아시아계 미국인

Asian Americans 아시아계 미국인의 군별 분포 | |

| 총인구 | |

|---|---|

| 인구의 7.2% (2020년)[1] 중국계 미국인: 5,143,982명 인도계 미국인: 4506,308명 필리핀계 미국인: 4,089,570명 베트남계 미국인: 2,162,610명 한국계 미국인: 1,894,131명 일본계 미국인: 1,542,195명 대만계 미국인: 900,595명[2] 파키스탄계 미국인: 526,956명 태국계 미국인: 329,343명 Hmong American: 320,164명 캄보디아계 미국인: 300,360명 라오스계 미국인: 262,229명 홍콩계 미국인: 248,024명[3] 인도-캐리비안계 미국인: 232,817명[4] 방글라데시계 미국인: 213,372명의 버마계 미국인: 189,250명 네팔계 미국인: 175,005명 인도네시아계 미국인: 116,869명 카렌 아메리칸: 64,759명 스리랑카계 미국인: 61,416명 아이유 미엔 미국인: 5만명[5] 말레이시아계 미국인: 38,277명 인도-피지안계 미국인: 30,890명 티베트계 미국인: 26,700명 부탄계 미국인: 23,316명[6] 몽골계 미국인: 19,170명 칼미크 아메리카인: 3,000명[7] | |

| 인구가 많은 지역 | |

| 캘리포니아 | 7,045,163 |

| 뉴욕 | 2,173,719 |

| 텍사스 주 | 1,849,226 |

| 뉴저지 주 | 1,046,732 |

| 워싱턴 | 939,846 |

| 일리노이 주 | 875,488 |

| 플로리다 주 | 843,005 |

| 하와이 | 824,143 |

| 버지니아 주 | 757,282 |

| 펜실베이니아 주 | 603,726 |

| 매사추세츠 주 | 582,484 |

| 언어들 | |

| 종교 | |

| 크리스찬(42%) 무소속(26%) 불교(14%) 힌두어(10%) 무슬림(4%) 시크(1%) 자인, 조로아스터교, 텡그리교, 신도, 중국 민간종교(도교와 유교), 베트남 민간종교[8] 등 기타 2% | |

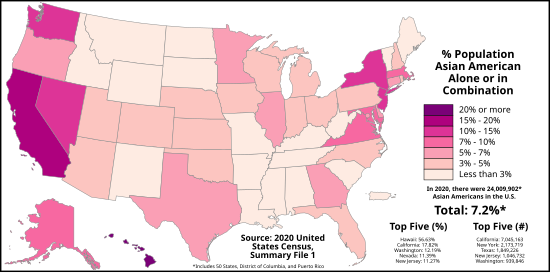

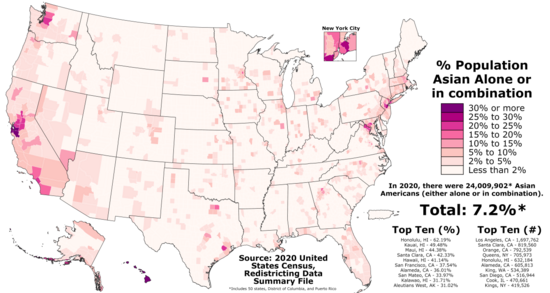

아시아계 미국인(Asian Americans)은 아시아계 미국인(아시아의 특정 지역에서 온 이민자 및 그러한 이민자의 후손인 귀화 미국인 포함)입니다.[9] 이 용어는 역사적으로 아시아 대륙의 모든 토착민들에게 사용되었지만, 미국 인구조사국에 의한 "아시아인"이라는 용어의 사용은 극동, 동남아시아 및 인도 아대륙[10] 출신 또는 혈통을 가진 사람들만을 포함하고 아시아의 특정 지역에서 민족적 기원을 가진 사람들은 제외하고, 지금은 중동계 미국인으로 분류되는 서아시아를 포함해서 말입니다.[11][12] "아시아" 인구 조사 범주에는 인구 조사에 인종을 "아시아인"으로 표시하거나 "중국인, 인도인, 방글라데시인, 필리핀인, 베트남인, 인도네시아인, 한국인, 일본인, 파키스탄인, 말레이시아인 및 기타 아시아인"과 같은 항목을 보고한 사람이 포함됩니다.[13] 2020년 미국 인구의 7.2%는 아시아계(1988만6049명) 또는 다른 인종(411만4949명)과 함께 아시아계로 분류되었습니다.[14]

아시아계 미국인 인구는 중국계, 인도계, 필리핀계가 각각 500만 명, 430만 명, 400만 명으로 가장 많습니다. 이 숫자들은 전체 아시아계 미국인 인구의 23%, 20%, 18%, 즉 미국 전체 인구의 1.5%와 1.2%에 해당합니다.[15]

아시아에서 온 이민자들은 17세기부터 현대 미국의 일부에 있었지만, 대규모 이민은 19세기 중반까지 시작되지 않았습니다. 1880년대에서 1920년대 사이에 원주민들의 이민법은 다양한 아시아 집단들을 배제했고, 결국 거의 모든 아시아인들의 미국 대륙으로의 이민을 금지했습니다. 1940년대에서 1960년대 사이에 이민법이 개혁되고, 국가 출신 할당제가 폐지된 후, 아시아 이민이 빠르게 증가했습니다. 2010년 인구조사의 분석에 따르면 아시아계 미국인은 미국에서 가장 빠르게 성장하고 있는 인종 집단입니다.[16]

용어.

다른 인종과 민족에 기반을 둔 용어들과 마찬가지로, 공식적이고 일반적인 용법은 이 용어의 짧은 역사를 통해 현저하게 변화했습니다. 1960년대 후반 이전에는 다양한 아시아 조상의 사람들을 보통 옐로우, 오리엔탈, 아시아, 브라운, 몽고로이드 또는 힌두라고 불렀습니다.[17][18][19] 그리고 '아시아인'에 대한 미국의 정의는 원래 서아시아계 민족, 특히 터키계 미국인, 아르메니아계 미국인, 아시리아계 미국인, 이란계 미국인, 쿠르드계 미국인, 중동계 유대계 미국인, 그리고 일부 아랍계 미국인을 포함했지만, 현대에는, 이 그룹들은 현재 중동계 미국인으로 간주되며 인구조사에서 백인계 미국인 아래에 분류됩니다.[20][12][21] "아시아계 미국인"이라는 용어는 역사가 활동가인 이치오카 유지와 엠마 지에 의해 1968년 아시아계 미국인 정치 동맹이 설립되는 동안 만들어졌으며,[22][23] 그들은 또한 이 용어를 대중화한 것으로 인정받았으며, 이는 새로운 "민족 간 범 아시아계 미국인 스스로 정의하는 정치 집단"을 구성하는 데 사용되었습니다.[17][24] 이 노력은 부당한 베트남 전쟁으로 간주되는 것에 정면으로 반대하는 신좌파 반전 및 반제국주의 운동의 일부였습니다.[25]

1980년대에 "아시아인" 범주에 포함되기 전에 남아시아 혈통의 많은 미국인들은 보통 자신들을 백인 또는 기타인으로 분류했습니다.[26] 변화하는 이민의 패턴과 광범위한 아시아 이민자 배제 기간은 인구 통계학적 변화를 가져왔고, 이는 다시 아시아계 미국인을 정의하는 것에 대한 공식적이고 일반적인 이해에 영향을 미쳤습니다. 예를 들어, 1965년에 제한적인 "국가 기원" 할당량이 제거된 이후, 아시아계 미국인 인구는 아시아의 다양한 지역에서 혈통을 가진 사람들을 더 많이 포함하도록 크게 다양해졌습니다.[27]

오늘날 "아시아계 미국인"은 정부와 학술 연구와 같은 대부분의 공식적인 목적으로 통용되는 용어이지만, 일반적으로 흔히 아시아인으로 줄여서 사용합니다.[28] 아시아계 미국인에 대한 가장 일반적으로 사용되는 정의는 극동, 동남아시아 및 인도 아대륙 출신의 모든 사람들을 포함하는 미국 인구조사국 정의입니다.[13] 이것은 주로 인구조사 정의가 기회 균등 프로그램과 측정에 대한 많은 정부 분류를 결정하기 때문입니다.[29]

옥스포드 영어 사전에 따르면, 미국에서 "아시아 사람"은 동아시아 혈통의 사람으로 가장 자주 생각됩니다.[30][31] "아시아인"은 일반적으로 동아시아 계통의 사람들 또는 거대한 눈가리개를 가진 다른 아시아 계통의 사람들을 가리킬 때 사용됩니다.[32] 이것은 미국의 인구 조사 정의와[13][33] 다르며, 많은 대학의 아시아계 미국학과는 동아시아, 남아시아, 또는 동남아시아계의 모든 사람들을 "아시아인"으로 간주합니다.[34]

인구조사정의

미국의 인구조사에서, 극동, 동남아시아, 인도 아대륙에서 기원 또는 혈통을 가진 사람들은 아시아 인종의 일부로 분류되는 반면,[10] 서아시아(이스라엘인, 터키인, 페르시아인, 쿠르드인, 아시리아인, 아랍인 등)와 코카서스(조지아인, 아르메니아인, 아제르바이잔인, 체첸인, 서카시안 등)에서 기원 또는 혈통을 가진 사람들은 아시아 인종의 일부로 분류됩니다.)는 "백인" 또는 "중동"으로 분류되며,[11][35] 중앙아시아 출신(카자흐, 우즈벡, 투르크멘, 타지크, 키르기스, 아프가니스탄 등)은 미국 인구조사국이 제공하는 어떤 인종 정의에서도 언급되지 않습니다.[11][36] 이와 같이, "아시아인"과 "아프리카인"의 혈통은 오직 인구 조사의 목적으로만 인종 범주로 간주되며, 정의는 서아시아, 북아프리카, 중앙아시아 이외의 아시아 및 아프리카 대륙의 일부에서 온 혈통을 나타냅니다.

1980년과 그 이전에 인구조사 양식은 특정 아시아 조상을 백인, 흑인 또는 흑인과 함께 별도의 그룹으로 분류했습니다.[37] 아시아계 미국인들도 "기타"로 분류되었습니다.[38] 1977년 연방 관리 예산국은 정부 기관이 "아시아 또는 태평양 섬 주민"을 포함한 인종 집단에 대한 통계를 유지하도록 요구하는 지침을 발표했습니다.[39] 1990년 인구조사에서는 "아시아 또는 태평양 섬 주민(API)"이 명시적인 범주로 포함되었지만, 응답자들은 하나의 특정 혈통을 하위 범주로 선택해야 했습니다.[40] 2000년 인구조사를 시작으로, "아시아계 미국인"과 "원주민 하와이안 및 기타 태평양 섬 주민"이라는 두 개의 별개의 분류가 사용되었습니다.[41]

논쟁과 비판

아시아계 미국인의 정의는 다른 맥락에서 미국인이라는 단어의 사용에서 파생되는 변형이 있습니다. 이민 지위, 시민권(출생권 및 귀화권), 문화 적응 및 언어 능력은 다양한 목적으로 미국인을 정의하는 데 사용되는 변수이며 공식 및 일상적인 사용 방식이 다를 수 있습니다.[42] 예를 들어, 미국인을 미국 시민만 포함하도록 제한하는 것은 일반적으로 시민 소유주와 비시민 소유주 모두를 지칭하는 아시아계 미국 기업의 논의와 충돌합니다.[43] 2023년 퓨 리서치 센터가 아시아계 미국인을 대상으로 실시한 설문조사에 따르면, 28%가 "아시아인"이라고 자칭하고 있으며, 52%는 보다 특정한 민족 집단에 의해 자신을 지칭하는 것을 선호하고 10%는 단순히 "미국인"이라고 자칭하는 것을 발견했습니다.[44]

2004년 PBS 인터뷰에서 아시아계 미국인 작가들로 구성된 패널은 어떻게 일부 그룹이 아시아계 미국인 범주에 중동계 사람들을 포함시키는지에 대해 논의했습니다.[45] 아시아계 미국인 작가 스튜어트 이케다(Stewart Ikeda)는 "'아시아계 미국인'의 정의는 종종 누가 묻고, 누가 정의하고, 어떤 맥락에서, 왜... '아시아 태평양 미국인'의 가능한 정의는 많고, 복잡하고, 변화하고 있습니다. 아시아 아메리카 연구 회의의 일부 학자들은 러시아인, 이란인, 그리고 이스라엘인 모두가 이 분야의 연구 주제에 적합할 수 있다고 제안합니다."[46] 월스트리트 저널의 제프 양(Jeff Yang)은 아시아계 미국인에 대한 범민족적 정의는 독특한 미국인의 구성이며, 정체성으로서 "베타(beta)"라고 쓰고 있습니다.[47] 대부분의 아시아계 미국인들은 "아시아계 미국인"이라는 용어가 자신을 식별하는 용어라는 것에 대해 양면성을 느낍니다.[48] 사회학자이자 퀸즈 칼리지의 사회학 교수인 평갑민은 이 용어는 단지 정치적인 것이며, 아시아계 미국인 활동가들에 의해 사용되고 정부에 의해 더욱 강화되었다고 말했습니다. 그 외에도 남아시아인과 동아시아인이 '문화, 신체적 특징, 혹은 이주 이전의 역사적 경험'에서 공통점이 없다고 느끼고 있습니다.[49]

학자들은 아시아계 미국인이라는 용어의 정확성, 정확성, 유용성에 대해 고심해 왔습니다. 아시아계 미국인의 "아시아인"이라는 용어는 아시아의 다양한 사람들 중 일부만을 포괄하고, 인종이 아닌 "인종" 범주로 간주된다는 이유로 가장 자주 비난을 받습니다. 이는 인종적으로 다른 남아시아인과 동아시아인을 동일한 "인종"의 일부로 분류했기 때문입니다.[29] 또한 서아시아인(미국 인구조사에서 "아시아인"으로 간주되지 않는)은 인도인과 문화적 유사성을 일부 공유하지만 동아시아인과 거의 유사하지 않으며 후자의 두 그룹은 "아시아인"으로 분류됩니다.[50] 학자들은 또한 아시아계 미국인의 범주가 유사하게 다양한 출신을 가진 사람들로 구성되는 방식을 고려할 때 왜 아시아계 미국인이 "인종"으로 간주되는지를 결정하는 것이 어렵다는 것을 발견했습니다.[51] 하지만, 남아시아 불교의 기원 때문에 남아시아인들과 동아시아인들이 "정당하게" 함께 묶일 수 있다는 주장이 제기되었습니다.[52]

이와는 대조적으로 인종과 아시아계 미국인의 정체성에 대한 대표적인 사회과학 및 인문학자들은 인종에 대한 사회적 태도와 아시아계 혈통을 포함한 미국의 인종 구성 때문에 아시아계 미국인들은 "공유된 인종 경험"을 가지고 있다고 지적합니다.[53] 이러한 공유된 경험 때문에 아시아계 미국인이라는 용어는 아시아계 미국인들 사이에 이 범주에 속하는 사람들에게 특정한 고정관념을 포함한 일부 경험의 유사성 때문에 여전히 유용한 범민족적 범주로 주장되고 있습니다.[53] 그럼에도 불구하고, 다른 사람들은 많은 미국인들이 모든 아시아계 미국인들을 동등하게 대우하지 않는다고 말하면서, "아시아계 미국인"은 일반적으로 동아시아계 사람들과 동의어이며, 따라서 동남아시아와 남아시아계 사람들을 배제한다는 사실을 강조했습니다.[54] 일부 남아시아 및 동남아시아계 미국인들은 그들과 동아시아계 미국인들 사이의 인식된 인종 및 문화적 차이 때문에 그들 자신을 "브라운 아시아인" 또는 단순히 "브라운"이라고 표현하는 대신 아시아계 미국인 레이블과 동일시하지 않을 수 있습니다.[55][56][57]

인구통계학

아시아계 미국인의 인구 통계는 미국에 있는 이질적인 사람들을 묘사합니다. 그들의 조상을 동아시아, 남아시아 또는 동남아시아에 있는 하나 이상의 국가로 추적할 수 있습니다.[58] 이들은 미국 전체 인구의 7.3%를 차지하기 때문에 "아시아인" 또는 "아시아계 미국인"의 언론 및 뉴스 토론에서 이 그룹의 다양성이 종종 무시됩니다.[59] 민족적 하위 집단들 사이에 약간의 공통점이 있지만, 각 집단의 역사와 관련된 다른 아시아 민족들 사이에 상당한 차이가 있습니다.[60] 아시아계 미국인 인구는 크게 도시화되어 있는데, 그 중 거의 4분의 3이 인구 250만 명이 넘는 대도시 지역에 살고 있습니다.[61] 2015년[update] 7월 현재 캘리포니아에는 아시아계 미국인이 가장 많이 거주하고 있으며, 하와이는 유일하게 아시아계 미국인이 가장 많은 주였습니다.[62]

아시아계 미국인의 인구 통계는 알파벳 순서에 따라 다음과 같이 더 세분화될 수 있습니다.

- 중국계 미국인, 홍콩계 미국인, 일본계 미국인, 한국계 미국인, 마카오계 미국인, 몽골계 미국인, 류위안계 미국인, 대만계 미국인, 티베트계 미국인 등 동아시아계 미국인.

- 방글라데시계 미국인, 부탄계 미국인, 인도계 미국인, 인도-카리브계 미국인, 인도-피지안계 미국인, 몰디브계 미국인, 네팔계 미국인, 파키스탄계 미국인, 스리랑카계 미국인 등 남아시아계 미국인.

- 브루나이계 미국인, 버마계 미국인, 캄보디아계 미국인, 필리핀계 미국인, 흐몽계 미국인, 인도네시아계 미국인, 아이유 미엔계 미국인, 카렌계 미국인, 라오스계 미국인, 말레이시아계 미국인, 싱가포르계 미국인, 태국계 미국인, 티모르계 미국인, 베트남계 미국인 등 동남아시아계 미국인.

이러한 그룹화는 미국 이민 전에 출신 국가별로 이루어지며, 예를 들어 싱가포르계 미국인은 중국계, 인도계 또는 말레이계일 수 있기 때문에 반드시 민족별로 분류되는 것은 아닙니다.

아시아계 미국인은 상기 그룹과 다른 인종, 또는 상기 그룹의 복수의 기원 또는 혈통을 가진 다인종 또는 혼혈인을 포함합니다.

- 시간에 따른 아시아계 미국인(혼자) 인구 분포

-

1860

-

1870

-

1880

-

1890

-

1990

-

2000

-

2010

-

2020

언어

2010년, 가정에서 중국어 중 하나를 사용하는 사람은 280만명(5세 이상)이었는데,[63] 스페인어 다음으로 미국에서 세 번째로 흔한 언어입니다.[63] 다른 아시아 언어로는 힌두스타니어(힌디/우르두어), 타갈로그어, 베트남어, 한국어가 있으며, 4개 언어 모두 미국에서 100만 명 이상의 사용자를 보유하고 있습니다.[63]

2012년 알래스카, 캘리포니아, 하와이, 일리노이, 매사추세츠, 미시간, 네바다, 뉴저지, 뉴욕, 텍사스, 워싱턴은 투표권법에 따라 아시아 언어로 된 선거 자료를 출판하고 있었습니다.[64] 이러한 언어에는 타갈로그어, 만다린 중국어, 베트남어, 스페인어,[65] 힌디어, 벵골어가 포함됩니다.[64] 선거 자료는 구자라트어, 일본어, 크메르어, 한국어, 태국어로도 제공되었습니다.[66] 2013년 여론조사에 따르면 아시아계 미국인의 48%는 모국어로 된 미디어를 주요 뉴스 소스로 생각했습니다.[67]

2000년 인구 조사에 따르면 아시아계 미국인 공동체의 가장 두드러진 언어는 중국어(광동어, 타이샤네어, 호키엔어), 타갈로그어, 베트남어, 한국어, 일본어, 힌디어, 우르두어, 텔루구어, 구자라트어 등입니다.[68] 2008년에는 알래스카, 캘리포니아, 하와이, 일리노이, 뉴욕, 텍사스, 워싱턴 주에서 선거에 중국어, 일본어, 한국어, 타갈로그어, 베트남어가 모두 사용되고 있습니다.[69]

종교

퓨 리서치 센터가 2022년 7월 5일부터 2023년 1월 27일까지 실시한 조사에 따르면, 아시아계 미국인의 종교적 풍경은 다양하고 진화하고 있습니다.[70] 이 조사에 따르면 아시아계 미국인의 32%가 종교적으로 독립하지 않고 있으며, 이는 2012년의 26%보다 증가한 것입니다. 기독교는 2012년 이후 8% 감소했지만, 아시아계 미국인들 사이에서 가장 큰 종교 집단인 34%를 유지하고 있습니다.[71]

기독교

가장 최근의 Pew Research Center 조사에 따르면 아시아계 미국 성인의 약 34%가 기독교인이라고 응답하고 있으며, 이는 2012년의 42%보다 감소한 수치입니다. 이러한 감소는 특히 현재 아시아계 미국인 인구의 16%를 차지하고 있는 개신교에서 두드러지는데, 이는 2012년의 22%에서 감소한 것입니다.[72] 반면 가톨릭 신자들은 아시아계 미국 성인 인구의 17%를 차지할 정도로 비교적 안정적인 지위를 유지하고 있으며, 이는 2012년 19%에서 거의 변화가 없습니다. 공식적인 종교적 정체성을 넘어서 아시아계 미국인 중 18%가 기독교와 문화적 또는 가족적으로 가깝다고 보고합니다. 이는 아시아계 미국인의 약 51%가 기독교 신앙과 어떤 연관성을 나타낸다는 것을 의미합니다.[72]

필리핀과 한국계 미국인들은 특히 기독교와 강한 유대관계를 보이고 있습니다. 필리핀계 미국인 중 74%가 기독교인으로 인식하고 있으며, 문화적으로 기독교에 가깝다고 느끼는 사람들을 고려하면 이 수치는 90%로 증가합니다. 한국계 미국인 중 59%는 기독교인이라고 밝히고 81%는 신앙과 어떤 연관성을 표현합니다. 필리핀계 미국인은 대부분 가톨릭 신자(57%)인 반면 한국계 미국인은 개신교 신자로 34%가 복음주의 개신교 신자로 나타났습니다.[72]

무소속

아시아계 미국인들의 종교적 불화는 꾸준히 증가하고 있습니다. 아시아계 미국인의 32%는 종교적으로 무관한 사람으로 인식되며, 이는 무신론자, 불가지론자 또는 "특별히 아무 것도 없다"는 사람들을 포함합니다.[73] 이는 2012년 26%에서 성장한 것입니다. 이들 대부분의 사람들은 자신들의 종교를 무신론자나 불가지론자라고 명시적으로 주장하는 것이 아니라 "특별히 아무 것도 아니다"라고 말합니다. 공식적인 종교적 소속이 부족함에도 불구하고 상당수의 종교적으로 소속되지 않은 아시아계 미국인들은 문화적 또는 조상의 이유로 다양한 종교적 또는 철학적 전통과 관련을 맺고 있습니다. 전체적으로, 아시아계 미국인의 12%만이 어떤 종교적 또는 철학적 전통과도 관련이 없다고 보고합니다.[73]

아시아계 미국인들 중 중국계와 일본계 미국인들은 종교적으로 무소속일 가능성이 더 높으며, 각각 56%와 47%가 무소속일 가능성이 높다고 합니다. 두 집단 모두 공식적인 종교적 소속이 없음에도 불구하고 종교적 전통에 대한 문화적 또는 조상의 연관성을 느낄 가능성이 더 높습니다. 반대로, 인도, 필리핀, 베트남계 미국인들은 종교적으로 소속되지 않을 가능성이 상당히 낮고 종교적 전통에 대한 어떤 형태로든 연관성을 표현할 가능성이 더 높습니다.[73]

종교적 경향

아시아계 미국인 중 기독교인의 비율은 1990년대 이후 급격히 감소했는데, 이는 주로 기독교가 소수 종교인 국가(특히 중국과 인도)에서 대규모 이민으로 인한 것입니다. 1990년 아시아계 미국인의 63%가 기독교인이라고 밝힌 반면, 2001년에는 43%만이 기독교인이라고 답했습니다.[74] 이러한 발전은 전통적인 아시아 종교의 증가를 동반하고 있으며, 같은 10년 동안 사람들은 이 종교들과 동일시하고 있습니다.[75]

역사

조기 이민

아시아계 미국인들이나 그들의 조상들이 많은 다른 나라들로부터 미국으로 이주했기 때문에, 아시아계 미국인들은 각각의 독특한 이민 역사를 가지고 있습니다.[76]

필리핀 사람들은 16세기부터 미국이 될 영토에 있었습니다.[77] 1635년 버지니아주 제임스타운에 "동인도인"이 등록되었고,[78] 그 이전에 1790년대 동부 해안과 1800년대 서부 해안에 인도 이민자들이 더 많이 정착했습니다.[79] 1763년, 필리핀인들은 스페인 배를 타고 학대를 피해 루이지애나의 세인트 말로라는 작은 정착지를 세웠습니다.[80] 필리핀 여성이 없었기 때문에 이들 '마닐라멘'은 알려진 대로 케이준과 원주민 여성들과 결혼했습니다.[81] 1841년에 동해안에 도착한 나카하마 만지로가 일본인 최초로 미국에 건너왔고, 1858년에 조지프 헤코가 일본계 미국 시민권자가 되었습니다.[82]

중국 선원들은 제임스 쿡 선장이 하와이에 온 지 몇 년 [83]후인 1789년에 처음으로 하와이에 왔습니다. 많은 사람들이 정착하여 하와이 여성들과 결혼했습니다. 하와이나 샌프란시스코의 대부분의 중국인, 한국인, 일본인 이민자들은 19세기에 설탕 농장이나 건설 장소에서 일하기 위해 노동자로 도착했습니다.[84] 1898년 하와이가 미국에 합병되었을 때 수천 명의 아시아인들이 있었습니다.[85] 후에, 필리핀인들도 제한적이었지만, 취업 기회에 이끌려 노동자로 일하기 시작했습니다.[86] 류큐인들은 1900년에 하와이로 이주하기 시작했습니다.[87]

아시아에서 미국으로의 대규모 이주는 19세기 중반 중국 이민자들이 서해안에 도착하면서 시작되었습니다.[88] 캘리포니아 골드러시의 일부를 형성한 이 초기 중국 이민자들은 광산 사업에 집중적으로 참여했고 이후 대륙횡단 철도 건설에 참여했습니다. 1852년까지 샌프란시스코의 중국인 이민자의 수는 2만 명 이상으로 증가했습니다. 1868년 메이지 유신 이후 일본인들의 미국 이민 파동이 시작되었습니다.[89] 1898년, 미국이 스페인-미국 전쟁에서 패배한 후, 미국이 스페인으로부터 필리핀 제도의 식민지 지배를 넘겨받았을 때, 필리핀 제도에 있는 모든 필리핀인들은 미국 국적이 되었습니다.[90]

배제시대

이 시기의 미국법, 특히 1790년의 귀화법에 따라 "자유로운 백인"만이 미국 시민으로 귀화할 수 있었습니다. 아시아 이민자들은 시민권을 받을 자격이 없기 때문에 투표와 같은 다양한 권리에 접근할 수 없었습니다.[91] 비차지 발사라는 인도 태생으로 귀화한 최초의 미국 시민권을 얻은 사람이 되었습니다.[92] 발사라의 귀화는 정상이 아니라 예외였고, 오자와프는 한 쌍의 경우였습니다. 미국(1922)과 미국 대 바갓 싱 틴드(1923) 대법원은 시민권에 대한 인종적 자격을 인정하고 아시아인들은 "백인"이 아니라고 판결했습니다. 그러나 수정헌법 14조의 출생권리 시민권 조항으로 인해 아시아계 미국인 2세들은 미국 시민이 될 수 있었습니다. 이 보장은 인종이나 혈통에 관계없이 미국 연방대법원의 Wong Kim Ark(1898)에 의해 적용되는 것으로 확인되었습니다.[93]

1880년대부터 1920년대까지 미국은 아시아 이민자들을 배제하는 시대를 여는 법을 통과시켰습니다. 다른 지역 출신 이민자에 비해 정확한 아시아계 이민자의 수는 적었지만, 상당 부분이 서구에 집중되었고, 그 증가로 인해 일부 원주민들의 정서가 발생하여 '황색의 위험'으로 알려졌습니다. 의회는 1880년대에 거의 모든 중국인들의 미국 이민을 금지하는 제한적인 법안을 통과시켰습니다.[94] 1907년 외교적 합의로 일본인들의 이민은 급격히 축소되었습니다. 1917년 아시아 금지 구역법은 아시아의 거의 모든 지역에서 이민을 금지했습니다.[95] 1924년 이민법은 "시민권을 받을 자격이 없는 외국인"은 미국으로 이민을 갈 수 없도록 규정하여 아시아인의 이민 금지를 강화했습니다.[96]

제2차 세계 대전

루즈벨트 대통령은 1942년 2월 19일 행정명령 9066을 발표하여 일본계 미국인 등을 억류하는 결과를 낳았습니다. 주로 서해안에 있는 10만 명 이상의 일본계 사람들이 강제로 추방당했는데, 이 행동은 나중에 효과가 없고 인종차별적이라고 여겨졌습니다.[97]일본계 미국인들은 단지 아이들, 노인들, 그리고 젊은 세대들을 포함한 그들의 인종 때문에 군 수용소에 고립되었습니다. '이세이:1세대'와 '수용소의 아이들'은 세계대전 중 일본계 미국인들의 상황을 보여주는 훌륭한 다큐멘터리입니다.

전후 이민

제2차 세계 대전 시대의 입법과 사법 판결은[which?] 점차 아시아계 미국인들의 이민과 귀화 능력을 증가시켰습니다. 1965년 이민 및 국적법 개정에 따라 베트남 전쟁 등 동남아시아에서 발생한 분쟁으로 인한 난민 유입과 함께 이민이 급증하였습니다. 아시아계 미국인 이민자들은 이미 직업적 지위를 얻은 사람들 중 상당한 비율을 차지하고 있는데, 이는 이민 집단 중 최초입니다.[98]

미국으로 온 아시아계 이민자의 수는 "1960년 491,000명에서 2014년 약 1,280만 명으로 2,597퍼센트의 증가를 나타냈습니다."[99] 아시아계 미국인들은 2000년에서 2010년 사이에 가장 빠르게 성장한 인종 집단이었습니다.[76][100] 2012년까지, 라틴 아메리카에서 온 이민자들보다 아시아에서 온 이민자들이 더 많았습니다.[101] 2015년 퓨 리서치 센터는 2010년부터 2015년까지 라틴 아메리카에서 온 이민자보다 아시아에서 온 이민자가 더 많았으며 1965년 이후 아시아인이 미국으로 온 전체 이민자의 4분의 1을 차지했습니다.[102]

아시아인들은 외국 태생 미국인들의 증가하는 비율을 차지하고 있습니다: "1960년에 아시아인들은 미국 외국 태생 인구의 5%를 차지했고, 2014년에는 그들의 비율이 미국 이민자 4천2백4십만 명의 30%로 증가했습니다."[99] 2016년 기준, "아시아는 (중남미에 이어) 미국 이민자의 두 번째로 큰 출생 지역입니다."[99] 2013년 중국은 멕시코를 제치고 미국 이민자들의 단일 출신 국가 1위를 차지했습니다.[103] 아시아 이민자들은 "전체 외국 태생 인구보다 귀화 시민일 가능성이 더 높습니다." 2014년 아시아 이민자의 59%가 미국 시민권을 가지고 있었던 반면, 전체 이민자의 47%는 미국 시민권을 가지고 있었습니다.[99] 전후 아시아계의 미국 이민은 다양해졌는데, 2014년 아시아계 미국 이민자의 31%는 동아시아 출신(주로 중국과 한국)이었고, 27.7%는 남아시아 출신(주로 인도), 32.6%는 동남아시아 출신(주로 필리핀과 베트남), 8.3%는 서아시아 출신이었습니다.[99]

아시아계 미국인 운동

1960년대 이전에, 아시아 이민자들과 그들의 후손들은 그들의 특별한 민족성에 따라 사회적 또는 정치적 목적을 위해 조직되고 선동되었습니다. 중국, 일본, 필리핀, 한국 또는 아시아 인도. 아시아계 미국인 운동(일본계 미국인 이치오카 유지와 중국계 미국인 엠마 지가 만든 용어)은 그들이 특히 아시아에서 인종 차별과 미국 제국주의에 대한 공통적인 반대에 공통적인 문제를 공유하고 있다는 것을 인식하고 모든 그룹을 연합으로 모았습니다. 이 운동은 민권 운동과 베트남 전쟁에 반대하는 시위에서 일부 영감을 받아 1960년대에 발전했습니다. "흑인 세력과 반전 운동의 영향을 끌어내며, 아시아계 미국인 운동은 다양한 민족을 가진 아시아인들을 통합하고 미국과 해외의 다른 제3세계 사람들과 연대를 선언하는 연합 정치를 형성했습니다. 이 운동의 분절들은 공동체의 교육 통제를 위해 고군분투했고, 사회 서비스를 제공하고 아시아 게토의 저렴한 주택을 보호했으며, 착취당한 노동자들을 조직했으며, 미국 제국주의에 항의했으며, 새로운 다민족 문화 기관을 건설했습니다."[104] 윌리엄 웨이(William Wei)는 이 운동을 "과거 압제의 역사와 현재의 해방 투쟁에 뿌리를 두고 있다"고 설명했습니다.[105] 이와 같은 운동은 1960년대와 1970년대에 가장 활발했습니다.[104]

점점 더 많은 아시아계 미국인 학생들이 아시아 역사와 미국과의 상호작용에 대한 대학 차원의 연구와 교육을 요구하고 있습니다. 그들은 다문화주의를 지지하고 긍정적인 행동을 지지하지만, 대학들이 차별적인 아시아 학생들에 대한 정원 배정을 반대합니다.[106][107][108]

주목할 만한 기여

예체능

아시아계 미국인들은 19세기 전반 장과 엥 벙커(원작 '시메 트윈즈')가 귀화한 이후부터 연예계에 몸담아왔습니다.[109] 20세기 내내, 텔레비전, 영화, 연극에서의 연기 역할은 상대적으로 적었고, 이용 가능한 많은 역할들은 좁고 틀에 박힌 캐릭터들을 위한 것이었습니다. 브루스 리 (미국 캘리포니아 샌프란시스코 출생)는 미국을 떠나 홍콩으로 간 후에야 영화 스타덤에 올랐습니다.

보다 최근에는 젊은 아시아계 미국인 코미디언들과 영화 제작자들이 유튜브에서 그들의 동료 아시아계 미국인들 사이에서 강력하고 충성스러운 팬층을 확보할 수 있는 매체를 발견했습니다.[110] 1976년 T씨와 Tina씨를 시작으로 2015년 Fresh Off the Boat까지 미국 미디어에서 여러 아시아계 미국인 중심의 텔레비전 쇼가 있었습니다.[111]

태평양에서 하와이 중국계 미국인 비트박스 연주자인 제이슨 톰은 미국 하와이주의 최서단과 최남단의 주요 도시인 호놀룰루에서 아웃리치 공연, 연설 참여 및 워크샵을 통해 비트박스의 기술을 영구화하기 위해 Human Beatbox Academy를 공동 설립했습니다.[112][113][114][115][116][117]

비지니스

이 섹션에는 과목의 이력에 대한 정보가 누락되어 있습니다. (2009년 8월) |

아시아계 미국인들이 19세기에 노동시장에서 크게 배제되자, 그들은 자신들의 사업을 시작했습니다. 그들은 편의점과 식료품점, 의료 및 법률 실무, 세탁소, 식당, 미용 관련 벤처, 하이테크 회사, 그리고 많은 다른 종류의 기업들을 시작했고, 미국 사회에서 매우 성공적이고 영향력 있게 되었습니다. 그들은 미국 경제 전반에 걸쳐 그들의 참여를 극적으로 확대했습니다. 아시아계 미국인들은 미국에서 가장 성공한 아시아 기업가들의 Goldsea 100 Compilitation of America's Most Successive Asian Enterpreneurs에서 입증된 바와 같이 캘리포니아 실리콘 밸리의 하이테크 분야에서 불균형적으로 성공했습니다.[118]

오늘날 아시아계 미국인들은 그들의 인구 기반에 비해 전문 분야에서 잘 대표되고 더 높은 임금을 받는 경향이 있습니다.[119] 주목할 만한 아시아계 미국인 전문가들의 Goldsea 컴필레이션은 많은 사람들이 최고 마케팅 책임자로서 불균형적으로 많은 수를 포함하여 주요 미국 기업에서 높은 지위를 차지하게 되었다는 것을 보여줍니다.[120]

아시아계 미국인들은 미국 경제에 큰 기여를 했습니다. 2012년 미국에는 486,000개에 조금 못 미치는 아시아계 미국인 소유의 기업이 있었는데, 이들 기업은 360만 명 이상의 근로자를 고용하여 총 7,076억 달러의 수입과 매출을 올렸고, 연간 직원 수는 1,120억 달러에 달했습니다. 2015년 아시아계 미국 및 태평양 섬나라 가구의 소비력은 4,556억 달러(월마트의 연간 수입과 비슷한 수준)였으며, 1,840억 달러의 세금 기여를 했습니다.[121]

유명 연예인들을 위한 드레스를 디자인하는 것으로 유명한 패션 디자이너이자 거물인 베라 왕은 자신의 이름을 딴 의류 회사를 시작했고, 지금은 다양한 럭셔리 패션 제품을 제공하고 있습니다. 안왕은 1951년 6월에 왕 연구소를 설립했습니다. Amar Bose는 1964년에 Bose Corporation을 설립했습니다. 찰스 왕(Charles Wang)은 컴퓨터 협회(Computer Associates)를 설립했으며, 후에 CEO 겸 회장이 되었습니다. 데이비드 켐과 케니 켐이라는 두 형제는 1991년에 힙합 패션 대기업인 사우스폴을 설립했습니다. Jen-Hsun Huang은 1993년에 Nvidia 회사를 공동 설립했습니다. 제리 양은 야후를 공동 설립했습니다! 1994년에 주식회사가 되었고 나중에 CEO가 되었습니다. Andrea Jung은 Avon Products의 회장 겸 CEO를 맡고 있습니다. Vinod Khosla는 Sun Microsystems의 창립 CEO였으며 유명한 벤처 캐피탈 회사인 Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers의 일반 파트너입니다. 스티브 첸(Steve Chen)과 자베드 카림(Jawed Karim)은 유튜브의 공동 제작자였으며, 2006년 구글이 이 회사를 16억 5천만 달러에 인수한 것의 수혜자였습니다. 포브스에 따르면 줌 비디오 커뮤니케이션의 설립자인 에릭 위안과 잭슨빌 재규어의 소유자인 샤히드 칸은 둘 다 순자산 면에서 미국 상위 100위 안에 든다고 합니다.[122][123] 아시아계 미국인들은 다른 분야에 크게 기여했을 뿐만 아니라 실리콘 밸리와 삼각지대와 같은 저명한 혁신적인 연구개발 지역에서 미국의 과학기술 분야에서 상당한 기여를 해왔습니다.

정부와 정치

아시아계 미국인은 실제 투표 인구 측면에서 정치적 통합 수준이 높습니다. 1907년부터 아시아계 미국인들은 국가 차원에서 활동했으며 지역, 주 및 국가 차원에서 여러 명의 사무소 직원을 두고 있습니다. 더 많은 아시아계 미국인들이 공직에 선출되면서, 그들은 미국의 대외 관계, 이민, 국제 무역 및 기타 주제에 점점 더 많은 영향을 미치고 있습니다.[124] 미국 의회에 선출된 첫 아시아계 미국인은 1957년 달립 싱 손드(Dalip Singh Saund)였습니다.

미국 의회에서 근무한 가장 높은 순위에 오른 아시아계 미국인은 2012년에 사망한 상원의원이자 대통령인 다니엘 이노우에(Daniel Inouye) 목사였습니다. 미국 의회에는 여러 명의 아시아계 미국인들이 활동하고 있습니다. 아시아계 미국인 인구의 비율과 밀도가 높을수록 하와이는 가장 지속적으로 아시아계 미국인을 상원에 보내고 하와이와 캘리포니아는 가장 지속적으로 아시아계 미국인을 하원에 보냈습니다.[125]

미국 내각의 첫 아시아계 미국인 의원은 조지 W 부시 행정부에서 상무장관과 교통장관을 역임한 노먼 미네타였습니다. 2021년 현재 아시아계 미국인 순위에서 가장 높은 순위를 차지한 사람은 카말라 해리스 부통령입니다. 이전에 가장 높은 순위에 오른 아시아계 미국인은 미국 노동부 장관 (2001-2009)의 우선 순위에 오른 일레인 차오 교통부 장관 (2017-2021)이었습니다.

지금까지 미국 대통령 선거에 출마한 적이 있는 "약 12명의 아시아계 미국인 후보들"이 있었습니다.[126] 중국 이민자의 자녀인 하와이의 상원의원 Hiram Fong은 1964년과 1968년 공화당 전당대회에서 "최애 아들" 후보였습니다.[127][128] 1972년 Patsy T 의원님. 일본계 미국인 하와이의 밍크는 민주당 대통령 후보 지명에 실패했습니다.[129] 인도 이민자의 아들인 바비 진달 루이지애나 주지사는 2016년 공화당 대통령 후보 지명에 실패했습니다.[130] 대만 이민자의 아들인 기업가 겸 비영리 설립자 앤드류 양(Andrew Yang)은 2020년 민주당 대통령 후보 지명에 실패했습니다.[126] 2021년 1월 인도 이민자의 딸인 카말라 해리스(Kamala Harris)가 미국의 첫 아시아계 미국인 부통령이 되었습니다.[131]

웡 킴 아크(샌프란시스코 출생 중국계 이민자)와 미 법무부가 1년여 동안 벌인 다툼으로 출생시민권법이 미국 대법원에서 통과됐다는 미 농무부의 글이 대표적인 사례입니다.

투표행위

아시아계 미국인들은 한때 공화당의 강력한 선거구였습니다. 1992년 조지 H.W. 부시는 아시아 유권자의 55%를 얻었습니다.[132] 그러나 2020년까지 아시아계 미국인들은 민주당을 지지하는 쪽으로 방향을 틀었고, 조 바이든은 도널드 트럼프의 29%[133]를 70% 지지했습니다. 인종적 배경과 출신 국가는 최근 선거에서 아시아계 미국인의 투표 행태를 결정했는데, 인도계[134] 미국인과 중국계 미국인은 민주당의 강력한 선거구가 되었고, 베트남계 미국인은 공화당의 강력한 선거구가 되었습니다.[135]

2023년 설문조사에 참여한 필리핀인 중 68%는 민주당과 정치적으로 동일시하고 민주당에 투표했다고 답했습니다.[136]

저널리즘

Connie Chung은 1971년 CBS에서 보도한 주요 TV 뉴스 네트워크의 첫 번째 아시아계 미국인 전국 특파원 중 한 명이었습니다. 그녀는 이후 1993년부터 1995년까지 CBS 이브닝 뉴스의 공동 앵커를 맡았으며, 최초의 아시아계 미국인 국가 뉴스 앵커가 되었습니다.[137] ABC에서 Kashiwahara Ken은 1974년에 전국적으로 보도하기 시작했습니다. 1989년, 샌프란시스코 출신의 필리핀계 미국인 기자인 에밀 기예르모는 National Public Radio's All Things Considered에서 수석 진행자로 있을 때 국가 뉴스 쇼를 공동 진행한 최초의 아시아계 미국인 남성이 되었습니다. 1990년, 뉴욕 타임즈의 베이징 지국의 외국 특파원인 셰릴 우둔은 퓰리처상을 수상한 최초의 아시아계 미국인이 되었습니다. 앤 커리는 1990년에 NBC 뉴스의 기자로 입사했고, 이후 1997년에 투데이 쇼의 주요 기자가 되었습니다. 캐롤 린은 아마도 CNN에서 9시부터 11시까지의 뉴스를 최초로 보도한 것으로 가장 잘 알려져 있습니다. 산제이 굽타 박사는 현재 CNN의 수석 건강 특파원입니다. 더 뷰의 전 공동 진행자였던 리사 링은 이제 내셔널 지오그래픽 채널의 익스플로러를 진행할 뿐만 아니라 CNN과 오프라 윈프리 쇼에 대한 특별한 보도를 제공합니다. 귀화한 인도 태생의 이민자인 페리드 자카리아(Fareed Zakaria)는 국제 문제를 전문으로 다루는 저명한 언론인이자 작가입니다. 그는 타임지의 편집장이고, CNN의 Fareed Zakaria GPS의 진행자입니다. Juju Chang, James Hatori, John Yang, Veronica De La Cruz, Michelle Malkin, Betty Nguyen, 그리고 Julie Chen은 텔레비전 뉴스에서 익숙한 얼굴이 되었습니다. 존 양은 피바디 상을 받았습니다. 시애틀 타임즈의 스탭 작가인 알렉스 티종은 1997년에 퓰리처상을 수상했습니다.

군사의

1812년 전쟁 이후, 아시아계 미국인들은 미국을 대표하여 봉사하고 싸웠습니다. 1948년 미군의 탈분단이 발생하기 전까지 분리된 부대와 비분리 부대에서 모두 복무한 31명은 미국에서 가장 높은 전투 공로 훈장인 명예 훈장을 받았습니다. 이 중 21개는 제2차 세계 대전 제442연대 전투단의 대부분이 일본계 미국인 제100보병대대원들에게 수여된 것으로, 미국군 역사상 가장 높은 규모의 부대입니다.[138] 가장 높은 순위에 오른 아시아계 미국인 군 관계자는 4성 장군이자 육군 참모총장인 에릭 신세키였습니다.[139]

과학기술

아시아계 미국인들은 과학기술에 많은 주목할 만한 공헌을 했습니다. 기술 분야에서는 아시아계 미국인이 가장 영향력이 큽니다. 웹사이트 ideas.ted.com 의 기사에 따르면 하이테크 기업의 40% 이상이 고도로 숙련된 아시아계 미국인들에 의해 설립되었습니다. 그것은 또한 AAPI(Asian American Pacific Islanders)가 주목할 만한 기술 혁신과 과학적 발견에 기여하고 있다고 말합니다. 예를 들어, 야후, 줌, 유튜브, 링크드인의 공동 설립자들은 아시아계 미국인 기부자들입니다. 세기 21세기에 아시아계 미국인들은 중국, 한국, 방글라데시, 인도와 같은 다른 아시아 국가들과 인맥을 형성하고 있습니다. 또 다른 예는 원래 인도 출신인 수십억 개 회사의 CEO일 수 있습니다. 사티아 나델라는 기술 분야에서 아시아계 미국인의 기여를 보여주는 예입니다. 아시아계 미국인들은 기술, 교육뿐만 아니라 정치적 측면에서도 중요한 기여를 하고 있습니다. 웡 킴 아크(샌프란시스코 출생 중국계 이민자)와 미 법무부가 1년여 동안 벌인 다툼으로 출생시민권법이 미국 대법원에서 통과됐다는 미 농무부의 글이 대표적인 사례입니다. 인도 이민자의 딸 카말라 해리스(Kamala Harris)는 2021년 미국의 첫 아시아계 미국인 부통령이 되었습니다.

스포츠

아시아계 미국인들은 20세기 대부분을 통하여 미국의 스포츠에 기여해왔습니다. 가장 주목할 만한 공헌들 중에는 올림픽 스포츠 뿐만 아니라 특히 제2차 세계 대전 이후의 프로 스포츠 분야도 포함되어 있습니다. 20세기 후반 아시아계 미국인의 인구가 증가하면서 아시아계 미국인의 기부는 더 많은 스포츠로 확대되었습니다. 아시아계 미국인 여자 선수의 예로는 미셸 콴, 클로이 김, 미키 고먼, 미라이 나가스, 마이아 시부타니 등이 있습니다.[140] 아시아계 미국인 남자 선수들의 예로는 제레미 린, 타이거 우즈, 하인스 워드, 리차드 파크, 그리고 네이선 애드리안이 있습니다.

문화적 영향

아시아계 미국인과 태평양 섬 주민들의 독특한 문화, 전통, 역사를 인정받아 미국 정부는 5월을 아시아 태평양 아메리카 유산의 달로 영구 지정했습니다.[141] 유럽 부모와 청소년의 관계보다 더 권위주의적이고 덜 따뜻한 것으로 묘사되는 중국 부모와 청소년의 관계를 통해 볼 수 있는 아시아계 미국인의 양육이 연구와 논의의 주제가 되었습니다.[142] 이러한 영향은 부모가 자녀를 규제하고 감시하는 방식에 영향을 미치며, 타이거 육아(Tiger parenting)로 설명되어 중국인이 아닌 부모들로부터 관심과 호기심을 받아왔습니다.[143]

보건의료

| 나라 기원. | 미국 전체에서 차지하는 비율. | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| IMGs[144] | IDGs[145] | INGs[146] | |

| 인디아 | 19.9% (47,581) | 25.8% | 1.3% |

| 필리핀 | 8.8% (20,861) | 11.0% | 50.2% |

| 파키스탄 | 4.8% (11,330) | 2.9% | |

| 대한민국. | 2.1% (4,982) | 3.2% | 1.0% |

| 중국 | 2.0% (4,834) | 3.2% | |

| 홍콩 | 1.2% | ||

| 이스라엘 | 1.0% | ||

아시아계 이민자들도 미국 내 아시아계 의료인들의 증가를 통해 미국 의료 지형을 바꾸고 있습니다. 1960년대와 1970년대에 시작된 미국 정부는 시골과 의료 서비스가 부족한 도시 지역의 의사 부족 문제를 해결하기 위해 특히 인도와 필리핀에서 많은 외국 의사들을 초청했습니다. 그러나 미국 학교들이 증가하는 인구에 걸맞게 충분한 의료 공급자를 생산하지 못하면서 외국 의료인을 수입하는 추세는 장기적인 해결책이 되었습니다. 높은 교육 비용과 높은 직업 불만족, 사기 저하, 스트레스 및 소송으로 인해 미국 대학생들 사이에서 의학에 대한 관심이 감소하는 가운데 아시아계 미국인 이민자들은 수백만 명의 미국인들에게 의료 종사자의 공급을 유지했습니다. 의료 종사자를 위한 J1 비자 프로그램을 사용하는 고도로 숙련된 객원 노동자를 포함한 아시아계 미국인 국제 의학 졸업자들은 보건 전문 인력 부족 지역(HPSA)과 미국 의학 졸업자들이 채우지 못하는 전문 분야, 특히 1차 의료 및 농촌 의학 분야에서 일하는 경향이 있다고 기록되어 있습니다.[147][148] 2020년 미국의 전체 의료 인력 중 의사의 17%가 아시아계 미국인이었고, 의사 보조원의 9%가 아시아계 미국인이었으며, 간호사의 9% 이상이 아시아계 미국인이었습니다.[149]

아시아계 미국인 4명 중 1명 가까이가 일반적인 대체 의학을 사용할 가능성이 높습니다.[150] 여기에는 전통 한의학과 아유르베다가 포함됩니다.[150][151] 사용이 보편화됨에 따라 이러한 일반적인 대체 의약품의 시술자를 통해 아시아계 미국인들과 협력함으로써 사용이 부족한 의료 절차의 사용이 증가할 수 있습니다.[152]

교육

| 민족성 | 고등학교 졸업률, 2004 | 학사학위 2010년 이상 |

|---|---|---|

| 방글라데시어 | 미신고의 | 49.6% |

| 캄보디아의 | 미신고의 | 14.5% |

| 중국인 | 80.8% | 51.8% |

| 필리핀인 | 90.8% | 48.1% |

| 인디언의 | 90.2% | 70.7% |

| 인도네시아인 | 미신고의 | 48.7% |

| 일본인입니다 | 93.4% | 47.3% |

| 코리안 | 90.2% | 52.9% |

| 라오스인 | 미신고의 | 12.1% |

| 파키스탄인 | 87.4% | 55.1% |

| 대만의 | 미신고의 | 73.7% |

| 베트남의 | 70.0% | 26.3% |

| 미국 총인구 | 83.9% | 27.9% |

| 출처: 2004[153][154][155], 2010[156] | ||

미국의 주요 인종 분류 중 아시아계 미국인은 교육 자격이 가장 높습니다. 그러나 이는 개별 민족에 따라 다릅니다. 예를 들어, 2010년 모든 아시아계 미국인 성인을 대상으로 한 연구에서는 42%가 적어도 대학 학위를 가지고 있지만, 베트남계 미국인은 16%, 라오스계와 캄보디아계는 5%에 불과하다는 것을 발견했습니다.[157] 그러나 2008년 미국 인구조사 통계에 따르면 베트남계 미국인의 학사학위 취득률은 26%로 전체 미국인의 27%와 크게 다르지 않은 것으로 나타났습니다.[158] 2010년 인구조사 자료에 따르면 아시아 성인의 50%가 학사학위 이상을 취득한 반면, 전체 미국인의 28%,[159] 비히스패닉계 백인의 34%가 학사학위 이상을 취득한 것으로 나타났습니다.[160] 대만계 미국인은 2010년에 거의 74%가 적어도 학사학위를 취득하여 가장 높은 교육률을 가지고 있습니다.[156] 2012년[update] 12월 현재 아시아계 미국인은 아이비리그 학교의 학생 인구 중 12~18%를 차지하고 있으며,[161][a] 이는 그들이 차지하는 비율보다 큽니다. 예를 들어, 2023년 하버드 대학 수업은 학생들이 25%의 아시아계 미국인이라고 인정했습니다.[166]

2012년 직전 몇 년 동안 아시아계 미국인 성인 이민자의 61%가 학사 이상의 대학 교육을 받았습니다.[76]

2020년 8월, 미국 법무부는 예일대가 아시아 후보자들의 인종을 근거로 차별했다고 주장했고, 예일대는 이를 부인했습니다.[167][168]

대중매체

아시아계 미국 문화는 문학, TV 쇼 및 영화와 같은 여러 주류 형태로 언급됩니다. 존 M 감독의 크레이지 리치 아시안스. Chu는 중국계 미국인 경제학 교수 Rachel Chu를 따릅니다. 이민진의 소설 파친코는 일본으로 이주한 한국인들의 이야기를 담은 세대간 이야기입니다.인기 있는 아시아계 미국 연극 중에는 '치킨쿠프 차이나맨', '그리고 영혼은 춤을 출 것이다', '페이퍼 엔젤스', '황열병' 등이 있습니다.

신원

2023년을 기준으로 최근 설문조사에 따르면 응답자 5명 중 1명이 비아시아인에게 아시아인이라고 밝히지 않는다고 답했습니다. 대부분의 이민자들은 미국 태생의 아시아계 미국인들과 비교하여 아시아인으로 확인됩니다. 18세 미만의 사람들은 아시아인이라고 밝히지 않을 가능성이 더 높습니다. 65세 이상의 사람들은 아시아인으로 식별될 가능성이 더 높습니다.[169]

사회적 정치적 문제

미디어 묘사

아시아계 미국인은 미국 전체 인구의 약 7.2%[171]를 차지하기 때문에 미디어 대우에서 그룹 내 다양성이 간과되는 경우가 많습니다.[172][173]

대나무 천장

이 개념은 아시아계 미국인을 성공적이고, 고학력, 지적이고, 부유한 사람들로 구성된 엘리트 집단으로 묘사함으로써 아시아계 미국인을 고양시키는 것으로 보이지만, 또한 목소리 리더십, 부정적인 감정, 위험 감수와 같은 다른 인간적 특성을 배제하고 지나치게 편협하고 지나치게 일차원적으로 묘사하는 것으로도 간주될 수 있습니다. 실수로부터 배울 수 있는 능력과 창의적인 표현에 대한 열망.[174] 또한 모델 소수 신화에 기반한 사람들의 기대가 현실과 맞지 않을 때 모델 소수자 틀에 맞지 않는 아시아계 미국인들은 어려움에 직면할 수 있습니다. 모델 소수자 틀 밖의 특성은 아시아계 미국인에게 부정적인 성격 결함으로 볼 수 있지만, 그러한 특성은 일반 미국인 대다수에게 긍정적입니다(예: 위험 감수, 자신감, 권한 부여). 이런 이유로 아시아계 미국인들은 직장 내 유리천장에 해당하는 아시아계 미국인에 해당하는 "대나무 천장"을 마주하게 되는데, 포춘지 선정 500대 CEO 중 동양인 비율은 1.5%에 불과하며, 이 비율은 미국 전체 인구의 비율보다 작습니다.[175]

대나무 천장은 조직 내부에서 아시아계 미국인의 경력 개발을 방해하는 개인적, 문화적, 조직적 요인의 조합으로 정의됩니다. 그 이후로 다양한 분야(비영리, 대학, 정부 포함)에서 아시아인들과 관련된 천장의 영향과 그들이 직면한 어려움에 대해 논의했습니다. 앤 피셔가 설명한 대로 '대나무 천장'은 직무수행이나 자질로 실질적으로 설명할 수 없는 '리더십 잠재력 부족', '의사소통 능력 부족' 등 주관적 요인을 바탕으로 아시아계와 미국계를 임원직에서 배제하는 역할을 하는 과정과 장벽을 의미합니다.[176] 이 주제에 관한 기사는 Crains, Fortune 잡지, The Atlantic에 실렸습니다.[177]

불법이민

2012년에는 130만 명의 아시아계 미국인이 있었고, 비자를 기다리는 사람들의 경우 45만 명 이상의 필리핀인, 32만 5천 명 이상의 인도인, 25만 명 이상의 베트남인, 그리고 225,000명 이상의 중국인들이 비자를 기다리는 긴 밀린 일이 있었습니다.[178] 2009년 기준으로 필리핀인과 인도인은 각각 27만 명과 20만 명으로 추정되는 '아시아계 미국인'의 외국인 이민자 수가 가장 많았습니다. 인도계 미국인은 2000년 이후 불법 이민이 125% 증가하면서 미국에서 가장 빠르게 성장하고 있는 외국인 이민자 집단이기도 합니다.[179] 이어 한국인(20만 명), 중국인(12만 명) 순입니다.[180] 그럼에도 불구하고 아시아계 미국인은 미국에서 귀화율이 가장 높습니다. 2015년에는 총 730,259명의 지원자 중 261,374명이 새로운 미국인이 되었습니다.[181] 미국 국토안보부에 따르면, 2015년에 미국 귀화를 신청한 상위 국가들 중 인도, 필리핀, 그리고 중국 출신의 합법적인 영주권자들 또는 영주권자들이 있었습니다.[182]

아시아계 미국인들이 집단으로 성공하고 미국에서 범죄율이 가장 낮다는 고정관념 때문에, 불법 이민에 대한 대중의 관심은 대부분 아시아인들을 배제한 채 멕시코와 라틴 아메리카 출신들에게 집중되고 있습니다.[183] 아시아인들은 히스패닉계와 라틴계 다음으로 미국에서 두 번째로 큰 인종/민족 이민자 집단입니다.[184] 대부분의 아시아 이민자들이 합법적으로 미국으로 이민을 가지만,[185] 최대 15%의 아시아 이민자들이 합법적인 서류 없이 이민을 갑니다.[186]

인종에 기반을 둔 폭력

아시아계 미국인들은 그들의 인종과 민족에 따라 폭력의 대상이 되어 왔습니다. 이 폭력은 락스프링스 대학살,[187] 왓슨빌 폭동,[188] 1916년 남아시아인에 대한 벨링엄 폭동,[189] 진주만 공격 이후 일본계 미국인에 대한 공격,[190] 1992년 로스앤젤레스 폭동 당시 표적이 된 한국계 미국인 사업체 등을 포함하지만 이에 국한되지는 않습니다.[191] 미국 변경지역에서 중국인들에 대한 공격은 흔했습니다. 여기에는 1866년 뱀 전쟁, 1871년 로스앤젤레스 중국인 학살, 1887년 카우보이들이 중국인 학살 코브에서 중국인 광부들을 공격해 31명의 사망자를 낸 것이 포함되었습니다.[192] 1980년대 후반, 닷버스터즈로 알려진 라틴계 사람들에 의해 뉴저지에서 남아시아인들에 대한 폭행과 다른 증오 범죄가 일어났습니다.[193] 1990년대 후반, 백인 우월주의자에 의한 로스앤젤레스 유대인 커뮤니티 센터 총격 사건 중에 발생한 유일한 사망자는 필리핀인 우편 노동자였습니다.[194] 1989년 7월 17일 캘리포니아 스톡턴에 거주하던 떠돌이이자 전 주민인 패트릭 에드워드 퍼디가 운동장에 있던 클리블랜드 초등학교 학생들에게 총격을 가했습니다. 몇 분 만에 수십 발을 발사했지만 보도는 다양했습니다. 그는 권총 두 자루와 총검으로 무장한 AK-47로 학생 5명을 살해하고 최소 37명을 사살했습니다. 총기 난사 사건 이후 퍼디는 스스로 목숨을 끊었습니다.[195]

폭력으로 발현되지 않은 상황에서도 아시아계 미국인에 대한 경멸은 "중국, 일본, 더러운 무릎"이라는 운동장 구호와 같은 대중 문화의 측면에서 반영되었습니다.[196]

9.11 테러 이후, 시크교도 미국인들이 표적이 되어, 살인을 포함한 수많은 증오 범죄의 희생자가 되었습니다.[197] 다른 아시아계 미국인들도 브루클린,[198] 필라델피아,[199] 샌프란시스코,[200] 인디애나주 블루밍턴에서 인종에 기반을 둔 폭력의 희생자가 되었습니다.[201] 게다가, 젊은 아시아계 미국인들이 또래들보다 폭력의 대상이 될 가능성이 더 높은 것으로 보고되었습니다.[198][202] 2017년에는 스톡턴 리틀 마닐라의 한 커뮤니티 센터에 인종차별적인 낙서와 다른 재산 피해가 발생했습니다.[203] 아시아계 미국인들에 대한 인종차별과 차별은 여전히 지속되고 있으며, 최근의 이민자들뿐만 아니라 교육을 잘 받고 고도로 훈련된 전문가들에게도 일어나고 있습니다.[204]

최근 아시아계 미국인들이 주로 아프리카계 미국인 지역으로 이주하는 물결은 심각한 인종적 긴장을 초래했습니다.[205] 아시아계 미국인 학생들에 대한 흑인 반 친구들의 대규모 폭력 행위가 여러 도시에서 보고되었습니다.[206] 2008년 10월에는 사우스 필라델피아 고등학교에서 흑인 학생 30명이 아시아 학생 5명을 뒤쫓아 공격했고,[207] 1년 뒤에도 같은 학교에서 아시아 학생들에 대한 비슷한 공격이 일어나 이에 대한 아시아 학생들의 항의가 이어졌습니다.[208]

아시아계 기업들은 흑인들과 아시아계 미국인들 사이에서 자주 긴장의 표적이 되어 왔습니다. 1992년 로스앤젤레스 폭동 동안, 아프리카계 미국인들에 의해 2,000개 이상의 한국인 소유의 사업체들이 약탈되거나 불에 탔습니다.[209] 1990년부터 1991년까지 브루클린에 있는 아시아계 소유의 가게에 대한 세간의 이목을 끌고 인종적으로 동기부여된 불매운동이 지역 흑인 민족주의 운동가에 의해 조직되었고, 결국 주인은 그의 사업을 팔도록 강요당했습니다.[210] 2012년 달라스에서 아시아계 미국인 점원이 자신의 가게를 털었던 아프리카계 미국인에게 총을 쏜 후, 인종적으로 동기 부여된 아시아계 소유의 사업체에 대한 또 다른 불매운동이 일어났습니다.[211] 2014년 퍼거슨 소요 사태 때는 아시아계 소유의 상점들이 약탈당했고,[212] 2015년 볼티모어 시위 때는 아시아계 소유의 상점들이 약탈당했고, 아프리카계 미국인 소유의 상점들은 우회했습니다.[213] 아시아계 미국인에 대한 폭력은 인종에 따라 계속 발생하고 있으며,[214] 한 소식통은 아시아계 미국인이 증오 범죄와 폭력의 가장 빠르게 증가하는 대상이라고 주장합니다.[215]

미국의 코로나19 대유행 기간 동안 미국 내 반아시아 정서가 증가하면서 우려가 커졌습니다.[216][217] 2020년 3월, 도널드 트럼프 대통령은 이 질병을 기원에 따라 "차이나 바이러스"와 "쿵-플루"라고 불렀고, 아시아계 미국인 어드밴싱 저스티스와 웨스턴 스테이트 센터와 같은 대응 기관에서 그렇게 하는 것은 반 아시아 정서와 폭력을 증가시킬 것이라고 말했습니다.[218] 복스는 트럼프 행정부가 '차이나 바이러스', '쿵플루', '우한 바이러스'라는 용어를 사용하면 외국인 혐오증이 증가할 것이라고 썼습니다.[219] 질병명 지정 논란은 중국 외교부가 질병이 미국에서 발생했다고 주장하던 시기에 발생했습니다.[220] 아시아계 미국인들에 대한 이 질병과 관련된 폭력적인 행위들은 주로 뉴욕, 캘리포니아 등지에서 기록되고 있습니다.[217][221] 2020년 12월 31일 기준으로 뉴욕에서 반아시아 사건이 보고된 건수는 259건입니다.[222] 2021년 3월 기준으로 3800건 이상의 반아시아 인종차별 사건이 발생했습니다.[223] 주목할 만한 사건은 2021년 애틀랜타 스파 총격 사건으로, 8명의 사상자 중 6명이 아시아계였다는 치명적인 공격이었습니다. 총격범은 "모든 아시아인을 죽이겠다"고 말했다고 합니다.[224]

인종적 고정관념

20세기 후반까지 "아시아계 미국인"이라는 용어는 주로 활동가들에 의해 채택된 반면, 아시아계 혈통을 가진 평균적인 사람들은 그들의 특정 민족과 동일시되었습니다.[225] 1982년 빈센트 친의 살인은 중추적인 민권 사건이었고, 그것은 미국에서 아시아계 미국인들이 별개의 집단으로 부상했음을 나타냅니다.[225][226]

아시아인에 대한 고정관념은 대부분 사회에 의해 집단적으로 내면화되었고 이러한 고정관념의 영향은 일상적인 상호작용, 현재의 사건, 그리고 정부 입법에서 아시아계 미국인과 아시아 이민자들에게 부정적입니다. 많은 경우, 동아시아인에 대한 미디어 묘사는 종종 진정한 문화, 관습, 행동에 대한 현실적이고 진정한 묘사보다는 지배적인 미국 중심적 인식을 반영합니다.[227] 아시아인들은 차별을 경험했고, 그들의 민족적 고정관념과 관련된 증오범죄의 피해자가 되어 왔습니다.[228]

한 연구에 따르면 대부분의 비아시아계 미국인들은 일반적으로 인종이 다른 아시아계 미국인들을 구별하지 않는다고 합니다.[229] 중국계 미국인과 아시아계 미국인의 고정관념은 거의 같습니다.[230] 2002년에 실시된 아시아계 미국인과 중국계 미국인에 대한 미국인의 태도에 대한 설문조사에 따르면 응답자의 24%가 아시아계 미국인과의 상호 결혼에 찬성하지 않는 것으로 나타났으며, 이는 아프리카계 미국인의 15%에 비해 23%가 아시아계 미국인 대통령 후보를 지지하는 것을 불편하게 생각하는 것으로 나타났습니다. 여성은 14%, 유대인은 11%, 아시아계 미국인이 많이 거주하면 17%, 중국계 미국인에 대해 25%는 다소 또는 매우 부정적인 태도를 보였습니다.[231] 이 연구는 중국계 미국인들에 대한 몇 가지 긍정적인 인식을 발견했습니다: 강한 가족 가치 (91%), 사업가로서의 정직 (77%), 높은 교육 가치 (67%).[230]

아시아계 미국인은 '미국인'이 아니라 '영구적인 외국인'이라는 인식이 팽배해 있습니다.[231][232][233] 아시아계 미국인들은 그들이나 그들의 조상들이 얼마나 오랫동안 미국에 살았고 미국 사회의 일부였는가에 관계없이 다른 미국인들로부터 "당신은 정말 어디 출신입니까?"라는 질문을 받았다고 종종 보도합니다.[234] 많은 아시아계 미국인들은 그들 자신이 이민자가 아니라 오히려 미국에서 태어났습니다. 많은 동아시아계 미국인들은 그들이 중국인인지 일본인인지를 묻는데, 이것은 과거 이민자들의 주요 집단에 근거한 가정입니다.[232][235]

워싱턴주립대(WSU)가 실시하고 스티그마 앤 헬스(Stigma and Health)에 발표한 연구에 따르면 미국에서 코로나19 팬데믹으로 아시아인과 아시아계 미국인에 대한 차별이 증가했습니다.[236] NYPD는 2020년 반아시아 정서에 자극받은 증오범죄가 1,900% 증가했는데, 이는 주로 중국 우한에서 발생한 바이러스 때문이라고 보도했습니다.[237][238]

2022년에 실시된 여론조사에 따르면, 미국인의 33%는 아시아계 미국인이 미국보다 "출신국에 더 충실하다"고 믿는 반면, 21%는 아시아계 미국인이 적어도 코로나19 팬데믹에 대해 "부분적으로 책임이 있다"고 거짓으로 믿고 있습니다.[239] 또한, 아시아계 미국인의 29%만이 자신이 소속되어 있다고 느끼고 미국에서 받아들여지고 있다는 진술에 "완전히 동의한다"고 생각하는 반면, 71%는 미국에서 차별받고 있다고 대답했습니다.[239]

모형소수

아시아계 미국인들은 때때로 미국에서[240] 모범적인 소수자로 특징지어지는데, 그들의 많은 문화들이 강한 직업 윤리, 노인에 대한 존경, 높은 수준의 직업적, 학문적 성공, 가족, 교육 및 종교에 대한 높은 가치 평가를 장려하기 때문입니다.[241] 높은 가구 소득과 낮은 수감률,[242] 낮은 질병 비율, 평균 수명보다 높은 등의 통계도 아시아계 미국인들의 긍정적인 측면으로 거론되고 있습니다.[243]

암묵적인 충고는 다른 소수자들이 시위를 멈추고 아시아계 미국인의 직업 윤리와 고등교육에 대한 헌신을 본받아야 한다는 것입니다. 일부 비평가들은 이 묘사가 생물학적 인종차별을 문화적 인종차별로 대체하고 있으며, 중단되어야 한다고 말합니다.[244] 워싱턴 포스트에 따르면 "아시아계 미국인들이 소수 집단들 사이에서 구별되고 다른 유색인종들이 직면한 도전에 면역이 된다는 생각은 최근 #Model Minority Mantination과 같은 운동으로 사회 정의 대화에서 그 자리를 되찾기 위해 싸우고 있는 공동체에게 특히 민감한 문제입니다."[245]

모델 소수자 개념은 아시아인의 공교육에도 영향을 미칠 수 있습니다.[246] 다른 소수민족들과 비교해 볼 때, 아시아인들은 다른 미국인들에 비해 더 높은 시험 점수와 성적을 얻는 경우가 많습니다.[247] 아시아계 미국인을 과잉 성취자로 고정 관념하는 것은 학교 관계자들이나 또래 학생들이 모두 평균보다 더 높은 성적을 낼 것으로 기대한다면 해악으로 이어질 수 있습니다.[248] 아시아계 미국인의 매우 높은 교육 수준은 종종 주목되어 왔습니다. 예를 들어, 1980년에는 중국계 미국인의 74%, 일본계 미국인의 62%, 그리고 20-21세 한국계 미국인의 55%가 대학에 다녔고 백인의 3분의 1에 불과했습니다. 대학원 수준의 차이는 더욱 크며 특히 수학을 많이 활용하는 분야에서 차이가 두드러집니다. 2000년까지, UC 버클리와 UCLA와 같은 명문 공립 캘리포니아 학교의 다수의 학부생들이 아시아계 미국인이었습니다. 그 패턴은 제2차 세계 대전 이전 시대에 뿌리를 두고 있습니다. 중국과 일본계 미국인 원주민들은 20세기 초반 수십 년 동안 대다수 백인들과 교육적으로 동등한 수준에 이르렀습니다.[249] "모델 소수" 고정관념을 논의하는 한 작가 그룹은 "모델 소수"의 뒤에 "신화"라는 용어를 붙이기 시작했고, 따라서 개념과 고정관념이 아시아계 미국인 공동체와 민족에 어떻게 해를 끼치는지에 대한 담론을 장려했습니다.[250]

모델 소수자 개념은 일부 아시아계 미국인들에게 감정적으로 해로울 수 있는데, 특히 그들이 고정관념에 맞는 또래들에 부응할 것으로 예상되기 때문입니다.[251] 연구에 따르면 일부 아시아계 미국인은 다른 그룹에 비해 스트레스, 우울증, 정신 질환 및 자살률이 [252]높아 소수민족 이미지를 달성하고 이에 부응해야 하는 압력이 일부 아시아계 미국인에게 정신적, 심리적 피해를 줄 수 있습니다.[253] 미국 심리학회는 아시아계 미국인들의 자살률에 대한 신화를 문제 삼는 2007년 자료에 의존하는 논문을 발표했습니다.[254]

모델 소수자 개념이 아시아계 미국인들에게 미치는 정신적, 심리적 통행료와 함께,[253] 그들은 또한 신체적 건강에 미치는 영향과 개인이 더 구체적으로 암 검진이나 치료를 받으려는 욕구에 직면해 있습니다. 아시아계 미국인들은, 미국의 다른 인종/민족 집단들 사이에서, 암 검진율이 현저히 낮으면서도 주요 사망 원인이 암인 유일한 집단입니다.[255] 진단을 받을 경우 소외감이나 건강한[256] 삶의 이미지에 대한 고정관념에 순응하려는 욕구와 같은 다양한 압력은 증상이 시작되기 전에 암 검진이나 치료를 추구하는 것을 억제할 수 있습니다.[257]

"모범적 소수자"라는 고정관념은 다른 역사를 가진 다른 민족을 구별하지 못합니다.[258] 민족별로 나누어 보면, 아시아계 미국인들이 누리는 경제적, 학문적 성공이 소수 민족에 집중되어 있음을 알 수 있습니다.[259] 캄보디아인, 흐몽인, 라오스인(그리고 덜하지만 베트남인)은 모두 난민 지위와 그들이 비자발 이민자라는 사실 때문에 상대적으로 낮은 성취율을 가지고 있습니다.[260]

사회적, 경제적 격차

2015년, 아시아계 미국인 소득은 모든 아시아 민족을 전체적으로 그룹화했을 때 다른 모든 인종 그룹을 능가하는 것으로 나타났습니다.[261] 그러나 2014년 인구조사국의 보고서에 따르면 아시아계 미국인의 12%가 빈곤선 이하에서 살고 있는 반면, 비히스패닉계 백인 미국인의 10.1%가 빈곤선 이하에서 살고 있다고 합니다.[262][263] 2017년 아시아계 미국인의 부의 불평등에 대한 연구는 히스패닉이 아닌 백인 미국인에 비해 부유한 아시아계 미국인과 부유하지 않은 아시아계 미국인 사이에 더 큰 격차를 발견했습니다.[264] 출생 국가 및 기타 인구 통계학적 요인을 고려하면 아시아계 미국인을 구성하는 하위 그룹의 일부가 비히스패닉 백인 미국인보다 빈곤 상태에서 살 가능성이 훨씬 더 높습니다.[265][266][267][268] 의료 접근성은 미국의 인종과 민족에 따라 크게 다릅니다. 일부 평생 질병과 장애는 다른 미국 인구 조사에서 인정받은 인종 그룹에 비해 아시아계 미국인에게 더 부정적인 영향을 미칩니다.[240] 연구에 따르면 미국의 다양한 인종과 민족 사이에 많은 건강 차이가 있다고 합니다.[269]

아시아계 미국인들은 특정 민족을 조사할 때 큰 차이가 있습니다. 예를 들어, 2012년 아시아계 미국인들은 미국의 모든 인종 인구학에서 가장 높은 교육 수준을 보였습니다.[76] 하지만, 아시아계 미국인들의 많은 하위 그룹들이 교육적인 면에서 어려움을 겪고 있고, 일부 하위 그룹들은 높은 학교 중퇴율을 보이고 있거나 대학 교육을 받지 못하고 있습니다.[267][268][270] 이것은 가구 소득 측면에서도 발생합니다. 2008년 아시아계 미국인은 모든 인종 인구 통계에서 가구 소득의 중앙값이 가장 높았고,[271][272] 반면 평균 중앙값 소득이 미국 평균과 히스패닉계가 아닌 백인보다 낮은 아시아계 하위 그룹이 있었습니다.[267] 2014년 미국 인구조사국이 발표한 자료에 따르면 5개의 아시아계 미국인 집단이 미국 전체에서 1인당 소득이 가장 낮은 상위 10위 안에 든다고 합니다.[273]

The Asian American groups that have low educational attainment and high rates of poverty both in average individual and median income are Bhutanese Americans,[274][275] Bangladeshi Americans,[263][274][276] Cambodian Americans,[266][268] Burmese Americans,[267] Nepali Americans,[277] Hmong Americans,[263][268][274] and Laotian Americans.[268] 이는 베트남 출신 미국인들에게도 영향을 미치지만, 21세기 초 베트남에서 온 이민은 거의 완전히 난민 출신이 아니기 때문입니다.[278] 이러한 개별 민족은 공동체 내에서 사회적 문제를 경험하며, 일부는 개별 공동체 자체에 특정됩니다. 자살, 범죄, 정신 질환 등의 문제.[279] 다른 문제로는 추방, 신체 건강 악화 등이 있습니다.[280] 부탄 미국인 공동체 내에서 세계 평균보다 더 많은 자살 문제가 발생하고 있는 것으로 기록되었습니다.[281] 난민으로 이민 온 캄보디아계 미국인들은 추방 대상입니다.[282] 캄보디아, 라오스, 흐몽, 베트남계 미국인과 같은 난민 배경의 아시아계 미국인들 사이에서 범죄와 집단 폭력은 흔한 사회적 이슈입니다.[283]

참고 항목

메모들

참고문헌

- ^ "Asian and Pacific Islander Population in the United States census.gov". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on March 21, 2021. Retrieved February 14, 2021.

- ^ "僑委會全球資訊網". Archived from the original on September 16, 2012.

- ^ "S0201: selected population profile in the United States". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved October 17, 2022.

- ^ "Indo-Caribbean Times December 2007 - Kidnapping - Venezuela". Scribd. Retrieved August 17, 2018.

- ^ "Mien Farmers Make a Garden Grow in East Oakland". KQED News. Archived from the original on May 24, 2012.

- ^ Bureau, U.S. Census. "American FactFinder - Results". Factfinder.census.gov. Archived from the original on December 29, 2014. Retrieved January 9, 2018.

- ^ Baseline Study of Tibetan Diaspora Community Outside South Asia (PDF) (Report). The Central Tibetan Administration. September 2020. p. 45. Retrieved September 26, 2020.

- ^ "Asian Americans: A Mosaic of Faiths". The Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life. Pew Research Center. July 19, 2012. Archived from the original on July 16, 2013. Retrieved February 15, 2013.

Christian 42%, Buddhist 14%, Hindu 10%, Muslim 4%, Sikh 1%, Jain *% Unaffiliated 26%, Don't know/Refused 1%

- ^ Karen R. Humes; Nicholas A. Jones; Roberto R. Ramirez (March 2011). "Overview of Race and Hispanic Origin: 2010" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. U.S. Department of Commerce. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 3, 2014. Retrieved January 5, 2012.

- ^ a b "State & Country QuickFacts: Race". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on November 30, 2009. Retrieved August 31, 2009.

- ^ a b c 미국 인구조사국, 2000 인구조사, 공법 94-171 Redistricting 데이터 파일.Wayback Machine에서의 레이스(2001년 11월 3일 아카이브). (2001년 11월 3일 원본에서 보관).

- ^ a b Cortellessa, Eric (October 23, 2016). "Israeli, Palestinian Americans could share new 'Middle Eastern' census category". Times of Israel. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved April 22, 2018.

Nussbaum Cohen, Debra (June 18, 2015). "New U.S. Census Category to Include 'Israeli' Option". Haaretz. Archived from the original on July 10, 2017. Retrieved April 22, 2018.

- ^ a b c 미국 센서스국, 센서스 2000 요약 파일 1 기술 문서 2017년 7월 22일, Wayback Machine, 2001, 부록 B-14에 보관되어 있습니다. "예를 들어 캄보디아, 중국, 인도, 일본, 한국, 말레이시아, 파키스탄, 필리핀 제도, 태국, 베트남을 포함한 극동, 동남아시아 또는 인도 아대륙의 원래 민족에 기원을 둔 사람. 아시아 인도인, 중국인, 필리핀인, 한국인, 일본인, 베트남인 및 기타 아시아인이 포함됩니다."

- ^ "Table 1 – Population By Race: 2010 and 2020" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 16, 2022.

- ^ Caitlin Brophy (December 23, 2020). "Asian American Population in the United States Continues to Grow Origin: 2020".

- ^ "U.S. Census Show Asians Are Fastest Growing Racial Group". NPR. Archived from the original on December 24, 2017. Retrieved October 26, 2016.

- ^ a b K. Connie Kang (September 7, 2002). "Yuji Ichioka, 66; Led Way in Studying Lives of Asian Americans". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 14, 2014. Retrieved May 4, 2013.

Yet Ichioka created the first inter-ethnic pan-Asian American political group. And he coined the term "Asian American" to frame a new self-defining political lexicon. Before that, people of Asian ancestry were generally called Oriental or Asiatic.

- ^ Mio, Jeffrey Scott, ed. (1999). Key Words in Multicultural Interventions: A Dictionary. ABC-Clio ebook. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 20. ISBN 9780313295478. Archived from the original on January 3, 2016. Retrieved August 19, 2014.

The use of the term Asian American began in the late 1960s alongside the civil rights movement (Uba, 1994) and replaced disparaging labels of Oriental, Asiatic, and Mongoloid.

- ^ Lee, Jennifer; Ramakrishnan, Karthick (October 14, 2019). "Who counts as Asian" (PDF). Russellsage.org. p. 4. Retrieved July 7, 2021.

- ^ '아시아배제리그 진행' 아시아배제리그 샌프란시스코: 1910년 4월. 페이지 7. "미국 개정 법령 제216조를 개정하는 것. 미국 상하원이 의회에서 소집하여 제정한 것이든, 미국 개정 법령 제29조는 다음과 같이 추가하여 개정합니다. 그리고 아르메니아인, 아시리아인, 유대인을 제외한 몽골인, 말레이시아인, 기타 아시아인들은 미국으로 귀화해서는 안 됩니다."

- ^ 미국 법원이 2014년 8월 11일 웨이백 머신에 보관된 화이트 레이스를 설립한 방법

- ^ Kambhampaty, Anna Purna (May 22, 2020). "In 1968, These Activists Coined the Term 'Asian American'—And Helped Shape Decades of Advocacy". Time. Archived from the original on June 1, 2020. Retrieved January 29, 2023.

- ^ Maeda, Daryl Joji (2012). Rethinking the Asian American Movement. New York: Routledge. pp. 9–13, 18, 26, 29, 32–35, 42–48, 80, 108, 116–117, 139. ISBN 978-0-415-80081-5.

- ^ Yen Espiritu (January 19, 2011). Asian American Panethnicity: Bridging Institutions and Identities. Temple University Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-4399-0556-2. Archived from the original on May 30, 2020. Retrieved April 19, 2019.

- ^ Gayla, Marella (October 20, 2021). "Searching for Coherence in Asian America". The New Yorker. New York. Retrieved July 10, 2022.

The term "Asian American" emerged from the radical student movements of the late nineteen-sixties, most notably at San Francisco State College and the University of California, Berkeley. The activists, modelling their work after Black and Latinx liberation movements, hoped to create a pan-Asian coalition that would become part of an international struggle against empire and capitalism.

- ^ 찬디, 수누피. 유효한 남아시아 투쟁이란 무엇인가요? 2006년 12월 5일, Wayback Machine Report on the Annual SASA Conference. 2021년 7월 13일 회수.

- ^ Chin, Gabriel J. (April 18, 2008). "The Civil Rights Revolution Comes to Immigration Law: A New Look at the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965". SSRN 1121504.

{{cite journal}}: 저널 인용 요구사항journal=(도와주세요) - ^ Robert M. Jiobu (1988). Ethnicity and Assimilation: Blacks, Chinese, Filipinos, Koreans, Japanese, Mexicans, Vietnamese, and Whites. SUNY Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-88706-647-4. Archived from the original on June 1, 2020. Retrieved March 28, 2018.

Chang, Benjamin (February 2017). "Asian Americans and Education". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education. 1. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.102. ISBN 9780190264093. Archived from the original on March 28, 2018. Retrieved March 27, 2018. - ^ a b Sailer, Steve (July 11, 2002). "Feature: Who exactly is Asian American?". UPI. Los Angeles. Archived from the original on September 5, 2018. Retrieved September 4, 2018.

- ^ "Asian American". Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on March 26, 2021. Retrieved March 29, 2011.

- ^ "Asian". AskOxford.com. Archived from the original on April 15, 2008. Retrieved September 29, 2007.[전체 인용 필요]

- ^ 2016년 5월 12일 웨이백 머신에 보관된 에피칸탈 폴드: 메디슨 플러스 의학 백과사전은 모든 아시아인들에게 정상이라고 가정하고 "아시아계 사람들에게 에피칸탈 주름의 존재는 정상이다"라고 말합니다.

Kawamura, Kathleen (2004). "Chapter 28. Asian American Body Images". In Thomas F. Cash; Thomas Pruzinsky (eds.). Body Image: A Handbook of Theory, Research, and Clinical Practice. Guilford Press. pp. 243–249. ISBN 978-1-59385-015-9. Archived from the original on May 30, 2020. Retrieved October 16, 2015. - ^ "American Community Survey; Puerto Rico Community Survey; 2007 Subject Definitions" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau: 31.

{{cite journal}}: 저널 인용 요구사항journal=(도와주세요)[데드링크]

"American Community Survey; Puerto Rico Community Survey; 2007 Subject Definitions" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved April 11, 2011.[영구적 데드링크]

"American Community Survey and Puerto Rico Community Survey: 2017 Code List" (PDF). Code Lists, Definitions, and Accuracy. U.S. Department of Commerce. 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 1, 2020. Retrieved May 3, 2019.

"American Community Survey and Puerto Rico Community Survey: 2017 Subject Definitions" (PDF). Code Lists, Definitions, and Accuracy. U.S. Department of Commerce. 2017. pp. 114–116. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 5, 2019. Retrieved May 4, 2019.Asian. A person having origins in any of the original peoples of the Far East, Southeast Asia, or the Indian subcontinent including, for example, Cambodia, China, India, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, Pakistan, the Philippine Islands, Thailand, and Vietnam. It includes people who indicate their race as "Asian Indian", "Chinese", "Filipino", "Korean", "Japanese", "Vietnamese", and "Other Asian" or provide other detailed Asian responses.

- ^ 코넬 아시아계 미국인 연구2008년 5월 9일, Wayback Machine에 보관되었으며, 남아시아인에 대한 언급이 포함되어 있습니다.

UC Berkeley – General Catalog – 아시아계 미국인 연구 과정2008년 12월 21일 Wayback Machine에서 아카이브됨, 남아시아 및 동남아시아 강좌 개설

"Asian American Studies". 2009–2011 Undergraduate Catalog. University of Illinois at Chicago. 2009. Archived from the original on June 7, 2011. Retrieved April 11, 2011.

"Welcome to Asian American Studies". Asian American Studies. California State University, Fullerton. 2003. Archived from the original on July 11, 2012. Retrieved April 11, 2011.

"Program". Asian American Studies. Stanford University. Archived from the original on January 10, 2011. Retrieved April 11, 2011.

"About Us". Asian American Studies. Ohio State University. 2007. Archived from the original on August 11, 2011. Retrieved April 11, 2011.

"Welcome". Asian and Asian American Studies Certificate Program. University of Massachusetts Amherst. 2011. Archived from the original on December 23, 2011. Retrieved April 11, 2011.

"Overview". Cornell University Asian American Studies Program. Cornell University. 2007. Archived from the original on June 15, 2012. Retrieved April 11, 2011. - ^ "COMPARATIVE ENROLLMENT BY RACE/ETHNIC ORIGIN" (PDF). Diversity and Inclusion Office. Ferris State University. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved August 9, 2014.

original peoples of Europe, North Africa, or the Middle East.

"Not Quite White: Race Classification and the Arab American Experience". Arab American Institute. Arab Americans by the Center for Contemporary Arab Studies, Georgetown University. April 4, 1997. Archived from the original on August 26, 2014. Retrieved August 9, 2014.

Ian Haney Lopez (1996). "How the U.S. Courts Established the White Race". Model Minority. New York University Press. Archived from the original on August 11, 2014. Retrieved August 9, 2014.

"Race". United States Census Bureau. U.S. Department of Commerce. 2010. Archived from the original on July 16, 2014. Retrieved August 9, 2014.White. A person having origins in any of the original peoples of Europe, the Middle East, or North Africa. It includes people who indicate their race as "White" or report entries such as Irish, German, Italian, Lebanese, Arab, Moroccan, or Caucasian.

Kleinyesterday, Uri (June 18, 2015). "New U.S. census category to include 'Israeli' option - Jewish World Features - Haaretz - Israel News". Haaretz. Archived from the original on September 11, 2016. Retrieved February 27, 2017.

"Public Comments Received on Federal Register notice 79 FR 71377 : Proposed Information Collection; Comment Request; 2015 National Content Test : U.S. Census Bureau; Department of Commerce : December 2, 2014 – February 2, 2015" (PDF). Census.gov. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 26, 2017. Retrieved February 27, 2017. - ^ "COMPARATIVE ENROLLMENT BY RACE/ETHNIC ORIGIN" (PDF). Diversity and Inclusion Office. Ferris State University. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 24, 2015. Retrieved August 9, 2014.

original peoples of Europe, North Africa, or the Middle East.

- ^ 1980년 인구조사: 응답자에게 보내는 지침 2006년 11월 30일, Minnesota 대학, University of Minnesota Population Center, Integrated Public Use Microdata Series에 의해 재발행된 Wayback Machine http://www.ipums.org 에서 2006년 11월 19일에 액세스된 Wayback Machine에서 2013년 7월 11일에 아카이브되었습니다.

- ^ 리, 고든. 하이픈 잡지 2003. 2007년 1월 28일(2008년 3월 17일 Wayback Machine에서 2007년 10월 2일 원본 Archive에서 아카이브됨).

- ^ Wu, Frank H. Wu (2003). Yellow: race in America beyond black and white. New York: Basic Books. p. 310. ISBN 9780465006403. Retrieved April 15, 2011.

- ^ 1990년 인구조사: 응답자에게 보내는 지침 2012년 4월 6일, Minnesota University of Minnesota, University of Minnesota Population Center, http://wwww.ipums.orgArchived 2013년 7월 11일, 2006년 11월 19일에 액세스한 Wayback Machine에서 다시 출판되었습니다.

리브스, 테런스 클라우뎃, 베넷 미국 인구조사국입니다. 아시아 태평양 섬 인구: 2002년 3월 Wayback Machine에서 2021년 1월 10일 보관. 2003. 2006년 9월 30일. - ^ "Census Data / API Identities Research & Statistics Resources Publications Research Statistics Asian Pacific Institute on Gender-Based Violence". www.api-gbv.org. Archived from the original on June 9, 2016. Retrieved May 27, 2016.

- ^ 우드, 다니엘 B "누가 미국인인가에 대한 공통된 근거" 2007년 2월 8일, Wayback Machine Christian Science Monitor에 보관되었습니다. 2006년 1월 19일. 2007년 2월 16일 회수.

- ^ Mary Frauenfelder. "Asian-Owned Businesses Nearing Two Million". census.gov. Archived from the original on July 19, 2018. Retrieved May 15, 2018.

- ^ Ruiz, Neil G.; Noe-Bustamante, Luis; Shah, Sono (May 8, 2023). "Diverse Cultures and Shared Experiences Shape Asian American Identities". Pew Research Center. Retrieved May 11, 2023.

- ^ "Searching For Asian America. Community Chats - PBS". pbs.org. Archived from the original on November 4, 2015. Retrieved November 22, 2017.

- ^ S. D. Ikeda. "What's an "Asian American" Now, Anyway?". Archived from the original on June 10, 2011.

- ^ Yang, Jeff (October 27, 2012). "Easy Tiger (Nation)". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on March 16, 2013. Retrieved February 19, 2013.

- ^ Park, Jerry Z. (August 1, 2008). "Second-Generation Asian American Pan-Ethnic Identity: Pluralized Meanings of a Racial Label". Sociological Perspectives. 51 (3): 541–561. doi:10.1525/sop.2008.51.3.541. S2CID 146327919. Archived from the original on March 26, 2021. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

- ^ Sailer, Steve (July 11, 2002). "Feature: Who exactly is Asian American?". UPI. Los Angeles. Archived from the original on September 5, 2018. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

It is a political term used by Asian-American activists and enhanced by governmental treatment. In terms of culture, physical characteristics, and pre-migrant historical experiences, I have argued, South and East Asians do not have commonalities and as a result, they do not maintain close ties in terms friendship, intermarriage or sharing neighborhoods

- ^ Sailer, Steve (July 11, 2002). "Feature: Who exactly is Asian American?". UPI. Los Angeles. Archived from the original on September 5, 2018. Retrieved July 8, 2021.

Dinesh D'Souza ... told United Press International, "Middle Eastern culture has some similarities (religion, cuisine, taste in music and movies) with Asian Indian culture, but very few with Oriental (Far Eastern) culture."

- ^ Lee, S.S., Mountain, J. & Koenig, B.A. (2001). 새로운 유전체학에서 인종의 의미: 건강불균형 연구에 대한 시사점. 예일 보건 정책, 법, 윤리 저널 1 (1). 43, 44, 45페이지. Wayback Machine 링크입니다.

- ^ Sailer, Steve (July 11, 2002). "Feature: Who exactly is Asian American?". UPI. Los Angeles. Archived from the original on September 5, 2018. Retrieved July 8, 2021.

The most common justification advanced for federal government's clustering together South Asians and East Asians is that Buddhism originated in India.

- ^ a b Han, Chong-Suk Winter (2015). Geisha of a Different Kind: Race and Sexuality in Gaysian America. New York: New York University Press. p. 4.

- ^ Kambhampaty, Anna Purna (March 12, 2020). "At Census Time, Asian Americans Again Confront the Question of Who 'Counts' as Asian. Here's How the Answer Got So Complicated". Time. Retrieved July 9, 2021.

But American culture tends not to think of all regions in Asia as equally Asian. A quick Google search of "Asian food nearby" is likely to call up Chinese or Japanese restaurants, but not Indian or Filipino. Years after someone posted a thread on College Confidential, a popular college admissions forum, titled "Do Indians count as Asians?" the SAT in 2016 tweaked its race categories, explaining to test-takers that "Asian" did include "Indian subcontinent and Philippines origin."

- ^ Schiavenza, Matt (October 19, 2016). "Why Some 'Brown Asians' Feel Left Out of the Asian American Conversation". Asia Society. Retrieved September 9, 2022.

It's one of the reasons many brown Asians do not identify as Asian Americans. Perhaps we just don't feel connected to East Asian people, cultures, and lived realities. Perhaps we also don't feel welcomed and included.

- ^ Schiavenza, Matt (October 19, 2016). "Why Some 'Brown Asians' Feel Left Out of the Asian American Conversation". Asia Society. Retrieved September 9, 2022.

And that, unfortunately, did not include any South Asians and only one Filipino. That caused a bit of an outcry. It raises a legitimate issue, of course, one about how 'brown Asians' often feel excluded from the Asian American conversation.

- ^ Nadal, Kevin L (February 2, 2020). "The Brown Asian American Movement: Advocating for South Asian, Southeast Asian, and Filipino American Communities". Asian American Policy Review. 29. Retrieved September 9, 2022.

South Asian Americans have shared how they are excluded from the Asian American umbrella because of their cultural, religious, and racial/phenotypic differences – resulting in lack of representation in Asian American Studies, narratives, and media representations.

- ^ Barringer, Felicity (March 2, 1990). "Asian Population in U.S. Grew by 70% in the 80's". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 21, 2013. Retrieved January 10, 2013.

Lowe, Lisa (2004). "Heterogeneity, Hybridity, Multiplicity: Marking Asian American Differences". In Ono, Kent A. (ed.). A Companion to Asian American Studies. Blackwell Companions in Cultural Studies. John Wiley & Sons. p. 272. ISBN 978-1-4051-1595-7. Archived from the original on January 16, 2017. Retrieved January 10, 2013.Alt URL은 2013년 9월 21일 Wayback Machine에 입고되었습니다. - ^ Skop, Emily; Li, Wei (2005). "Asians In America's Suburbs: Patterns And Consequences of Settlement". The Geographical Review. 95 (2): 168. doi:10.1111/j.1931-0846.2005.tb00361.x. S2CID 162228375.

- ^ Fehr, Dennis Earl; Fehr, Mary Cain (2009). Teach boldly!: letters to teachers about contemporary issues in education. Peter Lang. p. 164. ISBN 978-1-4331-0491-6. Archived from the original on March 26, 2021. Retrieved March 6, 2012.

Raymond Arthur Smith (2009). "Issue Brief #160: Asian American Protest Politics: "The Politics of Identity"" (PDF). Majority Rule and Minority Rights Issue Briefs. Columbia University. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 21, 2013. Retrieved March 6, 2012. - ^ Lott, Juanita Tamayo (January 9, 2004). Asian-American Children Are Members of a Diverse and Urban Population (Report). Population Reference Bureau. Archived from the original on April 7, 2018. Retrieved April 6, 2018.

Hune, Shirley (April 16, 2002). "Demographics and Diversity of Asian American College Students". New Directions for Student Services. 2002 (97): 11–20. doi:10.1002/ss.35.

Franklin Ng (1998). The History and Immigration of Asian Americans. Taylor & Francis. p. 211. ISBN 978-0-8153-2690-8. Archived from the original on June 4, 2020. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

Xue Lan Rong; Judith Preissle (September 26, 2008). Educating Immigrant Students in the 21st Century: What Educators Need to Know. SAGE Publications. p. 133. ISBN 978-1-4522-9405-6. Archived from the original on June 1, 2020. Retrieved April 7, 2018. - ^ Wile, Rob (June 26, 2016). "Latinos are no longer the fastest-growing racial group in America". Fusion. Doral, Florida. Archived from the original on April 7, 2017. Retrieved May 3, 2017.

- ^ a b c "Asian/Pacific American Heritage Month: May 2012". United States Census Bureau. United States Department of Commerce. March 21, 2012. Archived from the original on January 6, 2013. Retrieved January 12, 2013.

- ^ a b Timothy Pratt (October 18, 2012). "More Asian Immigrants Are Finding Ballots in Their Native Tongue". The New York Times. Las Vegas. Archived from the original on December 25, 2012. Retrieved January 12, 2013.

- ^ Jonathan H. X. Lee; Kathleen M. Nadeau (2011). Encyclopedia of Asian American Folklore and Folklife. ABC-CLIO. pp. 333–334. ISBN 978-0-313-35066-5. Archived from the original on April 25, 2017. Retrieved September 28, 2017.

Since the Philippines was colonized by Spain, Filipino Americans in general can speak and understand Spanish too.

- ^ Leslie Berestein Rojas (November 6, 2012). "Five new Asian languages make their debut at the polls". KPCC. Archived from the original on June 10, 2015. Retrieved January 12, 2013.

- ^ Shaun Tandon (January 17, 2013). "Half of Asian Americans rely on ethnic media: poll". Agence France-Presse. Retrieved January 25, 2013.

- ^ "Language Use and English-Speaking Ability: 2000: Census 2000 Brief" (PDF). census.gov. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 18, 2008. Retrieved November 22, 2017.

- ^ EAC, 아시아계 미국인 대다수가 투표를 보다 쉽게 할 수 있도록 5개의 아시아 언어 번역본으로 된 선거 용어집 발행 선거지원위원회. 2008. 6. 20. (2008. 7. 31. 원본에서 보관)

- ^ a b Mohamed, Besheer; Rotolo, Michael (October 11, 2023). "Religion Among Asian Americans". Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. Retrieved October 14, 2023.

- ^ "아시아계 미국인들: 신앙의 모자이크"(개요)(보관). 퓨 리서치. 2020년 7월 19일. 2020년 5월 3일에 검색되었습니다.

- ^ a b c Mohamed, Besheer; Rotolo, Michael (October 11, 2023). "1. Christianity among Asian Americans". Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. Retrieved October 14, 2023.

- ^ a b c Mohamed, Besheer; Rotolo, Michael (October 11, 2023). "6. Religiously unaffiliated Asian Americans". Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. Retrieved October 14, 2023.

- ^ 레펠, 그레고리 P. Faith Seeking Action: 2020년 5월 29일 웨이백 머신에 보관된 미션, 사회운동, 그리고 움직이는 교회. 허수아비 출판사, 2007. ISBN 1461658578 페이지 39

- ^ 소여, 메리 R. 여백의 교회: 살아있는 기독교 공동체, 웨이백 머신에 보관 2020년 5월 31일. A&C Black, 2003. ISBN 1563383667. p. 156

- ^ a b c d Taylor, Paul; D'Vera Cohn; Wendy Wang; Jeffrey S. Passel; Rakesh Kochhar; Richard Fry; Kim Parker; Cary Funk; Gretchen M. Livingston; Eileen Patten; Seth Motel; Ana Gonzalez-Barrera (July 12, 2012). "The Rise of Asian Americans" (PDF). Pew Research Social & Demographic Trends. Pew Research Center. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 5, 2016. Retrieved January 28, 2013.

- ^ Gonzalez, Joaquin (2009). Filipino American Faith in Action: Immigration, Religion, and Civic Engagement. NYU Press. pp. 21–22. ISBN 9780814732977. Archived from the original on March 26, 2021. Retrieved May 11, 2013.

San Juan, E. Jr. (2009). "Emergency Signals from the Shipwreck". Toward Filipino Self-Determination. SUNY series in global modernity. SUNY Press. pp. 101–102. ISBN 9781438427379. Archived from the original on March 26, 2021. Retrieved May 11, 2013. - ^ Martha W. McCartney; Lorena S. Walsh; Ywone Edwards-Ingram; Andrew J. Butts; Beresford Callum (2003). "A Study of the Africans and African Americans on Jamestown Island and at Green Spring, 1619–1803" (PDF). Historic Jamestowne. National Park Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 4, 2012. Retrieved May 11, 2013.

Francis C. Assisi (May 16, 2007). "Indian Slaves in Colonial America". India Currents. Archived from the original on November 27, 2012. Retrieved May 11, 2013. - ^ Okihiro, Gary Y. (2005). The Columbia Guide To Asian American History. Columbia University Press. p. 178. ISBN 9780231115117. Archived from the original on March 26, 2021. Retrieved May 10, 2013.

- ^ "Filipinos in Louisiana". PBS. Archived from the original on March 21, 2012. Retrieved January 5, 2011.

- ^ Wachtel, Alan (2009). Southeast Asian Americans. Marshall Cavendish. p. 80. ISBN 978-0-7614-4312-4. Archived from the original on March 26, 2021. Retrieved December 5, 2010.

- ^ John E. Van Sant (2000). Pacific Pioneers: Japanese Journeys to America and Hawaii, 1850-80. University of Illinois Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-252-02560-0. Archived from the original on January 3, 2016. Retrieved October 16, 2015.

Sang Chi; Emily Moberg Robinson (January 2012). Voices of the Asian American and Pacific Islander Experience. ABC-CLIO. p. 377. ISBN 978-1-59884-354-5. Archived from the original on January 3, 2016. Retrieved October 16, 2015.

Joseph Nathan Kane (1964). Famous first facts: a record of first happenings, discoveries and inventions in the United States. H. W. Wilson. p. 161. Archived from the original on May 10, 2016. Retrieved October 16, 2015. - ^ Wai-Jane Cha. "Chinese Merchant-Adventurers and Sugar Masters in Hawaii: 1802–1852" (PDF). University of Hawaii at Manoa. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 18, 2009. Retrieved January 14, 2011.

- ^ Xiaojian Zhao; Edward J.W. Park Ph.D. (November 26, 2013). Asian Americans: An Encyclopedia of Social, Cultural, Economic, and Political History [3 volumes]: An Encyclopedia of Social, Cultural, Economic, and Political History. ABC-CLIO. pp. 357–358. ISBN 978-1-59884-240-1. Archived from the original on January 3, 2016. Retrieved October 16, 2015.

- ^ 로널드 타카키, 다른 해안에서 온 낯선 사람들: 아시아계 미국인의 역사 (2회차. 1998) 133-78쪽

- ^ The Office of Multicultural Student Services (1999). "Filipino Migrant Workers in California". University of Hawaii. Archived from the original on December 4, 2014. Retrieved January 12, 2011.

Castillo, Adelaida (1976). "Filipino Migrants in San Diego 1900–1946". The Journal of San Diego History. San Diego Historical Society. 22 (3). Archived from the original on June 4, 2011. Retrieved January 12, 2011. - ^ "Center for Okinawan Studies". Archived from the original on January 1, 2020. Retrieved January 11, 2020.

- ^ L. Scott Miller (1995). An American Imperative: Accelerating Minority Educational Advancement. Yale University Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-300-07279-2. Archived from the original on January 3, 2016. Retrieved October 16, 2015.

- ^ Richard T. Schaefer (March 20, 2008). Encyclopedia of Race, Ethnicity, and Society. SAGE Publications. p. 872. ISBN 978-1-4522-6586-5. Archived from the original on January 3, 2016. Retrieved October 16, 2015.

- ^ Stephanie Hinnershitz-Hutchinson (May 2013). "The Legal Entanglements of Empire, Race, and Filipino Migration to the United States". Humanities and Social Sciences Net Online. Archived from the original on August 8, 2014. Retrieved August 7, 2014.

Baldoz, Rick (2011). The Third Asiatic Invasion: Migration and Empire in Filipino America, 1898–1946. NYU Press. p. 204. ISBN 9780814709214. Archived from the original on March 26, 2021. Retrieved August 7, 2014. - ^ "Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America (Politics and Society in Twentieth-Century America) eBook: Mae M. Ngai: Books". www.amazon.com. Archived from the original on March 11, 2021. Retrieved February 21, 2016.

- ^ Elliott Robert Barkan (January 17, 2013). Immigrants in American History: Arrival, Adaptation, and Integration [4 volumes]: Arrival, Adaptation, and Integration. ABC-CLIO. p. 301. ISBN 978-1-59884-220-3. Archived from the original on May 28, 2020. Retrieved March 17, 2018.

- ^ Soodalter, Ron (2016). "By Soil Or By Blood". American History. 50 (6): 56–63.

외교관 자녀는 포함하지 않습니다. - ^ 타카키, 다른 해안에서 온 낯선 사람들: 아시아계 미국인의 역사 (1998) 370-78쪽

- ^ Rothman, Lily; Ronk, Liz (February 2, 2017). "Congress Tightened Immigration Laws 100 Years Ago. Here's Who They Turned Away". Time. Archived from the original on June 30, 2020. Retrieved March 14, 2019.

Excluded from entry in 1917 were not only convicted criminals, chronic alcoholics and people with contagious diseases, but also people with epilepsy, anarchists, most people who couldn't read and almost everyone from Asia, as well as laborers who were "induced, assisted, encouraged, or solicited to migrate to this country by offers or promises of employment, whether such offers or promises are true or false" and "persons likely to become a public charge".

Boissoneault, Lorraine (February 6, 2017). "Literacy Tests and Asian Exclusion Were the Hallmarks of the 1917 Immigration Act". Smithsonian. Archived from the original on March 19, 2019. Retrieved March 14, 2019.The act also levied an $8 tax on every adult immigrant (about $160 today) and barred all immigrants from the "Asiatic zone".

Little, Becky (September 7, 2017). "The Birth of 'Illegal' Immigration". History. Archived from the original on March 14, 2019. Retrieved March 14, 2019.A decade later, the Asiatic Barred Zone Act banned most immigration from Asia, as well as immigration by prostitutes, polygamists, anarchists, and people with contagious diseases.

1917년 의회기록, 제63권, 876페이지 (1917년 2월 5일)

Uma A. Segal (August 14, 2002). A Framework for Immigration: Asians in the United States. Columbia University Press. p. 134. ISBN 978-0-231-50633-5. Archived from the original on June 4, 2020. Retrieved March 15, 2019.Less than ten years later, Congress passed the Immigration Act of February 5, 1917 (commonly known as the Barred Zone Act), which enumerated the classes of people who were ineligible to enter the United States. Among them were those who were natives of a zone defined by latitude and longitude the geographic area identified became known as the Asiatic Barred Zone, and the act clearly became the Asiatic Barred Zone Act. Under the Asiatic Barred Zone Act, the only Asians allowed entry into the United States were Japanese and Filipinos.

Sixty-Fourth Congress (February 5, 1917). "CHAP. 29. - An Act To regulate the immigration of aliens to, and the residence of aliens in, the United States" (PDF). Library of Congress. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 12, 2019. Retrieved March 14, 2019.unless otherwise provided for by existing treaties, persons who are natives of islands not possessed by the United States adjacent to the Content of Asia, situate south of the twentieth parallel latitude north, west of the one hundred and sixtieth meridian of longitude east of Greenwich, and north of the tenth parallel of latitude south, or who are natives of any country, province, or dependency situate on the Continent of Asia west of the one hundred and tenth meridian of longitude east from Greenwich and east of the fiftieth meridian of longitude east from Greenwich and south of the fiftieth parallel of latitude north, except that portion of said territory situate between the fiftieth and the sixty-fourth meridians of longitude east from Greenwich and the twenty-fourth and thirty-eighth parallels of latitude north, and no alien now in any way excluded from, or prevented from entering, the United States shall be admitted to the United States.

Alt URL은 2019년 5월 8일 Wayback Machine에 도착했습니다. - ^ Franks, Joel (2015). "Anti-Asian Exclusion In The United States During The Nineteenth And Twentieth Centuries: The History Leading To The Immigration Act Of 1924". Journal of American Ethnic History. 34 (3): 121–122. doi:10.5406/jamerethnhist.34.3.0121.

타카키, 다른 해안에서 온 낯선 사람들: 아시아계 미국인의 역사 (1998) pp 197–211 - ^ "Executive Order 9066: Resulting in Japanese-American Incarceration (1942)". National Archives. September 22, 2021.

- ^ Elaine Howard Ecklund; Jerry Z. Park. "Asian American Community Participation and Religion: Civic "Model Minorities?"". Project MUSE. Baylor University. Archived from the original on March 14, 2014. Retrieved March 7, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e Jie Zong & Jeanne Batalova, 2017년 4월 30일, Wayback Machine, Migration Policy Institute (2016년 1월 6일)에 보관된 미국의 아시아 이민자.

- ^ Semple, Kirk (January 8, 2013). "Asian-Americans Gain Influence in Philanthropy". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 15, 2013. Retrieved March 3, 2013.

From 2000-2010, according to the Census Bureau, the number of people who identified themselves as partly or wholly Asian grew by nearly 46%, more than four times the growth rate of the overall population, making Asian-Americans the fastest-growing racial group in the nation.

- ^ Semple, Ken (June 18, 2012). "In a Shift, Biggest Wave of Migrants Is Now Asian". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 26, 2021. Retrieved May 3, 2017.

"New Asian 'American Dream': Asians Surpass Hispanics in Immigration". ABC News. United States News. June 19, 2012. Archived from the original on April 23, 2018. Retrieved May 3, 2017.

Jonathan H. X. Lee (January 16, 2015). History of Asian Americans: Exploring Diverse Roots: Exploring Diverse Roots. ABC-CLIO. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-313-38459-2. Archived from the original on May 30, 2020. Retrieved May 3, 2017. - ^ Rivitz, Jessica (September 28, 2015). "Asians on pace to overtake Hispanics among U.S. immigrants, study shows". CNN. Atlanta. Archived from the original on June 7, 2017. Retrieved May 3, 2017.

- ^ Erika Lee, 현재 최대 규모의 미국 신규 입국자 그룹. 2017년 4월 19일, USA Today, Wayback Machine에서 보관(2015년 7월 7일).

- ^ a b Maeda, Daryl Joji (2016). "The Asian American Movement". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of American History. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199329175.013.21. ISBN 978-0-19-932917-5. Archived from the original on March 26, 2021. Retrieved February 23, 2019.

{{cite book}}:work=무시됨(도움말) - ^ Rhea, Joseph Tilden (May 1, 2001). Race Pride and the American Identity. Harvard University Press. p. 43. ISBN 9780674005761. Archived from the original on May 30, 2020. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- ^ 지니 숙 거센, "긍정적 행동과 아시아계 미국인에 대한 불편한 진실" 뉴요커 (2017)

- ^ 제니퍼 리, "아시아계 미국인 등록 유권자 69% 찬성" AAPI 데이터 (2022)

- ^ "아시아계 미국인의 70%는 긍정적인 행동을 지지합니다. 오해가 끊이지 않는 이유가 여기에 있습니다." NBC 뉴스(2020년 11월 14일).

- ^ We Are Samese Twins-Fai 的分裂生活 Archived at the Wayback Machine 2007년 12월 22일

- ^ Lee, Elizabeth (February 28, 2013). "YouTube Spawns Asian-American Celebrities". VAO News. Archived from the original on February 18, 2013. Retrieved March 4, 2013.

- ^ Chow, Kat (February 5, 2015). "A Brief, Weird History Of Squashed Asian-American TV Shows". NPR. Archived from the original on February 8, 2015. Retrieved February 8, 2015.

Cruz, Lenika (February 4, 2015). "Why There's So Much Riding on Fresh Off the Boat". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on February 7, 2015. Retrieved February 8, 2015.

Gamboa, Glenn (January 30, 2015). "Eddie Huang a fresh voice in 'Fresh Off the Boat'". Newsday. Long Island, New York. Archived from the original on February 7, 2015. Retrieved February 8, 2015.

Lee, Adrian (February 5, 2015). "Will Fresh Off The Boat wind up being a noble failure?". MacLeans. Canada. Archived from the original on February 8, 2015. Retrieved February 8, 2015.

Oriel, Christina (December 20, 2014). "Asian American sitcom to air on ABC in 2015". Asian Journal. Los Angeles. Archived from the original on February 7, 2015. Retrieved February 8, 2015.

Beale, Lewis (February 3, 2015). "The Overdue Asian TV Movement". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on February 11, 2015. Retrieved February 8, 2015.

Yang, Jeff (May 2, 2014). "Why the 'Fresh Off the Boat' TV Series Could Change the Game". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on May 12, 2014. Retrieved February 8, 2015.

Joann Faung Jean Lee (August 1, 2000). Asian American Actors: Oral Histories from Stage, Screen, and Television. McFarland. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-7864-0730-9. Archived from the original on April 27, 2016. Retrieved October 16, 2015.

Branch, Chris (February 5, 2015). "'Fresh Off The Boat' Brings Asian-Americans To The Table On Network TV". Huffington Post. Archived from the original on February 7, 2015. Retrieved February 8, 2015. - ^ "Hawai'i's Human Beatbox". University of Hawaiʻi Foundation Office of Alumni Relations. October 19, 2018. Archived from the original on January 31, 2021. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ^ "Kapiʻolani CC alum stays on beat spreading message of perseverance". University of Hawaiʻi News. December 13, 2018. Archived from the original on December 15, 2019. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ^ Yamashiro, Lexus (July 15, 2017). "KCC Alumnus Inspires Community Through Beatboxing, Motivational Speaking". Kapiʻo News. Archived from the original on January 29, 2021. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ^ Ching, Kapiʻolani (December 13, 2018). "Hawaiʻi's Human Beatbox". University of Hawaiʻi at Kapiʻolani Alumni. Archived from the original on January 30, 2021. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 main: 다중 이름: 저자 목록 (링크) CS1 main: 숫자 이름: 저자 목록 (링크) - ^ Lim, Woojin (January 21, 2021). "Jason Tom: Hawaii's Human Beatbox". The International Wave: A Collection of In-Depth Conversations With Artists of Asian Descent. Archived from the original on January 23, 2021. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ^ Hulme, Julia (January 25, 2016). "Jason Tom: The Human BeatBox". Millennial Magazine. Archived from the original on October 3, 2016. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ^ "100 Most Successful Asian American Entrepreneurs". Archived from the original on November 24, 2010. Retrieved November 3, 2010.

- ^ "Broad racial disparities persist". NBC News. November 14, 2006. Archived from the original on March 5, 2013. Retrieved December 18, 2006.

- ^ "Notable Asian American Professionals". Archived from the original on October 20, 2010. Retrieved November 3, 2010.

- ^ "How Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders Contribute to the U.S. Economy" (PDF). Partnership for a New American Economy Research Fund. October 2017. pp. 4, 12, 19. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 15, 2020. Retrieved February 15, 2020.

- ^ "Eric Yuan & family". Forbes.

- ^ Khan, Shahid. "Shahid Khan". Forbes.

- ^ Zhao, Xiaojian; Ph.D., Edward J.W. Park (November 26, 2013). "Conclusion". Asian Americans: An Encyclopedia of Social, Cultural, Economic, and Political History [3 volumes]: An Encyclopedia of Social, Cultural, Economic, and Political History. ABC-CLIO. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-59884-240-1. Archived from the original on June 1, 2020. Retrieved December 11, 2019.

Collet, Christian; Lien, Pei-Te (July 28, 2009). The Transnational Politics of Asian Americans. Temple University Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-1-59213-862-3. Archived from the original on June 1, 2020. Retrieved December 11, 2019. - ^ "U.S. Senate: Asian American, Pacific Islander, and Native Hawaiian Senators". www.senate.gov. Retrieved April 26, 2023.

- ^ a b Matt Stevens (February 11, 2020). "Andrew Yang Drops Out: 'It Is Clear Tonight From the Numbers That We Are Not Going to Win'". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 24, 2020. Retrieved February 15, 2020.

- ^ Kai-Hwa Wang, Francis (June 25, 2015). "Indian Americans React to Bobby Jindal Presidential Announcement". NBC News. Archived from the original on August 28, 2019. Retrieved August 20, 2019.

- ^ "Hiram L. Fong, 97, Senator From Hawaii in 60's and 70's". The New York Times. The Associated Press. August 19, 2004. Archived from the original on July 18, 2019. Retrieved August 20, 2019.

Zhao, Xiaojian; Park, Edward J.W. (November 26, 2013). Asian Americans: An Encyclopedia of Social, Cultural, Economic, and Political History. ABC-CLIO. p. 435. ISBN 978-1-59884-240-1. Archived from the original on May 30, 2020. Retrieved August 21, 2019. - ^ Wallace Turner (May 10, 1972). "Mrs. Mink, Vying With McGovern, Offers Oregon a Choice". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 26, 2021. Retrieved February 15, 2020.

- ^ Jonathan Martin (November 18, 2015). "Bobby Jindal Quits Republican Presidential Race". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 26, 2021. Retrieved February 15, 2020.

- ^ Purna Kamphampaty, Anna; Lang, Cady (November 7, 2020). "The Historic Barriers Kamala Harris Overcame to Reach the Vice-Presidency". Time. Archived from the original on March 26, 2021. Retrieved November 9, 2020.

- ^ "How Groups Voted in 1992 Roper Center for Public Opinion Research". ropercenter.cornell.edu. Retrieved November 4, 2022.

- ^ "Understanding The 2020 Electorate: AP VoteCast Survey". NPR. May 21, 2021. Retrieved November 4, 2022.

- ^ "Despite Trump-Modi Friendship, Survey Says Indian Americans Back Biden". NPR. Retrieved November 4, 2022.

- ^ Cai, Weiyi; Fessenden, Ford (December 21, 2020). "Immigrant Neighborhoods Shifted Red as the Country Chose Blue". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 4, 2022.

- ^ "Pew Study Finds Asian Americans Identify Themselves in Diverse Ways". May 8, 2023.

- ^ "CONNIE CHUNG". World Changers. Portland State University. Archived from the original on March 9, 2012. Retrieved February 21, 2012.

- ^ McNaughton, James C.; Edwards, Kristen E.; Price, Jay M. (November 1, 2002). ""Incontestable Proof Will Be Exacted": Historians, Asian Americans, and the Medal of Honor". The Public Historian. 24 (4): 11–33. doi:10.1525/tph.2002.24.4.11. ISSN 0272-3433.

- ^ Harper, Jon; Tritten, Travis J. (May 30, 2014). "VA Secretary Eric Shinseki resigns". Stars and Stripes. Archived from the original on June 16, 2018. Retrieved June 25, 2014.

- ^ Wenjen, Mia (March 6, 2021). "Asian Pacific American female Athletes Changing the Game". Mama Smiles. Retrieved May 19, 2021.

- ^ "About Asian-Pacific American Heritage Month". Library of Congress. Archived from the original on August 15, 2014. Retrieved August 18, 2014.

조지 부시(George Bush): "아시아/태평양 미국 유산의 달 제정을 위한 서명법에 관한 성명서", 1992년 10월 23일. Gerhard Peters와 John T의 온라인. 울리, 미국 대통령 프로젝트. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/index.php?pid=21645Archived 2008년 10월 5일 Wayback Machine에서 - ^ Russell, Stepehn (2010). "Introduction: Asian American Parenting and Parent-Adolescent Relationships". Asian American Parenting and Parent-Adolescent Relationships. New York, NY: Springer. pp. 1–15. doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-5728-3_1. ISBN 978-1-4419-5727-6.

Karen Kurasaki; Sumie Okazaki; Stanley Sue (December 6, 2012). Asian American Mental Health: Assessment Theories and Methods. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 260. ISBN 978-1-4615-0735-2. Archived from the original on June 1, 2020. Retrieved February 16, 2019. - ^ Amy Chua (December 6, 2011). Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother. A&C Black. ISBN 978-1-4088-2509-9. Archived from the original on March 26, 2021. Retrieved February 16, 2019.

Wang, Scarlett (Spring 2013). "The "Tiger Mom": Stereotypes of Chinese Parenting in the United States". Opus. Archived from the original on December 20, 2018. Retrieved February 15, 2019.

Chang, Bettina (June 18, 2014). "The Problem With A Culture of Excellence". Pacific Standard. The Social Justice Foundation. Archived from the original on February 16, 2019. Retrieved February 15, 2019. - ^ "International Medical Graduates by Country". American Medical Association. Archived from the original on July 5, 2008.

- ^ Sweis, L; Guay, A (2007). "Foreign-trained dentists licensed in the United States: Exploring their origins". J Am Dent Assoc. 138 (2): 219–224. doi:10.14219/jada.archive.2007.0140. PMID 17272378.

- ^ "Foreign Educated Nurses". ANA: American Nurses Association. Archived from the original on July 27, 2011. Retrieved August 31, 2009.

- ^ Koehn, NN; Fryer, GE. "Jr, Phillips RL, Miller JB, Green LA. (2007) The increase in international medical graduates in family practice residency programs". Journal of Family Medicine. 34 (6): 468–9.

- ^ Mick, SS; Lee, SY (1999). "Are there need-based geographical differences between international medical graduates and U.S. medical graduates in rural U.S. counties?". J Rural Health. 15 (1): 26–43. doi:10.1111/j.1748-0361.1999.tb00596.x. PMID 10437329.

- ^ Gerstmann, Evan (April 4, 2020). "Irony: Hate Crimes Surge Against Asian Americans While They Are On The Front Lines Fighting COVID-19". Forbes. Archived from the original on May 30, 2020. Retrieved May 24, 2020.

- ^ a b Regan A. R. Gurung (April 21, 2014). Multicultural Approaches to Health and Wellness in America [2 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. p. 156. ISBN 978-1-4408-0350-5. Archived from the original on May 31, 2020. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

- ^ Caroline Young; Cyndie Koopsen (2005). Spirituality, Health, and Healing. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-7637-4024-5. Archived from the original on May 29, 2020. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

Montenegro, Xenia P. (January 2015). The Health and Healthcare of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders Age 50+ (PDF) (Report). AARP. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 28, 2019. Retrieved February 27, 2019. - ^ Wang, Jun; Burke, Adam; Ysoh, Janice Y.; Le, Gem M.; Stewart, Susan; Gildengorin, Ginny; Wong, Ching; Chow, Elaine; Woo, Kent (2014). "Engaging Traditional Medicine Providers in Colorectal Cancer Screening Education in a Chinese American Community: A Pilot Study". Preventing Chronic Disease. 11: E217. doi:10.5888/pcd11.140341. PMC 4264464. PMID 25496557. Archived from the original on February 28, 2019. Retrieved February 27, 2019.

- ^ 파키스탄 미국의 교육적 성취는 2020년 2월 10일 아카이브에 보관되었습니다. 오늘날 미국 인구조사국. 2010년 10월 2일 검색.

- ^ "The American Community-Asians: 2004" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. February 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 26, 2007. Retrieved September 5, 2007. (그림 11, 페이지 15)

- ^ 파키스탄의 미국 이주: 경제적 관점 2013년 1월 22일 Wayback Machine에서 아카이브됨. 2010년 10월 1일 검색.