이성 및 성소수자

Intersex and LGBT| 이성간의 토픽 |

|---|

| 시리즈의 일부 |

| LGBT 토픽 |

|---|

| |

간성인들은 "남성이나 여성의 [1][2]신체에 대한 일반적인 정의에 맞지 않는" 성적인 특징들을 가지고 태어난다, 생식선, 염색체 패턴 등)을 가지고 태어난다.그들은 비성간 인구보다 레즈비언, 게이, 양성애자 또는 트랜스젠더(LGBT)로 식별될 가능성이 상당히 높으며, 추정 52%가 비성간자로 식별되고 8.5%에서 20%가 성불감증을 경험한다.비록 많은 이성애자들이 이성애자이고 [3][4]시스젠더이지만, 이러한 중복과 "지배적인 사회적 성과 성 규범에서 발생하는 해악의 공유 경험"은 종종 LGBTI로 약자가 확장되면서 간성애자들이 성소수자 [5][a]우산 아래에 포함되게 되었다.하지만, 일부 이성간 활동가들과 단체들은 이러한 포함이 비자발적인 의료 개입과 같은 이성간 특정 이슈에 주의를 산만하게 한다고 비판해왔다.

이성애와 동성애

간성은 동성애나 동성간의 매력과 대조될 수 있다.최근 호주의 비정형 성 특성을 가진 사람들을 대상으로 한 연구에서 응답자의 52%가 [8][3]비-간성애자라는 사실이 밝혀지면서, 많은 연구들이 [6][7]간성애자들에게서 더 높은 동성 매력 비율을 보여주고 있다.

동성애를 [6][7]예방하는 방법을 조사하기 위해 이성간 피험자에 대한 임상 연구가 사용되어 왔다.1990년, 하이노 마이어-벨버그는 "성적 지향의 태아 호르몬 이론"에 대해 썼다.저자는 선천성 부신 과형성 여성에게서 동성연애율이 높아지고 안드로겐 불감증 여성에게서 남성연애율이 지속적으로 높아지는 연구(유전자 남성)에 대해 논의했다.마이어-벨부르크는 또한 부분 안드로겐 불감증 증후군, 5α-환원효소 결핍증 및 17β-히드록시스테로이드 탈수소효소 III 결핍증을 가진 개인의 성적 매력에 대해 논의했으며, 이러한 [6]조건을 가진 개인의 여성에 대한 성적 매력이 "안드로겐에 대한 태아기 노출과 사용에 의해 촉진되었다"고 밝혔다.그는 다음과 같이 결론지었다.

동성애 발달에 산전 또는 산전 호르몬의 기여가 있다고 단정하는 것은 시기상조이다. 다만, 아마도 간성의 명확한 신체적 징후를 가진 사람을 제외한다.관련된 [6]윤리적 문제와는 상당히 동떨어진 동성애의 발달을 방지하기 위해 태아의 염색체나 성호르몬, 태아기 치료의 평가를 정당화하기에는 과학적 근거가 불충분하다.

2010년, 사로즈 님칸과 마리아 뉴는 "성별 관련 행동, 즉 청소년기와 성인기의 어린 시절 놀이, 또래 관계, 직업과 여가 시간 선호, 모성애, 공격성, 성적 성향은 선천성 부신 [9]과형성을 가진 여성들에게서 남성화된다"고 썼다.Dreger, Feder, Tamar-Mattis는 그러한 특성을 막기 위한 의학적 개입을 동성애와 "보급 여성"[10]을 예방하는 수단으로 비유해왔다.

기묘한 몸

모건 홈즈, 카트리나 카카지스, 모건 카펜터와 같은 이성간 활동가들과 학자들은 이성간 [11][12][13]특성을 가진 유아와 아동에 대한 의료 개입에 대한 의학적 합리성의 이질성을 확인했다.홈즈와 카펜터는 때때로 이성간의 몸을 "큐어 바디"[11][14]로 언급하고, 카펜터는 또한 성적 지향이나 성 정체성의 [12]문제로 이성간의 프레임이 부적절하고 "위험한" 결과를 강조합니다.

퀴어 이론이 이성애자들에게 무엇을 해줄 수 있을까?이안 몰랜드는 "기쁨과 [15]수치심의 감각적 상관관계가 특징"이라고 주장하기 위해 퀴어한 "쾌락주의 행동주의"와 무감각한 수술 후 이성 간의 신체 경험을 대비시킨다.

이성 및 트랜스젠더

간성은 또한 성전환자와 대조될 수 있는데, 트랜스젠더는 [16]한 사람의 성 [16][17][18]정체성이 할당된 성별과 일치하지 않는 상태를 묘사한다.어떤 사람들은 이성애자이면서 [19]트랜스젠더이다.2012년 임상 검토 논문에 따르면 성 간 변이가 있는 사람 중 8.5%에서 20%가 성불감증을 [4]경험했다.

비이진성

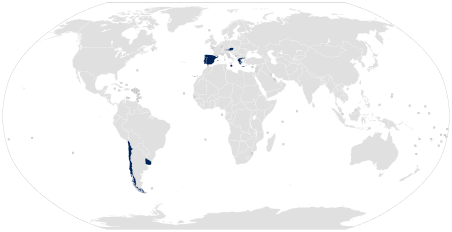

제3의 성별 또는 성별 분류는 여러 [20][21][22][23]국가에서 인정된다.세 번째 'X' 성 분류 국가인 호주의 사회학적 연구에 따르면 비정형 성 특성을 가진 출생자 중 19%가 'X' 또는 '기타' 옵션을 선택한 반면 52%는 여성, 23%는 남성, 6%는 [8][3]확실하지 않은 것으로 나타났다.

어느 성에도 속할 수 없는 영유아도 출생증명서에 신분을 공백으로 남겨두도록 요구하는 독일의 법은 중립적인 선택을 하는 부모들에게 성기 수술을 [24][25][26][27]받는 것을 바람직하지 않다고 생각하는 부모들을 장려할 수 있다는 근거로 성 간 권리 단체들에 의해 비난 받았다.2013년에는 3국제 간성은 포럼 성과 성적 등록 서류의 몰타의 처음", 의식을 가진 여성의 남자를 남성으로도 중간 성 아이들 register[ing]모든 사람들처럼, 그들은 다른 성을 가진 또는 여성을 확인할 자랄 수도 있"과 그 섹스나 그는 ensur[ing]을 옹호하는 declaration,[28][29]에 발언을 했다.nder개인증은 관계자의 요청에 따라 간단한 행정절차를 통해 수정할 수 있다.또한 출생증명서에 성별을 등록하는 것을 중단하는 한편 모두를 위한 비이진 선택권과 자기 신분을 확인하는 것을 지지한다.

알렉스 맥팔레인은 2003년 호주에서 처음으로 성별이 불분명하다는 출생증명서를 발급받았으며,[30][21][31] 호주 여권으로는 처음으로 성별 표시인 'X'가 찍힌 것으로 알려졌다.2016년 9월 26일, 캘리포니아 거주자 사라 켈리 키넌은 미국에서 제이미 슈페 다음으로 법적으로 성별을 '비 바이너리'로 바꾼 두 번째 사람이 되었다.키넌은 슈페의 사례를 탄원서의 영감으로 인용했다.성전환법은 성전환자를 위한 것이라고 생각했기 때문에 이것이 선택이라고는 생각하지 못했다.제3의 성별을 갖기 [32]위해 같은 틀을 사용하기로 했습니다." 키넌은 나중에 성별 간 표식을 가진 출생 증명서를 얻었습니다.이 결정에 대한 언론 보도에서,[33] 오하이오는 2012년에 '허마프로다이트' 섹스 마커를 발행한 것이 분명해졌다.

성 간 학자인 모건 홈즈는 '제3의 성'을 우월하게 통합하는 사회를 생각하는 것은 지나치게 단순하며, "시스템이 다른 것보다 더 억압적인지 덜 억압적인지를 이해하기 위해서는 우리는 그것이 '제3의 [34]성'뿐만 아니라 다양한 구성원을 어떻게 다루는지 이해해야 한다"고 주장한다.

Asia Pacific Forum of National Human Rights Institutes는 이성간 사람들의 법적 인정은 첫째, 남성 또는 여성으로 배정되었을 때 다른 남녀와 동일한 권리에 대한 접근에 관한 것이고, 둘째, 원래의 성별 할당이 적절하지 않을 때 법적 문서에 대한 행정적 수정에 대한 접근에 관한 것이라고 말한다.이것은 집단으로서 제3의 성별이나 성별 분류를 만드는 것에 관한 것이 아니라 자기 결정에 [35]관한 것이다.

LGBT 및 LGBTI

레즈비언, 게이, 양성애자, 트랜스, 퀴어 커뮤니티에 대한 이성간의 관계는 [36]복잡하지만 LGBTI [37][38]커뮤니티를 만들기 위해 LGBT에 간성인을 추가하는 경우가 많다.유엔인권고등판무관실의 2019년 배경 노트에는 간성인은 "대표, 잘못된 표현 및 자원 제공"에 대한 우려를 가진 별개의 집단이지만, "지배적인 성(性)과 성(性)으로 인한 피해 경험을 공유하기 때문에" LGBT 사람들과 "공통 우려"를 공유하는 집단이라고 명시되어 있다.ender 규범"이 논문은 이성간 사람들이 어떻게 인권침해를 겪을 수 있는지, 혹은 그들이 자유롭게 표현하고 정체성을 표현하기 전에"와 "성소수자에 대한 스테레오타입, 두려움, 낙인이 이성간 [39]차이를 가진 아이들에게 강요되고 강압적인 의료 개입에 대한 이유를 제공하는 방법"을 모두 밝히고 있다.

SIPD 우간다의 Julius Kaggwa는 동성애자 커뮤니티가 "상대적인 안전의 장소를 제공하지만, 그것은 또한 우리의 특정한 요구를 [40]망각하고 있다"고 썼다.마우로 카브랄은 트랜스젠더라는 것을 설명하기 위한 수단으로서 간성을 사용하는 것을 포함하여 트랜스젠더 사람들과 단체들은 간성 문제에 대해 "트랜스 이슈인 것처럼 접근하는 것을 멈출 필요가 있다"고 썼다. "우리는 그 접근법이 [41]얼마나 잘못된 것인지 명확히 함으로써 간성 운동에 많은 협력을 할 수 있다."

피죤 파고니스는 LGBTQA에 I를 추가하는 것은 대표성을 높이는 데 도움이 될 수도 있고 그렇지 않을 수도 있으며, 이성간 조직에 대한 자금 지원 기회를 증가시킬 수도 있지만,[42] LGBTQA와 관련된 낙인 때문에 이성간 아이들에게도 해로울 수 있다고 말한다.Organization Intersex International Australia는 일부 이성간 개인은 끌리고 일부는 이성간이지만, "LGBTI 행동주의는 예상된 이원적 성과 성 [43][44]규범을 벗어나는 사람들의 권리를 위해 싸워왔다"고 말한다.

2020년 7월 1일, 러시아 간 성단체(Interseks.ru, ARSI, NFP+, Intersex Russia)는 LGBTI 약자 사용에 관한 성명을 발표하고 성적 성향과 [45]성 정체성을 바탕으로 개인의 태도에 편견과 폭력이 만연된 국가들에 대해 LGBTI 약자를 사용하지 말 것을 촉구했다.

법의 이성 보호

코야마 에미씨는 LGBTI에 이성간 성관계를 포함시키는 것이 LGBTI를 보호하는 법에 의해 "성간자의 권리가 보호되고 있다"는 잘못된 인상을 심어주고 많은 이성간 사람들이 [46]LGBT가 아니라는 것을 인정하지 않는 등 LGBTI의 특정 인권 문제에 어떻게 대처하지 못할 수 있는지를 설명한다.

남아프리카 공화국은 성별을 이유로 한 차별 금지의 일환으로 이성 간 사람들을 차별으로부터 보호한다.국제성별기구(OECD)는 성적 성향과 성 정체성에 따른 보호가 [47][48][49]불충분하다고 주장하며 차별금지법에 "간성 지위"라는 법적 속성을 포함시키기 위해 로비를 성공적으로 진행했다.2015년 [50]몰타 법안에 따라, 성 특성의 속성이 [35]더 널리 퍼지고 있다.

'핑크워싱'

여러 단체는 성간 아동에 대한 불필요한 "정상화" 간 의료 개입 문제를 다루지 못하는 LGBT 인권 인정에 대한 호소력을 강조해 왔다.2001년 북미 간 성학회지(현재는 폐지)에 실린 논문에서 코야마 에미 씨와 리사 위즐 씨는 간성 문제에 대한 가르침은 "막혔다"고 말했습니다.

이것은 정말로 여성, 성별, 그리고 퀴어 연구에서 공통적인 문제인 것처럼 보인다: 간성 존재에 대한 논의는 간성 사람들의 삶에 직접적으로 영향을 미치는 의학 윤리나 다른 문제들을 다루기 보다는 성, 성 역할, 강제 이성애, 그리고 심지어 서구 과학을 해체하기 위해 사용되는 곳에서 "차단"된다.그러나 이것은 상황을 설명하는 부정확한 방법일 수도 있습니다. 진실은 이러한 논의가 너무 일찍 "막힌" 것이 아니라 잘못된 우선순위의 장소에서 출발하고 있다는 것입니다.[51]

2016년 6월, Organization Intersex International Australia는 호주 정부의 모순된 진술을 지적하면서, LGBT와 이성 간 사람들의 존엄성과 권리는 인정되고 동시에 이성 간 아동에 대한 유해한 관행은 [52]계속되고 있음을 시사했다.

2016년 8월, Zwischengeschlecht는 핑크워싱의 [53]한 형태로서 "성간 성기 훼손"을 금지하는 조치 없이 평등 또는 시민적 지위 입법을 촉진하는 행동을 묘사했다.이 기구는 앞서 [54]유엔조약기구(UN Treaty Bodies)에 대해 영유아에 대한 유해 관행에 대처하는 대신 간성, 트랜스젠더 및 성소수자 문제를 혼동하는 회피적인 정부 성명을 강조해 왔다.

조건.

LGBT+는 레즈비언, 게이, 양성애자, 트랜스젠더 등을 뜻하는 이니셜리즘이다.이니셜리즘은 자기 지명으로 주류가 되어 미국뿐만 아니라 많은 다른 나라의 [55][56]성, 성 정체성에 기초한 커뮤니티 센터와 미디어에 의해 채택되고 있다.

또 다른 변종은 LGBTQIA로,[57] 예를 들어 데이비스 캘리포니아 대학의 "레즈비언, 게이, 양성애자, 트랜스젠더, 퀴어, 인터섹스, 무성자원센터"에서 사용되고 있다.

미국 국립보건원(NIH)은 LGBT, 기타 "성적 성향 및/또는 성별 정체성이 다른 사람, LGBT로 자신을 식별하지 않을 수 있는 사람" 및 간성 인구(성 발달 장애자)를 "성적 및 성별 소수자"(SGM) 모집단으로 분류했다.이를 통해 NIH SGM 헬스 리서치 전략 [58]플랜이 개발되었습니다.

퀴어의 개념은 또한 LGB의 이니셜을 형성하기 위해 포함될 수 있다.TIQ[59] 및 LGTBIQ(스페인어).[60]

기타 교차로

이성 및 아동의 권리

킴벌리 지젤맨ACT는 LGBT 커뮤니티가 어떻게 문호를 개방하는 것을 도왔는지, 그러나 이성간의 권리가 얼마나 넓은지에 대해 기술했다: "핵심에는 아동의 권리 문제가 있다.또한 건강과 생식권에 관한 것입니다.왜냐하면 이러한 수술은 [61]불임으로 이어질 수 있기 때문입니다.

이성간 장애

여러 저자와 시민사회단체는 의료화 문제와 이식 전 유전자 [62]진단의 사용으로 인해 이성간 사람과 장애 사이의 상호관계를 강조한다.간성 특성을 제거하기 위한 이식 전 유전자 진단의 사용에 대한 분석에서, Behrmann과 Ravitsky는 "간성에 대한 부모의 선택은... 동성 매력과 성별 [63]불일치에 대한 편견을 숨길 수 있다"고 말한다.

2006년 임상적으로 이성간 상태를 성 발달[64][65] 장애로 재구성한 결과 간성과 장애 사이의 연관성이 [66][67]명백해졌지만 수사학적 변화는 여전히 [68][69]논쟁의 여지가 많다.2016년 발표된 호주의 사회학적 연구에 따르면 응답자의 3%가 자신의 성 특성을 정의하기 위해 '성 발달 장애' 또는 'DSD'라는 용어를 사용했으며, 21%는 의료 서비스에 접근할 때 이 용어를 사용하는 것으로 나타났다.반면 60%는 자신의 [3]성 특성을 설명하기 위해 어떤 형태로든 "간성"이라는 용어를 사용했다.

미국에서 이성애자는 미국 장애인법에 [70]의해 보호된다.2013년, 호주 상원은 [71]장애인의 비자발적 또는 강압적 멸균에 대한 광범위한 조사의 일환으로 호주에서 이성간 불임 또는 강제적 멸균에 대한 보고서를 발간했다.유럽에서는 OII 유럽이 평등과 비차별, 고문으로부터의 해방, 그리고 그 사람의 완전성 보호에 관한 유엔 장애인 권리에 관한 협약의 여러 조항을 확인했다.그럼에도 불구하고, 그 단체는 간성을 장애로 매도하는 것은 의료화와 인권 부족을 강화시킬 수 있고, 자기 [72]정체성과 일치하지 않는다고 우려를 표명했다.

메모들

레퍼런스

- ^ UN Committee against Torture; UN Committee on the Rights of the Child; UN Committee on the Rights of People with Disabilities; UN Subcommittee on Prevention of Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment; Juan Méndez, Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment; Dainius Pῡras, Special Rapporteur on the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health; Dubravka Šimonoviæ, Special Rapporteur on violence against women, its causes and consequences; Marta Santos Pais, Special Representative of the UN Secretary-General on Violence against Children; African Commission on Human and Peoples' Rights; Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights; Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (October 24, 2016), "Intersex Awareness Day – Wednesday 26 October. End violence and harmful medical practices on intersex children and adults, UN and regional experts urge", Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, archived from the original on November 21, 2016

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: 여러 이름: 작성자 목록(링크) - ^ United Nations; Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (2015). Free & Equal Campaign Fact Sheet: Intersex (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-03-04.

- ^ a b c d Jones, Tiffany; Hart, Bonnie; Carpenter, Morgan; Ansara, Gavi; Leonard, William; Lucke, Jayne (2016). Intersex: Stories and Statistics from Australia (PDF). Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers. ISBN 978-1-78374-208-0. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 September 2016. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- ^ a b Furtado P. S.; et al. (2012). "Gender dysphoria associated with disorders of sex development". Nat. Rev. Urol. 9 (11): 620–627. doi:10.1038/nrurol.2012.182. PMID 23045263. S2CID 22294512.

- ^ United Nations; UNDP; OHCHR; UNAIDS; ILO; UNESCO; UNFPA; UNICEF; UNHCR; UN Women; UNODC; WFP; WHO (September 2015), Ending violence and discrimination against lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex people

- ^ a b c d Meyer-Bahlburg, Heino F.L. (January 1990). "Will Prenatal Hormone Treatment Prevent Homosexuality?". Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology. 1 (4): 279–283. doi:10.1089/cap.1990.1.279. ISSN 1044-5463.

- ^ a b Dreger, Alice; Feder, Ellen K; Tamar-Mattis, Anne (29 June 2010), Preventing Homosexuality (and Uppity Women) in the Womb?, The Hastings Center Bioethics Forum, archived from the original on 2 April 2016, retrieved 18 May 2016

- ^ a b "New publication "Intersex: Stories and Statistics from Australia"". Organisation Intersex International Australia. February 3, 2016. Archived from the original on August 29, 2016. Retrieved 2016-08-18.

- ^ Nimkarn, Saroj; New, Maria I. (April 2010). "Congenital adrenal hyperplasia due to 21-hydroxylase deficiency". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1192 (1): 5–11. Bibcode:2010NYASA1192....5N. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05225.x. ISSN 1749-6632. PMID 20392211. S2CID 38359933.

- ^ Dreger, Alice; Feder, Ellen K; Tamar-Mattis, Anne (June 29, 2010), "Preventing Homosexuality (and Uppity Women) in the Womb?", The Hastings Center Bioethics Forum, archived from the original on April 2, 2016, retrieved February 1, 2017

- ^ a b Holmes, Morgan (May 1994). "Re-membering a Queer Body". UnderCurrents. Faculty of Environmental Studies, York University, Ontario. 6: 11–130. Archived from the original on 2021-03-08. Retrieved 2021-03-19.

- ^ a b Carpenter, Morgan (2020). "Intersex human rights, sexual orientation, gender identity, sex characteristics and the Yogyakarta principles plus 10". Culture, Health & Sexuality. 23 (4): 516–532. doi:10.1080/13691058.2020.1781262. ISSN 1369-1058. PMID 32679003. S2CID 220631036.

- ^ Karkazis, Katrina (November 2009). Fixing Sex: Intersex, Medical Authority, and Lived Experience. Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0822343189.

- ^ Carpenter, Morgan (18 June 2013). "Australia can lead the way for intersex people". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 15 October 2014. Retrieved 2014-12-29.

- ^ Morland, Iain, ed. (2009). "Intersex and After". GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies. 15 (2). ISBN 978-0-8223-6705-5. Archived from the original on 2014-12-26. Retrieved 2014-12-26.

- ^ a b "Children's right to physical integrity, Report Doc. 13297". Council of Europe Parliamentary Assembly. 6 September 2013. Archived from the original on 26 December 2013.

- ^ "Trans? Intersex? Explained!". Inter/Act. Archived from the original on 2014-10-18. Retrieved 2013-07-10.

- ^ "Basic differences between intersex and trans". Organisation Intersex International Australia. 2011-06-03. Archived from the original on 2014-09-04. Retrieved 2013-07-10.

- ^ Cabral Grinspan, Mauro (October 25, 2015), The marks on our bodies, Intersex Day, archived from the original on April 5, 2016

- ^ "Australian Government Guidelines on the Recognition of Sex and Gender, 30 May 2013". Archived from the original on 1 July 2015. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ^ a b Holme, Ingrid (2008). "Hearing People's Own Stories". Science as Culture. 17 (3): 341–344. doi:10.1080/09505430802280784. S2CID 143528047.

- ^ "New Zealand Passports - Information about Changing Sex / Gender Identity". Archived from the original on 23 September 2014. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ^ "Third sex option on birth certificates". Deutsche Welle. 1 November 2013. Archived from the original on 10 October 2014.

- ^ "Germany allows indeterminate gender on birth register". Reuters. 21 August 2013. Archived from the original on 24 July 2020. Retrieved 23 July 2020.

- ^ Carpenter, Morgan (20 August 2013). "German proposals for a "third gender" on birth certificates miss the mark". Intersex Human Rights Australia. Archived from the original on 20 September 2020. Retrieved 23 July 2020.

- ^ "Sham package for Intersex: Leaving sex entry open is not an option". OII Europe. 15 February 2013. Archived from the original on 29 August 2014. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- ^ "Intersex: Third Gender in Germany" (Spiegel, Huff Post, Guardian, ...): Silly Season Fantasies vs. Reality of Genital Mutilations". Zwischengeschlecht. 1 November 2013. Archived from the original on 24 June 2017. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- ^ 전 세계 이성 커뮤니티가 공통 목표를 확인 2013-12-06년 Wayback Machine, Star Observer, 2013년 12월 4일 아카이브

- ^ "Malta Declaration". OII Europe. Archived from the original on 2020-08-18. Retrieved 2020-07-23.

- ^ "X marks the spot for intersex Alex" (PDF). West Australian, via bodieslikeours.org. 11 January 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 November 2013. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- ^ "남자도 여자도 아니다" 2016-04-24년 시드니 모닝 헤럴드 웨이백 머신에 보관.2010년 6월 27일

- ^ O'Hara, Mary Emily (September 26, 2016). "Californian Becomes Second US Citizen Granted 'Non-Binary' Gender Status". NBC News. Archived from the original on September 26, 2016. Retrieved September 26, 2016.

- ^ O'Hara, Mary Emily (December 29, 2016). "Nation's First Known Intersex Birth Certificate Issued in NYC". NBC News. Archived from the original on December 30, 2016. Retrieved 2016-12-30.

- ^ Holmes, Morgan (July 2004). "Locating Third Sexes". Transformations Journal (8). ISSN 1444-3775. Archived from the original on 2017-01-10. Retrieved 2014-12-28.

- ^ a b Asia Pacific Forum of National Human Rights Institutions (June 2016). Promoting and Protecting Human Rights in relation to Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity and Sex Characteristics. ISBN 978-0-9942513-7-4. Archived from the original on 2017-01-15.

- ^ Dreger, Alice (4 May 2015). "Reasons to Add and Reasons NOT to Add "I" (Intersex) to LGBT in Healthcare" (PDF). Association of American Medical Colleges. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 June 2016. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

- ^ 윌리엄 L. 모리스, 마조리 A.Bowman, 1차 진료 중 성의학 2015-09-06 Wayback Machine, Mosby Year Book, 1999, ISBN 978-0-8151-2797-0

- ^ Aragon, Angela Pattatuchi (2006). Challenging Lesbian Norms: Intersex, Transgender, Intersectional, and Queer Perspectives. Haworth Press. ISBN 978-1-56023-645-0. Archived from the original on 2012-11-22. Retrieved 2008-07-05.

- ^ Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (October 2019), Background Note on Human Rights Violations against Intersex People, archived from the original on 2020-01-29, retrieved 2020-03-05

- ^ Kaggwa, Julius (September 19, 2016). "I'm an intersex Ugandan – life has never felt more dangerous". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on October 6, 2016. Retrieved 2016-10-03.

- ^ Cabral, Mauro (October 26, 2016). "IAD2016: A Message from Mauro Cabral". GATE - Global Action for Trans Equality. Archived from the original on November 3, 2016. Retrieved 2016-11-12.

- ^ Pagonis, Pidgeon (June 2016). "7 Ways Adding 'I' to the LGBTQA+ Acronym Can Miss the Point". Everyday Feminism. Archived from the original on 2017-01-09.

- ^ "Intersex for allies". 21 November 2012. Archived from the original on 7 June 2016. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

- ^ "OII releases new resource on intersex issues, Intersex for allies and Making services intersex inclusive by Organisation Intersex International Australia". Gay News Network. 2 June 2014. Archived from the original on 6 June 2014.

- ^ "Statement on the use of the abbreviation "LGBTI."". ARSI. 2020-06-20. Archived from the original on 2022-03-11. Retrieved 2021-06-12.

- ^ Koyama, Emi. "Adding the "I": Does Intersex Belong in the LGBT Movement?". Intersex Initiative. Archived from the original on 17 May 2016. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

- ^ Carpenter, Morgan; Organisation Intersex International Australia (2012-12-08). Submission on the proposed federal Human Rights and Anti-Discrimination Bill. Organisation Intersex International Australia. Sydney. Archived from the original on 2017-03-03.

- ^ "Sex Discrimination Amendment (Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity and Intersex Status) Act 2013, No. 98, 2013, C2013A00098". ComLaw. 2013. Archived from the original on 2014-10-06. Retrieved 2017-02-01.

- ^ "On the historic passing of the Sex Discrimination Amendment (Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity and Intersex Status) Act 2013". Organisation Intersex International Australia. 25 June 2013. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- ^ Malta (April 2015), Gender Identity, Gender Expression and Sex Characteristics Act: Final version, archived from the original on 2015-07-05, retrieved 2017-02-01

- ^ Koyama, Emi; Weasel, Lisa (June 2001). "Teaching Intersex Issues" (PDF). Intersex Society of North America. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-05-17.

- ^ "Submission: list of issues for Australia's Convention Against Torture review". Organisation Intersex International Australia. June 28, 2016. Archived from the original on September 16, 2016. Retrieved February 1, 2017.

- ^ ""Intersex legislation" that allows the daily mutilations to continue = PINKWASHING of IGM practices". Zwischengeschlecht. August 28, 2016. Archived from the original on September 19, 2016.

- ^ "TRANSCRIPTION > UK Questioned over Intersex Genital Mutilations by UN Committee on the Rights of the Child - Gov Non-Answer + Denial". Zwischengeschlecht. May 26, 2016. Archived from the original on September 19, 2016.

- ^ Centerlink. "2008 Community Center Survey Report" (PDF). LGBT Movement Advancement Project. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 17, 2014. Retrieved August 29, 2008.

- ^ "NLGJA Stylebook on LGBT Terminology". nlgja.org. 2008. Archived from the original on 2009-04-28.

- ^ "Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Intersex, Asexual Resource Center". University of California, Davis. September 21, 2015. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved 2017-01-20.

- ^ Alexander, Rashada; Parker, Karen; Schwetz, Tara (October 2015). "Sexual and Gender Minority Health Research at the National Institutes of Health". LGBT Health. 3 (1): 7–10. doi:10.1089/lgbt.2015.0107. ISSN 2325-8292. PMC 6913795. PMID 26789398.

- ^ "Learning about LGBTIQ". LGBTIQ. Monash University. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 30 June 2021.

LGBTIQ stands for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Intersex and Queer. You may have seen alternative versions of the abbreviation such as GLBT, LGBTQIA+, LGBTTIQQ2SA or LGBTIH, to name just a few. Sometimes, you’ll see the word Queer used as an umbrella term for these various identities as well.

- ^ "LGTBIQ: el significado de las siglas con las que se identifica el colectivo". LaSexta (in European Spanish). 2019-06-28. Archived from the original on 2021-01-20. Retrieved 30 June 2021.

- ^ Stewart, Philippa (2017-07-25). "Interview: Intersex Babies Don't Need 'Fixing'". Human Rights Watch. Archived from the original on 2017-08-03. Retrieved 2017-07-25.

- ^ Holmes, M. Morgan (June 2008). "Mind the Gaps: Intersex and (Re-productive) Spaces in Disability Studies and Bioethics". Journal of Bioethical Inquiry. 5 (2–3): 169–181. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.566.1260. doi:10.1007/s11673-007-9073-2. ISSN 1176-7529. S2CID 26016185.

- ^ Behrmann, Jason; Ravitsky, Vardit (October 2013). "Queer Liberation, Not Elimination: Why Selecting Against Intersex is Not "Straight" Forward". The American Journal of Bioethics. 13 (10): 39–41. doi:10.1080/15265161.2013.828131. ISSN 1526-5161. PMID 24024805. S2CID 27065247.

- ^ Houk, C. P.; Hughes, I. A.; Ahmed, S. F.; Lee, P. A.; Writing Committee for the International Intersex Consensus Conference Participants (August 2006). "Summary of Consensus Statement on Intersex Disorders and Their Management". Pediatrics. 118 (2): 753–757. doi:10.1542/peds.2006-0737. ISSN 0031-4005. PMID 16882833. S2CID 46508895.

- ^ Hughes, I A; Houk, C; Ahmed, S F; Lee, P A; LWPES1/ESPE2 Consensus Group (June 2005). "Consensus statement on management of intersex disorders". Archives of Disease in Childhood. 91 (7): 554–563. doi:10.1136/adc.2006.098319. ISSN 0003-9888. PMC 2082839. PMID 16624884.

- ^ Cornwall, Susannah (April 2015). "Intersex and the Rhetorics of Disability and Disorder: Multiple and Provisional Significance in Sexed, Gender, and Disabled Bodies". Journal of Disability & Religion. 19 (2): 106–118. doi:10.1080/23312521.2015.1010681. hdl:10871/28804. ISSN 2331-2521. S2CID 146427737.

- ^ Koyama, Emi (February 2006). "From "Intersex" to "DSD": Toward a Queer Disability Politics of Gender". University of Vermont. Archived from the original on 2015-09-28. Retrieved 2017-02-01.

{{cite journal}}:Cite 저널 요구 사항journal=(도움말) - ^ Davis, Georgiann (11 September 2015). Contesting Intersex: The Dubious Diagnosis. New York University Press. pp. 87–89. ISBN 978-1479887040.

- ^ Holmes, Morgan (September 2011). "The Intersex Enchiridion: Naming and Knowledge". Somatechnics. 1 (2): 388–411. doi:10.3366/soma.2011.0026. ISSN 2044-0138.

- ^ Menon, Yamuna (May 2011). "The Intersex Community and the Americans with Disabilities Act". Connecticut Law Review. 43 (4): 1221–1251. Archived from the original on 2017-02-02.

- ^ Senate of Australia; Community Affairs References Committee (2013). Involuntary or coerced sterilisation of intersex people in Australia. Australian Senate. Canberra. ISBN 978-1-74229-917-4. Archived from the original on 2015-09-23.

- ^ OII Europe (April 2015). Statement of OII Europe on Intersex, Disability and the UN Convention on the Rights of People with Disabilities (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-03-27.