단백질병증

Proteinopathy| 단백질병증 | |

|---|---|

| |

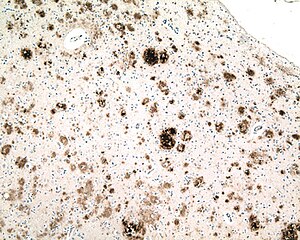

| 알츠하이머병 환자의 대뇌피질 한 부분의 마이크로그래프, 아밀로이드 베타(갈색) 항체로 면역된, 아밀로이드 판과 뇌 아밀로이드 혈관병증에 축적된 단백질 파편. 현미경 목표 10배 |

의학에서는 단백질병증(/proʊtiˈɒpəəi//; [pref]. 단백질]; -pathy [질병]; 단백요병 pl.; 단백질 요법(domentopathic adjust) 또는 단백질 요법, 단백질 순응 장애, 단백질이 잘못 접히는 질병은 특정 단백질이 구조적으로 비정상적으로 되어 결과적으로 신체의 세포, 조직, 장기의 기능을 방해하는 질병의 종류를 말한다.[1][2] 종종 단백질은 그들의 정상적인 구성으로 접히지 못한다; 이 잘못 접힌 상태에서, 단백질은 어떤 방식으로든 독성이 생기거나 정상적인 기능을 상실할 수 있다.[3] 단백질 요법에는 크로이츠펠트-야콥병 등 프리온병, 알츠하이머병, 파킨슨병, 아밀로이드증, 다중계통 위축, 기타 광범위한 질환이 포함된다.[2][4][5][6][7][8] 프로테오병증이라는 용어는 2000년 래리 워커와 해리 르바인에 의해 처음 제안되었다.[1]

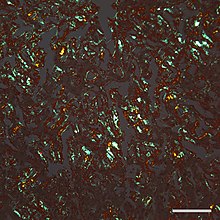

단백질병증의 개념은 그 기원을 추적할 수 있는데, 1854년 루돌프 비르초는 섬유소와 유사한 화학반응을 보이는 뇌기업 아밀레이시아의 물질을 설명하기 위해 아밀로이드("starch like")라는 용어를 만들었다. 1859년 프리드리치와 케쿨레는 셀룰로오스로 구성되기 보다는 "아밀로이드"가 실제로 단백질이 풍부하다는 것을 증명했다.[9] 이후의 연구는 많은 다른 단백질들이 아밀로이드를 형성할 수 있다는 것을 보여주었고, 모든 아밀로이드는 콩고 적색 염료와 함께 얼룩진 후 교차 양극화된 빛에서 이irefringence를 나타내며, 전자 현미경으로 보았을 때 섬유 초경량 구조를 보여준다.[9] 그러나 일부 단백질의 병변은 이두박근이 부족하고 알츠하이머병 환자의 뇌에 아밀로이드 베타(Aβ) 단백질의 확산 퇴적물과 같은 고전적인 아밀로이드 섬유질을 거의 또는 전혀 함유하지 않는다.[10] 게다가, 과점이라고 알려진 작고 비-Fibrillar 단백질 골재가 영향을 받는 기관의 세포에 독성이 있으며, 섬유 형태에 있는 아밀로이드 유발 단백질이 상대적으로 양성일 수 있다는 증거가 나타났다.[11][12]

병리학

대부분의 경우, 모든 단백질 요법은 아닐지라도, 3차원 폴딩 순응의 변화는 특정 단백질이 스스로 결합하는 경향을 증가시킨다.[5] 이 집계된 형태에서 단백질은 간극에 내성이 있으며 영향을 받는 장기의 정상 용량을 방해할 수 있다. 단백질을 잘못 접으면 평상시 기능이 상실되는 경우도 있다. 예를 들어, 낭포성 섬유증 결함이 있는 낭포성 섬유증 막관통 전도도 조절기(CFTR)protein,[3]과인 근 위축성 측색 경화증/전 측두엽 대엽성 변성(FTLD), 어떤gene-regulating 단백질이 부적절하게질 안에서며, 따라서 nucleu 내에 그들의 정상적인 작업을 수행할 수 없는 골재에에 의해 발생한다.s.[13][14] 단백질은 폴리펩타이드 백본이라고 알려진 공통적인 구조적 특징을 공유하기 때문에, 모든 단백질은 어떤 상황에서 잘못 접힐 수 있는 가능성을 가지고 있다.[15] 그러나 상대적으로 적은 수의 단백질만이 프로테오패스 장애와 연관되어 있는데, 아마도 취약한 단백질의 구조적 특성 때문일 것이다. 예를 들어, 일반적으로 펼치거나 모노머로서 상대적으로 불안정한 단백질(즉, 결합되지 않은 단일 단백질 분자)은 비정상적인 순응으로 잘못 접힐 가능성이 높다.[5][15][16] 거의 모든 경우에, 질병을 유발하는 분자 구성은 단백질의 베타-시트 이차 구조의 증가를 포함한다.[5][15][17][18][19] 일부 프로테오패스에서 비정상적인 단백질은 여러 3차원 모양으로 접히는 것으로 나타났다. 이러한 변형, 단백질 구조는 병원성, 생화학적, 그리고 순응적 특성에 의해 정의된다.[20] 그것들은 프리온 질환과 관련하여 가장 철저하게 연구되어 왔으며, 단백질 변종이라고 불린다.[21][22]

단백질의 자가조립을 촉진하는 특정 위험요인에 의해 단백질병증이 발전할 가능성이 증가한다. 여기에는 단백질의 1차 아미노산 염기서열 변화, 변환 후 수정(초인산화 등), 온도 또는 pH 변화, 단백질 생산 증가 또는 간극 감소가 포함된다.[1][5][15] 나이가 드는 것은 외상성 뇌손상과 마찬가지로 강한 위험 요인이다.[1][23][24] 노화된 뇌에서는 여러 프로테오페라피스가 겹칠 수 있다.[25] 예를 들어, 타우병증과 아β-아밀로이드증(알츠하이머병의 주요 병리학적 특징으로 공존하는 것) 외에도 많은 알츠하이머 환자들이 뇌에 동반성 시핵병증(Lewy body)을 가지고 있다.[26]

보호자와 공동 보호자(단백질 접힘을 돕는 단백질)는 프로토스타시를 유지하기 위해 노화와 단백질 오접화 질환에서 프로토타독성에 반감을 일으킬 수 있다는 가설이 제기된다.[27][28][29]

시드 유도

어떤 단백질은 질병을 유발하는 순응으로 접어든 같은 (또는 비슷한) 단백질에 노출되어 비정상적인 조립체를 형성하도록 유도될 수 있는데, 이것은 '씨앗기' 또는 '허용성 템플리트'라고 불리는 과정이다.[30][31] 이런 식으로, 질병 상태는 고통받는 기증자로부터 병든 조직 추출물의 도입에 의해 취약한 숙주로 불러올 수 있다. 유도성 단백질병증의 가장 잘 알려진 형태는 프리온 질환으로,[32] 질병을 유발하는 순응에서 숙주 유기체가 정제 프리온 단백질에 노출되면 전염될 수 있다.[33][34] 현재 증거는 다른 proteinopathies는 유사한 메커니즘에 의해, Aβ의 아밀로이드 침전물을 포함한(AA)아밀로이드증, 아포 이제 amyloidosis,[31일][35]tauopathy,[36]synucleinopathy,[37][38][39][40]고(dismutase-1(SOD1)[41][42]polyglutamine,[43][44]와 TARDNA-binding protein-43의 집계 amyloid 유발할 수 있다. (TDP-43).[45]

이러한 모든 경우에서 단백질 자체의 일탈 형태는 병원성 물질로 나타난다. 어떤 경우에는 단백질 분자의 구조적 상호보완성 때문에 β-시트 구조가 풍부한 다른 단백질의 집합체에 의해 한 가지 유형의 단백질의 침적을 실험적으로 유도할 수 있다. 예를 들어, AA 아밀로이드증은 비단, 효모 아밀로이드 Sup35 그리고 대장균 박테리아에서 나오는 컬리 섬유소와 같은 다양한 고분자에 의해 생쥐에서 자극을 받을 수 있다.[46] AII 아밀로이드는 생쥐에서 다양한 β시트의 풍부한 아밀로이드 섬유질에 의해 유도될 수 있으며,[47] 뇌 타우병증은 집계된 Aβ가 풍부한 뇌 추출물에 의해 유도될 수 있다.[48] 프리온 단백질과 아β 사이의 교차 시딩에 대한 실험적 증거도 있다.[49] 일반적으로 이러한 이질성 씨뿌리는 같은 단백질의 부패한 형태에 의해 씨뿌리는 것보다 효율성이 떨어진다.

단백질 요법 목록

관리

많은 프로테오패스들에게 효과적인 치료법의 개발은 도전적이었다.[74][75] 프로테오페라티스는 종종 다른 원천으로부터 발생하는 다른 단백질을 포함하기 때문에, 치료 전략은 각 장애에 따라 맞춤화되어야 한다. 그러나 일반적인 치료 방법에는 영향을 받는 장기의 기능을 유지하고, 질병을 유발하는 단백질의 형성을 감소시키며, 단백질이 잘못 접히는 것을 방지하고, 또는 아그로그를 방지하는 것이 포함된다.자만하거나 그들의 제거를 홍보하는 것.[76][74][77] 예를 들어 알츠하이머병에서는 연구자들이 모체 단백질로부터 해방시키는 효소를 억제함으로써 질병과 연관된 단백질 Aβ의 생산을 줄이는 방법을 모색하고 있다.[75] 또 다른 전략은 항체를 이용해 활성 또는 수동적 면역으로 특정 단백질을 중화시키는 것이다.[78] 일부 프로테오페라시즘에서는 단백질 과점제의 독성 효과를 억제하는 것이 유익할 수 있다.[79] 아밀로이드 A(AA) 아밀로이드증은 혈중 단백질의 양을 증가시키는 염증 상태(세럼 아밀로이드 A, 또는 SAA라고 한다)를 치료하면 줄일 수 있다.[74] 면역글로불린 빛사슬 아밀로이드증(AL 아밀로이드증)에서는 화학요법을 이용해 여러 신체기관에서 아밀로이드를 형성하는 경사슬 단백질을 만드는 혈구의 수를 낮출 수 있다.[80] TTR(트란스트히레틴) 아밀로이드증(ATTR)은 여러 장기에 잘못 접힌 TTR이 축적된 데서 비롯된다.[81] TTR은 주로 간에서 생성되기 때문에 일부 유전적 경우 간 이식에 의해 TTR 아밀로이드증이 느려질 수 있다.[82] 또한 TTR 아밀로이드증은 단백질의 정상적인 조립체를 안정화시켜 치료할 수 있다(TTR 분자는 서로 결합되어 있는 4개의 TTR 분자로 구성되어 있기 때문에 테트라머라 불린다). 안정화는 개별 TTR 분자가 빠져나와 잘못 접히고 아밀로이드로 집적되는 것을 방지한다.[83][84]

작은 간섭 RNA, 항이센스 올리고뉴클레오티드, 펩타이드, 공학적 면역세포와 같은 작은 분자와 생물학적 약물을 포함한 프로테오페티스를 위한 몇 가지 다른 치료 전략이 연구되고 있다.[83][80][85][86] 어떤 경우에는 효과를 높이기 위해 여러 가지 치료제를 결합할 수도 있다.[80][87]

추가 이미지

참고 항목

참조

- ^ a b c d Walker LC, LeVine H (2000). "The cerebral proteopathies". Neurobiology of Aging. 21 (4): 559–61. doi:10.1016/S0197-4580(00)00160-3. PMID 10924770. S2CID 54314137.

- ^ a b Walker LC, LeVine H (2000). "The cerebral proteopathies: neurodegenerative disorders of protein conformation and assembly". Molecular Neurobiology. 21 (1–2): 83–95. doi:10.1385/MN:21:1-2:083. PMID 11327151. S2CID 32618330.

- ^ a b Luheshi LM, Crowther DC, Dobson CM (February 2008). "Protein misfolding and disease: from the test tube to the organism". Current Opinion in Chemical Biology. 12 (1): 25–31. doi:10.1016/j.cbpa.2008.02.011. PMID 18295611.

- ^ Chiti F, Dobson CM (2006). "Protein misfolding, functional amyloid, and human disease". Annual Review of Biochemistry. 75 (1): 333–66. doi:10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.101304.123901. PMID 16756495.

- ^ a b c d e Carrell RW, Lomas DA (July 1997). "Conformational disease". Lancet. 350 (9071): 134–8. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(97)02073-4. PMID 9228977. S2CID 39124185.

- ^ Westermark P, Benson MD, Buxbaum JN, Cohen AS, Frangione B, Ikeda S, Masters CL, Merlini G, Saraiva MJ, Sipe JD (September 2007). "A primer of amyloid nomenclature". Amyloid. 14 (3): 179–83. doi:10.1080/13506120701460923. PMID 17701465. S2CID 12480248.

- ^ Westermark GT, Fändrich M, Lundmark K, Westermark P (January 2018). "Noncerebral Amyloidoses: Aspects on Seeding, Cross-Seeding, and Transmission". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine. 8 (1): a024323. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a024323. PMC 5749146. PMID 28108533.

- ^ Prusiner SB (2013). "Biology and genetics of prions causing neurodegeneration". Annual Review of Genetics. 47: 601–23. doi:10.1146/annurev-genet-110711-155524. PMC 4010318. PMID 24274755.

- ^ a b Sipe JD, Cohen AS (June 2000). "Review: history of the amyloid fibril". Journal of Structural Biology. 130 (2–3): 88–98. doi:10.1006/jsbi.2000.4221. PMID 10940217.

- ^ Wisniewski HM, Sadowski M, Jakubowska-Sadowska K, Tarnawski M, Wegiel J (July 1998). "Diffuse, lake-like amyloid-beta deposits in the parvopyramidal layer of the presubiculum in Alzheimer disease". Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology. 57 (7): 674–83. doi:10.1097/00005072-199807000-00004. PMID 9690671.

- ^ Glabe CG (April 2006). "Common mechanisms of amyloid oligomer pathogenesis in degenerative disease". Neurobiology of Aging. 27 (4): 570–5. doi:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.04.017. PMID 16481071. S2CID 32899741.

- ^ Gadad BS, Britton GB, Rao KS (2011). "Targeting oligomers in neurodegenerative disorders: lessons from α-synuclein, tau, and amyloid-β peptide". Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 24 Suppl 2: 223–32. doi:10.3233/JAD-2011-110182. PMID 21460436.

- ^ Ito D, Suzuki N (October 2011). "Conjoint pathologic cascades mediated by ALS/FTLD-U linked RNA-binding proteins TDP-43 and FUS". Neurology. 77 (17): 1636–43. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182343365. PMC 3198978. PMID 21956718.

- ^ Wolozin B, Apicco D (2015). "RNA binding proteins and the genesis of neurodegenerative diseases". Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 822: 11–5. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-08927-0_3. ISBN 978-3-319-08926-3. PMC 4694570. PMID 25416971.

{{cite journal}}: Cite 저널은 필요로 한다.journal=(도움말) - ^ a b c d Dobson CM (September 1999). "Protein misfolding, evolution and disease". Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 24 (9): 329–32. doi:10.1016/S0968-0004(99)01445-0. PMID 10470028.

- ^ a b Jucker M, Walker LC (September 2013). "Self-propagation of pathogenic protein aggregates in neurodegenerative diseases". Nature. 501 (7465): 45–51. Bibcode:2013Natur.501...45J. doi:10.1038/nature12481. PMC 3963807. PMID 24005412.

- ^ Selkoe DJ (December 2003). "Folding proteins in fatal ways". Nature. 426 (6968): 900–4. Bibcode:2003Natur.426..900S. doi:10.1038/nature02264. PMID 14685251. S2CID 6451881.

- ^ Eisenberg D, Jucker M (March 2012). "The amyloid state of proteins in human diseases". Cell. 148 (6): 1188–203. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.022. PMC 3353745. PMID 22424229.

- ^ Röhr D, Boon BD (December 2020). "Label-free vibrational imaging of different Aβ plaque types in Alzheimer's disease reveals sequential events in plaque development". Acta Neuropathologica Communications. 8 (1): 222. doi:10.1186/s40478-020-01091-5. PMC 7733282. PMID 33308303.

- ^ Walker LC (November 2016). "Proteopathic Strains and the Heterogeneity of Neurodegenerative Diseases". Annual Review of Genetics. 50: 329–346. doi:10.1146/annurev-genet-120215-034943. PMC 6690197. PMID 27893962.

- ^ Collinge J, Clarke AR (November 2007). "A general model of prion strains and their pathogenicity". Science. 318 (5852): 930–6. Bibcode:2007Sci...318..930C. doi:10.1126/science.1138718. PMID 17991853.

- ^ Colby DW, Prusiner SB (September 2011). "De novo generation of prion strains". Nature Reviews. Microbiology. 9 (11): 771–7. doi:10.1038/nrmicro2650. PMC 3924856. PMID 21947062.

- ^ DeKosky ST, Ikonomovic MD, Gandy S (September 2010). "Traumatic brain injury--football, warfare, and long-term effects". The New England Journal of Medicine. 363 (14): 1293–6. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1007051. PMID 20879875.

- ^ McKee AC, Stein TD, Kiernan PT, Alvarez VE (May 2015). "The neuropathology of chronic traumatic encephalopathy". Brain Pathology. 25 (3): 350–64. doi:10.1111/bpa.12248. PMC 4526170. PMID 25904048.

- ^ Nelson PT, Alafuzoff I, Bigio EH, Bouras C, Braak H, Cairns NJ, Castellani RJ, Crain BJ, Davies P, Del Tredici K, Duyckaerts C, Frosch MP, Haroutunian V, Hof PR, Hulette CM, Hyman BT, Iwatsubo T, Jellinger KA, Jicha GA, Kövari E, Kukull WA, Leverenz JB, Love S, Mackenzie IR, Mann DM, Masliah E, McKee AC, Montine TJ, Morris JC, Schneider JA, Sonnen JA, Thal DR, Trojanowski JQ, Troncoso JC, Wisniewski T, Woltjer RL, Beach TG (May 2012). "Correlation of Alzheimer disease neuropathologic changes with cognitive status: a review of the literature". Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology. 71 (5): 362–81. doi:10.1097/NEN.0b013e31825018f7. PMC 3560290. PMID 22487856.

- ^ Mrak RE, Griffin WS (2007). "Dementia with Lewy bodies: Definition, diagnosis, and pathogenic relationship to Alzheimer's disease". Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment. 3 (5): 619–25. PMC 2656298. PMID 19300591.

- ^ Douglas PM, Summers DW, Cyr DM (2009). "Molecular chaperones antagonize proteotoxicity by differentially modulating protein aggregation pathways". Prion. 3 (2): 51–8. doi:10.4161/pri.3.2.8587. PMC 2712599. PMID 19421006.

- ^ Brehme M, Voisine C, Rolland T, Wachi S, Soper JH, Zhu Y, Orton K, Villella A, Garza D, Vidal M, Ge H, Morimoto RI (November 2014). "A chaperome subnetwork safeguards proteostasis in aging and neurodegenerative disease". Cell Reports. 9 (3): 1135–50. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2014.09.042. PMC 4255334. PMID 25437566.

- ^ Brehme M, Voisine C (August 2016). "Model systems of protein-misfolding diseases reveal chaperone modifiers of proteotoxicity". Disease Models & Mechanisms. 9 (8): 823–38. doi:10.1242/dmm.024703. PMC 5007983. PMID 27491084.

- ^ Hardy J (August 2005). "Expression of normal sequence pathogenic proteins for neurodegenerative disease contributes to disease risk: 'permissive templating' as a general mechanism underlying neurodegeneration". Biochemical Society Transactions. 33 (Pt 4): 578–81. doi:10.1042/BST0330578. PMID 16042548.

- ^ a b Walker LC, Levine H, Mattson MP, Jucker M (August 2006). "Inducible proteopathies". Trends in Neurosciences. 29 (8): 438–43. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2006.06.010. PMID 16806508. S2CID 46630402.

- ^ Prusiner SB (May 2001). "Shattuck lecture--neurodegenerative diseases and prions". The New England Journal of Medicine. 344 (20): 1516–26. doi:10.1056/NEJM200105173442006. PMID 11357156.

- ^ Zou WQ, Gambetti P (April 2005). "From microbes to prions the final proof of the prion hypothesis". Cell. 121 (2): 155–7. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2005.04.002. PMID 15851020.

- ^ Ma J (2012). "The role of cofactors in prion propagation and infectivity". PLOS Pathogens. 8 (4): e1002589. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1002589. PMC 3325206. PMID 22511864.

- ^ Meyer-Luehmann M, Coomaraswamy J, Bolmont T, Kaeser S, Schaefer C, Kilger E, Neuenschwander A, Abramowski D, Frey P, Jaton AL, Vigouret JM, Paganetti P, Walsh DM, Mathews PM, Ghiso J, Staufenbiel M, Walker LC, Jucker M (September 2006). "Exogenous induction of cerebral beta-amyloidogenesis is governed by agent and host". Science. 313 (5794): 1781–4. Bibcode:2006Sci...313.1781M. doi:10.1126/science.1131864. PMID 16990547. S2CID 27127208.

- ^ Clavaguera F, Bolmont T, Crowther RA, Abramowski D, Frank S, Probst A, Fraser G, Stalder AK, Beibel M, Staufenbiel M, Jucker M, Goedert M, Tolnay M (July 2009). "Transmission and spreading of tauopathy in transgenic mouse brain". Nature Cell Biology. 11 (7): 909–13. doi:10.1038/ncb1901. PMC 2726961. PMID 19503072.

- ^ Desplats P, Lee HJ, Bae EJ, Patrick C, Rockenstein E, Crews L, Spencer B, Masliah E, Lee SJ (August 2009). "Inclusion formation and neuronal cell death through neuron-to-neuron transmission of alpha-synuclein". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 106 (31): 13010–5. doi:10.1073/pnas.0903691106. PMC 2722313. PMID 19651612.

- ^ Hansen C, Angot E, Bergström AL, Steiner JA, Pieri L, Paul G, Outeiro TF, Melki R, Kallunki P, Fog K, Li JY, Brundin P (February 2011). "α-Synuclein propagates from mouse brain to grafted dopaminergic neurons and seeds aggregation in cultured human cells". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 121 (2): 715–25. doi:10.1172/JCI43366. PMC 3026723. PMID 21245577.

- ^ Kordower JH, Dodiya HB, Kordower AM, Terpstra B, Paumier K, Madhavan L, Sortwell C, Steece-Collier K, Collier TJ (September 2011). "Transfer of host-derived α synuclein to grafted dopaminergic neurons in rat". Neurobiology of Disease. 43 (3): 552–7. doi:10.1016/j.nbd.2011.05.001. PMC 3430516. PMID 21600984.

- ^ Kordower JH, Chu Y, Hauser RA, Freeman TB, Olanow CW (May 2008). "Lewy body-like pathology in long-term embryonic nigral transplants in Parkinson's disease". Nature Medicine. 14 (5): 504–6. doi:10.1038/nm1747. PMID 18391962. S2CID 11991816.

- ^ Chia R, Tattum MH, Jones S, Collinge J, Fisher EM, Jackson GS (May 2010). Feany MB (ed.). "Superoxide dismutase 1 and tgSOD1 mouse spinal cord seed fibrils, suggesting a propagative cell death mechanism in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis". PLOS ONE. 5 (5): e10627. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0010627. PMC 2869360. PMID 20498711.

- ^ Münch C, O'Brien J, Bertolotti A (March 2011). "Prion-like propagation of mutant superoxide dismutase-1 misfolding in neuronal cells". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 108 (9): 3548–53. Bibcode:2011PNAS..108.3548M. doi:10.1073/pnas.1017275108. PMC 3048161. PMID 21321227.

- ^ Ren PH, Lauckner JE, Kachirskaia I, Heuser JE, Melki R, Kopito RR (February 2009). "Cytoplasmic penetration and persistent infection of mammalian cells by polyglutamine aggregates". Nature Cell Biology. 11 (2): 219–25. doi:10.1038/ncb1830. PMC 2757079. PMID 19151706.

- ^ Pearce MM, Kopito RR (February 2018). "Prion-Like Characteristics of Polyglutamine-Containing Proteins". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine. 8 (2): a024257. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a024257. PMC 5793740. PMID 28096245.

- ^ Furukawa Y, Kaneko K, Watanabe S, Yamanaka K, Nukina N (May 2011). "A seeding reaction recapitulates intracellular formation of Sarkosyl-insoluble transactivation response element (TAR) DNA-binding protein-43 inclusions". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 286 (21): 18664–72. doi:10.1074/jbc.M111.231209. PMC 3099683. PMID 21454603.

- ^ Lundmark K, Westermark GT, Olsén A, Westermark P (April 2005). "Protein fibrils in nature can enhance amyloid protein A amyloidosis in mice: Cross-seeding as a disease mechanism". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 102 (17): 6098–102. Bibcode:2005PNAS..102.6098L. doi:10.1073/pnas.0501814102. PMC 1087940. PMID 15829582.

- ^ Fu X, Korenaga T, Fu L, Xing Y, Guo Z, Matsushita T, Hosokawa M, Naiki H, Baba S, Kawata Y, Ikeda S, Ishihara T, Mori M, Higuchi K (April 2004). "Induction of AApoAII amyloidosis by various heterogeneous amyloid fibrils". FEBS Letters. 563 (1–3): 179–84. doi:10.1016/S0014-5793(04)00295-9. PMID 15063745.

- ^ Bolmont T, Clavaguera F, Meyer-Luehmann M, Herzig MC, Radde R, Staufenbiel M, Lewis J, Hutton M, Tolnay M, Jucker M (December 2007). "Induction of tau pathology by intracerebral infusion of amyloid-beta -containing brain extract and by amyloid-beta deposition in APP x Tau transgenic mice". The American Journal of Pathology. 171 (6): 2012–20. doi:10.2353/ajpath.2007.070403. PMC 2111123. PMID 18055549.

- ^ Morales R, Estrada LD, Diaz-Espinoza R, Morales-Scheihing D, Jara MC, Castilla J, Soto C (March 2010). "Molecular cross talk between misfolded proteins in animal models of Alzheimer's and prion diseases". The Journal of Neuroscience. 30 (13): 4528–35. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5924-09.2010. PMC 2859074. PMID 20357103.

- ^ a b c d Revesz T, Ghiso J, Lashley T, Plant G, Rostagno A, Frangione B, Holton JL (September 2003). "Cerebral amyloid angiopathies: a pathologic, biochemical, and genetic view". Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology. 62 (9): 885–98. doi:10.1093/jnen/62.9.885. PMID 14533778.

- ^ Guo L, Salt TE, Luong V, Wood N, Cheung W, Maass A, Ferrari G, Russo-Marie F, Sillito AM, Cheetham ME, Moss SE, Fitzke FW, Cordeiro MF (August 2007). "Targeting amyloid-beta in glaucoma treatment". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 104 (33): 13444–9. Bibcode:2007PNAS..10413444G. doi:10.1073/pnas.0703707104. PMC 1940230. PMID 17684098.

- ^ Prusiner, SB (2004). Prion Biology and Diseases (2 ed.). Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. ISBN 0-87969-693-1.

- ^ Goedert M, Spillantini MG, Del Tredici K, Braak H (January 2013). "100 years of Lewy pathology". Nature Reviews. Neurology. 9 (1): 13–24. doi:10.1038/nrneurol.2012.242. PMID 23183883. S2CID 12590215.

- ^ Clavaguera F, Hench J, Goedert M, Tolnay M (February 2015). "Invited review: Prion-like transmission and spreading of tau pathology". Neuropathology and Applied Neurobiology. 41 (1): 47–58. doi:10.1111/nan.12197. PMID 25399729. S2CID 45101893.

- ^ a b Mann DM, Snowden JS (November 2017). "Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: Pathogenesis, pathology and pathways to phenotype". Brain Pathology. 27 (6): 723–736. doi:10.1111/bpa.12486. PMC 8029341. PMID 28100023.

- ^ Grad LI, Fernando SM, Cashman NR (May 2015). "From molecule to molecule and cell to cell: prion-like mechanisms in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis". Neurobiology of Disease. 77: 257–65. doi:10.1016/j.nbd.2015.02.009. PMID 25701498. S2CID 18510138.

- ^ Ludolph AC, Brettschneider J, Weishaupt JH (October 2012). "Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis". Current Opinion in Neurology. 25 (5): 530–5. doi:10.1097/WCO.0b013e328356d328. PMID 22918486.

- ^ Orr HT, Zoghbi HY (July 2007). "Trinucleotide repeat disorders". Annual Review of Neuroscience. 30 (1): 575–621. doi:10.1146/annurev.neuro.29.051605.113042. PMID 17417937.

- ^ Almeida B, Fernandes S, Abreu IA, Macedo-Ribeiro S (2013). "Trinucleotide repeats: a structural perspective". Frontiers in Neurology. 4: 76. doi:10.3389/fneur.2013.00076. PMC 3687200. PMID 23801983.

- ^ Spinner NB (March 2000). "CADASIL: Notch signaling defect or protein accumulation problem?". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 105 (5): 561–2. doi:10.1172/JCI9511. PMC 292459. PMID 10712425.

- ^ Quinlan RA, Brenner M, Goldman JE, Messing A (June 2007). "GFAP and its role in Alexander disease". Experimental Cell Research. 313 (10): 2077–87. doi:10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.04.004. PMC 2702672. PMID 17498694.

- ^ Ito D, Suzuki N (January 2009). "Seipinopathy: a novel endoplasmic reticulum stress-associated disease". Brain. 132 (Pt 1): 8–15. doi:10.1093/brain/awn216. PMID 18790819.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa Sipe JD, Benson MD, Buxbaum JN, Ikeda SI, Merlini G, Saraiva MJ, Westermark P (December 2016). "Amyloid fibril proteins and amyloidosis: chemical identification and clinical classification International Society of Amyloidosis 2016 Nomenclature Guidelines". Amyloid. 23 (4): 209–213. doi:10.1080/13506129.2016.1257986. PMID 27884064.

- ^ Lomas DA, Carrell RW (October 2002). "Serpinopathies and the conformational dementias". Nature Reviews Genetics. 3 (10): 759–68. doi:10.1038/nrg907. PMID 12360234. S2CID 21633779.

- ^ Mukherjee A, Soto C (May 2017). "Prion-Like Protein Aggregates and Type 2 Diabetes". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine. 7 (5): a024315. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a024315. PMC 5411686. PMID 28159831.

- ^ Askanas V, Engel WK (January 2006). "Inclusion-body myositis: a myodegenerative conformational disorder associated with Abeta, protein misfolding, and proteasome inhibition". Neurology. 66 (2 Suppl 1): S39-48. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000192128.13875.1e. PMID 16432144. S2CID 24365234.

- ^ Ecroyd H, Carver JA (January 2009). "Crystallin proteins and amyloid fibrils". Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 66 (1): 62–81. doi:10.1007/s00018-008-8327-4. PMID 18810322. S2CID 6580402.

- ^ Surguchev A, Surguchov A (January 2010). "Conformational diseases: looking into the eyes". Brain Research Bulletin. 81 (1): 12–24. doi:10.1016/j.brainresbull.2009.09.015. PMID 19808079. S2CID 38832894.

- ^ Huilgol SC, Ramnarain N, Carrington P, Leigh IM, Black MM (May 1998). "Cytokeratins in primary cutaneous amyloidosis". The Australasian Journal of Dermatology. 39 (2): 81–5. doi:10.1111/j.1440-0960.1998.tb01253.x. PMID 9611375. S2CID 25820489.

- ^ Janig E, Stumptner C, Fuchsbichler A, Denk H, Zatloukal K (March 2005). "Interaction of stress proteins with misfolded keratins". European Journal of Cell Biology. 84 (2–3): 329–39. doi:10.1016/j.ejcb.2004.12.018. PMID 15819411.

- ^ D'Souza A, Theis JD, Vrana JA, Dogan A (June 2014). "Pharmaceutical amyloidosis associated with subcutaneous insulin and enfuvirtide administration". Amyloid. 21 (2): 71–5. doi:10.3109/13506129.2013.876984. PMC 4021035. PMID 24446896.

- ^ Meng X, Clews J, Kargas V, Wang X, Ford RC (January 2017). "The cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) and its stability". Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 74 (1): 23–38. doi:10.1007/s00018-016-2386-8. PMC 5209436. PMID 27734094.

- ^ Stuart MJ, Nagel RL (2004). "Sickle-cell disease". Lancet. 364 (9442): 1343–60. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17192-4. PMID 15474138. S2CID 8139305.

- ^ a b c Pepys MB (2006). "Amyloidosis". Annu Rev Med. 57: 223–241. doi:10.1146/annurev.med.57.121304.131243. PMID 16409147.

- ^ a b Holtzman DM, Morris JC, Goate AM (2011). "Alzheimer's disease: the challenge of the second century". Sci Transl Med. 3 (77): 77sr1. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3002369. PMC 3130546. PMID 21471435.

- ^ Pepys MB (2001). "Pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment of systemic amyloidosis". Phil Trans R Soc Lond B. 356 (1406): 203–211. doi:10.1098/rstb.2000.0766. PMC 1088426. PMID 11260801.

- ^ Walker LC, LeVine H 3rd (2002). "Proteopathy: the next therapeutic frontier?". Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 3 (5): 782–7. PMID 12090553.

- ^ Braczynski AK, Schulz JB, Bach JP (2017). "Vaccination strategies in tauopathies and synucleinopathies". J Neurochem. 143 (5): 467–488. doi:10.1111/jnc.14207. PMID 28869766.

- ^ Klein WL (2013). "Synaptotoxic amyloid-β oligomers: a molecular basis for the cause, diagnosis, and treatment of Alzheimer's disease?". J Alzheimers Dis. 33 (Suppl 1): S49-65. doi:10.3233/JAD-2012-129039. PMID 22785404.

- ^ a b c Badar T, D'Souza A, Hari P (2018). "Recent advances in understanding and treating immunoglobulin light chain amyloidosis". F1000Res. 7: 1348. doi:10.12688/f1000research.15353.1. PMC 6117860. PMID 30228867.

- ^ Carvalho A, Rocha A, Lobato L (2015). "Liver transplantation in transthyretin amyloidosis: issues and challenges". Liver Transpl. 21 (3): 282–292. doi:10.1002/lt.24058. PMID 25482846.

- ^ Suhr OB, Herlenius G, Friman S, Ericzon BG (2000). "Liver transplantation for hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis". Liver Transpl. 6 (3): 263–276. doi:10.1053/lv.2000.6145. PMID 10827225.

- ^ a b Suhr OB, Larsson M, Ericzon BG, Wilczek HE, et al. (2016). "Survival After Transplantation in Patients With Mutations Other Than Val30Met: Extracts From the FAP World Transplant Registry". Transplantation. 100 (2): 373–381. doi:10.1097/TP.0000000000001021. PMC 4732012. PMID 26656838.

- ^ Coelho T, et al. (2016). "Mechanism of Action and Clinical Application of Tafamidis in Hereditary Transthyretin Amyloidosis". Neurol Ther. 5 (1): 1–25. doi:10.1007/s40120-016-0040-x. PMC 4919130. PMID 26894299.

- ^ Yu D, et al. (2012). "Single-stranded RNAs use RNAi to potently and allele-selectively inhibit mutant huntingtin expression". Cell. 150 (5): 895–908. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2012.08.002. PMC 3444165. PMID 22939619.

- ^ Nuvolone M, Merlini G (2017). "Emerging therapeutic targets currently under investigation for the treatment of systemic amyloidosis". Expert Opin Ther Targets. 21 (12): 1095–1110. doi:10.1080/14728222.2017.1398235. PMID 29076382. S2CID 46766370.

- ^ Joseph NS, Kaufman JL (2018). "Novel Approaches for the Management of AL Amyloidosis". Curr Hematol Malig Rep. 13 (3): 212–219. doi:10.1007/s11899-018-0450-1. PMID 29951831. S2CID 49475930.