모나크나비

Monarch butterfly| 모나크나비 | |

|---|---|

| |

| 남자 | |

| |

| 여자 | |

| 과학적 분류 | |

| 도메인: | 진핵생물 |

| 왕국: | 애니멀리아 |

| 문: | 지족류 |

| 클래스: | 인스펙타 |

| 순서: | 나비목 |

| 가족: | 님팔리대 |

| 속: | 다나우스 |

| 종: | 플렉스티푸스 |

| 이항명 | |

| 다나우스플렉시푸스 | |

| |

| 동의어 | |

피에드라 헤라다

왕나비 또는 간단히 왕나비(Danaus plexippus)는 왕나비과에 속하는 왕나비의 일종입니다.[6] 지역에 따라 다른 흔한 이름으로는 밀크위드, 커먼타이거, 방랑자, 검은정갈색 등이 있습니다.[7] 그것은 북미 나비들 중 가장 친숙하고 상징적인 꽃가루 매개자 중 하나이지만 [8]우유 잡초의 특별히 효과적인 꽃가루 매개자는 아닙니다.[9][10] 날개의 특징은 쉽게 알아볼 수 있는 검은색, 주황색, 흰색이며 날개 길이는 8.9-10.2cm입니다.[11] 뮐러 흉내를 내는 부왕나비는 색깔과 패턴이 비슷하지만, 눈에 띄게 작고 각각의 뒷날개에 걸쳐 여분의 검은 줄무늬가 있습니다.

북아메리카 동부의 군주 개체군은 미국 북부와 중부, 캐나다 남부에서 플로리다와 멕시코로 매년 남하하는 늦여름/가을 본능적인 이주로 유명합니다.[6] 가을 이주 동안, 군주들은 수천 마일을 차지하며, 봄에 북쪽으로 그에 상응하는 다세대 귀환을 합니다. 로키산맥 서쪽의 북아메리카 서부의 군주 개체군은 종종 남부 캘리포니아 지역으로 이주하지만, 월동하는 멕시코 지역에서도 개체가 발견되었습니다.[12][13] 2009년, 모나크들은 국제 우주 정거장에서 사육되었고, 우주 정거장의 상업적인 일반 생물 처리 장치에 위치한 번데기에서 성공적으로 나타났습니다.[14][15]

어원

"군주"라는 이름은 영국의 윌리엄 3세를 기리기 위해 지어졌다고 믿어지는데, 나비의 주요 색깔이 왕의 부제인 오렌지 왕자의 것이기 때문입니다.[16] 그 군주는 칼 린네가 1758년 그의 자연의 체계에서 처음으로 묘사했고 파필리오 속에 넣었습니다.[17] 1780년, Kluk의 Jan Krzysztof Kluk은 군주를 새로운 속 Danau의 모식종으로 사용했습니다. 적어도 1883년에서 1944년 사이에 출판된 연구에서 아노시아 플렉시푸스로 확인되었지만,[18] 그 속명은 2005년에 다나우스로 병합되었습니다.[19]

제우스의 증손자인 다나오스 (고대 그리스 δ να ός)는 이집트나 리비아의 신화 속에 나오는 왕으로 아르고스를 세웠습니다. 플렉시푸스 (π λήξιππος)는 다나오스의 쌍둥이 형제인 아이집토스의 50명의 아들들 중 한 명이었습니다. 호메로스 그리스어로 그의 이름은 "말 위에서 재촉하는 자", 즉 "라이더" 또는 "차리어"를 의미합니다.[20] 린네는 Systema Naturae의 10번째 판인 467쪽 하단에 [21]Papilio plexippus가 속한 속의 구분인 Danai festivi의 이름이 이집트의 아들들로부터 유래되었다고 썼습니다. 린네는 알려진 모든 나비 종을 포함하는 그의 큰 속 파필리오를 우리가 지금 아속이라고 부르는 것으로 나누었습니다. 다나이 페스티비는 밝은 흰색 날개를 가진 종들을 포함하는 다나이 칸디다와 대조적으로 다채로운 종들을 포함하는 "아속" 중 하나를 형성했습니다. 린네는 다음과 같이 썼습니다: "다나오룸 칸디도룸의 이름은 다나우스의 딸들, 다나우스의 딸들, 다나우스의 아들들로부터 따온 것입니다."

로버트 마이클 파일(Robert Michael Pyle)은 다나우스의 증손녀 다나 ë(그리스 δα νάη)의 남성화된 버전을 제안했는데, 제우스는 이 나비의 이름에 더 적합한 출처로 보였습니다.

분류학

모나크족은 님팔리대과의 다나이네아과에 속합니다. 다나이나는 이전에는 다나이과와 별개의 과로 간주되었습니다.[23] 왕나비의 세 종류는 다음과 같습니다.

- 1758년 린네에 의해 묘사된 D. plexippus는 북아메리카의 왕나비로 가장 흔하게 알려진 종입니다. 그 범위는 실제로 하와이, 호주, 뉴질랜드, 스페인 및 태평양 제도를 포함한 전 세계적으로 확장됩니다.

- 남쪽의 군주인 D. erippus는 1775년 Pieter Cramer에 의해 묘사되었습니다. 이 종은 남아메리카의 열대 및 아열대 위도, 주로 브라질, 우루과이, 파라과이, 아르헨티나, 볼리비아, 칠레 및 페루 남부에서 발견됩니다. 남미의 군주와 북미의 군주는 한때 하나의 종이었을지도 모릅니다. 일부 연구원들은 남부 군주가 약 2백만 년 전 플라이오세 말기에 군주의 인구로부터 분리되었다고 믿습니다. 해수면은 더 높았고, 아마조나스 저지대 전체는 제한된 나비 서식지를 제공하는 기수 늪의 광활한 확장이었습니다.[19]

- 1819년 장 밥티스트 고다르트가 묘사한 자메이카의 군주 D. cleophile은 자메이카부터 히스파니올라까지 다양합니다.[2]

D. plexippus의 6종의 아종과 2종의 색상 형태가 확인되었습니다.[7]

- 1758년 린네(Linnaeus)에 의해 기술된 D. p. plexippus - 지명 아종은 북아메리카 대부분에서 알려진 이주 아종입니다.

- D. p. nigrippus (Richard Haensch, 1909) – 남아메리카 - forma: Danais [sic] archippus f. nigrippus. Hay-Roe 등은 2007년에 이 분류군을 아종으로[26] 확인했습니다.

- D. p. megallippe (Jacob Hübner, [1826]) – 비이주성 아종으로 플로리다와 조지아에서 남쪽으로 카리브해와 중앙 아메리카 전역에서 아마존 강까지 발견됩니다.

- D. p. leucogyne (Arthur G. Butler, 1884) − St. 토마스.

- 1941년 P. portoricensis Austin Hobart Clark - 푸에르토리코

- D. P. 토바기 오스틴 호바트 클라크, 1941 - 토바고

오아후의 흰 형태의 개체수는 10%에 육박하고 있습니다. 다른 하와이 섬에서는 흰색 형태가 비교적 낮은 빈도로 나타납니다. 흰 군주 (D. p. p. "form nivosus")는 호주, 뉴질랜드, 인도네시아, 그리고 미국을 포함한 전 세계에서 발견되었습니다.[24] 그러나 일부 분류학자들은 이러한 분류에 동의하지 않습니다.[19][26]

게놈

그 군주는 유전체 염기서열을 분석한 최초의 나비였습니다.[27]: 12 2억 7300만 개의 염기쌍 초안 서열에는 16,866개의 단백질 코딩 유전자 세트가 포함되어 있습니다. 게놈은 연구자들에게 여름과 철새 군주 사이에 차별적으로 발현되는 이주 행동, 일주기 시계, 청소년 호르몬 경로, 마이크로RNA에 대한 통찰력을 제공합니다.[28][29][30] 보다 최근에는 군주의 이주와 경고 색상의 유전적 기초가 설명되었습니다.[31]

북미 동부와 서부의 이주 개체군 사이에는 유전적 분화가 존재하지 않습니다.[27]: 16 최근의 연구는 군주의 게놈에서 이주를 조절하는 특정 영역을 확인했습니다. 이주하는 군주와 이주하지 않는 군주 사이에는 유전적 차이가 보이지 않지만 이주하는 군주에서는 유전자가 발현되지만 비이주 군주에서는 발현되지 않습니다.[32]

2015년 출판물은 북미 군주의[33] 게놈에서 말벌 브라코바이러스의 유전자를 확인하여 군주 나비가 유전자 변형 유기체라는 기사로 이어졌습니다.[34][35]

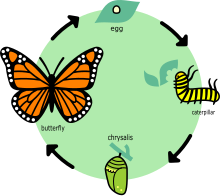

생애주기

모든 나비목과 마찬가지로, 군주들은 완전한 변신을 겪습니다; 그들의 생애 주기는 알, 애벌레, 번데기, 그리고 성충의 네 단계를 가집니다. 모나크는 25일 이내에 따뜻한 여름 기온 동안 알에서 성충으로 전환되며, 시원한 봄 조건 동안에는 7주까지 연장됩니다. 유충과 그들의 밀크위드 숙주는 발달하는 동안 기상 이변, 포식자, 기생충 및 질병에 취약하며 일반적으로 군주 알과 애벌레의 10% 미만이 생존합니다.[27]: 21–22

계란

알은 유충으로 섭취된 물질과 교미하는 동안 수컷으로부터 받은 정자에서 유래합니다.[36] 암컷 군주들은 봄과 여름 동안에 주로 밀크위드 식물의 어린 잎의 아래쪽에 알을 낳습니다.[37] 암컷은 소량의 풀을 분비하여 알을 식물에 직접 붙입니다. 그들은 보통 2주에서 5주 동안 300개에서 500개의 알을 낳습니다.[38]

알은 크림색 또는 연두색이며, 모양은 난형에서 원뿔형이며, 크기는 약 1.2 mm × 0.9 mm (0.047 인치 × 0.035 인치)입니다. 이 알들은 무게가 각각 0.5 mg (0.0077 gr) 미만이며, 점에서 정점까지 세로로 형성된 융기선(ridge)을 가지고 있습니다. 비록 각각의 계란은 1 ⁄1,000 암컷의 질량으로 알을 품을 수 있습니다. 암컷들은 나이가 들면서 더 작은 알을 낳습니다. 큰 암컷은 큰 알을 낳습니다.[36] 암컷이 여러 번 짝짓기를 할 수 있는 알의 수는 1,180개에 이릅니다.[39]

알은 유충이나 애벌레로 발달하고 부화하는 데 3~8일이 걸립니다.[27]: 21 자손의 밀크위드 섭취는 건강에 도움이 되고 포식자로부터 그들을 방어하는 데 도움이 됩니다.[40][41] 모나크들은 남쪽의 이동 경로를 따라 알을 낳습니다.[42]

라바

애벌레(애벌레)는 5개의 단계(인스타)가 있으며, 각 인스타의 끝에서 털갈이를 합니다. 인스타그램은 온도와 음식 이용 가능성 등의 요인에 따라 약 3~5일 정도 지속됩니다.[6][43]

알에서 나오는 1령 애벌레는 옅은 녹색 또는 회백색으로 반짝이며 거의 반투명하며 머리는 크고 검은색입니다. 밴딩 착색이나 촉수가 부족합니다. 유충이나 애벌레는 알통을 먹고 원을 그리며 밀크위드를 먹기 시작하며, 종종 잎에 특징적인 호 모양의 구멍을 남깁니다. 오래된 1령 유충은 녹색을 띤 배경에 어두운 줄무늬를 가지고 있으며 나중에 앞 촉수가 되는 작은 돌기를 발달시킵니다. 1령의 길이는 보통 2~6mm(0.079~0.236인치)입니다.[43]

2령 유충은 흰색, 노란색, 검은색 가로띠의 특징적인 패턴을 발달시킵니다. 애벌레는 머리에 노란색 삼각형이 있고 이 중앙 삼각형 주위에 두 세트의 노란색 띠가 있습니다. 더 이상 반투명하지 않으며 짧은 강모로 덮여 있습니다. 검은 촉수 한 쌍이 자라기 시작하는데, 가슴에는 더 큰 한 쌍이, 복부에는 더 작은 한 쌍이 있습니다. 2령의 길이는 보통 6mm(0.24인치)에서 1cm(0.39인치) 사이입니다.[43]

3령 유충은 더 뚜렷한 띠를 가지고 있고 두 쌍의 촉수는 더 길어집니다. 가슴에 있는 다리는 머리 근처에 있는 작은 쌍과 뒤에 있는 더 큰 쌍으로 분화합니다. 3령 유충은 보통 잎 가장자리의 절단 동작을 사용하여 먹이를 먹습니다. 3령의 길이는 보통 1~1.5cm(0.39~0.59인치)입니다.[43]

4령 유충은 밴딩 패턴이 다릅니다. 등 쪽의 앞다리에 흰 반점이 생기며, 보통 길이는 1.5~2.5cm(0.59~0.98인치) 사이입니다.[43]

5령 유충은 앞다리가 작고 머리에 매우 가까운 앞다리와 함께 더 복잡한 밴딩 패턴과 흰색 점이 있습니다. 5령 유충은 먹고 있는 잎의 잎자루에 있는 얕은 마디를 씹는 경우가 많은데, 이로 인해 잎이 수직으로 떨어지게 됩니다. 길이는 2.5~4.5cm(0.98~1.77인치)입니다.[6][43]

애벌레가 성장을 완료하면 길이는 4.5cm(1.8인치), 너비는 7~8mm(0.28~0.31인치)이며, 길이는 2~6mm(0.079~0.236인치), 너비는 0.5~1.5mm(0.020~0.059인치)인 1령에 비해 무게는 약 1.5g(0.053온스)입니다. 5령 유충은 크기와 무게가 크게 늘어납니다. 그들은 먹이를 중단하고 번데기를 위한 장소를 찾는 동안 종종 밀크위드 식물에서 멀리 발견됩니다.[43]

실험실 환경에서 애벌레의 4령과 5령 단계는 먹이 이용 가능성이 낮은 공격적인 행동의 징후를 보였습니다. 공격을 받은 애벌레는 밀크위드 잎을 먹고 있을 때 공격을 받고, 애벌레는 밀크위드를 먹을 때 공격을 받은 것으로 나타났습니다.[44] 이는 왕나비 애벌레의 공격적인 행동을 보여주는 것으로, 밀크위드의 보급으로 인한 것입니다.

번데기

애벌레는 번데기나 번데기 단계를 준비하기 위해 안전한 번데기 장소를 선택하고, 아래를 향한 수평면에 실크 패드를 돌립니다. 이 때, 그것은 돌아서서 마지막 뒷다리 한 쌍으로 단단히 고정되고 문자 J의 형태로 거꾸로 매달려 있습니다. 약 12-16시간 동안 "J-행잉"을 한 후, 그것은 곧 몸을 펴서 머리 뒤로 피부가 갈라지기 몇 초 전에 연동 운동에 들어갑니다. 그런 다음 몇 분 동안 껍질을 벗기며 녹색 번데기를 드러냅니다. 처음에, 번데기는 길고, 부드럽고, 다소 무정형이지만, 몇 시간이 지나면서, 그것은 뚜렷한 모양으로 압축됩니다 – 불투명하고, 담록색의 번데기로 바닥 근처에 작은 황금 점들이 있고, 꼭대기 근처의 등 쪽에 금색과 검은색 테두리가 있습니다.[45] 처음에는 외골격이 부드럽고 깨지기 쉽지만 하루 정도면 단단해지고 내구성이 좋아집니다. 이 지점에서, 길이는 약 2.5 cm (0.98 인치), 너비는 약 10–12 mm (0.39–0.47 인치)이며, 무게는 약 1.2 g (0.042 oz)입니다. 보통 여름 기온에서는 8~15일(보통 11~12일)이면 성숙합니다. 이 번데기 단계에서 성체 나비는 안에서 형성됩니다. 출현하기 하루 정도 전에, 외골격은 먼저 반투명해지고 번데기는 더 푸르게 됩니다. 마침내, 12시간 정도 안에, 그것은 투명해지고, 그것이 개기 전에 안에 있는 나비의 검은색과 오렌지색을 드러냅니다.[46][47]

어덜트

성충은 번데기가 된 지 약 2주 후에 번데기에서 나옵니다. 이 신흥 성체는 날개에 유체와 공기를 주입하여 팽창하고 건조하며 뻣뻣해지는 동안 몇 시간 동안 거꾸로 매달려 있습니다. 그런 다음 나비는 날개를 펴고 젖힙니다. 일단 조건이 허락되면, 그것은 날아다니며 다양한 꿀 식물을 먹고 삽니다. 번식기 동안 성체는 4-5일 안에 성체에 도달합니다. 그러나 이주 세대는 월동이 완료될 때까지 성숙기에 도달하지 않습니다.[48]

어른 날개폭은 8.9에서 10.2 센티미터입니다.[11] 날개 윗면은 황갈색의 주황색이고, 맥과 가장자리는 검은색이며, 가장자리에 작은 흰색 반점이 두 개 연속 발생합니다. 모나크 앞날개는 또한 끝 근처에 몇 개의 주황색 반점이 있습니다. 날개 밑면은 비슷하지만 앞날개와 뒷날개의 끝은 황갈색 대신 황갈색이고 흰색 반점이 더 큽니다.[49] 이주 초기에는 날개의 모양과 색깔이 변하며 후기 이주자보다 더 붉고 길쭉하게 보입니다.[50] 날개의 크기와 모양은 이동하는 군주와 비이동하는 군주 사이에 다릅니다. 북아메리카 동부의 모나크들은 서부 개체군보다 더 크고 더 각진 앞날개를 가지고 있습니다.[27]

북아메리카 동부 개체군에서는 날개의 물리적 차원에서 전체적인 날개 크기가 다양합니다. 수컷은 암컷보다 날개가 더 큰 경향이 있고, 일반적으로 암컷보다 더 무겁습니다. 남성과 여성 모두 흉부 치수가 비슷합니다. 암컷 군주들은 날개가 두꺼운 경향이 있었는데, 이것은 더 큰 인장 강도를 전달하고 이동 중에 손상될 가능성을 줄이는 것으로 생각됩니다. 게다가, 암컷은 수컷보다 날개 하중이 더 낮았는데, 이는 암컷이 날기 위해 더 적은 에너지를 필요로 한다는 것을 의미합니다.[51]

어른들은 성적으로 이형성입니다. 수컷은 암컷보다 약간 크고 뒷날개마다 정맥에 검은 점이 있습니다. 이 반점에는 많은 나비목들이 구애하는 동안 사용하는 페로몬을 생산하는 비늘이 포함되어 있습니다. 암컷은 수컷보다 더 어둡고 날개에 더 넓은 정맥을 가지고 있는 경우가 많습니다. 수컷과 암컷의 복부 끝은 모양이 다릅니다.[49][52][27][53][54][55]

성체의 가슴은 6개의 다리를 가지고 있지만, 모든 님팔리과와 마찬가지로 앞다리는 작고 몸에 붙박혀 있습니다. 나비는 걷고 매달릴 때 가운데와 뒷다리만 사용합니다.[56]

성체는 보통 번식기에 2-5주 정도 삽니다.[27]: 22–23 고밀도로 자라는 유충은 저밀도로 자라는 유충에 비해 더 작고 생존율이 낮으며 성충으로서 무게가 덜 나갑니다.[57]

비전.

생리학적 실험은 왕나비가 4색 체계를 통해 세상을 본다는 것을 암시합니다.[58] 인간과 마찬가지로 망막에는 서로 다른 파장의 빛을 흡수하는 서로 다른 광수용체 세포에서 발현되는 세 가지 유형의 옵신 단백질이 포함되어 있습니다. 인간과 달리 광수용체 세포의 한 종류는 자외선 범위의 파장에 해당하고, 다른 두 종류는 파란색과 초록색에 해당합니다.[59]

주 망막에 있는 이 세 가지 광수용체 세포 외에도 모나크 나비 눈에는 녹색을 흡수하는 옵신에 도달하는 빛을 여과하는 오렌지 여과 색소가 포함되어 있어 더 긴 파장의 빛에 민감한 네 번째 광수용체 세포를 만듭니다.[58] 여과된 녹색 옵신과 여과되지 않은 녹색 옵신의 조합은 나비가 노란색과 주황색을 구별할 수 있게 해줍니다.[58] 군주 눈의 등쪽 테두리 영역에서도 자외선 옵신 단백질이 검출되었습니다. 한 연구는 이것이 나비들이 긴 이동 비행을 위해 태양을 향하도록 자외선으로 편광된 하늘빛을 감지하는 능력을 가능하게 한다고 제안합니다.[60]

이 나비들은 강도에 근거하지 않고 파장에만 근거하여 색깔을 구별할 수 있습니다. 이 현상을 "진정한 색 시각"이라고 부릅니다. 이것은 영양분을 위해 꿀을 찾고, 짝을 고르고, 알을 낳을 우유풀을 찾는 것을 포함한 많은 나비 행동에 중요합니다. 한 연구에 따르면 꽃 색깔은 꽃 모양보다 꿀을 찾는 나비들이 멀리서 더 쉽게 알아볼 수 있다고 합니다. 이것은 꽃들이 식물 경관의 녹색 배경과 매우 대조적인 색상을 가지고 있기 때문일 수 있습니다.[61] 한편, 나비들이 그들의 알을 밀크위드 위에 확실히 낳을 수 있도록 산란을 위해서는 잎 모양이 중요합니다.

색에 대한 인식을 넘어 특정 색을 기억하는 능력은 왕나비의 삶에 필수적입니다. 이 곤충들은 색깔과 모양을 설탕이 든 음식 보상과 연관시키는 법을 쉽게 배울 수 있습니다. 꿀을 찾을 때, 색은 곤충의 관심을 잠재적인 먹이원으로 이끄는 첫 번째 신호이고, 모양은 과정을 촉진하는 2차적인 특성입니다. 알을 낳을 장소를 물색할 때는 색깔과 모양의 역할이 바뀝니다. 또한, 다른 종의 수컷 나비와 암컷 나비 사이에는 특정한 색깔을 배울 수 있는 능력에 있어서 차이가 있을 수 있지만, 왕나비의 경우에는 암수 사이에 차이가 나타나지 않습니다.[61]

구애와 짝짓기

군주의 구애는 두 단계로 이루어집니다. 공중 단계에서 수컷은 암컷을 뒤쫓고 종종 땅으로 강제로 옮깁니다. 지상 단계 동안, 나비들은 약 30분에서 60분 동안 번식하고 붙어 있습니다.[62] 짝짓기 시도의 30%만이 짝짓기로 끝나는데, 이는 암컷이 짝짓기를 피할 수 있을지도 모른다는 것을 암시하지만, 어떤 것은 다른 것들보다 더 많은 성공을 거두기도 합니다.[63][64] 교미하는 동안 수컷은 자신의 정자를 암컷에게 옮깁니다. 정자와 함께 정자는 암컷에게 알을 낳는 데 도움이 되는 영양을 제공합니다. 정자의 크기가 증가하면 암컷 군주의 번식력이 증가합니다. 더 큰 정자를 생산하는 수컷은 또한 더 많은 암컷의 난자를 수정시킵니다.[65]

암컷과 수컷은 보통 한 번 이상 짝짓기를 합니다. 여러 번 짝짓기를 하는 암컷들은 더 많은 알을 낳습니다.[66] 월동 개체군에 대한 짝짓기는 분산되기 전인 봄에 이루어집니다. 짝짓기는 페로몬 속의 다른 종보다 덜 의존적입니다.[67] 수컷의 탐색과 포획 전략은 교배 성공에 영향을 미칠 수 있으며, 서식지에 대한 인간의 유도된 변화는 월동 장소에서 군주 교배 활동에 영향을 미칠 수 있습니다.[68]

분포 및 서식지

D. p. plexippus의 서부 및 동부 개체군의 범위는 계절에 따라 확장 및 축소됩니다. 번식지, 이동 경로, 겨울 보금자리에 따라 범위가 다릅니다.[27]: 18 그러나 서부와 동부의 군주 개체군 사이에는 유전적 차이가 존재하지 않으며,[32] 생식 격리가 다른 종의 범위 내에 있기 때문에 이러한 개체군의 하위 종으로 이어지지는 않았습니다.[27]: 19

아메리카 대륙에서 군주는 캐나다 남부에서 남아메리카 북부에 이르기까지 다양합니다.[6] It is also found in Bermuda, the Cook Islands,[69] Hawaii,[70][71] Cuba,[72] and other Caribbean islands,[27]: 18 the Solomons, New Caledonia, New Zealand,[73] Papua New Guinea,[74] Australia, the Azores, the Canary Islands, Madeira, continental Portugal, Gibraltar,[75] the Philippines, and Morocco.[76] 그것은 영국에서 몇 년 동안 우연히 이주한 사람으로 나타납니다.[77]

D. plexippus의 월동 개체군은 멕시코, 캘리포니아, 미국 걸프 연안, 플로리다, 그리고 서식지가 생존에 필요한 특정 조건을 가지고 있는 애리조나에서 발견됩니다.[78][79] 미국 동부 해안에서, 그들은 버지니아 주 버지니아 비치의 라고 마까지 북쪽으로 월동했습니다.[80] 그들의 월동 서식지는 일반적으로 개울에 접근할 수 있고, 충분한 햇빛(날 수 있는 체온)과 적절한 보금자리 식물을 제공하며, 포식자로부터 상대적으로 자유롭습니다.

월동하는 나비들은 베이스우드, 느릅나무, 수막, 메뚜기, 오크, 오시지-오렌지, 멀베리, 피칸, 버드나무, 목화나무, 메스키트 등에서 볼 수 있습니다.[81] 번식하는 동안,[82] 왕의 서식지는 농경지, 목초지, 초원의 잔재, 도시와 교외의 주거 지역, 정원, 나무, 길가에서 발견됩니다.

유충숙주식물

군주 애벌레가 사용하는 기주식물은 다음과 같습니다.

- 애슬레피아상구스티폴리아 – 애리조나 밀크위드[83]

- 애스클레피아스 알비칸스 – 흰줄기밀크위드

- 애스클레피아 아스페룰라 - 영양 뿔 밀크위드[83]

- 애스클레피아스 캘리포니아 밀크위드[83]

- 애기장대 – 하트리프 밀크위드[83]

- 아클레피아스쿠라사비카

- 애스클레피아세리오카파 – 양털구슬 밀크위드[83]

- 사막밀크위드속[83] (Asclepiaserosa)

- 아스클레피아스 엑살타타 – 밀크위드를[83] 찌릅니다.

- 애스클레피아스 파시큘라리스 – 멕시코 통밀크위드[83]

- 애스클레피아스 휴미스트라타 – 샌드힐/소나무 밀크위드[83]

- 아스클레피아 인카나타 – 늪젖풀[84][85][86][87]

- 애스클레피아스리나리아 – 솔잎밀크위드

- 애스클레피아스니베아 – 카리브해산[88] 밀크위드

- 아스클레피아소노테로이드 – 지조테스 밀크위드[83]

- 아스클레피아스페레니스 – 수생 밀크위드[83]

- 아스클레피아스페리오사 – 우유풀을[83][89][90][91][92] 보여줍니다.

- 애스클레피아스 서브룰라타 – 러쉬 밀크위드[83]

- 애스클레피아스시리아카 – 흔한 밀크위드[93]

- 애기장대 - 나비잡초[83]

- 흰밀가루병[83] – 흰밀가루병

- 애스클레피아스베르티실라타 – 통밀크위드[83]

- 애스클레피아스베스티타 – 양털밀크위드[83]

- 애스클레피아스 비리디스 - 녹색 영양 뿔 밀크위드[83][94][95][96][97]

- 꽃받침 – 왕관꽃[98]

- 칼로트로피스속

- 시난쿰라베 – 모래덩굴 밀크위드[99]

- 흰덩굴속[70][100] (Sarcostemma clausa)

아스클레피아스 쿠라사비카, 즉 열대성 밀크위드는 종종 나비 정원에 관상용으로 심습니다. 미국의 연중 식재는 미국 걸프 해안을 따라 새로운 월동지가 생겨 연중 무휴로 이어지는 원인일 수도 있기 때문에 논란과 비판을 받고 있습니다.[101] 이것은 이동 패턴에 악영향을 미치고 위험한 기생충인 Ophryocystis electroscirha의 극적인 축적을 유발하는 것으로 생각됩니다.[102] 열대성 밀크위드에서 사육되는 모나크 유충이 철새 발육 감소(생식성 휴지기)를 보이며, 철새 성충이 열대성 밀크위드에 노출되면 생식 조직 성장을 자극한다는 새로운 연구 결과도 나왔습니다.[103]

성인식량원

유충은 밀크위드만 먹지만 성충은 다음과 같은 많은 식물의 꿀을 먹고 삽니다.[104]

- 아포시넘 칸나비눔 – 인도 대마

- 아스클레피아 종. – 밀크위드

- 심피오트리쿰 종 – 신대륙성자

- Cirsium sp. – 엉겅퀴

- 야생당근속 (Daucus carota)

- 디파쿠스 실베스트리스 – 티젤

- Echinacea sp. – 콘플라워

- 마초과 (Erigeron canadensis)

- 유파토리엄 마쿨라툼 – 얼룩무늬 조-파이 잡초

- 유파토리움 퍼폴리아툼 – 일반 뼈 세트

- 헤스페리스 마트로날리스 – 여성용 로켓

- 리아트리스 종 – 타오르는 별

- 메디카고사티바 – 알팔파

- 솔리다고 종 – 황금 막대

- 시링가 불가리스 – 라일락

- 삼엽충 프라텐스 – 붉은 클로버

- 키다리쇠풀속[79] (Vernonia altissima)

모나크는 축축한 흙과 젖은 자갈로부터 수분과 미네랄을 얻는데, 이것은 진흙을 퍼내는 행동이라고 알려져 있습니다. 군주는 또한 인도의 기름때가 묻은 채 웅크리고 있는 것이 목격되었습니다.[79]

비행과 이주

피에드라 헤라다

북미에서는, 군주들이 매년 남북으로 이주하면서, 위험이 가득한 장거리 여행을 합니다.[6] 이것은 다세대 이주이며 개별 군주는 전체 여정의 일부만 차지합니다.[105] 로키산맥 동쪽의 개체군은 멕시코 미초아칸주와 플로리다주 일부에 있는 마리포사 모나르카 생물권 보호구역의 보호구역으로 이주를 시도합니다. 서부의 개체수는 캘리포니아 중부와 남부의 다양한 해안 지역에서 월동하는 목적지에 도달하려고 노력합니다. 로키스 동부의 월동 인구는 봄의 이동 기간 동안 텍사스와 오클라호마까지 북쪽에 도달할 수 있습니다. 2, 3, 4세대는 봄에 미국과 캐나다의 북쪽 지역으로 돌아옵니다.[106]

포로로 사육된 군주는 야생 군주에 비해 이동 성공률이 훨씬 [107]낮지만 멕시코의 월동지로 이동할 수 있는 것으로 보입니다(아래의 포로 사육에 대한 섹션 참조).[108] 최근 애리조나에서 모나크 월동지가 발견되었습니다.[109] 미국 동부의 군주들은 일반적으로 미국 서부의 군주들보다 더 먼 거리를 이주합니다.[110]

1800년대부터 군주제는 전 세계에 퍼졌고, 현재 전 세계적으로 많은 비이주 인구가 있습니다.[111]

성인의 비행 속도는 약 9km/h(6mph)입니다.[112]

포식자와의 상호작용

애벌레와 나비 형태 모두에서, 군주들은 잠재적인 포식자들에게 그들의 바람직하지 않은 맛과 독이 있는 특성을 경고하기 위해 대조적인 색상의 밝은 표시로 포식자들을 물리칩니다. 한 군주 연구자는 군주는 먹이 사슬의 일부이므로 사람들이 군주의 포식자를 죽이기 위한 조치를 취하지 않아야 하기 때문에 알, 유충 또는 성충에 대한 포식은 자연스러운 것이라고 강조합니다.[113]

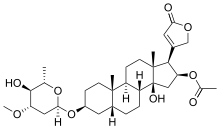

유충은 밀크위드만을 먹고 보호용 심장 글리코사이드를 섭취합니다. 아스클레피아스 종의 독소 수치는 다양합니다. 모든 군주들이 입맛에 맞지 않는 것은 아니지만, 베이츠적이거나 자동화된 것을 전시합니다. 심장 글리코사이드 수치는 복부와 날개에서 더 높습니다. 일부 포식자는 이러한 부분을 구별할 수 있고 가장 입맛에 맞는 부분을 소비합니다.[114]

나비 잡초(A. tuberosa)는 상당한 양의 심장 글리코사이드(cardenolides)가 부족하지만 대신 임신을 포함한 다른 유형의 독성 글리코사이드가 포함되어 있습니다.[115][116][117] 자연주의자와 다른 사람들이 군주 애벌레가 식물을 선호하지 않는다고 보고했기 때문에 이러한 차이는 유충이 그 밀크위드 종을 먹고 사는 군주의 독성을 감소시킬 수 있습니다.[118] 다른 우유 잡초들도 비슷한 특성을 가지고 있습니다.[119]

포식자의 종류

군주들은 다양한 천적들을 가지고 있지만, 이들 중 어느 것도 전체 개체수에 해를 끼치고 있다고 의심되거나 겨울 식민지 크기의 장기적인 감소의 원인은 아닙니다.

몇몇 종의 새들은 심장 글리코사이드(cardenolides)와 관련된 나쁜 영향을 겪지 않고 군주를 섭취할 수 있는 방법을 습득했습니다. 검은등 오리올은 맛으로 카데놀리드를 식별하고 거부하는 능력을 부여하는 섭식 행동의 포착을 통해 군주를 잡아먹을 수 있습니다.[120] 그러나 검은머리그로스비크는 2차 식물 독에 대한 무감각으로 인해 군주를 구토 없이 섭취할 수 있게 되었습니다.[121] 그 결과, 이 오리올과 그로스비크들은 주기적으로 몸에 높은 수준의 카르데놀라이드를 가지고 있으며, 그들은 군주 소비가 감소하는 기간에 갈 수 밖에 없습니다. 이 주기는 군주의 잠재적 포식을 효과적으로 50% 감소시키고 군주 아포세마티즘이 정당한 목적을 가지고 있음을 나타냅니다.[120] 검은머리그로스비크는 심장 독의 분자 표적인 나트륨 펌프에서도 내성 돌연변이를 진화시켰습니다. 그로스비크의 나트륨 펌프 유전자 4개 사본 중 하나에서 진화한 특정 돌연변이는 심장 글리코사이드에 저항하도록 진화한 일반 까마귀와 같은 다른 밀크위드 나비에서 발견된 돌연변이와 같습니다.[122] 다른 새 포식자로는 갈색 물총새, 그램클, 로빈스, 카디널스, 참새, 스크럽제이스, 피니언제이스 등이 있습니다.[114]

왕의 흰 형태는 1965년에서 1966년 사이에 두 개의 불새 종인 Pycnonotus cafer와 Pycnonotus jocosus가 도입된 후 오아후에서 나타났습니다. 이들은 현재 하와이에서 가장 흔한 조류 식충동물이며, 아마도 군주만큼 큰 곤충을 먹는 유일한 동물일 것입니다. 하와이 군주들은 심장 글리코사이드 수치가 낮지만, 새들은 또한 그 독소에 내성이 있을 수 있습니다. 이 두 종은 밀크위드 덤불의 가지와 잎 밑에서 유충과 일부 번데기를 사냥합니다. 벌새는 또한 휴식을 취하고 산란하는 성충을 먹지만 날지는 않습니다. 색깔 때문에 흰색 형태가 주황색보다 생존율이 높습니다. 이것은 배교적인 선택 때문에(즉, 새들은 오렌지색 군주들이 먹을 수 있다는 것을 배웠다), 위장 때문에(흰색 형태는 우유풀의 흰 사춘기 또는 잎을 통해 빛나는 빛의 조각과 일치한다), 또는 흰 형태가 새의 전형적인 군주의 탐색 이미지와 맞지 않기 때문에, 따라서 피하게 됩니다.[123]

일부 쥐, 특히 검은귀쥐(Peromyscus melanotis)는 모든 설치류와 마찬가지로 많은 양의 카르데놀리드를 견딜 수 있고 군주를 먹을 수 있습니다.[124] 월동하는 성충은 시간이 지남에 따라 독성이 약해져 포식자에게 더 취약해집니다. 멕시코에서는 월동하는 군주의 약 14%가 새와 쥐에게 먹히고 검은귀쥐는 하룻밤에 최대 40마리의 군주를 먹을 수 있습니다.[78][124]

북미에서는 왕의 알과 1령 유충을 도입한 아시아 무당벌레(Harmonia axyridis)의 유충과 성충이 잡아 먹습니다.[125] 중국사마귀(Tenodera sinensis)는 내장을 제거하면 유충을 먹어 치우고 카데놀리드를 피합니다.[126] 포식성 말벌은 일반적으로 유충을 섭취하지만,[127] 큰 유충은 식물에서 떨어지거나 몸을 홱 움직이는 것으로 말벌의 포식을 피할 수 있습니다.[128]

포세마티즘

모나크는 몸속에 있는 카르데놀리드가 존재하기 때문에 독성이 있고 악취가 납니다. 이는 애벌레가 우유풀을 먹고 살 때 섭취하는 것입니다.[67] 모나크 및 기타 카르데놀라이드 내성 곤충은 내성이 없는 종보다 상당히 높은 농도의 카르데놀라이드를 견디기 위해 Na+/K+-ATPase 효소의 내성 형태에 의존합니다.[129] 주로 밀크위드인 아스클레피아 속의 많은 식물을 섭취함으로써 군주 애벌레는 디기탈리스와 유사한 심장 정지 방식으로 작용하는 스테로이드인 심장 글리코사이드, 더 구체적으로는 카르데놀리드를 격리할 수 있습니다.[130] 모나크는 함량이 높거나 낮은 식물보다 중간 카르데놀라이드 함량의 식물에서 카르데놀라이드를 가장 효과적으로 분리할 수 있는 것으로 밝혀졌습니다.[131] 군주의 Na+/K+-ATPase에서 진화한 세 가지 돌연변이는 식이 심장 글리코사이드에 대한 내성을 부여하기에 충분하다는 것이 밝혀졌습니다.[129] 이것은 CRISPR-Cas9 유전체 편집을 사용하여 초파리 초파리에서 이러한 돌연변이를 동일한 유전자로 교환하여 테스트했습니다. 이 초파리에서 변신한 왕파리들은[132] 아포키나과에서 발견되는 심장 글리코사이드인 식이성 우아베인에 완전히 내성이 있었고, 왕파리처럼 변형을 통해 일부를 격리시키기도 했습니다.[129]

밀크위드의 종에 따라 기생충의 성장, 독성 및 전파에 다른 영향을 미칩니다.[133] Asclepias curassavica라는 한 종은 OE(Ophryocystis electrocirha) 감염의 증상을 감소시키는 것으로 보입니다. 이에 대한 두 가지 가능한 설명은 전반적인 군주 건강을 촉진하여 군주의 면역 체계를 강화하거나 식물의 화학 물질이 OE 기생충에 직접적인 부정적인 영향을 미친다는 것입니다.[133] A. curassavica는 OE 감염을 치료하거나 예방하지 않습니다. 감염된 군주가 더 오래 살 수 있도록 할 뿐이며, 이렇게 하면 감염된 군주가 OE 포자를 더 오랫동안 퍼뜨릴 수 있습니다. 평균 가정용 나비 정원의 경우 이 시나리오는 지역 인구에 더 많은 OE를 추가할 뿐입니다.[134]

애벌레가 나비가 된 후, 독소는 몸의 다른 부분으로 이동합니다. 많은 새들이 나비의 날개를 공격하기 때문에, 날개에 있는 심장 글리코사이드의 3배를 가지고 있는 것은 포식자들에게 매우 불쾌한 맛을 남기고 그들이 나비의 몸을 섭취하는 것을 막을지도 모릅니다.[130] 오직 복부를 섭취하기 위해 날개를 제거하는 포식자들과 싸우기 위해, 군주들은 가장 강력한 심장 글리코사이드를 복부에 보관합니다.[135]

모방

모나크들은 아마도 가장 잘 알려진 모방의 예 중 하나인 비슷한 모습의 왕나비와 유해한 맛의 방어를 공유합니다. 오랫동안 베이테우스 흉내의 예라고 알려져 왔지만, 총독은 사실 군주보다 더 불쾌하기 때문에 이것을 뮐러 흉내의 예로 만들었습니다.[136]

인간 상호작용

군주는 알라바마주,[137] 아이다호주,[138][139] 일리노이주,[140] [141]미네소타주, 텍사스주, 버몬트주,[142] 웨스트버지니아주의 주 곤충입니다.[143] 미국의 국가 곤충으로 만들기 위한 법안이 [144]발의되었지만 1989년과[145] 1991년에 다시 실패했습니다.[146]

집 주인들은 점점 더 나비 정원을 만들고 있습니다; 군주들은 특정한 밀크위드 종과 꿀 식물로 나비 정원을 가꾸어 끌어들일 수 있습니다. 이 군주의 웨이 스테이션을 설립하기 위한 노력이 진행 중입니다.

IMAX 영화 나비의 비행은 당시 알려지지 않은 군주가 멕시코 월동 지역으로 이주한 것을 기록하기 위해 우르쿠하츠, 브뤼거, 트레일의 이야기를 묘사합니다.[148]

서식지 파괴를 제한하기 위해 멕시코와 캘리포니아의 월동 장소에 보호구역과 보호구역이 만들어졌습니다. 이러한 사이트는 상당한 관광 수익을 창출할 수 있습니다.[149] 하지만, 관광이 줄어들면, 왕나비는 더 많은 단백질 함량과 더 높은 가치의 면역 반응과 산화 방어를 보여주기 때문에 더 높은 생존율을 가질 것입니다.[150]

조직과 개인은 태그 지정 프로그램에 참여합니다. 태깅 정보는 마이그레이션 패턴을 연구하는 데 사용됩니다.[151]

2012년에 발표된 바바라 킹솔버의 소설, 비행행동은 애팔래치아에서 많은 인구가 나타나는 허구적인 모습을 다루고 있습니다.[152]

종육

사람들은 감금된 상태에서 그들을 기를 때 군주들과 상호작용을 하는데, 이것은 점점 더 인기를 얻고 있습니다. 그러나 이 논란의 여지가 있는 활동에는 위험이 발생합니다. 한편으로, 포로 양육은 많은 긍정적인 측면을 가지고 있습니다. 모나크는 학교에서 사육되며 호스피스, 추모 행사 및 결혼식에서 나비 방출에 사용됩니다.[153] 9.11 공격에 대한 추모식에는 포로로 잡힌 군주들의 석방이 포함됩니다.[154][155][156] 모나크는 교육 목적으로 학교와 자연 센터에서 사용됩니다.[157] 많은 주택 소유자들은 취미와 교육 목적으로 사육 중인 군주를 기릅니다.[158]

한편, 군주들이 "대량으로 양육"될 때 이러한 관행은 문제가 됩니다. 2015년 허핑턴 포스트와 2016년 디스커버 잡지의 기사들은 이 문제를 둘러싼 논란을 정리했습니다.[159][160]

군주의 쇠퇴에 대한 빈번한 언론 보도는 많은 주택 소유주들이 "군주 인구를 늘리기 위한" 노력으로 가능한 한 많은 군주들을 집에서 양육하고 야생에 풀어주려는 시도를 하게 만들었습니다. 아이오와주 린 카운티의 한 사람과 같은 몇몇 사람들은 동시에 수천 마리의 군주들을 길렀습니다.[161]

일부 군주 과학자들은 유전적 문제와 질병 확산의 위험 때문에 야생에 풀어주기 위해 사육되는 많은 수의 군주들을 사육하는 관행을 용납하지 않습니다.[162] 대량 사육의 가장 큰 우려 중 하나는 왕기생충인 Ophryocystis electroscirha를 야생으로 퍼뜨릴 가능성입니다. 이 기생충은 포로가 된 군주들, 특히 그들이 함께 수용될 경우 빠르게 축적될 수 있습니다. 기생충의 포자는 또한 모든 하우징 장비를 빠르게 오염시킬 수 있으므로 동일한 용기에서 사육된 모든 후속 군주가 감염됩니다. 한 연구원은 100마리 이상의 군주를 기르는 것은 "대량 양육"에 해당하므로 해서는 안 된다고 말했습니다.[163]

질병 위험 외에도, 연구원들은 이 포획된 군주들이 사육되는 부자연스러운 조건 때문에 야생 군주들만큼 건강하지 않다고 믿고 있습니다. 주택 소유자는 종종 부엌, 지하실, 현관 등의 플라스틱 또는 유리 용기와 인공 조명 및 제어된 온도에서 군주를 기릅니다. 그러한 조건들은 군주들이 야생에서 익숙한 것을 모방하지 않을 것이고, 그들의 야생적인 존재의 현실에 적합하지 않은 어른들을 초래할 수도 있습니다. 이를 뒷받침하기 위해, 한 시민 과학자의 최근 연구는 포획된 군주들이 야생 군주들보다 이주 성공률이 낮다는 것을 발견했습니다.[108]

2019년 연구는 항해 능력을 평가하는 묶은 비행 장치에서 사육 및 야생 군주를 테스트함으로써 포획된 군주의 적합성을 조명했습니다.[164] 그 연구에서 인공적인 조건에서 성인이 될 때까지 길러진 군주들은 항해 능력이 감소하는 것으로 나타났습니다. 며칠 동안 야생에서 사육된 군주들에게도 이런 일이 일어났습니다. 몇몇 포로로 길러진 군주들은 적절한 항해를 보여주었습니다. 이 연구는 군주의 발전이 취약하다는 것을 드러냈고, 여건이 맞지 않을 경우 그들의 적절한 이주 능력이 약화될 수 있다는 것을 보여주었습니다. 같은 연구에서 나비 사육사로부터 구입한 사육 군주 모음의 유전자를 조사한 결과, 야생 군주와 너무도 다른 것으로 밝혀져 주 저자가 "프랑켄 군주"라고 표현할 정도였습니다.[165]

2019년에 발표되지 않은 연구는 포획된 사육된 야생 군주 유충과 비교했습니다.[166] 연구 결과 사육된 유충이 야생 유충보다 방어적인 행동을 더 많이 보이는 것으로 나타났습니다. 그 이유는 알려지지 않았지만 사육된 유충을 자주 다루거나 방해한다는 사실과 관련이 있을 수 있습니다.

위협

2015년 2월, 미국 어류 및 야생동물국은 1990년 이후 거의 10억 마리에 달하는 군주들이 나비의 월동지에서 사라졌다는 연구 결과를 보고했습니다. 이 기관은 군주의 쇠퇴를 부분적으로 농부들과 집주인들이 사용해왔던 제초제로 인한 밀크위드의 손실 때문이라고 설명했습니다.[167]

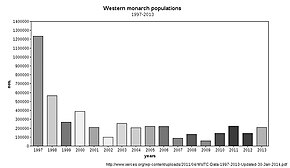

서양의 군주 인구

2014년 20년간의 비교에 따르면 로키산맥 서쪽의 월동 수는 1997년 이후 50% 이상 감소했고 로키산맥 동쪽의 월동 수는 1995년 이후 90% 이상 감소했습니다. 제르세스 협회에 따르면, 캘리포니아의 군주 인구는 2018년에 수백만 마리의 나비에서 수만 마리의 나비로 86% 감소했습니다.[168]

학회의 연간 2020-2021년 겨울 수는 캘리포니아 개체수의 현저한 감소를 보여주었습니다. 한 퍼시픽 그로브 지역에는 단 한 마리의 모나크 나비도 없었습니다. 이에 대한 일차적인 설명은 나비의 밀크위드 서식지 파괴였습니다.[27][169] 이 특정 인구는 2022년[update] 현재 2000명 미만으로 추정됩니다.[170]

동부와 중서부의 군주 인구

2016년 출판물은 지난 10년 동안 동부 군주 개체군의 월동 개체수가 90% 감소한 것은 번식 서식지와 밀크위드의 손실 때문이라고 설명했습니다. 그 출판물의 저자들은 이 개체군이 향후 20년 동안 거의 멸종될 확률이 11%에서 57%라고 말했습니다.[171]

캔자스 대학의 모나크 워치의 책임자인 칩 테일러는 1억 2천만에서 1억 5천만 에이커가 사라진 중서부의 밀크위드 서식지가 "사실상 사라졌다"고 말했습니다.[172][173] 이 문제를 해결하기 위해 모나크 워치는 "모나크 웨이스테이션"의 설치를 권장합니다.[158]

제초제 사용 및 유전자 변형 작물로 인한 서식지 손실

1999년과 2010년 사이에 밀크위드의 존재비와 군주 개체수의 감소는 현재 미국에서 이들 작물의 각각 89%와 94%를 구성하는 제초제 내성 유전자 변형(GM) 옥수수와 대두의 채택과 관련이 있습니다. GM 옥수수와 대두는 제초제 글리포세이트의 효과에 내성이 있습니다.[171] 일부 환경보호론자들은 밀크위드의 소멸을 중서부의 농업 관행 때문으로 돌립니다. GM 종자는 농부들이 그들의 식량 작물 줄 근처에서 자라는 원치 않는 식물을 죽이는 데 사용되는 제초제에 저항하기 위해 사육됩니다.[174][175]

2015년 천연자원국방위원회는 미국 환경보호청(EPA)을 상대로 소송을 제기했습니다. 의회는 군주들의 글리포세이트 사용의 위험성에 대한 경고를 무시했다고 주장했습니다.[176] 그러나, 2018년 연구에 따르면, 밀크위드의 감소는 GM 작물이 도착하기 전에 나타난다고 합니다.[177]

마이그레이션 중 손실

동부와 중서부의 군주들은 분명히 멕시코에 도달하는 데 문제를 겪고 있습니다. 많은 군주 연구자들은 지난 20년 동안 번식(성체) 군주의 수가 감소하지 않았다는 것을 보여주는 장기 시민 과학 데이터에서 얻은 최근 증거를 인용했습니다.[178][179][180]

번식과 이동하는 군주의 수가 장기적으로 감소하지는 않지만 월동하는 군주의 수는 분명히 감소한다는 것은 이러한 생활 단계 사이에 점점 더 단절되고 있음을 시사합니다. 한 연구원은 자동차 충돌로 인한 사망률이 이동하는 군주들에게 증가하는 위협이 된다고 제안했습니다.[181] 2019년에 발표된 멕시코 북부의 도로 사망률에 대한 연구는 매년 단 두 개의 "핫스팟"에서 매우 높은 사망률을 보여주었고, 이는 200,000명의 군주가 사망한 것에 해당합니다.[182]

월동 서식지 손실

이 기사의 일부(이 섹션과 관련된 부분)를 업데이트해야 합니다. (2021년 8월) |

동부와 중서부의 군주들이 이주해 오는 멕시코 숲의 면적은 2013년 20년 만에 최저치를 기록했습니다. 감소는 2013-2014 시즌 동안 증가할 것으로 예상되었습니다. 멕시코 환경 당국은 오야멜 나무의 불법 벌목을 계속 감시하고 있습니다. 오야멜(Oyamel)은 월동하는 나비들이 겨울 휴면 기간 동안 상당한 시간을 보내거나 발달이 중단되는 상록수의 주요 종입니다.[183]

2014년의 한 연구는 "월동 서식지의 보호는 의심할 여지 없이 북미 동부 전역에서 번식하는 군주를 보존하는 데 큰 도움이 되었다"고 인정했지만, 그들의 연구는 미국의 번식지의 서식지 감소가 최근과 예상되는 개체수 감소의 주요 원인임을 보여줍니다.[184]

서부 군주 인구는 2014년 이후 약간 반등하여 2022년 서부 군주 추수 감사절 집계에서 335,479명의 군주를 기록했습니다. 인구는 여전히 완전한 회복을 위해 가야 할 것이 많습니다.

기생충

기생충에는 타키니드 파리 Sturmia convergens와[186] Lespesia archipivora가 있습니다. 레스페리아 기생 나비 유충은 일시 중단되지만 번데기 전에 죽습니다. 파리의 구더기는 땅에 내려 갈색 번데기를 형성한 다음 성충으로 나타납니다.[187]

프테로말루스 말벌, 특히 프테로말루스 카소티스는 군주 번데기에 기생합니다.[188] 이 말벌들은 번데기가 여전히 부드럽지만 번데기에 알을 낳습니다. 14-20일 후에 최대 400마리의 성충이 번데기에서 [188]나와 군주를 죽입니다.

박테리아 Micrococcus flasidifex danai도 유충을 감염시킵니다. 번데기 직전에 유충은 수평면으로 이동하여 몇 시간 후에 죽는데, 가슴과 복부가 절뚝거리며 한 쌍의 앞다리만 붙어 있습니다. 그 직후 몸은 검게 변합니다. 녹농균은 침입력은 없지만 약해진 곤충에게 2차 감염을 일으킵니다. 그것은 실험실에서 기르는 곤충들의 흔한 죽음의 원인입니다.[187]

Ophryocystis electroscirha는 군주의 또 다른 기생충입니다. 피하 조직을 감염시키고 번데기 단계에서 형성된 포자에 의해 전파됩니다. 이 포자는 감염된 나비의 몸 전체에서 발견되며, 복부에 가장 많은 수가 있습니다. 이 포자는 암컷에서 애벌레로 전달되는데, 포자는 알을 낳는 동안 문질러지고 애벌레에 의해 섭취됩니다. 중증 감염자는 몸이 약하거나 날개를 펴지 못하거나 몸을 가누지 못하고 수명도 짧지만 기생충 수치는 개체수에 따라 다릅니다. 몇 세대가 지나면 모든 개체가 감염될 수 있는 실험실 사육에서는 그렇지 않습니다.[189]

O.elektroscirrha에 감염되면 도태라고 알려진 효과가 발생하여 감염된 이동하는 군주가 이동을 완료할 가능성이 낮아집니다. 이로 인해 기생충 부하가 낮은 월동 개체군이 발생합니다.[190] 상업적인 나비 번식 사업의 주인들은 비록 이 주장이 군주들을 연구하는 많은 과학자들에 의해 의심을 받지만,[191] 그들이 그들의 관행에서 이 기생충을 통제하기 위한 조치를 취한다고 주장합니다.[192]

숙주식물의 혼란

검은제비풀(Cynanchum louiseae)과 옅은제비풀(Cynanchum lossicum)은 북아메리카의 군주들에게 문제가 됩니다. 모나크들은 그들이 밀크위드와 비슷한 자극을 만들기 때문에 토종 덩굴성 밀크위드 (Cynanchum lave)의 이 친척들에게 알을 낳습니다. 일단 알이 부화하면, 애벌레는 유럽에서 온 이 침입성 식물의 독성에 의해 독살됩니다.[193]

기후.

가을과 여름의 기후 변화는 나비 번식에 영향을 미칩니다. 강우량과 결빙 온도는 밀크위드 성장에 영향을 미칩니다. WWF-멕시코 국장 오마르 비달(Omar Vidal)은 "군주의 수명은 번식하는 장소의 기후 조건에 달려 있습니다. 알, 유충, 번데기는 더 온화한 조건에서 더 빨리 발달합니다. 35 °C (95 °F) 이상의 온도는 유충에게 치명적일 수 있고, 덥고 건조한 조건에서 알이 말라버려서 부화율이 급격히 감소합니다."[194] 군주의 체온이 30°C(86°F) 이하이면, 군주는 날 수 없습니다. 몸을 녹이기 위해, 그들은 햇빛에 앉아 있거나 빠르게 날개를 떨며 몸을 녹입니다.[195]

기후 변화는 군주의 이주에 극적인 영향을 미칠 수 있습니다. 2015년의 한 연구는 온난화 온도가 군주의 번식 범위에 미치는 영향을 조사했고, 다음 50년 안에 군주 숙주 식물이 캐나다 북쪽으로 범위를 더 확장할 것이며, 군주들이 이를 따를 것이라는 것을 보여주었습니다.[196] 이를 통해 군주의 번식지가 확대되는 반면, 군주가 멕시코에서 월동지에 도달하기 위해 이동해야 하는 거리가 증가하는 효과도 얻을 수 있으며, 이는 이주 기간 동안 더 큰 사망률을 초래할 수 있습니다.[197]

높아진 온도에서 자란 우유 잡초는 더 높은 카르데놀라이드 농도를 함유하고 있는 것으로 나타났으며, 이 잎들은 군주 애벌레에게 너무 독성이 있습니다. 그러나 이러한 증가된 농도는 곤충 초식동물의 증가에 대한 반응일 가능성이 있으며, 이 또한 온도 증가에 의해 발생합니다. 다른 요인들이 없을 때 상승된 온도가 왕나비 애벌레들에게 우유풀을 너무 유독하게 만드는지는 알려져 있지 않습니다.[198] 또한, 백만 분의 760 부분의 이산화탄소 수준에서 자란 밀크위드는 다른 조합의 독성 카르데놀리드를 생산하는 것으로 밝혀졌는데, 그 중 하나는 군주 기생충에 대한 효과가 적었습니다.[199]

보존상태

2022년 7월 20일, 국제 자연 보전 연맹은 철새 왕나비를 멸종 위기 종의 적색 목록에 추가했습니다.[200][2]

모나크 나비는 현재 멸종위기 야생동식물종 국제거래협약에 등재되어 있지 않거나 미국 국내법에 따라 특별히 보호되고 있습니다.[201]

2014년 8월 14일, 생물다양성센터와 식품안전센터는 겨울을 나는 장소에서 관찰되는 장기적인 경향에 근거하여,[27] 군주와 그 서식지에 대한 멸종위기종 보호를 요청하는 법적 청원서를 제출했습니다. 미국 어류 및 야생 동물국(FWS)은 2015년 3월 3일까지 정보 제출 기한을 두고 멸종 위기 종법에 따라 모나크 나비에 대한 상태 검토를 시작했으며, 이후 2020년까지 연장되었습니다. 2020년 12월 15일, FWS는 나비를 멸종위기와 멸종위기에 처한 종 목록에 추가하는 것은 "당연하지만 배제되었다"고 판결했습니다. 왜냐하면 161개의 우선순위가 높은 종에 그들의 자원을 바칠 필요가 있었기 때문입니다.[202]

멕시코에서 겨울을 나는 군주의 수는 장기적으로 감소 추세를 보였습니다. 1995년 이래로, 1996-1997년 겨울 동안 커버리지 수는 18 헥타르(44 에이커)에 달했지만, 평균적으로 약 6 헥타르(15 에이커)에 달했습니다. 적용 범위는 2013-2014년 겨울 동안 최저점(0.67 헥타르(1.66 에이커)까지 감소했지만 2015-2016년에는 4.01 헥타르(10 에이커)로 반등했습니다. 2016년 군주의 평균 인구는 2억 명으로 추산되었습니다. 역사적으로, 평균적으로 3억 명의 군주들이 있습니다. 2016년의 증가는 2015년 여름의 양호한 번식 조건 때문이었습니다. 그러나 2016-2017년 겨울 동안 2.91 헥타르(7.19 에이커)로 27% 감소했습니다. 일부 사람들은 이것이 군주들의 이전 월동 시즌인 2016년 3월에 발생한 폭풍 때문이라고 믿고 있지만,[203][204][205] 대부분의 현재 연구에서 월동 군체의 크기가 다음 여름 번식 개체의 크기를 예측하지 못한다는 것을 보여주기 때문에 가능성은 낮아 보입니다.[206]

캐나다 온타리오 주에서, 모나크 나비는 특별한 관심의 종으로 목록에 올라 있습니다.[207] 2016년 가을, 캐나다의 멸종 위기 야생 동물 지위 위원회는 군주가 현재 캐나다에서 "관심 종"으로 등재되는 것과 대조적으로 캐나다에서 멸종 위기 종으로 등재될 것을 제안했습니다. 이 조치는 일단 제정되면 온타리오 남부의 주요 가을 축적 지역과 같은 캐나다의 중요한 군주 서식지를 보호할 것이지만, 군주와 함께 일하는 시민 과학자들과 교실 활동에도 영향을 미칠 것입니다. 군주가 캐나다에서 연방정부의 보호를 받는다면, 이러한 활동은 제한적이거나 연방정부의 허가를 필요로 할 수 있습니다.[208]

노바스코샤에서 군주는 2017년[update] 현재 주 차원에서 멸종 위기 동물로 지정되어 있습니다. 온타리오 주의 결정뿐만 아니라 이 결정은 멕시코의 월동 군체 감소가 캐나다의 번식 범위 감소를 초래한다는 가정에 근거한 것으로 보입니다.[209] 최근 두 개의 연구가 나비 아틀라스 기록이나[210] 시민 과학 나비 조사를 사용하여 캐나다의 군주 풍부도의 장기적인 추세를 조사했으며 [211]캐나다의 개체수 감소의 증거는 보여주지 않았습니다.

보존 노력

비록 북아메리카 동부의 번식 군주의 수는 분명히 줄어들지 않았지만, 겨울을 나는 나비의 수가 감소하고 있다는 보고가 그 종을 보존하려는 노력에 영감을 주었습니다.[178][179][180]

연방정부의 조치

2014년 6월 20일, 버락 오바마 대통령은 "꿀벌과 다른 꽃가루 매개자들의 건강을 증진시키기 위한 연방 전략 만들기"라는 제목의 대통령 각서를 발표했습니다. 이 각서는 농업부 장관과 환경보호청 관리자가 공동으로 위원장을 맡는 꽃가루 매개자 건강대책위원회를 설립하고 다음과 같이 밝혔습니다.

모나크 나비의 이동 개체수는 2013-14년에 기록된 가장 낮은 개체수 수준으로 감소했고, 이동 실패의 위험이 임박했습니다.[212]

2015년 5월, 꽃가루 매개자 건강 대책 위원회는 "꿀벌 및 기타 꽃가루 매개자의 건강 증진을 위한 국가 전략"을 발표했습니다. 이 전략은 세 가지 목표를 달성하기 위한 연방 정부의 조치를 제시했는데, 그 중 두 가지는 다음과 같습니다.

- 모나크 나비: 2020년까지 국내/국제적인 행동과 민관 협력을 통해 멕시코의 월동지에 약 15 에이커(6 헥타르)의 면적을 차지하는 왕나비의 동부 개체수를 2억 2,500만 마리로 늘립니다.

- 꽃가루 매개자 서식지 면적: 연방정부의 조치와 공공/민간 파트너십을 통해 향후 5년간 700만 에이커의 토지를 꽃가루 매개자를 위해 복원 또는 개선합니다.[213]

국가 전략이 확인한 우선 사업의 대부분은 텍사스에서 미네소타까지 1,500마일(2,400km)에 이르는 I-35 회랑에 초점을 맞췄습니다. 그 고속도로가 지나가는 지역은 미국의 주요 군주 이주 회랑에 봄과 여름 번식 서식지를 제공합니다.[213]

미국 일반 서비스청(GSA)은 조경 성능 요구 사항 세트를 P100 문서에 게시하고 있으며, 이 문서는 GSA의 공공 건물 서비스에 대한 표준을 의무화하고 있습니다. 2015년 3월부터 이러한 성능 요구 사항 및 업데이트에는 대상 수분 매개체에게 적절한 현장 채집 기회를 제공하기 위한 식재 설계의 4가지 주요 측면이 포함되었습니다. 대상 수분 매개체에는 꿀벌, 나비 및 기타 유익한 곤충이 포함됩니다.[214][215][216]

2015년 12월 4일, 오바마 대통령은 FAST(Fixing America's Surface Transport) 법안(Public. L. 114-94)에 서명했습니다.[217] FAST Act는 꽃가루 매개자를 지원하기 위한 노력에 새로운 중점을 두었습니다. 이를 위해 FAST Act는 미국 법전 Title 23(고속도로)를 개정했습니다. 이 개정안은 미국 교통부 장관이 그러한 제목의 프로그램을 자발적인 주들과 연계하여 수행할 때 다음과 같이 지시했습니다.

- 잔디 깎기를 포함한 도로변 및 기타 교통권의 통합적인 식생 관리 관행을 장려합니다.

- 나비의 이동 통로 역할을 하고 다른 수분 매개체의 이동을 촉진할 수 있는 비침습적인 토종 밀크위드 종을 포함하여 토종 포브와 풀의 식재를 통해 모나크 나비, 다른 토종 수분 매개체 및 꿀벌의 서식지 및 마초 개발을 장려합니다.[218]

FAST Act는 또한 Title 23에 따라 자금이 지원되는 운송 프로젝트와 관련하여 꽃가루 매개자 서식지, 마초 및 이동 경로 스테이션을 설립하고 개선하는 활동이 연방 자금 지원 대상이 될 수 있다고 언급했습니다.[218]

미국 농무부의 농업서비스국은 야생동물 보호구역 프로그램의 야생동물 보호를 위한 주 에이커 계획(SAFE)을 통해 왕나비와 다른 꽃가루 매개자들의 미국 개체수 증가를 돕고 있습니다. SAFE 이니셔티브는 농업 생산에서 환경에 민감한 토지를 제거하는 데 동의하고 환경 건강과 품질을 향상시킬 수 있는 종을 심는 농부들에게 연간 임대료를 제공합니다. 무엇보다도, 이 계획은 FWS가 위협받거나 멸종 위기에 처했다고 지정한 종들의 서식지를 만들기 위해 습지, 풀, 나무를 설립하도록 토지 소유자들을 독려합니다.[219][220][221][222]

기타행위

농업 회사들과 다른 단체들은 군주들이 번식할 수 있도록 살포되지 않은 지역들을 따로 남겨둘 것을 요청 받고 있습니다. 또한 전력선과 도로가 포함된 회랑을 따라 수분매개자 서식지를 구축하고 유지하는 데 도움이 되는 국가 및 지역 이니셔티브가 진행 중입니다. 연방 고속도로청, 주 정부 및 지방 관할 구역은 고속도로 부서 및 기타 부서에 제초제 사용을 제한하고, 잔디 깎기를 줄이고, 밀크위드가 자라는 것을 돕고, 군주들이 그들의 통행권 내에서 번식하도록 장려하고 있습니다.[175][223]

전국협력도로연구계획 보고서

2020년 교통연구위원회의 전국 협력 고속도로 연구 프로그램(NCRHP)은 왕나비의 서식지를 제공하기 위한 도로 회랑의 잠재력을 조사한 프로젝트를 설명하는 208페이지의 보고서를 발표했습니다. 프로젝트의 일부는 도로 관리자들이 도로 통행권에서 왕나비의 잠재적 서식지를 최적화하기 위한 도구를 개발했습니다.[224][225]

그러한 노력은 도로 근처의 나비 폐사 위험이 높기 때문에 논란이 되고 있습니다. 몇몇 연구는 자동차가 매년 수백만 마리의 군주와 다른 나비들을 죽인다는 것을 보여주었습니다.[181] 또한, 몇몇 증거들은 도로 근처에 사는 군주 유충이 생리적인 스트레스 상태를 경험한다는 것을 보여주는데, 이는 그들의 심박수의 상승에 의해 증명됩니다.[226]

NCRHP 보고서는 도로가 다른 위험 중에서도 군주들에게 교통 충돌의 위험을 제공한다는 사실을 인정하면서, 이러한 영향은 이주 중에 특정 깔때기 지역에 더 집중되는 것으로 보인다고 말했습니다.[227] 그럼에도 불구하고 보고서는 다음과 같이 결론지었습니다.

요약하면, 군주와 다른 꽃가루 매개자들에게 도로 회랑을 따라 위협이 존재하지만, 지속 가능한 개체군의 회복에 필요한 서식지의 양의 맥락에서 도로변은 매우 중요합니다.[227]

나비정원 가꾸기

이 주제에 대한 과학적인 연구들이 보고된 반면, 나비 정원 가꾸기와 "모나크 웨이 스테이션"을 만드는 관행은 일반적으로 나비의 개체수를 증가시키는 것으로 생각됩니다.[228][229][230][231][232][233][234] 나비 정원과 모나크 웨이 스테이션을 설립하여 감소하는 모나크 개체군을 복원하려는 노력은 나비의 먹이 선호도와 개체군 주기, 그리고 밀크위드를 전파하고 유지하는 데 필요한 조건에 특히 주의를 기울여야 합니다.[235][236]

예를 들어, 워싱턴 DC, 지역과 미국 북동부와 중서부의 다른 곳에서, 흔한 밀크위드(Asclepias syriaca)는 특히 나뭇잎이 부드럽고 [237]신선할 때 군주 애벌레에게 가장 중요한 먹이 식물 중 하나입니다. 왕겨 잎이 오래되고 질긴 늦여름에 왕겨 번식이 최고조에 달하기 때문에 A. syriaca는 왕겨 번식이 정점에 도달하면 빠르게 다시 성장할 것을 보장하기 위해 6월부터 8월까지 깎거나 줄여야 합니다. 미시간의 화려한 우유풀(A. speciosa)과 남부 대평원과 미국 서부에서 자라는 녹색 영양 뿔 우유풀(A. viridis)에도 유사한 조건이 존재합니다.[83][238][239][240][241][242] 게다가, A. syriaca와 다른 우유 잡초의 씨앗은 발아하기 전에 저온 처리(냉간 성층화) 기간이 필요합니다.[243][244][245][246][247][248]

폭우와 씨앗을 먹는 새들로부터 씨앗이 씻겨나가는 것을 보호하기 위해, 가벼운 천이나 0.5인치(13mm)의 짚 뿌리 덮개로 씨앗을 덮을 수 있습니다.[249][250] 그러나 뿌리 덮개는 절연체 역할을 합니다. 더 두꺼운 덮개 층은 겨울이 끝날 때 토양 온도가 충분히 올라가는 것을 방지한다면 씨앗이 발아하는 것을 방지할 수 있습니다. 또한 두꺼운 덮개 층을 통과할 수 있는 묘목은 거의 없습니다.[251]

군주 애벌레는 나비 정원에서 나비 잡초(A. tuberosa)를 먹고 살지만 일반적으로 종에 많이 사용되는 기주 식물은 아닙니다.[252] 이 식물은 거친 잎과 한 층의 트리홈을 가지고 있는데, 이것은 산란을 억제하거나 암컷의 잎 화학물질 감지 능력을 감소시킬 수 있습니다.[253][254] 식물의 낮은 수준의 카르데놀라이드는 또한 모나크가 식물에 알을 낳는 것을 방해할 수도 있습니다.[255][256] A. tuberosa의 알록달록한 꽃들이 많은 성체 나비들에게 꿀을 제공하는 반면, 이 식물은 다른 밀크위드 종들보다 나비 정원과 군주 간이역에서 사용하기에 덜 적합할 수 있습니다.[253]

사육 군주들은 늪의 밀크위드(A. incarnata)에 알을 낳는 것을 선호합니다.[254][257][258][259][260] 그러나 A. incarnata는 보통 습지 가장자리와 계절적으로 침수된 지역에서 자라는 초기 연속 식물입니다. 이 식물은 씨앗을 통해 퍼지는 속도가 느리고, 달리기 선수에 의해 퍼지지 않으며, 식물 밀도가 증가하고 서식지가 건조해짐에 따라 사라지는 경향이 있습니다.[261] A. incarnata 식물은 최대 20년까지 생존할 수 있지만 대부분은 정원에서 2-5년만 삽니다. 이 종은 그늘에 강하지 않으며 좋은 식물 경쟁자가 아닙니다.[261]

참고 항목

참고문헌

- ^ Walker, A.; Thogmartin, W. E.; Oberhauser, K. S.; Pelton, E. M.; Pleasants, J. M. (2022). "Danaus plexippus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2022: e.T159971A806727. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2022-1.RLTS.T159971A806727.en. Retrieved December 6, 2022.

- ^ a b c "Migratory Monarch Butterfly". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

- ^ Committee on Generic Nomenclature, Royal Entomological Society of London (2007) [1934]. The Generic Names of British Insects. Royal Entomological Society of London Committee on Generic Nomenclature, Committee on Generic Nomenclature. British Museum (Natural History). Dept. of Entomology. p. 20.

- ^ Scudder, Samuel Hubbard; Davis, William M.; Woodworth, Charles W.; Howard, Leland O.; Riley, Charles V.; Williston, Samuel (1889). The butterflies of the eastern United States and Canada with special reference to New England. The author. p. 721. ISBN 978-0-665-26322-4 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Moore (1883). "Anosia plexippus". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London: 234–235. (Cited in Scudder, Samuel Hubbard; Davis, William M.; Woodworth, Charles W.; Howard, Leland O.; Riley, Charles V.; Williston, Samuel (1889). The butterflies of the eastern United States and Canada: with special reference to New England: Anosia plexippus - The monarch. Vol. 1. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The author. p. 720. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.9161. ISBN 978-0-665-26322-4. LCCN 06021638. OCLC 2604754. Retrieved December 27, 2023 – via HathiTrust.)

- ^ a b c d e f Agrawal, Anurag (March 7, 2017). Monarchs and Milkweed: A Migrating Butterfly, a Poisonous Plant, and Their Remarkable Story of Coevolution. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9781400884766.

- ^ a b Savela, Markku (February 25, 2019). "Danaus plexippus (Linnaeus, 1758)". Lepidoptera and Some Other Life Forms. Retrieved July 11, 2020.

- ^ "Conserving Monarch Butterflies and their Habitats". USDA. 2015.

- ^ Jones, Patricia L.; Agrawal, Anurag A. (2016). "Consequences of toxic secondary compounds in nectar for mutualist bees and antagonist butterflies". Ecology. 97 (10): 2570–2579. doi:10.1002/ecy.1483. hdl:1813/66741. ISSN 1939-9170. PMID 27859127.

- ^ MacIvor, James Scott; Roberto, Adriano N.; Sodhi, Darwin S.; Onuferko, Thomas M.; Cadotte, Marc W. (2017). "Honey bees are the dominant diurnal pollinator of native milkweed in a large urban park". Ecology and Evolution. 7 (20): 8456–8462. doi:10.1002/ece3.3394. ISSN 2045-7758. PMC 5648680. PMID 29075462.

- ^ a b Garber, Steven D. (1998). The Urban Naturalist. Courier Dover Publications. pp. 76–79. ISBN 978-0-486-40399-1.

- ^ Groth, Jacob (November 10, 2000). "Do Farm-Raised Monarchs Migrate?". Swallowtail Farms. Retrieved July 21, 2014.

- ^ "Monarch Migration". Monarch Joint Venture. 2013.

- ^ "Butterflies Emerge from Cocoons Aboard Station". NASA. 2009. Archived from the original on December 15, 2009.

- ^ "First Monarch butterflies in space take flight". NBC News. December 9, 2009. Retrieved November 12, 2023.

- ^ Adams, Jean Ruth (1992). Insect Potpourri: Adventures in Entomology. CRC Press. pp. 28–29. ISBN 978-1-877743-09-2.

- ^ Linnaeus, Carl (1758). Systema Naturae (in Latin). Vol. 1. Stockholm: Laurentius Salvius. p. 471. OCLC 174638949. Retrieved June 5, 2012.

- ^

- Moore (1883). "Anosia plexippus". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London: 234–235. (Cited in Scudder, Samuel Hubbard; Davis, William M.; Woodworth, Charles W.; Howard, Leland O.; Riley, Charles V.; Williston, Samuel (1889). The butterflies of the eastern United States and Canada: with special reference to New England: Anosia plexippus - The monarch. Vol. 1. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The author. p. 720. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.9161. ISBN 978-0-665-26322-4. LCCN 06021638. OCLC 2604754. Retrieved December 27, 2023 – via HathiTrust.)

- Scudder, Samuel Hubbard (1888). "The Natural History of Anosia Plexippus in New England". Psyche: A Journal of Entomology. Cambridge, Massachusetts: 63–66. Retrieved December 26, 2023 – via Internet Archive.

- Scudder, Samuel Hubbard; Davis, William M.; Woodworth, Charles W.; Howard, Leland O.; Riley, Charles V.; Williston, Samuel (1889). The butterflies of the eastern United States and Canada: with special reference to New England: Anosia plexippus - The monarch. Vol. 1. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The author. pp. 720-748. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.9161. ISBN 978-0-665-26322-4. LCCN 06021638. OCLC 2604754. Retrieved December 27, 2023 – via HathiTrust.

- Holland, William Jacob (1898). The Butterfly Book: A Popular Guide To A Knowledge Of The Butterflies Of North America. Garden City, New York: Country Life Press. pp. 63, 81. Retrieved December 26, 2023 – via Project Gutenberg.

Linnæus for a fanciful reason gave this insect the name Plexippus. This is its specific name, by which it is distinguished from all other butterflies. It belongs to the genus Anosia. The genus Anosia is one of the genera which make up the subfamily of the Euplœinæ. The Euplœinæ belong to the great family of the Nymphalidæ. The Nymphalidæ are a part of the suborder of the Rhopalocera, or true butterflies, one of the two great subdivisions of the order Lepidoptera, belonging to the great class Insecta, the highest class in the subkingdom of the Arthropoda. (page 63)

- Teale, Edwin Way (December 1944). "Observations on the migration of the monarch butterfly (Anosia plexippus)". Bulletin of the Brooklyn Entomological Society. Brooklyn, New York. 39: 161–163. Retrieved December 24, 2023 – via Biodiversity Heritage Library.

- ^ a b c Smith, David A.S.; Lushai, Gugs; Allen, John A. (June 10, 2005). "A classification of Danaus butterflies (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae) based upon data from morphology and DNA". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. Oxford, Oxfordshire, England: Oxford University Press. 144 (2): 191–212. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2005.00169.x. Archived from the original on June 4, 2018. Retrieved December 22, 2023.

- ^ πλήξιππος. 리델, 헨리 조지; 스콧, 로버트; 페르세우스 프로젝트의 그리스-영어 어휘

- ^ 린네, C. (1758) Systema Naturaeed. X: 467. BHL.

- ^ Pyle, Robert Michael (2001). Chasing Monarchs: Migrating with the Butterflies of Passage. Houghton Mifflin Books. pp. 148–149. ISBN 978-0-618-12743-6.

- ^ Ackery, P. R.; Vaine-Wright, R. I. (1984). Milkweed butterflies, their cladistics and biology: being an account of the natural history of the Danainae, subfamily of the Lepidoptera, Nymphalidae. British Museum (Natural History), London. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-565-00893-2.

- ^ a b Gibbs, Lawrence; Taylor, O. R. (1998). "The White Monarch". Department of Entomology University of Kansas. Retrieved July 17, 2014.

- ^ Groth, Jacob (February 12, 2022). "Monarch Butterfly Mutants". Swallowtail Farms. Retrieved July 22, 2014.

- ^ a b Hay-Roe, Miriam M.; Lamas, Gerardo; Nation, James L. (2007). "Pre- and postzygotic isolation and Haldane rule effects in reciprocal crosses of Danaus erippus and Danaus plexippus (Lepidoptera: Danainae), supported by differentiation of cuticular hydrocarbons, establish their status as separate species". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 91 (3): 445–453. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.2007.00809.x.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Petition to protect the Monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus plexippus) under the endangered species act" (PDF). Xerces Society. Retrieved September 1, 2014.

- ^ Zhan, Shuai; Merlin, Christine; Boore, Jeffrey L.; Reppert, Steven M. (November 2011). "The Monarch Butterfly Genome Yields Insights into Long-Distance Migration". Cell. 147 (5): 1171–85. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2011.09.052. PMC 3225893. PMID 22118469.

- ^ Stensmyr, Marcus C.; Hansson, Bill S. (November 2011). "A Genome Befitting a Monarch". Cell. 147 (5): 970–2. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2011.11.009. PMID 22118454. S2CID 16035019.

- ^ Johnson, Carolyn Y. (November 23, 2011). "Monarch butterfly genome sequenced". Boston Globe. Boston, MA. Retrieved January 9, 2012.

- ^ Zhan, Shuia; Zhang, Wei; Niitepold, Kristjan; Hsu, Jeremy; Haeger, Juan Fernandez; Zalucki, Myron P.; Altizer, Sonia; de Roode, Jacobus C.; Reppert, Stephen M.; Kronforst, Marcus R. (October 1, 2014). "The genetics of Monarch butterfly migration and warning coloration". Nature. 514 (7522): 317–321. Bibcode:2014Natur.514..317Z. doi:10.1038/nature13812. PMC 4331202. PMID 25274300.

- ^ a b Zhan, Shuai; Merlin, Christine; Boore, Jeffrey L.; Reppert, Steven M. (November 23, 2012). "The monarch butterfly genome yields insights into long-distance migration". Cell. 147 (5): 1171–1185. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2011.09.052. PMC 3225893. PMID 22118469.

- ^ Gasmi, Laila; Boulain, Helene; Gauthier, Jeremy; Hua-Van, Aurelie; Musset, Karine; Jakubowska, Agata K.; Aury, Jean-Marc; Volkoff, Anne-Nathalie; Huguet, Elisabeth (September 17, 2015). "Recurrent Domestication by Lepidoptera of Genes from Their Parasites Mediated by Bracoviruses". PLOS Genetics. 11 (9): e1005470. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1005470. PMC 4574769. PMID 26379286.

- ^ Le Page, Michael (September 17, 2015). "If viruses transfer wasp genes into butterflies, are they GM?". New Scientist. Retrieved July 13, 2016.

- ^ Main, Douglas (September 17, 2015). "Wasps Have Genetically Modified Butterflies, Using Viruses". Newsweek. Archived from the original on August 9, 2016. Retrieved July 13, 2016.

- ^ a b Overhauser (2004), p. 3

- ^ "Monarch Butterfly Life Cycle and Migration". National Geographic Education. October 24, 2008. Archived from the original on April 6, 2011. Retrieved August 15, 2013.

- ^ "Egg". Monarch Joint Venture. 2021. Archived from the original on July 11, 2021. Retrieved October 6, 2021.

- ^ Oberhauser, Karen S.; Solensky, Michelle J (2004). The Monarch Butterfly: Biology and Conservation (First ed.). Ithaca NY: Cornell University Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-0801441882.

- ^ Lefevre, T.; Chiang, A.; Li, H; Li, J; de Castillejo, C.L.; Oliver, L.; Potini, Y.; Hunter, M. D.; de Roode, J.C. (2012). "Behavioral resistance against a protozoan parasite in the monarch butterfly" (PDF). Journal of Animal Ecology. 81 (1): 70–9. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2656.2011.01901.x. hdl:2027.42/89483. PMID 21939438.

- ^ "The other butterfly effect – A youth reporter talks to Jaap de Roode". TED Blog. November 25, 2014. Retrieved December 12, 2014.

- ^ Overhauser 2004, 페이지 51.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Guide to Monarch Instars". Monarch Joint Venture. 2021. Archived from the original on August 13, 2021. Retrieved October 1, 2021.

- ^ Collie, Joseph; Granela, Odelvys; Brown, Elizabeth B.; Keene, Alex C. (November 2020). "Aggression Is Induced by Resource Limitation in the Monarch Caterpillar". iScience. 23 (12): 101791. Bibcode:2020iSci...23j1791C. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2020.101791. PMC 7756136. PMID 33376972.

- ^ Petersen, B. (1964). "Humidity, Darkness, and Gold Spots as Possible Factors in Pupal Duration of Monarch Butterflies". Journal of the Lepidopterists' Society. 18: 230–232.

- ^ "Pupa". Monarch Joint Venture. 2021. Archived from the original on July 11, 2021. Retrieved October 5, 2021.

- ^ Pocius, V. M.; Debinski, D. M.; Pleasants, J. M.; Bidne, K. G.; Hellmich, R. L.; Brower, L. P. (September 7, 2017). "Milkweed Matters: Monarch Butterfly (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae) Survival and Development on Nine Midwestern Milkweed Species". Environmental Entomology. 46 (5): 1098–1105. doi:10.1093/ee/nvx137. ISSN 0046-225X. PMC 5850784. PMID 28961914.

- ^ "Reproduction". Monarch Lab. Regents of the University of Minnesota. Archived from the original on July 16, 2019. Retrieved December 13, 2014.

- ^ a b Braby, Michael F. (2000). Butterflies of Australia: Their Identification, Biology and Distribution. CSIRO Publishing. pp. 597–599. ISBN 978-0-643-06591-8.

- ^ Satterfield, Dara A.; Davis, Andrew K. (April 2014). "Variation in wing characteristics of monarch butterflies during migration: Earlier migrants have redder and more elongated wings". Animal Migration. 2 (1). doi:10.2478/ami-2014-0001.

- ^ Davis, A. K.; Holden, Michael T. (2015). "Measuring Intraspecific Variation in Flight-Related Morphology of Monarch Butterflies (Danaus plexippus): Which Sex Has the Best Flying Gear?" (PDF). Journal of Insects. Hindawi Publishing Corporation. 2015 (59170): 1–6. doi:10.1155/2015/591705. Retrieved October 17, 2020.

- ^ "Monarch, Danaus plexippus". Archived from the original on December 15, 2012. Retrieved August 27, 2008.

- ^ "Adult". Monarch Joint Venture. 2021. Archived from the original on July 21, 2021. Retrieved October 5, 2021.

- ^ "Sensory Systems". Biology. Monarch Watch. Archived from the original on March 19, 2018. Retrieved October 5, 2021.

- ^ "Sexing Monarchs". Biology. Monarch Watch. Archived from the original on May 5, 2021. Retrieved October 5, 2021.

- ^ Darby, Gene (1958). What is a Butterfly. Chicago: Benefic Press. p. 10.

- ^ Flockhart, D. T. Tyler; Martin, Tara G.; Norris, D. Ryan (2012). "Experimental Examination of Intraspecific Density-Dependent Competition during the Breeding in Monarch Butterflies (Danaus plexippus)". PLOS ONE. 7 (9): e45080. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...745080F. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0045080. PMC 3440312. PMID 22984614.

- ^ a b c Blackiston, Douglas; Briscoe, Adriana D.; Weiss, Martha R. (February 1, 2011). "Color vision and learning in the monarch butterfly, Danaus plexippus (Nymphalidae)". The Journal of Experimental Biology. 214 (Pt 3): 509–520. doi:10.1242/jeb.048728. ISSN 1477-9145. PMID 21228210.

- ^ Stalleicken, Julia; Labhart, Thomas; Mouritsen, Henrik (March 2006). "Physiological characterization of the compound eye in monarch butterflies with focus on the dorsal rim area". Journal of Comparative Physiology A. 192 (3): 321–331. doi:10.1007/s00359-005-0073-6. ISSN 0340-7594. PMID 16317560. S2CID 31493135.

- ^ Sauman, Ivo; Briscoe, Adriana D.; Zhu, Haisun; Shi, Dingding; Froy, Oren; Stalleicken, Julia; Yuan, Quan; Casselman, Amy; Reppert, Steven M. (May 5, 2005). "Connecting the Navigational Clock to Sun Compass Input in Monarch Butterfly Brain". Neuron. 46 (3): 457–467. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2005.03.014. ISSN 0896-6273. PMID 15882645. S2CID 17755509.

- ^ a b Cepero, Laurel C.; Rosenwald, Laura C.; Weiss, Martha R. (July 1, 2015). "The Relative Importance of Flower Color and Shape for the Foraging Monarch Butterfly (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae)". Journal of Insect Behavior. 28 (4): 499–511. doi:10.1007/s10905-015-9519-z. ISSN 1572-8889. S2CID 18380612.

- ^ 에멜, 토마스 C. (1997) 플로리다의 멋진 나비들. 44쪽, World Publications, ISBN 0-911977-15-5

- ^ Overhauser (2004), pp. 61–68.

- ^ Frey, D.; Leong, K. L. H.; Peffer, E.; Smidt, R. K.; Oberhauser, K. S. (1998). "Mating patterns of overwintering monarch butterflies (Danaus plexippus (L.)) in California" (PDF). Journal of the Lepidopterists' Society. 52: 84–97.

- ^ Solensky, M.J.; K.S. Oberhauser (2009). "Sperm Precedence in Monarch Butterflies (Danaus plexippus)". Behavioral Ecology. 20 (2): 328–34. doi:10.1093/beheco/arp003.

- ^ Oberhauser, K. S. (1989). "Effects of spermatophores on male and female monarch butterfly reproductive success". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 25 (4): 237–246. doi:10.1007/bf00300049. S2CID 6843773.

- ^ a b "ADW: Danaus plexippus: Information". Retrieved August 27, 2008.

- ^ Solensky, Michelle J. (November 2004). "The Effect of Behavior and Ecology on Male Mating Success in Overwintering Monarch Butterflies (Danaus plexippus)". Journal of Insect Behavior. 17 (6): 723–743. doi:10.1023/b:joir.0000048985.58159.0d. ISSN 0892-7553. S2CID 31954178.

- ^ Gerald McCormack (December 7, 2005). "Cook Islands' Largest Butterfly – the Monarch". Cook Islands Biodiversity.

- ^ a b 스콧, 제임스 A. (1986) 북미의 나비들. 스탠포드 대학 출판부, 스탠포드, 캘리포니아. ISBN 0-8047-2013-4

- ^ Brower, Lincoln P.; Malcolm, Stephen B. (1991). "Animal Migrations: Endangered Phenomena". American Zoologist. 31 (1): 265–276. doi:10.1093/icb/31.1.265.

- ^ Davis, Donald (November 27, 2014). "DPLEX-L:59250 THE possibility of a trans-Gulf migration, oil rigs, Dr. Gary Ross, and more". Monarch Watch. University of Kansas.

- ^ "Monarch Sightings Map". Monarch Butterfly New Zealand Trust. Archived from the original on February 12, 2021. Retrieved December 15, 2014.

- ^ "The lonely flight of the monarch butterfly". NewsAdvance.com, Lynchburg, Virginia Area. October 4, 2014. Retrieved October 7, 2014.

- ^ "Provisional species list of the Lepidoptera". Gibraltar Ornithological and Natural History Society. Archived from the original on September 25, 2015.

- ^ Pais, Miguel. "Northwestern African sightings of D. plexippus, Maroc>Pappilons>Danaus plexippus". Google Maps. Retrieved September 19, 2014.

- ^ Coombes, Simon. "1995 Monarch Invasion of the UK". butterfly-guide.co.uk. Archived from the original on September 23, 2015. Retrieved September 20, 2014.

- ^ a b Cech, Rick and Tudor, Guy (2005). 동해안의 나비들. 프린스턴 대학교 출판부, 프린스턴, 뉴저지 ISBN 0-691-09055-6

- ^ a b c 이프너, 데이비드 C; 슈에이, 존 A. 그리고 칼훈, 존 C. (1992) 오하이오의 나비와 스키퍼. 생물 과학 대학과 오하이오 주립 대학. ISBN 0-86727-107-8

- ^ "Monarch Butterfly Journey North". Annenberg Learner. Archived from the original on October 14, 2017. Retrieved July 16, 2017.

- ^ Pyle, Robert Michael (2014). Chasing monarchs: Migrating with the butterflies of passage. Yale University Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-0395828205.

- ^ Halpern, Sue (2002). Four Wings and a Prayer. Kindle edition location 1594. New York, New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0-307-78720-0.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s "Plant Milkweed for Monarchs" (PDF). Monarch Joint Venture Partnering across the U.S. to conserve the monarch migration. Monarch Joint Venture. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 21, 2015. Retrieved July 7, 2015.

- ^ USDA, NRCS (n.d.). "Asclepias incarnata". The PLANTS Database (plants.usda.gov). Greensboro, North Carolina: National Plant Data Team.

- ^ Kirk, S.; Belt, S. "Plant fact sheet for swamp milkweed (Asclepias incarnata)" (PDF). Beltsville, Maryland: United States Department of Agriculture: Natural Resources Conservation Service: Norman A. Berg National Plant Materials Center. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 9, 2021.

- ^ Holmes, Forest Russell. "Swamp Milkweed (Asclepias incarnata L.)". Plant of the Week. Washington, D.C.: United States Department of Agriculture: United States Forest Service. Archived from the original on March 28, 2021. Retrieved July 9, 2021.

- ^ "Northeast Region Milkweed Species: Swamp Milkweed: Asclepias incarnata" (PDF). Plant Milkweed for Monarchs. Monarch Joint Venture. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 21, 2015. Retrieved July 7, 2015.

- ^ "Asclepias nivea". Butterfly gardening & all things milkweed. Archived from the original on July 7, 2015. Retrieved July 7, 2015.

- ^ Stevens, Michelle (May 30, 2006). "Plant guide for Asclepias speciosa" (PDF). United States Department of Agriculture: Natural Resources Conservation Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 12, 2021. Retrieved July 12, 2021.

- ^ Young-Mathews, A.; Eldredge, E. (2012). "Plant fact sheet for showy milkweed (Asclepias speciosa)" (PDF). United States Department of Agriculture: Natural Resources Conservation Service, Corvallis Plant Materials Center, Oregon, and Great Basin Plant Materials Center, Fallon, Nevada. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 1, 2021. Retrieved July 12, 2021.

- ^ "Asclepias speciosa". Washington, D.C.: United States Department of Agriculture: United States Forest Service. Archived from the original on March 7, 2021. Retrieved July 12, 2021.

- ^ Wiese, Karen (2000). "Showy Milkweed: Asclepias speciosa". Sierra Nevada wildflowers: a field guide to common wildflowers and shrubs of the Sierra Nevada, including Yosemite, Sequoia, and Kings Canyon National Parks. Helena, Montana: Falcon Publishing, Inc. p. 50. ISBN 0585362831. LCCN 00022385. OCLC 47011272. Retrieved July 12, 2021 – via Internet Archive.

- ^

- Stevens, Michelle. "Plant guide for common milkweed (Asclepias syriaca)" (PDF). Washington, D.C.: United States Department of Agriculture: Natural Resources Conservation Service: National Plant Data Center. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 5, 2021. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- Taylor, David. "Common Milkweed (Asclepias syriaca L.)". Plant of the Week. United States Department of Agriculture, United States Forest Service. Archived from the original on January 22, 2023. Retrieved December 24, 2023.

- Higgins, Adrian (May 27, 2015). "A gardener's guide to saving the monarch". Home & Garden. The Washington Post. Archived from the original on September 26, 2020. Retrieved October 17, 2020.

- Higgins, Adrian (May 27, 2015). "7 milkweed varieties and where to find them". Home & Garden. The Washington Post. Archived from the original on September 26, 2020. Retrieved October 17, 2020.

- Gomez, Tony (March 14, 2013). "Asclepias syriaca: Common Milkweed for Monarch Caterpillars". Monarch Butterfly Garden. MonarchButterflyGarden.net. Archived from the original on March 16, 2015. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- "Asclepias syriaca". Butterfly gardening & all things milkweed. Archived from the original on July 7, 2015. Retrieved July 7, 2015.

- "Northeast Region Milkweed Species: Common Milkweed: Asclepias syriaca" (PDF). Plant Milkweed for Monarchs. Monarch Joint Venture. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 21, 2015. Retrieved July 7, 2015.

- ^ Davis, Lee (May 31, 2006). "Plant guide for Green Milkweed: Asclepias viridis Walt" (PDF). Washington, D.C.: United States Department of Agriculture: Natural Resources Conservation Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 11, 2021. Retrieved July 11, 2021.

- ^ Taylor, David. "Green Antelopehorn (Asclepias viridis)". Plant of the Week. Washington, D.C.: United States Department of Agriculture: United States Forest Service. Archived from the original on March 27, 2021. Retrieved July 11, 2021.

- ^ Borders, Brianna, The Xerces Society; Casey, Allen, USDA-NRCS Missouri; Row, John M., USDA-NRCS Kansas; Wynia, Rich, USDA-NRCS Kansas; King, Randy, USDA-NRCS Arkansas; Jacobs, Alayna, USDA-NRCS Arkansas; Taylor, Chip, Monarch Watch; Mader, Eric, The Xerces Society (June 24, 2013). Walls, Hailey, The Xerces Society; Rich, Kaitlyn, The Xerces Society (eds.). "Asclepias viridis Green antelopehorn" (PDF). Pollinator Plants of the Central United States: Native Milkweeds (Asclepias spp.). Washington, D.C.: United States Department of Agriculture: Natural Resources Conservation Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 31, 2021. Retrieved July 11, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: 다중 이름: 저자 목록 (링크) - ^ "Asclepias viridis: Spider Milkweed". NatureServe. Archived from the original on September 19, 2015. Retrieved July 11, 2021.

- ^ "Butterfly Society of Hawaii". Butterfly Society of Hawaii. Retrieved January 6, 2017.

- ^ 나비 정원 가꾸기. kansasnativeplants.com

- ^ 바그너, 데이비드 L. (2005) 북아메리카 동부의 애벌레. 프린스턴 대학교 출판부, 프린스턴, 뉴저지 ISBN 0-691-12144-3

- ^ Howard, Elizabeth; Aschen, Harlen; Davis, Andrew K. (2010). "Citizen Science Observations of Monarch Butterfly Overwintering in the Southern United States". Psyche. 2010: 1. doi:10.1155/2010/689301.

- ^ Satterfield, D. A.; Maerz, J. C.; Altizer, S (2015). "Loss of migratory behaviour increases infection risk for a butterfly host". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 282 (1801): 20141734. doi:10.1098/rspb.2014.1734. PMC 4308991. PMID 25589600.

- ^ Majewska, Ania A.; Altizer, Sonia (August 16, 2019). "Exposure to Non-Native Tropical Milkweed Promotes Reproductive Development in Migratory Monarch Butterflies". Insects. 10 (8): 253. doi:10.3390/insects10080253. PMC 6724006. PMID 31426310.

- ^ "Nectar Plants for Butterflies & Other Pollinators" (PDF). Plants for Butterfly and Pollinator Gardens: Native and Non-native Plants Suitable for Gardens in the Northeastern United States. Monarch Watch. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved October 1, 2021.

- ^ Reppert, Steven M (2018). "Demystifying monarch butterfly migration". Current Biology. 28 (17): R1009–R1022. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2018.02.067. PMID 30205052. S2CID 52186799.

- ^ "North American Monarch Conservation Plan" (PDF). Commission for Environmental Cooperation. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 28, 2016. Retrieved October 17, 2014.

- ^ Taylor, O. R. (August 3, 2000). "Monarch Watch 1999 Season Recoveries" (PDF). pp. 1–11. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 6, 2014. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ a b Steffy, Gayle (2015). "Trends observed in fall migrant Monarch butterflies (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae) east of the Appalachian Mountains at an inland stopover in southern Pennsylvania over an eighteen year period". Annals of the Entomological Society of America. 108 (5): 718. doi:10.1093/aesa/sav046. S2CID 86201332.

- ^ "Monarch butterflies are a steady presence in Arizona". Arizona Daily Star. Retrieved January 15, 2016.

- ^ "Butterfly genomics: Monarchs migrate and fly differently, but meet up and mate". phys.org. Retrieved July 31, 2020.

- ^ Nail, Kelly R. (2019). "Butterflies Across the Globe: A Synthesis of the Current Status and Characteristics of Monarch (Danaus plexippus) Populations Worldwide". Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution. 27: 362. doi:10.3389/fevo.2019.00362.

- ^ "monarchscience". Akdavis6.wixsite.com. December 31, 2016. Retrieved January 6, 2017.

- ^ "monarchscience". Akdavis6.wixsite.com. April 5, 2016.

- ^ a b Barbosa, Pedro; Deborah Kay Letourneau (1988). "5". Novel Aspects of Insect-plant Interactions. Wiley-Interscience. pp. 29–31. ISBN 978-0-471-83276-8.

- ^ "Butterfly Weed: Asclepias tuberosa" (PDF). Becker County, Minnesota: Becker Soil and Water Conservation District. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 11, 2020. Retrieved September 11, 2020.

Unlike other milkweeds, this plant has a clear sap, and the level of toxic cardiac glycosides is consistently low (although other toxic compounds may be present).

- ^ Mikkelsen, Lauge Hjorth; Hamoudi, Hassan; Altuntas Gül, Cigdem; Heegaard, Steffen (2017). "Corneal Toxicity Following Exposure to Asclepias tuberosa". The Open Ophthalmology Journal. Bentham Science Publishers. 11: 1–4. doi:10.2174/1874364101711010001. PMC 5362972. PMID 28400886.

The latex of A. tuberosa seems to be different from other Asclepias species due to the fact that even though cardenolides are normally present in Asclepias species, these cardenolides have not been found in A. tuberosa. Instead some unique pregnane glycosides are found in A. tuberosa.

- ^ Warashina, Tsutomu; Noro, Tadataka (February 2010). "8,12;8,20-Diepoxy-8,14-secopregnane Glycosides from the Aerial Parts of Asclepias tuberosa". Chemical and Pharmaceutical Bulletin. Pharmaceutical Society of Japan. 58 (2): 172–179. doi:10.1248/cpb.58.172. PMID 20118575. Retrieved September 11, 2020.

Though cardenolides are considered to be characteristic constituents of Asclepias spp. together with pregnane glycosides, we could find no cardenolides in the more hydrophobic fraction of the methanol extract of the aerial parts of A. tuberosa, the same as previously.

- ^

- Gunn, John (May 20, 2016). "Milkweeds (mostly Asclepias spp.)". Alonso Abugattas Shares Native Plant Picks for Wildlife. Mid-Atlantic Gardener (John Gunn). Archived from the original on October 21, 2020. Retrieved October 17, 2020.

And if you have hot, dry conditions in your yard, try Butterflyweed (A. tuberosa). ... It's the least favored by Monarch caterpillars because it has very little toxin (cardiac glycosides) in its leaves.

- Abugattas, Alonzo (January 3, 2017). "Monarch Way Stations". Capital Naturalist. Archived from the original on June 5, 2017. Retrieved June 5, 2017 – via Blogger.

(A. tuberosa) is the least favored by monarch caterpillars .... because it has very little toxin (cardiac glycosides) in its leaves

- Gomez, Tony. "Asclepias tuberosa: Butterfly Weed for Monarchs and More". Monarch Butterfly Garden. MonarchButterflyGarden.net. Archived from the original on August 16, 2017. Retrieved October 17, 2010.

Rough leaves for monarch caterpillars, not typically a heavily used host plant

- Pocius, Victoria M.; Debinski, Diane M.; Pleasants, John M.; Bidne, Keith G.; Hellmich, Richard L. (January 8, 2018). "Monarch butterflies do not place all of their eggs in one basket: oviposition on nine Midwestern milkweed species". Ecosphere. Ecological Society of America. 9 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1002/ecs2.2064.

In our study, the least preferred milkweed species A. tuberosa (no choice; Fig. 2) and A. verticillata (choice; Fig. 3A) both have low cardenolide levels recorded in the literature (Roeske et al. 1976, Agrawal et al. 2009, 2015, Rasmann and Agrawal 2011)

- Gunn, John (May 20, 2016). "Milkweeds (mostly Asclepias spp.)". Alonso Abugattas Shares Native Plant Picks for Wildlife. Mid-Atlantic Gardener (John Gunn). Archived from the original on October 21, 2020. Retrieved October 17, 2020.

- ^ Pocius, Victoria M.; Debinski, Diane M.; Pleasants, John M.; Bidne, Keith G.; Hellmich, Richard L. (January 8, 2018). "Monarch butterflies do not place all of their eggs in one basket: oviposition on nine Midwestern milkweed species". Ecosphere. Ecological Society of America (ESA). 9 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1002/ecs2.2064.

In our study, the least preferred milkweed species A. tuberosa (no choice; Fig. 2) and A. verticillata (choice; Fig. 3A) both have low cardenolide levels recorded in the literature (Roeske et al. 1976, Agrawal et al. 2009, 2015, Rasmann and Agrawal 2011)

- ^ a b Brower, Lincoln (1988). "Avian Predation on the Monarch Butterfly and Its Implications for Mimicry Theory". The American Naturalist. 131: S4–S6. doi:10.1086/284763. S2CID 84642806.

- ^ Fink, Linda S.; Brower, Lincoln P. (May 1981). "Birds can overcome the cardenolide defence of monarch butterflies in Mexico". Nature. 291 (5810): 67–70. Bibcode:1981Natur.291...67F. doi:10.1038/291067a0. ISSN 0028-0836. S2CID 4305401.

- ^ Groen, Simon C.; Whiteman, Noah K. (November 2021). "Convergent evolution of cardiac-glycoside resistance in predators and parasites of milkweed herbivores". Current Biology. 31 (22): R1465–R1466. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2021.10.025. ISSN 0960-9822. PMC 8892682. PMID 34813747. S2CID 244485686.

- ^ Stimson, John; Mark Berman (1990). "Predator induced colour polymorphism in Danaus plexippus L. (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae) in Hawaii". Heredity. 65 (3): 401–406. doi:10.1038/hdy.1990.110.

- ^ a b Álvarez-Castañeda, Sergio Ticul (2005). "Peromyscus melanotis". Mammalian Species. 2005 (764): 1–4. doi:10.1644/1545-1410(2005)764[0001:PM]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 198968529.

- ^ Koch, R. L.; W. D. Hutchison; R. C. Venette; G. E. Heimpel (October 2003). "Susceptibility of immature monarch butterfly, Danaus plexippus (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae: Danainae), to predation by Harmonia axyridis (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae)". Biological Control. 28 (2): 265–270. doi:10.1016/S1049-9644(03)00102-6.

- ^ Rafter, Jamie; Anurag Agruwal; Evan Preisser (2013). "Chinese mantids gut caterpillars: avoidance of prey defense?". Ecological Entomology. 38 (1): 78–82. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2311.2012.01408.x. S2CID 15029022.

- ^ Zalucki, Myron P.; Malcolm, Stephen B.; Paine, Timothy D.; Hanlon, Christopher C.; Brower, Lincoln P.; Clarke, Anthony R. (2001). "It's the first bites that count: Survival of first-instar monarchs on milkweeds". Austral Ecology. 26 (5): 547–555. doi:10.1046/j.1442-9993.2001.01132.x.

- ^ Overhauser 2004, 페이지 44.

- ^ a b c Karageorgi, Marianthi; Groen, Simon C.; Sumbul, Fidan; Pelaez, Julianne N.; Verster, Kirsten I.; Aguilar, Jessica M.; Hastings, Amy P.; Bernstein, Susan L.; Matsunaga, Teruyuki; Astourian, Michael; Guerra, Geno (October 2019). "Genome editing retraces the evolution of toxin resistance in the monarch butterfly". Nature. 574 (7778): 409–412. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1610-8. ISSN 1476-4687. PMC 7039281. PMID 31578524.

- ^ a b Parsons, J.A. (1965). "A Digitallis-like Toxin in the Monarch Butterfly Danaus plexippus L". The Journal of Physiology. 178 (2): 290–304. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.1965.sp007628. PMC 1357291. PMID 14298120.

- ^ Malcolm, S. B.; L. P. Brower (1989). "Evolutionary and ecological implications of cardenolide sequestration in the monarch butterfly". Experientia. 45 (3): 284–295. doi:10.1007/BF01951814. S2CID 9967183.

- ^ "CRISPRed flies mimic monarch butterfly — and could make you vomit Research UC Berkeley". vcresearch.berkeley.edu. Retrieved December 18, 2021.

- ^ a b de Rood, J. C.; De Castillejo, C. L.; Faits, T.; Alizon, S. (2011). "Virulence evolution in response to anti-infection resistance: toxic food plants can select for virulent parasites of monarch butterflies". Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 24 (4): 712–722. doi:10.1111/j.1420-9101.2010.02213.x. PMID 21261772. S2CID 1533504.

- ^ "Is tropical milkweed really medicinal? (answer: yes, and that's really really bad for your garden)". monarchscience. March 16, 2017. Retrieved December 12, 2019.

- ^ Glazier, Lincoln; Susan Glazier (1975). "Localization of Heart Poisons in the Monarch Butterfly". Science. 188 (4183): 19–25. Bibcode:1975Sci...188...19B. doi:10.1126/science.188.4183.19. PMID 17760150. S2CID 44509809.

- ^ Ritland, D.; L. P. Brower (1991). "The viceroy butterfly is not a Batesian mimic". Nature. 350 (6318): 497–498. Bibcode:1991Natur.350..497R. doi:10.1038/350497a0. S2CID 28667520.

Viceroys are as unpalatable as monarchs, and significantly more unpalatable than queens from representative Florida populations.

- ^ "Official Alabama Insect". Alabama Emblems, Symbols and Honors. Alabama Department of Archives & History. July 12, 2001. Archived from the original on October 14, 2018. Retrieved March 19, 2007.

- ^ "Idaho Symbols, Insect: Monarch Butterfly". Idaho State Symbols, Emblems, and Mascots. SHG resources, state handbook & guide. Archived from the original on February 8, 2012. Retrieved March 26, 2008.

- ^ "State Symbol: Illinois Official Insect — Monarch Butterfly (Danaus plexippus)". [Illinois] State Symbols. Illinois State Museum. Retrieved March 26, 2008.

- ^ "Minnesota State Symbols" (PDF). Minnesota House of Representatives. Retrieved March 26, 2008.

- ^ "Texas State Symbols". The Texas State Library and Archives. Archived from the original on December 24, 2018. Retrieved March 26, 2008.

- ^ "(Vermont) State Butterfly". Vermont Department of Libraries. Archived from the original on May 18, 2008. Retrieved March 26, 2008.

- ^ "West Virginia Statistical Information, General State Information" (PDF). Official West Virginia Web Portal. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 11, 2008. Retrieved March 26, 2008.

- ^ Wade, Nicholas (June 1, 1990). "Choosing a National Bug". The New York Times. Retrieved September 27, 2017.

- ^ "Designating the monarch butterfly as the national insect. (1989 - H.J.Res. 411)". GovTrack.us.

- ^ "Designating the monarch butterfly as the national insect. (1991 - H.J.Res. 200)". GovTrack.us.

- ^ "Monarch Watch: Monarch Waystation Program". University of Kansas, Entomology Department. Archived from the original on November 18, 2019. Retrieved February 26, 2019.

- ^ "Flight of the Butterflies". Reuben H. Fleet Science Center. Archived from the original on February 17, 2013. Retrieved February 18, 2013.

- ^ "Saving Butterflies: Insect Ecologist Spearheads Creation of Oases for Endangered Butterflies". ScienceDaily. January 1, 2005. Archived from the original on June 4, 2008. Retrieved May 27, 2008.

- ^ Nicoletti, Mélanie; Gilles, Florent; Galicia-Mendoza, Ivette; Rendón-Salinas, Eduardo; Alonso, Alfonso; Contreras-Garduño, Jorge (2020). "Physiological Costs in Monarch Butterflies Due to Forest Cover and Visitors". Ecological Indicators. 117: 106592. doi:10.1016/j.ecolind.2020.106592.

- ^ "Monarch Monitoring Project". Cap May Bird Observatory. 2008. Archived from the original on December 20, 2008. Retrieved December 5, 2008.

- ^ Kingsolver, Barbara (2012). Flight Behavior. HarperCollins.

- ^ "Live butterfly release for funerals and butterfly weddings". Fragrant Acres Butterfly Farm. Retrieved November 14, 2014.

- ^ "In Memory of 9/11 "Wings of Hope"". gayandciha.com. September 4, 2014. Retrieved November 14, 2014.

- ^ Johnson, Pam (August 24, 2010). "Join Branford Rotary's 9/11 Town Green Event/Butterfly Release". Shure Publishing. The Day. Retrieved November 14, 2014.

- ^ "Ormond Beach Flying US Flags On Granada Bridge T0 Mark 9\17". NewsDaytonaBeach.com. WNDB Local News First. 2013. Archived from the original on November 29, 2014. Retrieved November 14, 2014.

- ^ "Monarch Butterfly release at Children's Museum of Fond du Lac". FDL Reporter. Retrieved November 14, 2014.

- ^ a b "Monarch Watch". University of Kansas, Entomology Department. Archived from the original on July 20, 2012. Retrieved February 20, 2014.

- ^ John Platt TakePart (October 14, 2015). "When Butterflies Shouldn't Fly Free". The Huffington Post. Retrieved January 12, 2017.

- ^ "Are We Loving Monarchs to Death? – The Crux". Blogs.discovermagazine.com. June 21, 2016. Archived from the original on April 14, 2020. Retrieved January 12, 2017.

- ^ Love, Orlan (August 25, 2016). "Monarch Moonshot: Officials hope to make Linn County center of butterfly production and habitat". The Gazette. Retrieved January 12, 2017.

- ^ 책임감 있는 모나크 사육: 과학과 교육을 위한 모나크 사육에 대한 한 환경보호론자의 안내서 2021년 9월 14일 웨이백 머신에 보관되어 있습니다. 미네소타 대학교 모나크 조인트 벤처

- ^ "monarchscience". Akdavis6.wixsite.com. September 7, 2015.

- ^ Tenger-Trolander, Ayşe; Lu, Wei; Noyes, Michelle; Kronforst, Marcus R. (July 16, 2019). "Contemporary loss of migration in monarch butterflies". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 116 (29): 14671–14676. Bibcode:2019PNAS..11614671T. doi:10.1073/pnas.1904690116. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 6642386. PMID 31235586.

- ^ Maeckle , Monika (July 2, 2019). "Study of 'genetic franken monarchs' provokes online ire and debate". texasbutterflyranch. Retrieved December 12, 2019.

- ^ "Effects of captive-rearing on caterpillar anti-predator behavior - an inside look at some preliminary data". monarchscience. August 10, 2019. Retrieved December 12, 2019.

- ^ Fears, Darryl (August 26, 2015). "As pesticides wipe out Monarch butterflies in the U.S., illegal logging is doing the same in Mexico". The Washington Post.

- ^ "The Monarch butterfly population in California has plummeted 86% in one year". January 7, 2019.

- ^ "Monarch butterfly population moves closer to extinction". phys.org. Retrieved January 21, 2021.

- ^ Dellinger, AJ (July 21, 2022). "The monarch butterfly is endangered now, you monsters". Mic. Retrieved July 22, 2022.

- ^ a b Semmens, Brice X.; Semmens, Darius J.; Thogmartin, Wayne E.; Wiederholt, Ruscena; López-Hoffman, Laura; Diffendorfer, Jay E.; Pleasants, John M.; Oberhauser, Karen S.; Taylor, Orley R. (2016). "Quasi-extinction risk and population targets for the Eastern, migratory population of monarch butterflies (Danaus plexippus)". Scientific Reports. 6: 23265. Bibcode:2016NatSR...623265S. doi:10.1038/srep23265. PMC 4800428. PMID 26997124.

- ^ Conniff, Richard (April 1, 2013). "Tracking the Causes of Sharp Decline of the Monarch Butterfly". Yale University.

- ^ 와인, 마이클 (2013년 3월 13일). "수십 년 만에 최저 수준으로 추락한 군주의 이주" 뉴욕 타임즈.

- ^ Pleasants, John M.; Oberhauser, Karen S. (2012). "Milkweed loss in agricultural fields because of herbicide use: effect on the monarch butterfly population" (PDF). Insect Conservation and Diversity. 6 (2): 135–144. doi:10.1111/j.1752-4598.2012.00196.x. S2CID 14595378. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 4, 2014.

- ^ a b Brennen, Shannon (July 2014). "For Love of Nature: Annual monarch butterfly migration in peril". The News & Advance, Lynchburg, Virginia. Retrieved July 4, 2014.

- ^ "NRDC Sues EPA Over Demise of Monarch Butterfly Population". NBC. 2015.

- ^ Puzey, J. R.; Dalgleish, H. J.; Boyle, J. H. (February 5, 2019). "Monarch butterfly and milkweed declines substantially predate the use of genetically modified crops". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 116 (8): 3006–3011. Bibcode:2019PNAS..116.3006B. doi:10.1073/pnas.1811437116. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 6386695. PMID 30723147.

- ^ a b Ries, Leslie; Taron, Douglas J.; Rendón-Salinas, Eduardo (2015). "The Disconnect Between Summer and Winter Monarch Trends for the Eastern Migratory Population: Possible Links to Differing Drivers". Annals of the Entomological Society of America. 108 (5): 691. doi:10.1093/aesa/sav055. S2CID 85597731.

- ^ a b Inamine, Hidetoshi; Ellner, Stephen P.; Springer, James P.; Agrawal, Anurag A. (2016). "Linking the continental migratory cycle of the monarch butterfly to understand its population decline". Oikos. 125 (8): 1081. doi:10.1111/oik.03196.

- ^ a b Davis, Andrew K. (2012). "Are migratory monarchs really declining in eastern North America? Examining evidence from two fall census programs". Insect Conservation and Diversity. 5 (2): 101. doi:10.1111/j.1752-4598.2011.00158.x. S2CID 54038257.

- ^ a b "monarchscience". Akdavis6.wixsite.com. August 24, 2016. Retrieved January 6, 2017.

- ^ Mora Alvarez, Blanca Xiomara; Carrera-Treviño, Rogelio; Hobson, Keith A. (2019). "Mortality of Monarch Butterflies (Danaus plexippus) at Two Highway Crossing "Hotspots" During Autumn Migration in Northeast Mexico". Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution. 7. doi:10.3389/fevo.2019.00273. ISSN 2296-701X.

- ^ 파즈, 파티마 (2014년 6월 18일). "Enesera de aprobación de la Propapala alligal en la Reserva de la Mariposa Monarca" 2014년 9월 3일 Wayback Machine. cambiodemichoacan.com.mx 에 보관되었습니다.

- ^ "Habitat Loss on Breeding Grounds Cause of Monarch Decline, U of G Study Finds". University of Guelph. June 4, 2014. Retrieved March 17, 2015.

- ^ "Western Monarch Population Rebound Continues in 2022 but Winter Storms Could Impact Spring Breeding Population". Farmers for Monarchs. February 1, 2023. Retrieved April 14, 2023.

- ^ Clarke, A. R.; Zalucki, M. P. (2001). "Taeniogonalos raymenti Carmean & Kimsey (Hymenoptera: Trigonalidae) reared as a hyperparasite of Sturmia convergens (Weidemann) (Diptera: Tachinidae), a primary parasite of Danaus plexippus (L.) (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae)". Pan-Pacific Entomologist. 77 (?): 68–70.

- ^ a b Brewer, Jo; Gerard M. Thomas (1966). "Causes of death encountered during rearing of Danaus plexippus (Danaidae)" (PDF). Journal of the Lepidopterists' Society. 20 (4): 235–238. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 25, 2009. Retrieved April 13, 2008.

- ^ a b Stenoien, Carl; McCoshum, Shaun; Caldwell, Wendy; De Anda, Alma; Oberhauser, Karen (January 2015). "New reports that Monarch butterflies (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae, Linnaeus) are hosts for a pupal parasitoid (Hymenoptera: Chalcidoidea, Walker)". Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society. 88 (1): 16–26. doi:10.2317/JKES1402.22.1. S2CID 52231552.

- ^ Leong, K. L. H.; M. A. Yoshimura, H. K. Kaya and H. Williams (1997). "Instar susceptibility of the Monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus) to the neogregarine parasite, Ophryocystis elektroscirrha". Journal of Invertebrate Pathology. 69 (1): 79–83. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.494.9827. doi:10.1006/jipa.1996.4634. PMID 9028932.

- ^ Bartel, Rebecca; Oberhauser, Karen; De Roode, Jacob; Atizer, Sonya (February 2011). "Monarch butterfly migration and parasite transmission in eastern North America". Ecology. 92 (2): 342–351. doi:10.1890/10-0489.1. PMC 7163749. PMID 21618914.

- ^ "Do My Monarch Butterflies Have OE? Ophryocystis elektroscirrha". Butterfly Fun Facts. Retrieved March 24, 2015.

- ^ Jepsen, S.; Schweitzer, D. F.; Young, B.; Sears, N.; Ormes, M.; Black, S. H. (2015). Conservation status and ecology of the monarch butterfly in the United States. NatureServe. pp. 23–24.

- ^ 침입종 경보: 검은제비풀(Cynanchum louisea)과 옅은제비풀(Cynanchum lossicum)이 2021년 9월 16일 웨이백 머신에 보관되었습니다. monarchjointventure.org

- ^ "Monarch Population Hits Lowest Point in More Than 20 Years". Washington, D.C.: World Wildlife Fund. January 29, 2014. Archived from the original on February 25, 2021. Retrieved October 12, 2021.

- ^ "Basic Facts About Monarch Butterflies". January 9, 2020.

- ^ Lemoine, Nathan P. (2015). "Climate Change May Alter Breeding Ground Distributions of Eastern Migratory Monarchs (Danaus plexippus) via Range Expansion of Asclepias Host Plants". PLOS One. 10 (2): e0118614. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1018614L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0118614. PMC 4338007. PMID 25705876.

- ^ "monarchscience". Akdavis6.wixsite.com. August 10, 2015.

- ^ Hahn, Philip G.; Agrawal, Anurag A.; Sussman, Kira I.; Maron, John L. (January 2019). "Population Variation, Environmental Gradients, and the Evolutionary Ecology of Plant Defense against Herbivory". The American Naturalist. 193 (1): 20–34. doi:10.1086/700838. ISSN 1537-5323. PMID 30624107. S2CID 54076888.

- ^ "Climate change, pesticides put monarch butterflies at risk of extinction". National Geographic. December 21, 2018. Archived from the original on December 23, 2018. Retrieved December 31, 2018.

- ^ 사랑하는 왕나비 이제 취약한 동물로 등재, AP < Christina Larson, 2022년 7월 20일

- ^ "Monarch Butterfly". fws.gov.

- ^ Frazin, Rachel (December 15, 2021). "Trump administration punts on protections for monarch butterfly". The Hill. Archived from the original on October 1, 2021. Retrieved October 6, 2021.

The Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) determined that adding the butterfly to the list of threatened and endangered species was "warranted", but that it is unable to do so because it needs to devote its resources to higher-priority species. The FWS said that its "warranted-but-precluded" determination means that every year it will consider adding the butterfly to the list until it decides to propose listing it or determines that protections are not warranted.

- ^ Howard, Elizabeth (February 26, 2016). "Monarch Population Size Announced". Journey North. Archived from the original on February 28, 2016. Retrieved June 6, 2017.

- ^ "Eastern Monarch Population Numbers Drop 27%". News. The Monarch Joint Venture. February 16, 2017. Archived from the original on June 5, 2017. Retrieved June 5, 2017.

- ^ "Where Are All The Monarchs?". Monarch Lab. University of Minnesota Extension. July 14, 2016. Archived from the original on August 22, 2016. Retrieved June 5, 2017.

- ^ "Another monarch study published showing the spring migration holds the key to everything". monarchscience. November 4, 2019. Retrieved December 12, 2019.

- ^ "Monarch". Government of Ontario. Archived from the original on September 12, 2015. Retrieved September 16, 2015.

- ^ "monarchscience". Akdavis6.wixsite.com. December 18, 2016. Retrieved January 12, 2017.

- ^ "Monarchs now listed as an endangered species in Nova Scotia Canada - a prelude for things to come elsewhere". monarchscience. September 30, 2019. Retrieved December 12, 2019.

- ^ Crewe, Tara L.; Mitchell, Greg W.; Larrivée, Maxim (2019). "Size of the Canadian Breeding Population of Monarch Butterflies Is Driven by Factors Acting During Spring Migration and Recolonization". Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution. 7. doi:10.3389/fevo.2019.00308. ISSN 2296-701X.

- ^ Flockhart, D. T. Tyler; Larrivée, Maxim; Prudic, Kathleen L.; Norris, D. Ryan (June 21, 2019). "Estimating the annual distribution of monarch butterflies in Canada over 16 years using citizen science data". FACETS. 4: 238–253. doi:10.1139/facets-2018-0011.

- ^ Obama, President Barack (June 20, 2014). "Presidential Memorandum – Creating a Federal Strategy to Promote the Health of Honey Bees and Other Pollinators". Office of the Press Secretary. Washington, D.C.: The White House. Retrieved May 2, 2018.

- ^ a b Pollinator Health Task Force (May 19, 2015). "National Strategy to Promote the Health of Honey Bees and Other Pollinators" (PDF). Washington, D.C.: The White House. Retrieved May 2, 2018.