이스라엘

Israel이스라엘의 국가 | |

|---|---|

| 국가:הַתִּקְוָה (Hatīkvāh; "The Hope") | |

짙은 녹색으로 표시된 국제적으로 인정된 국경 내의 이스라엘; 옅은 녹색으로 표시된 이스라엘 점령지 | |

| 자본의 그리고 가장 큰 도시 | 예루살렘 (한정인정)[fn 1][fn 2] 31°47'N 35°13'E / 31.783°N 35.217°E |

| 공용어 | 히브리어[8] |

| 인식언어 | 아랍어[fn 3] |

| 민족 (2023)[12] | |

| 성명서 | 이스라엘인 |

| 정부 | 단일 의회 공화국 |

• 사장님 | 아이작 헤르조그 |

• 수상 | 베냐민 네타냐후 |

• 크네세트 스피커 | 아미르 오하나 |

• 대법원장 | 우지 보겔만 (연기) |

| 입법부 | 크네세트 |

| 설립 | |

| 1948년 5월 14일 | |

• 유엔 가입 | 1949년 5월 11일 |

• 기본법 | 1958–2018 |

| 지역 | |

• 합계 | 22,072 or 20,770[13][14] km2 (8,522 or 8,019 sq mi)[a] (149th) |

• 물(%) | 2.71[15] |

| 인구. | |

• 2024년 추계 | 9,868,160[16][fn 4] (93rd) |

• 2008년 인구조사 | 7,412,200[17][fn 4] |

• 밀도 | 447/km2 (1,157.7/sq mi) (29th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2023년 견적 |

• 합계 | |

• 인당 | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2023년 견적 |

• 합계 | |

• 인당 | |

| 지니 (2018) | 34.8[fn 4][19] 중간의 |

| HDI (2022) | 매우 높음(25일) |

| 통화 | 뉴셰켈(₪)(ILS) |

| 시간대 | UTC+2:00 (IST) |

• 여름(DST) | UTC+3:00 (IDT) |

| 날짜 형식 | |

| 주행측 | 맞다 |

| 호출부호 | +972 |

| ISO 3166 코드 | IL |

| 인터넷 TLD | .일 |

공식적으로 이스라엘은 서아시아의 레반트 지역에 있는 나라입니다.[fn 5] 이 나라는 북쪽으로는 레바논, 북동쪽으로는 시리아, 동쪽으로는 요르단, 남쪽으로는 홍해, 남서쪽으로는 이집트, 서쪽으로는 지중해, 동쪽으로는 서안 지구, 남서쪽으로는 가자 지구와 접해 있습니다.[21] 텔아비브는 동예루살렘에 대한 이스라엘의 주권은 국제적으로 인정받지 못하지만, 정부의 소재지는 선포된 수도 예루살렘에 있습니다.[22][fn 6]

이스라엘은 역사적으로 가나안, 팔레스타인, 성지로 알려진 지역에 위치하고 있습니다. 고대에는 여러 가나안 민족의 본거지였고, 후에 이스라엘 민족과 유대 민족의 본거지였으며, 유대인 전통에서는 이스라엘의 땅이라고도 합니다. 그 후 이 지역은 아시리아, 바빌로니아, 아케메네스, 헬레니즘 로마 비잔틴, 아랍 통치, 이슬람 칼리프국 라시둔, 우마이야, 아바스, 십자군, 오스만 제국에 의해 지배되었습니다.19세기 후반 유럽에서 유대인의 고향을 찾는 운동인 시온주의가 부상했고, 이는 영국의 지지를 얻었습니다. 제1차 세계대전 후 오스만 제국은 패배했고 1920년 팔레스타인 위임통치령이 세워졌습니다. 팔레스타인으로의 유대인 이민이 상당히 증가하여 유대인과 아랍인 사이의 공동체 간 갈등이 발생했습니다.[24] 1947년 유엔 분할 계획은 팔레스타인 대부분의 아랍인들이 추방되고 도주하는 것을 목격한 두 그룹 사이의 내전을 촉발시켰습니다.

이스라엘은 1948년 5월 14일 영국이 위임통치령을 종료한 날 설립을 선언했습니다. 1948년 5월 15일, 이웃한 아랍 5개국의 군대가 구 의무 팔레스타인 지역을 침공하면서 제1차 아랍-이스라엘 전쟁이 시작되었습니다. 1949년 정전협정은 이스라엘의 국경이 이전 위임통치령의 대부분에 걸쳐 설정되었고, 나머지 요르단강 서안지구와 가자지구는 각각 요르단과 이집트가 지배했습니다.[25][26][27] 1967년 6일 전쟁으로 이스라엘은 요르단강 서안 지구, 가자 지구, 이집트 시나이 반도, 시리아 골란 고원을 점령했습니다. 이후 점령지 전체에 정착촌을 설립하고 지속적으로 확장하고 있으며, 국제법상 불법으로 간주되는 조치를 취했으며, 국제적으로 인정되지 않는 동예루살렘과 골란고원을 모두 합병했습니다. 1973년 욤키푸르 전쟁 이후, 이스라엘은 이집트와 평화 조약을 맺고 시나이 반도를 반환하고 요르단과 평화 조약을 체결했으며, 최근에는 몇몇 아랍 국가들과 관계를 정상화했습니다. 그러나 이스라엘-팔레스타인 분쟁 해결을 위한 노력은 성공하지 못했습니다. 팔레스타인 영토를 점령한 이스라엘의 관행은 인권단체와 유엔 관계자들로부터 팔레스타인 국민을 상대로 전쟁범죄와 반인도적 범죄를 저질렀다는 비난과 함께 국제사회의 지속적인 비난을 받았습니다.

그 나라는 비례대표제로 선출되는 의회 제도를 가지고 있습니다. 총리는 정부 수반의 역할을 하며, 이스라엘의 단일 의회인 크네세트에 의해 선출됩니다.[28] 이스라엘은 인간 개발 지수에서 매우 높은 순위를 차지하고 있으며,[29] 중동과 아시아에서 가장 부유한 국가 중 하나이며,[30][31][32] 2010년 이후 경제 협력 개발 기구 회원국입니다.[33] 중동에서 생활 수준이 가장 높은 국가 중 하나이며, 2023년[update] 현재 인구가 거의 1천만 명에 [34][35][36]달하는 가장 선진적이고 기술적인 국가 중 하나로 평가되었습니다.[37] 명목 GDP로는 세계 29위, 1인당 명목 GDP로는 18위의 경제 대국입니다.[18]

어원

영국 위임통치령 (1920–1948) 아래, 이 지역 전체는 '팔레스타인'으로 알려졌습니다.[38] 1948년 이스라엘이 수립되자, 이스라엘은 공식적으로 '이스라엘 국가'라는 이름을 채택했습니다(히브루어: מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, 메드 ī낫 메디 ˈ낫 지스 ʁ ˈʔ엘]). 아랍어: دَوْلَة إِسْرَائِيل, 다울트라 이스라 ʼī, [다울트라 ʔ ː]는 '이스라엘의 땅'(에레츠 이스라엘), 에버(에베르 조상 출신), 시온, 유대를 포함한 다른 제안된 이름들이 고려되었지만 거부되었고, '이스라엘'이라는 이름은 벤구리온에 의해 제안되었고, 6대 3의 투표로 통과되었습니다. 설립 후 초기 몇 주 동안, 정부는 이스라엘 국가의 시민을 나타내기 위해 "이스라엘"이라는 용어를 선택했습니다.[41]

이스라엘 땅과 이스라엘 어린이라는 이름은 역사적으로 각각 성경 속 이스라엘 왕국과 유대 민족 전체를 지칭하는 데 사용되었습니다.[42] '이스라엘'이라는 이름(히브리어: ī 스라 ʾē; 셉투아긴트 그리스어: ἰ σρα ήλ, 이스라엘 ē, '엘(하나님)은 지속/규칙'을 유지하지만, 호서 12장 4절 이후에는 종종 '하나님과의 투쟁'으로 해석되기도 한다)는 히브리어 성경에 따르면 주님의 천사와 성공적으로 씨름한 후 이름이 붙여진 가장 야곱을 가리킵니다. "이스라엘"이라는 단어를 집합체로 언급한 가장 초기의 고고학 유물은 고대 이집트의 메르넵타 석비(기원전 13세기 후반)입니다.[44]

역사

호미닌이 아프리카를 벗어나 이스라엘이 위치한 레반트 지역으로 초기 확장된 것은 우베이디야 선사시대 유적지에서 발견된 흔적을 바탕으로 최소 150만 년 전으로 거슬러 올라가는 반면,[45] 12만 년 전으로 거슬러 올라가는 스크훌 호미닌과 카프제 호미닌은 아프리카 이외 지역에서 해부학적으로 현대 인류의 초기 흔적 중 일부입니다.[46] 나투피아 문화는 기원전 10천년까지 남부 레반트에서 나타났고,[47] 그 뒤를 이어 기원전 4,500년경에 가술리아 문화가 나타났습니다.[48]

청동기시대와 철기시대

"카나아인"과 "카나아인"에 대한 초기 언급은 근동 및 이집트 문헌(c. 2000 BCE)에 나타나는데, 이들 인구는 정치적으로 독립적이고 영토에 기반을 둔 도시 국가로 구조화되었습니다.[49][50] 후기 청동기 시대 (1550–1200 BCE) 동안 가나안의 많은 부분은 이집트의 새로운 왕국에 경의를 표하는 봉건 국가를 형성했습니다.[51] 후기 청동기 시대의 붕괴로 가나안은 혼란에 빠졌고, 이집트의 이 지역에 대한 통제권은 무너졌습니다.[52][53]

기원전 1200년경의 고대 이집트 비문인 메르넵타 석비에 이스라엘이라는 이름의 사람이 처음으로 등장합니다.[54][55][fn 7][57] 이스라엘 민족의 조상들은 이 지역에 토착민인 고대 셈족들을 포함한 것으로 생각됩니다.[58]: 78–79 현대 고고학적 기록에 따르면 이스라엘 민족과 그들의 문화는 야훼를 중심으로 한 독특한 단일 민족, 그리고 나중에 단일 종교의 발전을 통해 가나안 민족으로부터 분기되었다고 합니다.[59][60][61] 그들은 성서의 히브리어로 알려진 히브리어의 고대 형태를 사용했습니다.[62] 비슷한 시기에 블레셋 사람들은 남쪽 해안 평야에 정착했습니다.[63][64]

현대 고고학은 토라서의 총대주교, 출애굽기, 여호수아서의 정복 이야기에 관한 서사의 역사성을 상당 부분 폐기하고, 대신 서사를 이스라엘 민족의 국가 신화로 보고 있습니다.[65] 그러나 이러한 전통의 일부 요소는 역사적 뿌리를 가지고 있는 것으로 보입니다.[66][67][68]

이스라엘과 유다 왕국의 가장 초기의 존재와 그 범위와 힘에 대한 논쟁이 있습니다. 연합 이스라엘 왕국이 존재했는지는 불분명하지만,[69][70] 역사가들과 고고학자들은 북부 이스라엘 왕국은 기원전[71]: 169–195 [72] 900년까지, 유다 왕국은 기원전 850년까지 존재했다고 동의합니다.[73][74] 이스라엘 왕국은 두 나라 중에서 더 번영했고 곧 지역 강국으로 발전했습니다.[75] 오므라이드 왕조 동안 사마리아, 갈릴리, 요르단 강 상류, 샤론 강과 트란스요르단 강 일대를 지배했습니다.[76] 수도 사마리아는 레반트에서 가장 큰 철기 시대 건축물 중 하나의 본거지였습니다.[77][78]

이스라엘 왕국은 기원전 720년경 네오아시리아 제국에 의해 정복되었을 때 파괴되었습니다.[79] 예루살렘에 수도를 둔 유다 왕국은 나중에 처음에는 신아시리아 제국, 그 다음에는 신바빌로니아 제국의 고객 국가가 되었습니다. 이 지역의 인구는 철기 2세 때 약 40만 명이었던 것으로 추정됩니다.[80] 기원전 587/6년 유다에서 반란이 일어난 후, 네부카드네자르 2세는 예루살렘과 솔로몬 신전을 포위하고 파괴하였으며,[81][82] 왕국을 해체하고 유대인 엘리트들의 많은 부분을 바빌론으로 추방하여 바빌론의 포로 생활을 시작했습니다.[83] 패배는 바빌로니아 연대기에 기록되어 있습니다.[84][85] 기원전 539년 바빌론을 점령한 후, 아케메네스 제국의 창시자 키루스 대왕은 추방당한 유대인들을 유다로 돌려보내는 포고령을 발표했습니다.[86][87]

고전고전

기원전 520년에 제2 사원의 건설이 완료되었습니다.[86] 아케메네스족은 이 지역을 기원전 5세기에서 4세기 사이에 약 3만 명의 인구를 가진 예후드 메디나타 지방으로 통치했습니다.[88][71]: 308

기원전 332년, 마케도니아의 알렉산더 대왕은 아케메네스 제국에 대항한 그의 캠페인의 일환으로 이 지역을 정복했습니다. 그가 죽은 후, 이 지역은 코엘-시리아의 일부로서 프톨레마이오스 제국과 셀레우코스 제국에 의해 지배되었습니다. 이후 수세기 동안 이 지역의 헬레니즘화는 안티오코스 4세의 통치 기간 동안 문화적 긴장으로 이어졌고, 기원전 167년 마카베오 반란을 일으켰습니다. 내전으로 인해 셀레우코스의 통치가 약화되었고, 2세기 후반에 반자치 하스모네인 유대 왕국이 생겨나면서 결국 완전한 독립을 이루었고, 인근 지역으로 확장되었습니다.[89][90][91]

로마 공화국은 기원전 63년에 이 지역을 침공하여 먼저 시리아를 장악한 다음 하스모네 내전에 개입했습니다. 유대에서 친로마파와 친 파르티아파 사이의 투쟁으로 헤롯대왕이 로마의 왕조적 봉신으로 세워지게 되었습니다. 서기 6년에 이 지역은 로마의 유대 속주로 합병되었고, 로마의 통치와의 긴장은 유대-로마 전쟁의 연속으로 이어져 광범위한 파괴를 초래했습니다. 제1차 유대-로마 전쟁(서기 66년–73년)으로 예루살렘과 제2성전이 파괴되었고 인구의 상당 부분이 죽거나 쫓겨났습니다.[92]

서기 132년에서 136년 사이에 바르 코흐바 반란으로 알려진 두 번째 봉기가 일어났습니다. 초기의 성공으로 유대인들은 독립국가를 만들 수 있었지만, 로마인들은 대규모 병력을 동원하여 반란을 잔인하게 진압하여 유대인들의 시골을 황폐화시키고 인구를 줄였습니다.[92][93][94][95][96] 예루살렘은 로마의 식민지(알리아 카피톨리나)로 재건되었고, 유대 지방은 시리아 팔레스티나로 개명되었습니다.[97][98] 유대인들은 예루살렘을 둘러싼 지역에서 추방되었고,[99][95] 디아스포라의 공동체에 합류했습니다.[100] 그럼에도 불구하고 유대인들은 계속적으로 작은 존재였고 갈릴리는 그 종교의 중심지가 되었습니다.[101][102] 유대인 공동체는 또한 남부 헤브론 언덕과 해안 평원에 계속 거주했습니다.[95]

고대 후기와 중세.

콘스탄티누스 황제의 비잔티움 제국 통치로 전환되면서 초기 기독교는 더 관대한 로마의 이교도를 대체했습니다.[104][105] 4세기 콘스탄티누스의 개종으로 팔레스타인의 유대인 대다수의 상황은 "더 어려워졌습니다."[100] 유대인과 유대교를 차별하는 법들이 잇따라 통과됐고, 유대인들은 교회와 당국으로부터 박해를 받았습니다.[105] 많은 유대인들이 번성하는 디아스포라 공동체로 이주했고,[106] 지역적으로는 기독교 이민과 지역 개종이 있었습니다. 5세기 중반쯤에는 기독교인이 대다수였습니다.[107][108] 5세기 말 무렵 사마리아인의 반란이 일어나 6세기 말까지 계속되었고 그 결과 사마리아인의 인구가 크게 감소했습니다.[109] 614년 사산의 예루살렘 정복과 헤라클리우스에 대항한 단명한 유대인 반란 이후, 비잔티움 제국은 628년에 이 지역의 지배권을 다시 확보했습니다.[110]

서기 634-641년에 라시둔 칼리파가 레반트를 정복했습니다.[106][111][112] 이후 6세기에 걸쳐 우마이야 왕조, 아바스 왕조, 파티미드 칼리파 왕조, 그리고 그 후 셀주크 왕조와 아유비드 왕조 사이에 이 지역의 지배권이 넘어갔습니다.[113] 그 후 몇 세기 동안 인구는 급격하게 감소하여 로마와 비잔틴 시대에 약 100만 명으로 추정되는 인구가 오스만 초기에는 약 30만 명으로 감소했으며, 비이슬람권 이민, 무슬림 이민 및 현지 개종으로 인한 아랍화 및 이슬람화의 꾸준한 과정이 있었습니다.[112][111][114][80] 11세기 말에는 무슬림의 지배로부터 예루살렘과 성지를 빼앗고 십자군 국가를 세우려는 기독교 십자군의 의도가 거의 승인되지 않은 십자군 원정이 이루어졌습니다.[115] 1291년 이집트의 맘루크 술탄들에 의해 무슬림의 통치가 완전히 회복되기 전에 아유비왕조는 십자군을 밀어냈습니다.[116]

근세와 시온주의의 출현

1516년, 이 지역은 오스만 제국에 의해 정복되었고, 이후 4세기 동안 오스만 시리아의 일부로 통치되었습니다. 1660년 드루즈의 반란으로 사페드와 티베리아스가 멸망했습니다.[117] 18세기 후반, 현지 아랍인 셰이크 자히르 알 우마르는 갈릴리에 사실상 독립된 에미리트를 만들었습니다. 오스만 제국은 셰이크를 제압하려다 실패했지만, 자히르가 죽은 후 오스만 제국은 이 지역을 다시 장악했습니다. 1799년 재자르 파샤 총독은 나폴레옹 군대가 아크레를 공격한 것을 격퇴하여 프랑스는 시리아 작전을 포기했습니다.[118] 1834년 무함마드 알리의 이집트 징병제와 과세 정책에 반대하는 팔레스타인 아랍 농민들의 반란은 진압되었고, 1840년 영국의 지원으로 무함마드 알리의 군대는 후퇴하고 오스만 제국의 통치는 회복되었습니다.[119] 얼마 지나지 않아, 탄지마트 개혁이 오스만 제국 전역에서 시행되었습니다.

유대인 디아스포라가 존재한 이후 많은 유대인들이 '지온'으로 돌아가기를 열망했습니다.[120] 오스만 통치 초기부터 시온주의 운동이 시작될 때까지 팔레스타인의 유대인 인구는 소수로 구성되어 있었고, 규모도 변동이 심했습니다. 16세기 동안 유대인 공동체는 예루살렘, 티베리아스, 헤브론, 사페드 등 4개의 신성한 도시에 뿌리를 내렸고, 1697년 랍비 예후다 하카시드는 1,500명의 유대인 집단을 이끌고 예루살렘으로 갔습니다.[121] 18세기 후반, 페루심으로 알려진 하시디즘에 반대하는 동유럽 유대인들이 팔레스타인에 정착했습니다.[122][123]

제1차 알리야(First Aliyah)로 알려진 현대 유대인들의 팔레스타인 이주의 첫 번째 물결은 1881년 동유럽의 포그롬에서 유대인들이 달아나면서 시작되었습니다.[124] 이어진 1882년 5월 법은 유대인에 대한 경제적 차별을 증가시켰고, 그들이 살 수 있는 장소를 제한했습니다.[125][126] 이에 대응하여 정치적 시온주의가 형성되기 시작했고, 일부 활동가들은 빌루와 시온의 연인과 같은 운동을 설립했으며, 레온 핀스커는 유대인들에게 국가 독립을 촉구하는 팸플릿 오토 엠카피케이션(1882)을 출판했습니다.[127][128] 테오도르 헤르즐은 이스라엘 땅에 유대인 국가를 세우려는 운동인 [129]정치적 시온주의를 창시하여 유럽 국가들의 소위 유대인 문제에 대한 해결책을 제시한 것으로 알려져 있습니다.[130] 1896년, 헤르츨은 유대인 국가(The Judenstaat)를 출판했고, 이듬해 제1차 시온주의 회의를 주재했습니다.[131] 제2차 알리야(1904-1914)는 키시네프 포그롬 이후 시작되었으며, 약 4만 명의 유대인이 팔레스타인에 정착했지만, 거의 절반이 결국 떠났습니다. 이주민의 제1파동과 제2파동은 모두 정통파 유대인들이 주를 이루었지만,[132] 제2알리야에는 유대인 노동력만을 바탕으로 한 별도의 유대인 경제를 수립한다는 생각을 바탕으로 키부츠 운동을 전개한 시온주의 사회주의 단체들이 포함되어 있었습니다.[133][134] 앞으로 수십 년 안에 이슈브의 지도자가 될 제2차 알리야의 사람들은 정착민 경제가 아랍의 노동에 의존해서는 안 된다고 믿었습니다. 이러한 "노동의 정복"은 새로운 이슈브의 민족주의 이념이 사회주의 이념을 압도하면서 아랍 국민들과의 적대감의 지배적인 원천이 될 것입니다.[135] 제2차 알리야의 이민자들은 주로 공동의 유대인 농업 정착지를 만들려고 노력했지만, 그 시기에는 1909년 텔아비브가 최초로 계획된 유대인 마을로 설립되었습니다. 이 시기에는 유대인 무장 민병대도 출현했는데, 첫 번째는 1907년 바르-지오라였습니다. 2년 후, 더 큰 규모의 하쇼머 조직이 그 대체 조직으로 설립되었습니다.

차임 바이즈만이 시온주의 운동에 대한 영국의 지지를 얻기 위해 노력한 것은 결국 1917년 발푸어 선언을 확보하게 될 것입니다.[136] 아서 밸푸어 영국 외무장관은 영국 유대인 공동체의 지도자인 로스차일드 경에게 밸푸어 선언문을 보내 팔레스타인에 유대인 '국민의 집'을 건립하는 것을 영국이 지지한다고 밝혔습니다.[137][138] 바이츠만은 이 선언에 대한 해석은 국가의 미래에 대한 협상이 아랍 대표를 제외하고 영국과 유대인 사이에서 직접 이루어질 것이라는 것을 수반했습니다. 파리 평화 회의에서 그의 유명한 발표는 팔레스타인을 영국처럼 유대인으로 만드는 목표가 영어라고 말하면서 이러한 해석을 반영할 것입니다. 그 후 몇 년 동안 유대인과 팔레스타인의 관계는 극적으로 악화되었습니다.[139]

1918년, 주로 시온주의자 자원봉사자들로 이루어진 유대인 군단이 영국의 팔레스타인 정복을 도왔습니다.[140] 1920년, 이 영토는 위임통치 체제 아래 영국과 프랑스 사이에서 나뉘었고, 영국이 통치하는 지역(현대 이스라엘 포함)은 의무 팔레스타인으로 명명되었습니다.[116][141][142] 영국의 통치와 유대인 이민에 대한 아랍의 반대로 1920년 팔레스타인 폭동이 일어났고, 하소머의 파생물로서 하가나(Haganah, 히브리어로 The Defense)로 알려진 유대인 민병대가 형성되었으며, 나중에 이르군과 레히 준군사조직이 분열되었습니다.[143] 1922년, 국제 연맹은 유대인들에 대한 약속과 아랍 팔레스타인에 대한 유사한 조항을 포함한 발푸어 선언을 포함한 조건에 따라 영국에게 팔레스타인 위임통치령을 부여했습니다.[144] 이 지역의 인구는 유대인이 약 11%,[145] 아랍 기독교인이 약 9.5%를 차지할 정도로 아랍계와 무슬림이 우세했습니다.[146]

제3차(1919–1923)와 제4차 알리야(1924–1929)는 추가로 10만 명의 유대인을 팔레스타인으로 데려왔습니다. 1930년대 유럽에서 나치즘의 발흥과 유대인에 대한 박해가 증가하면서 유대인 25만 명이 유입된 제5차 알리야가 발생했습니다. 이것은 1936-39년 아랍 반란의 주요 원인이었습니다. 영국 보안군과 시온주의 민병대는 아랍인들 사이에 심각한 내전을 일으켰던 반란을 진압했습니다. 수백 명의 영국 보안요원과 유대인이 사망했고, 아랍인 5,032명이 사망하고 1만 4,760명이 부상을 입었으며, 1만 2,622명이 구금되었습니다.[147][148][149] 팔레스타인 성인 남성 아랍인 인구의 약 10퍼센트가 사망, 부상, 투옥 또는 추방당했습니다.[150]

영국은 1939년 백서로 유대인의 팔레스타인 이주 제한을 도입했습니다. 세계 각국이 홀로코스트에서 탈출한 유대인 난민들을 외면하는 가운데, 알리야 베트라고 알려진 비밀 운동이 유대인들을 팔레스타인으로 데려오기 위해 조직되었습니다. 제2차 세계대전이 끝날 무렵, 팔레스타인 전체 인구의 31%가 유대인이었습니다.[151] 영국은 이민 제한을 둘러싸고 유대인들의 반란과 제한 수준을 놓고 아랍 공동체와 계속되는 갈등에 직면해 있었습니다. 하가나족은 이르군과 레히족과 함께 영국의 통치에 대항하는 무장투쟁을 벌였습니다.[152] 동시에 수십만 명의 유대인 홀로코스트 생존자들은 유럽에서 파괴된 공동체로부터 멀리 떨어진 새로운 삶을 추구했습니다. 하가나족은 알리야 베트라는 프로그램을 통해 수만 명의 유대인 난민들을 배로 팔레스타인으로 데려오려고 했습니다. 대부분의 배들은 영국 해군에 의해 요격되었고 아틀리트와 키프로스의 수용소에 수용된 난민들입니다.[153][154]

1946년 7월 22일, 이르군은 팔레스타인에 대한 영국 행정 본부를 폭격하여 91명이 사망했습니다.[155][156][157][158][159][160] 공격은 처음에는 하가나족의 승인을 받았습니다. 이 작전은 아가타 작전(영국이 유대인 조직에 대한 습격을 포함한 일련의 공격)에 대한 대응으로 고안되었으며, 위임통치 시대 동안 영국에 대한 가장 치명적인 공격이었습니다.[159][160] 유대인들의 반란은 영국군과 팔레스타인 경찰의 공동 진압 노력에도 불구하고 1946년과 1947년 내내 계속되었습니다. 유대인들이 유대인 국가를 포함하지 않는 어떤 해결책도 받아들이지 않고 팔레스타인을 유대인 국가와 아랍 국가로 분할할 것을 제안함에 따라, 유대인 및 아랍 국가 대표들과 협상된 해결책을 중재하려는 영국의 노력도 실패했습니다. 아랍인들은 팔레스타인의 어느 지역에 있는 유대인 국가는 받아들일 수 없으며 유일한 해결책은 아랍의 통치하에 있는 통일된 팔레스타인이라고 단호하게 주장했습니다. 1947년 2월, 영국은 팔레스타인 문제를 새로 구성된 유엔에 회부했습니다. 1947년 5월 15일, 유엔 총회는 "팔레스타인 문제에 대한 보고서를 준비하기 위해" 특별 위원회를 만들 것을 결의했습니다.[161] 위원회[162] 보고서는 영국 위임통치령을 "독립적인 아랍 국가, 독립적인 유대 국가, 그리고 국제 신탁통치 체제 하에 있는 마지막 예루살렘시"로 대체하는 계획을 제안했습니다.[163] 한편, 유대인들의 반란은 계속되었고 1947년 7월에 절정에 이르렀고, 일련의 광범위한 게릴라 습격은 세 명의 이르군 작전원들의 계획된 처형에 대한 지렛대로 이르군이 두 명의 영국 중사를 인질로 잡은 사건으로 끝이 났습니다. 사형이 집행된 후, 이르군은 두 명의 영국 병사를 죽이고, 나무에 그들의 시체를 매달고, 현장에 영국 병사를 다치게 한 부비 트랩을 남겼습니다. 그 사건은 영국에서 광범위한 분노를 일으켰습니다.[164] 1947년 9월, 영국 내각은 위임통치령이 더 이상 유지될 수 없게 되자 팔레스타인을 탈출시키기로 결정했습니다.[164]

1947년 11월 29일 총회는 결의 181호(II)를 채택했습니다.[165] 결의안에 첨부된 계획은 본질적으로 9월 3일 보고서에서 제안된 것입니다. 유대인 공동체의 공인된 대표인 유대인 기구는 의무 팔레스타인의 55~56%를 유대인에게 할당한 이 계획을 수용했습니다. 당시 유대인은 인구의 약 3분의 1이었고 토지의 약 6~7%를 소유하고 있었습니다. 아랍인이 대다수를 차지했고, 토지의 약 20%를 소유했으며, 나머지는 위임통치 당국이나 외국인 토지 소유자가 소유했습니다.[166][167][168][169][170][171][172] 팔레스타인 아랍연맹과 아랍 고등위원회는 이를 거부하고,[173] 다른 어떤 분할 계획도 거부할 것임을 시사했습니다.[174][175] 1947년 12월 1일, 아랍 고등 위원회는 3일간의 파업을 선포했고, 예루살렘에서 폭동이 일어났습니다.[176] 상황은 내전으로 번졌고, 유엔 투표 2주 후, 식민지 장관 아서 크리치 존스는 1948년 5월 15일에 영국 위임통치령이 끝날 것이라고 발표했습니다. 아랍 민병대와 갱단이 유대인 지역을 공격하면서, 그들은 주로 하가나족과 소규모의 이르군과 레히족에 맞섰습니다. 1948년 4월, Haganah는 공세로 전환했습니다.[177][178] 이 기간 동안 25만 명의 팔레스타인 아랍인들이 수많은 요인들로 인해 도망치거나 추방당했습니다.[179]

이스라엘의 국가

설립연도 및 초기연도

1948년 5월 14일, 영국 위임통치령이 만료되기 전날, 유대인 기구의 대표인 다비드 벤구리온은 "이스라엘 국가로 알려진 에레츠-이스라엘에 유대인 국가의 설립"을 선언했습니다.[180] 새 국가의 국경에 대한 선언문의 유일한 언급은 에레츠-이스라엘("이스라엘의 땅")[citation needed]이라는 용어의 사용입니다. 다음날, 아랍 4개국의 군대는이집트, 시리아, 트란스요르단 그리고 이라크는 1948년 아랍-이스라엘 전쟁을 일으키며 영국령 팔레스타인의 일부로 들어갔고 예멘, 모로코, 사우디아라비아 그리고 수단의 부대가 전쟁에 참여했습니다.[181][182][183][184][185] 침략의 명백한 목적은 유대인 국가의 수립을 막기 위한 것이었고, 일부 아랍 지도자들은 "유대인들을 바다로 몰아넣는 것"에 대해 이야기했습니다.[171][186][187] 베니 모리스에 따르면, 유대인들은 침략한 아랍 군대가 자신들을 학살하려는 의도를 가지고 있다고 걱정했습니다.[188] 아랍연맹은 이번 침공이 질서를 회복하고 더 이상의 유혈사태를 막기 위한 것이라고 밝혔습니다.[189]

1년간의 전투 끝에 휴전이 선언되고 그린 라인으로 알려진 임시 국경이 세워졌습니다.[190] 요르단은 동예루살렘을 포함한 서안 지구를 합병했고 이집트는 가자 지구를 점령했습니다. 유엔은 70만 명 이상의 팔레스타인인들이 추방되거나 도망친 것으로 추정했는데, 이는 아랍어로 "낙바"(Nakba, "재앙")으로 알려질 것입니다.[191] 약 156,000명이 남아 이스라엘의 아랍 시민이 되었습니다.[192]

이스라엘은 1949년 5월 11일 유엔의 회원국으로 승인되었습니다.[193] 이스라엘과 요르단의 평화협정 협상 시도는 이런 조약에 대한 이집트의 반응을 우려한 영국 정부가 요르단 정부에 반대 의사를 표명한 뒤 결렬됐습니다.[194] 국가 초기에는 데이비드 벤구리온 총리가 이끄는 노동당 시온주의 운동이 이스라엘 정치를 지배했습니다.[195][196]

1940년대 말에서 1950년대 초 사이에 이스라엘로의 이민은 이스라엘 이민부의 도움을 받았고 비정부는 모사드 르 알리야 베트("lit.이민을 위한 기관 B")[197]를 후원했습니다. 후자는 특히 유대인의 생명이 위험하고 탈출이 어려운 중동과 동유럽 국가에서 비밀 작전을 벌였습니다. 모사드 르 알리야 벳은 1953년에 해체되었습니다.[198] 이민은 원 밀리언 플랜에 따른 것이었습니다. 일부 이민자들은 시온주의 신앙을 가지고 있거나 더 나은 삶을 약속받기 위해 왔고, 다른 이민자들은 박해를 피해 이주하거나 추방당했습니다.[199][200]

첫 3년 동안 홀로코스트 생존자와 아랍 및 이슬람 국가의 유대인들이 이스라엘로 유입되면서 유대인의 수는 70만 명에서 1,400,000명으로 증가했습니다. 1958년까지 인구는 2백만 명으로 증가했습니다.[201] 1948년에서 1970년 사이 약 1,150,000명의 유대인 난민이 이스라엘로 이주했습니다.[202] 새로운 이민자들 중 일부는 난민으로 도착하여 마아바롯이라고 알려진 임시 수용소에 수용되었습니다. 1952년까지 20만 명이 넘는 사람들이 이 텐트 도시에 살고 있었습니다.[203] 유럽 배경의 유대인들은 종종 중동 및 북아프리카 국가의 유대인들보다 더 호의적인 대우를 받았습니다. 후자를 위해 예약된 주택 단위는 종종 전자를 위해 다시 지정되었기 때문에 아랍 땅에서 새로 도착한 유대인들은 일반적으로 환승 수용소에 더 오래 머무르게 되었습니다.[204][205] 이 기간 동안 식료품, 의류 및 가구는 긴축 기간으로 알려진 기간에 배급되어야 했습니다. 위기를 해결해야 할 필요성 때문에 벤구리온은 이스라엘이 홀로코스트에 대한 금전적 보상을 받아들일 수 있다는 생각에 분노한 유대인들의 대규모 시위를 촉발시킨 서독과 배상 협정에 서명하게 되었습니다.[206]

아랍-이스라엘 분쟁

1950년대 동안 이스라엘은 팔레스타인 페다옌에 의해 자주 공격을 받았는데,[207] 거의 항상 이집트가 점령한 가자 지구에서 민간인을 공격하여 [208]여러 번의 이스라엘 보복 작전을 벌였습니다. 1956년, 영국과 프랑스는 이집트가 국유화한 수에즈 운하를 다시 장악하는 것을 목표로 삼았습니다. 이스라엘의 남부 인구에 대한 페다예인의 공격 증가와 최근 아랍의 위협적인 성명과 함께 수에즈 운하와 티란 해협의 이스라엘 선박 봉쇄가 계속되면서 이스라엘은 이집트를 공격하게 되었습니다.[209][210][211] 이스라엘은 영국, 프랑스와 비밀동맹을 맺고 수에즈 사태에서 시나이반도를 압도했지만, 이스라엘의 해운권 보장을 대가로 유엔으로부터 철수 압력을 받았습니다.[212][213][214] 전쟁으로 이스라엘 국경 침투가 크게 줄었습니다.[215]

1960년대 초, 이스라엘은 아르헨티나에서 나치 전범 아돌프 아이히만을 붙잡아 재판을 받기 위해 이스라엘로 데려왔습니다.[216] 아이히만은 이스라엘 민간 법정에서 유죄 판결을 받아 처형된 유일한 사람으로 남아 있습니다.[217] 1963년 봄과 여름 동안 이스라엘은 이스라엘의 핵 프로그램으로 인해 미국과 외교적 교착 상태에 빠졌습니다.[218][219]

1964년부터 요르단강의 물을 해안 평원으로 돌리려는 이스라엘의 계획에 대해 우려한 [220]아랍 국가들은 이스라엘로부터 수자원을 빼앗기 위해 상수원을 돌리려고 노력해 왔으며, 한편으로는 이스라엘과 다른 한편으로는 시리아와 레바논 사이의 긴장을 유발했습니다. 가말 압델 나세르 이집트 대통령이 이끄는 아랍 민족주의자들은 이스라엘을 인정하지 않고 이스라엘의 파괴를 촉구했습니다.[221][222][223] 1966년까지 이스라엘과 아랍의 관계는 이스라엘군과 아랍군 사이에 전투가 벌어질 정도로 악화되었습니다.[224]

1967년 5월, 이집트는 이스라엘과의 국경 부근에서 군대를 집결시키고, 1957년부터 시나이 반도에 주둔하고 있는 유엔 평화유지군을 추방하고, 이스라엘의 홍해 접근을 차단했습니다.[225][226][227] 다른 아랍 국가들은 군대를 동원했습니다.[228] 이스라엘은 이러한 행동들이 카수스 벨리(casus belli)라고 거듭 강조했고, 6월 5일 이집트에 대한 선제공격을 시작했습니다. 요르단, 시리아, 이라크가 이스라엘을 공격했습니다. 이스라엘은 6일간의 전쟁에서 요르단으로부터 서안 지구, 이집트로부터 가자 지구와 시나이 반도, 그리고 시리아로부터 골란 고원을 점령했습니다.[229] 동예루살렘을 편입하면서 예루살렘의 경계가 확대됐고, 1949년 그린라인은 이스라엘과 점령지 사이의 행정 경계가 됐습니다.[citation needed]

1967년 전쟁과 아랍 연맹의 "세 가지 반대" 결의안에 이어, 이스라엘은 1967-1970년 소모전 동안 시나이 반도의 이집트인들과 점령지, 이스라엘 및 전 세계의 이스라엘인들을 겨냥한 팔레스타인 단체들의 공격에 직면했습니다. 여러 팔레스타인과 아랍 단체들 중 가장 중요한 것은 1964년에 설립된 팔레스타인 해방 기구(PLO)로, 처음에는 "고국을 해방하는 유일한 방법으로서 무장 투쟁"에 전념했습니다.[230] 1960년대 말과 1970년대 초, 팔레스타인 단체들은 1972년 뮌헨 하계 올림픽에서 이스라엘 선수들을 학살하는 [233]등 전 세계의 이스라엘과 유대인 목표물에 대한 공격을[231][232] 시작했습니다. 이스라엘 정부는 학살 조직원들에 대한 암살 작전과 레바논에 있는 PLO 본부에 대한 폭격, 그리고 공습으로 대응했습니다.

1973년 10월 6일, 이집트와 시리아군은 시나이 반도와 골란 고원에서 이스라엘군을 기습 공격하여 욤키푸르 전쟁을 시작했습니다. 전쟁은 10월 25일 이스라엘이 이집트와 시리아군을 격퇴하면서 끝났지만 약 20일 만에 10-35,000명의 목숨을 앗아간 전쟁에서 2,500명 이상의 군인이 사망했습니다.[234] 전쟁 전과 전쟁 중의 실패에 대한 정부의 책임은 내부 조사에서 면제되었지만, 대중의 분노로 골다 메이어 총리는 사임해야 했습니다.[235][better source needed] 1976년 7월, 여객기 한 대가 이스라엘에서 프랑스로 가던 중 팔레스타인 게릴라들에 의해 납치되어 우간다의 엔테베 국제공항에 착륙했습니다. 이스라엘 특공대, 인질 106명 중 102명 구출

1977년 크네세트 선거는 메나켐 베긴의 리쿠드당이 노동당으로부터 정권을 잡으면서 이스라엘 정치사에 큰 전환점을 맞았습니다.[236] 그 해 말, 안와르 엘 사다트 이집트 대통령은 이스라엘을 방문하여 크네세트 앞에서 아랍 국가원수가 이스라엘을 처음으로 인정한 연설을 했습니다.[237] 사다트와 베긴은 캠프 데이비드 협정(1978)과 이집트-이스라엘 평화 조약(1979)에 서명했습니다.[238] 그 대가로 이스라엘은 시나이반도에서 탈퇴하고 요르단강 서안지구와 가자지구의 팔레스타인 자치권을 놓고 협상에 들어가기로 합의했습니다.[238]

1978년 3월 11일, 레바논으로부터의 PLO 게릴라 습격은 해안 도로 학살로 이어졌습니다. 이스라엘은 PLO 기지 파괴를 위해 남부 레바논 침공에 나섰습니다. 대부분의 PLO 전사들이 철수했지만, 이스라엘은 유엔군과 레바논군이 점령할 때까지 레바논 남부를 확보할 수 있었습니다. PLO는 곧 이스라엘에 대한 반란을 재개했습니다. 그 후 몇 년 동안 PLO는 남쪽으로 침투하여 국경을 넘어 산발적인 포격을 계속했습니다. 이스라엘은 수많은 보복 공격을 감행했습니다.

한편, 베긴 정부는 이스라엘인들이 점령된 요르단강 서안에 정착할 수 있도록 인센티브를 제공하여 그곳의 팔레스타인인들과 마찰을 증가시켰습니다.[239] 예루살렘법(1980)은 이스라엘이 1967년 정부령에 의해 예루살렘을 합병한 것을 재확인하기 위해 일부 사람들에 의해 믿어졌으며 도시의 지위에 대한 국제적인 논란을 재점화했습니다. 이스라엘의 어떤 법률도 이스라엘의 영토를 규정하지 않았고, 동예루살렘을 구체적으로 포함한 어떤 법률도 없었습니다.[240] 1981년 이스라엘은 사실상 골란고원을 합병했습니다.[241] 유엔 안전보장이사회가 예루살렘법과 골란고원법을 모두 무효라고 선언하는 등 국제사회는 대체로 이런 움직임을 거부했습니다.[242][243] 1980년대 이후 에티오피아 유대인들의 여러 물결이 이스라엘로 이민을 왔고, 1990년에서 1994년 사이에 구소련 국가에서 이민을 오면서 이스라엘 인구는 12퍼센트 증가했습니다.[244]

1981년 6월 7일, 이란-이라크 전쟁 중, 이스라엘 공군은 이라크의 핵무기 프로그램을 방해하기 위해 바그다드 외곽에 건설 중인 이라크의 유일한 원자로를 파괴했습니다. 1982년 일련의 PLO 공격 이후 이스라엘은 PLO 기지를 파괴하기 위해 레바논을 침공했습니다.[245] 처음 6일 동안, 이스라엘은 레바논에 있는 PLO의 군사력을 파괴하고 시리아인들을 결정적으로 패배시켰습니다. 이스라엘 정부의 조사, 즉 카한 위원회는 나중에 베긴과 몇몇 이스라엘 장군들에게 사브라와 샤틸라 대학살에 대한 간접적인 책임을 묻고 아리엘 샤론 국방장관에게 "개인적인 책임"을 물을 것입니다.[246] 샤론은 어쩔 수 없이 사임했습니다.[247] 1985년 이스라엘은 키프로스에서 팔레스타인의 테러 공격에 대응하여 튀니지의 PLO 본부를 폭격했습니다. 이스라엘은 1986년 레바논 대부분에서 철수했지만, 2000년까지 레바논 남부의 국경지대 완충지대를 유지했으며, 그곳에서 이스라엘군은 헤즈볼라와 분쟁을 벌였습니다. 이스라엘 통치에 반대하는 팔레스타인 봉기인 제1차 인티파다는 1987년 점령된 요르단강 서안과 가자 지구에서 조정되지 않은 시위와 폭력의 물결로 발발했습니다.[248] 그 후 6년 동안 인티파다는 더욱 조직적이 되었고 이스라엘 점령을 방해하기 위한 경제 및 문화 조치를 포함했습니다. 천 명 이상이 목숨을 잃었습니다.[249] 1991년 걸프 전쟁 동안 PLO는 사담 후세인과 이라크의 이스라엘에 대한 미사일 공격을 지원했습니다. 여론의 분노에도 불구하고 이스라엘은 반격을 자제하라는 미국의 요구에 귀를 기울였습니다.[250][251]

1992년 이츠하크 라빈은 그의 당이 이스라엘의 이웃 국가들과 타협할 것을 요구한 선거 이후 총리가 되었습니다.[252][253] 이듬해 이스라엘을 대표하여 시몬 페레스와 PLO를 대표하는 마흐무드 압바스는 팔레스타인 자치정부(PNA)에 요르단강 서안지구와 가자지구의 일부 지역을 통치할 수 있는 권리를 부여한 오슬로 협정에 서명했습니다.[254] PLO는 또한 이스라엘의 생존권을 인정하고 테러를 중단할 것을 약속했습니다.[255][better source needed] 1994년 이스라엘-요르단 평화협정이 체결되어 요르단은 이스라엘과 관계를 정상화한 두 번째 아랍 국가가 되었습니다.[256] 이스라엘의[257] 정착촌과 검문소의 지속, 그리고 경제 상황의 악화로 인해 협정에 대한 아랍인들의 지지가 손상되었습니다.[258] 이스라엘 국민들의 협정 지지는 팔레스타인의 자살 공격 이후 시들해졌습니다.[259] 1995년 11월, 이츠하크 라빈은 협정에 반대하는 극우파 유대인 이갈 아미르에 의해 암살되었습니다.[260]

1990년대 말 베냐민 네타냐후 총리의 집권 기간 동안 이스라엘은 헤브론에서 탈퇴하기로 합의했지만,[261] 이는 비준되거나 이행되지 않았으며 [262]와이 강 비망록에 서명하여 PNA에 대한 더 큰 통제권을 부여했습니다.[263] 1999년에 총리로 선출된 에후드 바라크는 남부 레바논에서 군대를 철수하고 2000년 캠프 데이비드 정상회담에서 PNA의 야세르 아라파트 의장, 빌 클린턴 미국 대통령과 협상을 진행했습니다. Barak는 예루살렘을 공유 수도로 하는 가자 지구 전체와 요르단강 서안 지구의 90% 이상을 포함한 팔레스타인 국가 설립 계획을 제시했습니다.[264] 양측은 회담 실패의 책임을 상대방에게 돌렸습니다.

21세기

이 섹션을 업데이트해야 합니다. 그 이유는 분쟁에서 벗어난 지난 20년간의 사건들이 거의 다루어지지 않았기 때문입니다.이할 수 바랍니다. (2023년 3월) |

2000년 말, 리쿠드의 지도자 아리엘 샤론이 템플마운트를 방문한 후, 제2차 인티파다가 시작되었습니다. 그것은 앞으로 4년 반 동안 계속될 것입니다. 자살 폭탄 테러는 인티파다의 반복적인 특징이었습니다.[266] 일부 논평가들은 평화회담 결렬로 인해 인티파다가 아라파트에 의해 사전에 계획되었다고 주장합니다.[267][268][269][270] 샤론은 2001년 선거에서 총리가 되었고, 가자 지구에서 일방적으로 철수하려는 계획을 실행했으며,[271] 이스라엘 서안 장벽 건설을 주도하여 인티파다를 종식시켰습니다.[272] 2000년에서 2008년 사이에 이스라엘인 1,063명, 팔레스타인인 5,517명, 외국인 64명이 살해되었습니다.[273]

2006년 헤즈볼라의 이스라엘 북부 국경 지역에 대한 포격과 이스라엘 군인 2명의 국경을 초월한 납치 사건이 한 달간 계속된 제2차 레바논 전쟁을 촉발시켰습니다.[274][275] 2007년, 이스라엘 공군은 시리아에서 원자로를 파괴했습니다. 2008년, 하마스와 이스라엘 간의 휴전이 결렬되었습니다. 2008~2009년 가자 전쟁은 3주간 지속되었고 이스라엘이 일방적인 휴전을 발표한 후 종료되었습니다.[276][277] 하마스는 국경을 완전히 철수하고 개방하는 조건으로 자체 휴전을 발표했습니다. 로켓 발사도, 이스라엘의 보복 공격도 완전히 중단되지 않았음에도 불구하고, 취약한 휴전은 여전했습니다.[278] 이스라엘은 이스라엘 남부 도시들에 대한 팔레스타인의 로켓 공격이 100건 이상 발생한 것에 대한 대응으로 2012년 가자 지구에서 작전을 시작하여 8일 동안 계속되었습니다.[279][280] 이스라엘은 2014년 7월 하마스의 로켓 공격이 확대된 후 가자에서 또 다른 작전을 시작했습니다.[281] 2021년 5월 가자와 이스라엘에서 11일 동안 또 한 차례의 전투가 벌어졌습니다.[282]

2010년대에 이르러 이스라엘과 아랍 연맹 국가들 간의 증가하는 지역 협력이 구축되어 아브라함 협정의 체결로 끝이 났습니다. 이스라엘의 안보 상황은 전통적인 아랍-이스라엘 갈등에서 이란-이스라엘 대리 갈등과 시리아 내전 기간 동안 이란과의 직접적인 대립으로 전환되었습니다. 2023년 10월 7일, 하마스를 중심으로 한 가자 지구의 팔레스타인 무장 단체들이 이스라엘에 대한 일련의 협력 공격을 시작하면서 2023년 이스라엘-하마스 전쟁이 시작되었습니다.[283] 이날 가자지구 국경 인근 지역과 음악 축제 도중 주로 민간인인 이스라엘인 1300여명이 목숨을 잃었습니다. 생후 9개월 된 노인과 여성, 어린이 등 200여 명의 인질이 납치돼 가자지구로 끌려갔습니다.[284][285][286]

지리

이스라엘은 비옥한 초승달 지대에 위치하고 있습니다. 이 나라는 북쪽으로는 레바논, 북동쪽으로는 시리아, 동쪽으로는 요르단과 요르단강 서안, 남서쪽으로는 이집트와 가자 지구에 접해 있습니다. 북위 29° ~ 34° N, 동경 34° ~ 36° 사이에 위치합니다.

이스라엘의 주권 영토는 (1949년 정전협정의 경계선에 따라 1967년 6일 전쟁 동안 이스라엘에 의해 점령된 모든 영토를 제외한) 약 20,770 평방 킬로미터이며, 이 중 2%는 물입니다.[287] 그러나 이스라엘은 매우 좁아서(남북 400km에 비해 가장 넓은 100km) 지중해의 배타적 경제수역은 국토 면적의 두 배에 이릅니다.[288] 동예루살렘과 골란고원을 포함한 이스라엘 법상의 총 면적은 22,072㎢(8,522㎢)이며,[289] 요르단강 서안지구의 군사적 지배와 부분적인 팔레스타인 지배 영토를 포함한 이스라엘의 지배하에 있는 총 면적은 27,799㎢(10,733㎢)입니다.[290]

이스라엘은 작은 크기에도 불구하고 남쪽의 네게브 사막에서부터 내륙의 비옥한 이스르엘 계곡, 갈릴리 산맥, 카르멜 산맥, 북쪽의 골란 산맥에 이르기까지 다양한 지리적 특징의 고향입니다. 지중해 연안의 이스라엘 해안 평원에는 대부분의 인구가 살고 있습니다.[291] 중부 고원의 동쪽에는 6,500km(4,039마일)의 그레이트 리프트 밸리의 작은 부분인 요르단 리프트 밸리가 있습니다. 요르단 강은 요르단 리프트 밸리를 따라 헤몬 산에서 훌라 밸리와 갈릴리 바다를 거쳐 지표면에서 가장 낮은 지점인 사해까지 이어집니다.[292] 더 남쪽은 홍해의 일부인 아일라트 만으로 끝나는 아라바 강입니다. 마흐테쉬, 즉 "침식 서커스"는 네게브 반도와 시나이 반도의 고유한 것으로, 가장 큰 것은 길이 38km의 마흐테쉬 라몬입니다.[293] 이스라엘은 지중해 분지에 있는 나라들 중 제곱미터 당 가장 많은 식물 종을 가지고 있습니다.[294] 이스라엘은 4개의 육상 생태 지역을 포함하고 있습니다. 동부 지중해 침엽수-엽수-광엽수 숲, 남부 아나톨리아 산지 침엽수 및 낙엽수 숲, 아라비아 사막, 메소포타미아 관목 사막.[295]

이스라엘의 현대 숲은 모두 손으로 심은 것입니다. 1901년 이래로, 이스라엘 정부의 삼림 벌채 프로그램은 원래의 "레바논의 시체"를 대체하기 위해 2억 6천만 그루가 넘는 나무를 심었습니다.[296][297][298]

구조론과 지진학

조던 리프트 밸리는 사해 변환(DSF) 단층 시스템 내의 지각 운동의 결과입니다. DSF는 서쪽으로 아프리카 판과 동쪽으로 아라비아 판 사이의 변환 경계를 형성합니다. 골란고원과 요르단 전역은 아라비아판에 속하며, 갈릴리, 서안, 해안평원, 네게브와 시나이반도는 아프리카판에 속해 있습니다. 이러한 지각적 성향은 상대적으로 높은 지진 활동으로 이어집니다. 예를 들어 749년과 1033년에 이 구조물을 따라 발생한 두 번의 대지진 때 요르단 계곡 전체가 반복적으로 파열된 것으로 추정됩니다. 1033년 이후 쌓인 슬립 적자는 Mw~7.4의 지진을 일으키기에 충분합니다.[299]

알려진 가장 재앙적인 지진은 기원전 31년, 363년, 749년, 1033년에 발생했으며, 이는 평균 400년에 한 번꼴입니다.[300] 심각한 인명 손실로 이어지는 파괴적인 지진은 약 80년마다 발생합니다.[301] 엄격한 건축 규제가 시행되고 있고 최근에 지어진 건축물들은 지진에 안전하지만, 2007년[update] 기준으로 50,000개의 주거용 건물뿐만 아니라 많은 공공 건물들이 새로운 기준을 충족하지 못했고 강한 지진에 노출되면 "붕괴될 것"으로 예상되었습니다.[301]

기후.

이스라엘의 기온은 특히 겨울 동안 천차만별입니다. 텔아비브와 하이파와 같은 해안 지역은 시원하고 비가 많이 오는 겨울과 길고 더운 여름을 가진 전형적인 지중해성 기후를 가지고 있습니다. 비에르셰바 지역과 북부 네게브 지역은 여름이 덥고 겨울이 시원하며 비가 적게 오는 반건조 기후입니다. 남부 네게브와 아라바 지역은 사막 기후로 매우 덥고 건조한 여름과 온화한 겨울에 며칠 동안 비가 내립니다. 아프리카와 북미 이외의 지역에서 2021년[update] 기준으로 세계에서 가장 높은 기온인 54°C(129°F)는 1942년 요르단강 북부 계곡의 티라트 즈비키부츠에서 기록되었습니다.[302][303] 산악 지역은 바람이 불고 추울 수 있으며, 해발 750미터(2,460피트) 이상(예루살렘과 같은 고도)의 지역에는 보통 매년 적어도 한 차례 이상의 눈이 내릴 것입니다.[304] 5월부터 9월까지 이스라엘에는 비가 거의 내리지 않습니다.[305][306]

이스라엘에는 온대와 열대 지역 사이에 위치해 있기 때문에 네 개의 다른 식물 지리학적 지역이 있습니다. 이러한 이유로 동식물은 매우 다양합니다. 이스라엘에는 2,867종의 식물이 알려져 있습니다. 이 중 최소 253종이 소개되고 비토종입니다.[307] 380개의 이스라엘 자연 보호 구역이 있습니다.[308]

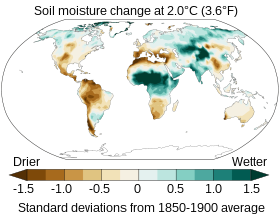

부족한 수자원으로 이스라엘은 점적 관개를 포함한 다양한 물 절약 기술을 개발했습니다.[309][better source needed] 태양 에너지에 사용할 수 있는 상당한 햇빛은 이스라엘을 1인당 태양 에너지 사용에서 선도적인 국가로 만듭니다. 실질적으로 모든 집은 태양 전지판을 물 난방에 사용합니다.[310] 이스라엘 환경 보호부는 기후 변화가 특히 취약한 인구에게 "모든 삶의 영역에 결정적인 영향을 미칠 것"이라고 보고했습니다.[311]

인구통계

이스라엘은 세계에서 유대인 인구가 가장 많고, 유일하게 유대인이 다수인 나라입니다.[312] 2022년[update] 12월 31일 현재 이스라엘의 인구는 9,656,000명으로 추정됩니다. 2022년 정부는 인구의 73.6%를 유대인으로, 21.1%를 아랍인으로, 5.3%를 기타(비 아랍 기독교인 및 종교가 없는 사람)로 기록했습니다.[12] 지난 10년 동안 루마니아, 태국, 중국, 아프리카, 남아메리카 출신의 많은 이주 노동자들이 이스라엘에 정착했습니다. 정확한 수치는 알려지지 않았는데, 그들 중 많은 사람들이 불법으로 그 나라에 살고 있기 때문입니다만,[313] 추정치는 166,000에서 203,000에 이릅니다.[314] 2012년 6월까지 약 6만 명의 아프리카 이주민이 이스라엘에 입국했습니다.[315] 이스라엘인의 약 93%가 도시 지역에 살고 있습니다.[316] 팔레스타인 이스라엘인의 90%는 갈릴리, 트라이앵글, 네게브 지역에 집중된 인구 밀도가 높은 139개 마을에 거주하고 있으며, 나머지 10%는 혼합 도시와 지역에 거주하고 있습니다.[317][318][319][320][321] 2016년 OECD는 평균 기대수명을 82.5세로 추정했는데, 이는 세계에서 6번째로 높은 수치입니다.[322] 이스라엘 아랍인들의 기대 수명은 3~4년 정도 뒤처지지만,[323][324] 이는 여전히 대부분의 아랍 및 이슬람 국가들보다 높습니다.[325][326] 이스라엘은 유대 민족의 고향으로 세워졌으며 종종 유대 국가로 불립니다. 이 나라의 반환법은 모든 유대인과 유대인 혈통의 사람들에게 시민권을 부여합니다.[327] 1948년 이후 이스라엘 인구의 유지는 대규모 이민을 받는 다른 나라들과 비교할 때 거의 같거나 더 많습니다.[328] 주로 미국과 캐나다로 향하는 이스라엘(예리다로 불림)로부터의 유대인 이주는 인구 통계학자들에 의해 겸손하다고 묘사되지만,[329] 이스라엘 정부 부처들에 의해 종종 이스라엘의 미래에 대한 주요 위협으로 언급됩니다.[330][331]

이스라엘 유대인의 약 80%는 이스라엘에서 태어났고, 14%는 유럽과 아메리카에서 온 이민자들이고, 6%는 아시아와 아프리카에서 온 이민자들입니다.[332] 아슈케나지 유대인을 포함한 유럽 및 구소련 출신 유대인과 이스라엘에서 태어난 그 후손들은 유대인 이스라엘인의 약 44%를 차지합니다. 아랍과 이슬람 국가의 유대인들과 미즈라히와 세파르디 유대인들을 포함한 그들의 후손들은 나머지 유대인 인구의 대부분을 형성합니다.[333][334][335] 유대인 간 결혼 비율은 35% 이상이며, 최근 연구에 따르면 세파르디와 아슈케나지 유대인의 후손인 이스라엘인의 비율은 매년 0.5%씩 증가하며, 현재 25% 이상의 학생들이 두 유대인 모두에게서 기원하고 있습니다.[336] 민족적으로 "기타"로 정의되는 이스라엘인(30만 명)의 약 4%는 유대인 출신의 러시아계 후손 또는 가족으로 랍비 법에 따라 유대인이 아니지만 반환법에 따라 시민권을 받을 자격이 있었습니다.[337][338][339]

그린라인 너머 이스라엘 정착민의 수는 모두 60만 명이 넘습니다(≈ 유대계 이스라엘 인구의 10%). 2016년[update], 399,300명의 이스라엘인들이 헤브론과 구시 에치온 블록과 같은 도시에서 이스라엘 국가 설립 이전과 6일 전쟁 이후 다시 설립된 정착촌을 [341]포함하여 서안 정착촌에 거주했습니다. 또한 동예루살렘에는 20만 명 이상의 유대인이 살고 있었고,[342] 골란고원에는 2만 2천 명의 유대인이 살고 있었습니다.[341] 약 7,800명의 이스라엘인들이 Gush Katif로 알려진 가자 지구의 정착촌에서 2005년 정부에 의해 대피할 때까지 살았습니다.[343]

이스라엘 아랍인(동예루살렘과 골란고원의 아랍인 포함)은 인구의 21.1% 또는 1,995,000명으로 구성되어 있습니다.[344] 2017년 여론 조사에서 이스라엘 아랍 시민의 40%가 "이스라엘의 아랍인" 또는 "이스라엘의 아랍인"으로, 15%가 "팔레스타인인", 8.9%가 "이스라엘의 팔레스타인인" 또는 "이스라엘의 팔레스타인인", 8.7%가 "아랍인"[345][346]으로 확인되었습니다.

주요 도시지역

이스라엘에는 4개의 주요 대도시 지역이 있습니다. 구시단(텔아비브 수도권, 인구 385만 4천 명), 예루살렘(인구 125만 3천 900명), 하이파(92만 4천 400명), 비에르셰바(37만 7천 100명).[347]

인구와 면적 면에서 이스라엘에서 가장 큰 지방 자치 단체는 125 평방 킬로미터(48 평방 마일)의 면적에 966,210명의 주민이 살고 있는 예루살렘입니다.[348] 예루살렘에 대한 이스라엘 정부 통계에는 동예루살렘의 인구와 면적이 포함돼 있는데, 그 현황은 국제 분쟁 중입니다.[349] 텔아비브와 하이파는 각각 467,875명과 282,832명의 인구를 가진 이스라엘에서 다음으로 인구가 많은 도시입니다.[348] 브네이브락(주로 하레디)은 이스라엘에서 인구밀도가 가장 높은 도시이며 세계에서 인구밀도가 가장 높은 10개 도시 중 하나입니다.[350]

이스라엘은 인구가 10만 명이 넘는 16개의 도시를 가지고 있습니다. 2018년[update] 현재 77개의 이스라엘 지방 자치체가 내무부로부터 "시"(또는 "도시") 지위를 부여받았으며,[351] 그 중 4개는 요르단강 서안에 있습니다.[352]

| 순위 | 이름. | 구 | 팝. | 순위 | 이름. | 구 | 팝. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

예루살렘  텔아비브 | 1 | 예루살렘 | 예루살렘 | 966,210a | 11 | 라맛 간 | 텔아비브 | 169,706 |  하이파  Rishon LeZion |

| 2 | 텔아비브 | 텔아비브 | 467,875 | 12 | 아쉬켈론 | 남부 | 149,160 | ||

| 3 | 하이파 | 하이파 | 282,832 | 13 | 레호봇 | 중앙의 | 147,878 | ||

| 4 | Rishon LeZion | 중앙의 | 257,128 | 14 | Beit Shemesh | 예루살렘 | 141,764 | ||

| 5 | 페타 티크바 | 중앙의 | 252,270 | 15 | 바트 얌 | 텔아비브 | 126,290 | ||

| 6 | 아슈도드 | 남부 | 225,975 | 16 | 헤르즐리야 | 텔아비브 | 103,318 | ||

| 7 | 네타냐 | 중앙의 | 224,066 | 17 | 크파르 사바 | 중앙의 | 101,801 | ||

| 8 | 브네이브레이크 | 텔아비브 | 212,395 | 18 | 하데라 | 하이파 | 100,631 | ||

| 9 | 비에르셰바 | 남부 | 211,251 | 19 | 모디인맥카빔로트 | 중앙의 | 97,097 | ||

| 10 | 홀론 | 텔아비브 | 197,464 | 20 | 로드 | 중앙의 | 82,629 | ||

^a 이 숫자는 동예루살렘과 요르단강 서안 지역을 포함하며, 2019년 총 인구는 573,[353]330명이었습니다. 동예루살렘에 대한 이스라엘의 주권은 국제적으로 인정받지 못하고 있습니다.

언어

이스라엘의 공용어는 히브리어입니다. 2018년까지는 아랍어도 공용어였지만,[9] 2018년에는 '주에서 특별한 지위'로 격하되었습니다.[10][11] 히브리어는 이 주의 주요 언어이며 대다수의 인구가 매일 사용합니다. 아랍어는 아랍 소수민족이 사용하며 히브리어는 아랍 학교에서 가르칩니다.

구소련과 에티오피아(이스라엘에는 약 13만 명의 에티오피아 유대인이 거주)로부터의 대량 이민으로 [354][355]인해 러시아어와 암하라어가 널리 사용되고 있습니다.[356] 1990년에서 2004년 사이에 100만 명 이상의 러시아어를 구사하는 이민자들이 이스라엘에 도착했습니다.[357] 프랑스어는 약 70만 명의 이스라엘인들이 사용하고 있으며,[358] 대부분 프랑스와 북아프리카에서 기원을 찾아볼 수 있습니다(마그레비 유대인 참조). 영어는 위임통치 기간 동안 공용어였습니다. 이스라엘이 설립된 후 이 지위를 잃었지만 여전히 공용어에 버금가는 역할을 하고 있습니다.[359][360][361] 많은 이스라엘인들은 많은 텔레비전 프로그램이 자막과 함께 영어로 방송되고 초등학교 초기부터 영어를 가르치기 때문에 영어로 의사소통을 상당히 잘합니다. 이스라엘 대학들은 다양한 주제에 대한 영어 강좌를 제공합니다.[362][better source needed]

종교

2022년 기준 이스라엘 인구의 종교적 소속은 유대인 73.6%, 무슬림 18.1%, 기독교 1.9%, 드루즈 1.6%입니다. 나머지 4.8%는 사마리아인과 바하 ʼ와 같은 종교와 "종교적으로 미분류"된 종교를 포함했습니다.

이스라엘 유대인의 종교적 관계는 매우 다양합니다. 2016년 퓨 리서치의 조사에 따르면 49%가 힐로니(세속적), 29%가 마소르티(전통적), 13%가 다티(종교적), 9%가 하레디(초정통적)라고 합니다.[364] 하레디 유대인은 2028년까지 이스라엘 유대인 인구의 20% 이상을 차지할 것으로 예상됩니다.[365]

이슬람교도는 인구의 약 17.6%를 차지하는 이스라엘 최대의 종교 소수민족입니다. 인구의 약 2%가 기독교인이고 1.6%가 드루즈입니다.[287] 기독교 인구는 주로 아랍 기독교인과 아람 기독교인으로 구성되어 있지만 대부분의 기독교인과 유대인이 기독교의 한 형태로 간주하는 소비에트 이후의 이민자, 외국인 노동자 및 메시아 유대교 신자도 포함됩니다.[366] 불교도와 힌두교도를 포함한 많은 다른 종교 집단의 구성원들은 비록 적은 숫자이지만 이스라엘에서 존재감을 유지하고 있습니다.[367] 구소련에서 온 100만 명이 넘는 이민자들 중 약 30만 명이 이스라엘의 랍비나토 추장에 의해 유대인이 아닌 것으로 여겨집니다.[368]

이스라엘은 모든 아브라함 종교에서 매우 중요한 지역인 성지의 주요 지역으로 구성되어 있습니다. 예루살렘은 서부 성벽과 템플마운트(Al-Aqsa Mosque compound)를 통합한 구시가지와 성묘교회와 같이 그들의 종교적 신념에 중추적인 장소의 본거지이기 때문에 유대인, 이슬람교도, 기독교인들에게 특히 중요합니다.[369] 이스라엘에서 종교적으로 중요한 다른 장소들은 나사렛(그리스도교에서는 성모 마리아 선언의 장소로서 거룩한), 티베리아스와 사페드(유대교에서는 4개의 신성한 도시들 중 두 곳), 람라의 흰 모스크(이슬람에서는 예언자 살레의 성지로서 거룩한), 성 조지 교회와 알 카드르 모스크입니다. Lod (기독교와 이슬람교에서는 성 조지 또는 알 키드르의 무덤으로 성역). 요르단강 서안에는 예수의 생가인 요셉의 무덤, 레이첼의 무덤, 총대주교들의 동굴 등 여러 종교적 명소들이 자리잡고 있습니다. 바하 ʼ 신앙의 행정 중심지와 바브 신전은 하이파의 바하 ʼ 세계 센터에 위치해 있으며, 신앙의 지도자는 아크레에 묻혀 있습니다. 마흐무드 모스크는 개혁주의자인 아마디야 운동과 연계되어 있습니다. 하이파의 유대인과 아마디 아랍인이 섞여 있는 지역인 카바비르는 이 나라에서 몇 안 되는 지역 중 하나입니다.[373][374]

교육

교육은 이스라엘 문화에서 높은 가치를 가지고 있으며 고대 이스라엘 사람들의 근본적인 블록으로 여겨졌습니다.[375] 2015년 OECD 회원국 중 고등교육을 받은 25-64세의 비율이 49%로 OECD 평균 35%[376]에 비해 3위를 차지했습니다. 2012년, 이 나라는 1인당 학업 학위 수 (인구의 20%)에서 3위를 차지했습니다.[377]

이스라엘의 학교 기대 수명은 16년이고 문해율은 97.8%[287]입니다. 국가 교육법(1953)은 다섯 가지 유형의 학교를 설립했습니다: 주 세속, 주 종교, 초정통, 공동 정착 학교 및 아랍 학교. 공립 세속주의는 가장 큰 학교 그룹이며 유대인과 아랍인이 아닌 학생들이 대부분 참석합니다. 대부분의 아랍인들은 그들의 아이들을 아랍어가 가르치는 언어인 학교에 보냅니다.[378] 교육은 3세에서 18세 사이의 어린이에게 의무적으로 실시됩니다.[379] 학교 교육은 초등학교 (1-6학년), 중학교 (7-9학년), 고등학교 (10-12학년)의 세 단계로 나뉘며, 바그루트 입학 시험으로 끝납니다. 수학, 히브리어, 히브리어 및 일반 문학, 영어, 역사, 성경 경전 및 시민학과 같은 핵심 과목에 대한 숙련도는 Bagrut 자격증을 받기 위해 필요합니다.[380]

이스라엘의 유대인 인구는 전체 이스라엘 유대인의 절반(46%) 미만이 중등 과정 이후 학위를 보유하고 있는 비교적 높은 수준의 교육 수준을 유지하고 있습니다.[381][382] 이스라엘 유대인들은 (25세 이상의 사람들 중) 평균 11.6년의 교육 기간을 가지고 있어, 그들은 세계의 모든 주요 종교 집단들 중에서 가장 높은 교육을 받은 사람들 중 하나입니다.[383][384] 아랍, 기독교, 드루즈 학파에서는 성경 공부에 대한 시험이 이슬람교, 기독교 또는 드루즈 유산에 대한 시험으로 대체됩니다.[385] 2020년에는 전체 이스라엘 12학년 학생의 68.7%가 입학 자격증을 취득했습니다.[386]

이스라엘은 양질의 대학 교육이 이스라엘의 현대 경제 발전을 촉진하는 데 큰 역할을 해온 고등 교육의 전통을 가지고 있습니다.[387] 이스라엘에는 9개의 공립 대학과 49개의 사립 대학이 있습니다.[380][388][389] 예루살렘 히브리 대학은 유대인과 헤브라이카의 세계에서 가장 큰 저장소인 이스라엘 국립 도서관을 보유하고 있습니다.[390] 테크니온 대학과 히브리 대학은 ARWU 순위로 세계 100대 대학에 꾸준히 이름을 올렸습니다.[391] 다른 주요 대학으로는 바이즈만 과학 연구소, 텔아비브 대학, 벤구리온 네게브 대학, 바일란 대학, 하이파 대학, 이스라엘 오픈 대학 등이 있습니다.

정부와 정치

이스라엘은 의회제, 비례대표제, 보통선거제를 실시하고 있습니다. 의회의 과반수의 지지를 받는 국회의원이 총리가 됩니다. 보통 이것은 가장 큰 정당의 의장입니다. 수상은 정부의 수반이자 내각의 수반입니다.[392][393] 대통령은 제한적이고 대부분 의례적인 직무를 수행하는 국가 원수입니다.[392]

이스라엘은 크네세트로 알려진 120명의 국회가 통치하고 있습니다. 크네세트의 당원권은 정당의 비례대표제를 기반으로 하며,[394][better source needed] 선거 문턱은 3.25%로 사실상 연립정부가 탄생했습니다. 요르단강 서안에 있는 이스라엘 정착촌 주민들은 투표할[395] 자격이 있으며 2015년 선거 이후 크네세트 120명 중 10명(8%)이 정착민이었습니다.[396] 의회 선거는 4년마다 예정되어 있지만 불안정한 연합이나 불신임 투표는 정부를 더 일찍 해산시킬 수 있습니다.[28] 최초의 아랍 주도 정당은 1988년에[397] 창당되었으며 2022년 현재 아랍 주도 정당은 약 10%의 의석을 보유하고 있습니다.[398] 기본법: 크네세트(1958)와 그 개정은 정당의 목적이나 행동에 "유대인의 국가로서 이스라엘 국가의 존재에 대한 부정"이 포함된 경우 정당 목록이 크네세트에 선거에 출마하는 것을 막습니다.

이스라엘의 기본법은 비준되지 않은 헌법으로 기능합니다. 이스라엘은 기본법에서 스스로를 유대인과 민주국가, 그리고 배타적으로 유대 민족의 민족국가로 규정하고 있습니다.[399] 2003년, 크네세트는 이 법들을 바탕으로 공식적인 헌법 초안을 작성하기 시작했습니다.[287][400]

이스라엘은 공식적인 종교는 없지만,[401][402][403] "유대인과 민주인"이라는 국가의 정의는 유대교와 강한 연관성을 만듭니다. 2018년 7월 19일 크네세트는 이스라엘을 주로 "유대인 민족 국가"로, 히브리어를 공용어로 규정하는 기본법을 통과시켰습니다. 이 법안은 아랍어에 대해 정의되지 않은 "특별한 지위"를 부여하고 있습니다.[404] 같은 법안은 유대인들에게 민족자결권에 대한 독특한 권리를 부여하고, 이 나라에서 유대인 정착촌의 발전을 "국익"으로 보고, 정부가 "이 이익을 장려하고, 발전시키고, 실행하기 위한 조치를 취할 수 있도록" 권한을 부여하고 있습니다.[405]

법제도

이스라엘은 3단 법정 체제를 가지고 있습니다. 가장 낮은 수준에는 전국 대부분의 도시에 위치한 치안 판사 법원이 있습니다. 그 위에는 항소 법원과 1심 법원의 역할을 하는 지방 법원이 있습니다. 그들은 이스라엘의 6개 지역 중 5개 지역에 위치하고 있습니다. 세 번째이자 가장 높은 단계는 예루살렘에 위치한 대법원이며, 최고 항소 법원과 고등 사법 법원의 이중 역할을 합니다. 후자의 역할에서 대법원은 1심 법원으로 판결하여 시민과 비시민을 막론하고 국가 당국의 결정에 불복하여 개인이 청원할 수 있도록 허용합니다.[406]

이스라엘의 법체계는 영국 관습법, 민법, 유대교 법의 세 가지 법적 전통을 결합하고 있습니다.[287] 이는 시선붕괴(판례)의 원칙에 기반을 두고 있으며, 적대적 시스템입니다. 법원 사건은 배심원의 역할이 없는 전문 판사가 결정합니다.[407][better source needed] 결혼과 이혼은 종교 법원의 관할 아래 있습니다. 유대인, 이슬람인, 드루즈인, 기독교인. 법관 선출은 법무부 장관(현 야리브 레빈)이 위원장을 맡고 있는 선정위원회가 수행합니다.[408] 이스라엘의 기본법: 인간의 존엄성과 자유는 이스라엘의 인권과 자유를 수호하고자 합니다. 유엔 인권이사회와 이스라엘 인권단체 아달라는 이 법이 사실상 평등과 비차별에 대한 일반적인 조항을 담고 있지 않다는 점을 강조했습니다.[409][410] "Enclave law"의 결과로 이스라엘 민법의 상당 부분이 점령 지역의 이스라엘 정착촌과 이스라엘 거주자에게 적용됩니다.[411]

행정구분

이스라엘은 중앙, 하이파, 예루살렘, 북, 남, 텔아비브 지역과 요르단강 서안의 유대, 사마리아 지역 등 6개의 주요 행정 구역으로 나뉩니다. 유대와 사마리아 지역 전체와 예루살렘과 북부 지역 일부는 국제적으로 이스라엘의 일부로 인정되지 않습니다. 지역은 다시 나포트로 알려진 15개의 하위 구역(히브루어: נפות; 단수: 나파)으로 나뉘며, 그 자체는 50개의 자연 지역으로 분할됩니다.

| 구 | 자본의 | 가장 큰 도시 | 2021년[341] 인구 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 유대인 | 아랍인 | 총 | 메모 | |||

| 예루살렘 | 예루살렘 | 66% | 32% | 1,209,700 | a | |

| 북쪽 | Nof HaGalil | 나사렛 | 42% | 54% | 1,513,600 | |

| 하이파 | 하이파 | 67% | 25% | 1,092,700 | ||

| 중심 | 람라 | Rishon LeZion | 87% | 8% | 2,304,300 | |

| 텔아비브 | 텔아비브 | 92% | 2% | 1,481,400 | ||

| 남쪽 | 비에르셰바 | 아슈도드 | 71% | 22% | 1,386,000 | |

| 유대와 사마리아 지역 | 아리엘 | 모디 인 일리트 | 98% | 0% | 465,400 | b |

이스라엘 시민권법

이스라엘 시민권과 관련된 주요 법률은 1950년 반환법과 1952년 시민권법입니다. 반환법은 유대인들에게 이스라엘로 이민을 가고 이스라엘 시민권을 얻을 수 있는 제한 없는 권리를 부여합니다. 국가 내에서 태어난 개인은 부모 중 한 명 이상이 시민인 경우 출생 시 시민권을 받습니다.[413]

이스라엘 법은 유대인의 국적을 이스라엘 국적과 구별되는 것으로 정의하고 있습니다. 사실, 이스라엘 대법원은 이스라엘 국적이 존재하지 않는다고 판결했습니다.[414][415] 유대인 국민은 이스라엘 법에서 유대교를 믿는 모든 사람과 그 후손으로 정의됩니다.[414] 법안은 2018년부터 이스라엘을 유대 민족의 민족 국가로 규정하고 있습니다.[416]

이스라엘이 점령한 영토

| 지역 | 관리자 | 지배권 인정 | 영유권 주장 | 채권의 인식 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 가자 지구 | 하마스가 장악한 팔레스타인 자치정부(법정) (사실상) | 오슬로 2차 협정의 증인 | 팔레스타인 주 | 139개 유엔 회원국 | |

| 웨스트 뱅크 | 팔레스타인 거주지 (A, B 지역) | 팔레스타인 자치정부와 이스라엘 군 | |||

| C구역 | 이스라엘인 거주지법(이스라엘인 거주지) 및 이스라엘군(이스라엘인 점령하의 팔레스타인인) | ||||

| 동예루살렘 | 이스라엘 행정부 | 온두라스, 과테말라, 나우루, 미국 | 중국, 러시아 | ||

| 서예루살렘 | 러시아, 체코, 온두라스, 과테말라, 나우루, 미국 | 동예루살렘과 함께 국제도시로서의 유엔 | 다양한 유엔 회원국과 유럽연합; 공동 주권도 널리 지지받고 있습니다. | ||

| 골란고원 | 미국 | 시리아 | 미국을 제외한 모든 유엔 회원국 | ||

| 이스라엘(적절) | 164개 유엔 회원국 | 이스라엘 | 164개 유엔 회원국 | ||

1967년, 6일간의 전쟁의 결과로 이스라엘은 동예루살렘, 가자 지구, 골란 고원을 포함한 서안 지구를 점령하고 점령했습니다. 이스라엘은 또한 시나이 반도를 점령했지만 1979년 이집트-이스라엘 평화 조약의 일부로 이집트에 반환했습니다.[238] 1982년에서 2000년 사이에 이스라엘은 안보 벨트라고 알려진 레바논 남부의 일부를 점령했습니다. 이스라엘이 이들 영토를 점령한 이후 레바논을 제외한 각 영토 내에 이스라엘 정착촌과 군사시설이 들어섰습니다.

골란고원과 동예루살렘은 이스라엘 법에 따라 완전히 이스라엘에 편입됐지만 국제법에는 편입되지 않았습니다. 이스라엘은 두 지역 모두에 민간법을 적용해 주민들에게 영주권과 시민권 신청 자격을 부여했습니다. 유엔 안전보장이사회는 골란고원과 동예루살렘의 병합을 '무효'로 선언하고, 이들 영토를 점령한 것으로 계속 보고 있습니다.[417][418] 이스라엘 정부와 팔레스타인 대표 간의 협상에서 동예루살렘의 지위는 때때로 어려운 문제였습니다.

동예루살렘을 제외한 요르단강 서안은 이스라엘 법률상 유대와 사마리아 지역으로 알려져 있으며, 이 지역에 거주하는 거의 40만 명의 이스라엘 정착민들은 이스라엘 인구의 일부로 간주되고 크네세트 대표권을 가지며 이스라엘의 민형사법의 상당 부분을 적용받고 있으며, 이들의 생산량은 이스라엘 경제의 일부로 간주됩니다.[419][fn 4] 이스라엘은 영토에 대한 법적 주장을 포기하거나 국경을 정의하지 않고 영토를 합병하는 것을 의식적으로 자제해 왔기 때문에 토지 자체는 이스라엘 법에 따라 이스라엘의 일부로 간주되지 않습니다.[419] 합병에 대한 이스라엘의 정치적 반대는 주로 요르단강 서안지구의 팔레스타인 인구를 이스라엘로 편입시키는 "인구학적 위협"으로 인식되기 때문입니다.[419] 요르단강 서안지구는 이스라엘의 직접적인 군사 지배하에 있으며, 이 지역의 팔레스타인인들은 이스라엘 시민이 될 수 없습니다. 국제사회는 이스라엘이 요르단강 서안에서 주권을 갖고 있지 않다는 입장을 고수하고 있으며, 이스라엘이 이 지역을 장악한 것은 현대 역사상 가장 긴 군사적 점령지로 간주하고 있습니다.[422] 요르단강 서안지구는 1949년 정전협정에 따라 1950년 요르단에 의해 점령 및 합병되었습니다. 오직 영국만이 이 합병을 인정했고 요르단은 그 이후로 그 영토에 대한 권리를 PLO에 양도했습니다. 인구는 1948년 아랍-이스라엘 전쟁의 난민을 포함하여 주로 팔레스타인 사람들입니다.[423] 1967년 점령 이후 1993년까지 이들 영토에 거주하는 팔레스타인인들은 이스라엘의 군사 행정 하에 있었습니다. 이스라엘-PLO 인정서 이후 대부분의 팔레스타인 인구와 도시는 팔레스타인 당국의 내부 관할 하에 있었고 이스라엘은 불안정한 기간 동안 군대를 재배치하고 완전한 군사 행정을 복원했지만 부분적인 이스라엘의 군사 통제만 받았습니다. 제2차 인티파다 동안 증가하는 공격에 대응하여 이스라엘 정부는 이스라엘 서안 장벽을 건설하기 시작했습니다.[424] 완공되면 장벽의 약 13%가 그린라인이나 이스라엘에 건설되고 87%가 요르단강 서안에 건설됩니다.[425][426]

이스라엘의 보편적 참정권 주장은 영토 경계가 모호해지고 점령지에 있는 이스라엘 정착민들에 대한 투표권과 팔레스타인 이웃 국가들에 대한 투표권 거부, 그리고 국가의 민족주의적 성격 때문에 의문이 제기되어 왔습니다.[427][428]

가자 지구는 이스라엘 법에 따라 '외국 영토'로 간주되며, 이스라엘은 이집트와 함께 가자 지구에 대한 육·공·해상 봉쇄를 운영하고 있습니다. 가자 지구는 1967년 이후 이스라엘에 의해 점령되었습니다. 2005년 이스라엘의 일방적인 이탈 계획의 일환으로 이스라엘은 정착민과 군대를 영토에서 철수시켰지만 영공과 해역에 대한 통제권을 계속 유지하고 있습니다. 수많은 국제 인도주의 단체들과 유엔 기구들을 포함한 국제 사회는 가자 지구를 점령한 채로 생각하고 있습니다.[429][430][431][432][433] 하마스가 가자지구에서 정권을 잡은 2007년 가자지구 전투 [434]이후 이스라엘은 해상과 항공은 물론 국경을 따라 있는 가자지구 횡단을 통제하고, 인도주의적이라고 판단되는 고립된 경우를 제외하고는 사람들의 출입을 막았습니다.[434] 가자 지구는 이집트와 국경을 접하고 있으며, 이스라엘, 유럽 연합, PA 간의 협정이 국경 통과가 어떻게 이루어지는지를 지배했습니다.[435] 팔레스타인 시민들에게 민주주의를 적용하고, 이스라엘이 지배하는 팔레스타인 영토에서 이스라엘 민주주의를 선택적으로 적용하는 것은 비판을 받아왔습니다.[436][437]

국제여론

국제사법재판소는 2004년 이스라엘 서안 장벽 건설의 적법성에 관한 자문의견에서 동예루살렘을 포함한 6일 전쟁에서 이스라엘이 점령한 토지는 점령지라고 밝혔고, 그리고 점령된 팔레스타인 영토 내에 장벽을 건설하는 것이 국제법에 위배된다는 것을 추가로 발견했습니다.[438] 영토와 관련된 대부분의 협상은 "전쟁에 의한 영토 획득의 불가항력"을 강조하고 아랍 국가들과의 관계 정상화에 대한 대가로 이스라엘이 점령된 영토에서 철수할 것을 요구하는 유엔 안전보장이사회 결의 242에 근거하고 있습니다.[439][440][441] 이스라엘은 점령지 자체를 포함한 점령지의 조직적이고 광범위한 인권 침해와 [442]민간인을 대상으로 한 전쟁 범죄에 연루돼 비난을 받아왔습니다.[443][444][445][446] 이 같은 주장에는 유엔 인권이사회의 국제인도법[447] 위반도 포함돼 있습니다.[448] 미 국무부는 이스라엘과[449] 점령지 내에서 팔레스타인인들의 중대한 인권 침해에 대한 보고를 '신뢰할 수 있다'고 말했습니다.[450] 국제앰네스티와 다른 비정부기구들은 팔레스타인의 자결권을 부정하는 것과 함께 대량의 자의적 체포, 고문, 불법적 살해, 조직적 학대, 불처벌[451][452][453][454][455][456] 등을 문서화했습니다.[457][458][459][460][461] 네타냐후 총리는 테러리스트들로부터[462] 무고한 사람들을 보호하는 국가의 보안군을 옹호하고 "범죄 살인자"들이 저지른 인권 침해에 대한 우려가 부족하다고 묘사하는 것에 대해 경멸을 표했습니다.[463]

국제사회는 점령지 내 이스라엘 정착촌을 국제법상 불법으로 간주하고 있습니다.[464] 하지만 유엔은 이스라엘에 대한 편견으로 비난을 받아왔습니다.[465][466] 유엔 안전보장이사회 결의 2334호(2016년 통과)는 이스라엘의 정착촌 활동이 국제법의 "명백한 위반"에 해당한다고 밝히고, 이스라엘이 그러한 활동을 중단하고 제4차 제네바 협약에 따른 점령국으로서의 의무를 이행할 것을 요구하고 있습니다.[467] 유엔 특별보고관은 정착 프로그램이 로마 법령에 따른 전쟁 범죄라고 결론지었고,[468] 국제앰네스티는 정착 프로그램이 "유괴"에 해당할 뿐만 아니라 민간인들을 점령지로 불법적으로 이동시키는 것에 해당한다고 밝혔습니다. 헤이그 협약과 제네바 협약에 의해 금지되어 있을 뿐만 아니라 로마 법령에 의해 전쟁 범죄로 규정되어 있습니다.[469]

아파르트헤이트에 대한 비난

점령지 내에서 팔레스타인인들을 대하는 이스라엘의 태도는 아파르트헤이트, 로마법과 아파르트헤이트 범죄의 억압과 처벌에 관한 국제협약에 따른 반인륜적 범죄라는 광범위한 비난을 불러왔습니다.[470][471] 2021년 중동에 대한 학계 전문가들을 대상으로 한 설문조사에 따르면 이스라엘을 "인종차별주의와 유사한 단일 국가 현실"로 묘사하는 학자들의 59%에서 65%로 증가했습니다.[472][473] 이 주장은 이스라엘 인권단체인 예쉬 딘과 브틀렘과 국제앰네스티, 휴먼라이츠워치 등 다른 국제 인권단체들에 의해 확인되었으며, 이에 대한 비판은 이스라엘 내 팔레스타인인들에 대한 처우에까지 확대되었습니다.[474][475] 앰네스티의 보고서는 이스라엘과 미국,[476] 영국,[477] 유럽연합 집행위원회,[478] 호주,[479] 네덜란드[480], 독일 등 동맹국들의 정치인과 대표들로부터 비판을 받았고,[481] 팔레스타인과 [482]다른 주들의 대표들,[which?] 그리고 아랍연맹과 같은 단체들로부터 비난을 환영받았다고 말했습니다.[483] 2022년, 유엔 인권 이사회에 의해 임명된 캐나다 법학 교수 마이클 린크는 상황이 아파르트헤이트의 법적 정의를 충족한다고 말했습니다.[484] 그의 후임자인 프란체스카 알바니즈와 이스라엘 팔레스타인 분쟁 의장 나비 필레이에 대한 유엔 상설 진상조사단의 후속 보고서도 이 같은 의견을 되풀이했습니다.[485][486]

대외관계

이스라엘은 유엔 164개 회원국과 교황청, 코소보, 쿡 제도, 니우에 등과 외교 관계를 유지하고 있습니다. 그곳에는 107개의 외교 공관이 있습니다;[487] 그들이 외교 관계가 없는 나라들은 대부분의 이슬람 국가들을 포함합니다.[488] 아랍연맹 22개국 중 6개국이 이스라엘과 관계를 정상화했습니다. 이스라엘은 공식적으로 시리아와 전쟁을 벌이고 있는데, 이 전쟁은 1948년으로 거슬러 올라갑니다. 레바논은 2000년 레바논 내전이 끝난 이후에도 유사한 공식적인 전쟁 상태를 유지하고 있으며, 이스라엘-레바논 국경은 조약에 의해 합의되지 않은 상태로 남아 있습니다.

이스라엘과 이집트의 평화협정에도 불구하고, 이스라엘은 이집트인들 사이에서 여전히 적국으로 널리 여겨지고 있습니다.[489] 이란은 이슬람 혁명 당시 이스라엘에 대한 인정을 철회했습니다.[490] 이스라엘 국민은 내무부의 허가 없이 시리아, 레바논, 이라크, 사우디아라비아, 예멘을 방문할 수 없습니다.[491] 2008-09년 가자 전쟁의 결과로 모리타니, 카타르, 볼리비아,[492] 베네수엘라는 이스라엘과의 정치적, 경제적 관계를 중단했지만 볼리비아는 2019년에 관계를 재개했습니다.[493]

미국과 소련은 거의 동시에 인정을 선언한 이스라엘 국가를 처음으로 인정한 두 나라였습니다.[494] 소련과의 외교 관계는 1967년 6일 전쟁 이후 단절되었고 1991년 10월에 재개되었습니다.[495] 미국은 "공동의 민주적 가치, 종교적 우호, 안보 이익"[496]을 바탕으로 이스라엘을 "중동에서 가장 신뢰할 수 있는 파트너"로 간주합니다.[497] 미국은 대외원조법(1962년 시작된 기간)에 따라 1967년부터 이스라엘에 680억 달러의 군사원조와 320억 달러의 보조금을 제공해 왔으며,[498] 이는 2003년까지 그 기간 동안 어느 나라보다도 많은 것입니다.[498][499][500] 설문에 응한 대부분의 미국인들은 또한 이스라엘에 대해 일관되게 호의적인 견해를 가지고 있습니다.[501][502] 영국은 팔레스타인 위임통치령 때문에 이스라엘과 "자연스러운" 관계를 맺고 있는 것으로 보입니다.[503] 2007년까지[update] 독일은 이스라엘 국가와 이스라엘 홀로코스트 생존자들에게 250억 유로의 배상금을 지불했습니다.[504] 이스라엘은 유럽 연합의 유럽 이웃 정책에 포함되어 있습니다.[505]

튀르키예와 이스라엘은 1991년까지 완전한 외교 관계를 맺지 못했지만, 튀르크 튀르키예는 1949년 이스라엘을 인정한 이후 유대 국가와 cooper했습니다. 튀르키예와 이 지역의 다른 이슬람교도 대다수 국가들의 관계는 때때로 아랍과 이슬람 국가들이 이스라엘과의 관계를 완화하도록 압력을 가하는 결과를 낳았습니다. 튀르키예와 이스라엘의 관계는 2008-09년 가자 전쟁과 이스라엘의 가자 함대 공습 이후 침체되었습니다. 그리스와 이스라엘의 관계는 1995년 이후 이스라엘의 쇠퇴로 인해 개선되었습니다.터키 관계.[509] 양국은 방위협력협정을 맺고 있으며, 2010년 이스라엘 공군이 그리스의 헬레닉 공군을 합동훈련으로 유치한 바 있습니다. 리바이어던 가스전을 중심으로 한 키프로스-이스라엘 공동 석유·가스 탐사는 키프로스와의 강한 연계성을 감안할 때 그리스에 중요한 요소입니다.[510] 세계에서 가장 긴 해저 전력 케이블인 유로아시아 인터커넥터의 협력은 키프로스-이스라엘 관계를 강화시켰습니다.[511]

아제르바이잔은 이스라엘과 전략적, 경제적 관계를 발전시킨 몇 안 되는 대다수 무슬림 국가 중 하나입니다.[409] 카자흐스탄은 또한 이스라엘과 경제적, 전략적 동반자 관계를 맺고 있습니다.[512] 인도는 1992년 이스라엘과 완전한 외교 관계를 수립했으며 그 이후로 이스라엘과 강력한 군사, 기술, 문화적 동반자 관계를 구축했습니다.[513] 인도는 이스라엘 군사 장비의 최대 고객국이고 이스라엘은 러시아 다음으로 인도의 두 번째로 큰 군사 파트너입니다.[514] 에티오피아는 공통의 정치적, 종교적, 안보적 이익 때문에 아프리카에서 이스라엘의 주요 동맹국입니다.[515]

대외원조

이스라엘은 전 세계적으로 재난에 대한 긴급 해외 원조와 인도주의적 대응을 제공한 역사를 가지고 있습니다.[516] 1955년 이스라엘은 버마에서 외국 원조 프로그램을 시작했습니다. 프로그램의 초점은 이후 아프리카로 옮겨졌습니다.[517] 이스라엘의 인도주의적 노력은 1957년 이스라엘의 국제개발협력기구인 마샤브가 설립되면서 공식적으로 시작되었습니다.[518] 이 초기에 이스라엘의 원조는 아프리카에 대한 전체 원조의 극히 일부에 불과했지만, 이스라엘의 프로그램은 호의를 창출하는 데 효과적이었습니다.[519] 그러나 1967년 전쟁 관계가 악화된 후. 이스라엘의 대외 원조 프로그램은 이후 라틴 아메리카로 초점을 옮겼습니다.[517] 1970년대 후반부터 이스라엘의 대외 원조는 점차 감소해 왔지만, 최근 몇 년 동안 이스라엘은 아프리카에 대한 원조를 다시 시작하려고 노력했습니다.[520] 이스라엘 단체들과 북미 유대인 단체들이 운영하는 공동 프로그램인 IsraAid,[521] ZAKA,[522] The Fast Israel Rescue and Search Team,[523] Israel Flight Aid,[524] Save a Child's Heart[525], Latet 등 이스라엘 정부와 협력하는 이스라엘 인도주의 및 긴급 대응 그룹이 추가로 있습니다.[526] 이스라엘은 1985년부터 2015년까지 IDF 수색구조대인 내무전선사령부의 24개 대표단을 22개국에 파견했습니다.[527] 현재 이스라엘의 대외 원조는 OECD 국가 중 낮은 순위를 차지하고 있으며, GNI의 0.1% 미만을 개발 원조에 지출하고 있습니다.[528] 이 나라는 2018년 세계 기부 지수에서 38위를 차지했습니다.[529]

군사의

이스라엘 방위군 (IDF)은 이스라엘 보안군의 유일한 군사 조직이며 내각에 종속된 총참모장 라마트칼이 이끌고 있습니다. IDF는 육군, 공군 및 해군으로 구성됩니다. 1948년 아랍-이스라엘 전쟁 중에 하가나를 중심으로 한 준군사조직을 통합하여 설립되었습니다.[530] IDF는 또한 군사 정보국(Aman)의 자원을 활용합니다.[531] IDF는 여러 주요 전쟁과 국경 분쟁에 관여하여 세계에서 가장 전투 훈련을 많이 받은 군대 중 하나입니다.[532]

대부분의 이스라엘인들은 18세에 징집됩니다. 남자는 2년 8개월, 여자는 2년간 복무합니다.[533] 의무 복무 후, 이스라엘 남성들은 예비군에 입대하여 보통 40대까지 매년 최대 몇 주의 예비군 임무를 수행합니다. 대부분의 여성들은 예비역 의무를 면제받습니다. 이스라엘의 아랍 시민들(드루제는 제외)과 전업 종교 연구에 종사하는 사람들은 면제되지만, 예시바 학생들의 면제는 논쟁의 대상이 되어 왔습니다.[534][535] 다양한 이유로 면제를 받는 사람들을 위한 대안은 사회 복지 체계에서 서비스 프로그램을 포함하는 국가 서비스인 Sherut Leumi입니다.[536] 소수의 이스라엘 아랍인들도 군대에 자원하고 있습니다.[537] IDF는 징병 프로그램의 결과로 약 176,500명의 현역 병력과 465,000명의 예비군을 유지하고 있으며, 이스라엘은 세계에서 가장 높은 비율의 군사 훈련을 받은 시민 중 한 명입니다.[538]

군은 일부 해외 수입품뿐만 아니라 이스라엘에서 설계되고 제조된 첨단 무기 시스템에 크게 의존하고 있습니다. 애로우 미사일은 세계에서 몇 안 되는 대탄도미사일 시스템 중 하나입니다.[539] 파이썬 공대공 미사일 시리즈는 종종 군사 역사상 가장 중요한 무기 중 하나로 여겨집니다.[540] 이스라엘의 스파이크 미사일은 세계에서 가장 널리 수출되는 대전차 유도 미사일 중 하나입니다.[541] 이스라엘의 아이언 돔 대 미사일 방공 시스템은 가자 지구에서 팔레스타인 무장세력이 발사한 수백 발의 로켓을 요격한 후 전 세계적인 찬사를 받았습니다.[542][543] 욤 키푸르 전쟁 이후 이스라엘은 정찰 위성 네트워크를 개발했습니다.[544] Oeq 프로그램은 이스라엘을 그러한 위성을 발사할 수 있는 7개국 중 하나로 만들었습니다.[545]

이스라엘은 핵무기를[546] 보유하고 있는 것으로 널리 알려져 있으며, 1993년 보고서에 따르면 화학 및 생물학적 대량살상무기를 보유하고 있다고 합니다.[547][needs update] 이스라엘은 핵무기[548] 비확산 조약에 서명하지 않았으며, 자국의 핵 능력에 대해 의도적으로 모호하다는 정책을 유지하고 있습니다.[549] 이스라엘 해군의 돌고래 잠수함은 두 번째 타격 능력을 제공하는 핵 미사일로 무장한 것으로 알려졌습니다.[550] 1991년 걸프전 이후, 이스라엘의 모든 가정은 화학적, 생물학적 물질에 불투과성이 있는 강화된 보안실인 Merkhav Mugan을 의무적으로 설치해야 합니다.[551]

이스라엘 건국 이후 군사비 지출은 이스라엘 국내총생산의 상당 부분을 차지했으며, 1975년 GDP의 30.3%를 정점으로 증가했습니다.[552] 2021년 이스라엘의 총 군사비 지출은 243억 달러로 세계 15위, GDP 대비 국방비 지출은 5.2%[553]로 6위를 기록했습니다. 1974년 이래로 미국은 특히 군사 원조의 중요한 기여자였습니다.[554] 2016년 체결된 양해각서에 따라 미국은 2018년부터 2028년까지 이스라엘 국방예산의 약 20%에 해당하는 연간 38억 달러를 지원할 것으로 예상됩니다.[555] 이스라엘은 2022년 무기 수출 세계 9위를 기록했습니다.[556] 이스라엘 무기 수출의 대부분은 안보상의 이유로 보고되지 않습니다.[557] 이스라엘은 2022년 세계 평화지수에서 163개국 중 134위로 지속적으로 낮은 평가를 받고 있습니다.[558]

경제.

이스라엘은 경제와 산업 발전에 있어 서아시아와 중동에서 가장 선진적인 나라로 평가받고 있습니다.[559][560] 2023년[update] 10월 기준, IMF는 이스라엘의 GDP를 5217억 달러, 이스라엘의 1인당 GDP를 53.2천 달러(세계 13위)로 추산했는데, 이는 다른 선진국과 부유한 나라들에 버금가는 수치입니다.[561] 이 나라는 1인당 명목 소득으로 아시아에서 세 번째로 부유한 나라입니다.[562] 이스라엘은 중동에서 성인 1인당 평균 재산이 가장 높습니다.[563] 이코노미스트지는 이스라엘을 2022년 선진국 중 4번째로 성공한 경제로 평가했습니다.[564] 중동에서 가장 많은 억만장자를 보유하고 있으며, 세계에서 18번째로 많은 억만장자를 보유하고 있습니다.[565] 최근 몇 년 동안 이스라엘은 선진국에서 가장 높은 성장률을 기록했습니다.[566] 2010년에는 OECD에 가입했습니다.[34][567] 이 나라는 세계 경제 포럼의 세계 경쟁력 보고서에서[568] 20위, 세계 은행의 기업하기 쉬운 지수에서 35위를 차지했습니다.[569] 이스라엘은 또한 고숙련 고용에서 차지하는 비중에서 세계 5위에 올랐습니다.[570] 이스라엘 경제 데이터는 골란고원, 동예루살렘, 요르단강 서안 이스라엘 정착촌 등 이스라엘의 경제 영토를 다루고 있습니다.[420]

제한된 천연 자원에도 불구하고 지난 수십 년 동안 농업과 산업 부문의 집중적인 개발은 이스라엘을 곡물과 쇠고기를 제외하고 식량 생산에서 대부분 자급자족하게 만들었습니다. 2020년 이스라엘에 대한 수입액은 원자재, 군사장비, 투자재, 러프다이아몬드, 연료, 곡물, 소비재 등 총 965억 달러입니다.[287] 주요 수출품으로는 기계 및 장비, 소프트웨어, 컷 다이아몬드, 농산물, 화학제품, 섬유 및 의류 등이 있으며, 2020년 이스라엘 수출액은 1,140억 달러에 달했습니다.[287] 이스라엘 은행은 세계에서 17번째로 높은 201억 달러의 외환 보유고를 보유하고 있습니다.[287] 이스라엘은 1970년대 이후 미국으로부터 군사원조를 받았고, 현재 이스라엘 대외채무의 약 절반을 차지하는 대출보증 형태의 경제원조를 받고 있습니다. 이스라엘은 선진국 중 대외채무가 가장 낮은 국가 중 하나이며, 2015년[update] 690억 달러의 흑자를 기록한 순외채(해외 부채 대비 자산) 측면에서 대주국입니다.[571]

이스라엘은 스타트업 기업이 미국 다음으로 많고 [572]나스닥 상장 기업이 세 번째로 많습니다.[573] 1인당 스타트업 수에서 세계 선두를 달리고 있습니다.[574] 이스라엘은 "스타트업 국가"로 불렸습니다.[575][576][577][578] 인텔과[579] 마이크로소프트는[580] 이스라엘에 첫 해외 연구개발 시설을 건설했고, 다른 첨단 다국적 기업들도 이스라엘에 연구개발 센터를 열었습니다.

이스라엘에서 근무 시간에 할당되는 날짜는 일요일부터 목요일까지(주 5일 근무의 경우) 또는 금요일부터(주 6일 근무의 경우)입니다. 금요일이 노동일이고 인구의 대다수가 유대인인 샤바트를 지키는 곳에서 금요일은 "짧은 날"입니다. 전 세계 대다수와 함께 근무 주를 조정하기 위한 몇 가지 제안이 제기되었습니다.[581]

과학기술

소프트웨어, 통신 및 생명과학 분야에서 이스라엘의 최첨단 기술 개발은 실리콘밸리와의 비교를 불러일으켰습니다.[582][583] 이스라엘은 GDP 대비 연구개발비 지출이 세계 1위입니다.[584] 2023년 글로벌 혁신지수 14위,[585] 2019년 블룸버그 혁신지수 5위입니다.[586] 이스라엘은 직원 1만 명당 140명의 과학자, 기술자, 기술자를 보유하고 있는데, 이는 세계에서 가장 많은 숫자입니다.[587][588][589] 이스라엘은 2004년부터[590] 6명의 노벨상 수상 과학자를 배출했으며, 1인당 과학 논문 비율이 가장 높은 국가 중 하나로 자주 선정되었습니다.[591][592][593] 이스라엘 대학은 컴퓨터 과학(Technion and Tel Aviv University), 수학(Hebrew University of Jeresal), 화학(Weizmann Institute of Science) 분야에서 세계 상위 50개 대학에 속합니다.[391]

2012년, 이스라엘은 Futron's Space Competitiveness Index에 의해 세계 9위에 올랐습니다.[594] 이스라엘 우주국은 모든 이스라엘 우주 연구 프로그램을 과학 및 상업적 목표와 조정하고 있으며, 적어도 13개의 상업, 연구 및 정찰 위성을 토착적으로 설계하고 건설했습니다.[595] 이스라엘의 위성 중 일부는 세계에서 가장 발전된 우주 시스템 중 하나입니다.[596] 샤빗은 이스라엘이 소형 위성을 지구 저궤도로 발사하기 위해 제작한 우주발사체입니다.[597] 1988년에 처음 발사되어 이스라엘은 우주 발사 능력을 갖춘 8번째 국가가 되었습니다. 2003년, 일란 라몬은 우주왕복선 컬럼비아호의 치명적인 임무를 수행하며 이스라엘의 첫 우주비행사가 되었습니다.[598]

계속되는 물 부족은 물 절약 기술의 혁신을 촉진했고, 이스라엘에서 상당한 농업 현대화인 점적 관개가 발명되었습니다. 이스라엘은 또한 담수화와 물 재활용의 기술적 최전선에 있습니다. 소렉 담수화 공장은 세계에서 가장 큰 해수 역삼투압 담수화 시설입니다.[599] 2014년까지 이스라엘의 담수화 프로그램은 이스라엘 식수의 약 35%를 공급했으며 2050년까지 70%를 공급할 것으로 예상됩니다.[600] 2015년[update] 기준으로 이스라엘 가정, 농업, 산업용 물의 50% 이상이 인공적으로 생산됩니다.[601] 2011년 이스라엘의 물 기술 산업은 연간 수천만 달러에 달하는 제품 및 서비스 수출로 연간 약 20억 달러의 가치를 지니고 있습니다. 역삼투압 기술의 혁신의 결과로 이스라엘은 물의 순 수출국이 될 예정입니다.[602]

이스라엘은 태양 에너지를 받아들였습니다. 이스라엘의 기술자들은 태양 에너지 기술의[604] 최첨단에 있고 태양 에너지 회사들은 전세계의 프로젝트를 수행하고 있습니다.[605][606] 이스라엘 가정의 90% 이상이 온수에 태양 에너지를 사용하는데, 이는 1인당 최고치입니다.[310][607] 정부 수치에 따르면, 이 나라는 난방에 태양 에너지를 사용하기 때문에 연간 전력 소비의 8%를 절약합니다.[608] 지리적 위도에서 높은 연간 입사 태양 광량은 네게브 사막에서 국제적으로 유명한 태양 연구 개발 산업에 이상적인 조건을 제공합니다.[604][605][606] 이스라엘은 전국적인 충전소 네트워크를 포함하는 현대적인 전기 자동차 인프라를 갖추고 있었습니다.[609][610][611] 하지만, 이스라엘의 전기 자동차 회사인 Better Place는 2013년에 문을 닫았습니다.[612]

에너지

이스라엘은 2004년부터 자국의 해상 가스전에서 천연가스를 생산하기 시작했습니다. 2009년, 이스라엘 해안 근처에서 천연 가스 보호 구역인 타마르가 발견되었습니다. 두 번째 보호 구역인 리바이어던은 2010년에 발견되었습니다.[613] 이 두 분야의 천연가스 매장량은 이스라엘을 50년 이상 에너지 안전하게 만들 수 있습니다. 2013년 이스라엘은 타마르 유전에서 천연가스를 상업적으로 생산하기 시작했습니다. 이스라엘은 2014년[update] 기준으로 연간 75억 입방미터(bcm) 이상의 천연가스를 생산하고 있습니다.[614] 이스라엘의 천연가스 매장량은 2016년 기준 199억 bcm로 입증되었습니다.[615] 리바이어던 가스전은 2019년부터 생산을 시작했습니다.[616]

케투라 선은 이스라엘 최초의 상업용 태양 전지입니다. 아라바 파워 컴퍼니가 2011년에 건설한 이 분야는 선텍이 만든 18,500개의 태양광 패널로 구성되어 있으며, 연간 약 9기가와트시(GWh)의 전기를 생산할 예정입니다.[617] 앞으로 20년 안에 이 분야는 약 125,000 미터톤의 이산화탄소 생산을 아끼지 않을 것입니다.[618]

운송

이스라엘은 19,224킬로미터(11,945마일)의 포장도로와 [619]300만 대의 자동차를 보유하고 있습니다.[620] 인구 1,000명당 자동차 대수는 365대로 선진국 중에서는 상대적으로 낮은 편입니다.[620] 이스라엘은 예정된 노선에 5,715대의 버스를 보유하고 있으며,[621] 여러 운송업체가 운영하고 있으며, 그 중 가장 크고 오래된 것은 에그드(Egged)로 대부분의 국가에 서비스를 제공합니다.[622] 철도는 1,277 킬로미터(793 마일)에 걸쳐 있으며 정부 소유의 이스라엘 철도에 의해 운영됩니다.[623] 1990년대 초부터 중반까지 대규모 투자를 시작한 후, 연간 열차 승객 수는 1990년 250만 명에서 2015년 5,300만 명으로 증가했습니다. 철도는 연간 750만 톤의 화물을 운송합니다.[623]

이스라엘은 3개의 국제 공항에서 서비스를 제공합니다. 벤구리온 공항, 라몬 공항, 하이파 공항. 이스라엘의 가장 큰 공항인 벤구리온은 2015년에 1,500만 명이 넘는 승객을 처리했습니다.[624] 이 나라는 3개의 주요 항구를 가지고 있습니다: 이 나라에서 가장 오래되고 큰 항구인 지중해 연안의 하이파 항구, 아쉬도 항구; 그리고 홍해의 더 작은 아일랏 항구.

관광업

관광, 특히 종교 관광은 이스라엘의 해변, 고고학적, 다른 역사적, 성경적 장소, 독특한 지리학도 관광객을 끌어들이는 중요한 산업입니다. 이스라엘의 안보 문제는 산업에 타격을 입혔지만 관광객 수는 반등하고 있습니다.[625] 2017년에는 기록적인 360만 명의 관광객이 이스라엘을 방문하여 2016년 이후 25% 성장했으며 이스라엘 경제에 200억 달러를 기여했습니다.[626][627][628][629]

부동산

이스라엘의 주택 가격은 모든 국가 중 상위 3분의 1에 속하며,[630] 아파트를 구입하는 데 평균 150명의 급여가 필요합니다.[631] 2022년 현재 이스라엘에는 약 270만 개의 부동산이 있으며 연간 5만 개 이상 증가하고 있습니다.[632] 하지만 주택 수요는 공급을 초과하여 2021년 기준 약 20만 가구의 아파트가 부족합니다.[633] 그 결과 2021년까지 주택 가격은 5.6%[634] 상승했습니다. 2021년 이스라엘인들은 2020년보다 50% 증가한 1,161억의 모기지를 기록했습니다.[635]

문화

이스라엘의 다양한 문화는 인구의 다양성에서 비롯됩니다. 전 세계 디아스포라 공동체의 유대인들은 그들의 문화적, 종교적 전통을 되살렸습니다.[636] 아랍의 영향은 건축,[638] 음악,[639] 요리와 [637]같은 많은 문화 영역에 존재합니다.[640] 이스라엘은 히브리 달력을 중심으로 삶이 돌아가는 유일한 나라입니다. 휴일은 유대인의 휴일에 의해 결정됩니다. 공식적인 안식일은 유대인의 안식일인 토요일입니다.[641]

문학.

이스라엘 문학은 주로 히브리어로 쓰여진 시와 산문이며, 19세기 중반 이후 구어로서의 히브리어 르네상스의 일환이지만, 소수의 문학이 다른 언어로 출판됩니다. 법적으로, 이스라엘에서 출판된 모든 인쇄물의 사본 2부는 이스라엘 국립 도서관에 보관되어야 합니다. 2001년에는 오디오 및 비디오 녹화 및 기타 비인쇄 매체를 포함하도록 법이 개정되었습니다.[642] 2016년, 도서관으로 옮겨진 7,300권의 책 중 89%가 히브리어로 되어 있었습니다.[643]

1966년 슈무엘 요세프 아그논은 독일의 유대인 작가 넬리 삭스와 노벨 문학상을 공동 수상했습니다.[644] 이스라엘의 대표적인 시인으로는 예후다 아미차이, 네이선 알터만, 레아 골드버그, 레이첼 블루스타인 등이 있습니다.[645] 국제적으로 유명한 현대 이스라엘 소설가로는 아모스 오즈, 에트가르 케렛, 데이비드 그로스먼 등이 있습니다.[646][647]

음악과 춤

이스라엘 음악에는 미즈라히와 세파르디 음악, 하시딕 멜로디, 그리스 음악, 재즈, 팝 록이 포함됩니다.[648][649] 이스라엘 필하모닉 오케스트라는[650][651] 70년 이상 운영되어 왔으며 매년 200회 이상의 콘서트를 개최합니다.[652] Itzhak Perlman, Pinchas Zukerman, Ofra Haza는 이스라엘에서 태어난 국제적으로 호평을 받고 있는 음악가들 중 한 명입니다. 이스라엘은 1973년부터 거의 매년 유로비전 송 콘테스트에 참가해 대회에서 4번 우승하고 2번 개최했습니다.[653][654] 에일랏은 1987년부터 매년 여름 자체적인 국제 음악 축제인 홍해 재즈 페스티벌을 개최하고 있습니다.[655] 그 나라의 표준 민요는 "이스라엘 땅의 노래"로 알려져 있습니다.[656]

영화와 극장

이스라엘 영화 10편이 아카데미 외국어영화상 최종 후보에 올랐습니다. 팔레스타인의 이스라엘 영화 제작자들은 모하메드 바크리의 2002년 영화 제닌, 제닌 그리고 시리아 신부와 같이 아랍과 이스라엘의 갈등과 이스라엘 내 팔레스타인인들의 지위를 다룬 영화들을 만들었습니다.

동유럽 이디시 극장의 강력한 연극 전통을 이어가는 이스라엘은 활기찬 극장 현장을 유지하고 있습니다. 1918년 설립된 텔아비브 하비마 극장은 이스라엘에서 가장 오래된 레퍼토리 극단이자 국립극장입니다.[657] 다른 극장으로는 오헬, 카메라, 게셔 등이 있습니다.[658][659]

예술

이스라엘의 유대인 예술은 특히 카발라, 탈무드, 조하르에 의해 영향을 받았습니다. 20세기에 중요한 역할을 한 또 다른 예술 운동은 파리 학파였습니다. 19세기 말에서 20세기 초, 이슈브의 예술은 베잘렐이 뿜어내는 예술 사조에 의해 지배되었습니다. 1920년대에 시작하여, 지역 예술계는 이삭 프렌켈 프렌켈이 처음 소개한 현대 프랑스 예술의 영향을 많이 받았습니다.[660][661] 수틴, 키코인, 프렌켈, 샤갈과 같은 파리 학파의 유대인 거장들은 이후 이스라엘 예술의 발전에 큰 영향을 미쳤습니다.[662][663] 이스라엘 조각은 메소포타미아, 아시리아, 그리고 지역 예술뿐만 아니라 현대 유럽 조각에서 영감을 얻었습니다.[664][665] 에이브러햄 멜니코프의 으르렁거리는 사자, 다비드 폴루스의 알렉산더 자이드, 제브 벤 즈비의 입체파 조각은 이스라엘 조각의 다른 흐름들 중 일부를 예시합니다.[664][666][667]

이스라엘 미술에서 흔히 볼 수 있는 주제는 신비로운 도시인 사페드와 예루살렘, 보헤미안 카페 문화인 텔아비브, 농업 풍경, 성경 이야기, 전쟁입니다. 오늘날 이스라엘 예술은 옵티컬 아트, AI 아트, 디지털 아트, 조각에 소금을 사용하는 것에 대해 탐구했습니다.[663]

건축

유대인 건축가들의 이주로 인해 이스라엘의 건축은 다양한 스타일을 반영하게 되었습니다. 20세기 초 유대인 건축가들은 옥시덴탈과 동양 건축을 결합하여 무수히 많은 양식을 보여주는 건축물을 생산하려고 했습니다.[668] 절충적 양식은 나치의 박해를 피해 독일 유대인 건축가들(에리히 멘델존 중)의 유입과 함께 모더니즘 바우하우스 양식에 자리를 내줬습니다.[669][670] 텔아비브 흰 도시는 유네스코의 문화유산입니다.[671] 독립 이후, 여러 정부 프로젝트가 의뢰되었는데, 이는 이스라엘의 사막 기후에 대한 콘크리트 사용과 순응에 중점을 두고 잔인한 스타일로 건설된 웅장한 부분입니다.[672][673]

가든 시티와 같은 몇 가지 새로운 아이디어가 이스라엘 도시에서 구현되었습니다. 텔아비브의 게데스 계획은 혁명적인 디자인과 지역 기후에 대한 적응으로 국제적으로 유명해졌습니다.[674] 키부짐의 디자인은 또한 리차드 카우프만의 원형 키부츠 나할랄의 계획과 같은 이념을 반영하게 되었습니다.[675]

미디어

프리덤 하우스의 2017년 언론자유 연례 보고서는 이스라엘을 중동과 북아프리카에서 가장 자유로운 나라, 그리고 세계적으로 64위로 선정했습니다.[676] 국경 없는 기자회의 2017년 언론자유 지수에서 이스라엘([677]2013년 이후 "이스라엘 치외법권" 포함)은 180개국 중 91위로 중동 및 북아프리카 지역에서 1위를 차지했습니다.[678] 국경 없는 기자회는 "팔레스타인 언론인들은 요르단강 서안에서 일어난 사건들을 취재한 결과 조직적으로 폭력의 대상이 되고 있다"고 지적했습니다.[679] 2001년 이후 50명 이상의 팔레스타인 기자들이 이스라엘에 의해 살해되었습니다.[680]

박물관

예루살렘에 있는 이스라엘 박물관은 이스라엘의 가장 중요한 문화 기관[681] 중 하나이며 유다와 유럽 예술의 광범위한 수집품과 [682]함께 사해 두루마리를 소장하고 있습니다.[681] 이스라엘의 국립 홀로코스트 박물관인 야드 바셈은 홀로코스트 관련 정보의 세계 중앙 보관소입니다.[683] 텔아비브 대학 캠퍼스에 있는 ANU - 유대인 박물관은 전 세계 유대인 공동체의 역사에 전념하는 상호작용적인 박물관입니다.[684]

이스라엘은 1인당 박물관 수가 가장 많습니다.[685] 예루살렘에 있는 록펠러 박물관과 L. A. 메이어 이슬람 예술 연구소를 포함한 여러 이스라엘 박물관이 이슬람 문화에 전념하고 있습니다. 록펠러는 중동 역사의 고고학 유적을 전문으로 합니다. 이곳은 또한 갈릴리 맨이라고 불리는 서아시아에서 발견된 최초의 인류 화석 두개골의 본거지이기도 합니다.[686]

요리.

이스라엘 요리에는 이민자들이 자국으로 가져온 유대인 요리뿐만 아니라 현지 요리도 포함됩니다. 특히 1970년대 후반부터 이스라엘 퓨전 요리가 발전했습니다.[687] 이스라엘 요리는 미즈라히, 세파르디 및 아슈케나지 스타일의 요리 요소를 채택했으며 계속해서 적응하고 있습니다. 팔라펠, 후무스, 샤크슈카, 쿠스쿠스, 자타르 등 레반틴, 아랍, 중동, 지중해 요리에서 전통적으로 먹는 많은 음식이 포함되어 있습니다. 슈니첼, 피자, 햄버거, 감자튀김, 쌀, 샐러드는 이스라엘에서 흔히 볼 수 있습니다.

이스라엘-유대인 인구의 약 절반이 집에서 코셔를 지키는 것을 지지합니다.[688][689] 2015년[update] 기준 코셔 레스토랑은 전체의 약 4분의 1을 차지합니다.[687] 돼지고기는[690] 비코셔 생선, 토끼, 타조류와 함께 생산되고 소비되지만 유대교와 이슬람교 모두 금지되어 있습니다.[691]

스포츠

이스라엘에서 가장 인기 있는 관중 스포츠는 협회 축구와 농구입니다.[692] 이스라엘 프리미어 리그는 이스라엘의 프리미어 축구 리그이고, 이스라엘 농구 프리미어 리그는 프리미어 농구 리그입니다.[693] 마카비 하이파, 마카비 텔아비브, 하포엘 텔아비브, 베이타르 예루살렘이 가장 큰 축구 클럽입니다. 마카비 텔아비브, 마카비 하이파, 하포엘 텔아비브는 UEFA 챔피언스리그에 출전했고 하포엘 텔아비브는 UEFA컵 8강에 올랐습니다. 이스라엘은 1964년 AFC 아시안컵을 개최하고 우승을 차지했으며, 1970년에는 이스라엘 축구 국가대표팀이 FIFA 월드컵에 참가한 유일한 국가였습니다. 1974년 테헤란에서 열린 아시안 게임은 이스라엘과 경쟁하기를 거부하는 아랍 국가들에 시달리며 이스라엘이 참가한 마지막 아시안 게임이었습니다. 이스라엘은 1978년 아시안 게임에서 제외되었고 그 이후로 아시안 스포츠 경기에 출전하지 않았습니다.[694] 1994년, UEFA는 이스라엘을 인정하기로 합의했고, 그 축구팀들은 현재 유럽에서 경쟁하고 있습니다. 마카비 텔아비브 B.C.는 유럽 농구 선수권 대회에서 6번 우승했습니다.[695]

이스라엘은 1992년 첫 우승 이후 2004년 하계 올림픽 윈드서핑 금메달을 포함하여 9개의 올림픽 메달을 획득했습니다.[696] 이스라엘은 패럴림픽에서 100개 이상의 금메달을 획득했고, 역대 메달 집계에서 20위를 차지하고 있습니다. 1968년 하계 패럴림픽은 이스라엘이 주최했습니다.[697] 유대인과 이스라엘 선수들을 위한 올림픽 형식의 대회인 마카비아 대회는 1930년대에 시작되었고, 그 이후로 4년마다 열립니다. 유럽의 파시즘에 맞서 싸우는 과정에서 유대인 게토파 수비수들이 개발한 무술인 크라브 마가는 이스라엘 보안군과 경찰에 의해 사용됩니다. 그것의 효과와 자기 방어에 대한 실용적인 접근 방식은 전 세계적으로 찬사와 고수를 받았습니다.[698]

체스는 이스라엘의 대표적인 스포츠입니다. 많은 이스라엘 그랜드 마스터들이 있고 이스라엘 체스 선수들은 많은 청소년 세계 선수권 대회에서 우승했습니다.[699] 이스라엘은 매년 국제 챔피언십을 개최하고 2005년에 세계 팀 체스 챔피언십을 개최했습니다. 교육부와 세계 체스 연맹은 이스라엘 학교 내에서 체스를 가르치는 프로젝트에 합의했고, 일부 학교의 교육 과정에 도입되었습니다.[700] 비에르셰바 시는 이 도시의 유치원에서 이 게임을 가르치면서 국립 체스 센터가 되었습니다. 부분적으로 소련의 이민 때문에, 이곳은 세계 어느 도시보다도 가장 많은 수의 체스 그랜드 마스터들의 본거지입니다.[701][702] 이스라엘 체스 팀은 2008년 체스 올림피아드에서[703] 은메달을 획득했고, 2010년 올림픽에서는 148개 팀 중 3위를 차지한 동메달을 획득했습니다. 이스라엘 그랜드 마스터 보리스 겔판드(Boris Gelfand)가 2009 체스 월드컵에서 우승했습니다.[704]

참고 항목

참고문헌

메모들

- ^ 다른 유엔 회원국의 인정: 러시아(서예루살렘),[1] 체코(서예루살렘),[2] 온두라스,[3] 과테말라,[4][6] 나우루,[5] 미국.

- ^ 예루살렘은 점령지로 널리 알려진 동예루살렘을 포함하면 이스라엘 최대의 도시입니다.[7] 동예루슬렘이 집계되지 않는다면 가장 큰 도시는 텔아비브가 될 것입니다.

- ^ 아랍어는 이전에 이스라엘의 공식 언어였습니다.[9] 2018년에 국가 기관에서 사용하는 '국가 내 특별 지위'로 분류가 변경되어 법률에 규정되었습니다.[10][11]

- ^ a b c d 이스라엘의 인구 및 경제 데이터는 골란 고원, 동예루살렘 및 요르단강 서안의 이스라엘 정착촌을 포함한 이스라엘의 경제 영토를 다룹니다.[420][421]

- '^이스라엘, (/ˈɪ zri.ə l, -re ɪ-/; 히브리어: יִשְׂרָאֵל y ī srá ʾē [jis ʁ a ˈʔel]; 아랍어: إِسْرَائِيل ʾ 이스라 ʾī), 공식적으로는 이스라엘의 국가(מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל 메드 ī 국가 ī ʾē ˈʔ [메디 ˈ 낫 지스 ʁ 아 ʾī 엘], دَوْلَة إِسْرَائِيل 다울라 이스라 ʾī),

- ^ 예루살렘 법은 "완전하고 연합된 예루살렘은 이스라엘의 수도"라고 명시하고 있으며, 이 도시는 대통령 관저, 관공서, 대법원, 의회가 있는 정부의 소재지 역할을 합니다. 유엔 안전보장이사회 결의 478호 (1980년 8월 20일; 14-0, 미국 기권)는 예루살렘 법을 "무효"로 선언하고 회원국들에게 예루살렘에서 그들의 공관을 철수할 것을 요구했습니다.[23] 자세한 내용은 예루살렘 현황을 참조하십시오.

- ^ "이스라엘"이라는 개인적인 이름은 에블라의 자료에서 훨씬 이전에 등장합니다.[56]

인용문

- ^ "Foreign Ministry statement regarding Palestinian-Israeli settlement". mid.ru. 6 April 2017. Archived from the original on 4 January 2020. Retrieved 15 December 2018.

- ^ "Czech Republic announces it recognizes West Jerusalem as Israel's capital". The Jerusalem Post. 6 December 2017. Archived from the original on 3 March 2020. Retrieved 6 December 2017.

The Czech Republic currently, before the peace between Israel and Palestine is signed, recognizes Jerusalem to be in fact the capital of Israel in the borders of the demarcation line from 1967." The Ministry also said that it would only consider relocating its embassy based on "results of negotiations.

- ^ "Honduras recognizes Jerusalem as Israel's capital". The Times of Israel. 29 August 2019. Archived from the original on 3 December 2019. Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- ^ "Guatemala se suma a EEUU y también trasladará su embajada en Israel a Jerusalén" [Guatemala joins US, will also move embassy to Jerusalem]. Infobae (in Spanish). 24 December 2017. Archived from the original on 17 April 2020. Retrieved 25 December 2017. 과테말라의 대사관은 1980년대 텔아비브로 옮겨지기 전까지 예루살렘에 있었습니다.

- ^ "Nauru recognizes J'lem as capital of Israel". Israel National News. 29 August 2019. Archived from the original on 11 June 2020. Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- ^ "Trump Recognizes Jerusalem as Israel's Capital and Orders U.S. Embassy to Move". The New York Times. 6 December 2017. Archived from the original on 17 June 2020. Retrieved 6 December 2017.

- ^ The Legal Status of East Jerusalem (PDF), Norwegian Refugee Council, December 2013, pp. 8, 29, archived (PDF) from the original on 10 May 2021, retrieved 26 October 2021

- ^ "Constitution for Israel". knesset.gov.il. Archived from the original on 4 August 2023. Retrieved 9 December 2023.

- ^ a b "Arabic in Israel: an official language and a cultural bridge". Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 18 December 2016. Archived from the original on 2 August 2020. Retrieved 8 August 2018.

- ^ a b "Israel Passes 'National Home' Law, Drawing Ire of Arabs". The New York Times. 19 July 2018. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 19 July 2018.

- ^ a b Lubell, Maayan (19 July 2018). "Israel adopts divisive Jewish nation-state law". Reuters. Archived from the original on 24 December 2018. Retrieved 19 July 2018.

- ^ a b Population of Israel on the Eve of 2023 (Report). Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. 29 December 2022. Archived from the original on 1 April 2023. Retrieved 29 December 2022.

- ^ "Israel". Central Intelligence Agency. 27 February 2023. Archived from the original on 10 January 2021. Retrieved 24 February 2023 – via CIA.gov.

- ^ "Israel country profile". BBC News. 24 February 2020. Archived from the original on 24 January 2021. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- ^ "Surface water and surface water change". OECD.Stat. OECD. Archived from the original on 24 March 2021. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- ^ "Home page". Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. Archived from the original on 1 April 2023. Retrieved 29 December 2022.

- ^ Population Census 2008 (PDF) (Report). Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. 2008. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 27 December 2016.

- ^ a b c d e "World Economic Outlook Database, October 2023 Edition. (Israel)". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. 10 October 2023. Archived from the original on 20 October 2023. Retrieved 11 October 2023.

- ^ "Income inequality". OECD Data. OECD. Archived from the original on 30 June 2020. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- ^ Nations, United (13 March 2024). Human Development Report 2023-24 (Report). United Nations.

- ^ "When will be the right time for Israel to define its borders? - analysis". The Jerusalem Post JPost.com. 12 June 2022.

- ^ 아크람, 수잔 M., 마이클 더머, 마이클 린크, 이안 스코비, eds. 2010. 국제법과 이스라엘-팔레스타인 분쟁: 중동 평화에 대한 권리 기반 접근법 루틀리지. 119쪽: "유엔 총회 결의 181호는 예루살렘에 10년 동안 유엔이 관리할 국제 구역, 즉 말뭉치 분리령을 만들 것을 권고했으며, 그 후 미래를 결정하기 위한 국민 투표가 있을 것입니다. 이 접근법은 동예루살렘과 동예루살렘에 똑같이 적용되며 1967년 동예루살렘 점령의 영향을 받지 않습니다. 국가들의 외교적 행동을 여전히 인도하고 따라서 국제법에서 더 큰 힘을 가지고 있는 것은 이러한 접근법입니다."

- ^ 켈러먼 1993, 페이지 140.

- ^ Righteous Victims: A History of the Zionist-Arab Conflict, 1881-2001: Morris, Benny: 9780679744757: Amazon.com: Books.

The fear of territorial displacement and dispossession was to be the chief motor of Arab antagonism to Zionism down to 1948 (and indeed after 1967 as well).

[영구 데드링크] - ^ "Zionism Definition, History, Examples, & Facts Britannica". britannica.com. 19 October 2023. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 29 October 2023.

- ^ 피쉬바흐 2008, 페이지 26-27.

- ^ Meir-Glitzenstein, Esther (Fall 2018). "Turning Points in the Historiography of Jewish Immigration from Arab Countries to Israel". Israel Studies. Indiana University Press. 23 (3): 114–122. doi:10.2979/israelstudies.23.3.15. JSTOR 10.2979/israelstudies.23.3.15. S2CID 150208821.

The mass immigration from Arab countries began in mid-1949 and included three communities that relocated to Israel almost in their entirety: 31,000 Jews from Libya, 50,000 from Yemen, and 125,000 from Iraq. Additional immigrants arrived from Egypt, Morocco, Tunisia, Turkey, Iran, India, and elsewhere. Within three years, the Jewish population of Israel doubled. The ethnic composition of the population shifted as well, as immigrants from Muslim counties and their offspring now comprised one third of the Jewish population—an unprecedented phenomenon in global immigration history. From 1952–60, Israel regulated and restricted immigration from Muslim countries with a selective immigration policy based on economic criteria, and sent these immigrants, most of whom were North African, to peripheral Israeli settlements. The selective immigration policy ended in 1961 when, following an agreement between Israel and Morocco, about 100,000 Jews immigrated to the State. From 1952–68 about 600,000 Jews arrived in Israel, three quarters of whom were from Arab countries and the remaining immigrants were largely from Eastern Europe. Today fewer than 30,000 remain in Muslim countries, mostly concentrated in Iran and Turkey.

- ^ a b "How Israel's electoral system works". CNN.com. CNN International. Retrieved 14 October 2021.

- ^ Nations, United (13 March 2024). Human Development Report 2023-24 (Report). United Nations.

- ^ "30 Countries with Highest GDP per Capita". Yahoo Finance. 23 March 2023. Archived from the original on 23 November 2023. Retrieved 23 November 2023.

- ^ "Global Wealth Report". Credit Suisse. Archived from the original on 18 July 2019. Retrieved 23 November 2023.

- ^ Team, FAIR (6 September 2023). "Top 10 Richest Countries in Asia [2023]". FAIR. Archived from the original on 20 November 2023. Retrieved 15 December 2023.

- ^ "Israel to join prestigious OECD economic club". France 24. 27 May 2010. Archived from the original on 23 November 2023. Retrieved 23 November 2023.

- ^ a b "Israel's accession to the OECD". oecd.org. OECD. Archived from the original on 16 May 2020. Retrieved 12 August 2012.

- ^ "Top 15 Most Advanced Countries in the World". Yahoo Finance. 4 December 2022. Archived from the original on 10 January 2023. Retrieved 27 October 2023.

- ^ Getzoff, Marc (9 August 2023). "Most Technologically Advanced Countries In The World 2023". Global Finance Magazine. Archived from the original on 8 November 2023. Retrieved 8 November 2023.

- ^ "Israel reveals population to reach 10 million by end of 2024". i24news.tv. 14 September 2023. Archived from the original on 24 October 2023. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ^ Noah Rayman (29 September 2014). "Mandatory Palestine: What It Was and Why It Matters". TIME. Archived from the original on 18 May 2019. Retrieved 5 December 2015.

- ^ "Popular Opinion". The Palestine Post. 7 December 1947. p. 1. Archived from the original on 15 August 2012.

- ^ 세상을 뒤흔든 어느 날 2012년 1월 12일 웨이백 머신 예루살렘 포스트에서 1998년 4월 30일 엘리 볼겔러너에 의해 아카이브되었습니다.

- ^ "On the Move". Time. 31 May 1948. Archived from the original on 16 October 2007. Retrieved 6 August 2007.

- ^ Levine, Robert A. (7 November 2000). "See Israel as a Jewish Nation-State, More or Less Democratic". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 22 July 2016. Retrieved 19 January 2011.

- ^ 제프리 W. 브로밀리, '이스라엘', 국제 표준 성경 백과사전: E-J, Wm. B. Eerdmans 출판사, 1995 p. 907.

- ^ Barton & Bowden 2004, p. 126. "Merneptah Stone... 기원전 13세기에 이스라엘의 존재에 대한 성경 밖의 가장 오래된 증거라고 할 수 있습니다."

- ^ Tchernov, Eitan (1988). "The Age of 'Ubeidiya Formation (Jordan Valley, Israel) and the Earliest Hominids in the Levant". Paléorient. 14 (2): 63–65. doi:10.3406/paleo.1988.4455.

- ^ Rincon, Paul (14 October 2015). "Fossil teeth place humans in Asia '20,000 years early'". BBC News. Archived from the original on 17 August 2017. Retrieved 4 January 2017.

- ^ Bar-Yosef, Ofer (7 December 1998). "The Natufian Culture in the Levant, Threshold to the Origins of Agriculture" (PDF). Evolutionary Anthropology. 6 (5): 159–177. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1520-6505(1998)6:5<159::AID-EVAN4>3.0.CO;2-7. S2CID 35814375. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 July 2021. Retrieved 4 January 2017.

- ^ Steiglitz, Robert (1992). "Migrations in the Ancient Near East". Anthropological Science. 3 (101): 263. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- ^ "Canaanites". obo. Archived from the original on 3 April 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Glassman, Ronald M. (2017), Glassman, Ronald M. (ed.), "The Political Structure of the Canaanite City-States: Monarchy and Merchant Oligarchy", The Origins of Democracy in Tribes, City-States and Nation-States, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 473–477, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-51695-0_49, ISBN 978-3-319-51695-0, retrieved 1 December 2023

- ^ Braunstein, Susan L. (2011). "The Meaning of Egyptian-Style Objects in the Late Bronze Cemeteries of Tell el-Farʿah (South)". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research. 364 (364): 1–36. doi:10.5615/bullamerschoorie.364.0001. JSTOR 10.5615/bullamerschoorie.364.0001. S2CID 164054005.

- ^ 디버, 윌리엄 G. 본문 너머, 성서문학회 출판부, 2017, pp. 89-93

- ^ S. Richard, "팔레스타인의 역사에 대한 고고학적 자료: 청동기 시대 초기: 도시주의의 흥망성쇠, 성서고고학자 (1987)

- ^ 고대의 K.L. 놀, 가나안과 이스라엘: 역사와 종교에 관한 교과서, A&C Black, 2012, rev. pp. 137ff.

- ^ 토마스 L. 톰슨, 이스라엘 민족의 초기 역사: 글과 고고학 출처, 브릴, 2000 pp. 275–276: '그들은 팔레스타인 인구 중에서 오히려 매우 특정한 집단이며, 팔레스타인 역사상 훨씬 나중 단계에서 실질적으로 다른 의미를 갖는 이름을 처음으로 가지고 있습니다.'

- ^ Hasel, Michael G. (1 January 1994). "Israel in the Merneptah Stela". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research. 296 (296): 45–61. doi:10.2307/1357179. JSTOR 1357179. S2CID 164052192.

* Bertman, Stephen (14 July 2005). Handbook to Life in Ancient Mesopotamia. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-518364-1.

* Meindert Dijkstra (2010). "Origins of Israel between history and ideology". In Becking, Bob; Grabbe, Lester (eds.). Between Evidence and Ideology Essays on the History of Ancient Israel read at the Joint Meeting of the Society for Old Testament Study and the Oud Testamentisch Werkgezelschap Lincoln, July 2009. Brill. p. 47. ISBN 978-90-04-18737-5.As a West Semitic personal name it existed long before it became a tribal or a geographical name. This is not without significance, though is it rarely mentioned. We learn of a maryanu named ysr"il (*Yi¡sr—a"ilu) from Ugarit living in the same period, but the name was already used a thousand years before in Ebla. The word Israel originated as a West Semitic personal name. One of the many names that developed into the name of the ancestor of a clan, of a tribe and finally of a people and a nation.

- ^ Lemche, Niels Peter (1998). The Israelites in History and Tradition. Westminster John Knox Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-664-22727-2.

- ^ Miller, James Maxwell; Hayes, John Haralson (1986). A History of Ancient Israel and Judah. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-21262-9.

- ^ "신의 초기 역사: 야훼와 고대 이스라엘의 다른 신들"에서 마크 스미스는 "가나안 사람들과 이스라엘 사람들이 근본적으로 다른 문화를 가진 사람들이라는 오랜 한탄 모델에도 불구하고 고고학적 데이터는 이제 이 견해에 의문을 던집니다. 이 지역의 물질 문화는 철 1기 (c. 1200–1000 BCE) 동안 이스라엘 사람들과 가나안 사람들 사이의 수많은 공통점을 보여줍니다. 이 기록은 이스라엘 문화가 가나안 문화와 크게 겹치고 그로부터 유래했다는 것을 암시합니다. 간단히 말해서, 이스라엘 문화는 본질적으로 가나안 민족이 대부분이었습니다. 이용 가능한 정보를 고려할 때, 가나안 사람들과 이스라엘 사람들 사이의 급격한 문화적 분리를 제1차 철기 동안 유지할 수 없습니다."(6-7쪽). 스미스, 마크 (2002) "신의 초기 역사: 야훼와 고대 이스라엘의 다른 신들" (에드만스)

- ^ 렌즈버그, 게리 (2008). "성경 없는 이스라엘" 프레드릭 E. 그린스판에서. 히브리어 성경: 새로운 통찰력과 장학금. 뉴욕대학교 출판부, 3-5페이지

- ^ Gnuse, Robert Karl (1997). No Other Gods: Emergent Monotheism in Israel. Sheffield Academic Press Ltd. pp. 28, 31. ISBN 978-1-85075-657-6.

- ^ Steiner, Richard C. (1997), "고대 히브리어", Hetzron, Robert (ed.), 셈족 언어, Routledge, pp. 145-173, ISBN 978-0-415-05767-7

- ^ 킬브루 2005, 페이지 230.

- ^ 샤힌 2005, 페이지 6.

- ^ Dever, William (2001). What Did the Biblical Writers Know, and When Did They Know It?. Eerdmans. pp. 98–99. ISBN 978-3-927120-37-2.

After a century of exhaustive investigation, all respectable archaeologists have given up hope of recovering any context that would make Abraham, Isaac, or Jacob credible "historical figures" [...] archaeological investigation of Moses and the Exodus has similarly been discarded as a fruitless pursuit.

- ^ 파우스트 2015, 476쪽: "성경에 묘사된 방식으로 출애굽기가 일어나지 않았다는 것에 학자들 사이에 일치된 의견이 있지만, 놀랍게도 대부분의 학자들은 이야기가 역사적 핵심을 가지고 있고, 어떤 고지대 정착민들이 이집트에서 어떤 식으로든 왔다는 것에 동의합니다."

- ^ Redmount 2001, p. 61: "몇몇 당국은 엑소더스 사가의 핵심 사건이 전적으로 문학적 조작이라고 결론 내렸습니다. 그러나 대부분의 성서학자들은 여전히 다큐멘터리 가설의 일부 변형을 지지하며 성서 서술의 기본적인 역사성을 지지합니다."

- ^ Dever, William (2001). What Did the Biblical Writers Know, and When Did They Know It?. Eerdmans. pp. 98–99. ISBN 978-3-927120-37-2.

After a century of exhaustive investigation, all respectable archaeologists have given up hope of recovering any context that would make Abraham, Isaac, or Jacob credible "historical figures" [...] archaeological investigation of Moses and the Exodus has similarly been discarded as a fruitless pursuit.

- ^ Lipschits, Oded (2014). "The History of Israel in the Biblical Period". In Berlin, Adele; Brettler, Marc Zvi (eds.). The Jewish Study Bible (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-997846-5. Archived from the original on 9 April 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2018.

- ^ Kuhrt, Amiele (1995). The Ancient Near East. Routledge. p. 438. ISBN 978-0-415-16762-8.

- ^ a b Finkelstein, Israel; Silberman, Neil Asher (2001). The Bible unearthed: archaeology's new vision of ancient Israel and the origin of its stories (1st Touchstone ed.). Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-684-86912-4.

- ^ Wright, Jacob L. (July 2014). "David, King of Judah (Not Israel)". The Bible and Interpretation. Archived from the original on 1 March 2021. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- ^ 핀켈슈타인, 이스라엘, (2020). "Benjamin의 Saul and Highlands 업데이트: "예루살렘의 역할", 요아힘 J. 크라우제, 오메르 세르기, 크리스틴 바인가르트(eds.), 사울, 베냐민, 그리고 이스라엘 군주제의 출현: 성경과 고고학적 관점, SBL Press, 애틀랜타, GA, p. 48, 각주: "...그들은 나중에 영토 왕국이 되었고, 기원전 9세기 전반에는 이스라엘, 후반에는 유다가 되었습니다.."

- ^ 투수가 고장났습니다: 고스타 W를 위한 기념 에세이. Hlstrom, Steven W. Holloway, Lowell K. Handy, Continuum, 1995년 5월 1일 Wayback Machine 인용문에서 2023년 4월 9일 보관: "이스라엘의 경우, 샬마네세르 3세(ninth 세기 중반)의 쿠르크 모놀리스에 있는 카르카르 전투에 대한 설명과 유다의 경우, 734년에서 733년 사이의 유다(IIR67 = K. 3751년)의 아하즈를 언급한 티글라스-필레세르 3세 본문이 현재까지 가장 오래된 것입니다."

- ^ Finkelstein & Silberman 2002, 146-7쪽: 간단히 말하면 유다가 여전히 경제적으로 소외되고 낙후된 반면 이스라엘은 호황을 누리고 있었습니다. ... 다음 장에서 우리는 어떻게 북방 왕국이 고대 근동 무대에서 갑자기 지역의 주요 강국으로 등장했는지 볼 것입니다.

- ^ Israel., Finkelstein. The forgotten kingdom: the archaeology and history of Northern Israel. p. 74. ISBN 978-1-58983-910-6. OCLC 949151323.

- ^ Finkelstein, Israel (2013). The Forgotten Kingdom: the archaeology and history of Northern Israel. pp. 65–66, 73, 78, 87–94. ISBN 978-1-58983-911-3. OCLC 880456140.

- ^ Finkelstein, Israel (1 November 2011). "Observations on the Layout of Iron Age Samaria". Tel Aviv. 38 (2): 194–207. doi:10.1179/033443511x13099584885303. ISSN 0334-4355. S2CID 128814117.

- ^ Broshi, Maguen (2001). Bread, Wine, Walls and Scrolls. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 174. ISBN 978-1-84127-201-6. Archived from the original on 10 February 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2018.

- ^ a b Broshi, M., & Finkelstein, I. (1992). "철기시대의 팔레스타인 인구 II" 2023년 3월 5일 웨이백 머신에 보관. 미국 동양 연구 학교 회보, 287(1), 47-60.

- ^ Finkelstein & Silberman 2002, p. 307: "예루살렘 전역에 걸친 집중적인 발굴은 이 도시가 실제로 바빌로니아인들에 의해 조직적으로 파괴됐다는 것을 보여주었습니다. 대화가 일반적이었던 것 같습니다. 페르시아 시대에 다윗 성 산등성이에서 활동이 재개되었을 때, 적어도 히스기야 때부터 번성했던 서쪽 언덕의 새로운 교외는 다시 점령되지 않았습니다.'

- ^ Lipschits, Oded (1999). "The History of the Benjamin Region under Babylonian Rule". Tel Aviv. 26 (2): 155–190. doi:10.1179/tav.1999.1999.2.155. ISSN 0334-4355.

- ^ Wheeler, P. (2017). "Review of the book Song of Exile: The Enduring Mystery of Psalm 137, by David W. Stowe". The Catholic Biblical Quarterly. 79 (4): 696–697. doi:10.1353/cbq.2017.0092. S2CID 171830838.

- ^ "British Museum – Cuneiform tablet with part of the Babylonian Chronicle (605–594 BCE)". Archived from the original on 30 October 2014. Retrieved 30 October 2014.

- ^ "ABC 5 (Jerusalem Chronicle) – Livius". livius.org. Archived from the original on 5 May 2019. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- ^ a b "Second Temple Period (538 BCE to 70 CE) Persian Rule". Biu.ac.il. Archived from the original on 16 January 1999. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- ^ 하퍼스 바이블 사전, Achtemeier 등에 의한, Harper & Row, San Francisco, 1985, p. 103

- ^ Grabbe, Lester L. (2004). A History of the Jews and Judaism in the Second Temple Period: Yehud – A History of the Persian Province of Judah v. 1. T & T Clark. p. 355. ISBN 978-0-567-08998-4. Archived from the original on 19 December 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2018.

- ^ Helyer, Larry R.; McDonald, Lee Martin (2013). "The Hasmoneans and the Hasmonean Era". In Green, Joel B.; McDonald, Lee Martin (eds.). The World of the New Testament: Cultural, Social, and Historical Contexts. Baker Academic. pp. 45–47. ISBN 978-0-8010-9861-1. OCLC 961153992.

The ensuing power struggle left Hyrcanus with a free hand in Judea, and he quickly reasserted Jewish sovereignty... Hyrcanus then engaged in a series of military campaigns aimed at territorial expansion. He first conquered areas in the Transjordan. He then turned his attention to Samaria, which had long separated Judea from the northern Jewish settlements in Lower Galilee. In the south, Adora and Marisa were conquered; (Aristobulus') primary accomplishment was annexing and Judaizing the region of Iturea, located between the Lebanon and Anti-Lebanon mountains

- ^ Ben-Sasson, H.H. (1976). A History of the Jewish People. Harvard University Press. p. 226. ISBN 978-0-674-39731-6.

The expansion of Hasmonean Judea took place gradually. Under Jonathan, Judea annexed southern Samaria and began to expand in the direction of the coast plain... The main ethnic changes were the work of John Hyrcanus... it was in his days and those of his son Aristobulus that the annexation of Idumea, Samaria and Galilee and the consolidation of Jewish settlement in Trans-Jordan was completed. Alexander Jannai, continuing the work of his predecessors, expanded Judean rule to the entire coastal plain, from the Carmel to the Egyptian border... and to additional areas in Trans-Jordan, including some of the Greek cities there.

- ^ Ben-Eliyahu, Eyal (30 April 2019). Identity and Territory: Jewish Perceptions of Space in Antiquity. Univ of California Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-520-29360-1. OCLC 1103519319.

From the beginning of the Second Temple period until the Muslim conquest—the land was part of imperial space. This was true from the early Persian period, as well as the time of Ptolemy and the Seleucids. The only exception was the Hasmonean Kingdom, with its sovereign Jewish rule—first over Judah and later, in Alexander Jannaeus's prime, extending to the coast, the north, and the eastern banks of the Jordan.

- ^ a b Schwartz, Seth (2014). The ancient Jews from Alexander to Muhammad. Cambridge University Press. pp. 85–86. ISBN 978-1-107-04127-1. OCLC 863044259.

The year 70 ce marked transformations in demography, politics, Jewish civic status, Palestinian and more general Jewish economic and social structures, Jewish religious life beyond the sacrificial cult, and even Roman politics and the topography of the city of Rome itself. [...] The Revolt's failure had, to begin with, a demographic impact on the Jews of Palestine; many died in battle and as a result of siege conditions, not only in Jerusalem. [...] As indicated above, the figures for captives are conceivably more reliable. If 97,000 is roughly correct as a total for the war, it would mean that a huge percentage of the population was removed from the country, or at the very least displaced from their homes. Nevertheless, only sixty years later, there was a large enough population in the Judaean countryside to stage a massively disruptive second rebellion; this one appears to have ended, in 135, with devastation and depopulation of the district.

- ^ 베르너 에크, "유대의 스클라벤과 프라이겔라센 폰 뢰메른과 데낭그렌젠덴 프로빈젠", 노붐 테스티넘 55 (2013): 1-21

- ^ Raviv, Dvir; Ben David, Chaim (2021). "Cassius Dio's figures for the demographic consequences of the Bar Kokhba War: Exaggeration or reliable account?". Journal of Roman Archaeology. 34 (2): 585–607. doi:10.1017/S1047759421000271. ISSN 1047-7594. S2CID 245512193.

Scholars have long doubted the historical accuracy of Cassius Dio's account of the consequences of the Bar Kokhba War (Roman History 69.14). According to this text, considered the most reliable literary source for the Second Jewish Revolt, the war encompassed all of Judea: the Romans destroyed 985 villages and 50 fortresses, and killed 580,000 rebels. This article reassesses Cassius Dio's figures by drawing on new evidence from excavations and surveys in Judea, Transjordan, and the Galilee. Three research methods are combined: an ethno-archaeological comparison with the settlement picture in the Ottoman Period, comparison with similar settlement studies in the Galilee, and an evaluation of settled sites from the Middle Roman Period (70–136 CE). The study demonstrates the potential contribution of the archaeological record to this issue and supports the view of Cassius Dio's demographic data as a reliable account, which he based on contemporaneous documentation.

- ^ a b c Mor, Menahem (18 April 2016). The Second Jewish Revolt. BRILL. pp. 483–484. doi:10.1163/9789004314634. ISBN 978-90-04-31463-4.

Land confiscation in Judaea was part of the suppression of the revolt policy of the Romans and punishment for the rebels. But the very claim that the sikarikon laws were annulled for settlement purposes seems to indicate that Jews continued to reside in Judaea even after the Second Revolt. There is no doubt that this area suffered the severest damage from the suppression of the revolt. Settlements in Judaea, such as Herodion and Bethar, had already been destroyed during the course of the revolt, and Jews were expelled from the districts of Gophna, Herodion, and Aqraba. However, it should not be claimed that the region of Judaea was completely destroyed. Jews continued to live in areas such as Lod (Lydda), south of the Hebron Mountain, and the coastal regions. In other areas of the Land of Israel that did not have any direct connection with the Second Revolt, no settlement changes can be identified as resulting from it.

- ^ 오펜하이머, 아하론과 오펜하이머, 닐리. 로마와 바빌론 사이: 유대인의 리더십과 사회에 관한 연구 모어 시벡, 2005, 페이지 2.

- ^ H.H. 벤-새슨, 유대인의 역사, 하버드 대학 출판부, 1976, ISBN 978-0-674-39731-6, 334 페이지: "유대인과 땅 사이의 유대에 대한 모든 기억을 없애기 위한 노력으로 하드리아누스는 유대인이 아닌 문학에서 흔한 이름인 시리아-팔레스티나로 지방의 이름을 바꿨습니다."

- ^ 아리엘 르윈. 고대 유대와 팔레스타인의 고고학. Getty Publications, 2005 p. 33. "헤로도토스의 글에서 이미 알려진 고대 지리적 실체(팔레스타인)의 되살아난 이름과 이웃 지방의 이름을 병치하는 중립적으로 보이는 이름을 선택함으로써 하드리아누스가 유대인들과 그 땅 사이의 연관성을 억누르려는 의도가 있었던 것은 분명해 보입니다." ISBN 978-0-89236-800-6

- ^ 에우세비우스, 기독교사. 4:6.3-4

- ^ a b Edward Kessler (2010). An Introduction to Jewish-Christian Relations. Cambridge University Press. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-521-70562-2.

Jews probably remained in the majority in Palestine until some time after the conversion of Constantine in the fourth century. [...] In Babylonia, there had been for many centuries a Jewish community which would have been further strengthened by those fleeing the aftermath of the Roman revolts.