성간물체

Interstellar object

성간물체는 별에 중력적으로 묶여 있지 않은 성간 공간에 있는 천문학적인 물체(예를 들어 소행성, 혜성, 별똥별 등)입니다.이 용어는 성간 궤도에 있지만 특정 소행성과 혜성(외계[1][2] 혜성 포함)과 같이 별에 일시적으로 가까이 지나가는 물체에도 적용될 수 있습니다.후자의 경우, 그 물체는 성간 인터로퍼(interloper)라고 불릴 수 있습니다.[3]

최초로 발견된 성간 물체는 원래의 항성계(예: OTS 44 또는 Cha 110913-773444)에서 분출된 행성인 불량 행성이었지만, 별처럼 성간 공간에서 형성된 갈색 이하의 왜성, 행성 질량의 물체와 구별하기는 어렵습니다.

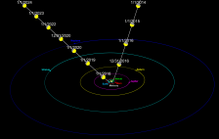

태양계를 여행하며 발견된 최초의 성간 물체는 2017년 1I/ ʻ 오우무아무아였습니다.두 번째는 2019년의 2I/보리소프였습니다.이 둘은 모두 상당한 쌍곡선의 초과 속도를 가지고 있는데, 이는 이들이 태양계에서 기원한 것이 아님을 보여줍니다.ʻ 오우무아무아의 발견은 마누스 섬 불덩이로도 알려진 CNEOS 2014-01-08을 지구에 영향을 미친 성간 물체로 인식하는 데 영감을 주었습니다.이는 2022년 미 우주사령부가 태양과 상대적인 물체의 속도를 바탕으로 확인한 것입니다.[4][5][6][7][8][9][10]2023년 5월, 천문학자들은 수년에 걸쳐 근지구 궤도(NEO)에서 다른 성간물체의 포획 가능성을 보고했습니다.[11][12]

명명법

IAU는 태양계에서 성간물체를 처음 발견하면서 혜성 번호 체계와 유사한 성간물체 I 번호에 대한 일련의 새로운 소체 명칭을 제안했습니다.마이너 플래닛 센터에서 번호를 지정할 겁니다성간 물체에 대한 임시 지정은 해당되는 경우 C/ 또는 A/ 접두사(혜성 또는 소행성)를 사용하여 처리됩니다.[13]

개요

| 물건 | 속도 |

|---|---|

| C/2012 S1 (ISON) (weakly 쌍곡선 오르트 구름 혜성) | 0.2 km/s 0.04 au/yr[14] |

| 보이저 1호 (비교용) | 16.9 km/s 3.57 au/yr[15] |

| 1I/2017U1(ʻ 오우무아무아) | 26.33 km/s 5.55 au/yr[16] |

| 2I/보리소프 | 32.1 km/s 6.77 au/yr[17] |

| 2014년 1월 8일 결투 (동료 검토 중) | 43.8 km/s 9.24 au/yr[18] |

천문학자들은 ʻ 오우무아무아와 같은 외계 기원의 여러 성간 물체들이 매년 지구 궤도 안을 통과하고, 하루에 만 개가 해왕성 궤도 안을 통과한다고 추정합니다.

성간 혜성은 때때로 내부 태양계를[1] 통과하여 임의의 속도로 접근하는데, 주로 헤라클레스 별자리 방향에서 주로 접근하는데, 이는 태양계가 태양 정점이라고 불리는 방향으로 움직이기 때문입니다.[21]오우무아무아'가 발견되기 전까지, 태양의 탈출 속도보다[22] 더 빠른 속도를 가진 혜성이 관측되지 않았다는 사실은 성간 공간에서 그들의 밀도에 상한을 두는데 사용되었습니다.Torbett의 논문은 밀도가 세제곱 파섹 당 1013 (10조)개의 혜성을 넘지 않는다고 지적했습니다.[23]LINEAR의 데이터에 대한 다른 분석에서는 상한을 4.5×10−4/AU3 또는 입방 파섹당 1012 (1조) 혜성으로 설정했습니다.[2]데이비드 C의 더 최근 추정치입니다. 주잇과 동료들은 '오우무아무아'를 발견한 후, "해왕성 궤도 내에 있는 비슷한 ~100 m 크기의 성간 물체의 정상적인 개체수는 ~1×10이며4, 각각의 거주 기간은 ~10년입니다."라고 예측했습니다.[24]

오르트 구름 형성의 현재 모델들은 오르트 구름에 남아 있는 혜성보다 더 많은 혜성들이 성간 공간으로 방출된다고 예측하고 있으며, 추정치는 3배에서 100배까지 다양합니다.[2]다른 시뮬레이션에 따르면 혜성의 90~99%가 분출되는 것으로 추정됩니다.[25]다른 항성계에서 형성된 혜성들이 비슷하게 흩어지지 않을 것이라고 믿을 이유는 없습니다.[1]아미르 시라즈와 아비 뢰브는 오르트 구름이 태양의 탄생 성단에 있는 다른 별들에서 분출된 미행성들로부터 형성되었을 수 있다는 것을 증명했습니다.[26][27][28]

별 주위를 도는 물체가 제3의 거대한 물체와의 상호작용으로 분출되어 성간물체가 되는 것이 가능합니다.그러한 과정은 1980년대 초 C/1980 E1이 처음에는 태양에 중력적으로 결합되어 목성 근처를 지나 태양계에서 탈출 속도에 도달할 수 있을 정도로 가속되었을 때 시작되었습니다.이것은 궤도를 타원형에서 쌍곡형으로 바꾸었고, 이심률이 1.057로 그 당시에 알려진 가장 이심률이 높은 천체로 만들었습니다.[29]그것은 성간 공간을 향해 가고 있습니다.

현재 관측상의 어려움 때문에 성간 물체는 보통 태양계를 통과할 때에만 발견할 수 있으며, 강한 쌍곡 궤도와 수 km/s 이상의 쌍곡 초과 속도로 구별할 수 있어 중력적으로 태양에 묶여 있지 않음을 증명할 수 있습니다.[2][30]반대로, 중력으로 묶인 물체들은 태양 주위의 타원 궤도를 따라갑니다. (궤도가 포물선에 너무 가까워서 중력으로 묶인 상태가 불분명한 몇몇 물체들이 있습니다.)

성간 혜성은 드물게 태양계를 통과하는 동안 태양 중심 궤도에 포착될 수 있습니다.컴퓨터 시뮬레이션에 따르면 목성은 행성 하나를 포획할 수 있을 정도로 질량이 큰 유일한 행성이며, 이는 6천만 년에 한 번 발생할 것으로 예상됩니다.[23]Machholz 1 혜성과 Hyakutake C/1996 B2 혜성이 그러한 혜성의 가능한 예입니다.그들은 태양계에 있는 혜성들을 위한 전형적인 화학적 구성을 가지고 있습니다.[22][31]

아미르 시라즈와 아비 뢰브는 목성과의 밀접한 접촉으로 궤도 에너지를 잃으면서 태양계에 갇혀 있는 ʻ 오우무아무아 같은 천체를 찾을 것을 제안했습니다.그들은 2017년13 SV와 2018년6 TL과 같은 센타우루스자리 후보들을 전용 임무에 의해 방문될 수 있는 포착된 성간 물체로 확인했습니다.[34]저자들은 베라 C와 같은 미래의 하늘 조사에 대해 지적했습니다. 루빈 천문대, 많은 후보를 찾아야 합니다.

최근의 연구는 소행성 514107 카 ʻ파오카 ʻ라웰라가 목성과의 공동 궤도 운동과 태양 주위의 역행적인 궤도로 증명되었듯이, 약 45억 년 전에 포획된 이전의 성간 물체일 수도 있음을 시사합니다.또한 C/2018 V1 혜성(마흐홀츠-후지카와-이와모토)은 오르트 구름의 기원을 배제할 수는 없지만 외계에서 존재할 확률(72.6%)이 매우 높습니다.[36]하버드 대학의 천문학자들은 물질과 잠재적으로 휴면 상태에 있는 포자들이 광활한 거리에 걸쳐 교환될 수 있다고 제안합니다.[37]태양계 내부를 가로지르는 ʻ 오우무아무아의 발견은 외계 행성계와의 물질적 연결 가능성을 확인시켜줍니다.

태양계의 성간 방문객들은 킬로미터의 큰 물체에서부터 서브마이크론 입자에 이르기까지 모든 범위의 크기를 커버합니다.또한, 성간 먼지와 유성체는 그들의 부모 시스템으로부터 귀중한 정보를 운반합니다.그러나 크기 연속체를 따라 이러한 물체를 탐지하는 것은 분명하지 않습니다(그림 참조).[39]가장 작은 성간 먼지 입자들은 전자기력에 의해 태양계에서 걸러지는 반면, 가장 큰 입자들은 너무 희박해서 현장 우주선 탐지기로부터 좋은 통계를 얻을 수 없습니다.성간 개체군과 행성간 개체군을 구별하는 것은 중간 크기(0.1~1마이크로미터)의 문제가 될 수 있습니다.속도와 방향성이 매우 다양할 수 있습니다.[40]지구 대기권에서 관측되는 성간 유성체를 유성으로 식별하는 것은 매우 어렵고 높은 정확도 측정과 적절한 오류 검사가 필요합니다.[41]그렇지 않으면, 측정 오류는 포물선 한계를 넘는 포물선에 가까운 궤도를 전달하고 종종 성간 기원으로 해석되는 쌍곡 입자의 인위적인 집단을 만들 수 있습니다.[39]2017년(1I/'Oumuamua)과 2019년(2I/Borisov)에 태양계에서 처음으로 소행성이나 혜성과 같은 거대한 성간 방문객들이 발견되었으며, 베라 루빈 천문대와 같은 새로운 망원경으로 더 자주 발견될 것으로 예상됩니다.아미르 시라즈와 아비 뢰브는 베라 C를 예측했습니다. 루빈 천문대는 국부적인 휴식 기준과 관련하여 태양의 운동에 의한 성간 물체의 분포의 이방성을 감지하고 그들의 부모 항성으로부터 성간 물체의 특징적인 분출 속도를 확인할 수 있을 것입니다.[42][43][44]

2023년 5월, 천문학자들은 수년에 걸쳐 근지구 궤도(NEO)에서 다른 성간물체의 포획 가능성을 보고했습니다.[11][12]

2023년 7월, 하버드 천문학자 아비 뢰브(Avi Loeb)는 성간 물질을 발견할 수 있는 가능성을 보고했습니다.[45]

확인된 개체

1I/2017U1(ʻ 오우무아무아)

2017년 10월 19일 팬스타RS 망원경에 의해 겉보기 등급 20으로 희미한 천체가 발견되었습니다.관측 결과, 이 별은 태양 탈출 속도보다 빠른 속도로 태양 주위를 도는 강한 쌍곡 궤도를 따라가고 있으며, 이는 이 별이 태양계에 중력적으로 묶여 있지 않고 성간 물체일 가능성이 크다는 것을 의미합니다.[46]처음에는 혜성으로 추정되어 C/2017 U1으로 명명되었다가, 10월 25일 혜성 활동이 발견되지 않아 A/2017 U1으로 명칭이 변경되었습니다.[47][48]성간의 성질이 확인된 후, 1I/ʻ 오우무아무아(Oumuamua-1)로 이름이 바뀌었는데, 이는 성간을 의미하는 "I", 그리고 오우무아무아(Oumuamua)는 하와이어로 "멀리서 온 전령자가 먼저 도착한다"는 뜻이기 때문입니다.

ʻ 오우무아무아의 혜성 활동이 부족하다는 것은 이 행성이 어떤 항성계에서 왔든 내부 지역에서 기원했다는 것을 암시하며, 우리가 태양계에서 알고 있는 암석형 소행성, 멸종된 혜성, 다모클로이드와 같이 서리선 내의 모든 표면 휘발성을 잃게 됩니다.이것은 단지 제안일 뿐인데, ʻ 오우무아무아는 성간 공간에서 우주 방사선에 노출되는 모든 표면 휘발성을 잃었을 것이고, 그것이 그것의 모계로부터 추방된 후 두꺼운 지각 층을 형성했을 것이기 때문입니다.

ʻ오우무아무아의 이심률은 1.199로 2019년 8월 혜성 2I/보리소프가 발견되기 전까지 태양계 천체 중 가장 높은 이심률을 기록했습니다.

2018년 9월, 천문학자들은 ʻ 오우무아무아가 성간 여행을 시작했을 수도 있는 몇 가지 가능성이 있는 항성계를 설명했습니다.

2I/보리소프

2019년 8월 30일 크림 공화국 나우치니의 마르고에서 게나디 보리소프가 맞춤 제작한 0.65m 망원경을 이용하여 발견했습니다.[52]2019년 9월 13일, 그란 망원경 카나리아스는 2I/보리소프의 저해상도 가시 스펙트럼을 얻었는데, 이는 이 천체가 일반적인 오르트 구름 혜성과 크게 다르지 않은 표면 구성을 가지고 있음을 보여주었습니다.[53][54][55]작은 천체 명명법을 위한 IAU 워킹 그룹은 보리소프라는 이름을 유지했고, 혜성에 2I/Borisov라는 성간 명칭을 부여했습니다.[56]2020년 3월 12일, 천문학자들은 보리소프의 "핵 조각화가 진행 중"이라는 관측 증거를 보고했습니다.[57]

후보자

2007년 아파나시예프 등은 2006년 7월 28일 러시아 과학 아카데미의 특수 천체물리 관측소 상공에서 수 센티미터 크기의 은하간 운석이 대기권에 충돌하는 것으로 추정된다고 보고했습니다.[58]

2018년 11월 하버드 대학교의 천문학자 아미르 시라즈와 아비 [59]뢰브는 계산된 궤도 특성에 근거하여 태양계에 수백 개의 '오우무아무아 크기의 성간 천체'가 있을 것이라고 보고하였고, 201713 SV와 20186 TL과 같은 여러 센타우루스상 후보를 제시하였습니다.이것들은 모두 태양 주위를 돌고 있지만, 먼 과거에 포착되었을 수도 있습니다.

아미르 시라즈와 아비 뢰브는 항성의 가려짐 현상, 달 또는 지구 대기와의 충돌로 인한 광학적 신호, 중성자별과의 충돌로 인한 전파 플레어 등 성간 물체의 발견율을 높이기 위한 방법을 제안했습니다.[60][61][62][63]

2014년 성간 유성

2014년 1월 8일 지구 대기권에서 타버린 질량 0.46톤, [64][65][66]폭 0.45m의 유성인 CNEOS 2014-01-08 (인터스텔라 유성 1; IM1로도 알려짐).[7][10]2019년 미리 인쇄된 자료에 따르면 이 유성은 성간에서 기원한 것으로 보입니다.[67][68][5][6][9]태양 중심 속도는 60 km/s (37 mi/s), 점근 속도는 42.1 ± 5.5 km/s (26.2 ± 3.4 mi/s)였으며, 파푸아 뉴기니 근처 UTC 17:05:34에 고도 18.7 km (61,000 ft)에서 폭발했습니다.[7]2022년 4월 데이터를 기밀 해제한 후,[69] 미국 우주 사령부는 행성 방어 센서로부터 수집한 정보를 바탕으로 잠재적인 성간 유성의 속도를 확인했습니다.[8][4]2023년 갈릴레오 프로젝트는 분명히 특이한[70][71][72] 운석의 작은 조각들을 회수하기 위한 탐험을 마쳤습니다.[73][72]뉴욕 타임즈의 한 보도에 따르면, 그들의 발견에 대한 주장은 동료들에 의해 의심받고 있습니다.[74]추가 관련 연구는 2023년 9월 1일에 보고되었습니다.[75][76]

다른 천문학자들은 사용된 유성체 목록이 들어오는 속도에 대한 불확실성을 보고하지 않기 때문에 성간 기원을 의심합니다.[77](특히 더 작은 유성체의 경우) 단일 데이터 점의 유효성은 여전히 의문입니다.2022년 11월, CNEOS 2014-01-08의 변칙적 특성(고강도 및 강한 쌍곡 궤적 포함)이 실제 매개변수가 아닌 측정 오류로 더 잘 설명된다고 주장하는 논문이 발표되었습니다.유성체 파편을 성공적으로 회수할 가능성은 매우 낮습니다.[78]일반적인 미세 운석은 서로 구별할 수 없을 것입니다.

2017년 성간 유성

2017년 3월 9일 지구 대기권에서 불에 탄 약 6.3톤의 질량을 가진 유성인 [65][66]CNEOS 2017-03-09 (일명 인터스텔라 유성 2; IM2).IM1과 마찬가지로 높은 기계적 강도를 가지고 있습니다.[79][65]

2022년 9월, 천문학자 아미르 시라즈와 아비 뢰브는 2017년 지구에 영향을 미쳤고, 부분적으로 이 유성의 높은 물질적 강도에 근거하여 성간 가능성이 있는 것으로 간주되는 후보 성간 유성 CNEOS 2017-03-09 (일명 성간 유성 2; IM2)의 발견을 보고했습니다.[65][66]

가상 미션

현재의 우주 기술로, 가능하지는 않지만 빠른 속도 때문에 근접 방문과 궤도 임무는 어렵습니다.[80][81]

성간 연구 이니셔티브(i4is)는 2017년 프로젝트 라이라에서 ʻ 오우무아무아로의 임무 수행 가능성을 평가하기 위해 시작되었습니다.5년에서 25년의 기간 내에 우주선을 ʻ 오우무아무아로 보낼 수 있는 몇 가지 방안이 제시되었습니다.한 가지 방법은 먼저 목성 근접 비행을 사용한 후 3 태양 반경(2.1×106 km; 1.3×106 mi)에서 근접 태양 근접 비행을 사용하는 것입니다.[85]요격 궤적으로의 직접적인 충동 전달을 가정하여, 발사일과 관련하여 다양한 임무 기간과 그들의 속도 요구 사항을 조사했습니다.

2029년에 발사될 예정인 ESA와 JAXA의 혜성 요격 우주선은 적합한 장기간의 혜성이 요격되어 연구를 위해 비행하기를 기다리는 태양-지구 L2 지점에 배치될 예정입니다.[86]만약 3년의 대기 기간 동안 적합한 혜성이 발견되지 않는다면, 우주선은 도달할 수 있다면, 성간 물체를 짧은 시간 내에 요격하는 임무를 수행할 수 있습니다.[87]

참고 항목

- 글로벌 대재앙 위험 – 잠재적으로 유해할 수 있는 전 세계적 이벤트

- 쌍곡선 소행성 – 태양 주위를 공전하지 않는 천체

- 태양계를 떠나는 인공물 목록

- 쌍곡 혜성 목록 – 태양을 공전하지 않을 수도 있는 혜성

- 태양계의 천체 목록

참고문헌

- ^ a b c Valtonen, Mauri J.; Zheng, Jia-Qing; Mikkola, Seppo (March 1992). "Origin of oort cloud comets in the interstellar space". Celestial Mechanics and Dynamical Astronomy. 54 (1–3): 37–48. Bibcode:1992CeMDA..54...37V. doi:10.1007/BF00049542. S2CID 189826529.

- ^ a b c d Francis, Paul J. (2005-12-20). "The Demographics of Long-Period Comets". The Astrophysical Journal. 635 (2): 1348–1361. arXiv:astro-ph/0509074. Bibcode:2005ApJ...635.1348F. doi:10.1086/497684. S2CID 12767774.

- ^ Veras, Dimitri (13 April 2020). "Creating the first interstellar interloper". Nature Astronomy. 4 (9): 835–836. Bibcode:2020NatAs...4..835V. doi:10.1038/s41550-020-1064-9. ISSN 2397-3366.

- ^ a b United States Space Command (6 April 2022). "I had the pleasure of signing a memo with @ussfspoc's Chief Scientist, Dr. Mozer, to confirm that a previously-detected interstellar object was indeed an interstellar object, a confirmation that assisted the broader astronomical community". Twitter. Retrieved 12 April 2022.

- ^ a b Ferreira, Becky (7 April 2022). "Secret Government Info Confirms First Known Interstellar Object on Earth, Scientists Say – A small meteor that hit Earth in 2014 was from another star system, and may have left interstellar debris on the seafloor". Vice News. Retrieved 9 April 2022.

- ^ a b Wenz, John (11 April 2022). ""It Opens A New Frontier Where You're Using The Earth As A Fishing Net For These Objects." – Harvard Astronomer Believes An Interstellar Meteor (or Craft) Hit Earth In 2014". Inverse. Retrieved 11 April 2022.

- ^ a b c Siraj, Amir; Loeb, Abraham (4 June 2019). "Discovery of a Meteor of Interstellar Origin". arXiv:1904.07224 [astro-ph.EP].

- ^ a b Handal, Josh; Fox, Karen; Talbert, Tricia (8 April 2022). "U.S. Space Force Releases Decades of Bolide Data to NASA for Planetary Defense Studies". NASA. Retrieved 11 April 2022.

- ^ a b Siraj, Amir (12 April 2022). "Spy Satellites Confirmed Our Discovery of the First Meteor from beyond the Solar System - A high-speed fireball that struck Earth in 2014 looked to be interstellar in origin, but verifying this extraordinary claim required extraordinary cooperation from secretive defense programs". Scientific American. Retrieved 14 April 2022.

- ^ a b Roulette, Joey (15 April 2022). "Military Memo Deepens Possible Interstellar Meteor Mystery – The U.S. Space Command seemed to confirm a claim that a meteor from outside the solar system had entered Earth's atmosphere, but other scientists and NASA are still not convinced. (+ Comment)". The New York Times. Retrieved 15 April 2022.

- ^ a b Gough, Evan (18 May 2023). "A Few Interstellar Objects Have Probably Been Captured". Universe Today. Retrieved 19 May 2023.

- ^ a b Mukherjee, Diptajyoti; Siraj, Amir; Trac, Hy; Loeb, Abraham (2023). "Close Encounters of the Interstellar Kind: Exploring the Capture of Interstellar Objects in Near Earth Orbit". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. arXiv:2305.08915. doi:10.1093/mnras/stad2317.

- ^ "MPEC 2017-V17 : NEW DESIGNATION SCHEME FOR INTERSTELLAR OBJECTS". Minor Planet Center. 6 November 2017.

- ^ C/2012 S1(ISON)은 1600 중심 반장축 -145127이며 50000 au에서 0.2 km/s의 인바운드 v_infinite를 가질 것입니다.

v=42.1219 √1/50000 - 0.5/-145127 - ^ 보이저에 관한 빠른 사실들

- ^ Gray, Bill (26 October 2017). "Pseudo-MPEC for A/2017 U1 (FAQ File)". Project Pluto. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- ^ Gray, Bill. "FAQ for C/2019 Q4 (Borisov)". Project Pluto. Retrieved 2019-09-24.

- ^ Siraj, Amir; Loeb, Abraham (2019). "Discovery of a Meteor of Interstellar Origin". arXiv:1904.07224 [astro-ph.EP].

- ^ "Interstellar Asteroid FAQs". NASA. 20 November 2017. Retrieved 21 November 2017.

- ^ Fraser, Wesley (11 February 2018). "The Sky at Night: The Mystery of ʻOumuamua" (Interview). Interviewed by Chris Lintott. BBC.

- ^ Struve, Otto; Lynds, Beverly; Pillans, Helen (1959). Elementary Astronomy. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 150.

- ^ a b MacRobert, Alan (2008-12-02). "A Very Oddball Comet". Sky & Telescope. Retrieved 2010-03-26.

- ^ a b Torbett, M. V. (July 1986). "Capture of 20 km/s approach velocity interstellar comets by three-body interactions in the planetary system". Astronomical Journal. 92: 171–175. Bibcode:1986AJ.....92..171T. doi:10.1086/114148.

- ^ Jewitt, David; Luu, Jane; Rajagopal, Jayadev; Kotulla, Ralf; Ridgway, Susan; Liu, Wilson; Augusteijn, Thomas (2017). "Interstellar Interloper 1I/2017 U1: Observations from the NOT and WIYN Telescopes". The Astrophysical Journal. 850 (2): L36. arXiv:1711.05687. Bibcode:2017ApJ...850L..36J. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/aa9b2f. S2CID 32684355.

- ^ Choi, Charles Q. (2007-12-24). "The Enduring Mysteries of Comets". Space.com. Retrieved 2008-12-30.

- ^ Siraj, Amir; Loeb, Abraham (2020-08-18). "The Case for an Early Solar Binary Companion". The Astrophysical Journal. 899 (2): L24. arXiv:2007.10339. Bibcode:2020ApJ...899L..24S. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/abac66. ISSN 2041-8213. S2CID 220665422.

- ^ Carter, Jamie. "Was Our Sun A Twin? If So Then 'Planet 9' Could Be One Of Many Hidden Planets In Our Solar System". Forbes. Retrieved 2020-11-14.

- ^ "Did the Sun have an early binary companion?". Cosmos Magazine. 2020-08-20. Archived from the original on 2020-11-16. Retrieved 2020-11-14.

- ^ "JPL Small-Body Database Browser: C/1980 E1 (Bowell)" (1986-12-02 last obs). Retrieved 2010-01-08.

- ^ de la Fuente Marcos, Carlos; de la Fuente Marcos, Raúl; Aarseth, Sverre J. (6 February 2018). "Where the Solar system meets the solar neighbourhood: patterns in the distribution of radiants of observed hyperbolic minor bodies". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society Letters. 476 (1): L1–L5. arXiv:1802.00778. Bibcode:2018MNRAS.476L...1D. doi:10.1093/mnrasl/sly019. S2CID 119405023.

- ^ Mumma, M. J.; Disanti, M. A.; Russo, N. D.; Fomenkova, M.; Magee-Sauer, K.; Kaminski, C. D.; Xie, D. X. (1996). "Detection of Abundant Ethane and Methane, Along with Carbon Monoxide and Water, in Comet C/1996 B2 Hyakutake: Evidence for Interstellar Origin". Science. 272 (5266): 1310–1314. Bibcode:1996Sci...272.1310M. doi:10.1126/science.272.5266.1310. PMID 8650540. S2CID 27362518.

- ^ Siraj, Amir; Loeb, Abraham (2019). "Identifying Interstellar Objects Trapped in the Solar System through Their Orbital Paramteters". The Astrophysical Journal. 872 (1): L10. arXiv:1811.09632. Bibcode:2019ApJ...872L..10S. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/ab042a. S2CID 119198820.

- ^ Koren, Marina (23 January 2019). "When a Harvard Professor Talks About Aliens – News about extraterrestrial life sounds better coming from an expert at a high-prestige institution". The Atlantic. Retrieved 23 January 2019.

- ^ Siraj, Amir; Loeb, Abraham (February 2019). "Identifying Interstellar Objects Trapped in the Solar System through Their Orbital Parameters". The Astrophysical Journal. 872 (1): L10. arXiv:1811.09632. Bibcode:2019ApJ...872L..10S. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/ab042a. S2CID 119198820.

- ^ Clery, Daniel (2018). "This asteroid came from another solar system—and it's here to stay". Science. doi:10.1126/science.aau2420.

- ^ de la Fuente Marcos, Carlos; de la Fuente Marcos, Raúl (11 October 2019). "Comet C/2018 V1 (Machholz-Fujikawa-Iwamoto): dislodged from the Oort Cloud or coming from interstellar space?". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 489 (1): 951–961. arXiv:1908.02666. Bibcode:2019MNRAS.489..951D. doi:10.1093/mnras/stz2229. S2CID 199472877.

- ^ Reuell, Peter (8 July 2019). "Harvard study suggests asteroids might play key role in spreading life". Harvard Gazette. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- ^ Hajdukova, Maria; Sterken, Veerle; Wiegert, Paul; Kornoš, Leonard (2020-11-01). "The challenge of identifying interstellar meteors". Planetary and Space Science. 192: 105060. Bibcode:2020P&SS..19205060H. doi:10.1016/j.pss.2020.105060. ISSN 0032-0633.

- ^ a b Hajdukova, M.; Sterken, V.; Wiegert, P.; Kornoš, L. (2020-11-01). "The challenge of identifying interstellar meteors". Planetary and Space Science. 192: 105060. Bibcode:2020P&SS..19205060H. doi:10.1016/j.pss.2020.105060. ISSN 0032-0633.

- ^ Sterken, V. J.; Altobelli, N.; Kempf, S.; Schwehm, G.; Srama, R.; Grün, E. (2012-02-01). "The flow of interstellar dust into the solar system". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 538: A102. Bibcode:2012A&A...538A.102S. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201117119. ISSN 0004-6361.

- ^ Hajduková, Mária; Kornoš, Leonard (2020-10-01). "The influence of meteor measurement errors on the heliocentric orbits of meteoroids". Planetary and Space Science. 190: 104965. Bibcode:2020P&SS..19004965H. doi:10.1016/j.pss.2020.104965. ISSN 0032-0633. S2CID 224927095.

- ^ Siraj, Amir; Loeb, Abraham (2020-10-29). "Observable Signatures of the Ejection Speed of Interstellar Objects from Their Birth Systems". The Astrophysical Journal. 903 (1): L20. arXiv:2010.02214. Bibcode:2020ApJ...903L..20S. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/abc170. ISSN 2041-8213. S2CID 222141714.

- ^ Williams, Matt (2020-11-07). "Vera Rubin Should be Able to Detect a Couple of Interstellar Objects a Month". Universe Today. Retrieved 2020-11-14.

- ^ Clery, Daniel (2021-07-26). "Project launched to look for extraterrestrial visitors to our Solar System". www.science.org. Retrieved 2021-10-22.

- ^ Loeb, Avi (5 July 2023). "I'm a Harvard Astronomer. I Think We Found Interstellar Material". Newsweek. Archived from the original on 7 July 2023. Retrieved 7 July 2023.

- ^ "MPEC 2017-U181: COMET C/2017 U1 (PANSTARRS)". Minor Planet Center. Retrieved 25 October 2017.

- ^ Meech, K. (25 October 2017). "Minor Planet Electronic Circular MPEC 2017-U183: A/2017 U1". Minor Planet Center.

- ^ "We May Just Have Found An Object That Originated From Outside Our Solar System". IFLScience. October 26, 2017.

- ^ "Aloha, 'Oumuamua! Scientists confirm that interstellar asteroid is a cosmic oddball". GeekWire. 20 November 2017.

- ^ Feng, Fabo; Jones, Hugh R. A. (2018). "Plausible home stars of the interstellar object 'Oumuamua found in Gaia DR2". The Astronomical Journal. 156 (5): 205. arXiv:1809.09009. Bibcode:2018AJ....156..205B. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/aae3eb. S2CID 119051284.

- ^ '오우무아무아는 우리 태양계에서 온 것이 아닙니다.이제 우리는 그것이 어느 별에서 왔는지 알 수 있습니다.

- ^ King, Bob (11 September 2019). "Is Another Interstellar Visitor Headed Our Way?". Sky & Telescope. Retrieved 12 September 2019.

- ^ "The Gran Telescopio Canarias (GTC) obtains the visible spectrum of C/2019 Q4 (Borisov), the first confirmed interstellar comet". Instituto Astrofisico de Canarias. 14 September 2019. Retrieved 2019-09-14.

- ^ de León, Julia; Licandro, Javier; Serra-Ricart, Miquel; Cabrera-Lavers, Antonio; Font Serra, Joan; Scarpa, Riccardo; de la Fuente Marcos, Carlos; de la Fuente Marcos, Raúl (19 September 2019). "Interstellar Visitors: A Physical Characterization of Comet C/2019 Q4 (Borisov) with OSIRIS at the 10.4 m GTC". Research Notes of the American Astronomical Society. 3 (9): 131. Bibcode:2019RNAAS...3..131D. doi:10.3847/2515-5172/ab449c. S2CID 204193392.

- ^ de León, J.; Licandro, J.; de la Fuente Marcos, C.; de la Fuente Marcos, R.; Lara, L. M.; Moreno, F.; Pinilla-Alonso, N.; Serra-Ricart, M.; De Prá, M.; Tozzi, G. P.; Souza-Feliciano, A. C.; Popescu, M.; Scarpa, R.; Font Serra, J.; Geier, S.; Lorenzi, V.; Harutyunyan, A.; Cabrera-Lavers, A. (30 April 2020). "Visible and near-infrared observations of interstellar comet 2I/Borisov with the 10.4-m GTC and the 3.6-m TNG telescopes". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 495 (2): 2053–2062. arXiv:2005.00786v1. Bibcode:2020MNRAS.495.2053D. doi:10.1093/mnras/staa1190. S2CID 218486809.

- ^ "MPEC 2019-S72 : 2I/Borisov=C/2019 Q4 (Borisov)". Minor Planet Center. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- ^ Drahus, Michal; et al. (12 March 2020). "ATel#1349: Multiple Outbursts of Interstellar Comet 2I/Borisov". The Astronomer's Telegram. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- ^ Afanasiev, V. L.; Kalenichenko, V. V.; Karachentsev, I. D. (1 December 2007). "Detection of an intergalactic meteor particle with the 6-m telescope". Astrophysical Bulletin. 62 (4): 301–310. arXiv:0712.1571. Bibcode:2007AstBu..62..301A. doi:10.1134/S1990341307040013. ISSN 1990-3421. S2CID 16340731.

- ^ Siraj, Amir; Loeb, Abraham (2019). "Identifying Interstellar Objects Trapped in the Solar System through Their Orbital Parameters". The Astrophysical Journal. 872 (1): L10. arXiv:1811.09632. Bibcode:2019ApJ...872L..10S. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/ab042a. S2CID 119198820.

- ^ Siraj, Amir; Loeb, Abraham (2020-02-26). "Detecting Interstellar Objects through Stellar Occultations". The Astrophysical Journal. 891 (1): L3. arXiv:2001.02681. Bibcode:2020ApJ...891L...3S. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/ab74d9. ISSN 2041-8213. S2CID 210116475.

- ^ Siraj, Amir; Loeb, Abraham (2020-08-01). "A real-time search for interstellar impacts on the moon". Acta Astronautica. 173: 53–55. arXiv:1908.08543. Bibcode:2020AcAau.173...53S. doi:10.1016/j.actaastro.2020.04.006. ISSN 0094-5765. S2CID 201645069.

- ^ Siraj, Amir; Loeb, Abraham (2019-09-19). "Radio Flares from Collisions of Neutron Stars with Interstellar Asteroids". Research Notes of the AAS. 3 (9): 130. arXiv:1908.11440. Bibcode:2019RNAAS...3..130S. doi:10.3847/2515-5172/ab43de. ISSN 2515-5172. S2CID 201698501.

- ^ August 2019, Mike Wall 30 (30 August 2019). "A Telescope Orbiting the Moon Could Spy 1 Interstellar Visitor Per Year". Space.com. Retrieved 2020-11-14.

- ^ Pultarova, Tereza (3 November 2022). "Confirmed! A 2014 meteor is Earth's 1st known interstellar visitor - Interstellar space rocks might be falling to Earth every 10 years". Space.com. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- ^ a b c d Siraj, Amir; Loeb, Avi (20 September 2022). "Interstellar Meteors are Outliers in Material Strength". The Astrophysical Journal. 941 (2): L28. arXiv:2209.09905v1. Bibcode:2022ApJ...941L..28S. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/aca8a0. S2CID 252407502.

- ^ a b c Loeb, Avi (23 September 2022). "The discovery of a second interstellar meteor". TheDebrief.org. Retrieved 24 September 2022.

- ^ Billings, Lee (23 April 2019). "Did a Meteor from Another Star Strike Earth in 2014? – Questionable data cloud the potential discovery of the first known interstellar fireball". Scientific American. Retrieved 12 April 2022.

- ^ Choi, Charles Q. (16 April 2019). "The First Known Interstellar Meteor May Have Hit Earth in 2014 – The 3-foot-wide rock rock visited us three years before 'Oumuamua". Space.com. Retrieved 12 April 2022.

- ^ Specktor, Brandon (11 April 2022). "An interstellar object exploded over Earth in 2014, declassified government data reveal – Classified data prevented scientists from verifying their discovery for 3 years". Live Science. Retrieved 12 April 2022.

- ^ Loeb, Avi (18 April 2022). "The First Interstellar Meteor Had a Larger Material Strength Than Iron Meteorites". Medium. Retrieved 21 August 2022.

- ^ Fuschetti, Ray; Johnson, Malcolm; Strader, Aaron. "Harvard Professor Believes Alien Tech Could Have Crashed Into Pacific Ocean — And He Wants to Find It". NBC Boston. Retrieved 2 September 2022.

- ^ a b Siraj, Amir; Loeb, Abraham; Gallaudet, Tim (5 August 2022). "An Ocean Expedition by the Galileo Project to Retrieve Fragments of the First Large Interstellar Meteor CNEOS 2014-01-08". arXiv:2208.00092 [astro-ph.EP].

- ^ Carter, Jamie (9 August 2022). "Astronomers plan to fish an interstellar meteorite out of the ocean using a massive magnet". livescience.com. Retrieved 21 August 2022.

- ^ Miller, Katrina (24 July 2023). "Scientist's Deep Dive for Alien Life Leaves His Peers Dubious - Avi Loeb, a Harvard astrophysicist, says that material recovered from the seafloor could be from an extraterrestrial spacecraft. His peers are skeptical. + comment". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 25 July 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ^ McRae, Mike (1 September 2023). "Material Found in Ocean Is Not From This Solar System, Study Claims". Archived from the original on 1 September 2023. Retrieved 1 September 2023.

- ^ Loeb, Avi; et al. (29 August 2023). "Discovery of Spherules of Likely Extrasolar Composition in the Pacific Ocean Site of the CNEOS 2014-01-08 (IM1) Bolide". arXiv. arXiv:2308.15623. Archived from the original on 1 September 2023. Retrieved 1 September 2023.

- ^ Billings, Lee (2019-04-23). "Did a Meteor from Another Star Strike Earth in 2014". Scientific American. Retrieved 2019-04-23.

- ^ Vaubaillon, J. (2022), "Hyperbolic meteors: is CNEOS 2014-01-08 interstellar?", WGN, 50 (5): 140, arXiv:2211.02305, Bibcode:2022JIMO...50..140V

- ^ "Alien-Hunting Astronomer Says There May Be a Second Interstellar Object on Earth in New Study". Vice. Retrieved 3 November 2022.

- ^ Seligman, Darryl; Laughlin, Gregory (12 April 2018). "The Feasibility and Benefits of in situ Exploration of ʻOumuamua-like Objects". The Astronomical Journal. 155 (5): 217. arXiv:1803.07022. Bibcode:2018AJ....155..217S. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/aabd37. S2CID 73656586.

- ^ Ferreira, Becky (8 November 2022). "We Need to Intercept Our Next Interstellar Visitor to See If It's Artificial, Astronomers Say in New Study - A new study games out a mission to intercept an interstellar object in space and get a close-up look to see just what its made of". Vice. Retrieved 8 November 2022.

- ^ "Project Lyra – A Mission to ʻOumuamua". Initiative for Interstellar Studies.

- ^ Hein, Andreas M.; Perakis, Nikolaos; Eubanks, T. Marshall; Hibberd, Adam; Crowl, Adam; Hayward, Kieran; Kennedy, Robert G., III; Osborne, Richard (7 January 2019). "Project Lyra: Sending a spacecraft to 1I/'Oumuamua (former A/2017 U1), the interstellar asteroid". Acta Astronautica. 161: 552–561. arXiv:1711.03155. Bibcode:2017arXiv171103155H. doi:10.1016/j.actaastro.2018.12.042. S2CID 119474144.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 유지 : 여러 이름 : 저자 목록 (링크) - ^ Hibberd, Adam; Hein, Andreas M.; Eubanks, T. Marshall (2020). "Project Lyra: Catching 1I/'Oumuamua – Mission Opportunities After 2024". Acta Astronautica. 170: 136–144. arXiv:1902.04935. Bibcode:2020AcAau.170..136H. doi:10.1016/j.actaastro.2020.01.018. S2CID 119078436.

- ^ Hein, A.M.; Perakis, N.; Long, K.F.; Crowl, A.; Eubanks, M.; Kennedy, R.G., III; Osborne, R. (2017). "Project Lyra: Sending a Spacecraft to 1I/ʻOumuamua (former A/2017 U1), the Interstellar Asteroid". arXiv:1711.03155 [physics.space-ph].

{{cite arXiv}}: CS1 유지 : 여러 이름 : 저자 목록 (링크) - ^ "Ariel moves from blueprint to reality". ESA. 12 November 2020. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- ^ O'Callaghan, Jonathan (24 June 2019). "European Comet Interceptor Could Visit an Interstellar Object". Scientific American.

외부 링크

- Engelhardt, Toni; Jedicke, Robert; Vereš, Peter; Fitzsimmons, Alan; Denneau, Larry; Beshore, Ed; Meinke, Bonnie (2017). "An Observational Upper Limit on the Interstellar Number Density of Asteroids and Comets". The Astronomical Journal. 153 (3): 133. arXiv:1702.02237. Bibcode:2017AJ....153..133E. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/aa5c8a. S2CID 54893830.