병마용

Terracotta Army| 유네스코의 세계유산 | |

|---|---|

| |

| 위치 | 린퉁 구, 산시 성 시안 시 |

| 기준 | 문화: i, iii, iv, vi |

| 언급 | 441 |

| 비문 | 1987년(11기) |

| 웹사이트 | www |

| 좌표 | 34°23'06 ″ N 109°16'23 ″E / 34.38500°N 109.27306°E |

| 병마용 | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 간체 중국어 | 兵马俑 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 중국어 번체 | 兵馬俑 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 문자적 의미 | 군인과 말의 묘상 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

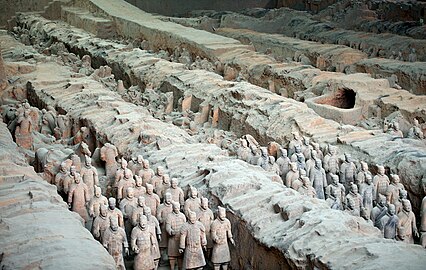

병마용은 중국의 초대 황제 진시황의 군대를 묘사한 병마용 조각 모음입니다. 이것은 기원전 210-209년에 황제의 사후 세계에서 그를 보호하기 위한 목적으로 황제와 함께 묻힌 장례 예술의 한 형태입니다.

대략 기원전 200년대 후반에 만들어진 [1]이 수치는 1974년 중국 산시성 시안 외곽 린퉁 현의 지역 농부들에 의해 발견되었습니다. 그 인물들은 계급에 따라 높이가 다른데, 가장 큰 것은 장군들입니다. 인물에는 전사, 전차, 말이 포함됩니다. 2007년의 추정에 따르면 병마용이 포함된 세 개의 구덩이에는 8,000명 이상의 병사, 520마리의 말이 탄 130대의 전차, 150마리의 기병이 들어 있으며, 대부분은 진시황의 묘 근처 구덩이에 남아 있습니다.[2] 다른 비군사적인 테라코타 인물들은 관리, 곡예사, 강자, 음악가를 포함한 다른 구덩이에서 발견되었습니다.[3]

역사

). 중앙 무덤 자체는 아직 발굴되지 않았습니다.[4]

). 중앙 무덤 자체는 아직 발굴되지 않았습니다.[4]이 무덤의 건설은 역사학자 사마천 (145–90 BCE)에 의해 묘사되었는데, 이는 중국의 24개 왕조 역사 중 첫 번째 역사이며, 무덤이 완성된 지 1세기 후에 쓰여진 것입니다. 무덤에 대한 작업은 기원전 246년에 시작되었는데, 바로 진 황제(당시 13세)가 아버지의 뒤를 이어 진왕이 된 직후였고, 그 프로젝트는 결국 70만 명의 징병 노동자들을 참여시켰습니다.[5][6] 첫 번째 황제가 죽은 지 6세기 후에 쓴 지리학자 리다오위안은 수경주에 리산이 길상한 지질 때문에 인기 있는 곳이라고 기록했습니다: "옥광산으로 유명하고, 북쪽은 금이 풍부하고, 남쪽은 아름다운 옥이 풍부하고, 첫 번째 황제는 훌륭한 명성을 탐냈습니다. 그래서 그곳에 묻히기로 했습니다."[7][8]

사마 첸(Sima Qian)은 초대 황제가 궁전, 탑, 관리들, 귀중한 공예품 및 경이로운 물건들과 함께 묻혔다고 썼습니다. 이 기록에 따르면, 흐르는 100개의 강을 수은을 이용하여 모의하고, 그 위에 천상체로 천장을 장식하고, 그 아래에 땅의 특징을 담았습니다. 이 구절의 일부 번역은 "모형" 또는 "모방"을 언급하지만, 그 단어들은 원문에서 사용되지 않았으며, 이는 또한 병마용에 대한 언급이 없습니다.[5][9] 고분의 토양에서 높은 수준의 수은이 발견되어 사마천의 설명에 신빙성을 부여했습니다.[10] 또한, 황제는 그의 재임 기간 동안 십이지 금속 거상과 같은 인간의 모습으로 기념비적인 조각상을 세운 것으로 잘 알려져 있습니다.[11][12]

후대의 역사적인 기록에 따르면, 이 단지와 무덤 자체는 초대 황제가 죽은 후 왕위를 차지하려는 경쟁자였던 샹 유에 의해 약탈되었다고 합니다.[13][14][15] 하지만 무덤 자체가 약탈당하지 않았을 수도 있다는 징후가 있습니다.[16]

디스커버리

병마용은 1974년 3월 29일 양지파와 그의 다섯 형제, 이웃 왕푸즈 등 한 무리의 농부들에 의해 발견되었으며,[17][18][19][20] 이들은 지하 샘과 수로로 가득 찬 리산(리산)의 진 황제 무덤에서 동쪽으로 약 1.5km(0.93m) 떨어진 곳에서 우물을 파던 중이었습니다. 몇 세기 동안 이따금씩 보도가 나오기도 했는데, 이는 기와, 벽돌, 석공 덩어리 등의 병마용 조각들과 진 네크로폴리스의 조각들이 언급되기도 했습니다.[21] 이 발견은 자오강민을 포함한 중국 고고학자들이 조사를 벌이게 했고,[22] 지금까지 발견된 것 중 가장 큰 도자기 조각상 그룹을 드러냈습니다. 그 이후로 박물관 단지가 이 지역에 건설되었으며, 가장 큰 구덩이는 지붕 구조로 둘러싸여 있습니다.[23]

네크로폴리스

테라코타 군대는 훨씬 더 큰 네크로폴리스의 일부입니다. 지상 침투 레이더와 코어 샘플링을 통해 약 98 평방 킬로미터(38 평방 마일)의 면적을 측정했습니다.[24]

네크로폴리스는 황제의 황궁이나 경내의 소우주로 건설되었으며,[citation needed] 초대 황제의 봉분 주변에 넓은 면적을 차지하고 있습니다. 흙무덤 봉분은 리산 기슭에 위치하고 피라미드 형태로 지어졌으며,[25] 출입구가 있는 견고하게 쌓아올린 두 개의 흙벽으로 둘러싸여 있습니다. 네크로폴리스는 여러 사무실, 홀, 마구간, 기타 구조물과 고분 주위에 배치된 황실 공원으로 구성되어 있습니다.[citation needed]

전사들은 무덤의 동쪽을 지키고 있습니다. 건설 후 2천년 동안 최대 5m(16피트)의 붉은 모래 토양이 유적지 위에 축적되었지만 고고학자들은 유적지에서 이전에 일어난 소동의 증거를 발견했습니다. 리산 봉분 근처에서 발굴 작업을 하는 동안 고고학자들은 발굴자들이 테라코타 조각을 공격한 것으로 보이는 18세기와 19세기의 무덤을 여러 개 발견했습니다. 이것들은 가치가 없는 것으로 버려지고 흙과 함께 사용되어 발굴 작업을 뒷채웠습니다.[26]

무덤

무덤은 약 100m x 75m(328피트 × 246피트) 크기로 밀폐된 공간으로 보입니다.[27][28] 이 무덤은 유물 보존에 대한 우려 때문인지 미개봉 상태로 남아 있습니다.[27] 예를 들어, 병마용 발굴 이후, 일부 병마용 모형에 존재하는 채색된 표면은 산산조각이 나고 희미해지기 시작했습니다.[29] 페인트를 덮고 있는 옻칠은 시안의 건조한 공기에 노출되면 15초 만에 말릴 수 있으며 단 4분 만에 벗겨질 수 있습니다.[30]

발굴현장

구덩이

깊이가 약 7m(23피트)인 4개의 주요 구덩이가 발굴되었습니다.[31][32] 이들은 봉분에서 동쪽으로 약 1.5km(0.93m) 떨어진 곳에 위치하고 있습니다. 안에 있던 병사들은 진나라의 정복국들이 놓여 있는 동쪽에서 무덤을 지키듯 배치되었습니다.

핏1

길이 230m(750ft), 폭 62m(203ft) 규모의 1호 피트에는 6천여 명의 주요 군대가 주둔하고 있습니다.[33][34] 피트 1에는 11개의 복도가 있으며, 대부분 폭이 3m(10ft) 이상이고 큰 보와 기둥으로 지탱되는 나무 천장이 있는 작은 벽돌로 포장되어 있습니다. 이 디자인은 귀족들의 무덤에도 사용되었고 지어졌을 때 궁전 복도와 닮았을 것입니다. 나무 천장은 방수를 위해 갈대 매트와 점토층으로 덮여 있었고, 완성되면 주변 지면에서 약 2~3m(6피트 7인치에서 9피트 10인치) 높이의 흙으로 덮여 있었습니다.[35]

다른이들

피트 2에는 기병대와 보병부대, 전차부대가 있으며, 군의 호위병을 상징하는 것으로 여겨집니다. 3번 피트는 지휘소로, 고위 장교와 전차가 있습니다. 4번 구덩이는 비어있고, 아마 건축업자들에 의해 완성되지 않은 채로 남겨져 있을 것입니다.

구덩이 1과 2에 있는 인물 중 일부는 화재 피해를 보여주고 있으며, 천장 서까래를 태운 잔해도 발견되었습니다.[36] 이것들은 사라진 무기들과 함께, 샹위에 의해 보고된 약탈과 그에 따른 부지의 불태움의 증거로 받아들여지고 있는데, 이것은 지붕이 무너지고 아래의 군대 인물들을 짓눌렀다고 생각됩니다. 현재 전시되어 있는 테라코타 모형은 파편에서 복원되었습니다.

네크로폴리스를 형성한 다른 구덩이들도 발굴되었습니다.[37] 이 구덩이들은 봉분을 둘러싼 성벽의 내부와 외부에 있습니다. 청동마차, 곡예사와 강자 등 연예인들의 테라코타 피규어, 관계자, 석기복, 말의 매장지, 희귀동물과 노동자, 지하공원을 배경으로 한 청동학과 오리 등이 다양하게 담겨 있습니다.[3]

전사 피규어

종류 및 외관

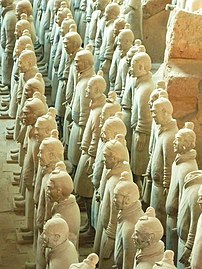

테라코타 피규어는 실제 크기이며, 일반적으로 175cm(5.74피트)에서 약 200cm(6.6피트) 사이입니다. (일반적으로 장교가 더 큽니다.). 순위에 따라 키, 유니폼, 헤어스타일이 다릅니다. 그들의 얼굴은 각 인물마다 다른 것처럼 보입니다. 그러나 학자들은 10가지 기본적인 얼굴 모양을 확인했습니다.[38] 이 인물들은 일반적인 유형입니다: 무장 보병, 무장하지 않은 보병, 필박스 모자를 쓰는 기병, 갑옷을 더 많이 보호하는 전차의 헬멧을 쓴 운전자, 창을 든 전차 운전자, 무릎을 꿇은 석궁병이나 갑옷을 입은 궁수, 그렇지 않은 서 있는 궁수, 장군과 다른 하급 장교들.[39] 그러나 등급 내 유니폼에는 많은 변형이 있습니다: 예를 들어, 어떤 사람들은 정강이 패드를 착용할 수 있지만 다른 사람들은 그렇지 않을 수 있습니다; 그들은 긴 바지와 짧은 바지 중 일부는 패딩을 입을 수 있습니다; 그리고 그들의 신체 갑옷은 등급, 기능 및 위치 정보에 따라 다릅니다.[40] 전사상 중에는 병마용도 있습니다.

원래, 이 인물들은 땅에 간 귀금속, 강하게 불에 탄 뼈(흰색), 산화철(진홍색), 신나바르(붉은색), 말라카이트(녹색), 아주라이트(파란색), 숯(검은색), 신나바르 바륨 구리 규산염 혼합물(중국 보라색 또는 한색), 인근 출처의 나무 수액으로 그려졌습니다. (중국산 옻나무일 가능성이 높음)(갈색),[41] 그리고 핑크, 라일락, 레드, 화이트,[42] 그리고 정체불명의 한 가지 색상을 포함한 다른 색상들.[41] 채색된 래커 마감과 개개인의 얼굴 생김새는 눈썹과 얼굴 털은 검은색으로, 얼굴은 분홍색으로 처리되어 있어 인물들에게 사실적인 느낌을 주었을 것입니다.[43]

그러나 시안의 건조한 기후에서는 군대를 둘러싸고 있는 진흙을 제거한 후 4분 이내에 많은 색상의 코팅이 벗겨질 것입니다.[41]

곡예사들이

1999년 피트 K9901의 발굴은 인체 해부학에 대한 진보된 이해를 보여주는 "The Acrobats"라고 불리는 일련의 관련 테라코타 조각들을 발견했습니다.[44][45] 이 조각상들의 원래 기능은 불분명하지만, 그것들은 잠재적으로 곡예사나 무용수의 모습으로 묘사되어 왔습니다. 지금까지 발견된 이 인물들의 수는 더 주목받는 전사 인물들에 비해 상대적으로 적으며, 발견된 총 수는 아마 12명에 이를 것으로 보입니다. 드레스로 허리를 묶은 것을 제외하고는 피규어가 맨손입니다. 특히 근육과 뼈 관절의 역동적인 치료를 통해 군인들보다 훨씬 생생하고 고정관념이 덜합니다.[45][44] 어떤 남자들은 매우 날씬한 반면, 다른 남자들은 육중한 몸을 가지고 있습니다. 그 중 몇 가지는 움직이거나 몸짓을 하는 과정에서 보여집니다. 이 테라코타 조각상들은 인체의 형태와 비율을 묘사하는 데 있어 진보된 숙달을 보여줍니다.[44]

가능한 영향

발견된 이후로, 그 인물들은 그들의 뛰어난 양식적 사실주의와 개인주의로 주목을 받아 왔으며, 어떤 두 인물도 정확히 같은 특징을 공유하지 않는다는 평가가 나왔습니다.[46][47] 이 측면에 대한 가장 초기의 언급은 20세기 미술사가 저먼 하프너의 것인데, 그는 1986년에 일반적인 진 시대 조각에 비해 자연주의의 특이한 전시로 인해 이 조각들과 헬레니즘적인 연관성이 있을 수 있다고 최초로 추측했습니다: "병마차 군대의 예술은 서양의 접촉에서 비롯되었고, 알렉산더 대왕에 대한 지식과 그리스 예술의 화려함에서 비롯되었습니다."[48] 이 아이디어는 또한 1998년부터 2006년까지 현장 수석 고고학자였던 Duan Qingbo와 [48]SOAS의 Lukas Nickel에 의해 일반적으로 지지되었습니다.[49] Duan Qingbo는 테라코타 군대가 기원전 1세기 후반의 중앙 아시아 칼차얀 조각상과 양식 및 기술 면에서 매우 유사하다고 언급했습니다.[50] 수석 유적 고고학자인 Li Xiuzhen도 [51]헬레니즘적 영향의 가능성을 인정하면서 "우리는 이제 병마용 군대, 곡예사, 그리고 현장에서 발견된 청동 조각들이 고대 그리스의 조각들과 예술로부터 영감을 받았다고 생각합니다"라고 말했습니다.[52] 그녀는 또한 후에 "병마용 전사들은 서양 문화에서 영감을 얻었을 수 있지만, 독특하게 중국인들에 의해 만들어졌습니다"라고 중국의 궁극적인 작가를 주장했습니다.[53]

다른 사람들은 그러한 추측들이 다른 문명들이 정교한 예술성을 가질 수 없다고 가정했던 결함이 있고 오래된 유럽 중심적인 생각들에 의존하고 있으며, 따라서 외국의 예술성은 서양의 전통을 통해 보여져야 한다고 주장했습니다.[53] 로마 무역에 관한 독립적인 연구자인 라울 맥라흘린은 병마용에 그리스의 영향은 없다고 말하며 장인 정신, 건축 재료, 그리고 상징성의 차이를 강조했습니다.[54] 다트머스 대학의 대릴 윌킨슨은 대신 페루의 콜럼버스 이전 모체 문화와 함께 진 시대의 조각적 자연주의 전시는 "그리스인들이 자연주의를 발명하지 않았다"며 "자연주의는 어떤 문화의 문명적인 '천재'의 산물이 아니다"라고 주장했습니다.[55]

시공

병마용 피규어는 정부 노동자와 지역 장인들이 현지 재료를 사용하여 작업장에서 제작되었습니다. 머리, 팔, 다리, 토소를 따로 만든 다음 조각들을 함께 루팅하여 조립했습니다. 완성되면 병마용 피규어는 계급과 의무에 따라 정확한 군사적 구성으로 구덩이에 놓였습니다.[57] 2021년 형태학적 연구에 따르면 조각상과 지역 현대 주민의 조각상 사이에는 강한 유사성이 있으며, 이로 인해 일부 학자들은 높은 수준의 양식적 사실주의가 실제 군인을 모델로 한 형상에서 비롯된다고 이론을 세웠습니다.[58][59] 얼굴은 금형을 사용하여 만들어졌으며 최소 10개의 얼굴 금형이 사용되었을 수 있습니다.[38] 그런 다음 조립 후 클레이를 추가하여 개별 얼굴 특징을 제공하여 각 도형이 다르게 보이도록 했습니다.[60] 당시 병마용 배수관이 제작된 것과 거의 같은 방식으로 무사들의 다리가 만들어졌을 것으로 추정됩니다. 이것은 피규어를 하나의 고체 조각으로 만든 다음에 발사하는 것이 아니라, 특정 부품을 발사한 후에 제조하고 조립하는 조립 라인 생산으로 공정을 분류할 것입니다. 제국의 엄격한 관리의 시기에 각 작업장은 품질 관리를 보장하기 위해 생산된 품목에 이름을 새겨야 했습니다. 이것은 현대 역사가들이 테라코타 군대를 위한 타일 및 기타 일상적인 물품을 만들기 위해 어떤 작업장에 명령을 받았는지 확인하는 데 도움이 되었습니다.

네크로폴리스 노동자들의 집단 무덤 구덩이

2003년에 노동자의 무덤 구덩이가 발견되어 발굴되었습니다. 121개의 해골이 발견되었습니다. 개체들은 대부분 15세에서 40세 사이였으며 평균 키는 약 1.7 미터였습니다. 노동자들의 기원을 이해하기 위해 유전자 연구뿐만 아니라 두개골 측정법도 만들어졌습니다. 1998년부터 2006년까지 다이묘 발굴 책임자이자 고고학자인 du칭보에 따르면, DNA 분석 결과 노동자와 노동자들은 현대 중국인들보다 더 큰 유전적 다양성을 보였다고 합니다. 현대 중국에서 "소수민족"으로 분류될 노동자의 비율과 한족 프로파일을 결합합니다.[61]

무기류

대부분의 인물들은 원래 실제 무기를 가지고 있어서 사실성을 높였을 것입니다. 이 무기들은 대부분 군대 창설 직후에 약탈당했거나 썩어버렸습니다. 그럼에도 불구하고 검, 단검, 창, 랜스, 배틀액스, 스키미타르, 방패, 석궁, 석궁 방아쇠를 포함한 40,000개 이상의 청동 무기가 회수되었습니다. 회수된 대부분의 물품은 화살촉으로 보통 100개 단위로 묶음으로 발견됩니다.[31][62][63] 이러한 화살촉에 대한 연구는 세포 생산 또는 토요티즘이라고 하는 프로세스를 사용하여 자급자족하고 자율적인 워크샵에 의해 생산되었음을 시사합니다.[64] 어떤 무기들은 묻히기 전에 10-15 마이크로미터의 이산화크롬 층으로 코팅되어 있었는데, 이것은 지난 2200년 동안 어떤 형태의 부패로부터도 그들을 보호했다고 믿어졌습니다.[65][66] 그러나 2019년 연구에 따르면 크롬은 무기를 보호하기 위한 수단이 아닌 인근 래커에서 발생한 오염에 불과했습니다. 약간 알칼리성인 pH와 매장 토양의 작은 입자 크기가 무기를 보존했을 가능성이 높습니다.[67]

칼에는 구리, 주석 및 니켈, 마그네슘 및 코발트를 포함한 기타 원소의 합금이 포함되어 있습니다.[68] 일부는 기원전 245년에서 228년 사이에 제작된 것으로 추정되는 비문을 가지고 있는데, 이 비문은 매장되기 전에 사용되었음을 나타냅니다.[69]

판례 및 유산

테라코타 군대 이전부터 알려진 인물은 극히 소수에 불과하므로 인간과 동물의 묘사는 동시대 사람들에게 극적으로 새로운 것으로 보였을 것입니다.[70] 기원전 4-3세기 주나라 말기의 희귀하고 매우 작은 병마용 조각상만이 알려져 있는데, 예를 들어 중국에서 처음으로 기병을 표현한 것으로 알려진 태르포 말사이다가 시안양(전국시대 진나라) 근처 태르포 묘지에 있는 군묘에서 발견됩니다.[71][72] 기수는 중앙아시아, 스키타이 스타일의 옷을 입고 있으며,[73] 높은 뾰족한 코는 그가 외국인임을 암시하지만,[72] 이 초기 조각상들은 진테라코타 군대의 자연주의적이고 현실적인 자질이 부족합니다.[74]

그러나 장례식 병마용은 비록 덜 엄격하고 군국주의적인 스타일이지만 후기 왕조부터 알려져 있기 때문에, 서양의 한양자완 병마용 (195 BCE) 또는 양링 병마용 (141 BCE)과 같은 훨씬 더 작은 조각상이 있습니다.[75] 진나라 황제의 인간 크기의 기념비적인 양식은 따라서 매우 짧은 기간이었고, 중국에서 기념비적인 불교 조각이 시작되면서 서기 4-6세기까지 다시 나타나지 않았습니다.[76]

과학연구

2007년, 스탠포드 대학교와 캘리포니아 버클리에 있는 첨단 광원 시설의 과학자들은 에너지 분산형 X-선 분광법과 마이크로-X-선 형광 분석을 결합한 분말 회절 실험에서 구리 규산 바륨으로 구성된 중국 보라색 염료로 채색된 테라코타 피규어를 생산하는 과정이 도교 연금술사들이 얻은 지식에서 비롯되었음을 보고했습니다. 옥 [77][78]장식을 합성하다

2006년부터 UCL 고고학 연구소의 국제적인 연구팀은 테라코타 군대의 창설에 사용된 생산 기술에 대한 더 많은 세부 사항을 알아내기 위해 분석 화학 기술을 사용해 왔습니다. 연구진은 100개씩 묶어서 묶은 청동 화살촉 4만개의 X선 형광분석법을 이용해 하나의 묶음 안에 있는 화살촉이 다른 묶음과는 다른 비교적 촘촘한 군집을 형성했다고 보고했습니다. 또한 번들 내에서도 금속 불순물의 유무가 일치했습니다. 연구진은 화살의 화학 성분을 바탕으로 자동차 산업 초기 연속 조립 라인이 아닌 현대 도요타 공장에서 사용되는 것과 유사한 셀룰러 제조 시스템을 사용했다는 결론을 내렸습니다.[79][80]

주사 전자 현미경으로 볼 수 있는 연마 및 연마 자국은 연마를 위한 선반의 가장 초기 산업적 사용에 대한 증거를 제공합니다.[79]

전시회

1982년 멜버른에 위치한 빅토리아 국립미술관(NGV)에서 중국 이외 지역의 인물들에 대한 첫 번째 전시회가 열렸습니다.[81]

영묘에서 나온 120점의 물건들과 12명의 병마용들의 수집품들이 런던 대영박물관에서 특별전 "첫 황제: 2007년 9월 13일부터 2008년 4월까지 중국 병마용.[82] 이 전시회는 2008년을 대영박물관의 가장 성공적인 해로 만들었고 2007년에서 2008년 사이에 대영박물관을 영국 최고의 문화 명소로 만들었습니다.[83][84] 이 전시회는 1972년 투탕카멘 왕전 이후 가장 많은 관람객을 박물관을 찾았습니다.[83] 사전 입장권 40만 장이 너무 빨리 매진돼 박물관 측은 자정까지 개관 시간을 연장한 것으로 알려졌습니다.[85] 타임즈에 따르면, 많은 사람들은 연장된 시간에도 불구하고 외면당해야 했습니다.[86] 중국 춘절을 기념하는 행사가 열리는 날, 박물관으로 가는 문을 닫아야 할 정도로 압사가 심했습니다.[86] 병마용은 이름만으로도 군중을 끌어 모을 수 있는 유일한 역사적 유물 세트(RMS 타이타닉 난파선 잔해와 함께)로 묘사되어 왔습니다.[85]

2004년 5월 9일에서 9월 26일 사이에 바르셀로나의 포룸 데 바르셀로나에서 열린 전시회에서 전사들과 다른 유물들이 대중에게 전시되었습니다. 그것은 그들의 가장 성공적인 전시회였습니다.[87] 2004년 10월부터 2005년 1월 사이에 마드리드의 이사벨 2세 펀다시온 운하에서 같은 전시회가 열렸는데, 이 전시회는 역대 가장 성공적이었습니다.[88] 2009년 12월부터 2010년 5월까지 이 전시회는 칠레 산티아고 데 칠레의 라 모네다 센트로 문화관에서 전시되었습니다.[89]

이 전시회는 북미를 여행하며 샌프란시스코의 아시아 미술관, 캘리포니아 산타 아나의 바우어스 미술관, 휴스턴 자연과학 박물관, 애틀랜타의 고등 미술관,[90] 워싱턴 D.C.의 내셔널 지오그래픽 협회 박물관, 토론토의 로열 온타리오 박물관 등의 박물관을 방문했습니다.[91] 그 후, 이 전시회는 스웨덴으로 건너가 2010년 8월 28일부터 2011년 1월 20일까지 극동 유물 박물관에서 개최되었습니다.[92][93] 뉴사우스웨일스 아트 갤러리에서 2010년 12월 2일부터 2011년 3월 13일까지 120점의 유물을 선보이는 '제1대 황제 – 중국의 옹립 전사'라는 제목의 전시회가 열렸습니다.[94] 2011년 2월 11일부터 6월 26일까지 몬트리올 미술관에서 영묘의 조각상을 포함한 유물을 전시하는 "중국의 전사-황제와 그의 병마용"이라는 제목의 전시회가 열렸습니다.[95] 이탈리아에서는 2008년 7월부터 11월 16일까지 토리노에서 고대유물박물관에 병마용군 전사 5명이 전시되었고,[96] 2010년 4월 16일부터 9월 5일까지 밀라노 왕궁에서 "두 제국"이라는 제목의 전시회에서 관리, 랜서, 궁수 등 9점의 동상이 전시되었습니다.[97]

2013년 3월 15일부터 11월 17일까지 베른 역사박물관에서 군인들과 관련 물품들이 전시되었습니다.[98]

"제국의 시대:"라는 제목의 전시회에서 여러 병마용 모형들이 다른 많은 물건들과 함께 전시되었습니다. 2017년 4월 3일부터 2017년 7월 16일까지 뉴욕 메트로폴리탄 미술관에서 "진·한 왕조의 중국 미술".[99][100] 미국 펜실베이니아주 필라델피아의 프랭클린 인스티튜트를 방문하기 전인 2017년 4월 8일부터 9월[101][102] 4일까지 워싱턴주 시애틀의 퍼시픽 사이언스 센터에서 10명의 테라코타 아미 피규어와 다른 공예품들을 전시한 전시회가 열렸습니다. 2017년 9월 30일부터 2018년 3월 4일까지 증강현실이 추가되어 전시될 예정입니다.[103][104]

"중국의 첫 황제와 병마용"이라는 제목의 전시회가 2018년 2월 9일부터 10월 28일까지 리버풀의 세계 박물관에서 열렸습니다.[105]

독일 프랑크푸르트 암 마인, 뮌헨, 오버호프, 베를린 (공화국 궁전), 뉘른베르크에서 2003년과 2004년 사이에 120개의 실제 크기의 테라코타 조각상 복제품 전시회가 열렸습니다.[106][107]

갤러리

참고 항목

메모들

- ^ Lu Yanchou; Zhang Jingzhao; Xie Jun; Wang Xueli (1988). "TL dating of pottery sherds and baked soil from the Xian Terracotta Army Site, Shaanxi Province, China". International Journal of Radiation Applications and Instrumentation, Part D. 14 (1–2): 283–286. doi:10.1016/1359-0189(88)90077-5.

- ^ 포털 2007, 페이지 167.

- ^ a b "Decoding the Mausoleum of Emperor Qin Shihuang". China Daily. 13 May 2010. Archived from the original on 18 December 2019. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ^ WILLIAMS, A. R. (12 October 2016). "Discoveries May Rewrite History of China's Terra-Cotta Warriors". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 28 February 2021.

- ^ a b Sima Qian – Shiji Volume 6 Archived 5 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine 《史記•秦始皇本紀》 Original text: 始皇初即位,穿治酈山,及並天下,天下徒送詣七十餘萬人,穿三泉,下銅而致槨,宮觀百官奇器珍怪徙臧滿之。令匠作機駑矢,有所穿近者輒射之。以水銀為百川江河大海,機相灌輸,上具天文,下具地理。以人魚膏為燭,度不滅者久之。二世曰:"先帝後宮非有子者,出焉不宜。" 皆令從死,死者甚眾。葬既已下,或言工匠為機,臧皆知之,臧重即泄。大事畢,已臧,閉中羨,下外羨門,盡閉工匠臧者,無複出者。樹草木以象山。 Translation: 제1황상이 즉위하자 리산에서 터파기와 준비가 시작되었습니다. 그가 그의 제국을 통일한 후, 70만 명의 사람들이 그의 제국 전역에서 그곳으로 보내졌습니다. 그들은 관의 외부 케이싱을 배치하기 위해 구리를 부어 지하 용수철까지 깊이 파고들었습니다. 백 명의 관리들을 수용하는 궁전과 전망탑이 지어졌고 보물들과 희귀한 공예품들로 가득 찼습니다. 인부들은 침입자들을 겨냥해 자동 석궁을 준비하라는 지시를 받았습니다. 수은은 백 개의 강, 양쯔강과 황하, 대바다를 모사하는 데 사용되었으며, 기계적으로 흐르게 설정되었습니다. 위에는 하늘이, 아래에는 땅의 지리적 특징이 묘사되어 있습니다. 촛불은 오랫동안 타지 않고 꺼지지 않는 것으로 계산된 "인어"의 지방으로 만들어졌습니다. 두 번째 황제는 아들이 없는 고(故) 황제의 부인들을 자유롭게 하는 것은 부적절한 처사라고 명하여 죽은 자들과 동행하도록 하였고, 많은 사람들이 사망하였습니다. 매장 후 무덤을 짓고 보물을 알고 있는 장인들이 그 비밀을 누설한다면 심각한 위반이 될 것이라는 의견이 제시되었습니다. 따라서 장례식이 끝난 후 내부 통로와 출입구를 봉쇄하고 출구를 봉쇄하여 인부와 장인들을 바로 안으로 가두었습니다. 아무도 탈출할 수 없었습니다. 그런 다음 나무와 식물을 언덕처럼 무덤 위에 심었습니다.

- ^ "Chinese terra cotta warriors had real, and very carefully made weapons". The Washington Post. 26 November 2012. Archived from the original on 19 October 2016. Retrieved 19 October 2016.

- ^ 클레멘츠 2007, 페이지 158.

- ^ Shui Jing Zhu Chapter 19 Archived 17 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine 《水經注•渭水》Original text: 秦始皇大興厚葬,營建塚壙於驪戎之山,一名藍田,其陰多金,其陽多美玉,始皇貪其美名,因而葬焉。

- ^ 포털 2007, 17페이지.

- ^ 포털 2007, 페이지 202.

- ^ Qingbo, Duan, Director of the excavation team at the First Emperor's necropolis from 1998 to 2006 (2022). "Sino-Western Cultural Exchange as Seen through the Archaeology of the First Emperor's Necropolis". Journal of Chinese History 中國歷史學刊. 7: 67–70. doi:10.1017/jch.2022.25. ISSN 2059-1632. S2CID 251690411.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 메인트: 복수 이름: 작성자 목록 (링크) CS1 메인트: 숫자 이름: 작성자 목록 (링크) - ^ Nickel, Lukas (October 2013). "The First Emperor and sculpture in China". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 76 (3): 436–450. doi:10.1017/S0041977X13000487. ISSN 0041-977X.

- ^ 수경주 19장 2012년 10월 17일 웨이백 머신 《水經注에 보관 · 渭水》 원문 : 項羽入關,發之,以三十萬人,三十日運物不能窮。關東盜賊,銷槨取銅。牧人尋羊,燒之,火延九十日,不能滅。 번역 : 샹위가 성문에 들어가 30만 명을 보냈지만 30일 만에 전리품 운반을 마치지 못했습니다. 북동쪽에서 온 도둑들이 관을 녹여서 구리를 가져갔습니다. 잃어버린 양을 찾던 양치기가 그 자리를 불태웠고, 불은 90일 동안 계속되어 꺼지지 못했습니다.

- ^ 사마천 – 시지 8권 2015년 5월 6일 웨이백 머신 《史記에 보관 · 高祖本紀》 원문 : 項羽燒秦宮室,掘始皇帝塚,私收其財物 번역 : 샹위는 진궁을 불태우고, 제1황릉을 파헤치고, 그의 소유물을 몰수했습니다.

- ^ 2015년 12월 8일 웨이백 머신 《漢書 및 楚元王傳》: 원문: "項籍焚其宮室營宇,往者咸見發掘,其後牧兒亡羊,羊入其鑿,牧者持火照球羊,失火燒其藏槨。" 번역: 샹은 궁전과 건물을 불태웠습니다. 나중에 관찰자들은 발굴된 장소를 목격했습니다. 그 후, 한 목동이 땅굴로 들어간 자신의 양을 잃었고, 그 목동은 자신의 양을 찾기 위해 횃불을 들고 있었는데, 실수로 그 곳에 불을 질러 관을 태웠습니다.

- ^ "Royal Chinese treasure discovered". BBC News. 20 October 2005. Archived from the original on 15 December 2006. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ^ Agnew, Neville (3 August 2010). Conservation of Ancient Sites on the Silk Road. Getty Publications. p. 214. ISBN 978-1606060131. Archived from the original on 29 March 2023. Retrieved 11 July 2012.

- ^ Glancey, Jonathan (12 April 2017). "The Army that Conquered the World". BBC. Archived from the original on 28 October 2019. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- ^ O. Louis Mazzatenta. "Emperor Qin's Terracotta Army". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 25 February 2017. Retrieved 22 November 2010.

- ^ 정확한 좌표는 34°23'5.71 ″ N 109°16'23.19 ″ E / 34.384919°N / 34; 109.2731083)

- ^ 클레멘츠 2007, pp. 155, 157, 158, 160–161, 166.

- ^ Ingber, Sasha (20 May 2018). "Archaeologist Who Uncovered China's 8,000-Man Terra Cotta Army Dies At 82". npr.org. Archived from the original on 21 May 2018. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- ^ "Army of Terracotta Warriors". Lonely Planet. Archived from the original on 21 August 2016. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- ^ "Discoveries May Rewrite History of China's Terra-Cotta Warriors". 12 October 2016. Archived from the original on 19 March 2019. Retrieved 12 October 2016.

- ^ 73号 Qin Ling Bei Lu (1 January 1970). "Google maps". Archived from the original on 29 May 2014. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 메인트: 숫자 이름: 작성자 목록(링크) - ^ 클레멘츠 2007, 페이지 160.

- ^ a b "The First Emperor". Channel4.com. Archived from the original on 30 September 2010. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ^ "Application of geographical methods to explore the underground palace of the Emperor Qin Shi Huang Mausoleum". Retrieved 3 December 2011.[영구 데드링크]

- ^ Nature (2003). "Terracotta Army saved from crack up". News@nature. doi:10.1038/news031124-7. Archived from the original on 13 July 2017. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ^ Larmer, Brook (June 2012). "Terra-Cotta Warriors in Color". National Geographic. p. 86. 프린트.

- ^ a b "The Necropolis of First Emperor of Qin". History.ucsb.edu. Archived from the original on 20 November 2011. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ^ Lothar Ledderose. A Magic Army for the Emperor. Archived from the original on 10 November 2013. Retrieved 15 September 2017.

- ^ ""A Magic Army for the Emperor" Lothar Ledderose, Ten Thousand Things. Moduleand Mass Production in Chinese Art, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1998, pp.51 - 73". Scribd. Archived from the original on 11 September 2021. Retrieved 1 February 2023.

- ^ "The Mausoleum of the First Emperor of the Qin Dynasty and Terracotta Warriors and Horses". China.org.cn. 12 September 2003. Archived from the original on 7 December 2013. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ^ 포털 2007.

- ^ "China unearths 114 new Terracotta Warriors". BBC News. 12 May 2010. Archived from the original on 29 March 2023. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ^ "Terracotta Accessory Pits". Travelchinaguide.com. 10 October 2009. Archived from the original on 28 September 2018. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ^ a b The Terra Cotta Warriors. p. 27. Archived from the original on 29 March 2023. Retrieved 29 March 2023.

{{cite book}}:work=무시됨(도움말) - ^ Cotterell, Maurice (June 2004). The Terracotta Warriors: The Secret Codes of the Emperor's Army. Inner Traditions Bear and Company. pp. 105–112. ISBN 978-1591430339. Archived from the original on 29 March 2023. Retrieved 29 March 2023.

- ^ Cotterell, Maurice (June 2004). The Terracotta Warriors: The Secret Codes of the Emperor's Army. Inner Traditions Bear and Company. pp. 103–105. ISBN 978-1591430339. Archived from the original on 29 March 2023. Retrieved 29 March 2023.

- ^ a b c Larmer, Brook (June 2012). "Terra-Cotta Warriors in Color". National Geographic. pp. 74–87. Archived from the original on 10 December 2019. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- ^ lie, Ma (9 September 2010). "Terracotta army emerges in its true colors". China Daily. Archived from the original on 24 January 2020. Retrieved 21 July 2019.

- ^ Imperial Tombs of China. Lithograph Publishing Company. 1995. p. 76.

- ^ a b c d Nickel, Lukas (October 2013). "The First Emperor and sculpture in China". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 76 (3): 422–427. doi:10.1017/S0041977X13000487. ISSN 0041-977X.

- ^ a b Qingbo, Duan (January 2023). "Sino-Western Cultural Exchange as Seen through the Archaeology of the First Emperor's Necropolis". Journal of Chinese History. 7 (1): 22. doi:10.1017/jch.2022.25. ISSN 2059-1632. S2CID 251690411.

Stimulated by his discovery of the terracotta entertainers at the necropolis, which display a style of sculpture unprecedented in East Asia, as well as by the internal steplike architecture embedded within the emperor's tomb mound, Duan began to explore the influence of West Asian cultures on the Qin. He published some preliminary ideas on this topic in his 2011 monograph on the necropolis, but it was most fully explored in three articles published in successive issues of his university journal, Xibei daxue xuebao, in 2015 (translated here in their entirety).

- ^ von Falkenhausen, Lothar (2008). "Action and Image in Early Chinese Art". Cahiers d'Extrême-Asie. 17: 51–91. doi:10.3406/asie.2008.1272. ISSN 0766-1177. JSTOR 44171471. Archived from the original on 30 January 2023. Retrieved 30 January 2023.

- ^ Chen, Yumin (2013). "Reflections on China's First Collection of Terracotta Acrobats (an exhibition review)". Visual Communication. 12 (4): 497–502. doi:10.1177/1470357213498175. ISSN 1470-3572. S2CID 147420437. Archived from the original on 30 January 2023. Retrieved 30 January 2023.

- ^ a b Qingbo, Duan (2022). "Sino-Western Cultural Exchange as Seen through the Archaeology of the First Emperor's Necropolis". Journal of Chinese History 中國歷史學刊. 7: 21–72. doi:10.1017/jch.2022.25. ISSN 2059-1632. S2CID 251690411.

More than thirty-five years ago [1986], there was a European scholar (German Hafner, 1911–2008) who considered that the art of the terracotta army "originated from Western contact, originated from knowledge of Alexander the Great and the splendor of Greek art." Lukas Nickel of SOAS has put forward a similar proposition.

- ^ "Early links with West likely inspiration for Terracotta Warriors, argues SOAS scholar". School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London. Archived from the original on 6 October 2017. Retrieved 28 December 2013.

- ^ Qingbo, Duan (2022). "Sino-Western Cultural Exchange as Seen through the Archaeology of the First Emperor's Necropolis". Journal of Chinese History 中國歷史學刊. 7: 21–72. doi:10.1017/jch.2022.25. ISSN 2059-1632. S2CID 251690411.

The only thing that closely matches the artistic style of the imperial Qin terracotta warriors is the head of a painted pottery figure unearthed in Uzbekistan (...) The way of assembling the head and body for this Kushan figure of a warrior (possibly Saka) was the same as that employed for the Qin terracotta warriors, in that they were fabricated separately, and then the head was inserted into the trunk of the figure.

- ^ "Dr Xiuzhen Li, School of Archaeology, University of Oxford". www.arch.ox.ac.uk.

- ^ "Western contact with China began long before Marco Polo, experts say". BBC News. 12 October 2016. Archived from the original on 16 March 2020. Retrieved 19 October 2023.

- ^ a b Hanink, Johanna; Silva, Felipe Rojas (20 November 2016). "Why China's Terracotta Warriors Are Stirring Controversy". Live Science. Archived from the original on 5 January 2020. Retrieved 5 October 2017. 원래 출판된 곳

- ^ Bulla, Patrick Michelle (October 2019). "The Qin Dynasty, the Hellenistic Empire, and the Art that May Connect Them: Why Exploring Cultural Connections Matters for Educators and Students of World History". World History Connected. 16 (3). Archived from the original on 6 June 2023. Retrieved 29 October 2023.

- ^ Wilkinson, Darryl (2022), "On the Ontological Significance of Naturalistic Art", Ancient Art Revisited, Routledge, pp. 47–66, doi:10.4324/9781003131038-3, ISBN 978-1-003-13103-8, archived from the original on 19 October 2023, retrieved 10 October 2023

- ^ "China's Terracotta Army: Exploring the Tomb Complex and Values..." Smithsonian Learning Lab. Archived from the original on 8 December 2022. Retrieved 23 October 2023.

- ^ "A Magic Army for the Emperor". Upf.edu. 1 October 1979. Archived from the original on 28 November 2011. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ^ Hu, Yungang; Wang, Jingyang; Lan, Dexing (1 May 2021). "Statistical analysis of the differences of head and face features between terracotta warriors and modern multi ethnic groups based on 3D information extraction". IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. 783 (1): 012096. Bibcode:2021E&ES..783a2096H. doi:10.1088/1755-1315/783/1/012096. ISSN 1755-1307. S2CID 235387759.

- ^ Hu, Yungang; Lan, Desheng; Wang, Jingyang; Hou, Miaole; Li, Songnian; Li, Xiuzhen; Zhu, Lei (21 March 2022). "Measurement and analysis of facial features of terracotta warriors based on high-precision 3D point clouds". Heritage Science. 10 (1): 40. doi:10.1186/s40494-022-00662-0. ISSN 2050-7445. S2CID 247572024.

- ^ 포털 2007, 페이지 170.

- ^ Qingbo, Duan (2022). "Sino-Western Cultural Exchange as Seen through the Archaeology of the First Emperor's Necropolis". Journal of Chinese History 中國歷史學刊. 7: 12. doi:10.1017/jch.2022.25. ISSN 2059-1632. S2CID 251690411.

- ^ "Exquisite Weaponry of Terra Cotta Army". Travelchinaguide.com. Archived from the original on 2 March 2020. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ^ Marcos Martinón-Torres; Xiuzhen Janice Li; Andrew Bevan; Yin Xia; Zhao Kun; Thilo Rehren (2011). "Making Weapons for the Terracotta Army". Archaeology International. 13: 65–75. doi:10.5334/ai.1316.

- ^ Pinkowski, Jennifer (26 November 2012). "Chinese terra cotta warriors had real, and very carefully made, weapons". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 19 October 2016. Retrieved 19 October 2016.

- ^ "Terracotta Warriors (Terracotta Army)". China Tour Guide. Archived from the original on 29 October 2019. Retrieved 28 July 2011.

- ^ Zhewen Luo (1993). China's imperial tombs and mausoleums. Foreign Languages Press. p. 102. ISBN 978-7-119-01619-1. Archived from the original on 29 March 2023. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ^ Martinón-Torres, Marcos; et al. (4 April 2019). "Surface chromium on Terracotta Army bronze weapons is neither an ancient anti-rust treatment nor the reason for their good preservation". Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 5289. Bibcode:2019NatSR...9.5289M. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-40613-7. PMC 6449376. PMID 30948737.

- ^ "Terracotta Warriors" (PDF). National Geographic. 2009. Retrieved 28 July 2011.[영구 데드링크]

- ^ "The First Emperor – China's Terracotta Army – Teacher's Resource Pack" (PDF). British Museum. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 December 2016. Retrieved 15 June 2017.

- ^ Nickel, Lukas (October 2013). "The First Emperor and sculpture in China". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 76 (3): 416–418. doi:10.1017/S0041977X13000487. ISSN 0041-977X.

From the centuries immediately preceding the Qin Dynasty again we know of only a few depictions of the human figure (...) figures of people and animals were very rare exceptions to the conventional imagery of the Zhou period (...) Depictions of the human figure were not a common part of the representational canon in China before the Qin Dynasty (...) In von Falkenhausen's words, "nothing in the archaeological record prepares one for the size, scale, and technically accomplished execution of the First Emperor's terracotta soldiers". For his contemporaries, the First Emperor's sculptures must have been something dramatically new.

- ^ Nickel, Lukas (October 2013). "The First Emperor and sculpture in China". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 76 (3): 416–418. doi:10.1017/S0041977X13000487. ISSN 0041-977X.

In addition, there are the statuettes of two horse riders which came to light in a late fourth-century bc tomb in Taerpo 塔兒坡, Xianyang, Shaanxi, which are believed to be the earliest depiction of riders in China....

- ^ a b Khayutina, Maria (Autumn 2013). "From wooden attendants to terracotta warriors" (PDF). Bernisches Historisches Museum the Newsletter. No.65: 2, Fig.4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 October 2023. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

Other noteworthy terracotta figurines were found in 1995 in a 4th-3rd century BCE tomb in the Taerpo cemetery near Xianyang in Shaanxi Province, where the last Qin capital of the same name was located from 350 to 207 BCE. These are the earliest representations of cavalrymen in China discovered up to this day. One of this pair can now be seen at the exhibition in Bern (Fig. 4). A small, ca. 23 cm tall, figurine represents a man sitting on a settled horse. He stretches out his left hand, whereas his right hand points downwards. Holes pierced through both his fists suggest that he originally held the reins of his horse in one hand and a weapon in the other. The rider wears a short jacket, trousers and boots – elements of the typical outfit of the inhabitants of the Central Asian steppes. Trousers were first introduced in the early Chinese state of Zhao during the late 4th century BCE, as the Chinese started to learn horse riding from their nomadic neighbours. The state of Qin should have adopted the nomadic clothes about the same time. But the figurine from Taerpo also has some other features that may point to its foreign identity: a hood-like headgear with a flat wide crown framing his face and a high, pointed nose.

또한 - ^ Qingbo, Duan (January 2023). "Sino-Western Cultural Exchange as Seen through the Archaeology of the First Emperor's Necropolis" (PDF). Journal of Chinese History. 7 (1): 26 Fig.1, 27. doi:10.1017/jch.2022.25. S2CID 251690411. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 October 2023. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

In terms of formal characteristics and style of dress and adornment, the closest parallels to the Warring States-period Qin figurines are found in the Scythian culture. Wang Hui 王輝 has examined the exchanges between the cultures of the Yellow River valley and the Scythian culture of the steppe. During a 2007 exhibition on the Scythians in Berlin, there was a bronze hood on display labeled a "Kazakh military cap." This bronze hood and the clothing of the nomads in kneeling posture [also depicted in the exhibition] are very similar in form to those of the terracotta figurines from the late Warring States Qin-period tomb at the Taerpo site (see Figure 1). The style of the Scythian bronze horse figures and the saddle, bridle, and other accessories on their bodies are nearly identical to those seen on the Warring States-period Qin figurines and a similar type of artifact from the Ordos region, and they all date to the fifth to third centuries BCE.

- ^ Nickel, Lukas (October 2013). "The First Emperor and sculpture in China". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 76 (3): 416–421. doi:10.1017/S0041977X13000487. ISSN 0041-977X.

- ^ Chong, Alan (1 January 2011). Terracotta Warriors: The First Emperor and His Legacy. Asian Civilisations Museum. Archived from the original on 21 December 2023. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ^ Qingbo, Duan. "Persian and Greek Participation in the making of China's First Empire (Video timing: 45:00-47:00)". Video of 2018 conference at UCLA. Archived from the original on 27 October 2023. Retrieved 25 October 2023.

- ^ Bertrand, Loïc; Robinet, Laurianne; Thoury, Mathieu; Janssens, Koen; Cohen, Serge X.; Schöder, Sebastian (26 November 2011). "Cultural heritage and archaeology materials studied by synchrotron spectroscopy and imaging". Applied Physics A. 106 (2): 377–396. doi:10.1007/s00339-011-6686-4. S2CID 95827070.[영구 데드링크]

- ^ Liu, Z.; Mehta, A.; Tamura, N.; Pickard, D.; Rong, B.; Zhou, T.; Pianetta, P. (November 2007). "Influence of Taoism on the invention of the purple pigment used on the Qin terracotta warriors". Journal of Archaeological Science. 34 (11): 1878–1883. Bibcode:2007JArSc..34.1878L. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.381.8552. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2007.01.005. S2CID 17797649.

- ^ a b Rees, Simon (6 March 2014). "Chemistry unearths the secrets of the Terracotta Army". Education in Chemistry. Vol. 51, no. 2. Royal Society of Chemistry. pp. 22–25. Archived from the original on 17 May 2017. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- ^ Martinón-Torres, Marcos; Li, Xiuzhen Janice; Bevan, Andrew; Xia, Yin; Zhao, Kun; Rehren, Thilo (20 October 2012). "Forty Thousand Arms for a Single Emperor: From Chemical Data to the Labor Organization Behind the Bronze Arrows of the Terracotta Army" (PDF). Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory. 21 (3): 534. doi:10.1007/s10816-012-9158-z. S2CID 163088428. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 September 2017. Retrieved 14 November 2018.

- ^ Jefferson, Dee (16 December 2018). "China's terracotta warriors will visit Melbourne for National Gallery of Victoria's Winter Masterpieces series". Arts. ABC News. Archived from the original on 8 November 2020. Retrieved 18 December 2018.

- ^ "The First Emperor: China's Terracotta Army". British Museum. Archived from the original on 11 August 2011. Retrieved 15 June 2017.

- ^ a b Higgins, Charlotte (2 July 2008). "Terracotta army makes British Museum favourite attraction". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 31 March 2019. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ "British Museum sees its most successful year ever". Best Western. 3 July 2008. Archived from the original on 11 October 2008.

- ^ a b "British Museum ponders 24-hour opening for terracotta warriors". CBC News. 22 November 2007. Archived from the original on 13 August 2016. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- ^ a b Whitworth, Damian (9 July 2008). "Is the British Museum the greatest museum on earth?". The Times. London. Archived from the original on 16 June 2011. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ DesarrolloWeb (19 April 2007). "Los guerreros de Xian, en el Forum de Barcelona". Guiarte.com. Archived from the original on 28 March 2018. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ^ "Guerreros de Xian". Futuropasado.com. Archived from the original on 19 March 2019. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ^ "Llegan a Chile los legendarios Guerreros de Terracota de China". Latercera.com. Archived from the original on 21 October 2011. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ^ "Record-Breaking Terracotta Army Exhibition at Atlanta museum". Archived from the original on 11 July 2011. Retrieved 16 January 2010.

- ^ "ROM's terracotta warriors show a blockbuster". CBC. 6 January 2011. Archived from the original on 10 January 2011. Retrieved 16 January 2011.

- ^ "China's Terracotta Army, Stockholm, Sweden, Reviews". Archived from the original on 29 March 2023. Retrieved 20 January 2010.

- ^ "World Famous Terracotta Army Arrives in Stockholm for Exhibition at Ostasiatiska Museum". Archived from the original on 22 November 2008. Retrieved 20 January 2010.

- ^ "Terracotta warriors, Picassos heading to Sydney". ABC News. 14 October 2010. Archived from the original on 12 November 2012. Retrieved 23 January 2011.

- ^ "Empereur Guerrier De Chine Et Son Armee De Terre Cuite". Mbam.qc.ca. Archived from the original on 30 September 2011. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ^ "Il Celeste Impero. Guerrieri di terracotta a Torino – Il Sole 24 ORE". Archived from the original on 21 January 2015. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- ^ "Esercito di Terracotta: dalla Cina a Palazzo Reale di Milano – NanoPress Viaggi". 9 April 2010. Archived from the original on 1 April 2019. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- ^ "Die Terrakotta-Krieger sind da". Der Bund. 22 February 2013. Archived from the original on 22 June 2015. Retrieved 21 June 2015.

- ^ 에이지 오브 엠파이어: 진·한시대 중국미술 2017년 4월 11일 웨이백 머신 메트로폴리탄 미술관에 보관

- ^ '에이지 오브 엠파이어: 진나라와 한나라의 중국 예술 (기원전 221년)–A.D. 220)' 리뷰: Wayback Machine Wall Street Journal에 보관된 국가 건설의 보물 2017년 4월 12일

- ^ Upchurch, Michael (7 April 2017). "'Terracotta Warriors' exhibit makes grand entrance at Pacific Science Center". Seattle Times. Archived from the original on 1 July 2017. Retrieved 10 July 2017.

- ^ "Terracotta Warriors of the First Emperor". Pacific Science Center. Archived from the original on 11 July 2017. Retrieved 10 July 2017.

- ^ "Why the Terracotta Warriors are so special, and how to see them in Philly". Philly.com. Archived from the original on 2 October 2017. Retrieved 3 October 2017.

- ^ Hurdle, Jon (29 September 2017). "Arming China's Terracotta Warriors – With Your Phone". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 3 October 2017. Retrieved 3 October 2017.

- ^ "World Museum, Liverpool museums". www.liverpoolmuseums.org.uk. Archived from the original on 21 December 2017. Retrieved 5 January 2018.

- ^ "Einmarsch der Chinesen". Der Tagesspiegel (in German). 16 January 2004. Archived from the original on 5 September 2019. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- ^ "Tschüss Berlin! Terrakotta-Krieger des Kaisers von China ziehen weiter". Berliner Morgenpost (in German). Deutsche Presse-Agentur. 25 July 2004. Archived from the original on 5 September 2019. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

서지학

- Clements, Jonathan (18 January 2007). The First Emperor of China. Sutton. ISBN 978-0-7509-3960-7.

- Debaine-Francfort, Corinne (1999). The Search for Ancient China. 'New Horizons' series. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-30095-4.

- Dillon, Michael (1998). China: A Historical and Cultural Dictionary. Durham East Asia series. Richmond, Surrey: Curzon. ISBN 978-0-7007-0439-2.

- Portal, Jane (2007). The First Emperor: China's Terracotta Army. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-02697-1.

- Ledderose, Lothar (2000). "A Magic Army for the Emperor". Ten Thousand Things: Module and Mass Production in Chinese Art. The A.W. Mellon Lectures in the Fine Arts. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-00957-5.

- Perkins, Dorothy (2000). Encyclopedia of China: The Essential Reference to China, Its History and Culture. Facts On File. ISBN 978-0-8160-4374-3.

외부 링크

- 유네스코 제1차 진 제국의 묘에 대한 설명

- 진시황릉 유적 박물관(공식 홈페이지)

- 병마용에 관한 인민일보 기사

- OSGF 필름스 비디오 기사: 디스커버리 타임스퀘어의 병마용

- 안소니 바르비에리 UCSB 교수의 중국 초대 황제 묘

- PBS 시리즈 '죽은 자들의 비밀'이 제작한 중국 병마용 다큐멘터리