중독

| 중독 및 의존 용어집[3][4][5][2] | |

|---|---|

| |

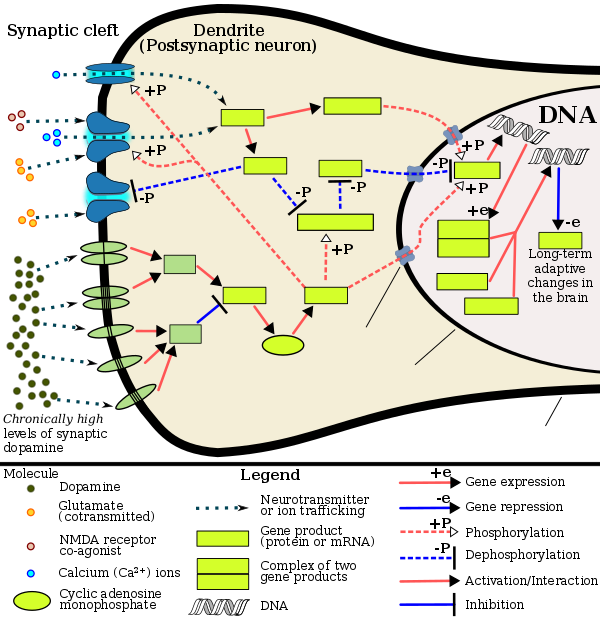

중독은 불리한 결과에도 불구하고 보상적인 자극에 강제적으로 관여하는 것이 특징인 조직사회 장애다.[3][5][2][6][7][8] 여러 가지 정신사회적 요인의 개입에도 불구하고, 중독성 자극에 반복적으로 노출되어 유발되는 생물학적 과정인 생물학적 과정이 중독의 발달과 유지를 이끄는 핵심 병리학이라고 중독의 "두뇌질환 모델"이라고 한다.[3] 그러나 중독을 연구하는 일부 학자들은 뇌질환 모델이 불완전하고 오해의 소지가 있다고 주장한다.[9][10][11][12][13][14]

뇌질환 모델은 중독이 전사와 후생적 메커니즘을 통해 발생하며 만성적으로 높은 수준의 중독성 자극(예: 음식 섭취, 코카인 사용, 성행위 참여, 하이릴 문화 참여)에 노출되는 뇌의 보상체계의 장애라고 주장한다. 도박 등의 활동.[3][15][16] 유전자 전사 인자인 델타포스B(ΔFosB)는 사실상 모든 형태의 행동 및 약물 중독의 발전에 중요한 요소이자 공통 요인이다.[15][16][17][18] 20년 동안 ΔFosB의 중독성 역할에 대한 연구는 핵의 D1형 중간 가시가 있는 뉴런에서 ΔFosB의 과도한 압박과 함께 중독이 발생하며 관련 강박적 행동이 강화되거나 약화된다는 것을 입증했다.[3][15][16][17] ΔFosB의 발현과 중독의 인과관계 때문에, 사전 임상적으로 중독 바이오마커로 사용된다.[3][15][17] ΔFosB 표현은 이러한 뉴런에 직접적이고 긍정적으로 약물 자기관리와 양성강화를 통해 보상감작성을 조절하는 동시에 혐오의 민감성은 감소시킨다.[note 1][3][15]

중독은 개인과 사회 전체에 "놀랄 정도로 높은 재정 및 인적 통행료"를 부과한다.[19][20][21] 미국에서, 사회에 미치는 총 경제적 비용은 모든 종류의 당뇨병과 모든 암을 합친 것보다 더 크다.[21] 이러한 비용은 약물 및 관련 의료 비용(예: 응급의료 서비스 및 외래 및 입원 치료), 장기 합병증(예: 담배 제품 흡연으로 인한 폐암, 만성 알코올 소비로 인한 간경화 및 치매, 필로폰 사용으로 인한 필로폰 입), 손실에 의해 발생한다. 생산성 및 관련 복지 비용, 치명적 및 비폭력적 사고(예: 교통사고), 자살, 살인 및 감금 등.[19][20][21][22] 중독의 전형적인 특징으로는 물질이나 행동에 대한 통제력 저하, 물질이나 행동에 대한 집착, 그리고 결과에도 불구하고 계속적인 사용 등이 있다.[23] 중독과 관련된 습관과 패턴은 전형적으로 즉각적인 만족(단기 보상)과 지연된 해로운 효과(장기 비용)를 결합한 것이 특징이다.[24]

역사를 통틀어 중독의 어원은 종종 오해를 받아 그 단어와 관련된 다양한 의미를 취해왔다. 일례로 초기 근대기 말의 용법이 있다. 그때의 '중독'은 어떤 것에 '붙이기'를 의미했고, 긍정적인 의미와 부정적인 의미를 동시에 부여했다. 이 애착의 대상은 "좋은지 나쁜지"[25]로 특징지어질 수 있지만, 이 기간 동안의 중독의 의미는 대부분 긍정과 선함과 관련이 있었다. 신앙이 두터운 시대에는 '다른 사람에게 몸을 바치는' 방법으로 비쳤다.[25] 중독에 대한 현대적인 연구는 1875년으로 거슬러 올라가는 주제, 특히 모르핀 중독에 대한 연구 연구로 그 병에 대한 더 나은 이해를 이끌어냈다.[26] 이것은 중독이 의학적인 조건이라는 이해를 심화시켰다. 19세기에 이르러서야 중독은 의학적으로나 정신적으로나 질병으로 보여지고 인정되었다.[27]

오늘날, 중독은 가장 일반적으로 약물 및 알코올 남용과 관련이 있는, 진단받은 사람들에게 부정적인 영향을 미치는 질병으로 이해되고 있다. 중독에 대한 이해는 철저한 역사를 변화시켰고, 이것은 의학적으로 치료되고 진단되는 방식에 영향을 미치고 있다.

약물 및 행동 중독의 예로는 알코올 중독, 마리화나 중독, 암페타민 중독, 코카인 중독, 니코틴 중독, 오피오이드 중독, 음식 중독, 초콜릿 중독, 비디오 게임 중독, 도박 중독, 성 중독 등이 있다. DSM-5와 ICD-10이 인정한 유일한 행동 중독은 도박 중독이다. ICD-11 게임 중독이 추가되었다.[28] "중독"이라는 용어는 뉴스 매체에서 다른 강박적 행동이나 장애, 특히 의존성을 언급할 때 자주 오용된다.[29] 약물 중독과 의존성의 중요한 구분은 약물 의존이 약물 사용을 중단하면 불쾌한 금단 상태가 되어 약물 사용을 더 이상 유발할 수 있는 질환이라는 점이다.[30] 중독은 어떤 물질의 강제적인 사용이나 금단과는 무관한 행동의 수행이다. 중독은 의존이 없을 때 발생할 수 있고, 의존은 비록 두 가지가 함께 일어나는 경우가 많지만 중독이 없을 때 발생할 수 있다.

신경심리학

작동자 및 고전적 조건조절과 관련된 인지조절과 자극조절은 개인의 도출된 행동의 통제를 놓고 경쟁하는 반대 과정(즉, 내부 대 외부 또는 환경)을 나타낸다.[31] 인지적 통제, 특히 행동에 대한 억제적 통제는 중독과 주의력 결핍 과잉행동 장애 모두에서 손상된다.[32][33] 특정 보람된 자극과 관련된 자극 중심의 행동 반응(즉, 자극 조절)은 중독에서 자신의 행동을 지배하는 경향이 있다.[33]

행동의 자극 제어

행동의 인지적 통제

행동 중독

"행동중독"이란 불리한 결과에도 불구하고 자연적인 보상(즉, 바람직한 행위 또는 호소력 있는 행위)에 종사하도록 강요하는 것을 말한다.[7][16][18] 임상 전 증거는 자연적 보상에 대한 반복적이고 과도한 노출을 통해 ΔFosB의 표현이 현저하게 증가하면 약물 중독에서 일어나는 것과 동일한 행동 효과와 신경 재생성을 유발한다는 것을 입증했다.[16][34][35][36]

인간에 대한 임상 연구와 ΔFosB와 관련된 임상 전 연구 둘 다에 대한 리뷰를 통해 강박적 성행위, 특히 성관계의 모든 형태는 중독(즉, 성중독)으로 확인되었다.[16][34] 게다가 amphetamine 그리고 성적 활동 사이에 보상 교차 감작, 저것보다 의 폭로에 대한 욕망을 증가시키는 것을 의미하며, preclinically고 있으면 도파민의 불규칙함이다 증후군으로 발생할;[16][34][35][36]ΔFosB 않ΔFo의 수준을 격화시킨다 이 교차 감작 효과에 필요한 있다는 것을 보였다.sB 표현이다.[16][35][36]

임상 전 연구에 대한 리뷰는 고지방이나 설탕 식품의 장기간 빈번하고 과다한 섭취가 중독(식품 중독)을 유발할 수 있다는 것을 보여준다.[16][18] 이것은 초콜릿을 포함할 수 있다. 초콜릿의 달콤한 맛과 약리학적 성분은 소비자에 의해 강한 갈망을 일으키거나 '중독성'을 느끼는 것으로 알려져 있다.[37] 초콜릿을 좋아하는 사람은 자신을 초코홀릭이라고 부를 수도 있다. 초콜릿은 아직 DSM-5에 의해 진단 가능한 중독으로 공식적으로 인식되지 않는다.[38]

도박은 강제적인 행동과 관련되고 임상 진단 매뉴얼, 즉 DSM-5가 "중독"[16]에 대한 진단 기준을 식별한 자연적인 보상을 제공한다. 사람의 도박행위가 중독의 기준을 충족시키기 위해서는 기분전환, 강박, 금단 등 일정한 특징을 보인다. 기능적 신경영상으로부터 도박이 특히 보상체계와 중절제 경로를 활성화시킨다는 증거가 있다.[16][39] 마찬가지로, 쇼핑과 비디오 게임은 인간의 강박적인 행동과 연관되어 있으며, 또한 중음부 경로와 보상 시스템의 다른 부분을 활성화시키는 것으로 보여진다.[16] 이를 근거로 도박중독, 비디오게임중독, 쇼핑중독 등이 이에 따라 분류된다.[16][39]

위험요소

중독의 발달을 위한 많은 유전적, 환경적 위험 요소들이 있는데, 이것은 인구마다 다르다.[3][40] 유전적 및 환경적 위험 요인은 각각 중독에 대한 개인의 위험의 약 절반을 차지한다.[3] 후생적 위험 요인의 전체 위험으로의 기여는 알려져 있지 않다.[40] 상대적으로 유전적 위험이 낮은 개인에서도 장기간(예: 몇 주-개월) 충분한 양의 중독성 약물에 노출되면 중독이 발생할 수 있다.[3]

유전인자

환경적(예: 심리사회적) 요소와 함께 유전적 요인이 중독 취약성의 유의미한 원인이라는 것이 오래 전부터 확립되어 왔다.[3][40] 역학 연구는 유전적 요인이 알코올 중독 위험 요인의 40~60%를 차지한다고 추정한다.[41] 다른 유형의 약물 중독에 대한 유사한 유전율도 다른 연구에 의해 나타났다.[42] Knestler는 1964년에 유전자 또는 유전자의 그룹이 여러 가지 방법으로 중독의 성향을 일으키는 원인이 될 수 있다는 가설을 세웠다. 예를 들어, 환경적 요인으로 인해 정상 단백질의 수치가 변화하면 개발 중에 특정 뇌 뉴런의 구조나 기능을 변화시킬 수 있다. 이러한 변화된 뇌 뉴런은 초기 약물 사용 경험으로 개인의 민감성을 변화시킬 수 있다. 이 가설을 뒷받침하기 위해, 동물 연구는 스트레스와 같은 환경적 요인이 동물의 유전자형에 영향을 줄 수 있다는 것을 보여주었다.[42]

전반적으로 약물 중독의 발달에 특정 유전자를 포함하는 데이터는 대부분의 유전자에 혼합되어 있다. 한 가지 이유는 이 사례가 일반적인 변형에 대한 현재 연구의 초점이 맞춰져 있기 때문일 수 있다. 많은 중독 연구는 일반 인구에서 알레르기가 5% 이상인 일반적인 변종에 초점을 맞추고 있으나 질병과 관련되었을 때 1.1–1.3%의 확률로 적은 양의 추가 위험만 부여한다. 반면 희귀한 변종 가설은 인구에서 빈도가 낮은 유전자(<1%)가 질병발달에 훨씬 더 큰 추가 위험을 부여한다고 밝히고 있다.[43]

게놈전역 연관 연구(GWAS)는 의존성, 중독성, 약물 사용 등이 있는 유전적 연관성을 검사하는 데 사용된다. 이러한 연구들은 특정 표현형태를 가진 유전적 연관성을 찾는 편견 없는 접근방식을 채택하고 있으며, 약물 대사나 반응과 표면적인 관계가 없는 것을 포함한 DNA의 모든 영역에 동일한 가중치를 부여한다. 이러한 연구들은 동물성 녹아웃 모델과 후보 유전자 분석을 통해 이전에 기술된 단백질에서 나온 유전자를 거의 식별하지 못한다. 대신 세포 접착과 같은 과정에 관여하는 유전자의 큰 비율이 일반적으로 확인된다. 그렇다고 이전의 연구결과, 즉 GWAS의 연구결과가 잘못되었다고 말하는 것은 아니다. 자궁내막염의 중요한 영향은 일반적으로 이러한 방법에 의해 포착될 수 없다. 더욱이, 약물 중독에 대해 GWAS에서 확인된 유전자는 약물 경험 이전의 뇌 행동 조절, 그 이후의 뇌 행동 조절 또는 둘 다에 관여할 수 있다.[44]

중독에서 유전학이 차지하는 중요한 역할을 강조하는 연구는 쌍둥이 연구다. 쌍둥이는 유사하고 때로는 동일한 유전자를 가지고 있다. 유전자와 관련하여 이러한 유전자를 분석하는 것은 유전자가 중독에서 얼마나 많은 역할을 하는지 유전학자들이 이해하는 데 도움이 되었다. 쌍둥이를 대상으로 한 연구에서 쌍둥이 중 한 명만 중독된 경우는 거의 없다는 사실이 밝혀졌다. 적어도 한 쌍둥이가 중독에 걸린 대부분의 경우, 두 쌍둥이는 중독에 걸렸고, 종종 같은 물질로 고통을 받았다.[45] 교차 중독은 이미 중독이 성행하고 나서 다른 무언가에 중독되기 시작하는 것이다. 한 가족 구성원이 중독의 이력이 있다면, 친척이나 가까운 가족이 이런 같은 습관을 갖게 될 가능성은 어린 나이에 중독에 입문하지 않은 가족보다 훨씬 높다.[46] 국립마약학술연구소가 실시한 최근 연구에서 2002년부터 2017년까지, 과다복용 사망자는 남성과 여성 사이에서 거의 세 배가 되었다. 2017년 미국에서 발생한 과다복용 사망자는 7만2306명.[47] 2020년에는 12개월 동안 가장 높은 약물 과다복용 사망자가 기록되었다. 약물 과다복용 사망자는 8만1000명으로 2017년부터 기하급수적으로 기록을 넘어섰다.[48]

환경요인

중독에 대한 환경적 위험 요인은 개인의 유전적 구성과 상호 작용하여 중독에 대한 취약성을 증가시키거나 감소시키는 개인의 일생 동안의 경험이다.[3] 예를 들어, COVID-19가 전국적으로 발발한 후, 더 많은 사람들이 담배를 끊었고 (대부분의) 흡연자들은 평균적으로 그들이 소비하는 담배의 양을 줄였다.[49] 좀 더 일반적으로, 다양한 정신사회적 스트레스 요인을 포함하여, 중독의 위험요인으로 많은 다른 환경요인들이 연루되어 있다. 국립마약학술연구소(NIDA)는 부모의 감독 부족, 또래 약물 사용의 유병, 약물 가용성, 빈곤 등을 아동·청소년의 약물 사용 위험 요인으로 꼽고 있다.[50] 중독의 뇌질환 모델은 중독성 약물에 대한 개인의 노출이 중독에 대한 가장 중요한 환경적 위험 요소라고 주장한다.[51] 그러나 신경과학자를 포함한 많은 연구자들은 뇌질환 모델이 중독에 대한 오해의 소지가 있고 불완전하며 잠재적으로 해로운 설명을 제시한다고 지적한다.[52]

아동기에 대한 부정적인 경험은 아동기에 경험하는 다양한 형태의 학대 및 가정 장애다. 질병관리본부의 아동기 부작용 연구는 ACE와 약물 남용을 포함한 개인의 수명 전반에 걸쳐 수많은 건강, 사회, 행동 문제들 사이의 강한 용량-반응 관계를 보여주었다.[53] 신체적, 정서적, 성적 학대, 신체적 또는 정서적 무시, 가정 내 폭력을 목격하거나 부모가 감금되거나 정신 질환을 앓는 등 스트레스를 많이 받는 사건에 만성적으로 노출되면 아이들의 신경학적 발달이 영구적으로 교란될 수 있다. 그 결과, 아이의 인지 기능이나 부정적이거나 파괴적인 감정에 대처하는 능력이 손상될 수 있다. 시간이 지남에 따라, 아이는 특히 청소년기에 약물 사용을 대처 메커니즘으로 채택할 수 있다.[53] 학대를 경험한 어린이들이 관련된 900건의 법정 사건을 조사한 결과, 그들 중 많은 수가 청소년기나 성인 생활에서 어떤 형태의 중독으로 고통 받는 것으로 나타났다.[54] 어린 시절 스트레스를 받는 경험을 통해 개방된 중독으로 가는 이러한 길은 개인의 삶 전반에 걸친 환경적 요인의 변화와 전문적인 도움의 기회를 통해 피할 수 있다.[54] 마약 사용에 호의적인 친구나 동료가 있다면 중독에 걸릴 확률이 높아진다. 가족간의 갈등과 가정관리는 술이나 다른 약물 사용에 관여하게 되는 원인이기도 하다.[55]

나이

청소년기는 중독을 일으키기 위한 독특한 취약성의 시기를 나타낸다.[56] 청소년기에 뇌의 인센티브 보상 시스템은 인지 통제 센터보다 훨씬 앞서 성숙한다. 결과적으로 인센티브 보상 시스템은 행동 의사결정 과정에서 불균형한 양의 힘을 부여한다. 그러므로, 청소년들은 결과를 고려하기 전에 점점 더 그들의 충동에 따라 행동하고 위험하고 잠재적으로 중독적인 행동을 할 가능성이 높다.[57] 청소년들은 약물 사용을 시작하고 유지할 가능성이 더 높을 뿐만 아니라, 일단 중독되면 치료에 더 저항력이 있고 재발하기 쉽다.[58][59]

통계에 따르면 어린 나이에 술을 마시기 시작하는 사람들은 나중에 의존하게 될 가능성이 더 높다. 인구의[where?] 약 33%가 15~17세 사이의 첫 술을 맛봤고, 18%는 이에 앞서 경험했다. 알코올 남용이나 의존성에 대해서는 12세 이전에 처음 술을 마셨다가 그 후에 끊어진 사람들로부터 높은 수치가 시작된다. 예를 들어, 알코올 중독자의 16%는 12살이 되기 전에 술을 마시기 시작했으며, 9%만이 15세에서 17세 사이의 알코올에 처음 손을 댔다. 이 비율은 심지어 21세 이후에 처음 이 습관을 시작한 사람들의 2.6%로 더 낮다.[60]

대부분의 개인들은 십대 때 처음으로 중독성 있는 약물에 노출되어 복용한다.[61] 미국에서는 2013년 불법 마약 신규 가입자가 280만 명(하루 약 7,800명)을 조금 넘었고,[61] 이 가운데 54.1%가 18세 미만이었다.[61] 2011년 미국에는 12세 이상의 약 2060만 명의 사람들이 중독되었다.[62] 중독된 사람들의 90% 이상이 18세 이전에 음주, 흡연, 불법 약물 사용을 시작했다.[62]

코모비드 장애

우울증, 불안증, 주의력 결핍/열행동 장애(ADHD) 또는 외상 후 스트레스 장애와 같은 코모르비드(공동발생) 정신 건강 장애를 가진 사람들은 약물 사용 장애를 더 많이 일으킬 가능성이 있다.[63][64][65] 물질 사용의 위험 요소로서 초기 공격적인 행동을 인용한다.[50] 국립경제과학원 연구결과 '정신질환과 중독성 물질 사용 사이에는 확실한 연관성이 있으며, 알코올 38%, 코카인 44%, 담배 40% 등 정신건강 환자 대다수가 이 물질 사용에 참여하고 있는 것으로 나타났다.[66]

후생유전학

전세대 후생유전 상속

(예:프로틴)은 가장 중요한 구성 요소Epigenetic 유전자와 그들의 상품을 통하여 환경 영향,[40]그들은 또한 그 메커니즘transgenerational 후생 유전학적 유산에 대한 책임을 지는 부모의 유전자에 환경 영향은 관련된 tra에 영향을 미칠 수 있는 현상인 역할을 한 개인의 유전자에 영향을 미칠 수 있다.그것의 그리고 그들의 자손의 행동 표현 유형(예: 환경 자극에 대한 행동 반응).[40] 중독에서 후생 유전학적 메커니즘 그 병의 병리 생리학의 일부 후생 유전자에 중독성이 자극에 장기 노출을 통해 중독 중에 발생하는 변화 여러세대에 걸쳐 차례로 아이들을 행동(예:그 아이의 beh에 영향을 미치는 전달될 수 있어 지적한 바[3]중심 역할을 한다.av중독성 있는 약물과 자연적인 보상에 대한 발기부전 반응).[40][67]

전세대 후생유전유전에 관련되었던 후생유전적 변경의 일반적인 종류에는 DNA 메틸화, 히스톤 수정, 그리고 마이크로RNA의 다운규제 또는 상향규제가 포함된다.[40] 중독과 관련하여, 인간의 다양한 형태의 중독에서 발생하는 특정한 유전적 후생유전적 변화들과 인간의 자손에게서 발생하는 이러한 후생유전적 변화로부터 발생하는 상응하는 행동적 표현형을 결정하기 위한 더 많은 연구가 필요하다.[40][67] 동물 연구에서 얻은 임상 전 증거에 기초하여 쥐의 특정 중독 유발 후생유전적 변화는 부모에서 자손에게까지 전달될 수 있고, 자손이 중독에 걸릴 위험을 감소시키는 행동적 표현형을 만들어낼 수 있다.[note 2][40] 보다 일반적으로, 중독에 의한 후생유전적 변화로부터 파생되어 부모로부터 자손에게 전달되는 유전적 행동 표현형태는 자손이 중독에 걸릴 위험을 증가시키거나 감소시키는 역할을 할 수 있다.[40][67]

남용책임

중독 책임이라고도 하는 남용 책임은 비의료적 상황에서 약을 사용하는 경향이다. 이것은 전형적으로 행복감, 기분전환, 진정 등을 위한 것이다.[68] 남용 책임은 약을 사용하는 사람이 그렇지 않으면 얻을 수 없는 것을 원할 때 사용된다. 이것을 얻는 유일한 방법은 약물을 사용하는 것이다. 남용 책임을 볼 때, 그 약물이 남용되는지 여부를 결정하는 많은 요소들이 있다. 이러한 요인은 약물의 화학적 구성, 뇌에 미치는 영향, 연구 대상 인구의 나이, 취약성, 건강(정신적, 신체적) 등이다.[68] 특정한 화학적 구성을 가진 몇 가지 약물이 있어 높은 남용 책임으로 이어진다. 코카인, 헤로인, 흡입제, LSD, 마리화나, MDMA(에스티스), 필로폰, PCP, 합성 카나비노이드, 합성 카티논(욕실염), 담배, 알코올 등이 그것이다.[69]

메커니즘

| 전사 계수 용어집 | |

|---|---|

| |

만성적인 중독성 약물 사용은 중구체성 투영에서 유전자 발현에 변화를 일으킨다.[18][77][78] 이러한 변화를 일으키는 가장 중요한 전사 인자는 ΔFosB, cAMP 대응 요소 결합 단백질(CREB), 핵 인자 카파 B(NF-κB)이다.[18] ΔFosB는 중독에서 가장 중요한 생체분자 메커니즘이다. 왜냐하면 핵 억양의 D1형 중간 가시가 있는 신경세포의 ΔFosB의 과도한 억제가 많은 신경적 적응과 행동 효과(예: 약물 자가 관리 및 보상 감작성의 표현 의존적 증가)에 필요하고 충분하기 때문이다. 약물 [18]중독 핵의 ΔFosB 표현은 D1형 중간 가시가 있는 뉴런을 직접, 그리고 양극 보강을 통해 약물 자기관리와 보상 감작성을 긍정적으로 조절하는 동시에 혐오의 감수성을 감소시킨다.[note 1][3][15] ΔFosB는 알코올, 암페타민 및 기타 대체 암페타민, 카나비노이드, 코카인, 메틸페니데이트, 니코틴, 아편제, 페닐사이클로딘, 프로포폴 등 여러 가지 약물 및 약물 등급에 대한 매개 중독에 관여해왔다.[15][18][77][79][80] 전사 인자인 ΔJunD와 히스톤 메틸전달효소인 G9a는 모두 ΔFosB의 기능에 반대하며 표현력 증가를 억제한다.[3][18][81] 핵의 증가는 (바이러스 벡터 매개 유전자 전달을 통한) ΔJunD 발현이나 (약리학적 수단을 통한) G9a 발현을 감소시키거나, 또는 크게 증가하면 중독성 약물의 만성 고선량 사용에서 발생하는 많은 신경 및 행동 변화(즉, ΔFOSB에 의해 매개된 변화)를 차단할 수 있다.[17][18]

ΔFosB는 또한 입맛에 맞는 음식, 섹스, 운동과 같은 자연적인 보상에 대한 행동 반응을 조절하는 데 중요한 역할을 한다.[18][82] 자연적인 보상은 남용 약물과 마찬가지로 핵에서 ΔFosB의 유전자 발현을 유도하고, 이러한 보상의 만성적인 획득은 ΔFosB 과다 억제를 통해 유사한 병리학적 중독 상태를 초래할 수 있다.[16][18][82] 따라서 ΔFosB는 자연 보상 중독(즉, 행동 중독)에도 관여하는 주요 전사 요인이다.[18][16][82] 특히, 핵의 ΔFosB는 성적 보상의 강화 효과에 매우 중요하다.[82] 자연적 보상과 약물적 보상 사이의 상호작용에 관한 연구는 도파민성 정신운동제(예: 암페타민)와 성행동이 유사한 생체분자 메커니즘에 작용하여 측핵에서 ΔFosB를 유도하고 ΔFosB를 통해 매개되는 양방향 교차감지 효과를 갖는다는 것을 시사한다.[16][35][36] 이러한 현상은 인간의 경우 약물 유도 자연 보상(특히 성행위, 쇼핑, 도박)에 대한 강박적 관여가 특징인 도파민 과민조절 증후군이 일부 개인에서도 관찰되었기 때문에 두드러진다.[16]

ΔFosB 억제제(약물이나 그 작용에 반대하는 치료제)는 중독과 중독성 장애에 효과적인 치료제일 수 있다.[83]

핵에 도파민이 분비되는 것은 입맛에 맞는 음식이나 섹스와 같은 자극을 자연적으로 강화시키는 것을 포함하여 많은 형태의 자극의 특성을 강화시키는 역할을 한다.[84][85] 중독성 상태의 발달에 따라 변화된 도파민 신경전달은 자주 관찰된다.[16] 중독이 발병한 인간과 실험동물의 경우, 세포핵과 선조체의 다른 부분에서 도파민이나 오피오이드 신경전달의 변화가 뚜렷이 나타난다.[16] 연구 결과에 따르면 특정 약물(예: 코카인)의 사용은 보상 시스템을 내향적으로 만드는 콜린거 뉴런에 영향을 미치고, 그 결과 이 지역의 도파민 신호에 영향을 미친다고 한다.[86]

포상제도

이 구간은 확장이 필요하다. 덧셈을 하면 도움이 된다. (2015년 8월) |

메소코르티컬임브길

약물 중독의 생물학적 근거를 조사할 때 약물이 작용하는 경로와 약물이 그러한 경로를 어떻게 바꿀 수 있는지를 이해하는 것이 중요하다. 상경로, 즉 그 연장인 중경로(mesocorticolimb)는 뇌의 여러 부위가 상호 작용하는 것이 특징이다.

- 복측 테그먼트 영역(VTA)에서 나온 투영은 공동 국부화된 후 글루탐산 수용체(AMPAR, NMDAR)를 가진 도파민성 뉴런의 네트워크다. 이 세포들은 보상을 나타내는 자극이 있을 때 반응한다. VTA는 학습 및 감작성 개발을 지원하고 DA를 전뇌에 방출한다.[88] 이 뉴런들은 또한 DA를 중음부 경로를 통해 [89]측점핵으로 투사하여 방출한다. 사실상 약물 중독을 유발하는 모든 약물은 그들의 특정한 효과 외에도 중간중간 경로에서 도파민 분비량을 증가시킨다.[90]

- 핵은 VTA 돌출부의 한 출력물이다. 핵 자체는 주로 GABAergic medium spiny nerrones (MSN)으로 구성되어 있다.[91] 국가 조치계획(NAcc)은 조건부 행동을 획득하고 유도하는 것과 관련이 있으며, 중독이 진행됨에 따라 약물에 대한 민감도가 증가하는 것과 관련이 있다.[88] 응축된 핵에서 ΔFosB의 과도한 억제는 기본적으로 알려진 모든 형태의 중독에 필요한 공통 요인이다. [3]ΔFosB는 양성 강화 행동의 강한 양성 변조기이다.[3]

- 전두엽 피질 및 전두엽 피질 궤도를 포함한 전두엽 피질은 [92]중두엽 피질 경로에서 또 다른 VTA 출력이다. 어떤 행동이 도출되는지 여부를 결정하는 데 도움이 되는 정보의 통합에 중요하다.[93] 그것은 또한 약물 사용의 보람된 경험과 환경에서의 단서들 사이의 연관성을 형성하는데 중요하다. 중요한 것은 이러한 단서들이 마약추구행위의 강력한 중재자여서 몇 달 혹은 몇 년의 금욕 후에도 재발할 수 있다는 점이다.[94]

중독과 관련된 다른 뇌 구조는 다음과 같다.

- 근측 편도체는 NAcc에 투영되며 동기 부여에도 중요한 것으로 생각된다.[93]

- 해마는 학습과 기억력에 대한 역할 때문에 약물 중독에 관여한다. 이 증거의 대부분은 해마의 세포를 조작하는 것이 NAcc의 도파민 수치와 VTA 도파민 세포의 발화율을 변화시킨다는 것을 보여주는 조사 결과에서 비롯된다.[89]

도파민과 글루탐산염의 역할

도파민은 뇌의 보상체계의 주요 신경전달물질이다. 그것은 움직임, 감정, 인지, 동기, 쾌락의 감정을 조절하는 역할을 한다.[95] 먹는 것과 같은 자연적인 보상은 물론 오락성 약물 사용도 도파민의 분비를 유발하며, 이러한 자극의 성질을 강화시키는 것과 관련이 있다.[95][96] 거의 모든 중독성 약물은 직간접적으로 도파민 활성을 높임으로써 뇌의 보상체계에 작용한다.[97]

많은 종류의 중독성 약물을 과다하게 섭취하면 고량의 도파민이 반복적으로 분비되며, 도파민 수용체 활성화가 강화되어 보상 경로에 직접 영향을 미친다. 시냅스 구분의 도파민 수치가 장기간 비정상적으로 높으면 신경 경로에서 수용체 다운 조절을 유도할 수 있다. 중합성 도파민 수용체 감속은 자연보강제에 대한 민감도를 감소시킬 수 있다.[95]

약물탐구행위는 전두엽 피질에서 측핵까지 글루타마테라믹한 투영에 의해 유도된다. 이 아이디어는 AMPA 글루탐산 수용체 억제와 측핵에서의 글루탐산수 방출에 따른 약물 탐색 행동을 예방할 수 있다는 것을 보여주는 실험의 데이터로 뒷받침된다.[92]

보상 감작성

| 대상 유전자를 붙이다 | 대상 표현 | 신경 효과 | 행동 효과 |

|---|---|---|---|

| c-Fos | ↓ | 만성적인 상태를 가능하게 하는 분자 스위치 ΔFosB[note 3] 유도 | – |

| 다이노핀 | ↓ [주4] | • κ-opioid 피드백 루프 다운조절 | • 약물 보상 증가 |

| NF-226B | ↑ | • 국가 조치계획(NAcc dendritic process)의 확대 • NF-sollb 염증 반응: • NF-sollb 염증 반응: | • 약물 보상 증가 • 약물 보상 증가 • 기관차 감작성 |

| 글루R2 | ↑ | • 글루타민에 대한 민감도 감소 | • 약물 보상 증가 |

| Cdk5 | ↑ | • GluR1 시냅스 단백질 인산화 • 덴드리트 프로세스 확장 | 의약품 보상 감소 (순효과) |

보상 감작(reward sensitization)은 뇌가 보상 자극(예: 약물)에 할당한 보상량(특히, 인센티브 제공[note 5])의 증가를 유발하는 과정이다. 간단히 말해서, 특정 자극(예: 약물)에 대한 보상 감작화가 일어날 때, 자극 그 자체와 그에 연관된 단서들에 대한 개인의 "욕구"나 욕구가 증가한다.[100][99][101] 보상 감작성은 일반적으로 만성적으로 높은 수준의 자극 노출 후에 발생한다. ΔFosB (DeltaFosB) 표현은 핵 억양의 D1형 중간 가시가 있는 뉴런에서 약물과 자연 보상이 포함된 보상 감작성을 직접적이고 긍정적으로 조절하는 것으로 나타났다.[3][15][17]

중독에서 발생하는 욕망의 한 형태인 "큐에 의한 욕구" 또는 "큐에 의해 유발된 욕구"는 중독을 가진 사람들이 보여주는 대부분의 강박적인 행동에 책임이 있다.[99][101] 중독의 발전 과정에서, 그렇지 않으면 그리고 심지어non-rewarding 중립을 자극한 약물 섭취로 반복 조합 중독성 약물 사용(즉, 그러한 자극 함수에 마약 단서로 시작하)의 조건 긍정적인 강화 물로서 활동하기 전에는 중립적인 자극을 유발하는 연상 배움의 과정을 촉발시킨다.[99][102][101] 약물 사용에 대한 조건화된 긍정적인 강화제로서, 이러한 이전의 중립적 자극은 인센티브 만족도(욕망으로 나타나며), 때로는 보상 민감화로 인해 병리학적으로 높은 수준에서 할당되며, 이는 원래 짝을 이룬 1차 강화제(예:[99][102][101] 중독성 약물의 사용)로 이행될 수 있다.

자연적 보상과 약물적 보상 사이의 상호작용에 관한 연구는 도파민성 심리 자극제(예: 암페타민)와 성행위가 유사한 생체분자 메커니즘에 작용하여 측점핵에서 ΔFosB를 유도하고 ΔFOSB를 통해 매개되는 양방향 보상 교차감각 효과를[note 6] 갖는다는 것을 시사한다.[16][35][36] ΔFosB의 보상 감지 효과와 대조적으로 CREB 전사 활동은 물질의 보상 효과에 대한 사용자의 민감도를 감소시킨다. 뇌핵에서의 CREB 전사는 심리적 의존성과 약물 금단 기간 동안의 즐거움이나 동기 부족을 수반하는 증상에 관련되어 있다.[3][87][98]

특히 RGS4와 RGS9-2 등 "G 단백질 신호의 조절기"(RGS)로 알려진 단백질 세트는 보상 감작화를 포함한 일부 형태의 오피오이드 감작성 변조에 관여했다.[103]

| 신경 재생성의 형태 또는 행동의 가소성 | 보강재 유형 | 원천 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 오파테스 | 정신운동제 | 고지방 또는 설탕 식품 | 성교, 교접 | 체조, 운동 (iii) | 환경 농축 | ||

| ΔFosB 식 핵이 응축D1형MSNs | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | [16] |

| 행동적 소성 | |||||||

| 섭취 에스컬레이션 | 네 | 네 | 네 | [16] | |||

| 정신운동제 교차감각 | 네 | 해당되지 않음 | 네 | 네 | 감쇠됨 | 감쇠됨 | [16] |

| 정신운동제 자화자기의 | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | [16] | |

| 정신운동제 조건부 장소 선호도 | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ | ↑ | ↓ | ↑ | [16] |

| 마약추구행위의 회복 | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ | ↓ | [16] | ||

| 신경화학적 가소성 | |||||||

| CREB인산화 중앙부에. | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | [16] | |

| 감작 도파민 반응 중앙부에. | 아니요. | 네 | 아니요. | 네 | [16] | ||

| 변형된 선조체 도파민 신호 | ↓DRD2, ↑DRD3 | ↑DRD1, ↓DRD2, ↑DRD3 | ↑DRD1, ↓DRD2, ↑DRD3 | ↑DRD2 | ↑DRD2 | [16] | |

| 선조체 오피오이드 신호 변경 | 변경 없음 또는 μ-오피오이드 수용체 | μ-오피오이드 수용체 ↑κ-오피오이드 수용체 | μ-오피오이드 수용체 | μ-오피오이드 수용체 | 잔돈 없음 | 잔돈 없음 | [16] |

| 선조체 오피오이드 펩타이드의 변화 | ↑dynorphin 변화 없음: 엥케팔린 | ↑dynorphin | ↓케팔린 | ↑dynorphin | ↑dynorphin | [16] | |

| 메소코르티컬임브 시냅스 가소성 | |||||||

| 핵에 포함된 덴드라이트 수 | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | [16] | |||

| 덴드리트 척추 밀도: 핵이 수축하다. | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | [16] | |||

신경유전학 메커니즘

뇌의 보상체계 내에서 유전자 발현에 대한 후생유전학적 조절이 변화된 것은 약물 중독의 발달에 중요하고 복잡한 역할을 한다.[81][104] 중독성 있는 약물은 뉴런 내에서 세 가지 유형의 후생유전적 변형과 연관되어 있다.[81] (1) 히스톤 수정, (2) 특정 유전자에 인접한 CpG 현장에서 DNA의 후생유전적 메틸화, (3) 후생유전적 다운조절 또는 특정 표적 유전자를 갖는 마이크로RNA의 상향조절 등이다.[81][18][104] 예를 들어, 핵의 세포에 있는 수백 개의 유전자가 약물 피폭에 따른 히스톤 수정(특히 히스톤 잔여물의[104] 아세틸화 및 메틸화 상태 변화)을 보이는 반면, NAc 세포의 다른 대부분의 유전자는 그러한 변화를 보이지 않는다.[81]

진단

제5판 정신장애 진단 및 통계 매뉴얼(DSM-5)에서는 약물 사용 관련 장애의 스펙트럼을 가리키기 위해 "보조 사용 장애"라는 용어를 사용한다. DSM-5는 진단 범주에서 "오용" 및 "의존성"이라는 용어를 삭제하며, 대신 순한, 중간 및 심각성의 지정자를 사용해 불순종 사용의 정도를 표시한다. 이러한 지정자는 특정 사례에 존재하는 진단 기준의 수에 의해 결정된다. DSM-5에서 약물 중독이라는 용어는 심각한 약물 사용 장애와 동의어다.[1][2]

DSM-5는 행동 중독에 대한 새로운 진단 범주를 도입했지만, 문제 도박은 5판의 그 범주에 포함된 유일한 조건이다.[29] 인터넷 게임 장애는 DSM-5에서 "더 많은 연구가 필요한 조건"으로 언급되어 있다.[105]

과거 판은 신체적 의존성과 관련 금단증후군을 이용해 중독 상태를 파악했다. 신체적 의존은 신체가 "정상적인" 기능, 즉 동점선에 도달하여 조정했을 때 발생하며, 따라서 사용 중단 시 신체적인 철수 증상이 나타난다.[106] 내성은 신체가 물질에 지속적으로 적응하는 과정이며 원래의 효과를 얻기 위해 점점 더 많은 양을 요구한다. 금단증상은 신체가 의존하게 된 물질을 줄이거나 중단할 때 경험하는 신체적, 심리적 증상을 말한다. 금단 증상은 일반적으로 몸살, 불안, 자극성, 물질에 대한 강렬한 갈망, 메스꺼움, 환각, 두통, 식은땀, 떨림, 발작 등을 포함하지만 이에 국한되지는 않는다.

중독에 대해 적극적으로 연구하는 의학 연구자들은 DSM의 중독 분류에 결함이 있으며 자의적인 진단 기준을 포함하고 있다고 비판해 왔다.[30] 2013년 미국 국립정신보건연구소 소장은 DSM-5의 정신질환 분류의 무효성에 대해 다음과 같이 논의하였다.[107]

DSM은 필드의 "Bible"로 설명되어 왔지만, 기껏해야 사전으로 라벨 세트를 만들고 각각을 정의한다. DSM의 각 에디션의 강점은 "신뢰성"이었다. 각 에디션은 임상의사가 동일한 용어를 동일한 방식으로 사용하도록 보장했다. 단점은 타당성 결여다. 허혈성 심장병, 림프종 또는 에이즈에 대한 우리의 정의와 달리 DSM 진단은 객관적인 실험실 측정이 아닌 임상 증상 군집에 대한 일치점에 기초한다. 나머지 의학에서는, 이것은 가슴 통증의 성질이나 열의 질에 근거한 진단 시스템을 만드는 것과 동등할 것이다.

뇌에 대한 구조적 변화에서 중독이 나타난다는 점에서 MRI를 통해 얻은 비침습적 신경영상촬영(non intervirative neuroimizing scan)을 향후 중독 진단에 활용할 가능성도 있다.[108] 진단 바이오마커로서 ΔFosB 표현은 인간의 중독을 진단하는 데 사용될 수 있지만, 이것은 뇌 조직검사를 필요로 하기 때문에 임상 실습에서는 사용되지 않는다.

치료

리뷰에 따르면, "중독에 대한 모든 약리학적 또는 생물학적으로 기반한 치료법을 인지행동치료, 개인 및 집단심리치료, 행동수정전략, 12단계 프로그램, 거주지 치료법 등 다른 확립된 형태의 중독재활에 통합할 필요가 있다.nt 시설"[8]

중독 치료에 대한 생물학적 사회적 접근은 질병과 웰빙의 사회적 결정요인을 전면에 등장시키고 개인의 경험을 위해 존재하는 역동적이고 상호적인 관계를 고려한다.[109]

A.V.의 작품. 슐로저(2018)는 20개월에 걸친 민족학 현장조사를 통해 장기재활 환경에서 약물치료(메타돈, 날트렉손, 부르프레노핀 등)를 받은 여성의 개별 생활경험을 발음하는 것을 목표로 한다. 이 사람 중심의 연구는 이러한 여성들의 경험이 어떻게 "성별, 인종, 계급적 한계화에 기초한 안정된 불평등 시스템에서 어떻게 나타나는지"를 보여준다.[110]

이 렌즈를 통해 중독 치료법을 보는 것 또한 고객 자신의 몸을 '사회적 살점'으로 프레임화하는 것의 중요성을 강조한다. 슐로저(2018년)가 지적하듯 '고객의 몸'은 물론 '자신과 사회적 소속의 경험'이 치료센터의 구조와 시간, 기대 등을 통해 속속 등장하고 있다.[110]

더 많은 도전과 내재된 긴장감은 "치료 중 약물에 진정되었을 때 그들 자신의 신체, 정신, 사회성으로부터 해방되는"[110] 경험 외에, 환자-공급자 관계에 내재된 역학관계의 결과로 발생할 수 있는 잠재력을 가지고 있다.

생명공학은 현재 미래의 중독 치료에서 많은 부분을 차지하고 있다. 몇 가지, 심뇌 자극, 작용제/길항제 이식, 그리고 합텐 결합 백신. 특히 중독 예방접종은 기억력이 중독과 재발의 폐해에 큰 역할을 한다는 믿음과 겹친다. 햅텐 결합 백신은 오피오이드 수용체를 한 영역에서 차단하는 한편 다른 수용체가 정상적으로 활동할 수 있도록 설계됐다. 본질적으로, 일단 외상성 사건과 관련하여 더 이상 높은 수치를 달성할 수 없게 되면, 외상성 기억과의 약물의 관계는 단절되고 치료는 치료에서 역할을 할 수 있다.[111]

행동요법

약물 및 행동 중독 치료를 위한 다양한 행동 요법의 효능에 대한 메타분석적 검토 결과 인지 행동 요법(예: 재발 방지 및 우발적 관리), 동기부여 인터뷰, 지역사회 강화 접근방식이 중간 정도의 효과 크기로 효과적인 중재였다.[112]

임상 및 임상 전 증거는 일관된 유산소 운동, 특히 지구력 운동(예: 마라톤 달리기)이 실제로 특정 약물 중독의 발달을 방해하고 약물 중독, 특히 심령제 중독에 효과적인 보조 치료제라는 것을 나타낸다.[16][113][114][115][116] 에어로빅 운동을 규모에 따라(즉 지속시간과 강도에 따라) 일관되게 하면 약물 중독 위험이 감소하는데, 약물 유발 중독 관련 신경 재생성의 반전을 통해 발생하는 것으로 보인다.[16][114] 한 리뷰는 운동이 선조체나 보상체계의 다른 부분에서 ΔFosB 또는 c-Fos 면역반응을 변화시킴으로써 약물 중독의 발달을 방해할 수 있다는 점에 주목하였다.[116] 유산소 운동은 약물 자기 관리를 줄이고 재발 가능성을 줄이며, 여러 약물 등급에 대한 중독에 의해 유도된 (DRD2 밀도 감소)에 대한 선조체 도파민 수용체 D2(DRD2) 신호 전달(DRD2 밀도 증가)에 대한 반대 효과를 유도한다.[16][114] 결과적으로, 일관된 유산소 운동은 약물 중독에 대한 보조 치료제로 사용될 때 더 나은 치료 결과를 초래할 수 있다.[16][114][115]

약물

알코올 중독

알코올은 오피오이드와 마찬가지로 심각한 신체적 의존 상태를 유도할 수 있으며, 망상증 등의 금단 증상을 유발할 수 있다. 이 때문에 알코올 중독에 대한 치료는 대개 의존성과 중독을 동시에 다루는 결합적 접근법을 수반한다. 벤조디아제핀은 알코올 금단치료에 있어 가장 크고 가장 좋은 증거기반을 가지고 있으며 알코올 해독의 금본위제로 꼽힌다.[117]

알코올 중독에 대한 약리학적 치료법으로는 날트렉손(오피오이드 길항제), 이설피람, 아캄프로세이트, 토피라마이트 등의 약물이 있다.[118][119] 알코올을 대체하기보다는 아캄프로산염과 토피라마이트와 같은 갈망을 직접적으로 줄이거나 이설피람과 같이 알코올을 섭취했을 때 불쾌한 효과를 발생시킴으로써 이러한 약들은 음주에 대한 욕구에 영향을 미치도록 의도되어 있다. 이런 약들은 치료를 유지하면 효과가 있을 수 있지만 알코올 중독자들은 약물 복용을 잊어버리거나 과도한 부작용 때문에 사용을 중단하는 경우가 많아 준수 여부가 문제가 될 수 있다.[120][121] 코크란 콜라보레이션 리뷰에 따르면 오피오이드 길항제 날트렉손은 치료 종료 후 3~12개월의 효과가 지속되는 등 알코올 중독 치료에 효과적인 것으로 나타났다.[122]

행동 중독

행동 중독은 치료 가능한 조건이다. 치료 방법에는 심리치료와 정신의학치료(즉, 약물치료) 또는 둘 다의 조합이 포함된다. 인지행동요법(CBT)은 행동중독을 치료하는 데 사용되는 가장 일반적인 형태의 심리치료로, 강박적인 행동을 유발하는 패턴을 식별하고 더 건강한 행동을 촉진하기 위한 생활습관 변화를 만드는 데 초점을 맞추고 있다. 인지행동요법은 단기요법으로 간주되기 때문에 치료 횟수는 보통 5회에서 20회로 다양하다. 상담 기간 동안 치료사들은 환자들에게 문제를 파악하고, 문제를 둘러싼 자신의 생각을 인식하며, 부정적이거나 거짓된 사고를 식별하고, 부정적이고 거짓된 사고를 재구성하는 주제를 통해 환자를 인도할 것이다. CBT는 행동 중독을 치료하지 않지만, 건강한 방법으로 그 상태에 대처하는 데 도움이 된다. 현재, 행동 중독의 치료를 위해 일반적으로 승인된 약은 없지만, 약물 중독의 치료에 사용되는 일부 약들은 특정한 행동 중독에도 이로운 것일 수 있다.[39][123] 관련 없는 정신 질환은 반드시 통제되어야 하며, 중독을 유발하는 기여 요인과 구별되어야 한다.

카나비노이드 중독

2010년[update] 현재, 캐나비노이드 중독에 대한 효과적인 약리학적 개입은 없다.[124] 2013년 칸나비노이드 중독에 대한 리뷰에서는 β-아레스틴 2 신호와의 상호작용을 감소시킨 CB1 수용체 작용제의 개발이 치료적으로 유용할 수 있다는 점에 주목했다.[125]

니코틴 중독

약물치료가 널리 이용되어 온 또 다른 분야는 니코틴 중독 치료로 니코틴 대체요법, 니코틴 수용체 길항제, 니코틴 수용체 부분작용제 등을 주로 사용한다.[126][127] 니코틴 수용체에 작용하여 니코틴 중독 치료에 이용되어 온 약의 예로는 부프로피온과 부분작용제인 바레니클라인과 같은 길항제들이 있다.[126][127]

오피오이드 중독

오피오이드는 신체적인 의존성을 유발하며, 치료는 일반적으로 의존성과 중독성을 모두 해결한다.

육체적 의존은 수복소나 수부텍스(둘 다 활성 성분인 부프레노핀을 함유한 것)와 메타돈과 같은 대체 약물을 사용하여 치료한다.[128][129] 비록 이러한 약들이 육체적 의존을 영구화하지만, 아편성 유지의 목표는 고통과 갈망 모두를 통제하는 척도를 제공하는 것이다. 대체 약물을 사용하면 중독된 개인의 정상 기능 능력이 향상되고 부정하게 통제된 물질을 획득하는 부정적인 결과를 없앨 수 있다. 정해진 복용량이 안정되면 치료는 유지보수와 테이퍼링 단계로 들어간다. 미국에서는 아편산염 대체 요법이 메타돈 클리닉과 DATA 2000 법률에 따라 엄격하게 규제되고 있다. 일부 국가에서는 디히드로코딘,[130] 디히드로에토폴핀[131], 심지어 헤로인과[132][133] 같은 다른 오피오이드 유도체들이 불법적인 거리 오피스의 대체 약물로 사용되고 있으며, 개별 환자의 필요에 따라 다른 처방들이 주어진다. 바클로펜은 각성제, 알코올, 오피오이드에 대한 갈망을 성공적으로 감소시켰고 알코올 금단 증후군을 완화시켰다. 많은 환자들은 바클로펜 치료를 시작한 지 하루 만에 "술에 무관심하다"거나 "코카인과 구별되지 않는다"고 말했다.[134] 일부 연구는 오피오이드 약물 해독과 과다복용 사망률의 상호 연관성을 보여준다.[135]

정신안정제 중독

2014년[update] 5월 현재, 어떤 형태의 정신 자극제 중독에도 효과적인 약리 요법이 없다.[8][136][137][138] 2015년, 2016년, 2018년 검토 결과 TAAR1 선택적 작용제는 심리 자극제 중독 치료제로서 상당한 치료 잠재력을 가지고 있는 것으로 나타났으나,[139][140][141] 2018년[update] 현재 TAAR1 선택적 작용제로서 기능하는 것으로 알려진 화합물은 실험용 약물뿐이다.[139][140][141]

리서치

이 구간은 확장이 필요하다. 추가하면 도움이 된다. (2016년 4월 |

연구에 따르면, 항마약 단핵 항체를 이용하는 백신은 약물이 혈액-뇌 장벽을 넘어 이동하는 것을 방지함으로써 약물에 의한 양성 강화 효과를 완화할 수 있다.[142] 그러나, 현재의 백신 기반 치료법은 상대적으로 적은 수의 개인에게만 효과적이다.[142][143] 2015년[update] 11월 현재 니코틴, 코카인, 필로폰 등 약물 과다복용에 대한 중독 치료와 예방책으로 백신 기반 치료제가 인체 임상시험에서 시험되고 있다.[142]

새로운 연구는 백신이 약물 과다 복용으로 생명을 구할 수도 있다는 것을 보여준다. 이 경우 오피오이드가 뇌에 접근하지 못하도록 몸이 항체를 빠르게 만들어 백신에 반응한다는 생각이다.[144]

중독은 글루탐산염과 GABAergic 신경전달의 이상을 수반하기 때문에 이러한 신경전달물질과 관련된 수용체(예: AMPA 수용체, NMDA 수용체, GABAB 수용체)는 중독의 잠재적 치료 대상이다.[145][146][145][146][147][148] 메타보틱성 글루탐산염 수용체와 NMDA 수용체에 영향을 미치는 N-acetylcysteine은 코카인, 헤로인,[145] 카나비노이드에 대한 중독과 관련된 임상 전 연구들에서 어느 정도 효익을 보였다. 암페타민 타입의 각성제 중독에 대한 보조요법으로도 유용할 수 있지만, 더 많은 임상 연구가 필요하다.[145]

현재 실험동물을 대상으로 한 연구에 대한 의학적 리뷰에서는 장기간 사용 후 측핵에 G9a 발현을 유도하여 간접적으로 기능을 억제하고 점액 ΔFosB의 발현이 더욱 증가하는 약물 등급(클래스 1 히스톤 디아세틸라제 억제제[note 7])을 확인하였다.[17][81][149][104] 이러한 검토와 장기간 낙산이나 기타 강좌 1세 HDAC 산화 방지제의 나트륨 소금의 경구 투여 또는 복강 내투여 사용 이후의 전초적인 증거를 이 약품 실험실 animals[노트 8]에서 중독, 미친 놈들 조사. 에탄올을 개발했다 중독 행동을 줄이는데 효과 한다.timulants(즉, 암페타민 및 코카인), 니코틴 및 아편제.[81][104][150][151] 그러나 중독을 가진 사람과 HDAC 등급 I 억제제를 포함하는 임상시험은 거의 실시되지 않아 인간 내 치료 효능을 시험하거나 최적의 복용법을 찾아냈다.[note 9]

중독에 대한 유전자 치료는 연구의 활발한 영역이다. 유전자 치료 연구의 한 라인은 뇌에서 도파민 D2 수용체 단백질의 발현을 증가시키기 위해 바이러스 벡터를 사용하는 것을 포함한다.[153][154][155][156][157]

역학

문화적 다양성으로 인해 특정 기간 내에 약물이나 행동 중독을 일으키는 개인(즉, 유병률)의 비율은 시간에 따라, 국가별로, 그리고 국가별 인구통계(예: 연령대별, 사회경제적 지위 등)에 따라 달라진다.[40]

아시아

알코올 의존도의 유행이 다른 지역에서 볼 수 있는 것만큼 높지 않다. 아시아에서는 사회경제적 요소뿐만 아니라 생물학적 요소도 음주행위에 영향을 미친다.[158]

전체 스마트폰 보유 유병률은 62%로 중국 41%에서 국내 84%에 이른다. 게다가 온라인 게임 참여율은 중국 11%에서 일본 39%까지 다양하다. 홍콩은 일별 청소년 신고건수 또는 인터넷 이용건수 이상(68%)이 가장 많다. 인터넷 중독 테스트(IAT) – 5%와 CIAS-R (Revised Chen Internet 중독 척도) – 21%[159]에 따르면, 인터넷 중독 장애는 필리핀에서 가장 높다.

호주.

호주인들의 약물 남용 장애 유병률은 2009년에 5.1%로 보고되었다.[160]

유럽

2015년 성인 인구 추정 유병률은 중증 알코올 사용(지난 30일) 18.4%, 일일 흡연 15.2%, 2017년 대마초, 암페타민, 오피오이드, 코카인 사용 3.8, 0.77, 0.37, 0.35%로 나타났다. 알코올과 불법 약물의 사망률은 동유럽에서 가장 높았다.[161]

미국

2011년 미국 청소년 인구의 대표적인 표본을 바탕으로 알코올 중독과 불법 약물 중독의 평생 유병률은[note 10] 각각 약 8%, 2~3%로 추정되고 있다.[20] 2011년 미국 성인 인구의 대표적인 표본을 바탕으로, 알코올과 불법 약물 중독의 12개월 유병률은 각각 12%와 2~3%로 추정되었다.[20] 처방약 중독의 평생 유병률은 현재 약 [162]4.7%이다.

2016년 현재,[update] 미국의 약 2200만 명의 사람들이 알코올, 니코틴 또는 다른 약물에 중독되어 치료를 필요로 한다.[21][163] 단지 약 10% 혹은 200만 조금 넘는 사람들만이 어떤 형태의 치료도 받을 수 있으며, 일반적으로 그렇지 않은 사람들은 증거에 근거한 치료를 받지 않는다.[21][163] 매년 미국에서 발생하는 입원 병원비의 3분의 1과 전체 사망자의 20%는 치료되지 않은 중독과 위험한 물질 사용의 결과물이다.[21][163] 당뇨병과 모든 형태의 암을 합친 비용보다 더 큰 사회 전반의 막대한 경제적 비용에도 불구하고, 미국의 대부분의 의사들은 약물 중독을 효과적으로 해결하기 위한 훈련이 부족하다.[21][163]

또 다른 리뷰에는 미국의 몇몇 행동 중독자들의 평생 유병률 추정치가 나열되었는데, 여기에는 강박성 도박의 1~2%, 성 중독의 5%, 음식 중독의 2.8%, 그리고 강박 쇼핑의 5-6%가 포함된다.[16] 체계적 검토 결과 미국 내 성중독 및 관련 강박적 성행위(예: 음란물 유무, 강박적 사이버성 등)의 시간불변 유병률이 인구의 3~6%에 이르는 것으로 나타났다.[34]

퓨 리서치 센터가 실시한 2017년 여론조사에 따르면 미국 성인의 거의 절반은 가족이나 가까운 친구를 알고 있으며, 가족이나 친한 친구는 평생 어느 시점에 약물 중독으로 고생한 적이 있다고 한다.[164]

2019년에는 오피오이드 중독이 미국에서 국가적인 위기로 인식되었다.[165] 워싱턴포스트(WP)의 한 기사는 "미국 최대 제약회사들이 중독과 과다 복용을 부추기는 것이 명백해진 2006년부터 2012년까지 미국에 진통제를 퍼부었다"고 전했다.

남아메리카

라틴 아메리카에서 오피오이드 사용과 남용의 현실은 관찰이 역학 조사로 제한된다면 기만적일 수 있다. 유엔 마약범죄국(United Office on Drug and Crime) 보고서에서 남미산 모르핀과 헤로인의 3%와 아편의 0.01%를 생산했지만 사용 유행이 고르지 않다.[166] 미국간 마약 남용 통제 위원회에 따르면, 콜롬비아는 이 지역에서 가장 큰 아편 생산국임에도 불구하고 대부분의 중남미 국가에서 헤로인 소비는 저조하다. 멕시코는 미국과의 국경 때문에 사용 빈도가 가장 높다.[167]

인성 이론

중독에 대한 성격 이론은 성격 특성이나 사고방식(즉, 감정 상태)을 중독에 대한 개인의 성향과 연관시키는 심리학적 모델이다. 데이터 분석은 약물 사용자와 비사용자의 심리학적 프로파일에 상당한 차이가 있으며 다른 약물을 사용하는 심리학적 성향은 다를 수 있다는 것을 보여준다.[168] 심리학 문헌에서 제안된 중독 위험 모델에는 긍정적이고 부정적인 심리적 영향의 영향 조절 오류 모델, 충동성 및 행동 억제의 강화 민감성 이론 모델, 보상 민감성 및 충동성의 충동성 모델이 포함된다.[169][170][171][172][173]

접미사 "-holic"과 "-holism"

현대 현대 영어에서 "-holic"은 그것에 대한 중독을 나타내는 주제에 첨가될 수 있는 접미사다. 알콜중독(의학적으로나 사회적으로 널리 식별된 최초의 중독자 중의 하나)이라는 단어에서 추출한 것이다(정확히 뿌리 "wikt:alco"와 접미사 "-ism"을 "alco"과 "-holism"으로 잘못 나누거나 다시 붙임으로써). (또 다른 오분류는 "헬리콥터"를 "헬리콥터"로 해석하고 있다."helico-pter"를 수정하여 " "port"와 "jetcopter"와 같은 파생어를 발생시킨다.[174] 이러한 중독에 대한 올바른 의료법적 용어들이 있다: 디포매니아는 알코올 중독에 대한 의료법적 용어다.[175] 다른 예는 이 표에 있다.

"홀리즘"이라는 용어는 받아들여지는 의학용어는 아니지만 상당히 두드러진 신조어다. 이와 같이 널리 쓰임에도 불구하고 형식적인 정의가 결여되어 있다. 이 용어는 신체적 또는 심리적 의존을 묘사하는 것에서부터 어떤 것을[176][177] 강박적으로 하는 경향(예: 일 중독,[178] 쇼핑 중독[179])에 이르기까지 다양한 방법으로 사용될 수 있다. '-홀리즘'은 어떤 것에 대한 강한 열정이나 관심을 표현하기 위해 누군가에 의해서도 사용될 수 있다. 예를 들어, 프로레슬러인 크리스 제리코는 그의 팬들을 예리콜릭스로 지칭할 것이다.[180]

참고 항목

메모들

- ^ 위로 이동: 혐오 민감성이 감소한다는 것은 간단히 말해서 개인의 행동이 바람직하지 않은 결과에 의해 영향을 받을 가능성이 적다는 것을 의미한다.

- ^ 중독에서 발생하는 후생유전학적 마크의 전세대 후생유전유전을 조사한 실험동물 모델에 대한 검토에 따르면, 히스톤 아세틸화의 변경 - 구체적으로는 히스톤 3(즉, H3K9ac2 및 H3K14ac2)에 대한 리신잔류 9 및 14의 디아세틸화가 BDNF 유전자 발기인 -과 연계된 것으로 나타났다. 코카인에 중독된 수컷 쥐의 mPFC, 고환, 정자 내에서 발생한다.[40] 랫드 mPFC의 이러한 후생유전적 변화는 mPFC 내에서 BDNF 유전자 발현을 증가시켜 결과적으로 코카인의 보상 특성을 흐리게 하고 코카인 자가 관리를 감소시킨다.[40] 이러한 코카인 노출 쥐의 수컷은 아니지만 암컷은 mPFC 뉴런 내에서 후생유전학적 마크(즉, 리신 잔류물 9와 히스톤 3에 대한 14의 디아세틸화), mPFC 뉴런 내에서의 상응하는 BDNF 표현 증가, 그리고 이러한 효과와 관련된 행동 표현 유형(즉 코카인 보상 감소, resu)을 모두 물려받았다.이러한 수컷 자손을 통해 코카인을 추적하는 감소된 양을 섭취하는 것).[40] 결과적으로, 수컷 아빠에서 수컷 자손으로 쥐를 통해 이러한 두 개의 코카인에 의한 후생유전적 변화(즉, H3K9ac2 및 H3K14ac2)를 전송하는 것은 자손이 코카인에 중독될 위험을 줄이는 데 도움이 되었다.[40] 2018년 현재,[update] 인간에서 이러한 후생유전학적 마크의 유전성이나 인간 mPFC 뉴런 내의 마크의 행동적 영향도 확립되지 않았다.[40]

- ^ 즉 c-Fos 억제는 이 상태에서 선택적으로 유도되기 때문에 ΔFosB가 접근하는 핵의 D1형 중간 가시가 있는 신경세포 내에 더 빠르게 축적될 수 있게 한다.[3] c-Fos 억제 전에는 모든 Fos 계열 단백질(예: c-Fos, Fra1, Fra2, FosB, ΔFosB)이 함께 유도되며 ΔFosB 표현은 이보다 적게 증가한다.[3]

- ^ 두 가지 의학적 검토에 따르면 ΔFosB는 다른 연구에서 다이노핀 발현 증가와 감소를 모두 유발하는 데 관여했다.[15][98] 이 표 항목은 감소만을 반영한다.

- ^ 보상에 대한 "동기적 쾌감"인 인센티브는 "욕망" 또는 "욕망" 속성으로, 뇌가 보상적 자극에 할당하는 동기적 요소를 포함한다.[99][100] 그 결과, 인센티브 만족도는 주의를 명령하고 접근을 유도하며 보람 있는 자극을 찾도록 하는 보람 있는 자극에 대한 동기부여 "마그넷" 역할을 한다.[99]

- ^ 간단히 말해서, 이것은 암페타민이나 성별 중 하나가 보상 감작화를 통해 더 매력적이거나 바람직한 것으로 인식될 때, 다른 쪽에서도 이러한 영향이 발생한다는 것을 의미한다.

- ^ 클래스의 나는deacetylase(HDAC)효소 histone Inhibitors.HDAC 억제제를 동물의 대부분의 연구 4약:뷰티 레이트염(주로 나트륨 butyrate)으로, A, 밸프로산, SAHA trichostatin,[149][104]낙산은 na이 시행되는 4개 세부 histone-modifying 효소:HDAC1, HDAC2, HDAC3, HDAC8을 억제하는 약이 있습니다.turally oc인간의 단사슬 지방산을 억제하는 반면, 후자의 두 화합물은 FDA가 승인한 약품이며 중독과 무관한 의학적인 징후가 있다.

- ^ 구체적으로는 클래스 I HDAC 억제제를 장기간 투여하면 다른 보상을 획득하려는 동물의 동기(즉, 동기부여 무쾌감증을 유발하지 않는 것처럼 보이지 않음)에 영향을 주지 않고 중독성 약물을 획득하여 사용하려는 동물의 동기가 감소하고, 쉽게 아바가 될 때 자가 투여되는 약의 양이 감소하는 것으로 보인다.살 수 [81][104][150]있는

- ^ 등급 I HDAC 억제제를 채택한 몇 안 되는 임상시험 가운데 발프로이트를 필로폰 중독에 활용한 임상시험도 있었다.[152]

- ^ 평생 동안 중독이 만연하는 것은 인구에서 개인의 삶의 어느 시점에 중독이 발병한 비율이다.

- 이미지 범례

참조

- ^ 위로 이동: "Facing Addiction in America: The Surgeon General's Report on Alcohol, Drugs, and Health" (PDF). Office of the Surgeon General. US Department of Health and Human Services. November 2016. pp. 35–37, 45, 63, 155, 317, 338. Retrieved 28 January 2017.

- ^ 위로 이동: Volkow ND, Koob GF, McLellan AT (January 2016). "Neurobiologic Advances from the Brain Disease Model of Addiction". New England Journal of Medicine. 374 (4): 363–371. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1511480. PMC 6135257. PMID 26816013.

Substance-use disorder: A diagnostic term in the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) referring to recurrent use of alcohol or other drugs that causes clinically and functionally significant impairment, such as health problems, disability, and failure to meet major responsibilities at work, school, or home. Depending on the level of severity, this disorder is classified as mild, moderate, or severe.

Addiction: A term used to indicate the most severe, chronic stage of substance-use disorder, in which there is a substantial loss of self-control, as indicated by compulsive drug taking despite the desire to stop taking the drug. In the DSM-5, the term addiction is synonymous with the classification of severe substance-use disorder. - ^ 위로 이동: Nestler EJ (December 2013). "Cellular basis of memory for addiction". Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 15 (4): 431–443. PMC 3898681. PMID 24459410.

Despite the importance of numerous psychosocial factors, at its core, drug addiction involves a biological process: the ability of repeated exposure to a drug of abuse to induce changes in a vulnerable brain that drive the compulsive seeking and taking of drugs, and loss of control over drug use, that define a state of addiction. ... A large body of literature has demonstrated that such ΔFosB induction in D1-type [nucleus accumbens] neurons increases an animal's sensitivity to drug as well as natural rewards and promotes drug self-administration, presumably through a process of positive reinforcement ... Another ΔFosB target is cFos: as ΔFosB accumulates with repeated drug exposure it represses c-Fos and contributes to the molecular switch whereby ΔFosB is selectively induced in the chronic drug-treated state.41 ... Moreover, there is increasing evidence that, despite a range of genetic risks for addiction across the population, exposure to sufficiently high doses of a drug for long periods of time can transform someone who has relatively lower genetic loading into an addict.

- ^ Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). "Chapter 15: Reinforcement and Addictive Disorders". In Sydor A, Brown RY (eds.). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. pp. 364–375. ISBN 9780071481274.

- ^ 위로 이동: "Glossary of Terms". Mount Sinai School of Medicine. Department of Neuroscience. Retrieved 9 February 2015.

- ^ Angres DH, Bettinardi-Angres K (October 2008). "The disease of addiction: origins, treatment, and recovery". Disease-a-Month. 54 (10): 696–721. doi:10.1016/j.disamonth.2008.07.002. PMID 18790142.

- ^ 위로 이동: Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). "Chapter 15: Reinforcement and Addictive Disorders". In Sydor A, Brown RY (eds.). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. pp. 364–65, 375. ISBN 978-0-07-148127-4.

The defining feature of addiction is compulsive, out-of-control drug use, despite negative consequences. ...

compulsive eating, shopping, gambling, and sex – so-called "natural addictions" – Indeed, addiction to both drugs and behavioral rewards may arise from similar dysregulation of the mesolimbic dopamine system. - ^ 위로 이동: Taylor SB, Lewis CR, Olive MF (February 2013). "The neurocircuitry of illicit psychostimulant addiction: acute and chronic effects in humans". Subst. Abuse Rehabil. 4: 29–43. doi:10.2147/SAR.S39684. PMC 3931688. PMID 24648786.

Initial drug use can be attributed to the ability of the drug to act as a reward (ie, a pleasurable emotional state or positive reinforcer), which can lead to repeated drug use and dependence.8,9 A great deal of research has focused on the molecular and neuroanatomical mechanisms of the initial rewarding or reinforcing effect of drugs of abuse. ... At present, no pharmacological therapy has been approved by the FDA to treat psychostimulant addiction. Many drugs have been tested, but none have shown conclusive efficacy with tolerable side effects in humans.172 ... A new emphasis on larger-scale biomarker, genetic, and epigenetic research focused on the molecular targets of mental disorders has been recently advocated.212 In addition, the integration of cognitive and behavioral modification of circuit-wide neuroplasticity (ie, computer-based training to enhance executive function) may prove to be an effective adjunct-treatment approach for addiction, particularly when combined with cognitive enhancers.198,213–216 Furthermore, in order to be effective, all pharmacological or biologically based treatments for addiction need to be integrated into other established forms of addiction rehabilitation, such as cognitive behavioral therapy, individual and group psychotherapy, behavior-modification strategies, twelve-step programs, and residential treatment facilities.

- ^ Hammer R, Dingel M, Ostergren J, Partridge B, McCormick J, Koenig BA (1 July 2013). "Addiction: Current Criticism of the Brain Disease Paradigm". AJOB Neuroscience. 4 (3): 27–32. doi:10.1080/21507740.2013.796328. PMC 3969751. PMID 24693488.

- ^ Heather N, Best D, Kawalek A, Field M, Lewis M, Rotgers F, Wiers RW, Heim D (4 July 2018). "Challenging the brain disease model of addiction: European launch of the addiction theory network". Addiction Research & Theory. 26 (4): 249–255. doi:10.1080/16066359.2017.1399659.

- ^ Heather N (1 April 2017). "Q: Is Addiction a Brain Disease or a Moral Failing? A: Neither". Neuroethics. 10 (1): 115–124. doi:10.1007/s12152-016-9289-0. PMC 5486515. PMID 28725283.

- ^ Satel S, Lilienfeld SO (2014). "Addiction and the brain-disease fallacy". Frontiers in Psychiatry. 4: 141. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2013.00141. PMC 3939769. PMID 24624096.

- ^ Peele S (December 2016). "People Control Their Addictions: No matter how much the "chronic" brain disease model of addiction indicates otherwise, we know that people can quit addictions - with special reference to harm reduction and mindfulness". Addictive Behaviors Reports. 4: 97–101. doi:10.1016/j.abrep.2016.05.003. PMC 5836519. PMID 29511729.

- ^ Henden E (2017). "Addiction, Compulsion, and Weakness of the Will: A Dual-Process Perspective.". In Heather N, Gabriel S (eds.). Addiction and Choice: Rethinking the Relationship. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. pp. 116–132.

- ^ 위로 이동: Ruffle JK (November 2014). "Molecular neurobiology of addiction: what's all the (Δ)FosB about?". Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse. 40 (6): 428–37. doi:10.3109/00952990.2014.933840. PMID 25083822. S2CID 19157711.

The strong correlation between chronic drug exposure and ΔFosB provides novel opportunities for targeted therapies in addiction (118), and suggests methods to analyze their efficacy (119). Over the past two decades, research has progressed from identifying ΔFosB induction to investigating its subsequent action (38). It is likely that ΔFosB research will now progress into a new era – the use of ΔFosB as a biomarker. ...

Conclusions

ΔFosB is an essential transcription factor implicated in the molecular and behavioral pathways of addiction following repeated drug exposure. The formation of ΔFosB in multiple brain regions, and the molecular pathway leading to the formation of AP-1 complexes is well understood. The establishment of a functional purpose for ΔFosB has allowed further determination as to some of the key aspects of its molecular cascades, involving effectors such as GluR2 (87,88), Cdk5 (93) and NFkB (100). Moreover, many of these molecular changes identified are now directly linked to the structural, physiological and behavioral changes observed following chronic drug exposure (60,95,97,102). New frontiers of research investigating the molecular roles of ΔFosB have been opened by epigenetic studies, and recent advances have illustrated the role of ΔFosB acting on DNA and histones, truly as a molecular switch (34). As a consequence of our improved understanding of ΔFosB in addiction, it is possible to evaluate the addictive potential of current medications (119), as well as use it as a biomarker for assessing the efficacy of therapeutic interventions (121,122,124). Some of these proposed interventions have limitations (125) or are in their infancy (75). However, it is hoped that some of these preliminary findings may lead to innovative treatments, which are much needed in addiction. - ^ 위로 이동: Olsen CM (December 2011). "Natural rewards, neuroplasticity, and non-drug addictions". Neuropharmacology. 61 (7): 1109–22. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.03.010. PMC 3139704. PMID 21459101.

Functional neuroimaging studies in humans have shown that gambling (Breiter et al, 2001), shopping (Knutson et al, 2007), orgasm (Komisaruk et al, 2004), playing video games (Koepp et al, 1998; Hoeft et al, 2008) and the sight of appetizing food (Wang et al, 2004a) activate many of the same brain regions (i.e., the mesocorticolimbic system and extended amygdala) as drugs of abuse (Volkow et al, 2004). ... Cross-sensitization is also bidirectional, as a history of amphetamine administration facilitates sexual behavior and enhances the associated increase in NAc DA ... As described for food reward, sexual experience can also lead to activation of plasticity-related signaling cascades. The transcription factor delta FosB is increased in the NAc, PFC, dorsal striatum, and VTA following repeated sexual behavior (Wallace et al., 2008; Pitchers et al., 2010b). This natural increase in delta FosB or viral overexpression of delta FosB within the NAc modulates sexual performance, and NAc blockade of delta FosB attenuates this behavior (Hedges et al, 2009; Pitchers et al., 2010b). Further, viral overexpression of delta FosB enhances the conditioned place preference for an environment paired with sexual experience (Hedges et al., 2009). ... In some people, there is a transition from "normal" to compulsive engagement in natural rewards (such as food or sex), a condition that some have termed behavioral or non-drug addictions (Holden, 2001; Grant et al., 2006a). ... In humans, the role of dopamine signaling in incentive-sensitization processes has recently been highlighted by the observation of a dopamine dysregulation syndrome in some patients taking dopaminergic drugs. This syndrome is characterized by a medication-induced increase in (or compulsive) engagement in non-drug rewards such as gambling, shopping, or sex (Evans et al, 2006; Aiken, 2007; Lader, 2008)."

표 1: 약물 또는 자연 보강제에 노출된 후 관찰된 가소성 요약" - ^ 위로 이동: Biliński P, Wojtyła A, Kapka-Skrzypczak L, Chwedorowicz R, Cyranka M, Studziński T (2012). "Epigenetic regulation in drug addiction". Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 19 (3): 491–96. PMID 23020045.

For these reasons, ΔFosB is considered a primary and causative transcription factor in creating new neural connections in the reward centre, prefrontal cortex, and other regions of the limbic system. This is reflected in the increased, stable and long-lasting level of sensitivity to cocaine and other drugs, and tendency to relapse even after long periods of abstinence. These newly constructed networks function very efficiently via new pathways as soon as drugs of abuse are further taken ... In this way, the induction of CDK5 gene expression occurs together with suppression of the G9A gene coding for dimethyltransferase acting on the histone H3. A feedback mechanism can be observed in the regulation of these 2 crucial factors that determine the adaptive epigenetic response to cocaine. This depends on ΔFosB inhibiting G9a gene expression, i.e. H3K9me2 synthesis which in turn inhibits transcription factors for ΔFosB. For this reason, the observed hyper-expression of G9a, which ensures high levels of the dimethylated form of histone H3, eliminates the neuronal structural and plasticity effects caused by cocaine by means of this feedback which blocks ΔFosB transcription

- ^ 위로 이동: Robison AJ, Nestler EJ (November 2011). "Transcriptional and epigenetic mechanisms of addiction". Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 12 (11): 623–37. doi:10.1038/nrn3111. PMC 3272277. PMID 21989194.

ΔFosB has been linked directly to several addiction-related behaviors ... Importantly, genetic or viral overexpression of ΔJunD, a dominant negative mutant of JunD which antagonizes ΔFosB- and other AP-1-mediated transcriptional activity, in the NAc or OFC blocks these key effects of drug exposure14,22–24. This indicates that ΔFosB is both necessary and sufficient for many of the changes wrought in the brain by chronic drug exposure. ΔFosB is also induced in D1-type NAc MSNs by chronic consumption of several natural rewards, including sucrose, high fat food, sex, wheel running, where it promotes that consumption14,26–30. This implicates ΔFosB in the regulation of natural rewards under normal conditions and perhaps during pathological addictive-like states.

- ^ 위로 이동: Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). "Chapter 1: Basic Principles of Neuropharmacology". In Sydor A, Brown RY (eds.). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-07-148127-4.

Drug abuse and addiction exact an astoundingly high financial and human toll on society through direct adverse effects, such as lung cancer and hepatic cirrhosis, and indirect adverse effects –for example, accidents and AIDS – on health and productivity.

- ^ 위로 이동: Merikangas KR, McClair VL (June 2012). "Epidemiology of Substance Use Disorders". Hum. Genet. 131 (6): 779–89. doi:10.1007/s00439-012-1168-0. PMC 4408274. PMID 22543841.

- ^ 위로 이동: "American Board of Medical Specialties recognizes the new subspecialty of addiction medicine" (PDF). American Board of Addiction Medicine. 14 March 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 March 2021. Retrieved 3 April 2016.

Sixteen percent of the non-institutionalized U.S. population age 12 and over – more than 40 million Americans – meets medical criteria for addiction involving nicotine, alcohol or other drugs. This is more than the number of Americans with cancer, diabetes or heart conditions. In 2014, 22.5 million people in the United States needed treatment for addiction involving alcohol or drugs other than nicotine, but only 11.6 percent received any form of inpatient, residential, or outpatient treatment. Of those who do receive treatment, few receive evidence-based care. (There is no information available on how many individuals receive treatment for addiction involving nicotine.)

Risky substance use and untreated addiction account for one-third of inpatient hospital costs and 20 percent of all deaths in the United States each year, and cause or contribute to more than 100 other conditions requiring medical care, as well as vehicular crashes, other fatal and non-fatal injuries, overdose deaths, suicides, homicides, domestic discord, the highest incarceration rate in the world and many other costly social consequences. The economic cost to society is greater than the cost of diabetes and all cancers combined. Despite these startling statistics on the prevalence and costs of addiction, few physicians have been trained to prevent or treat it. - ^ "Economic consequences of drug abuse" (PDF). International Narcotics Control Board Report: 2013 (PDF). United Nations – International Narcotics Control Board. 2013. ISBN 978-92-1-148274-4. Retrieved 28 September 2018.

- ^ Morse RM, Flavin DK (August 1992). "The definition of alcoholism. The Joint Committee of the National Council on Alcoholism and Drug Dependence and the American Society of Addiction Medicine to Study the Definition and Criteria for the Diagnosis of Alcoholism". JAMA. 268 (8): 1012–14. doi:10.1001/jama.1992.03490080086030. PMID 1501306.

- ^ Marlatt GA, Baer JS, Donovan DM, Kivlahan DR (1988). "Addictive behaviors: etiology and treatment". Annu Rev Psychol. 39: 223–52. doi:10.1146/annurev.ps.39.020188.001255. PMID 3278676.

- ^ 위로 이동: Rosenthal, Richard; Faris, Suzanne (2019). "The etymology and early history of 'addiction'". Addiction Research & Theory. 27 (5): 437. doi:10.1080/16066359.2018.1543412. S2CID 150418396.

- ^ Institute of Medicine (1996). Pathways of Addiction: Opportunities in Drug Abuse Research. Washington: National Academies Press.

- ^ Bettinardi-Angres, Kathy; Angres, Daniel (2015). "Understanding the Disease of Addiction". Journal of Nursing Regulation. 1 (2): 31–37. doi:10.1016/S2155-8256(15)30348-3.

- ^ ME (12 September 2019). "Gaming Addiction in ICD-11: Issues and Implications". Psychiatric Times. Retrieved 3 March 2020.

- ^ 위로 이동: American Psychiatric Association (2013). "Substance-Related and Addictive Disorders" (PDF). American Psychiatric Publishing. pp. 1–2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 August 2015. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

Additionally, the diagnosis of dependence caused much confusion. Most people link dependence with "addiction" when in fact dependence can be a normal body response to a substance.

- ^ 위로 이동: Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE, Holtzman DM (2015). "Chapter 16: Reinforcement and Addictive Disorders". Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (3rd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. ISBN 978-0-07-182770-6.

The official diagnosis of drug addiction by the Diagnostic and Statistic Manual of Mental Disorders (2013), which uses the term substance use disorder, is flawed. Criteria used to make the diagnosis of substance use disorders include tolerance and somatic dependence/withdrawal, even though these processes are not integral to addiction as noted. It is ironic and unfortunate that the manual still avoids use of the term addiction as an official diagnosis, even though addiction provides the best description of the clinical syndrome.

- ^ Washburn DA (2016). "The Stroop effect at 80: The competition between stimulus control and cognitive control". J Exp Anal Behav. 105 (1): 3–13. doi:10.1002/jeab.194. PMID 26781048.

Today, arguably more than at any time in history, the constructs of attention, executive functioning, and cognitive control seem to be pervasive and preeminent in research and theory. Even within the cognitive framework, however, there has long been an understanding that behavior is multiply determined, and that many responses are relatively automatic, unattended, contention-scheduled, and habitual. Indeed, the cognitive flexibility, response inhibition, and self-regulation that appear to be hallmarks of cognitive control are noteworthy only in contrast to responses that are relatively rigid, associative, and involuntary.

- ^ Diamond A (2013). "Executive functions". Annu Rev Psychol. 64: 135–68. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143750. PMC 4084861. PMID 23020641.

Core EFs are inhibition [response inhibition (self-control – resisting temptations and resisting acting impulsively) and interference control (selective attention and cognitive inhibition)], working memory, and cognitive flexibility (including creatively thinking "outside the box," seeing anything from different perspectives, and quickly and flexibly adapting to changed circumstances). ... EFs and prefrontal cortex are the first to suffer, and suffer disproportionately, if something is not right in your life. They suffer first, and most, if you are stressed (Arnsten 1998, Liston et al. 2009, Oaten & Cheng 2005), sad (Hirt et al. 2008, von Hecker & Meiser 2005), lonely (Baumeister et al. 2002, Cacioppo & Patrick 2008, Campbell et al. 2006, Tun et al. 2012), sleep deprived (Barnes et al. 2012, Huang et al. 2007), or not physically fit (Best 2010, Chaddock et al. 2011, Hillman et al. 2008). Any of these can cause you to appear to have a disorder of EFs, such as ADHD, when you do not. You can see the deleterious effects of stress, sadness, loneliness, and lack of physical health or fitness at the physiological and neuroanatomical level in prefrontal cortex and at the behavioral level in worse EFs (poorer reasoning and problem solving, forgetting things, and impaired ability to exercise discipline and self-control). ...

EFs can be improved (Diamond & Lee 2011, Klingberg 2010). ... At any age across the life cycle EFs can be improved, including in the elderly and in infants. There has been much work with excellent results on improving EFs in the elderly by improving physical fitness (Erickson & Kramer 2009, Voss et al. 2011) ... Inhibitory control (one of the core EFs) involves being able to control one's attention, behavior, thoughts, and/or emotions to override a strong internal predisposition or external lure, and instead do what's more appropriate or needed. Without inhibitory control we would be at the mercy of impulses, old habits of thought or action (conditioned responses), and/or stimuli in the environment that pull us this way or that. Thus, inhibitory control makes it possible for us to change and for us to choose how we react and how we behave rather than being unthinking creatures of habit. It doesn’t make it easy. Indeed, we usually are creatures of habit and our behavior is under the control of environmental stimuli far more than we usually realize, but having the ability to exercise inhibitory control creates the possibility of change and choice. ... The subthalamic nucleus appears to play a critical role in preventing such impulsive or premature responding (Frank 2006). - ^ 위로 이동: Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). "Chapter 13: Higher Cognitive Function and Behavioral Control". In Sydor A, Brown RY (eds.). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. pp. 313–21. ISBN 978-0-07-148127-4.

• Executive function, the cognitive control of behavior, depends on the prefrontal cortex, which is highly developed in higher primates and especially humans.

• Working memory is a short-term, capacity-limited cognitive buffer that stores information and permits its manipulation to guide decision-making and behavior. ...

These diverse inputs and back projections to both cortical and subcortical structures put the prefrontal cortex in a position to exert what is often called "top-down" control or cognitive control of behavior. ... The prefrontal cortex receives inputs not only from other cortical regions, including association cortex, but also, via the thalamus, inputs from subcortical structures subserving emotion and motivation, such as the amygdala (Chapter 14) and ventral striatum (or nucleus accumbens; Chapter 15). ...

In conditions in which prepotent responses tend to dominate behavior, such as in drug addiction, where drug cues can elicit drug seeking (Chapter 15), or in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD; described below), significant negative consequences can result. ... ADHD can be conceptualized as a disorder of executive function; specifically, ADHD is characterized by reduced ability to exert and maintain cognitive control of behavior. Compared with healthy individuals, those with ADHD have diminished ability to suppress inappropriate prepotent responses to stimuli (impaired response inhibition) and diminished ability to inhibit responses to irrelevant stimuli (impaired interference suppression). ... Functional neuroimaging in humans demonstrates activation of the prefrontal cortex and caudate nucleus (part of the striatum) in tasks that demand inhibitory control of behavior. Subjects with ADHD exhibit less activation of the medial prefrontal cortex than healthy controls even when they succeed in such tasks and utilize different circuits. ... Early results with structural MRI show thinning of the cerebral cortex in ADHD subjects compared with age-matched controls in prefrontal cortex and posterior parietal cortex, areas involved in working memory and attention. - ^ 위로 이동: Karila L, Wéry A, Weinstein A, Cottencin O, Petit A, Reynaud M, Billieux J (2014). "Sexual addiction or hypersexual disorder: different terms for the same problem? A review of the literature". Curr. Pharm. Des. 20 (25): 4012–20. doi:10.2174/13816128113199990619. PMID 24001295.

Sexual addiction, which is also known as hypersexual disorder, has largely been ignored by psychiatrists, even though the condition causes serious psychosocial problems for many people. A lack of empirical evidence on sexual addiction is the result of the disease's complete absence from versions of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. ... Existing prevalence rates of sexual addiction-related disorders range from 3% to 6%. Sexual addiction/hypersexual disorder is used as an umbrella construct to encompass various types of problematic behaviors, including excessive masturbation, cybersex, pornography use, sexual behavior with consenting adults, telephone sex, strip club visitation, and other behaviors. The adverse consequences of sexual addiction are similar to the consequences of other addictive disorders. Addictive, somatic and psychiatric disorders coexist with sexual addiction. In recent years, research on sexual addiction has proliferated, and screening instruments have increasingly been developed to diagnose or quantify sexual addiction disorders. In our systematic review of the existing measures, 22 questionnaires were identified. As with other behavioral addictions, the appropriate treatment of sexual addiction should combine pharmacological and psychological approaches.

- ^ 위로 이동: Pitchers KK, Vialou V, Nestler EJ, Laviolette SR, Lehman MN, Coolen LM (February 2013). "Natural and drug rewards act on common neural plasticity mechanisms with ΔFosB as a key mediator". The Journal of Neuroscience. 33 (8): 3434–42. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4881-12.2013. PMC 3865508. PMID 23426671.

Drugs of abuse induce neuroplasticity in the natural reward pathway, specifically the nucleus accumbens (NAc), thereby causing development and expression of addictive behavior. ... Together, these findings demonstrate that drugs of abuse and natural reward behaviors act on common molecular and cellular mechanisms of plasticity that control vulnerability to drug addiction, and that this increased vulnerability is mediated by ΔFosB and its downstream transcriptional targets. ... Sexual behavior is highly rewarding (Tenk et al., 2009), and sexual experience causes sensitized drug-related behaviors, including cross-sensitization to amphetamine (Amph)-induced locomotor activity (Bradley and Meisel, 2001; Pitchers et al., 2010a) and enhanced Amph reward (Pitchers et al., 2010a). Moreover, sexual experience induces neural plasticity in the NAc similar to that induced by psychostimulant exposure, including increased dendritic spine density (Meisel and Mullins, 2006; Pitchers et al., 2010a), altered glutamate receptor trafficking, and decreased synaptic strength in prefrontal cortex-responding NAc shell neurons (Pitchers et al., 2012). Finally, periods of abstinence from sexual experience were found to be critical for enhanced Amph reward, NAc spinogenesis (Pitchers et al., 2010a), and glutamate receptor trafficking (Pitchers et al., 2012). These findings suggest that natural and drug reward experiences share common mechanisms of neural plasticity

- ^ 위로 이동: Beloate LN, Weems PW, Casey GR, Webb IC, Coolen LM (February 2016). "Nucleus accumbens NMDA receptor activation regulates amphetamine cross-sensitization and deltaFosB expression following sexual experience in male rats". Neuropharmacology. 101: 154–64. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2015.09.023. PMID 26391065. S2CID 25317397.

- ^ Nehlig A (2004). Coffee, tea, chocolate, and the brain. Boca Raton: CRC Press. pp. 203–218. ISBN 9780429211928.

- ^ Meule A, Gearhardt AN (September 2014). "Food addiction in the light of DSM-5". Nutrients. 6 (9): 3653–71. doi:10.3390/nu6093653. PMC 4179181. PMID 25230209.

- ^ 위로 이동: Grant JE, Potenza MN, Weinstein A, Gorelick DA (September 2010). "Introduction to behavioral addictions". Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse. 36 (5): 233–241. doi:10.3109/00952990.2010.491884. PMC 3164585. PMID 20560821.

Naltrexone, a mu-opioid receptor antagonist approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of alcoholism and opioid dependence, has shown efficacy in controlled clinical trials for the treatment of pathological gambling and kleptomania (76–79), and promise in uncontrolled studies of compulsive buying (80), compulsive sexual behavior (81), internet addiction (82), and pathologic skin picking (83). ... Topiramate, an anti-convulsant which blocks the AMPA subtype of glutamate receptor (among other actions), has shown promise in open-label studies of pathological gambling, compulsive buying, and compulsive skin picking (85), as well as efficacy in reducing alcohol (86), cigarette (87), and cocaine (88) use. N-acetyl cysteine, an amino acid that restores extracellular glutamate concentration in the nucleus accumbens, reduced gambling urges and behavior in one study of pathological gamblers (89), and reduces cocaine craving (90) and cocaine use (91) in cocaine addicts. These studies suggest that glutamatergic modulation of dopaminergic tone in the nucleus accumbens may be a mechanism common to behavioral addiction and substance use disorders (92).

- ^ 위로 이동: Vassoler FM, Sadri-Vakili G (2014). "Mechanisms of transgenerational inheritance of addictive-like behaviors". Neuroscience. 264: 198–206. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.07.064. PMC 3872494. PMID 23920159.

However, the components that are responsible for the heritability of characteristics that make an individual more susceptible to drug addiction in humans remain largely unknown given that patterns of inheritance cannot be explained by simple genetic mechanisms (Cloninger et al., 1981; Schuckit et al., 1972). The environment also plays a large role in the development of addiction as evidenced by great societal variability in drug use patterns between countries and across time (UNODC, 2012). Therefore, both genetics and the environment contribute to an individual's vulnerability to become addicted following an initial exposure to drugs of abuse. ...

The evidence presented here demonstrates that rapid environmental adaptation occurs following exposure to a number of stimuli. Epigenetic mechanisms represent the key components by which the environment can influence genetics, and they provide the missing link between genetic heritability and environmental influences on the behavioral and physiological phenotypes of the offspring. - ^ Mayfield, R D; Harris, R A; Schuckit, M A (May 2008). "Genetic factors influencing alcohol dependence: Genetic factors and alcohol dependence". British Journal of Pharmacology. 154 (2): 275–287. doi:10.1038/bjp.2008.88. PMC 2442454. PMID 18362899.

- ^ 위로 이동: Kendler KS, Neale MC, Heath AC, Kessler RC, Eaves LJ (May 1994). "A twin-family study of alcoholism in women". Am J Psychiatry. 151 (5): 707–15. doi:10.1176/ajp.151.5.707. PMID 8166312.

- ^ Clarke TK, Crist RC, Kampman KM, Dackis CA, Pettinati HM, O'Brien CP, Oslin DW, Ferraro TN, Lohoff FW, Berrettini WH (2013). "Low frequency genetic variants in the μ-opioid receptor (OPRM1) affect risk for addiction to heroin and cocaine". Neuroscience Letters. 542: 71–75. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2013.02.018. PMC 3640707. PMID 23454283.

- ^ Hall FS, Drgonova J, Jain S, Uhl GR (December 2013). "Implications of genome wide association studies for addiction: are our a priori assumptions all wrong?". Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 140 (3): 267–79. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2013.07.006. PMC 3797854. PMID 23872493.

- ^ Crowe JR. "Genetics of alcoholism". Alcohol Health and Research World: 1–11. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- ^ Melemis SM. "The Genetics of Addiction – Is Addiction a Disease?". I Want to Change My Life. Retrieved 17 September 2018.

- ^ "Overdose Death Rates". National Institute on Drug Abuse. 9 August 2018. Retrieved 17 September 2018.

- ^ "Overdose Deaths Accelerating During Covid-19". Centers For Disease Control Prevention. 18 December 2020. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ Yang H, Ma J (August 2021). "How the COVID-19 pandemic impacts tobacco addiction: Changes in smoking behavior and associations with well-being". Addictive Behaviors. 119: 106917. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.106917. PMID 33862579. S2CID 233278782.

- ^ 위로 이동: "What are risk factors and protective factors?". National Institute on Drug Abuse. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- ^ "Understanding Drug Use and Addiction". www.drugabuse.gov. National Institute on Drug Abuse. 6 June 2018. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- ^ Lewis M (October 2018). Longo DL (ed.). "Brain Change in Addiction as Learning, Not Disease". The New England Journal of Medicine. 379 (16): 1551–1560. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1602872. PMID 30332573.

Addictive activities are determined neither solely by brain changes nor solely by social conditions ... the narrowing seen in addiction takes place within the behavioral repertoire, the social surround, and the brain — all at the same time.

- ^ 위로 이동: "Adverse Childhood Experiences". samhsa.gov. Rockville, Maryland, United States: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Archived from the original on 9 October 2016. Retrieved 26 September 2016.

- ^ 위로 이동: Enoch MA (March 2011). "The role of early life stress as a predictor for alcohol and drug dependence". Psychopharmacology. 214 (1): 17–31. doi:10.1007/s00213-010-1916-6. PMC 3005022. PMID 20596857.

- ^ "Environmental Risk Factors". learn.genetics.utah.edu. Archived from the original on 17 September 2018. Retrieved 17 September 2018.

- ^ Spear LP (June 2000). "The adolescent brain and age-related behavioral manifestations". Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 24 (4): 417–63. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.461.3295. doi:10.1016/s0149-7634(00)00014-2. PMID 10817843. S2CID 14686245.

- ^ Hammond CJ, Mayes LC, Potenza MN (April 2014). "Neurobiology of adolescent substance use and addictive behaviors: treatment implications". Adolescent Medicine. 25 (1): 15–32. PMC 4446977. PMID 25022184.

- ^ Catalano RF, Hawkins JD, Wells EA, Miller J, Brewer D (1990). "Evaluation of the effectiveness of adolescent drug abuse treatment, assessment of risks for relapse, and promising approaches for relapse prevention". The International Journal of the Addictions. 25 (9A–10A): 1085–140. doi:10.3109/10826089109081039. PMID 2131328.

- ^ Perepletchikova F, Krystal JH, Kaufman J (November 2008). "Practitioner review: adolescent alcohol use disorders: assessment and treatment issues". Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines. 49 (11): 1131–54. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01934.x. PMC 4113213. PMID 19017028.

- ^ "Age and Substance Abuse – Alcohol Rehab".

- ^ 위로 이동: "Nationwide Trends". National Institute on Drug Abuse. June 2015. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- ^ 위로 이동: "Addiction Statistics – Facts on Drug and Alcohol Addiction". AddictionCenter. Retrieved 17 September 2018.

- ^ SAMHSA. "Risk and Protective Factors". Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration. Archived from the original on 8 December 2016. Retrieved 19 December 2016.

- ^ "Infographic – Risk Factors of Addiction Recovery Research Institute". www.recoveryanswers.org. Archived from the original on 17 December 2016. Retrieved 19 December 2016.

- ^ "Drug addiction Risk factors – Mayo Clinic". www.mayoclinic.org. Retrieved 19 December 2016.

- ^ "The Connection Between Mental Illness and Substance Abuse Dual Diagnosis". Dual Diagnosis. Retrieved 17 September 2018.

- ^ 위로 이동: Yuan TF, Li A, Sun X, Ouyang H, Campos C, Rocha NB, Arias-Carrión O, Machado S, Hou G, So KF (2015). "Transgenerational Inheritance of Paternal Neurobehavioral Phenotypes: Stress, Addiction, Ageing and Metabolism". Mol. Neurobiol. 53 (9): 6367–76. doi:10.1007/s12035-015-9526-2. hdl:10400.22/7331. PMID 26572641. S2CID 25694221.

- ^ 위로 이동: "Drug abuse liability". www.cambridgecognition.com. Retrieved 9 March 2021.

- ^ National Institute on Drug Abuse (20 August 2020). "Commonly Used Drugs Charts". National Institute on Drug Abuse. Retrieved 9 March 2021.

- ^ 위로 이동: Renthal W, Nestler EJ (September 2009). "Chromatin regulation in drug addiction and depression". Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 11 (3): 257–268. PMC 2834246. PMID 19877494.

[Psychostimulants] increase cAMP levels in striatum, which activates protein kinase A (PKA) and leads to phosphorylation of its targets. This includes the cAMP response element binding protein (CREB), the phosphorylation of which induces its association with the histone acetyltransferase, CREB binding protein (CBP) to acetylate histones and facilitate gene activation. This is known to occur on many genes including fosB and c-fos in response to psychostimulant exposure. ΔFosB is also upregulated by chronic psychostimulant treatments, and is known to activate certain genes (eg, cdk5) and repress others (eg, c-fos) where it recruits HDAC1 as a corepressor. ... Chronic exposure to psychostimulants increases glutamatergic [signaling] from the prefrontal cortex to the NAc. Glutamatergic signaling elevates Ca2+ levels in NAc postsynaptic elements where it activates CaMK (calcium/calmodulin protein kinases) signaling, which, in addition to phosphorylating CREB, also phosphorylates HDAC5.

그림 2: 심리 자극에 의한 신호 이벤트 - ^ Broussard JI (January 2012). "Co-transmission of dopamine and glutamate". The Journal of General Physiology. 139 (1): 93–96. doi:10.1085/jgp.201110659. PMC 3250102. PMID 22200950.

Coincident and convergent input often induces plasticity on a postsynaptic neuron. The NAc integrates processed information about the environment from basolateral amygdala, hippocampus, and prefrontal cortex (PFC), as well as projections from midbrain dopamine neurons. Previous studies have demonstrated how dopamine modulates this integrative process. For example, high frequency stimulation potentiates hippocampal inputs to the NAc while simultaneously depressing PFC synapses (Goto and Grace, 2005). The converse was also shown to be true; stimulation at PFC potentiates PFC–NAc synapses but depresses hippocampal–NAc synapses. In light of the new functional evidence of midbrain dopamine/glutamate co-transmission (references above), new experiments of NAc function will have to test whether midbrain glutamatergic inputs bias or filter either limbic or cortical inputs to guide goal-directed behavior.

- ^ Kanehisa Laboratories (10 October 2014). "Amphetamine – Homo sapiens (human)". KEGG Pathway. Retrieved 31 October 2014.

Most addictive drugs increase extracellular concentrations of dopamine (DA) in nucleus accumbens (NAc) and medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), projection areas of mesocorticolimbic DA neurons and key components of the "brain reward circuit". Amphetamine achieves this elevation in extracellular levels of DA by promoting efflux from synaptic terminals. ... Chronic exposure to amphetamine induces a unique transcription factor delta FosB, which plays an essential role in long-term adaptive changes in the brain.

- ^ Cadet JL, Brannock C, Jayanthi S, Krasnova IN (2015). "Transcriptional and epigenetic substrates of methamphetamine addiction and withdrawal: evidence from a long-access self-administration model in the rat". Molecular Neurobiology. 51 (2): 696–717. doi:10.1007/s12035-014-8776-8. PMC 4359351. PMID 24939695.

Figure 1

- ^ 위로 이동: Robison AJ, Nestler EJ (November 2011). "Transcriptional and epigenetic mechanisms of addiction". Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 12 (11): 623–637. doi:10.1038/nrn3111. PMC 3272277. PMID 21989194.

ΔFosB serves as one of the master control proteins governing this structural plasticity. ... ΔFosB also represses G9a expression, leading to reduced repressive histone methylation at the cdk5 gene. The net result is gene activation and increased CDK5 expression. ... In contrast, ΔFosB binds to the c-fos gene and recruits several co-repressors, including HDAC1 (histone deacetylase 1) and SIRT 1 (sirtuin 1). ... The net result is c-fos gene repression.

그림 4: 유전자 발현에 대한 약물 조절 후생유전적 - ^ 위로 이동: Nestler EJ (December 2012). "Transcriptional mechanisms of drug addiction". Clinical Psychopharmacology and Neuroscience. 10 (3): 136–143. doi:10.9758/cpn.2012.10.3.136. PMC 3569166. PMID 23430970.

The 35-37 kD ΔFosB isoforms accumulate with chronic drug exposure due to their extraordinarily long half-lives. ... As a result of its stability, the ΔFosB protein persists in neurons for at least several weeks after cessation of drug exposure. ... ΔFosB overexpression in nucleus accumbens induces NFκB ... In contrast, the ability of ΔFosB to repress the c-Fos gene occurs in concert with the recruitment of a histone deacetylase and presumably several other repressive proteins such as a repressive histone methyltransferase

- ^ Nestler EJ (October 2008). "Transcriptional mechanisms of addiction: Role of ΔFosB". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 363 (1507): 3245–3255. doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0067. PMC 2607320. PMID 18640924.

Recent evidence has shown that ΔFosB also represses the c-fos gene that helps create the molecular switch—from the induction of several short-lived Fos family proteins after acute drug exposure to the predominant accumulation of ΔFosB after chronic drug exposure

- ^ 위로 이동: Hyman SE, Malenka RC, Nestler EJ (2006). "Neural mechanisms of addiction: the role of reward-related learning and memory". Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 29: 565–98. doi:10.1146/annurev.neuro.29.051605.113009. PMID 16776597.

- ^ Steiner H, Van Waes V (January 2013). "Addiction-related gene regulation: risks of exposure to cognitive enhancers vs. other psychostimulants". Prog. Neurobiol. 100: 60–80. doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2012.10.001. PMC 3525776. PMID 23085425.

- ^ Kanehisa Laboratories (2 August 2013). "Alcoholism – Homo sapiens (human)". KEGG Pathway. Retrieved 10 April 2014.

- ^ Kim Y, Teylan MA, Baron M, Sands A, Nairn AC, Greengard P (February 2009). "Methylphenidate-induced dendritic spine formation and DeltaFosB expression in nucleus accumbens". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 106 (8): 2915–20. Bibcode:2009PNAS..106.2915K. doi:10.1073/pnas.0813179106. PMC 2650365. PMID 19202072.

- ^ 위로 이동: Nestler EJ (January 2014). "Epigenetic mechanisms of drug addiction". Neuropharmacology. 76 Pt B: 259–68. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.04.004. PMC 3766384. PMID 23643695.

Short-term increases in histone acetylation generally promote behavioral responses to the drugs, while sustained increases oppose cocaine's effects, based on the actions of systemic or intra-NAc administration of HDAC inhibitors. ... Genetic or pharmacological blockade of G9a in the NAc potentiates behavioral responses to cocaine and opiates, whereas increasing G9a function exerts the opposite effect (Maze et al., 2010; Sun et al., 2012a). Such drug-induced downregulation of G9a and H3K9me2 also sensitizes animals to the deleterious effects of subsequent chronic stress (Covington et al., 2011). Downregulation of G9a increases the dendritic arborization of NAc neurons, and is associated with increased expression of numerous proteins implicated in synaptic function, which directly connects altered G9a/H3K9me2 in the synaptic plasticity associated with addiction (Maze et al., 2010).

G9a appears to be a critical control point for epigenetic regulation in NAc, as we know it functions in two negative feedback loops. It opposes the induction of ΔFosB, a long-lasting transcription factor important for drug addiction (Robison and Nestler, 2011), while ΔFosB in turn suppresses G9a expression (Maze et al., 2010; Sun et al., 2012a). ... Also, G9a is induced in NAc upon prolonged HDAC inhibition, which explains the paradoxical attenuation of cocaine's behavioral effects seen under these conditions, as noted above (Kennedy et al., 2013). GABAA receptor subunit genes are among those that are controlled by this feedback loop. Thus, chronic cocaine, or prolonged HDAC inhibition, induces several GABAA receptor subunits in NAc, which is associated with increased frequency of inhibitory postsynaptic currents (IPSCs). In striking contrast, combined exposure to cocaine and HDAC inhibition, which triggers the induction of G9a and increased global levels of H3K9me2, leads to blockade of GABAA receptor and IPSC regulation. - ^ 위로 이동: Blum K, Werner T, Carnes S, Carnes P, Bowirrat A, Giordano J, Oscar-Berman M, Gold M (2012). "Sex, drugs, and rock 'n' roll: hypothesizing common mesolimbic activation as a function of reward gene polymorphisms". Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 44 (1): 38–55. doi:10.1080/02791072.2012.662112. PMC 4040958. PMID 22641964.

It has been found that deltaFosB gene in the NAc is critical for reinforcing effects of sexual reward. Pitchers and colleagues (2010) reported that sexual experience was shown to cause DeltaFosB accumulation in several limbic brain regions including the NAc, medial pre-frontal cortex, VTA, caudate, and putamen, but not the medial preoptic nucleus. Next, the induction of c-Fos, a downstream (repressed) target of DeltaFosB, was measured in sexually experienced and naive animals. The number of mating-induced c-Fos-IR cells was significantly decreased in sexually experienced animals compared to sexually naive controls. Finally, DeltaFosB levels and its activity in the NAc were manipulated using viral-mediated gene transfer to study its potential role in mediating sexual experience and experience-induced facilitation of sexual performance. Animals with DeltaFosB overexpression displayed enhanced facilitation of sexual performance with sexual experience relative to controls. In contrast, the expression of DeltaJunD, a dominant-negative binding partner of DeltaFosB, attenuated sexual experience-induced facilitation of sexual performance, and stunted long-term maintenance of facilitation compared to DeltaFosB overexpressing group. Together, these findings support a critical role for DeltaFosB expression in the NAc in the reinforcing effects of sexual behavior and sexual experience-induced facilitation of sexual performance. ... both drug addiction and sexual addiction represent pathological forms of neuroplasticity along with the emergence of aberrant behaviors involving a cascade of neurochemical changes mainly in the brain's rewarding circuitry.

- ^ Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). "Chapter 15: Reinforcement and addictive disorders". In Sydor A, Brown RY (eds.). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. pp. 384–85. ISBN 978-0-07-148127-4.

- ^ Salamone JD (1992). "Complex motor and sensorimotor functions of striatal and accumbens dopamine: involvement in instrumental behavior processes". Psychopharmacology. 107 (2–3): 160–74. doi:10.1007/bf02245133. PMID 1615120. S2CID 30545845.

- ^ Kauer JA, Malenka RC (November 2007). "Synaptic plasticity and addiction". Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 8 (11): 844–58. doi:10.1038/nrn2234. PMID 17948030. S2CID 38811195.

- ^ Witten IB, Lin SC, Brodsky M, Prakash R, Diester I, Anikeeva P, et al. (December 2010). "Cholinergic interneurons control local circuit activity and cocaine conditioning". Science. 330 (6011): 1677–81. Bibcode:2010Sci...330.1677W. doi:10.1126/science.1193771. PMC 3142356. PMID 21164015.

- ^ 위로 이동: Nestler EJ, Barrot M, Self DW (September 2001). "DeltaFosB: a sustained molecular switch for addiction". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98 (20): 11042–46. Bibcode:2001PNAS...9811042N. doi:10.1073/pnas.191352698. PMC 58680. PMID 11572966.

Although the ΔFosB signal is relatively long-lived, it is not permanent. ΔFosB degrades gradually and can no longer be detected in brain after 1–2 months of drug withdrawal ... Indeed, ΔFosB is the longest-lived adaptation known to occur in adult brain, not only in response to drugs of abuse, but to any other perturbation (that doesn't involve lesions) as well.

- ^ 위로 이동: Jones S, Bonci A (2005). "Synaptic plasticity and drug addiction". Current Opinion in Pharmacology. 5 (1): 20–25. doi:10.1016/j.coph.2004.08.011. PMID 15661621.

- ^ 위로 이동: Eisch AJ, Harburg GC (2006). "Opiates, psychostimulants, and adult hippocampal neurogenesis: Insights for addiction and stem cell biology". Hippocampus. 16 (3): 271–86. doi:10.1002/hipo.20161. PMID 16411230. S2CID 23667629.

- ^ Rang HP (2003). Pharmacology. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. p. 596. ISBN 978-0-443-07145-4.

- ^ Kourrich S, Rothwell PE, Klug JR, Thomas MJ (2007). "Cocaine experience controls bidirectional synaptic plasticity in the nucleus accumbens". J. Neurosci. 27 (30): 7921–28. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1859-07.2007. PMC 6672735. PMID 17652583.

- ^ 위로 이동: Kalivas PW, Volkow ND (August 2005). "The neural basis of addiction: a pathology of motivation and choice". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 162 (8): 1403–13. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.162.8.1403. PMID 16055761.

- ^ 위로 이동: Floresco SB, Ghods-Sharifi S (February 2007). "Amygdala-prefrontal cortical circuitry regulates effort-based decision making". Cerebral Cortex. 17 (2): 251–60. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.335.4681. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhj143. PMID 16495432.

- ^ Perry CJ, Zbukvic I, Kim JH, Lawrence AJ (October 2014). "Role of cues and contexts on drug-seeking behaviour". British Journal of Pharmacology. 171 (20): 4636–72. doi:10.1111/bph.12735. PMC 4209936. PMID 24749941.

- ^ 위로 이동: Volkow ND, Fowler JS, Wang GJ, Swanson JM, Telang F (2007). "Dopamine in drug abuse and addiction: results of imaging studies and treatment implications". Arch. Neurol. 64 (11): 1575–79. doi:10.1001/archneur.64.11.1575. PMID 17998440.

- ^ "Drugs, Brains, and Behavior: The Science of Addiction". National Institute on Drug Abuse.

- ^ "Understanding Drug Abuse and Addiction". National Institute on Drug Abuse. November 2012. Archived from the original on 23 August 2011. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- ^ 위로 이동: Nestler EJ (October 2008). "Review. Transcriptional mechanisms of addiction: role of DeltaFosB". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 363 (1507): 3245–55. doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0067. PMC 2607320. PMID 18640924.