공상과학소설

Science fiction

|

| 사변소설 |

|---|

| |

공상과학소설(SF) 또는 공상과학소설(SF)은 사변소설의 한 장르로, 일반적으로 첨단 과학기술, 우주 탐험, 시간 여행, 평행 우주, 외계 생명체 등 상상력이 풍부하고 미래지향적인 개념을 다루고 있습니다. 판타지, 공포, 슈퍼히어로 픽션과 관련이 있으며 많은 하위 장르를 포함하고 있습니다. 정확한 정의는 작가, 비평가, 학자 및 독자 사이에서 오랫동안 논쟁이 되어 왔습니다.

문학, 영화, 텔레비전 및 기타 미디어 분야의 SF는 세계의 많은 부분에서 인기와 영향력을 갖게 되었습니다. 그것은 "아이디어의 문학"이라고 불렸고, 때때로 과학적, 사회적, 기술적 혁신의[1][2] 잠재적 결과에 대한 탐구 또는 미래의 과학적, 기술적 혁신을 예측하는 배출구로 묘사되었습니다.[3] 엔터테인먼트를 제공하는 것 외에도 현대 사회를 비판하고 대안을 모색할 수 있습니다. 또한 종종 "경이감"을 불러일으킨다고 합니다.[4]

정의들

아이작 아시모프에 따르면, "과학소설은 과학과 기술의 변화에 대한 인간의 반응을 다루는 문학의 한 분야로 정의될 수 있습니다."[5] 로버트 A. 하인라인은 "거의 모든 공상 과학 소설에 대한 유용한 짧은 정의는 현실 세계, 과거와 현재에 대한 적절한 지식과 과학적 방법의 본질과 중요성에 대한 철저한 이해에 기초하여 가능한 미래 사건에 대한 현실적인 추측"이라고 썼습니다.[6]

미국의 공상과학소설 작가이자 편집자인 레스터 델 레이는 "열정적인 애호가나 팬조차도 공상과학소설이 무엇인지 설명하는 데 어려움을 겪는다"고 썼고, "완전한 만족스러운 정의"가 없는 것은 "과학소설에 쉽게 묘사되는 한계가 없기 때문"입니다.[7]

그것의 또 다른 정의는 DK의 문학서에서 나온 것으로, "기술적으로 불가능한, 오늘날의 과학에서 외삽한 시나리오들... [,]... 또는 어떤 형태의 사변적인 과학 기반 자만심을 다루는 시나리오들"입니다. (지구나 다른 행성에서) 우리와 전혀 다른 방식으로 발전한 사회와 같은 것입니다."[8]

과학소설에 대한 합의된 정의를 꼬집기가 그렇게 어려운 이유 중 일부는 과학소설 애호가들 사이에서 정확히 무엇이 과학소설을 구성하는지를 결정하는 데 자신의 중재자 역할을 하는 경향이 있기 때문입니다.[9] 데이먼 나이트(Damon Knight)는 "과학소설은 우리가 그것을 말할 때 가리키는 것입니다."라고 어려움을 요약했습니다.[10] 데이비드 시드는 공상과학소설을 다른, 보다 구체적인, 장르와 하위 장르의 교차점으로 이야기하는 것이 더 유용할 수 있다고 말합니다.[11]

대체항

Forres Jackerman 은 1954년경에 처음으로 "sci-fi" (당시 유행하던 "hi-fi"와 유사함)라는 용어를 사용한 것으로 알려져 있습니다.[12] 인쇄물에서 처음으로 알려진 사용은 1954년 1월 영화 평론가 Jesse Zunser가 도노반의 두뇌를 묘사한 것입니다.[13] SF가 대중문화에 진입하면서 작가들과 팬들은 이 용어를 저예산, 저기술의 "B-영화"와 저품질의 펄프 SF와 연관시키게 되었습니다.[14][15][16] 1970년대까지 데이먼 나이트나 테리 카와 같은 이 분야의 비평가들은 해킹 작업과 심각한 과학 소설을 구별하기 위해 "scifi"를 사용했습니다.[17] 피터 니콜스(Peter Nicholls)는 "SF" (또는 "sf")가 "SF 작가와 독자들의 공동체 내에서 선호되는 약어"라고 썼습니다.[18] 로버트 하인라인(Robert Heinlein)은 "과학 소설"조차도 이 장르의 특정 유형의 작품에는 충분하지 않다는 것을 발견하고, 더 "진지"하거나 "생각이 깊은" 작품에 대신 사변적인 소설이라는 용어를 사용할 것을 제안했습니다.[19]

역사

일부 학자들은 공상과학소설이 신화와 사실 사이의 경계가 모호했던 고대에 시작되었다고 주장합니다.[20] 풍자가 루시안이 서기 2세기에 쓴 트루 스토리는 다른 세계로의 여행, 외계 생명체, 행성 간의 전쟁, 그리고 인공 생명체를 포함한 현대 과학 소설의 특징적인 많은 주제와 트로피를 포함합니다. 어떤 사람들은 그것을 최초의 공상과학 소설이라고 생각합니다.[21] 아라비안 나이트에 나오는 이야기 [22][23]중에는 10세기 대나무 절단기[23] 이야기, 이븐 알 나피스의 13세기 신학자 아우토디닥투스 등과 함께 SF의 요소도 포함되어 있다고 주장되고 있습니다.[24]

과학혁명과 계몽주의 시대에 쓰여진 요하네스 케플러의 솜니움(1634), 프란시스 베이컨의 뉴 아틀란티스(1627),[25] 아타나시우스 키르허의 여행기(1656),[26] 시라노 드 베르게라크의 달의 국가와 제국의 희극사(1657), 태양의 국가와 제국(1662), 마가렛 캐번디시의 "불타는 세상" (1666),[27][28][29][30] 조나단 스위프트의 걸리버 여행 (1726), 루드비그 홀버그의 니콜라이 클리미 이터 지하공간 (1741), 볼테르의 마이크로메가스 (1752)는 때때로 최초의 진정한 과학 판타지 작품으로 여겨집니다.[31] 아이작 아시모프와 칼 세이건은 솜니움을 첫 번째 공상과학 이야기로 여겼습니다; 그것은 달로의 여행과 그곳에서 지구의 움직임을 어떻게 보는지를 묘사합니다.[32][33] 케플러는 "과학소설의 아버지"라고 불렸습니다.[34][35]

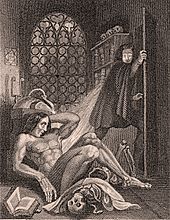

소설이 문학적 형태로 17세기에 발전한 후, 메리 셸리의 프랑켄슈타인 (1818)과 라스트 맨 (1826)은 SF 소설의 형태를 정의하는 데 도움을 주었습니다. 브라이언 알디스(Brian Aldiss)는 프랑켄슈타인(Frankenstein)이 SF의 첫 번째 작품이라고 주장했습니다.[36][37] 에드거 앨런 포(Edgar Allan Poe)는 달 여행을 특징으로 한 "한스 프팔의 비할 데 없는 모험"(1835)을 포함하여 공상과학소설로 여겨지는 여러 이야기를 썼습니다.[38][39] 쥘 베른(Jules Verne)은 특히 해저 2만 리그(1870)에서 세부 사항과 과학적 정확성에 주의를 기울인 것으로 유명했습니다.[40][41][42][43] 1887년, 스페인 작가 엔리케 가스파리 림바우의 소설 엘라나크로노페테가 최초의 타임머신을 소개했습니다.[44][45] 초기 프랑스/벨기에의 SF 작가는 J.-H. 로스니 아 î네(J.-H. Rosny a î네, 1856–1940)였습니다. 로시니의 걸작은 우주비행사라는 단어가 처음으로 사용된 '무한의 항해자들'(Les Naviguurs de l'Infini, 1925)입니다.[46][47]

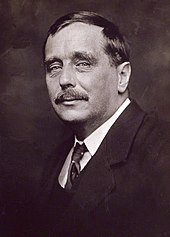

많은 비평가들은 H. G. 웰스를 SF의 가장 중요한 작가 [40][48]중 한 명으로 생각하거나 심지어 "과학 소설의 셰익스피어"로 생각합니다.[49] 그의 주목할 만한 과학 소설 작품으로는 타임머신 (1895), 모로 박사의 섬 (1896), 보이지 않는 사람 (1897), 그리고 세계 전쟁 (1898)이 있습니다. 그의 공상 과학 소설은 외계인의 침입, 생물 공학, 투명성, 그리고 시간 여행을 상상했습니다. 논픽션 미래학 작품에서 그는 비행기, 군사 탱크, 핵무기, 위성 텔레비전, 우주 여행, 그리고 월드 와이드 웹과 비슷한 것의 출현을 예측했습니다.[50]

1912년에 출판된 에드가 라이스 버로우즈의 "화성의 공주"는 화성을 배경으로 하고 존 카터가 주인공으로 등장한 그의 30년에 걸친 행성 로맨스 소설 시리즈 중 첫 번째였습니다.[51] 이 소설들은 YA 소설의 전신이었고, 유럽 SF와 미국 서양 소설에서 영감을 얻었습니다.[52]

1924년에는 최초의 디스토피아 소설 중 하나인 러시아 작가 Yevgeny Zamyatin의 We by Russian이 출판되었습니다.[53] 통일된 전체주의 국가 안에서 조화와 순응의 세계를 묘사합니다. 디스토피아가 문학 장르로 등장하는 데 영향을 미쳤습니다.[54]

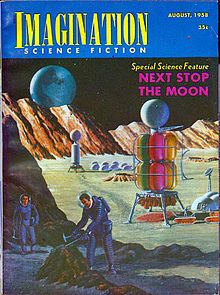

1926년, 휴고 건스백은 최초의 미국 공상과학 잡지인 어메이징 스토리를 출판했습니다. 그는 창간호에서 다음과 같이 썼습니다.

'과학적 상상'이란 과학적 사실과 예언적 비전이 뒤섞인 매력적인 로맨스인 쥘 베른, H.G. 웰스, 에드거 앨런 포의 이야기를 의미합니다. 이 놀라운 이야기들은 매우 흥미로운 읽기를 만들 뿐만 아니라 항상 교훈적입니다. 그들은 지식을 제공합니다... 아주 입맛에 맞는 형태로... 오늘의 과학에서 우리를 위해 그려지는 새로운 모험은 내일 실현이 전혀 불가능하지 않습니다. 역사적으로 중요한 많은 위대한 과학 이야기들이 아직도 쓰여질 예정입니다... 후세는 그들이 문학과 소설뿐만 아니라 진보에 있어서도 새로운 길을 개척했다고 지적할 것입니다.[55][56][57]

1928년, E. E. "Doc" Smith의 첫 번째 출판 작품인 The Skylark of Space는 Lee Hawkins Garby와 공동으로 쓰여진 놀라운 이야기들에 등장했습니다. 그것은 종종 최초의 위대한 우주 오페라라고 불립니다.[58] 같은 해 필립 프란시스 노울란의 원작 벅 로저스의 이야기 아마겟돈 2419도 어메이징 스토리에 등장했습니다. 그 뒤에 벅 로저스의 만화가 이어졌는데, 최초의 진지한 공상과학 만화였습니다.[59]

1937년 존 W. 캠벨(John W. Campbell)은 과학적 성취와 발전을 축하하는 이야기로 특징지어지는 과학 소설 황금기의 시작으로 간주되는 사건인 어스타운딩 사이언스 픽션(Astounding Science Fiction)의 편집자가 되었습니다.[60][61] 1942년, 아이작 아시모프는 은하 제국의 흥망성쇠를 기록하고 정신사를 소개하는 그의 파운데이션 시리즈를 시작했습니다.[62][63] 이 시리즈는 나중에 "역대 최고의 시리즈"로 휴고상을 한 번 수상했습니다.[64][65] 흔히 '황금시대'는 1946년에 끝났다고 하지만, 때로는 1940년대 후반과 1950년대가 포함되기도 합니다.[66]

Theodore Sturgeon의 More Than Human (1953)은 가능한 미래의 인간 진화를 탐구했습니다.[67][68][69] 1957년, 러시아 작가이자 고생물학자인 이반 예프레모프의 '안드로메다: 우주시대 이야기'는 미래의 성간 공산주의 문명에 대한 관점을 제시했고, 소련의 가장 중요한 공상과학 소설 중 하나로 여겨집니다.[70][71] 1959년 로버트 A. 하인라인의 스타쉽 트루퍼스(Starship Troopers)는 그의 초기 소년 시절 이야기와 소설에서 벗어났습니다.[72] 군사 공상 과학 소설의 최초이자 가장 영향력 있는 예 중 하나이며,[73][74] 동력 갑옷 외골격의 개념을 도입했습니다.[75][76][77] 다양한 작가들이 쓴 독일 우주 오페라 시리즈 페리 로단은 1961년 최초의 달 착륙에[78] 대한 설명으로 시작해 이후 우주를 여러 우주로, 그리고 시간적으로는 수십억 년까지 확장해 왔습니다.[79] 이 책은 역대 가장 인기 있는 공상과학 책 시리즈가 되었습니다.[80]

1960년대와 1970년대에 뉴웨이브 SF는 형식과 내용 모두에서 고도의 실험을 수용하고, 고상하고 자의식적인 "문학적" 또는 "예술적" 감성을 수용하는 것으로 유명했습니다.[81][82] 1961년에 폴란드에서 스타니스와프 렘의 솔라리스가 출판되었습니다.[83] 그 소설은 새로 발견된 행성에서 겉보기에는 지적으로 보이는 바다를 연구하려고 시도하면서 인간의 한계라는 주제를 다루었습니다.[84][85] 프랭크 허버트의 1965년 듄은 이전의 공상과학 소설보다 훨씬 더 복잡하고 상세하게 상상된 미래 사회를 특징으로 합니다.[86]

1967년 Anne McCaffrey는 그녀의 Dragonriders of Pern 과학 판타지 시리즈를 시작했습니다.[87] 첫 번째 소설인 Dragonflight에 포함된 두 편의 소설은 맥카프리가 휴고나 성운상을 수상한 첫 번째 여성이 되었습니다.[88] 1968년 필립 K. Dick's Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, 출판되었습니다. 블레이드 러너 영화 프랜차이즈의 문학적 출처입니다.[89][90] 1969년 우르술라 K의 어둠의 왼손. 르귄은 주민들이 정해진 성별이 없는 행성을 배경으로 삼았습니다. 사회과학소설, 페미니스트 과학소설, 인류학 과학소설의 가장 영향력 있는 사례 중 하나입니다.

1979년, 사이언스 픽션 월드는 중화인민공화국에서 출판을 시작했습니다.[94] 이 잡지는 중국 SF 잡지 시장을 장악하고 있으며, 한때 발행부수가 30만부에 달하며 한 부당 약 3-5명의 독자를 확보하여 (총 독자 수가 최소 100만 명으로 추산됨) 세계에서 가장 인기 있는 SF 잡지가 되었습니다.[95] 1984년, 윌리엄 깁슨의 첫 번째 소설인 뉴로맨서는 사이버펑크와 1982년 그의 단편 소설 버닝 크롬에서 처음 만들어진 용어인 "사이버스페이스"를 대중화하는 데 도움을 주었습니다.[96][97][98] 1986년 루이스 맥마스터 부졸드의 샤드 오브 아너는 그녀의 보르코시간 사가를 시작했습니다.[99][100] 닐 스티븐슨의 1992년 눈의 충돌은 정보 혁명으로 인해 엄청난 사회적 격변을 예측했습니다.[101]

2007년, 류시신의 소설 삼체 문제가 중국에서 출판되었습니다. 2014년 Ken Liu에 의해 영어로 번역되고 Tor Books에 의해 출판되었으며 [102]2015년 Hugo Award 최우수 소설상을 [103]수상하여 Liu는 아시아 작가로는 처음으로 이 상을 수상했습니다.[104]

20세기 말에서 21세기 초 사이에 등장하는 SF의 주제로는 환경 문제, 인터넷과 확장되는 정보 우주의 의미, 생명 공학, 나노 기술 및 포스트 희소 사회에 대한 질문 등이 있습니다.[105][106] 최근 트렌드 및 하위 장르에는 스팀펑크,[107] 바이오펑크 [108][109]및 일상적인 공상 과학 소설이 포함됩니다.[110][111]

영화

최초 혹은 적어도 최초로 기록된 공상과학 영화는 프랑스 영화 제작자 조르주 멜리에스가 감독한 1902년의 '달로의 여행'입니다.[112] 그것은 영화 매체에 다른 종류의 창조성과 환상을 가져오면서 후대의 영화 제작자들에게 지대한 영향을 미쳤습니다.[113][114] 또한 멜리에스의 혁신적인 편집과 특수효과 기법은 널리 모방되어 매체의 중요한 요소가 되었습니다.[115][116]

프리츠 랭이 감독한 1927년의 메트로폴리스는 첫 장편 SF 영화입니다.[117] 비록 그 시대에는 좋은 평가를 받지 못했지만,[118] 지금은 훌륭하고 영향력 있는 영화로 여겨집니다.[119][120][121] 1954년, 혼다 이시로 감독의 고질라는 어떤 형태로든 큰 생명체들이 등장하는 공상과학 영화의 카이주 하위 장르를 시작했는데, 보통 주요 도시를 공격하거나 다른 괴물들을 전투에 참여시킵니다.[122][123]

1968년 2001: 스페이스 오디세이, 스탠리 큐브릭 감독, 아서 C.의 작품을 바탕으로 제작되었습니다. 클라크는 그 당시까지 주로 B 영화를 제공하던 영화들을 뛰어넘어 범위와 품질 면에서 크게 영향을 미쳤고, 이후의 공상과학 영화에도 큰 영향을 미쳤습니다.[124][125][126][127] 같은 해 프랭클린 샤프너가 감독하고 피에르 불의 1963년 프랑스 소설 La Planète des Singes를 바탕으로 한 Planét of the Apees (원작)이 대중적이고 비평적인 찬사를 받으며 개봉되었는데, 이는 대부분 지능적인 유인원이 인간을 지배하는 종말론적인 세계를 생생하게 묘사했기 때문입니다.[128]

1977년, 조지 루카스는 현재 "스타워즈: 에피소드 4 – 새로운 희망"으로 확인된 영화로 스타워즈 영화 시리즈를 시작했습니다.[129] 종종 우주 오페라라고 불리는 이 시리즈는 [130]전 세계적인 대중 문화 현상이 되었고,[131][132] 역대 두 번째로 높은 수익을 올린 영화 시리즈가 되었습니다.[133]

1980년대 이후 공상과학 영화, 공포 영화, 슈퍼히어로 영화와 함께 할리우드의 대규모 예산 제작물을 장악했습니다.[134][133] 공상과학 영화는 종종 애니메이션(월-E – 2008, 빅 히어로 6 – 2014), 갱스터(스카이 라켓 – 1937), 웨스턴(세레니티 – 2005), 코미디(스페이스볼 – 1987, 갤럭시 퀘스트 – 1999), 전쟁(적 지뢰 – 1985), 액션(엣지 오브 투모로우 – 2014, 매트릭스 – 1999), 어드벤처(주피터 어센딩 – 2015) 등 다른 장르와 크로스오버를 합니다. Interstellar – 2014), sports (Rollerball – 1975), mystery (Minority Report – 2002), thriller (Ex Machina – 2014), horror (Alien – 1979), film noir (Blade Runner – 1982), superhero (Marvel Cinematic Universe – 2008–), drama (Melancholia – 2011, Predestination – 2014), and romance (Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind – 2004, Her – 2013).[135]

텔레비전

공상과학과 텔레비전은 지속적으로 긴밀한 관계를 유지해 왔습니다. 텔레비전 또는 텔레비전과 유사한 기술은 1940년대 말과 1950년대 초에 텔레비전 자체가 널리 보급되기 훨씬 전에 공상과학소설에 자주 등장했습니다.[136]

최초로 알려진 공상과학 텔레비전 프로그램은 1938년 2월 11일 BBC의 알렉산드라 팰리스 스튜디오에서 생중계된 체코 극작가 카렐 차펙(Karel Chapek)이 쓴 연극 RUR을 35분 동안 각색한 것이었습니다.[137] 미국 텔레비전에서 처음으로 인기 있는 공상과학 프로그램은 1949년 6월부터 1955년 4월까지 방영된 어린이 모험 시리즈 캡틴 비디오와 그의 비디오 레인저스였습니다.[138]

트와일라잇 존(원작 시리즈)은 1959년부터 1964년까지 대부분의 에피소드를 집필하거나 공동 집필한 로드 설링이 제작하고 내레이션을 맡았습니다. 공상과학뿐만 아니라 판타지, 서스펜스, 공포가 특징이며 각 에피소드는 완전한 이야기입니다.[139][140] 비평가들은 이 프로그램을 모든 장르 중 최고의 TV 프로그램 중 하나로 평가했습니다.[141][142]

만화 시리즈인 젯슨은 코미디로 의도되었고 단 한 시즌 (1962-1963) 동안만 방영되었지만 현재 일반적으로 사용되는 많은 발명품들을 예측했습니다: 평면 스크린 텔레비전, 컴퓨터 같은 화면의 신문, 컴퓨터 바이러스, 비디오 채팅, 태닝 침대, 가정용 러닝머신 등.[143] 1963년, 시간 여행을 주제로 한 닥터 후가 BBC TV에서 초연되었습니다.[144] 오리지널 시리즈는 1989년까지 방영되었고 2005년에 부활했습니다.[145] 전 세계적으로 엄청난 인기를 끌었고 이후 TV SF에도 큰 영향을 미쳤습니다.[146][147][148] 1960년대의 다른 프로그램들로는 우주 밖의 한계 (1963–1965),[149] 우주에서 길을 잃다 (1965–1968), 그리고 죄수 (1967)가 있습니다.[150][151][152]

진 로든베리(Gene Roddenberry)가 만든 스타 트렉(Star Trek, 오리지널 시리즈)은 1966년 NBC TV에서 초연되어 세 시즌 동안 방영되었습니다.[153] 우주 오페라와 스페이스 웨스턴의 요소를 결합했습니다.[154] 처음에는 약간의 성공을 거두었지만, 이 시리즈는 신디케이션과 남다른 팬들의 관심을 통해 인기를 얻었습니다. 많은 영화, 텔레비전 쇼, 소설 및 기타 작품 및 제품으로 매우 인기 있고 영향력 있는 프랜차이즈가 되었습니다.[155][156][157][158] 스타트랙: Next Generation (1987–1994)은 6개의 라이브 액션 Star Trek 쇼 (Deep Space 9 (1993–1999), Voyager (1995–2001), Enterprise (2001–2005), Discovery (2017–현재), Picard (2020–2023), Strange New Worlds (2022–현재)로 이어졌으며, 어떤 형태로든 더 많은 개발이 이루어졌습니다.[159][160][161][162]

미니시리즈 V는 1983년 NBC에서 초연되었습니다.[163] 그것은 파충류 외계인들에 의한 지구 탈취 시도를 묘사했습니다.[164] 1988년부터 1999년 사이에 BBC Two에서 방영된 만화 SF 시리즈인 Red Dwarf. 2009년부터 데이브에서 방영되었습니다.[165] UFO와 음모론이 등장한 X-파일은 크리스 카터가 만들고 폭스 방송사가 1993년부터 2002년까지,[166][167] 2016년부터 2018년까지 다시 방송했습니다.[168][169] 고대 우주비행사와 성간 순간이동에 관한 영화인 스타게이트는 1994년에 개봉했습니다. 스타게이트 SG-1은 1997년 초연되어 10시즌(1997-2007) 동안 진행되었습니다. 스핀오프 시리즈로는 스타게이트 인피니티(2002-2003), 스타게이트 아틀란티스(2004-2009), 스타게이트 유니버스(2009-2011)가 있습니다.[170] 다른 1990년대 시리즈로는 퀀텀 리프 (1989-1993)와 바빌론 5 (1994-1999)가 있습니다.[171]

1992년 The Sci-Fi Channel로 시작된 SyFy는 SF, 초자연적인 공포, 판타지를 전문으로 합니다.[172][173][174]

스페이스 웨스턴 시리즈 반딧불이는 2002년 폭스에서 초연되었습니다. 이 영화는 인간이 새로운 항성계에 도착한 후인 2517년을 배경으로 하며, "반딧불급" 우주선인 세레니티의 퇴역 대원들의 모험을 따릅니다.[175] Orphan Black은 유전적으로 동일한 인간 복제품 중 하나의 정체를 가정하는 한 여성에 대한 이야기로 2013년에 5시즌 동안 진행되었습니다. 2015년 말 SyFy는 인류의 태양계 식민지화에 관한 미국 TV 시리즈인 The Expans to the great critical aftery를 처음 선보였습니다. 이후 시즌은 아마존 프라임 비디오를 통해 방영될 예정입니다.

사회적 영향

이 섹션에는 특정 청중만 관심을 가질 수 있는 지나치게 많은 복잡한 세부 정보가 포함되어 있을 수 있습니다.하고에 수 사항을 바랍니다. (2024년 2월)(이를 에 대해 |

20세기 전반에 SF의 인기가 급상승한 것은 당시 과학에 대한 대중의 존경심과 기술 혁신과 새로운 발명의 빠른 속도와 밀접한 관련이 있었습니다.[176] 공상 과학 소설은 종종 과학과 기술의 진보를 예측해 왔습니다.[177][178] 어떤 작품들은 아서 C의 이야기와 같이 새로운 발명과 진보가 삶과 사회를 향상시키는 경향이 있을 것이라고 예측합니다. 클라크와 스타트랙.[179] H.G. 웰스의 타임머신과 알두스 헉슬리의 용감한 신세계와 같은 다른 이들은 가능한 부정적인 결과에 대해 경고합니다.[180][181]

2001년 국립과학재단은 "대중의 태도와 대중의 이해: 공상과학과 유사과학"에 대한 설문조사를 실시했습니다.[182] 과학소설을 읽거나 선호하는 사람들은 과학에 대해 다른 사람들과 다르게 생각하거나 관련시킬 수 있다는 것을 발견했습니다. 그들은 또한 우주 프로그램과 외계 문명과 접촉하는 아이디어를 지지하는 경향이 있습니다.[182][183] 칼 세이건(Carl Sagan)은 "태양계 탐사에 깊이 관여한 많은 과학자들이 (그들 중 나 자신이) SF에 의해 처음으로 그러한 방향으로 전환되었습니다."라고 썼습니다.[184]

SF는 상상의 세계에 몰입할 수 있도록 소설과 현실을 매끄럽게 혼합하려고 노력합니다. 여기에는 캐릭터, 설정 및 도구가 포함되며, 아마도 가장 중요한 것은 기술 및 기술 개념의 과학적 타당성 및 정확성입니다. 때때로 공상과학소설은 실제 혁신과 발견을 예측합니다. 공상과학소설은 원자폭탄,[185] 로봇,[186] 보라존과 같은 현존하는 여러 발명품을 예측했습니다.[187] 2020년 시리즈 어웨이에서 우주비행사들은 화성 착륙을 위해 집중적으로 듣기 위해 인사이트(InSight)라고 불리는 실제 화성 탐사 로봇을 사용합니다. 2년 후인 2022년에 과학자들은 실제 우주선의 착륙을 듣기 위해 Insight를 사용했습니다.[188] 쥬라기 공원 프랜차이즈에서 공룡은 고대 DNA로부터 만들어졌고 18년 후, 실제 과학자들은 고대 화석에서 공룡 DNA를 발견했습니다.

브라이언 알디스(Brian Aldis)는 공상과학소설을 "문화적 배경화면"이라고 표현했습니다.[189] 이러한 광범위한 영향력에 대한 증거는 작가들이 과학소설을 옹호하고 문화적 통찰력을 창출하는 도구로 사용하는 경향뿐만 아니라 자연과학에 국한되지 않은 다양한 학문 분야에서 가르칠 때 교육자들을 위한 경향에서 찾을 수 있습니다.[190] 학자이자 SF 평론가인 조지 에드거 슬러서는 "과학소설은 오늘날 우리가 가지고 있는 하나의 진정한 국제 문학 형태이며, 따라서 시각적 미디어, 대화형 미디어, 그리고 21세기에 세계가 발명할 어떤 새로운 미디어에도 확장되었습니다."라고 말했습니다. 과학과 인문학 간의 교차 문제는 앞으로 한 세기 동안 중요합니다."[191]

항의문학으로

과학소설은 때때로 사회적 항의의 수단으로 사용되어 왔습니다. 조지 오웰의 1984(1949)는 디스토피아 과학 소설의 중요한 작품입니다.[192][193] 그것은 종종 전체주의자로 여겨지는 정부와 지도자들에 대한 시위에서 발동됩니다.[194][195] 제임스 카메론(James Cameron)의 2009년 영화 아바타(Avata)는 제국주의, 특히 아메리카 대륙의 유럽 식민지화에 대한 항의를 위한 것이었습니다.[196]

적어도 셸리의 프랑켄슈타인이 출판된 이후 로봇, 인공 인간, 인간 복제품, 지능형 컴퓨터, 그리고 인간 사회와의 잠재적 갈등은 모두 SF의 주요 주제였습니다. 일부 비평가들은 이것이 현대 사회에서 볼 수 있는 사회적 소외에 대한 작가들의 우려를 반영하는 것으로 보고 있습니다.[197]

페미니스트 공상과학소설은 사회가 어떻게 성 역할을 구성하는지, 성을 정의하는 데 있어서 재생산이 어떤 역할을 하는지, 어떤 성이 다른 성에 대해 가지는 불평등한 정치적 또는 개인적 힘과 같은 사회적 문제에 대해 질문을 제기합니다. 이러한 주제를 유토피아를 이용하여 성차나 성차 권력 불균형이 존재하지 않는 사회를 탐구하거나, 디스토피아를 이용하여 성차 불평등이 심화되는 세계를 탐구하여 페미니스트 작업이 지속될 필요성을 주장한 작품도 있습니다.

기후 소설, 또는 "cli-fi"는 기후 변화와 지구 온난화에 관한 문제를 다룹니다.[200][201] 문학 및 환경 문제에 대한 대학 과정은 기후 변화 소설을 강의 계획서에 포함시킬 수 있으며,[202] 공상 과학 팬덤을 벗어난 다른 미디어에서 종종 논의됩니다.[203]

자유주의 SF는 개인주의와 사유재산, 경우에 따라 반국가주의에 중점을 두고 올바른 자유주의 철학에 의해 내포된 정치와 사회 질서에 초점을 둡니다.[204]

공상과학 코미디는 종종 현대 사회를 풍자하고 비판하며, 때때로 더 심각한 공상과학 소설의 관습과 진부한 말들을 비웃습니다.[205][206]

장르로서의 사이언스 픽션의 잠재력은 단순히 다른 세계의 서사를 탐구하는 문학적 샌드박스가 되는 것에 국한되지 않고 한 사회의 과거, 현재, 그리고 잠재적인 미래의 사회적 관계를 타자와 분석하고 인식하는 매개체 역할을 할 수 있습니다. 좀 더 구체적으로, 사이언스 픽션은 사회적 정체성의 차이와 대안의 매체와 표현을 제공합니다.[207]

경이감

공상과학소설은 종종 "경이감"을 불러일으킨다고 말합니다. 과학소설 편집자이자 출판인이자 비평가인 데이비드 하트웰은 다음과 같이 썼습니다. "과학소설의 매력은 이성적이고, 믿을 수 있는 것과 기적적인 것의 결합에 있습니다. 그것은 경이로움에 대한 호소력입니다."[208] 칼 세이건은 이렇게 말했습니다.

SF의 큰 장점 중 하나는 독자가 알 수 없거나 접근할 수 없는 지식을 단편적으로, 힌트와 어구로 전달할 수 있다는 것입니다. 욕조에서 물이 떨어지거나 초겨울 눈이 내리면서 숲 속을 걸을 때 고민하는 작품들입니다.[184]

1967년, 아이작 아시모프(Isaac Asimov)는 SF계에서 일어나고 있는 변화에 대해 다음과 같이 언급했습니다.

그리고 오늘의 현실이 어제의 환상과 너무나 닮아 있기 때문에 예전의 팬들은 안절부절못하고 있습니다. 인정하든 안하든 그 내면에는 외부 세계가 그들의 사적 영역을 침범했다는 실망감과 심지어 분노가 있습니다. 그들은 한때 '경이'에 진정으로 국한되었던 것이 이제는 프로사틱하고 일상적인 것이 되었기 때문에 '경이감'의 상실감을 느낍니다.[209]

공상과학 연구

SF학은 SF 문학, 영화, TV쇼, 뉴미디어, 팬덤, 팬픽션에 대한 비판적 평가, 해석, 토론입니다.[210] 과학소설 학자들은 과학소설과 과학, 기술, 정치, 다른 장르, 문화 전반과의 관계를 더 잘 이해하기 위해 과학소설을 연구합니다.[211] 공상과학 연구는 20세기에 접어들 무렵에 시작되었지만, 이후에야 학술지 Extrapolation(1959), Foundation: 과학소설에 대한 국제적 고찰(1972)과 과학소설 연구(1973)[214][215] [212][213]그리고 1970년 과학소설 연구에 전념한 가장 오래된 단체인 과학소설연구회와 과학소설재단의 설립. 이 분야는 1970년대 이후 더 많은 저널, 조직 및 컨퍼런스의 설립과 리버풀 대학에서 제공하는 것과 같은 공상과학 학위 부여 프로그램으로 상당히 성장했습니다.[216]

분류

과학소설은 역사적으로 하드 과학소설과 소프트 과학소설로 세분화되어 왔으며, 그 구분은 이야기의 중심이 되는 과학의 실현 가능성에 중점을 두고 있습니다.[217] 그러나 이 구분은 21세기에 들어 점점 더 정밀해지고 있습니다. Tade Thompson과 Jeff VanderMeer와 같은 일부 저자들은 명시적으로 물리학, 천문학, 수학 및 공학에 초점을 맞춘 이야기는 "딱딱한" 공상 과학 소설로 간주되는 경향이 있는 반면, 식물학, 균학, 동물학 및 사회 과학에 초점을 맞춘 이야기는 "부드러운"으로 분류되는 경향이 있다고 지적했습니다. 과학의 상대적 [218]엄격성에 관계없이

맥스 글래드스톤(Max Gladstone)은 "하드" 과학 소설을 "수학이 작동하는 곳"의 이야기로 정의했지만, 이것은 시간이 지남에 따라 과학 패러다임이 변화함에 따라 종종 "이상하게 오래된" 것처럼 보이는 이야기로 끝난다고 지적했습니다.[219] 마이클 스완윅(Michael Swanwick)은 "힘든" SF에 대한 전통적인 정의를 완전히 일축하고 대신 "올바른 방법으로 - 결단력, 약간의 금욕주의, 그리고 우주가 그들의 편이 아니라는 의식으로" 문제를 해결하기 위해 노력하는 캐릭터들에 의해 정의되었다고 말했습니다.[218]

우슐라 K. 르귄은 또한 "하드"와 "소프트" SF의 차이점에 대한 더 전통적인 견해를 비판했습니다: "'하드' SF 작가들은 물리학, 천문학, 그리고 아마도 화학을 제외하고는 모든 것을 일축합니다. 생물학, 사회학, 인류학 -- 그것은 그들에게 과학이 아니라 부드러운 것입니다. 그들은 인간이 하는 일에 그다지 관심이 없습니다, 정말로. 그러나 나는 그렇다. 저는 사회과학에 많은 관심을 갖고 있습니다."[220]

문학적 공덕

많은 비평가들은 공상 과학 소설과 다른 형태의 장르 소설의 문학적 가치에 대해 회의적인 시각을 가지고 있지만, 일부 인정된 작가들은 반대자들이 공상 과학 소설을 구성하기 위해 주장하는 작품을 썼습니다. 메리 셸리(Mary Shelley)는 고딕 문학 전통에서 프랑켄슈타인(Frankenstein) 또는 현대 프로메테우스(The Modern Prometeus, 1818)를 포함한 많은 과학 로맨스 소설을 썼습니다.[222] 커트 보니굿(Kurt Vonnegut)은 매우 존경 받는 미국 작가로, 그의 작품들은 일부 사람들에 의해 공상과학 소설의 전제나 주제를 포함한다고 주장되었습니다.[223][224] "심각한" 문학으로 널리 여겨지는 다른 공상과학 소설 작가로는 레이 브래드버리(특히 화씨 451(1953년)와 화성 연대기(1951년)가 있습니다.[225] 클라크와 [226][227]폴 마이런 앤서니 라인바거는 코드웨너 스미스라는 이름으로 글을 썼습니다.[228] 나중에 노벨 문학상을 수상한 도리스 레싱은 다섯 편의 SF 소설 시리즈인 카노푸스 인 아르고스를 썼습니다. 기록물(Archives, 1979–1983)은 지구상의 인간을 포함하여 덜 발달된 사람들에게 영향을 미치기 위한 더 발달된 종과 문명의 노력을 묘사합니다.[229][230][231][232]

데이비드 바넷(David Barnett)은 코맥 매카시(Cormac McCarthy)의 '길'(2006), 데이비드 미첼(David Mitchell)의 '클라우드 아틀라스'(2004), 닉 하커웨이(Nick Harkaway)의 '사라진 세상'(2008), 지넷 윈터슨(Jinette Winterson)의 '돌의 신'(2007), 마거릿 애트우드(Margaret Atwood)의 '오릭스와 크레이크(2003)'와 같은 책들이 있다고 지적했습니다. 하지만 그들의 작가들과 출판사들에 의해 공상과학소설로 분류되지 않습니다.[233] 특히 애트우드는 하녀의 이야기와 같은 작품들을 공상과학소설로 분류하는 것에 반대하며, 오릭스와 고증인을 사변적인 소설로[234] 분류하고 공상과학소설을 "우주 공간에서 말하는 오징어"로 조롱했습니다.[235] 문학평론가 해럴드 블룸은 저서 《서부의 정전》에서 용감한 신세계, 스타니스와프 렘의 솔라리스, 쿠르트 본네굿의 고양이 요람, 어둠의 왼손을 문화적, 미학적으로 중요한 서양문학 작품으로 꼽고 있습니다. 비록 렘이 적극적으로 "과학 소설"[236]이라는 서구의 꼬리표를 던졌지만, 본네굿은 더 일반적으로 포스트모더니즘이나 풍자주의자로 분류되었습니다.

1976년 그녀의 에세이 "사이언스 픽션과 브라운 부인"에서 우르술라 K. 르귄은 질문을 받았습니다: "과학 소설가가 소설을 쓸 수 있나요?" 그녀는 이렇게 대답했습니다. "저는 모든 소설이... 인성을 다루고, 인성을 표현하기 위한 것입니다 – 교리를 설교하거나 노래를 부르는 것이 아닙니다... 소설의 형태가 그렇게 서툴고 장황하고 극적이지 않으며, 그렇게 풍부하고 탄력적이며 살아있는 형태로 진화되어 왔다는 것을... 위대한 소설가들은 우리가 어떤 인물을 통해 보고 싶어하는 것을 보게 했습니다. 그렇지 않으면 그들은 소설가가 아니라 시인, 역사가, 팜플렛 판매자가 될 것입니다."[237] 1985년 그의 공상과학 소설 엔더스 게임으로 가장 잘 알려진 오슨 스콧 카드는 공상과학에서 그 작품의 메시지와 지적인 의미가 이야기 그 자체에 포함되어 있기 때문에 스타일리시한 속임수나 문학적인 게임이 필요하지 않다고 가정했습니다.[238][239]

조나단 레템(Jonathan Lemhem)은 1998년 빌리지 보이스(Village Voice)에서 "가까운 만남: 공상과학소설의 방탕한 약속'은 1973년 토머스 핀촌의 중력 레인보우가 성운상 후보에 오르고 클라크의 라마와의 랑데부에 유리하게 넘어간 지점이 "SF가 주류와 합병되려 했던 희망의 죽음을 알리는 숨겨진 묘비"로 서 있다고 제안했습니다.[240] 같은 해에 SF 작가이자 물리학자인 그레고리 벤포드는 다음과 같이 썼습니다: "SF는 아마도 20세기의 정의적인 장르일 것이지만, 정복한 군대는 여전히 문학 도시의 로마 밖에 주둔하고 있습니다."[241]

지역 사회

작가들

SF는 전 세계의 다양한 작가들에 의해 쓰여지고 있고 쓰여지고 있습니다. SF 출판사 토르 북스의 2013년 통계에 따르면 출판사에 제출한 자료 중 남성이 여성보다 78%에서 22% 더 많습니다.[242] 2015년 휴고 어워드의 투표 결과에 대한 논란은 점점 더 다양한 작품과 작가들이 수상의 영예를 안는 경향과 그들이 더 "전통적인" 공상과학소설을 선호하는 작가와 팬들의 반응 사이의 SF계의 긴장을 강조했습니다.[243]

시상식

가장 중요하고 잘 알려진 공상 과학 상 중에는 월드콘에서 세계 공상 과학 협회가 수여하고 팬들이 투표한 휴고 문학상이 있습니다.[244] 미국 공상 과학 작가들이 수여하는 성운 문학상, 그리고 작가 커뮤니티에 의해 투표되었습니다;[245] 작가 심사위원단이 수여하는 최고의 SF 소설에 대한 존 W. 캠벨 기념상;[246] 그리고 단편 소설에 대한 시어도어 스터전 기념상.[247] 공상과학 영화와 TV 프로그램에서 주목할 만한 상 중 하나는 The Academy of Science Fiction, Fantasy, and Horror Films에 의해 매년 수여되는 Saturn Award입니다.[248]

캐나다의 Prix Aurora Awards와 같은 다른 국가적인 상들,[249] 미국 북서 태평양의 작품들을 위해 Orycon에서 수여되는 Endefour Award와 같은 지역적인 상들,[250] 그리고 Science Fiction & Fantasy Artists 협회가 수여하는 Chesley Award for Art와 같은 특별한 관심이나 하위 장르의 상들이 있습니다.[251] 아니면 세계 판타지상을 수상할 수도 있고요.[252] 잡지는 독자 여론 조사, 특히 로커스 상을 조직할 수 있습니다.[253]

관습

(팬덤에서, 종종 "코믹콘"과 같이 "콘"으로 줄여서 부르는) 컨벤션은 지역, 지역, 국가 또는 국제 회원 자격을 충족시키는 전 세계 도시에서 열립니다.[254][52][255] 일반 이익 협약은 공상 과학 소설의 모든 측면을 다루지만, 다른 것들은 미디어 팬덤, 필킹 등과 같은 특정 관심사에 초점을 맞춥니다.[256][257] 대부분의 SF 컨벤션은 비영리 단체의 자원봉사자들에 의해 조직되지만 대부분의 미디어 지향 행사는 상업적인 홍보자들에 의해 조직됩니다.[258]

팬덤과 팬진

어메이징 스토리 잡지의 편지란에서 SF 팬덤이 등장했습니다. 곧 팬들은 서로에게 편지를 쓰기 시작했고, 그리고 나서 팬진이라고 알려지게 된 비공식적인 출판물에서 그들의 의견을 함께 묶기 시작했습니다.[259] 일단 정기적으로 연락을 취하면 팬들은 서로 만나기를 원했고 지역 클럽을 조직했습니다.[259][260] 1930년대에, 최초의 공상과학 컨벤션은 더 넓은 지역의 팬들을 모았습니다.[260]

초기에 조직된 온라인 팬덤은 SF 러버즈 커뮤니티(SF Lovers Community)였으며, 원래 1970년대 후반에 정기적으로 업데이트되는 텍스트 아카이브 파일이 있는 메일링 목록이었습니다.[261] 1980년대에 유즈넷 그룹은 온라인에서 팬들의 범위를 크게 넓혔습니다.[262] 1990년대에 월드 와이드 웹의 발전은 온라인 팬덤의 커뮤니티를 몇 배로 폭발시켰고, 수천 개의 웹사이트와 수백만 개의 웹사이트가 모든 미디어를 위한 공상과학 및 관련 장르에 전념했습니다.[263]

최초의 공상과학 팬진인 혜성은 1930년 일리노이주 시카고의 과학 통신 클럽에 의해 출판되었습니다.[264][265] 오늘날 가장 잘 알려진 팬진 중 하나는 앤서블(Ansible)인데, 수많은 휴고상 수상자인 데이비드 랭포드(David Langford)가 편집했습니다.[266][267] 하나 이상의 휴고 상을 수상한 다른 주목할 만한 팬진으로는 파일 770, 미모사, 플로카 등이 있습니다.[268] 브래드 W를 포함한 팬진에서 일하는 예술가들은 자주 이 분야에서 두각을 나타냈습니다. 포스터(Foster), 테디 하비아(Teddy Harvia), 조 메이휴(Joe Mayhew); 휴고(Hugos)는 최고의 팬 아티스트 부문을 포함합니다.[268]

요소들

공상과학 요소는 다음과 같은 것들을 포함할 수 있습니다.

- 미래의 시간적 설정 또는 대체 이력[269]

- 우주 여행, 우주 공간, 다른 세계, 지하 지구 [270]또는 평행 우주에서의[271] 설정

- 외계인, 돌연변이, 강화된 인간[272][273] 등 소설 속 생물학적 측면

- 뇌-컴퓨터 인터페이스, 생체공학, 초지능형 컴퓨터, 로봇, 광선총 등 예측되거나 추측되는 기술 및 기타 첨단 무기[272][274]

- 순간이동, 시간여행, 빛보다 빠른 여행이나 통신과[275] 같은 아직 발견되지 않은 과학적 가능성

- 유토피아적,[270] 디스토피아적, 포스트 아포칼립틱 또는 포스트[276] 희소성을 포함한 새롭고 다양한 정치적, 사회적 시스템 및 상황

- 지구나 다른 행성에서[277] 인간의 미래 역사와 진화

- 마인드 컨트롤, 텔레파시, 텔레키네시스와[278] 같은 초자연적인 능력

국제적인 사례

하위 장르

관련장르

참고 항목

참고문헌

- ^ Marg Gilks; Paula Fleming & Moira Allen (2003). "Science Fiction: The Literature of Ideas". WritingWorld.com. Archived from the original on 15 May 2015. Retrieved 22 December 2006.

- ^ von Thorn, Alexander (August 2002), Aurora Award acceptance speech, Calgary, Alberta

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: 위치 누락 게시자(링크) - ^ Michaud, Thomas; Appio, Francesco Paolo (12 January 2022). "Envisioning innovation opportunities through science fiction". Journal of Product Innovation Management. 39 (2): 121–131. doi:10.1111/jpim.12613. ISSN 0737-6782.

- ^ 프루처, 제프(ed. 용감한 신조어: 옥스퍼드 과학소설사전(옥스퍼드대 출판부, 2007) 179페이지

- ^ 아시모프, "미래를 얼마나 쉽게 볼 수 있는가!", 자연사, 1975

- ^ Heinlein, Robert A.; Cyril Kornbluth; Alfred Bester; Robert Bloch (1959). The Science Fiction Novel: Imagination and Social Criticism. University of Chicago: Advent Publishers.

- ^ Del Rey, Lester (1980). The World of Science Fiction 1926–1976. Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-345-25452-8.

- ^ Canton, James; Cleary, Helen; Kramer, Ann; Laxby, Robin; Loxley, Diana; Ripley, Esther; Todd, Megan; Shaghar, Hila; Valente, Alex; et al. (Authors) (2016). The Literature Book (First American ed.). New York: DK. p. 343. ISBN 978-1-4654-2988-9.

- ^ Menadue, Christopher Benjamin; Giselsson, Kristi; Guez, David (1 October 2020). "An Empirical Revision of the Definition of Science Fiction: It Is All in the Techne . . ". SAGE Open. 10 (4): 2158244020963057. doi:10.1177/2158244020963057. ISSN 2158-2440. S2CID 226192105.

- ^ Knight, Damon Francis (1967). In Search of Wonder: Essays on Modern Science Fiction. Advent Publishing. p. xiii. ISBN 978-0-911682-31-1.

- ^ Seed, David (23 June 2011). Science Fiction: A Very Short Introduction. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-955745-5.

- ^ "Forrest J Ackerman, 92; Coined the Term 'Sci-Fi'". The Washington Post. 7 December 2008. Archived from the original on 22 October 2017. Retrieved 17 December 2015.

- ^ "sci-fi n." Historical Dictionary of Science Fiction. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ^ Whittier, Terry (1987). Neo-Fan's Guidebook.[전체 인용 필요]

- ^ Scalzi, John (2005). The Rough Guide to Sci-Fi Movies. Rough Guides. ISBN 9781843535201. Archived from the original on 2 April 2009. Retrieved 17 January 2007.

- ^ Ellison, Harlan (1998). "Harlan Ellison's responses to online fan questions at ParCon". Archived from the original on 22 May 2015. Retrieved 26 April 2006.

- ^ Clute, John (1993). ""Sci fi" (article by Peter Nicholls)". In Nicholls, Peter (ed.). Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Orbit/Time Warner Book Group UK.

- ^ Clute, John (1993). ""SF" (article by Peter Nicholls)". In Nicholls, Peter (ed.). Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Orbit/Time Warner Book Group UK.

- ^ "Sci-Fi Icon Robert Heinlein Lists 5 Essential Rules for Making a Living as a Writer". Open Culture. 29 September 2016. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ "Out of This World". www.news.gatech.edu. Archived from the original on 4 April 2019. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- ^ "S.C. Fredericks- Lucian's True History as SF". www.depauw.edu. Retrieved 29 December 2022.

- ^ Irwin, Robert (2003). The Arabian Nights: A Companion. Tauris Parke Paperbacks. pp. 209–13. ISBN 978-1-86064-983-7.

- ^ a b Richardson, Matthew (2001). The Halstead Treasury of Ancient Science Fiction. Rushcutters Bay, New South Wales: Halstead Press. ISBN 978-1-875684-64-9. (cf.)

- ^ "Islamset-Muslim Scientists-Ibn Al Nafis as a Philosopher". 6 February 2008. Archived from the original on 6 February 2008. Retrieved 29 December 2022.

- ^ Creator and presenter: Carl Sagan (12 October 1980). "The Harmony of the Worlds". Cosmos: A Personal Voyage. PBS.

- ^ Jacqueline Glomski (2013). Stefan Walser; Isabella Tilg (eds.). "Science Fiction in the Seventeenth Century: The Neo-Latin Somnium and its Relationship with the Vernacular". Der Neulateinische Roman Als Medium Seiner Zeit. BoD: 37. ISBN 9783823367925. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- ^ White, William (September 2009). "Science, Factions, and the Persistent Specter of War: Margaret Cavendish's Blazing World". Intersect: The Stanford Journal of Science, Technology and Society. 2 (1): 40–51. Archived from the original on 27 December 2013. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- ^ Murphy, Michael (2011). A Description of the Blazing World. Broadview Press. ISBN 978-1-77048-035-3. Archived from the original on 6 May 2016. Retrieved 7 November 2015.

- ^ "Margaret Cavendish's The Blazing World (1666)". Skulls in the Stars. 2 January 2011. Archived from the original on 12 December 2015. Retrieved 17 December 2015.

- ^ Robin Anne Reid (2009). Women in Science Fiction and Fantasy: Overviews. ABC-CLIO. p. 59. ISBN 978-0-313-33591-4.[영구 데드링크]

- ^ 칸나, 리 컬렌. "유토피아의 주제: 마거릿 캐번디시와 그녀의 불타는 세계". 여성에 의한 유토피아와 SF: 차이의 세계. 시라큐스: 시라큐스 UP, 1994. 15-34.

- ^ "Carl Sagan on Johannes Kepler's persecution". YouTube. Archived from the original on 29 November 2011. Retrieved 24 July 2010.

- ^ Asimov, Isaac (1977). The Beginning and the End. New York: Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-13088-2.

- ^ "Kepler, the Father of Science Fiction". bbvaopenmind.com. 16 November 2015.

- ^ Popova, Maria (27 December 2019). "How Kepler Invented Science Fiction and Defended His Mother in a Witchcraft Trial While Revolutionizing Our Understanding of the Universe". themarginalian.org.

- ^ Clute, John & Nicholls, Peter (1993). "Mary W. Shelley". Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Orbit/Time Warner Book Group UK. Archived from the original on 16 November 2006. Retrieved 17 January 2007.

- ^ Wingrove, Aldriss (2001). Billion Year Spree: The History of Science Fiction (1973) Revised and expanded as Trillion Year Spree (with David Wingrove)(1986). New York: House of Stratus. ISBN 978-0-7551-0068-2.

- ^ 트레쉬, 존 (2002). "엑스트라! 엑스트라! 포는 공상과학소설을 창안합니다." 헤이스에서 케빈 J. 에드거 앨런 포의 케임브리지 동반자. 캠브리지: 캠브리지 대학 출판부. 113-132쪽. ISBN 978-0-521-79326-1.

- ^ Poe, Edgar Allan. The Works of Edgar Allan Poe, Volume 1, "The Unparalleled Adventures of One Hans Pfaal". Archived from the original on 27 June 2006. Retrieved 17 January 2007.

- ^ a b Roberts, Adam (2000), Science Fiction, London: Routledge, p. 48, ISBN 9780415192057

- ^ Renard, Maurice (November 1994), "On the Scientific-Marvelous Novel and Its Influence on the Understanding of Progress", Science Fiction Studies, 21 (64), archived from the original on 12 November 2020, retrieved 25 January 2016

- ^ Thomas, Theodore L. (December 1961). "The Watery Wonders of Captain Nemo". Galaxy Science Fiction. pp. 168–177.

- ^ Margaret Drabble (8 May 2014). "Submarine dreams: Jules Verne's Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas". New Statesman. Archived from the original on 11 May 2014. Retrieved 9 May 2014.

- ^ Laobra narativa de Enrique Gaspar: 엘 아나크로노페테(1887), 마리아 데 로스 앙헬레스 아얄라, 알리칸테 대학교. 델 낭만주의적 사실주의: Actas del I Coloquio de la S. E. S. XIX, 바르셀로나, 1996년 10월 24-26일 / 루이스 F. 편집 디아스 라리오스, 엔리케 미랄레스.

- ^ Elanacronópete, 영문 번역(2014), www.storypilot.com , Michael Main, 2016년 4월 13일 접속

- ^ Suffolk, Alex (28 February 2012). "Professor explores the work of a science fiction pioneer". Highlander. Retrieved 25 January 2023.

- ^ 아서 B. 에반스 (1988). SF vs. 프랑스의 과학소설: Jules Verne에서 J.-H. Rosny A î네까지 (프랑스의 공상과학 콘트라 소설; De Jules Verne à J.-H. Rosny a ì네까지) 2022년 12월 28일 웨이백 머신에 보관. In: 공상과학 연구, 15권, 1번, 1-11쪽.

- ^ Siegel, Mark Richard (1988). Hugo Gernsback, Father of Modern Science Fiction: With Essays on Frank Herbert and Bram Stoker. Borgo Pr. ISBN 978-0-89370-174-1.

- ^ Wagar, W. Warren (2004). H.G. Wells: Traversing Time. Wesleyan University Press. p. 7.

- ^ "HG Wells: A visionary who should be remembered for his social predictions, not just his scientific ones". The Independent. 8 October 2017. Archived from the original on 18 March 2020. Retrieved 2 February 2018.

- ^ 포르제스, 어윈 (1975). 에드가 라이스 버로우즈. 프로보, 유타: 브리검 영 대학교 출판부. ISBN 0-8425-0079-0.

- ^ a b "Science fiction". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 24 April 2023.

- ^ 브라운, p. xi는 쉐인을 인용하여 1921년을 제시합니다. 러셀, 페이지 3은 첫 번째 초안의 날짜를 1919년으로 잡고 있습니다.

- ^ Orwell, George (4 January 1946). "Review of WE by E. I. Zamyatin". Tribune. London – via Orwell.ru.

- ^ 1926년 4월호 어메이징 스토리(Amazing Stories)에 실렸습니다.

- ^ [1993]에 인용된 내용:

- ^ 에드워즈, 말콤 J. 니콜스, 피터 (1995). 'SF 매거진'. 존 클루트와 피터 니콜스에서. 공상과학소설백과 (업데이트). 뉴욕: 세인트 마틴의 그리핀. 1066쪽. ISBN 0-312-09618-6.

- ^ Dozois, Gardner; Strahan, Jonathan (2007). The New Space Opera (1st ed.). New York: Eos. p. 2. ISBN 9780060846756.

- ^ Roberts, Garyn G. (2001). "Buck Rogers". In Browne, Ray B.; Browne, Pat (eds.). The Guide To United States Popular Culture. Bowling Green, Ohio: Bowling Green State University Popular Press. p. 120. ISBN 978-0-87972-821-2.

- ^ Taormina, Agatha (19 January 2005). "A History of Science Fiction". Northern Virginia Community College. Archived from the original on 26 March 2004. Retrieved 16 January 2007.

- ^ Nichols, Peter; Ashley, Mike (23 June 2021). "Golden Age of SF". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 17 November 2022.

- ^ Codex, Regius (2014). From Robots to Foundations. Wiesbaden/Ljubljana: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. ISBN 978-1499569827.

- ^ Asimov, Isaac (1980). In Joy Still Felt: The Autobiography of Isaac Asimov, 1954–1978. Garden City, New York: Doubleday. chapter 24. ISBN 978-0-385-15544-1.

- ^ "1966 Hugo Awards". thehugoawards.org. Hugo Award. 26 July 2007. Archived from the original on 7 May 2011. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- ^ "The Long List of Hugo Awards, 1966". New England Science Fiction Association. Archived from the original on 3 April 2016. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- ^ 니콜스, 피터 (1981) 과학소설 백과사전, 그라나다, p. 258

- ^ "시간과 공간", 하트포드 쿠랑, 1954년 2월 7일 p.SM19

- ^ "Reviews: November 1975". www.depauw.edu. Retrieved 29 December 2022.

- ^ Aldiss & Wingrove, Trillion Year Spring, Victor Gollancz, 1986, p.237

- ^ "Ivan Efremov's works". Serg's Home Page. Archived from the original on 29 April 2003. Retrieved 8 September 2006.

- ^ "OFF-LINE интервью с Борисом Стругацким" [OFF-LINE interview with Boris Strugatsky] (in Russian). Russian Science Fiction & Fantasy. December 2006. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

- ^ Gale, Floyd C. (October 1960). "Galaxy's 5 Star Shelf". Galaxy Science Fiction. pp. 142–146.

- ^ McMillan, Graeme (3 November 2016). "Why 'Starship Troopers' May Be Too Controversial to Adapt Faithfully". Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 8 May 2017.

- ^ Liptak, Andrew (3 November 2016). "Four things that we want to see in the Starship Troopers reboot". The Verge. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 9 May 2017.

- ^ Slusser, George E. (1987). Intersections: Fantasy and Science Fiction Alternatives. Carbondale, Illinois: Southern Illinois University Press. pp. 210–220. ISBN 9780809313747. Archived from the original on 22 March 2019. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- ^ Mikołajewska, Emilia; Mikołajewski, Dariusz (May 2013). "Exoskeletons in Neurological Diseases – Current and Potential Future Applications". Advances in Clinical and Experimental Medicine. 20 (2): 228 Fig. 2. Archived from the original on 3 April 2020. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- ^ Weiss, Peter. "Dances with Robots". Science News Online. Archived from the original on 16 January 2006. Retrieved 4 March 2006.

- ^ "Unternehmen Stardust – Perrypedia". www.perrypedia.proc.org (in German). Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ "Der Unsterbliche – Perrypedia". www.perrypedia.proc.org (in German). Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ 마이크 애슐리 (2007년 5월 14일). 영원으로 가는 게이트웨이: 1970-1980 사이의 공상과학 잡지 이야기. 리버풀 대학 출판부. 218쪽. ISBN 978-1-84631-003-4.

- ^ McGuirk, Carol (1992). "The 'New' Romancers". In Slusser, George Edgar; Shippey, T. A. (eds.). Fiction 2000. University of Georgia Press. pp. 109–125. ISBN 9780820314495.

- ^ Caroti, Simone (2011). The Generation Starship in Science Fiction. McFarland. p. 156. ISBN 9780786485765.

- ^ Peter Swirski (ed), The Art and Science of Stanislaw Lem, McGill-Queen's University Press, 2008, ISBN 0-7735-3047-9

- ^ Stanislaw Lem, Fantastykai Futuriologia, Weawnict two Literackie, 1989, vol. 2, p. 365

- ^ 베네트의 독자 백과사전, 제4판(1996), p. 590.

- ^ Roberts, Adam (2000). Science Fiction. New York: Routledge. pp. 85–90. ISBN 978-0-415-19204-0.

- ^ ISFDB 펀의 드래곤 라이더입니다.

- ^ 로빈 로버츠에 대한 출판인 주간 리뷰, 앤 맥카프리: 드래곤과 함께하는 삶(2007). Wayback Machine에서 2021년 6월 1일 Amazon.com Archiveed. 2011-07-16 회수.

- ^ Sammon, Paul M. (1996). Future Noir: 블레이드 러너의 제작. 런던: 오리온 미디어 49쪽 ISBN 0-06-105314-7.

- ^ Wolfe, Gary K. (23 October 2017). "'Blade Runner 2049': How does Philip K. Dick's vision hold up?". chicagotribune.com. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ Stover, Leon E. "인류학과 과학소설" Current Humanology, Vol. 14, No. 4 (1973년 10월)

- ^ 리드, 수잔 엘리자베스 (1997). 우르술라 르귄을 소개합니다. 뉴욕, 뉴욕, 미국: 트웨인. ISBN 978-0-8057-4609-9, pp=9, 120

- ^ 스피백, 샬롯 (1984). 우슐라 K. Le Guin (1st ed.). 보스턴, 메사추세츠, 미국: 트웨인 출판사. ISBN 978-0-8057-7393-4., pp=44–50

- ^ "Brave New World of Chinese Science Fiction". www.china.org.cn. Archived from the original on 21 June 2018. Retrieved 26 April 2018.

- ^ "Science Fiction, Globalization, and the People's Republic of China". www.concatenation.org. Archived from the original on 27 April 2018. Retrieved 26 April 2018.

- ^ 피팅, 피터 (1991년 7월). "사이버펑크의 교훈". 펜리에서; 로스, A. 기술문화. 미니애폴리스: 미네소타 대학교 출판부. 295-315쪽

- ^ Schactman, Noah (23 May 2008). "26 Years After Gibson, Pentagon Defines 'Cyberspace'". Wired. Archived from the original on 14 September 2008. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

- ^ Hayward, Philip (1993). Future Visions: New Technologies of the Screen. British Film Institute. pp. 180–204. Archived from the original on 21 February 2007. Retrieved 17 January 2007.

- ^ Walton, Jo (31 March 2009). "Weeping for her enemies: Lois McMaster Bujold's Shards of Honor". Tor.com. Archived from the original on 11 September 2014. Retrieved 9 September 2014.

- ^ "Loud Achievements: Lois McMaster Bujold's Science Fiction". www.dendarii.com. Retrieved 29 December 2022.

- ^ Mustich, James (13 October 2008). "Interviews – Neal Stephenson: Anathem – A Conversation with James Mustich, Editor-in-Chief of the Barnes & Noble Review". barnesandnoble.com. Archived from the original on 11 August 2014. Retrieved 6 August 2014.

I'd had a similar reaction to yours when I'd first read The Origin of Consciousness and the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind, and that, combined with the desire to use IT, were two elements from which Snow Crash grew.

- ^ "Three Body". Ken Liu, Writer. 23 January 2015. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ Benson, Ed (31 March 2015). "2015 Hugo Awards". Archived from the original on 9 May 2020. Retrieved 26 April 2018.

- ^ "Out of this world: Chinese sci-fi author Liu Cixin is Asia's first writer to win Hugo award for best novel". South China Morning Post. 24 August 2015. Retrieved 29 December 2022.

- ^ Anders, Charlie Jane (27 July 2012). "10 Recent Science Fiction Books That Are About Big Ideas". io9. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ "Science fiction in the 21st century". www.studienet.dk. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ Bebergal, Peter (26 August 2007). "The age of steampunk:Nostalgia meets the future, joined carefully with brass screws". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- ^ Pulver, David L. (1998). GURPS Bio-Tech. Steve Jackson Games. ISBN 978-1-55634-336-0.

- ^ Paul Taylor (June 2000). "Fleshing Out the Maelstrom: Biopunk and the Violence of Information". M/C Journal. Journal of Media and Culture. 3 (3). doi:10.5204/mcj.1853. Archived from the original on 17 June 2005. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

- ^ "How sci-fi moves with the times". BBC News. 18 March 2009. Archived from the original on 28 February 2018. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

- ^ Walter, Damien (2 May 2008). "The really exciting science fiction is boring". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 27 January 2018. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

- ^ Dixon, Wheeler Winston; Foster, Gwendolyn Audrey (2008), A Short History of Film, Rutgers University Press, p. 12, ISBN 978-0-8135-4475-5, archived from the original on 22 March 2019, retrieved 19 December 2017

- ^ Kramer, Fritzi (29 March 2015). "A Trip to the Moon (1902) A Silent Film Review". Movies Silently. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ Eagan, Daniel. "A Trip to the Moon as You've Never Seen it Before". Smithsonian. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ Schneider, Steven Jay (1 October 2012), 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die 2012, Octopus Publishing Group, p. 20, ISBN 978-1-84403-733-9

- ^ Dixon, Wheeler Winston; Foster, Gwendolyn Audrey (1 March 2008). A Short History of Film. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 9780813544755. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- ^ SF 영화 역사 – 메트로폴리스(1927) 2017년 10월 10일 웨이백 머신에서 보관 – 대부분의 사람들이 첫 번째 SF 영화가 조르주 멜리에스의 달 여행(1902)이라는 것에 동의하지만 메트로폴리스(1926)는 장르의 첫 번째 장편 나들이입니다. (scififilmhistory.com , 2013년 5월 15일 검색)

- ^ "Metropolis". Turner Classic Movies. Archived from the original on 16 March 2014. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ "The 100 Best Films of World Cinema". empireonline.com. 11 June 2010. Archived from the original on 23 November 2015. Retrieved 17 February 2016.

- ^ "The Top 100 Silent Era Films". silentera.com. Archived from the original on 23 August 2000. Retrieved 17 February 2016.

- ^ "The Top 50 Greatest Films of All Time". Sight & Sound September 2012 issue. British Film Institute. 1 August 2012. Archived from the original on 1 March 2017. Retrieved 19 December 2012.

- ^ "Introduction to Kaiju [in Japanese]". dic-pixiv. Archived from the original on 18 February 2017. Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- ^ 中根, 研一 (September 2009). "A Study of Chinese monster culture – Mysterious animals that proliferates in present age media [in Japanese]". 北海学園大学学園論集. Hokkai-Gakuen University. 141: 91–121. Archived from the original on 12 March 2017. Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- ^ Kazan, Casey (10 July 2009). "Ridley Scott: "After 2001 -A Space Odyssey, Science Fiction is Dead"". Dailygalaxy.com. Archived from the original on 21 March 2011. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ^ William Johnson이 편집한 Focus on the Science Fiction Film. 뉴저지주 잉글우드 클리프: 프렌티스 홀, 1972.

- ^ DeMet, George D. "2001: A Space Odyssey Internet Resource Archive: The Search for Meaning in 2001". Palantir.net (originally an undergrad honors thesis). Archived from the original on 26 April 2011. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ^ Cass, Stephen (2 April 2009). "This Day in Science Fiction History – 2001: A Space Odyssey". Discover Magazine. Archived from the original on 28 March 2010. Retrieved 19 December 2017.

- ^ 루소, 조; 랜즈먼, 래리; 그로스, 에드워드(2001). 다시 찾은 유인원의 행성: 고전 SF 사가의 비하인드 스토리 (1sted.) 뉴욕: 토마스 던 북스/세인트 마틴의 그리핀. ISBN 0312252390.

- ^ Star Wars: Episode IV – A New Hope (1977) – IMDb, archived from the original on 9 April 2019, retrieved 30 March 2019

- ^ Bibbiani, William (24 April 2018). "The Best Space Operas (That Aren't Star Wars)". IGN. Archived from the original on 13 August 2019. Retrieved 5 April 2019.

- ^ "Star Wars – Box Office History". The Numbers. Archived from the original on 22 August 2013. Retrieved 17 June 2010.

- ^ "Star Wars Episode 4: A New Hope Lucasfilm.com". Lucasfilm. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ a b "Movie Franchises and Brands Index". www.boxofficemojo.com. Archived from the original on 20 July 2013. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ 탈출 속도: American Science Fiction Film, 1950-1982, Bradley Schauer, Wesleyan University Press, 2017년 1월 3일 7페이지

- ^ SF 영화: 비평적 소개, 키스 M. 존스턴, 버그, 2013년 5월 9일 24-25페이지. 몇 가지 예는 이 책에서 제공합니다.

- ^ SF TV, J.P. Telotte, Routledge, 2014년 3월 26일 112, 179페이지

- ^ Telotte, J. P. (2008). The essential science fiction television reader. University Press of Kentucky. p. 210. ISBN 978-0-8131-2492-6. Archived from the original on 1 June 2021. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- ^ Suzanne Williams-Rautiolla (2 April 2005). "Captain Video and His Video Rangers". The Museum of Broadcast Communications. Archived from the original on 30 March 2009. Retrieved 17 January 2007.

- ^ "The Twilight Zone [TV Series] [1959–1964]". AllMovie. Archived from the original on 20 June 2018. Retrieved 19 November 2012.

- ^ Stanyard, Stewart T. (2007). Dimensions Behind the Twilight Zone : A Backstage Tribute to Television's Groundbreaking Series ([Online-Ausg.] ed.). Toronto: ECW press. p. 18. ISBN 978-1550227444.

- ^ "TV Guide Names Top 50 Shows". CBS News. CBS Interactive. 26 April 2002. Archived from the original on 4 September 2012. Retrieved 13 April 2016.

- ^ "101 Best Written TV Series List". Archived from the original on 7 June 2013. Retrieved 13 April 2016.

- ^ O'Reilly, Terry (24 May 2014). "21st Century Brands". Under the Influence. Season 3. Episode 21. Event occurs at time 2:07. CBC Radio One. Archived from the original on 8 June 2014. Transcript of the original source. Retrieved 7 June 2014.

The series had lots of interesting devices that marveled us back in the 1960s. In episode one, we see wife Jane doing exercises in front of a flatscreen television. In another episode, we see George Jetson reading the newspaper on a screen. Can anyone say tablet? In another, Boss Spacely tells George to fix something called a "computer virus". Everyone on the show uses video chat, foreshadowing Skype and Face Time. There is a robot vacuum cleaner, foretelling the 2002 arrival of the iRobot Roomba vacuum. There was also a tanning bed used in an episode, a product that wasn't introduced to North America until 1979. And while flying space cars that have yet to land in our lives, the Jetsons show had moving sidewalks like we now have in airports, treadmills that didn't hit the consumer market until 1969, and they had a repairman who had a piece of technology called... Mac.

- ^ "Doctor Who Classic Episode Guide – An Unearthly Child – Details". BBC. Archived from the original on 25 October 2016. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ Deans, Jason (21 June 2005). "Doctor Who finally makes the Grade". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ "The end of Olde Englande: A lament for Blighty". The Economist. 14 September 2006. Archived from the original on 17 June 2009. Retrieved 18 September 2006.

- ^ "ICONS. A Portrait of England". Archived from the original on 3 November 2007. Retrieved 10 November 2007.

- ^ Moran, Caitlin (30 June 2007). "Doctor Who is simply masterful". The Times. London. Archived from the original on 17 June 2011. Retrieved 1 July 2007.

[Doctor Who] is as thrilling and as loved as Jolene, or bread and cheese, or honeysuckle, or Friday. It's quintessential to being British.

- ^ "Special Collectors' Issue: 100 Greatest Episodes of All Time". TV Guide (28 June – 4 July). 1997.

- ^ 영국 공상 과학 텔레비전: 히치하이커 안내서, 존 R. 쿡, 피터 라이트, I.B.타우리스, 2006년 1월 6일 9페이지

- ^ 고우란, 클레이. "닐슨 시청률은 새 방송에서 어둡습니다." 시카고 트리뷴 1966년 10월 11일 B10.

- ^ 굴드, 잭. "당신이 가장 좋아하는 비율은 어떻습니까? 생각보다 더 높을 수도 있습니다." 뉴욕 타임즈 1966년 10월 16일: 129.

- ^ Hilmes, Michele; Henry, Michael Lowell (1 August 2007). NBC: America's Network. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520250796. Archived from the original on 4 July 2016. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- ^ "A First Showing for 'Star Trek' Pilot". The New York Times. 22 July 1986. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 27 March 2014. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ 로든베리, 진 (1964년 3월 11일). 스타 트렉 피치 2016년 5월 12일 웨이백 머신에서 아카이브, 첫 번째 초안. LeeThomson.myzen.co.uk 에서 접속합니다.

- ^ "STARTREK.COM: Universe Timeline". Startrek.com. Archived from the original on 3 July 2009. Retrieved 14 July 2009.

- ^ Okada, Michael; Okadu, Denise (1 November 1996). Star Trek Chronology: The History of the Future. ISBN 978-0-671-53610-7.

- ^ "The Milwaukee Journal - Google News Archive Search". news.google.com. Retrieved 30 March 2019.[영구 데드링크]

- ^ Star Trek: The Next Generation, 26 September 1987, archived from the original on 25 March 2021, retrieved 30 March 2019

- ^ Whalen, Andrew (5 December 2018). "'Star Trek' Picard series won't premiere until late 2019, after 'Discovery' Season 2". Newsweek. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ "New Trek Animated Series Announced". www.startrek.com. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ "Patrick Stewart to Reprise 'Star Trek' Role in New CBS All Access Series". The Hollywood Reporter. 4 August 2018. Archived from the original on 4 August 2018. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ 베델, 샐리 (1983-05-04). '''V' 시리즈 ANBC 히트''' 뉴욕타임즈 27쪽

- ^ Susman, Gary (17 November 2005). "Mini Splendored Things". Entertainment Weekly. EW.com. Archived from the original on 25 February 2014. Retrieved 7 January 2010.

- ^ "Worldwide Press Office – Red Dwarf on DVD". BBC. Archived from the original on 27 February 2010. Retrieved 28 November 2009.

- ^ Bischoff, David (December 1994). "Opening the X-Files: Behind the Scenes of TV's Hottest Show". Omni. 17 (3).

- ^ Goodman, Tim (18 January 2002). "'X-Files' Creator Ends Fox Series". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on 15 June 2011. Retrieved 27 July 2009.

- ^ "Gillian Anderson Confirms She's Leaving The X-Files TV Guide". TVGuide.com. 10 January 2018. Archived from the original on 30 April 2020. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ Andreeva, Nellie (24 March 2015). "'The X-Files' Returns As Fox Event Series With Creator Chris Carter And Stars David Duchovny & Gillian Anderson". Deadline. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ Sumner, Darren (10 May 2011). "Smallville bows this week – with Stargate's world record". GateWorld. Archived from the original on 1 March 2014. Retrieved 23 February 2014.

- ^ "CultT797.html". www.maestravida.com. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 29 December 2022.

- ^ "The 20 Best SyFy TV Shows of All Time". pastemagazine.com. 9 March 2018. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ "About Us". SYFY. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ Hines, Ree (27 April 2010). "So long, nerds! Syfy doesn't need you". TODAY.com. Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ Brioux, Bill. "Firefly series ready for liftoff". jam.canoe.ca. Archived from the original on 15 July 2012. Retrieved 10 December 2006.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint : 잘못된 URL (링크) - ^ 놀라운 경이로움: 인터워 아메리카의 과학과 SF를 상상하다, 존 청, 펜실베니아 대학교 출판부, 2012년 3월 19일 1-12페이지.

- ^ "When Science Fiction Predicts the Future". Escapist Magazine. 1 November 2018. Archived from the original on 4 April 2019. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- ^ Kotecki, Peter. "15 wild fictional predictions about future technology that came true". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 4 April 2019. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- ^ Munene, Alvin (23 October 2017). "Eight Ground-Breaking Inventions That Science Fiction Predicted". Sanvada. Archived from the original on 4 April 2019. Retrieved 3 April 2019.

- ^ 그린우드 공상과학 백과사전: 주제, 작품 및 경이, 2권, Gary Westfahl, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2005

- ^ Handwerk, Brian. "The Many Futuristic Predictions of H.G. Wells That Came True". Smithsonian. Archived from the original on 4 April 2019. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- ^ a b "Science and Technology: Public Attitudes and Public Understanding. Science Fiction and Pseudoscience". Science and Engineering Indicators–2002 (Report). Arlington, VA: National Science Foundation, Division of Science Resources Statistics. April 2002. NSB 02-01. Archived from the original on 16 June 2016.

- ^ Bainbridge, William Sims (1982). "The Impact of Science Fiction on Attitudes Toward Technology". In Emme, Eugene Morlock (ed.). Science fiction and space futures: past and present. Univelt. ISBN 978-0-87703-173-4. Archived from the original on 1 January 2016. Retrieved 7 November 2015.

- ^ a b Sagan, Carl (28 May 1978). "Growing up with Science Fiction". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 11 December 2018. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- ^ "These 15 sci-fi books actually predicted the future". Business Insider. 8 November 2018. Retrieved 20 July 2022.

- ^ "Future Shock: 11 Real-Life Technologies That Science Fiction Predicted". Micron. Retrieved 20 July 2022.

- ^ Ерёмина Ольга Александровна. "Предвидения и предсказания". Иван Ефремов (in Russian). Retrieved 20 July 2022.

- ^ Fernando, Benjamin; Wójcicka, Natalia; Marouchka, Froment; Maguire, Ross; Stähler, Simon; Rolland, Lucie]; Collins, Gareth; Karatekin, Ozgur; Larmat, Carene; Sansom, Eleanor; Teanby, Nicholas; Spiga, Aymeric; Karakostas, Foivos; Leng, Kuangdai; Nissen-Meyer, Tarje; Kawamura, Taichi; Giardini, Domenico; Lognonné, Philippe; Banerdt, Bruce; Daubar, Ingrid (April 2021). "Listening for the landing: Seismic detections of Perseverance's arrival at Mars with InSight". Earth and Space Science. 8 (4). Bibcode:2021E&SS....801585F. doi:10.1029/2020EA001585. hdl:20.500.11937/90005. ISSN 2333-5084. S2CID 233672783.

- ^ Aldiss, Brian; Wingrove, David (1986). Trillion Year Spree. London: Victor Gollancz. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-575-03943-8.

- ^ Menadue, Christopher Benjamin; Cheer, Karen Diane (2017). "Human Culture and Science Fiction: A Review of the Literature, 1980–2016" (PDF). SAGE Open. 7 (3): 215824401772369. doi:10.1177/2158244017723690. ISSN 2158-2440. S2CID 149043845. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 July 2018. Retrieved 3 September 2019.

- ^ Miller, Bettye (6 November 2014). "George Slusser, Co-founder of Renowned Eaton Collection, Dies". UCR Today. Archived from the original on 4 April 2019. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- ^ Murphy, Bruce (1996). Benét's reader's encyclopedia. New York: Harper Collins. p. 734. ISBN 978-0061810886. OCLC 35572906.

- ^ Aaronovitch, David (8 February 2013). "1984: George Orwell's road to dystopia". BBC News. Archived from the original on 24 January 2018. Retrieved 8 February 2013.

- ^ Kelley, Sonaiya (28 March 2017). "As a Trump protest, theaters worldwide will screen the film version of Orwell's '1984'". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 4 April 2019. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- ^ "Nineteen Eighty-Four and the politics of dystopia". The British Library. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- ^ Gross, Terry (18 February 2010). "James Cameron: Pushing the limits of imagination". National Public Radio. Archived from the original on 21 February 2010. Retrieved 27 February 2010.

- ^ Androids, Humanoids, and Other Science Fiction Monster: Science and Soul in Science Fiction Films, Per Schelde, NYU Press, 1994, 1-10페이지

- ^ 웨스트팔에 있는 엘리스 레이 헬포드, 개리. 그린우드 공상과학 백과사전: Greenwood Press, 2005: 289–290.

- ^ Hauskeller, Michael; Carbonell, Curtis D.; Philbeck, Thomas D. (13 January 2016). The Palgrave handbook of posthumanism in film and television. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9781137430328. OCLC 918873873.

- ^ "Global warning: the rise of 'cli-fi'". the Guardian. 31 May 2013. Retrieved 29 December 2022.

- ^ Bloom, Dan (10 March 2015). "'Cli-Fi' Reaches into Literature Classrooms Worldwide". Inter Press Service News Agency. Archived from the original on 17 March 2015. Retrieved 23 March 2015.

- ^ Pérez-Peña, Richard (31 March 2014). "College Classes Use Arts to Brace for Climate Change". The New York Times. No. 1 April 2014 pg A12. Archived from the original on 13 April 2015. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- ^ Tuhus-Dubrow, Rebecca (Summer 2013). "Cli-Fi: Birth of a Genre". Dissent. Archived from the original on 22 March 2015. Retrieved 23 March 2015.

- ^ Raymond, Eric. "A Political History of SF". Archived from the original on 20 December 2015. Retrieved 4 December 2007.

- ^ SF와 판타지 속의 동물 우화, 브루스 쇼, 맥팔랜드, 2010, 19페이지

- ^ "Comedy Science Fiction". Sfbook.com. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 2 March 2016.

- ^ Kilgore, De Witt Douglas (March 2010). "Difference Engine: Aliens, Robots, and Other Racial Matters in the History of Science Fiction". Science Fiction Studies. 37 (1): 16–22. JSTOR 40649582 – via JSTOR.

- ^ 하트웰, 데이비드. 에이지 오브 원더즈 (뉴욕: 맥그로힐, 1985, 42페이지)

- ^ 아시모프, 아이작. '포워드 1 – 두 번째 혁명', 엘리슨, 할란(ed. 위험한 비전 (런던: 빅터 골란츠(Victor Gollancz, 1987)

- ^ "Critical Approaches to Science Fiction". christopher-mckitterick.com/. Retrieved 22 April 2023.

- ^ "What Is The Purpose of Science Fiction Stories? Project Hieroglyph". hieroglyph.asu.edu. Archived from the original on 4 April 2019. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- ^ "Index". www.depauw.edu. Archived from the original on 24 March 2019. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- ^ "Science Fiction Studies on JSTOR". Archived from the original on 4 April 2019. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- ^ "Science Fiction Research Association – About". www.sfra.org. Archived from the original on 4 April 2019. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- ^ "About: Science Fiction Foundation". Science Fiction Foundation. Archived from the original on 24 October 2018. Retrieved 3 April 2019.

- ^ "English: Science Fiction Studies MA – Overview – Postgraduate Taught Courses – University of Liverpool". www.liverpool.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 4 April 2019. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- ^ "BCLS: Hard Versus Soft Science Fiction". Archived from the original on 23 August 2018. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- ^ a b "Ten Authors on the 'Hard' vs. 'Soft' Science Fiction Debate". 20 February 2017. Archived from the original on 29 December 2018. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- ^ Wilde, Fran (21 January 2016). "How Do You Like Your Science Fiction? Ten Authors Weigh In On 'Hard' vs. 'Soft' SF". Tor.com. Archived from the original on 4 April 2019. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- ^ "Ursula K. Le Guin Proved That Sci-Fi is for Everyone". 24 January 2018. Archived from the original on 23 August 2018. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- ^ Browne, Max. "Holst, Theodor Richard Edward von (1810–1844)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/28353. (구독 또는 영국 공공도서관 회원가입 필요)

- ^ 베넷, 소개, ix-xi, 120-21; Schor, Cambridge Companion 소개, 1-5; Seymour, 548-61.

- ^ Allen, William R. (1991). Understanding Kurt Vonnegut. University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-87249-722-1.

- ^ Banach, Je (11 April 2013). "Laughing in the Face of Death: A Vonnegut Roundtable". The Paris Review. Archived from the original on 3 September 2015. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- ^ Jonas, Gerald (6 June 2012). "Ray Bradbury, Master of Science Fiction, Dies at 91". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 5 April 2019. Retrieved 5 June 2012.

- ^ 발로우, 웨인 더글러스 (1987). 바로우의 외계인 안내서. 워크맨 출판사. ISBN 0-89480-500-2.

- ^ 백스터, 존 (1997). '무한을 넘어선 쿠브릭'. Stanley Kubrick: 전기. 기초서적. 199-230쪽. ISBN 0-7867-0485-3.

- ^ 개리 케이. 울프와 캐롤 T. 윌리엄스, "친절의 여왕: 코드웨너 스미스의 변증법", 미래를 위한 목소리: 주요 SF 작가에 대한 에세이, 제3권, 토마스 D. Clareson 에디터, Popular Press, 1983, 53-72 페이지.

- ^ Hazelton, Lesley (25 July 1982). "Doris Lessing on Feminism, Communism and 'Space Fiction'". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 23 November 2013. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

- ^ Galin, Müge (1997). Between East and West: Sufism in the Novels of Doris Lessing. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-7914-3383-6. Archived from the original on 23 November 2020. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- ^ Lessing, Doris (1994) [1980]. "Preface". The Sirian Experiments. London: Flamingo. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-00-654721-1.

- ^ Donoghue, Denis (22 September 1985). "Alice, The Radical Homemaker". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 15 July 2014. Retrieved 4 July 2014.

- ^ Barnett, David (28 January 2009). "Science fiction: the genre that dare not speak its name". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 12 August 2016. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- ^ Potts, Robert (26 April 2003). "Light in the wilderness". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 5 October 2013. Retrieved 30 May 2013.

- ^ Langford, David, "Bits and Pieces", SFX 잡지 107호, 2003년 8월. 2009년 8월 20일 Wayback Machine에서 아카이브됨

- ^ "Lem and SFWA". Archived from the original on 11 January 2008. SFWA 회장이었던 1973-74년의 "제리 푸넬"을 미국의 SF 및 판타지 작가 FAQ에서 "Jerry Pournelle을 의역합니다.

- ^ 르귄, 우르술라 K. (1976) "사이언스 픽션과 브라운 부인", 밤의 언어: 판타지와 공상과학에 관한 에세이, 영구 하퍼 콜린스, 1993년 개정판; 사이언스 픽션 at Large (ed). 피터 니콜스), 골란츠, 런던, 1976; 마블러스 탐험(ed. 피터 니콜스(Peter Nicholls), 런던 폰타나, 1978; 투기에 관한 추측에서. 과학소설의 이론(eds. James Gunn and Matthew Candelaria), 허수아비 출판사 메릴랜드, 2005.

- ^ Card, O. (2006). "Introduction". Ender's Game. Macmillan. ISBN 9780765317384.

- ^ "Orson Scott Card Authors Macmillan". US Macmillan. Archived from the original on 5 January 2021. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- ^ 레템, 조나단(1998), "친밀한 만남: 공상과학소설의 방탕한 약속, 빌리지 보이스, 6월. 또한 "Why Can't We Can't Living Together?"라는 제목으로 약간 확장된 버전으로 재인쇄되었습니다. 장르 파라다이스 로스트의 비전 1998년 9월, 뉴욕 리뷰 오브 사이언스 픽션(New York Review of Science Fiction) 121권 11권 1호.

- ^ 벤포드, 그레고리 (1998) "의미가 꽉 찬 꿈:토마스 디스치와 SF의 미래", 뉴욕 리뷰 오브 사이언스 픽션, 9월, 121호, 11호, 1호

- ^ Crisp, Julie (10 July 2013). "Sexism in Genre Publishing: A Publisher's Perspective". Tor Books. Archived from the original on 30 April 2015. Retrieved 29 April 2015. (전체 통계 참조)

- ^ McCown, Alex (6 April 2015). "This year's Hugo Award nominees are a messy political controversy". The A.V. Club. The Onion. Archived from the original on 10 April 2015. Retrieved 11 April 2015.

- ^ "Awards". The World Science Fiction Society. 10 May 2016. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- ^ "Nebula Awards". www.fantasticfiction.com. Archived from the original on 31 May 2020. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- ^ "The John W. Campbell Award".

- ^ "The Theodore Sturgeon Award". Archived from the original on 1 October 2012. Retrieved 18 March 2023.

- ^ "The Academy of Science Fiction Fantasy and Horror Films". www.saturnawards.org. Archived from the original on 25 August 2012. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- ^ "Aurora Awards Canadian Science Fiction and Fantasy Association". Archived from the original on 4 April 2019. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- ^ "The Endeavour Award Home Page". osfci.org. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- ^ "ASFA". www.asfa-art.org. Archived from the original on 4 April 2019. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- ^ "Awards World Fantasy Convention". Archived from the original on 27 October 2012. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- ^ "Awards – Locus Online". Archived from the original on 4 April 2019. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- ^ "Conventions". Locus Online. 29 August 2017. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 5 April 2019.

- ^ Kelly, Kevin (21 February 2008). "A History Of The Science Fiction Convention". io9. Archived from the original on 3 June 2020. Retrieved 5 April 2019.

- ^ "ScifiConventions.com – Worldwide SciFi and Fantasy Conventions Directory – About Cons". www.scificonventions.com. Archived from the original on 8 April 2019. Retrieved 5 April 2019.

- ^ "FenCon XVI – September 20–22, 2019 ". www.fencon.org. Archived from the original on 2 April 2019. Retrieved 5 April 2019.

- ^ 마크 A. 만델 (2010년 1월 7일 ~ 9일). 경제학: 공상 과학 협약의 명명법. 2018년 4월 13일 Wayback Machine에서 보관

- ^ a b Wertham, Fredric (1973). The World of Fanzines. Carbondale & Evanston: Southern Illinois University Press.

- ^ a b "Fancyclopedia I: C – Cosmic Circle". fanac.org. 12 August 1999. Archived from the original on 12 September 2015. Retrieved 17 January 2007.

- ^ Lynch, Keith (14 July 1994). "History of the Net is Important". Archived from the original on 14 August 2015. Retrieved 17 January 2007.

- ^ "Usenet Fandom – Crisis on Infinite Earths". Archived from the original on 25 October 2019. Retrieved 5 April 2019.

- ^ Glyer, Mike (November 1998). "Is Your Club Dead Yet?". File 770 (127). Archived from the original on 22 March 2019. Retrieved 29 January 2018.

- ^ Hansen, Rob (13 August 2003). "British Fanzine Bibliography". Archived from the original on 22 March 2015. Retrieved 17 January 2007.

- ^ Latham, Rob; Mendlesohn, Farah (1 November 2014), "Fandom", The Oxford Handbook of Science Fiction, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199838844.013.0006, ISBN 9780199838844

- ^ "Ansible Home/Links". news.ansible.uk. Archived from the original on 29 March 2019. Retrieved 5 April 2019.

- ^ "Culture : Fanzine : SFE : Science Fiction Encyclopedia". www.sf-encyclopedia.com. Archived from the original on 26 March 2019. Retrieved 5 April 2019.

- ^ a b "Hugo Awards by Year". The Hugo Awards. 19 July 2007. Archived from the original on 2 April 2019. Retrieved 5 April 2019.

- ^ Bunzl, Martin (June 2004). "Counterfactual History: A User's Guide". American Historical Review. 109 (3): 845–858. doi:10.1086/530560. Archived from the original on 13 October 2004. Retrieved 2 June 2009.

- ^ a b Davies, David Stuart; Forshaw, Barry, eds. (2015). The Sherlock Holmes Book (First American ed.). New York: DK. p. 259. ISBN 978-1-4654-3849-2.

- ^ Sterling, Bruce (17 January 2019). "Science Fiction". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 29 January 2012. Retrieved 5 April 2019.

- ^ a b Westfahl, Gary (2005). "Aliens in Space". In Gary Westfahl (ed.). The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Science Fiction and Fantasy: Themes, Works, and Wonders. Vol. 1. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press. pp. 14–16. ISBN 978-0-313-32951-7.

- ^ Parker, Helen N. (1977). Biological Themes in Modern Science Fiction. UMI Research Press.

- ^ Card, Orson Scott (1990). How to Write Science Fiction and Fantasy. Writer's Digest Books. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-89879-416-8.

- ^ Peter Fitting (2010), "Utopia, dystopia, and science fiction", in Gregory Claeys (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Utopian Literature, Cambridge University Press, pp. 138–139

- ^ Hartwell, David G. (1996). Age of Wonders: Exploring the World of Science Fiction. Tor Books. pp. 109–131. ISBN 978-0-312-86235-0.

- ^ 애슐리, M. (1989년 4월) 불멸의 교수, Astro Adventures No.7, p.6

- ^ H. G. Stratmann (14 September 2015). Using Medicine in Science Fiction: The SF Writer's Guide to Human Biology. Springer, 2015. p. 227. ISBN 9783319160153.

일반자료 및 인용자료

- 알디스, 브라이언. 억대 연도: 과학소설의 진정한 역사, 1973.

- 알디스, 브라이언, 윙로브, 데이비드. 조 단위 연간 지출: 과학소설의 역사, 개정판, 1986.

- 아미스, 킹슬리. 지옥의 새로운 지도들: 과학소설의 조사, 1958.

- 배런, 닐, 에드. Anatomy of Wonder : A Critical Guide to Science Fiction (5판). 웨스트포트, 코네티컷주: 도서관 언리미티드, 2004. ISBN 1-59158-171-0.

- 브로데릭, 데미안. 별빛의 독서: 포스트모던 사이언스 픽션. 런던: 루틀리지, 1995. 프린트.

- 클루트, 존 SF: 삽화 백과사전. 런던: Dorling Kindersley, 1995. ISBN 0-7513-0202-3.

- 클루트, 존과 피터 니콜스, eds. 과학소설 백과사전. 세인트 알반스, 허츠, 영국: 그라나다 출판사, 1979. ISBN 0-586-05380-8.

- 클루트, 존과 피터 니콜스, eds. 과학소설 백과사전. 뉴욕: 세인트 마틴 출판사, 1995. ISBN 0-312-13486-X.

- 디스크, 토마스 M. 우리 물건이 만들어진 꿈들. 뉴욕: 자유언론, 1998. ISBN 978-0-684-82405-5.

- 제임스슨, 프레드릭. 미래의 고고학: 유토피아와 다른 과학 소설이라고 불리는 이 욕망. 런던과 뉴욕: 베르소, 2005.

- 밀너, 앤드류. 공상 과학 소설을 찾습니다. 리버풀: 리버풀 대학교 출판부, 2012.

- 라자, 마수드 아쉬라프, 제이슨 W. 엘리스, 스와랄리피 난디. eds., 포스트 내셔널 판타지: 탈식민주의, 우주정치, 공상과학에 관한 에세이. 맥팔랜드 2011. ISBN 978-0-7864-6141-7.

- 레지널드, 로버트. 공상과학과 판타지 문학, 1975-1991. 디트로이트, MI/워싱턴 D.C./런던: 게일 리서치, 1992. ISBN 0-8103-1825-3.

- 로이, 피나키. "사이언스 픽션: 약간의 반영." Shodh Sanchar Bulletin, 10.39 (2020년 7월~9월): 138-42.

- Scholes, Robert E.; Rabkin, Eric S. (1977). Science fiction: history, science, vision. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-502174-5.

- 수빈, 다코. 공상과학소설의 변용: 문학 장르의 시학과 역사, 뉴헤이븐: 예일 대학교 출판부, 1979.

- 웰즈, 주타, 에드. 새로운 세계를 찾기 위해: 공상과학과 세계 정치 사이의 연결고리를 탐구합니다. 뉴욕: 팔그레이브 맥밀런, 2003. ISBN 0-312-29557-X.

- 웨스트팔, 개리, 에드. 그린우드 공상과학 백과사전: 테마, 작품, 경이로움(3권). 웨스트포트, 코네티컷주: 그린우드 프레스, 2005.

- 울프, 게리 K. 공상과학과 판타지에 대한 중요 용어: 용어집과 장학금 안내서. 뉴욕: 그린우드 프레스, 1986. ISBN 0-313-22981-3.

외부 링크

| 라이브러리 리소스정보 공상과학소설 |

- 구텐베르크 프로젝트의 SF 책꽂이

- 공상과학 팬진(현재 및 역사) 온라인

- SFWA "권장 독서" 목록

- 공상과학 standardebooks.org

- 공상과학 연구회

- 마이크 애슐리(Mike Ashley), 이안 싱클레어(Iain Sinclair) 등이 쓴 글 모음집, 미래에 대한 19세기 비전을 탐구합니다. 2023년 6월 18일 영국 도서관의 발견 문학 웹사이트에서 웨이백 머신에 보관.

- 토론토 공공도서관의 SF, 사변, 판타지의 메릴 컬렉션

- SF학의 SF사, 이론, 비평 연대표집

- 역대 SF 소설 베스트 50 (에스콰이어; 2022년 3월 21일)