탈레반

Taliban| 탈레반 | |

|---|---|

| طالبان (ṭālibān) | |

아프가니스탄의 국기로도 사용되는 탈레반의 국기 | |

| 설립자 | |

| 리더스 | |

| 이사회 | 지도부 평의회 |

| 가동일 | |

| 그룹 | 주로 파슈툰족,[1][2] 소수 타지크족 및 우즈벡족[3][4] |

| 본사 | 칸다하르(1994-2001년, 2021년~현재) |

| 활성 지역 | 아프가니스탄 |

| 이데올로기 | |

| 정치적 입장 | 극우파[17] |

| 크기 | 코어 강도 - |

| 연합군 | 서브그룹

|

| 대항마 | 주정부 및 정부간 반대파

|

| 전투와 전쟁 | |

| 테러 단체로 지정됨 | |

| 웹 사이트 | alemarahenglish |

| |

| 시리즈의 일부 |

| 데오반디즘 |

|---|

|

| 이념과 영향 |

| 설립자 및 주요 인물 |

| 주목할 만한 기관 |

| 타블리히자마트의 중심지(마르카즈) |

| 관련 조직 |

| 시리즈의 일부 |

| 이슬람 원리주의 |

|---|

| 저명한 지하드 조직 |

| 아프리카의 지하드주의 |

| 아시아의 지하드주의 |

| 서방의 지하드주의 |

| |

탈레반 (/alisttélbbén, ɑtblbbɑn/; Pashto: ālib roman romanized:, 로마자: āāāāāāāāāā. '학생' 또는 '구원자')는 자신들을 아프가니스탄 [81][82][a]이슬람 에미리트라는 국가 이름으로 부르기도 하는 이슬람 근본주의자이며 이슬람 무장단체이다.미국은 1996년부터 2001년까지 국토의 약 4분의 3을 통치하다가 미국의 침공으로 전복되었다.수년간의 반란 끝에 2021년 8월 15일 카불을 탈환했으며 현재 카불 정부는 어느 나라에도 인정받지 못했지만 카불 전역을 장악하고 있다.탈레반 정부는 여성과 소녀의 노동권과 교육권을 포함한 아프가니스탄의 인권을 제한하고 있다는 비판을 받아왔다.

탈레반은 1994년 아프간 내전에서 주요 파벌 중 하나로 부상했으며 주로 전통적인 이슬람 학교에서 교육을 받은 아프가니스탄 동부와 남부 파슈툰 지역의 학생들로 구성됐다.모하메드 오마르 무자히드(r.1996-2001)의 지도 하에, 이 운동은 무자헤딘 군벌로부터 권력을 옮겨가면서 아프가니스탄의 대부분 지역으로 확산되었다.1996년 이 단체는 아프가니스탄의 약 4분의 3을 통치하고 아프가니스탄의 수도를 카불에서 칸다하르로 이전하면서 아프가니스탄 제1이슬람 에미리트를 설립했다.탈레반 정부는 북부동맹 민병대의 반대에 부딪혔는데, 민병대는 아프가니스탄 북동부 지역을 점령하고 과도 이슬람국가의 계속으로 국제적인 인정을 받았다.탈레반은 2001년 12월 미국이 아프가니스탄을 침공한 후 타도될 때까지 이 나라의 대부분을 장악하고 있었다.그 후, 탈레반은 아프가니스탄 전쟁에서 미국의 지원을 받는 카르자이 행정부와 나토가 이끄는 국제안보지원군(ISAF)과 싸우기 위해 반란을 일으켰다.

탈레반 조직원들에 대한 집단 박해는 조직을 약화시켰고 많은 사람들이 결국 이웃 파키스탄으로 도망쳤다.2002년 5월 망명 회원들은 퀘타 시에 본부를 둔 지도자 평의회(라흐바르슈라)를 결성했다.이들은 곧 카타르에서 세력을 키워 2012년 카타르에 비공식적으로 정치사무소를 설립했다고 한다.히바툴라 아크훈자다의 지도 하에, 2021년 5월, 탈레반은 군사 공격을 시작했고, 곧 아프가니스탄 이슬람 공화국으로부터 여러 지역을 장악했다.2021년 8월 15일 카불 함락 이후 탈레반은 아프가니스탄의 지배권을 되찾고 이슬람 에미리트를 다시 세웠다.

1996년부터 2001년까지 그들의 통치 기간 동안, 탈레반 세력과 광범위하게 아프간 민간인들과 종교와 민족 소수 민족에 대한 차별, 굶주린 민간인들에게 유엔 식량 공급 거부, 문화적 기념물의 파괴, 여성의 피하에에서 금지하는 것에 대한 대량 학살을 위해 비난 받은 이슬람의 엄격한 해석, 또는 이슬람 law,[86]실시했다.hool그리고 대부분의 고용과 대부분의 음악 금지.2021년 권좌에 복귀한 뒤 아프간 정부 예산은 80%를 잃었고 식량 불안이 확산되고 있으며 탈레반 지도자들은 미국과 다른 국가들에 자국의 [87]재정 상태를 인정하라고 촉구했다.탈레반은 여성들이 부르카와 같은 머리부터 발끝까지 가리는 것을 의무화하고, 남성 보호자 없이 여행하는 것을 금지하고, 초등학교 [88][89][90]6학년이 넘은 여성들이 학교에 다니는 것을 금지하는 등 이전 규정에 따라 시행된 많은 정책들로 아프가니스탄을 되돌렸다.

어원학

탈레반이라는 단어는 파슈토어로, '학생'이라는 뜻이며, '알리브'의 복수형이다.This is a loanword from Arabic طالب (ṭālib), using the Pashto plural ending -ān ان.[91] (In Arabic طالبان (ṭālibān) means not 'students' but rather 'two students', as it is a dual form, the Arabic plural being طلاب (ṭullāb)—occasionally causing some confusion to Arabic speakers.)영어 차용어가 된 이후 탈레반은 집단을 가리키는 복수명사 외에 개인을 가리키는 단수명사로도 사용되고 있다.예를 들어 존 워커 린드는 국내 언론에서 '아메리칸 탈리브'가 아니라 '아메리칸 탈레반'으로 불리고 있다.이것은 아프가니스탄에서는 다릅니다.그 그룹의 멤버나 지지자는 탈리브(Talib) 또는 복수의 탈리브(Talib-ha)라고 불립니다.다른 정의에서 탈레반은 '찾는 사람'[92]을 의미한다.

영어에서는 탈레반이 [93][94]철자 Taleban보다 철자법은 탈레반이 우세하다.미국 영어에서, 명확한 조항은 "탈레반"이 아니라 "탈레반"으로 지칭됩니다.파키스탄의 영자 매체에서는 항상 명확한 기사가 [95]빠진다.파키스탄과 인도 영자 매체 모두 이 단체를 "아프간 탈레반"[96][97]이라고 명명하는 경향이 있어 파키스탄 탈레반과 구별된다.게다가 파키스탄에서 탈리반이라는 단어는 한 명 이상의 탈레반 멤버를 지칭할 때 종종 사용된다.

아프가니스탄에서 탈레반은 종종 '탈레반 집단'[98]이라는 뜻의 다리어인 '고로-에-탈레반'으로 불린다.Dari/Persian 문법에 따르면 접두사 "the"는 없습니다.한편, 파슈토어에서는 보통 결정자가 사용되며, 그 결과 파슈토어 문법에 따라 to grammar grammar:: pashdato grammar(Da Talibano) 또는 dadadadadadadadada(Da Talibano)로 불린다.

★★★

1979년 소련이 아프가니스탄을 침공해 점령한 뒤 이슬람 무자헤딘 전사들은 소련군과 전쟁을 벌였다.소련-아프가니스탄 전쟁 동안, 탈레반의 거의 모든 초기 지도자들은 헤즈비이 이슬라미 칼리스나 무자헤딘의 [99]하라카티이 잉킬라브이 이슬라미 파벌을 위해 싸웠다.

파키스탄의 무함마드 지아울 하크 대통령은 소련이 파키스탄 발루치스탄을 침공할 것을 우려하여 소련 점령군에 대항하는 아프간 저항군을 지원하기 위해 아크타르 압두르 라만을 사우디아라비아로 보냈다.잠시 후, 미국 중앙정보국(CIA)과 사우디아라비아 정보총국(GID)은 파키스탄 정보국(ISI)을 통해 자금과 장비를 아프간 무자헤딘에 [100]넘겼다.1980년대 [100]파키스탄 ISI에 의해 모하메드 오마르를 포함한 약 9만 명의 아프간인들이 훈련을 받았다.

1992년 4월, 소련의 지원을 받은 모하마드 나지불라의 집권 체제가 무너진 후, 많은 아프간 정당들은 평화와 권력 공유 협정인 페샤와르 협정에 동의했습니다. 이 협정은 아프가니스탄 이슬람 국가를 설립하고 과도기를 위한 임시 정부를 임명했습니다.굴부딘 헤크마티야르의 헤즈브이 이슬라미 굴부딘, 헤즈베 와흐닷, 이티하드이 이슬라미 등은 불참했다.카불과 아프가니스탄에 [101][better source needed]대한 총체적 권력을 놓고 경쟁하는 경쟁 단체들로 인해 국가는 처음부터 마비되었다.

헤즈마티야르의 헤즈브이 이슬라미 굴부딘당은 과도정부를 인정하지 않고 4월 카불에 잠입해 권력을 장악하면서 내전이 시작됐다.헤크마티아르는 5월에 정부군과 [102]카불에 대한 공격을 시작했다.헤크마티아르는 파키스탄 [103]ISI로부터 운영, 재정 및 군사 지원을 받았다.그 도움으로 헤크마티아르의 군대는 [104]카불의 절반을 파괴할 수 있었다.이란은 압둘 알리 마자리의 헤즈베 와흐닷 군대를 지원했다.사우디는 이티하드이슬람파를 [102][104][105]지지했다.이 민병대들 사이의 갈등은 또한 전쟁으로 확대되었다.

이 갑작스러운 내전 개시로 인해, 새롭게 창설된 아프가니스탄 이슬람 국가에 대한 정부 부처, 경찰 단위 또는 정의와 책임의 체계를 [citation needed]형성할 시간이 없었다.잔학행위는 다른 [citation needed]파벌에 속한 개인들에 의해 저질러졌다.아흐마드 샤 마수드 신임 국방장관, 시브하툴라 모하디 대통령, 부르하누딘 랍바니 대통령(임시정부)이나 국제 적십자위원회(ICRC) 관계자들이 협상한 휴전은 며칠 [102]만에 결렬됐다.마수드 국방장관의 통제하에 있던 북부 아프가니스탄의 시골 지역은 평온한 모습을 보였고 일부 재건 작업이 이루어졌다.이슬람국가(IS)의 동맹인 이스마일 칸이 통치하는 헤라트 시에서도 비교적 [citation needed]평온한 분위기가 연출됐다.한편, 아프가니스탄 남부 지역은 외국의 지원을 받는 민병대나 카불 정부의 통제를 받지 않고 굴 아그하 셰르자이 같은 지역 지도자들과 민병대들에 의해 통치되었다.

★★★

1994

탈레반은 아프가니스탄 동부와 남부 파슈툰 지역에서 전통적인 이슬람 [8]학교에서 교육을 받은 종교 학생(탈리브)들의 운동이다.타지크인과 우즈베키스탄인 학생들도 있었는데, 이들은 "탈레반의 [106]빠른 성장과 성공에 중요한 역할을 한" 보다 민족 중심의 무자헤딘 집단에서 제외되었다.

과

1994년 9월, 물라 모하마드 오마르와 50명의 학생들이 그의 고향 칸다하르에서 [8][107][108]이 단체를 설립했다.1992년부터 오마르는 북부 칸다하르 주 마이완드에 있는 상이히사르 마드라사에서 공부하고 있다.그는 공산주의 통치를 축출한 후 아프가니스탄에 이슬람 율법이 정착되지 않아 기분이 나빴고, 이제 그와 그의 단체는 아프가니스탄에서 군벌과 [8]범죄자들을 제거하겠다고 약속했다.탈레반 결성에 관여한 많은 학생들은 아프가니스탄-소련 [8][9][10][109]전쟁의 전 지휘관이었다.

몇 달 만에 파키스탄의 15,000명의 학생들이 이 단체에 가입했는데, 이들은 대부분 종교 학교나 마드라사(또는 한 소식통들은 이들을 자미아트 울레마이슬람이 운영하는[107] 마드라사라고 부른다.

반소련 폭동을 지원하고 아프가니스탄 어린이들에게 외국 침략자들에 대한 증오를 주입하기 위해 미국 정부는 무장 이슬람의 가르침을 장려하고 무기와 군인의 모습을 담은 교재를 은밀히 배포했다.탈레반은 미국 교과서를 사용했지만 이슬람에 대한 엄격한 비원칙적이고 근본주의적인 해석에 따라 이 교과서에 담긴 인간의 얼굴을 삭제했다.미국 국제개발청은 1980년대에 오마하의 네브래스카 대학에 수백만 달러를 기부했고 그 돈을 현지 언어로 [110]된 교과서를 집필하고 출판하는 데 사용했다.

초기 탈레반은 이슬람의 도덕적 규범을 준수하지 않는 경쟁 아프간 집단이 벌이고 있는 권력 투쟁에 의해 야기된 것으로 믿었던 아프간 사람들의 고통에 의해 동기 부여되었다; 그들의 종교 학교에서는, 그들이 이슬람 [8][9][10]율법을 엄격히 준수해야 한다고 가르침을 받았다.

파키스탄의 개입

소식통에 따르면 파키스탄은 이미 1994년 10월에 [111][112]탈레반의 "창출"에 크게 관여했다고 한다.1994년 탈레반을 강력히 지지했던 파키스탄 정보기관(ISI)은 아프가니스탄에서 파키스탄에 [8]유리한 새로운 집권세력이 생기기를 희망했다.탈레반이 1995년과 1996년 파키스탄으로부터 재정적 지원을 받았다 하더라도 파키스탄의 지원이 탈레반의 존재 초기단계에서 나왔다고 해도 연결고리가 취약해 파키스탄 ISI와 탈레반 양측의 진술은 일찌감치 불편한 관계를 드러냈다.ISI와 파키스탄은 통제력을 발휘하는 것을 목표로 했고, 탈레반 지도부는 독립을 유지하는 것과 지원을 유지하는 것 사이에서 움직였다.파키스탄의 주요 지지자는 지정학적 측면(중앙아시아 교역로 개설)을 주로 생각하는 나세룰라 바바르 장군과 자미트 울레마이슬람(F)의 마울라나 파즐루르 레만(Maulana Fazl-ur-Rehman)으로, "자마트의 데오반디즘을 대표하며 반기를 든 집단"이었다."[113]

칸다하르 정복

1994년 11월 3일 탈레반은 기습적으로 칸다하르 시를 [8]점령했다.1995년 1월 4일 이전에는 아프가니스탄의 12개 [8]주를 지배했다.다른 지역을 장악한 민병대는 종종 싸우지 않고 항복했다.오마르의 지휘관들은 전직 소규모 부대 지휘관들과 마드라사 [114][115][116][117][118]선생님들이 섞여 있었다.이 단계에서, 탈레반은 부패를 척결하고, 무법을 억제하고, 도로와 지역을 안전하게 [8]만들었기 때문에 인기가 있었다.

1995년 ~ 1996년 9월

아프가니스탄 전역을 통치하기 위해 탈레반은 칸다하르 기지를 확장해 넓은 영토를 휩쓸었다.1995년 초 카불로 이동했지만 아흐마드 샤 마수드가 이끄는 아프가니스탄 이슬람국 정부군에 참패했다.카불에서 퇴각하는 동안,[119] 탈레반 전사들은 도시를 포격하기 시작했고, 많은 민간인들을 죽였다.1995년 3월, 탈레반의 포격 이후, 그들은 아프간으로부터 많은 존경을 잃었고, 단지 또 다른 "권력에 굶주린"[120] 민병대로 여겨졌다고 언론은 보도했습니다.

일련의 좌절 끝에 탈레반은 1995년 9월 5일 서부 도시 헤라트를 장악하는데 성공했다.파키스탄이 탈레반을 돕고 있다는 인식된 정부의 주장에 따라,[121] 많은 군중들이 다음 날 카불에 있는 파키스탄 대사관을 공격했다.

1996년 9월 26일 탈레반이 또 다른 대규모 공세를 준비하자 마수드는 카불에서 거리 전투 대신 힌두쿠시 산맥 북동부에서 반 탈레반 저항을 계속하라고 명령했다.탈레반은 1996년 9월 27일 카불에 입성해 아프가니스탄 이슬람 토후국을 설립했다.분석가들은 당시 탈레반이 파키스탄의 지역 [104][116][119][122][123][124]이익을 위한 대리 세력으로 발전하고 있다고 묘사했다.

아프가니스탄 이슬람 토후국(1996-2001)

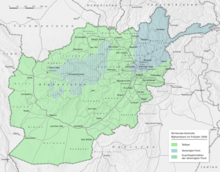

1995년부터 2001년까지 탈레반의 군사적 목표는 북부 지역에서 [125]파슈툰족의 지배권을 가진 국가를 재건함으로써 압두르 라만(철의 에미리트)의 질서를 회복하는 것이었다.탈레반은 하나피 이슬람 법학교와 물라 오마르의 아프간 전 국토에 [86]대한 교령에 따라 샤리아 법에 대한 엄격한 해석과 함께 법과 질서를 통해 이슬람 정부를 세우려 했다.1998년까지 탈레반의 토후국은 아프가니스탄의 90%[8]를 장악했다.

2000년 12월, 결의안 1333호에서 안보리는 아프가니스탄 국민들의 인도주의적 요구를 인식하고, 탈레반이 오사마 빈 라덴에게 안전한 피난처를 제공하는 것을 비난하며, 탈레반의 통제 [126]하에 있는 아프가니스탄에 대해 엄격한 제재를 가했다.2001년 10월 미국은 아프간 북부동맹 등 동맹국들과 함께 아프가니스탄을 침공해 탈레반 세력을 궤멸시켰다.탈레반 지도부는 파키스탄으로 [8]도망쳤다.

탈레반 치하의 아프가니스탄

1996년 탈레반이 정권을 잡았을 때, 20년 동안 계속된 전쟁은 아프가니스탄의 인프라와 경제를 황폐화시켰다.수돗물도 없고, 전기도 거의 없고, 전화도 거의 없고, 제 기능을 하는 도로나 일반 에너지 공급도 없었다.물, 음식, 주택과 같은 기본적인 필수품이 턱없이 부족했다.또 아프간인들에게 사회·경제적 안전망을 제공했던 씨족과 가족 구조도 크게 훼손됐다.아프가니스탄의 유아 사망률은 세계에서 가장 높았다.모든 아이들의 4분의 1이 다섯 번째 생일이 되기 전에 사망했는데, 이는 다른 대부분의 [127][128][129]개발도상국들보다 몇 배 높은 비율이다.

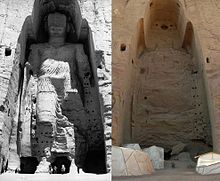

국제 자선단체 및/또는 개발기구(비정부기구 또는 NGO)는 식량, 고용, 재건 및 기타 서비스의 공급에 매우 중요했지만, 탈레반은 그러한 단체가 제공한 '원조'에 대해 매우 의심스럽다는 것이 입증되었다( united 유엔 및 NGO 참조).전쟁 기간 동안 백만 명 이상의 사망자가 발생하면서, 1998년까지 과부가 이끄는 가족의 수는 98,000명에 달했다.도시의 광대한 부분이 로켓 공격으로 초토화된 카불에서는, 120만 인구의 절반 이상이 어떤 식으로든 NGO 활동으로부터 혜택을 받았고, 심지어 물을 마시기 위해서도 혜택을 받았다.내전과 끝없는 난민의 흐름은 탈레반 집권 기간 내내 계속되었다.마자르, 헤라트, 그리고 쇼말리 계곡의 공격은 적에게 [130][131][132]원조를 제공하는 것을 막기 위해 "가벼운 땅" 전술로 민간인 4분의 3 이상을 추방했다.바미얀의 역사적인 불상은 오마르 무자히드의 명령에 [133][134][135][136]의해 파괴되었다.

탈레반의 의사결정권자들, 특히 물라 오마르는 비이슬람 외국인들과 직접 대화한 적이 거의 없기 때문에, 원조 제공자들은 종종 승인과 합의가 [137]번복된 중개자들과 거래해야 했다.1997년 9월경 칸다하르의 3개 유엔기구 수장들은 유엔난민고등판무관 여성 변호사가 [138]얼굴이 보이지 않도록 커튼 뒤에서 이야기를 하도록 강요당하자 항의했다가 추방됐다.

유엔이 탈레반의 요구를 충족시키기 위해 이슬람 여성 직원의 수를 늘리자, 탈레반은 아프가니스탄을 여행하는 모든 이슬람 여성 유엔 직원들을 마흐람이나 [139]혈족에게 보호하도록 요구했습니다.1998년 7월 탈레반은 [140]카불에 있는 모든 비정부기구(NGO) 사무소를 폭탄이 터진 옛 폴리테크닉 칼리지로 옮기는 것을 거부하자 강제 폐쇄했다.한 달 후, 유엔 사무실도 문을 [141]닫았다.식량 가격이 오르고 상황이 악화되자 카리 딘 모하메드 계획장관은 탈레반이 인도적 지원의 손실에 무관심한 태도를 보이고 있다고 설명했다.

우리 이슬람교도들은 전능하신 신이 어떻게든 모두를 먹여살릴 것이라고 믿는다.만약 외국 NGO들이 떠난다면 그것은 그들의 결정이다.우리는 그들을 [142]추방하지 않았다.

칸다하르에서 활동 중인 몇 안 되는 조직들은 같은 요구를 받지 않고 운영을 계속했다.

중

탈레반은 주로 1994년부터 파키스탄의 Inter-Services Intelligence에 의해 창설되었다. I.S.I.는 전략적인 깊이를 얻기 위해 파키스탄에 유리할 수 있는 정권을 아프가니스탄에 설립하기 위해 탈레반을 이용했다.탈레반이 창건된 이후 ISI와 파키스탄군은 재정, 물류, 군사 [158]지원을 해왔다.

파키스탄의 아프가니스탄 전문가 아흐메드 라시드에 따르면, "1994년에서 1999년 사이, 약 8만에서 10만 명의 파키스탄인들이 아프가니스탄에서 훈련하고 싸웠다"고 한다.피터 톰센은 9/11까지 파키스탄 군과 ISI 장교들과 수천 명의 파키스탄 정규군 병력이 아프가니스탄 [159][160]전투에 참여했다고 말했다.

여러 국제 소식통에 따르면 2001년 동안 파키스탄 국민 28,000명에서 30,000명, 아프가니스탄 탈레반 14,000명에서 15,000명, 알카에다 무장세력 2,000명에서 3,000명이 약 45,000명의 강력한 군사력으로 아프가니스탄에서 반 탈레반 세력과 싸웠다.당시 육군 참모총장이었던 페르베즈 무샤라프 파키스탄 대통령은 수천 명의 파키스탄인들을 탈레반과 빈 라덴과 함께 아흐마드 샤 마수드 세력에 대항하기 위해 보낸 책임이 있다.아프가니스탄에서 싸우고 있는 파키스탄 국민 2만8천명 중 8천명은 탈레반의 정규 대열을 채우는 마드라사에서 모집된 무장세력이다.이 문서에는 이들 파키스탄 국민의 부모가 "시체가 파키스탄으로 돌아올 때까지 자녀의 탈레반에 대한 군사 개입에 대해 아무것도 모른다"고 적혀 있다.미 국무부의 1998년 문서는 "탈레반 군인의 20-40%가 파키스탄인"이라고 확인했습니다.국무부의 보고서와 휴먼라이츠워치의 보고서에 따르면 아프가니스탄에서 전투를 벌이고 있는 다른 파키스탄인들은 파키스탄 정규군, 특히 국경군 출신이지만 직접적인 전투 [167]지원을 제공하는 군 출신들이었다.

휴먼라이츠워치를 썼다.

(아프가니스탄에서) 진행 중인 전투를 지속하고 조종하기 위한 노력에 관련된 모든 외세들 중에서, 파키스탄은 목표의 폭과 탈레반에 대한 자금 요청, 탈레반 운영 자금 지원, 탈레반의 실질적인 특사로서 외교적 지원을 제공하는 것을 포함한 노력의 규모에 의해 구별된다.해외에서는 탈레반 전사들을 위한 훈련 준비, 탈레반 군대에서 복무할 숙련 및 비숙련 인력 모집, 공격 계획 및 지휘, 탄약과 연료의 공급 및 촉진, 그리고...[37] 직접 전투 지원 제공.

1997년 8월 1일 탈레반은 압둘 라시드 도스툼의 주요 군사기지인 셰베르간을 공격했다.도스툼은 이번 공격이 성공한 것은 1500명의 파키스탄 특공대원 덕분이며 파키스탄 공군도 [168]지원을 아끼지 않았다고 말했다.

1998년 이란은 파키스탄이 탈레반 세력을 지원하기 위해 마자르이샤리프를 폭격하기 위해 공군을 보냈다고 비난하고 파키스탄군을 "바미얀에서의 전쟁 범죄"로 직접 비난했다.같은 해, 러시아는 파키스탄이 아프가니스탄 북부에서 탈레반의 "군사적 확장"에 책임이 있다고 말했고, 그들 중 일부는 후에 반 탈레반 연합 [169][170]전선에 의해 포로로 잡혔다.

2000년 동안 유엔 안전보장이사회는 탈레반에 대한 군사적 지원에 대해 무기 금수 조치를 취했고, 유엔 관계자들은 파키스탄을 분명히 지목했다.유엔 사무총장은 파키스탄의 군사적 지원을 암묵적으로 비난했고, 안보리는 "수천 명의 비아프간 국민이 탈레반 측 전투에 개입했다는 보도에 대해 깊은 고통을 느끼고 있다"고 밝혔다.2001년 7월, 미국을 포함한 몇몇 국가들은 파키스탄이 "탈레반에 대한 군사적 지원 때문에 유엔 제재를 위반했다"고 비난했다.탈레반은 또한 파키스탄으로부터 재정적인 자원도 확보했다.1997년에만, 탈레반에 의한 카불 점령 이후 파키스탄은 3,000만 달러의 원조와 추가로 1,000만 달러의 정부 임금을 [171][172][173]주었다.

2000년 동안, MI6는 ISI가 몇몇 알카에다 훈련 캠프에서 적극적인 역할을 하고 있다고 보고했다.ISI는 탈레반과 알카에다를 위한 훈련 캠프를 건설하는 것을 도왔다.1996년부터 2001년까지 오사마 빈 라덴과 아이만 알 자와히리의 알카에다는 탈레반 국가 내에 있는 국가가 되었다.빈 라덴은 아랍과 중앙아시아의 알카에다 무장세력을 그의 여단 055와 [174][175][176][177][178]같은 연합전선에 맞서 싸우도록 보냈다.

파키스탄군의 역할은 반(反)탈레반 지도자 아흐마드 샤 마수드뿐 아니라 국제적인 관측통들에 의해 "침략"[159]으로 묘사되었다.

마수드 치하의 반탈레반 저항군

1996년 말 적이었던 아흐마드 샤 마수드와 압둘 라시드 도스툼은 마수드가 장악한 나머지 지역과 도스툼이 장악한 탈레반에 대한 공세를 준비하던 탈레반에 맞서 통일전선(북방연합)을 창설했다.통일전선에는 마수드의 타지크군과 도스툼의 우즈베키스탄군 외에 하지 모하마드 모하키크가 이끄는 하자라군과 압둘 하크, 하지 압둘 카디르 등의 지휘관이 이끄는 파슈툰군이 포함됐다.압둘 라힘 가푸르자이, 압둘라 압둘라 압둘라, 마수드 칼릴리 등 유명 정치인들과 통일전선 외교관들.1996년 9월 탈레반이 카불을 정복한 이후 2001년 11월까지 연합전선은 바다흐샨, 카피사, 타하르, 파르완, 쿠나르, 누리스탄, 라그만, 사망간, 쿤두즈, 곤, 바미안 등의 지역에서 아프간 인구의 약 30%를 장악했다.

오랜 전투 끝에, 특히 북부 도시 마자르-이-샤리프를 위한 압둘 라시드 도스툼과 준쉬 군대는 1998년 탈레반과 그들의 동맹군에 의해 패배했다.도스툼은 그 후 망명길에 올랐다.아흐마드 샤 마수드는 아프가니스탄 내에서 탈레반으로부터 영토의 광대한 지역을 방어할 수 있었던 유일한 주요 반 탈레반 지도자로 남아 있었다.

마수드는 그의 지배하에 있는 지역에서 민주주의 기관을 설립하고 여성 권리 선언에 서명했다.마수드 지역에서는 여성과 소녀들이 아프간 부르카를 입을 필요가 없었다.그들은 일하고 학교에 가는 것이 허락되었다.적어도 두 개의 알려진 사례에서, 마수드는 개인적으로 강제 결혼에 대해 개입했다.

그것은 우리의 신념이며 우리는 남성과 여성 모두 전능하신 신에 의해 창조되었다고 믿는다.둘 다 동등한 권리를 가지고 있다.여성은 교육을, 여성은 직업을, 여성은 남성과 같이 사회에서 역할을 할 수 [162]있다.

--

마수드는 아프가니스탄에서 여성들은 몇 세대에 걸쳐 억압을 받아왔다고 단호히 주장한다.그는 이 나라의 문화적 환경이 여성들을 질식시키지만 탈레반은 억압으로 이를 악화시키고 있다고 말한다.그의 가장 야심찬 프로젝트는 이러한 문화적 편견을 깨고 여성들에게 더 많은 공간, 자유, 평등을 주는 것이다. 그들은 [162]남성과 같은 권리를 갖게 될 것이다.

--

아프가니스탄의 전통은 극복해야 할 세대 또는 그 이상이 필요하며 오직 교육에 의해서만 도전할 수 있다고 그는 말했다.2001년 본에서 열린 아프가니스탄 국제회의에 아프간 외교관으로 참여한 후마윤 탄다르는 "언어, 민족성, 지역의 어려움도 마수드에게 숨막히게 했다"고 말했다.그래서...그는 우리가 처한 상황을 뛰어넘어 오늘날까지도 우리 자신을 찾을 수 있는 단결을 만들고 싶어했다.이것은 종교의 규율에도 적용된다.Jean-José Puig는 Massoud가 식사 전에 기도를 이끌거나 때때로 동료 이슬람교도들에게 기도를 이끌도록 요청했지만 기독교 친구 Jean-José Puig나 유대인 프린스턴 대학 교수인 Michael Barry에게 주저하지 않고 "Jean-José, 우리는 같은 신을 믿는다.점심이나 저녁 식사 전에 기도문을 모국어로 알려주세요."[162]

휴먼라이츠워치는 1996년 10월부터 2001년 9월 마수드가 암살될 때까지 마수드의 직할부대에 대한 인권범죄는 없었다고 밝히고 40만100만 명의 아프간인이 탈레반에서 [166][179][180]마수드 지역으로 도피했다.내셔널 지오그래픽은 다큐멘터리 '탈레반 내부'에서 "미래 탈레반 대학살을 방해하는 유일한 것은 아마드 샤 마수드"[166]라고 결론지었다.

탈레반은 마수드가 저항을 멈추도록 여러 차례 권좌를 제의했다.마수드는 거절했다.그는 한 인터뷰에서 다음과 같이 설명했다.

탈레반은 "총리직을 수락하고 우리와 함께하자"고 말하며, 그들은 이 나라에서 가장 높은 직책인 대통령직을 유지할 것이다. 하지만 어떤 대가를 치르더라도 말이다.우리 사이의 차이는 주로 사회와 국가의 원칙에 대한 우리의 사고방식에 관한 것이다.우리는 그들의 타협 조건을 받아들일 수 없다.그렇지 않으면 현대 민주주의의 원칙을 포기해야 할 것이다.우리는 근본적으로 "아프간 토후국"[181]이라고 불리는 체제에 반대한다.

--

통일전선은 평화를 위한 제안서에서 탈레반에게 전국적인 [182]민주선거를 향한 정치적 과정에 동참할 것을 요구했다.2001년 초, 마수드는 지역의 군사적 압력과 세계적인 정치적 호소라는 새로운 전략을 채택했다.파슈툰 지역을 포함한 아프간 사회의 밑바닥에서부터 탈레반 통치에 대한 분노가 점점 더 커지고 있었다.마수드는 "대중의 합의, 총선, 민주주의"라는 그들의 명분을 전 세계에 알렸다.동시에 그는 실패한 1990년대 초 카불 정부를 되살리지 않도록 매우 경계했다.이미 1999년, 그는 통일 전선이 [162][181][183]성공할 경우에 대비해 질서 유지와 민간인 보호를 위해 특별히 훈련한 경찰력 훈련을 시작했다.마수드는 다음과 같이 말했다.

탈레반은 무적이라고 볼 수 없는 세력이 아니다.그들은 지금 사람들과 멀리 떨어져 있다.그들은 과거보다 약해졌다.파키스탄과 오사마 빈 라덴, 그리고 탈레반을 지탱하는 다른 극단주의 단체들의 지원만이 있을 뿐이다.그 지원이 중단되면 [184]살아남기란 매우 어렵다.

--

1999년부터 타지크 아흐마드 샤 마수드와 파슈툰 압둘 하크에 의해 아프가니스탄의 모든 민족을 통합하기 위한 새로운 과정이 시작되었다.마수드가 타지크족, 하자라족, 우즈벡족, 그리고 일부 파슈툰족 지휘관들을 연합한 반면, 유명한 파슈툰족 지휘관 압둘 하크는 "탈레반의 인기가 하락하는 추세"에 따라 파슈툰족 탈레반의 망명자 수를 증가시켰다.두 사람 모두 추방된 아프간 왕 자히르 샤와 함께 일하기로 합의했다.퓰리처상 수상자인 스티브 콜이 '그랜드 파슈툰-타지크 동맹'이라고 지칭한 새 동맹의 대표들을 만난 국제 관계자들은 "오늘 이런 걸 하다니...파슈툰족, 타지크족, 우즈벡족, 하자라족...그들은 모두 아프가니스탄의 민족 균형 유지를 위해 국왕의 기치 아래 일할 준비가 되어 있었습니다."고위 외교관이자 아프가니스탄 전문가인 피터 톰센은 "'카불의 사자' (압둘 하크)와 '판지쉬르의 사자' (아흐마드 샤 마수드)...아프가니스탄의 3대 온건파인 하크, 마수드, 카르자이는 파슈툰-비파슈툰-남북분열을 초월할 수 있다."최고위 하자라와 우즈베키스탄 지도자 또한 그 과정의 일부였다.2000년 말, 마수드는 "아프가니스탄의 정치적 혼란을 해결하기 위한 로야 지르가, 즉 전통적인 원로회의"를 논의하기 위해 아프가니스탄 북부에서 열린 회의에서 이 새로운 동맹을 공식화했다.파슈툰-타직-하자라-우즈베크 평화 계획의 그 부분은 결국 실현되었다.작가이자 저널리스트인 Sebastian Junger의 만남에 대한 설명은 다음과 같습니다: "2000년에, 내가 그곳에 있었을 때...우연히 아주 재미있는 시간에 그곳에 있었다.마수드는 모든 민족에서 온 아프간 지도자들을 모았다.그들은 런던, 파리, 미국, 아프가니스탄, 파키스탄, 인도에서 날아왔다.그가 있던 북쪽 지역으로 모두 데려갔어요그는 세계 각국의 저명한 아프간인들로 구성된 회의를 열었고, 탈레반 이후 아프간 정부에 대해 논의하기 위해 그곳으로 데려왔습니다. 우리는 이 모든 사람들을 만나 간단히 인터뷰했습니다.한 명은 하미드 카르자이였고, 나는 그가 어떤 사람이 될 지 전혀 몰랐다"[183][185][186][187][188]고 말했다.

2001년 초 아흐마드 샤 마수드는 아프가니스탄의 모든 민족 지도자들과 함께 브뤼셀에서 열린 유럽의회에서 국제사회에 아프가니스탄 국민들에게 인도적 지원을 요청했습니다.그는 탈레반과 알카에다가 "이슬람에 대한 매우 잘못된 인식"을 도입했다면서 파키스탄과 빈 라덴의 지원 없이는 탈레반은 그들의 군사 작전을 1년까지 지속할 수 없을 것이라고 말했다.이번 유럽 방문에서 그는 또한 미국 영토에 대한 대규모 공격이 임박했다는 정보를 수집했다고 경고했다.유럽의회 의장인 니콜 폰테인은 그를 "아프간 자유의 장대"[189][190][191][192]라고 불렀다.

2001년 9월 9일 당시 48세였던 마수드는 아프가니스탄 타하르주 크화자 바호딘에서 언론인으로 가장한 두 아랍인의 자살 공격의 표적이 되었다.26년 동안 수많은 암살 시도에서 살아남은 마수드는 그를 병원으로 이송하는 헬리콥터에서 사망했다.마수드의 첫 번째 살해 시도는 1975년 헤크마티아르와 파키스탄 ISI 요원 2명이 마수드가 22살이었을 때 수행했다.2001년 초, 알카에다 암살 예정자들이 마수드의 [105][183][193][194]영토로 들어가려다 마수드의 군대에 붙잡혔다.장례식은 시골이지만 수십만 명의 애도자들이 참석했다.

마수드의 암살은 약 3000명의 목숨을 앗아간 9.11 테러와 관련이 있는 것으로 보이며, 마수드가 몇 달 전 유럽의회 연설에서 경고했던 테러 공격과 관련이 있는 것으로 보인다.존 P. 오닐은 2001년 말까지 대테러 전문가이자 연방수사국(FBI)의 부국장이었다.그는 FBI에서 은퇴했고 세계무역센터(WTC)의 보안국장직을 제안받았다.그는 9/11 테러 2주 전에 WTC에 취직했다.2001년 9월 10일, 오닐은 두 명의 친구에게 "우리는 만삭이다.그리고 우린 큰 일을 해야 해.아프가니스탄에서 몇 가지 일이 있었다.[마수드 암살에 대한 언급]아프가니스탄의 상황이 마음에 안 들어...변화가 느껴지고, 곧 일이 일어날 것이라고 생각합니다."오닐은 2001년 9월 11일 사우스 타워가 [195][196]붕괴되면서 사망했다.

9.11 테러 이후 마수드의 통일전선 부대와 압둘 라시드 도스툼의 연합전선 부대는 카불에서 미국의 공중 지원으로 탈레반 세력을 몰아냈다.2001년 10월부터 12월까지, 통일 전선은 이 나라의 대부분을 장악했고, 하미드 카르자이 정권 하에서 탈리반 이후의 과도 정부를 수립하는 데 중요한 역할을 했습니다.

전복과 또 다른 전쟁

서곡

2001년 9월 20일, 미국 대통령 조지 W. 부시는 의회 합동 회의에서 "알카에다의 지도부는 아프가니스탄에서 큰 영향력을 가지고 있으며 아프가니스탄의 대부분을 장악하는 탈레반 세력을 지지한다"고 말하며 9월 11일 테러의 책임을 잠정적으로 알 카에다에게 돌렸다.부시는 "우리는 탈레반 정권을 비난한다"면서 "오늘 밤 미국은 탈레반에 대해 다음과 같은 요구를 한다"고 밝혔으며, 그는 "협상이나 [197][198]논의에 개방적이지 않다"고 말했다.

- 알카에다의 모든 지도자를 미국에 인도하다

- 부당하게 투옥된 모든 외국인을 석방하다

- 외신기자, 외교관, 구호요원 보호

- 모든 테러 훈련 캠프를 즉시 폐쇄하라

- 모든 테러리스트와 지지자들을 적절한 당국에 넘겨라

- 미국에 테러 훈련 캠프에 대한 완전한 접근권을 주고

미국은 국제사회에 탈레반을 전복시키기 위한 군사작전을 지지해 달라고 청원했다.유엔은 9월 11일 테러 공격 이후 테러에 대한 두 가지 결의안을 발표했다.결의안은 모든 국가에 테러와 관련된 국제협약의 협력과 완전한 이행을 촉구하며 모든 [199][200]국가에 대한 합의된 권고사항을 명시했다.하원 도서관의 연구 브리핑에 따르면 유엔 안전보장이사회(UNSC)가 미국이 주도하는 군사작전을 승인하지는 않았지만 유엔 헌장에 따른 정당한 자위활동으로 광범위하게 인식됐고 안보리는 군사작전을 신속하게 승인했다.침략 후에 [201]나라를 안정시켰다"고 말했다.게다가 2001년 9월 12일 나토는 무장 공격에 [202]대한 자기 방어 차원에서 아프가니스탄에 대한 캠페인을 승인했다.

파키스탄 주재 탈레반 대사 압둘 살렘 자에프는 최후통첩에 대해 빈 라덴이 공격에 연루되었다는 "확실한 증거"를 요구하며 "우리의 입장은 미국이 증거와 증거를 가지고 있다면 그들은 그것을 제시해야 한다는 것"이라고 말했다.게다가, 탈레반은 빈 라덴에 대한 어떠한 재판도 아프간 법정에서 열어야 한다고 주장했다.자에프는 또 무역센터에서 일하는 4000명의 유대인들이 자살 임무에 대해 사전에 알고 있었으며 그날 결석했다고 주장했다.이 대응은 일반적으로 [203][204][205][206][207][208]최후통첩에 협력하려는 진지한 시도라기보다는 지연 전술로 치부되었다.[check quotation syntax] 9월 22일 아랍에미리트와 이후 사우디아라비아는 탈레반의 아프간 합법정부 인정을 철회하고 이웃 국가인 파키스탄만 외교관계를 맺게 됐다.10월 4일 탈레반은 이슬람 샤리아법에 따라 운영되는 국제재판에서 빈 라덴을 파키스탄에 넘겨 재판을 받도록 합의했지만 파키스탄은 그의 안전을 보장할 수 없다는 이유로 빈 라덴의 제안을 막았다.10월 7일 파키스탄 주재 탈레반 대사는 미국이 공식 요청을 하고 탈레반에 증거를 제시하면 빈 라덴을 체포해 이슬람 율법에 따라 재판을 하겠다고 제안했다.익명을 요구한 부시 행정부의 한 관리는 탈레반의 제안을 거절하고 미국은 그들의 [209][210][211]요구를 협상하지 않을 것이라고 말했다.

연합군의 침공

2001년 10월 7일, 9월 11일 공격이 있은 지 한 달도 채 지나지 않은 시점에서, 미국은 영국, 캐나다 및 나토 동맹국의 지원을 받아 탈레반과 알카에다 관련 [212][213]캠프를 폭격하며 군사 행동을 개시했다.군사 작전의 목적은 탈레반의 권좌에서 물러나고 테러리스트들이 아프가니스탄을 작전 [214]기지로 이용하는 것을 막는 것이었다.

CIA의 최정예 특수활동부(SAD) 부대는 아프가니스탄에 입성한 최초의 미군이었다(많은 다른 나라의 정보기관이 현장에 있거나 SAD 부대가 도착하기 전에 이미 극장 내에서 활동 중이었다). 왜냐하면 SAD 부대는 기술적으로 군사력이 아닌 민간 준군사조직으로 구성되어 있기 때문이다.그들은 이후의 미군 특수작전부대의 도착을 준비하기 위해 아프간 통일전선(북방동맹)에 합류했다.연합전선(북방연합)과 SAD 및 특수부대는 연합군의 사상자를 최소화하고 국제 재래식 지상군을 동원하지 않고 탈레반 전복을 위해 연합했다.워싱턴포스트는 2006년 존 리먼의 사설에서 다음과 같이 밝혔다.

아프간 작전이 미군 역사상 획기적인 사건이 된 것은 해군과 공군의 전술력과 함께 특수작전부대에 의해 기소되었기 때문이다. 아프간 북부동맹과 CIA의 작전은 동등하게 중요하고 완전히 통합되었다.대규모 육군이나 해병대 병력은 [215]고용되지 않았다.

10월 14일, 탈레반은 오사마 빈 라덴을 폭탄 테러 중단의 대가로 중립국에 넘겨주겠다고 제안했지만, 탈레반이 빈 라덴이 [216]개입했다는 증거가 주어졌을 경우에만 그러했다.미국은 이 제안을 거절하고 군사작전을 계속했다.마자르이샤리프는 11월 9일 우스타드 아타 모하마드 누르와 압둘 라시드 도스툼의 연합전선 부대에 함락되어 최소한의 저항으로 폭격을 가했다.

2001년 11월 모하마드 다우드가 이끄는 연합전선 부대에 의해 쿤두즈가 생포되기 전 탈레반과 알 카에다의 수천 명의 최고 지휘관, 정규 전사, 파키스탄 정보기관 요원 및 군 요원, 그리고 쿤두즈 공수부대 다른 자원자와 동조자들이 대피하여 공수되었다.파키스탄 북부 지역의 치트랄과 길기트에 있는 파키스탄 공군 기지로 파키스탄 육군 화물기가 쿤두즈에서 출발했다.이것은 쿤두즈 주변의 미군들에 의해 악의 공수라고 불렸고, 이후 언론 [217][218][219][220][221][222]보도에서 용어로 사용되었다.

11월 12일 밤 탈레반은 카불에서 남쪽으로 후퇴했다.11월 15일, 그들은 3개월간의 억류 끝에 8명의 서방 구호 요원을 석방했다.11월 13일 탈레반은 카불과 잘랄라바드에서 철수했다.결국 탈레반은 12월 초 마지막 거점인 칸다하르를 포기하고 [citation needed]항복하지 않고 해산했다.

표적 살해

미국은 주로 특수부대를 동원한 탈레반 지도자들과 때로는 무인항공기를 상대로 표적 살해를 감행해 왔다.영국군도 비슷한 전술을 사용했는데, 주로 아프가니스탄의 헬만드주(州)에서 그랬다.헤릭 작전 당시 영국 특수부대는 헬만드주에서 [citation needed]탈레반 고위 지휘관 50여 명을 대상으로 표적 살해를 감행했다.

탈레반은 또한 표적 살인을 사용했다.2011년 한 해에만 그들은 부르하누딘 라바니 전 아프간 대통령, 북부 아프가니스탄 경찰서장, 303 반탈레반 군단장, 모하마드 다우드, 쿤두즈 경찰서장 등 저명한 반탈레반 지도자들을 살해했다고 압둘 라만 카일리는 말했다.그들은 모두 통일전선의 마수드파에 속해 있었다.관타나모 수용소의 기소장에 따르면, 미 국방부는 탈레반이 표적 [223]살해를 포함한 잠복작전에 사용되는 40명의 잠복부대인 "지하드 칸다하르"를 유지할 것으로 보고 있다.

2001년 이후의 부활

2001년 9월 11일 미국에 대한 공격 이후 파키스탄은 탈레반에 대한 지원을 계속하고 있다는 비난을 받고 있지만 파키스탄은 이를 [224][225]부인하고 있다.2002년 중반 파키스탄의 망명 탈레반 지도자들은 서로 재결합하기 시작했다.그들은 파키스탄의 도시인 [226][227][228][229]퀘타에서 퀘타 슈라를 결성했다.

2001년 11월 카불이 반(反)탈레반 세력에 함락되자 ISI 세력은 전면 퇴각 중인 탈레반 민병대와 협력해 이들을 도왔다.2001년 11월 탈레반, 알카에다 전투원, ISI 요원들은 파키스탄 육군 화물기를 타고 쿤두즈에서 파키스탄 북부 지역에 있는 파키스탄 공군 기지로 대피했다.페르베즈 무샤라프 전 파키스탄 대통령은 회고록에서 "리처드 아미티지 전 미 국무부 부장관은 파키스탄이 탈레반을 계속 지원할 경우 "석기시대로 돌아가게 될 것"이라고 말했지만, 아미티지 전 대통령은 그 이후 "석기시대"[230][231][232][217][233][234][235][236][237]라는 표현을 사용하지 않았다고 밝혔다.

파슈툰 부족장 하미드 카르자이가 국가 임시 지도자로 선출되었고, 탈레반은 카르자이의 사면 제안에 따라 칸다하르를 포기했다.그러나 미국은 탈레반 지도자인 물라 오마르가 고향 [238]칸다하르에서 "품위 있게 살 수 있는" 사면의 일부를 거부했다.탈레반은 2001년 12월 본 협정에 초대받지 못했는데, 많은 이들이 탈레반의 전장 부활과 [239]분쟁 지속의 원인이었다고 언급하고 있다.이는 탈레반의 명백한 패배 때문이기도 하지만 미국이 탈레반의 참가를 허용하지 않는다는 조건 때문이기도 했다.2003년까지 탈레반은 재기의 조짐을 보였고 얼마 지나지 않아 그들의 반란이 진행되고 있었다.라크다르 브라히미 유엔 협상대표는 2006년 탈레반을 본으로 초청하지 않은 것은 "우리의 원죄"[240]라고 인정했다.

In May and June 2003, high Taliban officials proclaimed the Taliban regrouped and ready for guerrilla war to expel US forces from Afghanistan.[241][242] In late 2004, the then hidden Taliban leader Mohammed Omar announced an insurgency against "America and its puppets" (i.e. transitional Afghan government forces) to "regain the sovereignty of our country".[243]

On 29 May 2006, while according to American website The Spokesman-Review Afghanistan faced "a mounting threat from armed Taliban fighters in the countryside", a US military truck of a convoy in Kabul lost control and plowed into twelve civilian vehicles, killing one and injuring six people. The surrounding crowd got angry and a riot arose, lasting all day ending with 20 dead and 160 injured. When stone-throwing and gunfire had come from a crowd of some 400 men, the US troops had used their weapons "to defend themselves" while leaving the scene, a US military spokesman said. A correspondent for the Financial Times in Kabul suggested that this was the outbreak of "a ground swell of resentment" and "growing hostility to foreigners" that had been growing and building since 2004, and may also have been triggered by a US air strike a week earlier in southern Afghanistan killing 30 civilians, where she assumed that "the Taliban had been sheltering in civilian houses".[244][245]

The continued support from tribal and other groups in Pakistan, the drug trade, and the small number of NATO forces, combined with the long history of resistance and isolation, indicated that Taliban forces and leaders were surviving. Suicide attacks and other terrorist methods not used in 2001 became more common. Observers suggested that poppy eradication, which hurt the livelihoods of those Afghans who had resorted to their production, and civilian deaths caused by airstrikes, abetted the resurgence. These observers maintained that policy should focus on "hearts and minds" and on economic reconstruction, which could profit from switching from interdicting to diverting poppy production—to make medicine.[246][247]

Other commentators viewed Islamabad's shift from war to diplomacy as an effort to appease growing discontent.[248] Because of the Taliban's leadership structure, Mullah Dadullah's assassination in May 2007 did not have a significant effect, other than to damage incipient relations with Pakistan.[249]

Negotiations had long been advocated by then-Afghan President, Hamid Karzai, as well as reportedly the British and Pakistani governments, but resisted by the American government. Karzai offered peace talks with the Taliban in September 2007, but this was swiftly rejected by the insurgent group citing the presence of foreign troops.[250]

On 8 February 2009, US commander of operations in Afghanistan General Stanley McChrystal and other officials said that the Taliban leadership was in Quetta, Pakistan.[251] By 2009, a strong insurgency had coalesced, known as Operation Al Faath, the Arabic word for "victory" taken from the Koran,[252][253][254] in the form of a guerrilla war. The Pashtun tribal group, with over 40 million members (including Afghans and Pakistanis) had a long history of resistance to occupation forces, so the Taliban may have comprised only a part of the insurgency. Most post-invasion Taliban fighters were new recruits, mostly drawn from local madrasas.

In December 2009, Asia Times Online reported that the Taliban had offered to give the US "legal guarantees" that it would not allow Afghanistan to be used for attacks on other countries, and that the US had given no response.[255]

As of July 2016, the US Time magazine estimated 20% of Afghanistan to be under Taliban control with southernmost Helmand Province as their stronghold,[256] while US and international Resolute Support coalition commander General Nicholson in December 2016 likewise stated that 10% was in Taliban hands while another 26% of Afghanistan was contested between the Afghan government and various insurgency groups.[257]

On 7 August 2015, the Taliban killed about 50 people in Kabul. In August 2017, reacting to a hostile speech by US President Trump, a Taliban spokesman retorted that they would keep fighting to free Afghanistan of "American invaders".[258]

In January 2018, a Taliban suicide bomber killed over 100 people in Kabul using a bomb in an ambulance.

By 2020, after the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) had lost almost all of its conquered territory and committed less terrorist acts, the global think tank called the Institute for Economics & Peace considered the Taliban to have overtaken ISIL as the most dangerous terrorist group in the world due to their recent campaigns for territorial expansion.[259]

On 29 May 2020, it was reported that Mullah Omar's son Mullah Yaqoob was now acting as leader of the Taliban after numerous Quetta Shura members were infected with COVID-19.[260] It was previously confirmed on 7 May 2020 that Yaqoob had become head of the Taliban military commission, making him the insurgents' military chief.[261] Among those infected in the Quetta Shura, which continued to hold in-person meetings, were Hibatullah Akhundzada and Sirajuddin Haqqani, then commanders of the Taliban and Haqqani network respectively.[260]

Diplomatic negotiations

The Taliban's co-founder and then-second-in-command, Abdul Ghani Baradar, was one of the leading Taliban members who favored talks with the US and Afghan governments. Karzai's administration reportedly held talks with Baradar in February 2010; however, later that month, Baradar was captured in a joint US-Pakistani raid in the city of Karachi in Pakistan. The arrest infuriated Karzai and invoked suspicions that he was seized because the Pakistani intelligence community was opposed to Afghan peace talks.[262][263] Karzai declared after his re-election in the 2009 Afghan presidential election that he would host a "Peace Jirga" in Kabul in an effort for peace. The event, attended by 1,600 delegates, took place in June 2010, however the Taliban and the Hezb-i Islami Gulbuddin, who were both invited by Karzai as a gesture of goodwill did not attend the conference.[264]

A mindset change and strategy occurred within the Obama administration in 2010 to allow possible political negotiations to solve the war.[265] The Taliban themselves had refused to speak to the Afghan government, portraying them as an American "puppet". Sporadic efforts for peace talks between the US and the Taliban occurred afterward, and it was reported in October 2010 that Taliban leadership commanders (the "Quetta Shura") had left their haven in Pakistan and been safely escorted to Kabul by NATO aircraft for talks, with the assurance that NATO staff would not apprehend them.[266] After those talks concluded, it emerged that the leader of this Taliban delegation, who claimed to be Akhtar Mansour, the second-in-command of the Taliban, was actually an imposter who had duped NATO officials.[267]

Karzai confirmed in June 2011 that secret talks were taking place between the US and the Taliban,[268] but these collapsed by January 2012.[269] Further attempts to resume talks were canceled in March 2012,[270] and June 2013 following a dispute between the Afghan government and the Taliban regarding the latter's opening of a political office in Qatar. President Karzai accused the Taliban of portraying themselves as a government in exile.[271] In July 2015, Pakistan hosted the first official peace talks between Taliban representatives and the Afghan government. U.S and China attended the talks brokered by Pakistan in Murree as two observers.[272] In January 2016, Pakistan hosted a round of four-way talks with Afghan, Chinese and American officials, but the Taliban did not attend.[273] The Taliban did hold informal talks with the Afghan government in 2016.[274]

On 27 February 2018, following an increase in violence, Afghan President Ashraf Ghani proposed unconditional peace talks with the Taliban, offering them recognition as a legal political party and the release of the Taliban prisoners. The offer was the most favorable to the Taliban since the war started. It was preceded by months of national consensus building, which found that Afghans overwhelmingly supported a negotiated end to the war.[275][276] Two days earlier, the Taliban had called for talks with the US, saying "It must now be established by America and her allies that the Afghan issue cannot be solved militarily. America must henceforth focus on a peaceful strategy for Afghanistan instead of war."[277]

US President Donald Trump twice accused Pakistan of harboring the Taliban and of inaction against terrorists, first in August 2017 then again in January 2018.[278][279]

Deal with the US

On 29 February 2020, the US–Taliban deal, officially titled Agreement for Bringing Peace to Afghanistan, was signed in Doha, Qatar.[280] The provisions of the deal included the withdrawal of all American and NATO troops from Afghanistan, a Taliban pledge to prevent al-Qaeda from operating in areas under Taliban control, and talks between the Taliban and the Afghan government.[281]

Despite the peace agreement between the US and the Taliban, insurgent attacks against Afghan security forces were reported to have surged in the country. In the 45 days after the agreement (between 1 March and 15 April 2020), the Taliban conducted more than 4,500 attacks in Afghanistan, which showed an increase of more than 70% as compared to the same period in the previous year.[282] Talks between the Afghan government and the Taliban began in Doha on 12 September 2020. The negotiations were set for March but have been delayed over a prisoner exchange dispute. Mawlavi Abdul Hakim led the initial negotiations for the Taliban. Abdullah Abdullah was one of the leading figures for the Afghan republic's negotiating team. The Afghan government team also comprised women's rights activists.[283]

2021 offensive and return to power

In mid 2021, the Taliban led a major offensive in Afghanistan during the withdrawal of US troops from the country, which gave them control of over half of Afghanistan's 421 districts as of 23 July 2021.[284] [285]

By mid-August 2021, the Taliban controlled every major city in Afghanistan; following the near seizure of the capital Kabul, the Taliban occupied the Presidential Palace after the incumbent President Ashraf Ghani fled Afghanistan to the United Arab Emirates.[286][287] Ghani's Asylum was confirmed by the UAE Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation on 18 August 2021.[288][289] Remaining Afghan forces under the leadership of Amrullah Saleh, Ahmad Massoud, and Bismillah Khan Mohammadi retreated to Panjshir to continue resistance.[290][291][292]

Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan (2021–)

The Taliban had "seized power from an established government backed by some of the world's best-equipped militaries"; and as an ideological insurgent movement dedicated to "bringing about a truly Islamic state" its victory has been compared to that of the Chinese Communist Revolution in 1940s or Iranian Revolution of 1979, with their "sweeping" remake of society. However, as of 2021–2022, senior Taliban leaders have emphasized the "softness" of their revolution and how they desired "good relations" with the United States, in discussions with American journalist Jon Lee Anderson.[87]

Anderson notes that the Taliban's war against any "graven images", so vigorous in their early rule, has been abandoned, perhaps made impossible by smartphones and Instagram. One local observer (Sayed Hamid Gailani) has argued the Taliban have not killed "a lot" of people after returning to power. Women are seen out on the street, Zabihullah Mujahid (acting Deputy Minister of Information and Culture) noted there are still women working in a number of government ministries, and claimed that girls will be allowed to attend secondary education when bank funds are unfrozen and the government can fund "separate" spaces and transportation for them.[87]

When asked about the slaughter of Hazara Shia by the first Taliban régime, Suhail Shaheen, the Taliban nominee for Ambassador to the U.N. told Anderson "The Hazara Shia for us are also Muslim. We believe we are one, like flowers in a garden."[87] In late 2021, journalists from The New York Times embedded with a six-man Taliban unit tasked with protecting the Shi'ite Sakhi Shrine in Kabul from the Islamic State, noting "how seriously the men appeared to take their assignment." The unit's commander said that "We do not care which ethnic group we serve, our goal is to serve and provide security for Afghans."[293] In response to "international criticism" over lack of diversity, an ethnic Hazara was appointed deputy health minister, and an ethnic Tajik appointed deputy trade minister.[87]

On the other hand, the Ministry of Women's Affairs has been closed and its building is the new home of Ministry for the Propagation of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice. According to Anderson, some women still employed by the government are "being forced to sign in at their jobs and then go home, to created the illusion of equity"; and the appointment of ethnic minorities has been dismissed by an "adviser to the Taliban" as tokenism.[87]

Reports have "circulated" of

"Hazara farmers being forced from their land by ethnic Pashtuns, of raids of activists' homes, and of extrajudicial executions of former government soldiers and intelligence agents".[87]

According to a Human Rights Watch's report released in November 2021, the Taliban killed or forcibly disappeared more than 100 former members of the Afghan security forces in the three months since the takeover in just the four provinces of Ghazni, Helmand, Kandahar, and Kunduz. According to the report, the Taliban identified targets for arrest and execution through intelligence operations and access to employment records that were left behind. Former members of the security forces were also killed by the Taliban within days of registering with them to receive a letter guaranteeing their safety.[294]

Despite Taliban claims that the ISIS has been defeated, IS carried out suicide bombings in October 2021 at Shia mosques in Kunduz and Kandahar, killing over 115 people. As of late 2021, there were still "sticky bomb" explosions "every few days" in the capital Kabul.[87]

Explanations for the relative moderation of the new Taliban government and statements from its officials such as – “We have started a new page. We do not want to be entangled with the past,”[87]—include that it did not expect to take over the country so quickly and still had "problems to work out among" their factions”;[87] that $7 billion in Afghan government funds in US banks has been frozen, and that the 80% of the previous government's budget that came from "the United States, its partners, or international lenders", has been shut off, creating serious economic crisis; according to the U.N. World Food Program country director, Mary Ellen McGroarty, as of late 2021, early 2022 "22.8 million Afghans are already severely food insecure, and seven million of them are one step away from famine"; and that the world community has "unanimously" asked the Taliban "to form an inclusive government, ensure the rights of women and minorities and guarantee that Afghanistan will no more serve as the launching pad for global terrorist operations", before it recognizes the Taliban government.[295] In conversation with journalist Anderson, senior Taliban leaders implied that the harsh application of sharia during their first era of rule in the 1990s was necessary because of the "depravity" and "chaos" that remained from the Soviet occupation, but that now "mercy and compassion" were the order of the day.[87] This was contradicted by former senior members of the Ministry of Women's Affairs, one of which who told Anderson, "they will do anything to convince the international community to give them financing, but eventually I'll be forced to wear the burqa again. They are just waiting."[87]

On 1 December 2021, clashes erupted between the Taliban and Iran leading to casualties on both sides.[296][297]

2021–present education policy

In September 2021, the government ordered primary schools to reopen for both sexes and announced plans to reopen secondary schools for male students, without committing to do the same for female students.[298] While the Taliban states that female college students will be able to resume higher education provided that they are segregated from male students (and professors, when possible),[299] The Guardian notes that "if the high schools do not reopen for girls, the commitments to allow university education would become meaningless once the current cohort of students graduated."[298] Higher Education Minister Abdul Baqi Haqqani said that female university students will be required to observe proper hijab, but did not specify if this required covering the face.[299]

Kabul University reopened in February 2022, with female students attending in the morning and males in the afternoon. Other than the closure of the music department, few changes to the curriculum were reported.[300] Female students were officially required to wear an abaya and a hijab to attend, although some wore a shawl instead. Attendance was reportedly low on the first day.[301]

In March 2022, the Taliban abruptly halted plans to allow girls to resume secondary school education even when separated from males.[302] Apart from current university students, "sixth is now the highest grade girls may attend" according to The Washington Post. The Afghan Ministry of Education cited the lack of an acceptable design for female student uniforms.[303]

International recognition

Following the Taliban's ascension to power, the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan's model of governance has been widely criticized by the international community, despite the government's repeated calls for international recognition and engagement. Acting Prime Minister Mohammad Hassan Akhund stated that his interim administration has met all conditions required for official recognition.[304] In a bid to gain recognition, the Taliban sent a letter in September 2021 to the UN to accept Suhail Shaheen as Permanent Representative of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan – a request that had already been rejected by the UN Credentials Committee in 2021.[305]

On 10 October 2021, Russia hosted the Taliban for talks in Moscow in an effort to boost its influence across Central Asia. Officials from 10 different countries- Russia, China, Pakistan, India, Iran and five formerly Soviet Central Asian states- attended the talks, which were held during the Taliban’s first official trip to Europe since their return to power in mid-August 2021.[306] The Taliban won backing from the 10 regional powers for the idea of a United Nations donor conference to help the country stave off economic collapse and a humanitarian catastrophe, calling for the UN to convene such a conference as soon as possible to help rebuild the country. Russian officials also called for action against Islamic State (IS) fighters, who Russia said have started to increase their presence in Afghanistan since the Taliban's takeover. The Taliban delegation, which was led by Deputy Prime Minister Abdul Salam Hanafi, said that "Isolating Afghanistan is in no one's interests," arguing that the extremist group did not pose any security threat to any other country. The Taliban asked the international community to recognize its government,[307] but no country has yet recognized the new Afghan government.[308]

On 23 January 2022, a Taliban delegation arrived in Oslo, and closed-door meetings were held during the Taliban’s first official trip to Western Europe and second official trip to Europe since their return to power.[309] Western diplomats told the Taliban that humanitarian aid to Afghanistan would be tied to an improvement in human rights.[310] The Taliban delegation, led by acting Foreign Minister Amir Khan Muttaqi, met senior French foreign ministry officials, Britain’s special envoy Nigel Casey, EU Special Representative for Afghanistan and members of the Norwegian foreign ministry. This followed the announcement by the UN Security Council Counter-Terrorism Committee that the committee would extend a travel ban exemption until 21 March 2022 for 14 listed Taliban members to continue attending talks, along with a limited asset-freeze exemption for the financing of exempted travel.[311] However, the Afghan Foreign Minister Amir Khan Muttaqi said that the international community’s call for the formation of an inclusive government was a political “excuse" after the 3-day Oslo visit.[312]

At the United Nations Security Council meeting in New York on 26 January 2022, Norwegian Prime Minister Jonas Gahr Store said the Oslo talks appeared to have been “serious” and “genuine”. Norway says the talks do “not represent a legitimisation or recognition of the Taliban”.[313] In the same meeting, the Russian Federation’s delegate said attempts to engage the Taliban through coercion are counter-productive, calling on Western states and donors to return frozen funds.[314] China’s representative said the fact that aid deliveries have not improved since the adoption of UNSC 2615 (2021) proves that the issue has been politicized, as some parties seek to use assistance as a bargaining chip.[315]

Turkmenistan, the Russian Federation, and China were the first countries to accept the diplomatic credentials of Taliban-appointed envoys, although this is not equivalent to official recognition.[316][317][318]

Ideology and aims

The Taliban's ideology has been described as combining an "innovative" form of Sharia Islamic law which is based on Deobandi fundamentalism and militant Islamism, combined[319] with Pashtun social and cultural norms which are known as Pashtunwali,[1][2][320][321] because most Taliban are Pashtun tribesmen.

| Part of a series on Islamism |

|---|

| |

The Taliban's ideology has been described as an "innovative form of sharia combining Pashtun tribal codes",[322] or Pashtunwali, with radical Deobandi interpretations of Islam favoured by Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam and its splinter groups.[323] Their ideology was a departure from the Islamism of the anti-Soviet mujahideen rulers[clarification needed] and the radical Islamists[clarification needed] inspired by the Sayyid Qutb (Ikhwan).[324] The Taliban have said they aim to restore peace and security to Afghanistan, including Western troops leaving, and to enforce Sharia, or Islamic law, once in power.[325][326][327]

According to journalist Ahmed Rashid, at least in the first years of their rule, the Taliban adopted Deobandi and Islamist anti-nationalist beliefs, and they opposed "tribal and feudal structures," removing traditional tribal or feudal leaders from leadership roles.[328]

The Taliban strictly enforced their ideology in major cities like Herat, Kabul, and Kandahar. But in rural areas, the Taliban had little direct control, and as a result, they promoted village jirgas, so in rural areas, they did not enforce their ideology as stringently as they enforced it in cities.[329]

Ideological influencers

The Taliban's religious/political philosophy, especially during its first régime from 1996 to 2001, was heavily advised and influenced by Grand Mufti Rashid Ahmed Ludhianvi and his works. Its operating political and religious principles since its founding however was modelled on those of Abul A'la Maududi and the Jamaat-e-Islami movement.[330]

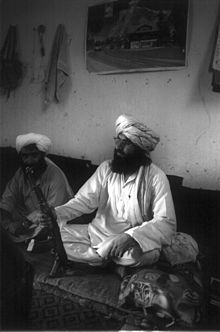

(Deobandi) Islamic rules

Written works published by the group's Commission of Cultural Affairs including Islami Adalat, De Mujahid Toorah— De Jihad Shari Misalay, and Guidance to the Mujahideen outlined the core of the Taliban Islamic Movement's philosophy regarding jihad, sharia, organization, and conduct.[331] The Taliban régime interpreted the Sharia law in accordance with the Hanafi school of Islamic jurisprudence and the religious edicts of Mullah Omar.[86] The Taliban forbade the consumption of pork and alcohol, the use of many types of consumer technology such as music,[332] television,[332] filming,[332] and the Internet, as well as most forms of art such as paintings or photography,[332] participation in sports,[333] including football and chess;[333] Recreational activities such as Kite-flying and the keeping of pigeons and other pets were also forbidden, and the birds were killed according to the Taliban's rules.[333] Movie theatres were closed and repurposed as mosques.[333] The celebration of the Western and Iranian New Years was also forbidden.[334] Taking photographs and displaying pictures and portraits were also forbidden, because the Taliban considered them forms of idolatry.[333] This extended even to "blacking out illustrations on packages of baby soap in shops and painting over road-crossing signs for livestock.[87]

Women were banned from working,[335] girls were forbidden to attend schools or universities,[335] were required to observe purdah (physical separation of the sexes) and awrah (concealing the body with clothing), and to be accompanied by male relatives outside their households; those who violated these restrictions were punished.[335] Men were forbidden to shave their beards and they were also required to let them grow and keep them long according to the Taliban's rules, and they were also required to wear turbans outside their households.[336][337] Prayer was made compulsory and those men who did not respect the religious obligation after the azaan were arrested.[336] Gambling was banned,[334] and the Taliban punished thieves by amputating their hands or feet.[333] In 2000, the Taliban's leader Mullah Omar officially banned opium cultivation and drug trafficking in Afghanistan;[338][339][340] the Taliban succeeded in nearly eradicating the majority of the opium production (99%) by 2001.[339][340][341] During the Taliban's governance of Afghanistan, drug users and dealers were both severely persecuted.[338]

Afghan Shiites were persecuted during the first Taliban rule. Most Afghan Shiites are members of the Hazara ethnic group, which accounts for almost 10% of Afghanistan's entire population.[342] However, a few Shiite Islamists supported the Taliban rule, such as Ustad Muhammad Akbari.[343] In recent years, the Taliban have attempted to court Shiites, appointing a Shiite cleric as a regional governor and recruiting Hazaras to fight against ISIL-KP, in order to distance themselves from their past sectarian reputation and improve their relations with the Shiite government of Iran.[344]

Along with Shiite Muslims, the small Christian community was also persecuted by the Taliban.[345] The Taliban announced in May 2001 that it would force Afghanistan's Hindu population to wear special badges, which has been compared to the treatment of Jews in Nazi Germany.[346] In general, the Taliban treated the Sikhs and Jews of Afghanistan better than Afghan Shiites, Hindus and Christians.[347] During the first period of Taliban rule, only two known Jews were left in Afghanistan, Zablon Simintov and Isaac Levy (c. 1920–2005). Levy relied on charity to survive, while Simintov ran a store selling carpets and jewelry until 2001. They lived on opposite sides of the dilapidated Kabul synagogue. They kept denouncing each other to the authorities, and both spent time in jail for continuously "arguing." The Taliban also confiscated the synagogue's Torah scroll. However, the two men were later released from prison when Taliban officials became annoyed by their arguing.[348]

In January 2005, Levy died of natural causes, leaving Simintov as the sole known Jew in Afghanistan.[349] He cared for the only synagogue in Afghanistan's capital, Kabul.[350] He was still trying to recover the confiscated Torah. Simintov, who does not speak Hebrew,[351] claimed that the man who stole the Torah is now in US custody in Guantanamo Bay. Simintov has a wife and two daughters, all of whom emigrated to Israel in 1998, and he said he was considering joining them. However, when he was asked if he would go to Israel during an interview, Simintov retorted, "Go to Israel? What business do I have there? Why should I leave?"[351] In April 2021, Simintov announced that he would emigrate to Israel after the High Holy Days of 2021, due to the fear that the planned withdrawal of US troops from Afghanistan would result in the Taliban's return to power.[352]

Throughout August 2021, Simintov remained in Kabul, despite having had a chance to escape.[353][352][354] Despite initially stating that he would put up with the Taliban for the second time, it has been reported that Simintov emigrated to a presently undisclosed country before the Jewish holiday of Rosh Hashanah on 6 September 2021 after he received death threats from the Taliban or ISIS-KP, taking 30 other refugees with him, including 28 women and children.[355] Ami Magazine, an Orthodox Jewish publication which is based in New York City, reported that Simintov was en route to the United States. Simintov stated that it was not the Taliban but rather the possibility of other, more radical Islamist groups like IS-KP taking him hostage that resulted in his exit from the country.[356][357] After leaving Afghanistan, Simintov granted his wife a divorce.[358] It was then discovered that an unbeknownst distant cousin of Simintov, Tova Moradi, fled the country sometime in October following Simintov's departure.[359] Contrary to official reports which stated that "no Jewish" person was living in the country, it is believed that Moradi was the last Jew who lived in Afghanistan.[360][361]

Unlike other Islamic fundamentalist organizations, the Taliban are not Salafists. Although wealthy Arab nations had brought Salafist Madrasas to Afghanistan during the Soviet war in the 1980s, the Taliban's strict Deobandi leadership suppressed the Salafi movement in Afghanistan after it first came to power in the 1990s. Following the 2001 US invasion, the Taliban and Salafists joined forces in order to wage a common war against NATO forces, but Salafists were relegated to small groups which were under the Taliban's command.[362]

The Taliban are averse to debating doctrine with other Muslims and "did not allow even Muslim reporters to question [their] edicts or to discuss interpretations of the Qur'an."[127]

The Taliban, Mullah Omar in particular, emphasised dreams as a means of revelation.[363][364]

Pashtun cultural influences

The Taliban frequently used the pre-Islamic Pashtun tribal code, Pashtunwali, in order to make decisions with regard to certain social matters. Such is the case with the Pashtun practice of equally dividing inheritances among sons, even though the Qur'an clearly states that women are supposed to receive one-half of a man's share.[365][366]

According to Ali A. Jalali and Lester Grau, the Taliban "received extensive support from Pashtuns across the country who thought that the movement might restore their national dominance. Even Pashtun intellectuals in the West, who differed with the Taliban on many issues, expressed support for the movement on purely ethnic grounds."[367]

Views on the Bamyan Buddhas

In 1999, Mullah Omar issued a decree in which he called for the protection of the Buddha statues at Bamyan, two 6th-century monumental statues of standing buddhas which were carved into the side of a cliff in the Bamyan valley in the Hazarajat region of central Afghanistan. But in March 2001, the Taliban destroyed the statues, following a decree by Mullah Omar which stated: "all the statues around Afghanistan must be destroyed."[368]

Yahya Massoud, brother of the anti-Taliban and resistance leader Ahmad Shah Massoud, recalls the following incident after the destruction of the Buddha statues at Bamyan:

It was the spring of 2001. I was in Afghanistan's Panjshir Valley, together with my brother Ahmad Shah Massoud, the leader of the Afghan resistance against the Taliban, and Bismillah Khan, who currently serves as Afghanistan's interior minister. One of our commanders, Commandant Momin, wanted us to see 30 Taliban fighters who had been taken hostage after a gun battle. My brother agreed to meet them. I remember that his first question concerned the centuries-old Buddha statues that were dynamited by the Taliban in March of that year, shortly before our encounter. Two Taliban combatants from Kandahar confidently responded that worshiping anything outside of Islam was unacceptable and that therefore these statues had to be destroyed. My brother looked at them and said, this time in Pashto, 'There are still many sun- worshippers in this country. Will you also try to get rid of the sun and drop darkness over the Earth?'[369]

Views on bacha bazi

The Afghan custom of bacha bazi, a form of pederastic sexual slavery and pedophilia which is traditionally practiced in various provinces of Afghanistan, was also forbidden under the six-year rule of the Taliban régime.[370] Under the rule of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, bacha bazi, a form of child sexual abuse between older men and young adolescent "dancing boys", has carried the death penalty.[371][372]

The practice remained illegal during the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan's rule, but the laws were seldom enforced against powerful offenders and police had reportedly been complicit in related crimes.[373][374][375][376] A controversy arose during the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan's rule, after allegations surfaced that US government forces in Afghanistan after the invasion of the country deliberately ignored bacha bazi.[377] The US military responded by claiming the abuse was largely the responsibility of the "local Afghan government".[378] The Taliban has criticized the US role in the abuse of Afghan children.

Consistency of the Taliban's ideology

The Taliban's ideology is not static. Before its capture of Kabul, members of the Taliban talked about stepping aside once a government of "good Muslims" took power and once law and order were restored. The decision-making process of the Taliban in Kandahar was modelled on the Pashtun tribal council (jirga), together with what was believed to be the early Islamic model. Discussion was followed by the building of a consensus by the believers.[379]

As the Taliban's power grew, Mullah Omar made decisions without consulting the jirga or visiting other parts of the country. He visited the capital, Kabul, only twice while he was in power. Taliban spokesman Mullah Wakil explained:

Decisions are based on the advice of the Amir-ul Momineen. For us consultation is not necessary. We believe that this is in line with the Sharia. We abide by the Amir's view even if he alone takes this view. There will not be a head of state. Instead there will be an Amir al-Mu'minin. Mullah Omar will be the highest authority and the government will not be able to implement any decision to which he does not agree. General elections are incompatible with Sharia and therefore we reject them.[380]

Another sign that the Taliban's ideology was evolving was Mullah Omar's 1999 decree in which he called for the protection of the Buddha statues at Bamyan and the destruction of them in 2001.[381]

Evaluations and criticisms

The author Ahmed Rashid suggests that the devastation and hardship which resulted from the Soviet invasion and the period which followed it influenced the Taliban's ideology.[382] It is said that the Taliban did not include scholars who were learned in Islamic law and history. The refugee students, brought up in a totally male society, not only had no education in mathematics, science, history or geography, but also had no traditional skills of farming, herding, or handicraft-making, nor even knowledge of their tribal and clan lineages.[382] In such an environment, war meant employment, peace meant unemployment. Dominating women simply affirmed manhood. For their leadership, rigid fundamentalism was a matter not only of principle, but also of political survival. Taliban leaders "repeatedly told" Rashid that "if they gave women greater freedom or a chance to go to school, they would lose the support of their rank and file."[383]

The Taliban have been criticised for their strictness towards those who disobeyed their imposed rules, and Mullah Omar has been criticized for titling himself Amir al-Mu'minin.

Mullah Omar was criticised for calling himself Amir al-Mu'minin on the grounds that he lacked scholarly learning, tribal pedigree, or connections to the Prophet's family. Sanction for the title traditionally required the support of all of the country's ulema, whereas only some 1,200 Pashtun Taliban-supporting Mullahs had declared that Omar was the Amir. According to Ahmed Rashid, "no Afghan had adopted the title since 1834, when King Dost Mohammed Khan assumed the title before he declared jihad against the Sikh kingdom in Peshawar. But Dost Mohammed was fighting foreigners, while Omar had declared jihad against other Afghans."[387]

Another criticism was that the Taliban called their 20% tax on truckloads of opium "zakat", which is traditionally limited to 2.5% of the zakat-payers' disposable income (or wealth).[387]

The Taliban have been compared to the 7th-century Kharijites who developed extreme doctrines which set them apart from both mainstream Sunni and Shiʿa Muslims. The Kharijites were particularly noted for adopting a radical approach to takfir, whereby they declared that other Muslims were unbelievers and deemed them worthy of death.[388][389][390]

In particular, the Taliban have been accused of takfir towards Shia. After the August 1998 slaughter of 8,000 mostly Shia Hazara non-combatants in Mazar-i-Sharif, Mullah Niazi, the Taliban commander of the attack and the new governor of Mazar, declared from Mazar's central mosque:

Last year you rebelled against us and killed us. From all your homes you shot at us. Now we are here to deal with you. The Hazaras are not Muslims and now have to kill Hazaras. You either accept to be Muslims or leave Afghanistan. Wherever you go we will catch you. If you go up we will pull you down by your feet; if you hide below, we will pull you up by your hair.[391]

Carter Malkasian, in one of the first comprehensive historical works on the Afghan war, argues that the Taliban are oversimplified in most portrayals. While Malkasian thinks that "oppressive" remains the best word to describe them, he points out that the Taliban managed to do what multiple governments and political players failed to: bring order and unity to the "ungovernable land". The Taliban curbed the atrocities and excesses of the Warlord period of the civil war from 1992–1996. Malkasian further argues that the Taliban's imposing of Islamic ideals upon the Afghan tribal system was innovative and a key reason for their success and durability. Given that traditional sources of authority had been shown to be weak in the long period of civil war, only religion had proved strong in Afghanistan. In a period of 40 years of constant conflict, the traditionalist Islam of the Taliban proved to be far more stable, even if the order they brought was "an impoverished peace".[392]: 50–51

Condemned practices

The Taliban have been internationally condemned for their harsh enforcement of their interpretation of Islamic Sharia law, which has resulted in their brutal treatment of many Afghans. During their rule from 1996 to 2001, the Taliban enforced a strict interpretation of Sharia, or Islamic law.[86] The Taliban and their allies committed massacres against Afghan civilians, denied UN food supplies to 160,000 starving civilians, and conducted a policy of scorched earth, burning vast areas of fertile land and destroying tens of thousands of homes. While the Taliban controlled Afghanistan, they banned activities and media including paintings, photography, and movies that depicted people or other living things. They also prohibited music using instruments, with the exception of the daf, a type of frame drum.[357] The Taliban prevented girls and young women from attending school, banned women from working jobs outside of healthcare (male doctors were prohibited from treating women), and required that women be accompanied by a male relative and wear a burqa at all times when in public. If women broke certain rules, they were publicly whipped or executed.[393] The Taliban harshly discriminated against religious and ethnic minorities during their rule and they have also committed a cultural genocide against the people of Afghanistan by destroying numerous monuments, including the famous 1500-year-old Buddhas of Bamiyan. According to the United Nations, the Taliban and their allies were responsible for 76% of Afghan civilian casualties in 2010, and 80% in 2011 and 2012.[394] The group is internally funded by its involvement in the illegal drug trade which it participates in by producing and trafficking in narcotics such as heroin,[395][396] extortion, and kidnapping for ransom.[397][398] They also seized control of mining operations in the mid-2010s that were illegal under the previous government.[399]

Massacre campaigns

According to a 55-page report by the United Nations, the Taliban, while trying to consolidate control over northern and western Afghanistan, committed systematic massacres against civilians. UN officials stated that there had been "15 massacres" between 1996 and 2001. They also said, that "[t]hese have been highly systematic and they all lead back to the [Taliban] Ministry of Defense or to Mullah Omar himself." "These are the same type of war crimes as were committed in Bosnia and should be prosecuted in international courts", one UN official was quoted as saying. The documents also reveal the role of Arab and Pakistani support troops in these killings. Bin Laden's so-called 055 Brigade was responsible for mass-killings of Afghan civilians. The report by the United Nations quotes "eyewitnesses in many villages describing Arab fighters carrying long knives used for slitting throats and skinning people". The Taliban's former ambassador to Pakistan, Mullah Abdul Salam Zaeef, in late 2011 stated that cruel behaviour under and by the Taliban had been "necessary".[400][401][161][402]

In 1998, the United Nations accused the Taliban of denying emergency food by the UN's World Food Programme to 160,000 hungry and starving people "for political and military reasons".[403] The UN said the Taliban were starving people for their military agenda and using humanitarian assistance as a weapon of war.[404][405][406][407][408]

On 8 August 1998, the Taliban launched an attack on Mazar-i-Sharif. Of 1500 defenders only 100 survived the engagement. Once in control the Taliban began to kill people indiscriminately. At first shooting people in the street, they soon began to target Hazaras. Women were raped, and thousands of people were locked in containers and left to suffocate. This ethnic cleansing left an estimated 5,000 to 6,000 people dead. At this time ten Iranian diplomats and a journalist were killed. Iran assumed the Taliban had murdered them, and mobilised its army, deploying men along the border with Afghanistan. By the middle of September there were 250,000 Iranian personnel stationed on the border. Pakistan mediated and the bodies were returned to Tehran towards the end of the month. The killings of the diplomats had been carried out by Sipah-e-Sahaba, a Pakistani Sunni group with close ties to the ISI. They burned orchards, crops and destroyed irrigation systems, and forced more than 100,000 people from their homes with hundreds of men, women and children still unaccounted for.[409][410][411][412][413]

In a major effort to retake the Shomali Plains to the north of Kabul from the United Front, the Taliban indiscriminately killed civilians, while uprooting and expelling the population. Among others, Kamal Hossein, a special reporter for the UN, reported on these and other war crimes. In Istalif, a town famous for handmade potteries and which was home to more than 45,000 people, the Taliban gave 24 hours' notice to the population to leave, then completely razed the town leaving the people destitute.[414][415]

In 1999, the town of Bamian was taken, hundreds of men, women and children were executed. Houses were razed and some were used for forced labour. There was a further massacre at the town of Yakaolang in January 2001. An estimated 300 people were murdered, along with two delegations of Hazara elders who had tried to intercede.[416][417]

By 1999, the Taliban had forced hundreds of thousands of people from the Shomali Plains and other regions conducting a policy of scorched earth burning homes, farm land and gardens.[414]

Human trafficking

Several Taliban and al-Qaeda commanders ran a network of human trafficking, abducting ethnic minority women and selling them into sex slavery in Afghanistan and Pakistan.[418] Time magazine writes: "The Taliban often argued that the restrictions they placed on women were actually a way of revering and protecting the opposite sex. The behavior of the Taliban during the six years they expanded their rule in Afghanistan made a mockery of that claim."[418]

The targets for human trafficking were especially women from the Tajik, Uzbek, Hazara and other non-Pashtun ethnic groups in Afghanistan. Some women preferred to commit suicide over slavery, killing themselves. During one Taliban and al-Qaeda offensive in 1999 in the Shomali Plains alone, more than 600 women were kidnapped.[418] Arab and Pakistani al-Qaeda militants, with local Taliban forces, forced them into trucks and buses.[418] Time magazine writes: "The trail of the missing Shomali women leads to Jalalabad, not far from the Pakistan border. There, according to eyewitnesses, the women were penned up inside Sar Shahi camp in the desert. The more desirable among them were selected and taken away. Some were trucked to Peshawar with the apparent complicity of Pakistani border guards. Others were taken to Khost, where bin Laden had several training camps." Officials from relief agencies say, the trail of many of the vanished women leads to Pakistan where they were sold to brothels or into private households to be kept as slaves.[418]

Not all Taliban commanders engaged in human trafficking. Many Taliban were opposed to the human trafficking operations conducted by al-Qaeda and other Taliban commanders. Nuruludah, a Taliban commander, is quoted as saying that in the Shomali Plains, he and 10 of his men freed some women who were being abducted by Pakistani members of al-Qaeda. In Jalalabad, local Taliban commanders freed women that were being held by Arab members of al-Qaeda in a camp.[418]

Oppression of women

To PHR's knowledge, no other régime in the world has methodically and violently forced half of its population into virtual house arrest, prohibiting them on pain of physical punishment.[420]

— Physicians for Human Rights, 1998

Brutal repression of women was widespread under the Taliban and it received significant international condemnation.[144][421][422][423][424][425][426][427][428][429][430] Abuses were myriad and violently enforced by the religious police.[431] For example, the Taliban issued edicts forbidding women from being educated, forcing girls to leave schools and colleges.[432][433][434][400][401][435][436][414] Women who were leaving their houses were required to be accompanied by a male relative and were obligated to wear the burqa,[437] a traditional dress covering the entire body except for a small slit out of which to see.[432][433] Those women who were accused of disobedience were publicly beaten. In one instance, a young woman named Sohaila was charged with adultery after she was caught walking with a man who was not a relative; she was publicly flogged in Ghazi Stadium, receiving 100 lashes.[438] Female employment was restricted to the medical sector, where male medical personnel were prohibited from treating women and girls.[432][439][440] This extensive ban on the employment of women further resulted in the widespread closure of primary schools, as almost all teachers prior to the Taliban's rise had been women, further restricting access to education not only to girls but also to boys. Restrictions became especially severe after the Taliban took control of the capital. In February 1998, for instance, religious police forced all women off the streets of Kabul and issued new regulations which ordered people to blacken their windows so that women would not be visible from outside.[441]

Violence against civilians

According to the United Nations, the Taliban and its allies were responsible for 76% of civilian casualties in Afghanistan in 2009, 75% in 2010 and 80% in 2011.[406][442]

According to Human Rights Watch, the Taliban's bombings and other attacks which have led to civilian casualties "sharply escalated in 2006" when "at least 669 Afghan civilians were killed in at least 350 armed attacks, most of which appear to have been intentionally launched at non-combatants."[443][444]

The United Nations reported that the number of civilians killed by both the Taliban and pro-government forces in the war rose nearly 50% between 2007 and 2009. The high number of civilians killed by the Taliban is blamed in part on their increasing use of improvised explosive devices (IEDs), "for instance, 16 IEDs have been planted in girls' schools" by the Taliban.[445]

In 2009, Colonel Richard Kemp, formerly Commander of British forces in Afghanistan and the intelligence coordinator for the British government, drew parallels between the tactics and strategy of Hamas in Gaza to those of the Taliban. Kemp wrote:

Like Hamas in Gaza, the Taliban in southern Afghanistan are masters at shielding themselves behind the civilian population and then melting in among them for protection. Women and children are trained and equipped to fight, collect intelligence, and ferry arms and ammunition between battles. Female suicide bombers are increasingly common. The use of women to shield gunmen as they engage NATO forces is now so normal it is deemed barely worthy of comment. Schools and houses are routinely booby-trapped. Snipers shelter in houses deliberately filled with women and children.[446][447]

— Richard Kemp, Commander of British forces in Afghanistan

Discrimination against Hindus and Sikhs

Hindus and Sikhs have lived in Afghanistan since historic times and they were prominent minorities in Afghanistan, well-established in terms of academics and businesses.[448] After the Afghan Civil War they started to migrate to India and other nations.[449] After the Taliban established the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, they imposed strict Sharia laws which discriminated against Hindus and Sikhs and caused the size of Afghanistan's Hindu and Sikh populations to fall at a very rapid rate because they emigrated from Afghanistan and established diasporas in the Western world.[450] The Taliban issued decrees that forbade non-Muslims from building places of worship but allowed them to worship at existing holy sites, forbade non-Muslims from criticizing Muslims, ordered non-Muslims to identify their houses by placing a yellow cloth on their rooftops, forbade non-Muslims from living in the same residence as Muslims, and required that non-Muslim women wear a yellow dress with a special mark so that Muslims could keep their distance from them (Hindus and Sikhs were mainly targeted).[451]

Violence against aid workers and Christians

On several occasions between 2008 and 2012, the Taliban claimed that they assassinated Western and Afghani medical or aid workers in Afghanistan, because they feared that the polio vaccine would make Muslim children sterile, because they suspected that the 'medical workers' were really spies, or because they suspected that the medical workers were proselytizing Christianity.

In August 2008, three Western women (British, Canadian, US) who were working for the aid group 'International Rescue Committee' were murdered in Kabul. The Taliban claimed that they killed them because they were foreign spies.[452] In October 2008, the British woman Gayle Williams working for Christian UK charity 'SERVE Afghanistan' – focusing on training and education for disabled persons – was murdered near Kabul. Taliban claimed they killed her because her organisation "was preaching Christianity in Afghanistan".[452] In all 2008 until October, 29 aid workers, 5 of whom non-Afghanis, were killed in Afghanistan.[452]

In August 2010, the Taliban claimed that they murdered 10 medical aid workers while they were passing through Badakhshan Province on their way from Kabul to Nuristan Province — but the Afghan Islamic party/militia Hezb-e Islami Gulbuddin has also claimed responsibility for those killings. The victims were six Americans, one Briton, one German and two Afghanis, working for a self-proclaimed "non-profit, Christian organization" which is named 'International Assistance Mission'. The Taliban stated that they murdered them because they were proselytizing Christianity and possessing which were translated into the Dari language when they were encountered. IAM contended that they "were not missionaries".[453]

In December 2012, unidentified gunmen killed four female UN polio-workers in Karachi in Pakistan; the Western news media suggested that there was a connection between the outspokenness of the Taliban and objections to and suspicions of such 'polio vaccinations'.[454] Eventually in 2012, a Pakistani Taliban commander in North Waziristan in Pakistan banned polio vaccinations,[455] and in March 2013, the Afghan government was forced to suspend its vaccination efforts in Nuristan Province because the Taliban was extremely influential in the province.[456] However, in May 2013, the Taliban's leaders changed their stance on polio vaccinations, saying that the vaccine is the only way to prevent polio and they also stated that they will work with immunization volunteers as long as polio workers are "unbiased" and "harmonized with the regional conditions, Islamic values and local cultural traditions."[457][458]

Restrictions on modern education

Before the Taliban came to power, education was highly regarded in Afghanistan and Kabul University attracted students from Asia and the Middle East. However, the Taliban imposed restrictions on modern education, banned the education of females, only allowed Islamic religious schools to stay open and only encouraged the teaching of the Qur'an. Around half of all of the schools in Afghanistan were destroyed.[459] The Taliban have carried out brutal attacks on teachers and students and they have also threatened parents and teachers.[460] As per a 1998 UNICEF report, 9 out of 10 girls and 2 out of 3 boys did not enroll in schools. By 2000, fewer than 4–5% of all Afghan children were being educated at the primary school level and even fewer of them were being educated at higher secondary and university levels.[459] Attacks on educational institutions, students and teachers and the forced enforcement of Islamic teachings have even continued after the Taliban were deposed from power. In December 2017, United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) reported that over 1,000 schools had been destroyed, damaged or occupied and 100 teachers and students had been killed by the Taliban.[461]

Cultural genocide

The Taliban have committed a cultural genocide against the Afghan people by destroying their historical and cultural texts, artifacts and sculptures.[462]

In the early 1990s, the National Museum of Afghanistan was attacked and looted numerous times, resulting in the loss of 70% of the 100,000 artifacts of Afghan culture and history which were then on display.[463]

On 11 August 1998, the Taliban destroyed the Puli Khumri Public Library. The library contained a collection of over 55,000 books and old manuscripts, one of the most valuable and beautiful collections of Afghanistan's cultural works according to the Afghan people.[464][465]

On 2 March 2001, the Buddhas of Bamiyan were destroyed with dynamite, on orders from the Taliban's leader Mullah Omar.[466] In October of the same year, the Taliban "took sledgehammers and axes to thousands of years’ worth of artifacts"[87] in the National Museum of Afghanistan, destroying at least 2,750 ancient works of art.[467]

Afghanistan has a rich musical culture, where music plays an important part in social functions like births and marriages and it has also played a major role in uniting an ethnically diverse country.[468] However, since it came to power and even after it was deposed, the Taliban has banned all music, including cultural folk music, and it has also attacked and killed a number of musicians.[468][469][470][471]

Ban on entertainment and recreational activities

During their first rule of Afghanistan which lasted from 1996 to 2001, the Taliban banned many recreational activities and games, such as association football, kite flying, and chess. Mediums of entertainment such as televisions, cinemas, music, VCRs and satellite dishes were also banned.[472] It has been reported that when children were caught kite flying, a popular activity among Afghan children, they were beaten.[473] Also included on the list of banned items were "musical instruments and accessories" and all visual representation of living creatures.[468][474][475][476] However, the daf, a type of frame drum, wasn't banned.[357]

Forced conscription and conscription of children

According to the testimony of Guantanamo captives before their Combatant Status Review Tribunals, the Taliban, in addition to conscripting men to serve as soldiers, also conscripted men to staff its civil service – both done at gunpoint.[477][478][479]