필리핀의 예술

Arts in the Philippines이 문서에는 전체 길이에 비해 그림, 차트 또는 도표가 너무 많습니다.(2022년 1월 (이를에 대해 설명합니다) |

| 의 시리즈의 일부 |

| 필리핀의 문화 |

|---|

|

| 사람 |

| 언어들 |

| 전통 |

| 요리. |

| 축제 |

| 종교 |

| 예체능 |

| 문학. |

필리핀의 예술은 필리핀의 문명이 시작된 이후 현대에 이르기까지 필리핀에서 발전하고 축적된 다양한 형태의 예술을 말합니다.그들은 토착 예술 형식을 포함한 그 나라의 문화에 대한 예술적 영향의 범위와 이러한 영향이 그 나라의 예술을 얼마나 연마했는지 반영한다.이러한 예술은 전통[1] 예술과 비전통 [2]예술이라는 두 가지 뚜렷한 분야로 나뉩니다[by whom?].각 브랜치는 서브카테고리와 함께 다양한 카테고리로 나뉩니다.

개요

필리핀 정부의 공식 문화 기관인 국립 문화 예술 위원회는 필리핀 예술을 전통 예술과 비 전통 예술로 분류했다.각각의 카테고리는 다양한 예술로 나뉘며, 그 예술들은 그들만의 하위 카테고리를 가지고 있다.

- ①전통예술[1]

- 민족 의학 – 알불라리오, 바바일란, 망기힐롯의[3] 예술을 포함하지만 이에 한정되지 않습니다.

- 민속 건축 – 스틸 하우스, 랜드 하우스, 에어 하우스 등(이에 한정되지 않음)

- 해상 운송 – 보트 하우스, 보트 제작 및 해양 전통

- 직조 – 백스트랩 직조 및 기타 관련 직조 형태를 포함하지만 이에 한정되지 않습니다.

- 조각 – 목각 및 민속 비점토 조각 포함(이에 한정되지 않음)

- 민속공연예술 – 춤, 연극, 드라마를 포함하지만 이에 국한되지 않습니다.

- 민속(구전) 문학 – 서사시, 노래, 신화를 포함하지만 이에 국한되지 않습니다.

- 서예, 문신, 민화, 민화, 민화 등 민속 그래픽 및 조형 예술

- 장식 – 마스크 제작, 액세서리 제작, 장식용 금속 공예품 포함(이에 한정되지 않음)

- 섬유 또는 섬유 예술 – 헤드기어 직조, 바스켓, 어구 예술 및 기타 형태의 섬유 또는 섬유 예술 포함(이에 한정되지 않음)

- 도자기 – 도자기 제작, 점토 냄비 제작, 민속 점토 조각 등을 포함하지만 이에 한정되지는 않습니다.

- 전통문화의 기타 예술적 표현 – 비관상 금속공예, 무술, 초자연 치유술, 약술, 별자리 전통 등

- ②비전통예술[2]

- 댄스 – 댄스 안무, 댄스 디렉션, 댄스 퍼포먼스 등

- 음악 – 음악 구성, 음악 방향 및 음악 연주 포함(이에 국한되지 않음)

- 극장 – 연극 연출, 연극 공연, 연극 제작 디자인, 연극 조명 및 음향 디자인, 연극 극본을 포함하지만 이에 국한되지 않습니다.

- 시각 예술 – 회화, 비민속 조각, 판화, 사진, 설치 미술, 혼합 미디어 작품, 일러스트, 그래픽 아트, 퍼포먼스 아트, 이미지 제작 등(이에 한정되지 않음)

- 문학 – 시, 소설, 에세이 및 문학/예술 비평 포함(이에 국한되지 않음)

- 영화 및 방송 예술 – 영화 및 방송 방향, 영화 및 방송 집필, 영화 및 방송 제작 설계, 영화 및 방송 촬영, 영화 및 방송 편집, 영화 및 방송 애니메이션, 영화 및 방송 퍼포먼스, 영화 및 방송 뉴 미디어를 포함하지만 이에 한정되지 않습니다.

- 건축 및 연합 예술 – 민간 건축, 인테리어 디자인, 조경 건축, 도시 디자인을 포함하지만 이에 국한되지 않습니다.

- 디자인 – 산업 디자인 및 패션 디자인을 포함하지만 이에 한정되지 않습니다.

전통 예술

필리핀의 전통 예술은 민속 건축, 해상 운송, 직조, 조각, 민속 공연 예술, 민속 문학, 민속 그래픽과 조형 예술, 장식, 섬유 예술, 도자기, 그리고 전통 [1]문화의 다른 예술적 표현을 포함합니다.전통예술의 다양한 분야에 대한 수많은 필리핀 전문가 또는 전문가들이 있으며, 이들은 GAMABA(Gawad Manilikha ng Bayan)로 선언되어 내셔널 아티스트와 맞먹는다.

민족 의학

민족 의학은 필리핀에서 가장 오래된 전통 예술 중 하나이다.이러한 예술은 바바일란, 망기힐롯, 알불라료에 이르는 의료 장인과 무당들에 의해 행해지는 전통(및 그와 관련된 물건)을 가지고 있다.물리적 요소의 원리에 기반을 둔 그 관행은 원주민들에게 알려진 고대 과학이자 예술이다.정신적, 감정적, 영적 기술로 보완된 한방 치료법 또한 본질적으로 많은 전통의 일부이다.필리핀의 일부 민족 의학 예술에서도 정신 정신적인 관행에 대한 숙달은 두드러진다.민족 의학 부문은 [3]최근 2020년에 GAMABA 부문에 추가되었다.

민속 건축

필리핀의 민속 건축은 민족별로 크게 다르며, 대나무, 나무, 바위, 산호, 등나무, 풀, 그리고 다른 재료로 건축될 수 있다.이러한 악습은 건축에서 지역적인 매체를 사용하는 오두막식 바하이쿠보, 민족적 연관성에 따라 4개에서 8개의 면이 있을 수 있는 고랭지 집, 그 지역의 거친 모래 바람으로부터 원주민들을 보호하는 바타네스의 산호 집, 조각된 왕실의 토로간 등 다양하다.정교하게 만들어진 오키르 문양과 술루 두목의 거처였던 다루잠방안이나 꽃의 궁전 같은 주요 왕국의 궁궐들이 있다.민속 건축은 또한 일반적으로 영혼의 집이라고 불리는 종교적인 건물들을 포함하는데, 이것은 보호 영혼이나 [4][5][6]신을 위한 성지입니다.대부분은 토종 재료로 만들어진 집 같은 건물로, 대개 야외에 [7][4]있다.일부는 원래 탑과 같았고, 나중에 이슬람으로 개종한 원주민들에 의해 계속되었지만, 지금은 매우 [8]희귀해졌다.원주민과 히스패닉을 모티브로 한 건물도 있어 바하이나바토 건축과 그 원형 건축을 형성하고 있다.이 바하이 나 바토 건물들 중 상당수는 비간의 [9]일부로 세계문화유산으로 지정되었다.민속 건축물은 이장과 같은 토속적인 성이나 요새에 세워져 있는 단순한 신성한 막대기 받침대를 포함하며, 지역적으로 [10][11][12]파요라고 불리는 필리핀 코르딜라스의 쌀 테라스와 같은 지형을 바꾸는 예술 작품들을 포함합니다.나가카단, 헝단, 마요야오, 방안, 바타드 [13]등 5개의 논밭 군락이 세계문화유산으로 지정되었다.

몇몇 바하이 나 바토 집들

세계문화유산이자 국가문화재의 일부인 비간의 바하이나바토 가옥

해상운송

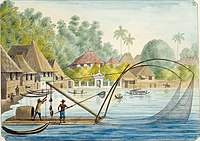

필리핀의 해상 운송에는 보트 하우스, 보트 제작, 그리고 해양 전통이 포함됩니다.이 건물들은 전통적으로 장로들과 공예가들이 선택한 목재로 만들어졌으며, 한 섬을 다른 섬으로 연결하면서 사람들의 주요 이동수단으로 사용되었고, 바다와 강이 사람들의 도로가 되었다.비록 배가 물을 통해 인간이 도착한 이후 수천 년 동안 군도에서 사용되었다고 믿지만, 거대한 발랑게이의 [14]유적으로 확인된 부투안 보트의 탄소 연대 측정을 통해 이 나라에서 배를 만들고 사용한 최초의 증거는 계속해서 서기 320년으로 거슬러 올라갑니다.

외 balangay, 필리핀 전역에서two-masted double-outrigger 보트 등 다양한 스타일과 토착 바다 차량의 종류, armadahan,[15][16]이 무역선 awang,[18]이 큰 항해 outrigger 배는, 널리 알려진 선박 balación,[19]bangka,[20]은 작은 통이 방공호 카누 avang,[17] 있다.oe bangka anak-anak,[21]은Salambáw-lifting basnigan,[22]는 작은 double-outrigger의 요트 bigiw,[23]이 방공호 카누와 지붕이 있는flat-floored casco,[24]단일 마스트 buggoh,[21]고 지목한 쪽배 birau,[21]chinarem,[17]는 거친 바다open-deck 보트 Chinedkeran,[17]이 큰 double-outrigger 널빤지 배 djenging,[21]해적 군함 garay,[25]은 la.Rge 아우트 리거 배 guilalo,[26]항해하는.그 오픈 플로어 구조 보트 카누 junkun,[21]는 작은 발표에 의하면 모터 보트 junkung,[27]이 큰 outrigger 군함은 큰 outrigger 군함 karakoa,[28]lanong,[29]은 선상 가옥 owong,[31일]은open-deck 고기잡이 배에 이중 outrigger 범선은 전쟁 카누 salisipan,[paraw,[32]panineman,[17]그 뗏목은 호수 카누 ontang,[21]lepa,[30]falua,[17].33을 생성하는 방법은 인생의 신조는 tataya,[17]은 소형 어선.많은 [35]다른 것들 중에서, 격앙된 보트 템펠, 칙칙한 티리릿,[34] 그리고 아웃리거 보트 빈타.1565년부터 1815년까지 마닐라 갤리온이라고 불리는 배도 필리핀 [36]장인에 의해 만들어졌다.

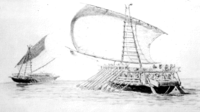

대형 카라코아 현수함, 1711년

발랑가이의 재건

1890년 대형 라농 현수함

카비테 조선소의 필리핀 보트 제작자(1899년)

전쟁 카누 살리시판, 1890년

발라시온 그림, 1847

카스코, 1906년

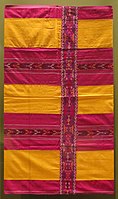

직조

직물은 오늘날 필리핀에서 계속되고 있는 고대 예술 형태이며, 각 민족은 그들만의 독특한 직조 [37]기술을 가지고 있다.짜는 기술은 바구니 짜기, 뒷줄 짜기, 헤드기어 짜기, 어망 짜기, 그리고 다른 형태의 짜기 등으로 구성되어 있다.

천과 매트의 짜임새

값비싼 직물은 뒷줄 [38]메우기라고 불리는 복잡하고 어려운 과정을 통해 만들어진다.면, 아바카, 바나나 섬유, 잔디, 팜 섬유와 같은 섬유는 필리핀 직조 [39]예술에 사용된다.필리핀에는 많은 종류의 직물이 있습니다.피니안은 팡가블란을 사용하여 짠 일로카노 면직물로, 비나쿨, 비네트와간, 티누발리탄 등의 직조 스타일이 입력되어 있습니다.Bontoc 직물은 Bontoc 사람들의 핵심 문화 모티브인 중심성의 개념을 바탕으로 합니다.그것의 짜임새에서, 그 과정은 파익(측면 패널), 파타윌(와프 띠), 그리고 수경(화살표)으로 이동할 때까지 랑킷이라고 불리는 변에서 시작한다.그 후 티나그탁호(인형), 미나트마타(다이아몬드), 티니티코(지그재그)가 혼재된 시나마키 짜기가 시작된다.마지막은 센터 파카와로, 칸에이( ( ()가 특징입니다.칼링가 직물은 기하학에 박혀 있으며, 모티브는 지역적으로 이나타타라고 불리는 연속적인 로젠지 패턴과 파웨칸이라고 불리는 자개 모양의 혈소판 등이다.피냐 원단은 필리핀 원산의 최고급 직물로 여겨진다.아크라논이 만든 것들은 가장 귀중하며, 바롱 타갈로그와 같은 그 나라의 민족 의상에 사용된다.하블론은 사람들의 서사시로 알려진 카레이아족과 힐리가이논족의 훌륭한 직물이다.그 직물은 주로 비사얀 파타동과 파뉴엘로에 사용된다.야칸족의 사푸탄간 태피스트리 직물은 분가사마 보조위직, 시누안 부직, 이날라만 보조위직, 피난투판 위직 등을 이용한 고도의 직물이다.Blaan족의 Mabal tabih는 악어와 곱슬머리를 묘사한다.직물의 여신 후랄로가 바치고 가르치기 때문에 직물 제작자는 여성밖에 할 수 없다.바고보 이나발은 아바카를 이용하여 시누클라와 반디라라는 두 개의 튜브 스커트를 만듭니다.Dagmay는 만다야족의 직조 기술로서 진흙 염색 기술을 사용하고 있습니다.메라노 섬유는 많은 마라나오 의류 중에서 말롱을 만드는데 사용된다.이 공예품들은 꽃봉오리, 다팔 또는 라온(잎), 파코(제비), 파코라봉(양치), 카토라이(꽃) 등 오키르 문양이 배어 있다.Tausug의 피스 샤빗 직물은 직물의 자유로운 상상력을 활용하며, 직물에 미리 정해진 패턴이 없는 것이 하이 아트를 만드는 문화적 기준이다.트날락은 베 [40]짜는 데 사용되는 아바카의 신 푸달루로부터 꿈을 통해 디자인과 무늬를 제공받은 꿈꾼들에 의해 만들어진 트볼리의 훌륭한 직물입니다.동남아시아에서 가장 오래된 워프 이캣 직물은 13세기에서 [41]14세기까지 거슬러 올라가는 롬블론 반튼의 반튼 직물이다.

돗자리 짜기는 직조기와 달리 베틀이나 비슷한 장비를 사용하지 않고 손으로 짜는 데 있어 공예가의 배려에 의존합니다.이 어려운 예술 형식은 필리핀 전역에 알려져 있으며 술루, 바실란, 사마르에서 만들어진 것이 가장 귀중합니다.필리핀의 일반적인 전통에서, 매트 짜기는 매트와 그 섬유의 무결성을 보존하기 위해 그늘지고 시원한 곳에서만 행해진다.한 예로 베짜는 사람들이 주로 동굴 안에서 일하는 베이시의 난간을 들 수 있다.사용되는 섬유는 바나나, 풀, 야자, 그리고 많은 다른 [42]것들로부터 다양합니다.

바스켓리

필리핀의 바구니 짜기의 예술은 수확, 쌀 보관, 여행 패키지, 칼 상자 등 특정 목적을 위한 복잡한 디자인과 형태를 발전시켰다.이 예술은 인간의 이주로 인해 열도에 도착한 것으로 추정되며, 북쪽의 사람들이 이 예술 형태를 가장 먼저 배웠다.하지만 가장 훌륭한 그릇 바구니 공예품들은 남서쪽 팔라완의 민족 집단에서 왔다.팔라완의 바탁은 이 공예품을 하이 아트로 활용했을 뿐만 아니라 기능 예술로서의 지위를 유지하고 있다.마만와족, 네그리토족, 망얀족, 이바탄족 등 많은 사람들 사이에서도 복잡한 바구니를 볼 수 있다.바구니에 사용되는 재료는 민족별로 다릅니다.몇몇 중요한 재료들은 대나무, 등나무, 판단, 면직물 태슬, 니토, 밀랍, 아바카, 부리, 나무껍질, 그리고 염료를 포함합니다.마찬가지로, 각 민족은 다른 많은 것 중에서 직물 위에 닫힌 교차, 닫힌 대나무 이중 트윌, 간격을 둔 등나무 오각형 무늬, 닫힌 사면체 부리 등 그들만의 바구니 무늬를 가지고 있다.필리핀의 많은 바구니 제품들 중 몇 가지는 투필(점심 상자), 부쿠그(바구니), 카빌(운반 바구니), 어피그(점심 바구니), 타가이(밥 바구니), 베이엉(바구니), 리고(바구니), 빙가(봉지)[43][44]를 포함한다.바구니의 짜는 전통은 또한 현대의 [45]수요에 의해 영향을 받아왔다.

이바탄의 바쿠르, 마노보의 머리 천, [46]본톡의 뱀 머리 등 다양한 섬유를 이용해 필리핀 헤드기어를 구성하는 매개체를 연결하는 직조 헤드피스가 필리핀 전역에 널리 퍼져 있다.필리핀의 어획과 기어와 관련된 직조 전통은 광범위하며, 이로카노 사람들은 아마도 군도의 민족 집단 중 가장 다양한 어구를 가지고 있을 것이다.주목할 만한 직조 어획물로는 부보, 베어크벡, 파무라칸 [47]등이 있다.또 다른 직조 전통은 빗자루 짜기인데,[48] 필리핀에서 가장 양식화된 것은 아마도 칼링가족의 석쇠 가공으로 만들어진 탈라가도 빗자루일 것이다.다른 직조 공예품으로는 갈대 우비, 슬리퍼, 그리고 수확, 심기, 사냥, 낚시, 집안일, 여행, 먹이 찾기에 사용되는 물품들이 있다.

조각

바지라얀 유적

필리핀 고고학에는 불교 [49][50]유물의 발견이 있다.Vajrayana의 영향을 받고 있으며,[51][52][better source needed][53] 대부분 9세기 것이다.이 유물들은 뢰르비자얀 제국의 바자야나의 아이콘그래피와 필리핀의 초기 주들에 대한 영향을 반영하고 있다.이 유물들의 뚜렷한 특징은 섬에서의 생산을 나타내며, 이러한 독특한 불교 예술 작품들을 장인들이 만들어냈기 때문에 불교 문화와 문학에 대한 장인의 지식이나 금세공의 지식을 암시합니다.그것들은 또한 이러한 유물들이 발견된 장소에 불교 신자들이 있다는 것을 암시한다.이 장소들은 민다나오 섬의 아구산-수리가오 지역에서 세부, 팔라완, 루손 섬까지 확장되었다.그러므로, 바지랴나의 의식주의는 군도 전체에 널리 퍼졌음에 틀림없다.

- 아구산상은 1917년 민다나오 [54]주 아구산 델 수르 에스페란자 인근 와와 강둑에서 발견된 2kg의 21캐럿 금 조각상이다.이 이미지는 필리핀에서 일반적으로 황금 타라라고 불리며, 불교 타라의 이미지라고 추정되지만 [55]논쟁의 여지가 있는 정체성을 암시합니다.높이가 약 178mm(7.0인치)[56]인 이 인물은 다리를 꼬고 앉아 있고, 화려하게 장식된 머리 장식을 하고 몸의 여러 부분에 다른 장식품들을 착용하고 있는 힌두교 또는 불교의 여성 신이다.그것은 현재 [56]시카고의 필드 자연사 박물관에 전시되어 있다.

- 브론즈 로케스바라 – [57]마닐라 톤도의 Isla Puting Bato에서 발견된 로케스바라 동상입니다.

- 아미타바 석가모니의 부조 – 고대 바탕게뇨는 산스크리트어와 특정 고대 도예에서 대부분의 언어의 기원을 알 수 있듯이 인도의 영향을 받았다.불상이 칼라타간 시의 부조로 점토 메달에 주형으로 복제되었다.전문가들에 따르면, 이 항아리 속의 이미지는 시암, 인도, 네팔에 있는 부처의 우상화와 매우 흡사하다고 한다.항아리에는 타원형의 난봉 안에서 삼방가[58] 안에 있는 아미타바 부처가 포즈를 취하고 있다.석학들은 또한 부처의 관음보살도 [59]묘사되어 있기 때문에 이 이미지에는 강한 마하얀적 성향이 있다고 언급했다.

- 팔라완의 황금 가루다 – 팔라완 섬의 타본 동굴에 있는 또 다른 금 공예품은 비슈누 산의 새인 가루다의 이미지입니다.타본 동굴에서 정교한 힌두교의 이미지와 금 유물이 발견된 것은 베트남 남부의 메콩 삼각주에 있는 Oc Eo에서 발견된 것과 관련이 있다.

- 청동 가네샤 조각상 – 1921년 헨리 오틀리 베이어가 푸에르토 프린세사와 세부 막탄에 있는 고대 유적지에서 힌두교 신 가네샤의 조청동상을 발견했습니다.조청동상은 그 지역의 재현을 [57]보여준다.

- 막탄 알로키테스바라 – 1921년 H.O.에 의해 세부 막탄에서 발굴되었습니다.Beyer, 그 조각상은 청동이고 "순수한 불교"[57]가 아닌 시바불교 혼합일 수 있습니다.

- 골든[60][61] 타라

- 골든 킨나리 - 수리가오 출신.

- 파드마파니와 난디상 – 파드마파니는 자비로운 지혜의 존재 또는 보살인 관세음보살의 현상으로도 알려져 있다.지금까지 발견된 황금 장신구에는 반지, 일부는 난디상(성스러운 황소, 연결된 쇠사슬, 새겨진 금박, 힌두교 [62][63]신들의 화려한 이미지로 장식된 금반지)이 있다.

애니미스트 유물

필리핀의 조각 예술은 목각과 민속 비점토 [64][65]조각에 초점을 맞추고 있다.

목각

토착 목각은 필리핀에서 가장 주목할 만한 전통 예술 중 하나이며, 히스패닉이 도착하기 이전의 다양한 민족들의 공예품들이 있고, 아마도 현존하는 가장 오래된 것은 서기 [66]320년의 나무 배의 파편일 것이다.많은 사회는 신성한 불상 [67][68]같은 목공예품을 만들기 위해 다양한 나무를 이용한다.다른 속칭으로 다양한 그룹으로 알려진 이 신목상들은 북부 루손에서 남부 민다나오에 [69]이르는 필리핀 전역에 많이 있다.나무 위의 오키르 예술은 민다나오 군도와 술루 [70][71]군도의 다양한 민족에 기인하는 또 다른 훌륭한 공예품이다.칼자루, 악기, 기타 물건과 같은 특정한 물건의 목공예품도 눈에 띄는데, 여기에는 주로 고대 신화적인 존재에 대한 묘사가 [72][73]새겨져 있다.필리핀에는 다른 토착 목공예와 기술이 있는데, 그 중 일부는 파테의 [74][75]목각 양식과 같이 식민지화 이후 히스패닉 목각화에 사용되었다.

필리핀에는 기독교의 전래와 함께 히스패닉계 목각화가 풍부해졌다.이 기술은 토착과 히스패닉 양식으로 융합되어 히스패닉-아시아 목재 예술이 융합되었다.파에테, 라구나는 이 나라에서 가장 유명한 목각지 중 하나이며, 특히 종교적인 히스패닉 [74]목각지에 있습니다.히스패닉 전통에서 목각의 다양한 서사시들이 또한 많은 자치구에 존재하는데, 대부분의 공예품들은 마리아 전통이 [76]널리 퍼져있는 그리스도와 성모 마리아의 삶에 기인한다.

돌, 상아 및 기타 조각품

석각은 서양 식민지 개척자들이 도착하기 이전부터 필리핀에서 귀하게 여겨졌던 예술 형태인데,[77] 이는 원주민들의 석재 리카, 라라우안 또는 타오타오 공예품에서 볼 수 있다.이 물건들은 보통 사랑하는 사람의 영혼이 저승으로 [78]갈 수 있도록 도와주는 조상이나 신을 상징한다.코타바토 [79]지방을 중심으로 많은 지역에서 고대의 조각된 매장 항아리가 발견되었다.캄한티크의 석회암 무덤은 케손 지방에 있는 정교한 무덤으로, 처음에는 석관이었음을 나타내는 암석 덮개를 가지고 있었던 것으로 추정됩니다.이 무덤들은 원래 지붕을 지었을 것으로 추정되는데, 그 위에 구멍이 뚫려 있고 대들보가 [80]놓여져 있습니다.돌무덤 자국도 눈에 띄는데, 타위 주민들과 다른 단체들은 죽은 [81]사람들을 돕기 위해 오키르 문양이 새겨진 자국들을 사용한다.많은 지역에서, 특히 북부 루손의 고지대에서, 산의 측면은 매장 동굴을 형성하기 위해 조각되어 있습니다.카바얀 미라 매장 동굴이 [82]대표적이다.대리석 조각은 특히 롬블론의 진원지에서 유명하다.대리석 공예품의 대부분은 현재 수출용이며, 대부분 불상과 관련 [83]작품들이다.기독교의 도래와 함께 기독교의 석각은 널리 퍼졌다.대부분은 교회의 일부분이었습니다. 예를 들어 정면이나 내부 조각상, 조각상이나 개인 [84]제단을 위한 공예품들이었습니다.교회에 새겨진 주목할 만한 돌 조각은 미아가오 [85]교회의 정면이다.

상아 조각은 필리핀에서 천 년 이상 행해진 예술로, 가장 오래된 상아 유물은 9세기에서 12세기 사이의 [86]부투안 아이보리 옥새로 알려져 있다.상아의 종교적 조각은 아시아 본토에서 필리핀으로 상아가 직접 수입된 이후 널리 퍼져 나갔고, 그곳에서 상아 조각은 마돈나 with Child, Christ Child, 그리고 Sorrowful [87]Mother와 같은 기독교 아이콘에 초점을 맞췄다.필리핀의 많은 상아 조각품들은 금색과 은색 [87]무늬를 가지고 있다.필리핀 상아 무역은 상아 조각에 대한 수요로 붐을 이루었고 21세기까지 [88]계속되었다.최근 몇 년 동안 필리핀 정부는 불법 상아 거래를 단속해 왔다.2013년 필리핀은 세계 최초로 상아재고를 파괴하고 세계 코끼리와 코뿔소 [89]개체 수를 감소시킨 상아 무역에 대한 동지국 간의 결속을 보였다.죽은 카라바의 뿔은 [90]수세기 동안 필리핀에서 상아 대신 사용되어 왔다.

민속 공연 예술

민속 춤, 연극, 그리고 연극이 필리핀의 민속 공연 예술의 대부분을 구성한다.다른 동남아시아 국가들과 마찬가지로, 필리핀의 각 민족은 민속 공연 예술에 대한 그들만의 유산을 가지고 있지만, 필리핀의 민속 공연 예술은 또한 그 나라의 역사적 이야기 때문에 스페인과 미국의 영향을 포함한다.몇몇 춤들은 또한 이웃한 오스트로네시아와 다른 아시아 국가들의 [91]춤과 관련이 있다.민속공연예술의 주목할 만한 예로는 방가, 만녹, 라그락사칸, 타렉텍, 우야우이,[92] 판갈레이, 아식, 싱킬, 사가얀, 카파말롱,[93] 비나일란, 수고드우노, 두고, 키누그식 쿠그식, 시링, 파그디와타, 카리와타, 카리클링, 카리, 타렉이 있다.다양한 민속극과 연극이 사람들의 많은 서사시에 알려져 있다.비히스패닉 전통 중에는 히닐라우드나[98] 이발롱과[99] 같은 서사시를 다룬 드라마가 알려져 있으며, 히스패닉계에서는 세나쿨로가 주목할 [100][101]만한 드라마이다.

싱킬 궁중무용

민속 문학

민속(구전) 문학의 예술에는 필리핀의 수많은 민족들의 서사시, 노래, 신화 및 기타 구전 문학이 포함됩니다.

필리핀의 시 예술은 형식이 높고 [102]은유로 가득하다고 여겨져 왔다.타나가 시는 7777음절로 구성되어 있지만, 운율은 이중 운율 형식에서 프리스타일 [102]형식까지 다양합니다.아윗시는 파바사를 [105]통해 외치는 파선 [103][104]등 기성 서사시들의 운율을 따라 12음절의 쿼트레인으로 구성되어 있다.주목할 만한 서사시는 [106]로라의 1838 플로란테이다.달릿 시는 각각 [107]8음절로 된 4행으로 구성되어 있다.암바한 시는 운율적인 끝 음절이 있는 7음절로 구성되어 있으며, 종종 정해진 음조나 악기 반주 없이 우화적인 방식으로 표현되며, 시를 낭송하는 사람이 언급한 시적 언어, 특정한 상황 또는 특정한 특징을 자유롭게 사용하여 표현한다.대나무에도 쓰여져 있습니다.[108]필리핀에서 주목할 만한 시 결투는 발라그타산인데,[109] 이것은 시로 이루어진 논쟁이다.주목할 만한 시로는 A la juventud filipina,[110] Ako'may [111]alaga, Kay Selya 등이 [112]있다.

유명한 서사시로는 마라나오[113] 섬의 다랑겐과 [114]파나이의 히닐라왓이 있다.필리핀의 다른 서사시로는 일로카노의 비아그니람앙, 비콜라노의 이발론, 후드와 이프가오의 알림, 칼링가의 울랄림 사이클, 가당의 루말린도, 팔라완의 쿠다만, 아구 사이클 등이 있다.투불룰과 트볼리 족의 투불룰을 포함한 많은 사람들.[115] 필리핀 수화는 청각 [116]장애가 있는 필리핀인들에게 구술 문헌을 전달하기 위해 사용되고 있다.

구술 문헌은 사람들의 사고와 삶의 방식을 형성하고, 삶의 여러 측면에서 공동체를 돕는 가치, 전통, 그리고 사회 시스템의 기초를 제공해 왔다.필리핀 민속 문학이 다양한 만큼, 많은 문학 작품들은 계속해서 발전하고 있으며, 일부는 학자들에 의해 기록되고 있고 원고, 테이프, 비디오 기록 또는 다른 다큐멘터리 [117][118]형식으로 입력된다.

시노산(1919년)에 설명된 점괘도에서 비사야와 비콜의 신 바쿠나와

민담에 나오는 마나낭갈 그림

민담에 나오는 부라크 조각

이푸가오의 경계를 지키는 신의 호강, 양치나무 조각상

카아물란에서 고대 종교의 신과 영웅을 그린 공연

민속 그래픽 및 조형 예술

민화, 조형예술 분야는 문신, 민화, 민화 등이다.

민속문헌(칼리그래피)

필리핀에는 수얏이라고 불리는 많은 토착 문자들이 있는데, 각각의 문자는 그들만의 서예 형태와 스타일을 가지고 있다.16세기 스페인 식민지 이전부터 독립 시기인 21세기까지 필리핀의 다양한 민족언어 집단은 문자를 다양한 매개체로 사용해 왔다.식민주의의 말기에 이르러, 오직 4개의 수얏 문자만이 살아남아 일상생활에서 특정 공동체에서 계속 사용되고 있다.이들 4개의 문자는 하누노 망얀족의 하누노/하누누누, 부히드 망얀족의 부히드/빌드, 타그반와족의 타그반와 문자, 팔라완족의 팔라완 문자이다.이 네 개의 스크립트 모두 [119]1999년에 필리핀 고문서(하누누, 부이드, 타그바누아, 팔라완)라는 이름으로 유네스코 세계기록유산에 등재되었다.

식민주의에 대한 반대 때문에 많은 예술가들과 문화 전문가들은 스페인의 박해로 인해 멸종된 수야트 문자의 사용을 부활시켰다.부활하는 문자에는 다양한 비사야 민족의 바드라이트 문자, 에스카야족의 이니스카야 문자, 타갈로그족의 바이바인 문자, 삼발족의 삼발리 문자, 비콜라노족의 바사한 문자, 팡가시넨스족의 술라트 판가시난 문자, 쿠르디타 문자 등이 있다.f Illocano 사람들, 다른 [120][121][122][123][124]많은 사람들 중에서.필리핀의 [125][126][127][129][130]고유 수야트 서예 외에도 필리핀의[128] 특정 커뮤니티나 예술단체에서 스페인에서 유래한 서예나 아랍어 서예인 죠이, 키림이 사용되고 있다.지난 10년 동안, 수야트 대본을 기반으로 한 서예는 인기 급상승과 [131][132]부활을 맞이했다.필리핀 점자는 [133]시각장애인이 사용하는 문자다.

바사한 (수라트 비콜) 스크립트 샘플

Buhid 스크립트샘플

기림문자로 쓰인 바양의 코란은 국가 문화보물로 이슬람 민다나오 본토에서 사용되고 있다.

스페인어로 된 초기 기독교 서적, 라틴 문자로 된 타갈로그어 및 베이바인(1593년)의 페이지

민화와 회화

민화는 군도에서 수천 년 동안 알려져 왔다.가장 오래된 민화는 기원전 6000년부터 2000년까지 필리핀 신석기 시대에 만들어진 앙고노(리잘) 암각화를 포함한 암각화와 판화이다.이 그림들은 본질적으로 종교적인 것으로 해석되어 왔으며,[134] 유아 그림들은 아이들의 병을 완화하기 위해 만들어졌다.또 다른 알려진 암각화는 기원전 1500년 이전으로 거슬러 올라가며 푸덴다와 같은 풍요의 상징을 나타낸다.이와는 대조적으로, 고대 민속 그림인 석유그래프는 국내 특정 유적지에서도 찾아볼 수 있다.카가얀에 있는 페냐블랑카의 석유그래프는 숯 그림을 그립니다.팔라완 남부 싱나판의 석유사진도 숯으로 그려졌다.안다(보홀)의 암각화는 붉은 [135]헤마이트로 만든 합성그림이다.몬레알에서 최근에 발견된 석유 사진에는 원숭이, 사람의 얼굴, 벌레 또는 뱀, 식물, 잠자리, [136]새의 그림이 포함되어 있다.

민화는 민화와 마찬가지로 보통 민속 문화를 묘사하는 예술 작품이다.증거에 따르면 군도 사람들은 수천 년 동안 도기에 그림을 그리고 유리를 칠해 왔다고 한다.그림에 사용되는 안료는 금색, 노란색, 붉은 보라색, 녹색, 흰색, 청록색, [137]청록색 등 다양하다.동상이나 다른 창작물들도 다양한 색상으로 다양한 민족에 의해 그려지고 있다.필리핀,[138] 특히 야칸족에서 지속적으로 행해지고 있는 정교한 무늬의 피부 그림도 잘 알려진 민속 예술이다.

문신은 수천 년 전 오스트로네시아의 조상들에 의해 도입되었고, 그곳에서 다양한 민족 [139][140][141]집단에서 문화적 상징으로 발전했다.비록 그 관습이 수천 년 동안 존재해왔지만, 그 문서는 16세기에 처음으로 종이에 기록되었고, 그곳에서 가장 용감한 핀타도스 사람들(비사야 중부와 동부 사람들)이 문신을 가장 많이 새겼다.카마리네스의 비콜라노족과 마린두케의 타갈로그족 사이에 비슷한 문신을 한 민족이 기록되었다.[142][143][144] 민다나오에 문신을 새긴 사람들은 그들의 문신 전통이 [145][146]팡오투브라고 불리는 마노보를 포함한다.티볼리족은 또한 그들의 피부에 문신을 새기는데, 그 문신이 사후세계로 [147]가는 여정에서 영혼을 인도하면서 빛을 낸다고 믿는다.그러나 아마도 필리핀에서 가장 인기 있는 문신은 집단적으로 이고롯이라고 불리는 루손의 고원 민족일 것이다. 그들은 식민지화 이전에 전통적으로 문신을 새겼다.현재는 칼링가 주의 작은 마을인 팅라얀에만 전통 문신 예술가들이 있으며, 문신 거장과 칼링가 모성 황오드가 [148][149]이 바톡을 제작하고 있다.지난 10년 동안, 필리핀의 많은 전통 문신 예술은 수세기 동안 [150]쇠퇴한 후에 부활을 경험했다.필리핀의 [citation needed]특정 민족들 사이에서는 흉터화를 통한 신체 민화 장식도 존재한다.

장식품

장식 예술은 액세서리 제작부터 장식용 금속 공예 등 [1]다양한 분야를 포함한다.

유리 예술

유리 예술은 필리핀의 오래된 예술 형태이며, 피나그바야난과 [151]같은 몇몇 유적지에서 유리로 만들어진 많은 유물들이 발견됩니다.스테인드글라스는 스페인의 점령 이후 이 나라의 많은 교회에서 사용되고 있다.처음에는 유럽 공예가들이 국내에서 스테인드글라스의 생산을 관리했지만, 나중에는 필리핀 공예가들도 등장했는데, [152]특히 20세기부터 그랬다.스테인드글라스 제작의 중요한 세트는 마닐라 대성당에서 온 것으로 포트글라스 기술이 사용되었습니다.마리안 테마는 안경 전체에 걸쳐 생생하게 묘사되어 있으며, 마리아의 삶과 그들의 마리아 경건한 성인에 엄중하게 초점을 맞추고 있습니다.창문에 그려진 주요 성모상에는 평화와 좋은 항해, 기대의 어머니, 위로의 어머니, 로레토의 어머니, 기둥의 어머니, 구제의 어머니, 폐기의 어머니, 카르멜의 어머니, 기적적인 메달, 루르데스의 어머니, 피앙시아의 어머니, 카르멜의 어머니, 기적적인 메달 어머니, 루르데스의 어머니, 피앙의 어머니, 피앙의 어머니 등이 있습니다.필리핀의 일부 유리 예술은 스테인드 글라스 외에도 [154]샹들리에와 조각에 초점을 맞추고 있다.

모자 만들기는 아바와 일로코스의 박을 기반으로 한 타붕가우가 가장 [155]가치 있는 것 중 하나이며, 전국의 많은 공동체에서 예술이다.필리핀 원주민 모자는 20세기 서양식 모자로 대체되기 전까지 사람들의 일상생활에서 널리 사용되었다.그것들은 현재 축제, 의식 또는 [46][156]연극에서와 같은 특정 행사 때 착용된다.

탈을 만드는 기술은 토착적이면서도 수입된 전통인데, 어떤 공동체들은 식민지화 이전에 탈을 만드는 관행을 가지고 있는 반면, 일부 탈을 만드는 전통은 아시아와 서양의 무역을 통해 소개되었다.오늘날, 이 가면들은 주로 축제, 모리오네스 축제, 매스카라 [157][158][159]축제 때 착용한다.이와 관련된 예술은 인형 제작으로, 연극이나 히간테스 [160]축제 등의 축제에서 사용되는 상품으로 유명하다.대부분의 토착 가면은 나무로 만들어지는데, 이 예술 작품들은 인간의 기본적인 이해 밖에 있는 존재들을 나타내기 때문에 거의 항상 초보적인 것이다.사망자를 위해 특별히 제작된 금 가면은 이 나라, 특히 비사야 지역에도 많이 있다.그러나 스페인의 식민지로 인해 금탈을 만드는 관습은 중단되었다.룩반에서 사용되는 대나무와 종이로 만든 가면은 유명한 필리핀 농가를 묘사한다.마린두케의 가면은 판토미믹 극화에 사용되고, 바콜로드의 가면은 평등주의적 가치를 묘사하며, 경제적 기준에 상관없이 고대 민중의 평등한 전통을 보여준다.극장에서는 특히 라마야나 마하바라타와 [161]관련된 서사시 중에서도 다양한 가면이 눈에 띈다.

악세사리 만들기

필리핀에서 액세서리는 거의 항상 각각의 조합의 옷과 함께 착용하며, 일부는 집, 제단, 그리고 다른 물건의 액세서리로 사용된다.필리핀의 100여 개 민족 중 가장 많은 부가적인 [162]민족은 아마도 칼링가족일 것이다.가당족은 또한 매우 액세서리화된 [163]문화를 보여준다.필리핀의 수많은 민족이 사용하는 가장 유명한 장신구는 북부 바타네스 섬부터 남부 팔라완 [164][165]섬까지 사용되는 링고라고 불리는 오메지 모양의 다산물이다.현재 알려진 가장 오래된 링잉오는 기원전 500년으로 거슬러 올라가며 네프라이트 [165]옥으로 만들어졌다.필리핀에서도 전통적으로 조개는 액세서리의 훌륭한 매개체로 사용되어 왔다.[166]

가장 유명한 금세공은 부투안 출신의 필리핀 민족들 사이에서 널리 퍼져 있다.고급 금으로 만들어진 레갈리아, 보석, 의례용 무기, 치아 장식, 그리고 의식적이고 장례적인 물건들이 많은 필리핀 유적지에서 발굴되어 10세기에서 13세기 사이에 군도의 황금 문화가 번성했음을 증명하고 있다.식민지화로 인해 특정 금 공예 기술은 사라졌지만, 다른 문화의 영향을 받은 이후의 기술도 필리핀 [167][168]금세공에 의해 채택되었다.

장식용 금속 공예품

장식용 금속 공예품은 금속으로 만들어질 수도 있고 아닐 수도 있는 다른 무언가를 아름답게 하기 위해 특별히 사용되는 금속 기반의 제품이다.그것들은 필리핀의 많은 커뮤니티에서 귀하게 여겨지는데, 아마도 마라나오족이 만든 것, 특히 투가야, 라나오 델 수르에서 만든 것들이다.모로족의 금속공예는 전통적인 오키르 [169]문양이 배어 있는 다양한 물건을 장식하기 위해 만들어졌다.또한 많은 금속 공예품들이 제단, 기독교 동상, 옷과 같은 종교적인 물건들을 디자인하고 강조하기 위해 사용된다.아팔릿,[170] 팜팡가는 이 비행기의 주요 중심지 중 하나입니다.금은 필리핀의 많은 장식 공예품들에 사용되어 왔으며, 식민주의와 약탈에서 살아남은 대부분은 정교한 고대 [167]문양을 가진 인간 액세서리들이다.

국보급 마나오악의 성모(금속 머리장식을 한 여성)

나부아 교회 레타블로

직물 또는 섬유 예술

섬유 또는 섬유 예술은 필리핀[1] 의류에 지배적인 직물의 디자인을 포함하여 많은 예술적 표현을 포함한다.

도예

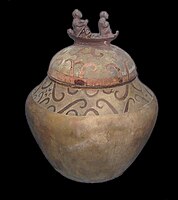

도자기 만들기, 점토 냄비 만들기, 민속 점토 조각으로 분류되는 도자기 예술은 약 3,500년 [171]전의 도자기 문화를 보여주는 증거와 함께 필리핀의 다양한 문화의 일부였다.필리핀의 중요한 도자기 유물로는 만웅굴 항아리 (기원전 890–710)[172]와 미툼 의인화 도자기 (기원전 5-225)[173]가 있다.고온의 도자기는 약 1,000년 전에 처음 만들어졌고,[137] 이로 인해 학자들은 필리핀에서 '세라믹 시대'라고 표현한다.도예품 [137]거래 또한 성행하여, 필리핀에서 아랍 세계, 아마도 이집트, 동아시아까지 도예품과 파편이 발견되었다고 국립문화예술위원회는 밝혔다.특정 항아리도 일본으로 [174]직거래되었다.식민지화 이전에, 섬 전체에서 발견된 많은 고고학적 자기들에서 볼 수 있듯이, 외국에서 수입된 도자기는 군도의 많은 공동체들 사이에서 이미 인기를 끌고 있다.세부에서 온 구전 문학은 자기는 16세기에 [175]식민지 개척자들이 도착하기 전에 세부 초기 통치자들 시대에 이미 원주민들에 의해 생산되었다고 언급했습니다.그럼에도 불구하고 필리핀 고고학 유적지에서 발견된 도자기는 모두 '수입품'으로 낙인이 찍혔기 때문에 필리핀 원주민들이 만든 최초의 도자기는 공식적으로 1900년대로 거슬러 올라가 오늘날 큰 논란이 되고 있다.19세기 후반부터 20세기 초까지 일본에서 도자기 장인으로 일하던 필리핀인들이 필리핀으로 돌아와 공예품을 만드는 과정을 다시 소개했습니다.그 시대의 도자기 한 점을 제외하고는 모두 [176]제2차 세계대전에서 살아남았다.이 나라의 주목할 만한 민속 점토 예술로는 '죽음에 대한 과학의 승리'([177]1890년), '어머니의 복수'([178]1894년) 등이 있으며, 인기 있는 도예품으로는 타파얀과 팔라옥이 있다.필리핀 [179][180]장인에 의해 다양한 기술과 디자인이 지속적으로 제작되고 있기 때문에 도예 예술은 최근 언론의 주목을 받고 있다.

기타 전통문화의 예술적 표현

다양한 전통 예술은 너무 뚜렷해서 구체적인 부문으로 분류할 수 없다.이러한 예술 형태 중에는 비관상 금속 공예, 무술, 초자연 치유술, 약술, 별자리 전통 등이 있다.

비관상 금속 공예품

비관상 금속공예는 자립하는 금속제품이다.이 공예품들은 보통 있는 그대로의 아름다움으로 장식적인 금속 공예품들이 거의 필요하지 않습니다.각 민족은 금속공예에 특화된 장인의 용어를 가지고 있으며, 모로족은 보통 옥기르 [181]모티브로 장식된 고품질 금속공예의 선구자 중 한 명이다.금속공예는 북쪽의 [182]바기오와 같은 나라의 다양한 공예 애호가들의 공예가들 사이에서도 눈에 띈다.히스패닉 금속 공예는 저지대 사람들 사이에 널리 퍼져 있다.이 공예품들은 보통 아시아에서 가장 큰 종들이 파나이 교회에 [183]보존되어 있는 거대한 종들을 포함합니다.필리핀에서도 금속, 특히 금으로 만든 신공예품이 발견되었는데, 아구산 이미지가 주목할 만한 [167][184]예이다.

란타카 건

Ewer from Mindanao (1800)

Detail of a lantaka gun

The largest church bell in Asia, housed at Panay Church, a National Cultural Treasure

Blade arts

The art of sword making is an ancient tradition in the Philippines, where Filipino bladesmiths have been creating quality swords and other bladed weapons for centuries, with a diverse array of types influenced by the sheer diversity of ethnic groups in the archipelago. Many of the swords are specifically made for ceremonial functions and agricultural functions, while certain types are used specifically for offensive and defensive warfare. The most known Filipino sword is the kampilan, a well-defined sharp blade with an aesthetically protruding spikelet along the flat side of the tip and a pommel which depicts one of four sacred creatures, a bakunawa (dragon), a buaya (crocodile), a kalaw (hornbill), or a kakatua (cockatoo).[185] Other Filipino bladed weapons include the balarao, balasiong, balisong, balisword, bangkung, banyal, barong, batangas, bolo, dahong palay, gunong, gayang, golok, kalis, karambit, panabas, pinutí, pirah, gunong, susuwat, tagan, utak. A variety of spears (sibat), axes, darts (bagakay), and arrows (pana/busog) are also utilized by all ethnic groups in the country.[186]

Kampilan sword from Sulu

Kalis sword from Sulu

War, ceremonial, and fishing spears in the Philippines

Various balisongs

Martial arts

Filipino martial arts vary from ethnic group to ethnic group due to the diversity of cultures within the archipelago. The most famous is Arnis (also called kali and eskrima), the national sport and martial art of the Philippines, which emphasize weapon-based fighting styles with sticks, knives, bladed weapons and various improvised weapons as well as open hand techniques. Arnis has met various cultural changes throughout history, where it was also known as estoque, estocada, and garrote during the Spanish occupation. Spanish recorderd first encountered the prevalent martial art as paccalicali-t to the Ibanags, didya/kabaroan) to the Ilocanos, sitbatan/kalirongan to Pangasinenses, sinawali ("to weave") to the Kapampangans, calis/pananandata (use of weapons) to the Tagalogs, pagaradman to the Ilonggos, and kaliradman to the Cebuanos.[187]

Unarmed martial techniques include Pangamot of the Bisaya, suntukan of the Tagalog, Rizal's sikaran of the Tagalog, dumog of the Karay-a, buno of the Igorot people, and yaw-yan. Some impact martial weapons include baston or olisi, bangkaw or tongat, dulo-dulo, and tameng. Edged martial weapons include daga/cuchillo which utilizes gunong, punyal and barung or barong, balisong, karambit which used blades similar to tiger claws, espada which utilizes kampilan, ginunting, pinuti and talibong, itak, kalis which uses poison-bladed daggers known as kris, golok, sibat, sundang, lagaraw, ginunting, and pinunting. Flexible martial weapons include latigo, buntot pagi, lubid, sarong, cadena or tanikala, tabak-toyok. Some projectile martial weapons include pana, sibat, sumpit, bagakay, tirador or pintik/saltik, kana, lantaka, and luthang.[188][189][190] There are also martial arts practiced traditionally in the Philippines and neighboring Austronesian countries as related arts such as kuntaw and silat.[191][full citation needed][192][page needed][193]

Kalasag, shields used in Filipino warfare

Arnis being taught in Australia

Sambal warriors specializing in archery and falconry, recorded in the Boxer Codex

Suntukan sequence

Kuntaw utilized in dance

Statue depicting the sikaran

Jendo[194]

Culinary arts

Filipino cuisine is composed of the cuisines of more than a hundred ethnolinguistic groups found within the Philippine archipelago. The majority of mainstream Filipino dishes that compose Filipino cuisine are from the cuisines of the Bikol, Chavacano, Hiligaynon, Ilocano, Kapampangan, Maranao, Pangasinan, Cebuano (or Bisaya), Tagalog, and Waray ethnolinguistic tribes. The style of cooking and the food associated with it have evolved over many centuries from their Austronesian origins to a mixed cuisine of Indian, Chinese, Spanish, and American influences, in line with the major waves of influence that had enriched the cultures of the archipelago, as well as others adapted to indigenous ingredients and the local palate.[195] Dishes range from the very simple, like a meal of fried salted fish and rice, to the complex paellas and cocidos created for fiestas of Spanish origin. Popular dishes include: lechón[196] (whole roasted pig), longganisa (Philippine sausage), tapa (cured beef), torta (omelette), adobo (chicken or pork braised in garlic, vinegar, oil and soy sauce, or cooked until dry), kaldereta (meat in tomato sauce stew), mechado (larded beef in soy and tomato sauce), puchero (beef in bananas and tomato sauce), afritada (chicken or pork simmered in tomato sauce with vegetables), kare-kare (oxtail and vegetables cooked in peanut sauce), pinakbet (kabocha squash, eggplant, beans, okra, and tomato stew flavored with shrimp paste), crispy pata (deep-fried pig's leg), hamonado (pork sweetened in pineapple sauce), sinigang (meat or seafood in sour broth), pancit (noodles), and lumpia (fresh or fried spring rolls).[197]

A variety of Filipino food, including kare-kare, pinakbet, dinuguan, and crispy pata

Sisig, usually served in scorching metal plates

Bibingka, a popular Christmas rice cake with salted egg and grated coconut toppings

Halo-halo, a common Filipino dessert or summer snack

Bagnet, crispy pork belly usually partnered with pinakbet and dinardaraan

Chicken adobo on rice

Kaldereta, a stew usually cooked using goat meat

Sinigang, a sour soup with meat and vegetables

Lechon, whole roasted pig, stuffed with spices

Other traditional arts

Shell crafts are prevalent throughout the Philippines due to the vast array of mollusk shells available within the archipelago. The shell industry in the country prioritizes crafts made of capiz shells, which are seen in various products ranging from windows, statues, lamps, and many others.[166] Lantern-making is also a traditional art form in the country. The art began after the introduction of Christianity, and many lanterns (locally called parol) appear in Filipino streets and in front of houses, welcoming the Christmas season, which usually begins in September and ends in January in the Philippines, creating the longest Christmas season of any country in the world. A notable festival celebrating Christmas and lanterns is the Giant Lantern Festival, which exhibits gigantic lanterns crafted by Filipino artisans.[198] The art of pyrotechnics is popular in the country during the New Year celebrations and the days before it during the Christmas season. Since 2010, the Philippines has been hosting the Philippine International Pyromusical Competition, the world's largest pyrotechnic competition, previously called the World Pyro Olympics.[199] Lacquerware is an introduced art form in the Philippines. Although prized, only a few Filipino artisans have ventured into the art form. Filipino researchers are recently studying the possibility of turning coconut oil in lacquer.[200][201][202] Paper arts are prevalent in many communities in the Philippines. Some examples of paper art include the taka papier-mâché of Laguna and the pabalat craft of Bulacan.[203] One form of leaf folding art in the country is the puni, which utilizes palm leaves to create various forms such as birds and insects.[203] Bamboo arts are widespread in the country, with various products being made of bamboo from kitchen utensils, toys, furniture, to musical instruments such as the Las Piñas Bamboo Organ, the world's oldest and only organ made of bamboo.[204] A notable bamboo art is the bulakaykay, which bamboos are intentionally bristled to create elaborate and large arches.[203] Floristry is a fine art that continues to be popular during certain occasions such as festivals, birthdays, and Undas.[205] The art of leaf speech, including its language and its deciphering, is a notable art among the Dumagat people, who use a mixture of leaves to express themselves to others and to send secret messages.[206] The art of shamanism and its related arts such as medicinal and healing arts are found in all ethnic groups throughout the country, with each group having their own unique concepts of shamanism and healing practices. Philippine shamans are regarded as sacred by their respective ethnic groups. The introduction of Abrahamic religions, by way of Islam and Christianity, downgraded many shamanitic traditions, with Spanish and American colonizers demeaning the native faiths during the colonial era. Shamans and their practices continue in certain places in the country, although conversions to Abrahamic faiths continue to interfere with their indigenous life-ways.[207] The art of constellation and cosmic reading and interpretation is a fundamental tradition among all Filipino ethnic groups, as the stars are used to interpret the world's standing for communities to conduct proper farming, fishing, festivities, and other important activities. A notable constellation with varying versions among Filipino ethnic groups include Balatik and Moroporo.[208] Another cosmic reading is the utilization of earthly monuments, such as the Gueday stone calendar of Besao, which the locals use to see the arrival of kasilapet, which signals the end of the current agricultural season and the beginning of the next cycle.[209]

Capiz shell window

A huge lantern during the Giant Lantern Festival

Taka, a type of papier-mâché art in Laguna

Non-traditional arts

The non-traditional arts in the Philippines encompass dance, music, theater, visual arts, literature, film and broadcast arts, architecture and allied arts, and design.[2] There are numerous Filipino specialists or experts on the various fields of non-traditional arts, with those garnering the highest distinctions declared as National Artist, equal to Gawad Manlilika ng Bayan (GAMABA).

Dance

The art of dance under the non-traditional category covers dance choreography, dance direction, and dance performance. Philippine dance is influenced by the folk performing arts of the country, as well as its Hispanic traditions. Many styles also developed due to global influences. Dances of the Igorot dances, such as banga,[92] Moro dances, such as pangalay and singkil,[93] Lumad dances, such as kuntaw and kadal taho and lawin-lawin, Hispanic dances, such as maglalatik and subli, have been inputted into contemporary Filipino dances.[94][95][96][97] Ballet has also become a popular dance form in the Philippines since the early 20th century.[210] Pinoy hip hop music has influenced specific dances in the country, where many have adapted global standards in hip hop and break dances.[211] Many choreographers in the Philippines focus on both traditional and Westernized dances, with certain dance companies focusing on Hispanic and traditional forms of dance.[212][213]

Dancers during the Sinulog Festival

Music

Musical composition, musical direction, and musical performance are the core of the art of music under the non-traditional category. The basis of Filipino music is the vast musical tangible and intangible heritage of the many ethnic groups in the archipelago, where some of which have been influenced by other Asian and Western cultures, notably Hispanic and American music. Philippine folk music includes the chanting of epic poetry, such as the Darangen and Hudhud ni Aliguyon, and singing of folk music traditions through various means such as the Harana. Some Filipino music genre include Manila sound which brought hopeful themes amidst the decaying status of the country during the martial law years,[214] Pinoy reggae which focuses on dancehall music faithful to the expressions of Jamaican reggae,[215] Pinoy rock which encompasses rock music with Filipino cultural sensibilities,[216] Pinoy pop which is one of the most popular genre in the country,[217] Tagonggo which is music traditionally played by finely-dressed male musicians,[218] Kapanirong which is a serenade genre,[219] Kulintang which is a genre of an entire ensemble of musicians utilizing a diverse array of traditional musical instruments,[220] Kundiman which is a traditional genre of Filipino love music,[221] Bisrock which is a genre of Sebwano rock music,[222] and Pinoy hip hop which is genre of hip hop adopted from American hip hop music.

Depiction of harana

Theater

Theater has a long history in the Philippines. The basis of which is the folk performing arts under the traditional arts. In the non-traditional category, theatrical direction, theatrical performance, theatrical production design, theatrical light and sound design, and theatrical playwriting are the focal arts. Theater in the Philippines is Austronesian in character, which is seen in rituals, mimetic dances, and mimetic customs of the people. Plays with Spanish influences have affected Filipino theater and drama, notably the komedya, the sinakulo, the playlets, the sarswela, and the Filipino drama. Puppetry, such as carrillo, is also a notable theater art.[223] In contrast, theater with Anglo-American influence have also mixed with various art forms such as bodabil and the plays in English. Modern and original plays by Filipinos have also influenced Philippine theater and drama with the usage of representational and presentational styles drawn from contemporary modern theater and revitalized traditional forms from within or outside the country.[224][225][226]

Promotion for the opera, Sangdugong Panaguinip (1902)

Tanghalang Pambansa (National Theater)

Visual arts

The visual arts under the non-traditional arts include painting, non-folk sculpture, printmaking, photography, installation art, mixed media works, illustration, graphic arts, performance art, and imaging.

Painting

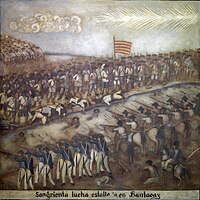

Folk painting has always been part of various cultures in the Philippines.[135][227] Petroglyphs and petrographs are the earliest known folk drawings and paintings in the country, with the oldest made during the Neolithic age.[228] Human figures, frogs, lizards, along with other designs have been depicted. They may have been mostly symbolic representations and are associated with healing and sympathetic magic.[229] The influences brought by other Asian and Western cultures artistically advanced the art of paintings. In the 16th century and throughout the colonization era, paintings of religious propaganda for the spread of Catholicism became rampant. Majority of these paintings are essentially part of church structures, such as ceilings and walls. At the same time, non-religious paintings were also known.[230] Notable painting during the time include the image of Nuestra Senora de la Soledad de Porta Vaga (1692)[231] and paintings at Camarin de da Virgen (1720).[232] In the 19th century, wealthier, educated Filipinos introduced more secular Filipino art, causing art in the Philippines to deviate from religious motifs. The use of watercolour paintings increased and the subject matter of paintings began to include landscapes, Filipino inhabitants, Philippine fashion, and government officials. Portrait paintings featured the painters themselves, Filipino jewelry, and native furniture. Landscape paintings portrayed scenes of average Filipinos partaking in their daily tasks. These paintings often showcased ornately painted artists' names. These paintings were done on canvas, wood, and a variety of metals.[230] Notable watercolor paintings were done in the Tipos del País style[233] or the Letras y figuras style.[234] Notable oil paintings of the 19th century include Basi Revolt paintings (1807), Sacred Art of the Parish Church of Santiago Apostol (1852), Spoliarium (1884), La Bulaqueña (1895), and The Parisian Life (1892).[232] In the American occupation, a notable Filipino painting was The Progress of Medicine in the Philippines (1953).[232] After World War II, painting were heavily influenced by the effects of war. Common themes included battle scenes, destruction, and the suffering of the Filipino people.[235] Nationalistic themes in painting continued amidst the war's effects. Prime examples include International Rice Research Institute (1962) and the Manila Mural (1968)[232] Paintings of the 20th–21st century have showcased the native cultures of the Philippines, as part of the spread of nationalism.[236] Notable paintings during the era include Chickens (1968)[237] and Sarimanok series (late 20th century).[238] Some works have also criticized the lingering colonial viewpoints in the country, such as discrimination against darker-skinned people and the negative effects of colonialism. Notable artistic pieces of this topic are Filipina: A racial identity crisis (1990s),[239][240] and The Brown Man's Burden (2003).[241] Numerous works of art have been made specifically as protest art against state authoritarian rule, human rights violations, and fascism.[242][243][244]

Tampuhan (1895)

Nuestra Señora del Santisimo Rosario (1820–30s)

La vendedora de lanzones (1877)

One of the Sacred Art of the Parish Church of Santiago Apostol paintings (1852), a National Cultural Treasure

One of the Camarín de la Virgen paintings (1720–1725), a National Cultural Treasure

Painting utilizing the Letras y figuras technique (1847)

The Death of Cleopatra (1881)

Las Damas Romanas (1882)

Entrance of the Camarin de la Virgen (1720–1725), a National Cultural Treasure

Our Lady of the Rosary retablo

Sculpture

Non-folk sculpture in the Philippines is a major art form, with many artists and students focusing on the subject.[245] Notable non-folk sculptures include Oblation, which reflects selfless dedication and service to the nation,[citation needed] Rizal Monument, depicting Filipino martyr and scholar José Rizal,[246] Tandang Sora National Shrine, depicting the revolutionary mother of the Katipunan Melchora Aquino,[247] Mactan Shrine, which depicts the classical-era hero Lapulapu who vanquished the colonizers during his lifetime,[248] People Power Monument, which celebrates the power and activism of the people over its government,[249] Filipina Comfort Women, which immortalizes the suffering of and judicial need for Filipina comfort women during World War II,[250] and the Bonifacio Monument, depicting the revolutionary hero Andres Bonifacio.[251][252]

Rizal Monument (1913), a National Cultural Treasure

Bonifacio Monument (1933), a National Cultural Treasure

Other visual arts

Printmaking began in the Philippines after the religious orders at the time, namely Dominicans, Franciscans and Jesuits, started printing prayer books and inexpensive prints of religious images, such as the Virgin Mary, Jesus Christ, or the saints, known as estampas or estampitas, which were used to spread Roman Catholicism and to further colonize the islands. Maps were also printed through the art form, which includes the 1734 Velarde map. Printmaking has since diversified in the country, which has included woodblock printing and other forms.[253] Photography started in the country in the 1840s, upon the introduction of the photographic equipment. Photos were used during the colonial era as mediums for news, tourism, instruments for anthropology and documentation, and as a means for the Spanish and Americans to assert their perceived social status onto the natives to support colonial propaganda.[254] This later changed upon Philippine independence, where photography became widely used by the people for personal documentation and commercial usage.[255] Other forms of visual arts in the Philippines are installation art, mixed media works, illustration, graphic arts, performance art, and imaging.

An original copy of the printed Velarde map, 1734

Malolos Congress photo (1898)

Pre-1863 lithograph photo of Malolos Cathedral

Literature

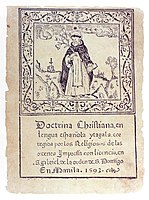

Poetry, fiction, essay, and literary/art criticism are the focal arts of literature under the non-traditional arts, which are usually based on or influenced by the traditional art of folk (oral) literature of the natives, which focuses greatly on works of art from epics, ethnic mythologies, and related stories and traditions. In some cultures, calligraphy on various mediums were utilized to create literary works. An example is the ambahan of the Hanunoo Mangyan.[256] Literature under the colonial regime focused greatly on Spanish-language works under Spanish occupation, then adjusting to the English-language under American occupation. From 1593 to 1800, majority of literary arts made in the Philippines were Spanish-language religious works, with a noble book being Doctrina Christiana (1593)[257] and a Tagalog rendition of the Pasyon (1704).[258] There are also works in the colonial eras that are written in native languages, mostly religious and government scripts for the propagation of colonialism.[254] Nevertheless, Filipino literary works without colonial propaganda were made by local authors as well. At the same time, certain folk (oral) literature were inputted into manuscripts by Filipino writers such as the 17th century manuscript of the ancient Ilocano epic Biag ni Lam-ang.[259] In 1869, the epic Florante at Laura was published, inputting fiction writing with Asian and European themes.[260][unreliable source?][261] In 1878[262] or 1894,[263] the first modern play in any Philippine language, Ang Babai nga Huaran, was written in Hiligaynon. By the 19th century, the formative years of Spanish literature in the country moved forward into what became the nationalist stage of 1883–1903. During this era, the first novel written by a Filipino, Nínay, was published. Works of literary art critical of colonial rulers became known as well, such as the 1887 Noli Me Tángere and the 1891 El filibusterismo.[264] The first novel in Cebuano, Maming, was published in 1900.[265] The so-called golden age of Spanish-language literature in the Philippines began in 1903 to 1966, despite American occupation. During this era, works in native languages and in English started to boom as well. The go-to book of the working class, Banaag at Sikat, was published in 1906, where the literary work dives into the concepts of socialism, capitalism, and the united laborers.[266] The first Filipino book written in English, The Child of Sorrow, was published in 1921. The early writing in English are characterized by melodrama, unreal language, and unsubtle emphasis on local color.[267] The literary content later imbibed themes that express the search for Filipino identity, reconciling the centuries-old Spanish and American influence to the Philippines' archipelagic Asian heritage.[268] From 1966 to 1967, fragments of Sa mga Kuko ng Liwanag were published, and later in 1986, the fragments were inputted into a novel.[269] During the martial law era, prominent literary works tackling the evident human rights violations of those in power were published, such as Dekada '70 (1983)[270] and Luha ng Buwaya (1983).[271][272] Filipino literature in the 21st century dives into historical narratives in modernity, global outlooks, and concepts of equality and nationalism. Major works include Smaller and Smaller Circles (2002),[273] Ladlad (2007),[274] Ilustrado (2008),[275] and Insurrecto (2018).[276]

Doctrina Christiana, 1593

Florante at Laura, originally published in 1869

Noli Me Tángere, 1887

El filibusterismo, 1891

Film and broadcast arts

Film and broadcast arts focuses on the arts of direction, writing, production design, cinematography, editing, animation, performance, and new media.

The origin of the cinematic arts in the Philippines officially began in 1897, upon the introduction of moving pictures into Manila. Filipinos aided foreign filmmakers in the Philippines for a time, until in 1919, when filmmaker José Nepomuceno made the first Filipino film, Dalagang Bukid (Country Maiden).[277] By the 1930s, the formative years of Filipino cinema began as interest in film genre as art began among the common folk. Theatre became an important influence to the boom of cinema in the Philippines. The 1940s created films that would point towards the reality of the people, due to the occupation years during World War II. More artistic and mature films sprang a decade later under the banner of quality films, as perceived at the time.[278][279] The 1960s showed an era of commercialism, fan movies, soft porn films, action flicks, and western spin-offs, until the golden age of cinema met the turbulent years from the 1970s to 1980s due to the dictatorship. The films under the period were overseen by the government, with various filmmakers being arrested. A notable film made during the period is Himala, which tackles the concept of religious fanaticism. The period after martial rule dealt with more serious topics, with independent films being made by many filmmakers. The 1990s saw the emergence of films related to Western films, along with the continued popularity of films focusing on the realities of poverty. Among the direst films at the time include Manila in the Claws of Light, The Flor Contemplacion Story, Oro, Plata, Mata, and Sa Pusod ng Dagat.[279] Cinema in 21st century Philippines has met a revival of popular watchings, with films being produced by various fronts. Films regarding human equality, concepts of poverty, self-love, and historical narratives have met popular success.[280] Key films during the era include The Blossoming of Maximo Oliveros,[281] Caregiver,[282] Kinatay,[283] Thy Womb,[284] That Thing Called Tadhana,[285] The Woman Who Left,[286] and the film version of the book Smaller and Smaller Circles.[287]

Various decaying old Filipino films. Restoration of some films have been undertaken by the ABS-CBN Film Restoration Project

Eden, a former cinema conserved as part of the Malolos Historic Town Center

Architecture and allied arts

Architecture under the category of non-traditional arts focus on non-folk architecture and its allied arts such as interior design, landscape architecture, and urban design.

Non-folk architecture

The basis of Filipino non-folk architecture is the folk architecture of various ethnic groups within the Philippines. The diversity in vernacular architecture range from the bahay kubo, bahay na bato, torogan, idjang, payyo, and ethnic shrines and mosques.[288] Upon the arrival of the Spanish in the 16th century, various Western architectures were introduced such as Baroque, which was used to establish the Manila Cathedral and Boljoon Church. However, due to the geologic nature of the islands, the Baroque architecture was later turned into a unique style now known as Earthquake Baroque, which was used into the building of Binondo Church, Daraga Church, and the World Heritage Sites of Paoay Church, Miagao Church, San Agustin Church, and Santa Maria Church.[85][289][290] Throughout the colonial eras, from Spanish to American rule, various architecture styles were introduced. A notable Gothic Revival building is the San Sebastian Church, the only all-steel church in Asia. Beaux-Arts became popular among the wealthy classes. A notable example is the Lopez Heritage House.[288] Art Deco continues to be a popular architecture in certain Filipino communities, with the city of Sariaya considered as the country's Art Deco capital.[291] Italian and Italian-Spanish architecture can be seen on certain buildings such as Fort Santiago and The Ruins. Stick-style is notable among some wood buildings such as the Silliman Hall. Neoclassical is perhaps the most vividly depicted in the Philippines, as many government buildings follow the architecture. Examples include the Baguio Cathedral, Manila Central Post Office, and the National Museum of Fine Arts. Even after independence, architecture continued to evolve, with the usage of Brutalist architecture during the martial law era. After the restoration of democracy, a revival of indigenous architecture into neo-vernacular architecture occurred in the late 20th century and the 21st century. These buildings and structures have become iconic bases for Filipino nationalism and ethnic representation. Modern-style architecture is presently a popular style in the Philippines, with some examples include the Saint Andrew the Apostle Church and the Manila Hotel.[288] In the present era, demolitions of culturally important buildings and structures have happened, despite the enactment of laws disallowing such acts. Many cultural workers and architects have made advances to stop the demolitions of certain buildings and structures.[292]

Baroque Manila Cathedral (c. 1571, rebuilt 1954)

Earthquake baroque Paoay Church (c. 1694), World Heritage Site and a National Cultural Treasure

Gothic revival San Sebastian Church (c. 1891), a National Cultural Treasure

Baroque Boljoon Church (c. 1783), a National Cultural Treasure

Fort Santiago (c. 1593), a National Cultural Treasure

Earthquake baroque Belfry of Santa Maria Church (c. 1810), World Heritage Site and a National Cultural Treasure

Neo-vernacular Cotabato City Hall (20th century)

Italian-style The Ruins (mansion) (c. 1990s)

Neoclassical, Beaux-Arts Jones Bridge (c. 1919, rebuilt 1946)

Baroque Tayum Church (1803), a National Cultural Treasure

Renaissance revival University of Santo Tomas Main Building (1927), a National Cultural Treasure

Malagonlong Bridge (1841), a National Cultural Treasure

Baroque Dupax Church (1776), a National Cultural Treasure

Baroque Tumauini Church (1805), a National Cultural Treasure

Baroque San Joaquin Campo Santo (1892), a National Cultural Treasure

Panglao Watchtower, a National Cultural Treasure

Fortress-style Capul Church (1781), a National Cultural Treasure

Barn-style Jasaan Church (1887), a National Cultural Treasure

Moorish-style Sulu Provincial Capitol building

Truss-style San Juanico Bridge (1973)

Neoclassical Manila Central Post Office (1928)

Gabaldon-style Negros Occidental High School (1927)

Loon Church (1864)

Palo Cathedral (1596)

Above-ground walls of the Nagcarlan Underground Cemetery

Manila City Hall Clock-tower

Buddhist Seng Guan Temple (20th century)

Barracks at Corregidor

Bastion-style Baluarte de San Diego (1587)

Baroque Tuguegarao Cathedral (1768)

Churrigueresque Baroque Daraga Church (1773)

Baroque-neoclassical Lazi Church (1857)

Dapitan Church (1871)

Mexican Baroque Quiapo Church bell tower (1984)

Architecturally allied arts

The allied arts of architecture include interior design, landscape architecture, and urban design. Interior design in the Philippines has been influenced by indigenous Filipino interiors and cultures, Hispanic styles, American styles, Japanese styles, modern design, avant-garde, tropical design, neo-vernacular, international style, and sustainable design. As interior spaces are expressions of culture, values, and aspirations, they have been heavily researched on by Filipino scholars.[293] Common interior design styles in the country for decades have been Tropical, Filipino, Japanese, Mediterranean, Chinese, Moorish, Victorian, and Baroque, while Avant Garde Industrial, Tech and Trendy, Metallic Glam, Rustic Luxe, Eclectic Elegance, Organic Opulence, Design Deconstructed, and Funk Art have recently become popular.[294] Landscape architecture in the Philippines initially followed the client's opulence, however, in recent years, the emphasis has been on the ecosystem and sustainability.[295] Urban planning is a key economic and cultural issue in the Philippines, notably due to the high population of the country, marked with problems on infrastructures such as transportation. Many urban planners have initiated proposals for the uplifting of urban areas, especially in congested and flood-prone Metro Manila.[296][297]

Interior of Betis Church, a National Cultural Treasure

Interior of San Sebastian Church, a National Cultural Treasure

Interior of San Agustin Church, a National Cultural Treasure

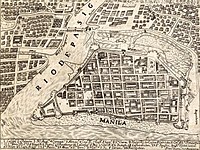

Urban design for Intramuros, 1734

Balay Negrense interior

Pelaez Ancestral House interior

Dapitan Church interior

Wright Park in front of the Baguio Mansion

Dapitan's Mindanao relief map (c. 1892), a National Cultural Treasure

Casa Manila courtyard

Design

The art of design is present in all forms of art, whether traditional or non-traditional, however, the design arts under the non-traditional arts usually emphasize industrial design and fashion design.

Industrial design

Industrial design, or the art where design precedes manufacture for products intended for mass production,[citation needed] has been a key factor in improving the Philippine economy. Many artistic creations in the country are made through research and development, which interplay with aesthetics that allures customers. Packaging of food and other products, as well as the main aesthetics of certain products such as gadgets, are prime examples of industrial design, along with the aesthetics of mass-produced vehicles, kitchen equipment and utensils, furniture, and many others.[298][299] A major annual event in the Philippines which focuses on industrial design, among others, is Design Week held in the third week of March and October since 2011.[300]

Fashion design

The fashion arts are one of the oldest artistic crafts in the country, with each ethnic group having their own sense of fashion. Indigenous fashion inputs various materials created through the traditional arts, such as weaving and ornamental arts. Unlike industrial design, which is intended for objects and structures, fashion design is intended as a whole bodily package. Filipino fashion is founded on both the indigenous fashion aesthetics of the people, as well as aesthetics introduced by other Asian people and Western people, through trade and colonization. During the last years of the Hispanic era, Ilustrado fashion became prevalent, with majority of the population dressing in Hispanized outfits. This later slowly changed after the importation of American culture.[302] In modern Filipino fashion, budget-friendly choices prevail, although expensive fashion statements are also available, notably for those in a so-called high society.[303] Iconic outfits utilizing indigenous Filipino textiles, without culturally appropriating them, have recently become popular in the country.[304]

Conservation of the Filipino arts

Museums are important vessels for the protection and conservation of Philippine arts. A number of museums in the Philippines possess works of art that have been declared as National Treasures, notably the National Museum of the Philippines in Manila. Other notable museums include Ayala Museum, Negros Museum, Museo Sugbo, Lopez Museum, and Metropolitan Museum of Manila. University museums also hold a vast array of art.[305] Libraries and archives are also important, among the most known are the National Library of the Philippines and the National Archives of the Philippines.[306] Various organizations, groups, and universities have also conserved the arts, especially the performing and craft arts.[306]

Many conservation measures have been undertaken by both private and public institutions and organizations in the country, in addressing the heritage management in the Philippines. The enactment of laws such as the National Cultural Heritage Act have aided in Filipino art conservation. The act also established the country's repository of all culturally-related heritage, the Philippine Registry of Cultural Property.[307] The National Commission for Culture and the Arts is currently the official cultural arm of the Philippine government. There have been proposals to establish a Philippine Department of Culture.[308][309]

See also

- Architecture of the Philippines

- Baroque Churches of the Philippines

- Cinema of the Philippines

- Culture of the Philippines

- Earthquake Baroque

- Filipino cartoon and animation

- Filipino martial arts

- List of Filipino painters

- Literature of the Philippines

- Music of the Philippines

- National Artist of the Philippines

- National Living Treasures Award (Philippines)

- Philippine comics

- Pitoy Moreno

References

- ^ a b c d e "Gawad sa Manlilikha ng Bayan Guidelines". National Commission for Culture and the Arts. Archived from the original on January 18, 2021. Retrieved October 1, 2019.

- ^ a b c Order of National Artist Guidelines Approved on April 27, 2017 (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 29, 2018. Retrieved June 9, 2018.

- ^ a b Pag-iwayan, Jessica (November 2, 2020). "Albularyo, Babaylan, and Manghihilot Are Now Considered National Living Treasures". Manila Bulletin. Retrieved February 4, 2022.

- ^ a b Scott, William Henry (1994). Barangay: Sixteenth-Century Philippine Culture and Society. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press. ISBN 971-550-135-4.

- ^ Kroeber, A. L. (1918). The History of Philippine Civilization as Reflected in Religious Nomenclature. Anthropological Papers of the American Museum of Natural History, Vol. 19, Part 2. New York: Published by Order of the Trustees. pp. 35–37. hdl:2246/286.

- ^ Cole, Fay-Cooper (1922). The Tinguian: Social, Religious, and Economic Life of a Philippine Tribe. Anthropological Series, Vol.14, No. 2. Additional chapter by Albert Gale. Chicago: Field Museum of Natural History. pp. 235–493.

- ^ Gaioni, Dominic T. (1985). "The Tingyans of Northern Philippines and Their Spirit World". Anthropos. 80 (4/6): 381–401. JSTOR 40461052.

- ^ "A Look at Philippine Mosques". ncca.gov.ph. October 6, 2003. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- ^ "Historic City of Vigan". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ Klassen, Winand W. (1986). Architecture in the Philippines: Filipino Building in a Cross-Cultural Context. Cebu City: University of San Carlos.

- ^ Ignacio, Jose F. (n.d.). Heritage Architecture of Batanes Islands in the Philippines: A Survey of Different House Types and Their Evolution (PDF) – via hdm.lth.se.

- ^ Perez, Rodrigo D. III; Encarnacion, Rosario S.; Dacanay, Julian E. (1989). Folk Architecture. Photographs by Joseph R. Fortin and John K. Chua. Quezon City: GCF Books.

- ^ "Rice Terraces of the Philippine Cordilleras". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ Rosario, Ben (November 30, 2015). "Malay Ancestors' 'Balangay' Declared PH's National Boat". Manila Bulletin. Archived from the original on December 8, 2015.

- ^ "Asia". Commercial Fisheries Review. Vol. 30, no. 8–9. August–September 1968. p. 96.

- ^ Roxas-Lim, Aurora. Traditional Boatbuilding and Philippine Maritime Culture (PDF). International Information and Networking Centre for Intangible Cultural Heritage in the Asia-Pacific Region under the auspices of UNESCO (ICHCAP). pp. 219–222. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 10, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f "Traditional Boats in Batanes". International Information and Networking Centre for Intangible Cultural Heritage in the Asia-Pacific Region (ICHCAP). UNESCO. Retrieved October 29, 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Madale, Abdullah T. (1997). The Maranaws: Dwellers of the Lake. Manila: Rex Book Store. p. 82. ISBN 971-23-2174-6.

- ^ Lozano, José Honorato (1847). Vistas de las islas Filipinas y trajes de sus habitantes.

- ^ Abrera, Maria Bernadette L. (2005). "Bangka, Kaluluwa at Katutubong Paniniwala" (PDF). Philippine Social Sciences Review (in Filipino). 57 (1–4): 1–15.

- ^ a b c d e f Nimmo, H. Arlo (1990). "The Boats of the Tawi-Tawi Bajau, Sulu Archipelago, Philippines". Asian Perspectives. 29 (1): 51–88. hdl:10125/16980. S2CID 31792662.

- ^ Kawamura, Gunzo; Bagarinao, Teodora (1980). "Fishing Methods and Gears in Panay Island, Philippines". Memoirs of Faculty of Fisheries Kagoshima University. 29: 81–121.

- ^ "Bigiw-Bugsay: Upholding Traditional Sailing". BusinessMirror. May 6, 2018. Retrieved July 30, 2019.

- ^ Galang, Ricardo E. (1941). "Types of Watercraft in the Philippines". The Philippine Journal of Science. 75 (3): 291–306.

- ^ Warren, James Francis (1985). "The Prahus of the Sulu Zone" (PDF). Brunei Museum Journal. 6: 42–45.

- ^ Roe, E. T.; Hooker, Le Roy; Handford, Thomas W., eds. (1907). The New American Encyclopedic Dictionary. New York: J. A. Hill & Company. p. 484.

- ^ Banagudos, Rey-Luis (December 26, 2018). "Wooden Boatmaking Embraces Mindanao Life, Culture". Philippine News Agency. Retrieved January 11, 2020.

- ^ Argensola, Bartolomé Leonardo de (1711). "The Discovery and Conquest of the Molucco and Philippine Islands". In Stevens, John (ed.). A New Collection of Voyages and Travels, Into Several Parts of the World, None of Them Ever Before Printed in English. p. 61.

- ^ Yule, Henry; Burnell, Arthur Coke (1886). Hobson-Jobson: Being a Glossary of Anglo-Indian Colloquial Words and Phrases and of Kindred Terms Etymological, Historical, Geographical and Discursive. London: John Murray. p. 509.

- ^ Abrera, Maria Bernadette L. (2007). "The Soul Boat and the Boat-Soul: An Inquiry into the Indigenous "Soul"" (PDF). Philippine Social Sciences Review.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Lim, Frinston (November 25, 2016). "Sa Marilag na Lake Sebu Hitik ang Kalikasan, Kultura, Adventure". Inquirer Libre Davao (in Filipino). Retrieved July 23, 2019 – via PressReader.

- ^ Diamond, Isobel (March 26, 2015). "Palawan by Paraw Boat". Travel+Leisure. Archived from the original on December 5, 2018. Retrieved December 5, 2018.

- ^ Warren, James Francis. The Sulu Zone, 1768–1898: The Dynamics of External Trade, Slavery, and Ethnicity in the Transformation of a Southeast Asian Maritime State (2nd ed.). Singapore: NUS Press.

- ^ Deveza, JB R. (February 21, 2010). "National Pride Sails in Ancient Boats". Philippine Daily Inquirer – via PressReader.

- ^ Doran, Edwin (1972). "Wa, Vinta, and Trimaran". The Journal of the Polynesian Society. 81 (2): 144–159. JSTOR 20704848.

- ^ Medillo, Robert Joseph P. (June 19, 2015). "Forgotten History? the Polistas of the Galleon Trade". Rappler. Retrieved February 4, 2022.

- ^ Patterns of Culture (PDF). Retrieved July 24, 2020 – via unesco-ichcap.org.

- ^ Back-strap Weaving (PDF). Retrieved July 24, 2020 – via unesco-ichcap.org.

- ^ Sorilla, Franz IV (May 10, 2017). "Weaving the Threads of Filipino Heritage". Tatler Philippines.

- ^ Ocampo, Ambeth R. (October 19, 2011). "History and Design in Death Blankets". Opinion. Philippine Daily Inquirer.

- ^ Nocheseda, Elmer I. (2016). Rara: Art and Tradition of Mat Weaving in the Philippines. Makati City: The Philippine Textile Council. ISBN 9789719535304.

{{cite book}}: Checkisbn=value: checksum (help) - ^ Pazon, Andy Nestor Ryan; Del Rio, Joana Marie P. (2018). "Materials, Functions and Weaving Patterns of Philippine Indigenous Baskets". Asian Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies. 1 (2): 107–118.

- ^ Yuvuk (PDF). Retrieved July 25, 2020 – via unesco-ichcap.org.

- ^ Smith-Lathouris, Olivana (January 4, 2019). "Thanks to These Filipino Women, Basket Weaving Is Revolutionising Entire Communities". SBS. Retrieved February 4, 2022.

- ^ a b "Salakkot and other headgear" (PDF). www.unesco-ichcap.org. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- ^ "Bubo and other fish traps" (PDF). www.unesco-ichcap.org. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- ^ "Saked brrom-making" (PDF). www.unesco-ichcap.org. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- ^ Peralta, Jesus T. (July–August 1983). "Prehistoric Gold Ornaments From the Central Bank of the Philippines". Arts of Asia. pp. 54–60.

- ^ Zafra, Jessica (April 26, 2008). "Art Exhibit: Philippines' 'Gold of Ancestors'". Newsweek. Retrieved February 6, 2022.

- ^ Legeza, Laszlo (1988). "Tantric Elements in Pre-Hispanic Gold Art". Arts of Asia. Vol. 18, no. 4. pp. 129–133.

- ^ "History of Palawan". Camperspoint. Archived from the original on January 15, 2009. Retrieved December 5, 2018.

- ^ "Early Buddhism in the Philippines". Buddhism in the Philippines. November 8, 2014.

- ^ Francisco, Juan R. (1963). "A Note on the Golden Image of Agusan". Philippine Studies. 11 (3): 390–400. JSTOR 42719871.

It was found in 1917 on the left bank of the Wawa River near Esperanza, Agusan, eastern Mindanao, following a storm and flood

- ^ Francisco, Juan R. (1963). "A Note on the Golden Image of Agusan". Philippine Studies. 11 (3): 390–400. JSTOR 42719871.

The question of its identification is still undecided.

- ^ a b "FMNH 109928". Field Museum. Archived from the original on June 1, 2019.

Statue [figure] is about 178 mm in height (FMNH A109928).

- ^ a b c Churchill, Malcolm H. (1977). "Indian Penetration of Pre-Spanish Philippines: A New Look at the Evidence" (PDF). Asian Studies. 15: 21–45.

- ^ "Tribhanga: Strike A Pose". yet.typepad.com. Archived from the original on January 15, 2009. Retrieved January 6, 2007.

- ^ Francisco, Juan R. (January 1, 1963). "A Buddhist Image from Karitunan Site, Batangas Province" (PDF). Asian Studies: Journal of Critical Perspectives on Asia. University of the Philippines Diliman. 1: 13–22. ISSN 2244-5927.

- ^ Onyot, Ian (March 23, 2012). "Agusan Gold Image Only in the Philippines". MagWrite.info. Archived from the original on June 27, 2012.

- ^ Agusan Image Documents, Agusan-Surigao Historical Archives.

- ^ Bennett, Anna T. N. (2009). "Gold in Early Southeast Asia". ArchéoSciences. 33 (33): 99–107. doi:10.4000/archeosciences.2072.

- ^ Dang, Van Thang; Vu, Quoc Hien (1977). "The Excavation at Giong Ca Vo Site". Journal of Southeast Asian Archaeology. 17: 30–37.

- ^ Caparas, Olympio V.; Lim, Valentine Mariel L.; Vargas, Nestor S. (1992). "Handicrafts and Folkcrafts Industries in the Philippines: Their Socio-Cultural and Economic Context". SPAFA Journal. 2 (1): 22–26.

- ^ Camacho, Leni D.; Gevaña, Dixon T.; Carandang, Antonio P.; Camacho, Sofronio C. (2016). "Indigenous Knowledge and Practices for the Sustainable Management of Ifugao Forests in Cordillera, Philippines". International Journal of Biodiversity Science, Ecosystem Services & Management. 12 (1–2): 5–13. doi:10.1080/21513732.2015.1124453.

- ^ "Butuan Boat". National Museum. Archived from the original on August 4, 2020. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- ^ Buenafe, Mayo (2011). "The Legal Pluralism Phenomenon: Emerging Issues on Protecting and Preserving the Sacred Ifugao Bulul". Nebraska Anthropologist. 26: 127–146.

- ^ Dancel, Manlou M. (1989). "The Ifugao Wooden Idol". SPAFA Digest. Vol. 10, no. 1. pp. 2–5.

- ^ Arcilla, Jose S. (1971). "The Christianization of Davao Oriental: Excerpts from Jesuit Missionary Letters". Philippine Studies. 19 (4): 639–724. JSTOR 42632131.

- ^ Peralta, Jesus T. (1982). "Southwestern Philippine Art". SPAFA Digest. Vol. 3, no. 1. pp. 32–34.

- ^ Benesa, Leonidas V. (1982). Okir: The Epiphany of Philippine Graphic Art. Manila: Interlino Printing Company.

- ^ Barbosa, Artemio C. (1991). "Persisting Traditions of Folk Arts and Handicrafts in the Philippines". SPAFA Journal. 1 (1): 54–60.

- ^ Lasco, Lorenz (2011). "Ang Kosmolohiya at Simbolismo ng mga Sandatang Pilipino: Isang Panimulang Pag-Aaral". Dalumat e-Journal (in Filipino). 2 (1) – via Philippine E-Journals.

- ^ a b Baraoidan, Kimmy (April 28, 2019). "Wood Carving Art Alive in Paete". Inquirer.net.

- ^ Sánchez Gómez, Luis Ángel (2002). "Indigenous Art at the Philippine Exposition of 1887: Arguments for an Ideological and Racial Battle in a Colonial Context". Journal of the History of Collections. 14 (2): 283–294. doi:10.1093/jhc/14.2.283.

- ^ Wood Connections: Creating Spaces and Possibilities for Wood Carvers in the Philippines, CD Habito, AV Mariano, 2014

- ^ National Museum (2010). Annual Report 2010 (PDF) (Report). Archived from the original (PDF) on June 13, 2020.

- ^ https://news.mb.com.ph/2020/01/24/ph-national-museum-receives-valuable-philippine-artifact/.

{{cite news}}: Missing or emptytitle=(help)CS1 maint: url-status (link)[dead link] - ^ Junker, Laura Lee (1999). Raiding, Trading, and Feasting: The Political Economy of Philippine Chiefdoms. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-8248-2035-5.

- ^ "Remains of 1,000-Year Old Village Unearthed in Philippines". Daily News. Associated Press. September 20, 2012.

- ^ Baradas, David B. (1968). "Some Implications of the Okir Motif in Lanao and Sulu Art". Asian Studies. 6 (2): 129–168. S2CID 27892222.

- ^ "Kabayan Mummy Burial Caves". UNESCO World Heritage Centre.

- ^ Torres, Sophia (June 5, 2014). "Romblon: The Country's Marble Capital is also an Island Haven". GMA News Online. Retrieved February 6, 2022.

- ^ Reyes, Raquel A. G. (2019). "Paradise in Stone: Representations of New World Plants and Animals on Spanish Colonial Churches in the Philippines". In Reyes, Raquel A. G. (ed.). Art, Trade, and Cultural Mediation in Asia, 1600–1950. London: Palgrave Pivot. pp. 43–74. doi:10.1057/978-1-137-57237-0_3. ISBN 978-1-137-57236-3. S2CID 192379096.

- ^ a b "Baroque Churches of the Philippines". UNESCO World Heritage Centre.

- ^ "Butuan Ivory Seal". National Museum. Archived from the original on July 26, 2020. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- ^ a b Intramuros Administration. "Rebultong Garing: Religious Images in Ivory". Google Arts & Culture (Photo slideshow).

- ^ Martin, Esmond; Martin, Chryssee; Vigne, Lucy (2011). "The Importance of Ivory in Philippine Culture" (PDF). Pachyderm. 50: 56–67.

- ^ Christy, Bryan (June 19, 2013). "In Global First, Philippines to Destroy its Ivory Stock". National Geographic.

- ^ Madale, Abdullah T. (1997). The Maranaws: Dwellers of the Lake. Manila: Rex Book Store. ISBN 971-23-2174-6.

- ^ Duangwises, Narupon; Skar, Lowell D., eds. (2016). The Folk Performing Arts in ASEAN. Bangkok: Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn Anthropology Centre. ISBN 978-616-7154-36-7 – via Museum Siam Digital Repository.

- ^ a b "Cordillera". seasite.niu.edu. Archived from the original on August 5, 2013. Retrieved August 1, 2013.

- ^ a b "Muslim Mindanao". seasite.niu.edu.

- ^ a b Santos, Monica Fides Amada (2019). "Philippine Folk Dances: A Story of a Nation". Journal of English Studies and Comparative Literature. 18 (1): 1–38.

- ^ a b Snodgrass, Mary Ellen (2016). The Encyclopedia of World Folk Dance. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

- ^ a b CCP Encyclopedia of Philippine Art. Vol. 5: Philippine Dance. Manila: Cultural Center of the Philippines. 1994.

- ^ a b "Hot Spots Filipino Cultural Dance – Singkil". Sinfonia.or.jp. Archived from the original on April 29, 2007. Retrieved February 22, 2015.

- ^ Lolarga, Elizabeth (February 25, 2013). "Filipino Epic 'Labaw Donggon' Comes to Life". Yahoo! News.

- ^ "Photos: Tanghalang Pilipino's 'Ibalong'". Rappler. January 29, 2013.

- ^ Fernandez, D. G. (1977). The Emergence of Modern Drama in the Philippines (1898–1912). Philippine Studies Working Paper No. 1.

- ^ Rogers, Natividad Crame (2005). Classical Forms of Theater in Asia. Manila: University of Santo Tomas Publishing House. ISBN 971-506-341-1.

- ^ a b Noceda, Juan de; San Lucar, Pedro de (1754). Vocabulario de la lengua tagala (in Spanish). Manila: Imprenta de la Compañía de Jesús. pp. 324, 440.

- ^ Gonzalez, N. V. M. (2008). Mindoro and Beyond: Twenty-One Stories. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press. p. 243. ISBN 978-971-542-567-4.

- ^ Smyth, David, ed. (2000). The Canon in Southeast Asian Literatures: Literatures of Burma, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam. Richmond, Surrey: Curzon Press. p. 52. ISBN 0-7007-1090-6.

- ^ Pazzibugan, Dona (April 7, 2009). "'Pabasa' is for Meditating, Not Loud Wailing". Inquirer.net. Archived from the original on November 18, 2011. Retrieved June 30, 2011.

- ^ Herbert, Patricia; Milner, Anthony, eds. (1989). South-East Asia: Languages and Literatures: A Select Guide. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. p. 160. ISBN 0-8248-1267-0.

- ^ Castro, Christi-Anne (2011). Musical Renderings of the Philippine Nation. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-19-974640-8.

- ^ Postma, Antoon (1981). "Introduction to Ambahan". Mangyan Heritage Center. Archived from the original on January 8, 2018. Retrieved October 23, 2017.

- ^ De Leon, Mylah (2013). "The Timeless Art of Balagtasan". Asian Journal.

- ^ Ongsotto, Rebecca Ramilo; Ongsotto, Reena R. (2002). Philippine History Module-Based Learning. Manila: Rex Book Store. p. 124. ISBN 971-23-3449-X.

- ^ Par, Sabrina (2013). Mga Tula at Awit [Poems and Songs] (Slide deck). Retrieved December 25, 2016 – via SlideShare.

- ^ Blanco, John D. (2009). Frontier Constitutions: Christianity and Colonial Empire in the Nineteenth-Century Philippines. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 60. ISBN 978-0-520-25519-7.

- ^ Escueta, Carla Michaela E. (n.d.). "Darangen, the Maranao Epic". ICH Courier Online. Archived from the original on December 26, 2019. Retrieved November 27, 2019.

- ^ Felix Laureano,Recuerdos de Filipinas, Barcelona: 1795, A. Lóopez Robert, impresor, Calle Conde de Asalto (currently called "Carrer Nou de la Rambla"), 63, p. 106.

- ^ Eugenio, Damiana L. (2001). Philippine Folk Literature: The Epics. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press. ISBN 9789715422949.

- ^ Martinez, Liza (December 1, 2012). "Primer on Filipino Sign Language". Opinion. Inquirer.net. Retrieved February 9, 2017.

- ^ Jocano, F. Landa (1969). Outline of Philippine Mythology. Manila: Centro Escolar University Research and Development Center.

- ^ Barrientos, Giselle (April 5, 2019). "The Aswang Project is Working on a Philippine Mythology Reference Book". Scout.

- ^ "Philippine Paleographs (Hanunoo, Buid, Tagbanua and Pala'wan)". UNESCO.

- ^ Villa, Nile (April 27, 2018). "'Educate First': Filipinos React to Baybayin as National Writing System". Rappler.

- ^ "House Panel Approves Baybayin as National Writing System". SunStar. April 24, 2018.

- ^ "5 Things to Know About PH's Pre-Hispanic Writing System". ABS-CBN News. April 25, 2018.

- ^ Marcilla y Martin, Cipriano (1895). Estudio de los antiguos alfabetos Filipinos (in Spanish). Malabon: Tipo-Litografia del Asilo de Huérfanos.

- ^ Morrow, Paul (April 7, 2011). "Baybayin Styles & Their Sources". paulmorrow.ca.

- ^ See, Stanley Baldwin O. (August 15, 2016). "A Primer on Baybayin". GMA News Online. Retrieved February 6, 2022.

- ^ Rosero, Michael Wilson I. (April 26, 2018). "The Baybayin Bill and the Never Ending Search for 'Filipino-ness'". CNN Philippines. Archived from the original on May 5, 2020. Retrieved June 4, 2018.

- ^ Marian (August 12, 2015). "10 Perfectly Awesome Calligraphers You Need to Check Out". Bride and Breakfast.

- ^ Afinidad-Bernardo, Deni Rose M. (June 1, 2018). "Watch: How to Ace in Script Lettering". Philstar Global.

- ^ Abubakar, Carmen A. (2013). "Surat Sug: Jawi Tradition in Southern Philippines". Cuaderno Internacional de Estudios Humanísticos y Literatura. 19: 31–37 – via Dialnet.

- ^ Millie, Julian (2001). "The Poem of Bidasari in the Maranao Language". Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde. 157 (2): 403–406. doi:10.1163/22134379-90003814.

- ^ "The Revival of Baybayin – an Ancient Philippines Script Ripped up by Colonisation". The National. Agence France-Presse. July 31, 2019.

- ^ "Beyond ABCs: Ancient Philippine Script Revival Kicks up Debate". Gulf News. Agence France-Presse. July 31, 2019.

- ^ World Braille Usage (3rd ed.). Watertown, Massachusetts: Perkins. 2013. ISBN 978-0-8444-9564-4. Archived from the original on September 8, 2014.

- ^ "The Angono-Binangonan Petroglyphs". Artes de las Islas Filipinas. Retrieved September 3, 2014.

- ^ a b "Petroglyphs and Petrographs of the Philippines". UNESCO World Heritage Centre.

- ^ Tantiangco, Aya (October 26, 2016). "Officials Call for Protection, Preservation of Newly Discovered Cave Art in Monreal, Masbate". GMA News Online. Retrieved February 6, 2022.

- ^ a b c "The Ceramic Age". National Commission for Culture and the Arts. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- ^ Bramhall, Donna (March 16, 2016). "Meeting the Yakan People in Zamboanga City". Rappler. Archived from the original on March 20, 2016.

- ^ Wilcken, Lane (2010). Filipino Tattoos: Ancient to Modern. Atglen, Pennsylvania: Schiffer Publishing.

- ^ Ragragio, Andrea Malaya M.; Paluga, Myfel D. (2019). "An Ethnography of Pantaron Manobo Tattooing (Pangotoeb): Towards a Heuristic Schema in Understanding Manobo Indigenous Tattoos". Southeast Asian Studies. 8 (2): 259–294. doi:10.20495/seas.8.2_259.

- ^ Demeterio, F. P. A. III (2017). "The Fading Batek: Problematizing the Decline of Traditional Tattoos in the Philippine Cordillera Region". SEARCH: The Journal of the South East Asia Research Centre for Communication and Humanities. 9 (2): 55–82.

- ^ Blair, Emma Helen; Robertson, James Alexander, eds. (1903). The Philippine Islands, 1493–1803. Vol. 2: 1521–1569. Cleveland, Ohio: Arthur H. Clark Company. p. 126 – via Project Gutenberg.

- ^ Steiger, G. Nye; Beyer, H. Otley; Benitez, Conrado (1929). A History of the Orient. Boston: Ginn and Company. pp. 143–144.

- ^ Pangan, John Kingsley (2016). Church of the Far East. Makati City: St. Paul's Philippines. p. 9 – via Archive.org.

- ^ Garvan, John M. (1931). The Manóbos of Mindanáo. Washington: United States Government Printing Office – via University of Michigan Library.

- ^ "Pang-o-Tub: The Tattooing Tradition of the Manobo". GMA News Online. August 28, 2012. Retrieved February 6, 2022.

- ^ Talavera, Jezia; Manalo, Faith; Baybay, Amy; Saludario, Dayra; Dizon, Rosario; Mauro, Bea; Porquerino, Ana; Novela, Ardo; Yakit, France; Banares, Aubrey; Francisco, Marie; Inocencio, Rizzabel; Rongavilla, Conrad; Cruz, Tina (2013). The T'boli: Songs, Stories and Societ.

- ^ Redfern, Corinne (April 19, 2018). "Whang-Od: The Last Tattoo Artist". Tatler.

- ^ Malanes, Maurice (September 10, 2013). "Skin as Archive of History, Culture, Identity". Inquirer.net.

- ^ Lowe, Aya (May 27, 2014). "Reviving Filipino Tribal Tattoo Art". BBC News.

- ^ Cruz, Melodina Sy (2014). "Looking Through the Glass: Analysis of Glass Vessel Shards from Pinagbayanan Site, San Juan, Batangas, Philippines". Hukay: Journal for Archaeological Research in Asia and the Pacific. 19: 24–60.

- ^ Perez, Leila Bernice (January 26, 2014). "A Glass of its Own". Starweek Magazine. Philstar Global.

- ^ Cañete, Reuben (October 11, 2018). "Dissecting the Stained Glass Windows at the Manila Cathedral". BluPrint.

- ^ "Ramon Orlina: A Treasured Philippine Artist". The Manila Times. May 17, 2014.

- ^ Tobias, Maricris Jan (n.d.). "National Living Treasures: Teofilo Garcia". National Commission for Culture and the Arts. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- ^ Nocheseda, Elmer I. (n.d.). "The Filipino and the Salacot". Tagalog Dictionary.

- ^ Morion Head Mask (PDF). Retrieved July 25, 2020 – via unesco-ichcap.org.

- ^ Guadalquiver, Nanette (September 24, 2019). "Bacolod's 40th MassKara Festival to Open Oct. 7". Philippine News Agency.

- ^ Andrade, Nel B. (November 21, 2017). "Be Ready to Get Wet at Fiesta in Angono". Manila Bulletin. Archived from the original on November 21, 2017.

- ^ "The Angono's Higantes Festival for San Clemente". International Information and Networking Centre for Intangible Cultural Heritage in the Asia-Pacific Region. November 17, 2017. Retrieved July 9, 2020.