약용식물

Medicinal plants

약재라고도 불리는 약용식물은 선사시대부터 전통의학에서 발견되어 사용되어 왔습니다.식물은 곤충, 곰팡이, 질병, 초식 포유동물로부터 방어와 보호를 포함한 다양한 기능을 위해 수백 개의 화학적 화합물을 합성합니다.[2]

허브에 대한 가장 초기의 역사적 기록은 아편을 포함한 수백개의 약용 식물들이 점토판에 기록되어있는 수메르 문명에서 발견됩니다, 기원전 3000년경.고대 이집트의 에버스 파피루스, 기원전 1550년 경에는 850개 이상의 식물 의약품이 묘사되어 있습니다.로마 군대에서 일했던 그리스 의사 디오스코리데스는 데마테리아 메디카, c. 60 AD에 있는 600개 이상의 약용 식물을 사용하여 1000개 이상의 약의 조리법을 기록했습니다; 이것은 약 1500년 동안 약리학의 기초를 형성했습니다.약물 연구는 때때로 약리학적 활성 물질을 찾기 위해 동물학을 이용하고, 이 접근법은 수백 가지 유용한 화합물을 산출해냈습니다.여기에는 아스피린, 디곡신, 퀴닌, 아편 등이 포함됩니다.식물에서 발견되는 화합물들은 다양한데, 대부분은 알칼로이드, 글리코사이드, 폴리페놀, 테르펜의 네 가지 생화학 부류입니다.이 중 과학적으로 의약품으로 확인되거나 기존 의약품에 사용되는 것은 거의 없습니다.

약용식물은 주로 현대의 약보다 쉽게 구할 수 있고 가격이 저렴하기 때문에 비산업화 사회에서 민간약으로 널리 사용됩니다.약효가 있는 수천 종의 식물들의 연간 세계 수출액은 연간 600억 달러로 추산되며, 연간 6%의 성장률을 보이고 있습니다.[citation needed]많은 나라에서 전통적인 의학에 대한 규제는 거의 없지만, 세계보건기구는 안전하고 합리적인 사용을 장려하기 위해 네트워크를 조정합니다.식물성 약초 시장은 그들의 의학적인 주장을 뒷받침할 과학적인 연구가 전혀 없이 위약과 가짜 과학 제품을 포함하고 있고 규제가 허술하다는 비판을 받아왔습니다.[3]약용 식물은 기후 변화와 서식지 파괴와 같은 일반적인 위협과 시장 수요를 충족시키기 위한 과잉 채취라는 특정한 위협에 직면해 있습니다.[3]

역사

선사시대

현재 요리의 허브와 향신료로 사용되는 많은 식물들을 포함한 식물들은 선사시대부터 약으로 사용되어 왔지만, 반드시 효과적인 것은 아닙니다.향신료는 부분적으로 특히 더운 기후, [5][6]특히 더 쉽게 부패하는 고기 요리에서 음식 부패 박테리아에 대항하기 위해 사용되어 왔습니다.[7]대부분의 식물 의약품들은 원래 혈관 속에 들어있는 식물들이었습니다.[8]인간의 정착지는 종종 쐐기풀, 민들레, 병아리풀과 같은 한약재로 쓰이는 잡초들로 둘러싸여 있습니다.[9][10]약초를 약으로 사용하는 것은 인간만이 아니었습니다: 인간이 아닌 영장류, 왕나비, 양과 같은 몇몇 동물들은 아플 때 약용 식물을 먹습니다.[11]선사시대 매장지에서 나온 식물 표본은 구석기시대 사람들이 한약에 대한 지식을 가지고 있었다는 증거들 중의 하나입니다.예를 들어, 이라크 북부에 있는 60,000년 된 네안데르탈인의 매장지인 "샤니다르 4세"에서는 8종의 식물에서 대량의 꽃가루가 배출되었고, 이 중 7종은 현재 약초 치료로 사용되고 있습니다.[12]또한, 5,000년 이상 외츠탈 알프스에 몸이 얼어붙었던 아이스맨 외츠이의 개인 용품에서 버섯이 발견되었습니다.그 버섯은 아마 회충에 사용되었을 것입니다.[13]

태고

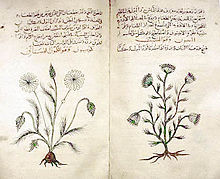

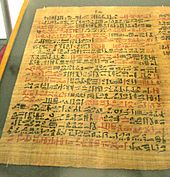

고대 수메르에서는 기원전 3000년경부터 몰약과 아편을 포함한 수백 종의 약용 식물들이 점토판에 기록되어 있습니다.고대 이집트의 에버스 파피루스는 알로에, 대마초, 피마자, 마늘, 향나무, 맨드레이크와 같은 800가지 이상의 식물 의약품을 나열하고 있습니다.[14][15]

고대부터 현재까지, 아타르바 베다, 리그 베다, 수슈루타 삼히타에 기록된 아유르베다 의학은 수백 가지의 약초와 커큐민을 함유한 강황과 같은 향신료를 사용했습니다.[16]중국의 약리학인 선농벤카오징은 나병을 위한 차울무그라, 에페드라, 그리고 대마와 같은 약재들을 심었다고 기록하고 있습니다.[17]이것은 당나라 야흥룬에서 확장되었습니다.[18]기원전 4세기에 아리스토텔레스의 제자 테오프라스토스는 최초의 체계적인 식물학 문헌인 Historia plantarum을 썼습니다.[19]서기 60년경, 로마군을 위해 일하는 그리스 의사 Pedanius Dioscorides는 Demateria medica에 있는 600개 이상의 약용 식물을 사용하여 1000개 이상의 약용 조리법을 기록했습니다.이 책은 17세기까지 1500년이 넘는 기간 동안 약초에 관한 권위 있는 참고 문헌으로 남아있었습니다.[4]

중세

중세 초기에 베네딕토회 수도원들은 고전 텍스트를 번역하고 복사하고 허브 정원을 유지하면서 유럽에서 의학적 지식을 보존했습니다.[20][21]빈겐의 힐데가드는 의학에 관한 "원인과 치료법"을 썼습니다.[22]이슬람 황금기에 학자들은 디오스코리데스를 포함한 많은 고전 그리스 문헌들을 아랍어로 번역하여 그들 자신의 해설을 덧붙였습니다.[23]허브주의는 이슬람 세계, 특히 바그다드와 알안달루스에서 번성했습니다.약용 식물에 관한 많은 작품들 중에, 코르도바의 아불카시스 (936–1013)는 "간편한 책"을 썼고, 이븐 알 바이타르 (1197–1248)는 그의 "간편한 책"에 아코니툼, 누스 보미카, 그리고 타마린드와 같은 수백 가지의 약용 약초들을 기록했습니다.[24]아비세나는 그의 1025년 의전에 많은 식물들을 포함시켰습니다.[25]Abu-Rayhan [26]Biruni, Ibn Zhr,[27] 스페인의 Peter, 그리고 St Amand의 John은 더 많은 약리학을 썼습니다.[28]

얼리 모던

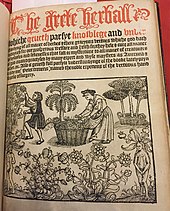

근대 초기에는 1526년 그레테 헤르볼을 시작으로 유럽 전역에서 삽화가 있는 허브들이 번성했습니다.존 제라드는 렘버트 도도엔스를 바탕으로 1597년에 그의 유명한 "식물의 역사"를 썼고, 니콜라스 컬페퍼는 그의 "The English Physician Expanded"를 출판했습니다.[29]15세기와 16세기에 구대륙과 아메리카 대륙 사이에 가축, 농작물, 기술이 이전된 초기 근대 탐험과 콜롬비아 교환의 산물로 많은 새로운 식물 의약품이 유럽에 도착했습니다.아메리카 대륙에 도착한 약초는 마늘, 생강, 강황을 포함했습니다; 커피, 담배, 코카는 다른 방향으로 이동했습니다.[30][31]멕시코에서 16세기의 Badianus 원고는 중앙 아메리카에서 구할 수 있는 약용 식물들을 묘사했습니다.[32]

19세기와 20세기

의학에서 식물의 위치는 19세기에 화학 분석의 적용으로 급격하게 변했습니다.알칼로이드는 1806년 양귀비의 모르핀을 시작으로 곧이어 1817년 이페카쿠안하와 스트리크노스, 신코나 나무의 퀴닌, 그리고 많은 다른 약용 식물들로부터 분리되었습니다.화학이 발전함에 따라, 식물에서 잠재적으로 활성이 있는 물질의 추가적인 부류가 발견되었습니다.모르핀을 포함한 정제된 알칼로이드의 상업적 추출은 1826년 머크에서 시작되었습니다.약용 식물에서 처음 발견된 물질의 합성은 1853년 살리실산으로 시작되었습니다.19세기 말경에는 약용식물에 대한 분위기가 바뀌었는데, 식물을 통째로 말리면 효소가 유효성분을 변형시키는 경우가 많고, 식물물질로 정제한 알칼로이드와 글리코사이드가 선호되기 시작했기 때문입니다.식물에서 나온 약물 발견은 20세기를 거쳐 21세기까지 중요한 것이었으며, 주목과 마다가스카르 페리윙클의 중요한 항암제가 있었습니다.[33][34][35]

맥락

약용식물은 건강을 유지하기 위한 목적으로 사용되며, 특정한 상태를 위해 투여되거나, 현대의학이든 전통의학이든 둘 다 사용됩니다.[3][36]식량 농업 기구는 2002년에 전세계적으로 50,000개 이상의 약용 식물이 사용된다고 추정했습니다.[37]왕립식물원(Royal Botanic Gardens), 큐(Kew)는 2016년에 약용으로 기록된 약 30,000 종의 식물 중 17,810 종의 식물이 약용으로 사용되고 있다고 추정했습니다.[38]

현대 의학에서는 환자에게 처방되는 약의 약 4분의[a] 1 정도가 약용 식물에서 유래하며, 엄격한 검사를 거칩니다.[36][39]의학의 다른 시스템에서, 약용 식물은 과학적으로 실험되지 않고 종종 비공식적으로 시도되는 치료의 대부분을 구성할 수 있습니다.[40]세계보건기구는 세계 인구의 약 80%가 (식물을 포함해서는 안되지만) 전통적인 약에 주로 의존하고 있으며, 약 20억 명의 사람들이 약용 식물에 크게 의존하고 있는 것으로 추정하고 있습니다.[36][39]선진국에서 건강상의 이점이 있다고 추정되는 허브 또는 천연 건강 제품을 포함한 식물 기반 재료의 사용이 증가하고 있습니다.[41]이것은 안전한 한약재의 이미지에도 불구하고 독성과 다른 영향을 동반하는 위험을 초래합니다.[41]한약은 현대 의학이 존재하기 훨씬 전부터 사용되어 왔습니다; 그것들의 작용의 약리학적 기초에 대한 지식이 거의 없었고, 만일 있다면, 그것들의 안전성에 대한 지식도 거의 없었습니다.세계보건기구는 1991년에 전통의학에 관한 정책을 세웠고, 그 이후로 널리 사용되는 한약에 관한 일련의 논문과 함께 그들을 위한 지침을 발표했습니다.[42][43]

약용 식물은 약으로 소비하는 사람들에게 건강상의 이점을 제공할 수도 있습니다: 약용 식물을 소비하는 사람들에게 건강상의 이점, 판매를 위해 수확하고 가공하고 분배하는 사람들에게 경제적인 이점, 그리고 직업 기회, 세금 수입, 그리고 더 건강한 노동력과 같은 사회적인 이점.[36]그러나, 약학적으로 사용 가능성이 있는 식물이나 추출물의 개발은 약한 과학적 증거, 약물 개발 과정에서의 잘못된 관행, 그리고 불충분한 자금 조달로 인해 무뎌집니다.[3]

물리화학적 기저

모든 식물은 초식동물이나 살리실산의 예와 같이 식물 방어의 호르몬으로서 그들에게 진화론적인 이점을 주는 화학적 화합물을 생산합니다.[44][45]이러한 파이토케미컬은 약물로 사용될 가능성이 있으며, 과학적으로 확인된다면, 약용 식물에서 이러한 물질의 함량과 알려진 약리학적 활성은 현대 의학에서의 사용에 대한 과학적 근거가 됩니다.[3]예를 들어 수선화(나르시서스)는 알츠하이머병에 대한 사용 허가를 받은 갈란타민을 포함한 9개의 알칼로이드 그룹을 포함하고 있습니다.알칼로이드는 쓴 맛이 나고 독성이 있으며 초식동물이 먹을 가능성이 가장 높은 줄기와 같은 식물의 일부에 집중되어 있습니다. 기생충으로부터 보호할 수도 있습니다.[46][47][48]

약용식물에 대한 현대적인 지식은 약용식물 전사체 데이터베이스에 체계화되고 있으며, 2011년까지 약 30종의 전사체에 대한 서열 참조를 제공했습니다.[49]식물성 식물 화학 물질의 주요 분류는 아래에 설명되어 있으며, 이를 포함하는 식물의 예를 들어 설명합니다.[8][43][50][51][52]

알칼로이드

알칼로이드는 쓴 맛이 나는 화학물질로, 자연에 매우 널리 퍼져 있고 종종 독성이 있으며 많은 약용 식물에서 발견됩니다.[53]오락용 및 제약용으로 다양한 작용 방식을 가진 여러 부류의 약물이 있습니다.다른 부류의 약은 아트로핀, 스코폴라민, 히오스시아민(모두 밤 그늘에서 나온 것),[54] 전통적인 약인 베르베린(베르베리스와 마호니아와 같은 식물에서 나온 것),[b] 카페인(커피), 코카인(코카), 에페드린(에페드라), 모르핀(양귀비 오피움), 니코틴(담배),[c] 레세르핀(라우볼피아 스펜디나), 퀴니딘(신초나),빈카민(빈카미노)[52][57]과 빈크리스틴(카타란투스 로제우스).

-

담배에서 나오는 알칼로이드 니코틴은 몸의 니코틴성 아세틸콜린 수용체에 직접적으로 결합하여 약리학적 효과를 설명합니다.[58]

글리코사이드

안트라퀴논 글리코사이드는 대황, 카스카라, 알렉산드리아 세나와 같은 약용 식물에서 발견됩니다.[59][60]이런 식물로 만든 식물성 완하제로는 세나,[61] 대황[62], 알로에 등이 있습니다.[52]

심장 글리코사이드는 계곡의 폭스글러브와 백합을 포함한 약용식물에서 나오는 강력한 약물입니다.그것들은 심장의 박동을 지원하고 이뇨제 역할을 하는 디곡신과 디곡신을 포함합니다.[44]

-

안트라퀴논 글리코사이드를 함유한 세나 알렉산드리나는 수천 년 동안 완하제로 사용되어 왔습니다.[61]

폴리페놀

여러 종류의 폴리페놀은 식물에 널리 퍼져 있으며 식물 질병과 포식자에 대한 방어에 다양한 역할을 합니다.[44]그것들은 호르몬을 모방하는 피토에스트로겐과 떫은 타닌을 포함합니다.[52][64]식물성 에스트로겐을 함유한 식물은 수세기 전부터 생식력, 생리, 갱년기 문제와 같은 부인과 질환에 투여되어 왔습니다.[65]이 식물들 중에는 푸에라리아 미리카,[66] 쿠즈,[67] 당귀,[68] 회향나무, 아니스가 있습니다.[69]

포도씨, 올리브 또는 해상 소나무 껍질과 같은 많은 폴리페놀 추출물은 약효에 대한 증명이나 법적 건강 주장 없이 식이 보충제 및 화장품으로 판매됩니다.[70]아유르베다에서는 포니칼라진이라고 불리는 폴리페놀을 함유한 석류의 떫은 껍질이 약으로 사용되는데, 효과에 대한 과학적인 증거는 없습니다.[70][71]

테르펜

다양한 종류의 테르펜과 테르페노이드는 다양한 약용 식물과 [73]침엽수와 같은 수지가 많은 식물에서 발견됩니다.향이 강하고 초식동물을 쫓아내는 역할을 합니다.그것들의 향은 장미나 라벤더와 같은 향수나 아로마테라피에 쓰이던 필수 오일에 유용하게 만들어줍니다.[52][74][75]일부는 의학적 용도를 가지고 있습니다: 예를 들어, 티몰은 방부제이며 한때 해충 구제제로 사용되기도 했습니다.[76]

실무상

재배

약용식물은 집중적인 관리가 필요합니다.다른 종들은 각각 그들만의 독특한 재배 조건을 필요로 합니다.세계보건기구는 병해충과 식물 질병의 문제를 최소화하기 위해 순환을 사용할 것을 권장합니다.경작은 전통적이거나 토양의 유기물을 유지하고 예를 들어 무경작 시스템과 같은 물을 보존하기 위해 보존 농업 관행을 이용할 수 있습니다.[77]많은 약용식물과 방향식물에서 식물의 특성은 토양의 종류와 작목 전략에 따라 매우 다양하기 때문에 만족스러운 수확량을 얻기 위해서는 주의가 필요합니다.[78]

준비

약용 식물은 종종 질기고 섬유질이 많아서, 투여하기 편리하도록 만들기 위해 어떤 형태로든 준비가 필요합니다.전통의학연구소에 따르면 한약재 제조를 위한 일반적인 방법은 알코올로 해독, 분말화, 추출하는 것이며, 각각의 경우 물질이 혼합된 것을 산출합니다.해독은 식물 재료를 분쇄한 다음 물에 끓여서 경구 또는 국소적으로 사용할 수 있는 액체 추출물을 생성하는 것을 포함합니다.[79]가루를 만드는 것은 식물 재료를 건조시킨 다음 분쇄하여 정제로 압축할 수 있는 가루를 만드는 것을 포함합니다.알코올 추출은 식물 재료를 차가운 와인이나 증류된 증류주에 담그어 팅크를 형성하는 것을 포함합니다.[80]

전통 찜질은 약용 식물을 삶아 천에 싸서 환부에 외부에 바르는 방식으로 만들어졌습니다.[81]

현대 의학이 약용 식물에서 약물을 발견했을 때, 그 약물의 상업적인 양은 합성되거나 식물 물질로부터 추출되어 순수한 화학물질을 생산할 수 있습니다.[33]추출은 해당 화합물이 복잡할 때 실용적일 수 있습니다.[82]

사용.

식물성 의약품은 전세계적으로 널리 사용되고 있습니다.[83]개발도상국 대부분, 특히 농촌에서는 약초를 포함한 지역 전통의학이 사람들의 건강관리의 유일한 원천인 반면, 선진국에서는 전통의학의 주장을 이용하여 식이보충제 사용을 포함한 대체의학이 공격적으로 마케팅되고 있습니다.2015년 현재 약용식물로 만든 대부분의 제품들은 안전성과 효능에 대한 시험이 이루어지지 않았고, 선진국에서 시판되고 전통적인 치료자들에 의해 개발되지 않은 세계에서 제공되는 제품들은 품질이 고르지 않았으며, 때로는 위험한 오염물질을 포함하고 있었습니다.[84]전통적인 한의학은 여러 가지 재료와 기술 중에서도 다양한 식물을 사용합니다.[85]큐 가든스(Kew Gardens)의 연구원들은 중앙 아메리카에서 당뇨병에 사용되는 104종을 발견했으며, 이 중 7종은 적어도 3개의 다른 연구에서 확인되었습니다.[86][87]브라질 아마존의 야노마미는 연구원들의 도움을 받아 전통적인 약재로 사용되는 101종의 식물을 묘사했습니다.[88][89]

아편, 코카인, 대마초를 포함한 식물에서 유래된 약물은 의학적 용도와 오락적 용도를 모두 가지고 있습니다.다른 나라들은 다양한 시기에 불법 약물을 사용해왔는데, 부분적으로는 정신 활동성 약물을 복용하는 것과 관련된 위험에 근거했습니다.[90]

유효성

식물성 의약품은 종종 체계적으로 시험되지는 않았지만 수세기에 걸쳐 비공식적으로 사용되기 시작했습니다.2007년까지, 임상 시험은 거의 16%의 허브 추출물에서 잠재적으로 유용한 활성을 입증했습니다. 대략 절반의 추출물에 대한 제한된 체외 또는 생체 내 증거가 있었습니다. 약 20%에 대한 식물화학적 증거만 있었고, 0.5%는 알레르기성 또는 독성이 있었으며, 약 12%는 기본적으로 과학적으로 연구된 적이 없었습니다.[43]암 연구 영국은 암에 대한 약초 요법의 효과에 대한 확실한 증거가 없다고 경고합니다.[91]

2012년 계통발생학 연구에서는 네팔, 뉴질랜드, 남아프리카 공화국 곶 등 3개 지역의 약용식물을 비교하기 위해 20,000여 종을 사용하여 계통수를 속 단위로 낮췄습니다.그것은 전통적으로 같은 종류의 병을 치료하기 위해 사용되는 종들이 세 지역 모두에서 같은 그룹의 식물에 속한다는 것을 발견했고, "강력한 계통발생학적 신호"를 주었습니다.[92]의약품을 생산하는 많은 식물들이 단지 이들 그룹에 속하고, 그 그룹들이 세 개의 다른 세계 지역에서 독립적으로 사용되었기 때문에, 그 결과는 1) 이러한 식물 그룹들이 약효에 대한 잠재력을 가지고 있다는 것, 2) 정의되지 않은 약리학적 활동이 전통적인 의학에서의 사용과 관련이 있다는 것,그리고 3) 한 지역에서 발생 가능한 식물 의약품에 대한 계통발생학적 그룹의 사용이 다른 지역에서의 사용을 예측할 수 있음.[92]

규정

세계보건기구(WHO)는 약용 식물로 만든 의료 제품의 품질과 그에 대한 주장을 개선하기 위해 국제 약초 규제 협력이라고 불리는 네트워크를 조정해 왔습니다.[93]2015년에는 약 20%의 국가만이 제 기능을 하는 규제 기관을 보유하고 있었고, 30%는 규제 기관을 보유하고 있지 않았으며, 약 절반은 규제 능력이 제한적이었습니다.[84]아유르베다가 수세기 동안 행해져 온 인도에서, 약초 치료는 보건 가족 복지부 산하의 정부 부처인 AYUSH의 책임입니다.[94]

WHO는 전통적인 의약품에[95] 대한 전략을 네 가지 목표로 설정했습니다. 정책적으로 국가 의료 시스템에 통합하는 것, 안전성, 효능, 품질에 대한 지식과 지침을 제공하는 것, 의약품의 가용성과 경제성을 높이는 것, 그리고 합리적이고 치료적으로 건전한 사용을 촉진하는 것입니다.[95]WHO는 이 전략에서 국가들이 정책 개발 및 집행, 통합, 안전 및 품질 등과 같은 7가지 과제를 경험하고 있다고 언급했습니다.특히 제품의 평가와 실무자의 자격, 광고 통제, 연구 개발, 교육 및 훈련, 정보 공유에 있어서.[95]

약물 발견

제약 산업은 1800년대 유럽의 약국에 뿌리를 두고 있으며, 그곳에서 약사들은 모르핀, 퀴닌, 스트리크닌과 같은 추출물을 포함한 지역 전통 의약품을 고객들에게 제공했습니다.[96]치료상 중요한 약물인 캄토테신(중국 전통 의학에 사용되는 캄토테카 아쿠미나타)과 택솔(태평양산 주목, 택서스 브레비폴리아)은 약용 식물에서 유래되었습니다.[97][33]항암제로 쓰이는 빈카 알칼로이드 빈크리스틴과 빈블라스틴은 1950년대에 마다가스카르 섬의 페리윙클(Catharanthus roseus)에서 발견되었습니다.[98]

토착민들이 사용할 수 있는 의학적 응용을 위해 식물을 조사하면서 수백 가지 화합물이 인류 식물학을 사용하여 확인되었습니다.[99]커큐민, 에피갈로카테킨 갈레이트, 제니스테인 및 레스베라트롤을 포함한 일부 중요한 파이토케미컬은 범-분석 간섭 화합물이며, 이는 그들의 활동에 대한 시험관 내 연구가 종종 신뢰할 수 없는 데이터를 제공한다는 것을 의미합니다.그 결과, 파이토케미컬은 약물 발견의 주요 물질로서 종종 부적합한 것으로 입증되었습니다.[100][101]1999년부터 2012년까지 미국에서는 수백 건의 신약 신청에도 불구하고 오직 두 건의 식물성 의약품 후보만이 미국 식품의약국의 승인을 받기에 충분한 의학적 가치의 증거를 가지고 있었습니다.[3]

제약업계는 의약품 발굴 노력에서 전통적인 약용 식물의 채굴에 관심을 가지고 있습니다.[33]1981년에서 2010년 사이에 승인된 1073개의 소분자 약물 중 절반 이상이 천연 물질로부터 직접 유래되었거나 영감을 받았습니다.[33][102]암 치료제 중 1981년부터 2019년까지 허가받은 185개 소분자 약물 중 65%가 천연물질에서 유래했거나 영감을 받은 것으로 나타났습니다.[103]

안전.

식물성 의약품은 활성 물질의 부작용에 의해서든, 간음이나 오염에 의해서든, 과다 복용에 의해서든, 또는 부적절한 처방에 의해서든 부작용과 심지어 죽음을 초래할 수 있습니다.많은 그러한 효과들이 알려져 있는 반면, 다른 효과들은 과학적으로 연구되어야 합니다.제품은 자연에서 나오기 때문에 안전해야 한다고 추정할 이유가 없습니다. 아트로핀과 니코틴과 같은 강력한 자연 독성의 존재는 이것이 사실이 아니라는 것을 보여줍니다.또한, 기존의 의약품에 적용되는 높은 기준이 항상 식물 의약품에 적용되는 것은 아니며, 용량은 식물의 성장 조건에 따라 매우 다양할 수 있습니다: 예를 들어, 오래된 식물이 어린 식물보다 훨씬 더 독성이 강할 수 있습니다.[105][106][107][108][109][110]

식물 추출물은 유사한 화합물의 증가된 용량을 제공할 수도 있고, 일부 파이토케미컬이 사이토크롬 P450 시스템을 포함하여 간에서 약물을 대사하는 신체의 시스템을 방해하여 약물이 신체에서 더 오래 지속되고 누적된 효과를 가질 수 있기 때문에 기존 약물과 상호 작용할 수도 있습니다.[111]임신 중에는 식물성 약이 위험할 수 있습니다.[112]식물은 많은 다른 물질을 함유하고 있을 수도 있기 때문에, 식물 추출물은 인체에 복합적인 영향을 끼칠 수도 있습니다.[5]

품질, 광고 및 라벨링

한약재와 식이보충제 제품은 그 함량과 안전성, 추정 효능 등을 확인할 수 있는 충분한 기준이나 과학적 근거가 없다는 지적을 받아왔습니다.[113][114][115][116]2013년의 한 연구에 따르면 표본 추출된 허브 제품의 3분의 1은 라벨에 나열된 허브의 흔적이 없으며, 다른 제품들은 잠재적인 알레르기 유발 물질을 포함한 목록에 없는 충전제와 섞였습니다.[117][118]회사들은 종종 더 많은 매출을 창출할 수 있는 증거가 뒷받침되지 않은 건강상의 이점을 약속하는 약초 제품에 대해 거짓 주장을 합니다.코로나19 팬데믹 기간 동안 건강보조식품과 영양제 시장은 5% 성장했고, 이로 인해 미국은 바이러스 퇴치를 위한 허브 제품의 기만적인 마케팅을 중단하기 위해 조치를 취했습니다.[119][120]

위협

약용식물을 재배하는 것이 아니라 야생에서 수확하는 경우에는 일반적인 위협과 특정한 위협을 모두 받게 됩니다.일반적인 위협은 기후 변화와 개발과 농업에 대한 서식지 손실을 포함합니다.특정한 위협은 증가하는 의약품 수요를 충족시키기 위한 과도한 수집입니다.[121]택솔의 효능 소식이 알려진 직후 태평양 주목의 야생 개체수에 대한 압박이 대표적인 예입니다.[33]과도한 채집으로 인한 위협은 일부 약용 식물을 재배하거나 야생 수확을 지속 가능하게 하는 인증 제도에 의해 해결될 수 있습니다.[121]왕립 식물원의 2020년 보고서에 따르면 큐는 723개의 약용 식물이 부분적으로 과잉 채취로 인해 멸종될 위험에 처해 있다고 합니다.[122][103]

참고 항목

메모들

- ^ 판스워스는 이 수치가 1959년에서 1980년 사이에 미국 지역 약국들의 처방전에 근거한 것이라고 말합니다.[39]

- ^ 베르베린은 고대 중국 약초 Coptis chinensis French의 주요 활성 성분으로, 비록 효과에 대한 확실한 증거는 없지만, Yin과 동료들이 말하는 "당뇨병"을 위해 수천 년 동안 투여되어 왔습니다.[55]

- ^ 담배는 "다른 어떤 약초보다 더 많은 죽음에 책임이 있을 것"이지만, 콜럼버스가 접한 사회에서는 약으로 사용되었고 유럽에서는 만병통치약으로 여겨졌습니다.그것은 더이상 약으로 받아들여지지 않습니다.[56]

참고문헌

- ^ Lichterman, B. L. (2004). "Aspirin: The Story of a Wonder Drug". British Medical Journal. 329 (7479): 1408. doi:10.1136/bmj.329.7479.1408. PMC 535471.

- ^ Gershenzon J, Ullah C (January 2022). "Plants protect themselves from herbivores by optimizing the distribution of chemical defenses". Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 119 (4). Bibcode:2022PNAS..11920277G. doi:10.1073/pnas.2120277119. PMC 8794845. PMID 35084361.

- ^ a b c d e f Ahn, K. (2017). "The worldwide trend of using botanical drugs and strategies for developing global drugs". BMB Reports. 50 (3): 111–116. doi:10.5483/BMBRep.2017.50.3.221. PMC 5422022. PMID 27998396.

- ^ a b Collins, Minta (2000). Medieval Herbals: The Illustrative Traditions. University of Toronto Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-8020-8313-5.

- ^ a b Tapsell, L. C.; Hemphill, I.; Cobiac, L.; et al. (August 2006). "Health benefits of herbs and spices: the past, the present, the future". Med. J. Aust. 185 (4 Suppl): S4–24. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2006.tb00548.x. PMID 17022438. S2CID 9769230. Archived from the original on 2020-10-31. Retrieved 2020-08-27.

- ^ Billing, Jennifer; Sherman, P. W. (March 1998). "Antimicrobial functions of spices: why some like it hot". Quarterly Review of Biology. 73 (1): 3–49. doi:10.1086/420058. PMID 9586227. S2CID 22420170.

- ^ Sherman, P. W.; Hash, G. A. (May 2001). "Why vegetable recipes are not very spicy". Evolution and Human Behavior. 22 (3): 147–163. doi:10.1016/S1090-5138(00)00068-4. PMID 11384883.

- ^ a b "Angiosperms: Division Magnoliophyta: General Features". Encyclopædia Britannica (volume 13, 15th edition). 1993. p. 609.

- ^ Stepp, John R. (June 2004). "The role of weeds as sources of pharmaceuticals". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 92 (2–3): 163–166. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2004.03.002. PMID 15137997.

- ^ Stepp, John R.; Moerman, Daniel E. (April 2001). "The importance of weeds in ethnopharmacology". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 75 (1): 19–23. doi:10.1016/S0378-8741(00)00385-8. PMID 11282438.

- ^ Sumner, Judith (2000). The Natural History of Medicinal Plants. Timber Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-88192-483-1.

- ^ Solecki, Ralph S. (November 1975). "Shanidar IV, a Neanderthal Flower Burial in Northern Iraq". Science. 190 (4217): 880–881. Bibcode:1975Sci...190..880S. doi:10.1126/science.190.4217.880. S2CID 71625677.

- ^ Capasso, L. (December 1998). "5300 years ago, the Ice Man used natural laxatives and antibiotics". Lancet. 352 (9143): 1864. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)79939-6. PMID 9851424. S2CID 40027370.

- ^ a b Sumner, Judith (2000). The Natural History of Medicinal Plants. Timber Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-88192-483-1.

- ^ Petrovska 2012, pp. 1-5.

- ^ Dwivedi, Girish; Dwivedi, Shridhar (2007). History of Medicine: Sushruta – the Clinician – Teacher par Excellence (PDF). National Informatics Centre. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 October 2008. Retrieved 8 October 2008.

- ^ Sumner, Judith (2000). The Natural History of Medicinal Plants. Timber Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-88192-483-1.

- ^ Wu, Jing-Nuan (2005). An Illustrated Chinese Materia Medica. Oxford University Press. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-19-514017-0.

- ^ Grene, Marjorie (2004). The philosophy of biology: an episodic history. Cambridge University Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-521-64380-1.

- ^ Arsdall, Anne V. (2002). Medieval Herbal Remedies: The Old English Herbarium and Anglo-Saxon Medicine. Psychology Press. pp. 70–71. ISBN 978-0-415-93849-5.

- ^ Mills, Frank A. (2000). "Botany". In Johnston, William M. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Monasticism: M-Z. Taylor & Francis. p. 179. ISBN 978-1-57958-090-2.

- ^ Ramos-e-Silva Marcia (1999). "Saint Hildegard Von Bingen (1098–1179) "The Light Of Her People And Of Her Time"". International Journal of Dermatology. 38 (4): 315–320. doi:10.1046/j.1365-4362.1999.00617.x. PMID 10321953. S2CID 13404562.

- ^ Castleman, Michael (2001). The New Healing Herbs. Rodale. p. 15. ISBN 978-1-57954-304-4.Castleman, Michael (2001). The New Healing Herbs. Rodale. p. 15. ISBN 978-1-57954-304-4.; ; ; ,Fahd, Toufic. Botany and agriculture. p. 815. in

- ^ Castleman, Michael (2001). The New Healing Herbs. Rodale. p. 15. ISBN 978-1-57954-304-4.

- ^ Jacquart, Danielle (2008). "Islamic Pharmacology in the Middle Ages: Theories and Substances". European Review. 16 (2): 219–227 [223]. doi:10.1017/S1062798708000215.

- ^ Kujundzić, E.; Masić, I. (1999). "[Al-Biruni--a universal scientist]". Med. Arh. (in Croatian). 53 (2): 117–120. PMID 10386051.

- ^ Krek, M. (1979). "The Enigma of the First Arabic Book Printed from Movable Type". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 38 (3): 203–212. doi:10.1086/372742. S2CID 162374182.

- ^ Brater, D. Craig; Daly, Walter J. (2000). "Clinical pharmacology in the Middle Ages: Principles that presage the 21st century". Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 67 (5): 447–450 [448–449]. doi:10.1067/mcp.2000.106465. PMID 10824622. S2CID 45980791.

- ^ a b Singer, Charles (1923). "Herbals". The Edinburgh Review. 237: 95–112.

- ^ Nunn, Nathan; Qian, Nancy (2010). "The Columbian Exchange: A History of Disease, Food, and Ideas". Journal of Economic Perspectives. 24 (2): 163–188. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.232.9242. doi:10.1257/jep.24.2.163. JSTOR 25703506.

- ^ Heywood, Vernon H. (2012). "The role of New World biodiversity in the transformation of Mediterranean landscapes and culture" (PDF). Bocconea. 24: 69–93. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-02-27. Retrieved 2017-02-26.

- ^ Gimmel Millie (2008). "Reading Medicine In The Codex De La Cruz Badiano". Journal of the History of Ideas. 69 (2): 169–192. doi:10.1353/jhi.2008.0017. PMID 19127831. S2CID 46457797.

- ^ a b c d e f Atanasov, Atanas G.; Waltenberger, Birgit; Pferschy-Wenzig, Eva-Maria; et al. (December 2015). "Discovery and resupply of pharmacologically active plant-derived natural products: A review". Biotechnology Advances. 33 (8): 1582–1614. doi:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2015.08.001. PMC 4748402. PMID 26281720.

- ^ Petrovska, Biljana Bauer (2012). "Historical review of medicinal plants' usage". Pharmacognosy Reviews. 6 (11): 1–5. doi:10.4103/0973-7847.95849. PMC 3358962. PMID 22654398.

- ^ Price, J. R.; Lamberton, J. A.; Culvenor, C.C.J (1992), "The Australian Phytochemical Survey: historical aspects of the CSIRO search for new drugs in Australian plants. Historical Records of Australian Science, 9(4), 335–356", Historical Records of Australian Science, Australian Academy of Science, 9 (4): 335–356, doi:10.1071/hr9930940335, archived from the original on 2022-01-21, retrieved 2022-04-02

- ^ a b c d Smith-Hall, C.; Larsen, H.O.; Pouliot, M. (2012). "People, plants and health: a conceptual framework for assessing changes in medicinal plant consumption". J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 8: 43. doi:10.1186/1746-4269-8-43. PMC 3549945. PMID 23148504.

- ^ Schippmann, Uwe; Leaman, Danna J.; Cunningham, A. B. (12 October 2002). "Impact of Cultivation and Gathering of Medicinal Plants on Biodiversity: Global Trends and Issues 2. Some Figures to start with ..." Biodiversity and the Ecosystem Approach in Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. Satellite event on the occasion of the Ninth Regular Session of the Commission on Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture. Rome, 12–13 October 2002. Inter-Departmental Working Group on Biological Diversity for Food and Agriculture. Rome. Food and Agriculture Organization. Archived from the original on 24 July 2017. Retrieved 25 September 2017.

- ^ "State of the World's Plants Report - 2016" (PDF). Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 September 2017. Retrieved 25 September 2017.

- ^ a b c Farnsworth, Norman R.; Akerele, Olayiwola; Bingel, Audrey S.; Soejarto, Djada D.; Guo, Zhengang (1985). "Medicinal plants in therapy". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 63 (6): 965–981. PMC 2536466. PMID 3879679.

- ^ Tilburt, Jon C.; Kaptchuk, Ted J. (August 2008). "Herbal medicine research and global health: an ethical analysis". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 86 (8): 577–656. doi:10.2471/BLT.07.042820. PMC 2649468. PMID 18797616. Archived from the original on January 24, 2010. Retrieved 22 September 2017.

- ^ a b Ekor, Martins (2013). "The growing use of herbal medicines: issues relating to adverse reactions and challenges in monitoring safety". Frontiers in Pharmacology. 4 (3): 202–4. doi:10.3389/fphar.2013.00177. PMC 3887317. PMID 24454289.

- ^ Singh, Amritpal (2016). Regulatory and Pharmacological Basis of Ayurvedic Formulations. CRC Press. pp. 4–5. ISBN 978-1-4987-5096-7.

- ^ a b c Cravotto, G.; Boffa, L.; Genzini, L.; Garella, D. (February 2010). "Phytotherapeutics: an evaluation of the potential of 1000 plants". Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics. 35 (1): 11–48. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2710.2009.01096.x. PMID 20175810. S2CID 29427595.

- ^ a b c d e "Active Plant Ingredients Used for Medicinal Purposes". United States Department of Agriculture. Archived from the original on 12 July 2018. Retrieved 18 February 2017.

Below are several examples of active plant ingredients that provide medicinal plant uses for humans.

- ^ Hayat, S. & Ahmad, A. (2007). Salicylic Acid – A Plant Hormone. Springer Science and Business Media. ISBN 978-1-4020-5183-8.

- ^ Bastida, Jaume; Lavilla, Rodolfo; Viladomat, Francesc Viladomat (2006). "Chemical and Biological Aspects of Narcissus Alkaloids". In Cordell, G. A. (ed.). The Alkaloids: Chemistry and Biology. Vol. 63. pp. 87–179. doi:10.1016/S1099-4831(06)63003-4. ISBN 978-0-12-469563-4. PMC 7118783. PMID 17133715.

- ^ "Galantamine". Drugs.com. 2017. Archived from the original on 14 October 2018. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- ^ Birks, J. (2006). Birks, Jacqueline S (ed.). "Cholinesterase inhibitors for Alzheimer's disease". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016 (1): CD005593. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005593. PMC 9006343. PMID 16437532.

- ^ Soejarto, D. D. (1 March 2011). "Transcriptome Characterization, Sequencing, And Assembly Of Medicinal Plants Relevant To Human Health". University of Illinois at Chicago. Archived from the original on 20 April 2017. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

- ^ Meskin, Mark S. (2002). Phytochemicals in Nutrition and Health. CRC Press. p. 123. ISBN 978-1-58716-083-7.

- ^ Springbob, Karen; Kutchan, Toni M. (2009). "Introduction to the different classes of natural products". In Lanzotti, Virginia (ed.). Plant-Derived Natural Products: Synthesis, Function, and Application. Springer. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-387-85497-7.

- ^ a b c d e f Elumalai, A.; Eswariah, M. Chinna (2012). "Herbalism - A Review" (PDF). International Journal of Phytotherapy. 2 (2): 96–105. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-02-17. Retrieved 2017-02-17.

- ^ Aniszewski, Tadeusz (2007). Alkaloids – secrets of life. Amsterdam: Elsevier. p. 182. ISBN 978-0-444-52736-3.

- ^ a b "Atropa Belladonna" (PDF). The European Agency for the Evaluation of Medicinal Products. 1998. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 April 2018. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- ^ Yin, Jun; Xing, Huili; Ye, Jianping (May 2008). "Efficacy of Berberine in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes". Metabolism. 57 (5): 712–717. doi:10.1016/j.metabol.2008.01.013. PMC 2410097. PMID 18442638.

- ^ Charlton, Anne (June 2004). "Medicinal uses of tobacco in history". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 97 (6): 292–296. doi:10.1177/014107680409700614. PMC 1079499. PMID 15173337.

- ^ Gremigni, P.; et al. (2003). "The interaction of phosphorus and potassium with seed alkaloid concentrations, yield and mineral content in narrow-leafed lupin (Lupinus angustifolius L.)". Plant and Soil. 253 (2): 413–427. doi:10.1023/A:1024828131581. JSTOR 24121197. S2CID 25434984.

- ^ "Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: Introduction". IUPHAR Database. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. Archived from the original on 29 June 2017. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- ^ Wang, Zhe; Ma, Pei; He, Chunnian; Peng, Yong; Xiao, Peigen (2013). "Evaluation of the content variation of anthraquinone glycosides in rhubarb by UPLC-PDA". Chemistry Central Journal. 7 (1): 43–56. doi:10.1186/1752-153X-7-170. PMC 3854541. PMID 24160332.

- ^ Chan, K.; Lin, T.X. (2009). Treatments used in complementary and alternative medicine. Side Effects of Drugs Annual. Vol. 31. pp. 745–756. doi:10.1016/S0378-6080(09)03148-1. ISBN 978-0-444-53294-7.

- ^ a b Hietala, P.; Marvola, M.; Parviainen, T.; Lainonen, H. (August 1987). "Laxative potency and acute toxicity of some anthraquinone derivatives, senna extracts and fractions of senna extracts". Pharmacology & Toxicology. 61 (2): 153–6. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0773.1987.tb01794.x. PMID 3671329.

- ^ Akolkar, Praful (2012-12-27). "Pharmacognosy of Rhubarb". PharmaXChange.info. Archived from the original on 2015-06-26. Retrieved 2017-02-02.

- ^ "Digitalis purpurea. Cardiac Glycoside". Texas A&M University. Archived from the original on 2 July 2018. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

The man credited with the introduction of digitalis into the practice of medicine was William Withering.

- ^ Da Silva, Cecilia; et al. (2013). "The High Polyphenol Content of Grapevine Cultivar Tannat Berries Is Conferred Primarily by Genes That Are Not Shared with the Reference Genome". The Plant Cell. 25 (12): 4777–4788. doi:10.1105/tpc.113.118810. JSTOR 43190600. PMC 3903987. PMID 24319081.

- ^ Muller-Schwarze, Dietland (2006). Chemical Ecology of Vertebrates. Cambridge University Press. p. 287. ISBN 978-0-521-36377-8.

- ^ Lee, Y. S.; Park J. S.; Cho S. D.; Son J. K.; Cherdshewasart W.; Kang K. S. (Dec 2002). "Requirement of metabolic activation for estrogenic activity of Pueraria mirifica". Journal of Veterinary Science. 3 (4): 273–277. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.617.1507. doi:10.4142/jvs.2002.3.4.273. PMID 12819377. Archived from the original on 2019-04-19. Retrieved 2019-04-19.

- ^ Delmonte, P.; Rader, J. I. (2006). "Analysis of isoflavones in foods and dietary supplements". Journal of AOAC International. 89 (4): 1138–46. doi:10.1093/jaoac/89.4.1138. PMID 16915857.

- ^ Brown, D.E.; Walton, N. J. (1999). Chemicals from Plants: Perspectives on Plant Secondary Products. World Scientific Publishing. pp. 21, 141. ISBN 978-981-02-2773-9.

- ^ Albert-Puleo, M. (Dec 1980). "Fennel and anise as estrogenic agents". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2 (4): 337–44. doi:10.1016/S0378-8741(80)81015-4. PMID 6999244.

- ^ a b European Food Safety Authority (2010). "Scientific Opinion on the substantiation of health claims related to various food(s)/food constituent(s) and protection of cells from premature aging, antioxidant activity, antioxidant content and antioxidant properties, and protection of DNA, proteins and lipids from oxidative damage pursuant to Article 13(1) of Regulation (EC) No 1924/20061". EFSA Journal. 8 (2): 1489. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2010.1489.

- ^ Jindal, K. K.; Sharma, R. C. (2004). Recent trends in horticulture in the Himalayas. Indus Publishing. ISBN 978-81-7387-162-7.

- ^ Turner, J. V.; Agatonovic-Kustrin, S.; Glass, B. D. (August 2007). "Molecular aspects of phytoestrogen selective binding at estrogen receptors". Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 96 (8): 1879–85. doi:10.1002/jps.20987. PMID 17518366.

- ^ Wiart, Christopher (2014). "Terpenes". Lead Compounds from Medicinal Plants for the Treatment of Neurodegenerative Diseases. Elsevier Inc. pp. 189–284. doi:10.1016/C2011-0-09611-4. ISBN 978-0-12-398373-2.

- ^ Tchen, T. T. (1965). "The Biosynthesis of Steroids, Terpenes and Acetogenins". American Scientist. 53 (4): 499A–500A. JSTOR 27836252.

- ^ Singsaas, Eric L. (2000). "Terpenes and the Thermotolerance of Photosynthesis". New Phytologist. 146 (1): 1–2. doi:10.1046/j.1469-8137.2000.00626.x. JSTOR 2588737.

- ^ a b c "Thymol (CID=6989)". NIH. Archived from the original on 12 July 2018. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

THYMOL is a phenol obtained from thyme oil or other volatile oils used as a stabilizer in pharmaceutical preparations, and as an antiseptic (antibacterial or antifungal) agent. It was formerly used as a vermifuge.

- ^ "WHO Guidelines on Good Agricultural and Collection Practices (GACP) for Medicinal Plants". World Health Organization. 2003. Archived from the original on October 20, 2009. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- ^ Carrubba, A.; Scalenghe, R. (2012). "Scent of Mare Nostrum ― Medicinal and Aromatic Plants (MAPs) in Mediterranean soils". Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 92 (6): 1150–1170. doi:10.1002/jsfa.5630. PMID 22419102.

- ^ Yang, Yifan (2010). "Theories and concepts in the composition of Chinese herbal formulas". Chinese Herbal Formulas. Elsevier Ltd.: 1–34. doi:10.1016/B978-0-7020-3132-8.00006-2. ISBN 9780702031328. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- ^ Dharmananda, Subhuti (May 1997). "The Methods of Preparation of Herb Formulas: Decoctions, Dried Decoctions, Powders, Pills, Tablets, and Tinctures". Institute of Traditional Medicine, Portland, Oregon. Archived from the original on 2017-10-04. Retrieved 2017-09-27.

- ^ Mount, Toni (20 April 2015). "9 weird medieval medicines". British Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 28 September 2017. Retrieved 27 September 2017.

- ^ Pezzuto, John M. (January 1997). "Plant-derived anticancer agents". Biochemical Pharmacology. 53 (2): 121–133. doi:10.1016/S0006-2952(96)00654-5. PMID 9037244.

- ^ "Traditional Medicine. Fact Sheet No. 134". World Health Organization. May 2003. Archived from the original on 27 July 2008. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- ^ a b Chan, Margaret (19 August 2015). "WHO Director-General addresses traditional medicine forum". WHO. Archived from the original on August 22, 2015.

- ^ "Traditional Chinese Medicine: In Depth (D428)". NIH. April 2009. Archived from the original on 4 April 2017. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- ^ Giovannini, Peter. "Managing diabetes with medicinal plants". Kew Gardens. Archived from the original on 3 October 2017. Retrieved 3 October 2017.

- ^ Giovannini, Peter; Howes, Melanie-Jayne R.; Edwards, Sarah E. (2016). "Medicinal plants used in the traditional management of diabetes and its sequelae in Central America: A review". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 184: 58–71. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2016.02.034. PMID 26924564. S2CID 22639191. Archived from the original on 2022-06-07. Retrieved 2020-08-27.

- ^ Milliken, William (2015). "Medicinal knowledge in the Amazon". Kew Gardens. Archived from the original on 2017-10-03. Retrieved 2017-10-03.

- ^ Yanomami, M. I.; Yanomami, E.; Albert, B.; Milliken, W; Coelho, V. (2014). Hwërɨ mamotima thëpë ã oni. Manual dos remedios tradicionais Yanomami [Manual of Traditional Yanomami Medicines]. São Paulo: Hutukara/Instituto Socioambiental.

- ^ "Scoring drugs. A new study suggests alcohol is more harmful than heroin or crack". The Economist. 2 November 2010. Archived from the original on 28 January 2018. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

"Drug harms in the UK: a multi-criteria decision analysis", by David Nutt, Leslie King and Lawrence Phillips, on behalf of the Independent Scientific Committee on Drugs. The Lancet.

- ^ "Herbal medicine". Cancer Research UK. Archived from the original on 29 May 2019. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

There is no reliable evidence from human studies that herbal remedies can treat, prevent or cure any type of cancer. Some clinical trials seem to show that certain Chinese herbs may help people to live longer, might reduce side effects, and help to prevent cancer from coming back. This is especially when combined with conventional treatment.

- ^ a b Saslis-Lagoudakis, C. H.; Savolainen, V.; Williamson, E. M.; Forest, F.; Wagstaff, S. J.; Baral, S. R.; Watson, M. F.; Pendry, C. A.; Hawkins, J. A. (2012). "Phylogenies reveal predictive power of traditional medicine in bioprospecting". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 109 (39): 15835–40. Bibcode:2012PNAS..10915835S. doi:10.1073/pnas.1202242109. PMC 3465383. PMID 22984175.

- ^ "International Regulatory Cooperation for Herbal Medicines (IRCH)". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on September 1, 2013. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ^ Kala, Chandra Prakash; Sajwan, Bikram Singh (2007). "Revitalizing Indian systems of herbal medicine by the National Medicinal Plants Board through institutional networking and capacity building". Current Science. 93 (6): 797–806. JSTOR 24099124.

- ^ a b c World Health Organization (2013). WHO Traditional Medicine Strategy 2014-2023 (PDF). World Health Organization. ISBN 978-92-4-150609-0. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-11-18. Retrieved 2017-10-03.

- ^ "Emergence of Pharmaceutical Science and Industry: 1870-1930". Chemical & Engineering News. Vol. 83, no. 25. 20 June 2005. Archived from the original on 10 November 2018. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ^ Heinrich, M.; Bremner, P. (March 2006). "Ethnobotany and ethnopharmacy--their role for anti-cancer drug development". Current Drug Targets. 7 (3): 239–245. doi:10.2174/138945006776054988. PMID 16515525.

- ^ Moudi, Maryam; Go, Rusea; Yien, Christina Yong Seok; Nazre, Mohd. (November 2013). "Vinca Alkaloids". International Journal of Preventive Medicine. 4 (11): 1231–1235. PMC 3883245. PMID 24404355.

- ^ Fabricant, D. S.; Farnsworth, N. R. (March 2001). "The value of plants used in traditional medicine for drug discovery". Environ. Health Perspect. 109 (Suppl 1): 69–75. doi:10.1289/ehp.01109s169. PMC 1240543. PMID 11250806.

- ^ Baell, Jonathan; Walters, Michael A. (24 September 2014). "Chemistry: Chemical con artists foil drug discovery". Nature. 513 (7519): 481–483. Bibcode:2014Natur.513..481B. doi:10.1038/513481a. PMID 25254460.

- ^ Dahlin, Jayme L; Walters, Michael A (July 2014). "The essential roles of chemistry in high-throughput screening triage". Future Medicinal Chemistry. 6 (11): 1265–90. doi:10.4155/fmc.14.60. PMC 4465542. PMID 25163000.

- ^ Newman, David J.; Cragg, Gordon M. (8 February 2012). "Natural Products As Sources of New Drugs over the 30 Years from 1981 to 2010". Journal of Natural Products. 75 (3): 311–35. doi:10.1021/np200906s. PMC 3721181. PMID 22316239.

- ^ a b "State of the World's Plants and Fungi 2020" (PDF). Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 October 2020. Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- ^ Freye, Enno (2010). "Toxicity of Datura Stramonium". Pharmacology and Abuse of Cocaine, Amphetamines, Ecstasy and Related Designer Drugs. Springer. pp. 217–218. doi:10.1007/978-90-481-2448-0_34. ISBN 978-90-481-2447-3.

- ^ Ernst, E. (1998). "Harmless Herbs? A Review of the Recent Literature" (PDF). The American Journal of Medicine. 104 (2): 170–178. doi:10.1016/S0002-9343(97)00397-5. PMID 9528737. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-11-05. Retrieved 2013-11-28.

- ^ Talalay, P. (2001). "The importance of using scientific principles in the development of medicinal agents from plants". Academic Medicine. 76 (3): 238–47. doi:10.1097/00001888-200103000-00010. PMID 11242573.

- ^ Elvin-Lewis, M. (2001). "Should we be concerned about herbal remedies". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 75 (2–3): 141–164. doi:10.1016/S0378-8741(00)00394-9. PMID 11297844.

- ^ Vickers, A. J. (2007). "Which botanicals or other unconventional anticancer agents should we take to clinical trial?". J Soc Integr Oncol. 5 (3): 125–9. PMC 2590766. PMID 17761132.

- ^ Ernst, E. (2007). "Herbal medicines: balancing benefits and risks". Dietary Supplements and Health. Novartis Foundation Symposia. Vol. 282. Novartis Foundation Symposium. pp. 154–67, discussion 167–72, 212–8. doi:10.1002/9780470319444.ch11. ISBN 978-0-470-31944-4. PMID 17913230.

- ^ Pinn, G. (November 2001). "Adverse effects associated with herbal medicine". Aust Fam Physician. 30 (11): 1070–5. PMID 11759460.

- ^ Nekvindová, J.; Anzenbacher, P. (July 2007). "Interactions of food and dietary supplements with drug metabolising cytochrome P450 enzymes". Ceska Slov Farm. 56 (4): 165–73. PMID 17969314.

- ^ Born, D.; Barron, ML (May 2005). "Herb use in pregnancy: what nurses should know". MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 30 (3): 201–6. doi:10.1097/00005721-200505000-00009. PMID 15867682. S2CID 35882289.

- ^ Barrett, Stephen (23 November 2013). "The herbal minefield". Quackwatch. Archived from the original on 18 August 2018. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- ^ Zhang, J.; Wider, B.; Shang, H.; Li, X.; Ernst, E. (2012). "Quality of herbal medicines: Challenges and solutions". Complementary Therapies in Medicine. 20 (1–2): 100–106. doi:10.1016/j.ctim.2011.09.004. PMID 22305255.

- ^ Morris, C. A.; Avorn, J. (2003). "Internet marketing of herbal products". JAMA. 290 (11): 1505–9. doi:10.1001/jama.290.11.1505. PMID 13129992.

- ^ Coghlan, M. L.; Haile, J.; Houston, J.; Murray, D. C.; White, N. E.; Moolhuijzen, P; Bellgard, M. I.; Bunce, M (2012). "Deep Sequencing of Plant and Animal DNA Contained within Traditional Chinese Medicines Reveals Legality Issues and Health Safety Concerns". PLOS Genetics. 8 (4): e1002657. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002657. PMC 3325194. PMID 22511890.

- ^ Newmaster, S. G.; Grguric, M.; Shanmughanandhan, D.; Ramalingam, S.; Ragupathy, S. (2013). "DNA barcoding detects contamination and substitution in North American herbal products". BMC Medicine. 11: 222. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-11-222. PMC 3851815. PMID 24120035.

- ^ O'Connor, Anahad (5 November 2013). "Herbal Supplements Are Often Not What They Seem". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 3 February 2017. Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- ^ Lordan, Ronan (2021). "Dietary supplements and nutraceuticals market growth during the coronavirus pandemic - implications for consumers and regulatory oversight". Pharmanutrition. Elsevier Public Health Emergency Collection. 18: 100282. doi:10.1016/j.phanu.2021.100282. PMC 8416287. PMID 34513589.

- ^ "United States Files Enforcement Action to Stop Deceptive Marketing of Herbal Tea Product Advertised as Covid-19 Treatment". United States Department of Justice. Department of Justice. 3 March 2022. Archived from the original on 3 October 2022. Retrieved 3 October 2022.

- ^ a b Kling, Jim (2016). "Protecting medicine's wild pharmacy". Nature Plants. 2 (5): 16064. doi:10.1038/nplants.2016.64. PMID 27243657. S2CID 7246069.

- ^ Briggs, Helen (30 September 2020). "Two-fifths of plants at risk of extinction, says report". BBC. Archived from the original on 29 September 2020. Retrieved 30 September 2020.

![The opium poppy Papaver somniferum is the source of the alkaloids morphine and codeine.[52]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/87/Opium_poppy.jpg/160px-Opium_poppy.jpg)

![The alkaloid nicotine from tobacco binds directly to the body's Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, accounting for its pharmacological effects.[58]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/70/Nicotine.svg/143px-Nicotine.svg.png)

![Deadly nightshade, Atropa belladonna, yields tropane alkaloids including atropine, scopolamine and hyoscyamine.[54]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b7/Atropa_belladonna_-_K%C3%B6hler%E2%80%93s_Medizinal-Pflanzen-018.jpg/104px-Atropa_belladonna_-_K%C3%B6hler%E2%80%93s_Medizinal-Pflanzen-018.jpg)

![Senna alexandrina, containing anthraquinone glycosides, has been used as a laxative for millennia.[61]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/61/Senna_alexandrina_Mill.-Cassia_angustifolia_L._%28Senna_Plant%29.jpg/161px-Senna_alexandrina_Mill.-Cassia_angustifolia_L._%28Senna_Plant%29.jpg)

![The foxglove, Digitalis purpurea, contains digoxin, a cardiac glycoside. The plant was used on heart conditions long before the glycoside was identified.[44][63]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/74/Digitalis_purpurea2.jpg/90px-Digitalis_purpurea2.jpg)

![Digoxin is used to treat atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter and sometimes heart failure.[44]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4d/Digoxin.svg/200px-Digoxin.svg.png)

![Polyphenols include phytoestrogens (top and middle), mimics of animal estrogen (bottom).[72]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/11/Phytoestrogens2.png/160px-Phytoestrogens2.png)

![The essential oil of common thyme (Thymus vulgaris), contains the monoterpene thymol, an antiseptic and antifungal.[76]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/fe/Thymian.jpg/181px-Thymian.jpg)

![Thymol is one of many terpenes found in plants.[76]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5d/Thymol2.svg/97px-Thymol2.svg.png)