그레이트 퍼시픽 쓰레기장

Great Pacific garbage patch그레이트 태평양 쓰레기 지역(또한 태평양 쓰레기 소용돌이)은 북태평양 중부에 있는 해양 파편 입자의 소용돌이인 쓰레기 지역입니다.위치는 대략 135°W~155°W, 35°N~42°[1]N입니다.플라스틱과 부유식 쓰레기의 수집은 아시아, 북미,[2] 남아메리카의 국가들을 포함한 환태평양 지역에서 유래했다.이 순환은 캘리포니아에서 하와이로 가는 '동부 쓰레기 매립지'와 하와이에서 일본까지 이어지는 '서부 쓰레기 매립지'의 두 지역으로 나뉜다.거대한 부유 쓰레기의 섬으로 존재하는 이 지역에 대한 일반 대중의 인식에도 불구하고, 이 지역의 낮은 밀도(입방미터당 4개의 입자(3.1/cu yd)는 위성 사진이나 심지어 그 지역의 평범한 보트 타자나 잠수부들에 의한 탐지를 방해한다.이는 패치가 주로 미세 [3]플라스틱으로 알려진 상부 물기둥에 떠 있는 "손톱 크기 또는 더 작은" 입자들로 구성된 널리 분산된 영역이기 때문입니다.The Ocean Cleanup 프로젝트의 연구원들은 그 지역이 160만 평방 킬로미터에 이른다고 주장했다.[4]패치의 플라스틱 중 일부는 50년 이상 된 것으로 플라스틱 라이터, 칫솔, 물병, 펜, 젖병, 휴대전화, 비닐봉투, 누들 등의 품목(및 품목 조각)을 포함하고 있다.이 지역에서 발견된 나무 펄프의 작은 섬유들은 "매일 [3]수천 톤의 화장지가 바다로 흘러들어간 것으로 믿어지고 있다."

조사 결과 패치가 빠르게 [5]축적되고 있는 것으로 나타났습니다.이 [6]지역은 1945년 이후 "10년마다 10배" 증가한 것으로 알려져 있다.텍사스의 두 배 크기로 추정되는 이 지역에는 300만 숏톤([7]270만 미터톤) 이상의 플라스틱이 매장돼 있다.이 환에는 [8]플랑크톤 1파운드 당 약 6파운드의 플라스틱이 들어 있습니다.북대서양 [9][10]쓰레기장이라고 불리는 떠다니는 플라스틱 파편들이 대서양에서 발견됩니다.이 성장하는 부분은 해양 생태계와 어종에 다른 환경 파괴에 기여한다.

역사

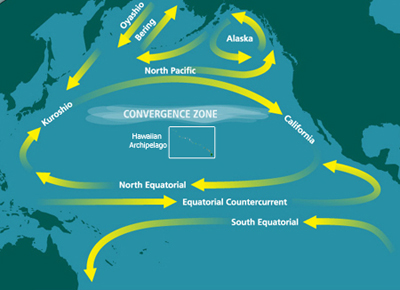

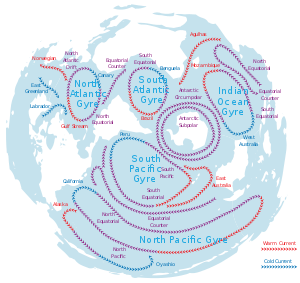

이 패치는 미국해양대기청(NOAA)이 발행한 1988년 논문에 기술되었다.이 기술은 1988년 알래스카에 기반을 둔 몇몇 연구원들이 북태평양에서 [11]네스토닉 플라스틱을 측정한 연구에 바탕을 두고 있다.연구자들은 해류에 의해 지배되는 지역에 상대적으로 높은 농도의 해양 파편이 쌓여 있는 것을 발견했다.일본해에서의 발견으로부터 추정하여, 연구원들은 지배적인 해류가 비교적 안정적인 물의 생성에 유리한 태평양의 다른 지역에서도 유사한 조건이 발생할 것이라는 가설을 세웠다. 일본해그들은 특히 북태평양 [12]자이를 가리켰다.

1997년 트랜스퍼시픽 요트 레이스에 참가한 후 북태평양 자이를 통해 귀국한 찰스 무어는 거대한 부유 잔해와 마주쳤다고 주장했다.무어는 해양학자 커티스 에베스마이어에게 경고했고, 커티스 에베스마이어는 이 지역을 "동부 가비지 패치(EGP)"[13]라고 불렀다.이 지역은 해양 [14]오염의 예외적인 예로 언론 보도에 자주 등장한다.

JUNK Raft Project는 Algalita Marine Research [15][16][17]Foundation에 의해 조직된 패치의 플라스틱을 강조하기 위해 만들어진 2008년 태평양 횡단 항해였다.

2009년에는, 프로젝트·카이세이·오션·보이즈·연구소의 2척의 프로젝트 선박, 뉴·호라이즌호와 카이세이호가 패치 조사를 실시해, 상업적인 규모의 수집·[18]재활용의 타당성을 판단하기 위한 항해를 개시했다.Scripps Institute of Ocean Voyages Institute/Project[19] Kaisei가 자금을 지원한 2009년 SEAPLEX 탐사에서도 이 패치를 조사했습니다.연구원들은 또한 플라스틱이 랜턴 [20][21]피쉬와 같은 중엽성 물고기에 미치는 영향을 조사하고 있었다.

2010년, Ocean Voyages Institute는 순환선에서 30일간의 탐험을 실시해, 2009년의 탐험으로부터 과학을 계속해, 시제품 정화 [22]장치를 테스트했다.

2012년 7월/8월, 오션 보이저스 연구소는 샌프란시스코에서 북태평양 기어의 동쪽 경계선(결국 리치몬드 브리티시 컬럼비아에서 끝남)까지 항해를 실시해, 기어를 방문한 귀환 항해를 실시했습니다.이번 탐험의 초점은 일본 지진 해일에 의한 쓰나미 [23][24]잔해의 정도를 조사하는 것이었다.

플라스틱 소스

2015년, 사이언스지에 실린 한 연구는 이 모든 쓰레기가 정확히 어디에서 나오는지를 밝혀내려고 했다.연구원들에 따르면 버려진 플라스틱과 다른 잔해들은 아시아 국가들로부터 동쪽으로 떠내려온 6개의 주요 원천은 다음과 같다.중국, 인도네시아, 필리핀, 베트남, 스리랑카, 태국.[25][26]사실, 해양 관리국은 중국, 인도네시아, 필리핀, 태국, 그리고 베트남이 다른 모든 나라들을 [27]합친 것보다 더 많은 플라스틱을 바다에 버린다고 보고했다.전 세계 플라스틱 해양 오염의 30%가 중국 단독으로 발생하고 있습니다(중국은 [28]세계 인구의 약 18%를 차지하고 있습니다).육지에서 발생한 파편과 그에 따른 해양 파편 축적을 늦추기 위한 노력은 해안 보전, 지구의 날 및 세계 청소의 [29][30][31][32]날에 의해 수행되었다.

내셔널 지오그래픽에 따르면, "바다에 있는 플라스틱의 80퍼센트는 육지에서 생산되고 나머지 20퍼센트는 배와 다른 해양에서 생산되는 것으로 추정된다.그러나 이 비율은 지역에 따라 다릅니다.2018년 연구에 따르면 합성 어망이 그레이트 퍼시픽 가비지 면적의 절반 가까이를 차지하고 있는 것으로 나타났습니다.이는 주로 해류 [33][34]역학과 태평양에서의 어업 활동 증가에 기인합니다."

2019년 9월, 해양 플라스틱 오염이 중국 [35]화물선에서 많이 발생한다는 연구 결과가 발표되었을 때, Ocean Cleanup 대변인은 다음과 같이 말했습니다. "모든 사람들은 비닐봉지, 빨대, 일회용 포장 사용을 중단함으로써 바다를 구하는 것에 대해 이야기합니다.그것도 중요하지만 바다에 나가면 꼭 그런 [36]것만은 아닙니다.

헌법

대태평양 쓰레기 지대는 [37]해류에 의해 모아진 해양 또는 해양 오염의 결과로 점차 형성되었다.북태평양의 북태평양 자이로 둘러싸인 비교적 정지해 있는 마위도를 차지하고 있다.이 회전 패턴은 북미와 일본 앞바다를 포함한 북태평양 전역에서 폐자재를 끌어모으고 있습니다.이 물질이 조류에 포착되면 바람에 의해 움직이는 표면 전류가 점차 파편을 중심으로 이동시켜 잡힌다.

2014년[38] 연구에서 연구원들은 전 세계 해양의 1571개 지점을 표본으로 추출하여 부표, 선, 그물과 같은 폐기된 어구가 플라스틱 해양 파편 [38]덩어리의 60% 이상을 차지한다는 사실을 밝혀냈습니다.2011년 EPA 보고서에 따르면, "해양 파편의 주요 원천은 플라스틱을 포함한 쓰레기와 제조 제품의 부적절한 폐기 또는 관리입니다.해양, 항구, 하천, 항만, 부두 및 빗물 배수구의 육지에서 잔해가 발생한다.해상에서는 어선, 정지 승강장,[39] 화물선에서 잔해가 발생한다.성분들은 수 마일에 걸친 버려진 어망에서부터 화장품과 연마제 [40]등에 사용되는 마이크로 펠릿에 이르기까지 크기가 다양합니다.컴퓨터 모델은 미국 서부 해안에서 날아온 가상의 파편 조각이 아시아로 향해서 [13]6년 후에 미국으로 돌아올 것이라고 예측하고 있다; 아시아 동부 해안에서 날아온 파편들은 1년 안에 미국에 [41][42]도착할 것이다.미세 플라스틱은 약 1조 8천억 개의 플라스틱 조각 중 94%를 차지하지만, 플라스틱 조각 79,000 미터 톤의 8%에 불과하며, 나머지는 대부분 어업에서 [43]생산됩니다.

2017년 연구에서는 1950년 이후 생산된 91억 톤의 플라스틱 중 거의 70억 톤이 [44]더 이상 사용되지 않는다고 결론지었다.저자들은 9%가 재활용됐고 12%가 소각됐으며 나머지 55억t은 해양과 [44]육지에 있는 것으로 추정하고 있다.

사이즈 견적

패치의 크기는 불확실하며, 대형 품목이 [45]드물기 때문에 파편의 정확한 분포도 불확실하다.대부분의 파편들은 항공기나 위성의 탐지를 피하기 위해 지표면 또는 바로 아래에 떠 있는 작은 플라스틱 입자로 구성되어 있다.대신에, 패치의 사이즈는 샘플링에 의해서 결정됩니다.쓰레기 매립지의 추정 크기는 160,000 평방 킬로미터이다.[46]그러나 이러한 추정치는 표본 추출의 복잡성과 다른 영역에 대한 조사 결과를 평가할 필요성을 고려할 때 추측에 불과하다.또한 패치의 크기는 정상보다 높은 수준의 원양 파편 농도에 의해 결정되지만, 오염물질의 "정상"과 "증가" 사이의 경계를 결정하여 해당 지역을 확실하게 추정할 수 있는 표준은 없다.

그물 기반 조사는 직접 관측보다 주관적이지 않지만 표본 추출이 가능한 면적에 대해서는 제한적이다(순 개구부 1-2m와 선박은 일반적으로 그물을 전개하기 위해 속도를 늦춰야 하므로 전용 선박의 시간이 필요하다.표본 추출된 플라스틱 파편은 순 그물 크기에 의해 결정되며, 연구 간의 의미 있는 비교를 위해 유사한 그물 크기가 필요하다.부유 잔해는 일반적으로 0.33mm 그물로 둘러싸인 네우스톤 또는 쥐 저인망으로 표본 추출한다.해양 쓰레기의 공간적 응집 수준이 매우 높기 때문에, 바다에 있는 쓰레기의 평균 풍부함을 적절히 특징짓기 위해 많은 수의 순 견인이 필요하다.1999년 북태평양 아열대 자이의 플라스틱 함량은 335,000개 항목/km, 5.1kg/km로22 1980년대에 수집된 표본보다 대략적으로 큰 규모였다.일본 근해에서도 플라스틱 파편이 극적으로 증가한 것으로 보고되고 있다.그러나 이러한 발견을 해석하는 데 있어 극도의 공간적 이질성 문제와 등가수질량 표본의 비교가 필요하기 때문에 주의할 필요가 있다. 즉, 일주일 간격으로 동일한 물의 구획을 검사하면 플라스틱 농도의 크기 변화를 [47]관찰할 수 있다.

--

2009년 8월, Gyre의 Scripps Institute of Oceanography/Project Kaisei SEAPLEX 조사 미션에서는, 패치를 통과하는 1,700 마일(2,700 km)의 경로를 따라 다양한 깊이와 순크기로 추출한 100개의 연속 샘플에 플라스틱 파편이 존재하는 것을 발견했습니다.조사 결과, 패치에는 큰 조각이 포함되어 있지만 전체적으로 환류 중심부를 향해 농도가 증가하는 작은 품목으로 구성되어 있으며, 표면 바로 아래에 보이는 이러한 '콘페티 같은' 조각은 영향을 받는 면적이 훨씬 [47][49][50]작을 수 있음을 시사한다.태평양 알바트로스 개체군으로부터 수집된 2009년 데이터는 두 개의 서로 다른 파편 [51]지대가 존재함을 시사한다.

2018년 3월, The Ocean Cleanup은 Mega- (2015)와 Airerial Expedition (2016)의 조사 결과를 요약한 논문을 발표했다.2015년에는 30척의 선박으로 그레이트 퍼시픽 쓰레기장을 건너 652개의 조사망으로 관찰과 샘플을 채취했다.그들은 총 120만 점의 작품을 수집했고, 그것을 세어 각각의 크기 등급으로 분류했다.더 크지만 더 희귀한 파편들을 설명하기 위해, 그들은 또한 2016년에 LiDAR 센서를 장착한 C-130 허큘리스 항공기로 이 파편을 오버플라이했다.두 탐험의 결과는 이 지역이 평방 킬로미터 당 10-100 킬로그램의 농도로 160만 평방 킬로미터에 이른다는 것을 알아냈습니다.그들은 1조 8천억 개의 플라스틱 조각으로 이 지역에 80,000 미터 톤이 있을 것으로 추정하며, 이 중 질량의 92%가 0.5 [52][53][5]센티미터보다 큰 물체에서 발견될 것이라고 한다.

NOAA 기술:

"대태평양 쓰레기 지역"은 언론에서 자주 사용되는 용어이지만, 북태평양의 해양 잔해 문제를 정확하게 묘사하지는 않는다."태평양 쓰레기 지대"라는 이름은 많은 사람들로 하여금 이 지역이 병과 다른 쓰레기 같은 해양 잔해물들로 이루어진 크고 연속적인 지역이라고 믿게 만들었다. 이는 위성이나 항공 사진으로 보여야 하는 말 그대로 쓰레기 섬과 유사하다.이것은 사실이 아니다.

--

2001년 연구에서 연구원들은[55] 뉴스톤에서 평균 질량이 km당2 5.1kg이고 km당2 334,721개의 플라스틱 입자를 발견했다.플라스틱의 전체 농도는 표본 추출된 많은 영역에서 동물성 플랑크톤 농도의 7배였다.물기둥 더 깊은 곳에서 채취한 샘플에서는 훨씬 낮은 농도의 플라스틱 입자(주로 단일 필라멘트 낚싯줄 조각)[56]가 발견되었습니다.

환경 문제

이물질 제거

2009년, Ocean Voyages Institute는, 다양한 [57]청소 시제품 장치를 시험하면서, 최초의 프로젝트 가이세이 정화 이니셔티브에서 5톤 이상의 플라스틱을 제거했습니다.

2012년 알갈리타/5 자일스 아시아 태평양 탐험대는 5월 1일 마셜 제도에서 시작되어 5 자일스 연구소, 알갈리타 해양 연구 재단 및 NOAA, 스크립스, IPRC, 우즈 홀 해양 연구소 등 여러 기관의 샘플을 수집하기 위해 패치를 조사했다.2012년, 해양교육협회는 선회장에서 연구 탐사를 실시했다.118개의 순견인이 실시되었고 거의 7만 개의 플라스틱 조각이 [58]집계되었다.

2012년, 골드스타인, 로젠버그, 청 연구원은 환의 미세 플라스틱 농도가 지난 40년 [59]동안 두 배나 증가했다는 것을 발견했다.

2013년 4월 11일, 예술가 마리아 크리스티나 피누치는 이리나 보코바 [61]사무총장 앞에서 유네스코 파리[60] 가비지 패치 주를 설립했습니다.

2018년 9월 9일, 수집 [62]작업을 시작하기 위해 첫 번째 수집 시스템이 순환에 배치되었다.이 해양 정화 프로젝트의 초기 시험 운영은 "해양 정화 시스템 001"을 샌프란시스코에서 약 240해리([63]260마일) 떨어진 시험 장소로 견인하기 시작했습니다."해양 정화 시스템 001"의 초기 시험운행은 4개월 동안 진행되었으며, "시스템 001/B"[64]의 설계와 관련된 귀중한 정보를 연구팀에 제공하였다.

2019년, 25일간의 탐험 기간 동안, 오션 보이저스 [65]연구소는 바다에서 40톤 이상의 플라스틱을 제거한 "가스 패치"에서 가장 큰 정화 기록을 세웠다.

2020년 Ocean Voyages Institute는 두 번의 탐험 과정 동안 바다에서 170톤(34만 파운드) 이상의 플라스틱을 제거한 "Garbage Patch"의 최대 정화 기록을 다시 세웠다.첫 45일간의 탐험은 103톤의 플라스틱을 제거했고 두 번째 탐험은 67톤 이상의 플라스틱을 쓰레기 [67]지대에서 제거했다.

2021년, The Ocean Cleaning은 "시스템 002"를 사용하여 63,182파운드(28,658kg)의 플라스틱을 수집했습니다.이 임무는 2021년 7월에 시작되어 2021년 [68]10월 14일에 끝났다.

2022년 그레이트 퍼시픽 쓰레기장에서 번성하는 생물 생태계를 발견한 결과, 이곳의 쓰레기를 치우는 것이 이 [69]플라스티블을 제거해 줄 수도 있다는 것을 알 수 있었다.

2022년 7월, The Ocean Cleaning은 "System 002"[70]를 사용하여 그레이트 퍼시픽 가비지 패치의 첫 번째 플라스틱 10만 kg을 제거하는 이정표에 도달했으며, 이전 [71]제품보다 10배 더 효과적이라고 주장하는 "System 03"으로 전환하는 것을 발표했다.

「 」를 참조해 주세요.

레퍼런스

메모들

- ^ 패치의 검출과 이력에 관한 구체적인 참고 자료에 대해서는, 다음의 관련 섹션을 참조해 주세요.일반적인 개요는 Dautel, Susan L. "Transoceanic Trash: Great Pacific Garbage Patch를 위한 국제 및 미국 전략", 3 Golden Gate U. Envtl. L. J. 181(2007)에 나와 있습니다.

- ^ "World's largest collection of ocean garbage is twice the size of Texas". USA Today. Archived from the original on 15 February 2020. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- ^ a b Philp, Richard B. (2013). Ecosystems and Human Health: Toxicology and Environmental Hazards, Third Edition. CRC Press. p. 116. ISBN 978-1466567214.

- ^ Albeck-Ripka, Livia (22 March 2018). "The 'Great Pacific Garbage Patch' Is Ballooning, 87,000,000,000 Tons of Plastic and Counting". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 11 January 2020. Retrieved 26 February 2020.

- ^ a b Lebreton, L.; Slat, B.; Ferrari, F.; Sainte-Rose, B.; Aitken, J.; Marthouse, R.; Hajbane, S.; Cunsolo, S.; Schwarz, A. (22 March 2018). "Evidence that the Great Pacific Garbage Patch is rapidly accumulating plastic". Scientific Reports. 8 (1): 4666. Bibcode:2018NatSR...8.4666L. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-22939-w. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 5864935. PMID 29568057.

- ^ Maser, Chris (2014). Interactions of Land, Ocean and Humans: A Global Perspective. CRC Press. pp. 147–48. ISBN 978-1482226393.

- ^ "Congress acts to clean up the ocean – A garbage patch in the Pacific is at least triple the size of Texas, but some estimates put it larger than the continental United States". The Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on 5 October 2008. Retrieved 10 October 2008.

- ^ "Great Pacific garbage patch: Plastic turning vast area of ocean into ecological nightmare". Santa Barbara News-Press. Archived from the original on 12 September 2015. Retrieved 13 October 2008.

- ^ Lovett, Richard A. (2 March 2010). "Huge Garbage Patch Found in Atlantic Too". National Geographic News. National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on 5 March 2010. Retrieved 4 March 2010.

- ^ Victoria Gill (24 February 2010). "Plastic rubbish blights Atlantic Ocean". BBC. Archived from the original on 27 August 2017. Retrieved 16 March 2010.

- ^ Day, Robert H.; Shaw, David G.; Ignell, Steven E. (1988). "The Quantitative Distribution and Characteristics of Neuston Plastic in the North Pacific Ocean, 1985–88. (Final Report to U.S. Department of Commerce, National Marine Fisheries Service, Auke Bay Laboratory. Auke Bay, Alaska)" (PDF). pp. 247–66. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 August 2019. Retrieved 18 July 2008.

- ^ "하지만 바다에 들어간 후 뉴스톤 플라스틱은 조류와 바람에 의해 재분배됩니다.예를 들어, 한국의 바다로 유입되는 플라스틱은 아북극 해류(아북극 해류)와 구로시오(Kuroshio, 1972년 과도 수역, 1976년 즐겨찾기 외, 1986년 나가타 외)에 의해 동쪽으로 이동한다.이와 같이 플라스틱은 고밀도 영역에서 저밀도 영역으로 운반됩니다.이러한 동쪽으로의 이동과 더불어 바람으로부터의 에크만 스트레스는 아북극의 지표수와 아지트로픽스를 전체적으로 과도수질량 쪽으로 이동하는 경향이 있다(Roden 1970: 그림 5 참조).이 에크만 흐름의 수렴 특성 때문에 과도수에서 밀도가 높은 경향이 있습니다.또한, 북태평양 중앙 환류(마스자와 1972년)의 일반적으로 수렴되는 물의 특성으로 인해 그곳에서도 고밀도가 초래될 것이다." (일, 외, 1988년, 페이지 261) (강조 추가)

- ^ a b Moore, Charles (November 2003). "Natural History Magazine". www.naturalhistorymag.com. Archived from the original on 17 September 2021. Retrieved 17 September 2021.

- ^ Berton, Justin (19 October 2007). "Continent-size toxic stew of plastic trash fouling swath of Pacific Ocean". San Francisco Chronicle. p. W-8. Archived from the original on 21 October 2007. Retrieved 22 October 2007.

- ^ Yap, Britt (28 August 2008). "A raft made of junk crosses Pacific in 3 months". USA Today. Archived from the original on 31 March 2010. Retrieved 30 September 2009.

- ^ "Raft made of junk bottles crosses Pacific". NBC News. 28 August 2008. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 30 September 2009.

- ^ Jeavans, Christine (20 August 2008). "Mid-ocean dinner date saves rower". BBC News. Archived from the original on 25 March 2010. Retrieved 30 September 2009.

- ^ Walsh, Bryan (1 August 2009). "Expedition Sets Sail to the Great Plastic Vortex". Time. Archived from the original on 4 August 2009. Retrieved 2 August 2009.

- ^ Goldstein Miriam C.; Rosenberg Marci; Cheng Lanna (2012). "Increased oceanic microplastic debris enhances oviposition in an endemic pelagic insect". Biology Letters. 8 (5): 817–20. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2012.0298. PMC 3440973. PMID 22573831.

- ^ Alison Cawood (12 August 2009). "SEAPLEX Day 11 Part 1: Midwater Fish". SEAPLEX. Archived from the original on 8 October 2009. Retrieved 2 June 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 유지보수: 부적합한 URL(링크) - ^ "Scientists Find 'Great Pacific Ocean Garbage Patch'" (Press release). National Science Foundation. 27 August 2009. Archived from the original on 23 April 2012. Retrieved 8 August 2013. Alt URL 2018년 12월 13일 Wayback Machine에 보관

- ^ Schwartz, Ariel (19 November 2010). "This Is What It's Like to Sail in the Pacific Trash Vortex". Fast Company. Archived from the original on 6 September 2019. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

- ^ "Pacific Ocean garbage mostly from home, not Japan tsunami". Canadian Broadcast News. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

- ^ Bigmuddygirl (14 August 2012). "Plastic problem plagues Pacific, researchers say". Plastic Soup News. Archived from the original on 6 July 2019. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

- ^ "Where did the trash in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch come from? How do we stop it?". USA Today. Archived from the original on 2 September 2019. Retrieved 16 January 2019.

- ^ Law, Kara Lavender; Narayan, Ramani; Andrady, Anthony; Perryman, Miriam; Siegler, Theodore R.; Wilcox, Chris; Geyer, Roland; Jambeck, Jenna R. (13 February 2015). "Plastic waste inputs from land into the ocean". Science. 347 (6223): 768–71. Bibcode:2015Sci...347..768J. doi:10.1126/science.1260352. PMID 25678662. S2CID 206562155.

- ^ Hannah Leung (21 April 2018). "Five Asian Countries Dump More Plastic into Oceans Than Anyone Else Combined: How You Can Help". Forbes. Archived from the original on 29 December 2021. Retrieved 23 June 2019.

China, Indonesia, Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam are dumping more plastic into oceans than the rest of the world combined, according to a 2017 report by Ocean Conservancy

- ^ Will Dunham (12 February 2019). "World's Oceans Clogged by Millions of Tons of Plastic Trash". Scientific American. Archived from the original on 16 November 2019. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

China was responsible for the most ocean plastic pollution per year with an estimated 2.4 million tons, about 30 percent of the global total, followed by Indonesia, the Philippines, Vietnam, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Egypt, Malaysia, Nigeria and Bangladesh.

- ^ "500,000 Volunteers Take Part in Earth Day 2019 Cleanup". Earth Day Network. 26 April 2019. Archived from the original on 28 August 2019. Retrieved 1 August 2019.

- ^ "Our progress so far..." TIDES. Ocean Conservancy. Archived from the original on 1 August 2019. Retrieved 1 August 2019.

- ^ "Earth Day Network Launches Great Global Clean Up". snews (Press release). 4 April 2019. Archived from the original on 23 December 2019. Retrieved 1 August 2019.

- ^ Olivia Rosane (12 September 2018). "Cleanup Day Is Saturday Around the World: Here's How to Help". EcoWatch. Archived from the original on 28 August 2019. Retrieved 1 August 2019.

- ^ Society, National Geographic (5 July 2019). "Great Pacific Garbage Patch". National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on 5 June 2020. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

- ^ Lebreton, L.; Slat, B.; Ferrari, F.; Sainte-Rose, B.; Aitken, J.; Marthouse, R.; Hajbane, S.; Cunsolo, S.; Schwarz, A.; Levivier, A.; Noble, K. (22 March 2018). "Evidence that the Great Pacific Garbage Patch is rapidly accumulating plastic". Scientific Reports. 8 (1): 4666. Bibcode:2018NatSR...8.4666L. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-22939-w. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 5864935. PMID 29568057.

Over three-quarters of the GPGP mass was carried by debris larger than 5 cm and at least 46% was comprised of fishing nets.

- ^ Ryan, Peter G.; Dilley, Ben J.; Ronconi, Robert A.; Connan, Maëlle (25 September 2019). "Rapid increase in Asian bottles in the South Atlantic Ocean indicates major debris inputs from ships". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 116 (42): 20892–97. Bibcode:2019PNAS..11620892R. doi:10.1073/pnas.1909816116. PMC 6800376. PMID 31570571.

- ^ "Ocean plastic waste probably comes from ships, report says". Agence France-Presse. 16 January 2012. Archived from the original on 3 October 2019. Retrieved 3 October 2019.

- ^ 이것과 무슨 일이 뒤따를지 들어, 칼, 데이비드 맥도웰(May–June 1999년)를 참조하십시오."는 바다 변화:Biogeochemical Variability 북 태평양 난지 Gyre"에.생태계도. 2(3):181–214. doi:10.1007/s100219900068.S2CID 46309501.gyres 들어 일반적으로, 스베르드 루프 HU, 존슨 MW, 플레밍 RH(1946년)를 참조하십시오.바다에는 그들의 물리학, 화학, 그리고 일반적인 생물입니다.뉴욕:Prentice-Hall.

- ^ a b Eriksen, Marcus; Lebreton, Laurent C. M.; Carson, Henry S.; Thiel, Martin; Moore, Charles J.; Borerro, Jose C.; Galgani, Francois; Ryan, Peter G.; Reisser, Julia (10 December 2014). "Plastic Pollution in the World's Oceans: More than 5 Trillion Plastic Pieces Weighing over 250,000 Tons Afloat at Sea". PLOS ONE. 9 (12). e111913. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9k1913E. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0111913. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4262196. PMID 25494041.

- ^ "Marine Debris in the North Pacific: A Summary of Existing Information and Identification of Data Gaps" (PDF). US Environmental Protection Agency. November 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 January 2016.

- ^ Ferris, David (May–June 2009). "Message in a bottle". Sierra. San Francisco: Sierra Club. Archived from the original on 2 September 2019. Retrieved 13 August 2009.

- ^ Faris, J.; Hart, K. (1994). "Seas of Debris: A Summary of the Third International Conference on Marine Debris". N.C. Sea Grant College Program and NOAA.

{{cite journal}}:Cite 저널 요구 사항journal=(도움말) - ^ "Garbage Mass Is Growing in the Pacific". NPR. 28 March 2008. Archived from the original on 20 January 2019. Retrieved 16 January 2019.

{{cite journal}}:Cite 저널 요구 사항journal=(도움말) - ^ Parker, Laura (22 March 2018). "The Great Pacific Garbage Patch Isn't What You Think it Is". National Geographic News. Archived from the original on 18 June 2019. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- ^ a b "Plastic pollution threatens to smother our planet". NewsComAu. Archived from the original on 21 July 2017. Retrieved 21 July 2017.

- ^ Brassey, Dr Charlotte (16 July 2017). "A mission to the Pacific plastic patch". BBC News. Archived from the original on 20 July 2017. Retrieved 21 July 2017.

- ^ "The Great Pacific Garbage Patch • The Ocean Cleanup". The Ocean Cleanup. Archived from the original on 10 February 2020. Retrieved 8 February 2022.

- ^ a b Ryan, P. G.; Moore, C. J.; Van Franeker, J. A.; Moloney, C. L. (2009). "Monitoring the abundance of plastic debris in the marine environment". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 364 (1526): 1999–2012. doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0207. JSTOR 40485978. PMC 2873010. PMID 19528052.

- ^ "Great Pacific Garbage Patch". Marine Debris Division – Office of Response and Restoration. NOAA. 11 July 2013. Archived from the original on 17 April 2014. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- ^ "OSU: Reports of giant ocean 'garbage patch' are exaggerated". KATU.com. Associated Press. 4 January 2011. Archived from the original on 14 February 2011.

- ^ "Oceanic 'garbage patch' not nearly as big as portrayed in media". Newsroom. Oregon State University. 4 January 2011. Archived from the original on 7 January 2011. Retrieved 16 February 2011.

- ^ Young, Lindsay C.; Vanderlip, Cynthia; Duffy, David C.; Afanasyev, Vsevolod; Shaffer, Scott A. (2009). Ropert-Coudert, Yan (ed.). "Bringing Home the Trash: Do Colony-Based Differences in Foraging Distribution Lead to Increased Plastic Ingestion in Laysan Albatrosses?". PLOS ONE. 4 (10): e7623. Bibcode:2009PLoSO...4.7623Y. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0007623. PMC 2762601. PMID 19862322.

- ^ "The Great Pacific Garbage Patch". The Ocean Cleanup. Archived from the original on 10 February 2020. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- ^ Lebreton, Laurent (22 March 2018). "The Exponential Increase of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch". The Ocean Cleanup. Archived from the original on 8 May 2018. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- ^ "What is the Great Pacific Garbage Patch?". National Ocean Service. NOAA. Archived from the original on 25 August 2017. Retrieved 25 August 2017.

- ^ Moore, Charles (November 2003). "Across the Pacific Ocean, plastics, plastics, everywhere". Natural History Magazine. Archived from the original on 17 August 2019. Retrieved 16 March 2022.

- ^ Moore, C.J; Moore, S.L; Leecaster, M.K; Weisberg, S.B (2001). "A Comparison of Plastic and Plankton in the North Pacific Central Gyre". Marine Pollution Bulletin. 42 (12): 1297–300. doi:10.1016/S0025-326X(01)00114-X. PMID 11827116.

- ^ "Mining The Sea Of Plastic". 17 August 2009. Archived from the original on 17 February 2022. Retrieved 17 February 2022.

- ^ Emelia DeForce (9 November 2012). "The Final Science Report". Plastics at SEA North Pacific Expedition. Sea Education Association. Archived from the original on 2 March 2020. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- ^ Goldstein, M. C.; Rosenberg, M.; Cheng, L. (2012). "Increased oceanic microplastic debris enhances oviposition in an endemic pelagic insect". Biology Letters. 8 (5): 817–20. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2012.0298. PMC 3440973. PMID 22573831.

- ^ "The garbage patch territory turns into a new state". United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. 22 May 2019. Archived from the original on 11 September 2017. Retrieved 5 November 2014.

- ^ "Rifiuti diventano stato, Unesco riconosce 'Garbage Patch'". SITI. L'Associazione Città e Siti Italiani – Patrimonio Mondiale UNESCO. ISSN 2038-7237. Archived from the original on 3 November 2014 – via rivistasitiunesco.it.

- ^ Lavars, Nick (17 October 2018). "Ocean Cleanup system installed and ready for work at the Great Pacific Garbage Patch". newatlas.com. Archived from the original on 21 December 2018. Retrieved 16 January 2019.

- ^ Dent, Steve (11 September 2018). "A project to remove 88,000 tons of plastic from the Pacific has begun". Engadget. Archived from the original on 23 November 2018. Retrieved 16 January 2019.

- ^ "System 001". The Ocean Cleanup. Archived from the original on 9 November 2021. Retrieved 17 September 2021.

- ^ "Environmentalists remove 40 tonnes of abandoned fishing nets from Great Pacific Garbage Patch". ABC News. 29 June 2019. Archived from the original on 17 February 2022. Retrieved 17 February 2022.

- ^ "Worlds Largest Ocean Cleanup". 6 July 2020. Archived from the original on 17 February 2022. Retrieved 17 February 2022.

- ^ "Sailing Cargo Vessel Recovers 67 Tons of Ocean Plastic". 7 August 2020. Archived from the original on 27 September 2020. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- ^ "More than 63,000 pounds of trash removed from one of the biggest accumulations of ocean plastic in the world". www.cbsnews.com. Archived from the original on 19 October 2021. Retrieved 5 November 2021.

- ^ Abby Lee Hood (1 May 2022). "Hooray! The Great Pacific Garbage Patch Has Become a Thriving Ecosystem, Scientists Say". Futurism.

- ^ erika (25 July 2022). "First 100,000 KG Removed From the Great Pacific Garbage Patch • Updates • The Ocean Cleanup". The Ocean Cleanup. Retrieved 28 July 2022.

- ^ erika (21 July 2022). "Transition to System 03 Begins • Updates • The Ocean Cleanup". The Ocean Cleanup. Retrieved 28 July 2022.

추가 정보

- Oliver J. Dameron; Michael Parke; Mark A. Albins; Russell Brainard (April 2007). "Marine debris accumulation in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands: An examination of rates and processes". Marine Pollution Bulletin. 54 (4): 423–33. doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2006.11.019. PMID 17217968.

- Rei Yamashita; Atsushi Tanimura (2007). "Floating plastic in the Kuroshio Current area, western North Pacific Ocean". Marine Pollution Bulletin. 54 (4): 485–88. doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2006.11.012. PMID 17275038.

- Masahisa Kubota; Katsumi Takayama; Noriyuki Horii (2000). "Movement and accumulation of floating marine debris simulated by surface currents derived from satellite data" (PDF). School of Marine Science and Technology, Tokai University. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 November 2008. Retrieved 5 June 2008.

- Gregory, M.R.; Ryan, P.G. (1997). "Pelagic plastics and other seaborne persistent synthetic debris: a review of Southern Hemisphere perspectives". In Coe, J.M.; Rogers, D.B. (eds.). Marine Debris: Sources, Impacts, Solutions. New York: Springer-Verlag. pp. 49–66.

- Moore, Charles G.; Phillips, Cassandra (2011). Plastic Ocean. Penguin Group. ISBN 978-1452601465.

- 캘리포니아 연안에서 북태평양 중앙 자이로 가는 동물성 플랑크톤 트롤선에서 발견된 플라스틱 입자 밀도 - 2018년 4월 27일 웨이백 머신에서 보관 – Charles J Moore, Gwen L L Lattin 및 Ann F Zellers(2005)

- H. Day, Robert; Shaw, David; E. Ignell, Steven (1 January 1990). "The quantitative distribution and characteristics of neuston plastic in the North Pacific Ocean, 19841988" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 November 2019. Retrieved 16 January 2019.

{{cite journal}}:Cite 저널 요구 사항journal=(도움말) - Morton, Thomas (2007). "Oh, This is Great, Humans Have Finally Ruined the Ocean". Vice magazine. Vol. 6, no. 2. pp. 78–81. Archived from the original on 25 July 2008.

- Hohn, Donovan (2011). Moby-Duck: The True Story of 28,800 Bath Toys Lost at Sea. Viking. ISBN 978-0670022199.

- Hoshaw, Lindsey (9 November 2009). "Afloat in the Ocean, Expanding Islands of Trash". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 20 May 2013. Retrieved 10 November 2009.

- Newman, Patricia (2014). Plastic, Ahoy!: Investigating the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. Millbrook Press. ISBN 978-1467725415.

외부 링크

- 태평양 가비지 패치– Smithsonian Ocean Portal

- "플라스틱 서프" 장난감과 포장의 건강하지 못한 사후세계: 장난감, 병, 포장의 작은 잔해가 바다에 남아 해양 생물과 심지어 우리에게 해를 끼친다.2010년 8월 사이언티픽 아메리칸, 제니퍼 애커맨

- Plastic Paradise Movie – Plastic Paradise로 알려진 Great Paradise Patch의 미스터리를 밝히는 Angela Sun의 독립 다큐멘터리

- 가비지 패치, 사진의 소스

- 아일랜드 심사관 기사

- 유튜브를 통해 호놀룰루를 출발하는 메가 탐험대

- 유튜브의 플라스틱 섬 미드웨이

- 기후변화, 종말론적인 쌍둥이를 만나보세요. 플라스틱에 오염된 바다입니다.국제 공중파 라디오2016년 12월 13일

- 2050년까지, 바다는 물고기보다 플라스틱을 더 많이 가질 수 있을 것이다.비즈니스 인사이더 2017년 1월 27일

- The Ocean Cleanup. "Scientific publications". Retrieved 21 October 2018.

- Dunning, Brian (16 December 2008). "Skeptoid #132: The Sargasso Sea and the Pacific Garbage Patch". Skeptoid.

- "The Ocean Cleanup in One Year".

- L. Lebreton (2017). "Evidence that the Great Pacific Garbage Patch is rapidly accumulating plastic". Scientific Reports (1st ed.). 8 (1): 4666. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-22939-w. PMC 5864935. PMID 29568057.