그리코인

Griko people | |

| 총인구 | |

|---|---|

| c. 8만 | |

| 모집단이 유의한 지역 | |

| 이탈리아 남부(특히 보베시아와 살렌토) | |

| 54,278 (2005)[1] | |

| 22,636 (2010) | |

| 500 (2012)[2][3] | |

| 언어들 | |

| 그리스어(그리코와 칼라브리아 방언), 이탈리아어, 살렌티노, 칼라브레세 | |

| 종교 | |

| 라틴계 가톨릭 다수파, 이탈로-그리스계 가톨릭교회 소수파 | |

| 관련 민족 | |

| 다른 그리스인, 시칠리아인, 이탈리아인 | |

a 총 인구수는 보베시아와 그레시아 살렌티나 지역의 그리코인만 포함한다. 이들 지역 외 지역 출신 그리코인의 수는 아직 정해지지 않았다. | |

그리코족(그리스어: γκίκο)은 칼라브리아에서 그레카니치로도 알려져 있으며,[4][5][6][7][8][9] 남이탈리아의 그리스 민족 공동체다.[10][11][12][13] 주로 칼라브리아(레지오 칼라브리아 섬)와 아풀리아(살렌토 페닌술라) 지역에서 발견된다.[14] 그리코 공동체가 고대 그리스인들의 직계 후손인지, 비잔틴 지배 동안 더 최근의 중세 이주에서 온 것인지에 대해서는 학자들 사이에 논쟁이 있지만 그리코는 한때 규모가 컸던 남부[13] 이탈리아(고대 마그나 그라시아 지역)의 고대 그리스 공동체의 잔재로 여겨진다.[15]

그리코 사투리의 기원에 대한 오랜 논쟁은 그리코의 기원에 대한 두 가지 주요 이론을 만들어냈다. 1870년 주세페 모로시에 의해 개발된 제1 이론에 따르면 그리코는 비잔틴 시대[...]에 그리스에서 살렌토까지 이민자들의 물결이 왔을 때 헬레니즘 코인에서 비롯되었다고 한다.[16] 모로시, G. Rohlfs가 하쯔다키스(1892년)의 뒤를 이어, 그리코가 고대 그리스로부터 직접 진화한 지역 품종이라는 것을 대신하여 클램프 했다.[17]

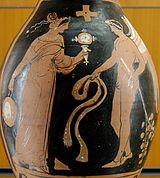

그리스인들은 기원전 8세기 고대 그리스 식민지화부터 오스만 정복으로 인한 15세기 비잔틴 그리스 이주까지 수많은 이주 물결 속에서 남이탈리아에 처음 도착한 수천 년 동안 남부 이탈리아에 거주해 왔다. 중세에는 그리스의 지역사회가 고립된 지역으로 전락했다. 비록 남이탈리아에 거주하는 대부분의 그리스인들이 수세기에 걸쳐 완전히 이탈리아화되었지만,[18][12][14] 그리코 공동체는 대중매체에 노출되어 그들의 문화와 언어가 점차적으로 침식되어 왔음에도 불구하고 그들의 원래 그리스 정체성, 유산, 언어, 뚜렷한 문화를 보존할 수 있었다.[19]

그리코족은 전통적으로 그리스어의 한 형태인 이탈리아어(그리에코어 또는 칼라브리아어 방언)를 사용한다. 최근 몇 년 동안 그리코어를 사용하는 그리코의 수가 크게 줄었고, 젊은 그리코는 이탈리아어로 빠르게 옮겨갔다.[20] 오늘날 그리코는 가톨릭 신자다.

이름

그리코라는 이름은 이탈리아 반도에 있는 그리스인들의 전통적인 이름에서 유래한 것으로, 전설에 따르면 그라이코스에서 그들의 이름을 따온 고대 헬레닉 부족인 그라키아인에서 유래한 것으로 여겨진다. 그들은 이탈리아를 식민지로 삼은 최초의 그리스 부족들 중 하나였다. 마그나 그라시아로 알려지게 된 지역은 그들의 이름을 따서 이름이 붙여졌다. 라틴인들은 이 용어를 모든 헬레니족과 관련하여 사용했다. 왜냐하면 그들이 처음 접촉한 헬레네인들은 그리스인이고, 따라서 그리스인이라는 이름이었기 때문이다. 또 다른 의견으로는 γρκο/α라는 민족명칭이 라틴 그라쿠스나 그리스 그라이코스에서 언어학적으로 유래하지 않는다는 것이다; 비록 이것이 많은 사람들 사이에 하나의 언어 가설일 뿐이지만, 그것은 로마 이전의 그리스어 사용자들에게 사용되었던 고대 이탈리아어 이웃들의 용어였을지도 모른다.[21]

분배

그리스어를 사용하는 보베시아의 영토는 매우 산악지형에 위치해 있어서 쉽게 접근할 수 없다. 근래에는 이 지역의 초기 거주자들의 많은 후손들이 해안가에 집을 마련하기 위해 산을 떠났다. 칼라브리아의 그리코 화자들은 보바 수페리오레, 보바 마리나, 로카포르테 델 그레코, 콘도푸리, 팔리지, 갈리시아노, 멜리토 디 포르토 살보의 마을에 산다. 1999년 이탈리아 의회는 482 법까지 역사적인 그리코 영토를 확장하여 팔리지, 산 로렌초, 슈타이트, 사모, 몬테벨로 조노노, 바갈라디, 모타 산 조반니, 브란칼레오네, 레지오 일부 지역을 포함시켰다.[22] In the Grecia Salentina region of Apulia, the Griko-speakers are to be found in the villages of Calimera, Martignano, Martano, Sternatia, Zollino, Corigliano d'Otranto, Soleto, Melpignano and Castrignano dei Greci, although Grico seems to be disappearing from Martignano, Soleto and Melpignano. 보베시아와 그레시아 살렌티나 지역 밖의 그리코족에 의해 거주하고 있는 마을들은 거의 전적으로 그리코 언어의 지식을 잃었다; 이것은 주로 19세기 후반과 20세기에 일어났다. 그리코 혓바닥의 지식을 잃은 도시로는 칼라브리아의 카르데토, 몬테벨로, 산 판탈레온, 산타 카테리나 등이 있다. At the beginning of the nineteenth century today's nine Greek-speaking cities of the Grecía Salentina area along with Sogliano Cavour, Cursi, Cannole and Cutrofiano formed part of the Decatría Choría (τα Δεκατρία Χωρία)[23] the thirteen cities of Terra d'Otranto who preserved the Greek language and traditions. 좀 더 외진 시기에 갈라티나,[24] 갈라토네, 갈리폴리 등 아풀리아 지방과 [25]칼라브리아의 카탄자로, 코센자 등지에서 그리스어가 널리 쓰이기도 했다.[26]

이탈리아의 마을

| 다음에 대한 시리즈 일부 |

| 그리스인 |

|---|

|

| 나라별 |

| 원주민 공동체 그리스 · 키프로스 알바니아 · 이탈리아 · 러시아 · 터키 그리스 디아스포라 호주. · 캐나다 · 독일. 영국 · 미국 |

| 영역별 그룹 |

| 그리스 북부: 에피로테스 (북에피로테스) ·마케도니아인·테살리아인·트라키아인(콘스탄티노폴리스인) 그리스 남부: 펠로폰네소스(마니아어, 차코니아어) ·루멜리오테스 그리스 동부 지역: 마이크로사이드 (에올리스, 비티니아, 도리스, 이오니아, 스미르나) 카파도키아인·카라만리데스·폰틱(카우카소스, 크림) 그리스 섬 주민: 키오테스·크레탄스·사이클라다이트·키프로스·도데카네시안·에프타네시아인·이카리오테스·렘니오테스·레스비아인·사미오테스 기타 그리스 그룹: 아르바나이트·이집티오테스·그레카니치·사라카타니 슬라보폰족·술리오테스·우룸스 |

| 그리스 문화 |

| 예술 · 시네마 · 요리. 춤 · 드레스 · 교육 깃발 · 언어 · 문학 음악 · 정치 · 종교 스포츠 · 텔레비전 · 극장 |

| 종교 |

| 그리스 정교회 그리스 로마 가톨릭교회 그리스 비잔틴 가톨릭교회 그리스 복음주의 유대교 · 이슬람교 · 네오파간주의 |

| 언어 및 방언 |

| 그리스어 칼라브리안 그리스어 카파도키아어 크레탄 그리스어 · 그리코 키프로스 그리스어 · 히마리오테 그리스어 마니오트 그리스어 · 마리우폴 그리스어 폰틱 그리스어 · 차코니아어 예바닉 |

| 그리스의 역사 |

그리코 마을에는 보통 두 개의 이름이 있는데, 이탈리아 이름뿐만 아니라 마을 사람들이 이 마을을 가리키는 고유 그리코 이름이다. 그리코 마을은 일반적으로 남부 이탈리아 지역에서 작은 섬으로 나뉜다.

- 아풀리아

- 살렌토 현 (그레시아 살렌티나 외곽)

- 칼라브리아; 칼라브리아 그리스 지방

- 아프리카어:[22] άρινννν

- 수정골레아:[22] 아미달리아

- 아르모[33]

- 바갈라디:[22] 바갈라데스

- Bova:[22] Chòra tu Vùa (βοῦα), i Chora (ἡἡώαα)[34]

- 보바 마리나: 잘로 투 비아

- 브란칼레오네[22]

- 카르데토:[22][35] 카디아

- 카타포리오:[33]카타치리오

- Condofuri:[22][36] Kontofyria, o Condochòri (Κοντοχώρι «near the village»)[37]

- 갈리시아누스[22]

- 라가나디:[33] 라차나디, 라차나데스

- 루브리치[33]

- 멜리토 디 포르토 살보: [22]멜리토스 또는 멜리토

- 몬테벨로[22]

- 모소로파:[33] 메슈초라

- 모타산조반니[22]

- 팔리지:[22] 스피루폴리

- 파라코리오가[33] 1878년에 페도볼리[33] 마을과 합병하여 현재의 델리아누오바 마을로 들어갔다. 딜리아

- 푸테타틸로[36]

- 포다르고니:[38] 포다호니

- 폴리스테나[39]

- 레조 디 칼라브리아 뢰기

- Rocaforte del Greco:[22][40] 부니(ββουνίίίίίίίίίmountmountmountmountmount

- 로구디온:[22] 로구디온, 초리,, 리쿠디(ῥηχδδδδδrockrockrockrockrock rockrock »)[41]

- 사모:[22]사무

- 산판탈레온[36]

- 산로렌초[22][36]

- 산타카테리나[35][42]

- 산조르조[33]

- 스키도:[33] 스키도스

- 시노폴리:[43] 제노폴리스, 시노폴리스

- 시티차노[33]

- 스타티:[22] 스타티

- 라피아노 디 몬테레오네 지방

공식현황

1999년 법 제482호에 의해, 이탈리아 의회는 레지오 칼라브리아와 살렌토의 그리코 공동체를 그리스 민족 및 언어적 소수민족으로 인정했다. 이것은 공화국이 알바니아어, 카탈로니아어, 게르만어, 그리스어, 슬로베니아어, 크로아티아어, 그리고 프랑스어, 프로벤살어, 프릴리언어, 라딘어, 오시칸어, 사르디니아어를 사용하는 사람들의 언어와 문화를 보호한다고 명시하고 있다.[45]

역사

조기 마이그레이션

그리스와 이탈리아와의 첫 접촉은 미케네아 그리스인들이 중남 이탈리아와 시칠리아에 정착한 선사시대 이후 증명된다.[46][47][48][49] 고대에는 기원전 8세기부터 고대 그리스인에 의해 칼라브리아, 루카니아, 아풀리아, 캄파니아, 시칠리아 연안을 포함한 나폴리 남쪽의 이탈리아 반도가 식민지화되었다.[50] 그리스인들의 정착지는 그곳에서 매우 조밀하게 수집되어 고전주의 시대에 그 지역은 마그나 그라시아(그리스보다 그리스)라고 불리게 되었다.[50] 그리스인들은 고대부터 15세기 비잔틴의 이주만큼 늦게까지 많은 물결 속에서 이 지역으로 계속 이주했다.

이후 마이그레이션

초창기 중세 동안, 참혹한 고딕 전쟁에 뒤이어 남이탈리아가 비잔틴 제국의 느슨한 지배를 받음에 따라 그리스인들의 새로운 물결이 그리스와 아시아 마이너에서 마그나 그라시아로 밀려왔다.[citation needed] 우상숭배한 황제 레오 3세는 교황에게 부여된 남부 이탈리아에 있는 땅을 전용했고,[51] 동황제는 롬바드가 등장할 때까지 이 지역을 느슨하게 통치하다가, 이탈리아의 카타파나이트의 형태로 노르만족에 의해 대체되었다. 더구나 비잔틴인들은 남이탈리아 사람들에게 공통의 문화적 뿌리를 두고 있는 마그나 그라시아의[citation needed] 그리스어 에레디 엘렌노포니(Eredi Ellenofoni)를 발견했을 것이다. 그리스어는 라틴어의 발달로 사용 영역이 현저하게 줄어들었지만, 남부 이탈리아에서 완전히 소멸된 적은 없었다.[52] 마그나 그라시아가 그리스어를 주로 사용한다는 기록은 11세기[citation needed] 후반까지 거슬러 올라간다(남이탈리아의 비잔틴 지배 말기). 이 시기에 비잔틴 제국으로 재통합된 남이탈리아의 일부 지역은 노르만 정복 당시 그리스 인구가 압도적으로 많았던 칠렌토와 같이 그리스인들이 더욱 북쪽에 정착하기 시작하면서 상당한 인구 변화를 겪기 시작했다.[53][54]

중세 말경에는 칼라브리아, 루카니아, 아풀리아, 시칠리아 등의 많은 지역이 그리스어를 모국어로 계속 사용하였다.[55] 13세기 동안 칼라브리아 전역을 지나는 프랑스의 고수는 "칼라브리아의 농민들은 그리스어밖에 말하지 않았다"[not specific enough to verify][56]고 말했다. 1368년 이탈리아의 학자 페트라르크는 그리스어에 대한 그의 지식을 향상시킬 필요가 있는 학생에게 칼라브리아에서의 체류를 권했다.[56] 그리코족은 16세기까지 칼라브리아와 살렌토 일부 지역의 지배적인 인구 요소였다.[57][58][59][54]

15세기와 16세기 동안 남부 이탈리아와 시칠리아에 있는 그리스 인구의[60] 가톨릭화와 라틴어화의 느린 과정은 그리스 언어와 문화를 더욱 감소시킬 것이다.[61] 1444년 갈라토네에서 태어난 그리스인 안토니오 데 페라리스는 칼리폴리(아풀리아의 갈리폴리)의 주민들이 그리스 모국어로 여전히 대화하는 모습을 관찰하면서 그리스 고전 전통이 이탈리아의 이 지역에 살아 있었으며 인구는 아마도 라케다에몬(스파르타) 주식일 것이라고 암시했다.[62][63][64] 남이탈리아의 그리스인들은 크게 줄었지만 칼라브리아와 푸글리아에 있는 고립된 거주지에서 여전히 활동했다. 중세 이후에도 그리스 본토로부터의 산발적인 이주가 있었다. 그리하여 16세기와 17세기에 상당한 수의 난민이 이 지역에 유입되었다. 이는 오스만족이 펠로폰네세스를 정복한 것에 대한 반발에서 일어났다.

20세기 동안 그리코 언어의 사용은 많은 그리코인들 자신들에 의해서도 후진성의 상징이자 진보의 장애물로 여겨졌고,[65] 부모들은 그들의 자녀들이 사투리를 말하는 것을 단념시킬 것이고 수업 중에 그리코를 이야기하다 들킨 학생들은 벌을[citation needed] 받았다. 여러 해 동안 칼라브리아와 아풀리아의 그리코는 잊혀져 왔다. 그리스에서도 그리스인들은 자신들의 존재를 모르고 있었다.

그리코 국가 각성

| "우리는 우리 민족을 부끄럽게 여기지 않는다. 우리는 그리스인이며, 우리는 그 안에서 영광을 누린다." |

| 안토니오 데 페라리스 (1444–1517), 갈라토네, 아풀리아[66][67] |

그리코 국가 각성은 칼리메라 마을 출신인 비토 도메니코 팔룸보(1857–1918)의 노동을 통해 그레시아 살렌티나에서 시작되었다.[68] 팔룸보는 그리스 본토와 문화 교류를 재정립하기 시작했다. 그는 마그나 그라시아의 그리코의 민화, 신화, 설화, 대중가요를 연구했다. 주목이 되살아난 것도 그리코어의 문서화와 보존에 크게 기여한 독일어 언어학자 겸 언어학자 게르하르트 로울프스의 선구적인 업적 덕분이다. 칼리메라의 에르네스토 아프리레 교수는 2008년 사망할 때까지 그리코 시, 역사, 공연의 보존과 성장을 위한 지역 사회의 지원을 시민적 책임으로 간주하고, 지역 및 국가적인 보급에 관한 여러 권의 모노그래프를 발간하여 방문객과 고관들에게 인정받지만 비공식적으로 대변하는 역할을 했다. 칼리메라와 인근 멜렌두그로의 바닷가 부분까지요

문화

음악

그리코는 풍부한 민속과 구전 전통을 가지고 있다. 그리코 노래, 음악, 시는 이탈리아와 그리스에서 인기가 있으며 살렌토 출신의 유명 음악 그룹에는 게토니아, 아라미레 등이 있다. 또한 조지 달라라스, 디오노펜스 사보풀로스, 마리넬라, 하리스 알렉시우, 마리아 파란투리 등 그리스의 영향력 있는 예술가들이 그리코어로 공연한 바 있다. 매년 여름 살렌토의 작은 마을인 멜피냐노에서는 유명한 노트 델라 타란타 축제가 열리는데, 피치카와 그리코 살렌티노 사투리의 가락에 맞춰 밤새도록 춤을 추는 수천 명의 젊은이들이 참가한다. 대중 매체에 대한 노출이 증가하면서 그리코 문화와 언어가 점점 더 침식되고 있다.[19]

그리코 음악의 다른 음악 그룹들은 살렌토에서 온 음악 그룹들을 포함한다. 아그리끄, 아르갈료, 아라크네 메디테라니아, 아스테리아, 아타나톤, 아벨다, 브리지안티 디 테라 도트란토, 칸소니에레 그레카니코 살렌티노, 오페리나 조에, 게토니아, 칼라브리아 출신: 아스타키, 니스타니메라, 스텔라 델 수드, 타 스키피슈빌리타, 그리스 출신: 엔카르디아.[69] 엔카르디아는 그리코 사람들의 음악에 영감을 받아 축하하는 다큐멘터리 영화 '엔카르디아, 춤추는 돌'의 소재였다.[70]

언어

그리코의 조상 모국어는 두 가지 독특한 그리스 방언을 형성하는데, 가토이탈리오티카(문학적으로 "남이탈리아어"), 그레카니카어 및/또는 그리코어로 통칭되며, 둘 다 표준 현대 그리스어와 어느 정도 상통할 수 있다. 아풀리아의 그리코 사람들은 칼라브리아에서 사용되는 칼라브리아 방언과는 반대로 그리코 방언을 쓴다. 중세까지 그리고 심지어 오늘날까지 살아남은 이 방언들은 고대 그리스의 식민지 개척자인 코인 그리스어와 중세 비잔틴 그리스어에 의해 마그나 그라시아에서 사용되는 고대 그리스어의 특징, 소리, 문법, 어휘를 보존한다.[71][52][71][72][73][74]

그리코 언어는 이탈리아어로의 언어 이동으로 인해 최근 수십 년간 화자의 수가 감소했기 때문에 심각한 멸종 위기에 처한 것으로 분류된다.[20] 오늘날 그것은 대략 20,000명의 노인들에 의해 말해지는 반면, 가장 어린 연사들은 30세 이상의 경향이 있고 소수의 어린이 연사들만이 존재한다.[20] 그리코어와 지역 로맨스 언어(칼라브레세와 살렌티노)는 수세기 내내 서로에게 큰 영향을 미쳤다.

칼라브리아 마피아([75][76]Calabrian Mafia)의 이름인 Ndrangheta는 칼라브리아 그리스어 유래어: 안다가티아(andragathia, ἀνδρααααααα)로, "아가시아"("값")와 "앤드르스("의 의미)로 구성되어 있다.

소수민족의 보존을 허가하는 이탈리아 헌법 제6조에도 불구하고, 이탈리아 정부는 그리코 민족의 언어와 문화를 점진적으로 침식하는 것을 보호하기 위해 거의 하지 않는다.[77] 이탈리아어의 사용은 공립학교에서 의무적으로 사용되지만, 그리코어는 그리코 청소년들에게 전혀 가르치지 않는다.

종교

동서시즘 이전에 그리코인들은 비잔틴 의식을 고수하는 가톨릭 신자였다.[80] 남이탈리아의 일부 그리스인들은 교황 요한 7세나 안티오페 요한 16세처럼 간신히 교회의 권좌에 올랐다. 11세기에 노르만인들은 남부 이탈리아를 넘어섰고, 곧 마지막 비잔틴 전초기지인 바리가 그들에게 함락되었다.[81] 그들은 라틴어화 과정을 시작했다. 그리스 성직자들은 결국 라틴의 의식에 대한 그리스인들의 저항이 칼라브리아에서 장기화되었지만 미사에 라틴어를 채택했다. 라틴어 원장들은 1093–6년까지 코센자, 비시냐노, 스퀼레이스에 설립되지 않았다. 1093년 노르만 왕 로저(Roger)가 압도적으로 많은 그리스계 로사노(Rossano) 인구 위에 라틴계 대주교를 설치하려 했지만, 이것은 완전한 실패였다,[82] 그러나 비잔틴 의식의 회복을 위한 반란이 일어났다.[83] 크로토네, 보바, 제라체에서 성직자들은 라틴어 주교들의 휘하에 있었음에도 불구하고 그리스어를 계속 사용하였다. 노르만족이 인민의 라틴어화에 대해 덜 격렬한 태도를 취했던 아풀리아에서 그리코인들은 그리스어를 구사하고 비잔틴 의식을 축하하기 위해 계속하였다.[84] 칼라브리아와 아풀리아 양쪽에 있는 일부 그리코는 17세기 초까지 비잔틴 의식의 신봉자로 남아 있었다.[84][better source needed] 오늘날 그리코 사람들은 대부분 라틴 의식을 고수하는 가톨릭 신자들이다.

문학

| "우리의 뿌리는 그리스인이지만 우리는 이탈리아에 있다. 우리의 피는 그리스인이지만 우리는 그레카니치라고 말했다. |

| 2001년 칼라브리아 미모 [85]니쿠라 |

초기 그리코 문학

현대 문학

요리.

살렌토와 칼라브리아의 전통요리는 그리코 문화의 영향을 많이 받았다. 그리코는 전통적으로 곡물, 채소, 올리브, 콩고물을 생산한다.[86] 현지 그리코 요리는 현지 이탈리아 인구와 크게 다르지 않지만, 지역적 편차가 있다. 그 중에는 아직도 전형적인 그리코 요리들이 많이 사용되고 있다. 그 중 일부는 아래에 언급되어 있다.

- 피트라와 레스토피타 - 보베시아 지방의 전통적인 그리스-칼라브리아 빵

- Ciceri e ttrìa - 병아리콩과 함께 제공되는 Tagliatelle의 한 형태. 전통적으로 이 요리는 3월 19일 그레시아 살렌티나에서 성 요셉의 잔치에 소비되었다.

- 크랜루 스톰파투 - 밀을 담가 두드리면서 간단한 방법으로 준비한 밀 요리

- 부자인 마카로니의 일종

- minchiolneddhi - 긴 마카로니의 일종

- Sagne ncannulate - 최대 0.5인치까지 넓은 태글리아텔

- 삼디 - 불규칙한 모양의 파스타, 특히 육수를 만드는데 사용된다.

- 멘둘라타 테 크랜루 - 파스티에라와 유사한 디저트, 크림 치즈, 꿀, 설탕, 바닐라로 가득 차 있다.

- Le Cuddhure - 그리스 쿨루리에서 부활절에 만든 전통적인 그리코 케이크

- 티아울릭치우 - 핫 칠리 피망은 그레시아 살렌티나 전역에서 광범위하게 먹으며, 마늘, 민트, 케이퍼의 슬리버를 첨가하여 보통 건조하거나 기름 항아리에 보존된다.

- Sceblasti - 그레시아 살렌티나 지역에서 빵을 만드는 전통적인 형태의 손이다.[86]

- 아구테 - 보베시아 지방의 전통적인 그리스-칼라브리아 부활절 빵으로 밀가루, 달걀, 버터를 혼합하여 준비하였고 표면은 그리스 투레키와 비슷하게 단단하게 삶은 계란으로 장식하였다.

- Scardeddhi - 작은 도넛 모양의 밀가루, 꿀, 아니스 씨앗으로 만든 전통적인 그리스-칼라브리아 혼례 과자. 그런 다음 끓는 물에 익힌 후, 제공되기 전에 흑설탕을 뿌린다.

살렌토의 그리코 요리에 관한 책이 출간되었는데, 제목은 그레시아 살렌티나 라 컬투라 가스트로노미카였다.[87] 그것은 남부 아풀리아의 그레시아 살렌티나 지역에 특화된 많은 전통적인 요리법을 특징으로 한다.

저명인사

- 교황 안테루스 (사망 236년)

- 교황 요한 7세 (c. 650–707)

- 교황 자차리 (679–752)

- 닐루스 1세 (910–1005)는 칼라브리아 로사노에 있는 그리스 집안에서 태어난 성인이다.

- 그리스계 존 16세(945–1001)는 칼라브리아의 로사노 출신이다.

- 세미나라 바르람 (1290–1348)은 14세기의 아리스토텔레스 학자와 성직자였다.

- 그리스 칼라브리아 학자인 레오니우스 필라투스(Ded 1366년 사망)는 서유럽에서 그리스 연구의 초기 발기인 중 한 명이었다.

- 안토니오 드 페라리스 (1444–1517), 아풀리아 갈라토네 출신의 그리스 학자, 학술자, 의사 및 휴머니스트.

- 세르지오 스티소(C. 1458~16세기)는 아풀리아 졸리노 출신의 인문주의자, 철학자, 신학자였다.

- 비토 도메니코 팔룸보(1854–1918), 작가 겸 시인.

- 도미니카노 톤디 (1885–1965)는 작가 겸 시인이다.

- 이탈리아계 미국인 가수인 토니 베넷(Tony Bennett, 1926년 8월 3일, 뉴욕)은 원래 친정 조상이 칼라브리아의 포다르고니 그리코 마을 출신이었던 대중음악, 표준, 쇼 튜닝, 재즈를 노래한 가수다.[88][89][90] 그의 조상들은 나중에 토니가 태어난 칼라브리아에서 미국으로 이주했다.

- 프랑코 콜리아노(그리코: 프란고스 코리아누스) (Calimera, 1948년 - 2015년 사망) 시인, 작곡가, 화가.

- 로코 압릴레(Rocco Aprile, 1929년 칼리메라 출생)는 2014년 칼리메라, 역사학자, 언어학자 등으로 세상을 떠났다.

- 에르네스토 압릴레(-2008), 과학자.

- 1974년 모델이자 배우인 도로타 머큐리

- 1821년 오페라 가수 엘레나 단그리

참고 항목

참조

- ^ "Unione dei comuni della Grecia Salentina - Grecia Salentina official site (in Italian)". www.comune.melpignano.le.it/melpignano-nella-grecia-salentina. Retrieved 2011-01-17.

La popolazione complessiva dell’Unione è di 54278 residenti così distribuiti (Dati Istat al 31° dicembre 2005. Comune Popolazione Calimera 7351 Carpignano Salentino 3868 Castrignano dei Greci 4164 Corigliano d'Otranto 5762 Cutrofiano 9250 Martano 9588 Martignano 1784 Melpignano 2234 Soleto 5551 Sternatia 2583 Zollino 2143 Totale 54278

- ^ Cfr. delibera della giunta comunale di Messina n. 339 del 27/04/2012 avente come oggetto: «Progetto "Mazì" finalizzato al mantenimento identità linguistica della comunità minoritaria greco-sicula sul terr. com. L.N. 482 del 15.12.99 a tutela delle minoranze linguistiche. 프로게토, 델라 스케줄라 식별자, 델라 오토커티 e delle schede al 4dro economico »

- ^ "Delimitazione ambito territoriale della minoranza linguistica greca di Messina" (PDF). Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- ^ Brisbane, Albert; Mellen, Abigail; Stallsmith, Allaire Brisbane (2005). The European travel diaries of Albert Brisbane, 1830-1832: discovering Fourierism for America. Edwin Mellen Press. p. 111. ISBN 9780773460706.

In Calabria there still exist people called Grecanici, who speak a dialect of Greek and practice the Orthodox Christian faith

- ^ F. 비올리, 레시코 그레카니코-이탈리아노-그레카니코, 아포디아파치, 레지오 칼라브리아, 1997.

- ^ 파올로 마르티노, 리솔라 그레카니카 델'아스프로몬테. 1980년 아스페티 사회언어학 1977년 리술타티 디 운친키에스타 델

- ^ 필리포 비올리, 스토리아 데글리 스터디 델라 레터타투라 포폴라레 그레카니카, C.S.E. Bova (RC), 1992년

- ^ 필리포는 콘스탄티, 그라마티카 그레카니카, 쿱을 비난한다. 1987년 레지오 칼라브리아 콘테자

- ^ Salento e Calabria le Voci deella minoranza languagea greccani, Il portale del safere.

- ^ Bornträger, Ekkehard W. (1999). Borders, ethnicity, and national self-determination. Braumüller. p. 16. ISBN 9783700312413.

…the process of socio-cultural alienation is still much further advanced those ethnic groups that are not (or only “symbolically”) protected. This also applies to the southern Italian Grecanici (ethnic Greeks), who at least cannot complain of any lack of linguistic publicity.

- ^ PARDO-DE-SANTAYANA, MANUEL; Pieroni, Andrea; Puri, Rajindra K. (2010). Ethnobotany in the new Europe: people, health, and wild plant resources. Berghahn Books. pp. 173–174. ISBN 9781845454562.

The ethnic Greek minorities living in southern Italy today exemplify the establishment of independent and permanent colonial settlements of Greeks in history.

- ^ a b Bekerman Zvi; Kopelowitz, Ezra (2008). Cultural education -- cultural sustainability: minority, diaspora, indigenous, and ethno-religious groups in multicultural societies. Routledge. p. 390. ISBN 9780805857245.

Griko Milume - This reaction was even more pronounced in the southern Italian communities of Greek origins. There are two distinct clusters, in Apulia and Calabria, which have managed to preserve their language, Griko or Grecanico, all through the historical events that have shaped Italy. While being Italian citizens, they are actually aware of their Greek roots and again the defense of their language is the key to their identity.

- ^ a b Danver, Steven L. (2015). Native Peoples of the World: An Encyclopedia of Groups, Cultures and Contemporary Issues. Routledge. p. 316. ISBN 9781317464006.

Some 46,000 ethnic Greeks in Italy are descendants of the Greek settlers that colonized Sicily and southern Italy up to the Gulf of Naples in antiquity. At that time, most of the Greek population lived in what is now Italian territory, in areas of settlement that were referred to as Magna Graecia or “Greater Greece.” Of the modern Greeks living in that region, only about one-third still speak Greek, while the rest have adopted Italian as their first language.

- ^ a b Hardy, Paula; Hole, Abigail; Pozzan, Olivia (2008). Puglia & Basilicata. Lonely Planet. pp. 153–154. ISBN 9781741790894.

THE GREEK SALENTINE – The Greek Salentine is a historical oddity, left over from a time when the Byzantine Empire controlled southern Italy and Greek culture was the order of the day. It is a cluster of nine towns – Calimera, Castrignano dei Greci, Corigliano d'Otranto, Martano, Martignano, Melpignano, Soleto, Sternatia and Zollino – in the heart of Terra d’Otranto. Why this pocket of Apulia has retained its Greek heritage is not altogether clear.

- ^ Commission of the European Communities, Istituto della Enciclopedia italiana (1986). Linguistic minorities in countries belonging to the European community: summary report. Commission of the European Communities. p. 87. ISBN 9789282558508.

In Italy, Greek (known locally as Griko) is spoken today in two small linguistic islands of southern Italy…The dialects of these two linguistic islands correspond for the most part, as regards morphology, phonetics, syntax and lexis to the neoclassical dialects of Greece, but they also present some interesting archaic characteristics. This has led to much discussion on the origins of the Greek-speaking community in southern Italy: according to some scholars (G. Morosi and C. Battisti), Greek in this area is not a direct continuation of the ancient Greek community but is due to Byzantine domination (535-1071); whereas for other scholars (Rohlfs, etc.), the Greek community of southern Italy is directly linked to the community of Magna Grecia.

- ^ Morosi, Giuseppe (1870). Sui dialetti greci della terra d'Otranto. Lecce: Editrice Salentina.

- ^ Douri De Santis (2015). "Griko and Modern Greek in Grecìa Salentina: an overview". Idomeneo. 19: 187–198.

- ^ Jaeger, Werner Wilhelm (1960). Scripta minora, Volume 2. Edizioni di storia e letteratura. p. 361. OCLC 311270347.

It began to dwindle in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries when the South became more and more Italianized and the Greek civilization of Calabria no longer found moral and political support in Constantinople and the Byzantine Empire.

- ^ a b Calcagno, Anne; Morris, Jan (2001). Travelers' Tales Italy: True Stories. Travelers' Tales. p. 319. ISBN 9781885211729.

Mass media has steadily eroded the Grecanico language and culture, which the Italian government — despite Article 6 of the Italian Constitution that mandates the preservation of ethnic minorities — does little to protect.

- ^ a b c Moseley, Christopher (2007). Encyclopedia of the world's endangered languages. Routledge. p. 248. ISBN 9780700711970.

Griko (also called Italiot Greek) Italy: spoken in the Salento peninsula in Lecce Province in southern Apulia and in a few villages near Reggio di Calabria in southern Calabria. Griko is an outlying dialect of Greek largely deriving from Byzantine times. The Salentine dialect is still used relatively widely, and there may be a few child speakers, but a shift to South Italian has proceeded rapidly, and active speakers tend to be over fifty years old. The Calabrian dialect is only used more actively in the village of Gaddhiciano, but even there youngest speakers are over thirty years old. The number of speakers lies in the range of 20,000. South Italian influence has been strong for a long time. Severely Endangered.

- ^ 사프란, 엘. 중세 살렌토: 2014년 215페이지의 남이탈리아의 예술과 정체성

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Marcato, Gianna (2008). L'Italia dei dialetti: atti del convegno, Sappada/ Plodn (Belluno), 27 giugno-1 luglio 2007. Unipress. p. 299. ISBN 9788880982425.

L’enclave greco-calabra si estende sul territorio aspromontano della provincia di Reggio; Condofuri, Amendolea, Gallicianò, Roccaforte e il suo Chorìo, Rochudi e il suo Chorio, Bova sono i comuni della valle dell 'Amendolea, a ridosso dello stretto di Messina, la cui parlata greca, insieme a quella di Cardeto, è stata documentata a partire dal XIX secolo. Con la legge 482 del 1999, il territorio della minoranza storica si allarga a Bova Marina, Palizzi, San Lorenzo, Melito Porto Salvo, Staiti, Samo, Montebello Jonico, Bagaladi, Motta San Giovanni, Brancaleone, alla stessa città di Reggio; di queste comunità non si possiede, circa l'alloglossia, alcun dato, Per quel che riguarda l’enclave tradizionale, invece, la varieta e ormai uscita fuori dall’uso comunitario ovunque; gli studi linguistici condotti sull’area ne segnalano la progressive dismissione gia a partire dagli anni ’50. Oggi non ai puo sentire parlare in Greco che su richiesta; il dialetto romanzo e il mezzo di comunicazzione abituale.

- ^ Cazzato, Mario; Costantini, Antonio (1996). Grecia Salentina: Arte, Cultura e Territorio. Congedo Editore. p. 313. ISBN 88-8086-118-2.

Estensione della lingua greca verso la fine del secolo XVIII

- ^ a b The Academy, Volume 4. J. Murray - Princeton University. 1873. p. 198.

... Greek was also heard at Melpignano, Curse, Caprarica, Cannole, Cutrofiano, and at a more remote period at Galatina.

- ^ a b c Cazzato, Mario; Costantini, Antonio (1996). Grecia Salentina: Arte, Cultura e Territorio. Congedo Editore. p. 34. ISBN 88-8086-118-2.

49. Variazione territoriale della Grecía Salentina (da B. Spano)

- ^ Loud, G. A.; Metcalfe, Alex (2002). The society of Norman Italy. BRILL. pp. 215–216. ISBN 9789004125414.

In Calabria, a Greek-speaking population existed in Aspromonte (even until recently, a small Greek-language community survived around Bova) and, even in the thirteenth century, this extended into the plain beyond Aspromonte and into present provinces of Catanzaro and Cosenza.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Lüdtke, Karen (2009). Dances with spiders: crisis, celebrity and celebration in southern Italy. Berghahn Books. p. 118. ISBN 9781845454456.

The towns of the Grecia Salentina include: Calimera, Carpignano Salentino, Castrignano dei Greci, Corigliano d'Otranto, Cutrofiano, Martano, Martignano, Melpignano, Soleto, Sternatia and Zollino.

- ^ a b c Philological Society (Great Britain) (1968). Transactions of the Philological Society. Published for the Society by B. Blackwell. p. 493. OCLC 185468004.

In the following thirteen villages of the province of Terra d’Otranto, all belonging to the diocese of the same name, viz. Martano, Calimera, Sternatia, Martignano, Melpignano, Castrigliano, Coregliano, Soleto, Zollino, Cutrofiano, Cursi, Caprarica, and Cannole, no Albanian is heard, as has been erroneously stated, but only modern Greek, in a corrupted dialect, which, as well as the Greek of Calabria Ulteriore I., has been scientifically treated by Comparetti, by Pellegrini, and especially by Morosi.

- ^ a b 프랑코 콜리아누: 그리코-이탈리아노 이탈리아노-그리코, 보카볼라리오. 산체사리오디레체2010

- ^ a b 돈 마우로 카소니: 그리코이탈리아노, 보카볼라리오. 레체 1999

- ^ a b Commission of the European Communities, Istituto della Enciclopedia italiana (1986). Linguistic minorities in countries belonging to the European community: summary report. Commission of the European Communities. p. 87. ISBN 9789282558508.

In Italy, Greek (known locally as Griko) is spoken today in two small linguistic islands of southern Italy: (a) in Puglia, in Calimera, Castrignano dei Greci, Corigliano d’Otranto, Martano, Martignano, Melpignano, Solato, Sternatia and Zolino (covering a total area of approximately 144 square kilometers… Outside this area it appears that Greek was also spoken at Taviano and Alliste, in Puglia (cf. Rohlfs). The dialects of these two linguistic islands correspond for the most part, as regards morphology, phonetics, syntax and lexis to the neoclassical dialects of Greece, but they also present some interesting archaic characteristics.

- ^ a b c d e f g h L'Italia dialettale (1976). L'Italia dialettale, Volume 39. Arti Grafiche Pacini Mariotti. p. 250.

Dialetto romanzi, in centric he circondano, senza allontanarsene troppo, l’area ellenofona, cioè Melpignano (dove il dialetto griko non è ancor del tutto morto), Vernole, Lecce, S. Cesario di Lecce, Squinzano, San Pietro vernotico, Cellino S. Marco, Manduria, Francavilla Fontana, Maruggio: può essere perciò legittimo pensare ad un'origine grika del verbo in questione, con estensione successiva al dialetti romani. Il neogreco presenta una serie di voci che si prestano semanticamente e foneticamente

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Stamuli, Maria Francesca (2008). Morte di lingua e variazione lessicale nel greco di Calabria. Tre profili dalla Bovesìa (PDF). www.fedoa.unina.it/3394/. p. 12. OCLC 499021399.

Calabria meridonale - zona di lingua greca - Figura 1. L’enclave greco-calabra così come rappresentata da Rohlfs (1972: 238) - Armo Cataforio Laganadi Lubrichi Mosorrofa Paracorio Pedovoli San. Giorgio Scido Sitizzano

- ^ Bellinello, Pier Francesco (1998). Minoranze etniche e linguistiche. Bios. p. 53. ISBN 9788877401212.

Bova Superiore, detta Vua (Βοῦα) opp. i Chora (ἡ Χώρα «il Paese»), 827 m.s.m., già sede vescovile, Capoluogo di Mandamento e sede di Pretura

- ^ a b Comparetti, Domenico (1866). Saggi dei dialetti greci dell' Italia meridionale. Fratelli Nistri, Oxford University. p. vii-viii.

I dialetti greci dei quali qui diamo alcuni saggi sono parlati nelle due punte estreme del continente italiano meridionale, in Calabria cioè ed in Terra d'Otranto. Bova è il principale dei paesi greci situati nei dintorni di Reggio in Calabria; altri sono Amendolea, Galliciano, Eoccaforte, Eogudi, Condofuri, S.la Caterina, Cardeto. Oltre a questi, molti altri paesi della stessa provincia sono abitati da gente di origine greca e che fino a qualche tempo fa ha parlato greco, ma ora parla italiano. Corigliano, Martano e Calimera sono paesi greci del Leccese in Terra di Otranto, ove greci sono pure Martignano, Zollino, Sternazia, Soleto, Castrignano de' Greci.

- ^ a b c d Stamuli, Maria Francesca (2008). Morte di lingua e variazione lessicale nel greco di Calabria. Tre profili dalla Bovesìa (PDF). www.fedoa.unina.it/3394/. pp. 13–14. OCLC 499021399.

Nel 1929, quando la consistenza dell’enclave fu descritta e documentata linguisticamente da Rohlfs, il territorio di insediamento della minoranza grecocalabra comprendeva le comunità di Roccaforte del Greco (Vunì) e Ghorìo di Roccaforte, Condofuri, con Amendolea e Gallicianò e, più a est, Roghudi, Ghorìo di Roghudi e Bova (cfr. Figura 1). Questi paesi costituiscono l’‘enclave storica’ del greco di Calabria, intendendo con quest’accezione quell’area geografica unitaria documentata come alloglotta mediante dati linguistici raccolti sul campo a partire dalla fine dell’Ottocento. Le comunità ‘storicamente’ grecofone si arroccano a ferro di cavallo sui rilievi dell’Aspromonte occidentale, intorno alla fiumara dell’Amendolea, tra gli 820 metri di altitudine di Bova e i 358 di Amendolea. Esse si affacciano con orientamento sud-orientale sul lembo di Mar Ionio compreso tra Capo Spartivento e Capo dell’Armi, meridione estremo dell’Italia continentale (cfr. Figura 2). Un secolo prima, all’epoca del viaggio di Witte, erano ancora grecofoni anche molti paesi delle valli a occidente dell’Amendolea: Montebello, Campo di Amendolea, S. Pantaleone e il suo Ghorìo, San Lorenzo, Pentadattilo e Cardeto. Quest’ultimo è l’unico, tra i paesi citati da Witte, in cui nel 1873 Morosi potè ascoltare ancora pochi vecchi parlare la locale varietà greca. La descrizione che lo studioso fornisce di questa lingua in Il dialetto romaico di Cardeto costituisce la principale fonte oggi esistente per forme linguistiche di una varietà greco-calabra non afferente al bovese

- ^ Bellinello, Pier Francesco (1998). Minoranze etniche e linguistiche. Bios. p. 54. ISBN 9788877401212.

Condofuri o Condochòri (Κοντοχώρι «vicino al paese»), 350 m.s.m., comune autonomo dal 1906, era precedentemente casale di Amendolea to Chorìo)…

- ^ Touring club italiano (1980). Basilicata Calabria. Touring Editore. p. 652. ISBN 9788836500215.

Podàrgoni m 580, ove si conserva un tipo etnico greco inalterato;

- ^ Bradshaw, George (1898). Bradshaw's illustrated hand-book to Italy. p. 272.

At the head of the river, at Polistena, a Greek village, a tract of land was moved across a ravine, with hundreds of houses upon it; some of the residents Of which were unhurt; but 2000 out of a population of 6000 were killed.

- ^ Bellinello, Pier Francesco (1998). Minoranze etniche e linguistiche. Bios. p. 54. ISBN 9788877401212.

Roccaforte del Greco, detta Vunì (Βουνί «montagna»), adagiata sul pendìo di uno sperone roccioso che raggiunge i 935 m.s.m.,

- ^ Bellinello, Pier Francesco (1998). Minoranze etniche e linguistiche. Bios. p. 54. ISBN 9788877401212.

Roghudi o Richudi (ῥηχώδης «roccioso») ha 1700 ab. circa cosi distribuiti…

- ^ The Melbourne review. Oxford University. 1883. p. 6.

My particular object, however, in writing this paper has been to call attention to the fact that there are in certain districts of Italy, even now, certain Greek dialects surviving as spoken language. These are found, at the present day, in the two most southerly points of Italy, in Calabria and in the district of Otranto. The names of the modern Greek-speaking towns are Bova, Amendolea, Galliciano, Roccaforte, Rogudi, Condofuri, Santa Caterina, Cardeto

- ^ Principe, Ilario (2001). ittà nuove in Calabria nel tardo Settecento: allegato : Atlante della Calabria. Gangemi. p. 400. ISBN 9788849200492.

La sua valle, cominciando dalle alture di Sinopoli greco, fino alle parti sottoposte all'eminenza di S. Brunello per una

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Murray, John (1890). A Handbook for Travellers in Southern Italy and Sicily Volume 1. p. 281.

The high road beyond Monteleone to Mileto and Rosarno proceeds through a country called La Piana di Monteleone, having on each side numerous villages whose names bear unmistakable evidence of their Greek origin ... Among these may be mentioned Orsigliadi, lonadi, Triparni, Papaglionti, Filandari, on the rt. of the road ; and on the 1. beyond the Mesima, Stefanoconi, Paravati, lerocame, Potame, Dinami, Melicuca, Garopoli, and Calimera. Most of these colonies retain their dress, language, and national customs, but not their religion.

- ^ 1999년 법률 제482호: "La Republica tutela la la cultura e la cultura delle popolazioni albanesi, catalane, 게르마니체, greche, slovene e croate e di quelle parlanti il francese, Ilante, Ilante, Ilante, Ilante, Ilanzale, Ilanzale, Ilanzale.

- ^ Gert Jan van Bijngaarden, Levant, Kyprofess and Italia (기원전 1600년-1200년)에 있는 Mycenaean 도자기의 사용 및 감사: 문맥의 중요성, 암스테르담 고고학, 2001년 암스테르담 대학 출판부

- ^ 엘리자베스 A. 피셔, 미케네인, 아풀리아. 1998년 아스트롬주 동부 마그나 그레시아에서 아풀리아와 접촉한 에게 청동기 연구

- ^ 데이비드 리드웨이, 최초의 서양 그리스인, 케임브리지 대학 출판부, 1993년

- ^ 2004년 맥팔랜드 미케네 문명 브라이언 에이버리 푸어

- ^ a b Michael J. Bennett; Aaron J. Paul; Mario Iozzo; Bruce M. White; Cleveland Museum of Art; Tampa Museum of Art (2002). Magna Graecia: Greek art from south Italy and Sicily. Hudson Hills. ISBN 9780940717718.

The Greek colonization of South Italy and Sicily beginning in the eighth century BC was a watershed event that profoundly informed Etruscan and Roman culture, and is reflected in the Italian Renaissance.

In the sixth century BC, Pythagoras established a large community in Krotone (modern Croton) and Pythagorean communities spread throughout Graecia Magna during the next centuries, including at Taras (Tarentum), Metapontum and Herakleion.

So dense was the constellation of Greek city-states there during the Classical period and so agriculturally rich were the lands they occupied that the region came to be called Magna Graecia (Great Greece). - ^ T. S. Brown, "7세기 라벤나 교회와 제국행정", 영어사적평론(1979 페이지 1-28) 페이지 5.

- ^ a b Browning, Robert (1983). Medieval and modern Greek. Cambridge University Press. pp. 131–132. ISBN 9780521299787.

There are now only two tiny enclaves of Greek speech in southern Italy. A few centuries ago their extent was much greater. Still earlier one hears of Greek being currently spoken in many parts of south Italy. Now it is clear that there was a considerable immigration from Greece during Byzantine times. We hear of refugees from the rule of Iconoclast emperors of the eighth century … as well as of fugitives from the western Peloponnese and elsewhere during the Avar and Slav invasions of the late sixth and seventh centuries. And during the Byzantine reconquest of the late ninth and tenth centuries there was a good deal of settlement by Greeks from other regions of the empire on lands taken from the Arabs, or occasionally from the Lombards. … It is now clear, above all from the researches of Rohlfs and Caratzas, that the speech of these enclaves is the descendant, not of the language of Byzantine immigrants, but of the Greek colonists of Magna Graecia. In other words Greek never died out entirely in south Italy, though the area in which it was spoken was greatly reduced by the advance of Latin. When the Byzantne immigrants arrived they found a Greek-speaking peasantry still settled on the land in some areas, whose speech was an independent development of the vernacular of Magna Graecia in the late Roman empire, no doubt a regional variety of Koine with a heavy dialect colouring. Only by this hypothesis can the presence of so many archaic features not found in any other Greek dialect be explained. And there is nothing inconsistent with it in the meager historical record. Here we have a Greek-speaking community isolated from the rest of the Hellenic world virtually since the death of Theodosius in 395, with a brief reintegration between Justinian’s reconquest and the growth of Lombard and Arab power, and again during the Byzantine reoccupation in the tenth and eleventh centuries, and always remote from the centers of power and culture. There were the conditions which gave rise to the archaic and aberrant Greek dialects of the now bilingual inhabitants of the two enclaves in the toe and heel of Italy.

- ^ Oldfield, Paul (2014). Sanctity and Pilgrimage in Medieval Southern Italy, 1000-1200. Cambridge University Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-1-107-00028-5.

“However, the Byzantine revival of the tenth century generated a concomitant process Hellenization, while Muslim raids in southern Calabria, and instability in Sicily, may also have displaced Greek Christians further north on the mainland. Consequently, zones in northern Calabria, Lucania and central Apulia which were reintegrated into Byzantine control also experienced demographic shifts, and the increasing establishment of immigrant Greek communities. These zones also acted as springboards for Greek migration further north, into regions such as the Cilento and areas around Salerno, which had never been under Byzantine control.

- ^ a b Kleinhenz, Christopher (2004). Medieval Italy: an encyclopedia, Volume 1. Routledge. pp. 444–445. ISBN 978-0-415-93930-0.

ISBN 0-415-93930-5" "In Lucania (northern Calabria, Basilicata, and southernmost portion of today's Campania) ... From the late ninth century into the eleventh, Greek-speaking populations and Byzantine temporal power advanced, in stages but by no means always in tandem, out of southern Calabria and the lower Salentine peninsula across Lucania and through much of Apulia as well. By the early eleventh century, Greek settlement had radiated northward and had reached the interior of the Cilento, deep in Salernitan territory. Parts of the central and north-western Salento, recovered early, came to have a Greek majority through immigration, as did parts of Lucania.

- ^ Eisner, Robert (1993). Travelers to an Antique Land: The History and Literature of Travel to Greece. University of Michigan Press. p. 46. ISBN 9780472082209.

The ancient Greek colonies from Naples south had been completely latinized, but from the fifth century AD onward Greeks had once again emigrated there when pressed out of their homeland by invasions. This Greek culture of South Italy was known in medieval England because of England’s ties to the Norman masters of Sicily. Large parts of Calabria, Lucania, Apulia, and Sicily were still Greek-speaking at the end of the Middle Ages. Even nineteenth-century travelers in Calabria reported finding Greek villages where they could make themselves understood with the modern language, and a few such enclaves are said to survive still.

- ^ a b Vasil’ev, Aleksandr Aleksandrovich (1971). History of the Byzantine Empire. 2, Volume 2. Univ of Wisconsin Press. p. 718. ISBN 9780299809263.

half of the thirteenth century Roger Bacon wrote the Pope concerning Italy, “in which, in many places, the clergy and the people were purely Greek.” An old French chronicler stated of the same time that the peasants of Calabria spoke nothing but Greek.

- ^ Commission of the European Communities, Istituto della Enciclopedia italiana (1986). Linguistic minorities in countries belonging to the European community: summary report. Commission of the European Communities. p. 87. ISBN 9789282558508.

In Italy, Greek (known locally as Griko) is spoken today in two small linguistic islands of southern Italy…In former times, the two areas were much larger: in the 16th century, the Greek area in Calabria took in about 25 villages, while in Puglia Greek was spoken in the 15th century covering the whole Salento coastal strip between Mardo and Gallipoli in the west up to the edge of Malendugno-Otranto in the east. Outside this area it appears that Greek was also spoken at Taviano and Alliste, in Puglia (cf. Rohlfs).

- ^ Loud, G. A. (2007). The Latin Church in Norman Italy. Cambridge University Press. p. 494. ISBN 9780521255516.

At the end of the twelfth century…While in Apulia Greeks were in a majority – and indeed present in any numbers at all – only in the Salento peninsula in the extreme south, at the time of the conquest they had an overwhelming preponderance in Lucaina and central and southern Calabria, as well as comprising anything up to a third of the population of Sicily, concentrated especially in the north-east of the island, the Val Demone.

- ^ Oldfield, Paul (2014). Sanctity and Pilgrimage in Medieval Southern Italy, 1000-1200. Cambridge University Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-1-107-00028-5.

“However, the Byzantine revival of the tenth century generated a concomitant process Hellenization, while Muslim raids in southern Calabria, and instability in Sicily, may also have displaced Greek Christians further north on the mainland. Consequently, zones in northern Calabria, Lucania and central Apulia which were reintegrated into Byzantine control also experienced demographic shifts, and the increasing establishment of immigrant Greek communities. These zones also acted as springboards for Greek migration further north, into regions such as the Cilento and areas around Salerno, which had never been under Byzantine control.

- ^ Horrocks, Geoffrey (2010). Greek: A History of the Language and Its Speakers. John Wiley and Sons. p. 389. ISBN 9781405134156.

None the less, the severing of the political connection with the empire after 1071…the spread of Catholicism, led to the gradual decline of Greek language and culture, and to autonomous dialectical development as areas of Greek speech were reduced to isolated enclaves…the Orthodox church retained adherents in both Calabria and Apulia into the early 17th century.

- ^ Weiss, Roberto (1977). Medieval and Humanist Greek. Antenore. pp. 14–16.

The zones of south Italy in which Greek was spoken during the later Middle Ages, were eventually to shrink more and more during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Some small areas were, however, able to remain Greek even after the Renaissance period. In Calabria, for instance, Greek may till be heard today at Bova, Condofuri, Roccaforte, Roghudi, and in a few isolated farms here and there. One hundred years ago, it was still spoken also at Cardeto, Montebello, and San Pantaleone; and the more we recede in time the larger are these areas. And what took place in Calabria happened also in Apulia, where many places which were still Greek-speaking as late as 1807 are now no longer so. The use of the Greek language in such areas during the later Middle Ages is shown by..

- ^ Golino, Carlo Luigi; University of California, Los Angeles. Dept. of Italian ; Dante Alighieri Society of Los Angeles ; University of Massachusetts Boston (1989). Italian quarterly, Volume 30. Italian quarterly. p. 5. OCLC 1754054.

(Antonio de Ferrariis detto Galateo) He was born in Galatone in 1448 and was himself of Greek extraction - a fact that he always brought to light with singular pride.

CS1 maint: 여러 이름: 작성자 목록(링크) - ^ Vakalopoulos, Apostolos Euangelou (1976). The Greek nation, 1453-1669: the cultural and economic background of modern Greek society. Rutgers University Press. p. 48. ISBN 9780813508108.

During the fifteenth century, for example, Antonio Galateo, an eminent physician of Greek descent, who spoke Greek fluently and had a sound Greek education, described the inhabitants of Kallipoli as still conversing in their original mother tongue

- ^ Rawson, Elizabeth (1991). The Spartan tradition in European thought. Oxford University Press. p. 174. ISBN 0-19-814733-3.

Antonio de Ferraris, known as Il Galateo, spent his last years in the little Apulian town of Gallipoli, not far from what every reader of Latin poetry knew as “Lacedaemonian’ Tarentum, now Taranto. Il Galateo was a humanist, proud of the Greek traditions of his province and his own family. In the endearing description he gives of his life at Gallipoli he claims to feel himself there in Sparta or Plato’s Republic: ‘sentio enim hic aliquid Graecanicum.’…After all, he reflects, the population is probably of Lacedaemonian stock.

- ^ Journalists in Europe (2001). "Europ, Issues 101-106". Europ. Hors Série. Journalists in Europe: 30. ISSN 0180-7897. OCLC 633918127.

"We grew up listening to Griko, especially from our grand-parents. Our parents stopped speaking the dialect when we started going to school. They were afraid that it would be an obstacle to our progress," says Luigino Sergio. 55 years, former mayor of Martignano and now a senior local government administrator in Lecce. "It is the fault of the Italian government. In the 1960s they were speaking Griko in all the houses. Now, only 10 per cent speak it. The Italian government tried to impose the Italian language everywhere as the only formal one. But Griko was not only a language. It was also a way of living. Griki hâve their own traditions and customs. Musical groups tried to keep them as a part of our identity but when the language disappears, the same happens with the culture

- ^ Smith, George (1881). The Cornhill magazine, Volume 44. Smith, Elder. p. 726.

We are not ashamed of our race, Greeks we are, and we glory in it," wrote De Ferrariis, a Greek born at Galatone in 1444, and the words would be warmly endorsed by the enlightened citizens of Bova and Ammendolea, who quarrel as to which of the two places gave birth to Praxiteles.

- ^ Martinengo-Cesaresco, Countess Evelyn (2006). Essays in the Study of Folk-Songs. Kessinger Publishing. p. 154. ISBN 1-4286-2639-5.

The Greeks of Southern Italy have always had their share of a like feeling. "We are not ashamed of our race, Greeks we are and we glory in it," wrote De Ferrariis, a Greek born at Galatone in 1444

- ^ Ashworth, Georgina (1980). World minorities in the eighties. Quartermaine House. p. 92. ISBN 9780905898117.

Vito Domenico Palumbo (1854–1918), one of the participants in the Greek Renaissance. Since 1955 cultural contacts have been renewed with Greece and two magazines have been published for the promotion of Greek culture in Italy

- ^ "Encardia - The Dancing Stone". Utopolis: movies, moments and more. Retrieved 31 December 2016.

- ^ Tsatsou, Marianna (April 22, 2012). "Charity Concert Collects Medicine and Milk Instead of Selling Tickets". Greek Reporter. Retrieved 31 December 2016.

- ^ a b Penzl, Herbert; Rauch, Irmengard; Carr, Gerald F. (1979). Linguistic method: essays in honor of Herbert Penzl. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co. KG. p. 83. ISBN 978-9-027-97767-0.

It is difficult to state, particularly on lexical grounds, to what degree the so-called Graecanic speech of Southern Italy, which survived far into the Middle Ages and, greatly reduced, even into our times, preserves features from the koine (the colloquial Greek of late Antiquity) and to what degree its Hellenism is due to Byzantinization.

- ^ Horrocks, Geoffrey (2010). Greek: A History of the Language and Its Speakers. Wiley. pp. 381–383. ISBN 978-1-405-13415-6.

14.2 The Spoken Dialects of Modern Greek... South Italian, surviving residually in isolated villages of Apulia and Calabria, apparently with many archaisms preserved from the ancient speech of Magna Graecia, despite Byzantine overlays.

- ^ Horrocks, Geoffrey (2010). Greek: A History of the Language and Its Speakers. Wiley. p. 389. ISBN 978-1-405-13415-6.

Greek still remains in use in two remote and geographically separate areas, the mountainous Aspromonte region at the tip of Calabria, and the fertile Otranto peninsula south of Lecce in Puglia. The position of Greek in Calabria is now perilous (c. 500 native speakers in the traditional villages, all ealderly, though there are Greek-speaking communities of migrants in Reggio); in Puglia, by contrast, ‘Grico’ survives more strongly (c. 20,000 speakers) and there are even efforts at revival. The principal interest of these varieties, apart from providing observable examples of the process of ‘language death’, is that they have preserved a number of archaic features, including elements which were once widespread in medieval Greek before falling out of mainstream use.

- ^ Murzaku, Ines Angjeli (2009). Returning Home to Rome: The Basilian Monks of Grottaferrata in Albania. Analekta Kryptoferris. p. 34. ISBN 978-8-889-34504-7.

In southern Calabria, as linguistic evidence shows, the originally Greek-speaking population had been Romanized only in the Middle Ages; indeed, Greek elements consistent with pre-Roman origin in Magna Graecia, such as lexical and phonetic relics consistent with Doric rather than with Attic origin, survived.

- ^ Coletti, Alessandro (1995). Mafie: storia della criminalità organizzata nel Mezzogiorno. SEI. p. 28. ISBN 9788805023738.

Non è facile comunque rintracciare allo stato attuale degli studi, le vicende iniziali di quella che più tardi verrà chiamata 'ndrangheta. Il termine deriva dal dialetto grecanico, dove l'"andragathos", — o '"ndranghitu" secondo la forma fonetica innovata — designa l'individuo valido e coraggioso.

- ^ 줄리아노 투로네, 일 델리토 디 아소니아지오네 마피아오사, 밀라노, 기우프레 에디토레, 2008, 페이지 87.

- ^ 뮬러, 톰: 실화(여행자의 이야기 가이드)-여행자의 이야기 이탈리아, 앤 칼카그노(편집자), 얀 모리스(소개자): p.319 ISBN 9781885211729, pub. 2001년 10월 25일에 접속.

- ^ Murzaku, Ines Angeli (2009). Returning home to Rome: the Basilian monks of Grottaferrata in Albania. Analekta Kryptoferris. p. 47. ISBN 9788889345047.

Rossano, a town in southern Italy, which is probably the birthplace of another well-known Greek figure, Pope John VII who reigned in the See of St. Peter for two years (705-707)

- ^ "John (XVI) (antipope [997-998]". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 10 February 2011.

John (XVI), original name Giovanni Filagato, Latin Johannes Philagathus (b. , Rossano, Calabria – d. Aug. 26, 1001), antipope from 997 to 998. A monk of Greek descent whom the Holy Roman emperor Otto II named abbot of the monastery of Nonantola, Italy, he attained an influential position at the court of Otto’s widow, the empress Theophano.

- ^ Zchomelidse, Nino (2014). Art, Ritual, and Civic Identity in Medieval Southern Italy. Nino M. Zchomelidse. ISBN 978-0-271-05973-0.

- ^ Hardy, Paula; Abigail Hole; Olivia Pozzan (2008). Puglia & Basilicata. Lonely Planet. pp. 153–154. ISBN 9781741790894.

Although Bari, the last Byzantine outpost, fell to the Normans in 1071, the Normans took a fairly laissez-fair attitude to the Latinisation of Puglia..

- ^ Loud, G. A. (2007). The Latin Church in Norman Italy. Cambridge University Press. pp. 126–127. ISBN 9780521255516.

Certainly Roger's attempt to install a Latin archbishop on the overwhelmingly Greek population at Rossano in 1093 was a complete failure. His nominee waited a year without receiving consecration, seemingly because of local opposition, and then, needing the support of the inhabitants against a rebellious Norman baron, the duke backed down and allowed the election of a Greek archbishop.

- ^ Levillain, Philippe (2002). The Papacy: Gaius-Proxies. Routledge. pp. 638–639. ISBN 9780415922302.

Latin bishops replaced Greeks in most sees, with the exception of Bova, Gerace, and Oppido. The Greek rite was practiced until 1537 in the Bova cathedral and until the 13th century in Santa Severina. In Rossano, in 1093, a riot kept a Latin bishop from being installed, and the see remained Greek until 1460. In Gallipoli, a Latinization attempt also failed in the early 12th century, and that see was occupied by Greeks until the 1370s. The Greek rite was practiced in Salento until the 17th century.

- ^ a b Hardy, Paula; Hole, Abigail; Pozzan, Olivia (2008). Puglia & Basilicata. Lonely Planet. pp. 153–154. ISBN 9781741790894.

- ^ Journalists in Europe (2001). "Europ, Issues 101-106". Europ. Hors Série. Journalists in Europe: 29–30. ISSN 0180-7897. OCLC 633918127.

Graecanic,” says (in very good modern Greek) the architect Mimo Nucera, one of the 100 inhabitants of the village of Galliciano…Does he feel more Italian or Greek? "Our roots are Greek but we are in Italy. Our blood is Greek but we are Grecanici," says Nucera, who is also a teacher of Calabrian Greek and one of the architects of the cultural exchange between Greece and the Greek-speaking territory.

- ^ a b Madre, Terra (2007). Terra Madre: 1,600 Food Communities. Slow Food Editore. p. 381. ISBN 9788884991188.

Greek-speaking people (who speak griko, a dialect of Greek origin). There is a community of producers of cereals, vegetables, legumes and olives, and bread-makers who still make a traditional type of bread by hand called sceblasti.

- ^ Grecia Salentina la Cultura Gastronomica. Manni Editori. 2001. ISBN 9788881768486.

- ^ a b Evanier, David (2011). All the Things You Are: The Life of Tony Bennett. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 19–20. ISBN 9781118033548.

Tony Bennett's paternal grandfather, Giovanni Benedetto, grew up in the village of Podargoni, above Reggio Calabria. The family were poor farmers, producing figs, olive oil, and wine grapes. His mother’s family, the Suracis, also farmed in Calabria. Neither side of the family could read or write.

- ^ Touring club italiano (1980). Basilicata Calabria. Touring Editore. p. 652. ISBN 9788836500215.

Podàrgoni m 580, ove si conserva un tipo etnico greco inalterato;(translated; Podargoni 580 m, where it has preserved an unaltered ethnic Greek character)

- ^ Touring club italiano (1937). Puglia, Lucania, Calabria. Touring Club Italiano. p. 232. OCLC 3438860.

Podàrgoni è un grazioso paesetto lungo la strada da Reggio a Cambàrie e ai piani d'Aspromonte, i cui abitanti conservano il tipo etnico greco abbastanza puro. (translation: Podargoni is a charming little village on the road from Reggio to Cambàrie and plans Aspromonte, whose inhabitants retain their ethnic greek pure enough.)

원천

- 스타브룰라 피피루 남이탈리아의 그레카니치: 통치, 폭력, 소수 정치. 필라델피아: 2016년 펜실베니아 대학 출판부. ISBN 978-0-8122-4830-2

외부 링크

- 에노시 그리코, 그레차 살렌티나 협회 조정

- Mi mu couddise pedimmo ("Don't critt me, my son")는 그리코어로 현지인이 연주한 노래다.

- 프랑코 스탕구리아, 로 "쉬아쿠디" 두 개의 연극이 초리아나(Corigliano d'Otranto)의 지역 그리스 사투리로 공연되었다.

- 안드라 mou paei는 프랑코 콜리아노의 이민에 관한 유명한 그리코 노래로, 엔카르디아가 공연한 현대 그리스어 번역으로 유명하다. 이 노래의 전체 제목은 "오 클라마 지네카 유 이민자"이지만, 일반적으로 제목은 "클라마"로 줄여서 "안드라마 파이" ("남편이 떠난다")로 널리 알려져 있다.

- 팔라이자 2009 보바 그리코 디 칼라브리아