크리스마스

Christmas| 크리스마스 | |

|---|---|

| |

| 부름 | ë 없음, 네이티브, 콜레다, 엑스마스 |

| 관측 대상 | 기독교인들, 많은[1][2] 비기독교인들 |

| 유형 | 기독교, 문화, 국제 |

| 유의성 | 예수님의 탄생 기념 |

| 경축사 | 선물하기, 가족 및 기타 사교 모임, 상징적인 장식, 잔치 등. |

| 관측치 | 교회 예배 |

| 날짜. |

|

| 관련 | 크리스마스 이브, 성탄절 이브, 재림, 축일, 주님의 세례, 그리스도의 그리스도의 그리스도의 그리스도 성탄절, 율레, 성 스테판의 날, 복싱 데이 |

크리스마스는 예수 그리스도의 탄생을 기념하는 연례 축제로, 주로 12월 25일에[a] 전 세계 수십억 명의 사람들 사이에서 종교적이고 문화적인 기념 행사로 기념됩니다.[2][3][4] 기독교 전례의 해의 중심이 되는 축제인 이 축제는 (이전에 4개의 일요일이 시작되는) 강림절이나 그리스도 성탄절을 따르고, 역사적으로 서양에서 12일 동안 지속되고 12일 밤에 절정에 이르는 성탄절의 계절을 시작합니다.[5] 크리스마스는 많은 나라에서 공휴일이며,[6][7][8][9] 많은 비기독교인들에 의해 문화적으로뿐만 아니라 다수의 기독교인들에 의해 종교적으로 기념되며,[1][10] 그것을 중심으로 조직된 휴가철의 필수적인 부분을 형성합니다.

신약성서에 기록된 예수의 그리스도 성탄 이야기는 예수가 베들레헴에서 태어났다고 메시아적 예언에 따라 기록되어 있습니다.[11] 요셉과 마리아가 성에 도착했을 때, 여인숙에는 방이 없어서 곧 그리스도 아이가 태어난 마구간을 제공받았는데, 천사들은 이 소식을 양치기들에게 선포하고 그 말을 퍼뜨렸습니다.[12]

예수님의 탄생일에 대해서는 여러 가설이 있는데, 4세기 초에 교회는 날짜를 12월 25일로 정했습니다.[b][13][14][15] 이것은 로마 달력의 전통적인 동지 날짜에 해당합니다.[16] 춘분일이기도 한 3월 25일의 공표로부터 정확히 9개월이 지난 시점입니다.[17] 대부분의 기독교인들은 그레고리력으로 12월 25일을 기념하는데, 이는 전세계 국가에서 사용되는 시민 달력에 거의 보편적으로 채택되었습니다. 하지만, 동방 기독교 교회의 일부는 현재 그레고리력으로 1월 7일에 해당하는 더 오래된 율리우스력의 12월 25일에 크리스마스를 기념합니다. 기독교인들은 하나님이 예수님의 정확한 생신 날짜를 알기보다 인류의 죄를 속죄하기 위해 사람의 모습으로 세상에 나왔다고 믿는 것이 성탄절을 축하하는 일차적인 목적으로 여겨집니다.[18][19][20]

크리스마스와 관련된 여러 국가의 축하 관습은 기독교 이전, 기독교 및 세속적 주제와 기원이 혼합되어 있습니다.[21][22] 이 기념일의 인기 있는 현대 관습은 선물 주기, 재림 달력 또는 재림 화환 완성하기, 크리스마스 음악과 캐롤 부르기, 크리스마스 영화 보기, 예수탄생 연극 보기, 크리스마스 카드 교환, 교회 예배, 특별 식사, 그리고 크리스마스 트리, 크리스마스 조명을 포함한 다양한 크리스마스 장식의 전시, 그리스도 성탄화, 화관, 화환, 겨우살이, 그리고 홀리. 게다가, 산타클로스, 크리스마스 신부, 성 니콜라스, 그리고 크리스트킨트로 알려진, 밀접하게 관련되어 있고 종종 교환할 수 있는 몇몇 인물들은 크리스마스 시즌 동안 아이들에게 선물을 가져오는 것과 관련이 있고, 그들만의 전통과 전통을 가지고 있습니다.[23] 선물을 주는 것과 크리스마스 축제의 많은 다른 측면들이 경제 활동의 강화를 수반하기 때문에, 그 휴일은 중요한 행사가 되었고 소매업자들과 사업체들에게 중요한 판매 기간이 되었습니다. 지난 몇 세기 동안, 크리스마스는 세계의 많은 지역에서 꾸준히 증가하는 경제적 효과를 가져왔습니다.

어원

영어 단어 "Christmas"는 "Christ's Mass"의 줄임말입니다. 이 단어는 1038년에 Cr īstem æ세, 1131년에 Christes-messe라고 기록되어 있습니다. Cr ī스트(속칭 Cr ī스테스)는 그리스어 흐르 ī스토스(χ ριστός)에서 온 것으로, 히브리어 마시 î라 ḥ(מָשִׁיחַ)의 번역본인 "메시아"에서 온 것이며, 음 æ세는 성체 축일인 라틴어 미사에서 온 것입니다.

크리스텐마스라는 형태는 일부 기간 동안에도 사용되었지만, 현재는 고대와 변증법으로 여겨집니다.[28] 이 용어는 "기독교 미사"를 의미하는 중세 영어 크리스텐마스(Christenmasse)에서 유래되었습니다.[29] 크리스마스는 그리스어 흐르 ριστός스토스(χ χ)(그리스도)의 첫 글자인 ī( chi)에 기초하여 특히 인쇄된 크리스마스의 약자입니다. 이 약어는 미들 잉글리시 χ ρ̄ 매스(여기서 "ρ̄ χ"는 ριστός χ의 약어)에서 전례가 있습니다.

기타이름

"크리스마스" 외에도, 이 휴일은 역사를 통틀어 다양한 다른 영어 이름을 가지고 있습니다. 앵글로색슨인들은 이 축제를 "한겨울"이라고 불렀고, 더 드물게는 나티우이트 ð(Nātiuite diaguita, 아래 라틴어 나트 ī비타스에서 유래)라고 불렀습니다. "탄생"이라는 뜻의 "탄생"은 라틴어 나트 ī비타스에서 유래했습니다. 고대 영어에서 ē올라(율)는 12월과 1월에 해당하는 기간을 가리키며, 이 기간은 결국 기독교의 크리스마스와 동일시되었습니다. 노엘(Noel)은 14세기 후반에 영어로 유입되었으며, 고대 프랑스어 no ë 또는 na ë에서 유래했으며, 궁극적으로 "생일"을 의미하는 라틴어 nātális(di ē)에서 유래했습니다.

콜레다(Koleda)는 전통적인 슬라브어로 크리스마스와 크리스마스부터 에피파니, 또는 더 일반적으로 슬라브 크리스마스와 관련된 의식, 일부는 기독교 이전 시대까지 거슬러 올라갑니다.[37]

출생성

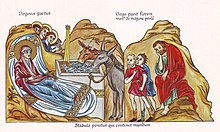

루크와 마태오의 복음서에는 예수가 베들레헴에서 성모 마리아에게 태어난 것으로 묘사되어 있습니다. 누가복음에서 요셉과 마리아는 인구조사를 위해 나사렛에서 베들레헴으로 여행을 왔고, 예수님은 그곳에서 태어나 관리인에 놓였습니다.[38] 천사들은 그를 모든 사람들의 구원자로 선포했고, 양치기들은 그를 사랑하기 위해 왔습니다. 마태오 복음서는 마태오가 유대인의 왕으로 태어난 예수에게 선물을 가져다 주기 위해 별을 따라 베들레헴으로 갔다고 덧붙였습니다. 헤롯왕은 베들레헴에서 태어난 지 2살도 안 된 소년들을 모두 학살하라고 명령했지만, 가족들은 이집트로 달아났다가 나중에 나사렛으로 돌아갔습니다.[39]

역사

2세기에 "초기 교회 기록"에 따르면, "기독교인들은 주님의 탄생을 기억하고 축하하고 있었다", "일반 신자들의 진정한 헌신으로부터 유기적으로 생겨난 준수", "정해진 날짜에 동의하지 않았다"고 합니다.[40] 그리스도의 탄생이 12월 25일에 표시된 가장 초기의 증거는 354년 연대기의 한 문장입니다.[41][42][43][44] 전례 역사가들은 일반적으로 이 부분이 서기 336년 로마에서 작성되었다는 것에 동의합니다.[42] 초기 기독교 작가인 이레나이우스와 테르툴리아누스가 제시한 축제 목록에는 크리스마스가 나타나지 않았지만,[24] 초기 교회의 신부 존 크리소스톰, 히포의 아우구스티누스, 제롬은 4세기 말에 크리스마스 날짜로 12월 25일을 증명했습니다.[40] 로마의 히폴리토스가 쓴 예언자 다니엘 평전(AD 204)의 한 구절은 12월 25일을 예수의 탄생일로 파악하고 있지만, 이 구절은 이후의 보간으로 여겨집니다.[42]

동양에서는 예수님의 탄생이 1월 6일 주현절과 관련하여 기념되었습니다.[45][46] 이 축일은 주로 그리스도의 탄생에 관한 것이 아니라 세례에 관한 것이었습니다.[47] 378년 아드리아노플 전투에서 친아리아 황제 발렌스가 사망한 이후 동방에서는 정교회 부활의 일환으로 크리스마스가 추진되었습니다. 이 축제는 379년 콘스탄티노폴리스에서, 4세기 말에 안티오키아에서,[46] 아마도 388년에, 그리고 그 다음 세기에 알렉산드리아에서 소개되었습니다.[48] 조지아의 이아드가리는 6세기까지 예루살렘에서 크리스마스를 기념했다는 것을 보여줍니다.[49]

날짜선택

이 섹션에는 특정 청중만 관심을 가질 수 있는 과도한 복잡한 세부 정보가 포함될 수 있습니다. (2023년 11월)(본 및 알아봅니다 |

3세기에는 예수의 탄생일이 큰 관심의 대상이었고, 초기 기독교 작가들은 다양한 날짜를 제시했습니다.[51] 서기 200년경, 알렉산드리아의 클레멘스는 다음과 같이 썼습니다.

"우리 주님이 태어나신 해뿐만 아니라, 그 날도 정한 사람들이 있는데, 그들은 그 날이 아우구스투스 28년과 [이집트 월] 25일에 일어났다고 말합니다. 파숑 [5월 20일] ... 게다가, 다른 사람들은 그가 [4월 20일 또는 21일][52]의 24일 또는 25일에 태어났다고 말합니다.

12월 25일을 선택하게 된 데는 다양한 요인이 작용했습니다. 그 날은 대부분의 기독교인들이 살았던 [42][16][53][54]로마 제국의 동지 날짜였습니다. 크리스마스는 제국에서 "국가가 후원하는 태양 숭배의 절정" 중에 나타났습니다.[55] 서기 274년부터 12월 25일에 로마의 축제인 Dies Natalis Solis Invicti ('무적의 태양' 솔 인빅투스의 탄생일)가 열렸습니다.[42] 초기 교회는 예수 그리스도를 태양과 연결시켰고, 그를 말라치가 예언한 '의로운 태양'(솔 주스티티아에)이라고 불렀습니다.[51][56] 초기 기독교 작가인 락탄티우스는 "동쪽은 하나님께 붙어 있다. 왜냐하면 그는 빛의 근원이며 세상의 빛의 빛이며 우리를 영원한 생명을 향해 솟아오르게 하기 때문이다."라고 썼습니다. 초기 기독교인들이 기도의 방향을 동쪽으로, 떠오르는 태양을 향해 나아가는 것으로 설정한 것도 이런 이유에서입니다.[40] 성 아우구스티누스의 4세기 후반 설교는 왜 동지가 그리스도의 탄생을 축하하기에 적합한 날이었는지 설명합니다.

그러므로 그는 우리 땅에서 가장 짧은 날에 태어났으며, 그 날부터 길이가 늘어나기 시작했습니다. 그러므로 낮게 굽혀서 우리를 일으켜 세우신 분은 빛이 증가하기 시작하는 가장 짧은 날을 택하셨습니다."[57]

앨버타 대학의 스티븐 히즈만스(Steven Hijmans)는 다음과 같이 썼습니다. "그것은 우주적 상징입니다. 이는 로마의 교회 지도부가 12월 25일을 그리스도의 생일로, 북지를 침례교 요한의 생일로 각각 추대하는 데 영감을 주었습니다."[58] 4세기 후반부터 기독교 논문인 De Solstitia et a equinoctia conceptis et nativitatis Domini nostri Iesu Christi et Iohannis Baptistae ('우리 주 예수 그리스도와 세례자 요한의 동지와 분추의 착상과 탄생에 대하여'),[59][60] 요한의 탄생일은 하지로, 예수의 탄생일은 동지로 날짜를 정합니다.[42][61]

12월 25일은 또한 예수님의 수태(음력)로 선택된 날짜이자 로마 달력의 춘분 날짜인 3월 25일로부터 9개월 후였습니다.[17]

신학 교수 수잔 롤은 "어떤 전례 역사학자도…"라고 말하지만,[40][62][63] 날짜의 선택에 대해서는 두 가지 주요한 이론이 제시되었습니다. 그것이 태양, 동지, 그리고 후기 로마 제국의 태양 숭배의 인기와 어떤 관련이 있다는 것을 부인하는 데까지 이르렀습니다."[64]

계산가설

"계산 가설"은 성탄절이 그리스도의 잉태로 선택된 날짜로부터 9개월 후로 계산되었다는 것을 암시합니다. 춘분의 로마 날짜인 3월 25일. 이 가설은 1889년 프랑스 작가 루이 뒤센에 의해 처음으로 제안되었습니다.[65][60][66] 수잔 롤(Susan Roll, 1995)은 계산 가설이 역사적으로 크리스마스의 기원에 대한 "소수 의견"이지만, "완전하게 실행 가능한 가설로서 대학원 문헌학 프로그램에서 가르침"을 받았다고 썼습니다.[67]

서기 221년, Sextus Julius Africanus는 전통적인 춘분인 3월 25일을 창조하는 날이자 그리스도의 수태일로 지정했습니다. 이것은 12월의 탄생을 암시하지만, 아프리칸스는 그리스도의 탄생일을 제시하지 않았고,[68] 그는 그 당시 영향력 있는 작가가 아니었습니다.[69]

일부 초기 기독교인들은 히브리어 달력에서 유월절 전날인 니산 14일에 해당하는 날짜에 예수의 십자가 처형을 표시했습니다. 이 축제는 4중주 (라틴어로 "14번째"를 뜻함)라고 불렸습니다. 일부 초기 기독교 작가들은 니산의 14번째를 3월 25일의 춘분과 동일시하고 그의 수태나 출생일을 그의 사망일과 동일하게 만들었습니다.[70][71] 뒤센은 예수가 태어나 같은 날에 죽은 것으로 생각되었기 때문에, "기호적인 수 체계는 분수의 불완전성을 허용하지 않기 때문에"라고 추측했습니다. 그러나 그는 이 이론이 어떤 초기 기독교 문헌에서도 지지되지 않는다는 것을 인정했습니다.[72]

아담 C. 캠벨 대학의 종교학 교수인 잉글리시는 예수의 탄생일인 12월 25일을 진실이라고 주장했습니다.[73] 누가복음 1장 26절에 나오는 성경은 침례교 요한의 어머니 엘리자베스가 임신 6개월째에 있을 때라고 마리아에게 보낸 계시를 기록하고 있습니다.[73][74] 영어는 누가복음 1장 5절에서 23절에 나오는 대로 성전 안에서 제가랴의 사역이 예수가 태어나기 바로 전 해에 욤 키푸르에서 이루어졌다고 가정하고, 그 후 누가복음의 이야기와 세례자 요한의 탄생을 추적하여 예수가 12월 25일에 태어났다고 결론내립니다.[73] 축일에 대한 가장 초기의 증거는 6세기의 것입니다.[75][76]

수잔 롤(Susan Roll)은 "3세기와 4세기의 평범한 기독교인들이 기호 숫자를 가진 계산에 많은 관심을 가지고 있었는지"에 대해 의문을 제기합니다.[77] 마찬가지로, 제라드 루호스트(Gerard Rouwhorst)는 축제가 "예식가들과 신학자들의 계산에 근거하여" 출현했을 가능성은 낮다고 믿으며, "축제가 공동체에서 뿌리내리기 위해서는 정교한 계산보다 더 많이 필요하다"고 주장합니다.[78]

종교의 역사

위의 동지설과 관련하여, "종교의 역사" 가설에 따르면, 교회는 같은 날짜에 열리는 로마의 동지 축제인 나탈리스 솔리스 인빅티(Natalis Solis Invicti, 정복되지 않은 태양의 생일)를 적합하게 하기 위해 12월 25일을 그리스도의 생일(dies Natalis Christi)[79]로 선택했습니다.[63][80] 그것은 서기 274년에 아우렐리아누스 황제에 의해 컬트가 부활한 태양신 솔 인빅투스를 기렸습니다. 로마에서 매년 열리는 이 축제는 30번의 전차 경주로 기념되었습니다.[80] 고대 역사학 교수인 게리 포사이트는 "이 기념행사는 파티, 연회, 선물 교환으로 특징지어지는 공화정 시대 이후 로마에서 가장 즐거운 휴가 시즌인 새터날리아 (12월 17일-23일)의 7일 기간에 반가운 추가를 형성했을 것입니다."[80]라고 말합니다. 기원후 362년, 황제 줄리안은 헬리오스 왕에게 보내는 찬송가에서 아곤 솔리스는 12월 말 새터날리아에서 열리는 태양의 축제라고 썼습니다.[81][82]

요한 크리소스톰이 기원후 4세기 초로 추정되는 기독교의 한 논문은 그리스도의 탄생을 솔의 생일과 연관시켰습니다.

"우리 주님도 12월에 태어나십니다. 일월[12월 25일]전의 여덟번째. 그러나 그들은 그것을 '정복되지 않은 사람들의 생일'이라고 부릅니다. 우리 주님처럼 정복되지 않은 사람이 과연 누구입니까? 또는 태양의 생일이라고 하면 [우리는 그가 정의의 태양이라고 말할 수 있습니다.][24]

이 이론은 12세기 시리아 주교 야콥 바르 살리비의 필사본에 추가된 불확실한 날짜의 주석에 언급되어 있습니다. 필경사는 다음과 같이 썼습니다.

"이교도들은 12월 25일에 태양의 생일을 기념하는 관습이 있었고, 그 때 그들은 축제의 상징으로 불을 피웠습니다. 이런 엄숙함과 경축에 기독교인들도 참여했습니다. 이에 따라 교회의 의사들은 기독교인들이 이 축제에 대한 성향이 있다는 것을 인지하고 상담을 받아 그날 진정한 그리스도인이 엄숙해야 한다고 결의했습니다."[83]

17세기에 우연히 12월 25일에 태어난 아이작 뉴턴은 크리스마스 날짜를 동지와 일치하도록 선택할 것을 제안했습니다.[84] 1743년, 독일 학자 Paul Ernst Jablonski는 그 날짜가 Natalis Solis Invicti와 일치하도록 선택되었다고 주장했습니다.[85] 이 가설은 1889년 동료 독일 학자 헤르만 유세너에[65][86] 의해 처음으로 개발되었고 그 후 많은 학자들에 의해 채택되었습니다.[65]

앨버타 대학의 스티븐 히즈만스는 이교도 축제를 위해 이 날짜가 선택되었다는 생각이 "광범위하게 받아들여졌다"고 말합니다. 그는 교회가 동지이기 때문에 날짜를 선택했다는 것에 동의하지만, "그들은 이교도들이 이 날을 솔 인빅투스의 '생일'이라고 부르는 것을 알고 있었지만, 이것은 그들과 관련이 없었고, 그들이 크리스마스 날짜를 선택하는 데 어떤 역할도 하지 않았습니다"[58]라고 주장합니다. 히즈만스는 이렇게 말합니다. "12월 25일 또는 그 무렵의 동지는 로마 제국 달력에 잘 자리 잡았지만, 그 날의 솔의 종교적인 축하가 크리스마스의 축하를 원했다는 증거는 없습니다."[87] 토마스 탈리(Thomas Talley)는 아우렐리아누스가 기독교인들에게 이미 중요하다고 주장하는 날짜에 이교도적인 의미를 부여하기 위해 부분적으로 나탈리스 솔리스 인빅티(Dies Natalis Solis Invicti)를 설립했다고 주장합니다.[62] 옥스퍼드 기독교 사상의 동반자(Oxford Companion to Christian Thought)는 "계산 가설은 12월 25일을 아우렐리아누스의 칙령 이전에 기독교 축제로 잠재적으로 설정한다"[88]고 언급합니다. C에 의하면. 필리핀 E. 트리니티 칼리지 더블린의 노샤프트 교수는 종교의 역사가 "오늘날 12월 25일을 그리스도의 생일로 선택한 기본적인 설명으로 사용되고 있지만,[89] 이 이론을 지지하는 사람들은 거의 없습니다."라고 말했습니다.

동시에 진행되는 축하 행사와의 관계

크리스마스와 관련된 많은 대중적인 관습들은 예수의 탄생 기념과는 별개로 발전했습니다. 어떤 사람들은 어떤 요소들이 기독교화되어 있고 나중에 기독교로 개종한 이교도 사람들에 의해 기념된 기독교 이전의 축제에 기원을 두고 있다고 주장합니다. 다른 학자들은 이러한 주장을 거부하고 크리스마스 관습이 주로 기독교적 맥락에서 발전했다고 단언합니다.[90][22] 크리스마스의 지배적인 분위기는 또한 명절이 시작된 이래로, 때때로 요란하고, 술에 취한,[91] 중세의 카니발 같은 상태에서 19세기의 변화 속에서 도입된 가정 중심적이고 어린이 중심적인 주제에 이르기까지 지속적으로 발전해 왔습니다.[92][93] 청교도와 여호와의 증인(일반적으로 생일을 축하하지 않는 사람)과 같은 특정 그룹 내에서 크리스마스를 축하하는 것이 너무 성경적이지 않다는 우려 때문에 한 번 이상 금지되었습니다.[94][95][96]

기독교 세기 이전과 초기에, 겨울 축제는 많은 유럽의 이교도 문화에서 1년 중 가장 인기가 많았습니다. 그 이유로는 겨울 동안 농업 작업이 덜 필요하다는 사실과 봄이 다가오면서 더 좋은 날씨가 올 것이라는 기대감이 있었습니다.[97] 겨우살이나 담쟁이덩굴과 같은 켈트 겨울 약초, 겨우살이 아래에서 키스하는 관습은 영어권 국가의 현대 크리스마스 기념식에서 흔히 볼 수 있습니다.[98]

앵글로색슨족과 노르드족을 포함한 기독교 이전의 게르만 민족은 12월 말에서 1월 초에 열린 율(Yule)이라는 겨울 축제를 기념하여 오늘날 크리스마스의 대명사로 사용되는 현대 영어 율을 산출했습니다.[99] 게르만어를 사용하는 지역에서는 율레로그, 율레 멧돼지, 율레 염소 등 현대 크리스마스 민속 관습과 도상의 수많은 요소가 율레에서 유래했을 수 있습니다.[100][99] 종종 하늘을 통해 유령과 같은 행렬을 이끌며(야생 사냥), 긴 수염을 가진 신 오딘은 고대 노르드어 문헌에서 "율레 원"과 "율레 아버지"로 언급되는 반면, 다른 신들은 "율레 존재"로 언급됩니다.[101] 한편, 16세기 이전의 크리스마스 일지에 대한 신뢰할 만한 현존하는 언급이 없기 때문에, 크리스마스 블록을 태우는 것은 이교도의 관습과는 무관한 기독교인들에 의한 초기 현대적인 발명이었을 수도 있습니다.[102]

또한 동유럽에서는 기독교 이전의 전통이 그곳의 크리스마스 기념식에 포함되었는데, 그 예로 크리스마스 캐롤과 비슷한 점을 공유하는 [103]콜레다가 있습니다.

고전 이후의 역사

크리스마스는 4세기의 아리아 논쟁에 한 몫을 했습니다. 이 논쟁이 진행된 후, 이 휴일의 중요성은 몇 세기 동안 감소했습니다.

중세 초기에는 서양 기독교에서 마법사의 방문에 초점을 맞춘 주현절(Epiphany)에 의해 크리스마스가 가려졌습니다. 그러나 중세 달력은 크리스마스와 관련된 휴일이 지배적이었습니다. 성탄절 40일 전은 성(聖) 40일이 되었습니다. 마르틴" (11월 11일 성 축일에 시작). 투어의 마틴), 현재는 어드벤스트로 알려져 있습니다.[91] 이탈리아에서는, 이전의 토성 전통이 강림에 붙어있었습니다.[91] 12세기경, 이러한 전통은 다시 12일의 크리스마스 (12월 25일 - 1월 5일)로 옮겨졌습니다. 이 시기는 전례력에서 크리스마스 (Christmastide) 또는 12성일 (12 Holy Days)로 나타납니다.[91]

567년 여행평의회는 "크리스마스부터 주현절까지의 12일을 성스럽고 축제적인 계절로 선포하고, 축제에 대비하여 강림절 금식의 의무를 확립했습니다."[5][104] 이것은 "로마 제국이 태양 율리우스력과 동쪽 지방의 음력을 조정하려고 했기 때문에 행정적인 문제"를 해결하기 위해 행해졌습니다.[105][106][107]

800년 크리스마스에 샤를마뉴가 황제로 즉위한 이후 크리스마스의 중요성은 점차 높아졌습니다.[108] 순교자 에드먼드 왕은 855년 크리스마스에 즉위했고 영국의 윌리엄 1세는 1066년 크리스마스에 즉위했습니다.[109]

중세 시대에 이르러, 이 휴일은 매우 중요해져서 연대기 편찬가들은 다양한 거물들이 크리스마스를 어디에서 기념하는지를 일상적으로 주목했습니다. 영국의 리처드 2세는 1377년에 28마리의 소와 300마리의 양을 먹는 크리스마스 축제를 열었습니다.[91] 율레 멧돼지는 중세 크리스마스 축제의 흔한 특징이었습니다. 캐롤도 인기를 끌었고, 원래는 노래를 부르는 무용수들에 의해 공연되었습니다. 그 그룹은 리드 싱어와 코러스를 제공하는 댄서들의 링으로 구성되었습니다. 당시의 여러 작가들은 캐롤을 음탕하다고 비난했는데, 이는 사투날리아와 율레의 제멋대로인 전통이 이러한 형태로 계속되었을 수 있다는 것을 보여줍니다.[91] 음주, 난잡함, 도박과 같은 "잘못된 규칙" 또한 축제의 중요한 측면이었습니다. 영국에서는 새해 첫날에 선물을 주고 받았고, 특별한 크리스마스 에일이 있었습니다.[91]

중세의 크리스마스는 담쟁이덩굴, 홀리 그리고 다른 상록수들을 포함하는 공공 축제였습니다.[110] 중세 시대의 크리스마스 선물은 대개 세입자와 집주인 등 법적 관계가 있는 사람들 사이에 있었습니다.[110] 매년 먹는 것, 춤추는 것, 노래하는 것, 스포츠하는 것, 그리고 카드놀이에 탐닉하는 것이 영국에서 증가했고, 17세기까지 크리스마스 시즌은 호화로운 저녁 식사, 정교한 가면, 그리고 미인대회를 특징으로 했습니다. 1607년 제임스 1세는 크리스마스 밤에 연극을 공연하고 궁정은 게임에 빠져들 것을 주장했습니다.[111] 많은 개신교인들이 선물을 가져오는 사람을 Christ Child 또는 Christkindl로 바꾼 것은 16-17세기 유럽의 종교 개혁 중이었고, 선물을 주는 날짜는 12월 6일에서 크리스마스 이브로 바뀌었습니다.[112]

근대사

17세기와 18세기

개신교 개혁 이후, 성공회와 루터 교회를 포함한 많은 새로운 교파들이 계속해서 크리스마스를 기념했습니다.[113] 1629년 영국 성공회 시인 존 밀턴은 그리스도 성탄절 동안 많은 사람들이 읽혀온 시인 그리스도의 탄생의 아침을 썼습니다.[114][115] 캘리포니아 주립 대학의 교수인 도널드 하인즈는 마틴 루터가 "독일이 북미에서 많이 모방되는 독특한 크리스마스 문화를 생산하는 시기를 시작했다"고 말했습니다.[116] 네덜란드 개혁교회의 회중에서 크리스마스는 주요 복음성가의 축제 중 하나로 기념되었습니다.[117]

그러나 17세기 영국에서 청교도와 같은 일부 단체들은 크리스마스를 가톨릭의 발명품이자 "교황의 쓰레기" 또는 "야수의 쓰레기"로 간주하여 크리스마스를 강력하게 비난했습니다.[95] 대조적으로, 설립된 성공회는 "축제, 참회의 계절, 성인의 날들에 대한 더 정교한 준수를 요구합니다. 달력 개혁은 성공회당과 청교도당 사이의 긴장의 주요 지점이 되었습니다."[118] 가톨릭 교회도 이에 화답하여, 축제를 더욱 종교적인 형태로 홍보했습니다. 영국의 찰스 1세는 그의 귀족들과 신사들에게 그들의 옛날식 크리스마스 관대함을 유지하기 위해 한겨울에 그들의 토지 소유지로 돌아가라고 지시했습니다.[111] 영국 내전 동안 찰스 1세에 대한 의회의 승리 이후, 영국의 청교도 통치자들은 1647년 크리스마스를 금지했습니다.[95][119]

몇몇 도시에서 친크리스마스 폭동이 일어났고 캔터베리는 몇 주 동안 홀리로 문을 장식하고 왕당파 구호를 외친 폭도들에 의해 통제를 당하면서 시위가 이어졌습니다.[95] 청교도들이 일요일에 금지한 스포츠 중 축구는 반란군으로 사용되기도 했습니다: 1647년 12월 청교도들이 영국에서 크리스마스를 불법으로 규정했을 때 군중들은 축제의 잘못된 통치의 상징으로 축구를 꺼내들었습니다.[120] 이 책은 '크리스마스의 정당성'(London, 1652)이라는 책은 청교도들을 반대하는 주장을 펼쳤고, 고대 영국의 크리스마스 전통, 저녁식사, 불 위에 구운 사과, 카드놀이, "쟁기 소년"과 "하녀 하인"과 춤, 오래된 아버지 크리스마스와 캐롤 노래에 대해 기록하고 있습니다.[121] 금지 기간 동안, 그리스도의 탄생을 알리는 반비밀 종교 예배가 계속 열렸고, 사람들은 비밀리에 캐롤을 불렀습니다.[122]

1660년 찰스 2세 왕의 유신으로 청교도의 입법이 무효로 선언되면서 영국에서 법정 공휴일로 복원되었고, 크리스마스는 다시 자유롭게 영국에서 기념되고 있습니다.[122] 많은 칼뱅주의 성직자들은 크리스마스 축하행사를 좋아하지 않았습니다. 이와 같이 스코틀랜드에서는 스코틀랜드 장로교회가 성탄절을 지키는 것을 반대했고, 제임스 6세가 1618년 성탄절 경축을 지휘했지만, 교회 참석은 부족했습니다.[123] 스코틀랜드 의회는 1640년 공식적으로 교회가 "모든 미신적인 날들의 관찰을 제거했다"고 주장하며 성탄절 준수를 폐지했습니다.[124] 잉글랜드, 웨일즈, 아일랜드의 크리스마스는 태곳적부터 관습적인 휴일이었던 보통법의 휴일인 반면, 스코틀랜드에서는 1871년이 되어서야 은행 휴일로 지정되었습니다.[125] 찰스 2세의 왕정복고 이후, 불쌍한 로빈의 연감은 다음과 같은 구절을 담고 있습니다: "이제 찰스가 돌아오신 것에 대한 신께 감사드립니다. / 그의 부재가 오래된 크리스마스를 애절하게 만들었습니다. / 그 때 우리는 그것이 크리스마스였는지 아닌지 거의 알지 못했습니다."[126] 18세기 후반부터 제임스 우드포드의 일기는 크리스마스의 준수와 여러 해에 걸친 그 계절과 관련된 기념행사들을 자세히 묘사하고 있습니다.[127]

영국에서와 마찬가지로 식민지 미국의 청교도들은 크리스마스를 지키는 것을 완강히 반대했습니다.[96] 뉴잉글랜드의 순례자들은 지적으로 그들의 첫 12월 25일을 신세계에서 정상적으로 일하며 보냈습니다.[96] 면마더와 같은 청교도들은 경전에서 성탄절의 준수에 대해 언급하지 않았기 때문에, 그리고 그날의 성탄절 기념행사들이 종종 떠들썩한 행동을 수반했기 때문에 모두 성탄절을 비난했습니다.[128][129] 뉴잉글랜드의 많은 청교도가 아닌 사람들은 영국의 노동자 계급이 즐겼던 휴일을 잃게 된 것을 개탄했습니다.[130] 1659년 보스턴에서 크리스마스의 준수는 불법이 되었습니다.[96] 크리스마스 준수 금지는 1681년 에드먼드 안드로스 영국 총독에 의해 취소되었지만, 19세기 중반이 되어서야 보스턴 지역에서 크리스마스를 기념하는 것이 유행이 되었습니다.[131]

동시에 버지니아와 뉴욕의 기독교 주민들은 이 휴일을 자유롭게 지켰습니다. 펜실베이니아의 베들레헴, 나사렛, 리티츠의 모라비아 정착민과 노스캐롤라이나의 와코비아 정착민을 중심으로 한 펜실베이니아 네덜란드 정착민들은 크리스마스를 열렬히 축하하는 사람들이었습니다. 베들레헴의 모라비아 사람들은 첫 번째 그리스도 성탄화 뿐만 아니라 첫 번째 그리스도 성탄화를 가지고 있었습니다.[132] 크리스마스는 영국의 관습으로 여겨졌던 미국혁명 이후 미국에서 인기가 없었습니다.[133] 1776년 12월 26일 트렌턴 전투에서 조지 워싱턴은 크리스마스 다음 날 헤센(독일) 용병을 공격했는데, 이때 크리스마스는 미국보다 독일에서 훨씬 인기가 많았습니다.

혁명 프랑스 시대에 무신론적인 이성교도가 집권하면서 기독교의 크리스마스 종교 예배가 금지되었고, 반고전적인 정부 정책에 따라 세 개의 왕 케이크는 "평등 케이크"로 이름이 바뀌었습니다.[134][135]

19세기

19세기 초, 크리스마스 축제와 예배는 가족,[136] 아이들, 친절함을 강조하는 워싱턴 어빙, 찰스 디킨스, 그리고 다른 작가들과 함께 기독교에서 크리스마스의 중심성과 가난한 사람들에 대한 자선을 강조하는 영국 교회의 옥스포드 운동의 발흥과 함께 널리 퍼졌습니다. 선물을 주는 것, 그리고 산타클로스(어빙을 위한),[136] 또는 크리스마스 신부(디킨스를 위한).[137]

19세기 초, 작가들은 튜더 크리스마스를 진심 어린 축하의 시간으로 상상했습니다. 1843년, 찰스 디킨스는 크리스마스와 계절적인 즐거움의 "정신"을 되살리는 데 도움을 준 소설 "크리스마스 캐롤"을 썼습니다.[92][93] 그것의 즉각적인 인기는 크리스마스를 가족, 호의, 그리고 연민을 강조하는 휴일로 묘사하는 데 큰 역할을 했습니다.[136]

디킨스는 크리스마스를 "예배와 잔치, 사회적 화해의 맥락 안에서" 연결시켜 가족 중심의 관대한 축제로 구성하고자 했습니다.[138] 디킨스는 "캐롤 철학"이라고 불리는 이 기념일에 대한 그의 인도주의적인 비전을 겹치면서,[139] 가족 모임, 계절 음식과 음료, 춤, 게임, 그리고 축제 분위기의 관대함과 같은 서양 문화에서 오늘날 기념되는 크리스마스의 많은 측면에 영향을 미쳤습니다.[140] 이 이야기의 중요한 문구인 "메리 크리스마스"는 이 이야기의 등장 이후 대중화되었습니다.[141] 이는 옥스퍼드 운동의 등장과 영국-가톨릭의 성장과 맞물려 전통적인 의식과 종교적인 의식의 부활을 이끌었습니다.[142]

스크루지라는 용어는 "Bah!"와 함께 구두쇠의 동의어가 되었습니다. 축제 분위기를 무시하는 험버그![143] 1843년, 최초의 상업적인 크리스마스 카드가 Henry Cole경에 의해 제작되었습니다.[144] 크리스마스 캐롤의 부활은 윌리엄 샌디스(William Sandys)의 크리스마스 캐롤 고대와 현대(The First Noel), "I Saw Three Ships", "Hark the Herald Angels Sing", "God Rest Ye Merry, Gentlemen"의 인쇄물에 처음 등장하여 디킨스의 크리스마스 캐롤에서 대중화되었습니다.

영국에서, 크리스마스 트리는 독일에서 태어난 샬롯 여왕에 의해 19세기 초에 소개되었습니다. 1832년에 미래의 빅토리아 여왕은 크리스마스 트리가 있는 것에 대한 그녀의 기쁨에 대해 썼습니다, 조명, 장식품, 선물들이 그 트리 주위에 걸려 있었습니다.[145] 그녀가 독일인 사촌 알버트 왕자와 결혼한 후, 1841년까지 이 관습은 영국 전역에 널리 퍼졌습니다.[146]

윈저 성에서 크리스마스 트리를 들고 있는 영국 왕실의 한 이미지가 1848년 일러스트레이티드 런던 뉴스에 실리면서 센세이션을 일으켰습니다. 이 이미지의 수정된 버전은 1850년 필라델피아의 고디의 레이디 북에 출판되었습니다.[147][148] 1870년대까지, 크리스마스 트리를 세우는 것은 미국에서 흔한 일이 되었습니다.[147]

미국에서 크리스마스에 대한 관심은 1820년대에 워싱턴 어빙에 의해 그의 제프리 크레용의 스케치북, 젠트, 그리고 "올드 크리스마스"에 등장하는 몇 편의 단편 소설에 의해 되살아났습니다. 어빙의 이야기들은 주로 버려졌던 영국 버밍엄의 애스턴 홀에 머물면서 경험했던 따뜻한 마음의 영국 크리스마스 축제들을 [149]묘사했고, 그는 그의 이야기들을 위한 형식으로 그의 저널에 필사했던 오래된 영국 크리스마스 전통의 "크리스마스의 보증" (1652)이라는 트랙을 사용했습니다.[111]

1822년, 클레멘트 클라크 무어는 성에서 온 방문이라는 시를 썼습니다. 니콜라스(일반적으로 첫 번째 대사로 알려져 있음: 크리스마스 전날 밤).[150] 이 시는 선물을 주고받는 전통을 대중화하는 데 도움을 주었고, 계절별 크리스마스 쇼핑은 경제적 중요성을 띠기 시작했습니다.[151] 이것은 또한 그 휴일의 정신적인 중요성과 일부 사람들이 그 휴일을 부패시킨다고 생각하는 그것과 관련된 상업주의 사이의 문화적인 갈등을 시작했습니다. 1850년 그녀의 책 뉴잉글랜드에서의 첫 번째 크리스마스에서 해리엇 비처 스토는 크리스마스의 진정한 의미를 쇼핑 몰이로 잃었다고 불평하는 인물을 포함합니다.[152]

미국의 일부 지역에서는 크리스마스를 기념하는 것이 아직 관습적이지 않았지만, 헨리 워즈워스 롱펠로우는 1856년에 "여기 뉴잉글랜드의 크리스마스에 관한 과도기 상태"를 감지했습니다. "옛날의 청교도적인 느낌 때문에 그것이 즐겁고 풍요로운 휴일이 되는 것을 막을 수 있습니다. 매년 그것을 더욱더 그렇게 만들지만 말입니다."[153] 1861년 펜실베이니아주 레딩에서 한 신문은 "지금까지 변함없이 크리스마스를 무시해온 우리 장로교 친구들도 구세주 탄생 기념일을 축하하기 위해 교회 문을 열고 힘을 합쳐 모였다"고 전했습니다.[153]

일리노이주 록퍼드 제1회 회중교회는 "청교도의 주식을 가지고 있기는 하지만" '위대한 크리스마스 주빌리를 준비하고 있다'고 1864년 통신원이 보도했습니다.[153] 1860년까지, 뉴잉글랜드의 몇몇을 포함한 14개의 주가 크리스마스를 법정 공휴일로 채택했습니다.[154] 1875년에 루이프랑은 미국인들에게 크리스마스 카드를 소개했습니다. 그는 "미국 크리스마스 카드의 아버지"라고 불려왔습니다.[155] 1870년 6월 28일, 크리스마스는 공식적으로 미국 연방 공휴일로 선언되었습니다.[156]

20세기

1914년 제1차 세계 대전과 특히 (단독적이지는 않지만),[157] 대립하는 군대들 사이에 크리스마스를 위한 일련의 비공식적인 관습들이 있었습니다. 싸움꾼들이 자발적으로 조직한 이 관습은 총을 쏘지 않겠다는 약속(당일 전쟁의 압박을 완화하기 위해 멀리서 외치는 것)에서부터 우호적인 사교, 선물 주기, 심지어 적들 간의 스포츠까지 다양했습니다.[158] 이 사건들은 대중적인 기억에서 잘 알려지고 반신화된 부분이 되었습니다.[159] 그들은 가장 어두운 상황에서도 공동의 인간성의 상징으로 묘사되었고 아이들에게 크리스마스의 이상을 보여주기 위해 사용되었습니다.[160]

1950년대까지 영국에서는 많은 크리스마스 관습들이 상류층과 중산층으로 제한되었습니다. 대부분의 사람들은 아직 크리스마스 트리를 포함하여 나중에 인기를 얻게 된 많은 크리스마스 의식을 채택하지 않았습니다. 크리스마스 저녁 식사는 일반적으로 나중에 흔히 볼 수 있는 칠면조가 아닌 쇠고기나 거위를 포함합니다. 아이들은 정교한 선물보다는 과일과 과자를 스타킹에 넣을 것입니다. 모든 트리밍과 함께 한 가족의 크리스마스를 완전히 축하하는 것은 1950년대부터 번영과 함께 널리 퍼지게 되었습니다.[161] 1912년까지 전국적인 신문들이 크리스마스에 발행되었습니다. 우편물은 1961년까지 여전히 크리스마스에 배달되었습니다. 리그 축구 경기는 스코틀랜드에서 1970년대까지 계속되었고, 잉글랜드에서는 1950년대 말에 중단되었습니다.[162][163]

소비에트 연방의 국가 무신론 하에서 1917년 건국 이후, 다른 기독교 휴일들과 함께, 크리스마스 기념식들은 공공장소에서 금지되었습니다.[164] 1920년대, 30년대, 40년대에 무장 무신론자 연맹은 부활절을 포함한 다른 기독교 휴일뿐만 아니라 크리스마스 트리와 같은 크리스마스 전통에 반대하는 운동을 학생들에게 장려했습니다. 연맹은 대체적으로 매달 31일을 반종교 휴일로 정했습니다.[165] 이러한 박해가 절정에 달했던 1929년, 크리스마스 날에 모스크바의 어린이들은 휴일에 대한 항의의 표시로 십자가에 침을 뱉도록 권장되었습니다.[166] 대신, 크리스마스 트리와 선물 주기와 같은 이 명절의 중요성과 모든 쓰레기 처리는 새해로 옮겨졌습니다.[167] 1991년 소련이 해체된 뒤에야 박해가 종식됐고 러시아에서는 70년 만에 다시 정교회 성탄절이 공휴일이 됐습니다.[168]

유럽사 교수 조셉 페리는 나치 독일에서도 마찬가지로 "나치 사상가들은 조직화된 종교를 전체주의 국가의 적으로 간주했기 때문에 선전가들은 이 명절의 기독교적 측면을 강조하거나 아예 없애려고 했다"며 "선전가들은 끊임없이 나치화된 수많은 크리스마스 노래를 홍보했다"고 썼습니다. 기독교 주제를 정권의 인종 이념으로 대체한 것입니다."[169]

20세기에 들어 전통적인 기독교 문화권 밖에서도 전 세계적으로 크리스마스 행사가 열리기 시작하면서, 일부 이슬람교도가 많은 국가들은 그것이 이슬람교를 훼손한다고 주장하며 크리스마스 행사를 금지했습니다.[170]

준수 및 전통

밝은 갈색 – 크리스마스를 공휴일로 인정하지 않는 나라들, 하지만 그 공휴일은 준수됩니다.

크리스마스는 대부분 비기독교인인 많은 사람들을 포함한 전 세계 국가에서 주요 축제이자 공휴일로 기념됩니다. 일부 비기독교 지역에서는 과거 식민지 지배 기간에 홍콩과 같은 기념일이 도입되었고, 다른 지역에서는 기독교 소수 민족이나 외국 문화의 영향으로 사람들이 기념일을 준수하게 되었습니다. 기독교인의 수가 적음에도 불구하고 크리스마스가 인기 있는 일본과 같은 나라들은 선물 주기, 장식, 그리고 크리스마스 트리와 같은 크리스마스의 문화적인 측면을 많이 채택했습니다. 비슷한 예는 이슬람교도가 다수이고 소수의 기독교인이 있는 튀르키예에서 크리스마스 트리와 장식이 축제 기간 동안 공공 거리에 줄지어 있는 경향이 있습니다.

기독교 전통이 강한 나라들 사이에서 지역 문화와 지역 문화를 접목한 다양한 크리스마스 기념 행사들이 발달했습니다.

교회참석

성탄절은 루터 교회의 축제, 로마 가톨릭 교회의 엄숙함, 성공회 연합의 주요 축제입니다. 다른 기독교 교파들은 그들의 축제일의 순위를 매기지 않지만, 부활절, 승천일, 오순절과 같은 다른 기독교 축제들과 마찬가지로 크리스마스 이브/크리스마스 날에 중요성을 둡니다.[173] 이처럼 기독교인들에게 크리스마스 이브나 크리스마스 데이 교회 예배에 참석하는 것은 크리스마스 시즌을 인식하는 데 중요한 역할을 합니다. 크리스마스는 부활절과 함께 매년 교회 출석률이 가장 높은 기간입니다. 라이프웨이 크리스천 리소스(LifeWay Christian Resources)의 2010년 조사에 따르면 미국인 10명 중 6명이 이 기간 동안 교회 예배에 참석하는 것으로 나타났습니다.[174] 영국에서, 영국 교회는 2015년 크리스마스 예배에 250만 명이 참석한 것으로 추정된다고 보고했습니다.[175]

장식들

그리스도 성탄화는 10세기 로마에서부터 알려져 있습니다. 그것들은 1223년부터 아시시의 성 프란치스코에 의해 대중화되었고, 빠르게 유럽 전역으로 퍼졌습니다.[176] 지역 전통과 이용 가능한 자원에 따라 기독교 세계에서 다양한 종류의 장식이 발전했고, 아기 침대의 단순한 표현에서 훨씬 더 정교한 세트까지 다양할 수 있습니다. 유명한 관리자 장면 전통에는 폴란드의 다채로운 크라쿠프 솝카가 포함되어 있는데,[177] 이는 크라쿠프의 역사적인 건물을 배경으로 모방한 것입니다. 정교한 이탈리아의 프레세피 (네팔 [it], 제노바 [it], 볼로네세 [it]) 또는 산톤이라고 불리는 손으로 그린 테라코타 피규어를 사용한 프랑스 남부의 프로방스알 크레스.[178][179][180][181][182] 세계의 특정 지역, 특히 시칠리아에서는 성 프란치스코의 전통을 따르는 살아있는 그리스도 성탄화가 정적인 크레스 대신 인기 있는 대안입니다.[183][184][185] 상업적으로 생산된 최초의 장식은 1860년대 독일에서 어린이들이 만든 종이 체인에서 영감을 받아 등장했습니다.[186] 그리스도 성탄화의 대표성이 매우 인기 있는 나라에서는, 사람들이 경쟁하고 가장 독창적이거나 현실적인 것들을 만들도록 권장됩니다. 일부 가정에서는 이를 표현하는 데 사용되는 조각을 귀중한 가족 가보로 간주합니다.[187]

크리스마스 장식의 전통적인 색상은 빨간색, 녹색, 금색입니다.[188][189] 빨간색은 십자가에 못 박혀 흘린 예수의 피를, 초록색은 영원한 생명을, 특히 겨울에도 잎을 잃지 않는 상록수를, 금색은 금자탑의 세 가지 선물 중 하나로 크리스마스와 연관된 첫 번째 색상으로 왕족을 상징합니다.[190]

크리스마스 트리는 16세기에 독일 루터교 신자들에 의해 처음 사용되었는데, 1539년에 개신교 개혁가 마르틴 부케르의 지도 아래 스트라스부르크 대성당에 크리스마스 트리가 놓여졌다는 기록이 있습니다.[191][192] 미국에서, 이 "독일 루터교 사람들은 장식된 크리스마스 트리를 가지고 왔습니다; 모라비아 사람들은 그 트리들에 불을 붙인 촛불을 켭니다."[193][194] 크리스마스 트리를 장식할 때, 많은 사람들이 베들레헴의 별을 상징하는 별을 트리의 꼭대기에 놓는데, 이것은 1897년 학교 저널에 의해 기록된 사실입니다.[195][196] 옥스포드 대학의 데이비드 알버트 존스 교수는 19세기에 사람들이 예수 그리스도 성탄화의 기록에 언급된 천사들을 상징하기 위해 크리스마스 트리의 꼭대기에 천사를 사용하는 것이 인기를 끌었다고 썼습니다.[197] 또한 기독교의 성탄절 경축 행사에서 상록색을 띠는 크리스마스 트리는 영원한 생명을 주신 그리스도를 상징하며, 나무 위의 촛불이나 불빛은 베들레헴에서 태어난 세상의 빛-예수를 상징합니다.[198][199] 크리스마스 트리가 세워진 후, 가족을 위한 기독교 예배와 대중 예배가 출판되었습니다.[200][201] 일부 사람들은 크리스마스 트리를 상록수 가지의 사용과 이교도 나무 숭배의 각색을 포함한 동지를 둘러싼 이교도 전통과 의식의 기독교화로 생각합니다.[202] 8세기 전기 작가인 독일의 선교사였던 성 보니파체 (634–709)에 따르면, 토르에게 바치는 참나무에 도끼를 들고 가서 전나무를 가리켰는데, 전나무가 하늘을 가리키고 삼각형 모양을 하고 있어 더욱 어울리는 경건한 대상이라고 했는데, 삼위일체를 상징한다고 했습니다.[203] "크리스마스 트리"라는 영어 문구는 1835년에[204] 처음 기록되었고 독일어에서 가져온 것을 나타냅니다.[202][205][206]

16세기부터 멕시코의 토종 식물인 포인세티아는 베들레헴의 별이라는 기독교 상징성을 지닌 크리스마스와 연관되어 왔습니다. 그 나라에서는 스페인어로 성야의 꽃이라고 알려져 있습니다.[207][208] 다른 인기 있는 휴일 식물로는 홀리, 겨우살이, 레드 아마릴리스, 크리스마스 선인장이 있습니다.[209]

다른 전통 장식으로는 종, 양초, 사탕수수, 스타킹, 화환, 천사 등이 있습니다. 각 창문에 화환과 양초를 전시하는 것은 더 전통적인 크리스마스 전시입니다.[210] 보통 상록수에서 나오는 동심원의 잎들은 크리스마스 화환을 구성하고 있으며 기독교인들이 재림을 준비할 수 있도록 고안되었습니다. 각각의 창문에 있는 촛불들은 기독교인들이 예수 그리스도가 세상의 궁극적인 빛이라고 믿는다는 사실을 보여주기 위한 것입니다.[211]

거리를 따라 크리스마스 조명과 현수막을 걸거나 스피커에서 재생되는 음악, 눈에 띄는 장소에 크리스마스 트리를 배치할 수 있습니다.[212] 마을 광장과 소비자 쇼핑 구역이 장식을 후원하고 전시하는 것은 세계 여러 지역에서 흔한 일입니다. 세속적이거나 종교적인 크리스마스를 모티브로 한 밝은 색의 종이 롤은 선물을 포장할 목적으로 제조됩니다. 어떤 나라에서는 전통적으로 크리스마스 장식이 십이야에 내려집니다.[213]

천생연분

그리스도 성탄절을 기념하기 위해, 예수탄생극을 관람하는 것은 가장 오래된 크리스마스 전통 중 하나이며, 1223년에 예수탄생의 첫 재현이 열립니다.[214] 그 해 아시시의 프란치스코는 이탈리아에 있는 그의 교회 밖에서 예수탄생 장면을 모았고 아이들은 예수의 탄생을 축하하는 크리스마스 캐롤을 불렀습니다.[214] 매년, 이것은 커졌고 사람들은 프란치스코가 묘사한 예수 그리스도를 보기 위해 멀리서 여행을 했습니다. 드라마와 음악을 보러 온 것입니다.[214] 네이티브 연극은 결국 유럽 전역으로 퍼져 나갔고, 그곳에서 인기를 유지하고 있습니다. 성탄 전야와 성탄절 교회 예배는 종종 학교와 극장과 마찬가지로 예수탄생 연극을 공연하기 위해 왔습니다.[214] 프랑스, 독일, 멕시코, 스페인 등에서는 야외에서 흔히 성탄극을 거리에서 재연하기도 합니다.[214]

음악과 캐롤

현존하는 가장 초기의 크리스마스 찬송가는 4세기 로마에서 등장합니다. 밀라노 대주교 암브로즈가 쓴 "Veni redemptor gentium"과 같은 라틴 찬송가들은 아리아교에 반대하는 화신의 신학적 교리에 대한 소박한 진술이었습니다. 스페인 시인 프루덴티우스 (413년경)의 "아버지의 사랑이 시작되었다" (Corde natus ex parentis)는 오늘날에도 일부 교회에서 여전히 노래되고 있습니다.[215] 9세기와 10세기에 북유럽 수도원에서 크리스마스 "순례" 또는 "프로세"가 도입되었고, 베르나르 드 클레르보의 시대에 운율이 있는 일련의 스탠자로 발전했습니다. 12세기 파리의 수도승 아담. 빅터는 전통적인 크리스마스 캐롤에 더 가까운 것을 소개하면서 대중가요에서 음악을 끌어내기 시작했습니다. 영어로 된 크리스마스 캐롤은 존 오들레이의 1426년 작품에 등장하는데, 존 오들레이는 이 집 저 집을 다니는 '방아 선원'들이 부른 것으로 추정되는 25개의 "크리스마스 캐롤"을 나열합니다.[216]

현재 구체적으로 캐롤로 알려진 노래들은 원래 크리스마스뿐만 아니라 "수확 조수"와 같은 기념 행사 동안에 부르는 공동 민요들이었습니다. 교회에서 캐롤을 부르기 시작한 것은 그 이후의 일입니다. 전통적으로, 캐롤은 종종 중세의 코드 패턴을 기반으로 해왔고, 그들의 독특한 음악적 소리를 주는 것은 바로 이것입니다. "Personenthodie", "Good King Wenslas", "Indulci jubilo"와 같은 캐롤들은 중세로 바로 거슬러 올라갈 수 있습니다. 그들은 여전히 정기적으로 불려지는 가장 오래된 음악 작곡 중 하나입니다. "Adeeste Fideles" (O Come all ye faith)는 18세기 중반에 현재의 모습으로 나타납니다.

유럽의 루터교 지역에서 종교개혁 이후, 종교개혁가 마틴 루터가 미사 밖에서 캐롤을 부르는 관습을 주도하는 것 외에도, 캐롤을 작곡하고 예배에서 캐롤의 사용을 장려하면서, 캐롤을 부르는 것이 인기를 끌었습니다.[217] 18세기 영국의 개혁가 찰스 웨슬리, 초기 감리교의 신은 기독교 예배에 음악의 중요성을 이해했습니다. 멜로디에 많은 시편을 맞추는 것 외에도, 그는 적어도 세 개의 크리스마스 캐롤을 위한 텍스트를 썼습니다. 가장 잘 알려진 것은 원래 "하크!"라는 제목이었습니다. 나중에 "How All The Welkin Rings"로 개명된 웰킨의 반지! 헤럴드 천사가 노래합니다."[218]

종교적이지 않은 성격의 크리스마스 시즌송이 18세기 후반에 등장했습니다. "Deck the Halls"의 웨일스 멜로디는 1794년으로 거슬러 올라가며, 1862년 스코틀랜드 음악가 토마스 올리펀트가 가사를 추가했고, 미국의 "Jingle Bells"는 1857년 저작권이 있습니다. 다른 인기 있는 캐롤로는 "첫 번째 노을", "신의 안식, 메리 여러분", "홀리와 아이비", "세 척의 배를 보았다", "황량한 한겨울에", "조이 투 더 월드", "원스 인 로열 데이비드 시티", "양치기들이 그들의 양떼를 보는 동안" 등이 있습니다.[219] 19세기와 20세기에 아프리카계 미국인들의 영가와 그들의 영가 전통에 기반을 둔 크리스마스에 관한 노래들이 더 널리 알려지게 되었습니다. 재즈와 블루스의 변주곡을 포함하여, 20세기에 점점 더 많은 계절의 휴일 노래들이 상업적으로 생산되었습니다. 게다가, 레블스와 같은 민속 음악을 노래하는 그룹에서 중세 초기와 고전 음악을 연주하는 사람들에 이르기까지 초기 음악에 대한 관심이 부활했습니다.

가장 흔한 축제 노래 중 하나는 1930년대 영국의 웨스트 컨트리에서 유래한 "We Wish You a Merry Christmas"입니다.[220] 라디오는 1940년대와 1950년대의 버라이어티 쇼와 11월 말부터 12월 25일까지 크리스마스 음악을 독점적으로 재생하는 현대 방송국의 크리스마스 음악을 다루었습니다.[221] 할리우드 영화들은 홀리데이 인의 "화이트 크리스마스"와 빨간 코 순록 루돌프와 같은 새로운 크리스마스 음악을 선보였습니다.[221] 전통적인 캐롤 또한 "Hark!"와 같은 할리우드 영화에 포함되었습니다. The Herald Angels Sing "It's Wonderful Life (1946), 그리고 "Silent Night" (크리스마스 이야기).[221]

전통요리

특별한 크리스마스 가족 식사는 전통적으로 명절의 중요한 부분이며 제공되는 음식은 나라마다 크게 다릅니다. 어떤 지역들은 12종의 물고기가 제공되는 시칠리아와 같은 크리스마스 이브를 위한 특별한 식사를 합니다. 영국과 영국의 전통에 영향을 받은 나라들에서 표준 크리스마스 식사는 칠면조, 거위 또는 다른 큰 새, 그레이비, 감자, 야채, 때때로 빵과 사이다를 포함합니다. 크리스마스 푸딩, 민스 파이, 크리스마스 케이크, 파네톤, 율레로그 케이크 등 특별한 디저트도 준비되어 있습니다.[222][223] 중앙 유럽의 전통적인 크리스마스 식사는 잉어나 다른 생선 튀김입니다.[224]

카드

크리스마스 카드는 크리스마스 전 몇 주 동안 친구들과 가족들이 주고 받은 인사의 메시지를 보여줍니다. 전통적인 인사말에는 1843년 런던에서 헨리 콜 경이 제작한 첫 번째 상업용 크리스마스 카드와 매우 유사한 "즐거운 크리스마스와 행복한 새해를 기원합니다"라고 쓰여 있습니다.[225] 그것들을 보내는 관습은 E카드를 교환하는 현대적인 추세의 출현과 함께 넓은 단면의 사람들 사이에서 인기가 있습니다.[226][227]

크리스마스 카드는 상업적으로 디자인되고 계절과 관련된 상당한 양과 특징적인 예술작품으로 구입됩니다. 디자인의 내용은 예수의 그리스도 성탄화, 또는 베들레헴의 별과 같은 기독교 상징, 또는 지상의 성령과 평화를 모두 나타낼 수 있는 흰 비둘기를 묘사하는 크리스마스 이야기와 직접적으로 관련이 있을 수 있습니다. 다른 크리스마스 카드들은 더 세속적이고 크리스마스 전통, 산타클로스와 같은 신화적인 인물들, 양초, 홀리, 그리고 상투와 같은 크리스마스와 직접적으로 연관된 물건들, 혹은 크리스마스 행진, 눈 풍경, 그리고 북겨울의 야생동물과 같은 계절과 관련된 다양한 이미지들을 묘사할 수 있습니다.[228]

어떤 사람들은 시, 기도, 성경 구절이 적힌 카드를 선호하기도 하고, 어떤 사람들은 모든 것을 포함하는 "계절의 인사"로 종교와 거리를 두기도 합니다.[229]

기념우표

많은 나라들이 크리스마스에 기념 우표를 발행했습니다.[230] 우편 고객들은 종종 크리스마스 카드를 우편으로 보낼 때 이 우표를 사용할 것이고, 그 우표들은 우편물 목록에서 인기가 있습니다.[231] 이 우표는 크리스마스 씰과 달리 일반 우표이며 연중 내내 유효합니다. 보통 10월 초에서 12월 초 사이에 판매되며 상당한 양으로 인쇄됩니다.

선물하기

선물 교환은 현대 크리스마스 기념 행사의 핵심 측면 중 하나로, 전 세계 소매업체와 기업에게 1년 중 가장 수익성이 좋은 시기입니다. 크리스마스에 사람들은 성 니콜라스와 관련된 기독교 전통에 근거한 선물들과,[232] 마법사에 의해 아기 예수에게 주어졌던 금, 유향, 몰약의 선물들을 교환합니다.[233][234] 로마의 사투르날 기념행사에서 선물을 주는 관행이 기독교 관습에 영향을 미쳤을 수도 있지만, 다른 한편으로는 기독교의 "화신의 핵심 교리"가 선물을 주고 받는 것을 그 반복적이면서도 독특한 사건의 구조적 원리로 확고히 확립한 것은 성경의 마기였기 때문입니다. "그들의 모든 동료들과 함께, 그들은 신의 삶에 다시 참여함으로써 하나님의 선물을 받았습니다."[235] 그러나 토마스 J. 탈리(Thomas J. Talley)는 로마 황제 아우렐리안(Aurelian)이 12월 25일에 대체 축제를 열었는데, 이는 이미 그 날짜에 먼저 크리스마스를 기념하고 있던 기독교 교회의 증가율과 경쟁하기 위해서라고 주장합니다.[62]

선물이 있는 수치

많은 숫자들이 크리스마스와 선물의 계절적인 주기와 관련이 있습니다. 이들 중에는 산타클로스(네덜란드어로 성 니콜라스에서 유래됨), 페레 노 ë, 그리고 바이나흐츠만; 성 니콜라스 또는 신터클라스; 그리스도인, 크리스 크링글, 줄루푸키, 톰테/니스, 밥보 나탈레, 성 바실, 그리고 데드 모로즈로도 알려진 Father Christmas가 있습니다. 스칸디나비아 토트 (nisse라고도 함)는 산타 클로스 대신 유령으로 묘사되기도 합니다.

오늘날 이 인물들 중 가장 잘 알려진 것은 다양한 기원을 가진 빨간 옷을 입은 산타클로스입니다. 산타클로스라는 이름은 단순히 성 니콜라스를 의미하는 네덜란드 신터클라스로 거슬러 올라갈 수 있습니다. 니콜라스는 4세기 그리스 리키아 지방의 도시 마이라의 주교로, 유적지는 튀르키예 남서부의 현대 데므레에서 3킬로미터(1.9마일) 떨어져 있습니다. 다른 성스러운 속성들 중에서도, 그는 아이들을 돌보는 것, 관대함, 그리고 선물을 주는 것으로 유명했습니다. 그의 축제일인 12월 6일은 선물을 주는 것으로 많은 나라에서 기념하게 되었습니다.[112]

성 니콜라스는 전통적으로 주교의 복장을 입고 도우미들과 함께 등장하여 선물을 받을 자격이 있는지 아닌지를 결정하기 전에 지난 1년 동안 아이들의 행동에 대해 물었습니다. 13세기까지, 성 니콜라스는 네덜란드에 잘 알려져 있었고, 그의 이름으로 선물을 주는 관습은 중부와 남부 유럽의 다른 지역으로 퍼졌습니다. 16-17세기 유럽의 종교개혁에서 많은 개신교인들이 선물을 가져오는 사람을 크리스 크링글(Kris Kringle)로 바꾸었고, 선물을 주는 날짜도 12월 6일에서 크리스마스 이브로 바뀌었습니다.[112]

그러나 현대의 대중적인 산타클로스 이미지는 미국, 특히 뉴욕에서 만들어졌습니다. 이 변신은 워싱턴 어빙과 독일계 미국인 만화가 토마스 나스트(1840–1902)를 포함한 주목할 만한 기여자들의 도움으로 이루어졌습니다. 미국 독립 전쟁 이후, 뉴욕시의 몇몇 주민들은 그 도시의 비영어권 과거의 상징들을 찾아냈습니다. 뉴욕은 원래 네덜란드의 식민지 도시인 뉴 암스테르담으로 설립되었고 네덜란드의 신터클라스 전통은 세인트 니콜라스로 재창조되었습니다.[239]

현재 몇몇 라틴 아메리카 국가들(예를 들어 베네수엘라와 콜롬비아)의 전통은 산타가 장난감을 만들 때, 산타가 그 장난감들을 아이들의 집으로 실제로 배달해주는 아기 예수님에게 준다고 주장합니다. 전통적인 종교적 믿음과 미국에서 수입된 산타클로스 도상 사이의 화해

남티롤(이탈리아), 오스트리아, 체코, 독일 남부, 헝가리, 리히텐슈타인, 슬로바키아, 스위스에서는 그리스도인(체코의 예 ž리셰크, 헝가리의 예주스카, 슬로바키아의 예 ž리슈코)이 선물을 가져옵니다. 그리스 어린이들은 그 성인의 전례 축제 전날인 새해 전야에 성 바실리로부터 선물을 받습니다.[240] 독일 성. 니콜라우스는 (독일판 산타클로스 / Father Christmas) 바이나흐츠만과 동일하지 않습니다. 성 니콜라우스는 주교의 드레스를 입고 12월 6일에 여전히 작은 선물들(보통 사탕, 견과류, 과일)을 가지고 오고 크네히트 루프레히트와 동행합니다. 비록 전세계의 많은 부모들이 그들의 아이들에게 산타 클로스와 다른 선물을 가져다 주는 사람들에 대해 일상적으로 가르치고 있지만, 일부 부모들은 그것이 기만적이라고 생각하여 이 관행을 거부하기에 이르렀습니다.[241]

폴란드에는 여러 명의 선물을 주는 사람들이 존재하며, 지역과 개별 가정에 따라 다릅니다. 성 니콜라스(ś위 ę티 미코와즈)는 중부와 북동부 지역을 지배하고, 성 예수(Gwiazdor)는 대폴란드에서 가장 흔하며, 아기 예수(Zieci ą트코)는 상실레지아에서 유일하며, 작은 별(Gwiazdka)과 작은 천사(Anio southk)는 남부와 동남부에서 흔합니다. 프로스트 할아버지(지아덱 므로즈)는 폴란드 동부의 일부 지역에서는 덜 일반적으로 받아들여지고 있습니다.[242][243] 폴란드 전역에서 성 니콜라스는 12월 6일 성 니콜라스의 날에 선물을 주는 사람이라는 것에 주목할 필요가 있습니다.

율리우스력에 따른 날짜

러시아, 조지아, 마케도니아, 몬테네그로, 세르비아, 예루살렘을 포함한 동방 정교회의 일부 관할 구역은 더 오래된 율리우스력을 사용하여 축제를 표시합니다. 2023년을 기준으로 율리우스력과 현대 그레고리안력은 13일의 차이가 있는데, 대부분의 세속적인 목적으로 국제적으로 사용되고 있습니다. 그 결과, 율리우스력의 12월 25일은 현재 대부분의 정부와 국민들이 일상생활에서 사용하는 달력의 1월 7일에 해당합니다. 따라서, 앞서 언급한 정교회 신자들은 국제적으로 1월 7일로 여겨지는 12월 25일을 (따라서 크리스마스) 기념합니다.[244]

그러나 1923년 콘스탄티노플 공의회 이후 콘스탄티노플, 불가리아, 그리스, 루마니아, 안티오키아, 알렉산드리아, 알바니아, 키프로스, 핀란드, 미국 정교회 등의 다른 정교회 신자들이 [245]개정 율리우스력을 사용하기 시작했습니다. 현재는 정확히 그레고리력과 일치합니다.[246] 그러므로, 이 정통 기독교인들은 국제적으로 12월 25일로 여겨지는 같은 날을 12월 25일 (따라서 크리스마스)로 기념합니다.

아르메니아 사도교회가 그리스도의 탄생을 별도의 축일이 아니라 1월 6일 세례(테오파니)를 받는 날과 같은 날에 기념하는 고대 동방 기독교의 원래 관습을 이어간다는 사실은 더욱 복잡한 일입니다. 이것은 아르메니아의 공휴일이고, 1923년부터 아르메니아의 아르메니아 교회가 그레고리력을 사용했기 때문에 국제적으로 1월 6일로 간주되는 같은 날에 열립니다.[247]

그러나 작은 예루살렘 아르메니아 총대주교청도 있는데, 이것은 테오파니와 같은 날(1월 6일)에 그리스도의 탄생을 축하하는 아르메니아 전통 관습을 유지하지만, 그 날짜의 결정을 위해 율리우스력을 사용합니다. 그 결과, 이 교회는 세계 대다수의 사람들이 사용하는 그레고리력 1월 19일로 여겨지는 날에 "크리스마스" (더 적절하게는 테오파니)를 기념합니다.[248]

요약하면, 아래 표와 같이 그리스도의 탄생을 기념하기 위해 서로 다른 기독교 단체들이 사용하는 네 가지 다른 날짜가 있습니다.

리스팅

| 교회 또는 섹션 | 달력 | 날짜. | 그레고리안 날짜 | 메모 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 아르메니아 예루살렘 총대주교청 | 율리우스력 | 1월6일 | 1월19일 | 율리우스력 1월 6일과 그레고리안력 1월 19일 사이의 서신 교환은 2100년까지 지속됩니다. 다음 세기에는 그 차이가 하루 더 있을 것입니다. |

| 아르메니아 사도교회, 아르메니아 복음주의 교회 | 양력 | 1월6일 | 1월6일 | |

| 동방정교회 관할 지역은 콘스탄티노폴리스, 불가리아, 우크라이나[249], 그리스, 그리스, 루마니아, 안티오키아, 알렉산드리아, 알바니아, 키프로스, 핀란드, 미국의 정교회를 포함합니다. | 율리우스력 개정 | 12월 25일 | 12월 25일 | 수정된 율리우스력은 1923년 콘스탄티노플 공의회에서 합의되었습니다.[245] 비록 율리우스력을 따르지만, 동양의 고대 교회는 2010년에 그레고리력 날짜에 따라 크리스마스를 기념하기로 결정했습니다. |

| 기타 동방 정교회: 러시아, 조지아, 우크라이나 정교회 (모스크바 총대주교청), 마케도니아, 벨라루스, 몰도바, 몬테네그로, 세르비아, 예루살렘. 또한, 몇몇 비잔틴 전례 가톨릭 신자들과 비잔틴 전례 루터교 신자들. | 율리우스력 | 12월 25일 | 1월7일 | 율리우스력 12월 25일과 그레고리안력 1월 7일 사이의 서신은 2100년까지 유지됩니다. 2101년에서 2199년 사이에는 하루 차이가 더 날 것입니다.[citation needed] |

| 콥트 정교회 | 콥트력 | Koiak 29 or 28 (12월 25일) | 1월7일 | 율리우스력으로 8월(그레고리안으로는 9월)이라는 윤일을 콥트어로 삽입한 후, 크리스마스는 아이가 임신한 지 30일이 되는 9일과 5일의 정확한 간격을 유지하기 위해 코이악 28일에 기념됩니다.[citation needed] |

| 에티오피아 정교회 테와헤도 교회(단일), 에리트리아 정교회 테와헤도 교회(단일), 펜테이 교회(에티오피아-에리트리아 복음주의) (단일) | 에티오피아 달력 | 타샤 29 또는 28 (12월 25일) | 1월7일 | 에티오피아와 에리트레아가 율리우스력으로 8월(그레고리안으로는 9월)에 윤일을 삽입한 후, 크리스마스(리드데트 또는 제나라고도[250] 함)는 아이의 임신 30일 9개월과 5일의 정확한 간격을 유지하기 위해 타하스 28일에 기념됩니다.[251] 디아스포라의 대부분의 개신교(P'ent'ay/Evangelicals)들은 종교적 휴일을 위해 에티오피아 달력(타하 29/1월 7일) 또는 그레고리안 달력(12/25)을 선택할 수 있습니다. 이 옵션은 해당 동부 기념일이 서부 세계에서 공휴일이 아닐 때 사용됩니다(대부분의 디아스포라 개신교도가 이틀 동안 기념합니다).[citation needed] |

| 대부분의 서양 기독교 교회, 대부분의 동방 가톨릭 교회와 시민 달력. | 양력 | 12월 25일 | 12월 25일 | 동양의 아시리아 교회는 1964년에 그레고리력을 채택했습니다. |

경제.

크리스마스는 일반적으로 전 세계 많은 국가의 소매업체에서 가장 잘 팔리는 시즌입니다. 사람들이 축하하기 위해 선물, 장식 및 용품을 구매함에 따라 판매량이 급격히 증가합니다. 미국에서는 빠르면 10월부터 "크리스마스 쇼핑 시즌"이 시작됩니다.[252][253] 캐나다에서는 상인들이 할로윈(10월 31일) 직전에 광고 캠페인을 시작하고 11월 11일 '기억의 날' 이후 마케팅을 강화합니다. 영국과 아일랜드에서는 11월 중순부터 크리스마스 쇼핑 시즌이 시작되는데, 이 시기는 높은 거리의 크리스마스 전등이 켜질 무렵입니다.[254][255] 미국의 경우, 전체 개인 지출의 4분의 1이 크리스마스/휴일 쇼핑 시즌에 이루어지는 것으로 계산되었습니다.[256] 미국 인구조사국의 수치에 따르면 전국 백화점의 지출은 2004년 11월 208억 달러에서 12월 319억 달러로 54% 증가했습니다. 다른 부문에서는 크리스마스 전 지출 증가가 더욱 컸는데, 11월부터 12월까지 서점에서 100%, 보석상에서 170%의 구매가 급증했습니다. 같은 해 미국 소매점의 고용은 크리스마스까지 두 달 동안 160만 명에서 180만 명으로 증가했습니다.[257] 크리스마스에 완전히 의존하는 산업에는 매년 미국에서 19억개가 발송되는 크리스마스 카드와 살아있는 크리스마스 트리가 있으며, 이 중 2002년 미국에서 2,080만개가 절단되었습니다.[258] 2019년에 미국 성인 평균은 선물에만 920달러를 지출할 것으로 예상되었습니다.[259] 2010년 영국에서는 최대 80억 파운드가 크리스마스에 온라인으로 지출될 것으로 예상되었으며, 이는 전체 소매 축제 매출의 약 4분의 1에 해당합니다.[255]

대부분의 서양 국가에서, 크리스마스는 비즈니스와 상업을 위해 1년 중 가장 덜 활동적인 날입니다. 거의 모든 소매업, 상업 및 기관 사업체가 문을 닫고, 법이 요구하는 것이든 아니든 거의 모든 산업체가 (1년 중 다른 날보다) 활동을 중단합니다. 잉글랜드와 웨일즈에서는 2004년 크리스마스 날(거래)법에 의해 모든 대형 상점들이 크리스마스 날 거래를 할 수 없게 되었습니다. 이와 유사한 법안이 2007년 스코틀랜드에서 승인되었습니다. 영화사들은 아카데미 시상식의 후보 지명 기회를 극대화하기 위해 크리스마스 영화, 판타지 영화 또는 제작 가치가 높은 하이톤 드라마 등 많은 고예산 영화를 연휴 기간에 개봉합니다.[260]

한 경제학자의 분석에 따르면, 전반적인 지출 증가에도 불구하고, 크리스마스는 선물 증정의 효과 때문에 정통적인 미시경제 이론 하에서 치명적인 손실이라고 합니다. 이 손실은 선물을 준 사람이 그 물건을 위해 지출한 것과 선물을 받은 사람이 그 물건을 위해 지불했을 것 사이의 차이로 계산됩니다. 2001년 크리스마스에 미국에서만 40억 달러의 사망자가 발생한 것으로 추정되고 있습니다.[261][262] 복잡한 요인 때문에 이 분석은 현재의 미시경제 이론에서 발생할 수 있는 결함을 논의하는 데 사용되기도 합니다. 다른 치명적인 손실로는 크리스마스가 환경에 미치는 영향과 물질적인 선물이 종종 흰 코끼리로 인식된다는 사실, 유지 및 보관에 대한 비용을 부과하고 어수선함에 기여합니다.[263]

논란

크리스마스는 때때로 기독교인과 비기독교인 모두에게 다양한 출처로부터 논란과 공격의 대상이 되어 왔습니다. 역사적으로, 청교도들이 영국 연방 (1647–1660)에서 재위 기간 동안, 그리고 1659년에 청교도들이 성탄절이 성경에 언급되지 않았고, 따라서 개혁된 규정적인 예배 원칙을 위반했다는 이유로 성탄절 축하를 금지한 식민지 뉴잉글랜드에서는 금지되었습니다.[265][266] 장로교 신자들에 의해 지배되었던 스코틀랜드 의회는 1637년과 1690년 사이에 크리스마스의 준수를 금지하는 일련의 법들을 통과시켰습니다. 1871년까지 스코틀랜드에서 크리스마스는 공휴일이 되지 않았습니다.[125][267][268] 오늘날, 스코틀랜드 자유장로회나 북미 개혁장로회와 같은 일부 보수적인 개혁 교단들도 마찬가지로 규제적 원칙과 그들이 비성경적 기원으로 보는 크리스마스 기념을 거부합니다.[269][270] 또한[271] 소련과 같은 무신론자 국가들과 소말리아, 타지키스탄, 브루나이와 같은 다수의 이슬람 국가들에 의해 크리스마스 축하 행사가 금지되었습니다.[272]

팻 로버트슨의 미국 법과 정의 센터와 같은 일부 기독교인들과 단체들은 크리스마스에 대한 공격(그들을 "크리스마스에 대한 전쟁"이라고 부르는)을 주장하고 있습니다.[273] 그러한 단체들은 "크리스마스"라는 용어나 그 종교적인 측면에 대한 어떤 구체적인 언급도 점점 더 많은 광고주, 소매업자, 정부 (주로 학교), 그리고 다른 공공 및 민간 단체들에 의해 검열, 회피, 또는 거절되고 있다고 주장합니다. 한 가지 논란은 크리스마스 트리의 이름이 홀리데이 트리로 바뀐다는 것입니다.[274] 미국에서는 유대인의 하누카 기념일 당시에 포괄적으로 여겨지는 메리 크리스마스를 해피 홀리데이로 대체하는 경향이 있었습니다.[275] "Holidays"라는 용어의 사용이 가장 일반적인 미국과 캐나다에서 반대자들은 "크리스마스"라는 용어의 사용과 사용 회피가 정치적으로 옳다고 비난했습니다.[276][277][278] 1984년, 미국 대법원은 Lynch v. Donnelly에서 Road Island의 Pawtucket시가 소유하고 전시한 (Nativity 장면을 포함하는) 크리스마스 전시물이 수정헌법 제1조를 위반하지 않는다고 판결했습니다.[279] 미국의 이슬람 학자 압둘 말리크 무자히드는 이슬람교도들이 크리스마스에 동의하지 않더라도 존중하는 마음으로 대해야 한다고 말했습니다.[280]

중화인민공화국 정부는 공식적으로 국가 무신론을 옹호하고 있으며,[281] 이를 위해 반종교 운동을 전개해 왔습니다.[282] 2018년 12월, 관리들이 성탄절 이전에 기독교 교회를 급습하여 폐쇄를 강요했고, 크리스마스 트리와 산타클로스도 강제로 철거되었습니다.[283][284]

참고 항목

- 7월의 크리스마스 – 두번째 크리스마스 기념행사

- 크리스마스 평화 – 핀란드 전통

- 크리스마스 일요일 – 크리스마스 후 일요일

- 크리스마스 영화 목록

- 크리스마스 소설 목록 – 문학에 묘사된 크리스마스 - 전환 하는 페이지

- 리틀 크리스마스 – 1월 6일 대체 제목

- Nochebuena – Christmas Day 이전의 저녁 또는 하루 종일 대상에

- 다른 믿음체계와 비교한 미트라교 #12월 25일

- 매체별 크리스마스 – 매체별 크리스마스

메모들

- ^ 율리우스력을 사용하는 동방 기독교의 몇몇 분파들도 그 달력에 따라 12월 25일을 기념하는데, 지금은 그레고리력으로 1월 7일입니다. 아르메니아 교회는 그레고리력이 시작되기도 전에 1월 6일에 예수탄생을 지켰습니다. 대부분의 아르메니아 기독교인들은 그레고리력을 사용하며, 여전히 1월 6일에 크리스마스를 기념합니다. 일부 아르메니아 교회들은 율리우스력을 사용하여 그레고리안력으로 1월 19일에 크리스마스를 기념하고, 1월 18일은 크리스마스 이브입니다. 일부 지역에서는 12월 25일이 아닌 12월 24일에 주로 기념하기도 합니다.

- ^ English, Adam C. (October 14, 2016). Christmas: Theological Anticipations. Wipf and Stock Publishers. p. 70. ISBN 978-1-4982-3933-2.

According to Luke 1:26, Gabriel's annunciation to Mary took place in the "sixth month" of Elizabeth's pregnancy. That is, Mary conceives sixth months after Elizabeth. Luke repeats the uniqueness of the timing in verse 26. Counting six months from September 24 we arrive at March 25, the most likely date for the annunciation and conception of Mary. Nine months hence takes us to December 25, which turns out to be a surprisingly reasonable date for the birthday [of Jesus]. Someone might object that the birth could not have occurred in midwinter because it would have been too cold for shepherds in the fields keeping watch by night (Luke 2:8). Not so. In Palestine, the months of November through February mark the rainy season, the only time of the year sheep might find fresh green grass to graze. During the other ten months of the year, animals must content themselves on dry straw. So, the suggestion that shepherds might have stayed out in the fields with their flocks in late December, at the peak of the rainy season, is not only reasonable, it is most certain. ... And so, besides considering the timing of the conception, we must take note of the earliest church records. We have evidence from the second century, less than fifty years after the close of the New Testament, that Christians were remembering and celebrating the birth of the Lord. It is not true to say that the observance of the nativity was imposed on Christians hundreds of years later by imperial decree or by a magisterial church ruling. The observance sprang up organically from the authentic devotion of ordinary believers. This in itself is important. But, besides the fact that early Christians did celebrate the incarnation of the Lord, we should make note that they did not agree upon a set date for the observance. There was no one day on which all Christians celebrated Christmas in the early church. Churches in different regions celebrated the nativity on different days. The late second-century Egyptian instructor of Christian disciples, Clement of Alexandria, reported that some believers in his area observed the twenty-fourth or twenty-fifth day of the Egyptian month of Parmuthi (the month that corresponds to the Hebrew month of Nisan—approximately May 20). The Basilidian Christians held to the eleventh or fifteen of Tubi (January 6 and 10). Clement made his own computations by counting backward from the death of Emperor Commodus, the son of Marcus Aurelius. By this method he deduced a birthdate of November 18. Other Alexandrian and Egyptian Christians adopted January 4 or 5. In so doing, they replaced the Alexandrian celebration of the birth of Aion, Time, with the birth of Christ. The regions of Nicomedia, Syria, and Caesarea celebrated Christ's birthday on Epiphany, January 6. ... According to researcher Susan Roll, the Chronograph or Philocalian Calendar is the earliest authentic document to place the birth of Jesus on December 25. ... And we should remember that although the Chronograph provides the first record of December 25, the custom of venerating the Lord's birth on that day was most likely established well before its publication. That is to say, December 25 didn't originate with the Chronograph. It must have counted as common knowledge, at least in Rome, to warrant its inclusion in the Chronograph. Soon after this time, we find other church fathers such John Chrysostom, Augustine, Jerome, and Leo confirming the twenty-fifth as the traditional date of celebration.

참고문헌

- ^ a b "Christmas as a Multi-Faith Festival" (PDF). BBC Learning English. December 29, 2005. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 1, 2008. Retrieved September 30, 2008.

- ^ a b "In the U.S., Christmas Not Just for Christians". Gallup, Inc. December 24, 2008. Archived from the original on November 16, 2012. Retrieved December 16, 2012.

- ^ "The Global Religious Landscape Christians". Pew Research Center. December 18, 2012. Archived from the original on March 10, 2015. Retrieved May 23, 2014.

- ^ "Christmas Strongly Religious For Half in U.S. Who Celebrate It". Gallup, Inc. December 24, 2010. Archived from the original on December 7, 2012. Retrieved December 16, 2012.

- ^ a b Forbes, Bruce David (October 1, 2008). Christmas: A Candid History. University of California Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-520-25802-0.

In 567 the Council of Tours proclaimed that the entire period between Christmas and Epiphany should be considered part of the celebration, creating what became known as the twelve days of Christmas, or what the English called Christmastide.

On the last of the twelve days, called Twelfth Night, various cultures developed a wide range of additional special festivities. The variation extends even to the issue of how to count the days. If Christmas Day is the first of the twelve days, then Twelfth Night would be on January 5, the eve of Epiphany. If December 26, the day after Christmas, is the first day, then Twelfth Night falls on January 6, the evening of Epiphany itself.

After Christmas and Epiphany were in place, on December 25 and January 6, with the twelve days of Christmas in between, Christians slowly adopted a period called Advent, as a time of spiritual preparation leading up to Christmas. - ^ 캐나다의 문화유산 – 공휴일2009년 11월 24일, Wayback Machine – Government of Canada에 보관되었습니다. 2009년 11월 27일 검색.

- ^ 2009년 연방 공휴일 2013년 1월 16일, 웨이백 머신 – 미국 인사관리국에서 보관. 2009년 11월 27일 검색.

- ^ 은행 휴일 및 영국 여름 시간 2011년 5월 15일 Wayback Machine – HM Government에서 보관되었습니다. 2009년 11월 27일 검색.

- ^ Ehorn, Lee Ellen; Hewlett, Shirely J.; Hewlett, Dale M. (September 1, 1995). December Holiday Customs. Lorenz Educational Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-4291-0896-6.

- ^ Nick Hytrek, "비기독교인들은 크리스마스의 세속적인 면에 집중합니다." 2009년 11월 14일, Wayback Machine, Suoux City Journal, 2009년 11월 10일에 보관되었습니다. 2009년 11월 18일 검색.

- ^ Crump, William D. (September 15, 2001). The Christmas Encyclopedia (3 ed.). McFarland. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-7864-6827-0.

Christians believe that a number of passages in the Bible are prophecies about future events in the life of the promised Messiah or Jesus Christ. Most, but not all, of those prophecies are found in the Old Testament ... Born in Bethlehem (Micah 5:2): "But thou, Bethlehem Ephratah, though thou be little among the thousands of Juda, yet out of thee shall he come forth unto me that is to be ruler in Israel; whose goings forth have been from of old, from everlasting."

- ^ Tucker, Ruth A. (2011). Parade of Faith: A Biographical History of the Christian Church. Zondervan. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-310-20638-5.

According to gospel accounts, Jesus was born during the reign of Herod the Great, thus sometime before 4 BCE. The birth narrative in Luke's gospel is one of the most familiar passages in the Bible. Leaving their hometown of Nazareth, Mary and Joseph travel to Bethlehem to pay taxes. Arriving late, they find no vacancy at the inn. They are, however, offered a stable, most likely a second room attached to a family dwelling where animals were sheltered—a room that would offer some privacy from the main family room for cooking, eating, and sleeping. This "city of David" is the little town of Bethlehem of Christmas-carol fame, a starlit silhouette indelibly etched on Christmas cards. No sooner was the baby born than angels announced the news to shepherds who spread the word.

- ^ 코리나 로플린, 마이클 R. 프렌더가스트, 로버트 C. 레이브, 코리나 로플린, 질 마리아 머디, 테레즈 브라운, 메리 패트리샤 스톰, 앤 E. 데겐하르트, 질 마리아 머디, 앤 E. 데겐하르트, 테레즈 브라운, 로버트 C. Rabe, Mary Patricia Storms, Michael R. Prendergast, Sundays, Seasons, Weekly 2011 소스북: 목회자를 위한 연감, Wayback Machine, Liturgy Training Publications, 2010, p. 29.

- ^ "서기 354년의 연대기. 12부: 순교자들의 기념" 2011년 11월 22일 웨이백 머신, 터툴리안 프로젝트에 보관. 2006. 2011년 11월 24일 검색.

- ^ Roll, Susan K. (1995). Toward the Origins of Christmas. Peeters Publishers. p. 133. ISBN 978-90-390-0531-6.

- ^ a b Hale Bradt (2004). Astronomy Methods (PDF). p. 69. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 20, 2018..

롤, 87쪽

이 두 문헌은 3월 25일이 춘분이었고, Roll은 De Solstitis et Aequinoctis라는 작품을 가리킵니다.2022년 2월 5일, 12월 25일을 동지로 하는 웨이백 머신에 보관되었습니다. 그러나 율리우스 카이사르 시대에는 사실 동지가 23일이나 24일이었습니다. - ^ a b Melton, J. Gordon (2011). Religious Celebrations: An Encyclopedia of Holidays, Festivals, Solemn Observances, and Spiritual Commemorations [2 volumes]: An Encyclopedia of Holidays, Festivals, Solemn Observances, and Spiritual Commemorations. ABC-CLIO. p. 39. ISBN 978-1-59884-206-7.

The March 25 date, which tied together the beginning of Mary's pregnancy and the incarnation of God in Jesus as occurring nine months before Christmas (December 25), supplied the rationale for setting the beginning of the ecclesiastical and legal year. ... Both the Anglicans and the Lutherans have continued to observe the March 25 date for celebrating the Annunciation.

- ^ The Liturgical Year. Thomas Nelson. November 3, 2009. ISBN 978-1-4185-8073-5. Retrieved April 2, 2009.

Christmas is not really about the celebration of a birth date at all. It is about the celebration of a birth. The fact of the date and the fact of the birth are two different things. The calendrical verification of the feast itself is not really that important ... What is important to the understanding of a life-changing moment is that it happened, not necessarily where or when it happened. The message is clear: Christmas is not about marking the actual birth date of Jesus. It is about the Incarnation of the One who became like us in all things but sin (Hebrews 4:15) and who humbled Himself "to the point of death-even death on a cross" (Phil. 2:8). Christmas is a pinnacle feast, yes, but it is not the beginning of the liturgical year. It is a memorial, a remembrance, of the birth of Jesus, not really a celebration of the day itself. We remember that because the Jesus of history was born, the Resurrection of the Christ of faith could happen.

- ^ "The Christmas Season". CRI / Voice, Institute. Archived from the original on April 7, 2009. Retrieved April 2, 2009.

The origins of the celebrations of Christmas and Epiphany, as well as the dates on which they are observed, are rooted deeply in the history of the early church. There has been much scholarly debate concerning the exact time of the year when Jesus was born, and even in what year he was born. Actually, we do not know either. The best estimate is that Jesus was probably born in the springtime, somewhere between the years of 6 and 4 BC, as December is in the middle of the cold rainy season in Bethlehem, when the sheep are kept inside and not on pasture as told in the Bible. The lack of a consistent system of timekeeping in the first century, mistakes in later calendars and calculations, and lack of historical details to cross-reference events have led to this imprecision in fixing Jesus' birth. This suggests that the Christmas celebration is not an observance of a historical date, but a commemoration of the event in terms of worship.

- ^ The School Journal, Volume 49. Harvard University. 1894. Retrieved April 2, 2009.

Throughout the Christian world the 25th of December is celebrated as the birthday of Jesus Christ. There was a time when the churches were not united regarding the date of the joyous event. Many Christians kept their Christmas in April, others in May, and still others at the close of September, till finally December 25 was agreed upon as the most appropriate date. The choice of that day was, of course, wholly arbitrary, for neither the exact date not the period of the year at which the birth of Christ occurred is known. For purposes of commemoration, however, it is unimportant whether the celebration shall fall or not at the precise anniversary of the joyous event.

- ^ West's Federal Supplement. West Publishing Company. 1990.

While the Washington and King birthdays are exclusively secular holidays, Christmas has both secular and religious aspects.

- ^ a b Huckabee, Tyler (December 9, 2021). "No, Christmas Trees Don't Have 'Pagan' Roots". Relevant Magazine. Retrieved December 9, 2022.

- ^ "Poll: In a changing nation, Santa endures". Associated Press. December 22, 2006. Archived from the original on December 26, 2018. Retrieved December 24, 2018.

- ^ a b c Martindale, Cyril Charles (1908). "Christmas". The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 3. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Schoenborn, Christoph (1994). God's human face: the Christ-icon. p. 154. ISBN 978-0-89870-514-0.

- ^ Galey, John (1986). Sinai and the Monastery of St. Catherine. p. 92. ISBN 978-977-424-118-5.

- ^ "Christmas Origin, Definition, Traditions, History, & Facts Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved December 22, 2021.

- ^ 크리스천마스, n., 옥스포드 영어 사전. 12월 12일 회수.

- ^ a b 중세 영어 사전의 "크리스마스". 2012년 1월 5일 Wayback Machine에서 아카이브됨

- ^ Griffiths, Emma (December 22, 2004). "Why get cross about Xmas?". BBC News. Archived from the original on November 11, 2011. Retrieved December 12, 2011.

- ^ a b Hutton, Ronald (2001). The Stations of the Sun: A History of the Ritual Year in Britain. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-285448-3.

- ^ 보즈워스 & 톨러의 "한겨울". 2012년 1월 13일 Wayback Machine에서 아카이브됨

- ^ Serjeantson, Mary Sidney (1968). A History of Foreign Words in English.

- ^ "Online Etymology Dictionary". Archived from the original on January 13, 2012. Retrieved December 13, 2011.

- ^ Yule 2012년 1월 13일 Wayback Machine, 온라인 어원 사전에 보관되었습니다. 12월 12일 회수.

- ^ 온라인 어원 사전, Noel Archive the Wayback Machine에서 2012년 1월 13일 접속, 2022년 1월 3일 접속

- ^ "Толковый словарь Даля онлайн". slovardalja.net. Retrieved December 25, 2022.

- ^ "성경문학" 2015년 4월 26일, æ디아 브리태니커 백과사전, Wayback Machine에서 보관, 2011. 웹. 2011년 1월 22일

- ^ Guzik, David (December 8, 2015). "Matthew Chapter 2". Enduring Word. Retrieved December 25, 2020.

- ^ a b c d English, Adam C. (October 14, 2016). Christmas: Theological Anticipations. Wipf and Stock Publishers. pp. 70–71. ISBN 978-1-4982-3933-2.

- ^ 원고에는 VIII kal이라고 적혀있습니다. 이안. 베틀렘 이우대의 나투스 크리스투스. ("서기 354년의 연대기. 제12부: 2011년 11월 22일 웨이백 머신에 보관된 순교자들의 기념"("The Tertulian Project. 2006)

- ^ a b c d e f Bradshaw, Paul (2020). "The Dating of Christmas". In Larsen, Timothy (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Christmas. Oxford University Press. pp. 7–10.

- ^ "Christmas and its cycle". New Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 3 (2nd ed.). Catholic University of America Press. 2002. pp. 550–557.

- ^ Hyden, Marc (December 20, 2021). "Merry Christmas, Saturnalia or festival of Sol Invictus?". Newnan Times-Herald. Archived from the original on December 26, 2022. Retrieved February 17, 2023.

Around 274 ADᵃ, Emperor Aurelian set December 25—the winter solstice at the time—for the celebration of Sol Invictus who was the 'Unconquered Sun' god. 'A marginal note on a manuscript of the writings of the Syriac biblical commentator Dionysius bar-Salibi states that in ancient times the Christmas holiday was actually shifted from January 6 to December 25 so that it fell on the same date as the pagan Sol Invictus holiday,' reads an excerpt from Biblical Archaeology. / Could early Christians have chosen December 25 to coincide with this holiday? 'The first celebration of Christmas observed by the Roman church in the West is presumed to date to [336 AD],' per the Encyclopedia Romanaᵃ, long after Aurelian established Sol Invictus' festival.

(a) "Sol Invictus and Christmas". Encyclopaedia Romana. - ^ Wainwright, Geoffrey; Westerfield Tucker, Karen Beth, eds. (2005). The Oxford History of Christian Worship. Oxford University Press. p. 65. ISBN 978-0-19-513886-3. Retrieved February 3, 2012.

- ^ a b Roy, Christian (2005). Traditional Festivals: A Multicultural Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. p. 146. ISBN 978-1-57607-089-5. Archived from the original on January 11, 2014. Retrieved February 3, 2012.

- ^ Pokhilko, Hieromonk Nicholas. "History of Epiphany". Archived from the original on September 23, 2016. Retrieved December 27, 2017.

- ^ Hastings, James; Selbie, John A., eds. (2003). Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics. Vol. 6. Kessinger Publishing Company. pp. 603–604. ISBN 978-0-7661-3676-2. Archived from the original on November 22, 2018. Retrieved February 3, 2012.

- ^ Frøyshov, Stig Simeon. "[Hymnography of the] Rite of Jerusalem". Canterbury Dictionary of Hymnology.

- ^ Kelly, Joseph F., The Origines of Christmas, Liturical Press, 2004, pp. 67–69.

- ^ a b Hijmans, S.E., Sol: The Sun in the Art and Religies of Rome, 2009, p.584.

- ^ 맥고완, 앤드류, 어떻게 12월 25일이 크리스마스가 되었는가 2012년 12월 14일 웨이백 머신, 바이블 히스토리 데일리, 2016년 2월 12일.

- ^ 그리스와 로마의 계절 축제 브루마

대 플리니우스, 자연사, 18:592022년 6월 16일 Wayback Machine에 보관(2022년 5월 4일 라틴어 아카이브에 있는 문단 220, Wayback Machine에 보관) - ^ 사실 동지는 그 때 23일이나 24일에 발생했습니다. 4년의 공간에서, 하지는 윤년 전에 율리우스력에서 가장 늦게 발생합니다. 2007년 10월 13일 지구의 계절 이쿼녹스(Earth's Seasons Equinques), 솔스티스(Solstices), 근일점(Perihelion), 아펠리온(Aphelion) 아카이브(Archive)에 따르면, 2019년은 그레고리력으로 22일, 또는 율리우스력으로 12월 9일 오전 4시 19분에 웨이백 머신(Wayback Machine)에서 발생했습니다. 기원전 1년에서 서기 2000년 사이에 연속적인 겨울용해 사이의 일수는 365.242883일에서 365.242740일로 다양했습니다. 따라서 지난 2000년 동안의 평균치는 365.24281일로 율리우스년 평균치보다 0.00719일 적었습니다. 이것은 하지가 2000×0.00719=14.38일 후, 즉 한낮의 12월 23일이었다는 것을 의미합니다. 100년 전에는 24일이었을 것입니다.

- ^ 롤, 페이지 108

- ^ 말라치 4:2.

- ^ 어거스틴, 설교 192 2016년 11월 25일 웨이백 기계에서 보관.

- ^ a b 히즈만스, S.E., 솔, 로마의 예술과 종교에서의 태양, 2009, 595쪽. ISBN 978-90-367-3931-3 2013년 5월 10일 Wayback Machine에서 보관

- ^ Senn, Frank C. (2012). Introduction to Christian Liturgy. Fortress Press. ISBN 978-1-4514-2433-1. Archived from the original on December 31, 2015. Retrieved December 23, 2014.

- ^ a b Roll, Susan K. (1995). Towards the Origin of Christmas. Kok Pharos Publishing. p. 87, cf. note 173. ISBN 978-90-390-0531-6. Archived from the original on April 9, 2021. Retrieved April 9, 2021. 오류 인용: 명명된 참조 "Roll87"은 다른 내용으로 여러 번 정의되었습니다(도움말 페이지 참조).

- ^ 옥스퍼드 기독교 교회 사전 (Oxford University Press, 2005, ISBN 978-0-19-280290-3), 기사 "크리스마스".

- ^ a b c Talley, Thomas J. (1991). The Origins of the Liturgical Year. Liturgical Press. pp. 88–91. ISBN 978-0-8146-6075-1. Retrieved December 27, 2016.

- ^ a b Bradshaw, Paul F., "크리스마스" 2017년 1월 9일 Wayback Machine, The New SCM Dictionary of Wirsty, Antious and Modern Ltd, 2002.

- ^ 롤, 페이지 107

- ^ a b c Bradshaw, Paul (2020). "The Dating of Christmas". In Larsen, Timothy (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Christmas. Oxford University Press. pp. 4–5.

- ^ Andrew McGowan. "How December 25 Became Christmas". Bible Review & Bible History Daily. Biblical Archaeology Society. Archived from the original on December 14, 2012. Retrieved February 24, 2011.

- ^ 롤(1995), 페이지 88

- ^ Hijmans, p.584

- ^ Kelly, Joseph F. (2004). The Origins of Christmas. Liturgical Press. p. 60. ISBN 978-0-8146-2984-0. 여기 온라인 [1] 2017년 2월 19일 Wayback Machine에서 아카이브되었습니다.

- ^ Collinge, William J. (2012). Historical Dictionary of Catholicism. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-5755-1. Archived from the original on December 31, 2015. Retrieved December 23, 2014.

- ^ 롤, 87쪽.

- ^ 롤, p.89: "듀슈네는 어떤 가부장적인 저자나 본문을 직접적으로 언급함으로써 그가 지지하지 않는 추측을 덧붙입니다: 상징적인 수 체계는 분수의 불완전성을 허용하지 않기 때문에, 그리스도는 틀림없이 완전히 여러 해를 살았을 것이라고 생각될 것입니다. 그러나 뒤센은 인정할 수밖에 없었습니다. 만약 우리가 어떤 저자에게서 이 설명을 완전히 찾을 수 있다면 이 설명은 더 쉽게 받아들여질 것입니다. 불행히도 우리는 그것이 포함된 텍스트가 없다는 것을 알고 있습니다."

- ^ a b c English, Adam C. (October 14, 2016). Christmas: Theological Anticipations. Wipf and Stock Publishers. pp. 70–71. ISBN 978-1-4982-3933-2.

First, we should examine the biblical evidence regarding the timing of the conception. … The angel Gabriel appeared to Zechariah, husband of Elizabeth and father of John the Baptizer, on the day he was chosen by lot to enter the sanctuary of the Lord and offer incense (Luke 1:9) Zechariah belonged to the tribe of Levi, the one tribe especially selected by the Lord to serve as priests. Not restricted to any one tribal territory, the Levite priests dispersed throughout the land of Israel. Nevertheless, many chose to live near Jerusalem in order to fulfill duties in the Temple, just like Zechariah who resided at nearby Ein Karem. Lots were cast regularly to decide any number of priestly duties: preparing the altar, making the sacrifice, cleaning the ashes, burning the morning or evening incense. Yet, given the drama of the event, it would seem that he entered the Temple sanctuary on the highest and holiest day of the year, the Day of Atonement, Yom Kippur. There, beside the altar of the Lord, a radiant angel gave news of the child to be born to Elizabeth. The date reckoned for this occurrence is September 24, based on computations from the Jewish calendar in accordance with Leviticus 23 regarding the Day of Atonement. According to Luke 1:26, Gabriel's annunciation to Mary took place in the "sixth month" of Elizabeth's pregnancy. That is, Mary conceives six months after Elizabeth. Luke repeats the uniqueness of the timing in verse 36. Counting six months from September 24 we arrive at March 25, the most likely date for the annunciation and conception of Mary. Nine months hence takes us to December 25, which turns out to be a surprisingly reasonable date for the birthday. … In Palestine, the months of November mark the rainy season, the only time of the year sheep might find fresh green grass to graze. During the other ten months of the year, animals must content themselves on dry straw. So, the suggestion that shepherds might have stayed out in the fields with their flocks in late December, at the peak of the rainy season, is not only reasonable, it is most certain.

- ^ Bonneau, Normand (1998). The Sunday Lectionary: Ritual Word, Paschal Shape. Liturgical Press. p. 114. ISBN 978-0-8146-2457-9.

The Roman Church celebrates the annunciation of March 25 (the Roman calendar equivalent to the Jewish fourteenth Nisan); hence Jesus' birthday occurred nine months later on December 25. This computation matches well with other indications in Luke's gospel. Christians conjectured that the priest Zechariah was serving in the temple on the Day of Atonement, roughly at the autumnal equinox, when the angel announced to him the miraculous conception of John the Baptist. At her annunciation, Mary received news that Elizabeth was in her sixth month. Sixth months after the autumnal equinox means that Mary conceived Jesus at the vernal equinox (March 25). If John the Baptist was conceived at the autumnal equinox, he was born at the summer solstice nine months later. Thus even to this day the liturgical calendar commemorates John's birth on June 24. Finally, John 3:30, where John the Baptist says of Jesus: "He must increase, but I must decrease," corroborates this tallying of dates. For indeed, after the birth of Jesus at the winter solstice the days increase, while after the birth of John at the summer solstice the days decrease.

- ^ 콜링, 가톨릭 역사사전, p.38

- ^ Bartlett, Robert (2015). Why Can the Dead Do Such Great Things?: Saints and Worshippers from the Martyrs to the Reformation. Princeton University Press. p. 154.

- ^ 롤, 페이지 105

- ^ Rouwhorst, Gerard (2020). "The origins and transformations of early Christian feasts". Rituals in Early Christianity. Brill. p. 43.

- ^ 켈리, 80쪽

- ^ a b c Forsythe, Gary (2012). Time in Roman Religion: One Thousand Years of Religious History. Routledge. p. 141.

- ^ Elm, Susanna (2012). Sons of Hellenism, Fathers of the Church. University of California Press. p. 287.

- ^ Remijsen, Sofie (2015). The End of Greek Athletics in Late Antiquity. Cambridge University Press. p. 133.

- ^ (4~8세기의 기독교와 이교도에서 인용됨, Ramsay MacMullen). 예일: 1997, 페이지 155).

- ^ 뉴턴, 아이작, 다니엘의 예언과 성 요한 묵시록에 관한 관찰. John은 2012년 9월 18일 Wayback Machine(1733)에 보관했습니다. Ch. XI. 그리스도인들이 예수를 말라치 4장 2절에서 예언한 "의의 태양"으로 여겼기 때문에 태양의 연결이 가능합니다. "그러나 나의 이름을 두려워하는 여러분에게, 의의 태양은 날개에 치유와 함께 떠오를 것입니다. 당신은 종마에서 송아지처럼 뛰어내리실 것입니다."

- ^ Roll, Susan K. (1995). Toward the Origins of Christmas. Peeters Publishers. p. 130. ISBN 978-90-390-0531-6. Archived from the original on November 2, 2015. Retrieved June 20, 2015.

- ^ 헤르만 유세너, 다스 웨이나흐츠페스트. 인: 종교는 운터수충겐(Regiasgeschichtliche Untersuchungen), 1부. 세컨드 에디션. Verlag von Max Cohen & Son, Bon 1911.

- ^ Hijmans, S.E. (2009). The Sun in the Art and Religions of Rome. p. 588. ISBN 978-90-367-3931-3. Archived from the original on May 10, 2013.

- ^ Tucker, Karen B. Westerfield (2000). "Christmas". In Hastings, Adrian; Mason, Alistair; Pyper, Hugh (eds.). The Oxford Companion to Christian Thought. Oxford University Press. p. 114. ISBN 978-0-19-860024-4.

- ^ Nothaft, C. Philipp E. (2013). "Early Christian Chronology and the Origins of the Christmas Date". Questions Liturgiques/Studies in Liturgy. Peeters. 94 (3): 248. doi:10.2143/QL.94.3.3007366.

Although HRT is nowadays used as the default explanation for the choice of 25 December as Christ's birthday, few advocates of this theory seem to be aware of how paltry the available evidence actually is.

- ^ McGrath, Alister E. (January 27, 2015). Christianity: An Introduction. John Wiley & Sons. p. 239. ISBN 978-1-118-46565-3.

- ^ a b c d e f g Murray, Alexander, "중세의 크리스마스" 2011년 12월 13일, Wayback Machine, History Today, 1986년 12월 36일 (12), pp. 31 – 39.

- ^ a b Standiford, Les (2008). The Man Who Invented Christmas: How Charles Dickens's A Christmas Carol Rescued His Career and Revived Our Holiday Spirits. Crown. ISBN 978-0-307-40578-4.

- ^ a b Minzesheimer, Bob (December 22, 2008). "Dickens' classic 'Christmas Carol' still sings to us". USA Today. Archived from the original on November 6, 2009. Retrieved April 30, 2010.

- ^ Neal, Daniel (1822). The History of the Puritans. William Baynes and Son. p. 193.

They disapproved of the observation of sundry of the church-festivals or holidays, as having no foundation in Scripture, or primitive antiquity.

- ^ a b c d Durston, Chris (December 1985). "Lords of Misrule: The Puritan War on Christmas 1642–60". History Today. Vol. 35, no. 12. pp. 7–14. Archived from the original on March 10, 2007.

- ^ a b c d Barnett, James Harwood (1984). The American Christmas: A Study in National Culture. Ayer Publishing. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-405-07671-8.

- ^ "크리스마스 – 고대의 휴일" 2007년 5월 9일, Wayback Machine, The History Channel, 2007.

- ^ NEWS, SA (December 24, 2022). "Christmas Day 2022: Facts, Story & Quotes About Merry Christmas". SA News Channel. Retrieved December 26, 2022.

- ^ a b 시메크(2007:379).

- ^ 커피맨, 엘샤. "왜 12월 25일?" 2008년 9월 19일, Wayback Machine Christian History & Biography, Christian Today, 2000.

- ^ Simek (2010:180, 379–380).

- ^ Weiser, Franz Xaver (1958). Handbook of Christian Feasts and Customs. Harcourt.

- ^ "Koliada". Encyclopediaofukraine.com. Retrieved November 19, 2012.

- ^ Hynes, Mary Ellen (1993). Companion to the Calendar. Liturgy Training Publications. p. 8. ISBN 9781568540115.

In the year 567 the church council of Tours called the 13 days between December 25 and January 6 a festival season.

- ^ Hill, Christopher (2003). Holidays and Holy Nights: Celebrating Twelve Seasonal Festivals of the Christian Year. Quest Books. p. 91. ISBN 9780835608107.

This arrangement became an administrative problem for the Roman Empire as it tried to coordinate the solar Julian calendar with the lunar calendars of its provinces in the east. While the Romans could roughly match the months in the two systems, the four cardinal points of the solar year—the two equinoxes and solstices—still fell on different dates. By the time of the first century, the calendar date of the winter solstice in Egypt and Palestine was eleven to twelve days later than the date in Rome. As a result the Incarnation came to be celebrated on different days in different parts of the Empire. The Western Church, in its desire to be universal, eventually took them both—one became Christmas, one Epiphany—with a resulting twelve days in between. Over time this hiatus became invested with specific Christian meaning. The Church gradually filled these days with saints, some connected to the birth narratives in Gospels (Holy Innocents' Day, December 28, in honor of the infants slaughtered by Herod; St. John the Evangelist, "the Beloved," December 27; St. Stephen, the first Christian martyr, December 26; the Holy Family, December 31; the Virgin Mary, January 1). In 567, the Council of Tours declared the twelve days between Christmas and Epiphany to become one unified festal cycle.

- ^ Federer, William J. (January 6, 2014). "On the 12th Day of Christmas". American Minute. Retrieved December 25, 2014.

In 567 AD, the Council of Tours ended a dispute. Western Europe celebrated Christmas, December 25, as the holiest day of the season... but Eastern Europe celebrated Epiphany, January 6, recalling the Wise Men's visit and Jesus' baptism. It could not be decided which day was holier, so the Council made all 12 days from December 25 to January 6 "holy days" or "holidays," These became known as "The Twelve Days of Christmas."

- ^ Kirk Cameron, William Federer (November 6, 2014). Praise the Lord. Trinity Broadcasting Network. Event occurs at 01:15:14. Archived from the original on December 25, 2014. Retrieved December 25, 2014.

Western Europe celebrated Christmas December 25 as the holiest day. Eastern Europe celebrated January 6 the Epiphany, the visit of the Wise Men, as the holiest day... and so they had this council and they decided to make all twelve days from December 25 to January 6 the Twelve Days of Christmas.

- ^ "Who was Charlemagne? The unlikely king who became an emperor". National Geographic. Retrieved November 30, 2023.

- ^ "William the Conqueror: Crowned at Christmas". The History Press. Retrieved November 30, 2023.

- ^ a b 맥그리비, 패트릭. "Place in the American Christmas," (JSTOR Archive at the Wayback Machine, 2018년 12월 15일), 지리학 리뷰, Vol. 80, No. 1. 1990년 1월 32-42쪽. 2007년 9월 10일 검색.

- ^ a b c Restad, Penne L. (1995). Christmas in America: a History. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-510980-1.

- ^ a b c Forbes, Bruce David, Christmas: 솔직한 역사, University of California Press, 2007, ISBN 0-520-25104-0, 페이지 68–79.

- ^ Lowe, Scott C. (January 11, 2011). Christmas. John Wiley & Sons. p. 226. ISBN 978-1-4443-4145-4.

- ^ Shawcross, John T. (January 1, 1993). John Milton. University Press of Kentucky. p. 249. ISBN 978-0-8131-7014-5.

Milton was raised an Anglican, trained to become an Anglican minister, and remained an Anglican through the signing of the subscription books of Cambridge University in both 1629 and 1632, which demanded an allegiance to the state church and its Thirty-nine Articles.

- ^ Browne, Sammy R (April 29, 2012). A Brief Anthology of English Literature, Volume 1. p. 412. ISBN 978-1-105-70569-4.

His father had wanted him to practice law but Milton considered writing poetry his life's work. At 21 years old, he wrote a poem, "On the morning of Christ's Nativity," a work that is still widely read during Christmas.

- ^ Heinz, Donald (2010). Christmas: Festival of Incarnation. Fortress Press. p. 94. ISBN 978-1-4514-0695-5.

- ^ Old, Hughes Oliphant (2002). Worship: Reformed According to Scripture. Westminster John Knox Press. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-664-22579-7.

Within a few years the Reformed church calendar was fairly well established. The heart of it was the weekly observance of the resurrection on the Lord's Day. Instead of liturgical seasons being observed, "the five evangelical feast days" were observed: Christmas, Good Friday, Easter, Ascension, and Pentecost. They were chosen because they were understood to mark the essential stages in the history of salvation.

- ^ Old, Hughes Oliphant (2002). Worship: Reformed According to Scripture. Westminster John Knox Press. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-664-22579-7.

- ^ Carl Philipp Emanuel Nothaft (October 2011). "From Sukkot to Saturnalia: The Attack on Christmas in Sixteenth-Century Chronological Scholarship". Journal of the History of Ideas. 72 (4): 504–505. JSTOR 41337151.

However, when Thomas Mocket, rector of Gilston in Hertfordshire, decried such vices in a pamphlet to justify the parliamentary 'ban' of Christmas, effective since June 1647...

- ^ "Historian Reveals that Cromwellian Christmas Football Rebels Ran Riot" (Press release). University of Warwick. December 17, 2003. Archived from the original on September 28, 2020. Retrieved August 25, 2023.

- ^ Sandys, William (1852). Christmastide: its history, festivities and carols. London: John Russell Smith. pp. 119–120.

- ^ a b "When Christmas carols were banned". BBC. Retrieved March 11, 2022.

- ^ 체임버스, 로버트 (1885). 스코틀랜드 국내 연보, 211쪽.

- ^ "Act dischairging the Yule vacance". The Records of the Parliaments of Scotland to 1707. (in Middle Scots). St Andrews: University of St Andrews and National Archives of Scotland. Archived from the original on May 19, 2012. Retrieved February 29, 2012.

- ^ a b Anon (May 22, 2007). "Bank Holiday Fact File" (PDF). TUC press release. TUC. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 3, 2013. Retrieved January 12, 2010.

- ^ Miall, Anthony & Peter (1978). The Victorian Christmas Book. Dent. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-460-12039-5.

- ^ Woodforde, James (1978). The Diary of a Country Parson 1758–1802. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-281241-4.

- ^ Mather, Cotton (December 25, 1712). Grace defended. A censure on the ungodliness, by which the glorious grace of God, is too commonly abused. A sermon preached on the twenty fifth day of December, 1712. Containing some seasonable admonitions of piety. And concluded, with a brief dissertation on that case, whether the penitent thief on the cross, be an example of one repenting at the last hour, and on such a repentance received unto mercy? (Speech). Boston, Massachusetts: B. Green, for Samuel Gerrish. Retrieved August 12, 2022.

- ^ 스티븐 W. 니센바움, "뉴잉글랜드 초기의 크리스마스, 1620–1820: 청교도주의, 대중문화, 인쇄된 말", 미국 골동품 협회 회보 106:1:79 (1996년 1월 1일)

- ^ Innes, Stephen (1995). Creating the Commonwealth: The Economic Culture of Puritan New England. W.W. Norton & Company. p. 145. ISBN 978-0-393-03584-1.

- ^ Marling, Karal Ann (2000). Merry Christmas!: Celebrating America's Greatest Holiday. Harvard University Press. p. 44. ISBN 978-0-674-00318-7.

- ^ Smith Thomas, Nancy (2007). Moravian Christmas in the South. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-8078-3181-6.

- ^ Andrews, Peter (1975). Christmas in Colonial and Early America. United States: World Book Encyclopedia, Inc. ISBN 978-0-7166-2001-3.

- ^ Christmas in France. World Book Encyclopedia. 1996. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-7166-0876-9.

Carols were altered by substituting names of prominent political leaders for royal characters in the lyrics, such as the Three Kings. Church bells were melted down for their bronze to increase the national treasury, and religious services were banned on Christmas Day. The cake of kings, too, came under attack as a symbol of royalty. It survived, however, for a while with a new name—the cake of equality.

- ^ Mason, Julia (December 21, 2015). "Why Was Christmas Renamed 'Dog Day' During the French Revolution?". HistoryBuff. Archived from the original on November 1, 2016. Retrieved November 18, 2016.

How did people celebrate the Christmas during the French Revolution? In white-knuckled terror behind closed doors. Anti-clericalism reached its apex on 10 November 1793, when a Fête de la Raison was held in honor of the Cult of Reason. Churches across France were renamed "Temples of Reason" and the Notre Dame was "de-baptized" for the occasion. The Commune spared no expense: "The first festival of reason, which took place in Notre Dame, featured a fabricated mountain, with a temple of philosophy at its summit and a script borrowed from an opera libretto. At the sound of Marie-Joseph Chénier's Hymne à la Liberté, two rows of young women, dressed in white, descended the mountain, crossing each other before the 'altar of reason' before ascending once more to greet the goddess of Liberty." As you can probably gather from the above description, 1793 was not a great time to celebrate Christmas in the capital.

- ^ a b c Rowell, Geoffrey (December 1993). "Dickens and the Construction of Christmas". History Today. 43 (12). Archived from the original on December 29, 2016. Retrieved December 28, 2016.

There is no doubt that A Christmas Carol is first and foremost a story concerned with the Christian gospel of liberation by the grace of God, and with incarnational religion which refuses to drive a wedge between the world of spirit and the world of matter. Both the Christmas dinners and the Christmas dinner-carriers are blessed; the cornucopia of Christmas food and feasting reflects both the goodness of creation and the joy of heaven. It is a significant sign of a shift in theological emphasis in the nineteenth century from a stress on the Atonement to a stress on the Incarnation, a stress which found outward and visible form in the sacramentalism of the Oxford Movement, the development of richer and more symbolic forms of worship, the building of neo-Gothic churches, and the revival and increasing centrality of the keeping of Christmas itself as a Christian festival. ... In the course of the century, under the influence of the Oxford Movement's concern for the better observance of Christian festivals, Christmas became more and more prominent. By the later part of the century cathedrals provided special services and musical events, and might have revived ancient special charities for the poor – though we must not forget the problems for large: parish-church cathedrals like Manchester, which on one Christmas Day had no less than eighty couples coming to be married (the signing of the registers lasted until four in the afternoon). The popularity of Dickens' A Christmas Carol played a significant part in the changing consciousness of Christmas and the way in which it was celebrated. The popularity of his public readings of the story is an indication of how much it resonated with the contemporary mood, and contributed to the increasing place of the Christmas celebration in both secular and religious ways that was firmly established by the end of the nineteenth century.

- ^ Ledger, Sally; Furneaux, Holly, eds. (2011). Charles Dickens in Context. Cambridge University Press. p. 178. ISBN 978-0-19-513886-3. Retrieved December 25, 2020.

- ^ Hutton, Ronald (February 15, 2001). The Stations of the Sun: A History of the Ritual Year in Britain. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-157842-7.

- ^ Forbes, Bruce David (October 1, 2008). Christmas: A Candid History. --University of California Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-520-25802-0.

What Dickens did advocate in his story was "the spirit of Christmas". Sociologist James Barnett has described it as Dickens's "Carol Philosophy", which "combined religious and secular attitudes toward to celebration into a humanitarian pattern. It excoriated individual selfishness and extolled the virtues of brotherhood, kindness, and generosity at Christmas. ... Dickens preached that at Christmas men should forget self and think of others, especially the poor and the unfortunate." The message was one that both religious and secular people could endorse.

- ^ Kelly, Richard Michael, ed. (2003). A Christmas Carol. Broadview Press. pp. 9, 12. ISBN 978-1-55111-476-7.

- ^ 코크레인, 로버트슨 Wordplay : 영어의 기원, 의미, 사용법. 토론토 대학 출판부, 1996, p. 126, ISBN 0-8020-7752-8

- ^ Hutton, Ronald, The Station of the Sun: 영국의 의식의 해. 1996. 옥스포드: 옥스포드 대학 출판부, 113쪽. ISBN 0-19-285448-8.

- ^ 조 L. 휠러. 크리스마스 인 마이 하트, 10권 97쪽. 리뷰 및 헤럴드 펍 어소시에이션, 2001. ISBN 0-8280-1622-4.

- ^ Earnshaw, Iris (November 2003). "The History of Christmas Cards". Inverloch Historical Society Inc. Archived from the original on May 26, 2016. Retrieved July 25, 2008.

- ^ 빅토리아 여왕의 소녀기: 여왕 폐하의 일기에서 선택한 것, 61쪽. 1912년 롱맨스, 그린 & Co. 위스콘신 대학교.

- ^ 르준, 마리 클레어 유럽의 상징적이고 의식적인 식물의 개요, p.550. 미시간 대학교 ISBN 90-77135-04-9

- ^ a b 구두장이, 알프레드 루이스. (1959) 펜실베니아의 크리스마스: 민속 문화 연구. 40쪽 52쪽 53쪽 Stackpole Books 1999. ISBN 0-8117-0328-2.

- ^ 1850년, 고디의 부인의 책. 고디는 이 판화를 미국 장면으로 리메이크하기 위해 여왕의 티아라와 앨버트 왕자의 콧수염을 제거한 것을 제외하고는 정확히 복제했습니다.

- ^ Kelly, Richard Michael (ed.) (2003), 크리스마스 캐롤, 20쪽. Broadview Literary Texts, New York: Broadview Press, ISBN 1-55111-476-3.

- ^ 무어의 시는 선물 교환, 가족 잔치, 그리고 "신터클라스" (네덜란드어로 "성 니콜라스"에서 유래한 것으로, 현대의 "산타클로스"에서 유래한 것)의 이야기를 포함하여, 뉴욕에서 새해에 기념되는 진정한 오래된 네덜란드 전통을 크리스마스로 옮겼습니다.크리스마스의 역사: 미국의 크리스마스 역사, 2018년 4월 19일 웨이백 머신(Wayback Machine)에서 보관.

- ^ "미국인들은 다양한 방법으로 크리스마스를 축하합니다." 2006년 12월 10일 웨이백 머신(Wayback Machine, Usinfo.state.gov , 2006년 11월 26일)에 보관되었습니다.

- ^ 워터타운 제1장로회 "오... 그리고 한 가지 더" 2005년 12월 11일, 웨이백 머신에서 보관 2007년 2월 25일

- ^ a b c 레스타드, 펜네 L. (1995), 미국의 크리스마스: 역사, 옥스포드: 옥스퍼드 대학 출판부, 96쪽 ISBN 0-19-510980-5.

- ^ "Christian church of God – history of Christmas". Christianchurchofgod.com. Archived from the original on December 19, 2010. Retrieved February 24, 2011.

- ^ Meggs, Philip B. 그래픽 디자인의 역사. 1998 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 148 ISBN 0-471-29198-6

- ^ Jacob R. Straus (November 16, 2012). "Federal Holidays: Evolution and Current Practices" (PDF). Congressional Research Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 3, 2014. Retrieved January 2, 2014.

- ^ Crossland, David (December 22, 2021). "Truces weren't just for 1914 Christmas". The Times. ISSN 0140-0460. Retrieved December 24, 2021.

- ^ Baxter, Keven (December 24, 2021). "Peace for a day: How soccer brought a brief truce to World War I on Christmas Day 1914". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on December 24, 2021. Retrieved December 24, 2021.

- ^ "The Real Story of the Christmas Truce". Imperial War Museums. Retrieved December 24, 2021.

- ^ "Christmas Truce 1914". BBC School Radio. Retrieved December 24, 2021.

- ^ Weightman, Gavin; Humphries, Steve (1987). Christmas Past. London: Sidgwick and Jackson. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-283-99531-6.

- ^ Harding, Patrick (2003). The Xmas Files: Facts Behind the Myths and Magic of Christmas. London: Metro Publishing.

- ^ "When was the last time football matches in Britain were played on Christmas Day?". The Guardian. Archived from the original on October 6, 2014. Retrieved October 23, 2014.

- ^ Connelly, Mark (2000). Christmas at the Movies: Images of Christmas in American, British and European Cinema. I.B.Tauris. p. 186. ISBN 978-1-86064-397-2.

A chapter on representations of Christmas in Soviet cinema could, in fact be the shortest in this collection: suffice it to say that there were, at least officially, no Christmas celebrations in the atheist socialist state after its foundation in 1917.

- ^ Ramet, Sabrina Petra (November 10, 2005). Religious Policy in the Soviet Union. Cambridge University Press. p. 138. ISBN 978-0-521-02230-9.

The League sallied forth to save the day from this putative religious revival. Antireligioznik obliged with so many articles that it devoted an entire section of its annual index for 1928 to anti-religious training in the schools. More such material followed in 1929, and a flood of it the next year. It recommended what Lenin and others earlier had explicitly condemned—carnivals, farces, and games to intimidate and purge the youth of religious belief. It suggested that pupils campaign against customs associated with Christmas (including Christmas trees) and Easter. Some schools, the League approvingly reported, staged an anti-religious day on the 31st of each month. Not teachers but the League's local set the programme for this special occasion.

- ^ Zugger, Christopher Lawrence (2001). Catholics of the Soviet Empire from Lenin Through Stalin. Syracuse University Press. p. 210. ISBN 978-0-8156-0679-6.