통해 법원을 구속할 수 있습니다. 의회는 재판관의 수를 늘려 대통령이 임명에 의해 향후 결정에 영향을 미칠 수 있는 권한을 부여할 수 있습니다(위에서 설명한 Roosevelt의 Court Packing Plan에서와 같이). 의회는 특정 주제와 사건에 대해 대법원과 다른 연방 법원의 관할권을 제한하는 법안을 통과시킬 수 있습니다. 이것은 항소 관할권이 "예외와 의회가 만들어야 하는 규정에 따라" 부여되는 제3조의 2절에서 언어로 제안됩니다. 법원은 미국 대 클라인 사건(1871)에서 특정 사건이 어떻게 결정되어야 하는지를 지시하는 의회의 권한을 거부했지만, 재건 시대 사건(1869)에서 이러한 의회의 조치를 승인했습니다.[citation needed]

한편 [tone]대법원은 사법심사권을 통해 연방정부의 입법부와 행정부 간 권한과 분리의 범위와 성격을 규정하고 있는데, 예를 들어 미국 대 커티스-라이트 수출회사(1936), 데임스 & 무어 대 리건(1981), 특히 골드워터 대. 의회의 동의 없이 비준된 조약을 종료할 수 있는 권한을 사실상 대통령에게 부여한 카터(1979). Humphrey's Executor v. United States(1935), Steel Assurance Case(1952), United States v. Nixon(1974)과 같이 법원의 결정은 집행권원의 범위에도 제한을 가할 수 있습니다.[citation needed]

법률사무소원

각 대법관은 여러 명의 법률 사무원을 고용하여 인증장 영장 청구서를 검토하고, 이를 조사하며, 각서를 작성하고, 의견 초안을 작성합니다. 대법관은 4명의 사무원을 허용합니다. 대법원장은 5명의 사무원을 고용할 수 있지만 렌퀴스트 대법원장은 1년에 3명만 고용하고 로버츠 대법원장은 보통 4명만 고용합니다.[230] 일반적으로 법률 사무원의 임기는 1년에서 2년입니다.

최초의 법률 사무원은 1882년 호레이스 그레이 대법관에 의해 고용되었습니다.[230][231] 올리버 웬델 홈즈 주니어와 루이스 브랜다이스는 최근 로스쿨 졸업생을 속기사로 고용하는 대신 사무원으로 사용한 최초의 대법관이었습니다.[232] 대부분의 법률 사무원들은 최근 법학전문대학원을 졸업한 사람들입니다.

최초의 여성 점원은 1944년 윌리엄 오 판사에 의해 고용된 루실 로멘이었습니다. 더글러스.[230] 최초의 아프리카계 미국인, 윌리엄 T. 콜먼 주니어는 1948년 펠릭스 프랑크푸르터 판사에 의해 고용되었습니다.[230] 불균형적으로 많은 수의 법률 사무원들이 엘리트 로스쿨, 특히 하버드, 예일, 시카고 대학, 컬럼비아 및 스탠포드에서 법학 학위를 취득했습니다. 1882년부터 1940년까지 법률 사무원의 62%가 하버드 로스쿨을 졸업했습니다.[230] 대법원의 법률 사무원이 되기 위해 선택된 사람들은 보통 로스쿨 수업에서 수석으로 졸업했고, 종종 법학 리뷰의 편집자나 무트 법원 위원회의 일원이었습니다. 1970년대 중반까지 연방 항소 법원에서 판사로 일하던 성직자도 대법원 판사로 일하던 성직자의 필수 조건이 되었습니다.

10명의 대법관들은 이전에 다른 대법관들을 위해 서기를 맡았습니다. 프레드릭 M을 위한 바이런 화이트. 빈슨, 와일리 러틀리지의 존 폴 스티븐스, 로버트 H. 잭슨의 윌리엄 렌퀴스트, 아서 골드버그의 스티븐 브라이어, 윌리엄 렌퀴스트의 존 로버츠, 서굿 마샬의 엘레나 케이건, 바이런 화이트와 앤서니 케네디의 닐 고서치, 케네디의 브렛 캐버노, 안토닌 스칼라의 에이미 코니 배럿, 그리고 스티븐 브라이어를 위해 케탄지 브라운 잭슨. 고서치 대법관과 캐버노 대법관은 같은 기간 케네디 밑에서 재임했습니다. 고르수치는 2017년 4월부터 2018년 케네디 퇴임까지 케네디와 함께 근무한 최초의 대법관입니다. 캐버노 대법관의 인준으로 처음으로 대법관의 과반수가 전직 대법관 사무원(로버트, 브라이어, 케이건, 고서치, 캐버노, 현재 배럿과 잭슨이 합류)으로 구성됐습니다.

몇몇 현직 대법관들도 연방 항소 법원에 서기를 맡았습니다: 미국 제2순회 항소 법원의 헨리 프렌들리 판사를 위한 존 로버츠, 레너드 1세 판사를 위한 새뮤얼 알리토 판사입니다. 미국 제3순회 항소법원 가스, 미국 컬럼비아 특별구 항소법원 애브너 J. 미카바 판사 엘레나 케이건, 닐 고서치 판사 데이비드 B. 미국 컬럼비아 특별구 항소법원의 센텔, 미국 제3 순회 항소법원의 월터 스테이플턴 판사와 미국 제9 순회 항소법원의 알렉스 코진스키 판사, 미국 로렌스 실버먼 판사의 에이미 코니 바렛. DC 항소법원 서킷.

법원의 정치화

대법관 각자가 고용한 사무원들은 자신들이 입안한 의견에 상당한 자유를 부여받는 경우가 많습니다. 2009년 밴더빌트대 로스쿨의 법학 리뷰에서 발표한 연구에 따르면, "대법원 서기직은 1940년대부터 1980년대까지 당파적이지 않은 기관으로 보였습니다."[233][234] 전 연방 항소 법원 판사 J. 마이클 러티그는 "법이 단순한 정치에 가까워짐에 따라 정치적 관계는 자연스럽고 예측 가능하게 법원과 법원을 통해 압박되어 온 다양한 정치적 의제의 대리인이 되었습니다."라고 말했습니다.[233] 캠브리지 대학의 역사학 교수인 데이비드 J. 개로우는 법원이 따라서 정부의 정치적인 부분들을 모방하기 시작했다고 말했습니다. "우리는 하원처럼 되어가는 서기 인력의 구성을 얻고 있습니다," 라고 Garrow 교수가 말했습니다. "각자 이념적 순수주의자만을 내세우고 있습니다."[233] Vanderbilt Law Review 연구에 따르면, 이러한 정치화된 채용 경향은 대법원이 "법치주의에 근거한 우려에 대응하는 법적 기관이라기보다는 이념적 주장에 대응하는 초입법"이라는 인상을 강화합니다.[233]

비판과 논란

대부분의 고등법원과는 달리, 미국 대법원은 종신 재직권, 선출된 정부 부처에 대한 비정상적인 권한, 그리고 개정하기 어려운 헌법을 가지고 있습니다.[235] 이러한 요인들은 무엇보다도 법원의 대외[236] 위상 감소와 국내 지지율 하락으로 인해 1980년대 후반 60년대 중반에서 2020년대 초 40% 정도로 떨어졌기 때문이라고 일부 비판론자들은 분석하고 있습니다. 비평가들이 인용한 추가적인 요인들은 국가 정치의 양극화, 윤리 스캔들, 그리고 선거 자금 규칙의 완화,[237] 투표권 약화를 포함한 특정한 논란이 많은 당파적 판결들을 포함합니다.[238] Dobbs v. Jackson and Bush v. Gore. 이 밖에 재판부에 대한 재판관 선발과 구성, 재판부 결정의 투명성 부족 등이 논란이 되고 있습니다.

지지율

대법원은 역사적으로 민주당과 공화당 모두에게 지속적으로 존경을 받아온 몇 안 되는 정치 기관 중 하나였습니다. 법원에 대한 대중의 신뢰는 1990년대 후반에 정점을 찍었습니다. 로 대 웨이드를 뒤집고 주 정부가 낙태 권리를 제한할 수 있도록 허용한 2022년 돕스 판결 이후 민주당과 무소속은 법원에 대한 신뢰를 점점 잃고 법원을 정치적인 것으로 간주하며 기관 개혁에 대한 지지를 표명했습니다.[239]

법원은 1980년대 후반 66% 안팎의 지지율로 최근 높은 지지율을 기록한 [240]뒤 2021년 중반부터 2024년 2월까지 평균 40% 안팎으로 하락했습니다.[241]

구성 및 선택

(재판관을 지명하는 대통령을 선출하는) 선거인단과 재판관을 확정하는 미국 상원은 공화당에 투표하는 경향이 있는 시골 주에 유리한 선택 편향을 가지고 있어 보수적인 대법원이 탄생합니다.[242] 지블라트와 레비츠키는 국민투표로 대통령직과 상원이 직접 뽑힐 경우 보수 성향 대법관들이 법정에서 차지하는 의석 중 서너 개는 민주당 대통령이 임명한 대법관들이 차지할 것으로 추정하고 있습니다.[243] 트럼프가 법정에 임명한 3명은 모두 국민투표에서 2위를 차지한 대통령이 지명했고, 소수 미국인을 대표하는 상원의원들이 확인했습니다.[244] 또한 2016년 클래런스 토마스의 인준과 메릭 갈랜드의 봉쇄된 인준은 모두 소수의 미국인을 대표하는 상원의원들에 의해 결정되었습니다.[245] 그렉 프라이스는 또한 법원을 소수자 지배라고 비판했습니다.[246]

게다가 연방주의자협회는 트럼프 행정부 시절 사법부 지명의 필터 역할을 [247]해 최신 보수 성향의 대법관들이 더욱 우파로 기울도록 했습니다.[242] 순회법원과 대법원에 임명된 트럼프 판사의 86%가 연방주의 학회 회원이었습니다.[248] 데이비드 리트(David Litt)는 "한때 지적 자유로 알려진 직업에 엄격한 이념적 도그마를 강요하려는 시도"라고 비판합니다.[249]

2016년 메릭 갈랜드의 인준에 대한 돌담과 그에 따른 닐 고서치의 충원은 선거 기간 동안 인준의 20세기 전례를 인용하여 '도둑맞은 자리'라는 비판을 받았고,[250][251] 지지자들은 1844년에서 1866년 사이에 세 번의 후보 지명이 차단되었다고 언급했습니다.[252] 최근 몇 년 동안 민주당은 미치 매코넬과 같은 공화당 지도자들이 메릭 갈랜드의 지명을 막는 데 중요한 역할을 했다고 위선적이라고 비난했지만, 두 자리 모두 선거 직전에 발생했음에도 불구하고 에이미 코니 배럿의 임명을 강행했습니다.[253]

윤리

윤리적 논란은 재판관들(그리고 그들의 가까운 가족들)이 이해 상충을 나타내는 사건에 대한 감독이나 기각 없이 고가의 선물, 여행, 사업 거래 및 발언료를 수수했다는 보도와 함께 커졌습니다.[254][255][256][257][258][259][260] 배우자의 수입과 사건에 대한 연관성은 대법관들의 윤리적 공개 양식에서[261] 축소되었고, 새뮤얼 알리토와 클래런스 토마스와 같은 대법관들은 50만 달러에 달하는 무료 휴가를 포함한 많은 거액의 금전적 선물을 공개하지 않았습니다.[262][263]

2023년 11월 13일, 법원은 "법원 구성원들의 행동을 인도하는 윤리 규칙과 원칙"을 정하는 최초의 미국 대법원 대법관 행동 강령을 발표했습니다.[264][265] 이 강령은 일반적으로 중요한 첫 단계로 받아들여졌지만, 연방 판사, 입법부 및 행정부에 대한 강령보다 상대적으로 약할 뿐만 아니라 집행 메커니즘이 부족하다고 생각한 많은 주목할 만한 비평가들의 윤리적 우려를 해결하지 못하는 조치로도 받아들여졌습니다.[266][267][268][269] 강령의 논평은 대법관들이 이러한 원칙을 대체로 지켜왔고 이제는 단순히 공표하고 있다고 말하면서 과거의 잘못을 부인했습니다.[270][271][272] 이것은 법원이 이 강령을 통해 과거와 미래의 스캔들을 합법화하기를 희망한다는 비판을 불러일으켰습니다.[273][274]

책임감 부족

법원 구성원들을 지도하는 윤리규칙은 재판관들이 정하고 집행하는데, 이는 법원 구성원들이 의회에 의한 법관 탄핵 외에는 그들의 행동에 대한 외부의 견제가 없다는 것을 의미합니다.[275][276] 로버츠 대법원장은 2023년 4월 상원 법사위원회에서 증언을 거부하면서 윤리 스캔들이 증가하고 있음에도 불구하고 대법원이 계속해서 감시하기를 원한다는 뜻을 재확인했습니다.[277] 대조적으로 하급 법원은 1980년 사법 행위 및 장애법에 의해 시행된 1973년 미국 판사 행동 강령에 따른 규율.[275]

미국 헌법(1776) 제3조 제1항은 재판관이 직무를 수행하는 동안 직무를 수행하도록 규정하고 있습니다. 지금까지 단 한 명의 대법관(1804년 새뮤얼 체이스 대법관)만이 탄핵된 적이 있지만, 단 한 명의 대법관도 해임된 적이 없습니다.[278]

윤리나 기타 행위 위반에 대한 외부의 집행이 부족하기 때문에 대법원은 현대 조직 모범 사례에서 이상한 위치에 있습니다.[275]

개인의 권리

개인의 권리를 보호하지 못했다고 비판을 받은 가장 주목할 만한 역사적 결정 중 일부는 노예제를 지지한 준드 스콧 (1857) 판결을 포함하며, 대법원장 테이니는 그의 의견에서 "[아프리카 미국인들은] 백인이 존중해야 할 권리가 없습니다.."또[279] 하나는 분리하되 평등하다는 교리 아래 분리를 지지한 플레시 대 퍼거슨(1896)입니다.[280] 또한 민권 사건(1883)과 도살장 사건(1873)은 재건 시대에 제정된 민권법제를 제외하고는 모두 폐지되었고, 이에 따라 짐 크로우 법의 길을 열었습니다.[281]

그러나 다른 사람들은 법원이 일부 개인의 권리, 특히 범죄로 기소되거나 구금된 사람들의 권리를 너무 보호한다고 주장합니다. 예를 들어, 워런 버거 대법원장은 배제 규정에 대해 거침없는 비판을 했고, 스칼리아 대법관은 부메딘 대 부시에서 법원의 결정이 인신 보호 영장이 주권 지역으로 제한되어야 한다는 이유로 관타나모 수용소의 권리를 너무 보호하고 있다고 비판했습니다.[282]

돕스 대 잭슨 여성 건강 기구가 로 대 웨이드가 세운 거의 50년의 선례를 뒤집은 후, 일부 전문가들은 이것이 실체적 적법 절차 원칙에 따라 이전에 확립되었던 개인의 권리에 대한 롤백의 시작일 수도 있다고 우려를 표명했습니다. Clarence Thomas 대법관이 Dobbs에 기고한 일치된 의견서에서 법원이 법원의 모든 실질적인 적법 절차 결정을 재고하도록 촉구해야 한다고 썼기 때문입니다.[283] 위험하다고 주장되는 적법 절차 권리는 다음과 같습니다.[283]

- 피임권을 포함한 사생활에 대한 권리. Griswold v. Connecticut(1965)에서 설립되었습니다.

- 사적인 성행위에 관한 프라이버시권. 로렌스 대에 설립되었습니다. 텍사스(2003).

- 동성인 개인과 혼인할 권리. Obergefell v. Hodges (2015)에 설립되었습니다.

뉴욕대 법대의 멜리사 머레이 교수와 같은 일부 전문가들은 러빙 대 버지니아 (1967)에서 확립된 인종 간 결혼에 대한 보호도 위험에 처할 수 있다고 주장했습니다.[284] 비록 사우스 텍사스 법대의 조시 블랙먼 교수와 같은 다른 전문가들은 러빙이 실질적인 적법 절차보다 동등한 보호 조항 근거에 더 많이 의존한다고 주장했습니다.[285]

그러나 그리즈월드와 그 자손들보다 더 중요한 것은 대법원이 주정부와 지방정부를 상대로 한 권리장전을 통합하기 위해 사용한 주요 수단이 실질적인 적법절차였다는 사실입니다.[286] 실제로 Clarence Thomas 대법관은 실질적인 적법 절차를 믿지 않으며 이를 '법적 허구'라고 언급했습니다.[287] 대신, 토마스는 특권 또는 면책 조항이 권리장전을 통합하기 위한 보다 건전한 수단이라고 주장해 왔습니다.[288] 안타깝게도 팀브 대에서 고르수치 대법관의 논평 밖에 있는 토마스에게 말입니다. 인디애나주에서 그는 이 의견에 대해 거의 지지를 받지 못했습니다.[289]

사법적극주의

대법원이 사법적극주의를 한다는 비판을 받기도 합니다. 이러한 비판은 법원이 과거의 판례나 텍스트주의의 관점 이외에는 어떠한 방식으로도 법을 해석해서는 안 된다고 믿는 사람들에 의해 제기됩니다. 그러나 정치적 통로의 양쪽에 있는 사람들은 종종 법정에서 이 비난을 제기합니다. 사법 행동주의를 둘러싼 논쟁은 일반적으로 상대방의 행동주의를 비난하는 동시에 자신의 편이 그것에 관여한다는 것을 부인하는 것을 포함합니다.[290]

보수주의자들은 종종 로 대 웨이드 (1973)의 결정을 자유주의적 사법 행동주의의 예로 인용합니다. 법원은 결정에서 수정헌법 14조의 적법절차 조항에 내재된 '사생활권'을 근거로 낙태를 합법화했는데,[291] 이는 일부 보수적 비판자들이 주장하는 근거입니다.[citation needed]

Roe v. Wade는 거의 50년 후 Dobbs v. Jackson (2022)에 의해 뒤집혔고, 낙태 접근을 헌법적 권리로 인정하는 것을 끝내고 낙태 문제를 다시 주로 돌려보냈습니다. 데이비드 리트는 돕스의 결정을 법원이 과거 선례를 존중하지 못했기 때문에 법원의 결정을 일반적으로 안내하는 스타 디시스의 원칙을 피했기 때문에 보수적인 다수당 측의 적극성이라고 비판했습니다.[292] 두 사건에 대한 반응은 양측이 상대방이 사법 행동주의에 관여하고 있다고 비난하는 경우가 많다는 것을 보여줍니다.[citation needed]

공립학교에서의 인종 차별을 금지한 브라운 대 교육위원회의 결정은 보수주의자 팻 뷰캐넌,[293] 로버트 보크[294], 배리 골드워터에 의해 운동가로서 비판을 받았습니다.[295] 더 최근에는 시티즌 유나이티드 v. 연방선거관리위원회는 수정헌법 제1조가 기업에 적용된다는 보스턴 제1국립은행 대 벨로티(1978) 판례를 확장하여 비판을 받았습니다.[296]

일부 전문가들은 앤서니 케네디 대법관이 "행동주의 법원은 마음에 들지 않는 결정을 내리는 법원"이라고 말하는 등 사법 행동주의에 대한 불만을 비판하고 있습니다.[297]

시대에 뒤떨어진 이상치

Colm Quinn은 법원뿐만 아니라 다른 미국 기관들에 대한 비판은 2세기 후에 그들이 그들의 나이를 보기 시작했다는 것이라고 말합니다. 그는 양극화가 미국 법원에서 쟁점이 되는 이유를 설명하는 데 도움이 되는 다른 나라의 고등법원과 다른 미국 대법원의 네 가지 특징을 인용합니다.[298]

- 미국 고등법원은 정치적 책임이 있는 다른 부서에서 통과된 법안을 일방적으로 부결시킬 수 있는 세계에서 몇 안 되는 법원 중 하나입니다.

- 미국 헌법은 개정하기가 매우 어렵습니다: 다른 나라들은 국민 투표를 통해 또는 입법부에서 압도적인 다수로 헌법 개정을 허용합니다.

- 미국 대법원은 정치화된 지명 절차를 가지고 있습니다.

- 미국 대법원은 임기 제한이나 의무 퇴직이 부족합니다.

힘

마이클 월드먼(Michael Waldman)은 다른 어떤 나라도 대법원에 그만큼의 권한을 주지 않는다고 주장했습니다.[299] 워렌 E. 버거는 대법원장이 되기 전 대법원이 이처럼 '검토할 수 없는 힘'을 갖고 있기 때문에 '스스로를 홀대할 가능성이 높고, '불온적 분석에 관여할 가능성이 낮다'고 주장했습니다.[300] 래리 사바토(Larry Sabato)는 연방 법원, 특히 대법원이 과도한 권한을 가지고 있다고 썼습니다.[101]

일부 의원들은 2021-2022년 임기의 결과를 대법원으로의 정부 권력 이동과 "사법 쿠데타"로 간주했습니다.[301] 2021-2022년 임기는 공화당 도널드 트럼프 대통령이 닐 고서치, 브렛 캐버노, 에이미 코니 배럿 등 3명의 판사를 임명한 데 이은 첫 번째 임기였습니다. 이로 인해 법원에서 6명의 보수 다수당이 탄생했습니다. 그 후, 임기 말에 법원은 권리와 관련하여 지형을 크게 바꾸면서 이러한 보수적인 다수를 선호하는 다수의 결정을 내렸습니다. 여기에는 로 대 웨이드와 계획된 부모 대 케이시를 뒤집은 돕스 대 잭슨 여성 건강 기구가 포함되었습니다. 케이시가 낙태를 인정하는 것은 헌법상의 권리가 아닙니다. 뉴욕 주 소총 및 권총 협회, 주식회사 대 브루엔, 수정헌법 제2조에 따라 총기를 공공 소유하는 것을 보호하는 권리로 만든 카슨 대 메이킨과 케네디 대. 교회와 주를 분리하는 설립 조항을 약화시킨 브레머튼 학군과 의회 권한을 해석하는 행정부 기관의 권한을 약화시킨 웨스트 버지니아 대 EPA.[302][303][304]

이러한 비판은 사법적극주의에 대한 불만과 관련이 있습니다.[citation needed] 조지 윌은 법원이 미국 통치에서 점점 더 중심적인 역할을 하고 있다고 썼습니다.[305][failed verification]

연방주의 논쟁

미국 역사를 통틀어 연방 권력과 주 권력의 경계에 대한 논쟁이 있었습니다. 제임스 매디슨(James Madison[306])과 알렉산더 해밀턴(Alexander Hamilton[307])과 같은 프래머들은 연방주의 논문에서 당시 제안된 헌법이 주 정부의 권력을 침해하지 않을 것이라고 주장했지만,[308][309][310][311] 다른 사람들은 확장적인 연방 권력이 좋고 프래머들의 바람과 일치한다고 주장합니다.[312] 미국 수정 헌법 제10조는 "헌법에 의해 미국에 위임되지도, 미국에 의해 금지되지도 않은 권한은 각각 미국 또는 국민에게 유보된다"고 명시적으로 부여하고 있습니다.

법원은 연방정부에 너무 많은 권한을 부여해 주 정부의 권한을 방해하고 있다는 비판을 받아왔습니다. 한 가지 비판은 연방 정부가 주간 상거래와 거의 관련이 없는 규정과 법률을 유지하고 주간 상거래를 방해한다는 이유로 주법을 회피함으로써 상거래 조항을 남용하도록 허용했다는 것입니다. 예를 들어, 상업 조항은 제5순회항소법원이 멸종위기종법을 지지하기 위해 사용한 것으로, 이 곤충이 상업적 가치가 없고 주 경계를 넘어 이동하지 않는다는 사실에도 불구하고 텍사스 오스틴 근처에 있는 6종의 고유종 곤충을 보호하기 위해 사용되었습니다. 대법원은 2005년에 그 판결을 논평 없이 그대로 두었습니다.[313] 존 마셜 대법원장은 주간 상거래에 대한 의회의 권한은 "그 자체로 완전하고, 최대한 행사할 수 있으며, 헌법에 규정된 것 외에는 제한을 인정하지 않는다"고 주장했습니다.[314] 알리토 대법관은 상업 조항에 따른 의회 권한은 "상당히 광범위하다"고 말했습니다.[315] 현대 이론가 로버트 B. Reich는 상거래 조항에 대한 논쟁이 오늘날에도 계속되고 있다고 제안합니다.[314]

헌법학자 케빈 구츠만과 같은 주의 권리 옹호자들도 수정헌법 14조를 국가 권위를 훼손하는 데 악용했다며 법원을 비난했습니다. 브랜다이스 대법관은 연방정부의 간섭 없이 주들이 운영될 수 있도록 허용해야 한다고 주장하면서 주들이 민주주의의 실험실이 되어야 한다고 제안했습니다.[316] 한 비평가는 "위헌에 대한 대법원 판결의 대다수는 연방법이 아닌 주법을 포함한다"고 썼습니다.[317] 다른 이들은 수정헌법 14조를 "그런 권리와 보장의 보호"를 주 차원으로 확장하는 긍정적인 힘으로 보고 있습니다.[318] 보다 최근에는 연방 권력 문제가 Gamble v. United States의 기소에서 중심이 되며, 이는 형사 피고인이 주 법원에 의해 기소된 후 연방 법원에 의해 기소될 수 있다는 "별도 주권자"의 교리를 검토하고 있습니다.[319][320]

정치적 질문에 대한 판결

일부 법원 결정은 법원을 정치 영역에 투입하고 선출된 정부 부처의 목적인 질문을 결정한다는 비판을 받았습니다. 대법원이 2000년 대통령 선거에 개입하여 조지 W. 부시에게 앨 고어에 대한 대통령직을 부여한 부시 대 고어 판결은 5명의 보수주의 판사들이 동료 보수주의자를 대통령으로 승진시키기 위해 사용한 논란의 여지가 있는 정당성에 근거하여 정치적인 것으로 정밀 조사를 받았습니다.[321][322][323][324][325]

민주당 백슬라이딩

토마스 켁은 법원이 역사적으로 민주주의의 강력한 보루 역할을 하지 않았기 때문에 로버츠 법원은 민주주의의 수호자로서 역사에 남을 기회를 가지고 있다고 주장합니다. 그러나 그는 법원이 (투표용지에 대한 접근을 보장한 후) 트럼프를 형사 기소로부터 보호한다면 현재 법원의 반민주적 지위 거부와 함께 오는 위험이 법원 개혁(법원 포장 포함)에서 오는 위험보다 더 클 것이라고 믿습니다.[326] 아지즈 지. Huq는 대법원이 민주적 패배가 불가능한 "영구적 소수"를 만들어냈다는 증거로 민주화 제도의 진전을 막고, 부와 권력의 격차를 늘리고, 권위주의적인 백인 민족주의 운동에 힘을 실어주고 있다고 지적합니다.[327]

비밀 절차

재판부는 그동안 심의 내용을 공개적으로 밝히지 않아 비판을 받아왔습니다.[328][329] 예를 들어, '그림자 문서'의 사용이 증가함에 따라 각 대법관이 어떻게 결정을 내렸는지 알지 못한 채 법원이 비밀리에 결정을 내리는 것이 용이해집니다.[330][331] 2024년, 그림자 결정에 대한 분석을 크렘린학과 비교한 후, 매트 포드는 이러한 비밀주의 경향을 "점점 더 문제가 되고 있다"며 법원의 힘은 전적으로 설득과 설명에서 나온다고 주장했습니다.[332]

제프리 투빈의 책에 대한 2007년 리뷰는 법원을 그 내부 작용이 대부분 알려지지 않은 카르텔에 비유하면서, 이러한 투명성의 결여가 조사를 감소시켜 극도로 결과적인 9명의 대법관에 대해 거의 알지 못하는 일반 미국인들에게 피해를 준다고 주장했습니다.[321] 2010년 여론조사에 따르면 미국 유권자의 61%가 법원 청문회를 텔레비전으로 중계하는 것이 "민주주의에 좋을 것"이라고 동의했고, 유권자의 50%는 TV로 중계하는 경우 법원 절차를 지켜보겠다고 답했습니다.[333][334]

사례가 너무 적음

앨런 스펙터 상원의원은 법원이 더 많은 사건을 결정해야 한다고 주장했습니다.[335] 스캘리아 대법관은 2009년 인터뷰에서 당시 재판부가 심리한 사건 수가 처음 대법원에 합류했을 때보다 적었다고 인정하면서도 사건 검토 여부를 결정하는 기준을 바꾸지 않았고, 동료들도 기준을 바꿨다고 믿지 않는다고 말했습니다. 그는 최소한 부분적으로 1980년대 후반에 많은 사건이 발생한 것은 법원을 통해 진행되고 있는 이전의 연방 법률 때문이라고 설명했습니다.[336]

너무 느림

영국 헌법학자 Adam Tomkins는 법원(특히 대법원)이 행정부와 입법부에 대한 견제 역할을 하도록 하는 미국 시스템의 결함을 보고 있습니다. 그는 법원이 때때로 사건들이 시스템을 통해 길을 찾기 위해 몇 년 동안 기다려야 하기 때문에, 그들의 다른 가지를 억제하는 능력이 심각하게 약화되었습니다.[337][338] 이에 비해 다른 여러 나라에서는 개인이나 정치기관이 제기한 헌법적 주장에 대해 원래 관할권을 갖는 전담 헌법재판소가 있는데, 예를 들어 독일 연방헌법재판소는 이의가 제기되면 위헌 결정을 내릴 수 있습니다.

시들해지는 영향력

아담 립탁(Adam Liptak)은 2008년에 법원이 다른 헌법 재판소들과의 관련성이 떨어졌다고 썼습니다. 그는 미국의 예외주의, 헌법이나 법원의 비교적 적은 업데이트, 법원의 우경화, 해외에서의 미국의 위상 감소 등을 예로 들고 있습니다.[236]

참고 항목

- 미국 연방 법원의 사법 임명 이력

- 논쟁의 오디오 또는 비디오를 게시하는 법원 목록

- 미합중국 대법원 판례 목록

- 미국의 대통령 목록

- 나라별 대법원 목록

- 미국 대법원 판례 목록

- 사법적 의사결정의 모델

- 미국 연방대법원 판결 전문기자

선정된 획기적인 대법원 판결

- 마버리 대 매디슨 (1803, 사법심사)

- 맥컬록 대 메릴랜드 (1819, 묵시적 권력)

- 기븐스 대 오그든 (1824, 주간통상)

- 드레드 스콧 대 샌드포드 (1857, 노예제)

- 민권사례(1883, 민권법)

- 플레시 대 퍼거슨 (1896, 인종은 분리되지만 동등하게 대우)

- Lochner v. New York (1905, 노동법)

- Buck v. Bell (1927, 강제 살균법 지지)

- 위커드 대 필번 (1942년, 연방정부의 경제활동 규제)

- 코레마츠 대 미국 (1942년, 일본인 유학)

- 브라운 대 교육위원회 (1954년, 인종의 학교 분리)

- Engel v. Vitale (1962, 공립학교에서 국가가 후원하는 기도)

- Abington School District v. Schempp (1963, 미국 공립학교에서 성경을 읽고 주님의 기도를 암송함)

- Gideon v. Wainwright (1963, 변호사 권리)

- Griswold v. Connecticut (1965, 피임)

- 미란다 대 애리조나 (1966, 경찰에 구금된 자들의 권리)

- In re Gault (1967, 청소년 용의자의 권리)

- 러빙 대 버지니아 (1967, 혼혈)

- Lemon v. Kurtzman (1971, 공립학교에서의 종교활동)

- New York Times v. United States (1971, 언론의 자유)

- 아이젠슈타트 대 베어드 (1972, 피임)

- 로 대 웨이드 (1973, 낙태)

- Miller v. California (1973, 외설)

- 미국 대 닉슨 (1974, 행정관 특권)

- Buckley v. Valeo (1976, 선거자금)

- Chevron v. N.R.D.C. (1984, 가장 많이 인용된 행정법 사건)[339]

- 부시 대 고어 (2000년, 대통령 선거)

- 로렌스 대. 텍사스(2003, sodomy)

- 컬럼비아 특별구 대 헬러 (2008년, 총기 권리)

- 시티즌 유나이티드 대 FEC (2010, 캠페인 파이낸스)

- 미국 대 윈저 (2013, 동성결혼)

- Shelby County v. Holder (2013, 의결권)

- Obergefell v. Hodges (2015, 동성결혼)

- 보스토크 대 클레이튼 카운티 (2020, LGBT 노동자 차별)

- 맥거트 대. 오클라호마 (2020년, 부족 유보권)

- 돕스 대 잭슨 여성 건강 기구 (2022, 낙태)

- 뉴욕 주 소총 및 권총 협회 대 브루엔 (2022, 총기)

- 공정 입학을 위한 학생 대 하버드 (2023년, 긍정적 조치)

참고문헌

- ^ Lawson, Gary; Seidman, Guy (2001). "When Did the Constitution Become Law?". Notre Dame Law Review. 77: 1–37. Archived from the original on October 26, 2020. Retrieved October 23, 2017.

- ^ 미국 헌법 제3조 제2항 이것은 수정헌법 11조에 의해 그 주의 시민이 아닌 사람들이 제기하는 주에 대한 소송을 제외하는 것으로 좁혀졌습니다.

- ^ "About the Supreme Court". Washington, D.C.: Administrative Office of the United States Courts. Archived from the original on December 15, 2020. Retrieved September 3, 2018.

- ^ Turley, Jonathan. "Essays on Article III: Good Behavior Clause". Heritage Guide to the Constitution. Washington, D.C.: The Heritage Foundation. Archived from the original on August 22, 2020. Retrieved September 3, 2018.

- ^ WIPO 국제 특허 사건 관리 사법 가이드: 미국 2022. SSRN 전자 저널. P.S. Menell, A.A. Schmitt. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.4106648.

- ^ Pushaw, Robert J. Jr. "Essays on Article III: Judicial Vesting Clause". Heritage Guide to the Constitution. Washington, D.C.: The Heritage Foundation. Archived from the original on August 22, 2020. Retrieved September 3, 2018.

- ^ Watson, Bradley C. S. "Essays on Article III: Supreme Court". Heritage Guide to the Constitution. Washington, D.C.: The Heritage Foundation. Archived from the original on August 22, 2020. Retrieved September 3, 2018.

- ^ a b "The Court as an Institution". Washington, D.C.: Supreme Court of the United States. Archived from the original on December 7, 2020. Retrieved September 3, 2018.

- ^ "Supreme Court Nominations: present–1789". Washington, D.C.: Office of the Secretary, United States Senate. Archived from the original on December 9, 2020. Retrieved September 3, 2018.

- ^ Hodak, George (February 1, 2011). "February 2, 1790: Supreme Court Holds Inaugural Session". abajournal.com. Chicago, Illinois: American Bar Association. Archived from the original on December 3, 2020. Retrieved September 3, 2018.

- ^ Pigott, Robert (2014). New York's Legal Landmarks: A Guide to Legal Edifices, Institutions, Lore, History, and Curiosities on the City's Streets. New York: Attorney Street Editions. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-61599-283-9.

- ^ "Building History". Washington, D.C.: Supreme Court of the United States. Archived from the original on December 5, 2020. Retrieved September 3, 2018.

- ^ Ashmore, Anne (August 2006). "Dates of Supreme Court decisions and arguments, United States Reports volumes 2–107 (1791–82)" (PDF). Library, Supreme Court of the United States. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 23, 2011. Retrieved April 26, 2009.

- ^ Shugerman, Jed. "A Six-Three Rule: Reviving Consensus and Deference on the Supreme Court". Georgia Law Review. 37: 893.

- ^ 아이언, 피터. A 대법원 사람들의 역사, p. 101(펭귄, 2006).

- ^ Scott Douglas Gerber, ed. (1998). "Seriatim: The Supreme Court Before John Marshall". New York University Press. p. 3. ISBN 0-8147-3114-7. Archived from the original on May 11, 2011. Retrieved October 31, 2009.

Finally many scholars cite the absence of a separate Supreme Court building as evidence that the early Court lacked prestige.

- ^ Manning, John F. (2004). "The Eleventh Amendment and the Reading of Precise Constitutional Texts". Yale Law Journal. 113 (8): 1663–1750. doi:10.2307/4135780. JSTOR 4135780. Archived from the original on July 16, 2019. Retrieved July 16, 2019.

- ^ Epps, Garrett (October 24, 2004). "Don't Do It, Justices". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 26, 2020. Retrieved October 31, 2009.

The court's prestige has been hard-won. In the early 1800s, Chief Justice John Marshall made the court respected

- ^ 대법원은 와레브 사건에서 사법심사권을 처음으로 행사했습니다. Hylton, (1796), 미국과 영국 간의 조약과 충돌하는 주법을 뒤집었습니다.

- ^ Rosen, Jeffrey (July 5, 2009). "Black Robe Politics" (book review of Packing the Court by James MacGregor Burns). The Washington Post. Archived from the original on August 14, 2020. Retrieved October 31, 2009.

From the beginning, Burns continues, the Court has established its "supremacy" over the president and Congress because of Chief Justice John Marshall's "brilliant political coup" in Marbury v. Madison (1803): asserting a power to strike down unconstitutional laws.

- ^ "The People's Vote: 100 Documents that Shaped America – Marbury v. Madison (1803)". U.S. News & World Report. 2003. Archived from the original on September 20, 2003. Retrieved October 31, 2009.

With his decision in Marbury v. Madison, Chief Justice John Marshall established the principle of judicial review, an important addition to the system of 'checks and balances' created to prevent any one branch of the Federal Government from becoming too powerful...A Law repugnant to the Constitution is void.

- ^ Sloan, Cliff; McKean, David (February 21, 2009). "Why Marbury V. Madison Still Matters". Newsweek. Archived from the original on August 2, 2009. Retrieved October 31, 2009.

More than 200 years after the high court ruled, the decision in that landmark case continues to resonate.

- ^ "The Constitution in Law: Its Phases Construed by the Federal Supreme Court" (PDF). The New York Times. February 27, 1893. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 17, 2020. Retrieved October 31, 2009.

The decision … in Martin vs. Hunter's Lessee is the authority on which lawyers and Judges have rested the doctrine that where there is in question, in the highest court of a State, and decided adversely to the validity of a State statute... such claim is reviewable by the Supreme Court ...

- ^ Ginsburg, Ruth Bader; Stevens, John P.; Souter, David; Breyer, Stephen (December 13, 2000). "Dissenting opinions in Bush v. Gore". USA Today. Archived from the original on May 25, 2010. Retrieved December 8, 2019.

Rarely has this Court rejected outright an interpretation of state law by a state high court … The Virginia court refused to obey this Court's Fairfax's Devisee mandate to enter judgment for the British subject's successor in interest. That refusal led to the Court's pathmarking decision in Martin v. Hunter's Lessee, 1 Wheat. 304 (1816).

- ^ a b "Decisions of the Supreme Court – Historic Decrees Issued in One Hundred and Eleven Years" (PDF). The New York Times. February 3, 1901. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 5, 2020. Retrieved October 31, 2009.

Very important also was the decision in Martin vs. Hunter's lessee, in which the court asserted its authority to overrule, within certain limits, the decisions of the highest State courts.

- ^ a b "The Supreme Quiz". The Washington Post. October 2, 2000. Archived from the original on April 29, 2011. Retrieved October 31, 2009.

According to the Oxford Companion to the Supreme Court of the United States, Marshall's most important innovation was to persuade the other justices to stop seriatim opinions—each issuing one—so that the court could speak in a single voice. Since the mid-1940s, however, there's been a significant increase in individual 'concurring' and 'dissenting' opinions.

- ^ Slater, Dan (April 18, 2008). "Justice Stevens on the Death Penalty: A Promise of Fairness Unfulfilled". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on August 14, 2020. Retrieved October 31, 2009.

The first Chief Justice, John Marshall set out to do away with seriatim opinions–a practice originating in England in which each appellate judge writes an opinion in ruling on a single case. (You may have read old tort cases in law school with such opinions). Marshall sought to do away with this practice to help build the Court into a coequal branch.

- ^ Suddath, Claire (December 19, 2008). "A Brief History of Impeachment". Time. Archived from the original on December 19, 2008. Retrieved October 31, 2009.

Congress tried the process again in 1804, when it voted to impeach Supreme Court Justice Samuel Chase on charges of bad conduct. As a judge, Chase was overzealous and notoriously unfair … But Chase never committed a crime—he was just incredibly bad at his job. The Senate acquitted him on every count.

- ^ Greenhouse, Linda (April 10, 1996). "Rehnquist Joins Fray on Rulings, Defending Judicial Independence". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 11, 2011. Retrieved October 31, 2009.

the 1805 Senate trial of Justice Samuel Chase, who had been impeached by the House of Representatives … This decision by the Senate was enormously important in securing the kind of judicial independence contemplated by Article III" of the Constitution, Chief Justice Rehnquist said

- ^ Edward Keynes; Randall K. Miller (1989). "The Court vs. Congress: Prayer, Busing, and Abortion". Duke University Press. ISBN 0-8223-0968-8. Archived from the original on May 11, 2011. Retrieved October 31, 2009.

(page 115)... Grier maintained that Congress has plenary power to limit the federal courts' jurisdiction.

- ^ Ifill, Sherrilyn A. (May 27, 2009). "Sotomayor's Great Legal Mind Long Ago Defeated Race, Gender Nonsense". U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved October 31, 2009.

But his decision in Dred Scott v. Sandford doomed thousands of black slaves and freedmen to a stateless existence within the United States until the passage of the 14th Amendment. Justice Taney's coldly self-fulfilling statement in Dred Scott, that blacks had "no rights which the white man [was] bound to respect," has ensured his place in history—not as a brilliant jurist, but as among the most insensitive

- ^ Irons, Peter (2006). A People's History of the Supreme Court: The Men and Women Whose Cases and Decisions Have Shaped Our Constitution. United States: Penguin Books. pp. 176–177. ISBN 978-0-14-303738-5.

The rhetorical battle that followed the Dred Scott decision, as we know, later erupted into the gunfire and bloodshed of the Civil War (p. 176)... his opinion (Taney's) touched off an explosive reaction on both sides of the slavery issue... (p. 177)

- ^ "Liberty of Contract?". Exploring Constitutional Conflicts. October 31, 2009. Archived from the original on November 22, 2009. Retrieved October 31, 2009.

The term 'substantive due process' is often used to describe the approach first used in Lochner—the finding of liberties not explicitly protected by the text of the Constitution to be impliedly protected by the liberty clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. In the 1960s, long after the Court repudiated its Lochner line of cases, substantive due process became the basis for protecting personal rights such as the right of privacy, the right to maintain intimate family relationships.

- ^ "Adair v. United States 208 U.S. 161". Cornell University Law School. 1908. Archived from the original on April 24, 2012. Retrieved October 31, 2009.

No. 293 Argued: October 29, 30, 1907 – Decided: January 27, 1908

- ^ Bodenhamer, David J.; James W. Ely (1993). The Bill of Rights in modern America. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. p. 245. ISBN 978-0-253-35159-3. Archived from the original on November 18, 2020. Retrieved October 29, 2020.

… of what eventually became the 'incorporation doctrine,' by which various federal Bill of Rights guarantees were held to be implicit in the Fourteenth Amendment due process or equal protection.

- ^ White, Edward Douglass. "Opinion for the Court, Arver v. U.S. 245 U.S. 366". Archived from the original on May 1, 2011. Retrieved March 30, 2011.

Finally, as we are unable to conceive upon what theory the exaction by government from the citizen of the performance of his supreme and noble duty of contributing to the defense of the rights and honor of the nation, as the result of a war declared by the great representative body of the people, can be said to be the imposition of involuntary servitude in violation of the prohibitions of the Thirteenth Amendment, we are constrained to the conclusion that the contention to that effect is refuted by its mere statement.

- ^ Siegan, Bernard H. (1987). The Supreme Court's Constitution. Transaction Publishers. p. 146. ISBN 978-0-88738-671-8. Archived from the original on February 20, 2021. Retrieved October 31, 2009.

In the 1923 case of Adkins v. Children's Hospital, the court invalidated a classification based on gender as inconsistent with the substantive due process requirements of the fifth amendment. At issue was congressional legislation providing for the fixing of minimum wages for women and minors in the District of Columbia. (p. 146)

- ^ Biskupic, Joan (March 29, 2005). "Supreme Court gets makeover". USA Today. Archived from the original on June 5, 2009. Retrieved October 31, 2009.

The building is getting its first renovation since its completion in 1935.

- ^ Justice Roberts (September 21, 2005). "Responses of Judge John G. Roberts, Jr. to the Written Questions of Senator Joseph R. Biden" (PDF). The Washington Post. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 30, 2015. Retrieved October 31, 2009.

I agree that West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish correctly overruled Adkins. Lochner era cases—Adkins in particular—evince an expansive view of the judicial role inconsistent with what I believe to be the appropriately more limited vision of the Framers.

- ^ Lipsky, Seth (October 22, 2009). "All the News That's Fit to Subsidize". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on December 19, 2013. Retrieved October 31, 2009.

He was a farmer in Ohio ... during the 1930s, when subsidies were brought in for farmers. With subsidies came restrictions on how much wheat one could grow—even, Filburn learned in a landmark Supreme Court case, Wickard v. Filburn (1942), wheat grown on his modest farm.

- ^ Cohen, Adam (December 14, 2004). "What's New in the Legal World? A Growing Campaign to Undo the New Deal". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 7, 2013. Retrieved October 31, 2009.

Some prominent states' rights conservatives were asking the court to overturn Wickard v. Filburn, a landmark ruling that laid out an expansive view of Congress's power to legislate in the public interest. Supporters of states' rights have always blamed Wickard ... for paving the way for strong federal action...

- ^ "Justice Black Dies at 85; Served on Court 34 Years". The New York Times. United Press International (UPI). September 25, 1971. Archived from the original on October 15, 2009. Retrieved October 31, 2009.

Justice Black developed his controversial theory, first stated in a lengthy, scholarly dissent in 1947, that the due process clause applied the first eight amendments of the Bill of Rights to the states.

- ^ "100 Documents that Shaped America Brown v. Board of Education (1954)". U.S. News & World Report. May 17, 1954. Archived from the original on November 6, 2009. Retrieved October 31, 2009.

On May 17, 1954, U.S. Supreme Court Justice Earl Warren delivered the unanimous ruling in the landmark civil rights case Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas. State-sanctioned segregation of public schools was a violation of the 14th amendment and was therefore unconstitutional. This historic decision marked the end of the "separate but equal" … and served as a catalyst for the expanding civil rights movement...

- ^ "Essay: In defense of privacy". Time. July 15, 1966. Archived from the original on October 13, 2009. Retrieved October 31, 2009.

The biggest legal milestone in this field was last year's Supreme Court decision in Griswold v. Connecticut, which overthrew the state's law against the use of contraceptives as an invasion of marital privacy, and for the first time declared the "right of privacy" to be derived from the Constitution itself.

- ^ Gibbs, Nancy (December 9, 1991). "America's Holy War". Time. Archived from the original on November 2, 2007. Retrieved October 31, 2009.

In the landmark 1962 case Engel v. Vitale, the high court threw out a brief nondenominational prayer composed by state officials that was recommended for use in New York State schools. 'It is no part of the business of government,' ruled the court, 'to compose official prayers for any group of the American people to recite.'

- ^ Mattox, William R. Jr; Trinko, Katrina (August 17, 2009). "Teach the Bible? Of course". USA Today. Archived from the original on August 20, 2009. Retrieved October 31, 2009.

Public schools need not proselytize—indeed, must not—in teaching students about the Good Book … In Abington School District v. Schempp, decided in 1963, the Supreme Court stated that "study of the Bible or of religion, when presented objectively as part of a secular program of education," was permissible under the First Amendment.

- ^ "The Law: The Retroactivity Riddle". Time. June 18, 1965. Archived from the original on April 23, 2008. Retrieved October 31, 2009.

Last week, in a 7 to 2 decision, the court refused for the first time to give retroactive effect to a great Bill of Rights decision—Mapp v. Ohio (1961).

- ^ "The Supreme Court: Now Comes the Sixth Amendment". Time. April 16, 1965. Archived from the original on May 28, 2010. Retrieved October 31, 2009.

Sixth Amendment's right to counsel (Gideon v. Wainwright in 1963). … the court said flatly in 1904: 'The Sixth Amendment does not apply to proceedings in state criminal courts.' But in the light of Gideon … ruled Black, statements 'generally declaring that the Sixth Amendment does not apply to states can no longer be regarded as law.'

- ^ "Guilt and Mr. Meese". The New York Times. January 31, 1987. Archived from the original on May 11, 2011. Retrieved October 31, 2009.

1966 Miranda v. Arizona decision. That's the famous decision that made confessions inadmissible as evidence unless an accused person has been warned by police of the right to silence and to a lawyer, and waived it.

- ^ Graglia, Lino A. (October 2008). "The Antitrust Revolution" (PDF). Engage. 9 (3). Archived from the original (PDF) on June 21, 2017. Retrieved February 6, 2016.

- ^ 얼 M. 말츠, 닉슨 법정의 도래: 1972년 임기와 헌법법의 변천(University of Kansas; 2016)

- ^ O'Connor, Karen (January 22, 2009). "Roe v. Wade: On Anniversary, Abortion Is out of the Spotlight". U.S. News & World Report. Archived from the original on March 26, 2009. Retrieved October 31, 2009.

The shocker, however, came in 1973, when the Court, by a vote of 7 to 2, relied on Griswold's basic underpinnings to rule that a Texas law prohibiting abortions in most situations was unconstitutional, invalidating the laws of most states. Relying on a woman's right to privacy...

- ^ "Bakke Wins, Quotas Lose". Time. July 10, 1978. Archived from the original on October 14, 2010. Retrieved October 31, 2009.

Split almost exactly down the middle, the Supreme Court last week offered a Solomonic compromise. It said that rigid quotas based solely on race were forbidden, but it also said that race might legitimately be an element in judging students for admission to universities. It thus approved the principle of 'affirmative action'…

- ^ "Time to Rethink Buckley v. Valeo". The New York Times. November 12, 1998. Archived from the original on May 11, 2011. Retrieved October 31, 2009.

...Buckley v. Valeo. The nation's political system has suffered ever since from that decision, which held that mandatory limits on campaign spending unconstitutionally limit free speech. The decision did much to promote the explosive growth of campaign contributions from special interests and to enhance the advantage incumbents enjoy over underfunded challengers.

- ^ a b "Supreme Court Justice Rehnquist's Key Decisions". The Washington Post. June 29, 1972. Archived from the original on May 25, 2010. Retrieved October 31, 2009.

Furman v. Georgia … Rehnquist dissents from the Supreme Court conclusion that many state laws on capital punishment are capricious and arbitrary and therefore unconstitutional.

- ^ 법원의 역사, 홀, 엘리 주니어, 그로스맨, 비첵 (eds.) 미국 대법원의 옥스포드 동반자. 옥스퍼드 대학교 출판부, 1992, ISBN 0-19-505835-6

- ^ "A Supreme Revelation". The Wall Street Journal. April 19, 2008. Archived from the original on August 24, 2017. Retrieved October 31, 2009.

Thirty-two years ago, Justice John Paul Stevens sided with the majority in a famous "never mind" ruling by the Supreme Court. Gregg v. Georgia, in 1976, overturned Furman v. Georgia, which had declared the death penalty unconstitutional only four years earlier.

- ^ Greenhouse, Linda (January 8, 2009). "The Chief Justice on the Spot". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 12, 2011. Retrieved October 31, 2009.

The federalism issue at the core of the new case grows out of a series of cases from 1997 to 2003 in which the Rehnquist court applied a new level of scrutiny to Congressional action enforcing the guarantees of the Reconstruction amendments.

- ^ Greenhouse, Linda (September 4, 2005). "William H. Rehnquist, Chief Justice of Supreme Court, Is Dead at 80". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved October 31, 2009.

United States v. Lopez in 1995 raised the stakes in the debate over federal authority even higher. The decision declared unconstitutional a Federal law, the Gun Free School Zones Act of 1990, that made it a federal crime to carry a gun within 1,000 feet of a school.

- ^ Greenhouse, Linda (June 12, 2005). "The Rehnquist Court and Its Imperiled States' Rights Legacy". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 5, 2011. Retrieved October 31, 2009.

Intrastate activity that was not essentially economic was beyond Congress's reach under the Commerce Clause, Chief Justice Rehnquist wrote for the 5-to-4 majority in United States v. Morrison.

- ^ Greenhouse, Linda (March 22, 2005). "Inmates Who Follow Satanism and Wicca Find Unlikely Ally". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 26, 2014. Retrieved October 31, 2009.

His (Rehnquist's) reference was to a landmark 1997 decision, City of Boerne v. Flores, in which the court ruled that the predecessor to the current law, the Religious Freedom Restoration Act, exceeded Congress's authority and was unconstitutional as applied to the states.

- ^ Amar, Vikram David (July 27, 2005). "Casing John Roberts". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 14, 2008. Retrieved October 31, 2009.

Seminole Tribe v. Florida (1996) In this seemingly technical 11th Amendment dispute about whether states can be sued in federal courts, Justice O'Connor joined four others to override Congress's will and protect state prerogatives, even though the text of the Constitution contradicts this result.

- ^ Greenhouse, Linda (April 1, 1999). "Justices Seem Ready to Tilt More Toward States in Federalism". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 11, 2011. Retrieved October 31, 2009.

The argument in this case, Alden v. Maine, No. 98-436, proceeded on several levels simultaneously. On the surface … On a deeper level, the argument was a continuation of the Court's struggle over an even more basic issue: the Government's substantive authority over the states.

- ^ Lindenberger, Michael A. "The Court's Gay Rights Legacy". Time. Archived from the original on June 29, 2008. Retrieved October 31, 2009.

The decision in the Lawrence v. Texas case overturned convictions against two Houston men, whom police had arrested after busting into their home and finding them engaged in sex. And for the first time in their lives, thousands of gay men and women who lived in states where sodomy had been illegal were free to be gay without being criminals.

- ^ Justice Sotomayor (July 16, 2009). "Retire the 'Ginsburg rule' – The 'Roe' recital". USA Today. Archived from the original on August 22, 2009. Retrieved October 31, 2009.

The court's decision in Planned Parenthood v. Casey reaffirmed the court holding of Roe. That is the precedent of the court and settled, in terms of the holding of the court.

- ^ Kamiya, Gary (July 5, 2001). "Against the Law". Salon. Retrieved November 21, 2012.

...the remedy was far more harmful than the problem. By stopping the recount, the high court clearly denied many thousands of voters who cast legal votes, as defined by established Florida law, their constitutional right to have their votes counted. … It cannot be a legitimate use of law to disenfranchise legal voters when recourse is available. …

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint : url-status (링크) - ^ Krauthammer, Charles (December 18, 2000). "The Winner in Bush v. Gore?". Time. Archived from the original on November 22, 2010. Retrieved October 31, 2009.

Re-enter the Rehnquist court. Amid the chaos, somebody had to play Daddy. … the Supreme Court eschewed subtlety this time and bluntly stopped the Florida Supreme Court in its tracks—and stayed its willfulness. By, mind you, …

- ^ MacDougall, Ian (November 1, 2020). "Why Bush v. Gore Still Matters in 2020". ProPublica. Retrieved March 18, 2024.

- ^ Payson-Denney, Wade (October 31, 2015). "So, who really won? What the Bush v. Gore studies showed CNN Politics". CNN. Retrieved March 18, 2024.

- ^ Babington, Charles; Baker, Peter (September 30, 2005). "Roberts Confirmed as 17th Chief Justice". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on January 16, 2010. Retrieved November 1, 2009.

John Glover Roberts Jr. was sworn in yesterday as the 17th chief justice of the United States, enabling President Bush to put his stamp on the Supreme Court for decades to come, even as he prepares to name a second nominee to the nine-member court.

- ^ Greenhouse, Linda (July 1, 2007). "In Steps Big and Small, Supreme Court Moved Right". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 17, 2009. Retrieved November 1, 2009.

It was the Supreme Court that conservatives had long yearned for and that liberals feared … This was a more conservative court, sometimes muscularly so, sometimes more tentatively, its majority sometimes differing on methodology but agreeing on the outcome in cases big and small.

- ^ Liptak, Adam (July 24, 2010). "Court Under Roberts Is Most Conservative in Decades". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 24, 2021. Retrieved February 1, 2019.

When Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. and his colleagues on the Supreme Court left for their summer break at the end of June, they marked a milestone: the Roberts court had just completed its fifth term. In those five years, the court not only moved to the right but also became the most conservative one in living memory, based on an analysis of four sets of political science data.

- ^ Caplan, Lincoln (October 10, 2016). "A new era for the Supreme Court: the transformative potential of a shift in even one seat". The American Prospect. Archived from the original on February 2, 2019. Retrieved February 1, 2019.

The Court has gotten increasingly more conservative with each of the Republican-appointed chief justices—Warren E. Burger (1969–1986), William H. Rehnquist (1986–2005), and John G. Roberts Jr. (2005–present). All told, Republican presidents have appointed 12 of the 16 most recent justices, including the chiefs. During Roberts's first decade as chief, the Court was the most conservative in more than a half-century and likely the most conservative since the 1930s.

- ^ Savage, Charlie (July 14, 2009). "Respecting Precedent, or Settled Law, Unless It's Not Settled". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 11, 2011. Retrieved November 1, 2009.

Gonzales v. Carhart—in which the Supreme Court narrowly upheld a federal ban on the late-term abortion procedure opponents call "partial birth abortion"—to be settled law.