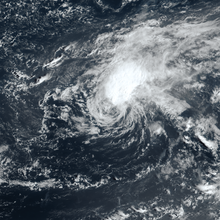

열대 저기압

Tropical cyclone| 시리즈의 일부 |

| 열대 저기압 |

|---|

| 열대성 저기압의 개요 |

열대 저기압은 저압 중심, 폐쇄된 저준위 대기 순환, 강풍 및 폭우 및/또는 돌풍을 일으키는 뇌우의 나선 배열로 특징지어지는 빠르게 회전하는 폭풍 시스템이다.열대 저기압은 위치와 강도에 따라 허리케인(/hhɪrɪknn, -ke/n/), 태풍(/taˈfufu/n/), 열대성 폭풍, 열대 저기압 또는 단순 사이클론 [citation needed]등 다양한 이름으로 불린다.허리케인은 대서양이나 북동 태평양에서 발생하는 강한 열대성 사이클론이고, 태풍은 북서 태평양에서 발생한다; 인도양, 남태평양 또는 (희귀한) 남대서양에서는 그에 상응하는 폭풍을 단순히 "열대성 사이클론"이라고 부르고, 인도양에서는 이러한 폭풍을 "세"라고도 부른다.'베레 사이클론 스톰'

"Tropical"은 거의 열대 바다에서만 형성되는 이러한 시스템의 지리적 기원을 나타냅니다."사이클론"은 바람이 북반구에서는 시계 반대 방향으로, 남반구에서는 시계 방향으로 불면서 중심 맑은 눈 주위를 돌며 원을 그리며 움직이는 것을 말한다.순환의 반대 방향은 코리올리 효과 때문이다.열대성 저기압은 일반적으로 비교적 따뜻한 물의 큰 몸 위에서 형성된다.그들은 해양 표면에서 물의 증발을 통해 에너지를 얻고, 습한 공기가 올라가고 포화상태로 냉각될 때 궁극적으로 구름과 비로 응축됩니다.이 에너지원은 주로 수평 온도 대비에 의해 추진되는 노이로스터 및 유럽 폭풍과 같은 중위도 사이클론 폭풍의 에너지원과 다르다.열대성 저기압은 일반적으로 직경이 100에서 2,000km 사이이다.매년 열대성 저기압은 북미, 호주, 인도, 방글라데시를 포함한 세계의 다양한 지역에 영향을 미친다.

열대 저기압의 강한 회전 바람은 공기가 회전축을 향해 안쪽으로 흐를 때 지구의 자전으로 인해 주어지는 각 운동량을 보존한 결과이다.그 결과, 적도에서 5° 이내에서는 거의 형성되지 않습니다.남대서양에서는 열대성 사이클론이 매우 드물다(가끔 발생하긴 하지만). 이는 지속적으로 강한 바람 전단(wind shear)과 약한 열대간 수렴대(intertropical convergence zone) 때문이다.반대로, 아프리카 동쪽 제트와 대기 불안정 지역은 대서양과 카리브해에서 사이클론을 발생시키고, 호주 근처의 사이클론은 아시아 몬순과 서태평양 온수지에서 발생하였다.

이러한 폭풍의 주요 에너지원은 따뜻한 바닷물입니다.따라서 이러한 폭풍은 일반적으로 물 위나 가까이 있을 때 가장 강하며 육지에서는 매우 빠르게 약해집니다.이로 인해 연안 지역은 내륙 지역에 비해 열대성 저기압에 특히 취약하다.해안 피해는 강풍과 비, 높은 파도(바람으로 인한), 폭풍 해일(바람과 심각한 압력 변화로 인한), 산란 토네이도의 가능성에 의해 발생할 수 있다.열대성 저기압은 넓은 지역에서 공기를 끌어들여 그 공기의 수분 함유량(물로부터 증발한 수분)을 훨씬 작은 지역의 강수량으로 집중시킨다.비 온 후에 습기를 머금은 공기가 보충되면 해안선에서 최대 40km(25mi)까지 수시간 또는 수일간 엄청난 폭우가 내릴 수 있으며, 이는 지역 대기가 한 번에 유지하는 물의 양을 훨씬 초과합니다.이로 인해 하천 범람, 육로 범람 및 넓은 지역에 걸친 국지적 물 제어 구조물의 일반적인 압도로 이어질 수 있다.비록 열대성 사이클론이 인구에 미치는 영향이 파괴적일 수 있지만, 이러한 주장은 논란의 여지가 있지만, 열대성 사이클론은 가뭄 상태를 완화시키는 역할을 할 수 있다.그들은 또한 열과 에너지를 열대지방에서 멀리 가져가 온대위도로 운반하는데, 이것은 지구 기후를 조절하는 데 중요한 역할을 한다.

배경

열대 저기압은 전 [1][2]세계 열대 또는 아열대 해역의 온열 코어, 비전방 시놉틱 스케일 저기압 시스템을 총칭하는 용어이다.이 시스템은 일반적으로 깊은 대기 대류 및 [1]지표면의 닫힌 바람 순환에 의해 둘러싸인 명확한 중심을 가지고 있다.

역사적으로 열대성 사이클론은 수천 년 동안 전 세계에서 발생했으며, 기록된 가장 초기의 열대성 사이클론 중 하나는 기원전 [3]4000년경에 서호주에서 발생한 것으로 추정됩니다.하지만, 20세기 동안 위성 사진을 이용할 수 있게 되기 전에, 이러한 시스템들 중 많은 것들이 [4]육지나 배가 우연히 그것을 마주치지 않는 한 감지되지 않았다.

오늘날, 매년 평균 80에서 90개의 명명된 열대성 사이클론이 전 세계에서 형성되는데, 그 중 절반 이상이 65kn 이상의 [4]허리케인 강풍을 일으킨다.일반적으로 열대 저기압은 35kn(65km/h; 40mph)을 초과하는 평균 표면 바람이 [4]관측되면 형성된 것으로 간주된다.이 단계에서는 열대 저기압은 자생적으로 발생하며 환경의 [4]도움 없이 계속 강해질 수 있다고 가정한다.

2021년 네이처 지오사이언스에 실린 연구 리뷰 기사에 따르면 해들리 [5]순환의 기후 온난화에 대응하여 열대성 사이클론의 지리적 범위가 극지방으로 확대될 것이라고 결론지었다.

분류 및 명명

명명 및 강도 분류

전 세계적으로 열대성 사이클론은 위치(열대성 사이클론 분지), 시스템 구조 및 강도에 따라 다양한 방식으로 분류된다.예를 들어 북대서양과 동태평양 분지에서는 풍속이 65kn(120km/h; 75mph) 이상인 열대성 사이클론을 허리케인이라고 하며, 서태평양이나 [6][7][8]북인도양에서는 태풍 또는 심각한 사이클론 폭풍이라고 부른다.남반구 내에서는 남대서양, 남서 인도양, 호주 지역 또는 [9][10]남태평양에 위치하는 것에 따라 허리케인, 열대 저기압 또는 심각한 열대 저기압으로 불린다.

명명

열대성 저기압을 식별하기 위해 이름을 사용하는 관행은 수년 전으로 거슬러 올라가며, 공식적으로 이름을 [11][12]짓기 전에 그들이 치는 장소나 물건의 이름을 따서 이름이 붙여졌다.현재 사용되는 시스템은 일반인이 [11][12]쉽게 이해하고 인식할 수 있는 간단한 형태로 혹독한 기상 시스템을 긍정적으로 식별한다.기상 시스템에 개인 이름을 처음 사용한 공적은 일반적으로 1887년과 [11][12]1907년 사이에 시스템을 명명했던 퀸즐랜드 정부 기상학자 클레멘트 워게에게 돌아간다.기상 시스템을 명명하는 이 시스템은 후에 Wragge가 은퇴한 후 몇 년 동안 사용되지 않게 되었고, [11][12]서태평양을 위해 제2차 세계 대전 후반에 부활했습니다.이후 북대서양과 남대서양, 동부, 중부, 서부, 남태평양 분지와 호주 지역 및 [12]인도양에 대한 정식 명칭 체계가 도입되었다.

현재 열대성 저기압은 12개의 기상 서비스 중 하나에 의해 공식적으로 명명되었으며 예보, 시계 및 [11]경고에 관한 기상 캐스터와 일반 대중 간의 의사소통을 용이하게 하기 위해 평생 그 이름을 유지한다.이 시스템은 일주일 이상 지속될 수 있고 동시에 같은 분지에서 여러 번 발생할 수 있기 때문에 어떤 폭풍이 설명되고 [11]있는지에 대한 혼동을 줄일 수 있을 것으로 생각됩니다.이름은 발생 [6][8][9]지역에 따라 1분, 3분 또는 10분 지속 풍속이 65km/h(40mph) 이상인 사전 결정된 목록에서 순서대로 지정된다.그러나 기준은 분지마다 다르며, 일부 열대 저기압은 서태평양에서 명명된 반면 열대 저기압은 남반구 내에서 [9][10]명명되기 전에 중심 주변에서 상당한 양의 강풍이 발생해야 한다.북대서양, 태평양 및 호주 지역에 있는 중요한 열대성 저기압의 이름은 명명 목록에서 삭제되고 다른 [6][7][10]이름으로 대체됩니다.전 세계에서 발달하는 열대성 저기압은 이들을 [10][13]감시하는 경고 센터에 의해 두 자리 숫자와 접미사 문자로 구성된 식별 코드가 할당된다.

강렬함

이 섹션은 확장해야 합니다.여기에 추가하시면 도움이 됩니다. (2021년 4월) |

기록된 가장 강력한 폭풍은 1979년 북서 태평양에서 발생한 태풍 팁으로, 최저 기압 870hPa(26inHg), 최대 지속 풍속 165kn(85m/s; 306km/h; 190mph)[14]에 도달했다.2015년 허리케인 패트리샤에서 기록된 최대 지속 풍속은 185kn(95m/s; 343km/h; 213mph)으로 서반구에서 기록된 [15]사이클론 중 가장 강력했다.

강도에 영향을 미치는 요인

열대성 저기압이 형성되고 강화되기 위해서는 따뜻한 해수면 온도가 필요하다.일반적으로 허용되는 최소 온도 범위는 26–27°C(79–81°F)이지만, 여러 연구에서 최소 25.5°C(77.9°[16][17]F)의 낮은 온도를 제안했다.해수면 온도가 높을수록 강도 상승 속도가 빨라지고 때로는 급격한 [18]강도 상승도 일어난다.열대성 사이클론 열 잠재력이라고도 알려진 높은 해양 열 함량은 폭풍을 더 높은 [19]강도로 만들 수 있습니다.급격한 강도를 경험하는 대부분의 열대성 저기압은 낮은 [20]값이 아니라 높은 해양 열 함량을 가진 지역을 가로지르고 있다.높은 해양 열 함량 값은 열대 저기압의 통과로 인한 해양 냉각을 상쇄하는 데 도움이 될 수 있으며, 이러한 냉각이 [21]폭풍에 미치는 영향을 제한할 수 있다.더 빠르게 움직이는 시스템은 낮은 해양 열 함량 값으로 더 높은 강도로 강화될 수 있습니다.느리게 움직이는 시스템은 동일한 [20]강도를 달성하기 위해 더 높은 해양 열 함량 값을 요구합니다.

열대 저기압의 해양 통과는 바다의 상층부를 실질적으로 냉각시키는 과정으로,[22] 상승으로 알려져 있으며, 이는 이후의 사이클론 발달에 부정적인 영향을 미칠 수 있다.이러한 냉각은 주로 바닷속 깊은 곳의 찬물과 따뜻한 지표수가 바람에 의해 혼합되면서 발생합니다.이 효과는 부정적인 피드백 프로세스를 초래하여 추가적인 개발을 저해하거나 약화를 초래할 수 있습니다.추가 냉각은 떨어지는 빗방울로 인해 차가운 물의 형태로 이루어질 수 있습니다(이것은 대기가 더 높은 고도에서 더 차가워지기 때문입니다).구름 덮개는 또한 폭풍 통과 전후의 직사광선으로부터 해면을 보호함으로써 바다를 냉각시키는 역할을 할 수 있다.이 모든 효과가 합쳐져 불과 며칠 [23]만에 넓은 지역에 걸쳐 해수면 온도가 극적으로 떨어질 수 있다.반대로, 바다의 혼합은 지구 [24]기후에 잠재적인 영향을 미치면서 더 깊은 물에 열을 주입하는 결과를 초래할 수 있다.

수직 윈드 시어는 시스템의 [25]중심에서 습기와 열을 이동시킴으로써 열대 저기압의 강도에 부정적인 영향을 미친다.낮은 수준의 수직 윈드시어가 강화에 가장 적합한 반면, 강한 윈드시어는 [26][27]약화를 유도한다.열대 저기압의 핵에 유입되는 건조한 공기는 대기 대류를 감소시키고 폭풍 구조에 [28][29][30]비대칭을 초래함으로써 발전 및 강도에 부정적인 영향을 미친다.대칭적이고 강한 유출은 국지적 [31][32][33]윈드시어를 완화함으로써 다른 시스템에서 관측된 것보다 더 빠른 강도 상승률로 이어진다.유출의 약화는 열대성 [34]사이클론 내의 레인밴드의 약화와 관련이 있다.

열대성 저기압의 크기는 열대성 저기압이 얼마나 빨리 강해지는지에 영향을 미친다.작은 열대성 저기압은 큰 [35]열대성 저기압보다 빠르게 강해지는 경향이 있다.두 열대 저기압 사이의 상호작용을 수반하는 후지와라 효과는 시스템의 대류 구성을 줄이고 수평 윈드시어를 [36]발생시킴으로써 약화되고 궁극적으로 두 열대 저기압 중 약한 쪽의 소멸을 초래할 수 있다.브라운오션 효과는 포화 [37]토양에서 잠열을 방출하여 많은 양의 비가 내린 경우, 상륙 후 열대 저기압의 강도를 유지하거나 증가시킬 수 있다.지형적 리프트는 열대 저기압의 눈이 산 위로 이동할 때 대류의 강도를 크게 증가시켜,[38] 사이클론을 억제하고 있던 경계층을 파괴할 수 있다.

형성

열대성 사이클론은 여름에 발달하는 경향이 있지만, 거의 매달 대부분의 열대성 사이클론 분지에서 발견되고 있다.ENSO와 매든-줄리안 진동과 같은 기후 주기는 열대 저기압의 [39][40]발생 시기와 빈도를 조절한다.적도 양쪽에 있는 열대성 저기압은 일반적으로 북동쪽이나 [41]남동쪽에서 바람이 부는 열대간 수렴대에서 유래한다.이 저기압의 넓은 영역 내에서, 공기는 따뜻한 열대 바다 위에서 가열되고 분리된 구획으로 상승하며, 이는 천둥 같은 [41]소나기를 형성하게 됩니다.이 소나기들은 매우 빠르게 소멸되지만, 큰 [41]뇌우 군집으로 뭉칠 수 있습니다.이것은 따뜻하고 습하며 빠르게 상승하는 공기의 흐름을 만들고,[41] 지구의 자전과 상호작용하면서 순환적으로 회전하기 시작합니다.

이러한 뇌우 더 발전할 몇가지 요인에 27°C의 해수면 온도가(81°F)과 낮은 수직풍 시어는 대류권, 충분한 코리올리의 힘은 저압 센터를 개발하고, pre-exi의 중간 수준으로 낮은의 system,[41][42]이 대기의 불안정, 높은 습도 환경이 요구된다.lo 쏘W 레벨의 포커스 또는 [42]장애.열대 저기압의 강도는 [43]그 경로를 따라 물의 온도와 강하게 관련되어 있다.열대성 폭풍의 강도를 가진 열대성 사이클론은 전 세계적으로 연평균 86개의 열대성 사이클론이 형성된다.그 중 47개는 119km/h(74mph) 이상의 강도에 도달하고, 20개는 강한 열대성 사이클론이 된다(사피르-심슨 [44]척도로는 최소한 범주 3).

강화

때로는 열대성 사이클론의 최대 지속 바람이 24시간 [45]이내에 30 kn(56 km/h; 35 mph) 이상 증가하는 기간인 급속강화(rapid instruction)로 알려진 과정을 거칠 수 있다.마찬가지로 열대성 저기압의 급속한 심화는 24시간 이내에 시간당 1.75hPa(0.052inHg) 또는 42hPa(1.2inHg)의 최소 해수면 압력 감소로 정의된다. 폭발적 심화는 최소 12시간 동안 표면 압력이 시간당 2.5hPa(0.074inHg) 감소할 때 발생한다.s.[46] 급속한 강화가 일어나려면 몇 가지 조건이 충족되어야 한다.수온은 매우 높아야 하며(30°C(86°F)에 가깝거나 그 이상) 수온은 파도가 표면까지 차오르는 일이 없도록 충분히 깊어야 한다.한편, 열대성 사이클론 열 잠재력은 사이클론 강도에 영향을 미치는 비-지하 해양학 매개변수 중 하나이다.윈드시어는 반드시 낮아야 한다. 윈드시어가 높으면 사이클론 내의 대류와 순환이 중단된다.일반적으로 폭풍 위 대류권 상층의 고기압도 존재해야 한다. 극도로 낮은 표면 압력이 발달하려면 폭풍의 안벽에서 공기가 매우 빠르게 상승해야 하며, 상층 고기압은 사이클론으로부터 공기를 효율적으로 [47]내보내는 데 도움이 된다.그러나 허리케인 엡실론과 같은 일부 사이클론은 상대적으로 좋지 [48][49]않은 조건에도 불구하고 빠르게 강해졌다.

소산

열대성 저기압은 열대성 특성을 약화시키거나 소멸시키거나 잃을 수 있는 여러 가지 방법이 있다.여기에는 상륙, 차가운 물 위로 이동, 건조한 공기와 마주치거나 다른 기상 시스템과의 상호작용이 포함된다. 그러나 시스템이 열대 특성을 소멸하거나 상실하면 환경 조건이 [50][51]좋아지면 그 잔존물이 열대 사이클론을 재생시킬 수 있다.

열대 저기압은 26.5°C(79.7°F)보다 훨씬 차가운 물 위를 이동할 때 소멸될 수 있다.이는 중심 부근에 뇌우를 동반한 따뜻한 중심핵과 같은 열대성 폭풍을 없애기 때문에 저기압의 잔존 지역이 된다.잔여 시스템은 정체성을 잃기 전에 며칠 동안 지속될 수 있습니다.이 소멸 메커니즘은 북태평양 동부에서 가장 흔합니다.폭풍우가 대류 및 열 엔진이 중심에서 멀어지게 하는 수직 윈드시어를 경험하는 경우에도 약화 또는 소멸이 발생할 수 있다. 이는 일반적으로 열대 [52]저기압의 개발을 중단한다.또한, 인근 전방 영역과 병합하여 서풍의 주요 띠와의 상호작용으로 열대 저기압이 온대 저기압으로 진화할 수 있다.이 이행에는 1~[53]3일이 소요될 수 있습니다.

열대성 사이클론이 상륙하거나 섬 위를 지나가면, 특히 산악 [54]지형을 만나면 순환이 중단되기 시작할 수 있다.시스템이 넓은 육지에 상륙하면 따뜻하고 습한 해양 공기의 공급이 차단되고 건조한 대륙 [54]공기로 유입되기 시작합니다.이는 육지 지역의 마찰 증가와 함께 열대 저기압의 [54]약화 및 소멸로 이어진다.산악지대에서는 시스템이 빠르게 약해질 수 있지만, 평지에서는 순환이 중단되어 [54]소멸될 때까지 2~3일 정도 지속될 수 있습니다.

수년간 열대성 [55]저기압을 인위적으로 수정하기 위해 고려된 많은 기술들이 있다.이러한 기술에는 핵무기 사용, 빙산으로 바다를 식히는 것, 거대한 팬으로 육지에서 폭풍을 불어내는 것, 그리고 선별된 폭풍에 드라이아이스나 [55]요오드화은을 뿌리는 것이 포함되어 있다.그러나 이러한 기법은 열대성 [55]사이클론의 지속 시간, 강도, 전력 또는 크기를 인식하지 못한다.

강도 평가 방법

열대 저기압의 강도를 평가하기 위해 지표면, 위성, 항공을 포함한 다양한 방법이나 기술을 사용한다.정찰기는 시스템의 [4]바람과 압력을 확인하는 데 사용할 수 있는 정보를 수집하기 위해 특수 기구를 갖춘 열대성 사이클론 주위를 날아다닌다.열대성 저기압은 다양한 높이에서 다른 속도의 바람을 가지고 있다.비행 수준에서 기록된 바람은 [56]지표면의 풍속을 구하기 위해 변환될 수 있다.선박 보고서, 육상 관측소, 중간자, 해안 관측소, 부표와 같은 지표 관측은 열대 저기압의 강도나 [4]진행 방향에 대한 정보를 제공할 수 있다.풍압관계(WPR)는 풍속에 기초한 폭풍의 압력을 결정하는 방법으로 사용된다.WPR을 [57][58]계산하기 위해 몇 가지 다른 방법과 방정식이 제안되었습니다.열대성 사이클론 기관은 각각 자체 고정 WPR을 사용하므로 동일한 시스템에 [58]대한 추정치를 발행하는 기관 간에 부정확성이 발생할 수 있다.ASCAT는 MetOp 위성이 열대 저기압의 [4]풍장 벡터를 매핑하는 데 사용하는 산란계이다.SMAP는 L-밴드 방사선계 채널을 사용하여 해수면에서 열대성 사이클론의 풍속을 결정하며, 산란계 기반 및 기타 방사선계 기반 [59]계측기와 달리 고강도 및 폭우 조건에서 신뢰할 수 있는 것으로 나타났다.

드보락 기법은 열대 저기압의 분류와 강도 결정에 큰 역할을 한다.경고 센터에서 사용되는 이 방법은 1970년대에 Vernon Dvorak에 의해 개발되었으며 열대 저기압 강도 평가에 가시 및 적외선 위성 이미지를 모두 사용한다.드보락 기법은 "T-numbers" 척도를 사용하며, T1.0에서 T8.0까지 from 단위로 스케일링한다.각 T번호에는 강도가 할당되어 있으며 T번호가 클수록 시스템이 강함을 나타냅니다.열대성 사이클론은 T-값을 결정하고 [60]폭풍의 강도를 평가하기 위해 곡선 밴딩 특성, 전단, 중심 밀도 구름 및 눈을 포함한 패턴 배열에 따라 기상 캐스터에 의해 평가된다.기상 위성 연구 협력 기관은 고급 드보락 기술(ADT)과 SATCON과 같은 자동화된 위성 방법을 개발하고 개선하기 위해 일한다.많은 예측 센터에서 사용되는 ADT는 적외선 정지 위성 이미지와 드보락 기술에 기초한 알고리즘을 사용하여 열대 저기압의 강도를 평가한다.ADT는 강도 제약 규칙에 대한 변경과 적외선 영상에 [61]눈이 나타나기 전에 강도가 안정되는 것을 방지하는 내부 구조를 기반으로 하는 마이크로파 이미지의 사용을 포함하여 기존의 드보락 기술과 많은 차이점을 가지고 있다.SATCON은 다양한 위성 기반 시스템과 마이크로파 사운더의 추정을 각 개별 추정치의 강점과 결점을 고려하여 드보락 기법보다 신뢰할 [62][63]수 있는 열대 저기압 강도의 합의 추정을 도출한다.

강도 측정 기준

누적 사이클론 에너지(ACE), 허리케인 서지 지수, 허리케인 심각도 지수, 전력 소산 지수(PDI), 통합 운동 에너지(IKE)를 포함한 여러 강도 메트릭이 사용된다.ACE는 시스템이 수명 동안 소비한 총 에너지의 메트릭입니다.ACE는 시스템이 열대 폭풍 강도 이상이고 열대 [64]또는 아열대인 한 6시간마다 사이클론의 지속 풍속 제곱을 합산하여 계산한다.PDI의 계산은 본질적으로 ACE와 유사하지만, 풍속이 [65]제곱이 아니라 제곱이라는 점이 가장 큰 차이입니다.허리케인 서지 지수는 폭풍 해일로 인한 잠재적 피해의 지표이다.폭풍 풍속과 기후학적 값(74mph)의 배당을 제곱한 다음, 그 양에 허리케인-힘 바람의 반지름과 기후학적 값(96.6km(60.0mi))의 배당을 곱하여 계산한다.이는 다음과 같이 방정식 형식으로 나타낼 수 있습니다.

여기서 v는 폭풍의 풍속이고 r은 허리케인-강풍 [66]반지름입니다.허리케인 심각도 지수는 시스템에 최대 50점을 할당할 수 있는 척도이다. 최대 25점은 강도에서 나오는 반면, 나머지 25점은 폭풍의 바람장 [67]크기에서 오는 것이다.IKE 모델은 바람, 파도, 해일을 통해 열대 저기압의 파괴력을 측정합니다.계산은 다음과 같습니다.

여기서 p는 공기의 밀도, u는 지속적인 표면 풍속 값, d는v 부피 [67][68]요소입니다.

구조.

눈과 중심

성숙한 열대성 저기압의 중심에서 공기는 상승하지 않고 가라앉는다.충분히 강한 폭풍우의 경우, 공기가 구름 형성을 억제할 수 있을 정도로 깊은 층 위로 가라앉아 맑은 "눈"을 만들 수 있습니다.눈 속의 날씨는 보통 평온하고 대류 구름이 없지만, 바다는 매우 [69]격렬할 수 있다.눈은 일반적으로 원형이며 지름이 30-65km(19-40mi)이지만, 3km(1.9mi)에서 370km(230mi)만큼 큰 눈이 [70][71]관찰되었다.

흐린 눈의 바깥쪽 가장자리는 "눈벽"이라고 불립니다.안벽은 일반적으로 높이와 함께 바깥쪽으로 확장되어 아레나 축구 경기장과 유사하다. 이러한 현상을 "스타디움 효과"[71]라고 부르기도 한다.안벽은 가장 빠른 풍속이 발견되고, 공기가 가장 빠르게 상승하며, 구름이 가장 높은 고도에 도달하고, 강수량이 가장 많은 곳이다.가장 큰 바람 피해는 열대성 사이클론의 안벽이 [69]육지를 통과할 때 발생한다.

약한 폭풍의 경우, [72]눈은 열대 저기압의 중심 부근에 강한 뇌우 활동이 집중된 영역과 연관된 상부 레벨의 권상층 구름에 의해 가려질 수 있다.

안벽은 시간이 지남에 따라 특히 강한 열대성 저기압에서 안벽 교체 주기의 형태로 변할 수 있습니다.외부 비대는 천천히 안쪽으로 이동하는 뇌우의 외부 고리 모양으로 형성될 수 있는데, 이것은 일차 안벽의 습기와 각운동량을 빼앗는 것으로 여겨진다.1차 안벽이 약해지면 열대성 저기압은 일시적으로 약해진다.외측 안벽은 결국 주기가 끝날 때 1차 안벽을 대체하며, 이때 폭풍이 원래 [73]강도로 되돌아갈 수 있습니다.

크기

스톰 크기를 측정하기 위해 일반적으로 사용되는 다양한 메트릭이 있습니다.가장 일반적인 메트릭에는 최대 바람의 반지름, 34-노트(17m/s; 63km/h; 39mph) 바람의 반지름(즉, 강풍력), 최외측 폐쇄형 이소바(ROCI)의 반지름 및 소멸 [74][75]바람의 반지름이 포함된다.추가 지표는 사이클론의 상대 소용돌이장이 1×[71]10초로−5−1 감소하는 반지름이다.

| 열대성 사이클론의 크기 설명 | |

|---|---|

| ROCI(직경) | 유형 |

| 위도 2도 미만 | 초소형/소형 |

| 위도 2~3도 | 작은. |

| 위도 3~6도 | 중간/평균/보통 |

| 위도 6~8도 | 큰. |

| 위도 8도 이상 | 매우[76] 크다 |

지구에서 열대성 사이클론은 소멸되는 바람의 반경으로 측정하면 100-2,000km(62-1243mi)의 광범위한 크기에 걸쳐 있다.이들은 평균적으로 북서 태평양 유역에서 가장 크고 북동 태평양 [77]유역에서 가장 작습니다.가장 바깥쪽 폐쇄된 이소바의 반경이 위도 2도(222km(138mi) 미만인 경우 사이클론은 "매우 작음" 또는 "미드겟"이다.위도 3~6도(333–670km(207–416mi)의 반지름은 "평균 크기"로 간주된다."매우 큰" 열대성 저기압의 반경은 8도 이상이다.[76]관측 결과에 따르면 크기는 폭풍 강도(즉, 최대 풍속), 최대 바람 반지름, 위도 및 최대 잠재 [75][77]강도와 같은 변수와 약하게 상관된다.태풍 팁은 직경 2,170 km (1,350 mi)의 열대성 폭풍우를 동반한 역사상 가장 큰 사이클론이다.기록된 가장 작은 폭풍은 직경 [78]37km(23mi)의 열대성 폭풍 마르코(2008)이다.

움직임.

열대 저기압(즉, "트랙")의 이동은 일반적으로 배경 환경 바람에 의한 "스티어링"과 "베타 드리프트"[79]라는 두 가지 용어의 합으로 근사된다.1994년 [80][81]북반구 열대성 사이클론 중 가장 긴 궤적인 13,280 km (8,250 mi)를 이동한 기록상 가장 긴 열대성 사이클론인 허리케인 존과 같은 일부 열대성 사이클론은 먼 거리를 이동할 수 있다.

환경 스티어링

환경 스티어링은 열대성 [82]사이클론의 움직임에 주된 영향을 미칩니다.이는 "하천을 따라 나르는 나뭇잎"[83]과 유사하게, 우세한 바람과 다른 더 넓은 환경 조건에 의한 폭풍의 움직임을 나타냅니다.

물리적으로 열대 사이클론 근처의 바람 또는 흐름장은 폭풍 자체와 관련된 흐름과 환경의 [82]대규모 백그라운드 흐름의 두 부분으로 처리될 수 있다.열대성 저기압은 환경의 [84]대규모 백그라운드 흐름 내에서 현탁된 국소적 소용돌이 최대치로 취급할 수 있다.이와 같이 열대성 사이클론 운동은 국지적인 [85]환경 흐름에 의한 폭풍의 이류로 1차적으로 표현될 수 있다.이러한 환경 흐름을 "스티어링 흐름"이라고 하며 열대 저기압 운동에 [82]대한 주요 영향이다.조향 흐름의 강도와 방향은 사이클론 근처에서 수평으로 부는 바람의 수직적 통합으로 근사할 수 있으며, 바람이 발생하는 고도에 따라 가중치가 부여된다.바람은 높이에 따라 달라질 수 있기 때문에 조향 흐름을 정확하게 결정하는 것은 어려울 수 있습니다.

배경 바람이 열대 사이클론의 움직임과 가장 관련이 있는 압력 고도를 "조향 수준"[84]이라고 한다.더 강한 열대 저기압의 움직임은 더 낮은 대류권의 좁은 범위에서 평균된 배경 흐름과 더 많은 상관관계가 있는 약한 열대 저기압에 비해 대류권의 [86]더 두꺼운 부분에 평균된 배경 흐름과 더 관련이 있다.윈드 시어와 잠열 방출이 있을 때 열대성 사이클론은 잠재적 소용돌이성이 가장 [87]빠르게 증가하는 지역으로 이동하는 경향이 있다.

기후학적으로 열대성 저기압은 주로 아열대 [83]해역의 적도 쪽에서 부는 동서 무역풍에 의해 서쪽으로 이동한다.열대 북대서양과 북동 태평양에서 무역풍은 열대성 동파를 아프리카 해안에서 서쪽으로 카리브해, 북미, 그리고 궁극적으로 [88]파도가 가라앉기 전에 중앙 태평양으로 향하게 합니다.이 파도는 이 [89]지역 내의 많은 열대성 저기압의 전조이다.이와는 대조적으로, 양쪽 반구의 인도양과 서태평양에서는 열대성 사이클로제네이션은 열대성 동파의 영향을 덜 받고, 열대간 수렴대와 몬순 [90]기압골의 계절적 이동에 의해 영향을 더 많이 받는다.중위도 기압골과 넓은 몬순 회전과 같은 다른 기상 시스템도 조향 [86][91]흐름을 변경함으로써 열대 저기압의 움직임에 영향을 미칠 수 있다.

베타 드리프트

환경 조향과 더불어 열대 저기압은 "베타 드리프트"[92]라고 알려진 운동인 극과 서쪽으로 표류하는 경향이 있습니다.이러한 움직임은 열대 저기압과 같은 소용돌이가 구면이나 베타 [93]평면과 같이 위도에 따라 변화하는 환경에 중첩되기 때문입니다.베타 드리프트와 관련된 열대 저기압 운동 성분의 크기는 1-3m/s(3.6-10.8km/h; 2.2-6.7mph) 사이이며, 더 강한 열대 저기압과 더 높은 위도에서 더 큰 경향이 있다.그것은 폭풍의 사이클론 흐름과 [94][92]그 환경 사이의 피드백의 결과로 폭풍 자체에 의해 간접적으로 유도된다.

물리적으로 폭풍의 사이클론 순환은 중심에서 동쪽으로, 중심에서 서쪽으로 적도 방향으로 환경 공기를 유입시킨다.공기는 각운동량을 보존해야 하기 때문에, 이 흐름 구성은 폭풍 중심에서 적도 방향으로 서쪽으로, 그리고 폭풍 중심에서 극 방향으로 동쪽으로 고기압 회전을 유도합니다.이 회오리들의 결합된 흐름은 폭풍을 천천히 극과 서쪽으로 이류시키는 역할을 한다.이 효과는 환경 흐름이 [95][96]0인 경우에도 발생합니다.베타 드리프트가 각운동량에 직접적으로 의존하기 때문에, 열대 저기압의 크기는 베타 드리프트의 움직임에 영향을 미칠 수 있다. 베타 드리프트는 작은 열대 [97][98]저기압보다 큰 열대 저기압의 움직임에 더 큰 영향을 미친다.

다중 스톰 상호작용

비교적 드물게 발생하는 운동의 세 번째 요소는 여러 열대 저기압의 상호작용을 수반한다.두 개의 사이클론이 서로 접근하면, 그 중심은 두 시스템 사이의 한 지점을 중심으로 사이클론 궤도를 돌기 시작할 것이다.이격 거리와 강도에 따라 두 소용돌이는 단순히 서로 궤도를 돌거나 중심점으로 소용돌이쳐 합쳐질 수 있습니다.두 소용돌이의 크기가 동일하지 않을 경우, 큰 소용돌이가 상호작용을 지배하고 작은 소용돌이가 그 주위를 공전하는 경향이 있습니다.이 현상은 [99]후지와라 사쿠헤이의 이름을 따서 후지와라 효과라고 불립니다.

중위도 편서풍과의 상호작용

열대 저기압은 일반적으로 열대지방에서 동쪽에서 서쪽으로 이동하지만, 그 궤도는 아열대 능선 축의 서쪽으로 이동할 때 극과 동쪽으로 이동하거나 제트 기류나 온대 저기압과 같은 중위도 흐름과 상호작용할 때 이동할 수 있다."반복"이라고 불리는 이 움직임은 제트 기류가 일반적으로 극방향 구성 요소를 가지며 온대성 사이클론이 일반적인 [100]주요 해양 분지의 서쪽 가장자리 근처에서 흔히 발생한다.열대성 사이클론 재발의 예로는 2006년 [101]태풍 이오케가 있다.

형성지역 및 경고센터

| 열대성 사이클론 분지와 공식 경보 센터 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 분지 | 경고 센터 | 담당 분야 | 메모들 |

| 북반구 | |||

| 북대서양 | 미국 국립 허리케인 센터 | 적도 북쪽, 아프리카 연안 – 140°W | [6] |

| 동태평양 | 미국 중부 태평양 허리케인 센터 | 적도 북쪽, 140~180°W | [6] |

| 서태평양 | 기상청 | 적도 – 60°N, 180~100°E | [7] |

| 북한 인도양 | 인도 기상청 | 적도 북쪽으로, 100–40°E | [8] |

| 남반구 | |||

| 서남부 인도양 | 메테오-프랑스 재결합 | 적도 – 40°S, 아프리카 연안 – 90°E | [9] |

| 오스트레일리아 지역 | 인도네시아 기상·기후· 지구물리학청(BMKG) | 적도 – 10°S, 90~141°E | [10] |

| 파푸아뉴기니 국립 기상국 | 적도 – 10°S, 141~160°E | [10] | |

| 오스트레일리아 기상국 | 10~40°S, 90~160°E | [10] | |

| 남태평양 | 피지 기상청 | 적도 – 25°S, 160°E – 120°W | [10] |

| 뉴질랜드 기상청 | 25~40°S, 160°E~120°W | [10] | |

매년 열대 저기압의 대부분은 7개의 열대 저기압 분지 중 하나에서 형성되며, 다양한 기상 서비스 및 경보 센터에서 [4]이를 모니터링한다.전 세계 10개 경고센터는 세계기상기구(WMO)의 열대 사이클론 프로그램에 [4]의해 지역특화기상센터 또는 열대 사이클론 경고센터로 지정된다.이러한 경고 센터는 기본 정보를 제공하고 지정된 [4]책임 영역의 현재 시스템, 예측 위치, 이동 및 강도를 포함하는 권고 사항을 발행합니다.전 세계 기상국은 일반적으로 자국에 대한 경보를 발령할 책임이 있지만,[4][10] 미국 국립 허리케인 센터와 피지 기상청이 책임 영역의 다양한 섬 국가에 경보, 경계 및 경보를 발령하기 때문에 예외가 있다.미국 합동태풍경보센터와 함대기상센터는 또한 [4]미국 정부를 대표하여 열대성 저기압에 대한 경보를 공개적으로 발령한다.브라질 해군 수로 센터는 남대서양 열대 저기압으로 명명하고 있지만, [102]WMO에 따르면 남대서양은 주요 분지도 아니고 공식 분지도 아니다.

준비

이 섹션은 확장해야 합니다.여기에 추가하시면 도움이 됩니다. (2021년 4월) |

본격적인 시즌이 시작되기 전에, 사람들은 특히 정치인들과 기상 캐스터들에 의해 열대성 사이클론의 영향에 대비해야 한다.그들은 다양한 날씨, 열대성 사이클론의 원인에 대한 위험성을 판단하고, 보험 적용 범위와 비상용품을 확인하고,[103][104][105] 필요할 경우 어디로 대피할지를 결정함으로써 준비한다.열대성 사이클론이 발달하여 육지에 영향을 미칠 것으로 예상되면, 세계기상기구의 각 회원국은 예상되는 [106]영향을 커버하기 위해 다양한 주의보와 경보를 발령한다.그러나 미국 국립허리케인센터와 피지기상국은 해당 국가의 [107][108][109]: 2–4 책임 영역에 있는 다른 국가에 경보를 발령하거나 권고할 책임이 있다.

영향

열대성 사이클론으로 인해 발생하거나 악화되는 자연 현상

열대성 저기압은 바다에서 큰 파도, 폭우, 홍수와 강풍을 일으켜 국제 선박을 방해하고 때로는 [110]난파선을 일으킨다.열대성 저기압은 물을 휘젓고, 그 뒤에 시원한 기류를 남기며, 이는 그 지역이 후속 열대성 [23]저기압에 덜 우호적이게 만든다.육지에서는 강풍이 차량, 건물, 다리 및 기타 외부 물체를 손상시키거나 파괴하여 느슨한 파편을 치명적인 비행체로 만들 수 있습니다.폭풍 해일 또는 사이클론으로 인한 해수면 상승은 일반적으로 열대 저기압의 상륙으로 인한 최악의 영향이며, 열대 저기압 [111]사망의 90%를 초래한다.사이클론 마히나는 1899년 [112]3월 호주 퀸즐랜드 주 배서스트 베이에서 13m(43피트)의 기록적인 폭풍 해일을 일으켰다.열대성 사이클론이 발생시키는 다른 해양 기반 위험은 이안류와 해저이다.이러한 위험은 다른 [113][114]기상 조건이 양호하더라도 사이클론 중심에서 수백 킬로미터 떨어진 곳에서 발생할 수 있습니다.상륙하는 열대 저기압의 광범위한 회전과 그 주변부의 수직 바람의 시어는 토네이도를 발생시킨다.토네이도는 또한 [115]상륙할 때까지 지속되는 안벽 중피질 때문에 발생할 수 있다.허리케인 이반은 [116]총 120개의 토네이도를 발생시키면서 다른 어떤 열대 사이클론보다 더 많은 토네이도를 발생시켰다.번개 활동은 열대성 사이클론 내에서 발생하며, 이 활동은 더 강한 폭풍과 폭풍의 안벽에 [117][118]더 가깝고 더 강렬합니다.열대성 저기압은 추가적인 [119]습기를 전달함으로써 한 지역에서 경험하는 눈의 양을 증가시킬 수 있다.산불은 가까운 폭풍이 강한 [120][121]바람으로 불길을 부채질할 때 더 심해질 수 있다.

재산과 인명에 미치는 영향

열대성 저기압은 대서양, 태평양, 그리고 인도양을 따라 있는 지구의 주요 수역의 해안선에 정기적으로 영향을 미칩니다.열대성 사이클론은 19세기 [122]이후 약 2백만 명의 사망자를 내면서 상당한 파괴와 인명 손실을 초래했다.홍수로 인한 넓은 면적의 고인 물은 모기 전염병의 원인이 될 뿐만 아니라 감염으로 이어진다.대피소에 사람이 많으면 질병 [111]전파 위험이 높아진다.열대성 저기압은 인프라를 크게 방해하여 정전, 교량 및 도로 파괴, 복구 [111][123][124]작업 방해로 이어집니다.폭풍으로 인한 바람과 물은 집, 건물, 그리고 다른 인공 [125][126]구조물들을 손상시키거나 파괴할 수 있다.열대성 사이클론은 농업을 파괴하고 가축을 죽이고 구매자와 판매자 모두에게 시장 접근을 방해한다. 이 두 가지 모두 재정적 손실을 [127][128][129]초래한다.육지에서 육지로 이동하는 강력한 사이클론은 가장 큰 영향을 미치지만 항상 그렇지는 않습니다.열대성 폭풍 강도의 열대성 사이클론은 전 세계적으로 연평균 86개가 형성되며, 47개는 허리케인 또는 태풍 강도에 도달하고, 20개는 강력한 열대성 사이클론, 슈퍼 태풍 또는 주요 허리케인이 된다(최소한 카테고리 3 강도의).[130]

아프리카에서 열대성 저기압은 사하라 [131]사막에서 발생한 열대 파도에서 발생하거나, 그렇지 않으면 아프리카의 뿔과 남아프리카를 [132][133]강타할 수 있습니다.2019년 3월 사이클론 이다이는 모잠비크 중부를 강타하여 1,302명의 사망자와 22억 달러의 [134][135]피해로 아프리카에서 가장 치명적인 열대 저기압으로 기록되었다.남아프리카의 동쪽에 위치한 레위니옹 섬은 기록상 가장 습한 열대성 사이클론을 경험한다.1980년 1월 사이클론 히아신테는 15일 동안 6,083mm(239.5인치)의 비를 내렸는데, 이는 [136][137][138]열대성 사이클론에서 기록된 최대 강우량이었다.아시아에서는 인도양과 태평양에서 온 열대성 사이클론이 정기적으로 지구상에서 가장 인구가 많은 몇몇 나라에 영향을 미친다.1970년, 당시 동파키스탄으로 알려진 방글라데시를 강타한 사이클론은 최소 30만 명의 목숨을 앗아간 6.1미터(20피트)의 폭풍 해일을 일으켰으며,[139] 이는 역사상 가장 치명적인 열대 사이클론으로 기록되었다.2019년 10월, 태풍 하기비스가 일본 혼슈 섬을 강타하여 150억 달러의 피해를 입혔으며,[140] 이는 일본에서 가장 큰 피해를 입은 태풍이다.호주에서 프랑스령 폴리네시아에 이르는 오세아니아를 구성하는 섬들은 정기적으로 열대성 [141][142][143]저기압의 영향을 받는다.인도네시아에서는 1973년 4월 플로레스 섬을 강타한 사이클론이 1,653명의 사망자를 내면서 남반구에서 [144][145]기록된 가장 치명적인 열대성 사이클론이 되었다.

대서양과 태평양 허리케인은 정기적으로 북미에 영향을 미친다.미국에서는 2005년 허리케인 카트리나와 2017년 하비가 미국 역사상 가장 큰 자연재해로 금전적 피해는 1,250억 달러로 추산된다.카트리나는 루이지애나를 강타하여 뉴올리언스 [146][147]시를 크게 파괴한 반면, 하비는 텍사스 남동부 지역에 1539mm의 60.58mm의 비가 내린 후 상당한 홍수를 일으켰는데, 이는 미국에서 [147]기록된 최대 강우량이었다.유럽은 열대성 사이클론의 영향을 거의 받지 않지만, 대륙은 열대성 사이클론으로 전환한 후 정기적으로 폭풍을 만난다.스페인에는 [148]2005년 빈스라는 열대 저기압 한 곳만, 포르투갈에는 [149]2020년 열대성 폭풍 알파라는 아열대성 저기압 한 곳만 강타했다.가끔 지중해에는 [150]열대성 사이클론이 있다.남미 북부에서는 가끔 열대성 사이클론이 발생하는데,[151][152] 1993년 8월에는 열대성 폭풍 브레트로 173명이 사망했습니다.남대서양은 일반적으로 열대성 [153]폭풍의 형성에 적합하지 않다.그러나 2004년 3월 허리케인 카타리나는 남대서양에서 기록된 [154]첫 허리케인으로 브라질 남동부를 강타했다.

환경에 미치는 영향

사이클론은 생명과 개인 재산에 막대한 피해를 주지만, 그렇지 않으면 건조한 [155]지역에 절실히 필요한 강수량을 가져올 수 있기 때문에 영향을 미치는 지역의 강수 체계에서 중요한 요소일 수 있다.비록 미국 남동부에 초점을 맞춘 한 연구는 열대성 저기압이 가뭄을 크게 [156][157][158]회복시키지 못했다고 주장했지만, 그들의 강수량은 토양 습기를 회복시킴으로써 가뭄 상태를 완화시킬 수도 있다.열대성 저기압은 따뜻하고 습한 열대 공기를 중위도와 [159]극지방으로 이동하고 [160]상승으로 인한 열염 순환을 조절함으로써 지구 열 균형을 유지하는 데 도움을 줍니다.폭풍 해일과 허리케인의 바람은 인간이 만든 구조물에 파괴적일 수 있지만, 그것들은 또한 전형적인 중요한 어류 번식 [161]지역인 해안 하구의 물을 자극한다.소금기와 맹그로브 숲과 같은 생태계는 [162][163]땅을 침식하고 식물을 파괴하는 열대성 사이클론에 의해 심각하게 손상되거나 파괴될 수 있다.열대성 사이클론은 이용 [164][165][166]가능한 영양소의 양을 늘림으로써 수역에서 해로운 조류의 번식을 일으킬 수 있다.곤충 개체수는 폭풍우가 지나간 [167]후 양과 다양성 모두에서 감소할 수 있다.열대성 저기압과 그 잔해에 관련된 강한 바람은 수천 그루의 나무를 베어서 [168]숲에 피해를 줄 수 있다.

허리케인이 바다에서 해안으로 밀려올 때, 소금은 많은 담수 지역에 유입되어 일부 서식지가 견디기엔 염분 수치를 너무 높게 올린다.어떤 것들은 소금에 대처하고 그것을 바다로 재활용할 수 있지만, 다른 것들은 여분의 지표수를 충분히 빨리 방출하지 못하거나 그것을 대체할 만큼 충분히 큰 담수원을 가지고 있지 않다.이것 때문에, 몇몇 식물과 식물들은 과도한 [169]소금 때문에 죽는다.게다가 허리케인은 상륙할 때 독소와 산을 육지에 운반할 수 있다.범람한 물은 다양한 유출로부터 독소를 흡수할 수 있고 그것이 통과하는 땅을 오염시킬 수 있다.이 독소들은 주변 환경뿐만 아니라 그 [170]지역의 사람들과 동물들에게도 해롭다.열대성 사이클론은 파이프라인과 저장 [171][164][172]시설을 손상시키거나 파괴함으로써 기름 유출을 일으킬 수 있다.마찬가지로 화학물질과 처리시설이 [172][173][174]손상되었을 때 화학물질 유출이 보고되었다.열대성 사이클론 동안 [175][176]수로는 니켈, 크롬, 수은과 같은 독성 수준의 금속으로 오염되었다.

열대성 저기압은 [177][178]육지를 만들거나 파괴하는 등 지리적으로 광범위한 영향을 미칠 수 있다.사이클론 베베는 푸나푸티 환초의 투발루 섬의 크기를 거의 20% [177][179][180]증가시켰다.허리케인 왈라카는 2018년에 [178][181]멸종 위기에 처한 하와이안 몽크 바다표범의 서식지를 파괴하고 바다거북과 [182]바닷새들을 위협했다.산사태는 열대성 사이클론 동안 자주 발생하고 풍경을 크게 바꿀 수 있다. 어떤 폭풍은 수백에서 수만 건의 [183][184][185][186]산사태를 일으킬 수 있다.폭풍은 광범위한 지역의 해안선을 침식하고 침전물을 다른 [176][187][188]곳으로 운반할 수 있다.

대답

허리케인 대응은 허리케인 후의 재해 대응이다.허리케인 대응자들이 수행하는 활동에는 건물 평가, 복구 및 철거, 잔해 및 폐기물 제거, 육상 기반 및 해양 인프라 복구, 수색 및 구조 [189]작업을 포함한 공중 보건 서비스가 포함됩니다.허리케인 대응을 위해서는 연방,[190] 부족, 주, 지방 및 민간 단체 간의 조정이 필요하다.재해지원단체인 '국가자원봉사단체'에 따르면 잠재적 대응봉사자는 기성조직에 가입해야 하며 자체 배치해서는 안 되며, 이에 따라 대응업무의 [191]위험과 스트레스를 완화하기 위한 적절한 훈련과 지원이 제공되어야 한다.

허리케인 대응자들은 많은 위험에 직면해 있다.허리케인 대응자는 저장된 화학 물질, 하수, 인골,[192][193][194] 홍수로 인한 곰팡이 증식뿐만 아니라 오래된 [193][195]건물에 존재할 수 있는 석면 및 납을 포함한 화학 및 생물학적 오염물질에 노출될 수 있다.일반적인 부상은 사다리 또는 수평면에서의 추락, 휴대용 발전기의 역류 공급을 포함한 침수 지역의 감전 또는 자동차 [192][195][196]사고에서 발생한다.길고 불규칙한 교대 근무는 수면 부족과 피로를 초래할 수 있고, 부상의 위험을 증가시킬 수 있으며, 근로자들은 외상성 사건과 관련된 정신적 스트레스를 경험할 수 있다.또한, 작업자는 고온 다습한 온도에 노출되고, 보호복과 장비를 착용하며, 신체적으로 어려운 [192][195]작업을 하기 때문에 열 스트레스가 우려됩니다.

기후학

열대성 저기압은 수천 년 동안 전 세계에서 발생해왔다.오버워시 퇴적물, 해변 능선, 일기 [3]등의 역사적 문서와 같은 대용 데이터를 사용하여 역사적 기록을 확장하기 위해 재분석과 연구가 수행되고 있다.주요 열대성 저기압은 지난 수천 [197]년 동안 허리케인 활동에 대한 통찰력을 얻기 위해 사용되었던 일부 해안 지역의 오버워시 기록과 포탄 층에 흔적을 남긴다.호주 서부의 퇴적물 기록에 따르면 기원전 [3]4천년에 강력한 열대성 사이클론이 발생했다고 한다.고고생태학적 연구에 기초한 대리 기록은 멕시코만 연안의 주요 허리케인 활동이 수세기에서 수 [198][199]천년 사이에 다양하다는 것을 밝혀냈다.957년에 강력한 태풍이 중국 남부를 강타하여 홍수로 약 [200]1만 명이 사망했다.태평양 허리케인에 대한 공식적인 기록은 [202]1949년으로 거슬러 올라가지만, 1730년 [201]스페인의 멕시코 식민지화는 "템페스타이드"를 묘사했다.남서부 인도양에서 열대성 사이클론 기록은 [203]1848년으로 거슬러 올라간다.2003년 대서양 허리케인 재분석 프로젝트는 대서양 열대성 저기압의 과거 기록을 조사 및 분석하여 [204]1886년부터 기존 데이터베이스를 확장하였다.

20세기 동안 위성사진을 이용할 수 있게 되기 전에, 이러한 시스템들 중 많은 것들이 [4]육지나 배가 우연히 마주치지 않는 한 감지되지 않았다.종종 허리케인의 위협으로 인해, 자동차 관광이 등장하기 전까지 많은 해안 지역은 주요 항구 사이에 희박한 인구를 가지고 있었다. 따라서, 해안을 강타한 허리케인의 가장 심각한 부분은 어떤 경우에는 측정되지 않았을 수 있다.선박 파괴와 원격 상륙의 복합적인 영향은 허리케인 정찰기와 위성 기상 시대 이전의 공식 기록에 있는 강력한 허리케인의 수를 심각하게 제한한다.이 기록은 강력한 허리케인의 수와 강도가 뚜렷하게 증가했음을 보여주지만, 전문가들은 초기 데이터를 [205]의심하는 것으로 간주한다.기후학자들이 열대성 사이클론의 장기적 분석을 하는 능력은 신뢰할 수 있는 역사적 데이터의 [206]양에 의해 제한된다.1940년대 중반 대서양과 서태평양 유역에서 항공기 정찰이 시작돼 실측 자료를 제공했지만 초기 비행은 하루에 [4]한두 번밖에 이뤄지지 않았다.극궤도 기상 위성은 1960년 미국 항공우주국에 의해 처음 발사되었지만 [4]1965년까지 가동될 수 없다고 선언되었다.그러나 일부 경보 센터가 이 새로운 전망 플랫폼을 활용하고 위성 신호를 폭풍의 위치와 [4]강도와 연관짓는 전문 지식을 개발하는 데는 몇 년이 걸렸다.

매년 평균 80~90개의 열대성 사이클론이 전 세계에서 형성되며, 그 중 절반 이상이 65kn(120km/h; 75mph) 이상의 허리케인 [4]강풍을 일으킨다.전 세계적으로 열대성 사이클론 활동은 높은 곳과 해수면 온도 차이가 가장 큰 늦여름에 최고조에 달합니다.하지만, 각각의 특별한 분지는 고유의 계절 패턴을 가지고 있다.세계적으로 볼 때 5월은 활동이 가장 적은 달이고, 9월은 활동이 가장 활발한 달이다.11월은 모든 열대성 사이클론 분지가 [207]제철인 유일한 달이다.북대서양에서는 6월 1일부터 11월 30일까지 뚜렷한 사이클론 시즌이 발생하며, 8월 말부터 [207]9월까지 급격히 정점을 이룬다.대서양 허리케인 시즌의 통계적 정점은 9월 10일이다.북동 태평양은 활동 기간이 더 넓지만 [208]대서양과 비슷한 기간이다.북서태평양은 연중 열대성 저기압을 보이며, 최소는 2월과 3월에, 최고는 [207]9월 초에 나타난다.북인도 분지에서는 폭풍우가 4월부터 12월까지 가장 흔하며, 5월과 [207]11월에 최고조에 달합니다.남반구에서는 열대 저기압의 해가 7월 1일에 시작되어 11월 1일부터 4월 말까지 이어지는 열대 저기압의 계절을 포함하여 연중 계속되며, 2월 중순에서 [207][10]3월 초에 절정을 이룬다.

기후 시스템의 다양한 변동 모드 중 엘니뇨-남부 발진은 열대 저기압 [209]활동에 가장 큰 영향을 미친다.대부분의 열대성 저기압은 적도에 가까운 아열대 능선의 측면에서 형성된 후, 서풍의 [210]주요 띠로 재발하기 전에 능선 축을 지나 극으로 이동한다.엘니뇨로 인해 아열대 능선의 위치가 바뀌면 선호하는 열대 저기압 트랙도 변화할 것이다.일본과 한국의 서쪽 지역은 엘니뇨와 중립 [211]해 동안 9월부터 11월까지 열대 저기압의 영향을 훨씬 적게 받는 경향이 있다.라니냐 시대에는 아열대 능선 위치와 함께 열대성 저기압의 형성이 서태평양을 가로질러 서쪽으로 이동하며, 이는 중국에 대한 상륙 위협을 증가시키고 필리핀에서 [211]훨씬 더 강렬하게 한다.대서양은 엘니뇨 [212]해 동안 이 지역을 가로지르는 수직 풍속 전단 증가로 활동이 위축된다.열대성 저기압은 대서양 자오선 모드, 준쌍대 진동, 매든-줄리안 [209][213]진동에 의해 더욱 영향을 받는다.

| 시즌 길이 및 평균 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 분지 | 계절 개시하다 | 계절 끝. | 트로피컬 사이클론 | 참조 | |

| 북대서양 | 6월 1일 | 11월 30일 | 14.4 | [214] | |

| 동태평양 | 5월 15일 | 11월 30일 | 16.6 | [214] | |

| 서태평양 | 1월 1일 | 12월 31일 | 26.0 | [214] | |

| 북인도 | 1월 1일 | 12월 31일 | 12 | [215] | |

| 남서인도 | 7월 1일 | 6월 30일 | 9.3 | [214][9] | |

| 오스트레일리아 지역 | 11월 1일 | 4월 30일 | 11.0 | [216] | |

| 남태평양 | 11월 1일 | 4월 30일 | 7.1 | [217] | |

| 합계: | 96.4 | ||||

기후변화의 영향

기후 변화는 다양한 방식으로 열대 저기압에 영향을 미칠 수 있다. 강우 및 풍속의 증가, 전체 빈도의 감소, 매우 강한 폭풍의 빈도 증가, 그리고 저기압이 최대 강도에 도달하는 극방향 확장은 인간이 초래하는 기후 [218]변화의 가능한 결과 중 하나이다.열대성 사이클론은 따뜻하고 습한 공기를 연료로 사용합니다.기후 변화가 해양 온도를 따뜻하게 하고 있기 때문에,[219] 잠재적으로 이 연료의 사용 가능한 양이 더 많을 수 있습니다.1979년과 2017년 사이에 사피르-심슨 척도에서 카테고리 3 이상의 열대성 저기압 비율이 전 세계적으로 증가했다.이러한 추세는 북대서양과 남인도양에서 가장 뚜렷했다.북태평양에서는 열대성 저기압이 차가운 물속으로 극지방으로 이동하고 있으며 이 [220]기간 동안 강도가 증가하지 않았다.2°C(3.6°F)의 온난화로 열대성 사이클론의 더 많은 비율(+13%)이 카테고리 4와 5의 [218]강도에 도달할 것으로 예상된다.2019년 연구에 따르면 기후 변화가 대서양 유역에서 열대성 사이클론의 급격한 증가 추세를 주도하고 있다.급속히 심해지는 사이클론은 예측하기 어렵기 때문에 해안 [221]지역에 추가적인 위험을 초래한다.

따뜻한 공기는 더 많은 수증기를 보유할 수 있다. 이론적으로 최대 수증기 함량은 클라우시우스-클라페이론 관계에 의해 구해진다. 클라우시우스-클라페이론 관계는 1°C(1.8°F) [222][223]온난화 시 대기 중 수증기를 7% 이상 증가시킨다.2019년 검토 논문에서 평가된 모든 모델은 미래의 강우량 [218]증가를 보여준다.추가적인 해수면 상승은 폭풍 해일의 [224][225]수위를 증가시킬 것이다.극단적인 풍파가 열대성 저기압의 변화의 결과로 증가하여 해안 [226]지역에 대한 폭풍 해일의 위험을 더욱 악화시키는 것은 타당하다.지구 [225]온난화로 인해 홍수, 폭풍 해일, 지상의 홍수(리버)의 복합 효과가 증가할 것으로 예상된다.

기후 변화가 열대성 [218]저기압의 전체 빈도에 어떤 영향을 미칠지에 대해서는 현재 합의가 이루어지지 않고 있다.대부분의 기후 모델은 향후 [226]예측에서 빈도가 감소했음을 보여줍니다.예를 들어, 9개의 고해상도 기후 모델을 비교한 2020년 논문은 남인도양과 남반구에서 주파수가 더 일반적으로 크게 감소하는 반면 북반구 열대 저기압에 [227]대한 혼합 신호를 발견했다.관측 결과, 북대서양과 중부 태평양에서는 빈도가 증가하고 남부 인도양과 서부 [229]북태평양에서는 현저한 감소와 함께 전 [228]세계 열대성 사이클론의 전체 빈도에 변화가 거의 없는 것으로 나타났다.기후 [230]변화와 관련이 있을 수 있는 열대성 저기압의 최대 강도가 발생하는 위도가 극으로 확장되었다.북태평양에서도 동쪽으로의 [224]확장이 있었을 가능성이 있다.1949년과 2016년 사이에 열대성 사이클론 이동 속도가 느려졌다.이것이 기후 변화에 어느 정도 기인할 수 있는지는 아직 불분명합니다. 기후 모델이 모두 이러한 [226]특징을 보이는 것은 아닙니다.

관찰 및 예측

관찰

강한 열대성 저기압은 위험한 해양 현상이기 때문에 특별한 관측 과제를 제기하며, 상대적으로 희박한 기상 관측소는 폭풍 발생 현장에서 거의 이용할 수 없다.일반적으로 폭풍우가 섬이나 해안 지역을 지나가고 있거나 근처에 배가 있는 경우에만 지표 관측을 할 수 있습니다.실시간 측정은 일반적으로 사이클론 주변에서 수행되며, 사이클론의 실제 강도는 평가할 수 없다.이러한 이유로,[231] 열대성 저기압의 상륙 지점에서의 강도를 평가하기 위해 이동하는 기상학자 팀이 있다.

열대성 저기압은 보통 30분에서 30분 간격으로 우주에서 보이는 적외선을 포착하는 기상 위성에 의해 추적된다.폭풍이 육지에 접근하면 지상 도플러 기상 레이더를 통해 관측할 수 있습니다.레이더는 태풍의 위치와 강도를 몇 [232]분마다 보여주면서 착륙 주변에서 중요한 역할을 한다.다른 인공위성은 GPS 신호의 섭동으로부터 정보를 제공하며, 하루에 수천 개의 스냅샷을 제공하고 대기 온도, 압력 및 [233]습기 함량을 캡처합니다.

현장 측정은 실시간으로 특수 장비를 갖춘 정찰 비행을 사이클론으로 보내 수행할 수 있습니다.대서양 유역에서는 미국 정부의 허리케인 사냥꾼들이 정기적으로 비행한다.[234]이러한 항공기는 사이클론으로 직접 날아가 직접 원격 감지 측정을 수행합니다.이 항공기는 또한 사이클론 내부에서 GPS 드롭존드를 발사한다.이 손들은 온도, 습도, 압력, 특히 비행 수준과 바다 표면 사이의 바람을 측정합니다.허리케인 관측의 새로운 시대는 2005년 허리케인 시즌 동안 소형 무인기인 에어로손드가 버지니아 동부 해안을 지날 때 열대성 폭풍 오필리아를 통해 비행하면서 시작되었다.비슷한 임무가 [235]서태평양에서도 성공적으로 완수되었다.

예측

고속 컴퓨터와 정교한 시뮬레이션 소프트웨어를 통해 기상 캐스터는 고압 및 저압 시스템의 미래 위치와 강도를 기반으로 열대성 사이클론 궤적을 예측하는 컴퓨터 모델을 제작할 수 있습니다.과학자들은 열대성 사이클론에 작용하는 힘에 대한 이해와 더불어 지구 궤도를 도는 위성과 다른 센서들의 풍부한 데이터를 결합하여 최근 수십 [236]년 동안 궤도 예측의 정확성을 높였다.그러나 과학자들은 열대성 [237]저기압의 강도를 예측하는 데 능숙하지 못하다.강도 예측의 개선 부족은 열대 시스템의 복잡성과 발달에 영향을 미치는 요인에 대한 불완전한 이해에 기인한다.새로운 열대 저기압 위치 및 예보 정보는 다양한 경보 [238][239][240][241][242]센터에서 최소 6시간마다 제공됩니다.

관련 사이클론 유형

열대성 사이클론 외에도 사이클론 유형의 스펙트럼 내에는 두 가지 등급의 사이클론이 있다.열대성 사이클론과 아열대성 사이클론으로 알려진 이러한 종류의 사이클론은 열대성 사이클론이 형성되거나 [243]소멸되는 동안 통과하는 단계가 될 수 있다.온대성 사이클론은 수평 온도차에서 에너지를 얻는 폭풍으로, 위도가 높은 곳에서 흔히 볼 수 있다.열대 저기압은 응축에 의해 방출되는 열에서 기단 사이의 온도 차이로 에너지원이 변화하면 고위도를 향해 이동하면서 온대성 저기압으로 변할 수 있다. 그러나 그 빈도는 그렇지 않지만, 온대성 저기압은 아열대 폭풍으로, 그리고 [244]그곳에서 열대성 저기압으로 변할 수 있다.우주에서 온 온대성 폭풍은 특유의 "코마 모양의" 구름 [245]패턴을 가지고 있다.열대성 저기압의 중심이 강한 바람과 높은 바다를 일으킬 [246]때 또한 위험할 수 있다.

아열대 사이클론은 열대성 사이클론과 온대성 사이클론의 특징을 가진 기상 시스템이다.그들은 적도에서 50°까지 광범위한 위도로 형성될 수 있다.아열대성 폭풍은 허리케인과 같은 강한 바람을 거의 일으키지 않지만,[247] 중심부가 따뜻해짐에 따라 자연적으로는 열대성 폭풍우가 될 수 있습니다.

「 」를 참조해 주세요.

- 2022년 열대 저기압

- 2022년 대서양 허리케인

- 2022년 태풍

- 2022년 태풍

- 2022년 북인도양 사이클론

- 2022-23년 남서인도양 사이클론

- 2022-23년 오스트레일리아 지역 사이클론

- 2022-23년 남태평양 사이클론

레퍼런스

- ^ a b "Glossary of NHC Terms". United States National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on February 16, 2021. Retrieved February 18, 2021.

- ^ "Tropical cyclone facts: What is a tropical cyclone?". United Kingdom Met Office. Archived from the original on February 2, 2021. Retrieved February 25, 2021.

- ^ a b c Nott, Jonathan (March 1, 2011). "A 6000 year tropical cyclone record from Western Australia". Quaternary Science Reviews. 30 (5): 713–722. Bibcode:2011QSRv...30..713N. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2010.12.004. ISSN 0277-3791. Archived from the original on December 21, 2020. Retrieved March 13, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Global Guide to Tropical Cyclone Forecasting: 2017 (PDF) (Report). World Meteorological Organization. April 17, 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 14, 2019. Retrieved September 6, 2020.

- ^ Studholme, Joshua; Fedorov, Alexey V.; Gulev, Sergey K.; Emanuel, Kerry; Hodges, Kevin (December 29, 2021). "Poleward expansion of tropical cyclone latitudes in warming climates". Nature Geoscience. 15: 14–28. doi:10.1038/s41561-021-00859-1. S2CID 245540084. Archived from the original on January 4, 2022. Retrieved January 4, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e RA IV Hurricane Committee. Regional Association IV Hurricane Operational Plan 2019 (PDF) (Report). World Meteorological Organization. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 2, 2019. Retrieved July 2, 2019.

- ^ a b c WMO/ESCP Typhoon Committee (March 13, 2015). Typhoon Committee Operational Manual Meteorological Component 2015 (PDF) (Report No. TCP-23). World Meteorological Organization. pp. 40–41. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 1, 2015. Retrieved March 28, 2015.

- ^ a b c WMO/ESCAP Panel on Tropical Cyclones (November 2, 2018). Tropical Cyclone Operational Plan for the Bay of Bengal and the Arabian Sea 2018 (PDF) (Report No. TCP-21). World Meteorological Organization. pp. 11–12. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 2, 2019. Retrieved July 2, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e RA I Tropical Cyclone Committee (November 9, 2012). Tropical Cyclone Operational Plan for the South-West Indian Ocean: 2012 (PDF) (Report No. TCP-12). World Meteorological Organization. pp. 11–14. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 29, 2015. Retrieved March 29, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k RA V Tropical Cyclone Committee (November 3, 2021). Tropical Cyclone Operational Plan for the South-East Indian Ocean and the Southern Pacific Ocean 2021 (PDF) (Report). World Meteorological Organization. pp. I-4–II-9 (9–21). Retrieved November 11, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Smith, Ray (1990). "What's in a Name?" (PDF). Weather and Climate. The Meteorological Society of New Zealand. 10 (1): 24–26. doi:10.2307/44279572. JSTOR 44279572. S2CID 201717866. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 29, 2014. Retrieved August 25, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Dorst, Neal M (October 23, 2012). "They Called the Wind Mahina: The History of Naming Cyclones". Hurricane Research Division, Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. p. Slides 8–72.

- ^ Office of the Federal Coordinator for Meteorological Services and Supporting Research (May 2017). National Hurricane Operations Plan (PDF) (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. pp. 26–28. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 15, 2018. Retrieved October 14, 2018.

- ^ Dunnavan, G.M.; Diercks, J.W. (1980). "An Analysis of Super Typhoon Tip (October 1979)". Monthly Weather Review. 108 (11): 1915–1923. Bibcode:1980MWRv..108.1915D. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1980)108<1915:AAOSTT>2.0.CO;2.

- ^ Pasch, Richard (October 23, 2015). "Hurricane Patricia Discussion Number 14". National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on October 25, 2015. Retrieved October 23, 2015.

Data from three center fixes by the Hurricane Hunters indicate that the intensity, based on a blend of 700 mb-flight level and SFMR-observed surface winds, is near 175 kt. This makes Patricia the strongest hurricane on record in the National Hurricane Center's area of responsibility (AOR) which includes the Atlantic and the eastern North Pacific basins.

- ^ Tory, K. J.; Dare, R. A. (October 15, 2015). "Sea Surface Temperature Thresholds for Tropical Cyclone Formation". Journal of Climate. American Meteorological Society. 28 (20): 8171. Bibcode:2015JCli...28.8171T. doi:10.1175/JCLI-D-14-00637.1. Archived from the original on April 28, 2021. Retrieved April 28, 2021.

- ^ Lavender, Sally; Hoeke, Ron; Abbs, Deborah (March 9, 2018). "The influence of sea surface temperature on the intensity and associated storm surge of tropical cyclone Yasi: a sensitivity study". Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences. Copernicus Publications. 18 (3): 795–805. Bibcode:2018NHESS..18..795L. doi:10.5194/nhess-18-795-2018. Archived from the original on April 28, 2021. Retrieved April 28, 2021.

- ^ Xu, Jing; Wang, Yuqing (April 1, 2018). "Dependence of Tropical Cyclone Intensification Rate on Sea SurfaceTemperature, Storm Intensity, and Size in the Western North Pacific". Weather and Forecasting. American Meteorological Society. 33 (2): 523–527. Bibcode:2018WtFor..33..523X. doi:10.1175/WAF-D-17-0095.1. Archived from the original on April 28, 2021. Retrieved April 28, 2021.

- ^ Brown, Daniel (April 20, 2017). "Tropical Cyclone Intensity Forecasting: Still a Challenging Proposition" (PDF). National Hurricane Center. p. 7. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 27, 2021. Retrieved April 27, 2021.

- ^ a b Chih, Cheng-Hsiang; Wu, Chun-Chieh (February 1, 2020). "Exploratory Analysis of Upper-Ocean Heat Content and Sea Surface Temperature Underlying Tropical Cyclone Rapid Intensification in the Western North Pacific". Journal of Climate. 33 (3): 1031–1033. Bibcode:2020JCli...33.1031C. doi:10.1175/JCLI-D-19-0305.1. S2CID 210249119. Archived from the original on April 27, 2021. Retrieved April 27, 2021.

- ^ Lin, I.; Goni, Gustavo; Knaff, John; Forbes, Cristina; Ali, M. (May 31, 2012). "Ocean heat content for tropical cyclone intensity forecasting and its impact on storm surge" (PDF). Journal of the International Society for the Prevention and Mitigation of Natural Hazards. Springer Science+Business Media. 66 (3): 3–4. doi:10.1007/s11069-012-0214-5. ISSN 0921-030X. S2CID 9130662. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 27, 2021. Retrieved April 27, 2021.

- ^ Hu, Jianyu; Wang, Xiao Hua (September 2016). "Progress on upwelling studies in the China seas". Reviews of Geophysics. AGU. 54 (3): 653–673. Bibcode:2016RvGeo..54..653H. doi:10.1002/2015RG000505. S2CID 132158526. Archived from the original on May 23, 2022. Retrieved May 14, 2022.

- ^ a b D'Asaro, Eric A. & Black, Peter G. (2006). "J8.4 Turbulence in the Ocean Boundary Layer Below Hurricane Dennis". University of Washington. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 30, 2012. Retrieved February 22, 2008.

- ^ Fedorov, Alexey V.; Brierley, Christopher M.; Emanuel, Kerry (February 2010). "Tropical cyclones and permanent El Niño in the early Pliocene epoch". Nature. 463 (7284): 1066–1070. Bibcode:2010Natur.463.1066F. doi:10.1038/nature08831. hdl:1721.1/63099. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 20182509. S2CID 4330367.

- ^ Stovern, Diana; Ritchie, Elizabeth. "Modeling the Effect of Vertical Wind Shear on Tropical Cyclone Size and Structure" (PDF). American Meteorological Society. pp. 1–2. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 18, 2021. Retrieved April 28, 2021.

- ^ Wingo, Matthew; Cecil, Daniel (March 1, 2010). "Effects of Vertical Wind Shear on Tropical Cyclone Precipitation". Monthly Weather Review. American Meteorological Society. 138 (3): 645–662. Bibcode:2010MWRv..138..645W. doi:10.1175/2009MWR2921.1. S2CID 73622535. Archived from the original on April 29, 2021. Retrieved April 28, 2021.

- ^ Liang, Xiuji; Li, Qingqing (March 1, 2021). "Revisiting the response of western North Pacific tropical cyclone intensity change to vertical wind shear in different directions". Atmospheric and Oceanic Science Letters. Science Direct. 14 (3): 100041. doi:10.1016/j.aosl.2021.100041.

- ^ Shi, Donglei; Ge, Xuyang; Peng, Melinda (September 2019). "Latitudinal dependence of the dry air effect on tropical cyclone development". Dynamics of Atmospheres and Oceans. Science Direct. 87: 101102. Bibcode:2019DyAtO..8701102S. doi:10.1016/j.dynatmoce.2019.101102. S2CID 202123299. Archived from the original on May 14, 2022. Retrieved May 14, 2022.

- ^ Wang, Shuai; Toumi, Ralf (June 1, 2019). "Impact of Dry Midlevel Air on the Tropical Cyclone Outer Circulation". Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences. American Meteorological Society. 76 (6): 1809–1826. Bibcode:2019JAtS...76.1809W. doi:10.1175/JAS-D-18-0302.1. hdl:10044/1/70065. S2CID 145965553. Archived from the original on May 23, 2022. Retrieved May 14, 2022.

- ^ Alland, Joshua J.; Tang, Brian H.; Corbosiero, Kristen L.; Bryan, George H. (February 24, 2021). "Combined Effects of Midlevel Dry Air and Vertical Wind Shear on Tropical Cyclone Development. Part II: Radial Ventilation". Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences. American Meteorological Society. 78 (3): 783–796. Bibcode:2021JAtS...78..783A. doi:10.1175/JAS-D-20-0055.1. S2CID 230602004. Archived from the original on May 14, 2022. Retrieved May 14, 2022.

- ^ Rappin, Eric D.; Morgan, Michael C.; Tripoli, Gregory J. (February 1, 2011). "The Impact of Outflow Environment on Tropical Cyclone Intensification and Structure". Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences. American Meteorological Society. 68 (2): 177–194. Bibcode:2011JAtS...68..177R. doi:10.1175/2009JAS2970.1. Archived from the original on May 14, 2022. Retrieved May 15, 2022.

- ^ Shi, Donglei; Chen, Guanghua (December 10, 2021). "The Implication of Outflow Structure for the Rapid Intensification of Tropical Cyclones under Vertical Wind Shear". Monthly Weather Review. American Meteorological Society. 149 (12): 4107–4127. Bibcode:2021MWRv..149.4107S. doi:10.1175/MWR-D-21-0141.1. S2CID 244001444. Archived from the original on May 14, 2022. Retrieved May 15, 2022.

- ^ Ryglicki, David R.; Doyle, James D.; Hodyss, Daniel; Cossuth, Joshua H.; Jin, Yi; Viner, Kevin C.; Schmidt, Jerome M. (August 1, 2019). "The Unexpected Rapid Intensification of Tropical Cyclones in Moderate Vertical Wind Shear. Part III: Outflow–Environment Interaction". Monthly Weather Review. American Meteorological Society. 147 (8): 2919–2940. Bibcode:2019MWRv..147.2919R. doi:10.1175/MWR-D-18-0370.1. S2CID 197485216. Archived from the original on May 14, 2022. Retrieved May 15, 2022.

- ^ Dai, Yi; Majumdar, Sharanya J.; Nolan, David S. (July 1, 2019). "The Outflow–Rainband Relationship Induced by Environmental Flow around Tropical Cyclones". Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences. American Meteorological Society. 76 (7): 1845–1863. Bibcode:2019JAtS...76.1845D. doi:10.1175/JAS-D-18-0208.1. S2CID 146062929. Archived from the original on May 14, 2022. Retrieved May 15, 2022.

- ^ Carrasco, Cristina; Landsea, Christopher; Lin, Yuh-Lang (June 1, 2014). "The Influence of Tropical Cyclone Size on Its Intensification". Weather and Forecasting. American Meteorological Society. 29 (3): 582–590. Bibcode:2014WtFor..29..582C. doi:10.1175/WAF-D-13-00092.1. S2CID 18429068. Archived from the original on May 1, 2021. Retrieved May 1, 2021.

- ^ Lander, Mark; Holland, Greg J. (October 1993). "On the interaction of tropical-cyclone-scale vortices. I: Observations". Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society. Royal Meteorological Society. 119 (514): 1347–1361. Bibcode:1993QJRMS.119.1347L. doi:10.1002/qj.49711951406. Archived from the original on June 1, 2022. Retrieved May 20, 2022.

- ^ Andersen, Theresa; Sheperd, Marshall (February 17, 2017). "Inland Tropical Cyclones and the "Brown Ocean" Concept". Hurricanes and Climate Change. Springer. pp. 117–134. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-47594-3_5. ISBN 978-3-319-47592-9. Archived from the original on May 15, 2022. Retrieved May 20, 2022.

- ^ Houze Jr., Robert A. (January 6, 2012). "Orographic effects on precipitating clouds". Reviews of Geophysics. AGU. 50 (1). Bibcode:2012RvGeo..50.1001H. doi:10.1029/2011RG000365. S2CID 46645620. Archived from the original on May 15, 2022. Retrieved May 20, 2022.

- ^ Landsea, Christopher. "AOML Climate Variability of Tropical Cyclones paper". Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. Archived from the original on October 26, 2021. Retrieved September 23, 2010.

- ^ "Madden–Julian Oscillation". UAE. Archived from the original on March 9, 2012. Retrieved September 23, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e "Tropical cyclone facts: How do tropical cyclones form?". United Kingdom Met Office. Archived from the original on February 2, 2021. Retrieved March 1, 2021.

- ^ a b Landsea, Chris. "How do tropical cyclones form?". Frequently Asked Questions. Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory, Hurricane Research Division. Archived from the original on August 27, 2009. Retrieved October 9, 2017.

- ^ Berg, Robbie. "Tropical cyclone intensity in relation to SST and moisture variability" (PDF). RSMAS (University of Miami). Archived (PDF) from the original on June 10, 2011. Retrieved September 23, 2010.

- ^ Chris Landsea (January 4, 2000). "Climate Variability table — Tropical Cyclones". Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on October 2, 2012. Retrieved October 19, 2006.

- ^ "Glossary of NHC Terms". United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on September 12, 2019. Retrieved June 2, 2019.

- ^ Oropeza, Fernando; Raga, Graciela B. (January 2015). "Rapid deepening of tropical cyclones in the northeastern Tropical Pacific: The relationship with oceanic eddies". Atmósfera. Science Direct. 28 (1): 27–42. doi:10.1016/S0187-6236(15)72157-0. Archived from the original on May 15, 2022. Retrieved May 15, 2022.

- ^ Diana Engle. "Hurricane Structure and Energetics". Data Discovery Hurricane Science Center. Archived from the original on May 27, 2008. Retrieved October 26, 2008.

- ^ Brad Reinhart; Daniel Brown (October 21, 2020). "Hurricane Epsilon Discussion Number 12". nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on March 21, 2021. Retrieved February 4, 2021.

- ^ Cappucci, Matthew (October 21, 2020). "Epsilon shatters records as it rapidly intensifies into major hurricane near Bermuda". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on December 10, 2020. Retrieved February 4, 2021.

- ^ Lam, Linda (September 4, 2019). "Why the Eastern Caribbean Sea Can Be a 'Hurricane Graveyard'". The Weather Channel. TWC Product and Technology. Archived from the original on July 4, 2021. Retrieved April 6, 2021.

- ^ Sadler, James C.; Kilonsky, Bernard J. (May 1977). The Regeneration of South China Sea Tropical Cyclones in the Bay of Bengal (PDF) (Report). Monterey, California: Naval Environmental Prediction Research Facility. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 22, 2021. Retrieved April 6, 2021 – via Defense Technical Information Center.

- ^ Chang, Chih-Pei (2004). East Asian Monsoon. World Scientific. ISBN 978-981-238-769-1. OCLC 61353183. Archived from the original on August 14, 2021. Retrieved November 22, 2020.

- ^ United States Naval Research Laboratory (September 23, 1999). "Tropical Cyclone Intensity Terminology". Tropical Cyclone Forecasters' Reference Guide. Archived from the original on July 12, 2012. Retrieved November 30, 2006.

- ^ a b c d "Anatomy and Life Cycle of a Storm: What Is the Life Cycle of a Hurricane and How Do They Move?". United States Hurricane Research Division. 2020. Archived from the original on February 17, 2021. Retrieved February 17, 2021.

- ^ a b c "Attempts to Stop a Hurricane in its Track: What Else has been Considered to Stop a Hurricane?". United States Hurricane Research Division. 2020. Archived from the original on February 17, 2021. Retrieved February 17, 2021.

- ^ Knaff, John; Longmore, Scott; DeMaria, Robert; Molenar, Debra (February 1, 2015). "Improved Tropical-Cyclone Flight-Level Wind Estimates Using RoutineInfrared Satellite Reconnaissance". Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology. American Meteorological Society. 54 (2): 464. Bibcode:2015JApMC..54..463K. doi:10.1175/JAMC-D-14-0112.1. Archived from the original on April 24, 2021. Retrieved April 23, 2021.

- ^ Knaff, John; Reed, Kevin; Chavas, Daniel (November 8, 2017). "Physical understanding of the tropical cyclone wind-pressure relationship". Nature Communications. 8 (1360): 1360. Bibcode:2017NatCo...8.1360C. doi:10.1038/s41467-017-01546-9. PMC 5678138. PMID 29118342.

- ^ a b Kueh, Mien-Tze (May 16, 2012). "Multiformity of the tropical cyclone wind–pressure relationship in the western North Pacific: discrepancies among four best-track archives". Environmental Research Letters. IOP Publishing. 7 (2): 2–6. Bibcode:2012ERL.....7b4015K. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/7/2/024015.

- ^ Meissner, Thomas; Ricciardulli, L.; Wentz, F.; Sampson, C. (April 18, 2018). "Intensity and Size of Strong Tropical Cyclones in 2017 from NASA's SMAP L-Band Radiometer". American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on April 21, 2021. Retrieved April 21, 2021.

- ^ DeMaria, Mark; Knaff, John; Zehr, Raymond (2013). Satellite-based Applications on Climate Change (PDF). Springer. pp. 152–154. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 22, 2021. Retrieved April 21, 2021.

- ^ Olander, Timothy; Veldan, Christopher (August 1, 2019). "The Advanced Dvorak Technique (ADT) for Estimating Tropical Cyclone Intensity: Update and New Capabilities". American Meteorological Society. 34 (4): 905–907. Bibcode:2019WtFor..34..905O. doi:10.1175/WAF-D-19-0007.1. Archived from the original on April 21, 2021. Retrieved April 21, 2021.

- ^ Velden, Christopher; Herndon, Derrick (July 21, 2020). "A Consensus Approach for Estimating Tropical Cyclone Intensity from Meteorological Satellites: SATCON". American Meteorological Society. 35 (4): 1645–1650. Bibcode:2020WtFor..35.1645V. doi:10.1175/WAF-D-20-0015.1. Archived from the original on April 21, 2021. Retrieved April 21, 2021.

- ^ Chen, Buo-Fu; Chen, Boyo; Lin, Hsuan-Tien; Elsberry, Russell (April 2019). "Estimating tropical cyclone intensity by satellite imagery utilizing convolutional neural networks". American Meteorological Society. 34 (2): 448. Bibcode:2019WtFor..34..447C. doi:10.1175/WAF-D-18-0136.1. Archived from the original on April 21, 2021. Retrieved April 21, 2021.

- ^ Davis, Kyle; Zeng, Xubin (February 1, 2019). "Seasonal Prediction of North Atlantic Accumulated Cyclone Energy and Major Hurricane Activity". Weather and Forecasting. American Meteorological Society. 34 (1): 221–232. Bibcode:2019WtFor..34..221D. doi:10.1175/WAF-D-18-0125.1. S2CID 128293725.

- ^ Villarini, Gabriele; Vecchi, Gabriel A (January 15, 2012). "North Atlantic Power Dissipation Index (PDI) and Accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE): Statistical Modeling and Sensitivity to Sea Surface Temperature Changes". Journal of Climate. American Meteorological Society. 25 (2): 625–637. Bibcode:2012JCli...25..625V. doi:10.1175/JCLI-D-11-00146.1.

- ^ Islam, Md. Rezuanal; Lee, Chia-Ying; Mandli, Kyle T.; Takagi, Hiroshi (August 18, 2021). "A new tropical cyclone surge index incorporating the effects of coastal geometry, bathymetry and storm information". Scientific Reports. 11 (1): 16747. Bibcode:2021NatSR..1116747I. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-95825-7. PMC 8373937. PMID 34408207.

- ^ a b Rezapour, Mehdi; Baldock, Tom E. (December 1, 2014). "Classification of Hurricane Hazards: The Importance of Rainfall". Weather and Forecasting. American Meteorological Society. 29 (6): 1319–1331. Bibcode:2014WtFor..29.1319R. doi:10.1175/WAF-D-14-00014.1.

- ^ Kozar, Michael E; Misra, Vasubandhu (February 16, 2019). "3". Hurricane Risk. Springer. pp. 43–69. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-02402-4_3. ISBN 978-3-030-02402-4. S2CID 133717045.

- ^ a b National Weather Service (October 19, 2005). "Tropical Cyclone Structure". JetStream – An Online School for Weather. National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on December 7, 2013. Retrieved May 7, 2009.

- ^ Pasch, Richard J.; Eric S. Blake; Hugh D. Cobb III; David P. Roberts (September 28, 2006). "Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Wilma: 15–25 October 2005" (PDF). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved December 14, 2006.

- ^ a b c Annamalai, H.; Slingo, J.M.; Sperber, K.R.; Hodges, K. (1999). "The Mean Evolution and Variability of the Asian Summer Monsoon: Comparison of ECMWF and NCEP–NCAR Reanalyses". Monthly Weather Review. 127 (6): 1157–1186. Bibcode:1999MWRv..127.1157A. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1999)127<1157:TMEAVO>2.0.CO;2. Archived from the original on August 1, 2020. Retrieved December 12, 2019.

- ^ American Meteorological Society. "AMS Glossary: C". Glossary of Meteorology. Allen Press. Archived from the original on January 26, 2011. Retrieved December 14, 2006.

- ^ Atlantic Oceanographic and Hurricane Research Division. "Frequently Asked Questions: What are "concentric eyewall cycles" (or "eyewall replacement cycles") and why do they cause a hurricane's maximum winds to weaken?". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on December 6, 2006. Retrieved December 14, 2006.

- ^ "Global Guide to Tropical Cyclone Forecasting: chapter 2: Tropical Cyclone Structure". Bureau of Meteorology. May 7, 2009. Archived from the original on June 1, 2011. Retrieved May 6, 2009.

- ^ a b Chavas, D.R.; Emanuel, K.A. (2010). "A QuikSCAT climatology of tropical cyclone size". Geophysical Research Letters. 37 (18): n/a. Bibcode:2010GeoRL..3718816C. doi:10.1029/2010GL044558. hdl:1721.1/64407. S2CID 16166641.

- ^ a b "Q: What is the average size of a tropical cyclone?". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. 2009. Archived from the original on October 4, 2013. Retrieved May 7, 2009.

- ^ a b Merrill, Robert T (1984). "A comparison of Large and Small Tropical cyclones". Monthly Weather Review. 112 (7): 1408–1418. Bibcode:1984MWRv..112.1408M. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1984)112<1408:ACOLAS>2.0.CO;2. hdl:10217/200. S2CID 123276607. Archived from the original on May 23, 2022. Retrieved December 12, 2019.

- ^ Dorst, Neal; Hurricane Research Division (May 29, 2009). "Frequently Asked Questions: Subject: E5) Which are the largest and smallest tropical cyclones on record?". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. Archived from the original on December 22, 2008. Retrieved June 12, 2013.

- ^ Holland, G.J. (1983). "Tropical Cyclone Motion: Environmental Interaction Plus a Beta Effect". Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences. 40 (2): 328–342. Bibcode:1983JAtS...40..328H. doi:10.1175/1520-0469(1983)040<0328:TCMEIP>2.0.CO;2. S2CID 124178238. Archived from the original on May 23, 2022. Retrieved January 10, 2020.

- ^ Dorst, Neal; Hurricane Research Division (January 26, 2010). "Subject: E6) Frequently Asked Questions: Which tropical cyclone lasted the longest?". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. Archived from the original on May 6, 2009. Retrieved June 12, 2013.

- ^ Dorst, Neal; Delgado, Sandy; Hurricane Research Division (May 20, 2011). "Frequently Asked Questions: Subject: E7) What is the farthest a tropical cyclone has travelled?". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. Archived from the original on May 6, 2009. Retrieved June 12, 2013.

- ^ a b c Galarneau, Thomas J.; Davis, Christopher A. (February 1, 2013). "Diagnosing Forecast Errors in Tropical Cyclone Motion". Monthly Weather Review. American Meteorological Society. 141 (2): 405–430. Bibcode:2013MWRv..141..405G. doi:10.1175/MWR-D-12-00071.1.

- ^ a b Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory, Hurricane Research Division. "Frequently Asked Questions: What determines the movement of tropical cyclones?". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on July 16, 2012. Retrieved July 25, 2006.

- ^ a b Wu, Chun-Chieh; Emanuel, Kerry A. (January 1, 1995). "Potential vorticity Diagnostics of Hurricane Movement. Part 1: A Case Study of Hurricane Bob (1991)". Monthly Weather Review. American Meteorological Society. 123 (1): 69–92. Bibcode:1995MWRv..123...69W. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1995)123<0069:PVDOHM>2.0.CO;2.

- ^ Carr, L. E.; Elsberry, Russell L. (February 15, 1990). "Observational Evidence for Predictions of Tropical Cyclone Propagation Relative to Environmental Steering". Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences. American Meteorological Society. 47 (4): 542–546. Bibcode:1990JAtS...47..542C. doi:10.1175/1520-0469(1990)047<0542:OEFPOT>2.0.CO;2.

- ^ a b Velden, Christopher S.; Leslie, Lance M. (June 1, 1991). "The Basic Relationship between Tropical Cyclone Intensity and the Depth of the Environmental Steering Layer in the Australian Region". Weather and Forecasting. American Meteorological Society. 6 (2): 244–253. Bibcode:1991WtFor...6..244V. doi:10.1175/1520-0434(1991)006<0244:TBRBTC>2.0.CO;2.

- ^ Chan, Johnny C.L. (January 2005). "The Physics of Tropical Cyclone Motion". Annual Review of Fluid Mechanics. Annual Reviews. 37 (1): 99–128. Bibcode:2005AnRFM..37...99C. doi:10.1146/annurev.fluid.37.061903.175702.

- ^ Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory, Hurricane Research Division. "Frequently Asked Questions: What is an easterly wave?". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on July 18, 2006. Retrieved July 25, 2006.

- ^ Avila, L.A.; Pasch, R.J. (1995). "Atlantic Tropical Systems of 1993". Monthly Weather Review. 123 (3): 887–896. Bibcode:1995MWRv..123..887A. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1995)123<0887:ATSO>2.0.CO;2.

- ^ DeCaria, Alex (2005). "Lesson 5 – Tropical Cyclones: Climatology". ESCI 344 – Tropical Meteorology. Millersville University. Archived from the original on May 7, 2008. Retrieved February 22, 2008.

- ^ Carr, Lester E.; Elsberry, Russell L. (February 1, 1995). "Monsoonal Interactions Leading to Sudden Tropical Cyclone Track Changes". Monthly Weather Review. American Meteorological Society. 123 (2): 265–290. Bibcode:1995MWRv..123..265C. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1995)123<0265:MILTST>2.0.CO;2.

- ^ a b Wang, Bin; Elsberry, Russell L.; Yuqing, Wang; Liguang, Wu (1998). "Dynamics in Tropical Cyclone Motion: A Review" (PDF). Chinese Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences. Allerton Press. 22 (4): 416–434. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 17, 2021. Retrieved April 6, 2021 – via University of Hawaii.

- ^ Holland, Greg J. (February 1, 1983). "Tropical Cyclone Motion: Environmental Interaction Plus a Beta Effect". Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences. American Meteorological Society. 40 (2): 328–342. Bibcode:1983JAtS...40..328H. doi:10.1175/1520-0469(1983)040<0328:TCMEIP>2.0.CO;2.

- ^ Fiorino, Michael; Elsberry, Russell L. (April 1, 1989). "Some Aspects of Vortex Structure Related to Tropical Cyclone Motion". Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences. American Meteorological Society. 46 (7): 975–990. Bibcode:1989JAtS...46..975F. doi:10.1175/1520-0469(1989)046<0975:SAOVSR>2.0.CO;2.

- ^ Li, Xiaofan; Wang, Bin (March 1, 1994). "Barotropic Dynamics of the Beta Gyres and Beta Drift". Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences. American Meteorological Society. 51 (5): 746–756. Bibcode:1994JAtS...51..746L. doi:10.1175/1520-0469(1994)051<0746:BDOTBG>2.0.CO;2.

- ^ Willoughby, H. E. (September 1, 1990). "Linear Normal Modes of a Moving, Shallow-Water Barotropic Vortex". Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences. American Meteorological Society. 47 (17): 2141–2148. Bibcode:1990JAtS...47.2141W. doi:10.1175/1520-0469(1990)047<2141:LNMOAM>2.0.CO;2.

- ^ Hill, Kevin A.; Lackmann, Gary M. (October 1, 2009). "Influence of Environmental Humidity on Tropical Cyclone Size". Monthly Weather Review. American Meteorological Society. 137 (10): 3294–3315. Bibcode:2009MWRv..137.3294H. doi:10.1175/2009MWR2679.1.

- ^ Sun, Yuan; Zhong, Zhong; Yi, Lan; Li, Tim; Chen, Ming; Wan, Hongchao; Wang, Yuxing; Zhong, Kai (November 27, 2015). "Dependence of the relationship between the tropical cyclone track and western Pacific subtropical high intensity on initial storm size: A numerical investigation: SENSITIVITY OF TC AND WPSH TO STORM SIZE". Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres. John Wiley & Sons. 120 (22): 11, 451–11, 467. doi:10.1002/2015JD023716.

- ^ "Fujiwhara effect describes a stormy waltz". USA Today. November 9, 2007. Archived from the original on November 5, 2012. Retrieved February 21, 2008.

- ^ "Section 2: Tropical Cyclone Motion Terminology". United States Naval Research Laboratory. April 10, 2007. Archived from the original on February 12, 2012. Retrieved May 7, 2009.

- ^ Powell, Jeff; et al. (May 2007). "Hurricane Ioke: 20–27 August 2006". 2006 Tropical Cyclones Central North Pacific. Central Pacific Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on March 6, 2016. Retrieved June 9, 2007.

- ^ "Normas Da Autoridade Marítima Para As Atividades De Meteorologia Marítima" (PDF) (in Portuguese). Brazilian Navy. 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 6, 2015. Retrieved October 5, 2018.

- ^ "Hurricane Seasonal Preparedness Digital Toolkit". Ready.gov. February 18, 2021. Archived from the original on March 21, 2021. Retrieved April 6, 2021.

- ^ Gray, Briony; Weal, Mark; Martin, David (2019). "The Role of Social Networking in Small Island Communities: Lessons from the 2017 Atlantic Hurricane Season". Proceedings of the 52nd Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences. 52nd Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences. University of Hawaii. doi:10.24251/HICSS.2019.338. ISBN 978-0-9981331-2-6.

- ^ Morrissey, Shirley A.; Reser, Joseph P. (May 1, 2003). "Evaluating the Effectiveness of Psychological Preparedness Advice in Community Cyclone Preparedness Materials". The Australian Journal of Emergency Management. 18 (2): 46–61. Archived from the original on May 23, 2022. Retrieved April 6, 2021.

- ^ "Tropical Cyclones". World Meteorological Organization. April 8, 2020. Archived from the original on April 15, 2021. Retrieved April 6, 2021.

- ^ "Fiji Meteorological Services". Ministry of Infrastructure & Meteorological Services. Ministry of Infrastructure & Transport. Archived from the original on August 14, 2021. Retrieved April 6, 2021.

- ^ "About the National Hurricane Center". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on October 12, 2020. Retrieved April 6, 2021.

- ^ Regional Association IV – Hurricane Operational Plan for NOrth America, Central America and the Caribbean (PDF). World Meteorological Organization. 2017. ISBN 9789263111630. Archived from the original on November 14, 2020. Retrieved April 6, 2021.

- ^ Roth, David & Cobb, Hugh (2001). "Eighteenth Century Virginia Hurricanes". NOAA. Archived from the original on May 1, 2013. Retrieved February 24, 2007.

- ^ a b c Shultz, J.M.; Russell, J.; Espinel, Z. (2005). "Epidemiology of Tropical Cyclones: The Dynamics of Disaster, Disease, and Development". Epidemiologic Reviews. 27: 21–35. doi:10.1093/epirev/mxi011. PMID 15958424.

- ^ Nott, Jonathan; Green, Camilla; Townsend, Ian; Callaghan, Jeffrey (July 9, 2014). "The World Record Storm Surge and the Most Intense Southern Hemisphere Tropical Cyclone: New Evidence and Modeling". Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. 5 (95): 757. Bibcode:2014BAMS...95..757N. doi:10.1175/BAMS-D-12-00233.1.

- ^ Carey, Wendy; Rogers, Spencer (April 26, 2012). "Rip Currents — Coordinating Coastal Research, Outreach and Forecast Methodologies to Improve Public Safety". Solutions to Coastal Disasters Conference 2005. American Society of Civil Engineers: 285–296. doi:10.1061/40774(176)29. ISBN 9780784407745. Archived from the original on May 26, 2022. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ Rappaport, Edward N. (September 1, 2000). "Loss of Life in the United States Associated with Recent Atlantic Tropical Cyclones". Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. American Meteorological Society. 81 (9): 2065–2074. Bibcode:2000BAMS...81.2065R. doi:10.1175/1520-0477(2000)081<2065:LOLITU>2.3.CO;2. S2CID 120065630. Archived from the original on May 26, 2022. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory, Hurricane Research Division. "Frequently Asked Questions: Are TC tornadoes weaker than midlatitude tornadoes?". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on September 14, 2009. Retrieved July 25, 2006.

- ^ Grazulis, Thomas P.; Grazulis, Doris (February 27, 2018). "Top 25 Tornado-Generating Hurricanes". The Tornado Project. St. Johnsbury, Vermont: Environmental Films. Archived from the original on December 12, 2013. Retrieved November 8, 2021.

- ^ Bovalo, C.; Barthe, C.; Yu, N.; Bègue, N. (July 16, 2014). "Lightning activity within tropical cyclones in the South West Indian Ocean". Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres. AGU. 119 (13): 8231–8244. Bibcode:2014JGRD..119.8231B. doi:10.1002/2014JD021651. S2CID 56304603. Archived from the original on May 22, 2022. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ Samsury, Christopher E.; Orville, Richard E. (August 1, 1994). "Cloud-to-Ground Lightning in Tropical Cyclones: A Study of Hurricanes Hugo (1989) and Jerry (1989)". Monthly Weather Review. American Meteorological Society. 122 (8): 1887–1896. Bibcode:1994MWRv..122.1887S. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1994)122<1887:CTGLIT>2.0.CO;2. Archived from the original on May 25, 2022. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ Collier, E.; Sauter, T.; Mölg, T.; Hardy, D. (June 10, 2019). "The Influence of Tropical Cyclones on Circulation, Moisture Transport, and Snow Accumulation at Kilimanjaro During the 2006–2007 Season". JGR Atmospheres. AGU. 124 (13): 6919–6928. Bibcode:2019JGRD..124.6919C. doi:10.1029/2019JD030682. S2CID 197581044. Archived from the original on June 1, 2022. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ Osborne, Martin; Malavelle, Florent F.; Adam, Mariana; Buxmann, Joelle; Sugier, Jaqueline; Marenco, Franco (March 20, 2019). "Saharan dust and biomass burning aerosols during ex-hurricane Ophelia: observations from the new UK lidar and sun-photometer network". Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics. Copernicus Publications. 19 (6): 3557–3578. Bibcode:2019ACP....19.3557O. doi:10.5194/acp-19-3557-2019. S2CID 208084167. Archived from the original on January 24, 2022. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ Moore, Paul (August 3, 2021). "An analysis of storm Ophelia which struck Ireland on 16 October 2017". Weather. Royal Meteorological Society. 76 (9): 301–306. Bibcode:2021Wthr...76..301M. doi:10.1002/wea.3978. S2CID 238835099. Archived from the original on June 1, 2022. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ Haque, Ubydul; Hashizume, Masahiro; Kolivras, Korine N; Overgaard, Hans J; Das, Bivash; Yamamoto, Taro (March 16, 2011). "Reduced death rates from cyclones in Bangladesh: what more needs to be done?". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. Archived from the original on October 5, 2020. Retrieved October 12, 2020.

- ^ Staff Writer (August 30, 2005). "Hurricane Katrina Situation Report #11" (PDF). Office of Electricity Delivery and Energy Reliability (OE) United States Department of Energy. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 8, 2006. Retrieved February 24, 2007.

- ^ Adam, Christopher; Bevan, David (December 2020). "Tropical cyclones and post-disaster reconstruction of public infrastructure in developing countries". Economic Modelling. Science Direct. 93: 82–99. doi:10.1016/j.econmod.2020.07.003. S2CID 224926212. Archived from the original on May 26, 2022. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ Cuny, Frederick C. (1994). Abrams, Susan (ed.). Disasters and Development (PDF). INTERTECT Press. p. 45. ISBN 0-19-503292-6. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 26, 2022. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ Le Dé, Loïc; Rey, Tony; Leone, Frederic; Gilbert, David (January 16, 2018). "Sustainable livelihoods and effectiveness of disaster responses: a case study of tropical cyclone Pam in Vanuatu". Natural Hazards. Springer. 91 (3): 1203–1221. doi:10.1007/s11069-018-3174-6. S2CID 133651688. Archived from the original on May 26, 2022. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ Perez, Eddie; Thompson, Paul (September 1995). "Natural Hazards: Causes and Effects: Lesson 5—Tropical Cyclones (Hurricanes, Typhoons, Baguios, Cordonazos, Tainos)". Prehospital and Disaster Medicine. Cambridge University Press. 10 (3): 202–217. doi:10.1017/S1049023X00042023. PMID 10155431. Archived from the original on May 26, 2022. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ Debnath, Ajay (July 2013). "Condition of Agricultural Productivity of Gosaba C.D. Block, South24 Parganas, West Bengal, India after Severe Cyclone Aila". International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications. 3 (7): 97–100. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.416.3757. ISSN 2250-3153. Archived from the original on May 26, 2022. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ Needham, Hal F.; Keim, Barry D.; Sathiaraj, David (May 19, 2015). "A review of tropical cyclone-generated storm surges: Global data sources, observations, and impacts". Reviews of Geophysics. AGU. 53 (2): 545–591. Bibcode:2015RvGeo..53..545N. doi:10.1002/2014RG000477. S2CID 129145744. Retrieved May 25, 2022.[영구 데드링크]

- ^ Landsea, Chris. "Climate Variability table — Tropical Cyclones". Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on October 2, 2012. Retrieved October 19, 2006.

- ^ Belles, Jonathan (August 28, 2018). "Why Tropical Waves Are Important During Hurricane Season". Weather.com. Archived from the original on October 1, 2020. Retrieved October 2, 2020.

- ^ Schwartz, Matthew (November 22, 2020). "Somalia's Strongest Tropical Cyclone Ever Recorded Could Drop 2 Years' Rain In 2 Days". NPR. Archived from the original on November 23, 2020. Retrieved November 23, 2020.

- ^ Muthige, M. S.; Malherbe, J.; Englebrecht, F. A.; Grab, S.; Beraki, A.; Maisha, T. R.; Van der Merwe, J. (2018). "Projected changes in tropical cyclones over the South West Indian Ocean under different extents of global warming". Environmental Research Letters. 13 (6): 065019. Bibcode:2018ERL....13f5019M. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/aabc60. S2CID 54879038. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved August 23, 2021.

- ^ Masters, Jeff. "Africa's Hurricane Katrina: Tropical Cyclone Idai Causes an Extreme Catastrophe". Weather Underground. Archived from the original on March 22, 2019. Retrieved March 23, 2019.

- ^ "Global Catastrophe Recap: First Half of 2019" (PDF). Aon Benfield. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 12, 2019. Retrieved August 12, 2019.

- ^ Lyons, Steve (February 17, 2010). "La Reunion Island's Rainfall Dynasty!". The Weather Channel. Archived from the original on February 10, 2014. Retrieved February 4, 2014.

- ^ Précipitations extrêmes (Report). Meteo France. Archived from the original on February 21, 2014. Retrieved April 15, 2013.

- ^ Randall S. Cerveny; et al. (June 2007). "Extreme Weather Records". Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. 88 (6): 856, 858. Bibcode:2007BAMS...88..853C. doi:10.1175/BAMS-88-6-853.

- ^ Frank, Neil L.; Husain, S. A. (June 1971). "The Deadliest Tropical Cyclone in history?". Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. 52 (6): 438. Bibcode:1971BAMS...52..438F. doi:10.1175/1520-0477(1971)052<0438:TDTCIH>2.0.CO;2. S2CID 123589011.

- ^ Weather, Climate & Catastrophe Insight: 2019 Annual Report (PDF) (Report). AON Benfield. January 22, 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 22, 2020. Retrieved January 23, 2020.

- ^ Sharp, Alan; Arthur, Craig; Bob Cechet; Mark Edwards (2007). Natural hazards in Australia: Identifying risk analysis requirements (PDF) (Report). Geoscience Australia. p. 45. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 31, 2020. Retrieved October 11, 2020.

- ^ The Climate of Fiji (PDF) (Information Sheet: 35). Fiji Meteorological Service. April 28, 2006. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 20, 2021. Retrieved April 29, 2021.

- ^ Republic of Fiji: Third National Communication Report to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (PDF) (Report). United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. April 27, 2020. p. 62. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 6, 2021. Retrieved August 23, 2021.

- ^ "Death toll". The Canberra Times. Australian Associated Press. June 18, 1973. Archived from the original on August 27, 2020. Retrieved April 22, 2020.

- ^ Masters, Jeff. "Africa's Hurricane Katrina: Tropical Cyclone Idai Causes an Extreme Catastrophe". Weather Underground. Archived from the original on August 4, 2019. Retrieved March 23, 2019.

- ^ "Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters". National Centers for Environmental Information. Archived from the original on August 11, 2021. Retrieved August 23, 2021.

- ^ a b Blake, Eric S.; Zelensky, David A. Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Harvey (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 26, 2018. Retrieved August 23, 2021.

- ^ Franklin, James L. (February 22, 2006). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Vince (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 14, 2011.

- ^ Blake, Eric (September 18, 2020). Subtropical Storm Alpha Discussion Number 2 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on October 9, 2020. Retrieved September 18, 2020.

- ^ Emanuel, K. (June 2005). "Genesis and maintenance of 'Mediterranean hurricanes'". Advances in Geosciences. 2: 217–220. Bibcode:2005AdG.....2..217E. doi:10.5194/adgeo-2-217-2005. Archived from the original on May 23, 2022. Retrieved May 23, 2022.

- ^ Pielke, Rubiera, Landsea, Fernández, and Klein (2003). "Hurricane Vulnerability in Latin America & The Caribbean" (PDF). National Hazards Review. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 10, 2006. Retrieved July 20, 2006.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: 여러 이름: 작성자 목록(링크) - ^ Rappaport, Ed (December 9, 1993). Tropical Storm Bret Preliminary Report (GIF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 3. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved August 11, 2015.

- ^ Landsea, Christopher W. (July 13, 2005). "Subject: Tropical Cyclone Names: G6) Why doesn't the South Atlantic Ocean experience tropical cyclones?". Tropical Cyclone Frequently Asked Question. United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Hurricane Research Division. Archived from the original on March 27, 2015. Retrieved February 7, 2015.

- ^ McTaggart-Cowan, Ron; Bosart, Lance F.; Davis, Christopher A.; Atallah, Eyad H.; Gyakum, John R.; Emanuel, Kerry A. (November 2006). "Analysis of Hurricane Catarina (2004)" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. American Meteorological Society. 134 (11): 3029–3053. Bibcode:2006MWRv..134.3029M. doi:10.1175/MWR3330.1. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 30, 2021. Retrieved May 23, 2022.

- ^ 미국 해양 대기국2005년 열대성 동북태평양 허리케인 전망.2015년 6월 12일 Wayback Machine에서 아카이브 완료.2006년 5월 2일 취득.

- ^ "Summer tropical storms don't fix drought conditions". ScienceDaily. May 27, 2015. Archived from the original on October 9, 2021. Retrieved April 10, 2021.

- ^ Yoo, Jiyoung; Kwon, Hyun-Han; So, Byung-Jin; Rajagopalan, Balaji; Kim, Tae-Woong (April 28, 2015). "Identifying the role of typhoons as drought busters in South Korea based on hidden Markov chain models: ROLE OF TYPHOONS AS DROUGHT BUSTERS". Geophysical Research Letters. 42 (8): 2797–2804. doi:10.1002/2015GL063753.

- ^ Kam, Jonghun; Sheffield, Justin; Yuan, Xing; Wood, Eric F. (May 15, 2013). "The Influence of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones on Drought over the Eastern United States (1980–2007)". Journal of Climate. American Meteorological Society. 26 (10): 3067–3086. Bibcode:2013JCli...26.3067K. doi:10.1175/JCLI-D-12-00244.1.

- ^ National Weather Service (October 19, 2005). "Tropical Cyclone Introduction". JetStream – An Online School for Weather. National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on June 14, 2012. Retrieved September 7, 2010.

- ^ Emanuel, Kerry (July 2001). "Contribution of tropical cyclones to meridional heat transport by the oceans". Journal of Geophysical Research. 106 (D14): 14771–14781. Bibcode:2001JGR...10614771E. doi:10.1029/2000JD900641.

- ^ Christopherson, Robert W. (1992). Geosystems: An Introduction to Physical Geography. New York: Macmillan Publishing Company. pp. 222–224. ISBN 978-0-02-322443-0.

- ^ Khanna, Shruti; Santos, Maria J.; Koltunov, Alexander; Shapiro, Kristen D.; Lay, Mui; Ustin, Susan L. (February 17, 2017). "Marsh Loss Due to Cumulative Impacts of Hurricane Isaac and the Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill in Louisiana". Remote Sensing. MDPI. 9 (2): 169. Bibcode:2017RemS....9..169K. doi:10.3390/rs9020169.

- ^ Osland, Michael J.; Feher, Laura C.; Anderson, Gordon H.; Varvaeke, William C.; Krauss, Ken W.; Whelan, Kevin R.T.; Balentine, Karen M.; Tiling-Range, Ginger; Smith III, Thomas J.; Cahoon, Donald R. (May 26, 2020). "A Tropical Cyclone-Induced Ecological Regime Shift: Mangrove Forest Conversion to Mudflat in Everglades National Park (Florida, USA)". Wetlands and Climate Change. Springer. 40 (5): 1445–1458. doi:10.1007/s13157-020-01291-8. S2CID 218897776. Archived from the original on May 17, 2022. Retrieved May 27, 2022.

- ^ a b You, Zai-Jin (March 18, 2019). "Tropical Cyclone-Induced Hazards Caused by Storm Surges and Large Waves on the Coast of China". Geosciences. 9 (3): 131. Bibcode:2019Geosc...9..131Y. doi:10.3390/geosciences9030131. ISSN 2076-3263.

- ^ Zang, Zhengchen; Xue, Z. George; Xu, Kehui; Bentley, Samuel J.; Chen, Qin; D'Sa, Eurico J.; Zhang, Le; Ou, Yanda (October 20, 2020). "The role of sediment-induced light attenuation on primary production during Hurricane Gustav (2008)". Biogeosciences. Copernicus Publications. 17 (20): 5043–5055. Bibcode:2020BGeo...17.5043Z. doi:10.5194/bg-17-5043-2020. S2CID 238986315. Archived from the original on January 19, 2022. Retrieved May 19, 2022.

- ^ Huang, Wenrui; Mukherjee, Debraj; Chen, Shuisen (March 2011). "Assessment of Hurricane Ivan impact on chlorophyll-a in Pensacola Bay by MODIS 250 m remote sensing". Marine Pollution Bulletin. Science Direct. 62 (3): 490–498. doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2010.12.010. PMID 21272900. Archived from the original on May 19, 2022. Retrieved May 19, 2022.

- ^ Chen, Xuan; Adams, Benjamin J.; Platt, William J.; Hooper-Bùi, Linda M. (February 28, 2020). "Effects of a tropical cyclone on salt marsh insect communities and post-cyclone reassembly processes". Ecography. Wiley Online Library. 43 (6): 834–847. doi:10.1111/ecog.04932. S2CID 212990211. Archived from the original on May 19, 2022. Retrieved May 21, 2022.

- ^ "Tempestade Leslie provoca grande destruição nas Matas Nacionais" [Storm Leslie wreaks havoc in the National Forests]. Notícias de Coimbra (in Portuguese). October 17, 2018. Archived from the original on January 28, 2019. Retrieved May 27, 2022.

- ^ Doyle, Thomas (2005). "Wind damage and Salinity Effects of Hurricanes Katrina and Rita on Coastal Baldcypress Forests of Louisiana" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved February 13, 2014.

- ^ Cappielo, Dina (2005). "Spills from hurricanes stain coast With gallery". Houston Chronicle. Archived from the original on April 25, 2014. Retrieved February 12, 2014.

- ^ Pine, John C. (2006). "Hurricane Katrina and Oil Spills: Impact on Coastal and Ocean Environments" (PDF). Oceanography. The Oceanography Society. 19 (2): 37–39. doi:10.5670/oceanog.2006.61. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 20, 2022. Retrieved May 19, 2022.

- ^ a b Santella, Nicholas; Steinberg, Laura J.; Sengul, Hatice (April 12, 2010). "Petroleum and Hazardous Material Releases from Industrial Facilities Associated with Hurricane Katrina". Risk Analysis. 30 (4): 635–649. doi:10.1111/j.1539-6924.2010.01390.x. PMID 20345576. S2CID 24147578. Archived from the original on May 21, 2022. Retrieved May 21, 2022.

- ^ Qin, Rongshui; Khakzad, Nima; Zhu, Jiping (May 2020). "An overview of the impact of Hurricane Harvey on chemical and process facilities in Texas". International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction. Science Direct. 45: 101453. doi:10.1016/j.ijdrr.2019.101453. S2CID 214418578. Archived from the original on May 17, 2022. Retrieved May 19, 2022.

- ^ Misuri, Alessio; Moreno, Valeria Casson; Quddus, Noor; Cozzani, Valerio (October 2019). "Lessons learnt from the impact of hurricane Harvey on the chemical and process industry". Reliability Engineering & System Safety. Science Direct. 190: 106521. doi:10.1016/j.ress.2019.106521. S2CID 191214528. Archived from the original on May 19, 2022. Retrieved May 19, 2022.

- ^ Cañedo, Sibely (March 29, 2019). "Tras el Huracán Willa, suben niveles de metales en río Baluarte" [After Hurricane Willa, metal levels rise in the Baluarte River] (in Spanish). Noreste. Archived from the original on September 30, 2020. Retrieved May 19, 2022.

- ^ a b Dellapenna, Timothy M.; Hoelscher, Christena; Hill, Lisa; Al Mukaimi, Mohammad E.; Knap, Anthony (December 15, 2020). "How tropical cyclone flooding caused erosion and dispersal of mercury-contaminated sediment in an urban estuary: The impact of Hurricane Harvey on Buffalo Bayou and the San Jacinto Estuary, Galveston Bay, USA". Science of the Total Environment. Science Direct. 748: 141226. Bibcode:2020ScTEn.748n1226D. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.141226. PMC 7606715. PMID 32818899.

- ^ a b Volto, Natacha; Duvat, Virginie K.E. (July 9, 2020). "Applying Directional Filters to Satellite Imagery for the Assessment of Tropical Cyclone Impacts on Atoll Islands". Coastal Research. Meridian Allen Press. 36 (4): 732–740. doi:10.2112/JCOASTRES-D-19-00153.1. S2CID 220323810. Archived from the original on January 25, 2021. Retrieved May 21, 2022.

- ^ a b Bush, Martin J. (October 9, 2019). "How to End the Climate Crisis". Climate Change and Renewable Energy. Springer. pp. 421–475. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-15424-0_9. ISBN 978-3-030-15423-3. S2CID 211444296. Archived from the original on May 17, 2022. Retrieved May 21, 2022.

- ^ Onaka, Susumu; Ichikawa, Shingo; Izumi, Masatoshi; Uda, Takaaki; Hirano, Junichi; Sawada, Hideki (2017). "Effectiveness of Gravel Beach Nourishment on Pacific Island". Asian and Pacific Coasts. World Scientific: 651–662. doi:10.1142/9789813233812_0059. ISBN 978-981-323-380-5. Archived from the original on May 16, 2022. Retrieved May 21, 2022.