펀자브 주

Punjabis

| |

|---|---|

| 총인구 | |

| c. 1억 5천만[1][2][3][4] | |

| 인구가 많은 지역 | |

| 108,586,959 (2022)[a][6][7][8] | |

| 37,520,211 (2022)[b][3][c][10] | |

| 942,170 (2021)[11][d] | |

| 700,000 (2006)[12] | |

| 253,740[13] | |

| 132,496 (2017)[14] | |

| 56,400 (2019)[15] | |

| 50,000 (2016)[16] | |

| 34,227 (2018)[17] | |

| 24,000 (2013)[18] | |

| 23,700 (2019)[19] | |

| 18,000 (2020)[20] | |

| 10,000 (2011)[21] | |

| 다른이들 | 펀자비 디아스포라 보기 |

| 언어들 | |

| L1: 펀자브어와 그 방언 L2: 우르두어(파키스탄어)와 힌디어 및 기타 인도어(인도어) | |

| 종교 | |

| 다수 소수자 파키스탄 펀자브: 다수 소수자 인디언 펀자브: 다수 소수자 | |

| 관련 민족 | |

| 다른 인도-아리아인 | |

| 에 관한 시리즈의 일부 |

| 펀자브 주 |

|---|

|

펀자브 포털 |

펀자브인 (펀자비: پنجابی(, , ) 또는 ਪੰਜਾਬੀ(, , )는 펀자브 지역과 관련된 인도-아리아 민족 언어 집단으로, 파키스탄 동부와 인도 북서부 지역으로 구성되어 있습니다. 그들은 일반적으로 표준 펀자브어 또는 다양한 펀자브어 방언을 양쪽에서 사용합니다.[29]

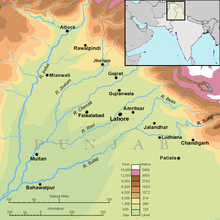

민족명은 페르시아어로 펀자브(다섯 개의 강)라는 용어에서 유래되었는데, 인도 아대륙 북서부의 지리적 지역을 설명하기 위해 현재는 사라진 Gaggar [30][31][32]외에 Beas, Chenab, Jhelum, Ravi, Sutlej 강이 인더스 강으로 합류합니다.[33]

펀자브 지역의 다양한 부족, 카스트 및 주민들이 18세기 시작부터 더 광범위한 공통의 "펀자비" 정체성으로 연합했습니다.[34][35][36] 역사적으로 펀자브 민족은 이질적인 집단이었고, 각각의 사람들이 하나의 씨족으로 묶여 있는 비라다리(말 그대로 "형제"라는 의미) 또는 부족이라고 불리는 다수의 씨족으로 세분되었습니다. 시간이 지남에 따라 공동체 구축과 집단 응집력이 펀자브 사회의 새로운 축을 이루면서 부족 구조는 보다 응집력 있고 총체적인 사회로 대체되었습니다.[36][37]

전통적으로 펀자브 정체성은 주로 언어적, 지리적, 문화적입니다. 펀자브어의 정체성은 역사적 기원이나 종교와 무관하며 펀자브 지역에 거주하거나 펀자브어를 모국어로 여기는 사람들을 말합니다.[38] 펀자브 정체성은 부족 간의 연결만을 기반으로 하는 것이 아니기 때문에, 통합과 동화는 펀자브 문화의 중요한 부분입니다.[39] 펀자브인들은 공통의 영토, 민족, 언어를 공유하고 있지만, 그들은 여러 종교들 중 하나, 대부분 이슬람교, 힌두교, 시크교 또는 기독교의 추종자들일 가능성이 높습니다.[40]

어원

펀잡(Punjab)이라는 용어는 16세기 후반 아크바르(Akbar) 통치 기간 동안 화폐로 사용되었습니다.[41][31][32] 펀자브라는 이름은 페르시아어에서 유래되었지만, 펀자브의 두 부분(پنج, 판즈, '다섯'과 آب, ā, '물')은 산스크리트어인 पञ्च, 파냐, '다섯'과 अप्, á, '물'과 같은 의미의 '아프, '물'의 동음이의어입니다. 따라서 파냐브라는 단어는 '오수의 땅'이라는 뜻으로, 야룸강, 체납강, 라비강, 수틀레강, 베아스강을 가리킵니다.[44] 모두 인더스강의 지류로 수틀레강이 가장 큽니다. 다섯 개의 강으로 이루어진 땅에 대한 언급은 고대 바라트 판차나다 (산스크리트어로 पञ्चनद, 로마자로 표기: pañca-nada, lit. '다섯 개의 강')의 한 지역을 부르는 마하바라타에서 찾을 수 있습니다. 고대 그리스인들은 이 지역을 펜타포타미아(그리스어: π εντα ποταμ ία)라고 불렀고, 이는 페르시아어와 같은 의미입니다.

지리적 분포

펀자브는 남아시아의 지정학적, 문화적, 역사적 지역으로, 특히 인도 아대륙의 북부 지역으로, 파키스탄 동부와 인도 북서부 지역으로 구성되어 있습니다. 그 지역의 경계는 명확하지 않고 역사적인 기록에 초점을 맞추고 있습니다. 펀잡(Punjab)이라는 용어의 지리적 정의는 시간이 지남에 따라 바뀌었습니다. 16세기 무굴 제국에서는 인더스 강과 수틀레 강 사이에 상대적으로 작은 지역을 언급했습니다.[50][41]

파키스탄

2017년 파키스탄 인구조사에서 펀자브의 총 인구는 1억 1천만 명이지만 [51]펀자브 민족은 국가 인구의 약 44.7%를 차지합니다.[5][6] 2022년 전국 인구가 2억 4,300만 명으로 추산되는 [5]펀자브 민족은 파키스탄에서 약 1억 8,500만 명에 달하며,[a][52] 이로 인해 펀자브 민족은 파키스탄에서 인구 기준으로 가장 큰 민족입니다.[5][6]

시아파, 아마디야 및 기독교 소수민족이 우세한 수니파 인구로서 종교적 동질성은 여전히 파악하기 어렵습니다.[53]

인도

펀자브어를 사용하는 사람들은 2011년 기준으로 인도 인구의 2.74%를 차지합니다.[54] 인도 인구조사에 민족성이 기록되어 있지 않기 때문에 인도 펀자브인들의 총 수는 알려지지 않았습니다. 시크교도들은 주로 현대 펀자브 주에 집중되어 있으며, 힌두교도들은 38.5%[55]를 차지합니다. 펀자브 민족은 델리 전체 인구의 40% 이상을 차지하는 것으로 추정되며, 대부분 힌디어를 사용하는 펀자브 힌두교도입니다.[56][57][58] 인도의 인구조사는 토착어를 기록하지만 시민들의 혈통은 기록하지 않습니다. 따라서 델리와 다른 인도 국가의 민족 구성에 대한 구체적인 공식 데이터는 없습니다.[58]: 8–10

인도 펀자브는 또한 이슬람교도들과 기독교인들의 소규모 집단의 본거지입니다. 1947년 동 펀자브의 대부분의 이슬람교도들은 서 펀자브로 떠났습니다.[59] 그러나 오늘날에도 카디아와 말레코틀라를 중심으로 한 작은 공동체가 존재합니다.[60]

펀자브 디아스포라

펀자브 사람들은 세계 여러 지역으로 대거 이주했습니다. 20세기 초, 가다르당을 결성한 독립운동가들을 포함하여 많은 펀자브인들이 미국에 정착하기 시작했습니다. 영국에는 파키스탄과 인도에서 온 펀자브족이 상당히 많습니다. 가장 인구가 많은 지역은 런던, 버밍엄, 맨체스터, 글래스고입니다. 캐나다(특히 밴쿠버,[61] 토론토,[62] 캘거리[63])와 미국(특히 캘리포니아의 센트럴 밸리와 뉴욕, 뉴저지 지역)에서. 1970년대에 아랍에미리트, 사우디아라비아, 쿠웨이트와 같은 중동 지역에서 펀자브인들의 대규모 이주가 시작되었습니다. 케냐, 우간다, 탄자니아를 포함한 동아프리카에도 큰 공동체가 있습니다. 펀자브인들은 또한 말레이시아, 태국, 싱가포르 그리고 홍콩을 포함한 호주, 뉴질랜드 그리고 동남아시아로 이주했습니다. 최근 많은 펀자브인들도 이탈리아로 이주했습니다.[citation needed]

인구통계학

카스트와 부족

서 펀자브(파키스탄)의 주요 카스트와 부족 중에는 자트족, 라지푸트족, 아레인족, 구자르족, 아완족이 있습니다.[64] 1947년 분할 이전에 웨스트 펀자브의 주요 공동체에는 카트리스족, 아로라스족, 브라만족도 포함되어 있었습니다.[65][66][67]

동 펀자브(인도)에 있는 동안 자트는 동 펀자브 인구의 거의 20%입니다. 공식 데이터에 따르면 스케줄드 캐스트는 전체 인구의 거의 32%, 전국적으로 SC의 4.3%를 차지합니다. 주에서 지정된 35개 이상의 예정 카스트 중 마자비스족, 라비다스족/람다시아족, 아드 다르미스족, 발미키스족 및 바지가르족이 함께 동 펀자브 전체 예정 카스트 인구의 약 87%를 차지합니다. 라비다시아 힌두교도와 람다시아 시크교도는 함께 동 펀자브 전체 예정 카스트 인구의 26.2%를 차지합니다. 람다시아와 라비다시아는 모두 샤마르의[68] 하위 집단이며 전통적으로 가죽과 관련된 직업과 연결되어 있습니다.[69]

펀자브의 종교

친힌두교는 펀자브 사람들에 의해 행해진 종교들 중 가장 오래된 것입니다.[30] 역사적인 베다 종교는 주로 인드라 숭배를 중심으로 한 베다 시대 (기원전 1500–500) 동안 펀자브의 종교적 사상과 관행을 구성했습니다.[70][71][72][note 1] 리그베다의 대부분은 기원전 1500년에서 1200년 사이에 펀자브 지역에서 구성되었고,[73] 나중에 베다 경전은 야무나 강과 갠지스 강 사이의 동쪽으로 더 많이 구성되었습니다. 브라만 힌두교 사제들이 개발한 마누스르티(Manusmriti)라는 고대 인도의 법전은 기원전 200년부터 펀자비 신앙생활을 형성했습니다.[74]

이후 인도 아대륙에서 불교와 자이나교가 전파되면서 펀자브에서 불교와 자이나교가 성장했습니다.[75] 이슬람교는 8세기에 남부 펀자브를 통해 유입되었고, 16세기에는 지역적인 개종을 통해 대다수가 되었습니다.[76][77] 16세기경 펀자브에는 작은 자인 공동체가 남아 있었고, 10세기경에는 불교 공동체가 대부분 사라졌습니다.[78] 이 지역은 다르가가 펀자브 지역의 풍경을 점찍는 선교사 수피 성도들로 인해 대부분 이슬람교도가 되었습니다.[79]

1700년대 시크교가 부상하면서 힌두교와 이슬람교를 믿는 일부 펀자브인들은 새로운 시크교 신앙을 받아들였습니다.[74][80] 인도 식민지 기간 동안 다수의 펀자브인들은 기독교인이 되었고, 이 모든 종교는 현재 펀자브 지역에서 발견되는 종교적 다양성을 특징으로 합니다.[74]

근세

종교적 긴장으로 인해, 펀자브 사람들 사이의 이주는 분열과 믿을 수 있는 기록보다 훨씬 이전에 시작되었습니다.[81][82] 인도 분할 직전인 1941년 펀자브주(영국령 인도)의 무슬림 인구는 약 53.2%로 예년보다 증가했습니다.[83]

1947년 분단으로 인해 펀자브 지역의 모든 지역에서 종교적 동질성으로의 급격한 전환이 이루어졌는데, 이는 이 지역을 가로지르는 새로운 국제 국경 때문이었습니다. 이처럼 급격한 인구 이동은 주로 대량 이주와 인구 교환 때문이기도 했지만, 당시 이 지역 전역에서 발생한 대규모 종교 청소 폭동 때문이기도 했습니다.[84][85] 역사적 인구 통계학자 팀 다이슨에 따르면, 독립 후 궁극적으로 인도 펀자브가 된 펀자브의 동쪽 지역은 1941년 66%가 힌두교도였던 지역이 1951년 80%가 되었고, 20%가 시크교도였던 지역은 1951년 50%가 되었습니다. 반대로, 궁극적으로 파키스탄 펀자브가 된 펀자브의 서부 지역에서는 1951년까지 모든 지역이 거의 독점적으로 무슬림이 되었습니다.[86]

분단 기간 동안의 인구 교류로 인해 펀자브의 두 지역은 현재 종교에 관한 한 비교적 동질적입니다. 오늘날 파키스탄 펀자브인들의 대다수는 소수의 기독교인들과 소수의 시크교도들과 힌두교도들보다 적은 수의 이슬람교를 따르지만, 인도 펀자브인들의 대다수는 이슬람교를 믿는 시크교도들이나 힌두교도들입니다. 펀자브는 시크교와 아마디야 운동의 발상지이기도 합니다.[87]

펀자브 무슬림

펀자브계 무슬림은 파키스탄에서만 거의 독점적으로 발견되는데, 펀자브계 무슬림의 97%가 이슬람교를 따라 파키스탄에 살고 있는데, 이는 인도에 주로 거주하는 펀자브계 시크교도와 펀자브계 힌두교도와는 대조적입니다.[23]

펀자브 지역에서 펀자브 민족의 대부분을 차지하는 [88]펀자브 이슬람교도들은 샤무키라고 불리는 페르시아 문자로 펀자브어를 씁니다. 인구가 8천만 명이 [88][89]넘는 그들은 파키스탄에서 가장 큰 민족이며 아랍인과[91] 벵골인에 이어 세계에서 세 번째로 이슬람을 고수하는 민족입니다[90].[92] 펀자브 무슬림의 대다수는 수니파 이슬람교를 신봉하는 반면, 소수는 시아파 이슬람교를 신봉하며, 영국 라지 시대 펀자브에서 시작된 아마디야 공동체를 포함한 다른 종파를 신봉합니다.

펀자비힌두스

인도 펀자브 주에서는 펀자브 주 인구의 약 38.5%가 펀자브 주에 속해 있으며, 도하 지역에서는 펀자브 힌두교도가 다수를 차지하고 있습니다. 펀자브의 5개 지역, 즉 파탄코트, 잘란드하르, 호시아르푸르, 파질카, 샤히드 바갓 싱 나가르 지역에서 펀자브 힌두교도가 다수를 차지하고 있습니다.[93]

1947년 분할 기간 동안 수백만 명의 펀자브 힌두교도들(힌코완 힌두교도와 사라이키 힌두교도[94][95] 포함)이 서펀자브와 북서 변경주에서 이주했으며, 이들 중 다수는 궁극적으로 델리에 정착했습니다. 1991년과 2015년 추정치에서 결정된 펀자브 힌두교도는 델리 인구의 약 24~35%를 차지하며,[e][f] 2011년 공식 인구 조사에 따르면 이는 4,029,106명에서 5,875,779명 사이에 해당합니다.[97]

1947년의 분할 기간 동안 일어난 대규모의 탈출에 이어, 오늘날 파키스탄에는 작은 펀자브 힌두 공동체가 남아 있습니다. 2017년 인구조사에 따르면 펀자브 지방에는 약 200,000명의 힌두교도가 있으며, 전체 인구의 약 0.2%를 형성하고 있습니다.[98] 대부분의 공동체는 라힘 야르 칸과 바하왈푸르의 주로 농촌 지역인 사우스 펀자브 지역에 거주하며 각각 인구의 3.12%와 1.12%를 형성하고 [99][100]나머지는 라호르와 같은 도시 중심지에 집중되어 있습니다.[101][102] 인도의 펀자브 힌두교도들은 힌두어와 펀자브어를 쓰기 위해 나가르 ī 문자를 사용합니다.

펀자브 시크교도

시크교(Sikhism)는 인도 아대륙의 펀자브 지역에서 15세기에 시작된 일신교입니다.[104][105] 신성한 경전 구루 그란트 사히브에 명시된 시크교의 근본 신앙은 하나의 창조자의 이름에 대한 믿음과 명상, 모든 인류의 단결과 평등, 이타적인 봉사에 종사하는 것, 모든 사람의 이익과 번영을 위한 사회 정의를 위해 노력하는 것, 그리고 세대주의 삶을 살면서 정직한 행동과 생계.[106][107][108] 전 세계적으로 2천 5백만에서 2천 8백만 명의 신도가 있는 주요 세계 종교 중 가장 어린 종교 중 하나인 시크교는 세계에서 다섯 번째로 큰 종교입니다.

시크교도는 오늘날 인도 펀자브에서 58%에 가까운 대다수를 형성합니다.

구르무키(Gurmukhi)는 시크교의 경전이자 시크교의 경전에 사용되는 문자입니다. 인도 일부 지역 및 기타 지역의 공식 문서에 사용됩니다.[103] 시크교도의 10대 구루인 구루 고빈드 싱 (1666–1708)은 칼사 형제단을 설립하고 그들을 위한 행동 강령을 세웠습니다.[109][110]

펀자브 기독교인

대부분의 현대 펀자브 기독교인들은 영국 통치 기간 동안 개종한 사람들의 후손입니다; 초기에 기독교로의 개종은 "높은 카스트" 힌두교 가정뿐만 아니라 무슬림 가정을 포함하여 "특권과 명망이 있는 펀자브 사회의 상류층"에서 비롯되었습니다.[111][112][113] 그러나 다른 현대 펀자브 기독교인들은 추라 그룹에서 개종했습니다. 추라인들은 영국의 라지 시대 동안 북인도에서 기독교로 개종했습니다. 대다수는 힌두교 추라 공동체인 펀자브에서 개종했고, 마조브 시크교도들은 열정적인 육군 장교들과 기독교 선교사들의 영향을 받았습니다. 많은 수의 마조하브 시크교도들이 모라다바드 지역과 우타르 프라데시의 비즈노르 지역에서도[114] 개종했습니다. Rohilkhand는 전체 인구 4500명의 Mazhab Sikhs가 감리교로 대량 개종하는 것을 보았습니다.[115] 시크교 단체들은 높은 카스트인 시크교 가문들의 개종 비율에 경각심을 갖게 되었고, 그 결과 개종에 대응하기 위해 시크교 선교사들을 즉시 파견하는 것으로 대응했습니다.[116]

역사

문화

펀자브 문화는 기원전 3000년까지 거슬러 올라가는 고대 인더스 문명 초기에 근동으로 가는 중요한 경로 역할을 했던 5개의 강을 따라 있는 정착지에서 성장했습니다.[30] 농업은 펀자브의 주요 경제적 특징이었고 따라서 토지 소유에 따라 사회적 지위가 결정되는 펀자브 문화의 기초를 형성했습니다.[30] 펀자브는 특히 1960년대 중반에서 1970년대 중반 동안 녹색 혁명 이후 중요한 농업 지역으로 부상했으며 "인도와 파키스탄의 빵 바구니"로 묘사되었습니다.[30] 펀자브는 농업과 무역으로 유명할 뿐만 아니라 수세기에 걸쳐 많은 외국의 침략을 경험했고 결과적으로 오랜 전쟁의 역사를 가지고 있는 지역이기도 합니다. 펀자브는 인도 아대륙의 북서쪽 국경을 통한 침략의 주요 경로에 위치하고 있기 때문입니다. 토지를 보호하기 위해 전쟁에 참여하는 생활 방식을 채택하도록 촉진했습니다.[30] 전사 문화는 일반적으로 공동체의 명예(izzat)의 가치를 높이며, 펀자브인들은 이를 매우 높이 평가합니다.[30]

언어

펀자브어(Punjabi)[g]는 펀자브어족이 모국어로 사용하는 인도-아리아어입니다.

펀자브어는 파키스탄에서 가장 인기 있는 모국어이며, 2017년 인구 조사에 따르면 8,050만 명의 원어민이 사용하고 있으며, 2011년 인구 조사에 따르면 3,110만 명의 원어민이 사용하여 인도에서 11번째로 인기가 있습니다.

이 언어는 특히 캐나다, 미국 및 영국에서 중요한 해외 디아스포라 사이에서 사용됩니다.

파키스탄에서 펀자브어는 페르시아어 문자를 기반으로 샤무키 문자를 사용하여 작성되며, 인도에서는 인디크 문자를 기반으로 구르무키 문자를 사용하여 작성됩니다. 펀자브어는 인도-아리아어족과 인도-유럽어족 사이에서 어휘 사용이 특이합니다.[117]

펀자비는 프라크리트어와 나중에 아파브라 ṃś아 (산스크리트어: अपभ्रंश, '탈락한' 또는 '비문법적인 말')로부터 발전했습니다. 기원전 600년부터, 산스크리트어가 공식 언어로 주창되었고, 프라크리트어는 인도의 여러 지역에서 많은 지역 언어를 낳았습니다. 이 모든 언어들을 통칭하여 프라크리트(산스크리트어: प्राकृत어, 프라크ṛ타)라고 부릅니다. Paishachi, Shauraseni, Gandhari는 인도 북부와 북서부에서 사용되었던 Prakrit 언어였으며 Punjabi는 이러한 Prakrit 중 하나에서 발전했습니다. 나중에 인도 북부에서 이 프라크리트인들은 프라크리트의 후손인 그들 자신의 아파브라 ṃś를 낳았습니다. 펀자비는 서기 7세기에 프라크리트의 퇴화된 형태인 아파브라 ṃś로 등장했고 10세기까지 안정되었습니다. 펀자브어의 가장 초기의 글은 서기 9세기에서 14세기까지의 나스 요기 시대에 속합니다.[121] 이러한 구성의 언어는 형태학적으로 샤우라세니 압브람사에 더 가깝지만, 어휘와 리듬은 극도의 구어체와 민속으로 가득 차 있습니다.[121] 역사적인 펀자브 지역의 아랍어와 현대 페르시아어의 영향은 1천년 후반의 이슬람교도들이 인도 아대륙을 정복하면서 시작되었습니다.[122] 많은 페르시아어와 아랍어 단어들이 펀자브어에 포함되었습니다.[123][124] 그래서 펀자브어는 언어에 대한 자유주의적 접근과 함께 사용되는 페르시아어와 아랍어 단어에 크게 의존합니다. 시크 제국이 멸망한 후 우르두어는 펀자브어(파키스탄 펀자브어에서는 여전히 주요 공용어)의 공용어가 되었고, 언어에도 영향을 미쳤습니다.[125]

펀자브어는 또한 펀자브어와 관련된 여러 언어와 방언을 사용합니다. 예를 들어, 북부 파키스탄 펀자브어의[126] 포트하르 지역에서 사용되는 포트와리어와 같은 말입니다.

전통의상

- 다스타

다스타(Dastar)는 시크교와 관련된 헤드기어의 일종으로 펀자브와 시크교 문화의 중요한 부분입니다. 시크교도들 사이에서 다타르는 평등, 명예, 자존, 용기, 영성, 경건함을 나타내는 신앙의 한 조항입니다. 5K를 지키는 칼사 시크교도 남녀는 자르지 않은 긴 머리(케시)를 가리기 위해 터번을 착용합니다. 시크교도들은 다스타르를 시크교도 특유의 정체성의 중요한 부분으로 여깁니다. 9대 시크교도 구루 테그 바하두르가 무굴 황제 오랑제브, 구루 고빈드 싱에 의해 사형 선고를 받은 후, 10대 시크교도 구루는 칼사를 만들고 5개의 신앙 조항을 주었는데, 그 중 하나는 다스타르가 덮고 있는, 깎지 않은 머리카락입니다.[127] 시크교 이전에는 왕, 왕족, 높은 지위에 있는 사람들만 터번을 착용했지만 시크교도 구루스는 사람들 사이의 평등과 주권을 주장하기 위해 그 관행을 채택했습니다.[128]

- 펀자브 슈트

카메즈 (위), 살와르 (아래), 두 가지 아이템이 특징인 펀자브 수트는 펀자브 사람들의 전통 의상입니다.[129][130][131] 샬워즈(Shalwars)는 전형적으로 허리가 넓지만 수갑이 있는 바닥까지 좁은 바지입니다. 그것들은 끈이나 탄성 벨트에 의해 지탱되며, 이것은 그것들이 허리 주위에 주름을 갖게 합니다.[132] 바지는 넓고 헐렁할 수도 있고, 매우 좁게 자를 수도 있습니다. 카메즈는 긴 셔츠 또는 튜닉입니다.[133] 옆[note 2] 솔기는 허리선 아래로 열려 있어 착용자에게 더 큰 움직임의 자유를 줍니다. 카메즈는 보통 반듯하고 평평하게 자릅니다. 오래된 카메즈는 전통적인 컷을 사용합니다. 현대 카메즈는 유럽에서 영감을 받은 세트인 소매를 가지고 있을 가능성이 더 높습니다. 이 조합의 옷은 때때로 살와르 쿠르타, 살와르 슈트 또는 펀자브 슈트라고 불립니다.[135][136] 샬와르카메즈는 파키스탄에서 널리 착용되고 [137][138]국민복입니다.[139] 일부 지역에서 여성들이 샬와르카메즈를 입을 때, 그들은 보통 머리나 목에 듀파타라고 불리는 긴 스카프나 숄을 입습니다.[140] 두파타는 섬세한 소재로 만들어져 있지만 어깨 위를 지나며 상체의 윤곽을 흐리게 하는 겸양의 한 형태로도 사용됩니다. 무슬림 여성들에게 듀파타는 차도르나 부르카(히잡과 푸르다 참조)에 대한 덜 엄격한 대안입니다. 시크교도와 힌두교 여성들에게 듀파타는 사원이나 장로들이 참석한 가운데 머리를 가려야 할 때 유용합니다.[141] 남아시아의 모든 곳에서 현대적인 스타일의 옷이 진화했습니다. 샤르는 허리에 아래로 착용하고, 카메즈는 길이가 짧으며, 더 높은 갈라짐, 더 낮은 목선과 등선, 그리고 크롭 소매가 있거나 소매가 없습니다.[142]

음악

방그라는 1980년대부터 발전된 펀자브 리듬으로 춤 위주의 대중음악을 설명합니다. 파키스탄 펀자브에서 흔히 행해지는 수피 음악과 카왈리는 펀자브 지역에서 다른 중요한 장르입니다.[143][144]

춤

펀자브 춤은 남자나 여자가 추는 춤입니다. 춤은 솔로부터 군무까지 다양하며 때로는 전통 악기와 함께 춤을 추기도 합니다. 방그라는 펀자브 지방에서 추수하는 시기에 농부들에 의해 유래된 가장 유명한 춤 중 하나입니다. 농부들이 농사일을 하는 동안 주로 행해졌습니다. 그들은 각각의 농사 활동을 하면서 현장에서 방그라 동작을 수행했습니다.[145] 이를 통해 그들은 즐거운 방식으로 일을 마칠 수 있었습니다. 수년 동안 농부들은 성취감을 보여주고 새로운 수확기를 환영하기 위해 방그라를 공연했습니다.[146] 전통적인 방그라는 원을[147] 그리며 공연되며, 전통적인 춤의 단계를 사용하여 공연됩니다. 전통 방그라는 이제 수확기가 아닌 다른 날에도 공연됩니다.[148][149]

민담

펀자브의 설화로는 히어 란자, 미르자 사히반, 손이 마히왈 등이 있습니다.[150][151]

축제

펀자브 이슬람교도들은 일반적으로 이슬람 축제를 기념합니다.[152][153] 펀자브 시크교도와 힌두교도들은 일반적으로 이것들을 지키지 않고 대신 로리, 바산트, 바이사키를 계절 축제로 지킵니다.[154] 펀자브 무슬림 축제는 음력 이슬람력(히지리)에 따라 정해지며, 날짜는 해마다 10~13일씩 앞당겨집니다.[155] 힌두교와 시크 펀자브 계절 축제는 루니-솔라 비크라미 달력 또는 펀자브 달력의 특정 날짜에 설정되며 축제 날짜도 일반적으로 그레고리력에 따라 다르지만 동일한 그레고리력 두 달 이내에 유지됩니다.[156]

펀자브 지역의 전통적인 계절 축제인 바이사키(Baisakhi), 바산트(Basant) 그리고 소수 규모의 로리(Lohri)에 일부 펀자브 이슬람교도들이 참여하지만, 이것은 논란의 여지가 있습니다. 이슬람 성직자들과 일부 정치인들은 펀자브 축제의 종교적 기반 때문에 이 참여를 금지하려고 시도했고,[157] 그들은 하람(이슬람에서는 금지됨)으로 선언되었습니다.[158]

펀자브 주

피파 비르디에 따르면 1947년 인도와 파키스탄의 분단은 인도 아대륙의 펀자브 민족과 그 디아스포라의 고향이었던 곳에 대한 상실감을 숨겼습니다.[159] 1980년대 중반부터 펀자브 문화 부흥, 펀자브 민족의 공고화, 가상의 펀자브 국가를 지향해 왔습니다.[160] 조르지오 샤니(Giorgio Shani)에 따르면, 이는 주로 일부 시크교 조직이 주도하는 시크교 민족주의 운동이며, 다른 종교에 속한 펀자브족 조직은 공유하지 않는 견해입니다.[161]

주목할 만한 사람들

참고 항목

메모들

- ^ a b 2022년 세계 팩트북에 따르면 펀자브는 파키스탄 전체 인구 242,923,845명 중 44.7%(108,586,959명)를 차지합니다.[5]

- ^ 2022년 월드 팩트북에 따르면 펀자브는 인도 전체 인구 1,389,637,446명 중 2.7%(37,520,211명)를 차지합니다.[9]

- ^ 이 수치는 인도의 펀자브어 사용자들로 구성되어 있습니다. 펀자브어를 더 이상 사용하지 않는 민족은 이 숫자에 포함되지 않습니다.

- ^ 통계에는 펀자브어를 모국어로 사용하지 않고 제2, 제3의 언어로 사용하는 사람들이 많기 때문에 펀자브어를 사용하는 모든 사람들이 포함됩니다.

- ^ "정착민들 사이에서 가장 중요한 부분은 펀자브족으로 인구의 약 35%를 구성하는 것으로 추정됩니다."[96]

- ^ "펀자브는 수도 인구의 24%에 불과하지만, 평균적으로 그들은 사용 가능한 관리직의 53%를 차지합니다."[58]

- ^ 펀자브어는 영국식 영어 철자이고, 파냐브 ī는 모국어 문자에서 로마자로 된 철자입니다.

참고문헌

- ^ "Punjabi - Worldwide distribution".

- ^ 펀자브는 민족학에 있습니다 (2018년 21기)

- ^ a b "Abstract Of Speakers' Strength Of Languages And Mother Tongues - 2011" (PDF). Registrar General and Census Commissioner of India. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 February 2022. Retrieved 12 June 2022.

- ^ "Pakistan Census 2017" (PDF). www.pbs.pk. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

- ^ a b c d "South Asia :: Pakistan — The World Fact book - Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

- ^ a b c "Ethnic Groups in Pakistan". Worldatlas.com. 30 July 2019.

Punjabi people are the ethnic majority in the Punjab region of Pakistan and Northern India accounting for 44.7% of the population in Pakistan.

- ^ "Pakistan Census 2017" (PDF). www.pbs.pk. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

- ^ "Punjabi - Worldwide distribution".

- ^ "South Asia :: India — The World Fact book - Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov. Retrieved 8 May 2022.

- ^ "Punjabi - Worldwide distribution".

- ^ Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (17 August 2022). "Census Profile, 2021 Census of Population Profile table Canada [Country]". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 18 August 2022.

- ^ McDonnell, John (5 December 2006). "Punjabi Community". House of Commons. Retrieved 3 August 2016.

We now estimate the Punjabi community at about 700,000, with Punjabi established as the second language certainly in London and possibly within the United Kingdom.

- ^ "US Census Bureau American Community Survey (2009-2013) See Row #62". 2.census.gov.

- ^ "Top ten languages spoken at home in Australia". Archived from the original on 9 July 2017.

- ^ "Malaysia". Ethnologue.com. Retrieved 28 July 2019.

- ^ "Punjabi community involved in money lending in Philippines braces for 'crackdown' by new President". 18 May 2016.

- ^ "New Zealand". Stats New Zealand. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- ^ Strazny, Philipp (1 February 2013). Encyclopedia of Linguistics. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-45522-4 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Bangladesh". Ethnologue.com. Retrieved 28 July 2019.

- ^ "Deutsche Informationszentrum für Sikhreligion, Sikhgeschichte, Kultur und Wissenschaft (DISR)". remid.de. Retrieved 3 January 2020.

- ^ "National Population and Housing Census 2011" (PDF). Unstats.unorg. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- ^ "C-1 Population By Religious Community - 2011". Archived from the original (XLS) on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- ^ a b Wade Davis; K. David Harrison; Catherine Herbert Howell (2007). Book of Peoples of the World: A Guide to Cultures. National Geographic. pp. 132–133. ISBN 978-1-4262-0238-4.

- ^ "Punjabis". Encyclopaedia.

- ^ Minahan, James (2012). Ethnic Groups of South Asia and the Pacific: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 257–259. ISBN 978-1-59884-659-1.

- ^ Temple, Richard Carnac (20 August 2017). A Dissertation on the Proper Names of Panjabis: With Special Reference to the Proper Names of Villagers in the Eastern Panjab. Creative Media Partners, LLC. ISBN 978-1-375-66993-1.

- ^ Goh, Daniel P. S.; Gabrielpillai, Matilda; Holden, Philip; Khoo, Gaik Cheng (12 June 2009). Race and Multiculturalism in Malaysia and Singapore. Routledge. p. 187. ISBN 978-1-134-01649-5.

- ^ Minahan, James (2012). Ethnic Groups of South Asia and the Pacific: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-59884-659-1.

- ^ Concise Encyclopedia of Languages of the World. Elsevier. 2010. pp. 522–523. ISBN 978-0-08-087775-4.

- ^ a b c d e f g Nayar, Kamala Elizabeth (2012). The Punjabis in British Columbia: Location, Labour, First Nations, and Multiculturalism. McGill-Queen's Press - MQUP. ISBN 978-0-7735-4070-5.

- ^ a b Gandhi, Rajmohan (2013). Punjab: A History from Aurangzeb to Mountbatten. New Delhi, India, Urbana, Illinois: Aleph Book Company. ISBN 978-93-83064-41-0.

- ^ a b Canfield, Robert L. (1991). Persia in Historical Perspective. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. p. 1 ("Origins"). ISBN 978-0-521-52291-5.

- ^ West, Barbara A. (19 May 2010). Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Asia and Oceania. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4381-1913-7.

- ^ Malhotra, Anshu; Mir, Farina (2012). Punjab reconsidered : history, culture, and practice. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-807801-2. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 6 April 2014.

- ^ Ayers, Alyssa (2008). "Language, the Nation, and Symbolic Capital: The Case of Punjab" (PDF). Journal of Asian Studies. 67 (3): 917–46. doi:10.1017/s0021911808001204. S2CID 56127067.

- ^ a b Singh, Pritam; Thandi, Shinder S. (1996). Globalisation and the region : explorations in Punjabi identity. Coventry, United Kingdom: Association for Punjab Studies (UK). ISBN 978-1-874699-05-7.

- ^ Mukherjee, Protap; Lopamudra Ray Saraswati (20 January 2011). "Levels and Patterns of Social Cohesion and Its Relationship with Development in India: A Woman's Perspective Approach" (PDF). Ph.D. Scholars, Centre for the Study of Regional Development School of Social Sciences Jawaharlal Nehru University New Delhi – 110 067, India.

- ^ Singh, Pritam; Thandi, Shinder S. (1999). Punjabi identity in a global context. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-564864-5.

- ^ Singh, Prtiam (2012). "Globalisation and Punjabi Identity: Resistance, Relocation and Reinvention (Yet Again!)" (PDF). Journal of Punjab Studies. 19 (2): 153–72. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 January 2016. Retrieved 6 April 2014.

- ^ Gupta, S.K. (1985). The Scheduled Castes in Modern Indian Politics: Their Emergence as a Political Context. New Delhi, India: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd. pp. 121–122.

- ^ a b Yoga, Project of History of Indian Science, Philosophy, and Culture Sub Project: Consciousness, Science, Society, Value, and (2009). Different Types of History. Pearson Education India. ISBN 978-81-317-1818-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: 다중 이름: 작성자 목록(링크) - ^ H K Manmohan Siṅgh. "The Punjab". The Encyclopedia of Sikhism, Editor-in-Chief Harbans Singh. Punjabi University, Patiala. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 18 August 2015.

- ^ Gandhi, Rajmohan (2013). Punjab: A History from Aurangzeb to Mountbatten. New Delhi, India, Urbana, Illinois: Aleph Book Company. p. 1 ("Introduction"). ISBN 978-93-83064-41-0.

- ^ "펀잡." 백과사전 107쪽 æ 디아 브리태니커(9판), 20권.

- ^ Kenneth Pletcher, ed. (2010). The Geography of India: Sacred and Historic Places. Britannica Educational Publishing. p. 199. ISBN 978-1-61530-202-4.

The word's origin can perhaps be traced to panca nada, Sanskrit for "five rivers" and the name of a region mentioned in the ancient epic the Mahabharata.

- ^ Rajesh Bala (2005). "Foreign Invasions and their Effect on Punjab". In Sukhdial Singh (ed.). Punjab History Conference, Thirty-seventh Session, March 18-20, 2005: Proceedings. Punjabi University. p. 80. ISBN 978-81-7380-990-3.

The word Punjab is a compound of two words-Panj (Five) and aab (Water), thus signifying the land of five waters or rivers. This origin can perhaps be traced to panch nada, Sanskrit for 'Five rivers' the word used before the advent of Muslims with a knowledge of Persian to describe the meeting point of the Jhelum, Chenab, Ravi, Beas, and Sutlej rivers, before they joined the Indus.

- ^ 라센, 크리스찬 1827년 Commentio Geographica attack Historica de Pentapotamia Indica [인도 펜타포타미아에 대한 지리적, 역사적 해설] 베버. 4쪽: "오늘날 우리가 페르시아어 이름인 "펜잡"이라고 부르는 인도의 그 지역은 인도인들의 신성한 언어로 판차나다라고 불립니다. π εντ αμ ι α에 의해 그리스어로 만들어질 수 있는 이름들 중 하나. 비록 그것이 구성된 단어들이 인도어와 페르시아어 둘 다이지만, 이전 이름의 페르시아어의 기원은 전혀 의심의 여지가 없습니다. 하지만 사실, 제가 아는 한, 그 마지막 단어는 결코 인도인들에 의해 이런 식으로 조합된 고유한 이름으로 사용되지 않습니다. 반면에, 그 단어로 끝나는 페르시아어 이름이 여러 개 존재합니다. 예를 들어, 도압과 닐랍이 있습니다. 따라서, 오늘날 모든 지리서에서 발견되는 펜잡이라는 이름은 더 최근의 것이며, 그 중 페르시아어가 주로 사용되었던 인도의 이슬람 왕들에게서 유래되었을 가능성이 있습니다. 판차나다라는 인도식 이름이 고대의 것이고 진품이라는 것은 그것이 인도의 가장 고대의 시인 라마야나와 마하바라타에 이미 나타나 있고, 그것 외에 인도인들 사이에 다른 어떤 것도 존재하지 않는다는 사실로부터 분명히 알 수 있습니다. 판차나다는 라마야나인의 영어 번역물을 펜잡과 함께 렌더링하는 판차를라는 다른 지역의 이름입니다. 펜타포타미아와는 완전히 다른..."[whose translation?]

- ^ Latif, Syad Muhammad (1891). History of the Panjáb from the Remotest Antiquity to the Present Time. Calcultta Central Press Company. p. 1.

The Panjáb, the Pentapotamia of the Greek historians, the north-western region of the empire of Hindostán, derives its name from two Persian words, panj (five), an áb (water, having reference to the five rivers which confer on the country its distinguishing features."

- ^ Khalid, Kanwal (2015). "Lahore of Pre Historic Era" (PDF). Journal of the Research Society of Pakistan. 52 (2): 73.

The earliest mention of five rivers in the collective sense was found in Yajurveda and a word Panchananda was used, which is a Sanskrit word to describe a land where five rivers meet. [...] In the later period the word Pentapotamia was used by the Greeks to identify this land. (Penta means 5 and potamia, water ___ the land of five rivers) Muslim Historians implied the word "Punjab " for this region. Again it was not a new word because in Persian-speaking areas, there are references of this name given to any particular place where five rivers or lakes meet.

- ^ J. S. Grewal (1998). The Sikhs of the Punjab. The New Cambridge History of India (Revised ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-521-63764-0.

- ^ "Population Profile Punjab Population Welfare Department". Pwd.punjab.gov.pk.

- ^ "Pakistan Population (2019)". Worldometers.info. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- ^ "Population by Religion" (PDF). pbs.gov.pk. Pakistan Bureau of Statistics.

- ^ "SCHEDULED LANGUAGES IN DESCENDING ORDER OF SPEAKERS' STRENGTH - 2011" (PDF). censusindia.gov.in. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- ^ Mohan, Vibhor (27 August 2015). "Census 2011: %age of Sikhs drops in Punjab; migration to blame?". The Times of India. Retrieved 10 September 2023.

- ^ "Delhi Assembly Elections 2015: Important Facts And Major Stakeholders Mobile Site". India TV News. 6 February 2015. Archived from the original on 30 December 2015. Retrieved 7 September 2015.

- ^ Jupinderjit Singh (February 2015). "Why Punjabis are central to Delhi election". tribuneindia.com/news/sunday-special/perspective/why-punjabis-are-central-to-delhi-election/36387.html. Retrieved 7 September 2015.

- ^ a b c Sanjay Yadav (2008). The Invasion of Delhi. Worldwide Books. ISBN 978-81-88054-00-8.

- ^ "Towards the 'Punjabi Province' (1947–1966)". The Sikhs of the Punjab. The New Cambridge History of India. Cambridge University Press. 1991. pp. 181–204. doi:10.1017/CHOL9780521268844.011. ISBN 978-0-521-26884-4.

- ^ Dikshit, V. (3 February 2017). "Punjab Polls: The mood in Malerkotla and Qadian". National Herald. Retrieved 10 September 2023.

- ^ "Census Profile, 2016 Census Vancouver [Census metropolitan area], British Columbia and British Columbia [Province]". Statistics Canada. 8 February 2017. Retrieved 31 August 2021.

- ^ "Census Profile, 2016 Census Toronto [Census metropolitan area], Ontario and Ontario [Province]". Statistics Canada. 8 February 2017. Retrieved 31 August 2021.

- ^ "Census Profile, 2016 Census Calgary [Census metropolitan area], Alberta and Alberta [Province]". Statistics Canada. 8 February 2017. Retrieved 31 August 2021.

- ^ "Punjab Province, Pakistan". Encyclopædia Britannica. 483579. Retrieved 22 March 2022.아

- ^ Tyagi, Dr Madhu (1 January 2017). THEORY OF INDIAN DIASPORA: DYNAMICS OF GLOBAL MIGRATION. Horizon Books (A Division of Ignited Minds Edutech P Ltd). p. 18. ISBN 978-93-86369-37-6.

- ^ Puri, Baij Nath (1988). The Khatris, a Socio-cultural Study. M.N. Publishers and Distributors. pp. 19–20.

- ^ Oonk, Gijsbert (2007). Global Indian Diasporas: Exploring Trajectories of Migration and Theory. Amsterdam University Press. pp. 43–45. ISBN 978-90-5356-035-8.

- ^ Chander, Rajesh K. (1 July 2019). Combating Social Exclusion: Inter-sectionalities of Caste, Gender, Class and Regions. Studera Press. ISBN 978-93-85883-58-3.

- ^ "Understanding the Dalit demography of Punjab, caste by caste". India Today. Retrieved 7 March 2022.

- ^ Wheeler, James Talboys (1874). The History of India from the Earliest Ages: Hindu Buddhist Brahmanical revival. N. Trübner. p. 330.

The Punjab, to say the least, was less Brahmanical. It was an ancient centre of the worship of Indra, who was always regarded as an enemy by the Bráhmans; and it was also a stronghold of Buddhism.

- ^ Hunter, W. W. (5 November 2013). The Indian Empire: Its People, History and Products. Routledge. p. 80. ISBN 978-1-136-38301-4.

In the settlements of the Punjab, Indra thus advanced to the first place among the Vedic divinities.

- ^ Virdee, Pippa (February 2018). From the Ashes of 1947. Cambridge University Press. p. 24. ISBN 978-1-108-42811-8.

The Rig Veda and the Upanishads, which belonged to the Vedic religion, were a precursor of Hinduism, both of which were composed in Punjab.

- ^ Flood, Gavin (13 July 1996). An Introduction to Hinduism. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-43878-0.

- ^ a b c Nayar, Kamala Elizabeth (2012). The Punjabis in British Columbia: Location, Labour, First Nations, and Multiculturalism. McGill-Queen's Press - MQUP. pp. 7–8. ISBN 978-0-7735-4070-5.

- ^ "In ancient Punjab, religion was fluid, not watertight, says Romila Thapar". The Indian Express. 3 May 2019.

Thapar said Buddhism was very popular in Punjab during the Mauryan and post-Mauryan period. Bookended between Gandhara in Taxila on the one side where Buddhism was practised on a large scale and Mathura on another side where Buddhism, Jainism and Puranic religions were practised, this religion flourished in the state. But after the Gupta period, Buddhism began to decline.

- ^ Rambo, Lewis R.; Farhadian, Charles E. (6 March 2014). The Oxford Handbook of Religious Conversion. Oxford University Press. pp. 489–491. ISBN 978-0-19-971354-7.

First, Islam was introduced into the southern Punjab in the opening decades of the eighth century. By the sixteenth century, Muslims were the majority in the region and an elaborate network of mosques and mausoleums marked the landscape. Local converts constituted the majority of this Muslim community, and as far for the mechanisms of conversion, the sources of the period emphasize the recitation of the Islamic confession of faith (shahada), the performance of the circumsicion (indri vaddani), and the ingestion of cow-meat (bhas khana).

- ^ Chhabra, G. S. (1968). Advanced History of the Punjab: Guru and post-Guru period upto Ranjit Singh. New Academic Publishing Company. p. 37.

- ^ Rambo, Lewis R.; Farhadian, Charles E. (6 March 2014). The Oxford Handbook of Religious Conversion. Oxford University Press. p. 490. ISBN 978-0-19-971354-7.

While Punjabi Hindu society was relatively well established, there was also a small but vibrant Jain community in the Punjab. Buddhist communities, however, had largely disappeared by the turn of the tenth century.

- ^ Nicholls, Ruth J.; Riddell, Peter G. (31 July 2020). Insights into Sufism: Voices from the Heart. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN 978-1-5275-5748-2.

With the Muslim conquest of Punjab there was a flow of Sufis and other preachers who came to spread Islam. Much of the advance of Islam was due to these preachers.

- ^ Singh, Pritam (19 February 2008). Federalism, Nationalism and Development: India and the Punjab Economy. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-04946-2.

- ^ 존스. (2006) 영국령 인도의 사회 종교 개혁 운동 (The New Cambridge History of India) 케임브리지 대학교 출판부

- ^ Jones, R. (2007). 인도의 대봉기, 1857-58: 전하지 못한 이야기, 인도와 영국(동인도 회사의 세계). 보이델 프레스.

- ^ "Journal of Punjab Studies – Center for Sikh and Punjab Studies – UC Santa Barbara" (PDF). Global.ucsb.edu. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 20 April 2013.

- ^ 남아시아: 2007년 11월 2일 Wayback Machine에서 영국령 인도 분할 보관

- ^ 아바리, B. (2007). 인도: 고대의 과거. ISBN 978-0-415-35616-9

- ^ Dyson 2018, pp. 188-189.

- ^ "Ahmadiyya – Ahmadiyya Community – Al Islam Online – Official Website". Alislam.org.

- ^ a b Gandhi, Rajmohan (2013). Punjab: A History from Aurangzeb to Mountbatten. New Delhi, India, Urbana, Illinois: Aleph Book Company. p. 1. ISBN 978-93-83064-41-0.

- ^ "Pakistan Census 2017" (PDF). PBS.

- ^ Gandhi, Rajmohan (2013). Punjab: A History from Aurangzeb to Mountbatten. New Delhi, India, Urbana, Illinois: Aleph Book Company. p. 2. ISBN 978-93-83064-41-0.

- ^ 마가렛 클레프너 니델 아랍인의 이해: 현대를 위한 가이드, 인터컬쳐 프레스, 2005, ISBN 1931930252, xxiii, 14페이지

- ^ 방글라데시의 약 1억 5,200만 명의 벵골 이슬람교도와 인도 공화국의 3,640만 명의 벵골 이슬람교도(CIA Factbook 2014 추정치, 급격한 인구 증가에 따른 숫자); 중동의 약 1,000만 명의 방글라데시인, 파키스탄의 100만 명의 벵골인, 500만 명의 영국 방글라데시인.

- ^ "Religion by districts - Punjab". census.gov.in. Retrieved 20 September 2021.

- ^ "Colonies, posh and model in name only!". NCR Tribune. Retrieved 5 March 2023.

Started in 1978, Derawal Nagar was a colony of those who had migrated from Dera Ismile Khan in Northwest Frontier provinces.

- ^ Nagpal, Vinod Kumar (25 June 2020). Lessons Unlearned. Notion Press. ISBN 978-1-64869-984-9.

- ^ Singh, Raj (6 February 2015). "Delhi Assembly elections 2015: Important facts and major stakeholders". India TV. Retrieved 8 September 2021.

- ^ "Delhi (India): Union Territory, Major Agglomerations & Towns – Population Statistics in Maps and Charts". City Population. Archived from the original on 2 March 2017. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- ^ "CCI defers approval of census results until elections". Dawn. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- ^ "District wise census". Retrieved 20 September 2021.

- ^ Dharmindar Balach (17 August 2017). "Pakistani Hindus celebrate Janmashtami with fervour". Daily Times. Retrieved 20 September 2021.

- ^ "Hindu community celebrates Diwali across Punjab". The Express Tribune. 8 November 2018. Retrieved 18 December 2020.

- ^ "Dussehra celebrated at Krishna Mandir". The Express Tribune. 23 October 2015. Retrieved 18 December 2020.

- ^ a b Peter T. Daniels; William Bright (1996). The World's Writing Systems. Oxford University Press. p. 395. ISBN 978-0-19-507993-7.

- ^ W.Owen Cole; Piara Singh Sambhi (1993). Sikhism and Christianity: A Comparative Study (Themes in Comparative Religion). Wallingford, United Kingdom: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 117. ISBN 978-0-333-54107-4.

- ^ Christopher Partridge (1 November 2013). Introduction to World Religions. Fortress Press. pp. 429–. ISBN 978-0-8006-9970-3.

- ^ Sewa Singh Kalsi. Sikhism. Chelsea House, Philadelphia. pp. 41–50.

- ^ William Owen Cole; Piara Singh Sambhi (1995). The Sikhs: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices. Sussex Academic Press. p. 200.

- ^ Teece, Geoff (2004). Sikhism:Religion in focus. Black Rabbit Books. p. 4. ISBN 978-1-58340-469-0.

- ^ Cole, W. Owen; Sambhi, Piara Singh (1978). The Sikhs: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices. Routledge. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-7100-8842-0.

- ^ John M Koller (2016). The Indian Way: An Introduction to the Philosophies & Religions of India. Routledge. pp. 312–313. ISBN 978-1-315-50740-8.

- ^ Jones, Kenneth W. (1976). Arya Dharm: Hindu Consciousness in 19th-century Punjab. University of California Press. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-520-02920-0.

Christian conversion followed patterns of previous religious inroads, striking at the two sections of the social structure. Initial conversions came from the upper levels of Punjab society, from the privileged and prestigious. Few in number and won individually, high caste converts accounted for far more public attention and reaction to Christian conversion than the numerically superior successes among the depressed. Repeatedly, conversion or the threat of conversion among students at mission schools, or members of the literate castes, produced a public uproar.

- ^ Day, Abby (28 December 2015). Contemporary Issues in the Worldwide Anglican Communion: Powers and Pieties. Ashgate Publishing. p. 220. ISBN 978-1-4724-4415-8.

The Anglican mission work in the northern part of the Indian subcontinent was primarily carried out by CMS and USPG in the Punjab Province (Gabriel 2007, 10), which covered most parts of the present state of Pakistan, particularly Lahore, Peshawar and Karachi (Gibbs 1984, 178-203). A native subcontinental church began to take shape with people from humbler backgrounds, while converts from high social caste preferred to attend the worship with the English (Gibbs 1984, 284).

- ^ Moghal, Dominic (1997). Human person in Punjabi society: a tension between religion and culture. Christian Study Centre.

Those Christians who were converted from the "high caste" families both Hindus and Muslims look down upon those Christians who were converted from the low caste, specially from the untouchables.

- ^ Alter, J.P and J. Alter (1986) 인디아와 로일칸드: 북인도 기독교, 1815-1915. I.S.P.C.K 출판사 p183

- ^ Alter, J.P and J. Alter (1986) 인디아와 로일칸드: 북인도 기독교, 1815-1915. I.S.P.C.K 출판사 p196

- ^ Chadha, Vivek (23 March 2005). Low Intensity Conflicts in India: An Analysis. SAGE Publications. p. 174. ISBN 978-0-7619-3325-0.

'In 1881 there were 3,976 Christians in the Punjab. By 1891 their number had increased to 19,547, by 1901 to 37,980, by 1911 to 163,994 and by 1921 to 315,931 persons' (see Figure 8.1). However, the Sikhs were more alarmed when some of the high caste families starting converting.

- ^ Bhatia, Tej (1999). "Lexican Anaphors and Pronouns in Punjabi". In Lust, Barbara; Gair, James (eds.). Lexical Anaphors and Pronouns in Selected South Asian Languages. Walter de Gruyter. p. 637. ISBN 978-3-11-014388-1. 다른 성조 인도-아리아어족 언어로는 힌드코어, 도그리어, 서파하리어, 실헤티어, 다르드어 등이 있습니다.

- ^ Singha, H. S. (2000). The Encyclopedia of Sikhism (over 1000 Entries). Hemkunt Press. p. 166. ISBN 978-81-7010-301-1. Archived from the original on 21 January 2017.

- ^ Singh, Sikander (April 2019). "The Origin Theories of Punjabi Language: A Context of Historiography of Punjabi Language". International Journal of Sikh Studies.

- ^ G S Sidhu (2004). Panjab And Panjabi.

- ^ a b Hoiberg, Dale (2000). Students' Britannica India. Popular Prakashan. ISBN 978-0-85229-760-5.

- ^ Brard, G.S.S. (2007). East of Indus: My Memories of Old Punjab. Hemkunt Publishers. p. 81. ISBN 9788170103608. Archived from the original on 9 February 2018. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- ^ Mir, F. (2010). The Social Space of Language: Vernacular Culture in British Colonial Punjab. University of California Press. p. 35. ISBN 9780520262690. Archived from the original on 9 February 2018. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- ^ Schiffman, H. (2011). Language Policy and Language Conflict in Afghanistan and Its Neighbors: The Changing Politics of Language Choice. Brill. p. 314. ISBN 9789004201453. Archived from the original on 9 February 2018. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- ^ Schiffman, Harold (9 December 2011). Language Policy and Language Conflict in Afghanistan and Its Neighbors: The Changing Politics of Language Choice. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-20145-3.

- ^ Fred A, Robertson (1895). Gazetteer of Rawalpindi District (2nd ed.). Punjab Government.

- ^ "시크교에서 터번의 중요성", earlytimes.in . 2018년 5월 29일.

- ^ "Sikh Theology Why Sikhs Wear A Turban". The Sikh Coalition. Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- ^ Dominique, Grele; Raimbault, Lydie (1 March 2007). Discover Singapore on Foot (2 ed.). Singapore: Select Publishing. p. 35. ISBN 978-981-4022-33-0.

- ^ Fraile, Sandra Santos (11 July 2013), "Sikhs in Barcelona", in Blanes, Ruy; Mapril, José (eds.), Sites and Politics of Religious Diversity in Southern Europe: The Best of All Gods, BRILL, p. 263, ISBN 978-90-04-25524-1,

The shalwar kamiz was worn traditionally by Muslim women and gradually adopted by many Hindu women following the Muslim conquest of northern India. Eventually, it became the regional style for parts of northern India, as in Punjab where it has been worn for centuries.

- ^ Khandelwal, Madhulika Shankar (2002), Becoming American, Being Indian: An Immigrant Community in New York City, Cornell University Press, p. 43, ISBN 0-8014-8807-9,

Even highly educated women pursuing careers continue to wear traditional dress in urban India, although men of similar status long ago adopted Western attire. The forms of dress most popular with urban Indian women are the sari, the long wrapped and draped dress-like garment, worn throughout India, and the salwar-kameez or kurta-pyjama, a two-piece suit garment, sometimes also called Punjabi because of its region of origin. Whereas the sari can be considered the national dress of Indian women, the salwar-kameez, though originally from the north, has been adopted all over India as more comfortable attire than the sari.

- ^ Stevenson, Angus; Waite, Maurice (2011), Concise Oxford English Dictionary: Book & CD-ROM Set, Oxford University Press, p. 1272, ISBN 978-0-19-960110-3,

Salwar/Shalwar: A pair of light, loose, pleated trousers, usually tapering to a tight fit around the ankles, worn by women from South Asia typically with a kameez (the two together being a salwar kameez). Origin From Persian and Urdu šalwār.

- ^ Stevenson, Angus; Waite, Maurice (2011), Concise Oxford English Dictionary: Book & CD-ROM Set, Oxford University Press, p. 774, ISBN 978-0-19-960110-3,

Kameez: A long tunic worn by many people from South Asia, typically with a salwar or churidars. Origin: From Arabic qamīṣ, perhaps from late Latin camisia (see chemise).

- ^ Platts, John Thompson (February 2015) [1884], A dictionary of Urdu, classical Hindi, and English (online ed.), London: W. H. Allen & Co., p. 418, archived from the original on 24 February 2021, retrieved 1 August 2022

- ^ Shukla, Pravina (2015). The Grace of Four Moons: Dress, Adornment, and the Art of the Body in Modern India. Indiana University Press. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-253-02121-2.

You can buy an entire three-piece salwar suit, or a two-piece suit that consists of either a readymade kurta or a kurta cloth piece, each with a matching dupatta. For these, you must have the salwar pants stitched from cloth you buy separately. A third option would be to buy a two-piece ensemble, consisting of the top and pants, leaving you the task of buying an appropriate dupatta, or using one you already own, or buying a strip of cloth and having it dyed to your desire. The end result will always be a three-piece ensemble, but a customer may start with one piece (only the kurta) or two pieces (kurta and pants, or kurta and dupatta), and exercise her creativity and fashion sense to end up with the complete salwar kurta outfit.

- ^ Mooney, Nicola (2011), Rural Nostalgias and Transnational Dreams: Identity and Modernity Among Jat Sikhs, University of Toronto Press, p. 260, ISBN 978-0-8020-9257-1,

The salwar-kameez is a form of dress that has been adopted widely in Punjab and is now known in English as the Punjabi suit; J. P. S. Uberoi suggests that the salwar-kameez is an Afghani import to Punjab (1998 personal communication). Punjabi forms of dress are therefore constructs or inventions of tradition rather than having historical veracity.

- ^ Marsden, Magnus (2005). Living Islam: Muslim Religious Experience in Pakistan's North-West Frontier. Cambridge University Press. p. 37. ISBN 978-1-139-44837-6.

The village's men and boys largely dress in sombre colours in the loose trousers and long shirt (shalwar kameez) worn across Pakistan. Older men often wear woollen Chitrali caps (pakol), waistcoats and long coats (chugha), made by Chitrali tailors (darzi) who skills are renowned across Pakistan.

- ^ Haines, Chad (2013), Nation, Territory, and Globalization in Pakistan: Traversing the Margins, Routledge, p. 162, ISBN 978-1-136-44997-0,

the shalwar kameez happens to be worn by just about everyone in Pakistan, including in all of Gilgit-Baltistan.

- ^ Ozyegin, Gul (2016). Gender and Sexuality in Muslim Cultures. Routledge. p. 222. ISBN 978-1-317-13051-2.

What is common in all the cases is the wearing of shalwar, kameez, and dupatta, the national dress of Pakistan.

- ^ Rait, Satwant Kaur (14 April 2005). Sikh Women In England: Religious, Social and Cultural Beliefs. Trent and Sterling: Trentham Book. p. 68. ISBN 978-1-85856-353-4.

- ^ Shukla, Pravina (2015), The Grace of Four Moons: Dress, Adornment, and the Art of the Body in Modern India, Indiana University Press, p. 72, ISBN 978-0-253-02121-2,

Muslim and Punjabi women—whether Muslim, Sikh, or Hindu—often wear the dupatta over the head to create a modest look while framing the face with color. When entering a temple, Hindu women might comparably use their dupattas to cover their heads. Though the dupatta is often made of flimsy cloth and does not actually cover the body, its presence implies modesty, like many of the outer garments worn by Muslim women that do not cover much but do provide a symbolic extra layer, ...

- ^ Koerner, Stephanie (2016), Unquiet Pasts: Risk Society, Lived Cultural Heritage, Re-designing Reflexivity, Taylor & Francis, p. 405, ISBN 978-1-351-87667-4,

The Pakistani National dress worn by women is Shalwar Kameez. This consists of a long tunic (Kameez) teamed with a wide legged trouser (Shalwar) that skims in at the bottom accompanied by a duppata, which is a less stringent alternative to the burqa. Modern versions of this National dress have evolved into less modest versions. Shalwar have become more low cut so that the hips are visible and are worn with a shorter length of Kameez which has high splits and may have a lowcut neckline and backline as well as being sleeveless or having cropped sleeves.

- ^ Pande, Alka (1999). Folk music & musical instruments of Punjab : from mustard fields to disco lights. Ahmedabad [India]: Mapin Pub. ISBN 978-18-902-0615-4.

- ^ Thinda, Karanaila Siṅgha (1996). Pañjāba dā loka wirasā (New rev. ed.). Paṭiālā: Pabalikeshana Biūro, Pañjābī Yūniwarasiṭī. ISBN 978-81-7380-223-2.

- ^ Pandher, Gurdeep. "Bhangra History". Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- ^ Singh, Khushwant (23 May 2017). Land of Five Rivers. Orient Paperbacks. ISBN 9788122201079 – via Google Books.

- ^ Bedell, J. M. (23 May 2017). Teens in Pakistan. Capstone. ISBN 9780756540432 – via Google Books.

- ^ Black, Carolyn (2003). Pakistan: The culture. Crabtree Publishing Company. ISBN 9780778793489.

- ^ "Pakistan Almanac". Royal Book Company. 23 May 2017 – via Google Books.

- ^ 펀자브 이야기. Digital.library.upenn.edu .

- ^ 필루: 미르자-사히반의 전설의 첫 번째 내레이터. Hrisouthasian.org .

- ^ 2016년 공식 공휴일 – 파키스탄 펀자브 정부 (2016)

- ^ 공식 공휴일 2016년 9월 1일 파키스탄 신드 카라치 메트로폴리탄 웨이백 머신에서 보관

- ^ 1961년 인도 인구조사: 펀자브. 출판물 관리

- ^ Jacqueline Suthren Hirst; John Zavos (2013). Religious Traditions in Modern South Asia. Routledge. p. 274. ISBN 978-1-136-62668-5.Jacqueline Suthren Hirst; John Zavos (2013). Religious Traditions in Modern South Asia. Routledge. p. 274. ISBN 978-1-136-62668-5.이둘피타르, 람잔 이둘피타르, 인도 축제일

- ^ Tej Bhatia (2013). Punjabi. Routledge. pp. 209–212. ISBN 978-1-136-89460-2.

- ^ 재미의 금지, IRFAN HUSAIN, Dawn, 2017년 2월 18일

- ^ 바리케이드가 쳐진 무슬림의 마음, 사바 나크비(2016년 8월 28일), 인용: "이전에는 무슬림 마을 사람들이 힌두교 축제에 참여했다; 이제 그들은 그것이 하람이 될 것이라고 생각하므로 멀리 떨어지십시오. 다르가를 방문하는 것도 하라암입니다."

- ^ Eltringham, Nigel; Maclean, Pam (2014). Remembering Genocide. New York: Routledge. p. 'No man's land'. ISBN 978-1-317-75421-3. Retrieved 12 November 2016.

- ^ Marshall, Stewart; Taylor, Wal; Yu, Xinghuo (2005). Encyclopedia of Developing Regional Communities With Information And Communication Technology. Idea Group. p. 409. ISBN 978-1-59140-791-1. Retrieved 12 November 2016.

- ^ Giorgio Shani (2007). Sikh Nationalism and Identity in a Global Age. Routledge. pp. 1–8, 86–88. ISBN 978-1-134-10189-4.

메모들

- ^ Michaels (2004, p. 38) CITEREF ( "힌두교에서 베다 종교의 유산은 일반적으로 과대평가됩니다. 신화의 영향력은 실로 대단하지만, 종교 용어는 상당히 변했습니다: 힌두교의 모든 핵심 용어는 베다어에 존재하지 않거나 전혀 다른 의미를 가지고 있습니다. 베다의 종교는 행위(카르마)에 대한 응보와 함께 영혼의 윤리적 이동, 세상의 순환적 파괴, 또는 일생 동안의 구원에 대한 생각을 알지 못합니다(지반묵티; 목사; 열반); 세상을 환상으로 보는 생각(마야)은 고대 인도의 곡물과 어긋났음에 틀림없습니다. 그리고 전능한 창조신은 아르그베다의 후기 찬송가에서만 출현합니다. 또한 베다 종교는 카스트 제도, 과부의 불태우기, 재혼 금지, 신과 사원의 모습, 푸자 숭배, 요가, 순례, 채식주의, 소의 거룩함, 삶의 단계의 교리(아사극)를 알지 못했고, 그들이 시작할 때만 알고 있었습니다. 따라서 베다 종교와 힌두 종교 사이에 전환점이 생기는 것은 정당한 일입니다."

Jamison, Stephanie; Witzel, Michael (1992). "Vedic Hinduism" (PDF). Harvard University. p. 3.Jamison, Stephanie; Witzel, Michael (1992). "Vedic Hinduism" (PDF). Harvard University. p. 3."... 이 시기를 베다 힌두교라고 부르는 것은 용어상 모순인데, 베다 종교는 우리가 일반적으로 힌두교라고 부르는 것과 매우 다르기 때문입니다 – 적어도 고대 히브리어 종교가 중세와 현대 기독교 종교와 마찬가지로 말입니다. 하지만, 베다 종교는 힌두교의 전신으로서 대우받을 수 있습니다."

Halbfass 1991 참조, 페이지 1-2 CITEREFHalbfass - ^ 우르두어, 고전 힌디어 및 영어 사전: 차크는 페르시아어 "چاك 차크, 균열, 틈, 임대료, 슬릿, 좁은 입구(의도적으로 옷에 남겨짐)"에서 유래되었습니다.

서지학

- Dyson, Tim (2018), A Population History of India: From the First Modern People to the Present Day, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-882905-8

추가읽기

- 모히니 굽타, 펀자브 문화와 역사 백과사전 – 1권 (펀자브의 창) [하드커버], ISBN 978-81-202-0507-9

- Iqbal Singh Dhillion, 펀자브의 민속 춤 ISBN 978-81-7116-220-8

- 펀자브 문화: 펀자브어, 방그라, 펀자브족, 카르바 추트, 킬라 라이푸르 체육대회, 로리, 펀자브 다바, ISBN 978-1-157-61392-3

- 캄라 C. 아리안, 펀자브의 문화유산 ISBN 978-81-900002-9-1

- 샤피 아킬, 펀자브 지방에서 전해지는 인기 민담 ISBN 978-0-19-547579-1

- 펀자브족 설화집 온라인북

- 구어판 자바비: 초급자를 위한 코스(구어 시리즈) ISBN 978-0-415-10191-2

- 길마틴, 데이빗. 제국과 이슬람: 펀자브와 파키스탄 만들기. Univ of California Press (1988), ISBN 0-520-06249-3.

- Growal, J.S. 그리고 Gordon Johnson. 펀자브의 시크교도 (인도의 새로운 케임브리지 역사). 캠브리지 대학 출판부; 재인쇄판(1998), ISBN 0-521-63764-3

- 라티프, 사이드. 판잡의 역사. Kalyani (1997), ISBN 81-7096-245-5.

- Sekhon, Iqbal S. 펀자브인들: 사람들, 그들의 역사, 문화 그리고 기업. Delhi, Cosmo, 2000, 3 Vols., ISBN 81-7755-051-9.

- 싱, 구르하팔. 인도의 민족갈등 : 펀자브의 사례-연구 팔그레이브 맥밀런 (2000).

- 싱, 구르하팔(편집자), 이안 탈보트(편집자). 펀자브 아이덴티티: 연속성과 변화. 남아시아북스(1996), ISBN 81-7304-117-2.

- 싱, 쿠쉬원트. 시크교도의 역사 – 1권.옥스퍼드 대학교 출판부, ISBN 0-19-562643-5

- 스틸, 플로라 애니. 펀자브 이야기 : 사람들이 들려준 이야기 (Oxford in Asia Historical Reprints). Oxford University Press, U.S. New Ed 에디션(2002), ISBN 0-19-579789-2.

- 탄돈, 프라카쉬, 모리스 징킨. Punjabi Century 1857–1947, University of California Press (1968), ISBN 0-520-01253-4.

- 남아시아와 서남아시아의 DNA 경계, BMC Genetics 2004, 5:26

- 동판자비 민족학

- 민족학 서부판자비

- Kivisild, T; Rootsi, S; Metspalu, M; Mastana, S; Kaldma, K; Parik, J; Metspalu, E; Adojaan, M; Tolk, H. V; Stepanov, V; Gölge, M; Usanga, E; Papiha, S. S; Cinnioğlu, C; King, R; Cavalli-Sforza, L; Underhill, P. A; Villems, R (2003). "The Genetic Heritage of the Earliest Settlers Persists Both in Indian Tribal and Caste Populations" (PDF). Am. J. Hum. Genet. 72 (2): 313–332. doi:10.1086/346068. PMC 379225. PMID 12536373. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 February 2006.

- Talib, Gurbachan (1950). Muslim League Attack on Sikhs and Hindus in the Punjab 1947. India: Shiromani Gurdwara Prabandhak Committee.온라인 1 온라인 2 온라인 3 (이 책의 무료 사본은 이 무료 "온라인 북"의 포함된 "온라인 소스" 중 어느 3개에서든지 읽을 수 있습니다.)

- R.M. 초프라의 펀자브 유산, 1997, 펀자브 브래드리, 캘커타.

- 펀자브 마을의 펀자브 사회와 일상 모습 shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in

외부 링크

위키미디어 커먼즈의 펀자브족(민족) 관련 미디어

위키미디어 커먼즈의 펀자브족(민족) 관련 미디어