흥분제

Stimulant

각성제(중추신경계 자극제, 또는 정신자극제, 또는 구어체로 어퍼)는 뇌와 척수의 활동을 증가시키는 약물의 한 종류입니다. 경계, 주의, 동기, 인지, 기분 및 신체적 수행을 향상시키는 등 다양한 목적으로 사용됩니다. 가장 흔한 자극제는 카페인, 니코틴, 암페타민, 코카인, 모다피닐입니다.

자극제는 뉴런 사이의 시냅스에서 도파민, 노르에피네프린, 세로토닌, 히스타민 및 아세틸콜린과 같은 특정 신경 전달 물질의 수준에 영향을 주어 작동합니다. 이러한 신경전달물질은 각성, 보상, 학습, 기억, 감정 등 다양한 기능을 조절합니다. 자극제는 가용성을 높임으로써 용량, 투여 경로 및 개별 요인에 따라 가벼운 자극에서 행복감에 이르기까지 다양한 효과를 낼 수 있습니다.

자극제는 의료 목적과 비의료 목적 모두에서 오랜 사용 역사를 가지고 있습니다. 그들은 기면증, 주의력결핍 과잉행동장애(ADHD), 비만, 우울증, 피로와 같은 다양한 상태를 치료하는 데 사용되었습니다. 그것들은 또한 학생, 운동선수, 근로자 및 군인과 같은 다양한 그룹의 사람들에 의해 레크리에이션 약물, 경기력 향상제 및 인지력 향상제로 사용되었습니다.

그러나 자극제는 중독, 내성, 금단, 정신병, 불안, 불면증, 심혈관계 문제, 신경독성과 같은 잠재적인 위험과 부작용도 있습니다. 흥분제의 오남용은 과다 복용, 의존, 범죄, 폭력과 같은 심각한 건강 및 사회적 결과를 초래할 수 있습니다. 따라서 각성제 사용은 대부분의 국가에서 법과 정책으로 규제되고 있으며, 경우에 따라 의료 감독과 처방이 필요합니다.

정의.

각성제는 중추신경계와 신체의 활동을 증가시키는 약물,[1] 기분 좋고 활력을 주는 약물 또는 공감 효과가 있는 약물을 포함한 많은 약물을 포괄하는 포괄적인 용어입니다.[2] 교감신경계의 작용을 모방하거나 모방하는 효과를 공감모방효과라고 합니다. 교감신경계는 심장박동수, 혈압, 호흡수를 증가시키는 등 신체가 활동할 수 있도록 준비시키는 신경계의 한 부분입니다. 자극제는 교감신경계에서 방출되는 천연 화학물질과 같은 수용체를 활성화시켜 비슷한 효과를 일으킬 수 있습니다.[3]

영향들

급성

주의력 결핍 과잉 행동 장애(ADHD) 환자에게 투여되는 것과 같은 치료 용량의 자극제는 집중력, 활력, 사교성, 성욕을 증가시키고 기분을 상승시킬 수 있습니다. 그러나, 고용량일 경우, 자극제는 실제로 Yerkes-Dodson 법칙의 원리인 집중력을 감소시킬 수 있습니다. Yerkes-Dodson Law는 스트레스가 성과에 어떻게 영향을 미치는지를 설명하는 심리학 이론입니다.[4] 그 이론은 사람들이 더 잘 수행하도록 돕는 최적의 수준의 스트레스가 있지만, 너무 많거나 적은 스트레스는 수행을 손상시킬 수 있다고 말합니다. 이 이론은 거꾸로 U자형 곡선으로 설명할 수 있으며, 여기서 곡선의 피크는 최적의 스트레스 수준과 성능을 나타냅니다.[4] 이 이론은 1908년 심리학자 로버트 예크스와 존 딜링엄 도슨이 쥐 실험을 바탕으로 개발했습니다.[4] ADHD 치료에 사용되는 약물과 같이 중추신경계를 자극하는 약물은 적절한 용량으로 복용했을 때 집중력과 다른 기분과 행동 측면을 향상시킬 수 있습니다. 그러나 이러한 약물은 고용량으로 복용할 경우 반대의 영향을 미치고 집중력을 저하시킬 수 있습니다. 용량이 높을수록 과도한 스트레스가 발생하여 최적의 수준을 초과하여 성능에 해를 끼치기 때문입니다. 고용량에서는 흥분제가 행복감, 활력 및 수면 필요성 감소를 유발할 수도 있습니다. 전부는 아니지만 많은 자극제가 에르고제닉 효과를 가지고 있습니다. "에르고제닉"이란 "신체 성능 향상"을 의미합니다.[5] 에르고제닉 효과는 신체적 성능이나 지구력을 향상시키는 효과입니다. 예를 들어, 어떤 약이 더 빨리 달리게 하거나, 더 무겁게 들어올리거나, 더 오래 지속되면 에르고제닉 효과가 있다고 합니다. 에페드린, 슈도에페드린, 암페타민, 메틸페니데이트와 같은 약물은 에르고제닉 효과가 잘 기록되어 있는 반면 코카인은 그 반대의 효과가 있습니다.[6] 자극제, 특히 모다피닐, 암페타민 및 메틸페니데이트의 신경인지 강화 효과는 일부 연구에 의해 건강한 청소년에서 보고되었으며 [7]특히 학업의 맥락에서 대학생들 사이에서 사용하기 위해 불법 약물 사용자들 사이에서 일반적으로 인용되는 이유입니다.[7] 그러나 이러한 연구의 결과는 결정적이지 않습니다: 건강한 청소년들 사이에서 자극제의 잠재적인 전반적인 신경 인지적 이점을 평가하는 것은 인구 내의 다양성, 인지 작업 특성의 다양성 및 연구의 복제 부재로 인해 어렵습니다.[7] 수면이 부족한 건강한 사람들의 모다피닐의 인지 향상 효과에 대한 연구는 엇갈린 결과를 나타냈는데, 몇몇 연구는 주의력과 실행 기능에서 약간의 개선을 시사하는 반면 다른 연구들은 유의미한 이점을 보이지 않거나 심지어 인지 기능의 감소를 보여줍니다.[8][9][10]

경우에 따라서는 흥분성 정신병, 편집증, 자살 관념 등의 정신 의학적 현상이 나타날 수도 있습니다. 급성 독성은 살인, 편집증, 공격적인 행동, 운동 기능 장애 및 전문가와 관련이 있는 것으로 알려졌습니다. 급성 흥분제 독성과 관련된 폭력적이고 공격적인 행동은 부분적으로 편집증에 의해 유발될 수 있습니다.[11] 각성제로 분류되는 대부분의 약물은 교감신경계의 교감신경분지를 자극하는 것입니다. 이것은 균혈증, 심박수 증가, 혈압, 호흡수 및 체온과 같은 효과로 이어집니다.[2] 이러한 변화가 병적으로 되면 부정맥, 고혈압, 온열질환 등으로 불리며 횡문근융해증, 뇌졸중, 심정지, 발작 등으로 이어질 수 있습니다. 그러나 급성 흥분제 독성의 잠재적으로 치명적인 결과의 기초가 되는 메커니즘의 복잡성을 고려할 때 어떤 용량이 치명적일 수 있는지 결정하는 것은 불가능합니다.[12]

만성적

현재 각성제를 복용하고 있는 인구가 많다는 점을 고려할 때, 각성제의 효과에 대한 평가는 관련이 있습니다. 처방 흥분제의 심혈관 효과를 체계적으로 검토한 결과 소아에서는 연관성이 발견되지 않았지만 처방 흥분제 사용과 허혈성 심장마비 사이의 상관관계를 발견했습니다.[13] 4년에 걸쳐 검토한 결과 각성제 치료의 부정적인 효과는 거의 없는 것으로 나타났지만, 보다 장기적인 연구가 필요하다고 강조했습니다.[14] ADHD 환자의 1년 동안의 처방 자극제 사용을 검토한 결과, 심혈관계 부작용은 일시적인 혈압 상승에만 국한된 것으로 나타났습니다.[15] 유아기 ADHD 환자의 각성제 치료 시작은 사회적 및 인지적 기능과 관련하여 성인기까지 이점을 제공하는 것으로 보이며 비교적 안전한 것으로 보입니다.[16]

처방 자극제의 남용(의사의 지시를 따르지 않음) 또는 불법 자극제의 남용은 많은 부정적인 건강 위험을 수반합니다. 코카인의 남용은 투여 경로에 따라 심장 호흡기 질환, 뇌졸중, 패혈증의 위험을 증가시킵니다.[17] 일부 효과는 투여 경로에 따라 달라지며 정맥 내 사용은 C형 간염, HIV/AIDS와 같은 많은 질병의 전염과 감염, 혈전증 또는 가성 동맥류와 같은 잠재적인 의료 응급 상황과 관련이 있는 [18]반면 흡입은 하부 호흡기 감염, 폐암의 증가와 관련이 있을 수 있습니다. 그리고 폐 조직의 병리학적 제한.[19] 코카인은 또한 자가면역질환의[20][21][22] 위험을 증가시키고 코 연골을 손상시킬 수 있습니다. 필로폰의 남용은 도파민 신경세포의 현저한 퇴화뿐만 아니라 유사한 효과를 발생시켜 파킨슨병의 위험을 증가시킵니다.[23][24][25][26]

의료용

흥분제는 처방약으로 사용될 뿐만 아니라 (법적이든 불법적이든) 경기력 향상 또는 오락용 약물로 처방되지 않은 채 전 세계적으로 널리 사용되고 있습니다. 마약 중에서 자극제는 효과가 끝날 때 눈에 띄는 충돌을 일으키거나 내려갑니다. 2013년 기준으로 가장 많이 처방된 자극제는 리스덱삼페타민(Vyvanse), 메틸페니데이트(Ritalin), 암페타민(Adderall)이었습니다.[27] 2015년 1년 동안 코카인을 사용한 세계 인구의 비율은 0.4%로 추정되었습니다. "암페타민 및 처방 자극제"(암페타민 및 필로폰을 포함한 "암페타민" 포함) 범주의 경우 0.7%, MDMA의 경우 0.4%[28]의 값을 보였습니다.

자극제는 비만, 수면장애, 기분장애, 충동조절장애, 천식, 코막힘, 코카인의 경우 국소마취제로 많은 질환에 사용되어 왔습니다.[29] 비만 치료에 사용되는 약물은 난소학이라고 불리며 일반적으로 흥분제의 일반적인 정의를 따르는 약물을 포함하지만 칸나비노이드 수용체 길항제 같은 다른 약물도 이 그룹에 속합니다.[30][31] 우생은 기면증과 같은 과도한 주간 졸림을 특징으로 하는 수면장애의 관리에 사용되며, 모다피닐, 피톨리산트와 같은 자극제를 포함합니다.[32][33] 흥분제는[34] ADHD와 같은 충동 조절 장애에 사용되고 주요 우울 장애와 같은 기분 장애에서 라벨을 벗어 에너지를 증가시키고 집중력을 높이며 기분을 상승시킵니다.[35] 경구로 천식 [36]치료에 에피네프린, 테오필린[37], 살부타몰 등의 흥분제를 사용해 왔으나 전신 부작용이 적어 현재는 흡입형 아드레날린제를 선호하고 있습니다. 슈도에페드린은 일반적인 감기, 부비동염, 건초열 및 기타 호흡기 알레르기로 인한 코 또는 부비동 충혈을 완화하는 데 사용되며, 귀 염증 또는 감염으로 인한 귀 충혈을 완화하는 데에도 사용됩니다.[38][39]

우울증.

흥분제는 1930년대 암페타민의 도입 이후 시작된 우울증 치료에 사용된 첫 번째 종류의 약물 중 하나였습니다.[40][41][42] 그러나, 그들은 1950년대에 전통적인 항우울제가 도입된 후 우울증 치료를 위해 대부분 버려졌습니다.[40][41] 이에 이어 최근에는 우울증에 대한 자극제에 대한 관심이 다시 높아지고 있습니다.[43][44]

자극제는 빠르게 작용하고 뚜렷하지만 일시적이고 짧은 수명의 기분 상승을 만들어냅니다.[45][46][43][41] 이와 관련하여 지속적으로 투여하였을 때 우울증 치료에 최소한의 효과가 있습니다.[45][46] 또한 암페타민의 기분 개선 효과에 대한 내성으로 인해 용량 증가 및 의존성이 발생했습니다.[44] 지속적인 투여로 우울증에 대한 효능은 미미하지만 여전히 위약에 비해 통계적 유의성에 도달할 수 있으며 기존 항우울제와 유사한 크기의 이점을 제공할 수 있습니다.[47][48][49][50] 흥분제의 단기적인 기분 개선 효과의 이유는 불분명하지만, 빠른 내성과 관련이 있을 수 있습니다.[45][46][41][51] 자극제의 효과에 대한 내성은 동물과[51][52][53][54] 사람 모두에서 연구되고 특성화되었습니다.[55][56][57][58] 흥분제 금단현상은 주요 우울장애와 증상이 현저하게 유사합니다.[59][51][60][61]

화학

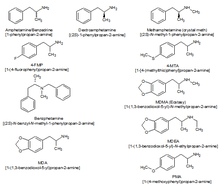

약물이 차지하는 클래스의 수가 많고 여러 클래스에 속할 수 있다는 사실 때문에 흥분제를 분류하는 것은 어렵습니다. 예를 들어, 엑스터시는 치환된 메틸렌디옥시페네틸아민, 치환된 암페타민, 결과적으로 치환된 페네틸아민으로 분류될 수 있습니다.[citation needed]

자극제를 언급할 때 모약(예: 암페타민)은 항상 단수로[according to whom?] 표현되며, 모약(치환 암페타민) 앞에 "치환"이라는 단어가 배치됩니다.

주요 자극제 수업으로는 페네틸아민과 그들의 딸 수업은 대체 암페타민이 있습니다.[62][63]

암페타민(클래스)

치환 암페타민은 암페타민 구조를 기반으로 하는 화합물의 한 종류로서,[64] 암페타민 코어 구조 내의 하나 이상의 수소 원자를 치환기로 치환 또는 치환하여 형성되는 모든 유도체 화합물을 포함하는 것을 특징으로 하는 화합물.[64][65][66] Examples of substituted amphetamines are amphetamine (itself),[64][65] methamphetamine,[64] ephedrine,[64] cathinone,[64] phentermine,[64] mephentermine,[64] bupropion,[64] methoxyphenamine,[64] selegiline,[64] amfepramone,[64] pyrovalerone,[64] MDMA (ecstasy), and DOM (STP). 이 부류의 많은 약물은 주로 미량아민 관련 수용체 1(TAAR1)을 활성화함으로써 작용하며,[67] 이는 도파민, 노르에피네프린 및 세로토닌의 재흡수 억제 및 유출, 또는 방출을 유발합니다.[67] 일부 치환된 암페타민의 추가적인 메커니즘은 VMAT2를 통한 모노아민 신경전달물질의 소포체 저장소의 방출이며, 따라서 시냅스 전 뉴런의 세포질 또는 세포 내 유체에서 이러한 신경전달물질의 농도를 증가시킵니다.[68]

암페타민형 자극제는 치료 효과를 위해 자주 사용됩니다. 의사들은 주요 우울증을 치료하기 위해 암페타민을 처방하기도 하는데, 여기서 피험자들은 전통적인 SSRI 약물에 잘 반응하지 않지만,[citation needed] 이러한 사용을 뒷받침하는 증거는 빈약하거나 혼재되어 있습니다.[44] 특히, 주요 우울증 치료에서 SSRI 또는 SNRI에 대한 보조제로서 리스덱삼페타민(암페타민에 대한 전구약물)에 대한 최근의 두 개의 대규모 III상 연구는 위약 효과에 비해 더 이상의 이점을 보여주지 않았습니다.[69] ADHD와 관련된 증상을 조절하는 데 있어 Adderall(암페타민과 덱스트로암페타민의 염 혼합물)과 같은 약물의 효과를 입증한 많은 연구가 있습니다. 대체 암페타민은 가용성과 빠른 작용 효과로 인해 남용의 주요 후보입니다.[70]

코카인 유사체

수백 가지의 코카인 유사체가 만들어졌는데, 그들 모두는 보통 트로판의 3개의 탄소에 연결된 벤질옥시를 유지하고 있습니다. 다양한 변형은 벤젠 고리에 대한 치환뿐만 아니라 트로판 2 탄소에 대한 일반 카르복실레이트를 대체하는 첨가 또는 치환을 포함합니다. 기술적으로 유사하지 않은 코카인과 유사한 구조 활성 관계를 가진 다양한 화합물도 개발되었습니다.

작용기전

대부분의 자극제는 카테콜아민 신경 전달을 강화하여 활성화 효과를 발휘합니다. 카테콜아민 신경 전달 물질은 주의력, 각성, 동기 부여, 작업 현저성 및 보상 기대와 관련된 조절 경로에 사용됩니다. 고전적인 자극제는 이러한 카테콜아민의 흡수를 차단하거나 유출을 자극하여 회로의 활성을 증가시킵니다. 일부 자극제, 특히 감정이입 및 환각 효과가 있는 자극제도 세로토닌 전달에 영향을 미칩니다. 일부 암페타민 유도체 및 특히 요힘빈과 같은 일부 자극제는 조절 자가수용체를 길항하여 부정적 피드백을 감소시킬 수 있습니다.[71] 부분적으로 에페드린과 같은 아드레날린 작용제는 아드레날린 수용체에 직접적으로 결합하고 활성화함으로써 교감신경 효과를 생성합니다.

약물이 활성화 효과를 이끌어낼 수 있는 간접적인 작용 메커니즘도 더 많습니다. 카페인은 아데노신 수용체 길항제로 뇌에서 카테콜아민의 전달을 간접적으로만 증가시킵니다.[72] 피톨리산트는 히스타민 3(H3) 수용체 역작용제입니다. 히스타민 3(H3) 수용체가 주로 자가수용체로 작용함에 따라 피톨리산트는 히스타민성 뉴런에 대한 부정적 피드백을 감소시켜 히스타민성 전달을 강화합니다.

기면증 및 기타 수면 장애의 증상을 치료하기 위한 모다피닐과 같은 일부 자극제의 정확한 작용 메커니즘은 아직 알려지지 않았습니다.[73][74][75][76][77]

눈에 띄는 자극제

암페타민

암페타민은 주의력결핍 과잉행동장애(ADHD)와 기면증 치료에 승인된 페네틸아민 계열의 강력한 중추신경계(CNS) 자극제입니다.[78] 암페타민은 또한 성능 및 인지 향상제로, 그리고 오락적으로 진핵제 및 행복감제로 사용됩니다.[79][80][81][82] 많은 국가에서 처방되는 의약품이지만 암페타민의 무단 소지와 유통은 통제되지 않거나 과중한 사용과 관련된 건강상의 위험이 크기 때문에 엄격하게 통제되는 경우가 많습니다.[83][84] 결과적으로 암페타민은 비밀 실험실에서 불법으로 제조되어 사용자에게 밀매되고 판매됩니다.[85] 전 세계적으로 마약과 마약의 전조 발작을 기준으로 불법 암페타민 생산과 밀매는 필로폰보다 훨씬 덜 만연해 있습니다.[85]

최초의 의약품 암페타민은 벤제드린으로 다양한 질환을 치료하는 데 사용되는 흡입기 브랜드입니다.[86][87] 덱스트로로타리 이성질체가 더 큰 자극성을 갖기 때문에 벤제드린은 덱스트로암페타민의 전부 또는 대부분을 포함하는 제형을 선호하여 점차 중단되었습니다. 현재 일반적으로 혼합 암페타민 염, 덱스트로암페타민, 리스덱삼페타민으로 처방되고 있습니다.[86][88]

암페타민은 노르에피네프린-도파민 방출제(NDRA)입니다. 도파민과 노르에피네프린 수송체를 통해 뉴런으로 들어가 TAAR1을 활성화하고 VMAT2를 억제하여 신경전달물질 유출을 촉진합니다.[67] 치료 용량에서 이는 행복감, 성욕 변화, 각성 증가, 인지 조절 향상과 같은 정서적, 인지적 효과를 유발합니다.[80][81][89] 마찬가지로 반응시간 감소, 피로저항, 근력 증가 등의 물리적 효과를 유도합니다.[79] 대조적으로, 암페타민의 초치료 용량은 인지 기능을 손상시키고 빠른 근육 파괴를 유발할 가능성이 있습니다.[78][80][90] 매우 높은 용량은 정신병(예: 망상 및 편집증)을 유발할 수 있으며, 이는 장기간 사용 중에도 치료 용량에서 매우 드물게 발생합니다.[91][92] 레크리에이션 용량은 일반적으로 규정된 치료 용량보다 훨씬 크기 때문에 레크리에이션 사용은 치료용 암페타민 사용 시 거의 발생하지 않는 의존성과 같은 심각한 부작용의 위험이 훨씬 더 큽니다.[78][90][91]

카페인

카페인은 커피, 차, 코코아 또는 초콜릿에서 자연적으로 발견되는 크산틴 계열의 화학 물질에 속하는 흥분성 화합물입니다. 많은 탄산음료에 포함되어 있을 뿐만 아니라 에너지 음료에도 더 많은 양이 포함되어 있습니다. 카페인은 세계에서 가장 널리 사용되는 향정신성 약물이자 단연코 가장 흔한 흥분제입니다. 북미에서는 성인의 90%가 매일 카페인을 섭취하고 있습니다.[93]

일부 관할 구역에서는 카페인의 판매와 사용을 제한합니다. 미국에서는 과다복용과 사망의 위험성 때문에 FDA가 개인 소비용으로 순수하고 고농도의 카페인 제품의 판매를 금지했습니다.[94] 호주 정부가 급성 카페인 독성으로 젊은 남성이 사망하자 개인 소비용 순수·고농축 카페인 식품 판매를 금지한다고 발표했습니다.[95][96]캐나다에서, 캐나다 보건부는 에너지 드링크의 카페인 양을 1회 제공량당 180 mg으로 제한하고 이 제품들에 대한 경고 라벨과 기타 안전 조치를 요구할 것을 제안했습니다.[95]

카페인은 일반적으로 1차 성분의 효과를 높이거나 부작용([97]특히 졸음) 중 하나를 줄이기 위한 목적으로 일부 약물에 포함되기도 합니다.[98] 표준화된 용량의 카페인이 포함된 정제도 널리 사용할 수 있습니다.[99]

카페인의 작용 메커니즘은 아데노신 수용체를 억제하여 자극 효과를 내기 때문에 많은 자극제와 다릅니다.[100] 아데노신 수용체는 졸음과 수면의 큰 동인으로 생각되며, 각성이 길어질수록 그 작용이 증가합니다.[101] 카페인은 동물 모델에서 선조체 도파민을 증가시킬 [102]뿐만 아니라 도파민 수용체에 대한 아데노신 수용체의 억제 효과를 억제하는 [103]것으로 밝혀졌지만 인간에게 미치는 영향은 알려져 있지 않습니다. 대부분의 자극제와 달리 카페인은 중독성이 없습니다. NIDA 연구 모노그래프에 발표된 약물 남용 책임에 대한 연구에 따르면 카페인은 강화 자극제가 아닌 것으로 보이며 실제로 어느 정도의 혐오감이 발생할 수 있습니다.[104] 대규모 전화 조사에서 11%만이 의존성 증상을 보고했습니다. 그러나 실험실에서 사람들이 실험을 했을 때 의존성을 주장하는 사람들의 절반만이 실제로 의존성을 경험했으며, 의존성을 생산하는 카페인의 능력에 의문을 제기하고 사회적 압력이 각광을 받았습니다.[105]

커피 섭취는 전반적인 암 발생 위험을 낮추는 것과 관련이 있습니다.[106] 이는 주로 간세포암과 자궁내막암의 위험도가 감소한 데 따른 것이지만, 대장암에도 약간의 영향을 미칠 수 있습니다.[107] 다른 종류의 암에 대한 보호 효과는 크지 않은 것으로 보이며, 커피를 많이 섭취하면 방광암의 위험이 높아질 수 있습니다.[107] 알츠하이머병에 대한 카페인의 보호 효과는 가능하지만, 그 증거는 확정적이지 않습니다.[108][109][110] 적당한 커피 섭취는 심혈관계 질환의 위험을 감소시킬 수 있고,[111] 제2형 당뇨병의 위험을 다소 감소시킬 수 있습니다.[112] 하루 1~3잔의 커피를 마시는 것은 커피를 거의 마시지 않거나 마시지 않는 것에 비해 고혈압 위험에 영향을 미치지 않습니다. 그러나 하루에 2-4잔을 마시는 사람들은 약간 위험이 높아질 수 있습니다.[113] 카페인은 녹내장 환자의 안압을 증가시키지만 정상인에게는 영향을 미치지 않는 것으로 보입니다.[114] 간경변으로부터 사람들을 보호할 수 있습니다.[115] 커피가 아이의 성장을 저해한다는 증거는 없습니다.[116] 카페인은 두통 치료에 사용되는 것을 포함한 일부 약물의 효과를 증가시킬 수 있습니다.[117] 카페인은 높은 고도에 도달하기 몇 시간 전에 복용하면 급성 산병의 심각성을 줄일 수 있습니다.[118]

에페드린

에페드린은 잘 알려진 약물인 페닐프로판올아민과 필로폰, 그리고 중요한 신경 전달 물질인 에피네프린(아드레날린)과 분자 구조가 유사한 동정적 모방 아민입니다. 에페드린은 일반적으로 흥분제, 식욕억제제, 집중보조제, 그리고 마취와 관련된 저혈압을 치료하기 위해 사용됩니다.

화학적으로 말하면, 에페드라속(Ephedra, Ephedraceae)의 다양한 식물에서 발견되는 페닐아민 골격을 가진 알칼로이드입니다. 주로 아드레날린 수용체에 대한 노르에피네프린(noradrenaline)의 활성을 증가시킴으로써 작용합니다.[119] 가장 일반적으로 염산염 또는 황산염으로 판매됩니다.

전통적인 중국 의학(TCM)에서 사용되는 허브 마흐엉(Ephedra sinica)은 에페드린과 슈도에페드린을 주요 활성 성분으로 함유하고 있습니다. 다른 에페드라 종의 추출물을 함유한 다른 허브 제품도 마찬가지일 수 있습니다.

MDMA

3,4-메틸렌다이옥시메탐페타민(MDMA, 엑스터시 또는 몰리)은 암페타민 계열의 행복감, 감정이입원 및 흥분제입니다.[120] 일부 심리치료사들이 치료의 보조제로 잠시 사용한 이 약물은 오락적으로 인기를 끌었고 DEA는 MDMA를 스케줄 I 통제 물질로 등재하여 대부분의 의학 연구와 응용을 금지했습니다. MDMA는 곤충을 유발하는 특성으로 알려져 있습니다. MDMA의 자극 효과로는 고혈압, 식욕부진( 식욕부진), 행복감, 사회적 억제, 불면증(깨움증 강화/잠을 잘 수 없음), 에너지 향상, 각성 증가, 땀 증가 등이 있습니다. MDMA는 암페타민과 같은 고전적 자극제에 비해 세로토닌성 전달을 훨씬 더 향상시킵니다. MDMA는 크게 중독성이 있거나 의존성이 형성되지 않는 것으로 보입니다.[121]

MDMA의 상대적인 안전성 때문에 데이비드 너트(David Nutt)와 같은 일부 연구자들은 MDMA가 "equasy" 또는 "Equine Addiction Syndrome"라고 부르는 조건인 승마보다 28배 덜 위험하다는 풍자적인 기사를 쓰면서 스케줄링 수준을 비판했습니다.[122]

MDPV

메틸렌디옥시피로발레론(MDPV)은 노르에피네프린-도파민 재흡수 억제제(NDRI)로 작용하는 흥분제 특성을 가진 정신 활성 약물입니다.[123] 이것은 1960년대에 베링거 인겔하임의 한 팀에 의해 처음 개발되었습니다.[124] MDPV는 2004년경 디자이너 의약품으로 판매된 것으로 보고되기 전까지 잘 알려지지 않은 자극제로 남아 있었습니다. MDPV가 함유된 목욕용 소금으로 표시된 제품은 이전에 향으로 향신료와 K2의 마케팅과 유사하게 미국의 주유소와 편의점에서 오락용 의약품으로 판매되었습니다.[125][126]

MDPV 사용으로 인한 심리적, 신체적 피해가 발생했습니다.[127][128]

메페드론

메페드론은 암페타민과 카티논 계열의 합성 흥분제 약물입니다. 비속어 이름에는 드론과[129] MCAT가 포함됩니다.[130] 중국에서 제조되는 것으로 보고되어 있으며 동아프리카의 핫 식물에서 발견되는 카티논 화합물과 화학적으로 유사합니다. 정제나 분말 형태로 나오는데, 사용자가 삼키거나 코를 골거나 주사할 수 있어 MDMA, 암페타민, 코카인과 비슷한 효과를 냅니다.

메페드론은 1929년에 처음 합성되었지만 2003년에 재발견되기 전까지 널리 알려지지 않았습니다. 2007년까지 메페드론은 인터넷에서 판매될 수 있다고 보고되었고, 2008년에는 법 집행 기관들이 메페드론에 대해 알게 되었고, 2010년에는 유럽 대부분에서 보고되었으며, 특히 영국에서 널리 퍼졌습니다. 메페드론은 2008년 이스라엘에서 처음으로 불법화되었고, 그 해 말 스웨덴이 그 뒤를 이었습니다. 2010년에는 많은 유럽 국가에서 불법으로 만들어졌고, 2010년 12월에는 EU에서 불법으로 판결을 내렸습니다. 호주, 뉴질랜드, 미국 등에서는 다른 불법 약물의 유사체로 간주돼 연방 아날로그법과 유사한 법으로 통제가 가능합니다. 2011년 9월, 미국은 메페드론을 일시적으로 불법으로 분류했고, 2011년 10월부터 효력이 발생했습니다.

필로폰

필로폰(N-methyl-alpha-methylphenethylamine에서 계약)은 주의력결핍 과잉행동장애(ADHD)와 비만을 치료하는 데 사용되는 페네틸아민과 암페타민 계열의 강력한 정신자극제입니다.[131][132][133] 필로폰은 덱스트로로타리와 레보로타리의 두 가지 거울상이성질체로 존재합니다.[134][135] 덱스트로메탐페타민은 레보메탐페타민보다 더 강력한 중추신경계 자극제이지만 [90][134][135]둘 다 중독성이 있고 고용량에서도 동일한 독성 증상을 나타냅니다.[135] 잠재적인 위험성 때문에 거의 처방되지 않았지만, 필로폰 염산염은 미국 식품의약국(USFDA)에서 데옥신이라는 제품명으로 승인을 받았습니다.[132] 오락적으로 필로폰을 사용하여 성욕을 높이고 분위기를 띄우며 에너지를 증가시켜 일부 사용자는 며칠 연속으로 지속적으로 성행위를 할 수 있습니다.[132][failed verification][136][unreliable source?]

필로폰은 순수한 덱스트롬암페타민으로서 또는 오른손 분자와 왼손 분자의 동등한 부분(즉, 레보메탐페타민 50% 및 덱스트롬암페타민 50%)에서 불법적으로 판매될 수 있습니다.[136] 덱스트롬암페타민과 인종성 필로폰은 모두 미국에서 스케줄 II로 통제되는 물질입니다.[132] 또한, 필로폰의 생산, 유통, 판매 및 소지는 유엔 향정신성 물질 조약의 스케줄 II에 배치되어 있기 때문에 다른 많은 국가에서 제한되거나 불법입니다.[137][138] 반면, 레보메탐페타민은 미국에서 일반의약품입니다.[note 1]

저용량에서 필로폰은 기분을 상승시키고 피로한 사람들의 경계심, 집중력, 에너지를 증가시킬 수 있습니다.[90][132] 고용량에서는 정신병, 횡문근융해증, 뇌출혈을 유발할 수 있습니다.[90][132] 필로폰은 남용 및 중독 가능성이 높은 것으로 알려져 있습니다.[90][132] 오락적인 필로폰 사용은 정신병을 유발하거나, 일반적인 금단 기간을 넘어 수개월 동안 지속될 수 있는 금단 후 증후군을 유발할 수 있습니다.[141] 암페타민이나 코카인과 달리 필로폰은 인간에게 신경독성이 있어 중추신경계(CNS)의 도파민과 세로토닌 뉴런을 모두 손상시킵니다.[131][133] ADHD 환자의 특정 뇌부위를 개선할 수 있는 암페타민을 처방전 용량으로 장기간 사용하는 것과는 달리, 필로폰이 인간에게 장기간 사용함으로써 뇌손상을 일으킨다는 증거가 있고,[131][133] 이 손상에는 뇌구조 및 기능상의 악영향을 포함하고, 여러 뇌 영역의 회백질 부피 감소 및 대사 무결성 표지자의 불리한 변화와 같은 것.[142][143][133] 그러나 오락용 암페타민 복용량은 신경독성일 수도 있습니다.[144]

메틸페니데이트

메틸페니데이트는 ADHD 및 기면증 치료에 자주 사용되며 때로는 식이 제한 및 운동과 함께 비만을 치료하는 데 사용되는 흥분제 약물입니다. 치료 용량에서의 효과에는 초점 증가, 경계심 증가, 식욕 감소, 수면 필요성 감소 및 충동성 감소가 포함됩니다. 메틸페니데이트는 보통 오락적으로 사용되지 않지만, 사용했을 때 그 효과는 암페타민과 매우 유사합니다.

메틸페니데이트는 노르에피네프린 수송체(NET)와 도파민 수송체(DAT)를 차단하여 노르에피네프린-도파민 재흡수 억제제 역할을 합니다. 메틸페니데이트는 노르에피네프린 수송체보다 도파민 수송체에 대한 친화력이 높기 때문에 그 효과는 주로 도파민의 재흡수 억제로 인한 도파민 수치 상승에 기인하지만 노르에피네프린 수치의 증가도 약물에 의한 다양한 효과에 기여합니다.

메틸페니데이트는 리탈린을 비롯한 다수의 브랜드로 판매되고 있습니다. 다른 버전으로는 오래 지속되는 태블릿 콘체르타와 오래 지속되는 경피 패치 데이트라나가 있습니다.

코카인

코카인은 SNDRI입니다. 코카인은 볼리비아, 콜롬비아, 페루와 같은 남미 국가들의 산악 지역에서 자라는 코카 관목의 잎으로 만들어지는데, 이 지역은 주로 아이마라 사람들에 의해 재배되어 수세기 동안 사용되었습니다. 유럽, 북미 및 아시아 일부 지역에서 코카인의 가장 흔한 형태는 흰색 결정성 분말입니다. 코카인은 자극제이지만, 특히 안과에서 임상적 사용을 국소 마취제로 보고 있지만, 자극제 특성 때문에 보통 치료적으로 처방되지는 않습니다.[145] 대부분의 코카인 사용은 오락적이고 남용 가능성이 높기 때문에(암페타민보다 높음) 대부분의 관할 구역에서 판매와 소지가 엄격하게 통제됩니다. 코카인과 관련된 다른 트로파릴과 로메토판과 같은 트로파란 유도체 약물도 알려져 있지만 널리 판매되거나 오락적으로 사용되지는 않았습니다.[146]

니코틴

니코틴은 담배의 활성 화학 성분으로 담배, 시가, 씹는 담배, 니코틴 패치, 니코틴 껌, 전자 담배와 같은 금연 보조제를 포함한 많은 형태로 이용할 수 있습니다. 니코틴은 자극적이고 편안한 효과로 전 세계적으로 널리 사용되고 있습니다. 니코틴은 니코틴성 아세틸콜린 수용체의 작용을 통해 그 효과를 발휘하여 중뇌 보상 시스템에서 도파민 신경세포의 활성 증가와 같은 다중 다운스트림 효과를 발생시키고, 담배 성분 중 하나인 아세트알데히드는 뇌에서 모노아민 산화효소의 발현을 감소시킵니다.[147] 니코틴은 중독성이 있고 의존성이 형성됩니다. 니코틴의 가장 일반적인 공급원인 담배는 사용자와 자기 점수에 전반적으로 해를 끼치고 코카인보다 3%, 암페타민보다 13% 더 해를 끼치며, 다중 기준 결정 분석 결과 평가된 20개 약물 중 6번째로 해를 끼치는 것으로 나타났습니다.[148]

페닐프로판올아민

페닐프로판올아민(PPA; Accutrim; β-hydroxyamphetamine)은 입체이성질체 노레페드린 및 노르슈도에페드린으로 알려진 페닐프로판올아민 및 암페타민 화학 계열의 정신 활성 약물로, 흥분제, 탈충제 및 식욕 부진제로 사용됩니다.[149] 일반적으로 처방전 및 처방전 없이 기침과 감기 준비에 사용됩니다. 수의학에서는 프로팔린과 프로인이라는 상호로 개의 요실금을 조절하는 데 사용됩니다.

미국에서 PPA는 젊은 여성의 뇌졸중 위험 증가 가능성 때문에 더 이상 처방전 없이 판매되지 않습니다. 그러나 유럽의 일부 국가에서는 여전히 처방전이나 때로는 장외에서 구입할 수 있습니다. 캐나다에서는 2001년 5월 31일에 시장에서 철수했습니다.[150] 인도에서는 2011년 2월 10일 PPA와 그 제제의 인간 사용이 금지되었습니다.[151]

리스덱삼페타민

Lisdexamfetamine (Vyvanse 등)은 암페타민 형태의 약물로 ADHD 치료에 사용하기 위해 판매되고 있습니다.[152] 효과는 일반적으로 약 14시간 동안 지속됩니다.[153] 리스덱삼페타민은 자체적으로 비활성화되어 체내에서 덱스트로암페타민으로 대사됩니다.[56] 결과적으로 남용 가능성이 낮습니다.[56]

슈도에페드린

슈도에페드린은 페네틸아민과 암페타민 화학 계열의 공감 모방 약물입니다. 코/비강 해열제, 흥분제 [154]또는 각성 촉진제로 사용할 수 있습니다.[155]

염류 슈도에페드린 염산염 및 슈도에페드린 황산염은 단일 성분으로 또는 항히스타민제, 과이페닌, 덱스트로메토르판 및/또는 파라세타몰(아세트아미노펜) 또는 다른 NSAID(아스피린 또는 이부프로펜과 같은)와 조합되어 많은 처방전 없이 살 수 있는 제제에서 발견됩니다. 또한 필로폰 불법 생산에서 전구체 화학물질로 사용됩니다.

Catha edulis (Khat)

핫(Khat)은 아프리카의 뿔과 아라비아 반도가 원산지인 꽃이 피는 식물입니다.[156][157]

Khat은 "케토암페타민"인 cathinone이라고 불리는 모노아민 알칼로이드를 함유하고 있습니다. 이 알칼로이드는 흥분, 식욕 감퇴, 행복감을 유발한다고 합니다[by whom?]. 1980년, 세계보건기구(WHO)는 그것을 (담배나 술보다) 경미하거나 중간 정도의 심리적 의존성을 일으킬 수 있는 남용 약물로 분류했지만,[158] WHO는 캣을 심각한 중독성으로 간주하지 않습니다.[157] 미국, 캐나다, 독일과 같은 일부 국가에서는 금지되어 있고, 지부티, 에티오피아, 소말리아, 케냐, 예멘을 포함한 다른 국가에서는 생산, 판매 및 소비가 합법적입니다.[159]

모다피닐

모다피닐은 각성과 경계심을 촉진하는 우생 약물입니다. 모다피닐은 프로비길이라는 브랜드로 판매되고 있습니다. 모다피닐은 기면증, 교대근무 수면장애 또는 폐쇄성 수면무호흡증으로 인한 과도한 주간 졸림을 치료하는 데 사용됩니다. 라벨 외 사용이 인지 향상으로 알려져 있지만 이 사용에 대한 효과에 대한 연구는 결정적이지 않습니다.[160] 모다피닐은 중추신경계 자극제임에도 불구하고 중독 및 의존성 책임이 매우 낮은 것으로 간주됩니다.[161][162][163] 모다피닐은 생화학적 메커니즘을 흥분제 약물과 공유하지만 기분을 상승시키는 특성을 가질 가능성은 적습니다.[162] 카페인과의 효과의 유사성은 명확하게 확립되어 있지 않습니다.[164][165] 모다피닐은 다른 자극제와 달리 주관적인 즐거움이나 보상을 유도하지 않으며, 이는 일반적으로 행복감, 즉 격렬한 행복감과 관련이 있습니다. Euphoria는 약물 남용의 잠재적 지표로, 부작용에도 불구하고 물질을 강박적이고 과도하게 사용하는 것입니다. 임상시험에서 모다피닐은 남용 가능성이 없는 것으로 나타났기 때문에 중독 및 의존 위험이 낮은 것으로 간주되지만 주의가 필요합니다.[166][167]

피톨리산트

피톨리산트는 히스타민 3(H3) 자가수용체의 역작용제(antagonist)입니다. 이와 같이, 피톨리산트는 중추신경계 자극제 부류에 속하는 항히스타민제입니다.[168][169][170][171] 피톨리산트는 또한 각성과 경계심을 촉진한다는 의미로 우생학 계열의 약물로 여겨집니다. 피톨리산트는 오토3 수용체를 차단하여 작용하는 최초의 우생 약물입니다.[172][173][174]

Pitolisant는 투석을 받거나 하지 않는 기면증의 치료에 효과적이고 내약성이 있는 것으로 나타났습니다.[174][173][172]

피톨리산트는 미국에서 유일하게 조절되지 않는 항경련제입니다.[172] 연구에서 학대 위험을 최소화하는 것으로 나타났습니다.[172][175]

히스타민 3(H3) 자가수용체를 차단하면 뇌의 히스타민 뉴런의 활성이 증가합니다. H3 자동수용체는 내인성 히스타민에 결합할 때 히스타민 생합성 및 방출을 억제함으로써 중추신경계(그리고 덜하지만 말초신경계)에서 히스타민 활성을 조절합니다.[176] 피톨리산트는 H에서3 내인성 히스타민의 결합을 방지할 뿐만 아니라 수용체에서 내인성 히스타민과 반대의 반응을 생성함으로써 뇌의 히스타민 활성을 향상시킵니다([177]역작용).

레크리에이션 사용 및 남용 문제

자극제는 중추신경계와 말초신경계의 활동을 강화합니다. 일반적인 영향으로는 각성, 각성, 지구력, 생산성, 동기부여, 각성, 운동, 심박수, 혈압 증가, 음식과 수면에 대한 욕구 감소 등이 있습니다. 자극제를 사용하면 신체가 유사한 기능을 수행하는 천연 신체 화학 물질의 생산을 크게 줄일 수 있습니다. 신체가 정상적인 상태를 회복할 때까지, 일단 섭취된 자극제의 효과가 닳으면, 사용자는 우울하고, 무기력하고, 혼란스럽고, 비참함을 느낄 수 있습니다. 이를 "충돌"이라고 하며 자극제의 재사용을 유발할 수 있습니다.

중추신경계 자극제의 남용이 일반적입니다. 일부 중추신경계 자극제에 대한 중독은 빠르게 의학적, 정신적, 심리사회적 악화로 이어질 수 있습니다. 약물 내성, 의존성, 감작은 물론 금단증후군까지 발생할 수 있습니다.[178] 자극제는 비록 특이성은 낮지만 민감도가 높은 동물 감별 및 자가 투여 모델에서 스크리닝될 수 있습니다.[179] 진행성 비율 자가 투여 프로토콜에 대한 연구에 따르면 암페타민, 메틸페니데이트, 모다피닐, 코카인, 니코틴 모두 강화 효과를 나타내는 용량으로 측정되는 위약보다 더 높은 중단점을 가지고 있습니다.[180] 누진비 자가 투여 프로토콜은 동물이나 사람이 약물을 얻기 위해 어떤 행동(레버를 누르거나 코 장치를 찌르는 것과 같은)을 하도록 함으로써 약물을 얼마나 원하는지를 검사하는 방법입니다. 약을 얻기 위해 필요한 행동의 수가 매번 증가하기 때문에 약을 얻기가 점점 더 어려워집니다. 동물이나 사람이 약물을 얻기 위해 가장 많은 행동을 하는 것을 중단점이라고 합니다. 중단점이 높을수록 동물이나 인간이 더 많은 약을 원합니다. 암페타민과 같은 고전적인 흥분제와 대조적으로, 모다피닐의 효과는 동물이나 사람이 약물을 투여한 후 무엇을 해야 하는지에 달려 있습니다. 그들이 퍼즐을 풀거나 어떤 것을 기억하는 것과 같은 수행 과제를 해야 한다면, 모다피닐은 그들이 위약보다 그것을 위해 더 열심히 하도록 만들고, 피실험자들은 모다피닐을 자가 투여하기를 원했습니다. 그러나 만약 그들이 음악을 듣거나 비디오를 보는 것과 같은 휴식 과제를 해야 한다면, 피실험자들은 모다피닐을 자가 투여하기를 원하지 않았습니다. 이는 모다피닐이 다른 자극제와 달리 일반적으로 남용되거나 사람에게 의존하지 않는다는 점을 고려할 때 동물이나 사람이 무언가를 더 잘하거나 빠르게 할 수 있도록 도와줄 때 더 보람 있다는 것을 암시합니다.[180]

| 일반적인[158] 자극제의 의존성 전위 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 약물 | 의미하다 | 내 기쁨이지. | 심리적 의존성 | 물리적 의존성 |

| 코카인 | 2.39 | 3.0 | 2.8 | 1.3 |

| 담배 | 2.21 | 2.3 | 2.6 | 1.8 |

| 암페타민 | 1.67 | 2.0 | 1.9 | 1.1 |

| 엑스터시 | 1.13 | 1.5 | 1.2 | 0.7 |

오용처리

우연성 관리와 같은 심리 사회적 치료는 상담 및/또는 사례 관리로 구성된 평소와 같이 치료에 추가되었을 때 효과가 향상되었음을 입증했습니다. 이것은 중도탈락률의 감소와 금욕 기간의 연장으로 입증됩니다.[181]

테스트

신체 내 자극제의 존재는 다양한 절차로 테스트될 수 있습니다. 혈청과 소변은 간혹 타액을 사용하기도 하지만 검사 물질의 일반적인 공급원입니다. 일반적으로 사용되는 검사에는 크로마토그래피, 면역학적 분석 및 질량 분석이 포함됩니다.[182]

참고 항목

메모들

참고문헌

- ^ "stimulant – definition of stimulant in English Oxford Dictionaries". Oxford Dictionaries English. Archived from the original on 26 February 2017.

- ^ a b Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (1999). Chapter 2—How Stimulants Affect the Brain and Behavior. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US). Archived from the original on 19 February 2017.

- ^ Costa VM, Grando LG, Milandri E, Nardi J, Teixeira P, Mladěnka P, Remião F, et al. (OEMONOM) (November 2022). "Natural Sympathomimetic Drugs: From Pharmacology to Toxicology". Biomolecules. 12 (12): 1793. doi:10.3390/biom12121793. PMC 9775352. PMID 36551221.

- ^ a b c Rozenek EB, Górska M, Wilczyńska K, Waszkiewicz N (September 2019). "In search of optimal psychoactivation: stimulants as cognitive performance enhancers". Arh Hig Rada Toksikol. 70 (3): 150–159. doi:10.2478/aiht-2019-70-3298. PMID 32597132.

- ^ "Definition of ERGOGENIC". www.merriam-webster.com.

- ^ Avois L, Robinson N, Saudan C, Baume N, Mangin P, Saugy M (7 January 2017). "Central nervous system stimulants and sport practice". British Journal of Sports Medicine. 40 (Suppl 1): i16–i20. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2006.027557. ISSN 0306-3674. PMC 2657493. PMID 16799095.

- ^ a b c Bagot KS, Kaminer Y (1 April 2014). "Efficacy of stimulants for cognitive enhancement in non-attention deficit hyperactivity disorder youth: a systematic review". Addiction. 109 (4): 547–557. doi:10.1111/add.12460. ISSN 1360-0443. PMC 4471173. PMID 24749160.

- ^ Zamanian MY, Karimvandi MN, Nikbakhtzadeh M, Zahedi E, Bokov DO, Kujawska M, et al. (2023). "Effects of Modafinil (Provigil) on Memory and Learning in Experimental and Clinical Studies: From Molecular Mechanisms to Behaviour Molecular Mechanisms and Behavioural Effects". Current Molecular Pharmacology. 16 (4): 507–516. doi:10.2174/1874467215666220901122824. PMID 36056861. S2CID 252046371.

- ^ Hashemian SM, Farhadi T (2020). "A review on modafinil: the characteristics, function, and use in critical care". Journal of Drug Assessment. 9 (1): 82–86. doi:10.1080/21556660.2020.1745209. PMC 7170336. PMID 32341841.

- ^ Meulen R, Hall W, Mohammed A (2017). Rethinking Cognitive Enhancement. Oxford University Press. p. 116. ISBN 978-0-19-872739-2.

- ^ Morton WA, Stockton GG (8 January 2017). "Methylphenidate Abuse and Psychiatric Side Effects". Primary Care Companion to the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2 (5): 159–164. doi:10.4088/PCC.v02n0502. ISSN 1523-5998. PMC 181133. PMID 15014637.

- ^ "Chapter 5—Medical Aspects of Stimulant Use Disorders". Treatment for Stimulant Use Disorders.Chapter 5—Medical Aspects of Stimulant Use Disorders. Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. Treatment for Stimulant Use Disorders. Rockville (MD): Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US). 1999. Archived from the original on 19 February 2017.

- ^ Westover AN, Halm EA (9 June 2012). "Do prescription stimulants increase the risk of adverse cardiovascular events?: A systematic review". BMC Cardiovascular Disorders. 12 (1): 41. doi:10.1186/1471-2261-12-41. ISSN 1471-2261. PMC 3405448. PMID 22682429.

- ^ Fredriksen M, Halmøy A, Faraone SV, Haavik J (1 June 2013). "Long-term efficacy and safety of treatment with stimulants and atomoxetine in adult ADHD: a review of controlled and naturalistic studies". European Neuropsychopharmacology. 23 (6): 508–527. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2012.07.016. hdl:10852/40257. ISSN 1873-7862. PMID 22917983. S2CID 20400392.

- ^ Hammerness PG, Karampahtsis C, Babalola R, Alexander ME (1 April 2015). "Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder treatment: what are the long-term cardiovascular risks?". Expert Opinion on Drug Safety. 14 (4): 543–551. doi:10.1517/14740338.2015.1011620. ISSN 1744-764X. PMID 25648243. S2CID 39425997.

- ^ Hechtman L, Greenfield B (1 January 2003). "Long-term use of stimulants in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: safety, efficacy, and long-term outcome". Paediatric Drugs. 5 (12): 787–794. doi:10.2165/00148581-200305120-00002. ISSN 1174-5878. PMID 14658920. S2CID 68191253.

- ^ Sordo L, Indave BI, Barrio G, Degenhardt L, de la Fuente L, Bravo MJ (1 September 2014). "Cocaine use and risk of stroke: a systematic review". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 142: 1–13. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.06.041. PMID 25066468.

- ^ COUGHLIN P, MAVOR, A (1 October 2006). "Arterial Consequences of Recreational Drug Use". European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery. 32 (4): 389–396. doi:10.1016/j.ejvs.2006.03.003. PMID 16682239.

- ^ Tashkin DP (1 March 2001). "Airway effects of marijuana, cocaine, and other inhaled illicit agents". Current Opinion in Pulmonary Medicine. 7 (2): 43–61. doi:10.1097/00063198-200103000-00001. ISSN 1070-5287. PMID 11224724. S2CID 23421796.

- ^ Trozak D, Gould W (1984). "Cocaine abuse and connective tissue disease". J Am Acad Dermatol. 10 (3): 525. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(84)80112-7. PMID 6725666.

- ^ Ramón Peces, Navascués RA, Baltar J, Seco M, Alvarez J (1999). "Antiglomerular Basement Membrane Antibody-Mediated Glomerulonephritis after Intranasal Cocaine Use". Nephron. 81 (4): 434–438. doi:10.1159/000045328. PMID 10095180. S2CID 26921706.

- ^ Moore PM, Richardson B (1998). "Neurology of the vasculitides and connective tissue diseases". J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 65 (1): 10–22. doi:10.1136/jnnp.65.1.10. PMC 2170162. PMID 9667555.

- ^ Carvalho M, Carmo H, Costa VM, Capela JP, Pontes H, Remião F, Carvalho F, Bastos Mde L (August 2012). "Toxicity of amphetamines: an update". Arch. Toxicol. 86 (8): 1167–1231. doi:10.1007/s00204-012-0815-5. PMID 22392347. S2CID 2873101.

- ^ Thrash B, Thiruchelvan K, Ahuja M, Suppiramaniam V, Dhanasekaran M (2009). "Methamphetamine-induced neurotoxicity: the road to Parkinson's disease" (PDF). Pharmacol Rep. 61 (6): 966–977. doi:10.1016/s1734-1140(09)70158-6. PMID 20081231. S2CID 4729728. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 July 2011.

- ^ Sulzer D, Zecca L (February 2000). "Intraneuronal dopamine-quinone synthesis: a review". Neurotox. Res. 1 (3): 181–195. doi:10.1007/BF03033289. PMID 12835101. S2CID 21892355.

- ^ Miyazaki I, Asanuma M (June 2008). "Dopaminergic neuron-specific oxidative stress caused by dopamine itself". Acta Med. Okayama. 62 (3): 141–150. doi:10.18926/AMO/30942. PMID 18596830.

- ^ "Top 100 Drugs for Q4 2013 by Sales – U.S. Pharmaceutical Statistics". www.drugs.com. Archived from the original on 14 August 2013.

- ^ "World Drug Report 2015" (PDF). p. 149. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 February 2016.

- ^ Harper SJ, Jones NS (1 October 2006). "Cocaine: what role does it have in current ENT practice? A review of the current literature". The Journal of Laryngology and Otology. 120 (10): 808–811. doi:10.1017/S0022215106001459. ISSN 1748-5460. PMID 16848922. S2CID 28169472.

- ^ Kaplan LM (1 March 2005). "Pharmacological therapies for obesity". Gastroenterology Clinics of North America. 34 (1): 91–104. doi:10.1016/j.gtc.2004.12.002. ISSN 0889-8553. PMID 15823441.

- ^ Palamara KL, Mogul HR, Peterson SJ, Frishman WH (1 October 2016). "Obesity: new perspectives and pharmacotherapies". Cardiology in Review. 14 (5): 238–258. doi:10.1097/01.crd.0000233903.57946.fd. ISSN 1538-4683. PMID 16924165.

- ^ "The Voice of the Patient A series of reports from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration's (FDA's) Patient-Focused Drug Development Initiative" (PDF). Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 May 2017.

- ^ Heal DJ, Smith SL, Gosden J, Nutt DJ (7 January 2017). "Amphetamine, past and present – a pharmacological and clinical perspective". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 27 (6): 479–496. doi:10.1177/0269881113482532. ISSN 0269-8811. PMC 3666194. PMID 23539642.

- ^ Research Cf (26 June 2019). "Drug Safety and Availability - FDA Drug Safety Communication: Safety Review Update of Medications used to treat Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in adults". www.fda.gov. Archived from the original on 30 October 2013.

- ^ Stotz G, Woggon B, Angst J (1 December 1999). "Psychostimulants in the therapy of treatment-resistant depression Review of the literature and findings from a retrospective study in 65 depressed patients". Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 1 (3): 165–174. doi:10.31887/DCNS.1999.1.3/gstotz. ISSN 1294-8322. PMC 3181580. PMID 22034135.

- ^ Doig RL (February 1905). "Epinephrin; especially in asthma". California State Journal of Medicine. 3 (2): 54–5. PMC 1650334. PMID 18733372.

- ^ Chu EK, Drazen JM (1 June 2005). "Asthma". American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 171 (11): 1202–1208. doi:10.1164/rccm.200502-257OE. ISSN 1073-449X. PMID 15778490.

- ^ 비코풀로스 D 편집장. AusDI: 의료 전문가를 위한 약물 정보, 2판. Castle Hill: 의약품 관리 정보 서비스; 2002.

- ^ "Pseudoephedrine (By mouth) – National Library of Medicine". PubMed Health. Archived from the original on 14 February 2014.

- ^ a b Moncrieff J (June 2008). "The creation of the concept of an antidepressant: an historical analysis". Soc Sci Med. 66 (11): 2346–55. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.01.047. PMID 18321627.

- ^ a b c d J. Moncrieff (13 April 2016). The Myth of the Chemical Cure: A Critique of Psychiatric Drug Treatment. Springer. pp. 121–. ISBN 978-0-230-58944-5. OCLC 1047624331.

A well-known textbook of physical treatments described stimulants as having 'limited value in depression' because the euphoria they induce quickly wears off and 'the patient slips back' (Sargant & Slater 1944).

- ^ Morelli M, Tognotti E (August 2021). "Brief history of the medical and non-medical use of amphetamine-like psychostimulants". Exp Neurol. 342: 113754. doi:10.1016/j.expneurol.2021.113754. PMID 34000249. S2CID 234768496.

- ^ a b Malhi GS, Byrow Y, Bassett D, Boyce P, Hopwood M, Lyndon W, Mulder R, Porter R, Singh A, Murray G (March 2016). "Stimulants for depression: On the up and up?". Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 50 (3): 203–7. doi:10.1177/0004867416634208. PMID 26906078. S2CID 45341424.

- ^ a b c Orr K, Taylor D (2007). "Psychostimulants in the treatment of depression: a review of the evidence". CNS Drugs. 21 (3): 239–57. doi:10.2165/00023210-200721030-00004. PMID 17338594. S2CID 35761979.

- ^ a b c Pallikaras V, Shizgal P (August 2022). "Dopamine and Beyond: Implications of Psychophysical Studies of Intracranial Self-Stimulation for the Treatment of Depression". Brain Sci. 12 (8): 1052. doi:10.3390/brainsci12081052. PMC 9406029. PMID 36009115.

- ^ a b c Pallikaras V, Shizgal P (2022). "The Convergence Model of Brain Reward Circuitry: Implications for Relief of Treatment-Resistant Depression by Deep-Brain Stimulation of the Medial Forebrain Bundle". Front Behav Neurosci. 16: 851067. doi:10.3389/fnbeh.2022.851067. PMC 9011331. PMID 35431828.

- ^ Giacobbe P, Rakita U, Lam R, Milev R, Kennedy SH, McIntyre RS (January 2018). "Efficacy and tolerability of lisdexamfetamine as an antidepressant augmentation strategy: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". J Affect Disord. 226: 294–300. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2017.09.041. PMID 29028590.

- ^ McIntyre RS, Lee Y, Zhou AJ, Rosenblat JD, Peters EM, Lam RW, Kennedy SH, Rong C, Jerrell JM (August 2017). "The Efficacy of Psychostimulants in Major Depressive Episodes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". J Clin Psychopharmacol. 37 (4): 412–418. doi:10.1097/JCP.0000000000000723. PMID 28590365. S2CID 27622964.

- ^ Bahji A, Mesbah-Oskui L (September 2021). "Comparative efficacy and safety of stimulant-type medications for depression: A systematic review and network meta-analysis". J Affect Disord. 292: 416–423. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2021.05.119. PMID 34144366.

- ^ Nuñez NA, Joseph B, Pahwa M, Kumar R, Resendez MG, Prokop LJ, Veldic M, Seshadri A, Biernacka JM, Frye MA, Wang Z, Singh B (April 2022). "Augmentation strategies for treatment resistant major depression: A systematic review and network meta-analysis". J Affect Disord. 302: 385–400. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2021.12.134. PMC 9328668. PMID 34986373.

- ^ a b c Barr AM, Markou A (2005). "Psychostimulant withdrawal as an inducing condition in animal models of depression". Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 29 (4–5): 675–706. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.03.012. PMID 15893821. S2CID 23653608.

- ^ Folgering JH, Choi M, Schlumbohm C, van Gaalen MM, Stratford RE (April 2019). "Development of a non-human primate model to support CNS translational research: Demonstration with D-amphetamine exposure and dopamine response". J Neurosci Methods. 317: 71–81. doi:10.1016/j.jneumeth.2019.02.005. PMID 30768951. S2CID 72333922.

- ^ van Gaalen MM, Schlumbohm C, Folgering JH, Adhikari S, Bhattacharya C, Steinbach D, Stratford RE (April 2019). "Development of a Semimechanistic Pharmacokinetic-Pharmacodynamic Model Describing Dextroamphetamine Exposure and Striatal Dopamine Response in Rats and Nonhuman Primates following a Single Dose of Dextroamphetamine". J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 369 (1): 107–120. doi:10.1124/jpet.118.254508. PMID 30733244. S2CID 73441294.

- ^ van Gaalen MM, Schlumbohm C, Folgering JH, Adhikari S, Bhattacharya C, Steinbach D, Stratford RE (7 February 2019). "Development of a Semimechanistic Pharmacokinetic-Pharmacodynamic Model Describing Dextroamphetamine Exposure and Striatal Dopamine Response in Rats and Nonhuman Primates following a Single Dose of Dextroamphetamine". Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. American Society for Pharmacology & Experimental Therapeutics (ASPET). 369 (1): 107–120. doi:10.1124/jpet.118.254508. ISSN 0022-3565. PMID 30733244. S2CID 73441294.

- ^ Ermer JC, Pennick M, Frick G (May 2016). "Lisdexamfetamine Dimesylate: Prodrug Delivery, Amphetamine Exposure and Duration of Efficacy". Clin Drug Investig. 36 (5): 341–56. doi:10.1007/s40261-015-0354-y. PMC 4823324. PMID 27021968.

- ^ a b c Dolder PC, Strajhar P, Vizeli P, Hammann F, Odermatt A, Liechti ME (2017). "Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Lisdexamfetamine Compared with D-Amphetamine in Healthy Subjects". Front Pharmacol. 8: 617. doi:10.3389/fphar.2017.00617. PMC 5594082. PMID 28936175.

- ^ Brauer LH, Ambre J, De Wit H (February 1996). "Acute tolerance to subjective but not cardiovascular effects of d-amphetamine in normal, healthy men". J Clin Psychopharmacol. 16 (1): 72–6. doi:10.1097/00004714-199602000-00012. PMID 8834422.

- ^ Comer SD, Hart CL, Ward AS, Haney M, Foltin RW, Fischman MW (June 2001). "Effects of repeated oral methamphetamine administration in humans". Psychopharmacology (Berl). 155 (4): 397–404. doi:10.1007/s002130100727. PMID 11441429. S2CID 19103494.

- ^ Barr AM, Markou A, Phillips AG (October 2002). "A 'crash' course on psychostimulant withdrawal as a model of depression". Trends Pharmacol Sci. 23 (10): 475–82. doi:10.1016/s0165-6147(02)02086-2. PMID 12368072.

- ^ D'Souza MS, Markou A (2010). "Neural substrates of psychostimulant withdrawal-induced anhedonia". Curr Top Behav Neurosci. Current Topics in Behavioral Neurosciences. Berlin, Heidelberg. 3: 119–78. doi:10.1007/7854_2009_20. ISBN 978-3-642-03000-0. PMID 21161752.

- ^ Baicy K, Bearden CE, Monterosso J, Brody AL, Isaacson AJ, London ED (2005). "Common substrates of dysphoria in stimulant drug abuse and primary depression: therapeutic targets". Int Rev Neurobiol. International Review of Neurobiology. 65: 117–45. doi:10.1016/S0074-7742(04)65005-7. ISBN 978-0-12-366866-0. PMID 16140055.

- ^ Gallardo-Godoy A, Fierro A, McLean TH, Castillo M, Cassels BK, Reyes-Parada M, Nichols DE (April 2005). "Sulfur-substituted alpha-alkyl phenethylamines as selective and reversible MAO-A inhibitors: biological activities, CoMFA analysis, and active site modeling". J Med Chem. 48 (7): 2407–19. doi:10.1021/jm0493109. PMID 15801832.

- ^ Fitzgerald LR, Gannon BM, Walther D, Landavazo A, Hiranita T, Blough BE, Baumann MH, Fantegrossi WE (March 2024). "Structure-activity relationships for locomotor stimulant effects and monoamine transporter interactions of substituted amphetamines and cathinones". Neuropharmacology. 245: 109827. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2023.109827. PMID 38154512. S2CID 266558677.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Hagel JM, Krizevski R, Marsolais F, Lewinsohn E, Facchini PJ (2012). "Biosynthesis of amphetamine analogs in plants". Trends Plant Sci. 17 (7): 404–412. doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2012.03.004. PMID 22502775.

Substituted amphetamines, which are also called phenylpropylamino alkaloids, are a diverse group of nitrogen-containing compounds that feature a phenethylamine backbone with a methyl group at the α-position relative to the nitrogen (Figure 1). Countless variation in functional group substitutions has yielded a collection of synthetic drugs with diverse pharmacological properties as stimulants, empathogens and hallucinogens [3]. ... Beyond (1R,2S)-ephedrine and (1S,2S)-pseudoephedrine, myriad other substituted amphetamines have important pharmaceutical applications. The stereochemistry at the α-carbon is often a key determinant of pharmacological activity, with (S)-enantiomers being more potent. For example, (S)-amphetamine, commonly known as d-amphetamine or dextroamphetamine, displays five times greater psychostimulant activity compared with its (R)-isomer [78]. Most such molecules are produced exclusively through chemical syntheses and many are prescribed widely in modern medicine. For example, (S)-amphetamine (Figure 4b), a key ingredient in Adderall and Dexedrine, is used to treat attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) [79]. ...

[Figure 4](b) Examples of synthetic, pharmaceutically important substituted amphetamines. - ^ a b Glennon RA (2013). "Phenylisopropylamine stimulants: amphetamine-related agents". In Lemke TL, Williams DA, Roche VF, Zito W (eds.). Foye's principles of medicinal chemistry (7th ed.). Philadelphia, USA: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 646–648. ISBN 978-1-60913-345-0.

The simplest unsubstituted phenylisopropylamine, 1-phenyl-2-aminopropane, or amphetamine, serves as a common structural template for hallucinogens and psychostimulants. Amphetamine produces central stimulant, anorectic, and sympathomimetic actions, and it is the prototype member of this class (39).

- ^ Lillsunde P, Korte T (March 1991). "Determination of ring- and N-substituted amphetamines as heptafluorobutyryl derivatives". Forensic Sci. Int. 49 (2): 205–213. doi:10.1016/0379-0738(91)90081-s. PMID 1855720.

- ^ a b c Miller GM (January 2011). "The emerging role of trace amine-associated receptor 1 in the functional regulation of monoamine transporters and dopaminergic activity". J. Neurochem. 116 (2): 164–176. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.07109.x. PMC 3005101. PMID 21073468.

- ^ Eiden LE, Weihe E (January 2011). "VMAT2: a dynamic regulator of brain monoaminergic neuronal function interacting with drugs of abuse". Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1216 (1): 86–98. Bibcode:2011NYASA1216...86E. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05906.x. PMC 4183197. PMID 21272013.

- ^ Dale E, Bang-Andersen B, Sánchez C (2015). "Emerging mechanisms and treatments for depression beyond SSRIs and SNRIs". Biochemical Pharmacology. 95 (2): 81–97. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2015.03.011. ISSN 0006-2952. PMID 25813654.

- ^ 처방약 남용을 예방하고 치료하기 위한 국립 약물 남용 연구소의 노력, 2007년 9월 29일 웨이백 기계에서 보관, 미국 하원 형사사법, 약물정책 및 정부개혁 인적자원위원회 소위원회 앞 증언, 2006년 7월 26일

- ^ Docherty JR (7 January 2017). "Pharmacology of stimulants prohibited by the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA)". British Journal of Pharmacology. 154 (3): 606–622. doi:10.1038/bjp.2008.124. ISSN 0007-1188. PMC 2439527. PMID 18500382.

- ^ Caffeine for the Sustainment of Mental Task Performance: Formulations for Military Operations. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US). 2001. Archived from the original on 9 October 2017.

- ^ "Modafinil Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 24 June 2018.

- ^ Thorpy MJ, Bogan RK (April 2020). "Update on the pharmacologic management of narcolepsy: mechanisms of action and clinical implications". Sleep Medicine. 68: 97–109. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2019.09.001. PMID 32032921. S2CID 203405397.

- ^ Stahl SM (March 2017). "Modafinil". Prescriber's Guide: Stahl's Essential Psychopharmacology (6th ed.). Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. pp. 491–495. ISBN 978-1-108-22874-9.

- ^ Gerrard P, Malcolm R (June 2007). "Mechanisms of modafinil: A review of current research". Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment. 3 (3): 349–364. PMC 2654794. PMID 19300566.

- ^ Lazarus M, Chen JF, Huang ZL, Urade Y, Fredholm BB (2019). "Adenosine and Sleep". Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. 253: 359–381. doi:10.1007/164_2017_36. ISBN 978-3-030-11270-7. PMID 28646346.

- ^ a b c "Adderall XR Prescribing Information" (PDF). United States Food and Drug Administration. June 2013. p. 11. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 7 January 2014.

- ^ a b Liddle DG, Connor DJ (June 2013). "Nutritional supplements and ergogenic AIDS". Prim. Care. 40 (2): 487–505. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2013.02.009. PMID 23668655.

Amphetamines and caffeine are stimulants that increase alertness, improve focus, decrease reaction time, and delay fatigue, allowing for an increased intensity and duration of training...

Physiologic and performance effects

• Amphetamines increase dopamine/norepinephrine release and inhibit their reuptake, leading to central nervous system (CNS) stimulation

• Amphetamines seem to enhance athletic performance in anaerobic conditions 39 40

• Improved reaction time

• Increased muscle strength and delayed muscle fatigue

• Increased acceleration

• Increased alertness and attention to task - ^ a b c Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). "Chapter 13: Higher Cognitive Function and Behavioral Control". In Sydor A, Brown RY (eds.). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. p. 318. ISBN 978-0-07-148127-4.

Therapeutic (relatively low) doses of psychostimulants, such as methylphenidate and amphetamine, improve performance on working memory tasks both in individuals with ADHD and in normal subjects...it is now believed that dopamine and norepinephrine, but not serotonin, produce the beneficial effects of stimulants on working memory. At abused (relatively high) doses, stimulants can interfere with working memory and cognitive control, as will be discussed below. It is important to recognize, however, that stimulants act not only on working memory function, but also on general levels of arousal and, within the nucleus accumbens, improve the saliency of tasks. Thus, stimulants improve performance on effortful but tedious tasks...through indirect stimulation of dopamine and norepinephrine receptors.

- ^ a b Montgomery KA (June 2008). "Sexual desire disorders". Psychiatry. 5 (6): 50–55. PMC 2695750. PMID 19727285.

- ^ Wilens TE, Adler LA, Adams J, Sgambati S, Rotrosen J, Sawtelle R, Utzinger L, Fusillo S (January 2008). "Misuse and diversion of stimulants prescribed for ADHD: a systematic review of the literature". J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 47 (1): 21–31. doi:10.1097/chi.0b013e31815a56f1. PMID 18174822.

Stimulant misuse appears to occur both for performance enhancement and their euphorogenic effects, the latter being related to the intrinsic properties of the stimulants (e.g., IR versus ER profile)...

Although useful in the treatment of ADHD, stimulants are controlled II substances with a history of preclinical and human studies showing potential abuse liability. - ^ "Convention on psychotropic substances". United Nations Treaty Collection. United Nations. Archived from the original on 31 March 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2014.

- ^ "Methamphetamine facts". DrugPolicy.org. Archived from the original on 17 April 2018. Retrieved 7 January 2014.

- ^ a b Chawla S, Le Pichon T (2006). "World Drug Report 2006" (PDF). United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. pp. 128–135. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 May 2013. Retrieved 7 January 2014.

- ^ a b Heal DJ, Smith SL, Gosden J, Nutt DJ (June 2013). "Amphetamine, past and present – a pharmacological and clinical perspective". J. Psychopharmacol. 27 (6): 479–496. doi:10.1177/0269881113482532. PMC 3666194. PMID 23539642.

- ^ Rasmussen N (July 2006). "Making the first anti-depressant: amphetamine in American medicine, 1929–1950". J. Hist. Med. Allied Sci. 61 (3): 288–323. doi:10.1093/jhmas/jrj039. PMID 16492800. S2CID 24974454.

- ^ "Adderall IR Prescribing Information" (PDF). United States Food and Drug Administration. March 2007. p. 5. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 September 2013. Retrieved 2 November 2013.

- ^ "Adderall XR Prescribing Information" (PDF). United States Food and Drug Administration. June 2013. pp. 4–8. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 7 October 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f Westfall DP, Westfall TC (2010). "Miscellaneous Sympathomimetic Agonists". In Brunton LL, Chabner BA, Knollmann BC (eds.). Goodman & Gilman's Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics (12th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-162442-8.

- ^ a b Shoptaw SJ, Kao U, Ling W (2009). "Treatment for amphetamine psychosis (Review)". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2009 (1): CD003026. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003026.pub3. PMC 7004251. PMID 19160215.

- ^ Greydanus D. "Stimulant Misuse: Strategies to Manage a Growing Problem" (PDF). American College Health Association (Review Article). ACHA Professional Development Program. p. 20. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 November 2013. Retrieved 2 November 2013.

- ^ Lovett R (24 September 2005). "Coffee: The demon drink?". New Scientist (2518). Archived from the original on 24 October 2007. Retrieved 3 August 2009. (구독 필수)

- ^ Commissioner Oo (24 March 2020). "FDA warns companies to stop selling dangerous and illegal pure and highly concentrated caffeine products". FDA.

- ^ a b https://www.tga.gov.au/resources/publication/scheduling-decisions-interim/interim-decisions-and-invitation-further-comment-substances-referred-november-2019-acmsaccs-meetings/31-interim-decision-relation-caffeine

- ^ https://www.health.gov.au/ministers/senator-the-hon-richard-colbeck/media/australia-to-protect-consumers-by-banning-sale-of-pure-caffeine-powder

- ^ Lipton RB, Diener HC, Robbins MS, Garas SY, Patel K (October 2017). "Caffeine in the management of patients with headache". J Headache Pain. 18 (1): 107. doi:10.1186/s10194-017-0806-2. PMC 5655397. PMID 29067618.

- ^ Bolton S, Null G (1981). "Caffeine: Psychological Effects, Use and Abuse" (PDF). Orthomolecular Psychiatry. 10 (3): 202–211.

- ^ Cappelletti S, Piacentino D, Fineschi V, Frati P, Cipolloni L, Aromatario M (May 2018). "Caffeine-Related Deaths: Manner of Deaths and Categories at Risk". Nutrients. 10 (5): 611. doi:10.3390/nu10050611. PMC 5986491. PMID 29757951.

- ^ Nehlig A, Daval JL, Debry G (1 August 2016). "Caffeine and the central nervous system: mechanisms of action, biochemical, metabolic and psychostimulant effects". Brain Research. Brain Research Reviews. 17 (2): 139–170. doi:10.1016/0165-0173(92)90012-b. PMID 1356551. S2CID 14277779.

- ^ Bjorness TE, Greene RW (8 January 2017). "Adenosine and Sleep". Current Neuropharmacology. 7 (3): 238–245. doi:10.2174/157015909789152182. ISSN 1570-159X. PMC 2769007. PMID 20190965.

- ^ Solinas M, Ferré S, You Z, Karcz-Kubicha M, Popoli P, Goldberg SR (1 August 2002). "Caffeine Induces Dopamine and Glutamate Release in the Shell of the Nucleus Accumbens". Journal of Neuroscience. 22 (15): 6321–6324. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-15-06321.2002. ISSN 0270-6474. PMC 6758129. PMID 12151508.

- ^ Kamiya T, Saitoh O, Yoshioka K, Nakata H (June 2003). "Oligomerization of adenosine A2A and dopamine D2 receptors in living cells". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 306 (2): 544–9. doi:10.1016/S0006-291X(03)00991-4. PMID 12804599.

- ^ Fishchman N, Mello N. Testing for Abuse Liability of Drugs in Humans (PDF). Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Public Health Service Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration National Institute on Drug Abuse. p. 179. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 December 2016.

- ^ Temple JL (2009). "Caffeine use in children: what we know, what we have left to learn, and why we should worry". Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 33 (6): 793–806. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.01.001. PMC 2699625. PMID 19428492.

- ^ Nkondjock A (May 2009). "Coffee consumption and the risk of cancer: an overview". Cancer Lett. 277 (2): 121–5. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2008.08.022. PMID 18834663.

- ^ a b Arab L (2010). "Epidemiologic evidence on coffee and cancer". Nutrition and Cancer. 62 (3): 271–83. doi:10.1080/01635580903407122. PMID 20358464. S2CID 44949233.

- ^ Santos C, Costa J, Santos J, Vaz-Carneiro A, Lunet N (2010). "Caffeine intake and dementia: systematic review and meta-analysis". J. Alzheimers Dis. 20 (Suppl 1): S187–204. doi:10.3233/JAD-2010-091387. PMID 20182026.

- ^ Marques S, Batalha VL, Lopes LV, Outeiro TF (2011). "Modulating Alzheimer's disease through caffeine: a putative link to epigenetics". J. Alzheimers Dis. 24 (2): 161–71. doi:10.3233/JAD-2011-110032. PMID 21427489.

- ^ Arendash GW, Cao C (2010). "Caffeine and coffee as therapeutics against Alzheimer's disease". J. Alzheimers Dis. 20 (Suppl 1): S117–26. doi:10.3233/JAD-2010-091249. PMID 20182037.

- ^ Ding M, Bhupathiraju SN, Satija A, van Dam RM, Hu FB (11 February 2014). "Long-term coffee consumption and risk of cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and a dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies". Circulation. 129 (6): 643–59. doi:10.1161/circulationaha.113.005925. PMC 3945962. PMID 24201300.

- ^ van Dam RM (2008). "Coffee consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and cancer". Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism. 33 (6): 1269–1283. doi:10.1139/H08-120. PMID 19088789.

- ^ Zhang Z, Hu G, Caballero B, Appel L, Chen L (June 2011). "Habitual coffee consumption and risk of hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective observational studies". Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 93 (6): 1212–9. doi:10.3945/ajcn.110.004044. PMID 21450934.

- ^ Li M, Wang M, Guo W, Wang J, Sun X (March 2011). "The effect of caffeine on intraocular pressure: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 249 (3): 435–42. doi:10.1007/s00417-010-1455-1. PMID 20706731. S2CID 668498.

- ^ Muriel P, Arauz J (2010). "Coffee and liver diseases". Fitoterapia. 81 (5): 297–305. doi:10.1016/j.fitote.2009.10.003. PMID 19825397.

- ^ O'Connor A (2007). Never shower in a thunderstorm: surprising facts and misleading myths about our health and the world we live in (1st ed.). New York: Times Books. p. 144. ISBN 978-0-8050-8312-5. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- ^ Gilmore B, Michael M (February 2011). "Treatment of acute migraine headache". Am Fam Physician. 83 (3): 271–80. PMID 21302868.

- ^ Hackett PH (2010). "Caffeine at high altitude: java at base Camp". High Alt. Med. Biol. 11 (1): 13–7. doi:10.1089/ham.2009.1077. PMID 20367483. S2CID 8820874.

- ^ Merck Manual EPHEDrine 2011년 3월 24일 Wayback Machine에서 아카이브됨 2010년 1월 최종 전체 검토/수정

- ^ Meyer JS (21 November 2013). "3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA): current perspectives". Substance Abuse and Rehabilitation. 4: 83–99. doi:10.2147/SAR.S37258. ISSN 1179-8467. PMC 3931692. PMID 24648791.

- ^ Nutt D, King LA, Saulsbury W, Blakemore C (24 March 2007). "Development of a rational scale to assess the harm of drugs of potential misuse". Lancet. 369 (9566): 1047–1053. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60464-4. ISSN 1474-547X. PMID 17382831. S2CID 5903121.

- ^ Hope C, ed. (7 February 2009). "Ecstasy 'no more dangerous than horse riding'". Telegraph.co.uk. Archived from the original on 10 December 2015. Retrieved 4 December 2015.

- ^ Simmler LD, Buser TA, Donzelli M, Schramm Y, Dieu L, Huwyler J, Chaboz S, Hoener MC, Liechti ME (2012). "Pharmacological characterization of designer cathinones in vitro". British Journal of Pharmacology. 168 (2): 458–470. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.02145.x. ISSN 0007-1188. PMC 3572571. PMID 22897747.

- ^ 미국 특허 3478050 – 1-(3,4-메틸렌디옥시-페닐)-2-피롤리디노-알카논

- ^ "Abuse Of Fake 'Bath Salts' Sends Dozens To ER". KMBC.com. 23 December 2010. Archived from the original on 13 July 2011.

- ^ "MDPV Bath Salts Drug Over The Counter". Archived from the original on 10 March 2011.

- ^ Samantha Morgan (9 November 2010). "Parents cautioned against over the counter synthetic speed". NBC 33 News. Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 16 May 2011.

- ^ Kelsey Scram (6 January 2011). "Bath Salts Used to Get High". NBC 33 News. Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 16 May 2011.

- ^ Cumming E (22 April 2010). "Mephedrone: Chemistry lessons". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 7 January 2014. Retrieved 14 September 2010.

- ^ "Drugs crackdown hailed a success". BBC News. 8 March 2010. Archived from the original on 26 August 2012. Retrieved 31 March 2010.

- ^ a b c Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). "15". In Sydor A, Brown RY (eds.). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. p. 370. ISBN 978-0-07-148127-4.

Unlike cocaine and amphetamine, methamphetamine is directly toxic to midbrain dopamine neurons.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Desoxyn Prescribing Information" (PDF). United States Food and Drug Administration. December 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 January 2014. Retrieved 6 January 2014.

- ^ a b c d Krasnova IN, Cadet JL (May 2009). "Methamphetamine toxicity and messengers of death". Brain Res. Rev. 60 (2): 379–407. doi:10.1016/j.brainresrev.2009.03.002. PMC 2731235. PMID 19328213.

Neuroimaging studies have revealed that METH can indeed cause neurodegenerative changes in the brains of human addicts (Aron and Paulus, 2007; Chang et al., 2007). These abnormalities include persistent decreases in the levels of dopamine transporters (DAT) in the orbitofrontal cortex, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, and the caudate-putamen (McCann et al., 1998, 2008; Sekine et al., 2003; Volkow et al., 2001a, 2001c). The density of serotonin transporters (5-HTT) is also decreased in the midbrain, caudate, putamen, hypothalamus, thalamus, the orbitofrontal, temporal, and cingulate cortices of METH-dependent individuals (Sekine et al., 2006) ...

Neuropsychological studies have detected deficits in attention, working memory, and decision-making in chronic METH addicts ...

There is compelling evidence that the negative neuropsychiatric consequences of METH abuse are due, at least in part, to drug-induced neuropathological changes in the brains of these METH-exposed individuals ...

Structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies in METH addicts have revealed substantial morphological changes in their brains. These include loss of gray matter in the cingulate, limbic, and paralimbic cortices, significant shrinkage of hippocampi, and hypertrophy of white matter (Thompson et al., 2004). In addition, the brains of METH abusers show evidence of hyperintensities in white matter (Bae et al., 2006; Ernst et al., 2000), decreases in the neuronal marker, N-acetylaspartate (Ernst et al., 2000; Sung et al., 2007), reductions in a marker of metabolic integrity, creatine (Sekine et al., 2002) and increases in a marker of glial activation, myoinositol (Chang et al., 2002; Ernst et al., 2000; Sung et al., 2007; Yen et al., 1994). Elevated choline levels, which are indicative of increased cellular membrane synthesis and turnover are also evident in the frontal gray matter of METH abusers (Ernst et al., 2000; Salo et al., 2007; Taylor et al., 2007). - ^ a b Kuczenski R, Segal DS, Cho AK, Melega W (February 1995). "Hippocampus norepinephrine, caudate dopamine and serotonin, and behavioral responses to the stereoisomers of amphetamine and methamphetamine". J. Neurosci. 15 (2): 1308–1317. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-02-01308.1995. PMC 6577819. PMID 7869099.

- ^ a b c Mendelson J, Uemura N, Harris D, Nath RP, Fernandez E, Jacob P, Everhart ET, Jones RT (October 2006). "Human pharmacology of the methamphetamine stereoisomers". Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 80 (4): 403–420. doi:10.1016/j.clpt.2006.06.013. PMID 17015058. S2CID 19072636.

- ^ a b "San Francisco Meth Zombies". Drugs, Inc. Season 4. Episode 1. 11 August 2013. 43 minutes in. ASIN B00EHAOBAO. National Geographic Channel. Archived from the original on 8 July 2016.

- ^ United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2007). Preventing Amphetamine-type Stimulant Use Among Young People: A Policy and Programming Guide (PDF). New York: United Nations. ISBN 978-92-1-148223-2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 October 2013. Retrieved 11 November 2013.

- ^ "List of psychotropic substances under international control" (PDF). International Narcotics Control Board. United Nations. August 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 December 2005. Retrieved 19 November 2005.

- ^ "CFR TITLE 21: DRUGS FOR HUMAN USE: PART 341 – COLD, COUGH, ALLERGY, BRONCHODILATOR, AND ANTIASTHMATIC DRUG PRODUCTS FOR OVER-THE-COUNTER HUMAN USE". United States Food and Drug Administration. April 2015. Archived from the original on 18 September 2015. Retrieved 7 March 2016.

Topical nasal decongestants --(i) For products containing levmetamfetamine identified in 341.20(b)(1) when used in an inhalant dosage form. The product delivers in each 800 milliliters of air 0.04 to 0.150 milligrams of levmetamfetamine.

- ^ "Levomethamphetamine". PubChem.

- ^ Cruickshank CC, Dyer KR (July 2009). "A review of the clinical pharmacology of methamphetamine". Addiction. 104 (7): 1085–1099. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02564.x. PMID 19426289. S2CID 37079117.

- ^ Hart H, Radua J, Nakao T, Mataix-Cols D, Rubia K (February 2013). "Meta-analysis of functional magnetic resonance imaging studies of inhibition and attention in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: exploring task-specific, stimulant medication, and age effects". JAMA Psychiatry. 70 (2): 185–198. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.277. PMID 23247506.

- ^ Spencer TJ, Brown A, Seidman LJ, Valera EM, Makris N, Lomedico A, Faraone SV, Biederman J (September 2013). "Effect of psychostimulants on brain structure and function in ADHD: a qualitative literature review of magnetic resonance imaging-based neuroimaging studies". J. Clin. Psychiatry. 74 (9): 902–917. doi:10.4088/JCP.12r08287. PMC 3801446. PMID 24107764.

- ^ Ellison GD, Eison MS (1983). "Continuous amphetamine intoxication: An animal model of the acute psychotic episode". Psychological Medicine. 13 (4): 751–761. doi:10.1017/S003329170005145X. PMID 6320247. S2CID 2337423.

- ^ "Efectos psicológicos del consumo de la cocaína". Avance Psicólogos (in Spanish). 2020.

- ^ AJ Giannini, WC Price (1986). "Contemporary drugs of abuse". American Family Physician. 33: 207–213.

- ^ Talhouth R, Opperhuizen A, van Amsterdam G C J (October 2007). "Role of acetaldehyde in tobacco smoke addiction". European Neuropsychopharmacology. 17 (10): 627–636. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2007.02.013. PMID 17382522. S2CID 25866206.

- ^ Nutt DJ, King LA, Phillips LD (6 November 2010). "Drug harms in the UK: a multicriteria decision analysis". Lancet. 376 (9752): 1558–1565. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.690.1283. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61462-6. ISSN 1474-547X. PMID 21036393. S2CID 5667719.

- ^ Flavahan NA (April 2005). "Phenylpropanolamine constricts mouse and human blood vessels by preferentially activating alpha2-adrenoceptors". Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 313 (1): 432–9. doi:10.1124/jpet.104.076653. PMID 15608085. S2CID 41470513.

- ^ "Advisories, Warnings and Recalls – 2001". Health Canada. 7 January 2009. Archived from the original on 3 May 2010. Retrieved 10 January 2011.

- ^ "Drugs Banned in India". Directorate General of Health Services, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. Central Drugs Standard Control Organization. Archived from the original on 13 October 2013. Retrieved 7 January 2014.

- ^ "Lisdexamfetamine: MedlinePlus Drug Information". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 7 August 2023.

- ^ "Lisdexamfetamine Dimesylate Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Retrieved 15 April 2019.

- ^ Hunter Gillies, Wayne E. Derman, Timothy D. Noakes, Peter Smith, Alicia Evans, Gary Gabriels (1 December 1996). "Pseudoephedrine is without ergogenic effects during prolonged exercise". Journal of Applied Physiology. 81 (6): 2611–2617. doi:10.1152/jappl.1996.81.6.2611. PMID 9018513. S2CID 15702353.

- ^ Hodges K, Hancock S, Currel K, Hamilton B, Jeukendrup AE (February 2006). "Pseudoephedrine enhances performance in 1500-m runners". Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 38 (2): 329–33. doi:10.1249/01.mss.0000183201.79330.9c. PMID 16531903.

- ^ Dickens C (1856) [Digitized 19 February 2010]. "The Orsons of East Africa". Household Words: A Weekly Journal, Volume 14. Bradbury & Evans. p. 176. Retrieved 7 January 2014.

(프리북)

(프리북) - ^ a b Al-Mugahed L (October 2008). "Khat chewing in Yemen: turning over a new leaf – Khat chewing is on the rise in Yemen, raising concerns about the health and social consequences". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 8 January 2014. Retrieved 8 January 2014.

- ^ a b Nutt D, King LA, Blakemore C (March 2007). "Development of a rational scale to assess the harm of drugs of potential misuse". Lancet. 369 (9566): 1047–53. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60464-4. PMID 17382831. S2CID 5903121.

- ^ Haight-Ashbury Free Medical Clinic, 정신 활성 약물 저널, 41권, (Haight-Ashbury Publications: 2009), p.3.

- ^ 템플릿:J 저널 인용CP.0000000000001085

- ^ Mignot EJ (October 2012). "A practical guide to the therapy of narcolepsy and hypersomnia syndromes". Neurotherapeutics. 9 (4): 739–752. doi:10.1007/s13311-012-0150-9. PMC 3480574. PMID 23065655.

- ^ a b "Provigil: Prescribing information" (PDF). FDA.gov. United States Food and Drug Administration. Cephalon, Inc. January 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 February 2017. Retrieved 16 August 2015.

- ^ Kakehi S, Tompkins DM (October 2021). "A Review of Pharmacologic Neurostimulant Use During Rehabilitation and Recovery After Brain Injury". Ann Pharmacother. 55 (10): 1254–1266. doi:10.1177/1060028020983607. PMID 33435717. S2CID 231593912.

- ^ Kim D (2012). "Practical use and risk of modafinil, a novel waking drug". Environmental Health and Toxicology. 27: e2012007. doi:10.5620/eht.2012.27.e2012007. PMC 3286657. PMID 22375280.

- ^ Warot D, Corruble E, Payan C, Weil JS, Puech AJ (1993). "Subjective effects of modafinil, a new central adrenergic stimulant in healthy volunteers: a comparison with amphetamine, caffeine and placebo". European Psychiatry. 8 (4): 201–208. doi:10.1017/S0924933800002923. S2CID 151797528.

- ^ O'Brien CP, Dackis CA, Kampman K (June 2006). "Does modafinil produce euphoria?". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 163 (6): 1109. doi:10.1176/ajp.2006.163.6.1109. PMID 16741217.

- ^ Greenblatt K, Adams N (February 2022). "Modafinil". StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 30285371. NCBI NBK531476.

- ^ LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. 24 January 2012. PMID 34516055 – via PubMed.

- ^ LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. 22 January 2012. PMID 31644012 – via PubMed.

- ^ "Pitolisant Uses, Side Effects & Warnings". Drugs.com.

- ^ "List of CNS stimulants + Uses & Side Effects". Drugs.com.

- ^ a b c d Lamb YN (February 2020). "Pitolisant: A Review in Narcolepsy with or without Cataplexy". CNS Drugs. 34 (2): 207–218. doi:10.1007/s40263-020-00703-x. PMID 31997137. S2CID 210949049.

- ^ a b Kollb-Sielecka M, Demolis P, Emmerich J, Markey G, Salmonson T, Haas M (1 May 2017). "The European Medicines Agency review of pitolisant for treatment of narcolepsy: summary of the scientific assessment by the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use". Sleep Medicine. 33: 125–129. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2017.01.002. PMID 28449891 – via Europe PMC.

- ^ a b "Pitolisant (Wakix) for Narcolepsy". JAMA. 326 (11): 1060–1061. 21 September 2021. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.1349. PMID 34546302. S2CID 237583921 – via Silverchair.

- ^ de Biase S, Pellitteri G, Gigli GL, Valente M (February 2021). "Evaluating pitolisant as a narcolepsy treatment option". Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 22 (2): 155–162. doi:10.1080/14656566.2020.1817387. PMID 32941089. S2CID 221788777.

- ^ West RE, Zweig A, Shih NY, Siegel MI, Egan RW, Clark MA (November 1990). "Identification of two H3-histamine receptor subtypes". Molecular Pharmacology. 38 (5): 610–613. PMID 2172771.

- ^ Sarfraz N, Okuampa D, Hansen H, Alvarez M, Cornett EM, Kakazu J, et al. (30 May 2022). "pitolisant, a novel histamine-3 receptor competitive antagonist, and inverse agonist, in the treatment of excessive daytime sleepiness in adult patients with narcolepsy". Health Psychology Research. 10 (3): 34222. doi:10.52965/001c.34222. PMC 9239364. PMID 35774905.

- ^ Dackis CA, Gold MS (1990). "Addictiveness of central stimulants". Advances in Alcohol & Substance Abuse. 9 (1–2): 9–26. doi:10.1300/J251v09n01_02. PMID 1974121.

- ^ Huskinson SL, Naylor JE, Rowlett JK, Freeman KB (7 January 2017). "Predicting abuse potential of stimulants and other dopaminergic drugs: Overview and recommendations". Neuropharmacology. 87: 66–80. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2014.03.009. ISSN 0028-3908. PMC 4171344. PMID 24662599.

- ^ a b Stoops WW (7 January 2017). "Reinforcing Effects of Stimulants in Humans: Sensitivity of Progressive-Ratio Schedules". Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 16 (6): 503–512. doi:10.1037/a0013657. ISSN 1064-1297. PMC 2753469. PMID 19086771.

- ^ Minozzi S, Saulle R, De Crescenzo F, Amato L (29 September 2016). "Psychosocial interventions for psychostimulant misuse". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016 (9): CD011866. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011866.pub2. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 6457581. PMID 27684277.

- ^ AJ 지아니니. 마약 남용. Los Angeles, Health Information Press, 1999, pp.203–208

외부 링크

- "Long Island Council on Alcohol & Drug Dependence – About Drugs – Stimulants". Archived from the original on 5 June 2008. Retrieved 4 August 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: 잘못된 URL (링크) - "Online – Publications – Drugs of Abuse – Stimulants". Archived from the original on 22 September 2006. Retrieved 11 January 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: 잘못된 URL (링크) - 아시아 태평양 암페타민 타입 자극제 정보 센터(APAIC)