카슈미르 힌두교도의 대탈출

Exodus of Kashmiri Hindus 인도령 카슈미르 계곡이나 힌두교도의 상당수가 이주한 카슈미르 계곡을 보여주는 분쟁지역의 정치지도 | |

| 날짜. | 1990년 초.[1][2] |

|---|---|

| 위치 | 카슈미르 계곡, 인도령 카슈미르 |

| 좌표 | 34°02'00 ″N 74°40'00 ″E/34.0333°N 74.6667°E |

| 결과 | |

| 데스 | |

카슈미르 힌두교도들의 대탈출,[note 2] 혹은 판디트들은 1990년[1][2] 초 인도령 카슈미르의 이슬람교도들이 다수를 차지하는 카슈미르 계곡에서 반란으로 폭력이 증가함에 따라 [20]이들이 이주한,[19] 혹은 도주한 것입니다.판디트의 총 인구 120,000~140,000명 중 약 90,000~100,000명이 1990년 중반에 계곡을[3][5][4][7] 떠났거나 떠날 수 밖에 없다고 느꼈으며,[21][note 3] 이때까지 그들 중 약 30~80명이 무장세력에 의해 살해되었다고 합니다.[7][12][13]

상당한 규모의 이주 기간 동안, 반란은 세속적이고 독립적인 카슈미르를 요구하는 단체에 의해 주도되고 있었지만, 이슬람 국가를 요구하는 이슬람 계파들도 증가하고 있었습니다.[24][25][26]비록 그들의 사망자와 부상자의 수는 적었지만,[27] 카슈미르의 문화가 인도와 연관되어 있다고 믿었던 팬디트들은 [6][28]그들의 계급 중 고위 관리들을 포함한 그들의 공동체의 일부 구성원들에 대한 표적 살인과 반란군들 사이의 독립에 대한 대중의 요구로 촉발된 공포와 공황을 경험했습니다.[29]주 정부에 의해 그들의 안전에 대한 보장이 없는 것과 함께 동반된 소문과 불확실성이 탈출의 잠재적인 원인이었을지도 모릅니다.[30][31]일부 힌두 민족주의 출판물이나 일부 추방된 판디트들이 주장하는 의혹들 가운데서 폭력을 "대학살" 혹은 "인종청소"로 묘사하는 것은 학자들에 의해 부정확하고 공격적인 것으로 널리 여겨지고 있습니다.[32][33][34][35]

이 이주의 이유는 치열하게 논쟁 중입니다.1989-1990년 카슈미르 무슬림들의 인도로부터의 독립 요구가 속도를 내면서, 자결주의를 반민족적이라고 생각했던 많은 카슈미르 팬디트들은 압박감을 느꼈습니다.[36]1990년대에 일어난 다수의 판디트 관리들의 살해 사건은 지역사회의 안전의식을 흔들었을 수도 있지만, 일부 판디트들은 나중에 인도 법정에서 제시된 증거들 덕분에 인도 국가의 대리인 역할을 했을 수도 있다고 생각됩니다.[37]잠무와 카슈미르 해방 전선(JKLF)의 표적 암살로 사망한 팬디트들 중에는 세간의 이목을 끄는 사람들도 포함되어 있습니다.[38]때때로 반 힌두교도들은 판디트에게 계곡을 떠나라고 요청하는 확성기를 통해 모스크로부터 전화를 받았습니다.[39][40]위협적인 편지들의 소식은 공포를 자아냈지만,[41] 이후의 인터뷰에서 편지들은 거의 받지 못한 것으로 보였습니다.[42]이슬람교도와 판디트 두 공동체의 설명 사이에 차이가 있었습니다.[43]많은 카슈미르 팬디트들은 자신들이 파키스탄과 자신들이 지지하는 무장세력에 의해 또는 카슈미르 무슬림들에 의해 계곡에서 쫓겨났다고 믿고 있습니다.[44]많은 카슈미르 무슬림들은 종교적 소수자들에 대한 폭력을 지지하지 않았습니다. 카슈미르 팬디트의 탈퇴는 카슈미르 무슬림들을 이슬람 급진주의자로 간주하고,[45] 그들의 더 진정한 정치적 불만을 오염시키고, [46]인도 국가의 감시와 폭력적인 대우에 대한 근거를 제공했습니다.[47]계곡의 많은 이슬람교도들은 당시 주지사였던 자그모한이 무슬림들에 대한 보복을 더 철저히 하는 데 있어 자유의 손을 가질 수 있도록 팬디트들에게 떠나도록 격려했다고 믿었습니다.[48][49]몇몇 학자들은 판디트들의 진정한 공황상태로의 이주를, 일부 반군들 사이의 종교적 폭력에서 비롯된 것으로 보고 있습니다. 이는 주지사가 판디트들의 안전에 대한 보장이 없기 때문인 것과 마찬가지로, 판디트들의 종교적 폭력에서 비롯된 것입니다.[26][50]

카슈미르 판디트는 처음에는 잠무와 카슈미르의 남반부인 잠무 사단으로 이주하여 난민 수용소에서 살았고, 때로는 지저분하고 부정한 환경에서 살았습니다.그들의 출애굽기 당시, 극소수의 팬디트만이 그들의 망명이 몇 달 이상 지속될 것이라고 예상했습니다.[51]망명이 더 오래 지속됨에 따라, 도시 엘리트 계층에 있던 많은 추방자 팬디트들은 인도의 다른 지역에서 일자리를 찾을 수 있었지만, 중산층 이하의 사람들, 특히 시골 지역 출신의 사람들은 난민 캠프에서 더 오래 고통을 받았고, 몇몇은 가난하게 살았습니다. 이것은 사회적 그리고 종교적 실천을 하는 수용소와 긴장을 일으켰습니다.s, 비록 힌두교도였지만, 브라만 판디트의 그것들과 달랐고, 동화를 더 어렵게 만들었습니다.[52]수용소의 많은 난민 팬디트들은 감정적인 우울감과 무력감에 굴복했습니다.[53]카슈미르 판디트의 대의는 인도의 우파 힌두 집단들에 의해 빠르게 옹호되었는데,[54] 이들은 또한 그들의 불안을 잡아먹고 카슈미르 무슬림들로부터 그들을 더욱 소외시켰습니다.[55]일부 실향민 카슈미르 팬디트들은 파눈 카슈미르("우리 고유의 카슈미르")라는 조직을 결성했는데, 파눈 카슈미르는 계곡에 있는 카슈미르 힌두교도들을 위해 별도의 고국을 요청했지만 이슬람 국가 형성을 촉진할 것이라는 이유로 카슈미르 자치에 반대해 왔습니다.[56]카슈미르에 있는 고향으로의 귀환은 집권 인도국민당의 선거 강령 중 하나이기도 합니다.[57][note 4]비록 팬디트와 무슬림 사이의 논의가 각자의 박탈감에 대한 부분을 고집하고 상대방의 고통에 대한 거부로 인해 방해를 받았지만, 카슈미르를 떠난 팬디트는 분리되어 없어졌다고 느꼈습니다.[58]망명 중인 카슈미르 판디트들은 그들의 경험을 기록하고 이해하기 위해 자전적 회고록, 소설, 시를 썼습니다.[59] 1월 19일 카슈미르 힌두 공동체는 출애굽의 날로 기념합니다.[60][61]

배경

카슈미르 계곡은 1947년부터 인도와 파키스탄 사이에 분쟁의 대상이 된 카슈미르 지역의 한 부분으로, 대략 같은 시기부터 인도에 의해 관리되고 있습니다.[62][63]1947년 이전까지 인도의 영국령 인도 제국 시기에는 1889년부터 1941년까지 인구조사에서 카슈미르 판디트 또는 카슈미르 힌두교도가 카슈미르 계곡 인구의 4%에서 6% 사이를 안정적으로 구성했습니다. 나머지 94%에서 96%는 카슈미르 계곡의 이슬람교도로 수니파 이슬람교도의 압도적인 추종자였습니다.[64][65][66][67][68]이 이슬람교도들은 우세한 공동체에 대한 확신을 가지고 있었습니다; 그들의 지지는 카슈미르의 미래를 결정하는 결과적인 것으로 여겨졌습니다.[69]1950년까지 카슈미르의 군주가 인도에 대한 해결되지 않은 가입, 셰이크 압둘라의 차기 행정부에 의해 계획된 토지 개혁, 사회 경제적 쇠퇴의 위협에 직면하여, 계곡의 경작지의 30% 이상을 엘리트들이 소유하고 있던 판디트들의 많은 수가 인도의 다른 지역으로 이주했습니다.[70][71]

1989년 카슈미르에서 지속적인 반란이 시작되었습니다.이는 1987년 총선 조작과 자치권 확대 약속을 부인한 인도 연방정부에 대한 카슈미르인들의 불만이 계기가 됐습니다.그 불만은 인도 국가에 대한 명확하지 않은 봉기로 넘쳐났습니다.잠무 카슈미르 해방 전선(JKLF)은 [6][25][72]일반적으로 세속적인 선례를 가지고 있었고 정치적 독립의 주요 목표를 가지고 있던 단체였지만 폭력을 포기하지는 않았습니다.[73][74]1990년 초, 대다수의 카슈미르 힌두교도들은 집단 이주를 통해 계곡을 탈출했습니다.[75][76][77][note 5][note 6]그 후 몇 년 동안 그들 중 더 많은 사람들이 떠났기 때문에 2011년까지 약 3,000 가구만이 남아 있었습니다.[8]일부 학자들에 따르면, 1990년 3월 중순까지 30명 혹은 32명의 카슈미르 팬디트들이 반란군들에 의해 살해되었는데, 이 때 탈출이 거의 완료되었다고 합니다.[7][12]인도 내무부 자료에는 1988년부터 1991년까지 4년 동안 217명의 힌두교 민간인 사망자가 기록되어 있습니다.[14][note 7]

1975년 인디라 정권하에서-셰이크 압둘라 대통령은 잠무와 카슈미르에서 중앙정부가 인도를 통합하기 위해 이전에 취했던 조치들에 동의했습니다.[80]카슈미르 대학의 사회학자인 파룩 파힘은 카슈미르 주민들 사이에 적대감이 있었고 미래의 반란을 위한 기반을 마련했다고 말합니다.[81]이 협정에 반대하는 사람들은 자마트-e-이슬람리 카슈미르, 인도 잠무와 카슈미르의 인민동맹, 파키스탄이 통치하는 아자드 잠무와 카슈미르에 기반을 둔 잠무 카슈미르 해방 전선(JKLF)을 포함했습니다.[82]1970년대 중반부터, 그 주에서는 투표 은행 정치를 위해 공동체주의적 수사가 이용되고 있었습니다.이 시기에 파키스탄의 ISI(Inter-Services Intelligence)는 수피즘을 대신하여 와하비즘을 전파하여 그들의 국가 내 종교적 통합을 촉진하려고 노력했고, 공동체화는 그들의 대의명분을 도왔습니다.[83]카슈미르의 이슬람화는 1980년대 셰이크 압둘라 정부가 300여 곳의 이름을 이슬람 이름으로 바꾸면서 시작됐습니다.[84][note 8]셰이크는 또한 1930년대에 그의 대립적인 독립 찬성 연설과 비슷한 이슬람 사원에서 공동 연설을 하기 시작했습니다.또한 그는 카슈미르 힌두교도들을 무크비르(힌두스타니어: मुख़बिर, مخبر) 또는 인도 군대의 정보원이라고도 했습니다.

인도 행정부를 상대로 카슈미르에 광범위한 소요를 뿌리려는 ISI의 초기 시도는 1980년대 후반까지 대체로 성공적이지 못했습니다.[88]미국과 파키스탄의 지원을 받는 아프가니스탄 무자헤딘이 소련-아프간 전쟁에서 소련에 대항한 무장투쟁, 이란의 이슬람혁명, 인도 펀자브의 시크교도 정부에 대항한 반란은 많은 수의 카슈미르 무슬림 젊은이들에게 영감의 원천이 되었습니다.[89][90]독립을 지지하는 JKLF와 자마트-에-이슬람 카슈미르를 포함한 친파키스탄 이슬람 단체들은 카슈미르 주민들 사이에서 급격히 증가하는 반인도 정서를 동원했습니다. 1984년에는 카슈미르에서 테러 폭력이 현저하게 증가했습니다.1984년 2월 JKLF 무장세력 막불 바트가 처형된 후, 카슈미르 민족주의자들의 파업과 시위가 이 지역에서 발생했고, 많은 수의 카슈미르 청년들이 광범위한 반인도 시위에 참여했고 결과적으로 국가 보안군의 고압적인 보복에 직면했습니다.[91][92]

당시 총리였던 파루크 압둘라를 비판하는 사람들은 그가 상황을 통제하지 못했다고 비난했습니다.JKLF의 하심 쿠레시(Hashim Qureshi)에 따르면 이 기간 동안 파키스탄이 관리하는 카슈미르를 방문한 그는 JKLF와 플랫폼을 공유했다고 합니다.[93]압둘라는 자신이 인디라 간디와 그의 아버지를 대신하여 갔다고 주장하여, 비록 그를 믿는 사람들이 거의 없었지만, 그곳의 감정이 "직접적으로 알려질 수 있도록" 하였습니다.그가 칼리스타니 무장대원들이 잠무에서 훈련하도록 허락했다는 주장도 있었지만, 이는 결코 사실로 입증되지 않았습니다.1984년 7월 2일, 인디라 간디의 지지를 받은 굴람 모하마드 샤는 처남인 파루크 압둘라를 대신하여 총리직을 맡았는데, 이를 "정치 쿠데타"라고 합니다.[92]

국민의 권한이 없었던 G.M. Shah의 행정부는 이슬람주의자들과 인도의 반대자들, 특히 몰비 이프티카르 후세인 안사리, 모하마드 샤피 쿠레시, 모히누딘 살라티에게 종교적 정서를 통해 어느 정도의 정당성을 얻기 위해 눈을 돌렸습니다.이것은 1983년 주 선거에서 압도적으로 패배한 이슬람주의자들에게 정치적 공간을 주었습니다.[92]1986년, 샤는 잠무의 신 시민 사무국 지역 안에 있는 고대 힌두 사원의 부지 내에 이슬람 사원을 건설하기로 결정했습니다. 이 모스크는 이슬람 사원들이 '나마즈'를 위해 사용할 수 있도록 하기 위해서입니다.잠무 사람들은 이 결정에 항의하기 위해 거리로 나섰고, 이것은 힌두교와 이슬람교의 충돌로 이어졌습니다.[94]1986년 2월, 카슈미르 계곡으로 돌아온 샤는 이슬람 카흐트레 마인 헤이(이슬람이 위험에 처해 있다)transl.라고 말하며 카슈미르 무슬림들을 보복하고 선동했습니다.결과적으로, 이것은 카슈미르 힌두교도들이 카슈미르 무슬림들의 표적이 되었던 1986년 카슈미르 폭동으로 이어졌습니다.카슈미르 힌두교도들이 살해되고 재산과 사원이 훼손되거나 파괴되는 사건이 여러 지역에서 많이 보고되었습니다.최악의 피해를 입은 지역은 주로 남카슈미르와 소포레였습니다.1986년 2월 아난트나그 폭동 동안, 힌두교도들은 살해되지 않았지만, 많은 가옥들과 힌두교도들의 다른 재산들이 약탈당하고, 불에 탔거나, 훼손되었습니다.[95]아난트나그 폭동을 조사한 결과 이슬람주의자가 아닌 국가의 '세속 정당' 구성원들이 종교적 정서를 통해 정치적 마일리지를 얻기 위해 폭력을 조직하는 데 핵심적인 역할을 한 것으로 드러났습니다.샤는 폭력을 억제하기 위해 군대를 불렀지만 별 효과가 없었습니다.1986년 3월 12일 자그모한 주지사에 의해 카슈미르 남부에서 일어난 공동 폭동으로 그의 정부는 해임되었고, 주지사의 통치로 이어졌습니다.따라서 이 정치적 싸움은 힌두 뉴델리(중앙정부)와 이슬람 정치인과 성직자로 대표되는 이슬람 카슈미르 사이의 갈등으로 묘사되고 있습니다.[96]

1987년 주 선거를 위해 자마트-e-이슬람 카슈미르를 포함한 다양한 이슬람 단체들이 이슬람 통합 전선이라는 기치 아래 이슬람 통합을 위해 노력하고 중앙의 정치적 간섭에 반대하는 선언문을 가지고 조직되었습니다.두 주류 정당(NC와 INC)이 연합하여 선거에서 승리했지만, 선거는 주류 연합에 유리하게 조작되었다고 널리 믿어지고 있기 때문에 파루크 압둘라에 의해 구성된 정부는 정당성이 부족했습니다.[97]부패와 선거 부정 행위는 반란의 촉매제가 되었습니다.[98][99][100]카슈미르 무장세력은 공개적으로 친인도 정책을 표명한 자들을 살해했습니다.카슈미르 힌두교도들이 특별히 표적이 된 것은 그들의 믿음 때문에 카슈미르에서 인도인들의 존재를 보여주는 것으로 여겨졌기 때문입니다.[101]JKLF에 의해 반란이 시작되었지만, 이슬람 단체들에 대한 니잠-e-무스타파(샤리아에 기반을 둔 행정부) 설립, 파키스탄과의 합병, 움마의 통일, 이슬람 칼리프 국가의 설립을 지지하는 단체들이 다음 몇 달 동안 일어났습니다.중앙 정부 관리들, 힌두교도들, 자유주의적이고 민족주의적인 지식인들, 사회적이고 문화적인 활동가들의 청산은 비이슬람적인 요소들을 제거하는 데 필요하다고 묘사되었습니다.[102][103]주류 정당들과 이슬람 단체들 간의 관계는 대체로 좋지 못했고 종종 적대적이었습니다.JKLF는 또한 이슬람과 독립을 상호 교환하여 동원 전략과 공개 담론에 이슬람 공식을 사용했습니다.모든 사람의 동등한 권리를 요구했지만 이슬람 민주주의, 코란과 순나에 따른 소수자 권리 보호, 이슬람 사회주의의 경제를 확립하려고 했기 때문에 이것은 뚜렷한 이슬람적 분위기를 가지고 있었습니다.친분리주의적 정치관행은 때로는 그들의 세속적인 입장에서 벗어났습니다.[104][105]

반란군

1988년 7월 잠무 카슈미르 해방전선(JKLF)은 인도로부터 카슈미르를 분리하기 위한 분리주의 반란을 시작했습니다.[106]이 단체는 1989년 9월 14일 처음으로 카슈미르 힌두교도를 목표로 삼았는데, 이 때 그들은 잠무와 카슈미르의 인도인민당의 지지자이자 저명한 지도자였던 티카 랄 타플루를 여러 목격자들 앞에서 살해했습니다.[107][108]이것은 카슈미르 힌두교도들에게 두려움을 심어주었는데, 특히 타블로의 살인자들이 결코 잡히지 않았기 때문에 테러리스트들을 대담하게 만들었습니다.힌두교도들은 그들이 계곡에서 안전하지 않다고 느꼈고 언제든지 표적이 될 수 있다고 느꼈습니다.많은 저명한 힌두교도들을 포함한 카슈미르 힌두교도들의 살해는 더 많은 두려움을 심어주었습니다.[109][better source needed]

당시 잠무와 카슈미르의 수장이었던 그의 정치적 라이벌인 파루크 압둘라를 약화시키기 위해 인도 내무장관 무프티 모하마드 사이드는 총리 V.P.를 설득했습니다. 싱은 자그모한을 주지사로 임명했습니다.압둘라는 1984년 4월 초에 주지사로 임명된 자그모한을 원망했고 1984년 7월 라지브 간디에게 압둘라의 해임을 권고했습니다.압둘라는 앞서 자그모한이 주지사가 된다면 사임하겠다고 선언한 바 있습니다.그러나 중앙정부가 나서서 그를 총독으로 임명했습니다.이에 압둘라는 1990년 1월 18일 사임했고, 자그모한은 의회 해산을 제안했습니다.[110]

대부분의 카슈미르 힌두교도들은 카슈미르 계곡을 떠나 인도의 다른 지역, 특히 잠무 지역의 난민 캠프로 이주했습니다.[111]

공격 및 위협

1989년 9월 14일, 변호사이자 BJP 당원이었던 티카 랄 타플루가 스리나가르의 자택에서 JKLF에 의해 살해당했습니다.[108][107]

11월 4일, 닐칸스 간주 판사가 스리나가르 고등법원 근처에서 총에 맞아 사망했습니다.그는 1968년 카슈미르 분리주의자 막불 바트에게 사형을 선고했습니다.[107][112][113]

지난 12월 JKLF 회원들은 당시 연합 장관 무프티 모하마드 사이드의 딸인 루바이야 사이드 박사를 납치해 무장세력 5명의 석방을 요구했고 이후 이행됐습니다.[114][115][116]

1990년 1월 4일, 스리나가르에 기반을 둔 신문 아프타브는 모든 힌두교도들에게 카슈미르를 즉시 떠나라고 위협하는 메시지를 발표했고, 무장 단체 히즈불 무자헤딘에 이 메시지를 전달했습니다.[117][118][119][unreliable source?]1990년 4월 14일, 스리나가르에 본부를 둔 또 다른 신문 알사파는 같은 경고를 재발행했습니다.[107][120]신문은 성명서의 소유권을 주장하지 않았고 그에 따라 해명서를 발표했습니다.[117][118]벽에는 이슬람 복장 규정에 따른 준수, 술, 영화관, 비디오 가게[122] 금지, 여성에 대한 엄격한 제한 등이 포함된 이슬람 규칙을[121] 엄격하게 따르라는 모든 카슈미르인들에 대한 위협적인 메시지가 담긴 포스터가 붙여졌습니다.[123]칼라시니코프를 쓴 무명 복면가들은 사람들에게 시간을 파키스탄 표준시로 재설정하도록 강요했습니다.사무실 건물, 상점 그리고 건물들은 이슬람 통치의 상징으로 초록색으로 물들었습니다.[119][124]카슈미르 힌두교도들의 상점, 공장, 사원 그리고 집들이 불에 타거나 파괴되었습니다.힌두교도들이 카슈미르를 즉각 떠나라는 내용의 협박 포스터가 문에 붙여졌습니다.[119][125]1월 18일과 19일의 한밤중에, 카슈미르 힌두교도들을 숙청해달라는 분열적이고 선동적인 메시지를 방송한 모스크를[citation needed] 제외하고는 전기가 끊긴 카슈미르 계곡에서 정전이 일어났습니다.[126][127][better source needed]

자그모한이 주지사로 취임한 지 이틀 후인 1월 21일, 스리나가르에서 인도 보안군이 시위대에 발포하여 최소 50명, 약 100명 이상의 사망자를 낸 가카달 학살이 일어났습니다.이 사건들은 혼돈으로 이어졌습니다.무법자들이 계곡을 점령하고 구호와 총을 든 군중들이 거리를 배회하기 시작했습니다.폭력적인 사건들에 대한 뉴스들이 계속해서 오고 있었고, 밤에 살아남은 많은 힌두교도들은 계곡 밖으로 여행을 함으로써 목숨을 구했습니다.[128][129][106]

1월 25일, 라왈포라 총격 사건이 일어났고, 인도 공군 4명, 비행대대장 라비 칸나, D.B. 상병이 발생했습니다.싱, 우데이 샹카르 상병, 아자드 아흐마드 항공사 직원 10명이 사망하고 IAF 직원 10명이 부상을 입었습니다. 이들은 라왈포라 버스 정류장에서 아침에 자신들의 차량을 태우기 위해 기다리고 있었습니다.테러리스트들이 총 40발 정도를 발사했는데, 2발에서 3발의 자동 무기와 1발의 반자동 권총으로 보입니다.인근에 위치한 잠무와 카슈미르 무장경찰 초소에는 무장 순경 7명과 순경 1명이 배치돼 있으나 별다른 반응을 보이지 않았습니다.특히 야신 말리크 지도자와 함께 잠무 카슈미르해방전선(JKLF)이 이번 사건에 연루된 것으로 알려졌습니다.이와 같은 사건들은 힌두교도들이 카슈미르에서 탈출하는 것을 더욱 가속화시켰습니다.[130][131][132][133]

정보 요원 몇 명이 1월에 걸쳐 암살당했습니다.[134][116]

2월 2일, 젊은 힌두 사회복지사 사티시 티쿠가 스리나가르주 하바 카달에 있는 자신의 집 근처에서 살해당했습니다.[107][135]

2월 13일, 스리나가르 두르다르샨의 방송국 국장인 라사 카울이 총에 맞아 사망했습니다.[107][136]

4월 29일, 카슈미르의 베테랑 시인이자 그의 아들인 사르완과 쿨 프레미가 총에 맞아 교수형에 처했습니다.[137]

6월 4일, 카슈미르 힌두교 교사인 기리자 티쿠가 테러리스트들에게 집단 강간을 당했는데, 그들은 그녀가 살아있을 때 그녀의 복부를 찢고 톱 기계로 그녀의 몸을 두 조각으로 잘랐습니다.[138]

많은 카슈미르 판디트 여성들이 탈출 기간 내내 납치되고 강간당하고 살해당했습니다.[139][122]카슈미르의 힌두교도 지역 조직인 카슈미르 판디트 상가르쉬 사미티(KPSS)는 2008년과 2009년 조사를 실시한 후 1990년에 카슈미르에서 357명의 힌두교도가 사망한 것으로 추정했습니다.[140]

잔상

탈출 이후 카슈미르 내 전투력이 증가했고, 무장세력들은 카슈미르 힌두교도들의 사유지를 목표로 삼았습니다.[141][142]인도 내무부 자료는 1991년부터 2005년까지 1,406명의 힌두 민간인 사망자를 기록하고 있습니다.[14]잠무와 카슈미르 정부는 1989년에서 2004년 사이에 219명의 힌두 판디트 공동체 구성원이 살해당했으며 그 이후에는 한 명도 살해되지 않았다고 밝혔습니다.[16][143]파눈 카슈미르 조직은 1990년 이후 약 1,341명의 힌두교도 사망자 명단을 발표했습니다.[107]카슈미르의 힌두교도 지역 조직인 KPSS(Pandit Sangharsh Samiti)는 2008년과 2009년 조사를 실시한 후 1990년부터 2011년까지 399명의 카슈미르 힌두교도가 반란군에 의해 살해되었으며, 그 중 75%가 카슈미르 반란 첫 해에 살해되었으며, 지난 20년 동안에는약 650명의 힌두교도들이 그 계곡에서 살해당했습니다.[144][145]

출애굽기에 대응하여 카슈미르를 탈출한 힌두교도들을 대표하는 정치 집단인 파눈 카슈미르라는 조직이 결성되었습니다.1991년 말, 이 기구는 카슈미르 지역인 파눈 카슈미르에 별도의 연합 영토가 필요하다는 마르그다르샨 결의안을 채택했습니다.파눈 카슈미르는 카슈미르 힌두교도들의 고향이 될 것이며, 추방된 카슈미르 팬디트들을 재정착시킬 것입니다.[146]

2009년 오리건 주 의회는 2007년 9월 14일을 이슬람 국가를 세우려는 무장세력에 의해 잠무와 카슈미르의 비이슬람 소수민족들에게 가해진 인종청소와 테러운동을 인정하는 순교자의 날로 인정하는 결의안을 통과시켰습니다.[147]

카슈미르 힌두교도들은 계곡으로 돌아가기 위한 투쟁을 계속하고 있으며 많은 수가 난민으로 살고 있습니다.[148]추방된 공동체는 상황이 호전된 후에 돌아오기를 희망했습니다.대부분의 사람들은 계곡의 상황이 불안정하고 생명에 위협이 될까 봐 그렇게 하지 않았습니다.그들 대부분은 출애굽 이후 재산을 잃었고 많은 사람들이 돌아가서 팔 수가 없습니다.실향민이라는 그들의 지위는 교육의 영역에서 그들에게 악영향을 끼쳤습니다.많은 힌두 가족들은 자녀들을 좋은 평가를 받는 공립학교에 보낼 여유가 없었습니다.게다가, 많은 힌두교도들은 주로 이슬람 국가 관료들에 의해 제도적인 차별에 직면했습니다.난민 수용소에 형성된 미흡한 임시 학교와 대학의 결과로, 힌두 아이들이 교육을 받기가 더 어려워졌습니다.이들은 잠무대 PG대학에서도 입학을 주장할 수 없었고 카슈미르 계곡 학원에서도 입학이 불가능해 고등교육에서도 어려움을 겪었습니다.[149]

2016년 부르한 와니 살해 사건 이후 카슈미르 소요 사태 동안 카슈미르의 카슈미르 힌두교도들을 수용하는 환승 캠프가 폭도들의 공격을 받았습니다.[150]카슈미르 힌두교도 직원 200-300명은 7월 12일 밤 시간에 이 공격으로 인해 환승 캠프에서 도망쳤고, 정부에 항의하는 시위를 열고 카슈미르 계곡에 있는 모든 카슈미르 힌두교도 직원들을 즉시 대피시킬 것을 요구했습니다.지역 사회 소속 공무원 1300명 이상이 소요 기간 동안 이 지역을 탈출했습니다.[151][152][153]힌두교도들에게 카슈미르를 떠나거나 살해당하겠다고 위협하는 포스터도 무장단체 라슈카르-에-토이바에 의해 주장되는 풀와마의 환승 캠프 근처에 붙여졌습니다.[154][155]

카슈미르의 뿌리라고 불리는 한 단체는 2017년 700건 이상의 카슈미르 힌두교도 살해 혐의 사건 215건을 재개할 것을 청원했지만, 인도 대법원은 이 청원을 거부했습니다.[156]또 인종청소와 범죄를 조사할 '특별범죄재판소'를 만들 것을 요구했습니다.그들은 또한 정부 일자리에 지원할 수 없는 실향민 카슈미르 힌두교도들에게 일시적인 보상을 요구했습니다.[157]

재활

인도 정부는 힌두교도들을 재건하기 위해 노력했고 분리주의자들은 또한 힌두교도들을 카슈미르로 다시 초대했습니다.[158]

UPA 정부에 의해 2008년에 Rs. 1,168크로어 패키지가 발표된 이후 2016년 현재, 총 1,800명의 카슈미르 힌두 청년들이 이 계곡으로 돌아갔습니다.그러나, 유스 올 인디아 카슈미르 사마즈의 회장 R.K. 바트는 이 패키지가 단순한 눈가림에 불과하다고 비판하고, 대부분의 젊은이들이 비좁은 조립식 창고나 임대된 숙소에서 살고 있다고 주장했습니다.그는 또 2010년 이후 4천 개의 게시물이 공석이 됐다며 BJP 정부가 같은 언사를 반복하고 있으며 그들을 돕는 것에 진지하지 않다고 주장했습니다.정부 측의 무관심과 카슈미르 힌두교도들의 고통은 '카슈 카슈미르'라는 연극을 통해 부각됐습니다.[159]이러한 노력이나 주장은 언론인 라훌 판디타가 회고록에서 쓰는 것처럼 정치적 의지가 부족했습니다.[160]

1월 19일 NDTV와의 인터뷰에서 파루크 압둘라는 카슈미르 힌두교도들이 스스로 돌아올 책임이 있으며 아무도 그렇게 해달라고 애원하지 않을 것이라고 말해 논란을 일으켰습니다.그의 발언은 카슈미르 힌두 작가 니루 카울, 싯다르타 기구, 하원의원 샤시 타루어, 중위의 반대와 비판에 부딪혔습니다.Syed Ata Hasain 장군 (retd.그는 또한 1996년 그가 총리로 재임하는 동안 그들에게 복귀를 요청했지만 그들은 이를 거부했다고 말했습니다.그는 1월 23일에 자신의 언급을 반복했고 그들이 돌아올 때가 왔다고 말했습니다.[161][162][163][164]

카슈미르 힌두교도들을 위한 분리된 마을 문제는 이슬람주의자들과 분리주의자들은 물론 주류 정당들이 모두 반대하면서 카슈미르 계곡의 논쟁거리가 되어 왔습니다.[165]히즈불 무자헤딘 무장세력 부르한 무자파르 와니는 비이슬람 공동체의 재건을 위해 건설되어야 할 "힌두 복합 타운쉽"을 공격하겠다고 위협했습니다.6분 길이의 동영상에서 와니는 재활 계획이 이스라엘의 디자인과 비슷하다고 묘사했습니다.[166]그러나 부르한 와니는 카슈미르 힌두교도들이 돌아오는 것을 환영하고 그들을 지키겠다고 약속했습니다.그는 안전한 아마르나트 야트라를 약속하기도 했습니다.[167]계곡에 거주하는 카슈미르 힌두교도들도 부르한 와니의 죽음을 애도했습니다.[168]부르한 와니의 자칭 히즈불 무자헤딘 후계자 자키르 라시드 바트도 카슈미르 힌두교도들에게 귀환을 요청하고 그들의 보호를 보장했습니다.[169][170]

2010년 잠무 카슈미르 정부는 3,445명을 포함한 808명의 힌두교도 가족이 여전히 계곡에 살고 있으며 다른 사람들이 그곳으로 돌아오도록 장려하기 위해 시행된 재정적 및 기타 인센티브가 성공적이지 못하다고 언급했습니다.[16]고용 패키지도 2017년 10월 J&K 이주민(Special Drive) 채용 규칙 2009 개정으로 계곡 밖으로 이주하지 않은 힌두인으로 확대되었습니다.[171]인도 정부는 카슈미르에서 온 실향민 학생들의 교육 문제를 제기하고, 이들이 전국의 여러 켄드리야 비디얄라야와 주요 교육 기관 및 대학에 입학할 수 있도록 지원했습니다.

일부에서는 잠무와 카슈미르 헌법이 잠무와 카슈미르 밖의 인도에 거주하는 사람들이 자유롭게 국가에 정착하여 시민이 되는 것을 허용하지 않기 때문에 현재 폐지된 370조를 카슈미르 힌두교도 재정착의 장애물로 간주하고 있습니다.[172][173][174]산제이 티쿠 카슈미르 판디트 상가르쉬 사미티(KPSS) 회장은 '370조' 문제는 카슈미르 힌두교도들의 출애굽 문제와는 다르며 둘 다 따로 다뤄야 한다고 말합니다.그는 두 가지 일을 연결시키는 것은 "매우 민감하고 감정적인 문제를 다루는 완전히 둔감한 방법"[citation needed]이라고 말합니다.

대중문화에서

책들

- 인도 기자 라훌 판디타가 쓴 2013년 책 우리의 달에는 혈전이 있습니다. 이는 출애굽기에 대한 최초의 설명을 바탕으로 한 것입니다.

- 고향에 대한 오랜 꿈 – 싯다르타 기구와 바라드 샤르마에 의한 카슈미르 판디트의 박해, 망명 그리고 탈출

무비

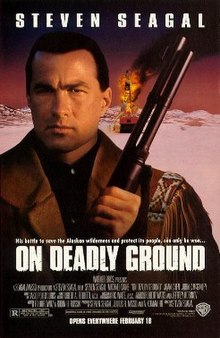

- 비두 비노드 초프라 감독의 2020 힌디어 영화 시카라는 카슈미르 힌두교도들의[175] 탈출을 바탕으로 합니다.

- 비벡 아그니호트리[176] 감독의 2022년 힌디어 영화 카슈미르 파일

참고 항목

메모들

- ^ 또 다른 사람은 총 인구 20만 명 중 19만 명으로 추정하고 있습니다.[10]CIA 팩트북은 그 숫자를 30만으로 추정했습니다.[11]

- ^ 옥스포드 영어 사전 온라인은 엑소더스를 "보통 다른 곳에 정착하기 위한 목적으로 한 나라에서 온 사람들의 집단이 떠나거나 나가는 것"이라고 정의합니다.cf. '이민 n. 2': 한 나라에서 온 사람들, 보통 그들의 모국에서 다른 나라에 영구적으로 정착하기 위해 떠나는 것.[18]

- ^ 카슈미르 팬디트는 국제 국경을 넘지 않았기 때문에 "난민"으로 간주되지 않습니다.많은 팬디트들은 내부 실향민으로 간주되기를 원하지만, 인도 정부는 카슈미르에 대한 국제적인 개입을 우려하여 그들의 지위를 부인했습니다.인도 정부는 카슈미르 팬디트를 '이주자'로 간주하고 있습니다.[22][23]

- ^ 카슈미르 팬디트는 국제 국경을 넘지 않았기 때문에 "난민"으로 간주되지 않습니다.많은 사람들이 내부 실향민으로 간주되기를 원하지만, 인도 정부는 카슈미르에 대한 국제적인 개입을 우려하여 그들의 지위를 부인했습니다.인도 정부는 카슈미르 팬디트를 '이주자'로 간주하고 있습니다.

- ^ 몇몇 학자들에 의하면, 약 90,000~100,000명의 팬디트들이 1990년 초에 120,000~140,000명의 사람들이 떠났다고 합니다.[1][2]다른 학자들은 출애굽을 위해 약 15만 명의 더 높은 수치를 제시했습니다.[9][78]

- ^ 또 다른 사람은 총 인구 20만 명 중 19만 명으로 추정하고 있습니다.[10]CIA 팩트북은 그 숫자를 30만으로 추정했습니다.[11]

- ^ Alexander Evans는 Pandit 민간인 사망자를 228명, 즉 관리들의 사망까지 포함하면 388명으로 추정하고 있지만, 700명이라는 더 높은 수치는 심각하게 믿을[15] 수 없는 것으로 보고 있습니다. 학자들은 카슈미르 계곡 내에 있는 카슈미르 판디트 단체들의 말을 인용하여 1990년 이후 20년 동안의 힌두 민간인 사망자를 650명으로 보고했습니다.무장세력에 의해 인도 정보요원으로 의심되는 [79]사람들을 포함한 집계

- ^ 다른 소식통들은 그가 2,500개의 지명을 바꿨다고 주장합니다.[85]

참고문헌

- ^ a b c

- Bose, Sumantra (2021), Kashmir at the Crossroads: Inside a 21st-century conflict, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, p. 373, ISBN 978-0-300-25687-1,

Some Pandits constituted a privileged class under the princely state (1846–1947). When insurrection engulfed the Valley in early 1990, approximately 120,000 Pandits lived in the Valley, making up about 3 per cent of the Valley's population. In February–March 1990, the bulk of the Pandits (about 90,000–100,000 people) left the Valley for safety amid incidents of intimidation and sporadic killings of prominent members of the community by Kashmiri Muslim militants; most moved to the southern, Hindu-majority Indian J&K city of Jammu or to Delhi.

- Rai, Mridu (2021), "Narratives from exile: Kashmiri Pandits and their construction of the past", in Bose, Sugata; Jalal, Ayesha (eds.), Kashmir and the Future of South Asia, Routledge Contemporary South Asia Series, Routledge, pp. 91–115, 106, ISBN 9781000318845,

Beginning in January 1990, such large numbers of Kashmiri Pandits – the community of Hindus native to the valley of Kashmir – left their homeland and so precipitously that some have termed their departure an exodus. Indeed, within a few months, nearly 100,000 of the 140,000- strong community had left for neighbouring Jammu, Delhi, and other parts of India and the world.

- Hussain, Shahla (2021), Kashmir in the Aftermath of the Partition, Cambridge University Press, pp. 320, 321, ISBN 9781108901130,

The Counter-narrative of Aazadi: Kashmiri Hindus and Displacement of the Homeland (p. 320) In March 1990, the majority of Kashmiri Hindus left the Valley for "refugee" camps in and outside the Hindu-dominated region of Jammu.

- Duschinski, Haley (2018), "'Survival Is Now Our Politics': Kashmiri Pandit Community Identity and the Politics of Homeland", Kashmir: History, Politics, Representation, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 172–198, 179, ISBN 9781108226127,

Although various political stakeholders dispute the number of Kashmiri Pandits who left the Valley at that time, Alexander Evans estimates on the basis of census data and demographic figures that over 1,00,000 left in a few months in early 1990, while 1,60,000 in total left the Valley during the 1990s

- Gates, Scott; Roy, Kaushik (2016) [2011], Unconventional Warfare in South Asia, 1947 to the Present, Critical Essays on Warfare in South Asia, 1947 to the Present, London and New York: Routledge, ISBN 9780754629771, LCCN 2011920454,

India's response has been more brutal than ever before. The government's efforts to roll back the insurgency and the militants' armed resolve to "liberate" Kashmir have produced daily deaths. The Muslims constitute a majority of those killed, primarily by India's armed forces but also by armed Muslim militants silencing dissenters in their own community. The number of Hindus killed would have been greater if most of them had not migrated to camps in Jammu and Delhi. Some left after losing kith and kin to Islamic militants, others after receiving death threats, but most departed in utter panic between January and March 1990—simply to preempt death. Of the more than 150,000 Hindus, only a few are left in the valley.

- Bose, Sumantra (2021), Kashmir at the Crossroads: Inside a 21st-century conflict, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, p. 373, ISBN 978-0-300-25687-1,

- ^ a b c

- Kapur, S. Paul (2007), Dangerous Deterrent: Nuclear Proliferation and Conflict in South Asia, Stanford University Press, pp. 102–103, ISBN 978-0-8047-5549-8,

When the Kashmir insurgency began, roughly 130,000 to 140,000 Kashmiri Pandits, who are Hindus, lived in Kashmir Valley. By early 1990, in the face of some targeted anti-Pandit attacks and rising overall violence in the region, approximately 100,000 Pandits had fled the valley, many of them ending up in refugee camps in southern Kashmir.

- Braithwaite, John; D'Costa, Bina (2018), "Recognizing cascades in India and Kashmir", Cacades of violence:War, Crime and Peacebuilding Across South Asia, Australian National University Press, ISBN 9781760461898,

... when the violence surged in early 1990, more than 100,000 Hindus of the valley—known as Kashmiri Pandits—fled their homes, with at least 30 killed in the process.

- Kumar, Radha; Puri, Ellora (2009), "Jammu and Kashmir: Frameworks for a Settlement", in Kumar, Radha (ed.), Negotiation Peace in Deeply Divided Societies: A Set of Simulations, New Delhi, Los Angeles and London: SAGE Publications, p. 292, ISBN 978-81-7829-882-5,

1990: In January BJP strongman Jagmohan is reappointed Governor. Farooq Abdullah resigns. A large number of unarmed protesters are killed in firing by the Indian troops in separate incidents. 400,000 Kashmiris march to the UN Military Observers Group to demand implementation of the plebiscite resolution. A number of protestors are killed after the police fires at them. A number of prominent Kashmiris are killed by militants, among whom Pandits form a substantial number. Pandits begin to be forced out of the Kashmir valley. The rise of new militant groups, some warnings in anonymous posters and some unexplained killings of innocent members of the community, contribute to an atmosphere of insecurity for the Kashmiri Pandits. Estimated 140,000 Hindus, including the entire Kashmiri Pandit community, flee the valley in March.

- Hussain, Shahla (2018), "Kashmiri Visions of Freedom", Kashmir: History, Politics, Representation, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, pp. 89–112, 105, ISBN 9781107181977,

In the winter of 1990, the community felt compelled to mass-migrate to Jammu, as the state governor was adamant that in the given circumstances he would not be able to offer protection to the widely dispersed Hindu community. This event created unbridgeable differences between the majority and the minority; each perceived aazadi in a different light.

- Kapur, S. Paul (2007), Dangerous Deterrent: Nuclear Proliferation and Conflict in South Asia, Stanford University Press, pp. 102–103, ISBN 978-0-8047-5549-8,

- ^ a b Bose, Sumantra (2021), Kashmir at the Crossroads: Inside a 21st-century conflict, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, p. 373, ISBN 978-0-300-25687-1,

Some Pandits constituted a privileged class under the princely state (1846–1947). When insurrection engulfed the Valley in early 1990, approximately 120,000 Pandits lived in the Valley, making up about 3 per cent of the Valley's population. In February–March 1990, the bulk of the Pandits (about 90,000–100,000 people) left the Valley for safety amid incidents of intimidation and sporadic killings of prominent members of the community by Kashmiri Muslim militants; most moved to the southern, Hindu-majority Indian J&K city of Jammu or to Delhi.

- ^ a b Kapur, S. Paul (2007), Dangerous Deterrent: Nuclear Proliferation and Conflict in South Asia, Stanford University Press, pp. 102–103, ISBN 978-0-8047-5549-8,

When the Kashmir insurgency began, roughly 130,000 to 140,000 Kashmiri Pandits, who are Hindus, lived in Kashmir Valley. By early 1990, in the face of some targeted anti-Pandit attacks and rising overall violence in the region, approximately 100,000 Pandits had fled the valley, many of them ending up in refugee camps in southern Kashmir.

- ^ a b Rai, Mridu (2021), "Narratives from exile: Kashmiri Pandits and their construction of the past", in Bose, Sugata; Jalal, Ayesha (eds.), Kashmir and the Future of South Asia, Routledge Contemporary South Asia Series, Routledge, pp. 91–115, 106, ISBN 9781000318845,

Beginning in January 1990, such large numbers of Kashmiri Pandits – the community of Hindus native to the valley of Kashmir – left their homeland and so precipitously that some have termed their departure an exodus. Indeed, within a few months, nearly 100,000 of the 140,000-strong community had left for neighbouring Jammu, Delhi, and other parts of India and the world. One immediate impetus for this departure in such dramatically large numbers was the inauguration in 1989 of a popularly backed armed Kashmiri insurgency against Indian rule. This insurrection drew support mostly from the Valley's Muslim population. By 2011, the numbers of Pandits remaining in the Valley had dwindled to between 2,700 and 3,400, according to different estimates. An insignificant number have returned.

- ^ a b c Metcalf, Barbara D.; Metcalf, Thomas R. (2012), A Concise History of Modern India, Cambridge Concise Histories (3 ed.), Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 308–309, ISBN 978-1-107-02649-0,

The imposition of leaders chosen by the centre, with the manipulation of local elections, and the denial of what Kashmiris felt was a promised autonomy boiled over at last in the militancy of the Jammu and Kashmir Liberation Front, a movement devoted to political, not religious, objectives. The Hindu Pandits, a small but influential elite community who had secured a favorable position, first under the maharajas and then under the successive Congress governments, and who propagated a distinctive Kashmiri culture that linked them to India, felt under siege as the uprising gathered force. Upwards of 100,000 of them left the state during the early 1990s; their cause was quickly taken up by the Hindu right. As the government sought to locate 'suspects' and weed out Pakistani 'infiltrators', the entire population was subjected to a fierce repression. By the end of the 1990s, the Indian military presence had escalated to approximately one soldier or paramilitary policeman for every five Kashmiris, and some 30,000 people had died in the conflict.

- ^ a b c d e Braithwaite, John; D'Costa, Bina (2018), "Recognizing cascades in India and Kashmir", Cacades of violence:War, Crime and Peacebuilding Across South Asia, Australian National University Press, ISBN 9781760461898,

... when the violence surged in early 1990, more than 100,000 Hindus of the valley—known as Kashmiri Pandits—fled their homes, with at least 30 killed in the process.

- ^ a b Evans 2002, p. 20: "1990년 초, 많은 KP들이 카슈미르 계곡을 떠나기 시작했습니다.몇 달 사이에 10만 명 이상이 떠났고, 그 이후로 모두 16만 명 정도가 카슈미르 계곡을 떠났습니다.모든 KP가 떠난 것은 아니지만, 오늘날 단지 소수의 KP만이 남아있습니다.1990년의 초기 이주민들 대부분은 처음에는 지저분한 난민 캠프에서 살았던 잠무로 떠났지만, 1997년에는 대부분이 잠무의 적절한 집이나 인도의 다른 도시로 이주했습니다.난민 수용소의 상황은 암울했고, 지금도 그렇습니다."

- ^ a b Talbot, Ian; Singh, Gurharpal (2009), The Partition of India, New Approaches to Asian History, Cambridge University Press, pp. 136–137, ISBN 9780521672566,

Between 1990 and 1995, 25,000 people were killed in Kashmir, almost two-thirds by Indian armed forces. Kashmirs put the figure at 50,000. In addition, 150,000 Kashmiri Hindus fled the valley to settle in the Hindu-majority region of Jammu.

- ^ a b 마단 2008, 25쪽

- ^ a b "South Asia. India". The World Factbook – Central Intelligence Agency. 21 December 2021.

- ^ a b c Bose, Sumantra (2021), Kashmir at the Crossroads, Inside a 21st-Century Conflict., Yale University Press, p. 92, ISBN 978-0-300-25687-1,

On 15 March 1990, by which time the Pandit exodus from the Valley was substantially complete, the All-India Kashmiri Pandit Conference, a community organisation, stated that thirty-two Pandits had been killed by militants since the previous autumn.

- ^ a b Joshi, Manoj (1999), The Lost Rebellion, Penguin Books, p. 65, ISBN 978-0-14-027846-0,

By the middle of the year some eighty persons had been killed ..., and the fear ... had its effect from the very first killings. Beginning in February, the pandits began streaming out of the valley, and by June some 58,000 families had relocated to camps in Jammu and Delhi.

- ^ a b c Swami 2007, p.

- ^ a b Evans 2002, pp. 19–37, 23: "인도 정부 수치는 잠무와 카슈미르의 테러 폭력 프로필에 나와 있습니다(뉴델리: 내무부, 1998년 3월).1988년에서 1991년 사이에 정부는 228명의 힌두 민간인이 살해되었다고 주장합니다.같은 기간 사망한 정부 관료와 정치인들이 힌두교 신자여서 여기에 더해지면 이 수치는 최대 160명까지 더 늘어날 것으로 보입니다.따라서 700이라는 수치는 대단히 신뢰할 수 없는 것처럼 보입니다."

- ^ a b c "Front Page : "219 Kashmiri Pandits killed by militants since 1989"". The Hindu. 24 March 2010. Archived from the original on 25 March 2010.

- ^ Manzar, Bashir (2013), "Kashmir: A Tale of Two Communities, Cloven", Economic and Political Weekly, XLVIII (30): 177–178, JSTOR 23528003,

Official records suggest that 219 Kashmiri Pandits had been killed by militants since 1989.

- ^ ""Exodus, n."", Oxford English Dictionary Online, Oxford University Press, 2021

- ^

- Evans 2002, p. 20(p. 19) 본 논문은 다음과 같이 구성됩니다.먼저 1990년 이후 KP들에게 일어난 일을 설명하고자 한다.(p. 20) 집단이주의 몰락을 살펴본 후 극단주의 정치를 살펴본 후 현대 상황에 대한 평가로 마무리한다.(p. 22) 1990년에 일어난 일에 대한 세 번째 가능한 설명, 즉 장자를 인정하는 것.KP 이주의 계기가 된 KP들이 합법적인 두려움을 통해 집단 이주한 것을 자세히 살펴봅니다(p. 24). 1961년에서 2001년 사이에 10년 단위의 성장률이 상승한 반면, 같은 기간 잠무와 카슈미르에서 KP들의 이주는 어느 정도 이루어졌습니다.

- Zia, Ather (2020), Resisting Disappearnce: Military Occupation and Women's Activism in Kashmir, University of Washington Press, p. 60, ISBN 9780295745008,

In the early 1990s the Kashmiri Hindus, known as the Pandits (a 100,000 to 140,000 strong community), migrated en masse from Kashmir to Jammu, Delhi, and other places.

- Hussain, Shahla (2018), "Kashmiri Visions of Freedom", Kashmir: History, Politics, Representation, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, pp. 89–112, 105, ISBN 9781107181977,

The rise of insurgency in the region created a difficult situation for the Kashmiri Hindu community, which had always taken pride in their Indian identity. Self-determination was not only seen as a communal demand but as a secessionist slogan that threatened the security of the Indian state. The community felt threatened when Kashmiri Muslims under the flag of aazadi openly raised anti-India slogans. The 1989 targeted killings of Kashmiri Hindus who the insurgents believed were acting as Indian intelligence agents heightened those insecurities. In the winter of 1990, the community felt compelled to mass-migrate to Jammu, as the state governor was adamant that in the given circumstances he would not be able to offer protection to the widely dispersed Hindu community.

- Duschinski, Haley (2014), "Community Identity of Kashmiri Hindus in the United States", Emerging Voices: Experiences of Underrepresented Asian Americans, Rutgers University Press,

The mass migration of Kashmiri Hindus from Kashmir Valley began in November 1989 and accelerated in the following months. Every family has its departure story. Many families simply packed their belongings into their cars and left under cover of night, without words of farewell to friends and neighbours. In some cases, wives and children left first, while husbands stayed behind to watch for the situation to improve; in other cases, parents sent their teenage sons away after hearing threats against them, and followed them days or weeks later. Many migrants report that they entrusted their house keys and belongings to the Muslim neighbours or servants and expected to return to their homes after a few weeks. Tens of thousands of Kashmiri Hindus left Kashmir Valley in the span of several months. There are also competing perspectives on the factors that led to the mass migration of Kashmiri Hindus during this period. Kashmiri Hindus describe migration as a forced exodus driven by Islamic fundamendalist elements in Pakistan that spilled across the Line of Control into the Kashmir Valley. They think that Kashmiri Muslims had acted as bystanders to violence by not protecting lives and properties of the vulnerable Hindu community from the militant ... The mass migration, however, was understood differently by the Muslim religious majority in Kashmir. These Kashmiri Muslims, many of whom were committed to the cause of regional independence, believed that Kashmiri Hindus betrayed them by withdrawing their support from the Kashmiri nationalist movement and turning to the government of India for protection at the moment of ... This perspective is supported by claims, articulated by some prominent separatist political leaders, that the Indian government orchestrated the mass migration of the Kashmiri Hindu community in order to have a free hand to crack down on the popular uprising. These competing perspectives gave rise to mutual feelings of suspicion and betrayal—feelings that lingered between Kashmiri Muslims and Kashmiri Hindus and became more entrenched as time continued.

- Bhatia, Mohita (2020), Rethinking Conflict at the Margins: Dalits and Borderland Hindus in Jammu and Kashmir, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 9, ISBN 9781108883467,

Despite witnessing a prolonged spell of insurgency including a few incidents of selective killings, Jammu was still considered to be a relatively safe refuge by the Hindu community of Kashmir, the Pandits. As a minuscule Hindu minority community in the Muslim-majority Kashmir (around 3 per cent of Kashmir's population), they felt more vulnerable and noticeable as insurgency peaked in Kashmir. Lawlessness, uncertainty, political turmoil along with a few target killings of Pandits led to the migration of almost the entire community from the Valley to other parts of the country

- Bhan, Mona; Misri, Deepti; Zia, Ather (2020), "Relating Otherwise: Forging Critical Solidarities Across the Kashmiri Pandit-Muslim Divide.", Biography, 43 (2): 285–305, doi:10.1353/bio.2020.0030, S2CID 234917696,

...the everyday modes of relating that existed between Kashmiri Pandits and Muslims in the period leading up to the "Migration," as the Pandit departures have come to be called among Kashmiris, both Pandit and Muslim.

- Duschinski, Haley (2018), "'Survival Is Now Our Politics': Kashmiri Pandit Community Identity and the Politics of Homeland", Kashmir: History, Politics, Representation, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 172–198, 178–179, ISBN 9781108226127,

The Kashmiri Pandit migration: (p. 178) The onset of the armed phase of the freedom struggle in 1989 was a chaotic and turbulent time in Kashmir (Bose, 2003). Kashmiri Pandits felt an increasing sense of vulnerability

- Zutshi 2003, p. 318 인용문: "지주의 대다수가 힌두교이기 때문에 (1950년의) 토지 개혁으로 힌두교도들이 국가에서 대규모로 탈출하게 되었습니다."카슈미르의 인도 진출의 불안정한 성격과 토지 개혁에 직면한 경제적, 사회적 쇠퇴의 위협이 맞물려 잠무의 힌두교도들과 카슈미르 판디트 사이의 불안이 커졌고, 이들 중 20%는 1950년까지 이 계곡에서 이주했습니다."

- ^

- Bose, Sumantra (2021), Kashmir at the Crossroads, Inside a 21st-Century Conflict, Yale University Press, pp. 119–120,

As insurrection gripped the Kashmir Valley in early 1990, the bulk – about 100,000 people – of the Pandit population fled the Valley over a few weeks in February–March 1990 to the southern Indian J&K city of Jammu and further afield to cities such as Delhi. ... The large-scale flight of Kashmiri Pandits during the first months of the insurrection is a controversial episode of the post-1989 Kashmir conflict.

- Talbot, Ian; Singh, Gurharpal (2009), The Partition of India, New Approaches to Asian History, Cambridge University Press, pp. 136–137, ISBN 9780521672566,

Between 1990 and 1995, 25,000 people were killed in Kashmir, almost two-thirds by Indian armed forces. Kashmiris put the figure at 50,000. In addition, 150,000 Kashmiri Hindus fled the valley to settle in the Hindu-majority region of Jammu.

- Metcalf & Metcalf 2006, p. 274 처음에는 마하라자 체제에서, 그 다음에는 의회 체제에서, 그리고 그들을 인도와 연결시킨 독특한 카슈미르 문화를 지지하는 작지만 영향력 있는 엘리트 공동체인 힌두 판디트들은 봉기가 힘을 모으자 포위를 느꼈습니다.약 140,000명의 인구 중, 아마도 100,000명의 팬디들이 1990년 이후에 그 주를 도망쳤습니다.

- Bose, Sumantra (2021), Kashmir at the Crossroads, Inside a 21st-Century Conflict, Yale University Press, pp. 119–120,

- ^

- Brass, Paul (1994), The Politics of India Since Independence, The New Cambridge History of India (2 ed.), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 222–223, ISBN 978-0-521-45362-2

- Hussain, Shahla (2018), "Kashmiri Visions of Freedom", Kashmir: History, Politics, Representation, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, pp. 89–112, 105, ISBN 9781107181977,

In the winter of 1990, the community felt compelled to mass-migrate to Jammu, as the state governor was adamant that in the given circumstances he would not be able to offer protection to the widely dispersed Hindu community. This event created unbridgeable differences between the majority and the minority; each perceived aazadi in a different light.

- Snedden, Christopher (2021), Independent Kashmir: An Incomplete Aspiration, Manchester: Manchester University Press, p. 126, ISBN 978-1-5261-5614-3,

This is because many Pandits have left Kashmir, or felt compelled by militants' violence and antipathy against them to leave, since Muslim Kashmiris began their anti-India uprising in 1988

- Dabla, Bashir Ahmad (2011), Social Impact of Militancy in Kashmir, New Delhi: Gyan Publishing House, p. 98, ISBN 978-81-212-1099-7,

The third migration from rural-urban areas of one place to urban areas of other places involved people who felt compelled to migrate due to political, religious, ethnic, and other such factors. The migration of ... Kashmiri Pandits from Kashmir to different parts of JK state and India in 1990–91 fit in this type of migration.

- Rajput, Sudha G. (4 February 2019), Internal Displacement and Conflict: The Kashmiri Pandits in Comparative Perspective, London and New York: Routledge, ISBN 9780429764622,

The grandfather recalled that the state officials, too, had warned the Pandits that 'not every house could be protected from militants.' In the interest of protecting the family from harm and having reached the 'threshold of tolerance and constant mental abuse inflicted by the militants," the grandfather felt compelled to flee the Valley.

- Hardy, Justine (2009), In the Valley of Mist: Kashmir: One Family in a Changing World, New York and London: The Free Press, p. 63, ISBN 978-1-4391-0289-3,

Children born in Kashmir since 1989 have not heard that song of symbiosis. Just as the young Pandits in the refugee camps have only their parents' memories to portray the homes they felt forced to leave, so, too, do young Kashmir Valley Muslims have only stories and photograph albums as proof of how it used to be before they were born.

- Sokefeld, Martin (2013), "Jammu and Kashmir: Dispute and diversity", in Berger, Peter; Heidemann, Frank (eds.), Anthropology of India: Ethnography, themes, and theory, London and New York: Routledge, p. 91, ISBN 978-0-415-58723-5,

Since the time of Madan's fieldwork. the situation of the Kashmiri Pandits has changed dramatically. Instead of 5 per cent, they now make up less than 2 per cent of the Valley's population. After the beginning of the insurgency, in early 1990, most of the Pandit families left Kashmir for Jammu, Delhi or other places in India. It is still disputed whether the Pandits' exodus was caused by actual intimidation by the (Muslim) militants or whether they were encouraged to leave by the Indian governor Jagmohan, a 'hardliner' who was deputed to Kashmir by the government in Delhi in order to counter the insurgency. Alexander Evans concludes that the Pandits left out of fear, even if not explicitly threatened by the insurgents, and that the administration did nothing to keep them in the Valley (Evans 2002). Since then the ethnography of the Kashmiri Pandits has had to be tuned into the ethnography of exile.

- ^ Duschinski, Haley (2014), "Community Identity of Kashmiri Hindus in the United States", Emerging Voices: Experiences of Underrepresented Asian Americans, Rutgers University Press, p. 132,

Another key point of contention is the community's status as migrants. Kashmiri Hindus are not considered refugees because they have not crossed an international border to seek sanctuary in another country. This means that they are not covered by a well-defined body of international laws and conventions. They would like to be considered Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) because they believe that this designation would give them some leverage to assert their basic rights in their dealings with the Indian state. The government of India refuses to grant them IDP status because it does not want to facilitate international involvement in its internal affairs.<<Footnote 22>> According to this logic, legally classifying the displaced Kashmiri Hindus as IDPs might attract international attention, initiate third-party involvement in the conflict, and prompt international scrutiny of the government's handling of the Kashmir situation. Kashmiri Hindus are thus classified as migrants, meaning that international agencies such as the UN High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) and the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) do not play a role in their situation. Kashmiri Hindus vehemently dispute their classification as migrants because they believe that it carries the connotation that they have left their homeland of their own will, and are able to return freely, without threat of harm.

- ^ Duschinski, Haley (2014), "Community Identity of Kashmiri Hindus in the United States", Emerging Voices: Experiences of Underrepresented Asian Americans, Rutgers University Press, p. 141,

–<<Footnote 22>>: In 1995, the Kashmiri Samiti Delhi issued a petition to the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) demanding that authorities extend to the Kashmiri Pandit community facilities and rights—such as nonrefoulement, humanitarian assistance, and the right to seek asylum—on the basis of their internal displacement. The petition also demanded that the government implement the recommendations of the representative of the UN secretary-general on IDPs and invited the NHRC to meet representatives of the displaced community. The NHRC issued a notice to the state government to respond to the petition. The government, in its response to the NHRC, argued that the Kashmiri Pandits are appropriately described as "migrants" since the word favors the community's return when the situation becomes more conducive. After reviewing the petition and the government's response to it. the NHRC indicated that the Kashmiri Pandits did not meet the typical definition of IDPs in light of the government's benevolent attitude toward them.

- ^

- Bose, Sugata; Jalal, Ayesha (2001), Modern South Asia: History, Culture, Political Economy, London and New York: Routledge, p. 226, ISBN 0-415-16951-8,

In 1989 and the early 1990s a popularly backed armed insurgency was orchestrated by the Jammu and Kashmir Liberation Front, which called for a secular and sovereign Kashmir. Kashmiri cultural and linguistic identity appeared to be more potent than Islamic aspirations or pro-Pakistan sentiment in the Vale of Kashmir. In time, however, the balance of firepower among the rebels shifted to the Hizbul Mujahideen, which received more support from Pakistan. The Indian state deployed more than 550,000 armed personnel in the early 1990s to severely repress the Kashmir movement.

- Staniland, Paul (2014), Networks of Rebellion: Explaing Insurgent Cohesion and Collapse, Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, p. 73–76, ISBN 978-0-8014-5266-6,

The early years of JKLF activity, especially in 1988, involved coordinated, publicly symbolic strikes carried out by a relatively small number of fighters. Central control processes at this point were handled by the four original organizers. Crackdowns by the Indian government spurred mobilization, and "within two years, the previously marginal JKLF emerged as the vanguard and spearhead of a popular uprising in the Kashmir Valley against Indian rule. It dominated the first three years of the insurgency (1990–92)."! Even to the present day, "most commentators agree that among Muslims in the Valley, the JKLF enjoys considerable popular support." This was especially the case in the early 1990s, when contemporary observers argued that "the predominant battle cry in Kashmir is azadi (freedom) and not a merger with Pakistan'"and that "the JKLF, a secular militant group, is by far the most popular. The support for the JKLF was clearly substantial and greater than that of its militant contemporaries. ... In the early years of the war in Kashmir, the JKLF was the center of insurgency, but I will show later in this chapter how the social-institutional weakness of the organization made it vulnerable to targeting by the Indian leadership and dissention from local units. The Hizbul Mujahideen became the most robus organization in the fight in Kashmir. While its rise to dominance occurred after 1990, its mobilization during 1989–1991 through networks of the Jamaat-e-Islami laid the basis for an integrated organization that persisted until it shifted to a vanguard structure in the early to mid-2000s.

- D'Mello, Bernard (2018), India After Naxalbari: Unfinished History, New York: Monthly Review Press, ISBN 978-158367-707-0,

The Kashmir question, centered on the right to national self-determination, cannot be dealt with here, but to cut a long story short, the last nail that the Indian political establishment hammered into the coffin of liberal-political democracy in Kashmir was the rigging of the 1987 state assembly elections there. The Muslim United Front would have electorally defeated the Congress Party-National Conferencecombine if the election had not been rigged. Many of the victims of this political fraud became the leaders of the Kashmir liberation (azaadi) movement. In the initial years, 1988–1992, the movement, led by the Jammu and Kashmir Liberation Front (JKLF), a secular organization, seemed to have unequivocally taken a stand for the independence of J&K from the occupation of India and Pakistan. But for this stand of the JKLF, it had to bear a heavy cost in terms of human lives and sustenance

- Kumar, Radha; Puri, Ellora (2009), "Jammu and Kashmir: Frameworks for a Settlement", in Kumar, Radha (ed.), Negotiation Peace in Deeply Divided Societies: A Set of Simulations, New Delhi, Los Angeles and London: SAGE Publications, p. 292, ISBN 978-81-7829-882-5,

1990–2001: An officially estimated 10,000 Kashmiri youth crossover to Pakistan for training and procurement of arms. The Hizb-ul Mujahedeen (Hizb), which is backed by Pakistan, increases its strength dramatically. ISI favours the Hizb over the secular JKLF and cuts off financing to the JKLF and in some instances, provides intelligence to India against the JKLF. In April 1991, Kashmiris hold anti-Pakistan demonstrations in Srinagar following killing of a JKLF area commander by the Hizb. In 1992, Pakistani forces arrest 500 JKLF marchers led by Amanullah Khan in Pakistan held Kashmir (PoK) to prevent a bid to cross the border. India also uses intelligence from captured militants. JKLF militancy declines.

- Phillips, David L. (8 September 2017), From Bullets to Ballots: Violent Muslim Movements in Transition, London and New York: Routledge, ISBN 9781351518857,

Consistent with the concept of Kashmiriyat, the JKLF was essentially a secular organization that aspired to the establishment of an independent Kashmir where both Muslims and Hindus would be welcome. This ideal is anathema to Pakistan-based fundamentalists as well as to Afghan and Arab fighters who care far less about Kashmiri self-determination than they do about establishing Pakistani rule and creating an Islamic caliphate in Srinagar.

- Morton, Stephen (2008), Salman Rushdie: Fictions of Postcolonial Modernity, New British Fiction, Houndmills and New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 143–144, ISBN 978-1-4039-9700-5,

Yet if General Kachhwaha's military campaign of terror against Kashmiri Muslims in the Valley of Kashmir gives the lie to Nehru's legacy of secularism and tolerance by exposing the hegemonic and military power of India's Hindu majority, Rushdie's account of the secular nationalism of the Jammu Kashmir liberation front in Shalimar the Clown seems to embody what the postcolonial theorist Homi K. Bhabha calls subaltern secularism (Bhabha 1996). For the secular nationalism of the Jammu and Kashmir liberation front (JKLF) is precisely subaltern in the sense that it reflects the view of the Kashmiri people rather than the elite, a people 'of no more than five million souls, landlocked, preindustrial, resource rich but cash poor, perched thousands of feet up in the mountains'

- Tompkins, Paul J. Jr. (2012), Crossett, Chuck (ed.), Casebook on Insurgency and Revolutionary Warfare, Volume II, 1962–2009, Fort Bragg: United States Army Special Operations Command and The Johns Hopkins University/Applied Physics Laboratory, pp. 455–456, OCLC 899141935,

More than the relatively simple denial of civil and political rights that characterized the Kashmiri government for more than four decades, the events of 1990, when Governor Jagmohan and the Indian government stepped up their counterinsurgency efforts, developed into a pronounced human rights crisis"—there were rampant abuses such as unarmed protestors shot indiscriminately, arrests without trial, and the rape and torture of prisoners. Jagmohan whitewashed the security forces' role in human rights violations, laying the blame for atrocities at the feet of "terrorist forces. In February, he also dissolved the Assembly. Combined with the severe, indiscriminate harassment of the population, whereby all citizens were treated as potential suspects, the January massacre, and Jagmohan's draconian policies, support for the JKLF skyrocketed!"... However, it was JKLF, an ostensible secular, pro-independence movement, that dominated the field at the onse of the insurgency.

- Bose, Sugata; Jalal, Ayesha (2001), Modern South Asia: History, Culture, Political Economy, London and New York: Routledge, p. 226, ISBN 0-415-16951-8,

- ^ a b

- Lapidus, Ira A. (2014), A History of Islamic Societies (3 ed.), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 720, ISBN 978-0-521-51430-9,

By the mid-1980s, however, trust between Delhi and local leaders had again broken down, and Kashmiris began a fully fledged armed insurgency led by the Jammu and Kashmir Liberation Front calling for an independent and secular Kashmir. As the military struggle went on, Muslim—Hindu antagonism rose; Kashmiris began to define themselves in Muslim terms. Pro-Muslim and pro-Pakistan sentiment became more important than secularism, and the leadership of the insurgency shifted to the Harakat and the Hizb ul-Mujahidin. To achieve its strategic objectives the Pakistani military and its intelligence services supported militant Islamist groups such as Lashkar-e-Taiba and Jaish-e-Mohammed, who attacked Indian security forces in Jammu and Kashmir and more recently attacked civilians in India. Saudi influences, more militant forms of Islam, and the backing of the Pakistani intelligence services gave the struggle in Kashmir the aura of a jihad. The fighting escalated with the deployment of more than 500,000 Indian soldiers to suppress the resistance.

- Metcalf, Barbara D.; Metcalf, Thomas R. (2012), A Concise History of Modern India, Cambridge Concise Histories (3 ed.), Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 308–309, ISBN 978-1-107-02649-0,

The imposition of leaders chosen by the centre, with the manipulation of local elections, and the denial of what Kashmiris felt was a promised autonomy boiled over at last in the militancy of the Jammu and Kashmir Liberation Front, a movement devoted to political, not religious, objectives. ...As the government sought to locate 'suspects' and weed out Pakistani 'infiltrators', the entire population was subjected to a fierce repression. By the end of the 1990s, the Indian military presence had escalated to approximately one soldier or paramilitary policeman for every five Kashmiris, and some 30,000 people had died in the conflict.

- Varma, Saiba (2020), The Occupied Clinic: Militarism and Care in Kashmir, Durham and London: Duke University Press, p. 27, ISBN 9781478009924, LCCN 2019058232,

In 1988, the JKLF, an organization with secular, leftist roots, waged a guerrilla war against Indian armed forces with the slogan Kashmir banega khudmukhtar (Kashmir will be independent). Other organizations, such as the Jama'at Islami and Hizbul Mujahideen (HM), supported merging with Pakistan. In 1988, Kashmiris began an armed struggle to overthrow Indian rule. Because some armed groups received assistance from Pakistan, the Indian state glossed the movement as Pakistani-sponsored "cross-border terrorism," while erasing its own extralegal actions in the region. Part of India's claim over Kashmir rests on its self-image as a pluralistic, democratic, and secular country. However, many Kashmiris feel they have never enjoyed the fruits of Indian democracy, as draconian laws have been in place for decades. Further, many see Indian rule as the latest in a long line of foreign colonial occupations.

- Sirrs, Owen L. (2017), Pakistan's Inter-Services Intelligence Directorate: Covert action and internal operations, London and New York: Routledge, p. 157, ISBN 978-1-138-67716-6, LCCN 2016004564,

Fortunately for ISI, another option emerged from quite unexpected direction: the Jammu and Kashmir Liberation Frong (JKLF). A creature of its times, the JKLF was guided by a secular, nationalistic ideology, which emphasized the independenc of Kashmir above union with Pakistan or India. This fact alone meant that JKLF was not going to be a good match for ISI's long-term goal of a united Kashmir under the Pakistan banner. Still, in lieu of any viable alternative, the JKLF was the best short-term expedient for ISI plans.

- Webb, Matthew J. (2012), Kashmir's Right to Secede: A Critical Examination of Contemporary Theories of Secession, London and New York: Routledge, p. 44, ISBN 978-0-415-66543-8,

The first wave of militancy from 1988 through to 1991 was very much an urban, middle-class affair dominated by the secular, pro-independence Jammu and Kashmir Liberation Front (JKLF).

- Thomas, Raju G. C, ed. (4 June 2019), Perspectives On Kashmir: The Roots of Conflict in South Asia, London and New York: Routledge, ISBN 978-0-367-28273-8,

The exception in this case, which is also the largest group among the nationalists, is the Jammu and Kashmir Liberation Front (JKLF). The JKLF claims to adhere to the vision of a secular independent Kashmir. ... The JKLF committed to an independent but secular Kashmir, is willing to take the Hindus back.

- Chandrani, Yogesh; Kumar, Radha (2003), "South Asia: Introduction", The Selected Writings of Eqbal Ahmad, New York and Oxford: Columbia University Press, p. 396, ISBN 0-231-12711-1,

Decades of misrule and repression in Indian-held Kashmir had led to a popular and armed uprising in 1989. In its initial stages, the uprising was dominated by the Jammu Kashmir Liberation Front (JKLF), a secular movement that demanded Kashmir's independence from Indian rule. The Indian government deployed the army and brutally suppressed the uprising. The Pakistani security establishment at first supported the JKLF and then began to seek more pliable allies.

- Sokefeld, Martin (2012), "Secularism and the Kashmir dispute", in Bubandt, Nils; van Beek, Martijn (eds.), Varieties of Secularism in Asia: Anthropological Explorations of Religion, Politics, and the Spiritual, London and New York: Routledge, p. 101–120, 109, 114, ISBN 978-0-415-61672-0,

(p. 109) Like the Plebiscite Front, the JKLF portrayed the Kashmir issue as a national issue and Kashmir as a multi-religious nation to which Muslims, Hindus and members of other religions belonged. While Pakistan was considered as a 'friend' of the Kashmiri nation, the purpose of the JKLF was not accession with the state but the independence of Kashmir from both India and Pakistan. In the mid-1980s, the JKLF became a significant force among (Azad) Kashmiris in Britain. Towards the end of the decade, with the support of Pakistani intelligence agencies, the JKLF extended into Indian administered Kashmir and initiated the uprising there. (p. 114) In writings about the Kashmir dispute, secular political mobilisation of Muslim Kashmiris is frequently disregarded. Even when it is mentioned it is often not taken seriously. ... The Kashmir issue is much more complex than the orthodox view on the problem concedes. It is neither simply a conflict between India and Pakistan nor an issue between religion/Islam on the one hand and secularism on the other. ... In the 1980s and early 1990s Kashmiri nationalists, especially those of the JKLF, considered Pakistan a kind of natural ally for their purposes. But when Pakistani agencies shifted their support to Islamist militants ('jihadis') in Kashmir, most nationalists were alienated from Pakistan.

- Sharma, Deepti (2015), "The Kashmir insurgency: multiple actors, divergent interests, institutionalized conflict", in Chima, Jugdeep S. (ed.), Ethnic Subnationalist Insurgencies in South Asia: Identiies, interests and challenges to state authority, London and New York: Routledge, pp. 17–40, 27–28, ISBN 978-1-138-83992-2,

The JKLF, with its indigenous roots, had insider credentials and its secular ideology appealed to a population that had learned to equate ethnic nationalism with Sheikh Abdullah's version of Kashmiriyat. After the insurgency was in full swing, the Islamist groups made progress with their superior experience in militancy and greater resources. At this point, the JKLF's secular ideology and its popularity became an obstacle in their path to complete control of the insurgency. In 1992, Pakistan arrested more than 500 JKLF members, including Amanullah Khan, a JKLF leader in PoK. It is alleged that Pakistan also provided intelligence on JKLF members to the Indian military, which led to the JKLF members being either arrested or killed.

- Lapidus, Ira A. (2014), A History of Islamic Societies (3 ed.), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 720, ISBN 978-0-521-51430-9,

- ^ a b

- Ganguly, Sumit (2016), Deadly Impasse: Indo-Pakistani Relations at the Dawn of a New Century, Cambridge University Press, p. 10, ISBN 9780521125680,

In December 1989, an indigenous, ethno-religious insurgency erupted in the Indian-controlled portion of the disputed state of Jammu and Kashmir.

- Ganguly, Sumit (1997), The Crisis in Kashmir: Portents of War; Hopes of Peace, Woodrow Wilson Center Press and Cambridge University Press, pp. 107–108, ISBN 9780521655668,

However, two factors undermined the sense of security and safety of the pandit community in Kashmir. First, the governor hinted that the safety and security of the Hindu community could not be guaranteed. Second, the fanatical religious zeal of some of the insurgent groups instilled fear among the Hindus of the valley. By early March, according to one estimate, more than forty thousand Hindu inhabitants of the valley had fled to the comparative safety of Jammu.

- Ganguly, Sumit (2016), Deadly Impasse: Indo-Pakistani Relations at the Dawn of a New Century, Cambridge University Press, p. 10, ISBN 9780521125680,

- ^ Evans 2002, pp. 19–37, 23: "사망자와 부상자의 수는 적었지만, 1988년에서 1990년 사이의 호전적인 공격은 판디트 공동체에 공황을 야기했습니다.양측의 극단주의 선전에 힘입은 공포와 임박한 문제의식이 팽배했습니다.1990년 3월 말, ASKPC(All India Kashimi Pandit Conference)는 판디트가 '잠무로 이동'하는 것을 도와줄 것을 행정부에 호소하고 있었습니다.

- ^ Hussain, Shahla (2018), "Kashmiri Visions of Freedom", Kashmir: History, Politics, Representation, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, pp. 89–112, 105, ISBN 9781107181977,

The rhetoric of aazadi did not hold the same appeal for the minority community. The rise of insurgency in the region created a difficult situation for the Kashmiri Hindu community, which had always taken pride in their Indian identity.

- ^ Hussain, Shahla (2018), "Kashmiri Visions of Freedom", Kashmir: History, Politics, Representation, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, pp. 89–112, 105, ISBN 9781107181977,

The community felt threatened when Kashmiri Muslims under the flag of aazadi openly raised anti-India slogans. The 1989 targeted killings of Kashmiri Hindus who the insurgents believed were acting as Indian intelligence agents heightened those insecurities.

- ^ Evans 2002, pp. 19-37, 23: "KP들은 정당한 두려움을 통해 집단으로 이동했습니다.1989년과 1990년의 살인 사건과 1990년 초의 폭력적인 상황에서 소문이 빠르게 퍼졌던 방식을 고려할 때, KP들은 직접적인 위협만큼 불확실성에 의해 겁을 먹었을까요?사태가 전개되면서 집단적인 불안감이 감돌았습니다.사망자와 부상자의 수는 적었지만, 1988년에서 1990년 사이의 호전적인 공격은 판디트 공동체 내에 공황을 야기시켰습니다.양측의 극단주의 선전에 힘입은 공포와 임박한 문제의식이 팽배했습니다.1990년 3월 말, ASKPC(All India Kashimi Pandit Conference)는 판디트가 '잠무로 이동'하는 것을 도와줄 것을 행정부에 호소하고 있었습니다.

- ^ Hussain, Shahla (2018), "Kashmiri Visions of Freedom", Kashmir: History, Politics, Representation, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, pp. 89–112, 105, ISBN 9781107181977,

In the winter of 1990, the community felt compelled to mass-migrate to Jammu, as the state governor was adamant that in the given circumstances he would not be able to offer protection to the widely dispersed Hindu community. This event created unbridgeable differences between the majority and the minority; each perceived aazadi in a different light.

- ^ Evans 2002, pp. 19–37, 23: "파키스탄의 책임을 추궁하는 다수의 잠무 KP들과의 인터뷰는 인종청소나 심지어 대량학살 의혹을 시사합니다.이미 설명된 두 가지 음모론은 증거에 기초한 것이 아닙니다.수만트라 보스가 관찰한 바와 같이, 수많은 힌두교 성지들이 파괴되고 판디트들이 살해되었다는 라쉬트리야 스와얌 세바크 출판물들의 주장은, 많은 성지들이 훼손되지 않은 채로 남아 있고, 많은 사상자들이 근거가 없는 채로 남아 있다는 점에서, 대부분 거짓입니다."

- ^ Bose, Sumantra (2021), Kashmir at the Crossroads: Inside a 21st-century conflict, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, p. 122, ISBN 978-0-300-25687-1,

In 1991 the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), the movement's parent organisation, published a book titled Genocide of Hindus in Kashmir.<Footnote 38: Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, Genocide of Hindus in Kashmir (Delhi: Suruchi Prakashan, 1991).> It claimed among many other things that at least forty Hindu temples in the Kashmir Valley had been desecrated and destroyed by Muslim militants. In February 1993 journalists from India's leading newsmagazine sallied forth from Delhi to the Valley, armed with a list of twenty-three demolished temples supplied by the national headquarters of the BJP, the movement's political party. They found that twenty-one of the twenty-three temples were intact. They reported that 'even in villages where only one or two Pandit families are left, the temples are safe . . . even in villages full of militants. The Pandit families have become custodians of the temples, encouraged by their Muslim neighbours to regularly offer prayers.' Two temples had sustained minor damage during unrest after a huge, organised Hindu nationalist mob razed a sixteenth-century mosque in the north Indian town of Ayodhya on 6 December 1992.<Footnote 39: India Today, 28 February 1993, pp.22–25>

- ^ Bhatia, Mohita (2020), Rethinking Conflict at the Margins: Dalits and Borderland Hindus in Jammu and Kashmir, Cambridge, UK and New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 123–124, ISBN 978-1-108-83602-9,

The dominant politics of Jammu representing 'Hindus' as a homogeneous block includes Padits in the wider 'Hindu' category. It often uses extremely aggressive terms such as 'genocide' or 'ethnic cleansing' to explain their migration and places them in opposition to Kashmiri Muslims. The BJP has appropriated the miseries of Pandits to expand their 'Hindu' constituency and projects them as victims who have been driven out from their homeland by militants and Kashmiri Muslims.

- ^ Rai, Mridu (2021), "Narratives from exile: Kashmiri Pandits and their construction of the past", in Bose, Sugata; Jalal, Ayesha (eds.), Kashmir and the Future of South Asia, Routledge Contemporary South Asia Series, Routledge, pp. 91–115, 106, ISBN 9781000318845,

Among those who stayed on is Sanjay Tickoo who heads the Kashmiri Pandit Sangharsh Samiti (Committee for the Kashmiri Pandits' Struggle). He had experienced the same threats as the Pandits who left. Yet, though admitting 'intimidation and violence' directed at Pandits and four massacres since 1990, he rejects as 'propaganda' stories of genocide or mass murder that Pandit organizations outside the Valley have circulated.

- ^ Hussain, Shahla (2021), Kashmir in the Aftermath of the Partition, Cambridge University Press, pp. 320, 321, ISBN 9781108901130,

The Counter-narrative of Aazadi: Kashmiri Hindus and Displacement of the Homeland (p. 320) The minority Hindu community of the Valley, which had always presented itself as a group of true Indian patriots wedded to their Indian identity, now found itself in an extreme dilemma as the tehreek-i-aazadi threatened their security. The community felt safer as a part of Hindu-majority India, as it feared political domination in Muslim-majority Kashmir. It had thus often opposed Kashmiri Muslim calls for self-determination, equating this with anti-nationalism.

- ^ Rai, Mridu (2021), "Narratives from exile: Kashmiri Pandits and their construction of the past", in Bose, Sugata; Jalal, Ayesha (eds.), Kashmir and the Future of South Asia, Routledge Contemporary South Asia Series, Routledge, pp. 91–115, 106, ISBN 9781000318845,

An important element in the recollections of many Pandits is the effect the killing in the early 1990s of a number of Pandit officials had in shaking their sense of security. Various groups of militants claim that their targets were Indian government 'agents' and so, in eliminating them, they were essentially waging war against the state. Contrariwise, Pandits insist that the targets being exclusively Hindu indicated a 'communal' threat. It is only common sense that not every Pandit could have been an informer or a spy. But what is perplexing is that while the connection of numerous Pandits with the state's intelligence apparatus is denied in discussions relating to their roles in Kashmir, it is well advertised when making demands upon the state's resources in Indian law courts. The latter became an important arena for shaping Pandit narratives. ... At any rate, these testimonies freely given in Indian courts corroborate the claim of militants that at least some Pandits did act as agents of the state in Kashmir; of course, this does not offer justification for killing them.

- ^ Bose, Sumantra (2021), Kashmir at the Crossroads, Inside a 21st-Century Conflict, Yale University Press, pp. 119–120,

JKLF's series of targeted assassinations that began in August 1989 (see Chapter 1) included a number of prominent Pandits. Tika Lal Taploo, the president of the Hindu nationalist BJP's Kashmir Valley unit, was killed in September 1989, followed in November by Neelkanth Ganjoo, the judge who had sentenced the JKLF pioneer Maqbool Butt to death in 1968 (the execution was carried out in 1984). As the Valley descended into mayhem in early 1990, Lassa Koul, the Pandit director of the Srinagar station of India's state-run television, was killed on 13 February 1990 by JKLF gunmen. The murders of such high-profile members of the community may have spread a wave of fear among Pandits at large.

- ^ Snedden, Christopher (2021), Independent Kashmir: An Incomplete Aspiration, Manchester University Press, p. 132, ISBN 9781526156150,

Some other slogans were clearly directed against pro-India Kashmiri Pandits. ... by the end of January 1990, loudspeakers in Srinagar mosques were broadcasting slogans like 'Kafiron Kashmir chhod do [Infidels, leave our Kashmir]

- ^ Zutshi, Chitralekha (8 November 2017). Kashmir: History, Politics, Representation. Cambridge University Press. p. 230. ISBN 978-1-108-40210-1.

Anti-Hindu announcements in neighbourhood mosques, such as, 'Kashmir kiske liye? Mussalman ke liye' (Kashmir is for whom? For the Muslim), resulted in a large, almost total exodus of most of the Valley's Hindu (Pandit) population.

- ^ Hussain, Shahla (2021), Kashmir in the Aftermath of the Partition, Cambridge University Press, pp. 320, 321, ISBN 9781108901130,

The polarized political positions that the two communities had adopted since 1947 reached a breaking point in the new political climate of the 1990s, when Kashmiri Muslims openly invoked anti-India slogans and demanded aazadi. As the new valorization of armed resistance gripped the region, targeted killings of prominent members of the Kashmiri Hindu community whom the JKLF insurgents believed to be Indian intelligence agents sent shivers down the spine of the minority community. Stories of Kashmiri Pandits, branded as "informers," and killed in their own homes or in their alleys, and survived by grieving wives and children, had a tremendous impact on the psyche of the minority community. Their fears were heightened as religious slogans merged with the cry for independence emerging from the mosques of Kashmir. Certain militant groups even wrote threatening letters to the Kashmiri Hindu community, asking them to leave the Valley.

- ^ Evans 2002, p.23: "P.S. Verma는 이를 반영합니다. 이주자 Pandits와의 인터뷰에서 실제로 개인적으로 해를 입거나 계곡을 떠나겠다는 위협을 받은 사람은 거의 발견되지 않았습니다. (그리고 무슬림 이웃들에게 남아달라고 간청했던 많은 사람들).2001년 잠무 대학의 정치학과 대학원생들이 실시한 조사 연구는 조사 대상 KP의 2%가 위협적인 편지를 받은 적이 있다는 것을 발견했지만, 80% 이상은 어떠한 형태의 직접적인 위협도 받지 못했습니다.그럼에도 불구하고, 베르마가 말했듯이, 이 이주민들의 대부분은 '특히 1990년 1월부터 2월까지 대탈출이 일어난 동안, 가라앉지 않는 폭력의 분위기 속에서 매우 큰 위협을 느꼈다'.파키스탄의 책임을 추궁하고 있는 잠무의 많은 KP들과의 인터뷰는 인종청소나 대량학살 의혹을 제기하고 있습니다."

- ^ Data 2017, p. 61–63: "카슈미르에서 일어난 사건들에 대한 대부분의 설명은 인도 국가에 대한 전투성과 시위를 특징으로 하지만, 판디트에 대한 언급은 거의 없습니다.판디트가 말하는 구호는 그 당시 공식적으로 보도되거나 기록된 적이 없으며, 기록된 것과 판디트가 묘사하는 것 사이의 간극을 암시합니다.그러나 [카슈미르 무슬림들과의] 대화는 [카슈미르 무슬림들과의] 판디트들이 무슬림들의 표적이 아니라는 그들의 주장 때문에 복잡해졌습니다.그들은 팬디트가 주목하는 시위에서 여성들을 위협하는 구호를 들은 것을 부인했습니다."p.63)."

- ^ Evans 2002, p. 20: "대부분의 KP들은 파키스탄과 무장 단체들에 의해, 또는 공동체로서 카슈미르 무슬림들에 의해, 카슈미르 계곡에서 쫓겨났다고 믿고 있습니다.후자의 변종을 대표하는 파렐랄 카울은 판디트 이탈이 힌두교 신자들을 계곡에서 쫓아내기 위한 무슬림들의 집단적인 협박의 명백한 사례라고 주장합니다.모스크는 경고의 중심지로 사용되었습니다.힌두교인들을 위협하고 테러범들과 카슈미르의 많은 이슬람교도들이 이루고 싶어하는 것을 그들에게 전달하는 것.'"

- ^ Verma, Saiba (2020), The Occupied Clinic: Militarism and Care in Kashmir, Duke University Press, p. 26, ISBN 9781478012511,

Although Kashmiri Muslims did not support violence against religious minorities, the exodus of Kashmiri Pandits (who are Hindus) and their unresolved status continues to be a pain often "weaponized" by the Indian state to cast Kashmiris Muslims as Islamic radicals.

- ^ Zutshi, Chitralekha (2019), Kashmir, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-099046-6,

These developments subverted the popular nature of the insurgency, tarnishing the very real political grievances that underlay it with the brush of criminality and Islamic radicalism.

- ^ Verma, Saiba (2020), The Occupied Clinic: Militarism and Care in Kashmir, Duke University Press, p. 62, ISBN 9781478012511,

Soon after Jammu and Kashmir became a disturbed area in 1990, the change registered in the landscape. Armed forces occupied protected forests, temples, orchards, and gardens. Cricket grounds became desiccated ovals in the middle of the city. Historical sites became interrogation centers; cinemas became military bunkers. Counterinsurgency tactics, such as sieges, crackdowns, and cordon-and-search operations, transformed village after village. Checkpoints, roadblocks, and identity checks became everyday realities.

- ^ Bhan, Mona; Duschinski, Haley; Zia, Ather (20 April 2018), "Introduction. 'Rebels of the Streets': Violence, Protest, and Freedom in Kashmir", in Duschinski, Haley; Bhan, Mona; Zia, Ather; Mahmood, Cynthia (eds.), Resisting Occupation in Kashmir, University of Pennsylvania Press, pp. 25–27, ISBN 9780812249781,

. Their stories of departure are deeply contested; while many in Kashmir view their departure from Kashmir as Governor Jagmohan Malhotra' grand design to exterminate Muslims once Kashmir's Hindu minority had fled the valley, many Kashmiri Pandits track the onset of Kashmir's armed rebellion in 1989 to a new brand of Islamic extremism, which in their view posed a grave threat to Kashmir's Hindu minority (Duschinski 2008).

- ^ Hussain, Shahla (2021), Kashmir in the Aftermath of the Partition, Cambridge University Press, pp. 320, 321, ISBN 9781108901130,

In this violent and unstable atmosphere, rumors spread that the exodus of Kashmiri Hindus was the machinations of the state governor who planned to use unrestrained force to suppress Kashmiri Muslim resistance and thus viewed the presence of the Kashmiri Hindus in the neighborhoods as a hindrance to the army in quickly and efficiently carrying out its plan.'!" Many Kashmiri Muslims claimed to have "witnessed departing Pandits boarding vehicles organized by the state," and felt fearful about their own security. A senior Indian administrator, Wajahat Habibullah, posted in Kashmir at this critical juncture, denied the involvement of the government in a coordinated plan for Kashmiri Hindu departure. However, he emphasized that the state governor did little to stop the Pandits from leaving the Valley. Jagmohan remained adamant that he would not be able to offer protection to the Valley's widely dispersed Hindu community, and rejected Habibullah's suggestion to televise "the request of hundreds of Muslims to their Pandit compatriots not to leave the valley." Instead, the government reassured Pandits of their support in settling them in refugee camps in Jammu and paying the civil servants their salaries, if the community decided to leave

- ^ Evans 2002, p. 22: "1990년에 일어난 일에 대한 세 번째 가능한 설명이 있습니다. 그것은 일어난 일의 심각성을 인정하지만 무엇이 KP 이주를 촉발했는지를 주의 깊게 조사하는 것입니다. KP들은 합법적인 두려움을 통해 집단으로 이주했습니다.1989년과 1990년의 살인 사건과 1990년 초의 폭력적인 상황에서 소문이 빠르게 퍼졌던 방식을 고려할 때, KP들은 직접적인 위협만큼 불확실성에 의해 겁을 먹었을까요?사태가 전개되면서 집단적인 불안감이 감돌았습니다.사망자와 부상자의 수는 적었지만, 1988년에서 1990년 사이의 호전적인 공격은 판디트 공동체 내에 공황을 야기시켰습니다.양측의 극단주의 선전에 힘입은 공포와 임박한 문제의식이 팽배했습니다.1990년 3월 말, ASKPC는 판디트가 '잠무로 이동'하는 것을 도와달라고 행정부에 호소했습니다.주로 인도 통치를 목표로 했지만 이슬람 국가에 대한 요구와 함께 밸리의 일부 이슬람 과격분자들의 공개적인 수사는 KP들의 간담을 서늘하게 만들었습니다.이것은 차례로 탈출을 촉발시켰는데, 이것은 자그모한 주지사 정부(재임 기간 동안 거의 90%의 이탈이 발생했습니다)에 의해 적극적으로 대항하지 않았습니다."

- ^ Evans 2002, p. 23: "정부가 KP 고위 관리들을 보호할 수 없고 부재 시 급여를 지급할 것이라는 것이 확실해지자, 주 고용에 있는 다른 KP들은 자리를 옮기기로 결정했습니다.처음에 이 이주민들 중 몇 달 이상 망명이 지속될 것으로 예상한 이들은 거의 없었습니다."

- ^ Hussain, Shahla (2021), Kashmir in the Aftermath of the Partition, Cambridge University Press, p. 323, ISBN 9781108901130,

Interestingly, themes of omission, anger, and betrayal are absent from the narratives of those Kashmiri Pandits who stayed in the Valley and refused to (p. 323) migrate. Even though life was extremely difficult without the support of their own community, their stories emphasize human relationships that transgressed the religious divide, and highlighted the importance of building bridges between communities. Pandits' experience of displacement varied depending on their class status. While the urban elite found jobs in other parts of India, lower-middle-class Hindus, especially those from rural Kashmir, suffered the most, many living in abject poverty. The local communities into which they migrated saw their presence as a burden, generating ethnic tensions between the "refugees" and the host community.' Adding to the tension, Kashmiri Hindus from the Valley, mostly Brahmans, had their own social and religious practices that differed from the Hindus of Jammu. They wanted to retain their own cultural and linguistic traditions, which made it difficult for them to assimilate into Jammu society.

- ^ Rai, Mridu (2021), "Narratives from exile: Kashmiri Pandits and their construction of the past", in Bose, Sugata; Jalal, Ayesha (eds.), Kashmir and the Future of South Asia, Routledge Contemporary South Asia Series, Routledge, pp. 91–115, 106, ISBN 9781000318845,

According to the Indian home ministry's annual report for 2009–10, 20 years after the exodus, there were 57,863 Pandit refugee families, of whom 37,285 resided in Jammu, 19,338 in Delhi, and 1,240 in other parts of the country. Countless writers have described the miserable conditions of the Pandits living in camps, especially those who are still languishing in those established in and around Jammu. Unwelcomed by their host communities, entirely deprived of privacy and basic amenities, many succumbed to depression, ageing-related diseases, and a sense of desperate helplessness. Needless to say, there were some who fared better – those with wealth and older connections – but for those many others with none of these advantages, it was as being plunged with no safety net. Ever since 1990, Indian politicians promised much and delivered next to nothing for the camp-dwellers.

- ^ Metcalf & Metcalf 2006, p. 274: "그들의 대의는 힌두 우파에 의해 빠르게 받아들여졌습니다."

- ^ Hussain, Shahla (2021), Kashmir in the Aftermath of the Partition, Cambridge University Press, p. 323, ISBN 9781108901130,

The Pandits' situation was further complicated by the indifference of Indian political parties, especially the Congress and the 1989-90 National Front government.' Kashmiri Pandits perceived themselves as "true patriots" who had "sacrificed greatly for their devotion to the Indian nation." As such, they saw the inability of the state to provide support in exile as a moral failure and a betrayal. This vacuum was filled by Hindu rightist groups, who, while advocating for Kashmiri Pandits, preyed on their insecurities and further alienated them from Kashmiri Muslims.

- ^ Hussain, Shahla (2021), Kashmir in the Aftermath of the Partition, Cambridge University Press, p. 323, ISBN 9781108901130,

Some Kashmiri Pandits adopted a radical approach and organized the "Panun Kashmir" (Our Own Kashmir) movement, demanding a homeland carved out from the Valley. Panun Kashmir claimed that the entire Valley had originally been inhabited by Hindus, giving them a right to it in the present. The movement argued that to prevent the total disintegration of India, Kashmiri Pandits "who have been driven out of Kashmir in the past" or "who were forced to leave on account of the terrorist violence in Kashmir" should be given their own separate homeland in the Valley. The movement's slogan was "Save Kashmiri Pandits, Save Kashmir, and Save India. Kashmiri Hindus, according to its leaders, had borne the cross of Indian secularism for several decades and their presence had played a major role in the restoration of the Indian claim on Kashmir. The organization warned India that restoring any form of autonomy to the state would indirectly mean conceding the creation of an Islamic state. As historian Mridu (p. 324) Rai has argued, ironically, while "Panun Kashmir opposes demands for Aazadi as an illegitimate demand of Islamist separatists, their own territorial claims are no less separatist." The exclusionary nature of their organization was immediately visible from their maps, which depicted a Valley denuded of Muslim religious sites. As Rai argues, maps such as Panun Kashmir's are "fashioned to enable easy pleating into that of India, the status quo power in the Valley."

- ^ Bhan, Mona; Duschinski, Haley; Zia, Ather (2018), "Introduction. 'Rebels of the Streets': Violence, Protest, and Freedom in Kashmir", in Duschinski, Haley; Bhan, Mona; Zia, Ather; Mahmood, Cynthia (eds.), Resisting Occupation in Kashmir, University of Pennsylvania Press, p. 26, ISBN 9780812249781,