파키스탄

Pakistan파키스탄 이슬람 공화국 | |

|---|---|

| 좌우명:딘, 잇티하드, 나잠 ایمان، اتحاد، نظم "신앙, 단결, 규율"[2] | |

| 국가: 카우무 타라나 قَومی ترانہ "애국가" | |

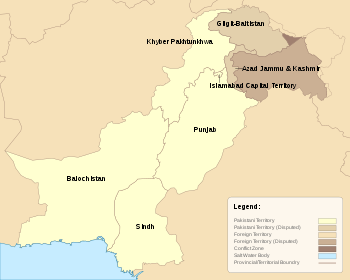

파키스탄에 의해 통제된 땅은 짙은 녹색으로 표시되고, 소유는 되었지만 연한 녹색으로 표시되지는 않음 | |

| 자본 | 이슬라마바드 33°41′30″N 73°03′00″E/33.69167°N 73.05,000°E |

| 가장 큰 도시 | 카라치 24°51′36″N 67°00′36″E/24.86000°N 67.01000°E |

| 공용어 | |

| 지역 언어 | |

| 민족군 (2020[3]) | |

| 종교 (2017[5]) | |

| 데모닉 | 파키스탄인 |

| 정부 | 연방 이슬람교 의회 공화국 |

• 대통령 | 아리프 알비 |

• 총리 | 임란 칸 |

• 상원 의장 | 사디크 산자니 |

• 국회의장 | 아사드 카이저 |

• 대법원장 | 우마르 아타 반디알 |

| 입법부 | 의회 |

• 윗집 | 상원 |

• 하원 | 국회 |

| 독립 | |

• 도미니언 | 1947년 8월 14일 |

• 이슬람 공화국 | 1956년 3월 23일 |

| 1972년 1월 12일 | |

• 현행 헌법 | 1973년 8월 14일 |

| 면적 | |

• 합계 | 881,913 km2 (1989 sq mi)[a][7] (33번째) |

• 물(%) | 2.86 |

| 인구 | |

• 2021년 추정 | |

• 2017년 인구 조사 | |

• 밀도 | 244.4/km2(633.0/sq mi)(56번째) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2021년 견적 |

• 합계 | |

• 1인당 | |

| GDP (iii) | 2021년 견적 |

• 합계 | |

• 1인당 | |

| 지니 (2018) | 중간의 |

| HDI (2019) | 중 · 152위 |

| 통화 | 파키스탄 루피(PKR) |

| 시간대 | UTC+05:00(PKT) |

| DST가 관찰되지 않음 | |

| 날짜 형식 |

|

| 드라이빙 사이드 | 남겨진[12] |

| 호출 코드 | +92 |

| ISO 3166 코드 | PK |

| 인터넷 TLD | |

공식적으로 파키스탄의 이슬람 공화국인 [c]파키스탄은 남아시아에 있는 나라다.[d]인구 2억2700만명에 육박하는 세계 5위의 인구국가로 세계에서 두 번째로 많은 무슬림 인구를 보유하고 있다.파키스탄은 면적 기준으로 33번째로 큰 나라로 88만1913㎢(34만509㎢)에 이른다.아라비아 해와 오만 만을 따라 남쪽으로 1046km(650마일)의 해안선을 가지고 있으며 동쪽으로는 인도, 서쪽으로는 아프가니스탄, 남서쪽으로는 이란, 북동쪽으로는 중국과 국경을 접하고 있다.북쪽의 아프가니스탄의 와칸 회랑에 의해 타지키스탄과 좁게 분리되어 있으며, 오만과 해상 국경을 공유하기도 한다.

파키스탄은 발로치스탄의 8,500년 된 신석기시대 메르가르 유적지와 [13]구세계의 문명 중 가장 광범위한 청동기 시대의 인더스 계곡 문명을 포함한 여러 고대 문화의 현장이다.[14][15]여러 왕국들과 왕조의 아케메 네스 등 파키스탄의 현대 국가가 되어 있어 그 지방은 영역, 간략하게 알렉산더 대왕의; 된 셀리우 시드이었다, 마우리아, 쿠샨, 굽타;[16]은 우마이야 왕조는 남쪽 지역에서, 힌두 샤히, 가즈나 왕조, 델리 술탄 왕조, Mughals,[17]은 Durranis., Sikh 엠파이어, British East India Company, 그리고 가장 최근에는 1858년부터 1947년까지의 British Indian Empire를 지배한다.

1946년 영국령 인도 무슬림들의 조국을 구한 파키스탄 운동과 올인도 무슬림 연맹의 선거 승리에 고무된 파키스탄은 1947년 대영 인도 제국의 분단 이후 독립을 쟁취하였는데, 이 분단은 무슬림 주요 지역에 별도의 국가 지위를 부여하고 유례없는 미사를 동반하였다.이주와 인명 [18]손실처음에 영국 연방의 도미니언이었던 파키스탄은 1956년에 공식적으로 헌법 초안을 작성했고, 선언된 이슬람 공화국으로 부상했다.1971년 동파키스탄의 외신은 9개월에 걸친 내전 끝에 방글라데시의 새로운 국가로 분리되었다.그 후 40년 동안 파키스탄은 민간인과 군사, 민주와 권위주의, 상대적으로 세속주의, 이슬람주의자를 번갈아 묘사하고 있지만 복잡하게 묘사되어 있는 정부들에 의해 통치되어 왔다.[19]파키스탄은 2008년 민간정부를 선출했고, 2010년 정기선거와 함께 의회제도를 채택했다.[20]

파키스탄은 지역[21][22][23] 및 중간 강국으로 세계 6위의 상비군을 보유하고 있다.[24][25][26]이 나라는 핵보유국으로 선언된 국가로, 신흥 경제국과 성장 주도국 가운데 서열화되어 있으며,[27] 중산층이 크고 빠르게 성장하고 있다.[28]독립 이후 파키스탄의 정치사는 정치·경제적 불안정은 물론 경제·군사적으로도 상당한 성장기를 보낸 것이 특징이다.이 나라는 인종적, 언어적으로 다양한 나라인데, 지리적으로나 야생동물도 이와 유사하게 다양하다.하지만, 한국은 빈곤, 문맹, 부패, 테러리즘을 포함한 도전에 직면하고 있다.[29]파키스탄은 유엔, 상하이협력기구, 이슬람협력기구, 영연방, 남아시아지역협력협회, 이슬람군사대테러연합(ISA)의 회원국으로, 미국의 주요 비NATO 동맹국으로 지정돼 있다.

어원

파키스탄이라는 이름은 말 그대로 우르두와 페르시아어로 "순수한 자에 풍부한 땅" 또는 "순수한 자가 많은 땅"을 의미한다.페르시아어, 파슈토어로 '순수'를 뜻하는 ک ((파크)를 지칭한다.[30]접미사 ـتان( -stan으로 영어로 번역)은 페르시아어로, "가득히 많은 곳"[31] 또는 "무엇이든 풍부한 곳"[32]을 의미한다.

그 나라의 이름은 1933년 Choudhry Rahmat 알리, 파키스탄 운동 운동가, 팜플렛에 지금이나지 마라, 여기 약어("누가 PAKISTAN에 사는 30만 무슬림 형제들")[33]고 영국령 인도 제국의 다섯 북부 지역과, 펀자브, Afghania, 카슈미르, 신드 주, 그리고 Baluchista의 이름에를 참조를 사용하여 이것을 발표에 의해 만들어졌다.n.[33]

역사

초기 및 중세 시대

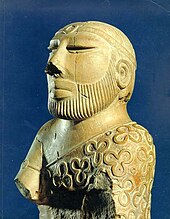

남아시아에서 가장 초기 인류 문명의 일부는 오늘날의 파키스탄을 아우르는 지역에서 유래되었다.[34]이 지역에서 가장 일찍 알려진 거주자는 하부 구석기 시대 소아니아인으로, 그 중 석기는 펀자브 소안 계곡에서 발견되었다.[35]오늘날 파키스탄의 대부분을 차지하고 있는 인더스 지역은 하라파와 모헨조 다로의 신석기 메르가르와[36] 청동기 시대의 인더스 계곡 문명화[37][38] (기원전 2,800–1,800년)를 포함한 여러 고대 문화의 연속적인 장소였다.[39]

베딕 시대(기원전 1500~500년)는 인도-아리아 문화에 의해 특징지어졌다. 이 시기에는 힌두교와 관련된 가장 오래된 경전인 베다(Vedas)가 작곡되었고, 이후 이 문화는 이 지역에서 잘 정착되었다.[40]Multan은 힌두교의 중요한 순례 중심지였다.[41]베딕 문명은 기원전 1000년경에 설립된 펀자브 지방의 타실라인 고대 간드하란 도시 타케다실라에서 번성했다.[42][36]연이은 고대 제국과 왕국은 페르시아 아차메니드 제국(기원전 519년경), 기원전[43] 326년 알렉산더 대제국과 찬드라굽타 마우리아에 의해 건국되고 기원전 185년까지 아소카 대제가 확장한 마우리아 제국이 이 지역을 통치했다.박트리아의 데메트리오스(기원전 180–165년)가 세운 인도-그리스 왕국은 간드라, 펀자브(Punjab)를 포함하였고, 메난데르(기원전 165–150년)에 이르러 이 지역의 그레코-불교 문화가 번성하였다.[36][44]타실라는 기원전 6세기 후반에 설립된 세계에서 가장 초기 대학 중 하나와 고등교육 센터를 가지고 있었다.[45][46]이 학교는 큰 기숙사가 없는 수도원이나 개인주의적으로 종교지도를 하는 강의실 등으로 구성되었다.[46]고대 대학은 알렉산더 대왕의 침략군에 의해 기록되었고, CE 4, 5세기 중국 순례자들에 의해서도 기록되었다.[47]

전성기에 신드의 라이 왕조(489–632 CE)가 이 지역과 주변 영토를 지배했다.[48]팔라 왕조는 다르마팔라와 데바팔라 휘하에 현재의 방글라데시에서 북인도를 거쳐 파키스탄에 이르는 남아시아 전역에 걸친 마지막 불교 제국이었다.

이슬람 정복

아랍 정복자 무함마드 빈 카심은 CE 711년에 신드를 정복했다.[49][50]파키스탄 정부의 공식 연대표는 이를 파키스탄의 기틀이 마련됐지만[49][51] 19세기에 파키스탄의 개념이 도래한 시기로 주장하고 있다.중세 초기(642–1219 CE)는 이 지역에서 이슬람이 확산되는 것을 목격했다.이 기간 동안 수피 선교사들은 지역 불교와 힌두교 인구의 대다수를 이슬람교로 전환하는 데 중추적인 역할을 했다.[52]Upon the defeat of the Turk and Hindu Shahi dynasties which governed the Kabul Valley, Gandhara (present-day Khyber Pakhtunkwa), and western Punjab in the 7th to 11th centuries CE, several successive Muslim empires ruled over the region, including the Ghaznavid Empire (975–1187 CE), the Ghorid Kingdom, and the Delhi Sultanate (1206–1526 CE).델리 술탄국의 마지막 왕조인 로디 왕조는 무굴 제국(1526–1857 CE)으로 대체되었다.

무굴족은 페르시아 문학과 높은 문화를 도입하여 이 지역에 인도-페르시아 문화의 뿌리를 확립하였다.[53]현대 파키스탄의 지역에서는 무굴 시대의 주요 도시들이 라호르와 Theta가 있었는데,[54] 두 도시 모두 인상적인 무굴 건축물의 부지로 선정되었다.[55]16세기 초, 이 지역은 무굴 제국의 지배하에 남아 있었다.[56]

18세기에는 마라타 연맹과 이후 시크 제국의 경쟁 강대국의 출현과 더불어 1739년 이란의 나데르 샤와 1759년 아프가니스탄의 두라니 제국의 침략으로 무굴 제국이 서서히 해체되었다.벵골에서 성장하는 영국의 정치력은 아직 현대 파키스탄의 영토에 이르지 못했다.

식민지 시대

근대 파키스탄의 어느 영토도 영국이나 다른 유럽 열강의 지배를 받지 못하다가 1839년 당시 항구를 지키는 진흙 요새가 있던 작은 어촌 카라치가 함락되어 곧 뒤따르는 제1차 아프간 전쟁을 위한 항구와 군사 기지가 있는 은신처로 잡혀 있었다.신드의 나머지 부분은 1843년에 잡혀갔고, 그 후 수십 년 동안 먼저 동인도 회사, 그리고 그 후 대영제국 빅토리아 여왕의 포스트 세포이 무티니(1857–1858) 직할 통치 이후, 전쟁과 조약 등을 통해 일부 국가의 대부분을 차지하게 되었다.신드에서의 미아니 전투(1843년), 앵글로-시크 전쟁(1845년–1849년), 앵글로-아프간 전쟁(1839년–1919년)으로 끝난 발록 탈푸르 왕조를 상대로 한 전쟁이 주요 전쟁이었다.1893년까지 현대 파키스탄은 모두 대영 인도 제국의 일부가 되었고, 1947년 독립할 때까지 그렇게 남아 있었다.

영국 하에서는 근대 파키스탄이 주로 신드 사단과 펀자브 주, 발루치스탄 에이전시로 나뉘었다.다양한 왕자다운 주가 있었는데, 그중 가장 큰 주는 바하왈푸르였다.

1857년 벵골의 세포이 폭동으로 불리는 반란은 이 지역의 대영제국에 대한 주요 무장투쟁이었다.[57]힌두교와 이슬람교의 관계에서의 차이는 영국 인도에 큰 균열을 만들어 영국 인도에 동기부여된 종교폭력을 초래했다.[58]언어 논란은 힌두교도와 이슬람교도의 긴장을 더욱 고조시켰다.[59]힌두교 르네상스는 전통적인 힌두교에서 지식주의의 각성을 목격했고 영국 인도의 사회와 정치 영역에서 보다 확실한 영향력이 출현하는 것을 목격했다.[60]시드 아흐메드 칸 경이 힌두교 르네상스에 대항하기 위해 창설한 무슬림 지식운동은 양국론을 주창할 뿐만 아니라, 1906년 올인도 무슬림 연맹의 창설을 이끌었다.[61]인도국민회의의 반영국적 노력과는 대조적으로 무슬림연맹은 파키스탄의 미래 시민사회를 형성할 영국적 가치를 정치적 프로그램이 계승한 친영 운동이었다.[62]인도 의회가 주도한 대규모 비폭력 독립 투쟁은 대영제국에 대항한 시민 불복종 운동에서 수백만의 시위대를 참여시켰다.[63][64]

1930년대 인도 이슬람교도들의 과소표현과 정치에 대한 영국인들의 무관심이 우려되는 가운데 무슬림 연맹은 서서히 대중적인 인기를 끌었다.알라마 이크발은 1930년 12월 29일 대통령 연설에서 펀자브, 북서부 프론티어 주, 신드, 발루치스탄 주 등으로 구성된 '북서 무슬림 주도의 인도 국가 합병'을 주장했다.[65]1937~39년 동안 의회의 무슬림 이익에 대한 인식은 영국 지방정부들을 설득하여 파키스탄의 설립자인 무함마드 알리 진나를 설득하여 양국론을 지지하고 무슬림 연맹은 파키스탄으로 널리 알려진 셰르-이-방글라 A.K. 파즐룰 하케가 제시한 1940년 라호르 결의안을 채택하도록 이끌었다.결의.[61]제2차 세계 대전에서 이슬람 연맹에서 영국 교육을 받은 창립 아버지들과 진나는 영국의 전쟁 노력을 지지하면서 시드 경의 비전을 향해 일하면서 이에 대한 반대에 맞섰다.[66]

파키스탄 운동

1946년 선거는 무슬림 연맹이 무슬림들을 위한 의석의 90%를 획득하는 결과를 낳았다.따라서 1946년 선거는 사실상 인도 이슬람교도들이 무슬림 연맹이 승리한 국민투표인 파키스탄 창설에 대해 투표하도록 되어 있는 국민투표였다.이 승리는 신드 지주와 펀자브 지주의 후원에 의해 무슬림 연맹에 주어지는 지지에 의해 도움을 받았다.당초 무슬림 연맹의 유일한 대표라는 주장을 부인하던 인도국민회의는 이제 그 사실을 인정할 수밖에 없었다.[67]영국인들은 진나가 영국령 인도 전체 무슬림들의 유일한 대변인으로 부상한 만큼 진나의 견해를 고려하는 것 외에는 대안이 없었다.그러나 영국인들은 식민지 인도의 분할을 원치 않았고, 이를 막기 위한 마지막 노력으로 내각임무 계획을 고안했다.[68]

내각 임무가 실패하자 영국 정부는 1946~47년 영국 지배를 종식시키겠다는 뜻을 밝혔다.[69]자와할랄 네루와 아불 칼람 아자드 하원의원, 진나 전인도무슬림연맹원, 시크교도들을 대표하는 타라 싱 사부 등 영국 인도의 민족주의자들은 1947년 6월 인도의 총독인 버마 마운트배튼 경과 제안된 권력 이양 및 독립 조건에 동의했다.[70]1947년 영국이 인도의 분할에 합의함에 따라 1947년 8월 14일(이슬람 달력 1366년 라마단 27일)에 파키스탄의 근대국가가 수립되어 영국 인도의 무슬림 주요 지역인 동부와 서북부를 통합하였다.[64]발로치스탄 주, 동벵골 주, 북서부 프론티어 주, 서 펀자브 주, 신드 주를 구성했다.[61][70]

는 펀자브 주의 파티션을 수반하는 폭동에는 20만명에서 2,000,000[71]인들이 religions[72]는 동안 5만명의 이슬람 교도 여성들의 힌두교와 시크교도 남성들에게 강간 당한 납치된 사이에 인과 응보의 집단 학살로 설명한 것에서 죽음을 당했다고 생각하지만 3만 3천명의 힌두교와 시크교 또한 여성들의 같은 운명을 경험했다그 ha 있어다수의 [73]이슬람교도약 650만 명의 이슬람교도들이 인도에서 서파키스탄으로, 470만 명의 힌두교도와 시크교도들이 서파키스탄에서 인도로 이주했다.[74]그것은 인류 역사상 가장 큰 대규모 이주였다.[75]뒤이은 잠무와 카슈미르 주에 대한 분쟁은 결국 1947-1948년의 인도-파키스탄 전쟁을 촉발시켰다.[76]

독립과 현대 파키스탄

1947년 독립 후 이슬람연맹의 진나라는 초대 총통이자 초대 총통으로 취임하였으나 1948년 9월 11일 결핵으로 사망했다.[77]한편, 파키스탄의 건국의 아버지들은 리아카트 알리 칸 당 사무총장을 파키스탄의 초대 총리로 임명하는데 동의했다.1947년부터 1956년까지 파키스탄은 영연방 내의 군주국이었으며, 공화국이 되기 전에 두 명의 군주가 있었다.[78]

"너희는 자유롭다. 너는 너의 사원에 갈 자유가 있다. 너는 이 파키스탄 주의 모스크나 다른 곳이나 예배할 자유가 있다.여러분은 어떤 종교나 카스트나 신조에 속할 수 있다. 그것은 국가의 사업과는 아무런 관련이 없다."

—Muhammad Ali Jinnah's first speech to the Constituent Assembly of Pakistan[79]

파키스탄의 창조는 마운트배튼 경을 비롯한 많은 영국 지도자들에게는 결코 완전히 받아들여지지 않았다.[80]마운트배튼은 무슬림 연맹의 파키스탄 구상에 대한 지지와 믿음이 부족함을 분명히 드러냈다.[81]진나는 마운트배튼의 파키스탄 총독직 제의를 거절했다.[82]마운트배튼은 콜린스와 라피에르로부터 진나가 결핵으로 죽어가고 있다는 것을 알았더라면 파키스탄을 방해했을까라는 질문을 받았을 때, 그는 '아마도'라고 대답했다.[83]

마울라나 샤브비르 아흐마드 우스마니, 1949년 파키스탄의 샤이크 알-이슬람의 자리를 차지했던 존경받는 드반디 알림(슐랄라)과 자마티-이슬람의 마울라나 마우두디는 이슬람 헌법 요구의 중추적인 역할을 했다.마우두디는 제헌국회가 "하나님의 최고 주권"과 파키스탄의 샤리야 패권을 인정하는 명시적인 선언을 할 것을 요구했다.[84]

자마티-이슬라미와 울라마의 노력의 중요한 결과는 1949년 3월의 목표 결의안 통과였다.랴쿠아트 알리 칸이 파키스탄 역사상 두 번째로 중요한 단계라고 칭한 목표 결의안은 "우주 전체에 대한 주권은 전능하신 신에게만 있으며 그가 규정한 범위 내에서 행사된 것에 대해 국민을 통해 파키스탄 국가에 위임한 권한은 신성한 진리"라고 선언했다.st" 목표 결의안은 1956년, 1962년, 1973년 헌법의 서문으로 통합되었다.[85]

민주주의는 이스칸데르 미르자 대통령이 시행하던 계엄령으로 인해 교착상태에 빠졌고, 그는 아유브 칸 육군참모총장으로 교체되었다.1962년 대통령제를 채택한 뒤 1965년 제2차 인도와의 전쟁까지 예외적인 성장세를 보여 1967년 경기침체와 대대적인 국민 반대가 이어졌다.[86][87]1969년 아유브 칸의 통제를 강화한 야히아 칸 대통령은 동파키스탄에서 50만 명의 사망자를 낸 파괴적인 사이클론을 다루어야 했다.[88]

1970년, 파키스탄은 군사 통치에서 민주주의로의 전환을 기념하기 위해 독립 후 첫 민주 선거를 치렀으나, 동파키스탄 아와미 연맹이 파키스탄 인민당(PPP)을 상대로 승리한 후 야히아 칸과 군정 세력은 권력을 이양하기를 거부했다.[89][90]벵골 민족주의 운동에 대한 군사적 탄압인 서치라이트 작전은 동파키스탄에서 벵골 무크티 바히니 세력의 독립선언과 해방전쟁을 이끌어냈는데,[90][91] 서파키스탄에서는 해방전쟁과는 반대로 내전으로 묘사되었다.[92]

독립 연구자들은 방글라데시 정부가 사망자 수를 300만 명으로 집계하는 동안 이 기간 동안 30만~50만 명의 민간인이 사망한 것으로 추정하고 있는데,[93] 이는 현재 거의 보편적으로 지나치게 부풀려진 것으로 간주되고 있다.[94]루돌프 럼멜과 로나크 자한과 같은 일부 학자들은 양측이[95] 집단 학살을 저질렀다고 말하고, 리차드 시송과 레오 E와 같은 다른 학자들은 집단 학살을 저질렀다고 말한다.로즈는 대량학살은 없었다고 믿는다.[96]동파키스탄의 반란에 대한 인도의 지지에 대응하여 1971년 파키스탄 공군과 해군, 해병대의 인도 선제공격은 재래식 전쟁을 촉발하여 인도의 승리를 거두었고 동파키스탄은 방글라데시로 독립했다.[90]

파키스탄이 전쟁에서 항복함에 따라, 야히아 칸은 줄피카르 알리 부토 대통령 대신 대통령이 되었다. 야히야 칸은 헌법을 공포하고 나라를 민주주의로 가는 길에 올려놓기 위해 노력했다.민주주의 통치는 1972년부터 1977년까지 재개되었는데, 이는 자아의식, 지적 좌익주의, 민족주의, 그리고 전국적인 재건의 시대였다.[97]1972년 파키스탄은 외국의 침략을 막기 위한 목적으로 핵 억제 능력을 개발하려는 야심찬 계획에 착수했다. 파키스탄의 첫 원자력 발전소는 같은 해에 출범했다.[98][99]1974년 인도의 첫 핵실험에 대응하여 가속화된 이 충돌 프로그램은 1979년에 완성되었다.[99]

민주주의는 1978년 지아울하크 장군이 대통령이 된 좌파 PPP에 맞서 1977년 군사 쿠데타로 끝났다.1977년부터 1988년까지 지아 대통령의 기업화와 경제 이슬람화 이니셔티브는 파키스탄을 남아시아에서 가장 빠르게 성장하는 경제국 중 하나로 이끌었다.[100]파키스탄은 미국의 핵 프로그램을 구축하고 이슬람화를 늘리며 [101]자생적인 보수주의 철학이 부상하는 동안, 소련이 공산 아프가니스탄에 개입하는 것에 반대하는 무자비한 분파들에게 미국의 자원을 보조하고 분배하는 것을 도왔다.[102]파키스탄의 북서부 프런티어 주는 반소련 아프간 전투기들의 거점이 되었고, 이 지역의 영향력 있는 디반디 울라마는 '지하드'[103]를 격려하고 조직하는데 중요한 역할을 했다.

지아 대통령은 1988년 비행기 사고로 사망했으며, 줄피카르 알리 부토의 딸인 베나지르 부토 전 총리가 첫 여성 총리로 선출되었다.PPP에 이어 보수적인 파키스탄무슬림리그(N)가 뒤를 이었고, 이후 10년 동안 양당 지도부는 번갈아 집권하며 권력을 다투며 국가 상황이 악화되는 동안 경제지표가 1980년대와 달리 큰 폭으로 하락했다.이 시기는 스태그플레이션 장기화, 불안정성, 부패, 민족주의, 인도와의 지정학적 경쟁, 좌익-우익 이데올로기 충돌 등이 두드러진다.[104]1997년 선거에서 PML(N)이 초주요성을 확보함에 따라 1998년 5월 아탈 비하리 바즈페이 총리가 주도한 인도 명령의 2차 핵실험에 대한 보복으로 샤리프 인가 핵시험(참조:차가이-I, 샤가이-II)이 실시되었다.[105]

카르길 지구에서 두 나라 사이의 군사적 긴장이 1999년 카르길 전쟁으로 이어졌고, 시민-군사관계의 혼란은 페르베즈 무샤라프 장군이 무혈 쿠데타를 통해 정권을 장악할 수 있도록 했다.[106][107]무샤라프는 1999년부터 2001년까지 파키스탄을 통치했으며 2001년부터 2008년까지 대통령으로서 계몽주의, 사회 자유주의, 광범위한 경제 개혁,[108] 그리고 미국이 주도하는 테러와의 전쟁에 직접 관여했다.국회가 역사적으로 2007년 11월 15일 첫 5년 임기를 마쳤을 때, 새로운 선거는 선거관리위원회에 의해 소집되었다.[109]

2007년 베나지르 부토 암살 이후 PPP는 2008년 선거에서 가장 많은 표를 확보해 당원인 유사프 라자 길라니를 총리로 임명했다.[110]탄핵 위기에 처한 무샤라프 대통령은 2008년 8월 18일 사임했고 아시프 알리 자르다리가 뒤를 이었다.[111]사법부와의 충돌은 길라니가 2012년 6월 의회와 총리직을 박탈하는 계기가 되었다.[112]자체 재정 계산에 따르면 파키스탄이 테러와의 전쟁에 개입하는 데는 최대 1,180억 달러,[113] 6만 명의 사상자와 180만 명 이상의 실향민들이 희생되었다.[114]2013년 치러진 총선거에서는 PML(N)이 거의 다수를 달성했고, 이어 나와즈 샤리프가 총리로 선출돼 14년 만에 세 번째로 총리직에 복귀하는 등 민주적 전환이 이뤄졌다.[115]2018년 파키스탄 총선에서 임란 칸(PTI 의장)이 116석(총선 116석)으로 승리해 96표를 얻은 셰바즈 샤리프(PML(N) 회장)에게 176표를 얻어 파키스탄 제22대 총리에 당선됐다.[116]

이슬람의 역할

파키스탄은 이슬람이라는 이름으로 탄생한 유일한 나라다.[117]인도 무슬림들, 특히 미국 등 소수 민족이었던 영국령 인도 지방들 사이에서 압도적인 지지를 받았던 파키스탄의 사상은 이슬람연맹 지도부와 울라마(이슬람 성직자), 진나에 의해 이슬람 국가라는 관점에서 뚜렷하게 표현되었다.[118][119]진나는 울라마와 긴밀한 관계를 맺어왔고 그의 죽음과 함께 그의 죽음과 함께 오랑제브 다음으로 위대한 이슬람교도와 이슬람의 기치 아래 세계의 이슬람교도를 통합하고자 하는 사람으로 그러한 한 사람인 마울라나 샤브르 아마드 우스마니에 의해 묘사되었다.[120]

1949년 3월 하나님을 전 우주에 대한 유일 주권자로 선포한 목표 결의안은 파키스탄을 이슬람 국가로 변모시키기 위한 첫 번째 공식적인 단계를 대표했다.[121][85]이슬람연맹의 차우드리 칼리크자만 회장은 파키스탄은 이슬람의 모든 신자들을 하나의 정치부대로 끌어들인 후에야 진정한 이슬람 국가가 될 수 있다고 주장했다.[122]파키스탄 정치에 관한 초기 학자들 중 한 명인 키스 캘러드는 파키스탄인들이 이슬람 세계에서 목적과 전망의 본질적인 단결을 믿고 다른 나라 출신의 이슬람교도들이 종교와 국적의 관계에 대한 자신들의 견해를 공유할 것이라고 가정했다고 말했다.[123]

그러나 팔레스타인의 그랜드 무프티, 알-하즈 아민 알 후세이니, 무슬림 형제단 지도자들과 같은 이슬람교도들이 파키스탄에 끌리기는 했지만 이슬람이라는 통일된 이슬람 블록에 대한 파키스탄의 범이슬람주의 정서는 다른 이슬람 정부에 의해 공유되지 않았다.[124]이슬람국가들의 국제기구에 대한 파키스탄의 열망은 1970년대 이슬람회의(OIC)가 결성되면서 이루어졌다.[125]

정부는 이슬람 이념적 패러다임이 국가에 가해지고 있는의 최대의 야당이 벵골인 이슬람 교도들 동 Pakistan[126]의 교육을 받은 클래스의에서, 사회 과학자 Nasim 아마드 조드, 선호하는 세속 주의의 조사에 따르면이고 교육을 받은 서부의 파키스탄과는 달리 이슬람 정체성을 선호하는 경향이 있었던 민족 정체성에 집중했습니다.[127]이슬람 정당 자마트이슬람은 파키스탄을 이슬람 국가로 간주했고 벵골 민족주의는 용납될 수 없다고 믿었다.1971년 동파키스탄을 둘러싼 분쟁에서 자마-에-이슬라미족은 파키스탄군 편에서 벵골 민족주의자들과 싸웠다.[128]이 분쟁은 동파키스탄 분리독립과 방글라데시 독립으로 마무리되었다.

파키스탄의 첫 총선 이후, 1973년 헌법은 선출된 의회에서 만들어졌다.[129]헌법은 파키스탄을 이슬람 공화국, 이슬람교를 국교로 선포했다.또한 모든 법률은 쿠란과 순나에 규정된 이슬람의 해고에 따라 제정되어야 하며 그러한 해소에 반대하는 법률은 제정될 수 없다고 명시되어 있다.[130]1973년 헌법은 또한 이슬람의 해석과 적용을 통로로 하기 위해 샤리아트 법원, 이슬람 이데올로기 위원회와 같은 특정 기관을 만들었다.[131]

파키스탄의 좌파인 줄피카르 알리 부토 총리는 샤리아 법에 근거한 이슬람 국가 수립을 목표로 한 니잠-에-무스타파("예언자의 통치")[132]의 부활주의 깃발 아래 단결된 운동으로 통합되는 격렬한 반대에 직면했다.부토는 쿠데타로 전복되기 전에 일부 이슬람주의자들의 요구에 동의했다.[133]

1977년 쿠데타로 부토로부터 정권을 잡은 뒤 종교계 출신 지아울하크 장군은 이슬람 국가 수립과 샤리아 법 집행을 위해 헌신했다.[134][133]지아는 이슬람교 교리를 이용해 법률 사건을 심리하기 위해 샤리아트 사법 재판소와[135] 법원 벤치를[136] 따로 설치했다.[137]지아는 울라마(이슬람 성직자)와 이슬람 정당들의 영향력을 강화했다.[137]지아울하크는 군부와 데반디 기관[138] 사이에 강력한 동맹을 맺었고 대부분의 바를비 울라마와[139] 소수의 데반디 학자들만이 파키스탄의 창조를 지지했음에도 불구하고 이슬람 국가 정치는 바를비 대신 데반디(이후 알-에-하디스/살라피) 기관을 대부분 지지하게 되었다.[140]지아의 반시리아 정책으로 종파간 긴장이 고조되었다.[141]

퓨 리서치센터(Pew Research Center, PEW)의 여론조사에 따르면, 대다수의 파키스탄인들은 샤리아를 이 땅의 공식 법으로 만드는 것을 지지한다.[142]PEW는 또한 몇몇 이슬람 국가들을 대상으로 한 조사에서, 이집트, 인도네시아, 요르단과 같은 다른 나라의 이슬람교도들과 대조적으로 파키스탄인들이 그들의 국적보다 그들의 종교와 더 동일시하는 경향이 있다는 것을 발견했다.[143]

,기후지리

파키스탄의 지리와 기후는 매우 다양하며, 파키스탄에는 다양한 야생동물들이 서식하고 있다.[144]파키스탄의 면적은 881,913km2(340,509 평방 미)로 프랑스와 영국의 국토 면적과 거의 같다.분쟁지역인 카슈미르 지역을 어떻게 집계하느냐에 따라 이 순위는 다르지만 전체 면적으로는 33번째로 큰 나라다.Pakistan has a 1,046 km (650 mi) coastline along the Arabian Sea and the Gulf of Oman in the south[145] and land borders of 6,774 km (4,209 mi) in total: 2,430 km (1,510 mi) with Afghanistan, 523 km (325 mi) with China, 2,912 km (1,809 mi) with India and 909 km (565 mi) with Iran.[146]오만과 해상 국경을 공유하고 있으며,[147] 춥고 좁은 와칸 회랑에 의해 타지키스탄과 분리되어 있다.[148]파키스탄은 남아시아, 중동, 중앙아시아의 교차로에서 지정학적으로 중요한 위치를 차지하고 있다.[149]

지질학적으로 파키스탄은 인더스-트상포 봉수대에 위치하며 신드주와 펀자브주의 인도 지각판과 겹친다; 발로치스탄과 대부분의 카이버 팍툰화는 주로 이란 고원에 있는 유라시아 판 안에 있다.길깃발티스탄과 아자드 카슈미르는 인도판 가장자리를 따라 놓여 있어 격렬한 지진이 일어나기 쉽다.이 지역은 히말라야 지역에서 지진 발생률이 가장 높고 지진이 가장 크다.[150]남부의 해안 지역에서부터 북부의 빙하 산까지, 파키스탄의 풍경은 평야에서 사막, 숲, 언덕, 고원에 이르기까지 다양하다.[151]

파키스탄은 3개의 주요 지리적 지역으로 나뉘는데, 북부 고원, 인더스 강 평원, 발로치스탄 고원이다.[152]북부 고원지대에는 카라코람, 힌두쿠시, 파미르 산맥(파키스탄 산지 참조)이 들어 있는데, 이 산맥은 전 세계 모험가와 산악인들을 끌어들이는 8만 8천명 중 5명(8천 미터 이상 산봉우리 또는 2만 6천 250 피트)을 포함한 세계 최고봉 중 일부를 포함하고 있으며, 특히 K2(8,611 m)를 중심으로 한 산악인들이 몰려든다.또는 28,251ft)와 난가 파르밧(8,126m 또는 26,660ft)이다.[153]발로치스탄 고원은 서쪽에 있고 타르 사막은 동쪽에 있다.1609km(1,000mi)의 인더스 강과 그 지류가 카슈미르 지역에서 아라비아 해로 흘러간다.펀자브와 신드에는 그 주변에 충적평야가 넓게 펼쳐져 있다.[154]

기후는 열대에서 온대까지 다양하며, 남쪽 해안에는 건조 상태가 있다.비가 많이 와서 홍수가 잦은 장마철이 있고, 강수량이 현저히 적거나 아예 없는 건기가 있다.파키스탄에는 4개의 뚜렷한 계절이 있다: 12월부터 2월까지의 시원하고 건조한 겨울, 3월부터 5월까지의 뜨겁고 건조한 봄, 6월부터 9월까지의 여름 장마, 그리고 10월과 11월에는 후퇴하는 장마철이다.[61]강수량은 해마다 크게 달라지며, 대체 홍수와 가뭄의 패턴이 흔하다.[155]

식물과 동물

파키스탄의 풍광과 기후의 다양성으로 인해 다양한 나무와 식물들이 번성할 수 있다.숲은 극북산맥의 가문비나무, 소나무, 들쑥나무 등 침엽수 고산수목과 아갈핀수목부터 전국 대부분 지역의 낙엽수(예를 들어 술라이만산맥에서 발견된 뽕나무 같은 시샘)까지, 코코넛과 대추나무 등 야자수, 남부 펀자브, 발로치스탄, 신드 전 지역에 분포한다.서쪽 언덕에는 향나무, 타마리스크, 거친 풀, 문질러진 식물이 서식하고 있다.맹그로브 숲은 남쪽 해안을 따라 많은 해안 습지를 형성한다.[156]

침엽수림은 대부분의 북부와 북서부 고원에서 1,000~4,000m(3,300~13,100피트)에 이르는 고도에서 발견된다.발로치스탄의 황색 지역에서는 대추야자와 에페드라가 흔하다.펀자브와 신드 대부분의 지역에서 인더스 평야는 열대 및 아열대성 건조하고 습한 넓은 잎 숲뿐만 아니라 열대 및 황색 관목도 지원한다.이 숲들은 대부분 뽕나무, 아카시아, 유칼립투스로 이루어져 있다.[157]2010년에는 파키스탄의 약 2.2%인 168만7000ha(1만6870km2)가 산림으로 조성되었다.[158]

파키스탄의 동물들도 파키스탄의 다양한 기후를 반영한다.약 668종의 새들이 그곳에서 발견되는데,[159] 까마귀, 참새, 마이나스, 매, 팔콘, 독수리 등이다.고히스탄의 팔라스는 서부 트라고판 인구가 상당하다.[160]파키스탄에서 볼 수 있는 많은 새들은 유럽, 중앙아시아, 인도에서 온 철새들이다.[161]

남쪽 평야에는 몽구스, 작은 인디언 사향고양이, 산토끼, 아시아 자칼, 인도 판골린, 정글고양이, 사막고양이 등이 서식한다.인더스에는 강도 악어가, 주변에는 멧돼지, 사슴, 고슴도치, 작은 설치류 등이 있다.중앙 파키스탄의 모래 문질러진 땅에는 아시아 자칼, 줄무늬 하이에나, 야생 고양이, 표범이 서식하고 있다.[162][163]식물성 표지의 부족, 혹독한 기후, 사막에서 풀을 뜯는 것의 영향으로 야생동물은 위태로운 처지에 놓이게 되었다.Chincara는 여전히 많은 수의 철리스탄에서 발견될 수 있는 유일한 동물이다.파키스탄을 따라 적은 수의 닐가이가 발견된다.인도 국경과 철리스탄의 일부 지역.[162][164]마르코 폴로 양, 소변(야생양의 아종), 마코르 염소, 아이벡스 염소, 아시아 흑곰, 히말라야 갈색 곰 등 북부 산악지대에 매우 다양한 동물들이 살고 있다.[162][165][166]이 지역에서 발견된 희귀 동물들 중에는 눈표범과[165] 맹목적인 인더스 강 돌고래가 있는데, 이 중 약 1,100마리가 남아 있는 것으로 추정되며 신드의 인더스 강 돌고래 보호구역에서 보호되고 있다.[165][167]파키스탄에는 포유류 174종, 파충류 177종, 양서류 22종, 민물고기 198종, 무척추동물(곤충 포함) 5000종이 기록돼 있다.[159]

파키스탄의 동식물군은 많은 문제들로 고통받고 있다.파키스탄은 세계에서 두 번째로 삼림 벌채율이 높은 나라로, 사냥과 공해와 함께 생태계에 악영향을 끼쳤다.2019년 산림경관청렴도지수 평균점수는 7.42/10으로 세계 172개국 중 41위를 차지했다.[168]정부는 이러한 문제들을 해결하기 위해 많은 보호 구역, 야생 보호 구역, 그리고 게임 보호 구역들을 설립했다.[159]

정부와 정치

파키스탄의 정치적 경험은 본질적으로 인도 이슬람교도들이 영국 식민지화에 빼앗긴 권력을 되찾기 위한 투쟁과 관련이 있다.[169]파키스탄은 이슬람교를 국교로 하는 민주적인 의회 연방 공화국이다.[4]제1헌법은 1956년 채택되었으나 1958년 아유브 칸에 의해 중단되었고, 1962년 제2헌법으로 대체되었다.[64]완전하고 포괄적인 헌법이 1973년에 채택되었고, 1977년 지아울하크에 의해 중단되었다가 1985년에 복권되었다.이 헌법은 현 정부의 기틀을 다지는 국가의 가장 중요한 문서다.[146]파키스탄 군부는 파키스탄 정치사 전반에 걸쳐 주류 정치에 영향력을 행사해왔다.[64]1958–1971년, 1977–1988년, 1999–2008년 군사 쿠데타는 계엄령과 사실상의 대통령으로서 통치한 군 지휘관의 부과로 귀결되었다.[170]오늘날 파키스탄은 정부 부처간의 권력분립과 견제와 균형이 분명한 다당제 의회제도를 가지고 있다.최초의 성공적인 민주적 전환은 2013년 5월에 일어났다.파키스탄의 정치는 사회주의, 보수주의, 그리고 제3의 방법의 혼합된 생각들로 구성된 자생적 사회철학을 중심으로 하고 지배한다.2013년 치러진 총선을 기준으로 국내 3대 정당은 중도 우파 보수파인 파키스탄무슬림리그-N, 중도좌파 사회주의 PPP, 중도·제3지대인 파키스탄정의운동(PTI)이다.

- 국가 원수:선거인단에 의해 선출된 대통령은 의례적인 국가원수로서 파키스탄 군대의 민간인 통수권자(합참의장을 주요 군사고문으로 두고 있음)이지만, 군에서의 군사적 임명과 주요 확인은 재신임 후 수상에 의해 이루어진다.즉, 후보자의 장점과 성과에 대한 보고서 작성.사법부, 군, 의장, 합동참모본부, 입법부의 거의 모든 임명직 장교들은 대통령이 법률로 자문해야 하는 총리의 행정 확인을 요구한다.그러나, 사면하고 관용을 베풀 수 있는 권한은 파키스탄 대통령에게 있다.

- 입법부:양원제 입법부는 104명의 상원(상원)과 342명의 국회(하원)로 구성된다.국회의원들은 국회 선거구로 알려진 선거구를 대표하는 보편적 성인 참정권 하에서 제1기 포스트 제도를 통해 선출된다.헌법에 따르면 여성과 종교적 소수자를 위한 70석의 의석은 비례대표제에 따라 정당에 배분된다.상원 의원들은 도의원들에 의해 선출되며, 모든 지방이 동등한 대표성을 가진다.

- 임원:수상은 대개 다수결 정당의 대표나 국회 내 연정인 하원을 맡고 있다.수상은 정부의 수장으로서 국가의 최고 통치권자로서 활동하도록 지정되었다.국무총리는 정부 운영은 물론 장관과 고문으로 구성된 내각을 임명하고, 국무총리의 임원 승인이 필요한 고위 공무원의 임원 결정과 임명 및 추천을 받아 승인할 책임이 있다.

- 지방 정부:4개 도 각각은 최대 정당이나 연정의 대표가 총리로 선출되는 직접 선출 도의회가 장관으로 선출되는 등 비슷한 정부 체제를 갖추고 있다.장관들은 지방정부를 감독하고 지방내각을 관장한다.파키스탄에서는 각 지방에 서로 다른 여당이나 연정을 갖는 것이 일반적이다.지방 관료제는 국무총리가 임명하는 비서실장이 맡는다.도의회는 회계연도마다 도 재무장관이 공통적으로 제시하는 도비를 입법화하고 승인할 수 있는 권한을 갖고 있다.지방의 의례적인 수장인 지방 주지사들은 대통령이 임명한다.[146]

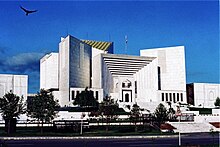

- 정의:파키스탄 사법부는 상급(또는 상위) 사법부와 하위(또는 하위) 사법부라는 두 종류의 법정이 있는 계층적 시스템이다.파키스탄 대법원장은 각급 지휘부에서 사법부의 사법제도를 총괄하는 주심 판사다.상급 사법부는 파키스탄 대법원과 연방 샤리아트 법원, 5개 고등 법원으로 구성되며, 대법원은 정점에 있다.파키스탄 헌법은 상급 사법부에 헌법의 보존, 보호, 방어의 의무를 위임한다.아자드 카슈미르와 길기트 발티스탄의 다른 지역들은 별도의 법원 제도를 가지고 있다.

독립 이후, 파키스탄은 외국과의 관계를 균형 있게 유지하려고 시도해왔다.[171]파키스탄은 중국의 강력한 동맹국이며, 두 나라 모두 극히 밀접하고 지지하는 특수관계의 유지에 상당한 중요성을 두고 있다.[172]또한 2004년 테러와의 전쟁 이후 미국의 주요 비 NATO 동맹국이 되어왔다.[173]파키스탄의 외교정책과 지스트라테이는 주로 국가 정체성과 영토 보전에 대한 위협에 대한 경제와 안보, 그리고 다른 이슬람 국가들과의 긴밀한 관계 함양에 초점을 맞추고 있다.[174]

카슈미르 분쟁은 파키스탄과 인도 사이의 주요 분쟁 지점으로 남아있다; 그들의 네 번의 전쟁 중 세 번은 이 영토를 놓고 싸웠다.[175]파키스탄은 지정학적 경쟁국인 인도와의 관계상의 어려움 때문에 터키, 이란과 긴밀한 정치적 관계를 유지하고 있으며,[176] 두 나라 모두 파키스탄의 외교 정책의 초점이 되어 왔다.[176]사우디 아라비아는 또한 파키스탄의 외교 정책에서 존경받는 위치를 유지하고 있다.

파키스탄은 핵확산금지조약(NPT)에 가입하지 않은 당사국으로 IAEA의 영향력 있는 회원국이다.[177]최근 사건에서 파키스탄은 핵분열 물질을 제한하는 국제협정을 봉쇄하고 "대처가 구체적으로 파키스탄을 겨냥할 것"[178]이라고 주장했다.20세기 파키스탄의 핵 억제 프로그램은 이 지역에서 인도의 핵 야망에 대항하는 데 초점을 맞췄고, 인도의 핵실험은 결국 파키스탄이 핵 강국이 되는 지정학적 균형을 유지하기 위해 보답하도록 이끌었다.[179]현재, 파키스탄은 외국의 침략에 대항하는 중요한 핵 억지력을 말하며 신뢰할 수 있는 최소 억제 정책을 유지하고 있다.[180][181]

세계 주요 해양 석유 공급선과 통신 광섬유의 전략적 지정학적 복도에 위치한 파키스탄은 중앙아시아 국가들의 천연자원에 근접해 있다.[182]파키스탄의 한 상원의원은[clarification needed] 2004년 외교정책 브리핑에서 파키스탄은 국가의 주권적 평등, 양자주의, 상호 이익의 상호관계, 서로의 내정 불간섭 등을 외교정책의 주요 특징으로 부각시키고 있다고 설명한 것으로 알려졌다.[183]파키스탄은 유엔의 적극적인 회원국으로 국제정치에서 파키스탄의 입장을 대변할 상임대표를 두고 있다.[184]파키스탄은 이슬람 세계에서 "중용을 강화했다"는 개념을 위해 로비를 해왔다.[185]파키스탄은 또한 영연방,[186] 남아시아 지역협력협회(SAARC), 경제협력기구(ECO),[187] G20 개발도상국들의 회원국이기도 하다.[188]

이념적 차이 때문에 파키스탄은 1950년대에 소련을 반대했다.1980년대 소련-아프간 전쟁 당시 파키스탄은 미국의 가장 가까운 동맹국 중 하나였다.[183][189]파키스탄과 러시아의 관계는 1999년 이후 크게 개선되었고, 각 분야의 협력도 증가했다.[190]파키스탄은 미국과 '온앤오프' 관계를 맺고 있다.냉전 기간 중 미국의 가까운 우방이었던 파키스탄과 미국과의 관계는 1990년대에 파키스탄의 비밀 핵 개발로 인해 제재를 가했을 때 악화되었다.[191]파키스탄은 9.11 테러 이후 미국이 파키스탄을 원조 자금과 무기로 지원하는 등 중동과 남아시아 지역의 대테러 문제를 놓고 미국의 긴밀한 동맹국이었다.[192][193]당초 미국이 주도한 테러와의 전쟁은 관계 개선을 이끌었지만 아프가니스탄 전쟁 중 이해관계가 엇갈리고 그에 따른 불신이 심화되고 테러 관련 이슈로 인해 경색됐다.[194]파키스탄 정보기관인 ISI는 아프가니스탄에서 탈레반 저항세력을 지원한 혐의를 받고 있다.[195][196][197]

파키스탄은 이스라엘과 외교 관계를 맺고 있지 않다.[198] 그럼에도 불구하고, 일부 이스라엘 시민들은 관광 비자로 파키스탄을 방문했다.[199]하지만 터키를 소통의 통로로 삼아 양국 간 교류가 이뤄졌다.[200]세계에서 유일하게 아르메니아와 외교관계를 수립하지 않은 나라임에도 불구하고 파키스탄에는 여전히 아르메니아계가 거주하고 있다.[201]파키스탄은 방글라데시와의 관계에서 초기에는 긴장 상태였지만 따뜻한 관계를 유지했다.

중국과의 관계

파키스탄은 중화인민공화국과 공식 외교관계를 수립한 최초의 국가 중 하나였으며, 1962년 중국이 인도와 전쟁을 벌인 이후부터 관계가 계속 튼튼해져 특별한 관계를 형성하고 있다.[203]1960년대부터 1980년대까지 파키스탄은 중국이 세계 주요국에 진출하는 데 큰 도움을 주었으며 리처드 닉슨 미국 대통령의 중국 국빈방문을 용이하게 하는 데 일조했다.[203]파키스탄의 정부 교체와 지역 및 세계 정세의 변동에도 불구하고 중국의 파키스탄 정책은 항상 지배적인 요인으로 작용하고 있다.[203]그 대가로 중국은 파키스탄의 최대 교역국이며, 과다르의 파키스탄 심해항 등 파키스탄 인프라 확장에 대한 중국인들의 실질적인 투자가 이루어지는 등 경제협력이 번창했다.중-파키스탄 우호관계는 2015년 양국이 분야별 협력을 위한 51개 협정과 양해각서(MoUs)를 체결하면서 새로운 정점에 도달했다.[204]양국은 2000년대 자유무역협정(FTA)을 체결했고 파키스탄은 이슬람 세계에 중국의 소통 가교 역할을 계속하고 있다.[205]중국은 2016년 파키스탄, 아프가니스탄, 타지키스탄과 대테러 동맹을 맺겠다고 발표했다.[206]2018년 12월 파키스탄 정부는 100만 위구르 무슬림들을 위한 중국의 재교육 캠프를 옹호했다.[207][208]

무슬림 세계와의 관계 강조

독립 이후 파키스탄은 다른 이슬람 국가들과의[209] 양자 관계를 활발히 추구하면서 이슬람 세계의 지도력, 혹은 적어도 통일을 이루기 위한 노력의 리더십을 위해 적극적인 노력을 기울였다.[210]알리 형제는 파키스탄을 이슬람 세계의 자연적 지도자로 내세우려고 노력했는데, 이는 부분적으로 파키스탄의 막대한 인력과 군사력 때문이다.[211]이슬람 연맹의 최고 지도자인 칼리크자만은 파키스탄이 모든 이슬람 국가들을 회교로 불러들일 것이라고 선언했다.[212]

(파키스탄의 탄생과 함께) 그러한 발전은 미국의 승인을 얻지 못했고, 당시 영국의 클레멘트 애틀리 총리는 인도와 파키스탄이 다시 연합하기를 바란다고 말하면서 국제적인 의견을 표명했다.[213]당시 아랍권 대부분이 민족주의적인 각성을 겪고 있었기 때문에 파키스탄의 범이슬람적 열망에는 거의 끌리지 않았다.[214]아랍 국가들 중 일부는 '이슬람국가' 프로젝트를 다른 이슬람 국가들을 지배하려는 파키스탄의 시도로 보았다.[215]

파키스탄은 전 세계 이슬람교도들의 자기결정권을 강력하게 옹호했다.인도네시아, 알제리, 튀니지, 모로코, 에리트레아의 독립운동을 위한 파키스탄의 노력은 의미심장했고, 초기에는 이들 국가와 파키스탄의 긴밀한 유대관계로 이어졌다.[216]그러나, 파키스탄은 또한 아프가니스탄 내전 중 잘랄라바드에 대한 공격을 주도하여 그곳에 이슬람 정부를 수립했다.파키스탄은 파키스탄, 아프가니스탄, 중앙아시아를 아우르며 국경을 초월한 '이슬람 혁명'을 조성하기를 바랬다.[217]

반면 파키스탄과 이란 관계는 종파간 긴장 때문에 때로는 경색되기도 했다.[218]이란과 사우디는 파키스탄을 대리 종파전쟁의 전장으로 삼았고, 1990년대까지 수니파 탈레반 조직에 대한 파키스탄의 지원이 탈레반이 지배하는 아프가니스탄에 반대하는 시아 이란에게 문제가 됐다.[219]1998년 파키스탄 전투기가 탈레반을 지원하기 위해 아프가니스탄의 마지막 시아파 거점을 폭격하자 이란이 파키스탄을 전쟁 범죄로 비난하면서 이란과 파키스탄 사이의 긴장이 고조되었다.[220]

파키스탄은 이슬람 협력 기구(OIC)의 영향력 있고 창설된 회원이다.아랍 세계 및 이슬람 세계의 다른 나라들과 문화적, 정치적, 사회적, 경제적 관계를 유지하는 것은 파키스탄의 외교 정책에서 중요한 요소다.[221]

행정 구역

| 행정 구역 | 자본 | 인구 |

|---|---|---|

| 퀘타 | 12,344,408 | |

| 라호르 | 110,126,285 | |

| 카라치 | 47,886,051 | |

| 페샤와르 | 40,525,047 | |

| 길깃 | 1,800,000 | |

| 무자파라바드 | 4,567,982 | |

| 이슬라마바드 수도 준주 | 이슬라마바드 | 2,851,868 |

연방 의회 공화국 국가인 파키스탄은 네 개의 주로 구성된 연방이다.펀자브, 카이버 파크툰화, 신드, 발로치스탄,[222] 그리고 세 구역:이슬라마바드 수도 영토, 길깃발티스탄, 아자드 카슈미르.파키스탄 정부는 국경 지역과 카슈미르 지역의 서부 지역에 대한 사실상의 관할권을 행사하는데, 이 관할권은 별도의 정치 단체인 아자드 카슈미르와 길기트 발티스탄(구 북방 지역)으로 조직된다.2009년 헌법상 부여(길기트-발티스탄 권한 부여 및 자치령)는 길기트발티스탄에 준우승적 지위를 부여해 자치권을 부여했다.[223]

지방정부제도는 지역구와 테실, 조합의회의 3단계 체제로 구성되며, 각 계층에 선출된 기구가 있다.[224]모두 130여 개의 구역이 있는데, 이 중 아자드 카슈미르에는 10개[225], 길깃발티스탄에는 7개가 있다.[226]

법집행은 관련 도나 영토에 한정된 관할권을 가진 정보사회의 공동네트워크에 의해 이루어진다.국가정보국(National Intelligence Directorate)은 정보 정보를 연방 및 지방 수준으로 조정하며, 연방 및 IB, 고속도로 경찰, 파키스탄 레인저스와 프론티어 군단 같은 준군사력을 포함한다.[227]

파키스탄의 '프리미어' 정보기관인 ISI(Inter-Services Intelligence, ISI)는 1947년 파키스탄 독립 직후 1년 만에 결성됐다.[228]2014년 ABC 뉴스포인트는 ISI가 세계[229] 최고 정보기관으로 꼽혔고, 지에뉴스는 ISI를 세계 최고 권력 정보기관 중 5위로 보도했다.[230]

법원 제도는 위계질서로 조직되는데, 그 정점에 대법원이 있고, 그 아래로는 고등법원, 연방샤리아트법원(각 도에 1개, 연방 수도에 1개), 지방법원(각 구역에 1개), 사법행정법원(각 읍·면·면·면·면·면·면·면·면·면·면·민법원이 있다.형법규정은 법이 주로 부족의 관습으로부터 파생되는 부족 지역의 관할권을 제한한다.[227][231]

카슈미르 분쟁

인도 아대륙의 최북단에 위치한 히말라야 지역인 카슈미르는 1947년 8월 인도 분할 이전 영국 라즈에서 잠무와 카슈미르로 알려진 자치왕자적 국가로 통치되었다.인도와 파키스탄이 분단 후 독립한 이후, 이 지역은 양국 관계를 방해하는 주요 영토 분쟁의 대상이 되었다.두 주는 1947–1948년과 1965년에 이 지역을 둘러싼 두 개의 대규모 전쟁에 서로 참여해왔다.인도와 파키스탄은 또한 1984년과 1999년에 이 지역을 둘러싼 소규모의 장기간의 분쟁과 싸웠다.[175]카슈미르 지역의 약 45.1%는 인도(행정적으로 잠무·카슈미르·라다흐로 갈라짐)에 의해 지배되고 있는데, 이 역시 그 지배하에 있지 않은 이전의 왕족 국가 잠무·카슈미르 전체의 영토를 주장하고 있다.[175]잠무와 카슈미르, 라다크에 대한 인도의 지배와 나머지 지역에 대한 그들의 주장 또한 파키스탄에 의해 경쟁되어 왔는데 파키스탄은 이 지역의 약 38.2%를 (행정적으로 아자드 잠무와 카슈미르와 길깃 발티스탄으로 분할) 그리고 인도의 지배하에 있는 모든 영토를 주장하고 있다.[175][232]또한 1962년 중-인도 전쟁과 1963년 중-파키스탄 협정 이후 이 지역의 약 20%가 중국(Aksai Chin and Shaksgam Valley)[233]에 의해 통제되어 왔다.중국이 지배하는 카슈미르 지역은 여전히 인도 영토 주장의 대상이지만 파키스탄이 영유권을 주장하지는 않는다.

인도는 카슈미르 지역 전체를 새로 독립한 인도에 양도하기로 합의한 자무와 카슈미르 주의 왕족 국가와의 법적 합의인 '접속 기구'에 근거하여 카슈미르 지역 전체를 주장하고 있다.[234]파키스탄은 카슈미르 대부분의 지역을 무슬림이 다수인 인구와 지리적 근거로 주장하는데, 이는 두 독립국가의 창설에 적용된 원칙과 동일하다.[235]인도는 1948년 1월 1일 이 분쟁을 유엔에 회부했다.[236]1948년에 통과된 결의안에서, 유엔 총회는 국민투표의 개최 조건을 정하기 위해 파키스탄에 대부분의 군 병력을 철수시킬 것을 요청했다.그러나 파키스탄은 이 지역을 비우지 못했고 1949년 카슈미르를 사실상 국경으로 분단시킨 통제선(LoC)으로 알려진 휴전선을 구축했다.[237]카슈미르에 거주하는 이슬람교도들이 인도에서 탈퇴하기 위해 투표할 것을 우려한 인도는 이 지역에서 국민투표가 실시되는 것을 허용하지 않았다.이는 크리슈나 메논 인도 국방장관의 성명에서 "카슈미르는 파키스탄에 합류하기 위해 투표할 것이며 국민투표에 동의한 책임이 있는 인도 정부는 살아남지 못할 것"[238]이라고 밝혔다.

파키스탄은 유엔이 위임한 대로 공정한 선거를 통해 카슈미르 국민이 자신의 미래를 결정할 수 있는 권리를 주장하는 반면, 인도는 1972년 심라 협약과 지방 선거가 정기적으로 치러지는 점을 언급하며 카슈미르는 인도의 '통합적 부분'이라고 명시해 왔다.[239][240]최근의 전개에서, 일부 카슈미르 독립 단체들은 카슈미르가 인도와 파키스탄 둘 다로부터 독립되어야 한다고 믿는다.[175]

법 집행

파키스탄의 법 집행은 몇몇 연방 및 지방 경찰 기관의 합동 네트워크에 의해 수행된다.4개 주와 이슬라마바드 수도 영토(ICT)는 각각 관할 구역이 해당 지방이나 영토로만 확장된 민간 경찰력을 보유하고 있다.[146]연방 차원에는 연방수사국(FIA), 정보국(IB) 등 전국적인 관할권을 가진 민간 정보기관이 다수 존재하며, 국가방위군(북방지역), 레인저스군(펀자브·신드), 프론티어군단(키버 파크툰화아) 등 여러 준군사조직이 있다.발로치스탄).

모든 민간 경찰 병력 중 가장 많은 고위 장교들도 파키스탄의 공무원 업무의 구성요소인 경찰청의 일부를 구성한다.즉, 펀자브 경찰, 신드 경찰, 카이버-팍툰크화 경찰, 발로치스탄 경찰 등 4개의 지방 경찰이 있으며, 모두 선임 경감-제너럴스가 지휘하고 있다.정보통신기술(ICT)은 수도의 법과 질서를 유지하기 위해 자체적인 경찰 요소인 캐피털 폴리스(Capital Police)를 가지고 있다.CID부서는 범죄수사대로 각 지방경찰서에서 중요한 역할을 하고 있다.

파키스탄의 사법당국은 또한 교통과 안전법의 집행, 파키스탄의 지방간 고속도로망에 대한 보안과 복구를 담당하는 고속도로 순찰대를 가지고 있다.각 지방 경찰청은 또한 VIP 호위뿐만 아니라 대테러 경찰 부대인 NACTA가 이끄는 각각의 엘리트 경찰 부대를 유지하고 있다.펀자브와 신드에서는 파키스탄 레인저스가 경찰 지원을 포함한 법과 질서를 유지하는 것뿐만 아니라 전쟁지역과 분쟁지역에서의 보안을 제공하고 유지하는 것을 주요 목표로 하는 내부 보안군이다.[241]프런티어 군단은 카이버-팍툰크화(Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa)와 발로치스탄(Balochistan)에서도 비슷한 목적을 수행하고 있다.[241]

남성 동성애는 파키스탄에서 불법이며 종신형까지 처벌받을 수 있다.[242]국경없는기자회는 2018년 언론자유지수에서 언론자유를 기준으로 180개국 중 파키스탄을 139위로 꼽았다.[243]텔레비전 방송국과 신문은 정부나 군에 비판적인 보도를 게재하기 위해 일상적으로 폐쇄된다.[244]

파키스탄의 군대는 2021년 잠정 집계 기준 약 65만1800명, 준군사력 29만1000명으로 상근 복무 인원 기준으로 세계에서 6번째로 규모가 크다.[245]그것들은 1947년 독립 이후 존재하게 되었고, 그 이후 군사정치는 자주 국가정치에 영향을 끼쳤다.[170]군 지휘 체계는 합참의 통제를 받으며, 모든 지부 합동 업무, 조정, 군 물류, 합동 임무는 합동참모본부 산하다.[246]합동참모본부 HQ는 라왈핀디 군구 인근에 에어 HQ, 네이비 HQ, 육군 GHQ로 구성되어 있다.[247]

합참의장은 군 최고 원칙 참모로, 3개 군부에 대한 권한은 없지만 민간 정부의 최고 군사보좌관이다.[246]합참의장은 JSHQ로부터 군을 통제하고 군과 민간 정부 간의 전략적 소통을 유지하고 있다.[246]2021년[update] 현재 CJCSC는 콰마르 자베드 바좌 육군참모총장,[249] 무함마드 암자드 칸 니아지 해군참모총장,[250] 자헤어 아흐마드 바바르 공군참모총장 등과 함께 나뎀 라자[248] 장군이 맡고 있다.[251]주요 지부는 육군, 공군, 해군이 있으며, 국내에는 다수의 준군사조직이 지원하고 있다.[252]전략 비소, 배치, 고용, 개발, 군사용 컴퓨터, 지휘통제 등에 대한 통제는 신뢰할 수 있는 최소한의 억제책의 일환으로 원자력 정책에 관한 업무를 총괄한 국가 지휘권한에 따라 부여된 책임이다.[105]

미국, 터키, 중국은 긴밀한 군사 관계를 유지하고 있으며 정기적으로 파키스탄에 군사 장비와 기술이전을 수출하고 있다.[253]합동 물류와 주요 전쟁 게임은 때때로 중국과 터키의 군대에 의해 수행된다.[252][254]병역기피에 대한 철학적 근거는 유사시 헌법에 의해 도입되지만, 강제된 적은 없다.[255]

1947년 이래로 파키스탄은 네 번의 재래식 전쟁에 참여해왔다.첫 번째는 파키스탄이 서부 카슈미르, (아자드 카슈미르와 길깃 발티스탄), 인도 동부 카슈미르(잠무와 카슈미르와 라다크)를 장악하면서 카슈미르에서 발생했다.영토 문제는 결국 1965년에 또 하나의 재래식 전쟁을 초래했다.벵골 난민 문제는 1971년 또 다른 전쟁으로 이어졌고, 이로 인해 파키스탄은 동파키스탄에서 무조건 항복을 하게 되었다.[256]카르길의 긴장은 두 나라를 전쟁 직전으로 몰고 갔다.[106]1947년 이후 해결되지 않은 아프가니스탄과의 영토 문제는 대부분 산악 국경에서 유지되었던 국경 분쟁을 보았다.1961년, 군과 정보계는 두란드 라인 국경 근처의 바자우르 기관에서 아프간 침공을 격퇴했다.[257]

주로 ISI인 파키스탄 정보당국은 이웃 소련과의 관계에서 긴장이 고조되면서 소련이 아프가니스탄에 주둔하는 것에 맞서 아프간 무자히딘과 외국 전투기에 대한 미국의 자원을 조직적으로 조정했다.군사 보고에 따르면 PAF는 소련의 공군과 교전 중이었으며, 그 중 하나는 알렉산더 럿스코이의 것이었다.[258]파키스탄은 자체적인 갈등과는 별개로 유엔 평화유지 임무에 적극 참여해 왔다.1993년 고딕 독사 작전에서 소말리아 모가디슈에서 갇힌 미군 병사들을 구출하는 데 큰 역할을 했다.[259][260]유엔 보고서에 따르면 파키스탄군은 에티오피아와 인도에 이어 세 번째로 많은 병력을 유엔 평화유지 임무에 투입했다.[261]

파키스탄은 일부 아랍 국가에 군대를 배치하여 방어, 훈련, 자문 역할을 수행하고 있다.[262]PAF와 해군의 전투기 조종사들은 6일 전쟁(1967년)과 욤 키푸르 전쟁(1973년)에서 이스라엘에 대항하는 아랍 국가들의 군대에서 자발적으로 복무했다.파키스탄의 전투기 조종사들은 6일 전쟁에서 이스라엘 전투기 10대를 격추시켰다.[259]1973년 전쟁 때, PAF 조종사 중 한 명인 Flt. 중령.사타르 알비(MiG-21)는 이스라엘 공군 미라지를 격추하고 시리아 정부로부터 영예를 안았다.[263]1979년 사우디 왕정이 요청한 파키스탄의 특수부대, 공작원, 특공대 등은 메카에 있는 사우디군이 그랜드 모스크의 운영을 주도할 수 있도록 돕기 위해 급히 투입됐다.거의 2주 동안 사우디 특수부대와 파키스탄 특공대는 그랜드 모스크의 경내를 점령한 반란군과 싸웠다.[264]1991년 파키스탄은 걸프전에 개입하여 미국이 주도하는 연합군의 일환으로 5,000명의 병력을 파견했는데, 특히 사우디의 방어를 위해서였다.[265]

보스니아에 대한 유엔 무기 금수조치에도 불구하고 ISI의 자베드 나시르 장군은 보스니아 무자헤딘에 대전차 무기와 미사일을 공수해 대세를 보스니아 이슬람교도들에게 유리하게 바꾸고 세르비아인들에게 포위를 풀도록 강요했다.나시르의 지도하에 ISI는 신장성의 중국 이슬람교도, 필리핀의 반군 이슬람 단체, 중앙아시아의 일부 종교 단체 지원에도 관여했다.[266]

2004년 이후 군은 카이버 파크툰화 지방에서 주로 테흐리크-아이-탈리반 파벌에 대항하여 반란을 일으켰다.[267]육군이 수행하는 주요 작전으로는 흑선풍 작전, 라흐-에-니자트 작전, 자르브-에-아즈브 작전 등이 있다.[268]

SIPRI에 따르면 파키스탄은 2012~2016년 사이에 9번째로 많은 무기를 수입했다.[269]

이코노미

이 섹션은 갱신되어야 한다. 사용 하도록 이 2020년 4월). |

| 경제지표 | ||

|---|---|---|

| GDP(PPP) | 1조 2,540억 달러(2019년) | [9] |

| GDP(명목) | 2842억 달러(2019년) | [270] |

| 실질 GDP 성장 | 3.29% (2019) | [271] |

| CPI 인플레이션 | 10.3% (2019) | [272] |

| 실업 | 5.7% (2018) | [273] |

| 노동력 참여율 | 48.9% (2018) | [274] |

| 총공채 | 1070억 달러(2019년) | |

| 국부 | 4650억 달러(2019년) | [275] |

파키스탄 경제는 구매력평가(PPP) 기준 세계 23위, 명목 국내총생산(GDP) 기준 42위다.경제학자들은 파키스탄이 첫 천년 CE 기간 동안 세계에서 가장 부유한 지역 중 하나였으며, GDP 기준으로 가장 큰 경제를 가지고 있다고 추정한다.이러한 이점은 18세기에 중국과 서유럽과 같은 다른 지역들이 조금씩 발전하면서 없어졌다.[276]파키스탄은 개발도상국으로 여겨지며[277] 브릭스(BRICs)[278]와 함께 21세기 세계 최대 경제대국이 될 잠재력이 높은 11개국의 그룹인 넥스트 일레븐의 하나이다.수십 년간의 사회 불안정을 겪은 후, 2013년[update] 현재, 철도 교통과 전기 에너지 발전 같은 기본 서비스에서의 대범한 노령화와 불균형한 거시 경제학의 심각한 결핍이 발전하고 있다.[279]경제는 인더스강을 따라 성장중심이 있는 반산업화된 것으로 평가된다.[280][281][282]카라치와 펀자브의 도시 중심지의 다각화된 경제는 특히 발로치스탄의 다른 지역의 개발이 덜 된 지역과 공존하고 있다.[281]경제 복잡도 지수에 따르면 파키스탄은 세계 67위의 수출 경제 대국이며 106위의 복합 경제다.[283]2015~16년 회계연도 동안 파키스탄의 수출은 208억1000만 달러, 수입은 447억6000만 달러로 무역수지가 239억6000만 달러의 마이너스를 기록했다.[284]

2019년[update] 현재 파키스탄의 명목 GDP 추정치는 2842억 달러다.PPP에 의한 GDP는 1조 2,540억 달러다.1인당 추정 명목 GDP는 1388달러, GDP(PPP)/Capita는 6,016달러(국제 달러)이며,[9] 세계은행에 따르면 파키스탄은 중요한 전략적 기부금과 개발 잠재력을 가지고 있다.파키스탄 젊은이들의 증가하는 비율은 파키스탄에 잠재적인 인구통계학적 배당금과 적절한 서비스와 고용을 제공하기 위한 도전을 제공한다.[285] 인구의 21.04%는 하루에 1.25달러라는 국제 빈곤선 아래 살고 있다.15세 이상 인구의 실업률은 5.5%[286]이다.파키스탄에는 약 4천만 명의 중산층 시민이 있으며 2050년에는 1억 명으로 증가할 것으로 예상된다.[287]세계은행이 발간한 2015년 보고서는 파키스탄 경제를 구매력 기준으로 세계 24위[288], 절대적으로 41위로[289] 평가했다.남아시아에서 두 번째로 큰 경제대국으로, 지역 GDP의 약 15.0%를 대표한다.[290]

| 회계 연도 | GDP 성장[291] | 인플레이션율[292] |

|---|---|---|

| 2013–14 | ||

| 2014–15 | ||

| 2015–16 | ||

| 2016–17 | ||

| 2017–18 |

파키스탄의 경제 성장은 창시 이래 다양했다.지속가능하고 공평한 성장을 위한 토대가 형성되지는 않았지만 민주적 전환기에는 느렸지만 계엄 3기에는 견실했다.[87]2000년대 초반에서 중반까지는 급속한 경제개혁의 시기였다. 정부는 개발비 지출을 증가시켰고, 이것은 빈곤 수준을 10% 감소시켰고, GDP는 3%[146][293] 증가시켰다.경제는 2007년부터 다시 냉각되었다.[146]인플레이션은 2008년 25.0%에 달했고 파키스탄은 파산을 피하기 위해 국제통화기금의 지원을 받는 재정정책에 의존해야 했다.[294][295]1년 뒤 아시아개발은행은 파키스탄의 경제위기가 완화되고 있다고 보고했다.[296]2010-11 회계연도의 물가상승률은 14.1%[297]이다.2013년 이후 국제통화기금(IMF) 프로그램의 일환으로 파키스탄의 경제성장이 회복됐다.2014년 골드만삭스는 파키스탄 경제가 향후 35년간 15배 성장해 2050년까지 세계 18위의 경제대국이 될 것으로 전망했다.[298]루치르 샤르마는 2016년 저서 '국가의 흥망성쇠'에서 파키스탄 경제를 '이륙' 단계라고 표현했고 2020년까지의 미래 전망은 '매우 좋다'라고 표현했다.샤르마 대통령은 파키스탄을 "앞으로 5년 동안 저소득 국가에서 중간소득 국가로 전환하는 것이 가능하다"고 말했다.[299]

| 세계 GDP 점유율(PPP)[300] | |

|---|---|

| 연도 | 공유 |

| 1980 | 0.54% |

| 1990 | 0.72% |

| 2000 | 0.74% |

| 2010 | 0.79% |

| 2017 | 0.83% |

파키스탄은 천연물자재 생산국 중 가장 큰 나라 중 하나이며, 노동시장은 세계에서 10번째로 크다.700만 명의 파키스탄인 디아스포라는 2015-16년 미국 경제에 19억 달러를 기부했다.[301][302][303]파키스탄으로의 송금의 주요 원천 국가는 UAE, 미국, 사우디아라비아, 걸프 지역(바흐레인, 쿠웨이트, 카타르, 오만)이다.호주, 캐나다, 일본, 영국, 노르웨이, 스위스.[304][305]세계무역기구에 따르면, 파키스탄의 전체 세계 수출에서 차지하는 비중은 감소하고 있으며, 2007년에는 0.13%에 그쳤다.[306]

농업 및 1차 부문

파키스탄 경제의 구조는 주로 농업에서 강력한 서비스 기지로 바뀌었다.2015년[update] 기준 농업은 국내총생산(GDP)의 20.9%에 불과하다.[308]그러나 유엔식량농업기구에 따르면 파키스탄은 2005년 2159만1400t의 밀을 생산해 아프리카 전체(2030만4585t)보다 많고 남아메리카 전체(245만7884t)에 버금간다.[309]인구의 대다수는 직간접적으로 이 분야에 의존하고 있다.고용 노동력의 43.5%를 차지하며 외화벌이의 최대 원천이다.[308][310]

우리나라 제조업 수출의 상당 부분은 농업 부문의 일부인 면화, 가죽과 같은 원재료에 의존하고 있는 반면, 농산물의 공급 부족과 시장 붕괴는 인플레이션 압력을 증가시킨다.이 나라는 또한 면화 생산량 5위인데, 1950년대 초 170만 베일의 작은 시작부터 1400만 베일의 면화 생산량이며, 사탕수수를 자급자족하고 있으며, 우유 세계 4위 생산국이다.토지와 수자원은 비례적으로 증가하지 않았지만, 노동력과 농업 생산성의 증가가 주된 원인이었다.농작물 생산의 주요 돌파구는 1960년대 후반과 1970년대에 토지 및 밀과 쌀의 생산량 증가에 크게 기여한 녹색 혁명은 밀과 쌀의 생산량을 증가시켰다.사설 관정은 트랙터 재배로 인해 자르기 강도가 50% 증가하였다.관정은 작물 수확량을 50%까지 끌어올린 반면 밀과 쌀의 고수익 품종(HYV)은 50~60%의 수확량을 기록했다.[311]육류산업은 전체 GDP의 1.4%를 차지한다.[312]

산업

산업은 국내총생산(GDP)의 19.74%, 전체 고용의 24%를 차지하는 경제 2위 분야다.국내총생산(GDP)의 12.2%인 대규모 제조업(LSM)이 전체 부문을 장악해 부문별 점유율 66%를 차지하고 있고, 이어 전체 GDP의 4.9%를 차지하는 소규모 제조업이 그 뒤를 잇고 있다.파키스탄의 시멘트 산업 역시 아프가니스탄과 국내 부동산 부문의 수요로 인해 빠르게 성장하고 있다.2013년 파키스탄은 7,708,557톤의 시멘트를 수출했다.[314]파키스탄은 44,768,250 미터톤의 시멘트와 42,636,428 미터톤의 클링커를 설치하였다.2012년과 2013년 파키스탄의 시멘트 산업은 경제에서 가장 수익성이 높은 분야가 되었다.[315]

섬유산업은 파키스탄의 제조업 분야에서 중추적인 위치를 차지하고 있다.아시아에서 파키스탄은 섬유제품 수출 8위로 국내총생산(GDP)에 9.5%를 기여하고 약 1500만명(인력 4900만명 중 약 30%)에게 고용을 제공한다.파키스탄은 중국, 인도에 이어 아시아에서 세 번째로 방적용량이 많은 면화 생산국으로 세계 방적용량에 5%의 기여를 하고 있다.[316]중국은 지난 회계연도 15억 2700만 달러의 직물을 수입해 파키스탄 섬유업계 두 번째로 큰 수입국이다.부가가치가 높은 직물을 주로 수입하는 미국과 달리 중국은 파키스탄에서 면사포와 면직물만 구입한다.2012년 파키스탄 섬유제품은 영국 전체 섬유 수입의 3.3% 또는 10억 7천만 달러, 중국 전체 섬유 수입의 12.4% 또는 46억 1천만 달러, 미국 전체 섬유 수입의 3.0%(2억 8천만 달러), 독일 전체 섬유 수입의 1.6%(8억 8천만 달러), 인도 전체 섬유 수입의 0.7%를 차지했다.[317]

서비스

서비스업은 국내총생산(GDP[308])의 58.8%를 차지하며 경제성장의 주요 동력으로 부상했다.[318]다른 개발도상국들과 마찬가지로 파키스탄 사회는 소비 지향적인 사회로, 한계 소비 성향이 높다.서비스업 증가율이 농업과 산업부문 증가율보다 높은 것으로 나타났다.서비스업은 2014년 GDP의 54%를 차지하며 전체 고용의 3분의 1을 약간 넘는다.서비스 부문은 다른 경제 부문과 강한 연계를 가지고 있다; 그것은 농업 부문과 제조업 부문에 필수적인 투입물을 제공한다.[319]파키스탄의 I.T 섹터는 파키스탄에서 가장 빠르게 성장하는 섹터 중 하나로 여겨진다.세계경제포럼(WEF)은 파키스탄을 '네트워크 준비도 지수 2016'에서 139개국 중 110위로 꼽았다.[320]

파키스탄은 2020년[update] 5월 현재 약 8200만 명의 인터넷 이용자를 보유하고 있어 세계에서 9번째로 많은 인터넷 이용자를 보유하고 있다.[321][322]현재의 성장률과 고용 추세로 볼 때 2020년까지 파키스탄의 정보통신기술(ICT) 산업이 100억 달러를 넘어설 것으로 보인다.[323]그 부문은 12,000명이고, 5대 프리랜서 국가 중 하나이다.[324]한국은 또한 2005-06년 8.2pc에서 2012-13년 12.6pc로 수출 비중이 급증함에 따라 통신, 컴퓨터, 정보 서비스 분야의 수출 실적도 개선되었다.같은 기간 서비스 수출 비중이 각각 3pc와 7.7pc였던 중국보다 훨씬 좋은 성장이다.[325]

관광업

문화와 사람, 풍경이 다양한 파키스탄은 2018년 약 660만 명의 외국인 관광객을 유치했는데,[326] 이는 히피 트레일로 인해 유례없는 외국인 관광객 수를 받았던 1970년대 이후 큰 감소세를 보였다.이 산책로에는 1960년대와 1970년대 수천 명의 유럽과 미국인들이 참여했으며 이들은 터키와 이란을 거쳐 파키스탄을 거쳐 인도로 유입됐다.[327]이들 관광객이 가장 많이 찾는 곳은 카이버 고개, 페샤와르, 카라치, 라호르, 스와트, 라왈핀디였다.[328]이란 혁명과 소련-아프간 전쟁 이후 그 뒤를 이은 숫자는 감소했다.[329]

파키스탄의 관광 명소는 남쪽의 맹그로브에서부터 북동쪽의 히말라야 언덕 역까지 다양하다.이 나라의 관광지는 불교 유적지인 탁트이바히와 타실라에서부터 모헨조다로, 하라파 같은 인더스 계곡 문명 5천년 된 도시까지 다양하다.[330]파키스탄에는 7,000미터가 넘는 산봉우리들이 있다.[331]파키스탄 북부는 고대 건축의 예인 많은 오래된 요새와 알렉산더 대왕의 후손이라고 주장하는 이슬람 이전의 작은 칼라샤 공동체의 본거지인 훈자와 치트랄 계곡이 있다.[332]파키스탄의 문화 수도 라호르에는 바드샤히 마스지드, 샬리마르 정원, 자한기르 무덤, 라호르 요새 등 무굴 건축의 예가 많이 들어 있다.

2005년 카슈미르 대지진이 발생한 지 꼭 1년 만인 2006년 10월 가디언은 파키스탄의 관광산업을 돕기 위해 '파키스탄의 5대 관광지'라고 표현한 것을 공개했다.[333]5개소에는 택일라, 라호르, 카라코람 고속도로, 카리마바드, 사이얼 뮬루크 호수 등이 포함됐다.파키스탄의 독특한 문화 유산을 홍보하기 위해, 정부는 1년 내내 다양한 축제를 개최한다.[334]2015년 세계경제포럼 여행관광경쟁력 보고서는 파키스탄을 141개국 중 125개국으로 꼽았다.[335]

사회 기반 시설

파키스탄은 2016년 IWF 및 세계은행 연차총회에서 남아시아의 인프라 개발을 위한 최적의 국가로 인정받았다.[336]

원자력 및 에너지

2021년 5월 현재, 원자력 발전은 6개의 허가된 상업용 원자력 발전소에서 제공하고 있다.[337]파키스탄 원자력위원회(PAEC)는 이들 발전소의 운영만을 책임지고 있으며, 파키스탄 원자력 규제 당국은 원자력 에너지의 안전한 사용을 규제하고 있다.[338]상업용 원자력 발전소에서 발생하는 전기는 파키스탄 전기 에너지의 약 5.8%를 차지하는데 비해 화석 연료(기름과 천연 가스)에서 64.2%, 수력 발전에서 29.9%, 석탄에서 0.1%를 차지한다.[339][340]파키스탄은 핵확산금지조약(NPT) 당사국은 아니지만 국제원자력기구(IAEA)의 입지가 좋은 회원국이다.[341]

칸두형 원자로인 카누프-I는 1971년 캐나다가 공급한 최초의 상업용 원전이다.중-파키스탄 핵협력은 1980년대 초반부터 시작됐다.중국은 1986년 중-파키스탄 원자력협정이 체결된 후 파키스탄에 에너지와 국가의 산업 성장을 위해 CHASNUP-I라는 원자로를 제공했다.[342]2005년에 양국은 2030년까지 발전 용량을 16만 MWe 이상으로 크게 늘릴 것을 요구하며 공동 에너지 보안 계획을 수립할 것을 제안했다.파키스탄 정부는 핵에너지 비전 2050에 따라 2030년까지 원자력 발전 용량을 4만 MWe,[343] 8,900 MWe로 늘릴 계획이다.[344]

2008년 6월, 차슈마-III와 차슈마–을 설치·운영하는 지상공사로 원자력 상업단지가 확장되었다.펀자브 주 차슈마에 있는 IV 원자로는 각각 325–340 MWe이고 비용은 1,290억 원이며, 이로부터 800억 원은 주로 중국, 국제원조에서 나왔다.2008년 10월 이 프로젝트에 대한 중국의 도움을 위한 추가 협정이 체결되었고, 얼마 지나지 않아 그 전에 있었던 미-인도 협정에 대한 대응책으로 부각되었다.그때 견적된 비용은 17억 달러였고, 외채 구성요소는 10억 7천만 달러였다.파키스탄은 2013년 차슈마 원전과 비슷한 추가 원자로 계획을 세워 카라치에 제2 상업용 핵단지를 조성했다.[346]전기 에너지는 다양한 에너지 법인이 발생하며, 4개 도에 걸쳐 국가전력 규제 당국(NEPRA)이 고르게 분배한다.그러나 카라치에 본사를 둔 K-전기 및 수력 발전국(WAPDA)은 파키스탄에서 사용되는 전기 에너지의 상당 부분을 전국적으로 수입하는 것 외에 생산하고 있다.[347]2014년 파키스탄은 약 2만2,797MWt의 전력생산설비를 갖추고 있었다.[339]

운송

운송업은 우리나라 GDP의 10.5%를 차지한다.[348]

고속도로

파키스탄의 고속도로는 파키스탄의 여러 차선, 고속, 통제된 접속 고속도로의 네트워크로, 파키스탄의 국가 도로 당국이 연방 소유, 유지, 운영한다.2020년 2월 20일 현재 1882km의 고속도로가 운행 중이며, 1854km가 추가로 건설 중이거나 계획 중이다.파키스탄의 모든 고속도로는 문자 'M'("모터웨이"의 경우)으로 사전 고정되어 있고, 그 뒤에 특정 고속도로(중간에 하이픈이 있는 경우)라는 고유 숫자 명칭이 붙는다(예: "M-1"[349]

파키스탄의 자동차 전용도로는 파키스탄의 '국가 무역 회랑 프로젝트'[350]의 중요한 부분으로, 파키스탄의 아라비아해 항구 3개(카라치항, 포트 빈카심, 과다르항)를 국가 간 고속도로와 고속도로망을 통해 나머지 국가와 연결시키고, 나아가 아프가니스탄, 중앙아시아, 중국과 북쪽을 연결하는 것을 목표로 하고 있다.이 프로젝트는 1990년에 계획되었다.중국파키스탄경제회랑 프로젝트는 과다르 항과 카슈가르(중국)를 파키스탄 고속도로와 국도, 고속도로를 이용해 연결하는 것이 목적이다.

고속도로

고속도로는 파키스탄의 교통체계의 중추 역할을 한다. 총 도로 길이는 263,942킬로미터(164,006마일)로 승객의 92%와 내륙의 화물 수송의 96%를 차지한다.도로교통서비스는 주로 민간이 담당하고 있다.국도유지관리청은 국도유지 및 자동차도로 유지관리를 담당한다.고속도로와 고속도로 시스템은 주로 남쪽 항구와 인구가 많은 펀자브와 카이버-팍툰화 지방을 연결하는 남북 연결에 의존한다.이 네트워크는 전체 도로 길이의 4.6%에 불과하지만 전국 교통량의 85%를 차지한다.[308][351][352]

파키스탄 철도는 철도부(MoR) 산하의 철도 시스템을 운영하고 있다.1947년부터 1970년대까지 기차 시스템은 전국적인 고속도로 건설과 자동차 산업의 경제 호황까지 주요 교통 수단이었다.1990년대부터 철도에서 고속도로로 교통량의 현저한 변화가 있었다; 그 나라의 차량 도입 이후 도로에 대한 의존도가 증가했다.현재 철도의 내륙 교통 점유율은 승객은 8%, 화물 운송은 4%를 밑돌고 있다.[308]개인 교통수단이 자동차에 의해 지배되기 시작하면서, 전체 철도 선로는 1990-91년 8775킬로미터(5,453마일)에서 2011년 7,791킬로미터(4,841마일)로 감소했다.[351][353]파키스탄은 이 철도 서비스를 이용해 중국, 이란, 터키와의 무역을 활성화할 것으로 기대하고 있다.[354]

파키스탄에는 2013년 현재 151개의 공항과 비행장이 있으며 여기에는 군과 대부분 공공 소유의 민간 공항이 포함된다.[3]진나 국제공항은 파키스탄의 주요 국제 관문이지만 라호르, 이슬라마바드, 페샤와르, 퀘타, 파이살라바드, 시알코트, 물탄의 국제공항도 상당한 교통량을 처리하고 있다.

민간 항공산업은 1993년 규제를 완화한 민관이 혼재하고 있다.국영 파키스탄국제항공(PIA)은 국내 승객의 약 73%와 모든 국내 화물을 실어 나르는 주요 항공이자 지배적인 항공사인 반면 에어블루, 에어인더스 등 민간 항공사들도 저렴한 비용으로 비슷한 서비스를 제공하고 있다.

시포트

주요 항구는 신드주 카라치(카라치 항구, 포트카심)에 있다.[351][353]1990년대 이후 과다르 항, 파스니 항, 가다니 항이 건설되면서 일부 항만 작전이 발로치스탄으로 옮겨졌다.[351][353]과다르 항은 세계에서 가장 깊은 바다 항구다.[355]WEF의 세계경쟁력 보고서에 따르면 2007~2016년 파키스탄의 항만 인프라 품질등급은 3.7등급에서 4.1등급으로 상승했다.[356]

메트로

메트로 트레인

- 오렌지 라인 메트로 열차는 라호르에 있는 자동 급행열차다.[357]오렌지 선은 라호르 지하철에 제안된 세 개의 철도 노선 중 첫 번째 선이다.이 노선은 높이 25.4km(15.8mi)와 지하 1.72km(1.1mi)로 27.1km(16억 달러)에 걸쳐 있으며 비용은 2510억6,000만 루피(약 16억 달러)이다.[358]이 노선은 26개의 지하철역으로 구성되어 있으며 매일 25만 명 이상의 승객을 태울 수 있도록 설계되었다.이 노선은 2020년 10월 25일에 개통되었다.[359]

메트로 버스 및 BRT

- 라호르 메트로버스는 라호르 시에서 운행하는 버스 고속 환승 서비스다.[360]메트로버스 네트워크의 1단계는 2013년 2월에 개통되었다.그것은 파키스탄의 첫 메트로 버스 시스템이었다.

- 라왈핀디-이슬라마바드 메트로버스는 이슬라마바드 라왈핀디 대도시 지역에서 운행하는 22.5km(14.0mi) 버스 고속 환승 시스템이다.메트로버스 네트워크의 1단계는 2015년 6월 4일에 개통되었으며, 박 사무국과 이슬라마바드, 라왈핀디 사다르 사이에 22킬로미터에 걸쳐 있다.이 시스템은 전자티켓팅과 지능형 교통 시스템을 사용하며 펀자브 대중교통청이 관리한다.

- Multan Metrobus is a bus rapid transit (BRT) system in Multan.[361] Construction on the line began in May 2015, while operations commenced on 24 January 2017.[362]

- Peshawar Bus Rapid Transit (Peshawar BRT) is a bus rapid transit system in Peshawar, capital of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province. The construction of the project was started in October 2017 and was inaugurated on 13 August 2020, it is the fourth BRT system in Pakistan.

- Green Line Metrobus is the first phase of Karachi Metrobus that has been operational since 25 December 2021.[363] The Government of Pakistan financed the majority of the project.[364] Construction of the Green Line began on 26 February 2016.[365]

- Faisalabad shuttle train service and Faisalabad Metrobus are the proposed rapid transit projects in the city of Faisalabad. These projects are the part of a mega-project of China–Pakistan Economic Corridor.[366]

Other Systems

- Karachi Circular Railway is a partially active regional public transit system in Karachi, which serves the Karachi metropolitan area. KCR was fully operational between 1969 and 1999. Since 2001, restoration of the railway and restarting the system had been sought.[367] In November 2020, the KCR partially revived operations.[368]

- A tramway service service was started in 1884 in Karachi but was closed in 1975 due to various factors.[369] The Sindh Government is planning to restart the tramway services in the city, collaborating with Austrian experts.[370]

- In October 2019, a project for the construction of tramway service in Lahore has also been signed by the Punjab Government. This project will be launched under public-private partnership in a joint venture of European and Chinese companies along with the Punjab transport department.[371]

Flyovers and underpasses

Many flyovers and underpasses are located in major urban areas of the country to segregate the flow of traffic. The highest number of flyovers and under passes are located in Karachi, followed by Lahore.[372] Other cities having flyovers and underpasses for the regulation of flow of traffic includes Islamabad-Rawalpindi, Faisalabad, Gujranwala, Multan, Peshawar, Hyderabad, Quetta, Sargodha, Bahawalpur, Sukkur, Larkana, Rahim Yar Khan and Sahiwal etc.[373]

Beijing Underpass, Lahore is the longest underpass of Pakistan with a length of about 1.3 km (0.81 mi).[374] Muslim Town Flyover, Lahore is the longest flyover of the country with a length of about 2.6 km (1.6 mi).[375]

Science and technology

Developments in science and technology have played an important role in Pakistan's infrastructure and helped the country connect to the rest of the world.[376] Every year, scientists from around the world are invited by the Pakistan Academy of Sciences and the Pakistan Government to participate in the International Nathiagali Summer College on Physics.[377] Pakistan hosted an international seminar on "Physics in Developing Countries" for the International Year of Physics 2005.[378] The Pakistani theoretical physicist Abdus Salam won a Nobel Prize in Physics for his work on the electroweak interaction.[379] Influential publications and critical scientific work in the advancement of mathematics, biology, economics, computer science, and genetics have been produced by Pakistani scientists at both the domestic and international levels.[380]

In chemistry, Salimuzzaman Siddiqui was the first Pakistani scientist to bring the therapeutic constituents of the neem tree to the attention of natural products chemists.[381] Pakistani neurosurgeon Ayub Ommaya invented the Ommaya reservoir, a system for treatment of brain tumours and other brain conditions.[382] Scientific research and development play a pivotal role in Pakistani universities, government- sponsored national laboratories, science parks, and the industry.[383] Abdul Qadeer Khan, regarded as the founder of the HEU-based gas-centrifuge uranium enrichment program for Pakistan's integrated atomic bomb project.[384] He founded and established the Kahuta Research Laboratories (KRL) in 1976, serving as both its senior scientist and the Director-General until his retirement in 2001, and he was an early and vital figure in other science projects. Apart from participating in Pakistan's atomic bomb project, he made major contributions in molecular morphology, physical martensite, and its integrated applications in condensed and material physics.[385]

In 2010 Pakistan was ranked 43rd in the world in terms of published scientific papers.[386] The Pakistan Academy of Sciences, a strong scientific community, plays an influential and vital role in formulating recommendations regarding science policies for the government.[387] Pakistan was ranked 107th in the Global Innovation Index in 2020, down from 105th in 2019.[388][389][390][391]

The 1960s saw the emergence of an active space program led by SUPARCO that produced advances in domestic rocketry, electronics, and aeronomy. The space program recorded a few notable feats and achievements. The successful launch of its first rocket into space made Pakistan the first South Asian country to have achieved such a task.[392] Successfully producing and launching the nation's first space satellite in 1990, Pakistan became the first Muslim country and second South Asian country to put a satellite into space.[393]

Pakistan witnessed a fourfold increase in its scientific productivity in the past decade surging from approximately 2,000 articles per year in 2006 to more than 9,000 articles in 2015. Making Pakistan's cited article's higher than the BRIC countries put together.

—Thomson Reuters's Another BRIC in the Wall 2016 report[394]

As an aftermath of the 1971 war with India, the clandestine crash program developed atomic weapons partly motivated by fear and to prevent any foreign intervention, while ushering in the atomic age in the post cold war era.[180] Competition with India and tensions eventually led to Pakistan's decision to conduct underground nuclear tests in 1998, thus becoming the seventh country in the world to successfully develop nuclear weapons.[395]

Pakistan is the first and only Muslim country that maintains an active research presence in Antarctica.[396] Since 1991 Pakistan has maintained two summer research stations and one weather observatory on the continent and plans to open another full-fledged permanent base in Antarctica.[397]

Energy consumption by computers and usage has grown since the 1990s when PCs were introduced; Pakistan has about 82 million Internet users and is ranked as one of the top countries that have registered a high growth rate in Internet penetration as of 2020[update].[321] Key publications have been produced by Pakistan, and domestic software development has gained considerable international praise.[398]

As of May 2020, Pakistan has about 82 million internet users, making it the 9th-largest population of Internet users in the world.[321][322] Since the 2000s Pakistan has made a significant amount of progress in supercomputing, and various institutions offer research opportunities in parallel computing. The Pakistan government reportedly spends ₨ 4.6 billion on information technology projects, with emphasis on e-government, human resources, and infrastructure development.[399]

Education

The constitution of Pakistan requires the state to provide free primary and secondary education.[400]

At the time of the establishment of Pakistan as a state, the country had only one university, Punjab University in Lahore.[401] Very soon the Pakistan government established public universities in each of the four provinces, including Sindh University (1949), Peshawar University (1950), Karachi University (1953), and Balochistan University (1970). Pakistan has a large network of both public and private universities, which includes collaboration between the universities aimed at providing research and higher education opportunities in the country, although there is concern about the low quality of teaching in many of the newer schools.[402] It is estimated that there are 3,193 technical and vocational institutions in Pakistan,[403] and there are also madrassahs that provide free Islamic education and offer free board and lodging to students, who come mainly from the poorer strata of society.[404] Strong public pressure and popular criticism over extremists' usage of madrassahs for recruitment, the Pakistan government has made repeated efforts to regulate and monitor the quality of education in the madrassahs.[405]

Education in Pakistan is divided into six main levels: nursery (preparatory classes); primary (grades one through five); middle (grades six through eight); matriculation (grades nine and ten, leading to the secondary certificate); intermediate (grades eleven and twelve, leading to a higher secondary certificate); and university programmes leading to graduate and postgraduate degrees.[403] There is a network of private schools that constitutes a parallel secondary education system based on a curriculum set and administered by the Cambridge International Examinations of the United Kingdom. Some students choose to take the O-level and A level exams conducted by the British Council.[406] According to the International Schools Consultancy, Pakistan has 439 international schools.[407]

As a result of initiatives taken in 2007, the English medium education has been made compulsory in all schools across the country.[408] In 2012, Malala Yousafzai, a campaigner for female education, was shot by a Taliban gunman in retaliation for her activism.[409] Yousafzai went on to become the youngest ever Nobel laureate for her global education-related advocacy.[410] Additional reforms enacted in 2013 required all educational institutions in Sindh to begin offering Chinese language courses, reflecting China's growing role as a superpower and its increasing influence in Pakistan.[411] The literacy rate of the population is 62.3% as of 2018. The rate of male literacy is 72.5% while the rate of female literacy is 51.8%.[412] Literacy rates vary by region and particularly by sex; as one example, in tribal areas female literacy is 9.5%,[413] while Azad Jammu & Kashmir has a literacy rate of 74%.[414] With the advent of computer literacy in 1995, the government launched a nationwide initiative in 1998 with the aim of eradicating illiteracy and providing a basic education to all children.[415] Through various educational reforms, by 2015 the Ministry of Education expected to attain 100% enrollment levels among children of primary school age and a literacy rate of ~86% among people aged over 10.[416] Pakistan is currently spending 2.3 percent of its GDP on education;[417] which according to the Institute of Social and Policy Sciences is one of the lowest in South Asia.[418]

Demographics

As of 2020, Pakistan is the fifth most populous country in the world and accounts for about 2.8% of the world population.[419] The 2017 Census of Pakistan provisionally estimated the population to be 207.8 million.[420][421] This figure excludes data from Gilgit-Baltistan and Azad Kashmir, which is likely to be included in the final report.[422]

The population in 2017 represents a 57% increase from 1998.[420] The annual growth rate in 2016 was reported to be 1.45%, which is the highest of the SAARC nations, though the growth rate has been decreasing in recent years.[423] The population is projected to reach 263 million by 2030.[419]

At the time of the partition in 1947, Pakistan had a population of 32.5 million;[305][424] the population increased by ~57.2% between the years 1990 and 2009.[425] By 2030 Pakistan is expected to surpass Indonesia as the largest Muslim-majority country in the world.[426] Pakistan is classified as a "young nation", with a median age of 23.4 in 2016; about 104 million people were under the age of 30 in 2010. In 2016 Pakistan's fertility rate was estimated to be 2.68,[423] higher than its neighbour India (2.45).[427] Around 35% of the people are under 15.[305] The vast majority of those residing in southern Pakistan live along the Indus River, with Karachi being the most populous commercial city in the south.[428] In eastern, western, and northern Pakistan, most of the population lives in an arc formed by the cities of Lahore, Faisalabad, Rawalpindi, Sargodha, Islamabad, Gujranwala, Sialkot, Gujrat, Jhelum, Sheikhupura, Nowshera, Mardan, and Peshawar.[146] During 1990–2008, city dwellers made up 36% of Pakistan's population, making it the most urbanised nation in South Asia, which increased to 38% by 2013.[146][305][429] Furthermore, 50% of Pakistanis live in towns of 5,000 people or more.[430]

Expenditure on healthcare was ~2.8% of GDP in 2013. Life expectancy at birth was 67 years for females and 65 years for males in 2013.[429] The private sector accounts for about 80% of outpatient visits. Approximately 19% of the population and 30% of children under five are malnourished.[282] Mortality of the under-fives was 86 per 1,000 live births in 2012.[429]

Languages

More than sixty languages are spoken in Pakistan, including a number of provincial languages. Urdu—the lingua franca and a symbol of Muslim identity and national unity—is the national language and understood by over 75% of Pakistanis. It is the main medium of communication in the country, but the primary language of only 7% of the population.[431][432] Urdu and English are the official languages of Pakistan. English is primarily used in official business and government, and in legal contracts;[146] the local variety is known as Pakistani English. Punjabi, the most common language and the first language of 38.78% of the population,[431] is mostly spoken in the Punjab. Saraiki is mainly spoken in South Punjab, and Hindko is predominant in the Hazara region of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Pashto is the provincial language of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Sindhi is commonly spoken in Sindh, while Balochi is dominant in Balochistan. Brahui, a Dravidian language, is spoken by the Brahui people who live in Balochistan.[433][434] There are also speakers of Gujarati in Karachi.[435] Marwari, a Rajasthani language, is also spoken in parts of Sindh. Various languages such as Shina, Balti, and Burushaski are spoken in Gilgit-Baltistan, whilst languages such as Pahari, Gojri, and Kashmiri are spoken by many in Azad Kashmir.

Arabic is officially recognised by the constitution of Pakistan. It declares in article 31 No. 2 that "The State shall endeavour, as respects the Muslims of Pakistan (a) to make the teaching of the Holy Quran and Islamiat compulsory, to encourage and facilitate the learning of Arabic language ..."[436]

Immigration

Even after partition in 1947, Indian Muslims continued to migrate to Pakistan throughout the 1950s and 1960s, and these migrants settled mainly in Karachi and other towns of Sindh province.[438] The wars in neighboring Afghanistan during the 1980s and 1990s also forced millions of Afghan refugees into Pakistan. The Pakistan census excludes the 1.41 million registered refugees from Afghanistan,[439] who are found mainly in the Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa and tribal belt, with small numbers residing in Karachi and Quetta. Pakistan is home to one of the world's largest refugee populations.[440] In addition to Afghans, around 2 million Bangladeshis and half a million other undocumented people live in Pakistan. They are claimed to be from other areas such as Myanmar, Iran, Iraq, and Africa.[441]

Experts say that the migration of both Bengalis and Burmese (Rohingya) to Pakistan started in the 1980s and continued until 1998. Shaikh Muhammad Feroze, the chairman of the Pakistani Bengali Action Committee, claims that there are 200 settlements of Bengali-speaking people in Pakistan, of which 132 are in Karachi. They are also found in various other areas of Pakistan such as Thatta, Badin, Hyderabad, Tando Adam, and Lahore.[442] Large-scale Rohingya migration to Karachi made that city one of the largest population centres of Rohingyas in the world after Myanmar.[443] The Burmese community of Karachi is spread out over 60 of the city's slums such as the Burmi Colony in Korangi, Arakanabad, Machchar colony, Bilal colony, Ziaul Haq Colony, and Godhra Camp.[444]

Thousands of Uyghur Muslims have also migrated to the Gilgit-Baltistan region of Pakistan, fleeing religious and cultural persecution in Xinjiang, China.[445] Since 1989 thousands of Kashmiri Muslim refugees have sought refuge in Pakistan, complaining that many of the refugee women had been raped by Indian soldiers and that they were forced out of their homes by the soldiers.[446]

Ethnic groups

The major ethnic groups are Punjabis (44.7% of the country's population), Pashtuns, also known as Pathans (15.4%), Sindhis (14.1%), Saraikis (8.4%), Muhajirs (the Indian emigrants, mostly Urdu-speaking), who make up 7.6% of the population, and the Baloch with 3.6%.[3] The remaining 6.3% consist of a number of ethnic minorities such as the Brahuis,[433] the Hindkowans, the various peoples of Gilgit-Baltistan, the Kashmiris, the Sheedis (who are of African descent),[447] and the Hazaras.[448] There is also a large Pakistani diaspora worldwide, numbering over seven million,[449] which has been recorded as the sixth largest diaspora in the world.[450]

Urbanisation

Since achieving independence as a result of the partition of India, the urbanisation has increased exponentially, with several different causes. The majority of the population in the south resides along the Indus River, with Karachi the most populous commercial city.[428] In the east, west, and north, most of the population lives in an arc formed by the cities of Lahore, Faisalabad, Rawalpindi, Islamabad, Sargodha, Gujranwala, Sialkot, Gujrat, Jhelum, Sheikhupura, Nowshera, Mardan, and Peshawar. During the period 1990–2008, city dwellers made up 36% of Pakistan's population, making it the most urbanised nation in South Asia. Furthermore, more than 50% of Pakistanis live in towns of 5,000 people or more.[430] Immigration, from both within and outside the country, is regarded as one of the main factors contributing to urbanisation in Pakistan. One analysis of the 1998 national census highlighted the significance of the partition of India in the 1940s as it relates to urban change in Pakistan.[451] During and after the independence period, Urdu speaking Muslims from India migrated in large numbers to Pakistan, especially to the port city of Karachi, which is today the largest metropolis in Pakistan. Migration from other countries, mainly from those nearby, has further accelerated the process of urbanisation in Pakistani cities. Inevitably, the rapid urbanisation caused by these large population movements has also created new political and socio-economic challenges. In addition to immigration, economic trends such as the green revolution and political developments, among a host of other factors, are also important causes of urbanisation.[451]

| Rank | Name | Province | Pop. | Rank | Name | Province | Pop. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Karachi  Lahore | 1 | Karachi | Sindh | 14,916,456 | 11 | Bahawalpur | Punjab | 762,111 |  Faisalabad  Rawalpindi |

| 2 | Lahore | Punjab | 11,126,285 | 12 | Sargodha | Punjab | 659,862 | ||

| 3 | Faisalabad | Punjab | 3,204,726 | 13 | Sialkot | Punjab | 655,852 | ||

| 4 | Rawalpindi | Punjab | 2,098,231 | 14 | Sukkur | Sindh | 499,900 | ||

| 5 | Gujranwala | Punjab | 2,027,001 | 15 | Larkana | Sindh | 490,508 | ||

| 6 | Peshawar | Khyber Pakhtunkhwa | 1,970,042 | 16 | Sheikhupura | Punjab | 473,129 | ||

| 7 | Multan | Punjab | 1,871,843 | 17 | Rahim Yar Khan | Punjab | 420,419 | ||

| 8 | Hyderabad | Sindh | 1,734,309 | 18 | Jhang | Punjab | 414,131 | ||

| 9 | Islamabad | Capital Territory | 1,009,832 | 19 | Dera Ghazi Khan | Punjab | 399,064 | ||

| 10 | Quetta | Balochistan | 1,001,205 | 20 | Gujrat | Punjab | 390,533 | ||

Religion

The state religion in Pakistan is Islam.[457] Freedom of religion is guaranteed by the Constitution of Pakistan, which provides all its citizens the right to profess, practice and propagate their religion subject to law, public order, and morality.[458]

The majority of Pakistanis are Muslims (96.47%) followed by Hindus (2.14%) and Christians (1.27%). There are also people in Pakistan who follow other religions, such as Sikhism, Buddhism, Jainism and the minority of Parsi (who follow Zoroastrianism). The Kalash people maintain a unique identity and religion within Pakistan.[459]

Hinduism is mostly associated with Sindhis, and Pakistan hosts major events such as the Hinglaj Yatra pilgrimage. Hindu temples may be found throughout Sindh, where the dharma features prominently. Many Hindus in Pakistan complain about the prospect of religious violence against them and being treated like second-class citizens, and many have emigrated to India or further abroad.[460]

In addition, some Pakistanis also do not profess any faith (such as atheists and agnostics) in Pakistan. According to the 1998 census, people who did not state their religion accounted for 0.5% of the population.

Islam

Islam is the dominant religion.[461] About 96.47% of Pakistanis are Muslim, according to the 2017 Census.[431] Pakistan has the second-largest number of Muslims in the world after Indonesia.[462] and home for (10.5%) of the world's Muslim population.[463] The majority of them are Sunni and mostly follow Sufism (estimated between 75 and 95%)[464][465] while Shias represent between 5–25%.[464][3][466] In 2019, the Shia population in Pakistan was estimated to be 42 million out of total population of 210 million.[467] Pakistan also has the largest Muslim city in the world (Karachi).[468]

The Ahmadis, a small minority representing 0.22–2% of Pakistan's population,[469] are officially considered non-Muslims by virtue of the constitutional amendment.[470] The Ahmadis are particularly persecuted, especially since 1974 when they were banned from calling themselves Muslims. In 1984, Ahmadiyya places of worship were banned from being called "mosques".[471] As of 2012[update], 12% of Pakistani Muslims self-identify as non-denominational Muslims.[472] There are also several Quraniyoon communities.[473] They are mainly concentratd in the Lalian Tehsil, Chiniot District, where approximately 13% of the population.[474]

Sufism, a mystical Islamic tradition, has a long history and a large following among the Sunni Muslims in Pakistan, at both the academic and popular levels. Popular Sufi culture is centered around gatherings and celebrations at the shrines of saints and annual festivals that feature Sufi music and dance. Two Sufis whose shrines receive much national attention are Ali Hajweri in Lahore (c. 12th century)[475] and Shahbaz Qalander in Sehwan, Sindh (c. 12th century).[476]

There are two levels of Sufism in Pakistan. The first is the 'populist' Sufism of the rural population. This level of Sufism involves belief in intercession through saints, veneration of their shrines, and forming bonds (Mureed) with a pir (saint). Many rural Pakistani Muslims associate with pirs and seek their intercession.[477] The second level of Sufism in Pakistan is 'intellectual Sufism', which is growing among the urban and educated population. They are influenced by the writings of Sufis such as the medieval theologian al-Ghazali, the Sufi reformer Shaykh Aḥmad Sirhindi, and Shah Wali Allah.[478] Contemporary Islamic fundamentalists criticise Sufism's popular character, which in their view does not accurately reflect the teachings and practice of Muhammad and his companions.[479]

Hinduism

Hinduism is the second-largest religion in Pakistan after Islam and is followed by 2.14% of the population according to the 2017 census.[5][481] According to the 2010 Pew report, Pakistan had the fifth-largest Hindu population in the world.[482] In the 2017 census, the Hindu population was found to be 4,444,437.[483] Hindus are found in all provinces of Pakistan but are mostly concentrated in Sindh, where they account for 8.73% of the population.[5] Umerkot district (52.15%) is the only Hindu majority district in Pakistan. Tharparkar district has the highest population of Hindus in terms of absolute terms. The four districts in Sindh- Umerkot, Tharparkar, Mirpurkhas and Sanghar hosts more than half of the Hindu population in Pakistan.[474]

At the time of Pakistan's creation, the 'hostage theory' gained currency. According to this theory, the Hindu minority in Pakistan was to be given a fair deal in Pakistan in order to ensure the protection of the Muslim minority in India.[484] However, Khawaja Nazimuddin, the secondPrime Minister of Pakistan, stated:

I do not agree that religion is a private affair of the individual nor do I agree that in an Islamic state every citizen has identical rights, no matter what his caste, creed or faith be.[485]

Some Hindus in Pakistan feel that they are treated as second-class citizens and many have continued to migrate to India.[460] Pakistani Hindus faced riots after the Babri Masjid demolition[486] and have experienced other attacks, forced conversions, and abductions.[487]

Christianity and other religions

Christians formed the next largest religious minority after Hindus, with 1.27% of the population following it.[431] The highest concentration of Christians in Pakistan is in Lahore District (5%) in Punjab province and in Islamabad Capital Territory (over 4% Christian). There is a Roman Catholic community in Karachi that was established by Goan and Tamil migrants when Karachi's infrastructure was being developed by the British during the colonial administration between World War I and World War II.[474]

They are followed by the Bahá'í Faith, which had a following of 30,000, then Sikhism, Buddhism, and Zoroastrianism, each back then claiming 20,000 adherents,[488] and a very small community of Jains.

1.0% of the population identified as atheist in 2005. However, the figure rose to 2.0% in 2012 according to Gallup.[489]

Culture and society

Civil society in Pakistan is largely hierarchical, emphasising local cultural etiquette and traditional Islamic values that govern personal and political life. The basic family unit is the extended family,[490] although for socio-economic reasons there has been a growing trend towards nuclear families.[491] The traditional dress for both men and women is the Shalwar Kameez; trousers, jeans, and shirts are also popular among men.[41] In recent decades, the middle class has increased to around 35 million and the upper and upper-middle classes to around 17 million, and power is shifting from rural landowners to the urbanised elites.[492] Pakistani festivals, including Eid-ul-Fitr, Eid-ul-Azha, Ramazan, Christmas, Easter, Holi, and Diwali, are mostly religious in origin.[490] Increasing globalisation has resulted in Pakistan ranking 56th on the A.T. Kearney/FP Globalization Index.[493]

Clothing, arts, and fashion

The Shalwar Kameez is the national dress of Pakistan and is worn by both men and women in all four provinces: Punjab, Sindh, Balochistan, and Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa, and Azad Kashmir. Each province has its own style of Shalwar Kameez. Pakistanis wear clothes in a range of exquisite colours and designs and in type of fabric (silk, chiffon, cotton, etc.). Besides the national dress, domestically tailored suits and neckties are often worn by men, and are customary in offices, schools, and social gatherings.[494]

The fashion industry has flourished in the changing environment of the fashion world. Since Pakistan came into being, its fashion has evolved in different phases and developed a unique identity. Today, Pakistani fashion is a combination of traditional and modern dress and has become a mark of Pakistani culture. Despite modern trends, regional and traditional forms of dress have developed their own significance as a symbol of native tradition. This regional fashion continues to evolve into both more modern and purer forms. The Pakistan Fashion Design Council based in Lahore organizes PFDC Fashion Week and the Fashion Pakistan Council based in Karachi organizes Fashion Pakistan Week. Pakistan's first fashion week was held in November 2009.[495]

Media and entertainment

The private print media, state-owned Pakistan Television Corporation (PTV), and Pakistan Broadcasting Corporation (PBC) for radio were the dominant media outlets until the beginning of the 21st century. Pakistan now has a large network of domestic, privately owned 24-hour news media and television channels.[496] A 2016 report by the Reporters Without Borders ranked Pakistan 147th on the Press Freedom Index, while at the same time terming the Pakistani media "among the freest in Asia when it comes to covering the squabbling among politicians."[497] The BBC terms the Pakistani media "among the most outspoken in South Asia".[498] Pakistani media has also played a vital role in exposing corruption.[499]

The Lollywood, Kariwood, Punjabi and Pashto film industry is based in Karachi, Lahore and Peshawar. While Bollywood films were banned from public cinemas from 1965 until 2008, they have remained an important part of popular culture.[500] In contrast to the ailing Pakistani film industry, Urdu televised dramas and theatrical performances continue to be popular, as many entertainment media outlets air them regularly.[501] Urdu dramas dominate the television entertainment industry, which has launched critically acclaimed miniseries and featured popular actors and actresses since the 1990s.[502] In the 1960s–1970s, pop music and disco (1970s) dominated the country's music industry. In the 1980s–1990s, British influenced rock music appeared and jolted the country's entertainment industry.[503] In the 2000s, heavy metal music gained popular and critical acclaim.[504]

Pakistani music ranges from diverse forms of provincial folk music and traditional styles such as Qawwali and Ghazal Gayaki to modern musical forms that fuse traditional and western music.[505][506] Pakistan has many famous folk singers. The arrival of Afghan refugees in the western provinces has stimulated interest in Pashto music, although there has been intolerance of it in some places.[507]

Diaspora

According to the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Pakistan has the sixth-largest diaspora in the world.[450] Statistics gathered by the Pakistani government show that there are around 7 million Pakistanis residing abroad, with the vast majority living in the Middle East, Europe, and North America.[508] Pakistan ranks 10th in the world for remittances sent home.[302][509] The largest inflow of remittances, as of 2016[update], is from Saudi Arabia, amounting to $5.9 billion.[510] The term Overseas Pakistani is officially recognised by the Government of Pakistan. The Ministry of Overseas Pakistanis was established in 2008 to deal exclusively with all matters of overseas Pakistanis such as attending to their needs and problems, developing projects for their welfare, and working for resolution of their problems and issues. Overseas Pakistanis are the second-largest source of foreign exchange remittances to Pakistan after exports. Over the last several years, home remittances have maintained a steadily rising trend, with a more than 100% increase from US$8.9 billion in 2009–10 to US$19.9 billion in 2015–16.[301][509]

The Overseas Pakistani Division (OPD) was created in September 2004 within the Ministry of Labour (MoL). It has since recognised the importance of overseas Pakistanis and their contribution to the nation's economy. Together with Community Welfare Attaches (CWAs) and the Overseas Pakistanis Foundation (OPF), the OPD is making efforts to improve the welfare of Pakistanis who reside abroad. The division aims to provide better services through improved facilities at airports, and suitable schemes for housing, education, and health care. It also facilitates the reintegration into society of returning overseas Pakistanis. Notable members of the Pakistani diaspora include the London Mayor Sadiq Khan, the UK cabinet member Sajid Javid, the former UK Conservative Party chair Baroness Warsi, the singers Zayn Malik and Nadia Ali, MIT physics Professor Dr. Nergis Mavalvala, the actors Riz Ahmed and Kumail Nanjiani, the businessmen Shahid Khan and Sir Anwar Pervez, Boston University professors Adil Najam and Hamid Nawab, Texas A&M professor Muhammad Suhail Zubairy, Yale professor Sara Suleri, UC San Diego professor Farooq Azam and the historian Ayesha Jalal.

Literature and philosophy

Pakistan has literature in Urdu, Sindhi, Punjabi, Pashto, Baluchi, Persian, English, and many other languages.[511] The Pakistan Academy of Letters is a large literary community that promotes literature and poetry in Pakistan and abroad.[512] The National Library publishes and promotes literature in the country. Before the 19th century, Pakistani literature consisted mainly of lyric and religious poetry and mystical and folkloric works. During the colonial period, native literary figures were influenced by western literary realism and took up increasingly varied topics and narrative forms. Prose fiction is now very popular.[513][514]

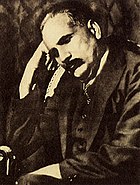

The national poet of Pakistan, Muhammad Iqbal, wrote poetry in Urdu and Persian. He was a strong proponent of the political and spiritual revival of Islamic civilisation and encouraged Muslims all over the world to bring about a successful revolution.[clarification needed][516] Well-known figures in contemporary Pakistani Urdu literature include Josh Malihabadi Faiz Ahmed Faiz and Saadat Hasan Manto. Sadequain and Gulgee are known for their calligraphy and paintings.[514] The Sufi poets Shah Abdul Latif, Bulleh Shah, Mian Muhammad Bakhsh, and Khawaja Farid enjoy considerable popularity in Pakistan.[517] Mirza Kalich Beg has been termed the father of modern Sindhi prose.[518] Historically, philosophical development in the country was dominated by Muhammad Iqbal, Sir Syed Ahmad Khan, Muhammad Asad, Maududi, and Mohammad Ali Johar.[519]

Ideas from British and American philosophy greatly shaped philosophical development in Pakistan. Analysts such as M. M. Sharif and Zafar Hassan established the first major Pakistani philosophical movement in 1947.[clarification needed][520] After the 1971 war, philosophers such as Jalaludin Abdur Rahim, Gianchandani, and Malik Khalid incorporated Marxism into Pakistan's philosophical thinking. Influential work by Manzoor Ahmad, Jon Elia, Hasan Askari Rizvi, and Abdul Khaliq brought mainstream social, political, and analytical philosophy to the fore in academia.[521] Works by Noam Chomsky have influenced philosophical ideas in various fields of social and political philosophy.[522]

Architecture

Four periods are recognised in Pakistani architecture: pre-Islamic, Islamic, colonial, and post-colonial. With the beginning of the Indus civilization around the middle of the 3rd millennium BCE,[523] an advanced urban culture developed for the first time in the region, with large buildings, some of which survive to this day.[524] Mohenjo Daro, Harappa, and Kot Diji are among the pre-Islamic settlements that are now tourist attractions.[153] The rise of Buddhism and the influence of Greek civilisation led to the development of a Greco-Buddhist style,[525] starting from the 1st century CE. The high point of this era was the Gandhara style. An example of Buddhist architecture is the ruins of the Buddhist monastery Takht-i-Bahi in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa.[526]

The arrival of Islam in what is today Pakistan meant the sudden end of Buddhist architecture in the area and a smooth transition to the predominantly pictureless Islamic architecture. The most important Indo-Islamic-style building still standing is the tomb of the Shah Rukn-i-Alam in Multan. During the Mughal era, design elements of Persian-Islamic architecture were fused with and often produced playful forms of Hindustani art. Lahore, as the occasional residence of Mughal rulers, contains many important buildings from the empire. Most prominent among them are the Badshahi Mosque, the fortress of Lahore with the famous Alamgiri Gate, the colourful, Mughal-style Wazir Khan Mosque,[527] the Shalimar Gardens in Lahore, and the Shahjahan Mosque in Thatta. In the British colonial period, predominantly functional buildings of the Indo-European representative style developed from a mixture of European and Indian-Islamic components. Post-colonial national identity is expressed in modern structures such as the Faisal Mosque, the Minar-e-Pakistan, and the Mazar-e-Quaid. Several examples of architectural infrastructure demonstrating the influence of British design can be found in Lahore, Peshawar, and Karachi.[528]

Food and drink

Traditional food

Pakistani cuisine is similar to that of other regions of South Asia, with some of it being originated from the royal kitchens of 16th-century Mughal emperors.[530] Most of those dishes have their roots in British, Indian, Central Asian and Middle Eastern cuisine.[531] Unlike Middle Eastern cuisine, Pakistani cooking uses large quantities of spices, herbs, and seasoning. Garlic, ginger, turmeric, red chili, and garam masala are used in most dishes, and home cooking regularly includes curry, roti, a thin flatbread made from wheat, is a staple food, usually served with curry, meat, vegetables, and lentils. Rice is also common; it is served plain, fried with spices, and in sweet dishes.[149][532]

Lassi is a traditional drink in the Punjab region. Black tea with milk and sugar is popular throughout Pakistan and is consumed daily by most of the population.[41][533] Sohan halwa is a popular sweet dish from the southern region of Punjab province and is enjoyed all over Pakistan.[534]

Sports

Most sports played in Pakistan originated and were substantially developed by athletes and sports fans from the United Kingdom who introduced them during the British Raj. Field hockey is the national sport of Pakistan; it has won three gold medals in the Olympic Games held in 1960, 1968, and 1984.[535] Pakistan has also won the Hockey World Cup a record four times, held in 1971, 1978, 1982, and 1994.[536]

Cricket, however, is the most popular game across the country.[537] The country has had an array of success in the sport over the years, and has the distinct achievement of having won each of the major ICC international cricket tournaments: ICC Cricket World Cup, ICC World Twenty20, and ICC Champions Trophy; as well as the ICC Test Championship.[538] The cricket team (known as Shaheen) won the Cricket World Cup held in 1992; it was runner-up once, in 1999. Pakistan was runner-up in the inaugural World Twenty20 (2007) in South Africa and won the World Twenty20 in England in 2009. In March 2009, militants attacked the touring Sri Lankan cricket team,[539] after which no international cricket was played in Pakistan until May 2015, when the Zimbabwean team agreed to a tour. Pakistan also won the 2017 ICC Champions Trophy by defeating arch-rivals India in the final.

Pakistan Super League is one of the largest cricket leagues of the world with a brand value of about ₨32.26 billion (US$200 million).[540]

Association Football is the second most played sports in Pakistan and it is organised and regulated by the Pakistan Football Federation.[541] Football in Pakistan is as old as the country itself. Shortly after the creation of Pakistan in 1947, the Pakistan Football Federation (PFF) was created, and Muhammad Ali Jinnah became its first Patron-in-Chief.[542] The highest football division in Pakistan is the Pakistan Premier League.[543] Pakistan is known as one of the best manufacturer of the official FIFA World Cup ball.[544] The best football players to play for Pakistan are Kaleemullah, Zesh Rehman, Muhammad Essa, Haroon Yousaf and Muhammad Adil.