로스앤젤레스

Los Angeles로스앤젤레스 | |

|---|---|

| 별명: | |

캘리포니아와 로스앤젤레스 군 내 위치 | |

| 좌표: 34°03'N 118°15'W / 34.050°N 118.250°W/ | |

| 나라 | 미국 |

| 주 | 캘리포니아 |

| 자치주 | 로스앤젤레스 |

| 지역 | 서던캘리포니아 주 |

| CSA | 로스앤젤레스 롱비치 |

| MSA | 로스앤젤레스 롱비치애너하임 |

| 푸에블로 | 1781년[2] 9월 4일 |

| 도시현황 | 1835년[3] 5월 23일 |

| 편입 | 1850년[4] 4월 4일 |

| 이름: | 천사의 여왕, 성모 마리아 |

| 정부 | |

| • 활자 | 강력한 시장-의회[5] |

| • 몸 | 로스앤젤레스 시의회 |

| • 시장 | 카렌 베이스 (D) |

| • 시티 변호사 | 하이드 펠드스타인 소토 (D) |

| • 시티컨트롤러 | 케네스 메지아 (D) |

| 지역 | |

| • 토탈 | 501.55 sq mi (1, 299.01 km) |

| • 육지 | 469.49 sq mi (1,215.97 km2) |

| • 물 | 32.06 sq mi (83.04 km2) |

| 승진 | 305 ft (93 m) |

| 최고 고도 (루켄스 산) | 5,075 ft (1,576 m) |

| 최저고도 (태평양) | 0피트(0m) |

| 인구. | |

| • 토탈 | 3,898,747 |

| • 견적 (2022)[7] | 3,819,538 |

| • 랭크 | 북미 3위 미국 2위 캘리포니아 1위 |

| • 밀도 | 8,304.22/sq mi (3,206.29/km2) |

| • 어반 | 12,237,376 (US: 2nd) |

| • 도시밀도 | 7,476.3/sq mi (2,886.6/km2) |

| • 메트로 | 13,200,998 (US: 2nd) |

| 동음이의어 | 앙헬레뇨, 앙헬레뇨[10][11] |

| GDP | |

| • MSA | 1조2270억 달러(2022) |

| • CSA | 1조 5,280억 달러(2022) |

| 시간대 | UTC–08:00 (PST) |

| • 여름(DST) | UTC–07:00 (PDT) |

| ZIP 코드 | 목록.

|

| 지역코드 | 213, 323, 310, 424, 818, 747, 626 |

| FIPS 코드 | 06-44000 |

| GNIS 피쳐 ID | 1662328, 2410877 |

| 웹사이트 | lacity.gov |

Los Angeles (US: /lɔːs ˈændʒələs/ ⓘ lawss AN-jə-ləss; Spanish: Los Ángeles [los ˈaŋxeles], lit. 'The Angels'), often referred to by its initials L.A.,[16] is the most populous city in the U.S. state of California. 2020년[update] 기준으로 약 390만 명의 주민이 거주하고 있는 로스앤젤레스는 뉴욕 [7]다음으로 미국에서 두 번째로 인구가 많은 도시입니다. 로스앤젤레스는 남부 캘리포니아 지역의 상업, 금융 및 문화의 중심지입니다. 로스앤젤레스는 지중해성 기후와 인종적, 문화적으로 다양한 인구를 가지고 있으며, 광범위한 대도시 지역의 주요 도시입니다.

도시의 대부분은 캘리포니아 남부의 분지에 위치하며 서쪽으로는 태평양에 인접해 있으며, 북쪽으로는 샌타모니카 산맥을 지나 샌퍼넌도 계곡으로 뻗어있으며, 동쪽으로는 샌가브리엘 계곡과 접해있습니다. 면적은 약 469 평방 마일([6]1,210km2)이며, 2022년[update] 기준으로 약 986만 명의 주민이 거주하는 미국에서 가장 인구가 많은 로스앤젤레스 카운티의 군청 소재지입니다.[17] 2019년 기준 460만 명이 넘는 방문객이 방문하는 미국에서 세 번째로 많은 도시입니다.[18]

로스앤젤레스가 된 이 지역은 원래 통바 원주민들이 거주하던 곳이었고, 후에 후안 로드리게스 카브리요가 1542년에 스페인을 위해 영유권을 주장했습니다. 이 도시는 1781년 9월 4일 스페인 총독 펠리페 데 네브의 통치하에 야앙가 마을에 세워졌습니다.[19] 멕시코는 1821년 멕시코 독립 전쟁 이후 멕시코의 일부가 되었습니다. 1848년, 멕시코-미국 전쟁이 끝날 무렵, 로스앤젤레스와 캘리포니아의 나머지 지역은 과달루페 이달고 조약의 일부로 매입되어 미국의 일부가 되었습니다. 로스앤젤레스는 캘리포니아가 주 지위를 얻기 5개월 전인 1850년 4월 4일 지방 자치체로 편입되었습니다. 1890년대에 석유의 발견은 그 도시에 급속한 성장을 가져왔습니다.[20] 이 도시는 1913년 동부 캘리포니아에서 물을 공급하는 로스앤젤레스 수로가 완공되면서 더욱 확장되었습니다.

로스앤젤레스는 다양한 산업과 함께 다양한 경제를 가지고 있으며, 할리우드 영화 산업의 본거지로 가장 잘 알려져 있으며, 세계 최대의 수입을 자랑하는 도시이며, 이 도시는 영화 역사에서 중요한 장소였습니다. 또한 아메리카에서 가장 붐비는 컨테이너 항구 중 하나를 가지고 있습니다.[21][22][23] 2018년 로스앤젤레스 메트로폴리탄 지역은 1조 달러 이상의 대도시 총생산을 [24]기록하여 뉴욕과 도쿄에 이어 세계에서 세 번째로 큰 GDP를 가진 도시가 되었습니다. 로스앤젤레스는 1932년과 1984년에 하계 올림픽을 개최했고, 2028년에도 개최할 예정입니다. 보다 최근, 캘리포니아 주 전역에 걸친 가뭄이 캘리포니아와 로스앤젤레스 카운티의 물 안보를 위협하고 있습니다.[25][26]

토포니미

1781년 9월 4일, "로스 포블라도레스"로 알려진 44명의 정착민들이 엘 푸에블로 데 누에스트라 세뇨라 데 로스 앙겔레스라고 불리는 푸에블로 마을을 설립했습니다.[27] 이 정착지의 원래 이름은 논란의 여지가 있으며, 기네스북은 "El Pueblo de Nuestra Senora de los Angeles de Porciúcula"로 수정했습니다. 다른 자료들은 더 긴 이름의 단축 또는 대체 버전을 제공합니다.

도시 이름의 현지 영어 발음은 시간이 지남에 따라 다양했습니다. 1953년 미국이름학회지에 실린 기사는 발음 /l ɔː ˈæ ʒə /l ə ə /laws AN-j ə ə가 1850년 도시 편입 이후 설립되었으며 1880년대 이후 발음 /lo ʊ ˈæŋɡə /lohss ANG-g ə ə가 캘리포니아에서 스페인어 또는 스페인어로 들리는 장소를 제공하는 추세에서 비롯되었다고 주장합니다. 이름과 발음.[30] 1908년, 사서 찰스 플레처 루미스(Charles Fletcher Lummis)는 하드 g(/ ɡ/)로 이름의 발음을 주장하며 최소 12개의 발음 변형이 있다고 보고했습니다. 1900년대 초, 로스앤젤레스 타임즈는 몇 년 동안 마스트헤드 아래에 철자를 인쇄함으로써 스페인어 [로스 ˈ라 ŋ셀레스]와 유사한 Loce AHNG-hayl-ais (/lo ʊ ˈɑːŋ ɪ/)를 발음할 것을 옹호했습니다. 이것은 호의를 얻지 못했습니다.[35]

1930년대부터 /l ɔː ˈæn ʒən əs/가 가장 일반적이었습니다. 1934년 미국 지명위원회는 이 발음을 사용하도록 결정했습니다.[34] 이것은 또한 1952년 플레처 보론 시장이 공식적인 발음을 고안하기 위해 임명한 "배심"에 의해 승인되었습니다.[30][34]

영국의 일반적인 발음으로는 /l ɒ ˈænd ʒɪli ːz, -l ɪz, -l ɪs/ loss AN-jil-eez, -iz, -iss가 있습니다. 음성학자 잭 윈저 루이스(Jack Windsor Lewis)는 가장 흔한 철자인 /l ɒs ˈænd ʒɪli ːz/를 "스페인어가 아니라면 고전이 익숙했던 시절을 반영한다"고 -es로 끝나는 그리스 단어에 비유하여 철자 발음으로 설명했습니다.

역사

원주민 역사

오늘날의 로스앤젤레스 분지와 샌페르난도 계곡에 캘리포니아 원주민들이 정착한 곳은 통바(현재 스페인 식민지 시대부터 가브리엘레뇨라고도 함)에 의해 지배되었습니다. 이 지역에서 통바 세력의 역사적 중심지는 야앙가(통바: 이야앙 ẚ)는 "독이 든 참나무의 장소"라는 뜻으로, 언젠가 스페인 사람들이 푸에블로 데 로스 앙겔레스를 설립한 장소가 될 것입니다. 이앙 ẚ는 또한 "연기의 계곡"이라고 번역되었습니다.

스페인의 통치

해양 탐험가 후안 로드리게스 카브릴로는 1542년에 스페인 제국을 위해 캘리포니아 남부 지역을 차지했습니다. 그는 앞서 식민지였던 중앙 아메리카와 남아메리카의 뉴 스페인 기지에서 태평양 연안을 따라 북상하는 공식적인 군사 탐험을 하고 있었습니다.[43] 가스파르 데 포르톨라와 프란치스코회 선교사 후안 크레스피는 1769년 8월 2일 현재의 로스앤젤레스에 도착했습니다.[44]

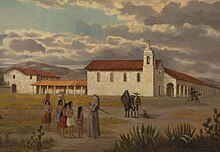

1771년 프란치스코회 수도사 주니페로 세라는 이 지역의 첫 번째 미션인 산 가브리엘 아르칸겔의 건축을 지휘했습니다.[45] 1781년 9월 4일, "로스 포블라도레스"로 알려진 44명의 정착민들이 엘 푸에블로 데 누에스트라 세뇨라 데 로스 앙겔레스라고 불리는 푸에블로 마을을 설립했습니다.[27] 오늘날의 이 도시에는 미국에서 가장 큰 로마 가톨릭 대교구가 있습니다. 멕시코 또는 (뉴 스페인) 정착민의 3분의 2는 아프리카, 토착 및 유럽 혈통이 혼합된 메스티조 또는 물라토였습니다.[46] 그 정착지는 수십 년 동안 작은 목장 마을로 남아 있었지만, 1820년까지 인구는 약 650명으로 증가했습니다.[47] 오늘날, 푸에블로는 로스엔젤레스의 가장 오래된 지역인 로스엔젤레스 푸에블로 광장과 올베라 거리의 역사적인 지역에서 기념되고 있습니다.[48]

멕시코 통치

뉴 스페인은 1821년에 스페인 제국으로부터 독립을 이루었고, 푸에블로는 이제 새로운 멕시코 공화국 안에 존재했습니다. 멕시코 통치 기간 동안 피오 피코 주지사는 로스앤젤레스를 알타 캘리포니아의 지역 수도로 만들었습니다.[49] 이 시기에 새로운 공화국은 로스앤젤레스 지역 내에 더 많은 세속화 행위를 도입했습니다.[50] 1846년, 멕시코-미국 전쟁 중에, 미국의 해병대가 푸에블로를 점령했습니다. 이로 인해 150명의 멕시코 민병대가 점령군과 싸웠고 결국 항복했습니다.[51]

멕시코의 통치는 더 큰 멕시코-미국 전쟁의 일부인 미국의 캘리포니아 정복 이후에 끝났습니다. 1847년 1월 13일 카웬가 조약이 체결되면서 미국인들은 일련의 전투 끝에 캘리포니아로부터 지배권을 잡았습니다.[52] 멕시코 의회는 1848년 로스앤젤레스와 알타 캘리포니아의 나머지 지역을 미국에 양도하는 과달루페 이달고 조약으로 공식화되었습니다.

정복후시대

철도는 1876년 뉴올리언스에서 로스앤젤레스로 가는 남태평양 횡단선과 1885년 산타페 철도가 완공되면서 도착했습니다.[53] 1892년에 도시와 그 주변 지역에서 석유가 발견되었고, 1923년까지 그 발견들은 캘리포니아가 세계 석유 생산량의 약 4분의 1을 차지하는 미국 최대의 산유국이 되는 것을 도왔습니다.[54]

1900년까지 인구는 102,000명 이상으로 [55]증가하여 도시의 물 공급에 압력을 가했습니다.[56] 1913년 윌리엄 멀홀랜드(William Mulholland)의 감독 하에 로스앤젤레스 수로가 완공되면서 도시의 지속적인 성장이 보장되었습니다.[57] 로스앤젤레스 시가 수로에서 나오는 물을 국경 밖의 어떤 지역에도 팔거나 제공할 수 없도록 한 도시 헌장의 조항 때문에 인접한 많은 도시와 지역사회는 로스앤젤레스에 합류해야 한다고 느꼈습니다.[58][59][60]

Los Angeles는 미국 최초의 시 구역 조례를 만들었습니다. 1908년 9월 14일, 로스앤젤레스 시의회는 주거 및 산업용 토지 사용 구역을 공포했습니다. 새 조례는 산업용 사용이 금지된 단일 유형의 주거지역 3곳을 신설했습니다. 처방에는 헛간, 목재 마당 및 기계 동력 장비를 사용하는 모든 산업용 토지 사용이 포함되었습니다. 이 법들은 그 후 산업 재산에 대해 시행되었습니다. 이러한 금지는 이미 뉘앙스로 규정된 기존 활동에 추가되었습니다. 여기에는 폭발물 창고, 가스 작업, 석유 시추, 도축장 및 태닝이 포함됩니다. 로스앤젤레스 시의회는 또한 도시 내에 7개의 산업 구역을 지정했습니다. 그러나 1908년과 1915년 사이에 로스앤젤레스 시의회는 이 세 주거 지역에 적용되는 광범위한 규정에 대한 다양한 예외를 만들었고 그 결과 일부 산업적 용도가 그 안에서 나타났습니다. 1908년 레지던스 지구 조례와 이후 미국의 구역법 사이에는 두 가지 차이점이 있습니다. 첫째, 1908년 법률은 1916년 뉴욕시 구역 조례처럼 포괄적 구역 지도를 설정하지 않았습니다. 둘째,[61] 주거지역은 주거형태를 구분하지 않고 아파트, 호텔, 단독주택을 동일하게 취급하였습니다.

1910년 할리우드는 로스앤젤레스로 합병되었고, 당시 이미 10개의 영화사가 로스앤젤레스에서 운영되고 있었습니다. 1921년까지 세계 영화 산업의 80% 이상이 LA에 집중되었습니다.[62] 그 산업이 창출한 돈은 그 도시를 대공황 동안 나머지 국가가 입은 경제적 손실의 많은 부분으로부터 격리시켰습니다.[63] 1930년까지 인구는 백만 명을 넘어섰습니다.[64] 1932년에 이 도시는 하계 올림픽을 개최했습니다.

제2차 세계 대전 이후

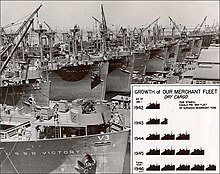

제2차 세계 대전 동안 로스앤젤레스는 조선과 항공기와 같은 전시 제조업의 주요 중심지였습니다. 캘쉽은 터미널 아일랜드에 수백 척의 리버티 선박과 빅토리 선박을 건조했으며 로스앤젤레스 지역은 미국의 주요 항공기 제조업체 6곳(더글라스 에어크래프트 컴퍼니, 휴즈 에어크래프트, 록히드, 북미 항공, 노스럽 코퍼레이션, 벌티)의 본사였습니다. 전쟁 기간 동안, 1903년 라이트 형제가 첫 비행기를 조종한 이래 전쟁 이전의 모든 해들보다 1년 동안 더 많은 항공기가 생산되었습니다. 로스앤젤레스의 제조업이 급증했고, 국방자문위원회의 윌리엄 S. 크누센(William S. Knudsen)은 "우리가 승리한 것은 적을 본 적도 없고, 가능성도 꿈꾸지도 못한, 눈사태 같은 생산으로 그를 제압했기 때문입니다."[65]라고 말했습니다.

제2차 세계 대전이 끝난 후 로스앤젤레스는 그 어느 때보다 빠르게 성장하여 산 페르난도 계곡으로 뻗어나갔습니다.[66] 1950년대와 1960년대에 주정부 소유의 주간 고속도로 시스템의 확장은 교외의 성장을 촉진하는 데 도움을 주었고 세계에서 가장 큰 도시였던 도시의 민간 소유 전철화 철도 시스템의 붕괴를 암시했습니다.

제2차 세계 대전과 교외 지역의 성장, 인구 밀도 등으로 인해 이 지역에는 많은 놀이공원이 조성되어 운영되고 있습니다.[67] 예를 들어, 베벌리 파크는 베벌리 대로와 라 시에네가의 모퉁이에 위치해 있었고, 베벌리 센터에 의해 폐쇄되고 대체되었습니다.[68]

인종적 긴장으로 1965년 와츠 폭동이 일어나 34명이 사망하고 1,000명이 넘는 부상자가 발생했습니다.[69]

1969년 캘리포니아는 로스앤젤레스 캘리포니아 대학교(UCLA)에서 멘로 파크(Menlo Park)에 있는 스탠포드 연구소(Stanford Research Institute)로 첫 ARPANET 전송이 전송되면서 인터넷의 탄생지가 되었습니다.[70]

1973년, 톰 브래들리는 이 도시의 첫 아프리카계 미국인 시장으로 선출되어 1993년에 은퇴할 때까지 다섯 번의 임기를 역임했습니다. 1970년대에 이 도시에서 일어난 다른 사건들로는 1974년에 발생한 심비안 해방군의 남중부 충돌 사건과 1977-1978년에 발생한 힐사이드 스트랭글러스 살인 사건이 있습니다.[71]

1984년 초, 이 도시는 인구에서 시카고를 능가하여 미국에서 두 번째로 큰 도시가 되었습니다.

1984년, 이 도시는 두 번째로 하계 올림픽을 개최했습니다. 공산주의 14개국의 보이콧에도 불구하고, 1984년 올림픽은 그 어느 때보다 재정적으로 성공을 거두었고,[72] 두 번째 올림픽은 이익을 낸 것이었습니다; 현대 신문의 분석에 따르면, 다른 하나는 역시 로스앤젤레스에서 개최된 1932년 하계 올림픽이었습니다.[73]

1992년 4월 29일 로스앤젤레스 경찰국(LAPD) 경찰관 4명으로 구성된 시미 밸리 배심원단이 로드니 킹을 구타하는 비디오테이프에 찍힌 무죄 판결을 내리면서 인종간 긴장이 고조되었고, 결국 대규모 폭동으로 끝이 났습니다.[74][75]

1994년, 규모 6.7의 노스리지 지진이 도시를 뒤흔들었고, 125억 달러의 피해와 72명의 사망자를 냈습니다.[76] 세기는 미국 역사상 가장 광범위하게 기록된 경찰의 위법 행위 사례 중 하나인 램파트 스캔들로 끝났습니다.[77]

21세기

2002년, 제임스 한 시장은 분리독립 반대 운동을 이끌었고, 결과적으로 유권자들은 샌 페르난도 밸리와 할리우드의 도시 이탈 노력을 물리쳤습니다.[78]

2022년 카렌 배스(Karen Bass)는 도시의 첫 번째 여성 시장이 되었고, 로스앤젤레스는 여성을 시장으로 한 가장 큰 미국 도시가 되었습니다.[79]

로스앤젤레스는 2028년 하계 올림픽과 장애인 올림픽을 개최할 예정이며, 이로써 로스앤젤레스는 올림픽을 세 번 개최하는 세 번째 도시가 되었습니다.[80][81]

지리학

지형

로스앤젤레스 시의 총 면적은 502.7 평방 마일(1,302 km2)이며, 468.7 평방 마일(1,214 km2)의 땅과 34.0 평방 마일(88 km2)의 물로 이루어져 있습니다.[82] 이 도시는 북쪽에서 남쪽으로 44마일(71km), 동쪽에서 서쪽으로 29마일(47km)에 걸쳐 뻗어 있습니다. 도시의 둘레는 342마일(550km)입니다.

로스앤젤레스는 평평하고 언덕이 많습니다. 이 도시에서 가장 높은 지점은 산 페르난도 계곡의 북동쪽 끝에 위치한 [83][84]5,074 피트 (1,547 m)의 루켄스 산입니다. 샌타모니카 산맥의 동쪽 끝은 다운타운에서 태평양까지 뻗어있으며 로스앤젤레스 분지와 샌 페르난도 계곡 사이를 갈라놓습니다. 로스앤젤레스의 다른 언덕 지역에는 다운타운 북쪽의 워싱턴 산 지역, 보일 하이츠와 같은 동부 지역, 볼드윈 힐스 주변의 크렌쇼 지역, 그리고 샌페드로 지역이 있습니다.

도시를 둘러싸고 있는 산들은 훨씬 더 높습니다. 바로 북쪽에는 앙헬레노스의 인기 있는 휴양지인 산 가브리엘 산맥이 있습니다. 그것의 높은 지점은 10,064 피트 (3,068 m)에 달하는 발디 산으로 알려진 산 안토니오 산입니다. 캘리포니아 남부에서 가장 높은 곳은 로스앤젤레스 도심에서 동쪽으로 81마일(130km) 떨어진 샌고리오 산(San Gorgonio Mountain)[85]으로 높이는 11,503피트(3,506m)입니다.

로스엔젤레스 강은 대부분 계절에 따라 흐르는 주요 배수로입니다. 육군 공병대는 홍수 조절 통로 역할을 하기 위해 콘크리트 51마일(82km)에 걸쳐 곧게 펴서 줄을 세웠습니다.[86] 강은 도시의 카노가 공원 구역에서 시작하여 샌 페르난도 계곡에서 샌타모니카 산맥의 북쪽 가장자리를 따라 동쪽으로 흘러 도심을 남쪽으로 돌면서 태평양의 롱비치 항구에서 입으로 흘러갑니다. 더 작은 발로나 크릭은 플레이아 델 레이의 산타 모니카 만으로 흘러들어갑니다.

초목

로스앤젤레스는 해변, 습지, 산을 포함한 서식지의 다양성 때문에 토종 식물 종이 풍부합니다. 가장 일반적인 식물 군집은 해안 세이지 스크럽, 차파랄 관목 지대 및 강림 삼림입니다.[87] 토종 식물은 캘리포니아 양귀비, 마틸리자 양귀비, 토욘, 시아노투스, 샤미세, 코스트 라이브 오크, 시카모어, 버드나무, 자이언트 와일드례입니다. 로스앤젤레스 해바라기와 같은 이런 토종 종들은 멸종 위기에 처한 것으로 여겨질 정도로 희귀해졌습니다. 멕시칸 팬 팜스, 카나리아 아일랜드 팜스, 퀸 팜스, 데이트 팜스, 캘리포니아 팬 팜스는 로스앤젤레스 지역에서 흔하지만, 마지막 한 마리만 캘리포니아가 원산지이지만 여전히 로스앤젤레스 시는 원산지가 아닙니다.

로스앤젤레스에는 공식적인 식물상이 많이 있습니다.

- 로스엔젤레스의 공식적인 나무는 산호나무입니다. (Ethrina caffra)[88]

- 공식적인 꽃은 낙원의 새(Strelitzia reginae)[89]입니다.

- 공식 식물은 toyon (Heteromeles arbutifolia)[90]

지질학

로스앤젤레스는 태평양 불의 고리에 위치해 있기 때문에 지진의 영향을 받습니다. 지질학적 불안정으로 인해 수많은 단층이 생성되었으며, 대부분은 너무 작아서 느낄 수 없지만 남부 캘리포니아에서 매년 약 10,000회의 지진이 발생합니다.[91] 태평양 판과 북미 판의 경계에 위치한 스트라이크 슬립 샌 안드레아스 단층 시스템이 로스앤젤레스 대도시 지역을 통과합니다. 남부 캘리포니아를 지나는 단층 부분은 대략 110년에서 140년에 한 번씩 대지진을 경험하며, 마지막 대지진이 1857년 테종 요새 지진이었기 때문에 지진학자들은 다음 "큰 지진"에 대해 경고했습니다.[92] 로스앤젤레스 유역과 대도시 지역도 맹목적인 추력 지진의 위험에 처해 있습니다.[93] 로스앤젤레스 지역을 강타한 주요 지진으로는 1933년 롱비치, 1971년 샌 페르난도, 1987년 휘티어 네로우즈, 1994년 노스리지 사건 등이 있습니다. 몇 개를 제외하고는 모두 강도가 낮아서 느껴지지 않습니다. USGS는 캘리포니아 지진 발생을 모델로 한 UCERF 캘리포니아 지진 예보를 발표했습니다. 1946년 알류샨 열도 지진, 1960년 발디비아 지진, 1964년 알래스카 지진, 2010년 칠레 지진, 2011년 일본 지진으로 항구 지역이 쓰나미에 취약합니다.[94]

도시경관

도시는 많은 다른 구역과 지역으로 나뉘며,[95][96] 그 중 일부는 로스앤젤레스와 합병된 통합 도시였습니다.[97] 이 지역들은 단편적으로 개발되었으며 도시에 거의 모든 것을 표시하는 표지판이 있을 정도로 잘 정의되어 있습니다.[98]

개요

도시의 거리 패턴은 일반적으로 균일한 블록 길이와 때때로 블록을 가로지르는 도로가 있는 그리드 계획을 따릅니다. 그러나 이는 험준한 지형으로 인해 복잡하며, 이로 인해 로스앤젤레스가 덮고 있는 각 계곡마다 다른 격자를 가질 필요가 있었습니다. 주요 거리들은 많은 양의 교통량이 도시의 많은 부분들을 통과하도록 설계되어 있는데, 그 중 많은 부분들이 극도로 길며, Sepulveda Boulevard는 길이가 43마일(69km)인 반면, Foothill Boulevard는 60마일(97km)이 넘어 San Bernardino만큼 동쪽에 도달합니다. 내비게이션 시스템 제조업체인 톰 톰 톰(Tom Tom)의 연간 교통지수에 따르면, 로스앤젤레스의 운전자들은 세계에서 최악의 러시 아워 기간 중 하나로 고통 받고 있습니다. LA 운전자들은 매년 교통 체증에 92시간을 더 소비합니다. 지수에 따르면 출근 시간대에 80%의 혼잡이 발생합니다.[99]

로스앤젤레스는 종종 뉴욕시와 대조적으로 낮은 층의 건물이 있는 것이 특징입니다. 다운타운, 워너 센터, 센추리 시티, 코리아타운, 미라클 마일, 할리우드, 웨스트우드와 같은 몇몇의 중심지 밖에서, 마천루와 고층 건물들은 로스앤젤레스에서 흔하지 않습니다. 그 지역 밖에 지어진 몇 안 되는 마천루들은 종종 주변 경관의 나머지 부분보다 눈에 띕니다. 대부분의 건설은 벽과 벽이 아닌 별도의 단위로 이루어집니다. 그러나 다운타운 로스앤젤레스 자체에는 30층 이상의 많은 건물들이 있고, 50층 이상의 14개의 건물과 70층 이상의 2개의 건물이 있으며, 그 중에서 가장 높은 것은 윌셔 그랜드 센터입니다. 또한 로스앤젤레스는 단독주택보다는 아파트의 도시가 되어가고 있으며, 특히 밀집된 도심과 웨스트사이드 지역에서 더욱 그러합니다.[citation needed]

- 로스앤젤레스의 지역구 선정

기후.

| 로스앤젤레스(다운타운) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 기후도(설명) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

로스앤젤레스는 건조한 여름과 매우 온화한 겨울(Köppen: 해안의 Csb, 그렇지 않은 경우 Csa)을 가진 두 계절의 지중해성 기후이지만, 대부분의 다른 지중해성 기후보다 적은 연간 강수량을 받기 때문에, 비록 아슬아슬하게 놓쳤지만 반건조 기후(BSh)의 경계 근처에 있습니다.[101] 낮 기온은 대체로 일년 내내 온화합니다. 겨울에는 평균 약 68°F(20°C)의 온도를 유지하여 도시에 열대 기후를 느끼게 합니다. 하지만 평균적으로 열대 기후라고 하기에는 몇 도는 너무 시원합니다.[102][103] 가을은 더운 경향이 있으며, 9월과 10월에 주요 폭염이 흔히 발생하는 반면, 봄은 더 시원하고 강수량이 많은 경향이 있습니다. 로스앤젤레스는 일년 내내 햇볕이 잘 내리쬐며, 연평균 강수량은 35일에 불과합니다.[104]

해안 유역의 기온은 한 달에 하루, 4월, 5월, 6월, 11월에 한 달에 하루, 7월, 8월, 10월에 한 달에 3일, 9월에 5일까지 일년 중 12일 정도에 90°F(32°C)를 넘습니다.[104] 산 페르난도와 산 가브리엘 계곡의 기온은 상당히 따뜻합니다. 기온은 일교차가 크며 내륙지역에서는 일평균 최저기온과 일평균 최고기온의 차이가 30°F(17°C)를 넘습니다.[105] 바다의 연평균 기온은 1월 58°F에서 8월 68°F까지 17°C입니다.[106] 일조 시간은 12월 하루 평균 7시간에서 7월 평균 12시간으로 연간 총 3,000시간 이상입니다.[107]

주변 지역의 산악 지형으로 인해 로스앤젤레스 지역은 뚜렷한 미세 기후가 많이 포함되어 있어 서로 물리적으로 가까운 거리에서 극심한 온도 편차를 유발합니다. 예를 들어, 샌타모니카 부두의 7월 평균 최고 기온은 화씨 70 °F (21 °C)인 반면, 카노가 공원은 15 마일 (24 km) 떨어진 95 °F (35 °C)입니다.[108] 이 도시는 남부 캘리포니아 해안의 많은 지역과 마찬가지로 늦봄/초여름 날씨 현상인 "June Gloom"을 겪고 있습니다. 아침에 구름이 많거나 안개가 자욱한 하늘이 있어 이른 오후까지 햇볕을 쬐게 됩니다.[109]

보다 최근에는 캘리포니아 주 전역에 걸친 가뭄으로 인해 캘리포니아의 물 안보가 더욱 악화되었습니다.[26] 로스앤젤레스 도심은 연평균 14.67인치(373mm)의 강수량을 보이며, 주로 11월과 3월 사이에 발생하며,[110][105] 일반적으로 적당한 소나기의 형태로 발생하지만, 때로는 겨울 폭풍 동안 폭우가 내리기도 합니다. 강우량은 일반적으로 지형적 융기로 인해 산의 언덕과 해안 경사면에서 더 높습니다. 여름날은 보통 비가 오지 않습니다. 드물게, 남쪽이나 동쪽에서 습한 공기의 침입은 늦여름에, 특히 산에, 짧은 뇌우를 일으킬 수 있습니다. 해안은 강우량이 약간 적은 반면 내륙과 산지는 상당히 많아집니다. 몇 년 동안의 평균 강우량은 드문 일입니다. 일반적인 패턴은 연간 변동성이며, (130-250 mm) 강우 시 5-10년의 짧은 건조 연도와 20인치(510 mm) 이상의 습윤 연도가 뒤따릅니다.[105] 습한 해는 일반적으로 태평양의 따뜻한 물 엘니뇨 상태와 관련이 있고 건조한 해는 더 시원한 물 라니냐 에피소드와 관련이 있습니다. 비가 오는 날이 연이어 오면 저지대에 홍수가 나고, 특히 산불로 사면이 황폐해진 후에는 언덕에 진흙이 쌓일 수 있습니다.

1979년 1월 29일에 도심역에서 섭씨 32도가 관측된 것을 마지막으로, 영하의 기온과 강설량은 도시 유역과 해안을 따라 매우 드물며,[105] 거의 매년 계곡 지역에서 강설량이 발생하고 도시 경계 내에 있는 산들은 보통 겨울마다 강설량을 받습니다. 1932년 1월 15일 로스앤젤레스 도심에서 기록된 최고 적설량은 2.0인치(5cm)였습니다.[105][111] 가장 최근의 강설은 1962년 이후 첫 강설인 2019년 2월에 발생했으며,[112][113] 최근에는 2021년 1월까지 로스앤젤레스 인접 지역에 눈이 내렸습니다.[114] 간략히 설명하자면 국지적인 우박 사례는 드문 경우에 발생할 수 있지만 강설보다 더 일반적입니다. 공식 시내역에서 기록된 최고 기온은 2010년 9월 27일의 화씨 113°F([105][115]45°C)이고, 최저 기온은 1949년 1월 4일의 [105]화씨 28°F(-2°C)입니다.[105] 로스앤젤레스 시에서 공식적으로 기록된 최고 기온은 2020년 9월 6일 우드랜드 힐스의 샌 페르난도 밸리 근처에 있는 피어스 칼리지의 기상관측소에서 기록된 121°F(49°C)입니다.[116] 가을과 겨울 동안, 산타 아나 바람은 때때로 로스앤젤레스에 훨씬 더 따뜻하고 건조한 상태를 가져오며, 산불 위험을 높입니다.

| 달 | 얀 | 2월 | 마르 | 4월 | 그럴지도 모른다 | 준 | 줄 | 8월 | 9월 | 10월 | 11월 | 12월 | 연도 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 최고 °F(°C) 기록 | 95 (35) | 95 (35) | 99 (37) | 106 (41) | 103 (39) | 112 (44) | 109 (43) | 106 (41) | 113 (45) | 108 (42) | 100 (38) | 92 (33) | 113 (45) |

| 평균 최대 °F(°C) | 83.0 (28.3) | 82.8 (28.2) | 85.8 (29.9) | 90.1 (32.3) | 88.9 (31.6) | 89.1 (31.7) | 93.5 (34.2) | 95.2 (35.1) | 99.4 (37.4) | 95.7 (35.4) | 88.9 (31.6) | 81.0 (27.2) | 101.5 (38.6) |

| 일평균 최대 °F(°C) | 68.0 (20.0) | 68.0 (20.0) | 69.9 (21.1) | 72.4 (22.4) | 73.7 (23.2) | 77.2 (25.1) | 82.0 (27.8) | 84.0 (28.9) | 83.0 (28.3) | 78.6 (25.9) | 72.9 (22.7) | 67.4 (19.7) | 74.8 (23.8) |

| 일평균 °F(°C) | 58.4 (14.7) | 59.0 (15.0) | 61.1 (16.2) | 63.6 (17.6) | 65.9 (18.8) | 69.3 (20.7) | 73.3 (22.9) | 74.7 (23.7) | 73.6 (23.1) | 69.3 (20.7) | 63.0 (17.2) | 57.8 (14.3) | 65.8 (18.8) |

| 일 평균 최소 °F(°C) | 48.9 (9.4) | 50.0 (10.0) | 52.4 (11.3) | 54.8 (12.7) | 58.1 (14.5) | 61.4 (16.3) | 64.7 (18.2) | 65.4 (18.6) | 64.2 (17.9) | 59.9 (15.5) | 53.1 (11.7) | 48.2 (9.0) | 56.8 (13.8) |

| 평균 최소 °F(°C) | 41.4 (5.2) | 42.9 (6.1) | 45.4 (7.4) | 48.9 (9.4) | 53.5 (11.9) | 57.4 (14.1) | 61.1 (16.2) | 61.7 (16.5) | 59.1 (15.1) | 53.7 (12.1) | 45.4 (7.4) | 40.5 (4.7) | 39.2 (4.0) |

| 낮은 °F(°C) 기록 | 28 (−2) | 28 (−2) | 31 (−1) | 36 (2) | 40 (4) | 46 (8) | 49 (9) | 49 (9) | 44 (7) | 40 (4) | 34 (1) | 30 (−1) | 28 (−2) |

| 평균 강우 인치(mm) | 3.29 (84) | 3.64 (92) | 2.23 (57) | 0.69 (18) | 0.32 (8.1) | 0.09 (2.3) | 0.02 (0.51) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.13 (3.3) | 0.58 (15) | 0.78 (20) | 2.48 (63) | 14.25 (362) |

| 평균 우천일수(≥ 0.01 in) | 6.1 | 6.3 | 5.1 | 2.8 | 1.9 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 2.2 | 2.8 | 5.5 | 34.1 |

| 월평균 일조시간 | 225.3 | 222.5 | 267.0 | 303.5 | 276.2 | 275.8 | 364.1 | 349.5 | 278.5 | 255.1 | 217.3 | 219.4 | 3,254.2 |

| 가능한 일조량 백분율 | 71 | 72 | 72 | 78 | 64 | 64 | 83 | 84 | 75 | 73 | 70 | 71 | 73 |

| 평균자외선지수 | 2.9 | 4.2 | 6.2 | 8.1 | 9.2 | 10.4 | 10.8 | 10.0 | 8.1 | 5.4 | 3.5 | 2.6 | 6.7 |

| 출처 1: NOAA(1961-1977년 일요일)[117][100][118][119] | |||||||||||||

| 출처 2: UV Index Today (1995년 ~ 2022년)[120] | |||||||||||||

| 달 | 얀 | 2월 | 마르 | 4월 | 그럴지도 모른다 | 준 | 줄 | 8월 | 9월 | 10월 | 11월 | 12월 | 연도 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 최고 °F(°C) 기록 | 91 (33) | 92 (33) | 95 (35) | 102 (39) | 97 (36) | 104 (40) | 97 (36) | 98 (37) | 110 (43) | 106 (41) | 101 (38) | 94 (34) | 110 (43) |

| 평균 최대 °F(°C) | 81.2 (27.3) | 80.1 (26.7) | 80.6 (27.0) | 83.1 (28.4) | 80.6 (27.0) | 79.8 (26.6) | 83.7 (28.7) | 86.0 (30.0) | 90.7 (32.6) | 90.9 (32.7) | 87.2 (30.7) | 78.8 (26.0) | 95.5 (35.3) |

| 일평균 최대 °F(°C) | 66.3 (19.1) | 65.6 (18.7) | 66.1 (18.9) | 68.1 (20.1) | 69.5 (20.8) | 72.0 (22.2) | 75.1 (23.9) | 76.7 (24.8) | 76.5 (24.7) | 74.4 (23.6) | 70.9 (21.6) | 66.1 (18.9) | 70.6 (21.4) |

| 일평균 °F(°C) | 57.9 (14.4) | 57.9 (14.4) | 59.1 (15.1) | 61.1 (16.2) | 63.6 (17.6) | 66.4 (19.1) | 69.6 (20.9) | 70.7 (21.5) | 70.1 (21.2) | 67.1 (19.5) | 62.3 (16.8) | 57.6 (14.2) | 63.6 (17.6) |

| 일 평균 최소 °F(°C) | 49.4 (9.7) | 50.1 (10.1) | 52.2 (11.2) | 54.2 (12.3) | 57.6 (14.2) | 60.9 (16.1) | 64.0 (17.8) | 64.8 (18.2) | 63.7 (17.6) | 59.8 (15.4) | 53.7 (12.1) | 49.1 (9.5) | 56.6 (13.7) |

| 평균 최소 °F(°C) | 41.8 (5.4) | 42.9 (6.1) | 45.3 (7.4) | 48.0 (8.9) | 52.7 (11.5) | 56.7 (13.7) | 60.2 (15.7) | 61.0 (16.1) | 58.7 (14.8) | 53.2 (11.8) | 46.1 (7.8) | 41.1 (5.1) | 39.4 (4.1) |

| 낮은 °F(°C) 기록 | 27 (−3) | 34 (1) | 35 (2) | 42 (6) | 45 (7) | 48 (9) | 52 (11) | 51 (11) | 47 (8) | 43 (6) | 38 (3) | 32 (0) | 27 (−3) |

| 평균 강우 인치(mm) | 2.86 (73) | 2.99 (76) | 1.73 (44) | 0.60 (15) | 0.28 (7.1) | 0.08 (2.0) | 0.04 (1.0) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.11 (2.8) | 0.49 (12) | 0.82 (21) | 2.23 (57) | 12.23 (311) |

| 평균 우천일수(≥ 0.01 in) | 6.1 | 6.3 | 5.6 | 2.6 | 1.7 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 2.0 | 3.2 | 5.4 | 34.5 |

| 평균 상대습도(%) | 63.4 | 67.9 | 70.5 | 71.0 | 74.0 | 75.9 | 76.6 | 76.6 | 74.2 | 70.5 | 65.5 | 62.9 | 70.8 |

| 평균 이슬점 °F(°C) | 41.4 (5.2) | 44.4 (6.9) | 46.6 (8.1) | 49.1 (9.5) | 52.7 (11.5) | 56.5 (13.6) | 60.1 (15.6) | 61.2 (16.2) | 59.2 (15.1) | 54.1 (12.3) | 46.8 (8.2) | 41.4 (5.2) | 51.1 (10.6) |

| 출처: NOAA(상대습도 및 이슬점 1961-1990)[117][121][122][123] | |||||||||||||

환경문제

| 외장 오디오 | |

|---|---|

로스앤젤레스는 지리적, 자동차에 대한 높은 의존도, 로스앤젤레스/롱비치 항만 단지 등으로 인해 스모그 형태의 대기오염에 시달리고 있습니다. 로스앤젤레스 분지와 샌 페르난도 계곡은 도로 차량, 비행기, 기관차, 운송, 제조 및 기타 공급원의 배기 가스에 포함된 대기 역전 현상에 취약합니다.[124] 도시의 차량에서 나오는 작은 입자 오염(폐로 침투하는 종류)의 비율은 55%까지 올라갈 수 있습니다.[citation needed]

스모그 시즌은 약 5월부터 10월까지 지속됩니다.[125] 다른 대도시들이 스모그를 없애기 위해 비에 의존하는 반면, 로스앤젤레스에는 매년 15인치(380mm)의 비가 내립니다: 오염은 여러 날에 걸쳐 연속적으로 축적됩니다. 로스앤젤레스를 비롯한 주요 도시의 대기 질 문제는 대기 청정법을 포함한 초기 국가 환경 법안의 통과로 이어졌습니다. 이 법안이 통과되었을 때, 캘리포니아는 오래된 차량에 의해 발생하는 로스앤젤레스의 오염 수준 때문에 새로운 공기 질 기준을 충족시킬 수 있는 주 시행 계획을 만들 수 없었습니다.[126] 보다 최근에, 캘리포니아 주는 배출가스가 적은 자동차를 의무화함으로써 오염을 줄이기 위해 전국적으로 노력하고 있습니다. 스모그는 전기 자동차와 하이브리드 자동차, 대중 교통의 개선, 그리고 다른 조치들을 포함한, 그것을 줄이기 위한 적극적인 조치들 때문에 앞으로 몇 년 동안 계속 감소할 것으로 예상됩니다.

로스앤젤레스의 1단계 스모그 경보의 수는 1970년대 연간 100개 이상에서 새 천년에는 거의 0개로 감소했습니다.[127] 개선에도 불구하고, 미국 폐 협회의 2006년과 2007년 연례 보고서는 이 도시를 단기 입자 오염과 연중 입자 오염으로 미국에서 가장 오염된 도시로 선정했습니다.[128] 2008년, 이 도시는 두 번째로 가장 오염이 심한 도시로 선정되었고, 일년 내내 가장 오염이 심한 도시로 다시 선정되었습니다.[129] 서울시는 2010년 도시 전력의 20%를 재생 가능한 자원으로 공급한다는 목표를 달성했습니다.[130] 미국 폐 협회(American Lung Association)의 2013년 조사에 따르면, 이 도시는 미국에서 최악의 스모그를 가지고 있으며, 단기 및 연중 오염량 모두에서 4위를 차지하고 있습니다.[131]

로스앤젤레스는 또한 미국에서 가장 큰 도시 유전의 본거지이기도 합니다. 도시의 가정, 교회, 학교 및 병원에서 1,500피트(460m) 이내에 700개 이상의 활성 유정이 있으며, 이에 대해 EPA는 심각한 우려를 표명했습니다.[132]

이 도시에는 도시 인구의 보브캣(링스 루퍼스)이 있습니다.[133] 망치는 이 인구의 흔한 문제입니다.[133] Serieys et al. 2014는 여러 위치에서 면역 유전학의 선택을 발견했지만 이것이 미래의 맹장 발병에서 살아남는 데 도움이 되는 실제 차이를 생성한다는 것을 입증하지 못했습니다.[133]

인구통계학

| 인구조사 | Pop. | 메모 | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1850 | 1,610 | — | |

| 1860 | 4,385 | 172.4% | |

| 1870 | 5,728 | 30.6% | |

| 1880 | 11,183 | 95.2% | |

| 1890 | 50,395 | 350.6% | |

| 1900 | 102,479 | 103.4% | |

| 1910 | 319,198 | 211.5% | |

| 1920 | 576,673 | 80.7% | |

| 1930 | 1,238,048 | 114.7% | |

| 1940 | 1,504,277 | 21.5% | |

| 1950 | 1,970,358 | 31.0% | |

| 1960 | 2,479,015 | 25.8% | |

| 1970 | 2,811,801 | 13.4% | |

| 1980 | 2,968,528 | 5.6% | |

| 1990 | 3,485,398 | 17.4% | |

| 2000 | 3,694,820 | 6.0% | |

| 2010 | 3,792,621 | 2.6% | |

| 2020 | 3,898,747 | 2.8% | |

| 2022년 (에스티) | 3,819,538 | [134] | −2.0% |

| 미국 인구조사국[135] 2010–2020, 2021[7] | |||

2010년 미국 인구조사에[136] 따르면 로스앤젤레스의 인구는 3,792,621명이었습니다.[137] 인구 밀도는 평방 마일당 8,092.3명(3,124.5명/km2)이었습니다. 연령 분포는 18세 미만이 87만4525명(23.1%), 18세 이상이 43만4478명(11.5%), 25세 이상이 120만9367명(31.9%), 45세 이상이 87만7555명(23.1%), 65세 이상이 39만6696명([137]10.5%)이었습니다. 평균 연령은 34.1세였습니다. 여성 100명당 남성은 99.2명이었습니다. 18세 이상의 여성 100명당 97.6명의 남성이 있었습니다.[137]

주택은 1[137],413,995가구로 2005-2009년 동안 1,298,350가구보다 증가하여 제곱마일당 평균 2,812.8가구(1,086.0가구/km2)의 밀도를 보였으며, 이 중 503,863가구(38.2%)가 소유자이고, 81만 4,305가구(61.8%)가 임대인이 차지했습니다. 주택 소유자 공실률은 2.1%, 임대 공실률은 6.1%였습니다. 1,535,444명(인구의 40.5%)이 자가주택에, 2,172,576명(57.3%)이 자가주택에 거주했습니다.[137]

2010년 미국 인구조사에 따르면 로스앤젤레스의 가구 소득은 중간값이 49,497달러로 인구의 22.0%가 연방 빈곤선 이하에서 살고 있습니다.[137]

인종과 민족

| 인종 및 민족 구성 | 1940[138] | 1970[138] | 1990[138] | 2010[139] | 2020[139] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 히스패닉 또는 라틴계 (어떤 인종이든) | 7.1% | 17.1% | 39.9% | 48.5% | 46.9% |

| 화이트(히스패닉이 아닌) | 86.3% | 61.1% | 37.3% | 28.7% | 28.9% |

| 아시아계(히스패닉계가 아닌) | 2.2% | 3.6% | 9.8% | 11.1% | 11.7% |

| 흑인 또는 아프리카계 미국인(히스패닉이 아닌) | 4.2% | 17.9% | 14.0% | 9.2% | 8.3% |

| 기타(히스패닉이 아닌) | 해당 없음 | 해당 없음 | 0.1% | 0.3% | 0.7% |

| 2개 이상의 경주(히스패닉이 아닌) | 해당 없음 | 해당 없음 | 해당 없음 | 2.0% | 3.3% |

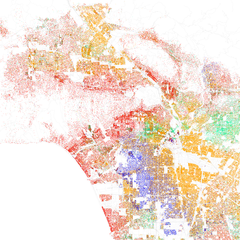

2010년 인구 조사에 따르면, 로스앤젤레스의 인종 구성은 백인 1,888,158명(49.8%), 아프리카계 미국인 365,118명(9.6%), 북미 원주민 28,215명(0.7%), 아시아인 42만 6,959명(11.3%), 태평양 섬 주민 5577명(0.1%), 기타 인종 902,959명(23.8%), 2개 이상의 인종 175,635명(4.6%)으로 구성되어 있습니다.[137] 모든 인종의 히스패닉 또는 라틴계는 1,838,822명 (48.5%)이었습니다. 로스앤젤레스에는 140개국 이상의 사람들이 224개의 다른 언어를 사용하고 있습니다.[140] 차이나타운, 히스토리컬 필리핀타운, 코리아타운, 리틀아르메니아, 리틀에티오피아, 테흐랑글스, 리틀도쿄, 리틀방글라데시, 타이타운과 같은 민족적 거주지는 로스앤젤레스의 다민족적 특성의 예를 보여줍니다.

비히스패닉계 백인은 1940년 86.3%에 [137]비해 2010년에는 28.7%였습니다.[138] 비히스패닉계 백인 인구의 대다수는 태평양 연안 지역뿐만 아니라 태평양 팰리세이드에서 로스 펠리즈에 이르는 산타모니카 산맥 인근 및 인근 지역에 살고 있습니다.

멕시코 혈통은 도시 인구의 31.9%로 히스패닉계가 가장 많고, 살바도르(6.0%)와 과테말라(3.6%)가 그 뒤를 이었습니다. 히스패닉 인구는 오랫동안 멕시코계 미국인과 중미인 공동체를 형성하고 있으며 로스앤젤레스 시 전체와 수도권 지역에 잘 퍼져 있습니다. 다운타운 주변의 이스트 로스앤젤레스, 북동 로스앤젤레스, 웨스트레이크 지역에 가장 많이 집중되어 있습니다. 게다가, 다우니를 향한 사우스 로스앤젤레스 동부 지역의 주민들의 대다수는 히스패닉계 출신입니다.[citation needed]

가장 큰 아시아 민족은 필리핀인(3.2%)과 한국인(2.9%)으로 윌셔 센터에 있는 한인타운과 역사적인 필리핀타운 등 그들만의 고유한 민족적 거주지를 가지고 있습니다.[141] 로스앤젤레스 인구의 1.8%를 차지하는 중국인들은 대부분 로스앤젤레스 시 경계 밖에 거주하며, 오히려 동부 로스앤젤레스 카운티의 샌 가브리엘 계곡에 거주하지만, 특히 차이나타운에 상당한 규모를 차지합니다.[142] 차이나타운과 타이타운은 또한 로스앤젤레스 인구의 각각 0.3%와 0.1%를 차지하는 많은 태국인과 캄보디아인들의 고향입니다. 일본인들은 LA 인구의 0.9%를 차지하고 있으며, 도시의 시내에 리틀 도쿄(Little Tokyo)가 설립되어 있으며, 또 다른 일본계 미국인들의 중요한 공동체는 웨스트 로스앤젤레스(West Los Angeles)의 소텔(Sawtelle) 지역에 있습니다. 베트남인은 로스앤젤레스 인구의 0.5%를 차지합니다. 인도인은 도시 인구의 0.9%를 차지합니다. 이 도시는 또한 아르메니아인, 아시리아인, 이란인들의 고향이며, 그들 중 많은 이들이 리틀 아르메니아와 테흐랑글레스와 같은 지역에 살고 있습니다.[citation needed]

1960년대 이후 미국 서부에서 가장 큰 아프리카계 미국인 공동체로 부상한 사우스 로스앤젤레스에서 아프리카계 미국인이 우세한 인종 집단이었습니다. 미국 흑인들이 가장 많이 거주하는 사우스 로스앤젤레스 지역에는 크렌쇼, 볼드윈 힐스, 라이머트 파크, 하이드 파크, 그래머시 파크, 맨체스터 스퀘어, 와츠 등이 있습니다.[143] 사우스 로스앤젤레스를 제외하고, 미드 시티와 미드 윌셔처럼 로스앤젤레스 중부 지역의 지역들도 아프리카계 미국인들의 집중도가 중간 정도입니다.[citation needed] 페어팩스 지역에는 상당한 규모의 에리트레아와 에티오피아 공동체가 있습니다.[144]

로스앤젤레스는 도시별로 멕시코, 아르메니아, 살바도르, 필리핀, 과테말라 인구가 세계에서 두 번째로 많고, 캐나다 인구는 세계에서 세 번째로 많고, 일본, 이란, 페르시아, 캄보디아, 루마니아(집시) 인구가 가장 많습니다.[145] 이탈리아 공동체는 산페드로에 집중되어 있습니다.[146]

로스앤젤레스의 외국인 출생 인구의 대부분은 멕시코, 엘살바도르, 과테말라, 필리핀 그리고 한국에서 태어났습니다.[147]

종교

퓨 리서치 센터의 2014년 연구에 따르면, 기독교는 로스앤젤레스에서 가장 널리 행해지고 있는 종교입니다(65%).[148][149] 로마 가톨릭 로스앤젤레스 대교구는 미국에서 가장 큰 대교구입니다.[150] 로저 마호니 추기경은 대주교로서 2002년 9월 로스앤젤레스 다운타운에 개관한 천사의 성모 대성당의 건축을 감독했습니다.[151]

2011년, 한때 흔했지만 결국에는 소멸된, 1781년 로스앤젤레스 시의 설립을 기념하기 위해 누에스트라 세뇨라 데 로스 앙헬레스에게 경의를 표하는 행렬과 미사를 집전하는 관습이 앤젤스 여왕 재단과 설립자 마크 앨버트에 의해 부활했습니다. 로스앤젤레스 대교구와 여러 시민 지도자들의 지원으로.[152] 최근에 부활한 관습은 1782년 로스앤젤레스 건국 1주년에 시작하여 그 후 거의 한 세기 동안 계속된 원래의 행렬과 미사를 이어온 것입니다.

수도권에 62만 1천 명의 유대인이 살고 있는 이 지역은 미국에서 뉴욕 다음으로 두 번째로 많은 유대인 인구를 가지고 있습니다.[153] 보일 하이츠는 제한적인 주택 계약 때문에 제2차 세계 대전 이전에 유대인 인구가 많았음에도 불구하고, 로스앤젤레스의 많은 유대인들은 현재 웨스트사이드와 샌 페르난도 계곡에 살고 있습니다. 주요 정교회 유대인 지역에는 핸콕 공원, 피코로버트슨, 밸리 빌리지 등이 있으며, 엔시노와 타르자나 지역에는 유대인 이스라엘인들이, 베벌리 힐스에는 페르시아인 유대인들이 대표적입니다. 로스앤젤레스 지역에는 종교개혁, 보수, 정통파, 재건파 등 다양한 종류의 유대교가 있습니다. 1923년에 지어진 이스트 로스앤젤레스의 브리드 스트리트 슐은 수십 년 초에 시카고 서쪽에서 가장 큰 유대교 회당이었습니다. 더 이상 유대교 회당으로 일상적으로 사용되지 않고 박물관과 커뮤니티 센터로 전환되고 있습니다.[154][155] 카발라 센터도 도시에 존재합니다.[156]

포스퀘어 복음의 국제 교회는 1923년 Aimee Semple McPherson에 의해 로스앤젤레스에 설립되어 오늘날까지도 그곳에 본부를 두고 있습니다. 수년 동안 교회는 건설 당시 이 나라에서 가장 큰 교회 중 하나였던 안젤루스 신전에서 소집되었습니다.[157]

로스앤젤레스는 풍부하고 영향력 있는 개신교 전통을 가지고 있습니다. 로스앤젤레스에서 최초의 개신교 예배는 1850년 개인 가정에서 열린 감리회였으며, 현재까지도 운영되고 있는 가장 오래된 개신교 교회인 제1회 회중교회는 1867년에 설립되었습니다.[158] 1900년대 초, 로스앤젤레스 성경 연구소는 기독교 근본주의 운동의 창립 문서를 출판했고 아주사 거리 부흥 운동은 오순절주의를 시작했습니다.[158] 메트로폴리탄 커뮤니티 교회도 로스앤젤레스 지역에 기원을 두고 있습니다.[159] 이 도시의 중요한 교회로는 할리우드 제1장로회, 벨 에어 장로회, 로스앤젤레스 제1아프리카 감리교 성공회, 그리스도 안에 계신 웨스트 로스앤젤레스 하나님의 교회, 두 번째 침례교회, 크렌쇼 기독교 센터, 매카티 메모리얼 기독교 교회, 첫 회중 교회가 있습니다.

예수 그리스도 후기성도 교회가 운영하는 두 번째로 큰 사원인 로스앤젤레스 캘리포니아 사원은 로스앤젤레스 웨스트우드 인근의 산타 모니카 대로에 있습니다. 1956년에 지어진 이 사원은 캘리포니아에 세워진 예수 그리스도 후기성도 교회의 첫 번째 사원으로 완공되었을 때 세계에서 가장 컸습니다.[160]

로스엔젤레스의 할리우드 지역에는 또한 몇몇 중요한 본사, 교회, 그리고 셀러브리티 사이언톨로지 센터가 있습니다.[161][162]

로스엔젤레스의 다민족 인구가 많기 때문에 불교, 힌두교, 이슬람교, 조로아스터교, 시크교, 바하 ʼ교, 다양한 동방 정교회, 수피즘, 신도교, 도교, 유교, 중국 민속 종교 등 다양한 종교가 있습니다. 예를 들어, 아시아에서 온 이민자들은 이 도시를 세계에서 가장 다양한 불교 신자들의 고향으로 만드는 많은 중요한 불교 신도단을 형성했습니다. 1875년 이 도시에 최초의 불교 조스 하우스가 설립되었습니다.[158] 이 도시는 미국 서부의 교회되지 않은 벨트에서 가장 큰 도시이기 때문에, 무신론과 다른 세속적인 믿음들도 흔합니다.

노숙

2020년 1월 현재 로스앤젤레스 시에는 41,290명의 노숙자가 있으며, 이는 LA 카운티 노숙자 인구의 약 62%를 차지합니다.[163] 이는 전년 대비 14.2% 증가한 수치입니다(LA County의 전체 노숙자 인구는 12.7% 증가).[164][165] 로스앤젤레스 노숙의 진원지는 스키드 로우(Skid Row) 지역으로, 미국에서 가장 안정적인 노숙자 인구 중 하나인 8,000명의 노숙자가 거주하고 있습니다.[166][167] 로스앤젤레스의 노숙자 인구 증가는 주거 비용의[168] 부족과 물질 남용 때문입니다.[169] 2019년에 새로 노숙자가 된 82,955명 중 거의 60%가 그들의 노숙이 경제적 어려움 때문이라고 말했습니다.[164] 로스앤젤레스에서 흑인들은 노숙을 경험할 가능성이 대략 4배나 높습니다.[164][170]

경제.

로스앤젤레스의 경제는 국제 무역, 엔터테인먼트(텔레비전, 영화, 비디오 게임, 음악 녹음 및 제작), 항공 우주, 기술, 석유, 패션, 의류 및 관광에 의해 주도됩니다.[citation needed] 다른 중요한 산업에는 금융, 통신, 법률, 의료 및 운송이 포함됩니다. 2017년 글로벌 금융 센터 지수에서 로스앤젤레스는 뉴욕, 샌프란시스코, 시카고, 보스턴, 워싱턴 D.C.에 이어 세계에서 19번째로 경쟁력 있는 금융 센터이자 미국에서 6번째로 경쟁력 있는 곳으로 선정되었습니다.[171]

5개의 주요 영화 스튜디오 중 파라마운트 픽처스만이 로스앤젤레스의 도시 경계 내에 있습니다;[172] 그것은 남부 캘리포니아에 있는 엔터테인먼트 본사의 이른바 30마일 구역에 위치하고 있습니다.

로스앤젤레스는 미국에서 가장 큰 제조업 중심지입니다.[173] 로스앤젤레스와 롱비치의 인접한 항구는 모두 미국에서 가장 붐비는 항구이자 환태평양 지역 내 무역에 필수적인 세계에서 다섯 번째로 붐비는 항구입니다.[173]

로스앤젤레스 대도시권은 1.0조 달러(2018년[update] 기준)가 넘는 대도시권으로 [24]뉴욕과 도쿄에 이어 세계에서 세 번째로 큰 경제 대도시권입니다.[24] 러프버러 대학의 2012년 연구에 따르면, 로스앤젤레스는 "알파 세계 도시"로 분류되었습니다.[174]

대마초 규제부는 2016년 대마초 판매 및 유통이 합법화된 후 대마초 입법을 시행하고 있습니다.[175] 2019년[update] 10월 현재 300개 이상의 기존 대마초 사업체(소매업체와 공급업체 모두)가 국내 최대 시장으로 간주되는 곳에서 운영할 수 있는 승인을 받았습니다.[176][177]

2018년[update] 현재, 로스앤젤레스에는 AECOM, CBRE Group 및 Reliance Steel & Aluminium Co.의 포춘 500대 기업이 있습니다.[178] 로스앤젤레스와 그 주변 대도시 지역에 본사를 둔 다른 회사들은 The Aerospace Corporation, California Pizza Kitchen,[179] Capital Group Company, Deluxe Entertainment Services Group, Dine Brands Global, DreamWorks Animation, Dollar Shave Club, Fandango Media, Farmers Insurance Group, Forever 21, Hulu, Panda Express, SpaceX, 유비소프트 필름 앤 텔레비전, 월트 디즈니 컴퍼니, 유니버설 픽처스, 워너 브라더스, 워너 뮤직 그룹, 그리고 트레이더 조스.

| 2022년[180] 6월 로스앤젤레스 카운티에서 가장 큰 비정부 고용주 | ||

|---|---|---|

| 순위 | 고용주 | 직원들. |

| 1 | 카이저 퍼머넌트 | 40,303 |

| 2 | 서던캘리포니아 대학교 | 22,735 |

| 3 | 노스롭 그루먼사 | 18,000 |

| 4 | 시더스-시나이 메디컬 센터 | 16,659 |

| 5 | 타겟사 | 15,888 |

| 6 | 얼라이드 유니버셜 | 15,326 |

| 7 | 남부 캘리포니아 주 프로비던스 보건 및 서비스 | 14,935 |

| 8 | 랄프스/푸드4리스(Kroger Co. 분할) | 14,000 |

| 9 | 월마트 | 14,000 |

| 10 | 월트 디즈니사 | 12,200 |

문화예술

로스앤젤레스는 종종 세계의 창조적인 수도라고 불리는데, 그 이유는 그곳의 거주민들 중 여섯 명 중 한 명이 창조적인[181] 산업에 종사하고 있고, 세계 역사상 그 어느 때보다도 더 많은 예술가, 작가, 영화 제작자, 배우, 댄서, 음악가들이 로스앤젤레스에 살고 있기 때문입니다.[182] 이 도시는 또한 벽화가 많은 것으로 유명합니다.[183]

랜드마크

로스앤젤레스의 건축은 스페인, 멕시코, 미국의 뿌리에서 영향을 받았습니다. 이 도시의 인기 있는 스타일로는 스페인 식민지 부흥 스타일, 미션 부흥 스타일, 캘리포니아 츄리게레스크 스타일, 지중해 부흥 스타일, 아트 데코 스타일, 미드 센추리 모던 스타일 등이 있습니다.

Important landmarks in Los Angeles include the Hollywood Sign,[184] Walt Disney Concert Hall, Capitol Records Building,[185] the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels,[186] Angels Flight,[187] Grauman's Chinese Theatre,[188] Dolby Theatre,[189] Griffith Observatory,[190] Getty Center,[191] Getty Villa,[192] Stahl House,[193] the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum, L.A. Live,[194] 로스앤젤레스 카운티 미술관, 베니스 운하 역사지구 및 보드워크, 테마 빌딩, 브래드버리 빌딩, US 뱅크 타워, 윌셔 그랜드 센터, 할리우드 대로, 로스앤젤레스 시청, 할리우드 볼,[195] 전함 USS 아이오와, 와츠 타워,[196] 스테이플스 센터, 다저 스타디움, 올베라 스트리트.[197]

영화와 공연예술

공연 예술은 로스앤젤레스의 문화적 정체성에 중요한 역할을 합니다. USC Stevens Institute for Innovation에 따르면 "매주 1,100개 이상의 연극 제작과 21개의 오프닝이 있습니다."[182] 로스앤젤레스 뮤직 센터는 연간 130만 명 이상의 방문객이 방문하는 "전국 3대 공연 예술 센터" 중 하나입니다.[198] 음악 센터의 중심 작품인 월트 디즈니 콘서트 홀은 명망 있는 로스앤젤레스 필하모닉의 본거지입니다.[199] Center Theatre Group, Los Angeles Master Chorale, 그리고 Los Angeles Opera와 같은 주목할 만한 단체들도 Music Center의 상주 회사들입니다.[200][201][202] 콜번 스쿨과 USC 쏜튼 음악 학교와 같은 최고의 기관에서 인재를 양성하고 있습니다.

이 도시의 할리우드 지역은 20세기 초부터 이러한 구분을 유지하며 영화 산업의 중심지로 인식되어 왔으며, 로스앤젤레스 지역 또한 텔레비전 산업의 중심지와 관련이 있습니다.[203] 이 도시는 주요 영화 스튜디오와 주요 음반사의 본거지입니다. 로스앤젤레스는 매년 열리는 아카데미 시상식, 프라임타임 에미상 시상식, 그래미상 시상식뿐만 아니라 많은 다른 연예 산업 시상식을 주최합니다. 로스앤젤레스는 미국에서 가장 오래된 영화학교인 USC 영화예술학교가 있는 곳입니다.[204]

박물관과 갤러리

로스엔젤레스 카운티에는 841개의 박물관과 미술관이 있는데,[205] 이는 미국의 다른 도시들보다 1인당 더 많은 박물관입니다.[205] 주목할만한 박물관 중 일부는 로스엔젤레스 카운티 미술관(미국[206] 서부에서 가장 큰 미술관), 게티 센터(세계에서 가장 부유한 예술 기관인[207] J. Paul Getty Trust의 일부), 페테르센 자동차 박물관,[208] 헌팅턴 도서관,[209] 자연사 박물관,[210] 군함 아이오와,[211] 더 브로드, 2,000여점의 현대 미술[212] 작품을 소장하고 있습니다.[213] 상당수의 미술관들이 갤러리 로우에 있으며, 수만 명의 미술관들이 매달 열리는 다운타운 아트 워크에 참여하고 있습니다.[214]

도서관

로스앤젤레스 공립 도서관 시스템은 도시에서 72개의 공립 도서관을 운영하고 있습니다.[215] 편입되지 않은 지역의 엔클레이브는 로스앤젤레스 카운티 공공 도서관의 분관에서 서비스를 제공하는데, 분관들 중 많은 분관들이 도보 거리에 있습니다.[216]

요리.

로스앤젤레스의 음식 문화는 로스앤젤레스의 풍부한 이민자 역사와 인구가 가져온 세계적인 요리의 융합입니다. 2022년 현재 미슐랭 가이드는 2개의 레스토랑에 별 2개를 부여하고 8개의 레스토랑에 별 1개를 부여하는 10개의 레스토랑을 인정했습니다.[217]

중남미 이민자들, 특히 멕시코 이민자들은 타코, 부리토, 케사디야, 토르타, 타말레, 엔칠라다를 푸드 트럭과 가판대, 타케리아, 카페에서 제공했습니다. 많은 이민자들이 소유한 아시아 음식점들은 차이나타운,[218] 코리아타운,[219] 리틀 도쿄에 핫스팟이 있는 도시 곳곳에 존재합니다.[220] 로스앤젤레스는 또한 비건, 채식주의자 및 식물성 옵션의 대규모 제공을 제공합니다.

스포츠

로스앤젤레스와 그 대도시 지역은 11개의 최고 수준의 프로 스포츠 팀들의 본거지이며, 그들 중 몇몇은 인근 지역 사회에서 활동하지만 그들의 이름으로 로스앤젤레스를 사용합니다. 이 팀들은 메이저 리그 야구의 로스엔젤레스[221] 다저스와 로스엔젤레스 에인절스[222], 전미 미식축구 리그의 로스엔젤레스 램스와[223] 로스엔젤레스 차저스, 전미 농구 협회의 로스엔젤레스 레이커스와[224] 로스엔젤레스 클리퍼스[225], 내셔널 하키 리그 (NHL)의 로스앤젤레스 킹스와[226] 애너하임 덕스[227], 메이저 리그 사커 (MLS)의 로스앤젤레스 갤럭시와[228] 로스앤젤레스 FC[229], 그리고 미국 여자 농구 협회 (WNBA)의 로스앤젤레스 스파크스.[230]

다른 주목할 만한 스포츠 팀으로는 미국 대학 체육 협회(NCAA)의 UCLA 브루인스와 USC 트로이인스가 있으며, 둘 다 Pac-12 컨퍼런스의 디비전 I 팀이지만 곧 빅텐 컨퍼런스로 이동할 예정입니다.[231]

로스앤젤레스는 미국에서 두 번째로 큰 도시이지만 1995년과 2015년 사이에 NFL팀을 개최하지 않았습니다. 한 때, 로스앤젤레스 지역은 두 개의 NFL 팀인 램스와 레이더스를 개최했습니다. 1995년 램스 가족이 세인트루이스로 이주하면서 둘 다 도시를 떠났습니다. 루이스와 레이더스는 원래 고향인 오클랜드로 이사를 갑니다. 세인트루이스에서 21시즌을 보낸 후. 2016년 1월 12일, NFL은 램스가 4시즌 동안 로스앤젤레스 메모리얼 콜리세움에서 홈경기를 치르며 2016년 NFL 시즌을 위해 로스앤젤레스로 다시 이동할 것이라고 발표했습니다.[232][233][234] 1995년 이전에 램스는 1946년부터 1979년까지 콜리세움에서 홈 경기를 치렀고, 이를 통해 로스앤젤레스에서 경기를 한 최초의 프로 스포츠 팀이 되었고, 1980년부터 1994년까지 애너하임 스타디움으로 이동했습니다. 2017년 1월 12일, 샌디에이고 차저스는 (1960년 창단 시즌 이후 처음으로) 로스앤젤레스로 다시 이전하고 2017년 NFL 시즌부터 로스앤젤레스 차저스가 되어 캘리포니아 카슨의 디그니티 헬스 스포츠 파크에서 세 시즌 동안 경기를 할 것이라고 발표했습니다.[235] 램스 앤 더 차저스(Rams and the Chargers)는 2020 시즌 동안 인근 잉글우드(Inglewood)에 위치한 새로 지어진 소피 스타디움(Sofi Stadium)으로 곧 이동할 예정입니다.[236]

로스앤젤레스는 다저 스타디움, 로스앤젤레스 메모리얼 콜리세움, BMO 스타디움, Crypto.com 아레나 등 많은 스포츠 경기장을 자랑합니다. 포럼, 소피 스타디움, 디그니티 헬스 스포츠 파크, 로즈 볼, 엔젤 스타디움, 혼다 센터도 로스앤젤레스 대도시권의 인접한 도시들에 있습니다.[241]

로스앤젤레스는 1932년과 1984년에 하계 올림픽을 두 번 개최했고, 2028년에 세 번째로 올림픽을 개최할 것입니다.[242] 로스앤젤레스는 런던 (1908년, 1948년, 2012년)과 파리 (1900년, 1924년, 2024년)에 이어 세 번째로 올림픽을 개최하는 도시가 될 것입니다. 1932년 제10회 올림픽이 개최되었을 때, 이전의 10번가는 올림픽 Blvd로 이름이 바뀌었습니다. 로스앤젤레스는 1985년에[243] 청각 장애인 올림픽과 2015년에 스페셜 올림픽을 개최하기도 했습니다.[244]

8개의 NFL 슈퍼볼 또한 도시와 그 주변 지역에서 열렸습니다 - 메모리얼 콜리세움 (첫 번째 슈퍼볼, I and VII)에서 2개, 패서디나 교외의 로즈볼에서 5개(XI, XIV, XVII, XXI, XXII), 그리고 교외의 잉글우드 (LVI)[245]에서 1개. 로즈 볼은 또한 매년 새해 첫날마다 열리는 로즈 볼이라고 불리는 매년 그리고 매우 명망 있는 NCAA 대학 미식축구 경기를 개최합니다.

로스앤젤레스는 또한 1994년 로즈볼에서 브라질이 우승한 결승전을 포함하여 8번의 FIFA 월드컵 축구 경기를 개최했습니다. 로즈볼은 1999년 FIFA 여자 월드컵에서도 결승전을 포함해 4경기를 치렀는데, 미국이 중국을 상대로 페널티킥으로 승리했습니다. 이 경기는 브랜디 차스테인이 대회 우승 페널티킥을 성공시킨 후 셔츠를 벗는 경기로 상징적인 이미지를 만들었습니다. 로스앤젤레스는 2026년 FIFA 월드컵을 위한 미국의 11개 개최 도시 중 하나가 될 것이며, 경기는 소피 스타디움에서 열릴 예정입니다.[246]

로스앤젤레스(Los Angeles)는 북미 5개 메이저 리그(MLB, NFL, NHL, NBA, MLS)에서 모두 우승을 차지한 6개의 도시 중 하나로 2012년 킹스 스탠리컵 우승과 함께 위업을 완수했습니다.[247]

정부

로스앤젤레스는 일반적인 법률 도시와는 대조적인 전세 도시입니다. 현재의 헌장은 1999년 6월 8일에 채택되어 여러 번 개정되었습니다.[248] 선출된 정부는 시장-의회 정부 하에서 운영되는 로스앤젤레스 시의회와 로스앤젤레스 시장으로 구성되며, 시 검사(지방 검사, 카운티 사무소와 혼동하지 않음)와 통제관으로 구성됩니다. 시장은 Karen Bass입니다.[249] 15개의 시의회 구역이 있습니다.

이 도시에는 로스앤젤레스 경찰국(LAPD),[250] 로스앤젤레스 경찰 위원회,[251] 로스앤젤레스 소방국(LAFD),[252] 로스앤젤레스 시 주택청(HACLA),[253] 로스앤젤레스 교통국(LADOT),[254] 로스앤젤레스 공공 도서관(LAPL) 등 많은 부서와 임명된 경찰관들이 있습니다.[255]

1999년 유권자들에 의해 비준된 로스앤젤레스 시의 헌장은 지역에 거주하거나, 일을 하거나, 부동산을 소유하는 사람들로 정의되는 다양한 이해 관계자들을 대표하는 자문 지역 의회의 체계를 만들었습니다. 지방의회는 스스로의 경계를 파악하고, 스스로의 내규를 정하고, 스스로의 사무관을 선출한다는 점에서 비교적 자율적이고 자발적입니다. 90여 개의 동네 의회가 있습니다.

로스앤젤레스 주민들은 1, 2, 3, 4대 감독구의 감독관을 선출합니다.

연방 및 주 대표부

캘리포니아 주 의회에서, 로스앤젤레스는 14개의 지역구로 나누어져 있습니다.[256] 캘리포니아 주 상원에서, 그 도시는 8개의 지역구로 나누어져 있습니다.[257] 미국 하원에서는 9개의 의회 구역으로 나누어져 있습니다.[258]

범죄

1992년 로스앤젤레스 시는 1,092건의 살인을 기록했습니다.[259] 로스앤젤레스는 1990년대와 2000년대 후반에 범죄가 크게 줄었고 2009년에는 314건의 살인사건으로 50년 만에 최저치를 기록했습니다.[260][261] 이는 인구 10만 명당 7.85명으로, 10만 명당 34.2명의 살인율이 보고된 1980년에 비해 크게 감소한 수치입니다.[262][263] 여기에는 15건의 경찰관 관련 총격 사건이 포함되었습니다. 한 번의 총격으로 인해 LAPD 역사상 처음으로 SWAT 팀원인 Randal Simmons가 사망했습니다.[264] 2013년 로스앤젤레스에서는 총 251건의 살인사건이 발생하였는데, 이는 전년도에 비해 16퍼센트 감소한 수치입니다. 경찰은 이 감소가 젊은이들이 온라인에서 더 많은 시간을 보내는 것을 포함한 여러 가지 요인에서 비롯되었다고 추측합니다.[265] 2021년에 살인은 2008년 이후 가장 높은 수준으로 증가했고 348건이 있었습니다.[266]

2015년, LAPD가 8년 동안 범죄를 과소 신고했다는 것이 밝혀지면서, 도시의 범죄율은 실제보다 훨씬 낮아졌습니다.[267][268]

드랙나 범죄 가족과 코헨 범죄 가족은 금지령[269] 시대에 도시에서 조직적인 범죄를 지배했으며 1940년대와 1950년대에 미국 마피아의 일부로 "일몰지 전투"로 절정에 달했지만, 이후 1960년대 말과 1970년대 초에 다양한 흑인 및 히스패닉 갱단이 부상하면서 점차 쇠퇴했습니다.[269]

로스앤젤레스 경찰국에 따르면, 이 도시에는 450개의 갱단으로 조직된 45,000명의 갱단원들이 살고 있습니다.[270] 그 중에는 남 로스앤젤레스 지역에서 시작된 아프리카계 미국인 거리 갱단인 크립스와 블러드스가 있습니다. 멕시코계 미국인 거리 갱단인 수레뇨스(Surenos)나 살바도르계를 중심으로 활동하는 마라 살바트루차(Mara Salvatrucha) 등 라틴계 거리 갱단은 모두 로스앤젤레스에서 활동했습니다. 이로 인해 이 도시는 "미국의 강 수도"로 불리게 되었습니다.[271]

교육

단과대학

도시 경계 내에는 캘리포니아 주립 대학교 로스앤젤레스(CSULA), 캘리포니아 주립 대학교 노스리지(CSUN), 캘리포니아 주립 대학교 로스앤젤레스(UCLA) 등 3개의 공립 대학이 있습니다.[272]

시내의 사립 대학은 다음과 같습니다.

- 미국 영화 연구소 음악원[273]

- 앨리언트 국제 대학교[274]

- 미국 연극 아카데미 (로스앤젤레스 캠퍼스)[275]

- 미국 유대인 대학[276]

- 에이브러햄 링컨 대학교[277]

- 미국 뮤지컬 드라마 아카데미 – 로스앤젤레스 캠퍼스

- 안티오크 대학교 로스앤젤레스 캠퍼스[278]

- 찰스 R. 드류 의과대학[279]

- 콜번 스쿨[280]

- 컬럼비아 칼리지 할리우드[281]

- 에머슨 칼리지 (로스앤젤레스 캠퍼스)[282]

- 황제대학[283]

- 패션 디자인 머천다이징 연구소의 로스앤젤레스 캠퍼스(FIDM)

- 로스앤젤레스 영화학교[284]

- Loyola Marymount University (LMU는 Loyola Law School의 모체 대학이기도 함)[285]

- 세인트 산 메리스 칼리지[286]

- 캘리포니아[287] 국립 대학교

- 옥시덴탈 칼리지 ("Oxy")[288]

- 오티스 예술 디자인 대학 (Otis)[289]

- 서던캘리포니아 건축연구소 (SCI-Arc)[290]

- 사우스웨스턴 로스쿨[291]

- 서던캘리포니아 대학교 (USC)[292]

- 우드베리 대학교[293]

커뮤니티 칼리지 시스템은 로스앤젤레스 커뮤니티 칼리지 디스트릭트의 수탁자에 의해 관리되는 9개의 캠퍼스로 구성됩니다.

미국에서 가장 선별적인 교양 대학들을 포함하는 클레어몬트 칼리지 컨소시엄과 세계 최고의 STEM 중심 연구 기관 중 하나인 캘리포니아 공과대학(Caltech)을 포함하여 로스앤젤레스 지역에는 도시 경계 밖에 수많은 추가 대학들이 있습니다.

학교

로스앤젤레스 통합 교육구는 학생 수가 약 800,000명으로 로스앤젤레스 시의 거의 모든 지역과 주변 여러 커뮤니티에 서비스를 제공합니다.[303] 1978년 주민발의안 13이 승인된 후, 도시 학군은 자금 조달에 상당한 어려움을 겪었습니다. LAUSD는 162개의 Magnet 학교가 지역 사립학교와 경쟁하는 데 도움이 되지만, 자금이 부족하고, 과밀하며, 유지보수가 제대로 되지 않는 캠퍼스로 유명해졌습니다.

로스앤젤레스의 몇몇 작은 구역은 잉글우드 통합 교육구와 [304]라스 버진 통합 교육구에 있습니다.[305] 로스앤젤레스 카운티 교육청은 로스앤젤레스 카운티 예술 고등학교를 운영하고 있습니다.

미디어

로스앤젤레스 메트로 지역은 5,431,140가구(미국의 4.956%)가 거주하는 미국에서 두 번째로 큰 방송 지정 시장 지역으로, 다양한 지역 AM 및 FM 라디오 및 텔레비전 방송국이 서비스하고 있습니다. 7개의 VHF 할당이 할당된 미디어 시장은 로스앤젤레스와 뉴욕 두 곳뿐입니다.[306]

이 지역의 주요 일간 영자 신문은 로스앤젤레스 타임즈입니다.[307] 라 오피니온(La Opinión)은 스페인의 주요 일간지입니다.[308] 코리아 타임즈는 그 도시의 주요 일간지이고 월드 저널은 그 도시와 군의 주요한 중국 신문입니다. 로스앤젤레스 센티넬은 서부 미국에서 가장 큰 아프리카계 미국인 독자층을 자랑하는 도시의 주요 아프리카계 미국인 주간지입니다.[309] Investor's Business Daily는 Playa del Rey에 본사를 둔 LA 법인 사무실에서 배포됩니다.[310]

이 지역의 창의적인 산업의 일환으로 ABC, CBS, FOX, NBC 등 4대 방송 텔레비전 네트워크는 모두 로스앤젤레스의 여러 지역에 생산 시설과 사무실을 갖추고 있습니다. 4개의 주요 방송 텔레비전 네트워크와 주요 스페인어 방송 네트워크인 Telemundo와 Univision은 또한 로스앤젤레스 시장에 서비스를 제공하고 각 네트워크의 서해안 대표 방송국 역할을 하는 방송국을 소유 및 운영하고 있습니다. ABC의 KABC-TV(채널 7),[311] CBS의 KCBS-TV(채널 2), 폭스의 KTTV(채널 11),[312] NBC의 KNBC-TV(채널 4),[313] 마이네트워크TV의 KCOP-TV(채널 13), 텔레문도의 KVEA-TV(채널 52), 유니비전의 KMEX-TV(채널 34). 이 지역에는 또한 4개의 PBS 방송국이 있으며, KCET는 지난 8년 동안 국내 최대의 독립 공중파 방송국으로 보낸 후 2019년 8월에 2차 제휴로 네트워크에 다시 합류했습니다. KTBN (Channel 40)은 Santa Ana를 기반으로 하는 종교 삼위일체 방송망의 주력 방송국입니다. KCAL-TV(채널 9)와 KTLA-TV(채널 5)와 같은 다양한 독립 텔레비전 방송국도 이 지역에서 운영됩니다.

또한 로스앤젤레스 레지스터, 로스앤젤레스 커뮤니티 뉴스(로스앤젤레스 광역 지역에 초점을 맞춘), 로스앤젤레스 데일리 뉴스(샌 페르난도 밸리에 초점을 맞춘), LA 위클리, LA 위클리 등 소규모 지역 신문, 대체 주간지 및 잡지도 다수 있습니다. 레코드([314]로스앤젤레스 지역 음악계에 초점을 맞춘), 로스앤젤레스 매거진, 로스앤젤레스 비즈니스 저널, 로스앤젤레스 데일리 저널(법률 산업 신문), 할리우드 리포터, 버라이어티(연예 산업 신문), 로스앤젤레스 다운타운 뉴스. 주요 논문 외에도 아르메니아어, 영어, 한국어, 페르시아어, 러시아어, 중국어, 일본어, 히브리어, 아랍어 등 수많은 지역 정기 간행물이 이민자 커뮤니티를 모국어로 서비스하고 있습니다. 로스앤젤레스와 인접한 많은 도시들은 또한 특정 로스앤젤레스 지역과 중복되는 보도와 이용 가능성이 있는 자체 일간지를 가지고 있습니다. 예를 들면 데일리 브리즈 (사우스 베이 서비스)와 롱비치 프레스 텔레그램이 있습니다.

로스앤젤레스의 예술, 문화 및 야간 생활 뉴스도 Time Out Los Angeles, Thrillist, Kristin's List, Daily Candy, Diversity News Magazine, LAist 및 Flavorpill 등 많은 지역 및 전국 온라인 가이드에서 다루고 있습니다.[315][316][317][318]

사회 기반 시설

교통.

프리웨이즈

도시와 로스앤젤레스 대도시권의 나머지 지역은 고속도로와 고속도로의 광범위한 네트워크에 의해 서비스되고 있습니다. 텍사스 교통 연구소(Texas Transportation Institute)의 연례 도시 이동 보고서(Urban Mobility Report)는 여행자 1인당 연간 지연으로 측정한 2019년 로스앤젤레스 지역 도로가 미국에서 가장 혼잡한 지역으로 선정되었으며, 해당 지역 주민들은 그해 교통 체증으로 평균 119시간을 대기했습니다.[319] 로스앤젤레스가 그 뒤를 이었습니다. 샌프란시스코/오클랜드, 워싱턴 D.C., 마이애미가 그 뒤를 이었습니다. 이 도시의 혼잡에도 불구하고, 로스앤젤레스의 통근자들의 평균 하루 이동 시간은 뉴욕, 필라델피아, 시카고를 포함한 다른 주요 도시들보다 짧습니다. 로스앤젤레스의 2006년 평균 통근 시간은 29.2분으로 샌프란시스코와 워싱턴 D.C.와 비슷했습니다.[320]

LA와 미국의 나머지 지역을 연결하는 주요 고속도로는 샌디에이고를 거쳐 멕시코의 티후아나까지 이어지는 5번 주간 고속도로와 새크라멘토, 포틀랜드, 시애틀을 거쳐 캐나다까지 이어지는 도로입니다.미국 국경; 미국 최남단 동서 해안간 고속도로인 10번 고속도로, 플로리다 잭슨빌로 가는 10번 고속도로; 그리고 캘리포니아 센트럴 코스트, 샌프란시스코, 레드우드 엠파이어, 그리고 오리건과 워싱턴 해안으로 향하는 101번 국도.

버스

LACMTA(Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transport Authority)와 기타 지역 기관은 Los Angeles County를 커버하는 포괄적인 버스 시스템을 제공합니다. 로스앤젤레스 교통부가 지역 버스와 통근 버스 계약을 담당하는 반면,[321] 도시에서 가장 큰 버스 시스템은 메트로가 운영합니다.[322] 로스앤젤레스 메트로 버스(Los Angeles Metro Busway)라고 불리는 이 시스템은 로스앤젤레스 카운티 전역에 걸쳐 117개의 노선(메트로 버스웨이 제외)으로 구성되어 있으며, 대부분의 노선은 도시의 거리 그리드에서 특정 거리를 따라 로스앤젤레스 시내로 또는 시내로 운행됩니다.[323] 이 시스템은 2023년 3분기 기준으로 평일 평균 약 692,500명의 승객을 보유하고 있으며, 2022년에는 총 197,950,700명의 승객을 보유하고 있습니다.[324] 메트로는 또한 두 개의 메트로 버스웨이 노선인 G 노선과 J 노선을 운영하고 있는데, 이 노선들은 로스앤젤레스의 경전철과 비슷한 정류장과 주파수를 가진 버스 급행 환승 노선입니다.

주로 특정 도시나 지역에 서비스를 제공하는 소규모 지역 시스템도 있습니다. 예를 들어, 빅 블루 버스는 샌타모니카에서 광범위한 서비스를 제공하는 반면, 풋힐 트랜짓은 샌 가브리엘 계곡의 노선에 초점을 맞추고 있습니다. 로스앤젤레스 월드 공항은 또한 로스앤젤레스 유니언 역과 반 누이스에서 로스앤젤레스 국제 공항까지 (자유로를 통해) 두 개의 빈번한 플라이 어웨이 고속 버스 노선을 운영하고 있습니다.[325]

모든 버스에서 현금을 받을 수 있지만 로스앤젤레스 메트로 버스, 메트로 버스웨이 및 기타 27개 지역 버스 대리점의 주요 결제 수단은 비접촉식 저장 가치 카드인 TAP 카드입니다.[326] 2016년 American Community Survey에 따르면, 일하는 로스앤젤레스(도시) 거주자의 9.2%가 대중교통을 통해 출근길에 올랐습니다.[327]

레일

로스앤젤레스 카운티 교통국은 또한 로스앤젤레스와 그 카운티 전역에 지하철과 경전철 시스템을 운영하고 있습니다. 이 시스템은 로스앤젤레스 메트로 레일(Los Angeles Metro Rail)이라고 불리며 B, D 지하철 노선과 A, C, E, K 경전철 노선으로 구성되어 있습니다.[323] TAP 카드는 모든 메트로 레일 여행에 필요합니다.[328] 2023년 3/4분기 현재, 이 도시의 지하철은 미국에서 9번째로 붐비고 경전철은 미국에서 두 번째로 붐비고 있습니다.[324] 2022년 시스템의 탑승 인원은 57,299,800명으로, 2023년 3분기 평일 기준 약 189,200명입니다.[324]

1990년 첫 번째 노선인 A선이 개통된 이후, 현재 더 많은 연장이 진행되고 있는 가운데, 이 시스템은 크게 연장되었습니다. 오늘날 이 시스템은 롱비치, 패서디나, 산타모니카, 노워크, 엘 세군도, 노스 할리우드, 잉글우드, 다운타운 로스앤젤레스 등 107.4마일(172.8km)의 철도 위에 군 전역의 수많은 지역에 서비스를 제공합니다. 2023년 기준으로 메트로 레일에는 101개의 역이 있습니다.[329]

로스앤젤레스는 또한 로스앤젤레스에서 벤추라, 오렌지, 리버사이드, 샌버나디노 및 샌디에고 카운티까지 연결하는 카운티의 통근 철도 시스템인 메트로링크의 중심지이기도 합니다. 이 시스템은 선로 545.6마일(878.1킬로미터)에서 운행되는 8개의 선로와 69개의 정거장으로 구성되어 있습니다.[330] 메트로링크는 평일 평균 42,600회 운행되며, 가장 혼잡한 노선은 샌버나디노 선입니다.[331] 메트로링크 외에도 로스앤젤레스는 암트랙에서 5개 노선의 시외 여객 열차로 다른 도시들과 연결되어 있습니다.[332] 그 노선들 중 하나는 유니언 역을 통해 샌디에이고와 캘리포니아 주 샌루이스 오비스포 사이를 매일 왕복으로 운행하는 퍼시픽 서프라이너 노선입니다.[333] 그것은 북동 회랑 밖에서 암트랙의 가장 붐비는 노선입니다.[334]

이 도시의 주요 기차역은 1939년에 개장한 유니언역이며, 미국 서부에서 가장 큰 여객 철도 터미널입니다.[335] 이 역은 암트랙, 메트로링크, 메트로 레일의 주요 지역 기차역입니다. 이 역은 암트랙에서 다섯 번째로 붐비는 역으로, 2019년 140만 명의 암트랙 탑승 및 디보딩이 있습니다.[336] Union Station은 또한 Metro Bus, Greyhound, LAX FlyAway 및 다른 기관의 버스를 이용할 수 있습니다.[337]

공항

로스앤젤레스에 서비스를 제공하는 주요 국제 및 국내 공항은 로스앤젤레스 국제공항(IATA: LAX, ICAO: KLAX)으로, 일반적으로 공항 코드인 LAX로 지칭됩니다.[338] 그것은 잉글우드의 소피 스타디움 근처 로스앤젤레스 서쪽에 위치해 있습니다.

그 밖의 주요 상업 공항은 다음과 같습니다.

- (IATA: ONT, ICAO: KONT) 온타리오 국제공항은 캘리포니아주 온타리오시가 소유하고 있으며, 내륙 제국에 서비스를 제공하고 있습니다.[339]

- (IATA: BUR, ICAO: KBUR) 할리우드 버뱅크 공항, 버뱅크 시, 글렌데일 시, 패서디나 시가 공동 소유하고 있습니다. 이전에는 밥 호프 공항과 버뱅크 공항으로 알려졌었는데, 로스앤젤레스 다운타운에서 가장 가까운 공항으로 샌 페르난도, 샌 가브리엘, 앤텔로프 계곡이 있습니다.[340]

- (IATA: LGB, ICAO: KLGB) 롱비치 공항, 롱비치/하버 지역에 서비스를 제공합니다.[341]

- (IATA: SNA, ICAO: KSNA) 존 웨인 오렌지 카운티 공항.

세계에서 가장 바쁜 종합 항공 공항 중 하나가 로스앤젤레스에 있습니다. 반 누이스 공항 (IATA: VNY, ICAO: KVNY).[342]

항구

로스앤젤레스 항구는 다운타운에서 남쪽으로 약 20마일(32km) 떨어진 산페드로 인근의 산페드로 만에 있습니다. 로스앤젤레스 항구와 월드포트 LA라고도 불리는 이 항구 단지는 해안가 43마일(69km)을 따라 7,500에이커(30km2)의 땅과 물을 차지하고 있습니다. 그것은 별개의 롱비치 항구와 접해 있습니다.[343]

로스앤젤레스 항구와 롱비치 항구는 함께 로스앤젤레스/롱비치 항구를 구성합니다.[344][345] 두 항구를 합치면, 2008년에는 1,420만 TEU 이상의 무역량으로 세계에서 다섯 번째로 붐비는 컨테이너 항구입니다.[346] 로스앤젤레스 항은 미국에서 가장 붐비는 컨테이너 항구이자 미국 서부 해안에서 가장 큰 유람선 중심지입니다. 로스앤젤레스 항의 월드 크루즈 센터는 2014년 약 590,000명의 승객에게 서비스를 제공했습니다.[347]

로스앤젤레스 해안선을 따라 규모가 작고 비산업적인 항구들도 있습니다. 이 항구에는 빈센트 토마스 다리, 헨리 포드 다리, 롱비치 국제 관문 다리, 그리고 슈일러 F 코모도어 등 4개의 다리가 있습니다. 하임교. Catalina Express는 San Pedro에서 Santa Catalina 섬의 Avalon 시(및 Two Harbors)로 가는 여객선 서비스를 제공합니다.

주목할 만한 사람들

자매도시

로스앤젤레스에는 25개의 자매 도시가 있으며,[348] 연도별로 나열되어 있습니다.

이스라엘 아일라트(Eilat) (1959)

이스라엘 아일라트(Eilat) (1959) 일본 나고야 (1959)

일본 나고야 (1959) 브라질 살바도르 (1962)

브라질 살바도르 (1962) 보르도, 프랑스 (1964)[349][350]

보르도, 프랑스 (1964)[349][350] 독일 베를린 (1967)[351]

독일 베를린 (1967)[351] 잠비아 루사카 (1968)

잠비아 루사카 (1968) 멕시코시티 (1969)

멕시코시티 (1969) 뉴질랜드 오클랜드 (1971)

뉴질랜드 오클랜드 (1971) 부산, 대한민국 (1971)

부산, 대한민국 (1971) 인도 뭄바이 (1972)

인도 뭄바이 (1972) 이란 테헤란 (1972)

이란 테헤란 (1972) 타이완 타이베이 (1979)

타이완 타이베이 (1979) 중국 광저우 (1981)[352]

중국 광저우 (1981)[352] 그리스 아테네 (1984)

그리스 아테네 (1984) 러시아 상트페테르부르크 (1984)

러시아 상트페테르부르크 (1984) 캐나다 밴쿠버 (1986)[353]

캐나다 밴쿠버 (1986)[353] 기자, 이집트 (1989)

기자, 이집트 (1989) 인도네시아 자카르타 (1990)

인도네시아 자카르타 (1990) 카우나스, 리투아니아 (1991)

카우나스, 리투아니아 (1991) 마카티, 필리핀 (1992)

마카티, 필리핀 (1992) 스플리트, 크로아티아 (1993)[354]

스플리트, 크로아티아 (1993)[354] 산살바도르, 엘살바도르 (2005)

산살바도르, 엘살바도르 (2005) 레바논 베이루트 (2006)

레바논 베이루트 (2006) 이탈리아 캄파니아주 이스키아 (2006)

이탈리아 캄파니아주 이스키아 (2006) 아르메니아 예레반 (2007)[355]

아르메니아 예레반 (2007)[355]

또한 로스앤젤레스에는 다음과 같은 "우정 도시"가 있습니다.

참고 항목

참고문헌

- ^ a b c Gollust, Shelley (April 18, 2013). "Nicknames for Los Angeles". Voice of America. Archived from the original on July 6, 2014. Retrieved June 26, 2014.

- ^ Barrows, H.D. (1899). "Felepe de Neve". Historical Society of Southern California Quarterly. Vol. 4. p. 151ff. Archived from the original on November 6, 2023. Retrieved September 28, 2011.

- ^ "This 1835 Decree Made the Pueblo of Los Angeles a Ciudad – And California's Capital". KCET. April 2016. Archived from the original on January 28, 2018. Retrieved January 27, 2018.

- ^ "California Cities by Incorporation Date". California Association of Local Agency Formation Commissions. Archived from the original (DOC) on February 21, 2013. Retrieved August 25, 2014.

- ^ "About the City Government". City of Los Angeles. Archived from the original on February 8, 2015. Retrieved February 8, 2015.

- ^ a b "2021 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on September 7, 2021. Retrieved September 7, 2021.

- ^ a b c d "QuickFacts: Los Angeles city, California". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on October 1, 2021. Retrieved January 21, 2023.

- ^ "List of 2020 Census Urban Areas". census.gov. United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on January 14, 2023. Retrieved January 8, 2023.

- ^ "2020 Population and Housing State Data". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on August 12, 2021. Retrieved August 22, 2021.

- ^ "Angelino, Angeleno, and Angeleño". KCET. January 10, 2011. Archived from the original on February 19, 2023. Retrieved November 4, 2022.

- ^ "Definition of ANGELENO". Merriam-Webster. May 16, 2023. Archived from the original on April 20, 2022. Retrieved April 20, 2022.

- ^ "Total Gross Domestic Product for Los Angeles-Long Beach-Anaheim, CA (MSA)". fred.stlouisfed.org.

- ^ "Total Gross Domestic Product for Riverside-San Bernardino-Ontario, CA (MSA)". fred.stlouisfed.org.

- ^ "Total Gross Domestic Product for Oxnard-Thousand Oaks-Ventura, CA (MSA)". fred.stlouisfed.org.

- ^ 2017년 7월 13일, 로스앤젤레스 시의 우편번호가 Wayback Machine – LAHD에 보관되었습니다.

- ^ "Nicknames for Los Angeles, California". www.laalmanac.com. Archived from the original on January 2, 2022. Retrieved January 2, 2022.

- ^ "Slowing State Population Decline puts Latest Population at 39,185,000" (PDF). dof.ca.gov. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 12, 2022. Retrieved June 12, 2022.

- ^ "미국에서 가장 많이 방문한 10개 도시" 2023년 6월 14일, 월드 아틀라스 웨이백 머신(Wayback Machine), 2021년 9월 23일 보관

- ^ a b Estrada, William David (2009). The Los Angeles Plaza: Sacred and Contested Space. University of Texas Press. pp. 15–50. ISBN 978-0-292-78209-9.

- ^ "Subterranean L.A.: The Urban Oil Fields". The Getty Iris. July 16, 2013. Archived from the original on January 1, 2016. Retrieved December 31, 2015.

- ^ LaRocco, Lori Ann (September 24, 2022). "New York is now the nation's busiest port in a historic tipping point for U.S.-bound trade". CNBC. Archived from the original on June 10, 2023. Retrieved May 22, 2023.

- ^ "Port of NYNJ Beats West Coast Rivals with Highest 2023 Volumes". The Maritime Executive. Archived from the original on May 11, 2023. Retrieved May 22, 2023.

- ^ "Port of New York and New Jersey Remains US' Top Container Port". www.marinelink.com. December 28, 2022. Archived from the original on May 11, 2023. Retrieved May 22, 2023.

- ^ a b c "Table 3.1. GDP & Personal Income". U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. 2018. Archived from the original on October 23, 2018. Retrieved April 6, 2019.

- ^ Hayley Smith (October 13, 2022). "Los Angeles is running out of water, and time. Are leaders willing to act?". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 13, 2022. Retrieved October 14, 2022.

- ^ a b Smith, Hayley (March 1, 2022). "California drought continues after state has its driest January and February on record". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 9, 2022. Retrieved November 23, 2022.

- ^ a b "Settlement of Los Angeles". Los Angeles Almanac. Archived from the original on September 2, 2018. Retrieved September 2, 2018.

- ^ "Ooh L.A. L.A." Los Angeles Times. December 12, 1991. Archived from the original on January 11, 2022. Retrieved October 24, 2021.

- ^ Pool, Bob (March 26, 2005). "City of Angels' First Name Still Bedevils Historians". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 21, 2021. Retrieved October 24, 2021.

- ^ a b Stein, David Allen (1953). "Los Angeles: A Noble Fight Nobly Lost". Names. 1 (1): 35–38. doi:10.1179/nam.1953.1.1.35.

- ^ Masters, Nathan (February 24, 2011). "The Crusader in Corduroy, the Land of Soundest Philosophy, and the 'G' That Shall Not Be Jellified". KCET. Public Media Group of Southern California. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ^ Masters, Nathan (May 6, 2016). "How to Pronounce "Los Angeles," According to Charles Lummis". KCET. Public Media Group of Southern California. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ^ Lummis, Charles Fletcher (June 29, 1908). "This Is the Way to Pronounce Los Angeles". Nebraska State Journal. p. 4. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ^ a b c Harvey, Steve (June 26, 2011). "Devil of a time with City of Angels' name". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ^ Kenyon, John Samuel; Knott, Thomas Albert (1944). A Pronouncing Dictionary of American English. Springfield, Mass.: G. & C. Merriam. p. 260.

- ^ Buntin, John (2009). L.A. Noir: The Struggle for the Soul of America's Most Seductive City. New York: Harmony Books. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-307-35207-1.

- ^ Jones, Daniel (2011). Roach, Peter; Setter, Jane; Esling, John (eds.). Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary (18th ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-15255-6.

- ^ Windsor Lewis, Jack (1990). "HappY land reconnoitred: the unstressed word-final -y vowel in General British pronunciation". In Ramsaran, Susan (ed.). Studies in the Pronunciation of English: A Commemorative Volume in Honour of A.C. Gimson. Routledge. pp. 159–167. ISBN 978-1-138-92111-5. Archived from the original on May 18, 2023. Retrieved June 12, 2023. 166~167페이지.

- ^ Bowman, Chris (July 8, 2008). "Smoke is Normal – for 1800". The Sacramento Bee. Archived from the original on July 9, 2008. Retrieved October 6, 2011.

- ^ Gordon J. MacDonald. "Environment: Evolution of a Concept" (PDF). p. 2. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 27, 2013. Retrieved April 16, 2013.

The Native American name for Los Angeles was Yang na, which translates into "the valley of smoke."

- ^ Bright, William (1998). Fifteen Hundred California Place Names. University of California Press. p. 86. ISBN 978-0-520-21271-8. LCCN 97043147. Archived from the original on November 6, 2023. Retrieved October 17, 2015.

Founded on the site of a Gabrielino Indian village called Yang-na, or iyáangẚ, 'poison-oak place.'

- ^ Sullivan, Ron (December 7, 2002). "Roots of native names". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on December 18, 2014. Retrieved January 7, 2015.

Los Angeles itself was built over a Gabrielino village called Yangna or iyaanga', 'poison oak place.'

- ^ Willard, Charles Dwight (1901). The Herald's History of Los Angeles. Los Angeles: Kingsley-Barnes & Neuner. pp. 21–24. ISBN 978-0-598-28043-5. Archived from the original on November 6, 2023. Retrieved September 29, 2011.

- ^ "Portola Expedition 1769 Diaries". Pacifica Historical Society. Archived from the original on November 13, 2015. Retrieved January 7, 2015.

- ^ Leffingwell, Randy; Worden, Alastair (November 4, 2005). California missions and presidios. Voyageur Press. pp. 43–44. ISBN 978-0-89658-492-1. Archived from the original on November 6, 2023. Retrieved September 30, 2011.

- ^ Mulroy, Kevin; Taylor, Quintard; Autry Museum of Western Heritage (March 2001). "The Early African Heritage in California (Forbes, Jack D.)". Seeking El Dorado: African Americans in California. University of Washington Press. p. 79. ISBN 978-0-295-98082-9. Archived from the original on November 6, 2023. Retrieved September 30, 2011.

- ^ Guinn, James Miller (1902). Historical and biographical record of southern California: containing a history of southern California from its earliest settlement to the opening year of the twentieth century. Chapman pub. co. p. 63. Archived from the original on March 18, 2023. Retrieved September 30, 2011.

- ^ Estrada, William D. (2006). Los Angeles's Olvera Street. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-3105-2. Archived from the original on November 6, 2023. Retrieved September 30, 2011.

- ^ "Pio Pico, Afro Mexican Governor of Mexican California". African American Registry. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved January 24, 2017.

- ^ "Monterey County Historical Society, Local History Pages--Secularization and the Ranchos, 1826-1846". mchsmuseum.com. Archived from the original on October 20, 2021. Retrieved October 26, 2017.

- ^ Bauer, K. Jack (1993). The Mexican War, 1846-1848 (Bison books ed.). Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. p. 184. OCLC 25746154.

- ^ Guinn, James Miller (1902). Historical and biographical record of southern California: containing a history of southern California from its earliest settlement to the opening year of the twentieth century. Chapman pub. co. p. 50. Archived from the original on March 18, 2023. Retrieved September 30, 2011.

- ^ Mulholland, Catherine (2002). William Mulholland and the Rise of Los Angeles. University of California Press. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-520-23466-6. Archived from the original on November 6, 2023. Retrieved September 30, 2011.

- ^ Kipen, David (2011). Los Angeles in the 1930s: The WPA Guide to the City of Angels. University of California Press. pp. 45–46. ISBN 978-0-520-26883-8. Archived from the original on November 6, 2023. Retrieved September 30, 2011.

- ^ "Population of the 100 Largest Urban Places: 1900". United States Census Bureau. June 15, 1998. Archived from the original on February 15, 2015. Retrieved January 8, 2015.

- ^ "The Los Angeles Aqueduct and the Owens and Mono Lakes (MONO Case)". American University. Archived from the original on January 9, 2015. Retrieved January 8, 2015.

- ^ Reisner, Marc (1993). Cadillac desert: the American West and its disappearing water. Penguin. p. 86. ISBN 978-0-14-017824-1. Archived from the original on November 6, 2023. Retrieved September 30, 2011.

- ^ Basiago, Andrew D. (February 7, 1988), Water For Los Angeles – Sam Nelson Interview, The Regents of the University of California, 11, archived from the original on August 4, 2019, retrieved October 7, 2013

- ^ Annexation and Detachment Map (PDF) (Map). City of Los Angeles Bureau of Engineering. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 1, 2017. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

- ^ Creason, Glen (September 26, 2013). "CityDig: L.A.'s 20th Century Land Grab". Lamag - Culture, Food, Fashion, News & Los Angeles. Los Angeles Magazine. Archived from the original on September 29, 2013. Retrieved October 10, 2013.

- ^ Weiss, Marc A (1987). The Rise of the Community Builders: The American Real Estate Industry and Urban Land Planning. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 80–86. ISBN 978-0-231-06505-4.

- ^ Buntin, John (April 6, 2010). L.A. Noir: The Struggle for the Soul of America's Most Seductive City. Random House Digital, Inc. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-307-35208-8. Archived from the original on November 6, 2023. Retrieved September 30, 2011.

- ^ Young, William H.; Young, Nancy K. (March 2007). The Great Depression in America: a cultural encyclopedia. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-313-33521-1. Archived from the original on November 6, 2023. Retrieved September 30, 2011.

- ^ "Population of the 100 Largest Urban Places: 1930". United States Census Bureau. June 15, 1998. Archived from the original on April 28, 2015. Retrieved January 8, 2015.

- ^ 파커, 데이나 T. 승리 구축: 제2차 세계 대전 로스앤젤레스 지역에서의 항공기 제조, pp.5–8, 14, 26, 36, 50, 60, 78, 94, 108, 122, Cycles, 2013. ISBN 978-0-9897906-0-4.

- ^ Bruegmann, Robert (November 1, 2006). Sprawl: A Compact History. University of Chicago Press. p. 133. ISBN 978-0-226-07691-1. Archived from the original on November 6, 2023. Retrieved October 1, 2011.

- ^ Braun, Michael. "The economic impact of theme parks on regions" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on December 7, 2021. Retrieved November 4, 2021.

- ^ Jennings, Jay (February 26, 2021). Beverly Park: L.A.'s Kiddieland, 1943–74. Independently published. ISBN 979-8713878917.

- ^ Hinton, Elizabeth (2016). From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime: The Making of Mass Incarceration in America. Harvard University Press. pp. 68–72. ISBN 9780674737235. Archived from the original on November 6, 2023. Retrieved May 15, 2022.

- ^ Hafner, Katie; Lyon, Matthew (August 1, 1999). Where Wizards Stay Up Late: The Origins Of The Internet. Simon and Schuster. p. 153. ISBN 978-0-684-87216-2. Archived from the original on November 6, 2023. Retrieved October 1, 2011.

- ^ Vronsky, Peter (2004). Serial Killers: The Method and Madness of Monsters. Penguin. p. 187. ISBN 0-425-19640-2.

- ^ Woo, Elaine (June 30, 2004). "Rodney W. Rood, 88; Played Key Role in 1984 Olympics, Built Support for Metro Rail". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on December 13, 2011. Retrieved October 1, 2011.

- ^ Zarnowski, C. Frank (Summer 1992). "A Look at Olympic Costs" (PDF). Citius, Altius, Fortius. 1 (1): 16–32. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 28, 2008. Retrieved October 1, 2011.

- ^ Rucker, Walter C.; Upton, James N.; Hughey, Matthew W. (2007). "Los Angeles (California) Riots of 1992". Encyclopedia of American race riots. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 376–85. ISBN 978-0-313-33301-9. Archived from the original on November 6, 2023. Retrieved October 1, 2011.

- ^ Wilson, Stan (April 25, 2012). "Riot anniversary tour surveys progress and economic challenges in Los Angeles". CNN. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved January 23, 2015.

- ^ Reich, Kenneth (December 20, 1995). "Study Raises Northridge Quake Death Toll to 72". Los Angeles Times. p. B1. Archived from the original on December 13, 2011. Retrieved October 1, 2011.

- ^ "Rampart Scandal Timeline". PBS Frontline. Archived from the original on March 4, 2012. Retrieved October 1, 2011.

- ^ Orlov, Rick (November 3, 2012). "Secession drive changed San Fernando Valley, Los Angeles". Los Angeles Daily News. Archived from the original on December 25, 2014. Retrieved January 12, 2015.

- ^ "Karen Bass elected mayor, becoming first woman to lead L.A." Los Angeles Times. November 16, 2022. Archived from the original on November 17, 2022. Retrieved November 18, 2022.

- ^ Horowitz, Julia (August 1, 2017). "Los Angeles will host 2028 Olympics". CNNMoney. Archived from the original on July 31, 2017.

- ^ "Cities Which Have Hosted Multiple Summer Olympic Games". worldatlas. Archived from the original on December 15, 2016.

- ^ "2010 Census U.S. Gazetteer Files – Places – California". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "Elevations of the 50 Largest Cities (by population, 1980 Census)". United States Geological Survey. Archived from the original on October 2, 2011. Retrieved October 3, 2011.

- ^ "Mount Lukens Guide". Sierra Club Angeles Chapter. Archived from the original on November 24, 2011. Retrieved October 3, 2011.

- ^ "Google Maps". Google Maps. Archived from the original on May 31, 2022. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- ^ Gumprecht, Blake (March 2001). The Los Angeles River: Its Life, Death, and Possible Rebirth. JHU Press. p. 173. ISBN 978-0-8018-6642-5. Archived from the original on November 6, 2023. Retrieved October 3, 2011.

- ^ Miller, George Oxford (January 15, 2008). Landscaping with Native Plants of Southern California. Voyageur Press. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-7603-2967-2. Archived from the original on November 6, 2023. Retrieved October 6, 2011.

- ^ National Research Council (U.S.). Advisory Committee on Technology Innovation (1979). Tropical legumes: resources for the future : report of an ad hoc panel of the Advisory Committee on Technology Innovation, Board on Science and Technology for International Development, Commission on International Relations, National Research Council. National Academies. p. 258. NAP:14318. Archived from the original on November 6, 2023. Retrieved October 6, 2011.

- ^ "Flower". Los Angeles Magazine. Emmis Communications. April 2003. p. 62. ISSN 1522-9149. Archived from the original on November 6, 2023. Retrieved October 6, 2011.

- ^ "In 2023, let's add toyon to our native plant gardens and put an urban legend to rest". Los Angeles Times. December 29, 2022. Retrieved December 15, 2023.

- ^ "Earthquake Facts". United States Geological Survey. Archived from the original on October 10, 2011. Retrieved October 3, 2011.

- ^ Zielinski, Sarah (May 28, 2015). "What Will Really Happen When San Andreas Unleashes the Big One?". Smithsonian. Archived from the original on September 25, 2020. Retrieved September 6, 2020.

- ^ Shaw, John H.; Shearer, Peter M. (March 5, 1999). "An Elusive Blind-Thrust Fault Beneath Metropolitan Los Angeles". Science. 283 (5407): 1516–1518. Bibcode:1999Sci...283.1516S. doi:10.1126/science.283.5407.1516. PMID 10066170. S2CID 21556124.

- ^ "World's Largest Recorded Earthquake". Geology.com. Archived from the original on January 19, 2015. Retrieved January 12, 2015.

- ^ "Mapping L.A. Neighborhoods". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on May 12, 2019. Retrieved June 7, 2019.

- ^ "Los Angeles CA Zip Code Map". USMapGuide. Archived from the original on May 9, 2022. Retrieved June 6, 2019.

- ^ Abu-Lughod, Janet L. (1999). New York, Chicago, Los Angeles: America's global cities. U of Minnesota Press. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-8166-3336-4. Archived from the original on November 6, 2023. Retrieved October 2, 2011.

- ^ "LADOT". Archived from the original on September 7, 2015.

- ^ "Los Angeles tops worst cities for traffic in USA". USA TODAY. Archived from the original on January 1, 2016. Retrieved December 31, 2015.

- ^ a b "Summary of Monthly Normals 1991–2020". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 11, 2021.

- ^ Peel, M. C.; Finlayson B. L. & McMahon, T. A. (2007). "Updated world map of the Köppen−Geiger climate classification". Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 11 (5): 1633–1644. Bibcode:2007HESS...11.1633P. doi:10.5194/hess-11-1633-2007. ISSN 1027-5606.

- ^ "The Myth of a Desert Metropolis: Los Angeles was not built in a desert, but are we making it one?". Boom California. May 22, 2017. Archived from the original on March 8, 2019. Retrieved March 8, 2019.

- ^ "Interactive North America Koppen-Geiger Climate Classification Map". www.plantmaps.com. Archived from the original on March 8, 2019. Retrieved March 8, 2019.

- ^ a b "Historical Weather for Los Angeles, California, United States of America". Weatherbase.com. Archived from the original on January 11, 2012. Retrieved December 15, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Climatography of the United States No. 20 (1971–2000)" (PDF). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 2, 2013. Retrieved October 5, 2011.

- ^ "Pacific Ocean Temperatures on California Coast". beachcalifornia.com. Archived from the original on October 12, 2011. Retrieved October 5, 2011.

- ^ "Los Angeles Climate Guide". weather2travel.com. Archived from the original on October 5, 2011. Retrieved October 5, 2011.

- ^ "Climate of California". Western Regional Climate Center. Archived from the original on July 21, 2009. Retrieved October 6, 2011.

- ^ Poole, Matthew R. (September 22, 2010). Frommer's Los Angeles 2011. John Wiley & Sons. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-470-62619-1. Archived from the original on November 6, 2023. Retrieved October 5, 2011.

- ^ "Los Angeles Almanac – seasonal average rainfall". Archived from the original on December 27, 2021. Retrieved December 26, 2021.

- ^ Burt, Christopher C.; Stroud, Mark (June 26, 2007). Extreme weather: a guide & record book. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 100. ISBN 978-0-393-33015-1. Archived from the original on November 6, 2023. Retrieved October 5, 2011.

- ^ Frazin, Rachel (February 21, 2019). "Los Angeles sees first snow in years". The Hill. Capitol Hill Publishing Corp. Archived from the original on February 23, 2019. Retrieved April 6, 2019.

- ^ "Snow falling in Los Angeles, Pasadena and California's coastal cities". nbcnews.com. NBC Universal. February 22, 2019. Archived from the original on April 2, 2019. Retrieved April 6, 2019.

- ^ "Snow in Malibu? Weather provides surprise in Southern California". KUSA.com. January 25, 2021. Archived from the original on May 9, 2022. Retrieved January 28, 2021.

- ^ Pool, Bob; Lin II, Rong-Gong (September 27, 2010). "L.A.'s hottest day ever". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on December 13, 2011. Retrieved October 5, 2011.

- ^ National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. "Los Angeles/Oxnard". National Weather Service Forecast Office. Archived from the original on September 18, 2020. Retrieved September 9, 2020.

- ^ a b "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved July 18, 2020.

- ^ "Station Name: CA LOS ANGELES DWTN USC CAMPUS". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved July 18, 2020.

- ^ "LOS ANGELES/WBO CA Climate Normals". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved October 20, 2013.

- ^ "Historical UV Index Data - Los Angeles, CA". UV Index Today. Retrieved April 21, 2023.

- ^ "Station Name: CA LOS ANGELES INTL AP". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 9, 2014.

- ^ "Summary of Monthly Normals 1991–2020". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 11, 2021.

- ^ "WMO Climate Normals for LOS ANGELES/INTL, CA 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved April 17, 2014.

- ^ Stimson, Thomas E. (July 1955). "What can we do about smog?". Popular Mechanics: 65. ISSN 0032-4558. Archived from the original on November 6, 2023. Retrieved October 6, 2011.

- ^ "Smog Hangs Over Olympic Athletes". New Scientist: 393. August 11, 1983. ISSN 0262-4079. Retrieved October 6, 2011.

- ^ "1970년 캘리포니아 청정대기법 조기 시행" EPA 동문회 2019년 4월 12일 Wayback Machine에서 비디오, 녹취록 보관(p7, 10 참조). 2016년 7월 12일.

- ^ Marziali, Carl (March 4, 2015). "L.A.'s Environmental Success Story: Cleaner Air, Healthier Kids". USC News. Archived from the original on March 10, 2015. Retrieved March 16, 2015.

- ^ "Most Polluted Cities". American Lung Association. Archived from the original on January 7, 2015. Retrieved January 12, 2015.

- ^ "Pittsburgh and Los Angeles the most polluted US cities". citymayors.com. May 4, 2008. Archived from the original on October 2, 2011. Retrieved October 7, 2011.

- ^ "Los Angeles meets 20 percent renewable energy goal". Bloomberg News. January 14, 2011. Archived from the original on February 1, 2011. Retrieved October 7, 2011.

- ^ "American Lung Association State of the Air 2013 – Los Angeles-Long Beach-Riverside, CA". American Lung Association State of the Air 2013. Archived from the original on August 31, 2015. Retrieved September 1, 2015.

- ^ "EPA officers sickened by fumes at South L.A. oil field". Los Angeles Times. November 9, 2013. Archived from the original on April 8, 2016. Retrieved March 24, 2016.

- ^ a b c

- Lambert, Max R.; Brans, Kristien I.; Des Roches, Simone; Donihue, Colin M.; Diamond, Sarah E. (2021). "Adaptive Evolution in Cities: Progress and Misconceptions". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. Cell Press. 36 (3): 239–257. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2020.11.002. ISSN 0169-5347. PMID 33342595. S2CID 229342193.

- Serieys, Laurel E. K.; Lea, Amanda; Pollinger, John P.; Riley, Seth P. D.; Wayne, Robert K. (December 2, 2014). "Disease and freeways drive genetic change in urban bobcat populations". Evolutionary Applications. Blackwell. 8 (1): 75–92. doi:10.1111/eva.12226. ISSN 1752-4571. PMC 4310583. PMID 25667604. S2CID 27501058.

- ^ "Slowing state population decline puts latest population at 39,185,000" (PDF). Department of Finance. Sacramento. May 2, 2022. Archived from the original (Press Release) on May 25, 2022. Retrieved February 5, 2023.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 1, 2021. Retrieved March 19, 2007.

- ^ "2010 Census Interactive Population Search: CA — Los Angeles". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 24, 2014. Retrieved July 12, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Los Angeles (city), California". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 19, 2021. Retrieved October 3, 2016.

- ^ a b c d "Race and Hispanic Origin for Selected Cities and Other Places: Earliest Census to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on August 12, 2012. Retrieved November 6, 2015.

- ^ a b "2020: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171)". US Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 4, 2022. Retrieved July 4, 2022.

- ^ "Los Angeles, California Population 2019". World Population Review. Archived from the original on July 15, 2019. Retrieved August 21, 2019.

- ^ Shyong, Frank (January 6, 2020). "Here's how HIFI, or Historic Filipinotown got its name". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 6, 2020. Retrieved January 6, 2020.

- ^ "Welcome to Los Angeles Chinatown". chinatownla.com. Archived from the original on January 24, 2017. Retrieved June 10, 2015.

- ^ Ray, MaryEllen Bell (1985). The City of Watts, California: 1907 to 1926. Rising Pub. ISBN 978-0-917047-01-5.

- ^ Barkan, Elliott Robert (January 17, 2013). Immigrants in American History: Arrival, Adaptation, and Integration. Abc-Clio. p. 693. ISBN 9781598842197.

- ^ Hayden, Dolores (February 24, 1997). The Power of Place: Urban Landscapes as Public History. MIT Press. p. 83. ISBN 9780262581523. Archived from the original on November 6, 2023. Retrieved November 24, 2022.

- ^ Bitetti, Marge (2007). Italians in Los Angeles. Arcadia. ISBN 9780738547756. Archived from the original on April 27, 2023. Retrieved November 28, 2022.

- ^ "Los Angeles" (PDF). dornsife.usc.edu. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 21, 2023. Retrieved August 7, 2023.

- ^ a b "Religious Landscape Study: Adults in the Los Angeles Metro Area". Pew Research Center. 2014. Archived from the original on July 31, 2022. Retrieved June 26, 2023.

- ^ a b "America's Changing Religious Landscape". Pew Research Center: Religion & Public Life. May 12, 2015. Archived from the original on April 10, 2019. Retrieved July 30, 2015.

- ^ Pomfret, John (April 2, 2006). "Cardinal Puts Church in Fight for Immigration Rights". Washington Post. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved October 22, 2011.

- ^ Stammer, Larry B.; Becerra, Hector (September 4, 2002). "Pomp Past, Masses Flock to Cathedral". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 11, 2012. Retrieved October 22, 2011.

- ^ Dellinger, Robert (September 6, 2011). "2011 'Grand Procession' revives founding of L.A. Marian devotion" (PDF). The Tidings Online. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 22, 2014. Retrieved January 14, 2015.

- ^ "World Jewish Population". SimpleToRemember.com. Archived from the original on April 7, 2012. Retrieved October 23, 2011.

- ^ "Washington Symposium and Exhibition Highlight Restoration and Adaptive Reuse of American Synagogues". Jewish Heritage Report. No. 1. March 1997. Archived from the original on March 27, 2011. Retrieved October 23, 2011.

- ^ "Los Angeles's Breed Street Shul Saved by Politicians". Jewish Heritage Report. Vol. II, no. 1–2. Spring–Summer 1998. Archived from the original on March 27, 2011. Retrieved October 23, 2011.

- ^ Luscombe, Belinda (August 6, 2006). "Madonna Finds A Cause". Time Magazine. Archived from the original on August 19, 2006. Retrieved October 23, 2011.

- ^ Edith Waldvogel Blumhofer, Aimee Semple McPherson: 모두의 자매, Wm. B. Eerdmans 출판사, 1993, 246-247페이지

- ^ a b c Clifton L. Holland. "n Overview of Religion in Los Angeles from 1850 to 1930". Archived from the original on September 5, 2017. Retrieved September 18, 2017.

- ^ "History of MCC – Metropolitan Community Churches". www.mccchurch.org. Archived from the original on May 4, 2019. Retrieved April 28, 2019.

- ^ "LDS Los Angeles California Temple". The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Archived from the original on October 12, 2018. Retrieved October 23, 2011.

- ^ "Church of Scientology Celebrity Centre International". Church of Scientology Celebrity Centre International. Archived from the original on June 17, 2018. Retrieved June 17, 2018.

- ^ Miller, Daniel (July 21, 2011). "Scientology's Hollywood Real Estate Empire". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on July 18, 2021. Retrieved February 26, 2022.

- ^ "4558 – 2020 Greater Los Angeles Homeless Count Presentation". www.lahsa.org. Archived from the original on July 7, 2020. Retrieved July 6, 2020.

- ^ a b c Cowan, Jill (June 12, 2020). "What Los Angeles's Homeless Count Results Tell Us". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on June 12, 2020. Retrieved July 6, 2020.

- ^ Cowan, Jill (June 5, 2019). "Homeless Populations Are Surging in Los Angeles. Here's Why". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 27, 2020. Retrieved July 6, 2020.

- ^ "L.A. agrees to let homeless people keep skid row property — and some in downtown aren't happy". Los Angeles Times. May 29, 2019. Archived from the original on August 10, 2019. Retrieved August 19, 2019.

- ^ Cristi, Chris (June 13, 2019). "LA's homeless: Aerial view tour of Skid Row, epicenter of crisis". ABC7. Archived from the original on October 17, 2021. Retrieved June 19, 2019.

- ^ Cowan, Jill (June 5, 2019). "Homeless Populations Are Surging in Los Angeles. Here's Why". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 27, 2020. Retrieved September 5, 2019.

- ^ Doug Smith; Benjamin Oreskes (October 7, 2019). "Are many homeless people in L.A. mentally ill? New findings back the public's perception". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on June 3, 2022. Retrieved June 2, 2022.

- ^ "2823 – Report And Recommendations Of The Ad Hoc Committee On Black People Experiencing Homelessness". www.lahsa.org. Archived from the original on July 6, 2020. Retrieved July 6, 2020.

- ^ "The Global Financial Centres Index 21" (PDF). Long Finance. March 2017. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 11, 2017.

- ^ Slide, Anthony (February 25, 2014). The New Historical Dictionary of the American Film Industry. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-92554-3. Archived from the original on November 6, 2023. Retrieved January 2, 2022.

- ^ a b [http://www.city-data.com/us-cities/The-West/Los-Angeles-Economy.html site blacklisted "Los Angeles: Economy"]. City-Data. Retrieved October 7, 2011.

{{cite web}}: 확인.url=가치 (도움말) - ^ "The World According to GaWC 2012". Globalization and World Cities Research Network. Loughborough University. Archived from the original on March 20, 2014. Retrieved January 25, 2014.

- ^ Queally, James (December 13, 2019). "Dozens of unlicensed cannabis dispensaries raided in L.A. this week". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on December 13, 2019. Retrieved December 14, 2019.

- ^ Chiotakis, Steve (October 1, 2019). "Navigating LA's cannabis industry with the city's pot czar". KCRW. Archived from the original on October 30, 2019. Retrieved October 30, 2019.

- ^ REYES, EMILY ALPERT (October 29, 2019). "L.A. should suspend vetting applications for pot shops amid concerns, Wesson urges". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 30, 2019. Retrieved October 30, 2019.

- ^ "Fortune 500 Companies 2018: Who Made The List". Fortune. Meredith Corporation. Archived from the original on August 27, 2018. Retrieved April 13, 2015.

- ^ "Our Company: From a legendary pizza to a global brand". California Pizza Kitchen. Archived from the original on July 30, 2022. Retrieved July 30, 2022.

- ^ "City of Los Angeles' Comprehensive Annual Financial Report" (PDF). June 30, 2022. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 2, 2023.

- ^ "Is Los Angeles really the creative capital of the world? Report says yes". SmartPlanet. November 19, 2009. Archived from the original on April 9, 2014. Retrieved October 14, 2011.

- ^ a b "Only In LA: Tapping L.A. Innovation". University of Southern California. Archived from the original on October 2, 2011. Retrieved October 14, 2011.

- ^ Shatkin, Elina (August 28, 2013). "Let the Renaissance Begin: L.A. Votes to Lift Mural Ban". Los Angeles Magazine. Archived from the original on February 8, 2023. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ "The Hollywood Sign, Official website for one of the most iconic landmarks in the world". Hollywood sign.org. Archived from the original on July 16, 2023. Retrieved July 25, 2022.

- ^ "The Capitol Records Building: The Story of an L.A. Icon – Discover Los Angeles". Archived from the original on August 15, 2022. Retrieved July 25, 2022.

- ^ "Cathedral of our lady of the angels – Los Angeles, CA". olacathedral.org. Archived from the original on July 25, 2022. Retrieved July 25, 2022.

- ^ "Angels Flight Railway: Los Angeles Landmark since 1901". angels flight.org. Archived from the original on July 21, 2022. Retrieved July 25, 2022.

- ^ Gilchrist, Todd (May 18, 2022). "Hollywood's iconic TCL Chinese Theatre Celebrates 95 Years of Premieres and Stars". Variety. Archived from the original on July 25, 2022. Retrieved July 25, 2022.

- ^ "The Dolby Theatre". dolby.com. Archived from the original on July 25, 2022. Retrieved July 25, 2022.

- ^ "Griffith Observatory: A Symbol of Los Angeles, A Leader in Public Observing". Griffith Observatory. Archived from the original on May 22, 2022. Retrieved July 25, 2022.

- ^ "Getty Center homepage". getty.edu. Archived from the original on July 26, 2022. Retrieved July 26, 2022.