미치광이

Lunatic미치광이는 정신질환, 위험, [1][2]어리석음 또는 정신이상자로 보이는 사람을 지칭하는 구식 용어이다.그 단어는 "달의" 또는 "달에 매료된"[3][4][5]을 뜻하는 미치광이에서 유래했다.

역사

"병적"이라는 용어는 원래 달에 의해 야기되는 것으로 [7][8][9]생각되는 질병으로 간질과 광기를 주로 언급했던 라틴어 미치광이에서 유래했다. 뇌전증킹 제임스 성경은 마태복음에 "lunatick"을 기록하고 있는데,[7] 이것은 간질에 대한 언급으로 해석되고 있다.4세기와 5세기까지[clarification needed] 점성가들은 일반적으로 신경학적,[7][10] 정신질환을 가리키는 용어를 사용했다.아리스토텔레스와 대 플리니와 같은 철학자들은 보름달이 그렇지 않았다면 어두웠을 밤에 빛을 제공하고 수면 부족의 [11]잘 알려진 경로를 통해 민감한 사람들에게 영향을 줌으로써 양극성 장애를 가진 미친 사람들을 유도했다고 주장했다.적어도 1700년까지, 달이 열, 류머티즘, 뇌전증 그리고 다른 [12]질병들에 영향을 미친다는 것이 일반적인 믿음이었다.

법률에서 "광기적"이라는 용어의 사용

잉글랜드와 웨일스의 관할권에서는 1890~1922년 제정된 제정법은 "광기병자"를 지칭했지만 1930년 제정된 정신치료법은 법적 용어를 "불건전한 정신의 사람"으로 변경했다.이 표현은 1959년 제정된 정신건강법에 따라 "정신질환"으로 대체되었다."건전한 정신의 사람"은 1950년 유럽인권협약 영어판에서 사법 절차에 의해 자유를 박탈당할 수 있는 유형의 사람 중 한 명으로 사용된 용어이다.1930년 법은 또한 "애스문"이라는 용어를 "정신 병원"으로 대체했다.범죄 미치광이는 1946년 국민건강서비스법에 따라 1948년 브로드무어 환자가 됐다.

2012년 12월 5일, 미국 하원은 앞서 미국 [3]상원에서 승인한 법안을 통과시켜 미국의 모든 연방법에서 "광란적"이라는 단어를 삭제했습니다.버락 오바마 대통령은 2012년 [14]12월[13] 28일 2012년 21세기 언어법에 서명했다.

"Of unsound minds" 또는 "non composite mentis"는 19세기 [15]후반 법에서 광기에 대해 사용된 가장 두드러진 용어인 "lunatic"의 대안이다.

달 거리

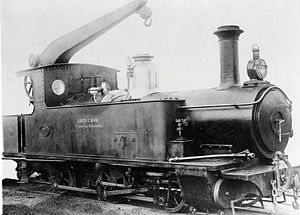

미치광이라는 용어는 때때로 경도를 측정하는 믿을 만한 방법을 발견하려고 하는 사람들을 묘사하기 위해 사용되었습니다.화가 윌리엄 호가스는 1733년작 '레이크의 진보'[16]의 8개 장면에서 경직된 미치광이를 묘사했다.하지만 20년 후, 호가스는 존 해리슨의 H-1 크로노미터를 "지금까지 만들어진 [16]것 중 가장 정교한 움직임 중 하나"라고 묘사했다.

나중에, 버밍엄의 달 협회 회원들은 자신들을 [17]루나틱이라고 불렀다.가로등이 거의 없는 시대에, 사회는 보름달 [18]밤이나 가까운 밤에 모였습니다.

「 」를 참조해 주세요.

레퍼런스

- ^ Great Britain Census Office (1902). "Census of England and Wales, 1901. (63 Vict. C.4.): Middlesex. 1902". Census of England and Wales, 1901. H.M. Stationery Office. 33: xi.

- ^ Vermont Commission to Revise the Statutory Laws (1933). "The Public Laws of Vermont, 1933: (proposed Revision)". The Public Laws of Vermont. Capital City Press, 1933: 424.

- ^ a b Sherman, Amy (17 December 2012). "Allen West said the House voted to remove the word 'lunatic' from federal law". PolitiFact. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- ^ Rotton, James; Kelly, I. W. (1985). "Much ado about the full moon: A meta-analysis of lunar-lunacy research". Psychological Bulletin. 97 (2): 286–306. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.97.2.286. PMID 3885282.

- ^ Forbes, Lebo Jr., Gordon B., George R (1977). "Antisocial Behavior and Lunar Activity: A Failure to Validate the Lunacy Myth". Psychological Reports. 40 (3 Pt. 2): 1309–1310. doi:10.2466/pr0.1977.40.3c.1309. PMID 897044. S2CID 34308541.

- ^ Heydon, C. (1792). Astrology. The wisdom of Solomon in miniature, being a new doctrine of nativities, reduced to accuracy and certainty ... Also, a curious collection of nativities, never before published. London: printed for A. Hamilton. ISBN 9781170010471.

- ^ a b c Riva, M. A.; Tremolizzo, L.; Spicci, M; Ferrarese, C; De Vito, G; Cesana, G. C.; Sironi, V. A. (January 2011). "The Disease of the Moon: The Linguistic and Pathological Evolution of the English Term "Lunatic"". Journal of the History of the Neurosciences. 20 (1): 65–73. doi:10.1080/0964704X.2010.481101. PMID 21253941. S2CID 5886130.

- ^ Frey, J.; Rotton, J.; Barry, T. (1979). "The effects of the full moon on human behavior: Yet another failure to replicate". The Journal of Psychology: Interdisciplinary and Applied. 103 (2): 159–162.

- ^ D.E., Campbell (1982). "Lunar–lunacy research: When enough is enough". Environment and Behavior. 14 (4): 418–424. doi:10.1177/0013916582144002. S2CID 144508020.

- ^ Bunevicius, Adomas; Gendvilaite, Agne; Deltuva, Vytenis Pranas; Tamasauskas, Arimantas (2017). "The association between lunar phase and intracranial aneurysm rupture: Myth or reality? Own data and systematic review". BMC Neurology. 17 (99): 99. doi:10.1186/s12883-017-0879-1. PMC 5437543. PMID 28525979.

- ^ Raison, Charles L.; Klein, Haven M.; Steckler, Morgan (1999). "The moon and madness reconsidered". Journal of Affective Disorders. 53 (1): 99–106. doi:10.1016/S0165-0327(99)00016-6. PMID 10363673.

- ^ Harrison, Mark (2000). "From medical astrology to medical astronomy: sol-lunar and planetary theories of disease in British medicine, c. 1700–1850". The British Journal for the History of Science. 33 (1): 25–48. doi:10.1017/S0007087499003854. PMID 11624340. S2CID 22247498.

- ^ "An act to strike the word "lunatic" from Federal law, and for other purposes". United States Statutes at Large, 112th Congress, 2nd Session. 126: 1619–1620. December 28, 2012. Public Law 112–231. Retrieved March 11, 2020.

- ^ "Statement by the Press Secretary on H.J. Res. 122, H.R. 3477, H.R. 3783, H.R. 3870, H.R. 3912, H.R. 5738, H.R. 5837, H.R. 5954, H.R. 6116, H.R. 6223, S. 285, S. 1379, S. 2170, S. 2367, S. 3193, S. 3311, S. 3315, S. 3564, and S. 3642". whitehouse.gov. December 28, 2012. Retrieved 27 October 2013 – via National Archives.

- ^ "Lunacy". The American Cyclopædia. 1879.

- ^ a b Sobel, Dava (2010). Longitude (10th anniversary ed.). Bloomsbury Publishing USA. p. 87. ISBN 978-0802799678.

- ^ Ian Wylie. "Coleridge and the Lunaticks". In Gravil, Richard; Lefebure, Molly (eds.). The Coleridge Connection: Essays for Thomas McFarland. 1990: Springer. pp. 25–26.

{{cite book}}: CS1 유지보수: 위치(링크) - ^ "Transactions and Proceedings". 22–25. Birmingham, England: Birmingham Archaeological Society. 1897: 26. Retrieved 3 February 2017.

{{cite journal}}:Cite 저널 요구 사항journal=(도움말)

외부 링크

- 보름달은 기분에 어떤 영향을 미칩니까?(연구 결과: 부정 2개, 긍정 1개)

- 월유 범죄 단속– BBC 뉴스, 2007년 6월 5일