샤를 3세

Charles III| 샤를 3세 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 영연방의 수장 | |||||

2023년 샤를 3세 | |||||

| 영국의 왕 그리고 다른 영연방 국가들[note 1]. | |||||

| 통치 | 2022년 9월 8일 ~ 현재 | ||||

| 대관식 | 2023년 5월 6일 | ||||

| 선대 | 엘리자베스 2세 | ||||

| 상속인 외견상 | 윌리엄 왕세손 | ||||

| 태어난 | 에든버러 공 찰스 1948년 11월 14일 영국 런던 버킹엄 궁 | ||||

| 배우자 | |||||

| 쟁점. 세부 사항 | |||||

| |||||

| 하우스. | 윈저 | ||||

| 아버지. | 에든버러 공작 필립공 | ||||

| 어머니. | 엘리자베스 2세 | ||||

| 종교 | 프로테스탄트[주3] | ||||

| 교육 | 고든스턴 스쿨 | ||||

| 모교 | 케임브리지 트리니티 칼리지 (MA) | ||||

| 군경력 | |||||

| 충성 | 영국 | ||||

| 서비스/지점 | |||||

| 다년간의 현역 복무 | 1971–1976 | ||||

| 순위 | 풀리스트 | ||||

| 보유중인 명령어 | HMS 브로닝턴 | ||||

| 영국왕실 그 밖의 영연방 국가들 |

|---|

|

| |

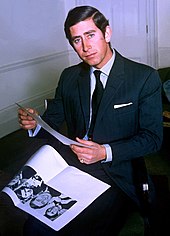

찰스 3세(Charles III, 1948년 11월 14일 ~ )는 영국의 국왕(재위: 14개 영연방)이다.[note 1]

찰스는 외할아버지 조지 6세의 통치 기간 동안 버킹엄 궁에서 태어났고, 그의 어머니 엘리자베스 2세가 1952년 왕위에 올랐을 때 후계자가 되었습니다. 그는 1958년에 웨일즈의 왕자가 되었고 1969년에 그의 투자금이 열렸습니다. 그는 Cheam School과 Gordonstoon에서 교육을 받았고, 나중에 호주 빅토리아에 있는 질롱 그래머 스쿨의 Timbertop 캠퍼스에서 6개월을 보냈습니다. 케임브리지 대학에서 역사 학위를 마친 후, 찰스는 1971년부터 1976년까지 영국 공군과 영국 해군에서 복무했습니다. 1981년, 그는 레이디 다이애나 스펜서와 결혼했습니다. 그들에게는 윌리엄과 해리라는 두 아들이 있었습니다. 찰스와 다이애나는 1996년에 각각 잘 알려진 외도를 한 후에 이혼했습니다. 다이애나는 이듬해 교통사고로 입은 부상으로 사망했습니다. 2005년 찰스는 오랜 파트너였던 카밀라 파커 볼스와 결혼했습니다.

후계자로서 찰스는 어머니를 대신하여 공식적인 업무와 업무를 수행했습니다. 그는 1976년 프린스 트러스트를 설립하고 프린스 자선 단체를 후원했으며 800개 이상의 자선 단체와 단체의 후원자 또는 회장이 되었습니다. 그는 역사적인 건물의 보존과 사회에서 건축의 중요성을 주장했습니다. 그런 맥락에서 그는 실험적인 신도시인 파운드베리를 만들었습니다. 환경운동가인 찰스는 콘월 공국의 관리자로 있는 동안 유기농법과 기후 변화를 막기 위한 행동을 지지하여 그에게 상과 인정을 받았고 비판을 받았습니다; 그는 또한 유전자 변형 식품의 채택에 대한 저명한 비평가입니다. 대체 의학에 대한 그의 지지가 비판을 받는 동안. 그는 17권의 책을 저술하거나 공동 집필했습니다.

찰스는 2022년 어머니의 죽음으로 왕이 되었습니다. 73세의 나이로 그는 영국 역사상 가장 오랜 기간 동안 명백한 상속자이자 웨일즈의 왕자였던 후 영국 왕위에 오른 가장 나이가 많은 사람이었습니다. 그의 통치 기간에 중요한 사건들은 2023년 그의 대관식과 이듬해 암 진단을 포함했고, 후자는 계획된 대중 참여를 일시적으로 중단했습니다.

초기 생활, 가족, 교육

찰스는 외할아버지 조지 6세의 통치 기간인 1948년 11월 14일 21시 14분([2]GMT)에 에든버러 공작부인 엘리자베스 공주(훗날 엘리자베스 2세 여왕)와 에든버러 공작 필립의 첫째 자녀로 태어났습니다.[3] 버킹엄 궁의 제왕절개 수술로 그를 인도했습니다.[4] 그의 부모는 앤(1950년생), 앤드류(1960년생), 에드워드(1964년생) 세 자녀를 더 두었습니다. 1948년 12월 15일, 그는 4주차에 캔터베리 대주교 제프리 피셔에 의해 버킹엄 궁전의 음악실에서 찰스 필립 아서 조지라는 세례명을 받았습니다.[note 4][note 5][8][9]

1952년 2월 6일 조지 6세가 사망하고 찰스의 어머니가 엘리자베스 2세로 즉위하였으며 찰스는 즉시 후계자가 되었습니다. 1337년 에드워드 3세의 헌장에 따라, 군주의 장남으로서, 그는 자동적으로 콘월 공작의 전통적인 직함을 맡았고, 스코틀랜드의 귀족들에게 로테세이 공작, 캐릭 백작, 렌프루 남작, 섬의 영주, 스코틀랜드의 왕자와 위대한 스튜어드라는 직함을 맡았습니다.[10] 이듬해 6월 2일, 찰스는 웨스트민스터 사원에서 어머니의 대관식에 참석했습니다.[11]

찰스가 다섯 살이 되었을 때, 캐서린 피블스라고 알려진 가정교사가 버킹엄 궁에서 그의 교육을 감독하도록 임명되었습니다.[12] 찰스는 1956년 11월 런던 서부에 있는 힐 하우스 학교에서 수업을 시작했습니다.[13] 그는 개인 가정교사에게 교육을 받은 것이 아니라 학교에 다닌 것으로 보이는 첫 번째 상속자였습니다.[14] 그 소년들이 축구장의 그 누구에게도 결코 특혜를 주지 않았기 때문에, 그는 찰스가 축구 훈련을 받도록 여왕에게 조언했던 학교 설립자이자 교장인 스튜어트 타운엔드로부터 특혜를 받지 않았습니다.[15] 찰스는 그 후 아버지의 이전 학교들 중 두 곳을 다녔습니다. 1958년부터 햄프셔에 있는 참 스쿨([13]Cheam School)[16]을 거쳐 1962년 4월 스코틀랜드 북동쪽에 있는 고든스턴(Gordonstoun)을 따라 그곳에서 수업을 시작했습니다.[13][17]

조나단 딤블비가 1994년에 공인한 전기에서 찰스의 부모는 육체적, 감정적으로 멀리 떨어져 있다고 묘사되었고 필립은 찰스가 괴롭힘을 당한 고든스턴에 다니도록 강요하는 것을 포함하여 찰스의 민감한 본성을 무시한 것으로 비난 받았습니다.[18] 찰스는 특히 엄격한 커리큘럼으로 유명한 고든스턴을 "킬트로 된 콜디츠"라고 묘사했다고 알려져 있지만,[16] 나중에 학교가 "나 자신과 나 자신의 능력과 장애에 대해 많은 것을 가르쳐 주었다"고 말하면서 학교를 칭찬했습니다. 그는 1975년 인터뷰에서 고든스턴을 다닌 적이 있다며 "기쁘다"고 말했고, "장소의 질긴 부분"은 "매우 과장됐다"고 말했습니다.[19] 1966년, 찰스는 호주 빅토리아에 있는 질롱 그래머 스쿨의 팀버탑 캠퍼스에서 두 학기를 보냈고, 그 기간 동안 그의 역사 교사인 마이클 콜린스 페르세와 함께 수학 여행으로 파푸아 뉴기니를 방문했습니다.[20][21] 1973년, 찰스는 팀버탑에서의 그의 시간을 그의 전체 교육에서 가장 즐거운 부분이라고 묘사했습니다.[22] 고든스턴으로 돌아온 후, 그는 아버지를 본받아 수석 소년이 되었고, 1967년에 역사학과 프랑스어에서 각각 6개의 GCE O-level과 2개의 A-level을 받으며 각각 B와 C등급을 받았습니다.[20][23] 그의 교육에 대해 찰스는 나중에 "저는 학교를 제가 즐길 수 있는 만큼 즐기지 않았습니다. 그러나 그것은 단지 제가 다른 어떤 것보다 집에서 행복하기 때문입니다."라고 말했습니다.[19]

찰스는 영국군에 입대하는 것이 아니라 A급 이후 곧바로 대학에 진학하면서 왕실의 전통을 깼습니다.[16] 1967년 10월, 그는 케임브리지의 트리니티 칼리지에 입학하여 트라이포스 1부에서 고고학과 인류학을 공부한 후 2부에서 역사학으로 전환했습니다.[8][20][24] 2학년 때, 그는 애버리스트위스에 있는 웨일즈 대학교에 입학하여 한 학기 동안 웨일즈 역사와 웨일즈 언어를 공부했습니다.[20] 찰스는 1970년 6월 케임브리지 대학교에서 2:2 학사(BA) 학위를 받으며 대학 학위를 취득한 최초의 영국 상속인이 되었습니다.[20][25] 표준 실습에 따라 1975년 8월, 그의 예술 학사는 석사(MA Cantab) 학위로 승진했습니다.[20]

프린스 오브 웨일스

찰스는 1958년 7월 26일 웨일스 공(Prince of Wales)[26][28]과 체스터 백작(Earl of Chester)으로 임명되었으나 1969년 7월 1일 카나폰 성(Caernarfon Castle)에서 열린 TV 시상식에서 어머니에 의해 왕위에 오르기 전까지 그의 투자는 진행되지 않았습니다.[27] 1974년[29] 6월 13일, 그는 자신의 처녀 연설을 했는데,[30] 이는 1884년 에드워드 7세 이후 처음으로 의회에서 연설한 왕실 인사였습니다.[31] 그는 1975년에 다시 말을 했습니다.[32]

찰스는 1976년[33] 프린스 트러스트를 설립하고 1981년 미국으로 여행을 떠나 더 많은 공공 업무를 맡기 시작했습니다.[34] 1970년대 중반, 그는 호주 총리 말콤 프레이저의 제안으로 호주 총독직에 관심을 표명했지만, 대중의 열정이 부족했기 때문에 그 제안은 아무것도 나오지 않았습니다.[35] 이에 대해 찰스는 "그래서, 당신은 도움이 되는 일을 할 준비가 되어 있고 단지 당신이 원하지 않는다고 들었을 때 어떻게 생각해야 합니까?"[36]라고 말했습니다.

군사훈련 및 경력

찰스는 영국 공군과 영국 해군에서 복무했습니다. 케임브리지 대학교 2학년 때, 그는 영국 공군 훈련을 받았고, 케임브리지 대학교 항공대와 함께 칩멍크 항공기 조종을 배웠고,[37][38] 1971년 8월 영국 공군 비행대를 받았습니다.[39]

그해 9월 타계식 퍼레이드 이후, 찰스는 해군 경력을 시작했고 왕립 해군 대학 다트머스에서 6주 과정을 등록했습니다. 그 후 1971년부터 1972년까지 유도 미사일 구축함 HMS 노퍽과 호위함 HMS 미네르바에서, 1972년부터 1973년까지, 1974년에는 HMS 목성에서 근무했습니다. 같은 해, 그는 RNAS Yeovilton에서 헬리콥터 조종사 자격을 취득했고, 그 후 HMS Hermes에서 작전하는 845 해군 항공대에 합류했습니다.[40] 찰스는 1976년 2월 9일부터 해안 기뢰 사냥꾼 HMS 브로닝턴을 지휘하며 해군에서 마지막 10개월의 현역 생활을 보냈습니다.[40] 그는 1977년 낙하산 연대의 대령으로 임명된 후 2년 후 RAF Brize Norton에서 낙하산 훈련 과정에 참가했습니다.[41] 찰스는 1994년 비행기를 조종하도록 초대받은 승객으로서 아이슬레이에 BAe 146을 불시착시킨 후 비행을 포기했습니다. 승무원들은 조사위원회에 의해 과실이 있는 것으로 밝혀졌습니다.[42]

관계와 결혼

학사

찰스는 젊은 시절에 많은 여성들과 사랑스럽게 연결되어 있었습니다. 그의 여자 친구로는 스페인 주재 영국 대사였던 존 러셀 경의 딸 조지아나 러셀,[43] 제8대 웰링턴 공작의 딸 제인 웰즐리,[44] 다비나 셰필드,[45] 사라 스펜서 부인,[46] 그리고 나중에 그의 두 번째 부인이 된 카밀라 샨드가 있었습니다.[47]

찰스의 증삼촌인 마운트배튼 경은 찰스에게 "거친 귀리를 뿌리고 정착하기 전에 가능한 한 많은 일을 해야 한다"고 조언했지만, 아내에게는 "그녀가 빠질 수도 있는 다른 사람을 만나기 전에 적합하고 매력적이며 상냥한 성격의 소녀를 선택해야 한다"고 조언했습니다. 결혼 후에도 대좌에 머물러야 한다면 여성들이 경험을 하는 것은 불안한 일입니다."[48] 1974년 초, 마운트배튼은 마운트배튼의 손녀인 아만다 크나치불과의 결혼 가능성에 대해 25세의 찰스와 서신을 주고받기 시작했습니다.[49] 찰스는 아만다의 어머니이자 그의 대모이기도 한 레이디 브래번에게 그녀의 딸에 대한 관심을 표현하는 편지를 썼습니다. 브래번 부인은 인정하는 듯 대답했지만, 16세와의 구애는 시기상조라고 말했습니다.[50] 4년 후 마운트배튼은 아만다와 그 자신이 1980년 찰스의 인도 방문에 동행하도록 주선했습니다. 그러나 두 아버지 모두 반대했습니다; 필립공은 그의 유명한 삼촌이[note 6] 찰스를 이길 것을 두려워했고, 브래번 경은 부부가 되기로 결정하기 전에 공동 방문이 사촌들에게 언론의 관심을 집중시킬 것이라고 경고했습니다.[51]

1979년 8월, 찰스가 인도로 혼자 출발하기 전, 마운트배튼은 아일랜드 공화국군에 의해 암살당했습니다. 찰스가 돌아왔을 때, 그는 아만다에게 청혼했습니다. 그러나 그녀는 할아버지 외에도 폭탄 공격으로 친할머니와 남동생을 잃고 이제 왕실에 합류하는 것을 꺼렸습니다.[51]

레이디 다이애나 스펜서

찰스는 1977년 레이디 다이애나 스펜서를 처음 만났습니다. 그는 당시 그녀의 언니 사라의 동반자였으며 1980년 중반까지 다이애나를 로맨틱하게 생각하지 않았습니다. 찰스와 다이애나가 지난 7월 한 친구의 바비큐 파티에서 건초 더미 위에 함께 앉아 있는 동안, 그녀는 그가 외삼촌인 마운트배튼 경의 장례식에서 외롭고 보살핌이 필요한 사람을 찾았다고 언급했습니다. 곧, 딤블비에 따르면, "어떤 뚜렷한 감정의 급증 없이, 그는 그녀를 잠재적인 신부로 진지하게 생각하기 시작했습니다" 그리고 그녀는 발모랄 성과 샌드링엄 하우스를 방문하는 데 찰스와 동행했습니다.[52]

찰스의 사촌 노튼 캣치불과 그의 아내는 다이애나가 그의 입장에 충격을 받은 것 같으며 그가 그녀를 사랑하고 있는 것 같지 않다고 찰스에게 말했습니다.[53] 한편, 부부의 계속된 구애는 언론과 파파라치들의 집중적인 관심을 끌었습니다. 필립이 그에게 만약 찰스가 그녀와 곧 결혼하는 것에 대한 결정을 내리지 않고 그녀가 (마운트배튼의 기준에 따라) 적합한 왕실 신부라는 것을 깨닫는다면 언론의 추측이 다이애나의 명성을 손상시킬 것이라고 말했을 때, 찰스는 그의 아버지의 충고를 더 이상 지체하지 말고 진행하라는 경고로 해석했습니다.[54] 그는 1981년 2월 다이애나에게 청혼을 했고, 2월 24일 그들의 약혼이 공식화되었고, 결혼식은 7월 29일 성 바오로 대성당에서 열렸습니다. 결혼과 동시에 찰스는 콘월 공국의 이익에서 자발적인 세금 기여를 50%에서 25%로 줄였습니다.[55] 이 부부는 테트베리 근처 켄싱턴 궁과 하이그로브 하우스에서 살았고, 1982년 윌리엄과 1984년 해리라는 두 아이를 낳았습니다.[14]

5년 만에 부부의 위화감과 13살 가까운 나이 차이로 결혼 생활에 어려움을 겪었습니다.[56][57] 1986년 11월, 찰스는 카밀라 파커 볼스와의 관계를 완전히 재개했습니다.[58] 1992년 피터 세텔렌(Peter Settelen)이 녹음한 비디오테이프에서 다이애나는 자신이 "이 환경에서 일했던 사람과 깊은 사랑에 빠졌다"고 인정했습니다.[59][60] 1986년 외교 보호단으로 전출된 배리 매너키를 가리킨 것으로 추정되는데,[61] 그의 매니저는 다이애나와의 관계가 부적절하다고 판단했습니다.[60][62] 다이애나는 나중에 가족의 전 승마 강사인 제임스 휴이트 소령과 관계를 시작했습니다.[63]

찰스와 다이애나가 서로의 회사에서 느끼는 불편함은 그들을 언론에 의해 "The Glums"라고 불리게 만들었습니다.[64] 다이애나는 앤드류 모튼의 책에서 찰스와 파커 볼스의 외도를 폭로했습니다. 그녀의 실화. 휴이트와 해리 왕자의 신체적 유사성을 바탕으로 휴이트가 해리 왕자의 아버지라는 지속적인 제안과 함께,[64] 그녀 자신의 혼외 바람기에 대한 오디오 테이프도 등장했습니다. 하지만, 해리는 다이애나가 휴이트와 바람을 피우기 시작했을 때 이미 태어난 상태였습니다.[65]

1992년 12월, 존 메이저는 하원에서 부부의 법적 별거를 발표했습니다. 이듬해 초, 영국 언론은 1989년 찰스와 파커 볼스 사이의 열정적이고 도청된 전화 대화의 녹취록을 발표했는데, 이 대화는 "카밀라게이트"와 "탐퐁게이트"로 불렸습니다.[66] 찰스는 이후 딤블비, 찰스와 함께 텔레비전 영화에서 대중의 이해를 구했습니다. 1994년 6월 방송된 '이등병, 공공 역할'. 영화 인터뷰에서 찰스는 파커 볼스와 자신의 외도를 확인하면서 다이애나와의 결혼이 "회복할 수 없을 정도로 무너졌던" 후에야 1986년에 그들의 교제를 다시 시작했다고 말했습니다.[67][68] 그 후 다이애나 자신이 1995년 11월 방송된 BBC 시사 프로그램 파노라마의 인터뷰에서 부부 문제를 인정했습니다.[69] 그녀는 찰스와 파커 볼스의 관계를 언급하며 "음, 이 결혼에는 우리 세 명이 있었습니다. 그래서, 사람들이 좀 붐볐습니다." 그녀는 남편의 왕권 적합성에 대해서도 의구심을 나타냈습니다.[70] 찰스와 다이애나는 1995년 12월 여왕으로부터 결혼을 끝내라는 충고를 받은 후 1996년 8월 28일 이혼했습니다.[71][72] 그 부부는 아이들의 양육권을 공유했습니다.[73]

다이애나는 1997년 8월 31일 파리에서 자동차 사고로 사망했습니다. 찰스는 다이애나의 시신과 함께 영국으로 돌아가기 위해 그녀의 여동생들과 함께 파리로 날아갔습니다.[74] 2003년 다이애나의 집사 폴 버렐은 1995년 다이애나가 작성한 것이라고 주장하는 메모를 발표했는데, 이 메모에는 찰스가 재혼할 수 있도록 "다이애나의 차 안에서 '사고'를 계획하고 있었다"는 주장이 있었습니다.[75] 패젯 작전의 일환으로 메트로폴리탄 경찰 조사팀의 질문을 받았을 때 찰스는 1995년 전 부인의 쪽지에 대해 몰랐으며 왜 그런 감정을 가졌는지 이해할 수 없다고 당국에 말했습니다.[76]

카밀라 파커 볼스

2005년 2월 10일, 프린스 오브 웨일스와 카밀라 파커 볼스의 약혼이 발표되었습니다.[77] 1772년 왕실 혼인법에 의해 요구된 결혼에 대한 여왕의 동의는 3월 2일 추밀원 회의에서 기록되었습니다.[78] 캐나다에서 법무부는 캐나다 여왕 추밀원의 동의가 필요하지 않다고 판단했는데, 이는 캐나다 연합이 캐나다 왕위 계승자를 배출하지 않기 때문입니다.[79]

찰스는 영국에서 교회가 아닌 시민 결혼식을 올린 유일한 왕족이었습니다. BBC에 의해 발행된 1950년대와 1960년대의 영국 정부 문서들은 그러한 결혼이 불법이라고 진술했습니다; 이러한 주장들은 찰스의 대변인에[80] 의해 기각되었고 현직 정부에 의해 1953년 등록 서비스법에 의해 폐지되었다고 설명되었습니다.[81]

그 연합은 윈저 성에서 시민 의식으로 열릴 예정이었고, 그 후 성 조지 예배당에서 종교적인 축복이 있을 예정이었습니다. 결혼식 장소는 윈저 성에서 시민 결혼을 하면 결혼을 원하는 사람은 누구나 결혼식장을 이용할 수 있다는 사실이 알려지면서 윈저 길드홀로 변경되었습니다. 행사가 열리기 4일 전, 샤를과 초대된 고위 인사들 중 일부가 교황 요한 바오로 2세의 장례식에 참석할 수 있도록 하기 위해 원래 예정된 날짜인 4월 8일에서 다음날로 연기되었습니다.[82]

찰스의 부모는 결혼식에 참석하지 않았습니다. 여왕이 결혼식에 참석하기를 꺼려한 것은 아마도 그녀가 잉글랜드 교회의 최고 통치자라는 위치에서 비롯되었을 것입니다.[83] 여왕과 에든버러 공작은 축복의 예배에 참석했고 윈저 성에서 신혼부부를 위한 피로연을 열었습니다.[84] 로완 윌리엄스 캔터베리 대주교의 축복이 텔레비전에 방영되었습니다.[85]

공무

1965년 찰스는 홀리루드하우스 궁전에서 열린 학생 정원 파티에 참석함으로써 그의 첫 번째 공공 참여를 시작했습니다.[86] 왕세자 시절인 2002년부터 2022년까지 10,934회의 약혼을 [87]성사시키며 여왕을 대신해 공식적인 임무를 수행했습니다.[88] 그는 투자 업무를 맡았고 외국 고위 관리들의 장례식에 참석했습니다.[89] 찰스는 웨일스를 정기적으로 순회하며 매년 여름 1주일간의 일정을 소화했고, 세네드를 여는 것과 같은 중요한 국가 행사에 참석했습니다.[90] 왕실 소장 신탁의 6명의 신탁 관리인은 그의 회장직 아래 1년에 세 번 만났습니다.[91] 찰스는 또한 1970년 피지,[92] 1973년 바하마,[93] 1975년 파푸아 뉴기니,[94] 1980년 짐바브웨,[95] 그리고 1984년 브루나이에서 열린 독립 기념 행사에 그의 어머니를 대표했습니다.[96]

1983년, 1981년 여왕에게 .22 소총을 발사했던 크리스토퍼 존 루이스는 다이애나, 윌리엄과 함께 뉴질랜드를 방문하고 있던 찰스를 암살하기 위해 정신 병원을 탈출하려고 시도했습니다.[97] 1994년 1월 호주의 날에 찰스가 호주를 방문하는 동안 데이비드 강은 수용소에 수감된 수백 명의 캄보디아 망명 신청자들의 치료에 항의하기 위해 시동 권총에서 그에게 두 발을 발사했습니다.[98] 1995년 찰스는 공식 자격으로 아일랜드 공화국을 방문한 최초의 왕족이 되었습니다.[99] 1997년, 찰스는 홍콩 반환식에서 여왕을 대표했습니다.[100][101]

1998년 3월 찰스는 오른쪽 무릎에 레이저 열쇠 구멍 수술을 받았습니다.[102] 2003년 3월, 그는 탈장 부상을 치료하기 위해 킹 에드워드 7세 병원에서 수술을 받았습니다.[103] 2005년 교황 요한 바오로 2세의 장례식에서 옆자리에 앉은 로버트 무가베 짐바브웨 대통령과 악수를 해 물의를 빚었습니다. 찰스의 사무실은 그가 무가베의 손을 흔드는 것을 피할 수 없었다며 "현재 짐바브웨 정권이 혐오스럽다고 생각한다"는 성명을 발표했습니다.[104] 2008년에 그의 비강 다리에서 암이 아닌 성장이 제거되었습니다.[102]

찰스는 인도 델리에서 열린 2010 코먼웰스 게임 개막식에서 여왕을 대표했습니다.[105] 2010년 11월, 그와 카밀라는 그들의 차가 시위자들에 의해 공격을 받았을 때 간접적으로 학생 시위에 참여했습니다.[106] 2013년 11월, 그는 스리랑카 콜롬보에서 열린 영연방 정부 수반 회의에서 처음으로 여왕을 대표했습니다.[107]

찰스와 카밀라는 2015년 5월 아일랜드 공화국으로 첫 공동 여행을 떠났습니다. 이 여행은 영국 대사관에 의해 "평화와 화해를 촉진하는" 중요한 단계라고 불렸습니다.[108] 여행 중 찰스는 골웨이에서 1979년 마운트배튼 경을 암살한 무장단체인 IRA의 지도자로 널리 알려진 신페인당의 지도자 게리 애덤스와 악수를 나눴습니다. 언론은 이 사건을 "역사적인 악수"이자 "영-아일랜드 관계의 중요한 순간"이라고 표현했습니다.[109]

영연방 정부 수반들은 2018년 회의에서 찰스가 여왕 다음으로 영연방의 수반이 될 것이라고 결정했습니다.[110] 머리는 선택되어 있기 때문에 세습되지 않습니다.[111] 2019년 3월, 영국 정부의 요청에 따라 찰스와 카밀라는 쿠바를 공식 방문하여 영국 왕실 최초로 쿠바를 방문했습니다. 이번 투어는 쿠바와 영국 사이에 더 긴밀한 관계를 형성하기 위한 노력으로 여겨졌습니다.[112]

찰스는 2020년 3월 팬데믹 기간 동안 코로나19에 감염되었습니다.[113][114] 많은 NHS 의사, 간호사, 환자들이 신속하게 검사를 받을 수 없는 상황에서 찰스와 카밀라가 신속하게 검사를 받은 것에 대해 몇몇 신문들은 비판적이었습니다.[115] 2022년 2월 코로나19 양성 판정을 두 번째로 받았습니다.[116] 양성 반응을 보인 그와 카밀라는 2021년 2월 코로나19 백신을 접종했습니다.[117]

찰스는 2021년 11월 바베이도스의 의회 공화국으로의 전환을 기념하기 위해 바베이도스의 군주직을 폐지하는 기념식에 참석했습니다.[118] 그는 미래의 영연방 수장으로 Mia Mottley 총리에 의해 초대되었습니다.[119] 그것은 왕국이 공화국으로 이행하는 것에 왕실의 일원이 참석한 최초의 일이었습니다.[120] 이듬해 5월 찰스는 영국 의회의 개회식에 참석하여 어머니를 대신하여 여왕의 연설을 했습니다.[121]

통치

찰스는 2022년 9월 8일 어머니의 사망으로 영국 왕위에 올랐습니다. 그는 2011년 4월 20일 에드워드 7세의 59년 기록을 넘어선 영국의 최장수 상속자였습니다.[122] 찰스는 73세의 나이로 영국 왕위를 계승한 최고령자였습니다. 이전 기록 보유자인 윌리엄 4세는 1830년 왕이 되었을 때 64세였습니다.[123]

찰스는 9월 9일 오후 6시에 그의 첫 번째 대국민 연설을 했는데, 그는 어머니에게 경의를 표하고 그의 큰 아들 윌리엄을 웨일즈의 왕자로 임명한다고 발표했습니다.[124] 다음 날, 즉위 평의회는 찰스를 왕으로 공표했고, 이 의식은 처음으로 TV로 중계되었습니다.[125][110] 참석자들은 카밀라 여왕, 윌리엄 왕자, 그리고 리즈 트러스 영국 총리와 살아있는 여섯 명의 전임자들을 포함했습니다.[126] 이 선언문은 또한 영국 전역의 지방 당국에 의해 읽혔습니다. 스코틀랜드, 웨일즈, 북아일랜드, 영국 해외 영토, 크라운 종속국, 캐나다 지방 및 호주 주와 마찬가지로 다른 영역에서도 자체 선언문에 서명하고 읽었습니다.[127]

찰스와 카밀라의 대관식은 2023년 5월 6일 웨스트민스터 사원에서 열렸습니다.[128] 골든 오브 작전이라는 암호명으로 여러 해 동안 계획이 세워졌습니다.[129][130] 즉위 전의 보도에 따르면 찰스의 대관식은 1953년 어머니의 대관식보다 더 간단할 것이며,[131] "현대 영국의 민족적 다양성을 반영하려는 국왕의 바람에 따라 더 짧고, 더 작고, 더 비싸지 않으며, 더 많은 다른 신앙과 공동체 집단을 대표할 것"으로 예상됩니다.[132] 그럼에도 불구하고 대관식은 대관식 선서, 임명, 오브 전달, 즉위식 등 잉글랜드 교회의 의례였습니다.[133] 7월에 그들은 찰스가 성 자일스 대성당에서 스코틀랜드의 명예를 수여받은 국가적인 감사예배에 참석했습니다.[134]

찰스와 카밀라는 세 차례 국빈 방문을 했고 두 차례 국빈 방문을 받았습니다. 2022년 11월, 그들은 찰스의 통치 기간 중 첫 공식적인 영국 국빈 방문 동안 남아프리카 공화국 대통령 시릴 라마포사를 주최했습니다.[135] 이듬해 3월, 국왕과 여왕은 독일을 국빈 방문하기 시작했고, 찰스는 연방 하원에서 연설한 최초의 영국 군주가 되었습니다.[136] 마찬가지로, 9월에 그는 프랑스를 국빈 방문하는 동안 프랑스 상원에서 연설을 한 최초의 영국 군주가 되었습니다.[137] 다음 달, 국왕은 케냐를 방문하여 영국의 식민지 행동에 대해 사과하라는 압력에 직면했습니다. 국빈 연찬회 연설에서 그는 "혐오스럽고 정당하지 못한 폭력 행위"를 인정했지만 공식적으로 사과하지는 않았습니다.[138]

2024년 1월, 찰스는 양성 전립선 비대증을 치료하기 위해 런던 클리닉에서 "시정 절차"를 받았으며, 이로 인해 일부 공개 약속이 연기되었습니다.[139] 지난 2월 버킹엄궁은 치료 과정에서 암이 발견됐지만 전립선암은 아니라고 발표했습니다. 비록 그의 공적인 의무가 연기되었지만, 찰스는 그의 외래 치료 동안 그의 헌법적인 기능을 계속 수행할 것이라고 보도되었습니다.[140] 그는 암 자선단체에 대한 지지를 지지하며 완전한 회복을 위해 "긍정적인 입장을 견지하고 있다"는 성명을 발표했습니다.[141] 3월, 카밀라는 웨스트민스터 사원에서 열린 영연방의 날 예배와 우스터 대성당의 로열 맨디에서 그의 부재를 대신했습니다.[142][143] 그는 31일 윈저성 세인트 조지 예배당에서 열린 부활절 예배에서 암 진단 이후 처음으로 대중 앞에 모습을 드러냈습니다.[144]

자선과 자선

1976년 해군 퇴직금 7,500파운드를 사용하여 프린스 트러스트를 설립한 이후,[145] 찰스는 16개의 자선 단체를 더 설립했고 현재 각각의 회장직을 맡고 있습니다.[146][87] 그들은 함께 느슨한 연합체인 프린스 자선 단체를 결성하는데, 이 단체는 스스로를 "영국에서 가장 큰 다방면의 자선 사업으로 매년 1억 파운드 이상을 모금합니다..."라고 표현합니다. 교육 및 청년, 환경 지속 가능성, 건설 환경, 책임 있는 비즈니스 및 기업, 국제 등 광범위한 영역에서 활동하고 있습니다."[146] 웨일즈의 왕자로서 찰스는 800개가 넘는 자선단체와 단체의 후원자 또는 회장이 되었습니다.[86]

The Prince's Charities Canada는 영국의 이름과 비슷한 방식으로 2010년에 설립되었습니다.[147] 찰스는 청소년, 장애인, 환경, 예술, 의학, 노인, 유산 보호 및 교육에 관심을 끄는 데 도움이 되는 방법으로 캐나다 여행을 사용합니다.[148] 그는 또한 호주 및 국제 자선 활동을 위한 조정적인 자리를 제공하기 위해 멜버른에 기반을 둔 프린스 자선 호주를 설립했습니다.[149]

찰스는 인도주의적인 프로젝트를 지지해 왔습니다. 예를 들어, 그와 그의 아들들은 1998년 세계 인종 차별 철폐의 날 기념식에 참여했습니다.[148] 찰스는 루마니아 독재자 니콜라에 차우 ș에스쿠의 인권 기록에 대해 강한 우려를 표명한 최초의 공인 중 한 명으로, 국제 무대에서 이의를 제기했으며, 이후 루마니아 고아 및 버려진 아이들을 위한 자선 단체인 FARA 재단을 지원했습니다.

기부금 조사

찰스의 자선단체 중 두 곳인 프린스 재단과 프린스 오브 웨일즈 자선기금(나중에 킹스 재단과 킹 찰스 3세 자선기금으로 개명)은 2021년과 2022년에 언론이 부적절하다고 판단한 기부금을 받았다는 이유로 조사를 받았습니다. 2021년 8월, 프린스 재단은 찰스의 지원을 [152]받아 보고서에 대한 조사를 시작한다고 발표했습니다.[153] 자선위원회는 또한 왕자의 재단을 위한 기부금이 대신 마푸즈 재단으로 보내졌다는 의혹에 대한 조사에 착수했습니다.[154] 2022년 2월, 경시청은 재단과 관련된 금품수수 의혹에 대한 수사에 착수했고,[155] 10월에 증거자료를 검찰청에 넘겨 심의를 받았습니다.[156] 2023년 8월, 경시청은 수사를 종결했으며 더 이상의 조치는 취하지 않을 것이라고 발표했습니다.[157]

The Times는 2011년에서 2015년 사이에 샤를이 카타르 총리 하마드 빈 자심 빈 자베르 알 타니로부터 300만 유로의 현금을 받았다고 2022년 6월에 보도했습니다.[158][159] 자선위원회는 정보를[160] 검토하겠다고 밝혔고 2022년 7월 추가 조사가 없을 것이라고 발표했지만, 지불이 불법적이거나 자선단체에 돈을 전달하기 위한 것이 아니라는 증거는 없었습니다.[159][161] 같은 달, The Times는 Prince of Wales의 자선 기금이 2013년 사적인 모임에서 오사마 빈 라덴의 이복 형제인 Bakr bin Laden과 Shafiq bin Laden으로부터 100만 파운드의 기부금을 받았다고 보도했습니다.[162][163] 자선위원회는 기부금을 받기로 한 결정에 대해 "수탁자를 위한 문제"라고 설명하고 조사가 필요하지 않다고 덧붙였습니다.[164]

개인적 이익

찰스는 젊은 성인이 될 때부터 원주민의 목소리에 대한 이해를 장려하면서 토지 보존, 공동체와 공유 가치 존중, 갈등 해결, 과거의 부정성을 인식하고 개선하는 데 중요한 메시지를 가지고 있다고 주장했습니다.[165] 찰스는 기후 변화에 반대하는 자신의 노력과 [166]원주민과 비원주민 간의 화해, 캐나다에서의 자선 사업으로 이러한 견해를 축소했습니다.[167][168] 2022년 CHOGM에서 여왕을 대표하던 찰스는 대영제국의 노예제 역사를 다루는 사례로 화해 과정을 제기했고,[169] 그에 대한 슬픔을 표현했습니다.[170]

찰스가 2004년과 2005년에 정부 장관들에게 보낸 편지들은, 소위 검은 거미 메모라고 불리는, 다양한 정책 문제들에 대한 그의 우려를 표현하는 편지들은, 가디언 신문이 2000년 정보 자유법에 따라 그 편지들을 공개하도록 이의를 제기한 후, 잠재적인 당혹감을 나타냈습니다. 2015년 3월, 영국 대법원은 찰스의 편지를 공개해야 한다고 결정했습니다.[171] 내각부는 2015년 5월에 그 편지들을 출판했습니다.[172] 이 반응은 찰스에 대한 비판이 거의 없이 대체로 찰스를 지지했습니다.[173] 언론은 메모를 "무력한"[174] "무해한" 것으로 다양하게 묘사했고,[175] 그들의 석방이 "그를 경시하려는 사람들에게 역효과를 초래했다"고 결론지었습니다.[176] 같은 해 찰스가 기밀 내각 문서에 접근할 수 있다는 사실이 밝혀졌습니다.[177]

2020년 10월, 1975년 커가 고프 휘틀람 총리를 해임한 후 찰스가 호주 총독 존 커 경에게 보낸 편지는 호주 헌법 위기에 관한 궁정 편지 모음의 일부로 공개되었습니다.[178] 편지에서 찰스는 커의 결정을 지지하며 커가 "작년에 한 일은 옳았고 용기 있는 일"이라고 썼습니다.[178]

2022년 6월 더 타임스는 찰스가 영국 정부의 르완다 망명 계획을 사적으로 '어안이 된다'고 표현했으며, 같은 달 르완다에서 열리는 영연방 정부 수반 회의가 무색해질 것을 우려했다고 보도했습니다.[179] 이후 각료들이 찰스가 왕이 되면 계속해서 이런 발언을 할 경우 헌법상 위기가 발생할 수 있다고 우려해 정치적 발언을 하지 말라고 경고했다는 주장이 나왔습니다.[180]

빌트 환경

찰스는 건축과 도시 계획에 대한 그의 견해를 공개적으로 표명했습니다; 그는 뉴클래식 건축의 발전을 촉진했고 그는 "환경, 건축, 도심 재생, 그리고 삶의 질과 같은 문제들에 깊이 관심을 갖고 있다"고 주장했습니다.[181] 1984년 5월 영국 왕립 건축 협회 150주년 기념 연설에서 그는 런던의 국립 갤러리에 제안된 확장 공사를 "많은 사랑을 받는 친구의 얼굴에 있는 괴물 같은 탄소 덩어리"라고 묘사하고 현대 건축의 "유리 그루터기와 콘크리트 탑"을 개탄했습니다.[182] Charles는 건축적 선택에 지역사회가 참여할 것을 요구하며 "왜 모든 것이 수직적이고, 직선적이고, 구부러지지 않고, 직각으로만 기능해야 합니까?"[182]라고 물었습니다. 찰스는 "이슬람 예술과 건축에 대한 깊은 이해"를 가지고 있으며, 이슬람 양식과 옥스퍼드 건축 양식을 결합한 옥스퍼드 이슬람 연구 센터의 건물과 정원 건설에 참여해 왔습니다.[183]

1989년 찰스의 책 "A Vision of Britain"에서, 그리고 연설과 에세이에서, 그는 전통적인 디자인과 방법이 현대적인 것들을 인도해야 한다고 주장하면서 현대 건축에 비판적이었습니다.[184] 그는 언론의 비판에도 불구하고 전통적인 도시주의, 인간 규모, 역사적인 건물의 복원, 그리고 지속 가능한 디자인을[185] 위한 캠페인을 계속해왔습니다.[186] 그의 자선단체 중 두 곳인 프린스 재생 신탁과 나중에 하나의 자선단체로 합병된 프린스 건축 공동체를 위한 프린스 재단은 그의 견해를 홍보합니다. 파운드베리 마을은 콘월 공국이 소유한 땅에 찰스의 지도 아래, 그리고 그의 철학에 따라 레온 크리에의 마스터 플랜에 따라 지어졌습니다.[181] 2013년, 난슬단 교외 지역의 개발은 찰스의 승인으로 콘월 공국의 사유지에서 시작되었습니다.[187] 찰스는 2007년 Dumfries House와 18세기 가구 컬렉션을 구입하는 데 도움을 주었고, 자선 신탁에서 2천만 파운드를 대출받아 4천 5백만 파운드의 비용을 지불했습니다.[188] 집과 정원은 프린스 재단의 재산으로 남아 있으며 박물관, 커뮤니티 및 기술 교육 센터 역할을 합니다.[189][190] 이것은 "스코틀랜드 파운드베리"라고 불리는 노크룬의 개발로 이어졌습니다.[191][192]

1996년에 많은 캐나다의 역사적인 도시 중심지들의 억제되지 않은 파괴를 한탄한 후, 찰스는 2007년 연방 예산 통과와 함께 시행된 계획인 영국의 내셔널 트러스트를 모델로 한 신탁을 만들기 위해 캐나다 유산부에 그의 도움을 제공했습니다.[193] 1999년 찰스는 자신의 칭호를 캐나다 국립 신탁이 역사적 장소의 보존에 헌신한 지방 정부에게 수여하는 지방 유산 리더십을 위한 웨일즈의 왕자 상에 사용하는 것에 동의했습니다.[194]

미국을 방문하여 허리케인 카트리나로 인한 피해를 조사하는 동안 찰스는 건축과 관련된 노력으로 2005년 국립 건축 박물관의 빈센트 스컬리 상을 받았습니다. 그는 상금 중 2만 5천 달러를 폭풍 피해를 입은 지역 사회를 복구하는 데 기부했습니다.[195] New Classical Architecture의 후원자로서의 그의 업적으로, Charles는 Notre Dame 대학으로부터 2012 Driehaus Architecture Prize를 수상했습니다.[196] The Worshipful Company of Carpents는 "런던의 건축에 대한 그의 관심을 인정하여" 찰스를 명예 리버맨으로 임명했습니다.[197]

찰스는 때때로 모더니즘과 기능주의와 같은 건축 양식을 사용하는 프로젝트에 개입했습니다.[198][199] 2009년, 찰스는 첼시 병영 부지 재개발의 재정가인 카타르 왕실에 편지를 보내 로저스 경의 부지 디자인을 "부적절하다"고 평가했습니다. 로저스는 찰스가 로열 오페라 하우스와 패터노스터 광장에 대한 자신의 디자인을 막기 위해 개입하기도 했다고 주장했습니다.[200] 프로젝트 개발사인 CPC그룹은 카타리 디아르를 상대로 고등법원에 소송을 제기했습니다.[201] 소송이 해결된 후 CPC 그룹은 찰스에게 "소송 과정에서 발생한 모든 위법 행위에 대해" 사과했습니다.[201]

자연환경

1970년대부터 찰스는 환경에 대한 인식을 증진시켜 왔습니다.[202] 그는 21세에 웨일스 시골 위원회 위원장 자격으로 환경 문제에 대한 첫 번째 연설을 했습니다.[203] 열렬한 정원사인 찰스는 또한 식물과 대화하는 것의 중요성을 강조하며 "저는 행복하게 식물과 나무와 이야기하고 그들의 말을 듣습니다. 절대적으로 중요하다고 생각합니다."[204] 정원 가꾸기에 대한 그의 관심은 1980년 하이그로브 사유지를 인수하면서 시작되었습니다.[205] 신성한 기하학과 고대 종교적 상징성을 바탕으로 한 그의 "치유의 정원"은 2002년 첼시 플라워 쇼(Chelsea Flower Show)에서 전시되었습니다.[205]

하이그로브 하우스로 이사하면서 찰스는 유기농에 대한 관심을 갖게 되었고, 이는 1990년 자신의 유기농 브랜드인 공국 오리지널스를 출시하면서 절정에 이르렀으며,[206] 이 브랜드는 지속 가능하게 생산되는 200가지 이상의 제품을 판매하고 수익금(2010년까지 600만 파운드 이상)은 프린스 자선 단체에 기부됩니다.[206][207] 찰스는 농업과 그 안의 다양한 산업에 관여하게 되었고, 정기적으로 농부들과 만나 그들의 무역에 대해 논의했습니다. 이 관행에 대한 저명한 비평가인 [208]찰스는 또한 GM 작물의 사용에 반대하는 입장을 밝혔고, 1998년 토니 블레어에게 보낸 편지에서 찰스는 유전자 변형 식품의 개발을 비판했습니다.[209]

지속 가능성을 모든 활동의 중심에 두도록 장려하는 프로젝트인 지속 가능한 시장 이니셔티브는 찰스가 2020년 1월 다보스에서 열린 세계경제포럼 연차총회에서 시작했습니다.[210] 동년 5월 동 이니셔티브와 세계경제포럼은 COVID-19 대유행으로 인한 세계적 불황에 따른 지속가능한 경제성장을 제고하기 위한 5개 항의 계획인 Great Reset 프로젝트를 시작했습니다.[211]

일찍이 1985년에 찰스는 육류 소비에 의문을 제기했습니다. 1985년 로열 스페셜 텔레비전 프로그램에서 그는 진행자 알라스테어 버넷에게 "저는 사실 예전만큼 고기를 먹지 않습니다. 생선을 더 많이 먹습니다." 그는 또한 고기를 먹는 것은 의문의 여지가 없지만 고기를 적게 먹는 것은 "모든 지옥이 무너지는 것 같다"는 사회적 이중 기준을 지적했습니다.[212] 2021년 찰스는 BBC와 환경에 대해 이야기하면서 일주일에 이틀은 고기와 생선을 먹지 않고 일주일에 하루는 유제품을 먹지 않는다고 밝혔습니다.[213] 2022년에는 과일 샐러드, 씨앗, 차로 아침 식사를 하는 것으로 알려졌습니다. 점심은 먹지 않고 오후 5시에 차를 마시다가 8시 30분에 저녁을 먹고 자정이나 그 이후까지 회사에 복귀합니다.[214] 2022년 크리스마스 저녁 식사를 앞두고 찰스는 동물 보호 단체 PETA에 푸아그라가 어떤 왕실 거주지에서도 제공되지 않을 것이라고 확인했습니다. 그는 왕이 되기 전 10년 이상 자신의 소유지에서 푸아그라 사용을 중단했습니다.[215] 2023년 9월 베르사유 궁전에서 열린 국빈 만찬에서 찰스는 푸아그라나 제철이 지난 아스파라거스를 메뉴에 원하지 않았다고 보고되었습니다. 대신 랍스터가 나왔습니다. 찰스는 초콜릿, 커피, 마늘을 좋아하지 않습니다.[216]

찰스의 대관식에서 사용된 성스러운 크리스 오일은 올리브, 참깨, 장미, 재스민, 계피, 네롤리, 벤조인의 오일과 호박, 오렌지 꽃으로 만들어졌습니다. 그의 어머니의 크리스 오일에는 동물성 오일이 함유되어 있었습니다.[217]

찰스는 2021년 G20 로마 정상회의에서 연설을 통해 COP26을 기후 변화를 방지하기 위한 "마지막 기회의 살롱"으로 묘사하고 녹색 주도의 지속 가능한 경제로 이어질 수 있는 조치를 요청했습니다.[218] COP26 개막식 연설에서 그는 기후 변화에 대처하기 위해 "세계 민간 부문의 힘을 결집하기 위해" "광대한 군사적 방식의 캠페인"이 필요하다고 말하면서 전년도의 감정을 되풀이했습니다.[219] 2022년, 언론은 리즈 트러스가 찰스에게 COP27에 참석하지 말라고 조언했고, 그가 동의했다고 주장했습니다.[220] 찰스는 COP28에서 개회사를 하면서 "COP28이 진정한 변혁적 행동을 향한 중대한 전환점이 되기를 진심으로 기도했다"고 말했습니다.[221]

캠브리지 지속가능 리더십 연구소의 후원자인 찰스는 2022년 3월 캠브리지 대학, 토론토 대학, 멜버른 대학, 맥마스터 대학 및 몬트리올 대학과 협력하여 작은 섬 국가의 학생들을 위한 기후 행동 장학금을 소개했습니다.[222] 2010년에 그는 "자신감 있고, 견고하며, 지속 가능한 농업 및 농촌 공동체"를 목표로 하는 자선 단체인 The Prince's Countrys Fund (2023년에 The Royal Country Fund로 개명)에 자금을 지원했습니다.[223]

대체의학

찰스는 동종 요법을 포함한 대체 의학을 논쟁적으로 옹호해 왔습니다.[224][225] 그는 1982년 12월 영국 의사협회 연설에서 처음으로 이 주제에 대한 관심을 공개적으로 표명했습니다.[226][227] 이 연설은 현대 의학의 "전투적"이고 "비판적"인 것으로 여겨졌고 일부 의료 전문가들에 의해 분노에 직면했습니다.[225] 마찬가지로, Prince's Foundation for Integrated Health (FIH)는 일반의들이 NHS 환자들에게 약초와 다른 대체 치료법을 제공하도록 장려하는 캠페인에 대해 과학 및 의료계의 반대를 받았습니다.[228][229]

2008년 4월, The Times는 Exeter 대학의 보완 의학 교수인 Edzard Ernst의 편지를 발행했고, 그 편지는 FIH에게 대체 의학을 홍보하는 두 명의 가이드를 소환할 것을 요청했습니다. 그 해 에른스트는 사이먼 싱과 함께 트릭 오어 트리트먼트(Trick or Treatment)라는 책을 출판했습니다. 재판 중인 대체 의학과 "웨일스 왕자 HRH"에 조롱적으로 바칩니다. 마지막 장은 찰스가 보완적이고 대체적인 치료법을 옹호하는 것에 대해 매우 비판적입니다.[230]

찰스 공국의 원본은 에른스트가 "경제적으로 취약한 사람들을 착취한다"고 비난한 "디톡스 팅크"와 "엄청난 돌팔이"를 포함한 다양한 보완 의약품을 생산했습니다.[231] 찰스는 그러한 약초 제품의 라벨링을 관리하는 규정을 완화하기 직전에 개인적으로 최소 7통의 편지를[232] 의약품 및 의료 제품 규제 기관에 썼습니다. 이 조치는 과학자들과 의료 기관들에 의해 광범위하게 비난을 받았습니다.[233] 2009년 10월, 찰스는 보건 장관인 앤디 버넘에게 NHS에서 대체 치료법을 더 많이 제공하는 것에 대해 로비를 벌였다고 보도되었습니다.[231]

회계부정에 따라 FIH는 2010년 4월에 폐쇄를 발표했습니다.[234][235] FIH는 2019년 찰스가 후원자가 된 의과대학으로 브랜드를 변경하고 올해 말에 다시 시작했습니다.[235][236][237]

스포츠

그의 젊은 시절부터 2005년까지, 찰스는 폴로 경기에 열성적인 선수였습니다.[238] 찰스는 또한 2005년에 이 스포츠가 영국에서 금지되기 전까지 여우 사냥에 자주 참여했습니다.[239] 1990년대 후반까지, 찰스의 참여가 그것에 반대하는 사람들에 의해 "정치적인 성명"으로 간주되었을 때, 그 활동에 대한 반대는 커지고 있었습니다.[240] 찰스는 1980년 왼쪽 뺨에 2인치 상처, 1990년 팔 골절, 1992년 왼쪽 무릎 연골 파열, 1998년 갈비뼈 골절, 2001년 어깨 골절 등 여러 해 동안 폴로와 사냥 관련 부상을 입었습니다.[102]

찰스는 어릴 때부터 연어 낚시에 열심이었고, 북대서양 연어를 보호하려는 오리 비그푸슨의 노력을 지지했습니다. 그는 스코틀랜드 애버딘셔의 디 강에서 자주 낚시를 하고, 그의 가장 특별한 낚시 기억이 아이슬란드의 Vopnafjör ð르에서 보낸 시간이라고 말합니다. 찰스는 번리 FC의 지지자입니다.[242]

사냥 외에도 찰스는 목표 소총 대회에도 참가하여 비지아나그램 경기(Lords vs. 커먼즈) 비즐리에서.[243] 그는 1977년 영국 전미 소총 협회의 회장이 되었습니다.[244]

시각예술, 공연예술, 문학예술

찰스는 어릴 때부터 공연에 참여했고, 케임브리지에서 공부하는 동안 스케치와 평론에 출연했습니다.[245]

찰스는 왕립 음악 대학, 왕립 오페라, 영국 실내 오케스트라, 필하모니아 오케스트라, 웨일스 국립 오페라, 왕립 셰익스피어 컴퍼니(Stratford-Upon-Avon의 공연 참석, 기금 모금 행사 지원)를 포함한 20개 이상의 공연 예술 단체의 회장 또는 후원자입니다. 그리고 회사의 연례 총회에 참석합니다),[246] 영국 영화 연구소,[247] 퍼셀 스쿨. 2000년, 그는 웨일스의 국가 악기를 연주하는 데 웨일스의 재능을 기르기 위해 공식 하프 연주자를 프린스 오브 웨일즈에 임명하는 전통을 되살렸습니다.[248]

찰스는 자선 모금을 위해 이 주제에 대한 책을 출간하고 여러 작품을 전시하고 판매하는 열정적인 수채화가입니다. 2016년에는 하이그로브 하우스의 한 상점에서 자신의 수채화 석판을 총 200만 파운드에 판매한 것으로 추정되었습니다. 그의 50번째 생일을 위해, 그의 수채화 50점이 햄튼 코트 궁전에 전시되었고, 그의 70번째 생일을 위해, 그의 작품들은 호주 국립 갤러리에 전시되었습니다.[249] 2001년 플로렌스 국제 현대 미술[250] 비엔날레에서 그의 시골 영지를 보여주는 수채화 20점의 석판화가 전시되었고, 2022년 런던에서 79점의 그의 그림이 전시되었습니다. 1994년 웨일스 공으로 그가 투자한 지 25주년을 기념하기 위해, 영국 왕실 우편은 그의 그림을 담은 우표를 발행했습니다.[249] 찰스는 왕립 예술 아카데미 개발 신탁의[251] 명예 회장이며 2015년, 2022년, 2023년에 각각 12명의 D-Day 참전 용사, 7명의 홀로코스트 생존자 및 10명의 윈드러시 세대 구성원의 그림을 의뢰했으며, 이 그림은 버킹엄 궁전의 퀸즈 갤러리에서 전시되었습니다.[252][253][254]

찰스는 여러 책의 저자이며 다른 사람들에 의해 수많은 책의 서문이나 서문을 기고했습니다. 그는 또한 다양한 다큐멘터리 영화에 출연했습니다.[255]

종교와 철학

즉위 직후 찰스는 자신을 "성공회의 헌신적인 기독교인"이라고 공개적으로 묘사했습니다.[256] 1965년 부활절 동안 16세의 나이에 윈저 성 세인트 조지 예배당에서 캔터베리 대주교 마이클 램지에 의해 성공회의 성찬례에 참석하는 것을 확인했습니다.[257] 왕은 잉글랜드[258] 교회의 최고 통치자이자 스코틀랜드 교회의 일원입니다. 그는 왕으로 선포된 직후에 그 교회를 지지하겠다고 맹세했습니다.[259] 그는 하이그로브와[260] 가까운 여러 성공회 교회에서 예배를 보고 발모랄 성에 머물 때 나머지 왕실 가족들과 함께 스코틀랜드 교회의 크레이티 커크에 참석합니다.

로렌스 반 데어 포스트는 1977년 찰스의 친구가 되었고, 그는 왕자의 "영적인 구루"로 불렸고 윌리엄 왕자의 대부였습니다.[261] 반 데어 포스트에서 찰스는 철학에 초점을 맞추고 다른 종교에 대한 관심을 발전시켰습니다.[262] 찰스는 노틸러스 도서상을 수상한 2010년 저서 "조화: 우리 세상을 바라보는 새로운 방법"[263]에서 자신의 철학적 견해를 밝혔습니다.[264] 그는 또한 아토스산,[265] 루마니아,[266] 세르비아에 있는 동방 정교회 수도원을 방문했으며,[267] 2020년 베들레헴에 있는 그리스도 성탄화 교회에서의 에큐메니컬 예배와 기독교 및 이슬람 고위 인사들과 함께 도시를 산책하는 것으로 절정에 달한 방문 기간 동안 예루살렘에서 동방 교회 지도자들을 만났습니다.[268] 찰스는 또한 영국 최초의 시리아 정교회 대성당인 액톤의 성 토마스 대성당의 축성식에 참석했습니다.[269] 찰스는 옥스퍼드 대학교의 옥스퍼드 이슬람 연구 센터의 후원자이며, 다문화적 맥락에서 이슬람 연구에 전념하는 마크필드 고등 교육 연구소의 출범식에 참석했습니다.[183][270]

1994년 딤블비와의 다큐멘터리에서 찰스는 왕이 될 때 영국 군주의 전통적인 "신앙의 수호자"라는 칭호가 아닌 "신앙의 수호자"로 보이고 싶다고 말했습니다. "모든 종교적 전통과 '내가 생각하는 신의 양식'을 수용하는 것을 선호합니다."[271] 이것은 그 당시 논란을 일으켰습니다. 즉위 선서가 바뀔 수도 있다는 추측과 함께 말입니다.[272] 그는 2015년에 "다른 사람들의 믿음도 실천될 수 있도록" 하면서 믿음의 수호자라는 직함을 유지할 것이라고 밝혔는데, 그는 이것을 영국 교회의 의무로 보고 있습니다.[273] 찰스는 즉위 직후 이 주제를 재확인하고 주권자로서의 의무에 "우리의 마음과 마음이 개인으로서 우리를 인도하는 종교, 문화, 전통 및 믿음을 통해 신앙 자체와 실천을 위한 공간을 보호하는 것을 포함하여 우리나라의 다양성을 보호할 의무"가 포함된다고 선언했습니다.[256] 그의 포용적이고 다신앙적인 접근법과 그 자신의 기독교 신앙은 왕으로서의 첫 번째 크리스마스 메시지에서 표현되었습니다.[274]

미디어 이미지 및 여론

찰스는 태어났을 때부터 언론의 주목을 받았고, 그가 성숙해지면서 더 커졌습니다. 그것은 그의 다이애나와 카밀라와의 결혼과 그들의 여파에 크게 영향을 받은 양면적인 관계였지만, 또한 그의 향후 왕으로서의 행동에 중점을 두었습니다.[275]

1970년대 후반에 "세계에서 가장 자격 있는 총각"으로 묘사된 [276]찰스는 그 후 다이애나에 의해 가려졌습니다.[277] 그녀가 죽은 후, 언론은 정기적으로 찰스의 사생활을 침해하고 노출물을 인쇄했습니다. 자신의 의견을 표현하는 것으로 유명한 그는 70세 생일을 맞아 인터뷰를 하던 중 왕이 되면 같은 방식으로 이런 일이 계속될 것이냐는 질문에 "아니오"라고 답했습니다. 안될 거에요. 내가 그렇게 멍청하진 않아. 나는 주권을 갖는 것이 별개의 행사라는 것을 알고 있습니다. 물론, 저는 그것이 어떻게 작동해야 하는지 완전히 이해합니다."[278] 2023년, 뉴 스테이츠맨은 찰스를 올해의 네 번째 가장 강력한 우파 인물로 선정하면서, 그를 다양한 전통주의 싱크탱크와 이전 글을 지지한 것에 대해 "낭만적인 전통주의자"이자 "공직 생활의 마지막 반동주의자"로 묘사했습니다.[279]

2018년 BMG Research 여론조사에 따르면 영국인의 46%는 찰스가 어머니의 죽음에 즉시 퇴위하여 윌리엄을 지지하기를 원했습니다.[280] 그러나 2021년 여론조사에 따르면 영국 국민의 60%가 그에 대해 호의적인 의견을 가지고 있다고 합니다.[281] 그가 왕위에 오르자 스테이츠맨은 영국 국민들에게 찰스의 인기를 42퍼센트로 올린 여론조사를 보고했습니다.[282] 보다 최근의 여론조사는 그가 왕이 된 후에 그의 인기가 급격히 증가했다는 것을 시사했습니다.[283] YouGov에 따르면 2023년 4월 현재 Charles의 지지율은 55%입니다.[284]

프레스 처리에 대한 반응

1994년 독일의 타블로이드판 신문 빌트는 샤를이 르 바루에서 휴가를 보내는 동안 찍은 나체 사진을 발행했는데, 보도에 따르면 이 사진들은 3만 파운드에 팔렸다고 합니다.[285] 버킹엄 궁은 "누구나 이런 종류의 침입을 당하는 것은 정당하지 않다"고 말했습니다.[286]

"종종 언론의 표적이었던 찰스는 2002년에 언론 300주년을 기념하기 위해 세인트 브라이드 플리트 스트리트에 모인 "수많은 편집자, 출판인 및 기타 미디어 경영진"에게 연설할 때 해고될 기회를 얻었습니다.[note 7][287] 공무원들을 "끊임없는 비판의 부식성 물방울"로부터 보호하면서, 그는 언론이 "어색하고, 짜증나고, 냉소적이고, 피비린내 나며, 때로는 거슬리고, 때로는 부정확하고, 때로는 개인과 기관에 매우 불공정하고 해롭다"고 언급했습니다.[287] 그러나 그는 자신과 언론과의 관계에 대해 "아마도 우리 둘 다 때때로 서로에게 약간 강경하고, 단점을 과장하고, 각각의 좋은 점을 무시한다"고 결론지었습니다.[287]

찰스는 1997년 홍콩의 주권을 중국에 양도하는 것과 같은 문제에 대한 자신의 의견을 밝히며 자신의 개인적인 저널의 발췌문이 출판된 후 일요일 더 메일을 상대로 법원 소송을 제기했습니다. 이에 찰스는 중국 정부 관리들이 "오래된 밀랍인형"이라고 묘사했습니다.[288][87] 찰스와 카밀라는 2011년 뉴스 미디어 전화 해킹 사건과 관련하여 기밀 정보가 표적이 되거나 실제로 획득된 것으로 알려진 개인으로 명명되었습니다.[289]

인디펜던트는 2015년 찰스가 "15페이지 계약을 체결한 조건으로 방송사들과만 통화할 것"이라고 언급하며 클래런스 하우스가 영화의 '대략적인 컷'과 '미세 컷' 편집에 모두 참석하고 최종 제품에 불만이 있다면 '프로그램에서 전체 기여를 제거할 수 있다'[290]고 요구했습니다. 이 계약은 찰스를 향한 모든 질문에 대해 그의 대리인이 사전 승인하고 조사해야 한다고 규정했습니다.[290]

주거 및 금융

2023년 가디언지는 찰스의 개인 재산을 18억 파운드로 추정했습니다.[291] 이 추정치에는 랭커스터 공국의 자산 6억5천300만 파운드(연소득 2천만 파운드), 보석 5억3천300만 파운드, 부동산 3억3천만 파운드, 주식 및 투자 1억4천200만 파운드, 최소 1억 파운드 상당의 우표 수집, 2천700만 파운드 상당의 경주마, 2천400만 파운드 상당의 예술품, 그리고 630만 파운드 상당의 자동차.[291] 그가 어머니로부터 물려받은 이 재산의 대부분은 상속세가 면제됩니다.[291][292]

이전에 퀸 마더의 거주지였던 클래런스 하우스는 450만 파운드를 들여 개조한 후 2003년부터 찰스의 런던 공식 거주지였습니다.[293][294] 그는 2003년까지 그의 주요 거주지로 남아있던 세인트 제임스 궁의 요크 하우스로 이사하기 전에 켄싱턴 궁의 8호와 9호 아파트를 다이애나와 공유했습니다.[294] 글로스터셔의 하이그로브 하우스는 콘월 공국이 소유하고 있으며, 1980년 찰스가 사용하기 위해 구입했으며, 그는 연간 336,000파운드에 임대했습니다.[295][296] 윌리엄이 콘월 공작이 된 이후, 찰스는 재산 사용을 위해 연간 70만 파운드를 지불할 것으로 예상됩니다.[297] 찰스는 또한 루마니아의 비스크리 마을 근처에 부동산을 소유하고 있습니다.[298][299]

찰스의 주요 수입원은 웨일즈 왕자로서 농업, 주거 및 상업 부동산을 포함한 133,658 에이커(약 54,090 헥타르)의 토지와 투자 포트폴리오를 소유한 콘월 공국에서 발생했습니다. 찰스는 1993년부터 2013년에 업데이트된 왕실 과세에 관한 양해각서에 따라 자발적으로 세금을 납부해 왔습니다.[300] 여왕 폐하의 세입세관은 2012년 12월 콘월 공국의 조세 회피 혐의에 대한 조사를 요청받았습니다.[301] 공국은 파라다이스 페이퍼(Paradise Papers)에 이름을 올렸는데, 이 문서는 독일 신문 Süddeutsche Zeitung에 유출된 해외 투자와 관련된 기밀 전자 문서입니다.[302][303]

직함, 스타일, 명예, 무기

제목 및 스타일

찰스는 영연방 전역에서 많은 칭호와 명예 군대 직책을 맡았고, 그의 나라에서 많은 명령을 받은 주권자이며, 전 세계로부터 명예와 상을 받았습니다.[305][306][307][308][309] 그의 각 영역에서 그는 비슷한 공식을 따르는 뚜렷한 제목을 가지고 있습니다: 성 루시아의 왕과 성 루시아의 다른 영역과 영토, 호주의 왕과 호주의 다른 영역과 영토 등. 별도의 영역이 아닌 왕권 의존 관계인 맨섬에서 그는 맨의 군주로 알려져 있습니다. 찰스는 또한 '신앙의 수호자'로 불립니다.

엘리자베스 2세의 통치 기간 동안 찰스가 즉위할 때 어떤 섭정적 이름을 선택할지에 대한 추측이 있었습니다. 찰스 3세 대신 그는 조지 7세로 통치하기로 선택하거나 그의 다른 주어진 이름 중 하나를 사용할 수 있었습니다.[310] 그는 할아버지 조지 6세를 기리고 이전에 논란이 많았던 찰스 왕들과의 연관성을 피하기 위해 조지를 사용할지도 모른다고 보도되었습니다.[note 8][311][312] 찰스의 사무실은 2005년에 아직 결정된 것이 없다고 주장했습니다.[313] 리즈 트러스(Liz Truss)가 발표하고 클래런스 하우스(Clarence House)가 찰스가 종교적 이름인 찰스 3세(Charles III)를 선택했다고 확인할 [314]때까지 추측은 그의 어머니가 사망한 후 몇 시간 동안 계속되었습니다.[315][316]

1976년에 현역으로 군 복무를 떠난 찰스는 2012년 엘리자베스 2세 여왕에 의해 함대 사령관, 야전 원수, 영국 공군 원수 등 세 가지 군 복무에서 모두 가장 높은 계급을 받았습니다.[317]

팔

웨일스 공국의 문장은 영국의 문장에 바탕을 두었고, 백인의 라벨과 웨일스 공국의 인스커천으로 구별되었으며, 상속인의 왕관과 이흐디엔(Ichdien)이라는 모토가 있었습니다. 독일어:[ɪ ˈ 디 ː], "나는 봉사한다") 대신 Dieu et mondroit.

찰스가 왕이 되었을 때, 그는 영국과 캐나다의 왕실 문장을 물려 받았습니다.[318] 2022년 9월 27일 세인트 에드워드 왕관 대신 튜더 왕관을 묘사한 그의 왕실 사이퍼의 디자인이 공개되었습니다. 무기 대학에 따르면, 튜더 왕관은 이제 영국의 왕실 군대를 상징하고 제복과 왕관 배지에 사용될 것입니다.[319]

배너, 플래그 및 표준

상속인으로서

찰스가 웨일즈의 왕자로 사용한 현수막은 지역에 따라 다양했습니다. 영국에 대한 그의 개인적인 기준은 그의 팔에서와 다른 영국 왕실 표준이었고, 3점 아르젠트라는 라벨과 웨일즈 공국의 팔의 에스카천이 중앙에 있었습니다. 찰스가 영국군과 관련된 공식적인 자격으로 활동할 때 웨일즈, 스코틀랜드, 콘월, 캐나다 이외의 지역과 영국 전역에서 사용되었습니다.[320]

웨일즈에서 사용하기 위한 개인 깃발은 웨일즈의 왕실 배지에 기반을 두었습니다.[320] 스코틀랜드에서 1974년에서 2022년 사이에 사용된 개인 현수막은 세 개의 고대 스코틀랜드 타이틀에 기반을 두고 있습니다. 로테세이 공작(스코틀랜드의 왕으로 보인다), 스코틀랜드의 고위 스튜어드, 섬의 영주. 콘월에서, 그 현수막은 콘월 공작의 무기였습니다.[320]

2011년, 캐나다 헤럴드 협회는 프린스 오브 웨일즈를 위한 개인적인 경고 현수막을 선보였는데, 이 현수막은 금색 단풍잎 화환으로 둘러싸인 프린스 오브 웨일즈의 깃털의 파란색 둥근 타원형과 3개의 포인트로 이루어진 흰색 라벨로 장식되어 있습니다.[321]

주권자로서

영국의 왕실 표준은 영국에서 왕을 대표하고 캐나다를 제외한 해외 공식 방문에서 사용됩니다. 그것은 1702년부터 연속적인 영국 군주들에 의해 사용되어 온, 차별화되지 않은 배너 형태의 왕실의 무기입니다. 캐나다의 왕실 표준은 캐나다에서 국왕이 사용하고 해외에서 캐나다를 대표하여 사용합니다. 차별화되지 않은 배너 형태의 캐나다 왕립 문장 에스카천입니다.

쟁점.

| 이름. | 출생. | 결혼. | 아이들. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 날짜. | 배우자. | |||

| 윌리엄 왕세손 | 1982년 6월 21일 | 2011년 4월 29일 | 캐서린 미들턴 | 웨일스 공 조지 웨일스 공녀 샬롯 프린스루이 |

| 서섹스 공작 해리 왕자 | 1984년 9월 15일 | 2018년 5월 19일 | 메건 마클 | |

조상

| 찰스 3세의[322] 조상 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

참고 항목

메모들

- ^ a b 영국 외에도, 14개의 다른 왕국들은 앤티가와 바부다, 호주, 바하마, 벨리즈, 캐나다, 그레나다, 자메이카, 뉴질랜드, 파푸아 뉴기니, 세인트 키츠 앤 네비스, 세인트 루시아, 세인트 빈센트 앤 그레나딘, 솔로몬 제도, 투발루입니다.

- ^ 군림하는 군주로서 찰스는 보통 성을 사용하지 않지만 성이 필요할 때는 마운트배튼윈저입니다.[1]

- ^ 군주로서 찰스는 영국 교회의 최고 통치자입니다. 그는 또한 스코틀랜드 교회의 회원입니다.

- ^ 전하는 바에 따르면 그는 엘리자베스 2세에 의해 "찰스 삼촌"이라고 불렸던 노르웨이의 대부 하콘 7세의 이름을 따서 "찰스"라고 이름 지어졌다고 합니다.[5][6]

- ^ 찰스 왕세자의 대부모는 다음과 같습니다: 영국의 왕(그의 외할아버지); 노르웨이의 왕(그의 친사촌은 두 번 제거되었고, 외증조부는 결혼하여 찰스의 증조부인 애슬론 백작이 대리를 맡았습니다.); 메리 여왕(그의 외증조모), 마가렛 공주(그의 외숙모), 그리스와 덴마크의 조지 왕자(그의 친증조모), 에든버러 공작이 대리인을 맡았고, 밀포드 헤이븐의 공작 부인(친척 증조모), 브라보른 부인(친척), 그리고 혼 데이비드 보우스-라이온 부인(외척)이 대리인을 맡았습니다.[7]

- ^ 마운트배튼은 마지막 영국 총독이자 인도의 첫 총독을 역임했습니다.

- ^ 런던의 첫 일간지인 데일리 쿠랑은 1702년에 발행되었습니다.

- ^ 즉, 스튜어트 왕 찰스 1세는 참수되었고, 찰스 2세는 문란한 생활방식으로 알려져 있습니다. 한때 스튜어트가 영국과 스코틀랜드 왕좌의 가장이었던 찰스 에드워드 스튜어트는 그의 지지자들에 의해 찰스 3세라고 불렸습니다.[311]

참고문헌

인용문

- ^ "The Royal Family name". Official website of the British monarchy. Archived from the original on 15 February 2009. Retrieved 3 February 2009.

- ^ "No. 38455". The London Gazette. 15 November 1948. p. 1.

- ^ Brandreth 2007, p. 120.

- ^ Bland, Archie (1 May 2023). "King Charles: 71 facts about his long road to the throne". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 27 February 2024. Retrieved 5 March 2024.

- ^ Holden, Anthony (1980). Charles, Prince of Wales. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-330-26167-8.

- ^ "Close ties through the generations". The Royal House of Norway. 8 September 2022. Archived from the original on 23 September 2023. Retrieved 23 September 2023.

- ^ "The Christening of Prince Charles". Royal Collection Trust. Archived from the original on 17 December 2021. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ^ a b c "HRH The Prince of Wales Prince of Wales". Clarence House. Archived from the original on 9 April 2023. Retrieved 13 September 2022.

- ^ "The Book of the Baptism Service of Prince Charles". Royal Collection Trust. Archived from the original on 20 April 2023. Retrieved 25 April 2023.

- ^ Brandreth 2007, p. 127.

- ^ "50 facts about the Queen's Coronation". The Royal Family. Archived from the original on 7 February 2021. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- ^ Gordon, Peter; Lawton, Denis (2003). Royal Education: Past, Present, and Future. F. Cass. p. 215. ISBN 978-0-7146-8386-7. Retrieved 18 September 2022.

- ^ a b c "About the Prince of Wales". Royal Household. 26 December 2018. Archived from the original on 9 May 2016.

- ^ a b Johnson, Bonnie; Healy, Laura Sanderson; Thorpe-Tracey, Rosemary; Nolan, Cathy (25 April 1988). "Growing Up Royal". Time. Archived from the original on 31 March 2005. Retrieved 4 June 2009.

- ^ "Lieutenant Colonel H. Stuart Townend". The Times. 30 October 2002. ISSN 0140-0460. Archived from the original on 22 June 2018. Retrieved 29 May 2009.

- ^ a b c "HRH The Prince of Wales". Debrett's. Archived from the original on 4 July 2012. Retrieved 27 August 2012.

- ^ Brandreth 2007, 페이지 139.

- ^ Rocco, Fiammetta (18 October 1994). "Flawed Family: This week the Prince of Wales disclosed still powerful resentments against his mother and father". The Independent (UK). Independent Digital News & Media Ltd. ISSN 1741-9743. OCLC 185201487. Archived from the original on 16 February 2022. Retrieved 15 February 2022.

- ^ a b Rudgard, Olivia (10 December 2017). "Colditz in kilts? Charles loved it, says old school as Gordonstoun hits back at The Crown". The Daily Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. OCLC 49632006. Archived from the original on 20 June 2018. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f "The Prince of Wales – Education". Clarence House. Archived from the original on 13 November 2012. Retrieved 8 December 2012.

- ^ "The New Boy at Timbertop". The Australian Women's Weekly. Vol. 33, no. 37. 9 February 1966. p. 7. Archived from the original on 1 April 2021. Retrieved 13 January 2018 – via National Library of Australia.; "Timbertop – Prince Charles Australia" (Video with audio, 1 min 28 secs). British Pathé. 1966. Archived from the original on 11 March 2021. Retrieved 12 January 2018 – via YouTube.

- ^ "Prince had happy time at Timbertop". Australian Associated Press. Vol. 47, no. 13, 346. The Canberra Times. 31 January 1973. p. 11. Archived from the original on 1 April 2021. Retrieved 13 January 2018 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Brandreth 2007, p. 145.

- ^ Brandreth 2007, p. 151

- ^ Holland, Fiona (10 September 2022). "God Save The King!". Trinity College Cambridge. Archived from the original on 14 September 2022. Retrieved 14 September 2022.

- ^ "No. 41460". The London Gazette. 29 July 1958. p. 4733.; "The Prince of Wales – Previous Princes of Wales". Prince of Wales. Archived from the original on 11 October 2008. Retrieved 12 October 2008.

- ^ "The Prince of Wales – Investiture". Clarence House. Archived from the original on 20 October 2008. Retrieved 12 October 2008.

- ^ Jones, Craig Owen (2013). "Songs of Malice and Spite"?: Wales, Prince Charles, and an Anti-Investiture Ballad of Dafydd Iwan (PDF) (7th ed.). Michigan Publishing. p. 1. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 December 2022. Retrieved 8 May 2023.

- ^ "H.R.H. The Prince of Wales Introduced". Hansard. 11 February 1970. HL Deb vol 307 c871. Archived from the original on 19 October 2020. Retrieved 16 October 2019.; "The Prince of Wales – Biography". Prince of Wales. Archived from the original on 9 November 2012. Retrieved 12 October 2008.

- ^ "Sport and Leisure". Hansard. 13 June 1974. HL Deb vol 352 cc624–630. Archived from the original on 18 October 2020. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- ^ Shuster, Alvin (14 June 1974). "Prince Charles Speaks in Lords". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. OCLC 1645522. Archived from the original on 29 April 2020. Retrieved 12 June 2018.

- ^ "Voluntary Service in the Community". Hansard. 25 June 1975. HL Deb vol 361 cc1418–1423. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- ^ "The Prince's Trust". The Prince's Charities. Archived from the original on 21 September 2008. Retrieved 12 October 2008.

- ^ Ferretti, Fred (18 June 1981). "Prince Charles pays a quick visit to city". The New York Times. OCLC 1645522. Archived from the original on 29 April 2020. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- ^ Daley, Paul (9 November 2015). "Long to reign over Aus? Prince Charles and Australia go way back". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 13 June 2018. Retrieved 13 June 2018.

- ^ David Murray (24 November 2009). "Next governor-general could be Prince Harry, William". The Australian. Archived from the original on 29 April 2020. Retrieved 12 June 2018.

- ^ Brandreth 2007, 페이지 169-170

- ^ "Military Career of the Prince of Wales". Prince of Wales. Archived from the original on 14 May 2013. Retrieved 19 April 2013.

- ^ "Prince Charles after receiving his wings 20 August 1971". Royal Collection Trust. Archived from the original on 5 October 2022. Retrieved 5 October 2022.; "Prince Charles attends RAF Cranwell ceremony". BBC News. 16 July 2020. Archived from the original on 5 October 2022. Retrieved 5 October 2022.

- ^ a b Brandreth 2007, p. 170.

- ^ "Prince Charles: Video shows 'upside down' parachute jump". BBC News. 15 July 2021. Archived from the original on 8 October 2022. Retrieved 5 October 2022.

- ^ "Occurrence # 187927". Flight Safety Foundation. Archived from the original on 27 October 2017. Retrieved 3 May 2023.; Boggan, Steve (20 July 1995). "Prince gives up flying royal aircraft after Hebrides crash". The Independent (UK). Archived from the original on 24 March 2017.

- ^ Brandreth 2007, p. 192.

- ^ Brandreth 2007, 페이지 193.

- ^ Brandreth 2007, p. 194.

- ^ Brandreth 2007, p. 195.

- ^ Brandreth 2007, pp. 15-17, 178.

- ^ 2005년 6월 72페이지

- ^ Dimble by 1994, pp. 204–206; Brandreth 2007, p. 200

- ^ 딤블 by 1994, 페이지 263.

- ^ a b Dimble by 1994, 페이지 263-265.

- ^ 딤블 by 1994, p. 279.

- ^ Dimble by 1994, 페이지 280-282.

- ^ Dimble by 1994, pp. 281–283.

- ^ "Royally Minted: What we give them and how they spend it". New Statesman. Vol. 138, no. 4956–4968. London. 13 July 2009. Retrieved 7 May 2023.

- ^ 브라운 2007, 720쪽.

- ^ 스미스 2000, 페이지 561.

- ^ Griffiths, Eleanor Bley (1 January 2020). "The truth behind Charles and Camilla's affair storyline in The Crown". Radio Times. Archived from the original on 8 September 2022. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

- ^ "Diana 'wanted to live with guard'". BBC News. 7 December 2004. Archived from the original on 31 July 2017. Retrieved 31 July 2017.

- ^ a b Langley, William (12 December 2004). "The Mannakee file". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 31 July 2017. Retrieved 31 July 2017.

- ^ Lawson, Mark (7 August 2017). "Diana: In Her Own Words – admirers have nothing to fear from the Channel 4 tapes". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 20 September 2017. Retrieved 22 October 2017.

- ^ Milmo, Cahal (8 December 2004). "Conspiracy theorists feast on inquiry into death of Diana's minder". The Independent (UK). Independent Digital News & Media Ltd. ISSN 1741-9743. OCLC 185201487. Archived from the original on 1 August 2017. Retrieved 31 July 2017.

- ^ Duboff, Josh (13 March 2017). "Princess Diana's Former Lover Maintains He Is Not Prince Harry's Father". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on 26 June 2019. Retrieved 25 November 2018.

- ^ a b Quest, Richard (3 June 2002). "Royals, Part 3: Troubled times". CNN. Archived from the original on 15 July 2016. Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- ^ "Hewitt denies Prince Harry link". BBC News. 21 September 2002. Archived from the original on 15 February 2009. Retrieved 24 April 2011.

- ^ "The Camillagate Tapes". Textfiles.com (phone transcript). Phone Phreaking. 18 December 1989. Archived from the original on 1 July 2010.; "Royals caught out by interceptions". BBC News. 29 November 2006. Archived from the original on 28 August 2017. Retrieved 27 April 2012.; Dockterman, Eliana (9 November 2022). "The True Story Behind Charles and Camilla's Phone Sex Leak on The Crown". Time. Archived from the original on 16 November 2022. Retrieved 17 November 2022.

- ^ "The Princess and the Press". PBS. Archived from the original on 10 March 2017. Retrieved 7 January 2017.; "Timeline: Charles and Camilla's romance". BBC. 6 April 2005. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 7 January 2017.

- ^ 딤블 by 1994, 페이지 395.

- ^ "1995: Diana admits adultery in TV interview". BBC News. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 1 August 2018.

- ^ "The Panorama Interview with the Princess of Wales". BBC News. 20 November 1995. Archived from the original on 4 March 2011. Retrieved 8 January 2010.

- ^ "'Divorce': Queen to Charles and Diana". BBC News. 20 December 1995. Archived from the original on 23 December 2010. Retrieved 12 October 2008.

- ^ "Charles and Diana to divorce". Associated Press. 21 December 1995. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- ^ Neville, Sarah (13 July 1996). "Charles and Diana Agree to Terms of Divorce". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- ^ Whitney, Craig R. (31 August 1997). "Prince Charles Arrives in Paris to Take Diana's Body Home". The New York Times. OCLC 1645522. Archived from the original on 6 December 2013. Retrieved 5 May 2014.

- ^ "Diana letter 'warned of car plot'". CNN. 20 October 2003. Archived from the original on 12 December 2003. Retrieved 14 April 2019.; Eleftheriou-Smith, Loulla-Mae (30 August 2017). "Princess Diana letter claims Prince Charles was 'planning an accident' in her car just 10 months before fatal crash". The Independent (UK). Archived from the original on 12 October 2019. Retrieved 14 April 2019.; Rayner, Gordon (20 December 2007). "Princess Diana letter: 'Charles plans to kill me'". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ^ Badshah, Nadeem (19 June 2021). "Police interviewed Prince Charles over 'plot to kill Diana'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 19 June 2021. Retrieved 8 September 2021.

- ^ "Profile: Duchess of Cornwall". BBC News. 9 April 2012. Archived from the original on 3 May 2023. Retrieved 3 May 2023.

- ^ "Order in Council". The National Archives. 2 March 2005. Archived from the original on 3 November 2010. Retrieved 20 February 2012.

- ^ Valpy, Michael (2 November 2005). "Scholars scurry to find implications of royal wedding". The Globe and Mail. Toronto. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 4 March 2009.

- ^ "Panorama Lawful impediment?". BBC News. 14 February 2005. Archived from the original on 29 September 2009. Retrieved 25 February 2009.

- ^ The Secretary of State for Constitutional Affairs and Lord Chancellor (Lord Falconer of Thoroton) (24 February 2005). "Royal Marriage; Lords Hansard Written Statements 24 Feb 2005 : Column WS87 (50224-51)". Publications.parliament.uk. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 12 October 2008.

- ^ "Pope funeral delays royal wedding". BBC News. 4 April 2005. Archived from the original on 20 October 2013. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- ^ "Q&A: Queen's wedding decision". BBC News. 23 February 2005. Archived from the original on 11 January 2009. Retrieved 17 September 2012.

- ^ "Charles And Camilla Finally Wed, After 30 Years Of Waiting, Prince Charles Weds His True Love". CBS News. 9 April 2005. Archived from the original on 12 November 2010. Retrieved 12 October 2008.

- ^ Oliver, Mark (9 April 2005). "Charles and Camilla wed". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 22 August 2013. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- ^ a b "100 Coronation Facts". Royal Household. Archived from the original on 1 May 2023. Retrieved 1 May 2023.

- ^ a b c Landler, Mark (8 September 2022). "Long an Uneasy Prince, King Charles III Takes On a Role He Was Born To". The New York Times. OCLC 1645522. Archived from the original on 20 September 2022. Retrieved 19 September 2022.

- ^ "The royal clan: who's who, what do they do and how much money do they get?". The Guardian. 7 April 2023. Archived from the original on 7 April 2023. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- ^ Brandreth 2007, p. 325.

- ^ "Opening of the Senedd". National Assembly for Wales. Archived from the original on 10 August 2014. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- ^ "Administration". The Royal Collection Trust. Archived from the original on 6 October 2012. Retrieved 19 April 2013.

- ^ Trumbull, Robert (10 October 1970). "Fiji Raises the Flag of Independence After 96 Years of Rule by British". The New York Times. OCLC 1645522. Archived from the original on 10 September 2022. Retrieved 3 May 2023.

- ^ "1973: Bahamas' sun sets on British Empire". BBC News. 9 July 1973. Archived from the original on 1 February 2008. Retrieved 3 May 2023.

- ^ "Papua New Guinea Celebrates Independence". The New York Times. 16 September 1975. OCLC 1645522. Archived from the original on 10 September 2022. Retrieved 3 May 2023.

- ^ Ross, Jay (18 April 1980). "Zimbabwe Gains Independence". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 4 February 2021. Retrieved 3 May 2023.

- ^ Wedel, Paul (22 February 1984). "Brunei celebrated its independence from Britain Thursday with traditional..." UPI. Archived from the original on 19 February 2022. Retrieved 3 May 2023.

- ^ Ainge Roy, Eleanor (13 January 2018). "'Damn ... I missed': the incredible story of the day the Queen was nearly shot". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 1 March 2018. Retrieved 1 March 2018.

- ^ Newman, John (12 May 1994). "Cambodian Refugees". New South Wales Legislative Assembly Hansard. Parliament of New South Wales. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007.; "Student fires 2 blanks at Prince Charles". Los Angeles Times. 27 January 1994. Archived from the original on 12 August 2014. Retrieved 13 April 2018.

- ^ "Archive: Prince Charles visits Ireland in 1995". BBC News. 21 April 2015. Archived from the original on 11 May 2018. Retrieved 14 April 2018.; McCullagh, David; Milner, Cathy. "Prince Charles Makes First Royal Visit to Ireland 1995". Raidió Teilifís Éireann. Archived from the original on 15 April 2018. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- ^ 브렌던 2007, 페이지 660.

- ^ 브라운 1998, 페이지 594.

- ^ a b c "King Charles cancer diagnosis: Health issues monarch has faced over the years". Sky News. 5 February 2024. Archived from the original on 5 February 2024. Retrieved 5 February 2024.

- ^ "Charles has hernia operation". BBC News. 29 March 2003. Archived from the original on 21 January 2024. Retrieved 22 January 2024.

- ^ "Charles shakes hands with Mugabe at Pope's funeral". The Times. 8 April 2005. Archived from the original on 22 June 2018. Retrieved 8 July 2007. (가입 필요)

- ^ "The Prince of Wales opens the Commonwealth Games". Clarence House. 3 October 2010. Archived from the original on 21 May 2015. Retrieved 28 August 2013.

- ^ "Prince Charles, Camilla's Car Attacked By Student Protesters in London". huffingtonpost. 9 December 2010. Archived from the original on 23 March 2013. Retrieved 8 October 2012.; "Royal car attacked in protest after MPs' fee vote". BBC News. Archived from the original on 10 December 2010. Retrieved 10 December 2010.; "Prince Charles and Duchess of Cornwall unhurt in attack". BBC News. 9 December 2010. Archived from the original on 23 February 2012. Retrieved 16 September 2012.

- ^ Suroor, Hasan (8 May 2013). "Queen to miss Colombo CHOGM". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 9 August 2013. Retrieved 7 August 2013.; "Queen to miss Commonwealth meeting for first time since 1973". The Guardian. 7 May 2013. Archived from the original on 21 October 2013. Retrieved 7 August 2013.

- ^ Urquart, Conal (13 May 2015). "Prince Charles Shakes the Hand of Irish Republican Leader Gerry Adams". Time. Archived from the original on 21 May 2015. Retrieved 21 May 2015.

- ^ McDonald, Henry (19 May 2015). "Prince Charles and Gerry Adams share historic handshake". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 21 May 2015. Retrieved 20 May 2015.; "Historic handshake between Prince Charles and Gerry Adams". The Independent (UK). Archived from the original on 19 May 2015. Retrieved 21 May 2015.; Adam, Karla (19 May 2015). "Prince Charles, in Ireland, meets with Sinn Fein party leader Gerry Adams". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 22 May 2015. Retrieved 21 May 2015.

- ^ a b "Queen's Funeral Set for Sept. 19 at Westminster Abbey". The New York Times. 10 September 2022. OCLC 1645522. Archived from the original on 20 September 2022. Retrieved 20 September 2022.

The state funeral for Queen Elizabeth II will be held at 11 a.m. Monday, Sept. 19, at Westminster Abbey, Buckingham Palace announced on Saturday.

- ^ Adam, Karla (20 April 2018). "Commonwealth backs Prince Charles as its next leader". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 6 August 2018. Retrieved 5 July 2018.

- ^ "Prince Charles and Camilla make history in Cuba". BBC News. 25 March 2019. Archived from the original on 2 April 2019. Retrieved 10 May 2019.

- ^ Reynolds, Emma; Foster, Max; Wilkinson, David (25 March 2020). "Prince Charles tests positive for novel coronavirus". CNN. Archived from the original on 25 March 2020. Retrieved 25 March 2020.; Furness, Hannah; Johnson, Simon (25 March 2020). "Prince Charles tests positive for coronavirus: These are his most recent engagements". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 25 March 2020. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- ^ "Coronavirus: Prince Charles tests positive but 'remains in good health'". BBC News. 25 March 2020. Archived from the original on 25 March 2020. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- ^ "Warning to all as Prince Charles catches coronavirus amid 'queue jump' claims – The Yorkshire Post says". The Yorkshire Post. 15 March 2020. Archived from the original on 26 March 2020. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- ^ Ott, Haley (10 February 2022). "Britain's Prince Charles tests positive for COVID-19 for the 2nd time". CBS News. Archived from the original on 6 June 2022. Retrieved 10 February 2022.

- ^ "Covid: Prince Charles and Camilla get first vaccine". BBC News. 10 February 2021. Archived from the original on 21 April 2022. Retrieved 29 May 2021.

- ^ Mills, Rhiannon (30 November 2021). "Barbados: Prince Charles acknowledges 'appalling' history of slavery as island becomes a republic". Sky News. Archived from the original on 30 November 2021. Retrieved 30 November 2021.

- ^ Murphy, Victoria (28 November 2021). "All About Prince Charles's Visit to Barbados as the Country Cuts Ties with the Monarchy". Town & Country. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 3 May 2023.

- ^ Nikkhah, Roya (28 November 2021). "Regretful Prince Charles flies to Barbados to watch his realm become a republic". Sunday Times. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 3 May 2023.

- ^ Davies, Caroline (10 May 2022). "Queen remains 'very much in charge' even as Charles makes speech". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 10 May 2022. Retrieved 10 May 2022.

- ^ "Prince Charles becomes longest-serving heir apparent". BBC News. 20 April 2011. Archived from the original on 18 July 2015. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- ^ Rayner, Gordon (19 September 2013). "Prince of Wales will be oldest monarch crowned". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 20 September 2013. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- ^ "King Charles III pays tribute to his 'darling mama' in first address". BBC News. 9 September 2022. Archived from the original on 10 September 2022. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

- ^ "Charles formally confirmed as king in ceremony televised for first time". BBC News. 10 September 2022. Archived from the original on 10 September 2022. Retrieved 10 September 2022.

- ^ Ratcliffe, Rebecca (10 September 2022). "Charles III is proclaimed King". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 10 September 2022. Retrieved 10 September 2022.

- ^ Torrance, David (29 September 2022). The Accession of King Charles III (PDF). House of Commons Library. p. 21. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 April 2023. Retrieved 25 April 2023.

- ^ "Coronation on 6 May for King Charles and Camilla, Queen Consort". BBC News. 11 October 2022. Archived from the original on 11 October 2022. Retrieved 11 October 2022.

- ^ Mahler, Kevin (14 February 2022). "Ghosts? Here's the true tale of things that go bump in the night". The Times. Archived from the original on 28 October 2022. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

- ^ 피핀스터 2022.

- ^ Hyde, Nathan; Field, Becca (17 February 2022). "Prince of Wales plans for a 'scaled back' coronation ceremony with Camilla". CambridgeshireLive. Archived from the original on 8 March 2022. Retrieved 8 March 2022.

- ^ Arasteh, Amira (23 September 2022). "King Charles III coronation: When is he officially crowned and what happens next?". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 23 September 2022. Retrieved 23 September 2022.; Dixon, Hayley; Gurpreet, Narwan (13 September 2022). "Coronation for the cost of living crisis as King expresses wish for 'good value'". The Times. Archived from the original on 25 September 2022. Retrieved 14 September 2022.

- ^ "King Charles III, the new monarch". BBC News. 18 September 2022. Archived from the original on 20 September 2022. Retrieved 13 October 2022.

- ^ "King Charles III: Special Edinburgh day ends with gun salute and flypast". BBC News. 5 July 2023. Archived from the original on 1 August 2023. Retrieved 5 July 2023.

- ^ Kirka, Danica (22 November 2022). "King Charles III welcomes S. African leader for state visit". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 25 March 2023. Retrieved 21 September 2023.

- ^ Said-Moorhouse, Lauren; Foster, Max (30 March 2023). "King Charles becomes first British monarch to address German parliament". CNN. Archived from the original on 27 September 2023. Retrieved 21 September 2023.

- ^ Said-Moorhouse, Lauren (1 September 2023). "King Charles makes historic speech at French senate as he hails 'indispensable' UK-France relationship". CNN. Archived from the original on 21 September 2023. Retrieved 21 September 2023.

- ^ Foster, Max; Feleke, Bethlehem; Said-Moorhouse, Lauren (November 2023). "King Charles acknowledges Kenya's colonial-era suffering but stops short of apologizing". CNN. Archived from the original on 1 December 2023. Retrieved 6 February 2024.

- ^ Coughlan, Sean (26 January 2024). "King Charles in hospital for prostate treatment". BBC News. Archived from the original on 26 January 2024. Retrieved 26 January 2024.

- ^ Coughlan, Sean (5 February 2024). "King Charles III diagnosed with cancer, Buckingham Palace says". BBC News. Archived from the original on 5 February 2024. Retrieved 5 February 2024.

- ^ Trapper, James (10 February 2024). "King Charles expresses 'lifelong admiration' for cancer charities". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 February 2024.

- ^ Holden, Michael (11 March 2024). "King Charles hails Commonwealth but misses annual celebrations". Reuters. Retrieved 11 March 2024.

- ^ "Queen Camilla steps in for King at Royal Maundy Service in Worcester". ITV News. 28 March 2024. Retrieved 28 March 2024.

- ^ Leigh, Suzanne; Gallagher, Charlotte (31 March 2024). "King Charles appears in public at Easter Sunday church service". BBC News. Retrieved 31 March 2024.

- ^ Smout, Alistair; Mills, Sarah; Gumuchian, Marie-louise (16 September 2022). "With Charles king, his Prince's Trust youth charity goes on". Reuters. Archived from the original on 26 November 2022. Retrieved 26 November 2022.

- ^ a b "The Prince's Charities". Clarence House. Archived from the original on 26 September 2010. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ^ Mackreal, Kim (18 May 2012). "Prince Charles rallies top-level support for his Canadian causes". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on 20 May 2012. Retrieved 22 May 2012.

- ^ a b "His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales". Department of Canadian Heritage. Government of Canada. Archived from the original on 22 September 2008. Retrieved 12 October 2008.

- ^ "Contact Us". The Prince's Charities Australia. Archived from the original on 9 August 2014. Retrieved 22 January 2013.

- ^ 딤블 by 1994, p. 250.

- ^ "Welcome". FARA Enterprises. Archived from the original on 12 October 2010. Retrieved 25 September 2012.

- ^ Quinn, Ben (29 August 2021). "Prince of Wales charity launches inquiry into 'cash for access' claims". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 30 August 2021.

- ^ Foster, Max; Said-Moorhouse, Lauren (6 September 2021). "Former aide to Prince Charles steps down over cash-for-honors scandal". CNN. Archived from the original on 7 September 2021. Retrieved 7 September 2021.

- ^ Butler, Patrick (18 November 2021). "Inquiry into foundation linked to Prince of Wales launched". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 18 November 2021. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- ^ Montebello, Leah (16 February 2022). "Breaking: Met Police investigate cash-for-honours allegations against Prince Charles' charity". City A.M. Archived from the original on 16 February 2022. Retrieved 16 February 2022.; O'Connor, Mary (16 February 2022). "Police to investigate Prince Charles' charity". BBC News. Archived from the original on 16 February 2022. Retrieved 17 February 2022.

- ^ Gadher, Dipesh; Gabriel Pogrund; Megan Agnew (19 November 2022). "Cash-for-honours police pass file on King's aide Michael Fawcett to prosecutors". The Sunday Times. Archived from the original on 28 March 2023. Retrieved 28 March 2023.

- ^ Ward, Victoria (21 August 2023). "Cash-for-honours investigation into King Charles's charity dropped". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 21 August 2023. Retrieved 21 August 2023.

- ^ Pogrund, Gabriel; Keidan, Charles; Faulkner, Katherine (25 June 2022). "Prince Charles accepted €1m cash in suitcase from sheikh". The Times. Archived from the original on 25 June 2022. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ^ a b Connett, David (25 June 2022). "Prince Charles is said to have been given €3m in Qatari cash". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 25 June 2022. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ^ "Prince Charles: Charity watchdog reviewing information over reports royal accepted carrier bag full of cash as a charity donation from Qatar ex-PM". Sky News. 27 June 2022. Archived from the original on 27 June 2022. Retrieved 27 June 2022.

- ^ Coughlan, Sean (20 July 2022). "Prince Charles: No inquiry into £2.5m cash donation to his charity". BBC News. Archived from the original on 20 July 2022. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- ^ Pogrund, Gabriel; Charles Keidan (30 July 2022). "Prince Charles accepted £1m from family of Osama bin Laden". The Times. Archived from the original on 30 July 2022. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ^ "Prince Charles dined with Bin Laden's brother". The Guardian. 13 October 2001. Archived from the original on 30 July 2022. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

The Prince of Wales had dinner with a brother of Osama bin Laden two weeks after the September 11th attacks, St James' Palace said today.

- ^ Furness, Hannah (1 August 2022). "Prince Charles's charity won't be investigated for accepting bin Laden family £1m donation". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 1 August 2022. Retrieved 1 August 2022.

- ^ Fraser, John (26 April 2023). "What the reign of King Charles III means for Canada". Canadian Geographic. Royal Canadian Geographical Society. Archived from the original on 27 April 2023. Retrieved 29 April 2023.

- ^ Dulcie, Lee (20 May 2022). "Prince Charles: We must learn from indigenous people on climate change". BBC News. Archived from the original on 29 April 2023. Retrieved 29 April 2023.

- ^ "Prince Charles commits to 'listening' to Indigenous peoples as Canadian royal tour begins". Global News. 17 May 2022. Archived from the original on 29 April 2023. Retrieved 29 April 2023.

- ^ Katawazi, Miriam (27 June 2017). "Prince Charles's charities work to undo past wrongs against Indigenous people through reconciliation". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on 29 April 2023. Retrieved 29 April 2023.

- ^ Brewster, Murray (24 June 2022). "Commonwealth countries could learn from Canada's reconciliation efforts, Prince Charles says". CBC News. Archived from the original on 29 April 2023. Retrieved 29 April 2023.

- ^ "Prince Charles tells Commonwealth of sorrow over slavery". BBC News. 24 June 2022. Archived from the original on 24 June 2022. Retrieved 29 April 2023.

- ^ Evans, Rob (26 March 2015). "Supreme court clears way for release of secret Prince Charles letters". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 27 March 2015. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- ^ "Cabinet Office". www.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 18 December 2020. Retrieved 15 May 2015.; "Prince Charles's black spider memos in 60 seconds". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 16 May 2015. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ^ "Prince Charles, the toothfish and the toothless 'black spider' letters". The Washington Post. 14 May 2015. Archived from the original on 6 April 2018. Retrieved 23 May 2015.

- ^ Spector, Dina (13 May 2015). "There are 3 reasons why Britain might be completely underwhelmed by Prince Charles' black spider memos". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 23 April 2019. Retrieved 23 May 2015.

- ^ Jenkins, Simon (13 May 2015). "The black spider memos: a royal sigh of woe at a world gone to the dogs". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 14 June 2018. Retrieved 23 May 2015.

- ^ Roberts, Andrew (13 May 2015). "All the 'black spider memos' expose is the passion and dignity of Prince Charles". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 15 May 2015. Retrieved 23 May 2015.

- ^ Booth, Robert (15 December 2015). "Revealed: Prince Charles has received confidential cabinet papers for decades". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 10 January 2017. Retrieved 22 December 2016.

- ^ a b Boseley, Matilda (24 October 2020). "Prince Charles's letter to John Kerr reportedly endorsing sacking of Whitlam condemned". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 13 February 2022. Retrieved 12 February 2022.

- ^ Dathan, Matt; Low, Valentine (10 June 2022). "Prince Charles: Flying migrants to Rwanda is 'appalling'". The Times. Archived from the original on 9 July 2022. Retrieved 11 June 2022.(구독 필수)

- ^ Wheeler, Caroline; Shipman, Tim; Nikkah, Roya (12 June 2022). "Charles won't be Prince Charming if he keeps on meddling, say ministers". The Times. Archived from the original on 2 July 2022. Retrieved 3 July 2022.(가입 필요)

- ^ a b "Charles, Prince of Wales". Planetizen. 13 September 2009. Archived from the original on 16 March 2012. Retrieved 31 March 2012.

- ^ a b "A speech by HRH The Prince of Wales at the 150th anniversary of the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA), Royal Gala Evening at Hampton Court Palace". Prince of Wales. 30 May 1984. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 17 June 2012.

- ^ a b "HRH visits the Oxford Centre for Islamic Studies new building". The Prince of Wales. 9 February 2005. Archived from the original on 19 June 2007. Retrieved 15 December 2008.

- ^ Capps, Kriston (9 September 2022). "King Charles III, City Maker". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 16 May 2023. Retrieved 19 May 2023.

- ^ "The Prince of Wales Accepts Vincent Scully Prize". artdaily.com. Archived from the original on 23 May 2013. Retrieved 19 April 2013.

- ^ Harper, Phineas (21 September 2022). "King Charles's endless meddling in architectural politics has accomplished nothing". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 20 October 2022. Retrieved 5 May 2023.

- ^ Graham, Hugh (30 June 2019). "Exclusive: Prince Charles, the new Poundbury and his manifesto to solve the housing crisis". The Times. Archived from the original on 6 August 2021. Retrieved 22 June 2023.

- ^ Cramb, Auslan (28 June 2007). "Charles saves Dumfries House at 11th hour". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 13 June 2008. Retrieved 28 June 2007.

- ^ Foyle, Johnathan (27 June 2014). "Dumfries House: training the unemployed". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 13 December 2022. Retrieved 4 May 2023.

- ^ "Prince Charles to build wellbeing centre at Dumfries House". The Scotsman. 12 September 2017. Archived from the original on 7 October 2022. Retrieved 4 May 2023.

- ^ Freyberg, Annabel (27 May 2011). "Dumfries House: a Sleeping Beauty brought back to life by the Prince of Wales". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 30 May 2011.

- ^ Marrs, Colin (16 September 2016). "Prince Charles's stalled 'Scottish Poundbury' under scrutiny". Architect's Journal. Archived from the original on 6 February 2024. Retrieved 4 May 2023.

- ^ The Budget Plan 2007: Aspire to a Stronger, Safer, Better Canada (PDF). Department of Finance. Queen's Printer for Canada. 19 March 2007. p. 99. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 June 2009. Retrieved 1 May 2012.

- ^ "Heritage Services". Heritage Canada Foundation. Archived from the original on 14 September 2008. Retrieved 12 October 2008.

- ^ Hales, Linda (26 October 2005). "Prince Charles to Accept Scully Prize at Building Museum". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 19 April 2013.; "The Prince of Wales Accepts Vincent Scully Prize". artdaily.com. Archived from the original on 23 May 2013. Retrieved 19 April 2013.

- ^ "Prince Charles honored for his architectural patronage". Notre Dame News. 7 February 2012. Archived from the original on 24 August 2020. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- ^ "About Us". Carpenters' Company website. Archived from the original on 17 July 2012. Retrieved 17 June 2012.

- ^ "Prince Charles Faces Opponents, Slams Modern Architecture". Bloomberg L.P. 12 May 2009. Retrieved 20 June 2009.

- ^ "Architects urge boycott of Prince Charles speech". NBC News. 11 May 2009. Archived from the original on 2 January 2014. Retrieved 20 June 2009.; "Architects to hear Prince appeal". BBC News. 12 May 2009. Archived from the original on 2 December 2010. Retrieved 20 June 2009.

- ^ Booth, Robert (15 June 2009). "Prince Charles's meddling in planning 'unconstitutional', says Richard Rogers". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 24 December 2013. Retrieved 20 June 2009.

- ^ a b "Chelsea Barracks developer apologises to Prince Charles". BBC News. 24 July 2010. Archived from the original on 26 June 2022. Retrieved 26 June 2022.

- ^ "Prince Charles honored with HMS's Global Environmental Citizen Award". The Harvard Gazette. 1 February 2007. Archived from the original on 10 March 2021. Retrieved 11 October 2021.

- ^ Low, Valentine (19 February 2020). "No one is calling my fears over the climate dotty now, says Prince Charles". The Times. Archived from the original on 8 August 2022. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- ^ Ferran, Lee (20 September 2010). "Prince Charles Eavesdrops on Tourists, Speaks to Plants". ABC News. Archived from the original on 1 June 2022. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- ^ a b Vidal, John (15 May 2002). "Charles designs 'healing garden'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 15 December 2022. Retrieved 15 December 2022.

- ^ a b "Our Story". Duchyoriginals.com. Archived from the original on 5 October 2012. Retrieved 22 September 2012.

- ^ Rainey, Sarah (12 November 2013). "Why Prince Charles's Duchy Originals takes the biscuit". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 1 April 2021. Retrieved 30 July 2014.

- ^ 스판덴부르크와 모저 2004, 페이지 32

- ^ Rosenbaum, Martin (23 January 2019). "Prince Charles warned Tony Blair against GM foods". BBC News. Archived from the original on 10 May 2022. Retrieved 10 May 2022.

- ^ Myers, Joe (22 January 2020). "This member of the British Royal Family has a vital message if we are to save the planet". World Economic Forum. Archived from the original on 2 November 2021. Retrieved 2 November 2021.

- ^ Inman, Phillip (3 June 2020). "Pandemic is chance to reset global economy, says Prince Charles". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 17 November 2020. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- ^ Emma Dooney (6 June 2023). "King Charles hailed 'ahead of his time' for passionate statement on his dietary preferences". Woman and Home Magazine. Archived from the original on 4 July 2023. Retrieved 4 July 2023.

- ^ Prince Charles and His Battle for Our Planet. BBC World News. Archived from the original on 8 December 2021. Retrieved 8 December 2021.; Garlick, Hattie (11 October 2021). "How to do the Prince Charles diet – and eat the perfect amount of meat and dairy". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 8 December 2021.

- ^ White, Stephen; Tetzlaff-Deas, Benedict; Munday, David (12 September 2022). "King Charles doesn't eat lunch and works until midnight". CornwallLive. Archived from the original on 5 October 2022. Retrieved 5 October 2022.

- ^ "King Charles: Foie gras banned at royal residences". BBC News. 18 November 2022. Archived from the original on 15 December 2022. Retrieved 15 December 2022.

- ^ Burchfield, Rachel (20 September 2023). "King Charles Has "A Strict List of Culinary Demands" for Banquet Tonight at Palace of Versailles During State Visit to France". Marie Claire Magazine. Archived from the original on 29 October 2023. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ^ "Holy oil to be used to anoint King during Coronation is vegan friendly". The Independent (UK). 4 March 2023. Archived from the original on 28 March 2023. Retrieved 28 March 2023.

- ^ Walker, Peter (31 October 2021). "Cop26 'literally the last chance saloon' to save planet – Prince Charles". The Guardian. OCLC 60623878. Archived from the original on 31 October 2021. Retrieved 31 October 2021.

- ^ Elbaum, Rachel (1 November 2021). "Prince Charles calls for 'warlike footing' in climate fight as world leaders gather". NBC. Archived from the original on 2 November 2021. Retrieved 2 November 2021.

- ^ "King Charles will not attend climate summit on Truss advice". BBC News. 1 October 2022. Archived from the original on 13 December 2022. Retrieved 1 October 2022.

- ^ Paddison, Laura (1 December 2023). "King Charles says world heading for 'dangerous uncharted territory' at global leaders summit". CNN. Archived from the original on 19 December 2023. Retrieved 19 December 2023.

- ^ "The Prince of Wales launches climate action scholarships for small island nation students". Prince of Wales. 14 March 2022. Archived from the original on 14 March 2022. Retrieved 1 April 2022.

- ^ 어바웃 어스 2021년 5월 17일 Wayback Machine The Prince's Country Fund – 2018년 12월 26일

- ^ Feder, Barnaby J. (9 January 1985). "More Britons Trying Holistic Medicine". The New York Times. OCLC 1645522. Archived from the original on 1 June 2013. Retrieved 12 October 2008.

- ^ a b Rawlins, Richard (March 2013). "Response to HRH". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 106 (3): 79–80. doi:10.1177/0141076813478789. PMC 3595413. PMID 23481428.; Ernst, Edzard (2022). Charles, the alternative prince an unauthorised biography. Imprint Academic. ISBN 978-1-78836-070-8.; Weissmann, Gerald (September 2006). "Homeopathy: Holmes, Hogwarts, and the Prince of Wales". The FASEB Journal. 20 (11): 1755–1758. doi:10.1096/fj.06-0901ufm. PMID 16940145. S2CID 9305843.

- ^ Bower, Tom (2018). ""Chapter 6"". The Rebel Prince, The Power, Passion and Defiance of Prince Charles. London: William Collins. ISBN 978-0-00-829173-0.

- ^ The Prince of Wales (December 2012). "Integrated health and post modern medicine". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 105 (12): 496–498. doi:10.1258/jrsm.2012.12k095. PMC 3536513. PMID 23263785.; Hamilton-Smith, Anthony (9 April 1990). "Medicine: Complementary and Conventional Treatments". Archived from the original on 13 September 2022. Retrieved 13 September 2022.; Rainey, Sarah (12 November 2013). "Prince Charles and homeopathy: crank or revolutionary?". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 14 February 2021. Retrieved 22 June 2022.

- ^ Carr-Brown, Jonathon (14 August 2005). "Charles's 'alternative GP' campaign stirs anger". The Times. Archived from the original on 22 June 2018. Retrieved 11 March 2009. (가입 필요)

- ^ Revill, Jo (27 June 2004). "Now Charles backs coffee cure for cancer". The Observer. Archived from the original on 27 September 2013. Retrieved 19 June 2007.

- ^ Singh, Simon; Ernst, Edzard (2008). Trick or Treatment: Alternative Medicine on Trial. Bantam Press.

- ^ a b Walker, Tim (31 October 2009). "Prince Charles lobbies Andy Burnham on complementary medicine for NHS". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 27 March 2010. Retrieved 1 April 2010.

- ^ Colquhoun, David (12 March 2007). "HRH 'meddling in politics'". DC's Improbable Science. Archived from the original on 15 November 2010. Retrieved 6 November 2009.

- ^ Hawkes, Nigel; Henderson, Mark (1 September 2006). "Doctors attack natural remedy claims". The Times. Archived from the original on 22 June 2018. Retrieved 22 June 2018. (가입 필요)

- ^ "Statement from the Prince's Foundation for Integrated Health". FIH. 30 April 2010. Archived from the original on 2 February 2013.

- ^ a b Sample, Ian (2 August 2010). "College of Medicine born from ashes of Prince Charles's holistic health charity". The Guardian. OCLC 60623878. Archived from the original on 3 August 2010. Retrieved 24 September 2012.

- ^ Colquhoun, David (29 October 2010). "Don't be deceived. The new "College of Medicine" is a fraud and delusion". Archived from the original on 11 September 2012. Retrieved 24 September 2012.; Hawkes, Nigel (29 October 2010). "Prince's foundation metamorphoses into new College of Medicine". British Medical Journal. 341 (1): 6126. doi:10.1136/bmj.c6126. ISSN 0959-8138. S2CID 72649598. Archived from the original on 2 December 2010. Retrieved 17 December 2010.

- ^ "HRH The Prince of Wales is announced as College of Medicine Patron". College of Medicine. 17 December 2019. Archived from the original on 25 June 2022. Retrieved 22 June 2022.

- ^ "Charles decides to retire from polo playing at 57". The Guardian. 17 November 2005. OCLC 60623878. Archived from the original on 14 May 2023. Retrieved 14 May 2023.

- ^ Revesz, Rachel (24 July 2017). "Prince Charles secret letters to Tony Blair over fox hunting get information commissioner's green light for publishing". The Independent (UK). Archived from the original on 21 April 2023. Retrieved 21 April 2023.

- ^ "Prince Charles takes sons hunting". BBC News. 30 October 1999. Archived from the original on 26 July 2008. Retrieved 21 April 2023.

- ^ Ashton, John B.; Latimer, Adrian, eds. (2007). A Celebration of Salmon Rivers: The World's Finest Atlantic Salmon Rivers. Stackpole Books. p. 7. ISBN 978-1-873674-27-7.

- ^ "Prince of Wales supports Burnley football club". The Daily Telegraph. 15 February 2012. Archived from the original on 6 April 2012. Retrieved 29 September 2012.

- ^ "History". National Rifle Association. Archived from the original on 1 September 2022. Retrieved 13 October 2022.

- ^ "National Rifle Association". Prince of Wales. Archived from the original on 4 August 2020. Retrieved 13 October 2022.

- ^ Hallemann, Caroline (5 November 2019). "Vintage Photos of Prince Charles at Cambridge Prove Meghan Markle Isn't the Only Actor in the Royal Family". Town & Country. Archived from the original on 23 May 2022. Retrieved 22 June 2022.

- ^ "Performing Arts". Prince of Wales official website. Archived from the original on 21 June 2012. Retrieved 17 June 2012.

- ^ "The Prince of Wales visits the BFI Southbank". Prince of Wales official website. 6 December 2018. Archived from the original on 29 September 2021. Retrieved 28 September 2021.

- ^ "TRH continue their annual tour of Wales". Prince of Wales website. Archived from the original on 19 November 2007. Retrieved 19 April 2013.

- ^ a b Holland, Oscar (12 January 2022). "Prince Charles exhibits dozens of his watercolors, saying painting 'refreshes the soul'". CNN. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 13 January 2022.

- ^ "Prince Charles wins art award". BBC News. 12 December 2001. Archived from the original on 28 September 2013. Retrieved 22 September 2013.

- ^ "The Royal Academy Development Trust". Royal Academy. Archived from the original on 21 March 2019. Retrieved 25 January 2019.

- ^ "D-Day portraits commissioned by Prince Charles go on display". BBC News. 6 June 2015. Archived from the original on 22 November 2022. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- ^ Coughlan, Sean (10 January 2022). "Prince Charles commissions Holocaust survivor portraits". BBC News. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 11 January 2022.